Abstract

Introduction

Urology continues to be a highly desirable specialty, despite decreasing exposure of students to Urology in U.S. medical schools. In this study, we set out to assess how U.S. medical schools compare to one another with regard to the number of students that each sends into Urological training and to evaluate the reasons why some medical schools consistently send more students into urology than others.

Materials and Methods

The authors obtained AUA Match data for the 5 Match seasons from 2005–2009. A survey of all successful participants was then performed. The survey instrument was designed to determine what aspects of the medical school experience influenced students to choose to specialize in Urology. A bivariate and multivariate analysis was then performed to assess which factors correlated with more students entering Urology from a particular medical school.

Results

Between 2005 and 2009, 1,149 medical students from 130 medical schools successfully participated in the Urology match. Of the 132 allopathic medical schools, 128 sent at least 1 student into Urology (mean 8.9, median 8, SD 6.5). A handful of medical schools were remarkable outliers, sending significantly more students into Urology than other institutions. Multivariate analysis revealed that a number of medical-school related variables including strong mentorship, medical school ranking, and medical school size correlated with more medical students entering Urology.

Conclusion

Some medical schools launch more Urologic careers than others. Although reasons for these findings are multifactorial, recruitment of Urologic talent pivots on these realities.

Keywords: urology residency, medical school, match, medical student

INTRODUCTION

The AUA Match process has been one of the most selective in medicine, with the number of applicants consistently exceeding the number of available positions.1–3 medical student decisions related to career choice are complex and are influenced by a number of competing factors.4, 5 Compelling data show that exposure to Urology in U.S. medical schools continues to decrease.6–8 However, little is known regarding how medical school factors influence decisions of medical students to enter Urology.5 To date, no public data exist regarding how medical schools compare to one another with respect to the number of medical students each sends into Urology. Understanding of such modifiable factors to recruit new trainees is critical in an era when the demand for urologists may soon exceed their supply.9 To assess how the medical school environment influences student decisions to enter the field of urology, AUA match data from the last five years was obtained and a national survey of urology residents was conducted.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population

We identified successful participants in the Urology specialty match between 2005 and 2009. Each participant’s medical school and email address were obtained from the AUA. AUA staff e-mailed a survey invitation to each successful participant with a functional email address. No proxies or substitutions were accepted. Non-responders were sent up to 3 reminder emails over the course of two weeks. All data were de-identified and analyzed in aggregate to preserve respondent anonymity.

Survey Instrument

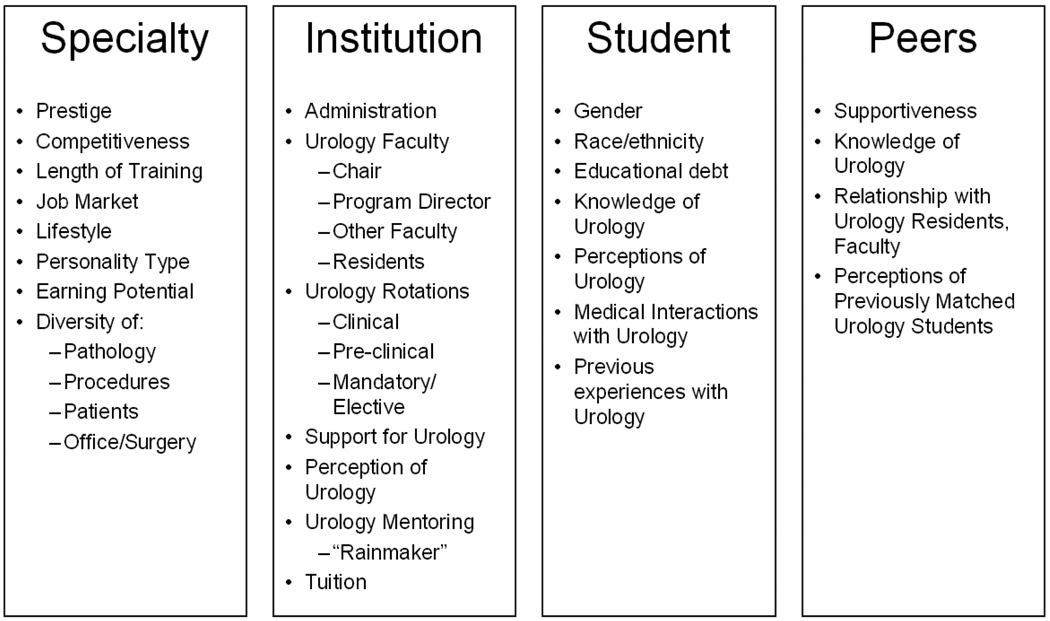

Based on our literature review of factors impacting specialty choice among medical students, we developed a web-based, 23-item survey instrument (Appendix 1) which tested student-, institution-, specialty-, and peer-specific factors (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Four domains and descriptors of the survey instrument used to query individuals who entered Urology between 2005 and 2009.

Key informant interviews were conducted to determine the content validity, readability, and respondent level of understanding of survey questions, as well as to verify the respondent time requirement. Members of the 2009–2010 AUA Residents Committee, all current Urology residents or fellows, served as an expert review panel for final survey testing.

Statistical Methods

Our primary outcome was the number of medical students matching into Urology from each U.S. medical school during the 5-year study period. We constructed multivariate Poisson regression models to examine associations between the predictors of interest and outcome after adjusting for confounders. The final models included respondent race/ethnicity, gender, medical school tuition and enrollment, Urology departmental ranking, faculty count, residency length, and whether the Urology chairperson was charismatic or nationally prominent, the program director was available to medical students, and the Urology residents were charismatic and available to medical students. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All tests were two-sided and p-values of 0.05 or less were considered to be significant.

We calculated survey response rates in accordance with accepted definitions10. Administrative approval was obtained from the AUA and Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Children's Hospital Boston.

RESULTS

Medical Schools & Urology Specialty Match

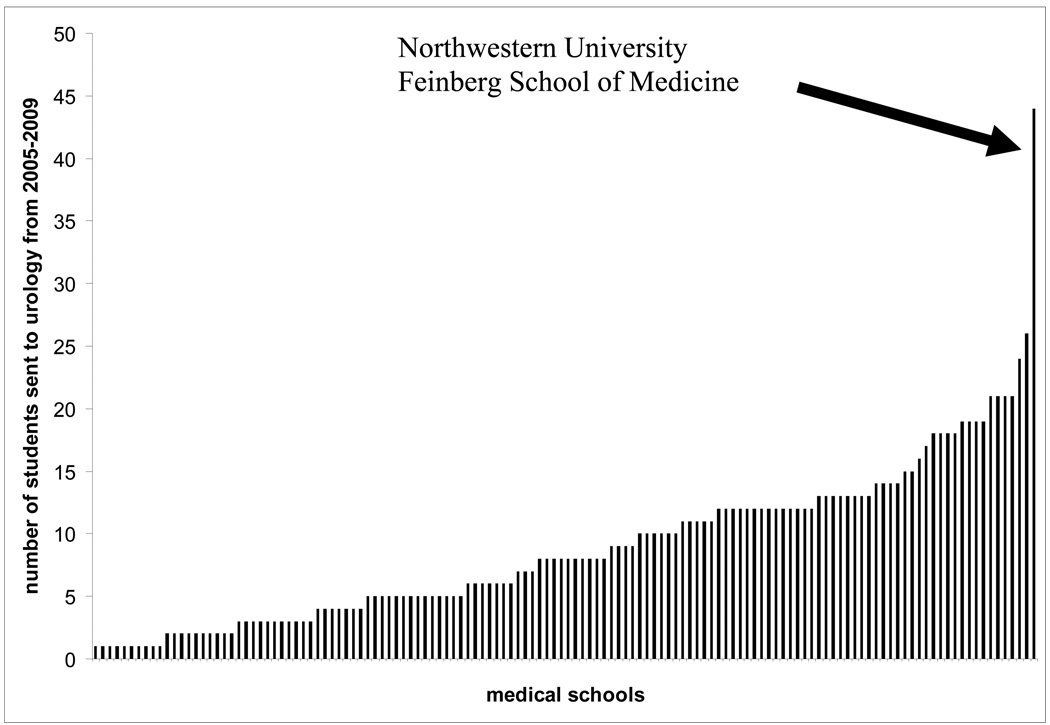

Between 2005 and 2009, 1,149 medical students from 130 medical schools successfully participated in the Urology match (Table 1). On average, 8.9 (median 8, standard deviation 6.5) medical students matched into Urology per medical school over the study period (Figure 2). The Top 20 medical schools (in terms of the total numbers of students matched over the study period) are listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic Data on Matched medical students from 2005–2009

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| # Matched medical students | 1,149 | |

|

Median, mean (SD) Matched students per medical school |

8, 8.9 (6.5) | |

| medical school Type | ||

| Private | 480 (42%) | |

| Public | 666 (58%) | |

| Mean (SD) medical school Tuition | $36,297 ($8,715) | |

| medical school Type | ||

| Allopathic | 1,140 (99%) | |

| Osteopathic | 9 (1%) | |

| U.S. News medical school Research Ranking | ||

| 1–10 | 100 (9%) | |

| 11–20 | 208 (18%) | |

| 21–30 | 70 (6%) | |

| 31–40 | 102 (9%) | |

| 41–50 | 104 (9%) | |

| 51–60 | 126 (11%) | |

| Not Ranked | 439 (38%) | |

| U.S. News medical school Primary Care Ranking | ||

| 1–10 | 103 (9%) | |

| 11–20 | 98 (9%) | |

| 21–30 | 123 (11%) | |

| 31–40 | 59 (5%) | |

| 41–50 | 89 (8%) | |

| 51–60 | 95 (8%) | |

| Not Ranked | 582 (51%) | |

| U.S. News medical school Urology Ranking | ||

| 1–10 | 111 (12%) | |

| 11–20 | 98 (11%) | |

| 21–30 | 120 (13%) | |

| 31–40 | 43 (5%) | |

| 41–50 | 60 (6%) | |

| Not Ranked | 495 (53%) | |

| Urology Residency Present at medical school | ||

| Yes | 1052 (92%) | |

| No | 97 (8%) | |

| Residency Length, if Present | ||

| 5 Years | 690 (66%) | |

| 6 Years | 351 (34%) | |

| Year Matched | ||

| 2005 | 218 (19%) | |

| 2006 | 222 (19%) | |

| 2007 | 233 (20%) | |

| 2008 | 225 (20%) | |

| 2009 | 251 (22%) | |

| AUA Section | ||

| Mid-Atlantic | 127 (11%) | |

| New England | 42 (4%) | |

| New York | 161 (14%) | |

| North Central | 271 (24%) | |

| Northeastern | 45 (4%) | |

| South Central | 197 (17%) | |

| Southeastern | 212 (19%) | |

| Western | 91 (8%) | |

Figure 2.

Bar graph demonstrating the number of medical students sent into urology by each U.S. medical school (128 allopathic + 2 osteopathic) between 2005 and 2009. Medical schools that did not send students into urology (4 allopathic + 26 osteopathic) during this time period are not shown.

Table 2.

Twenty medical schools that have sent the most students into Urology from 2005–2009.

| Name of Medical School | Number of Students Matched in Urology |

|---|---|

| Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine | 44 |

| Baylor College of Medicine | 26 |

| University of Michigan Medical School | 24 |

| State University of New York - Downstate | 21 |

| University of California at Los Angeles | 21 |

| University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill | 21 |

| University of Tennessee, Memphis | 21 |

| Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons | 19 |

| Saint Louis University School of Medicine | 19 |

| University of Minnesota Medical School | 19 |

| University of Toledo College of Medicine | 19 |

| Boston University School of Medicine | 18 |

| Indiana University School of Medicine | 18 |

| University of Cincinnati College of Medicine | 18 |

| University of Texas Southwestern Med. School at Dallas | 18 |

| University of Oklahoma College of Medicine | 17 |

| Jefferson Medical College | 16 |

| George Washington University | 15 |

| Weill Medical College of Cornell University | 15 |

Response Rate & Respondent Demographics

Of 1,149 eligible Urology residents, 1,009 had a valid email address. Of these, 413 Urology residents completed the survey for an overall response rate of 41%. Demographic data on respondents is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographic Data on Survey Respondents

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| # Respondents | 413 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 292 (76%) | |

| Female | 92 (24%) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 279 (71%) | |

| Asian | 77 (19%) | |

| Hispanic | 19 (5%) | |

| African-American | 12 (3%) | |

| Native American or Pacific Islander | 6 (1%) | |

| Total Educational Debt | ||

| <$10,000 | 56 (15%) | |

| $10,001–$50,000 | 9 (2%) | |

| $50,001–$100,000 | 30 (8%) | |

| $100,001–$150,000 | 57 (15%) | |

| $150,001–$200,000 | 65 (17%) | |

| $200,001–$250,000 | 97 (25%) | |

| >$250,001 | 71 (18%) | |

Survey Responses

Appendix 1 details survey responses. Most respondents had no previous experience with Urology (87%). Most felt that the Urology job market (85%), earning potential (91%), typical personality type (98%), and blend of procedures (99%), of surgical and clinical time (97%), of pathology (89%), and of patients (74%), were positive or very positive influences. The Urology faculty (86%), residents (85%), and chairperson (61%) at respondents’ medical schools were reported to be positive or very positive influences. However, 30% felt training length to be a negative influence. Additionally, respondents’ medical school administration and peers (both 62%) and length of Urology training (51%) were generally not a factor in their decision to specialize in Urology.

Medical School Factors Associated with Urology Match – Bivariate Analysis

Increased enrollment (r=0.26, p<0.0001), a larger number of Urology residents (r=0.38, p<0.0001) and a larger Urology faculty (r=0.46, p<0.0001) directly correlated with the number of successful match participants. Similarly, a better Urology departmental rank (r=−0.26, p<0.0001) and, to a lesser extent, medical school research rank (r=−0.11, p=0.01) correlated with the number of matched students. On average, schools with Urology residency programs matched more students than did those without (14.1 vs. 5.1, p<0.0001); allopathic medical schools matched more students than did osteopathic (13.5 vs. 2.1, p<0.0001); private medical schools matched more students than did public (14.9 vs. 12.4, p<0.0001); and schools with 6-year residency programs matched more students than did those with 5-year residencies (16.2 vs. 13.2, p<0.0001). Medical school tuition (r=0.06, p=0.05) and the medical school primary care rank (r=0.09, p=0.03) only weakly correlated with Urology match outcomes.

Among survey respondents, medical schools which had a mandatory clinical rotation in Urology matched more students than did those without (20.2 vs. 12.2, p<0.0001); longer mandatory Urology rotations strongly correlated with an increased number of matched students (r=0.74, p<0.0001). Similarly, medical schools with a basic/pre-clinical Urology course matched more students than did those without (18.0 vs. 12.5, p=0.0001). There was not a significant difference between schools offering elective Urology rotations and those which did not (13.7 vs. 9.3, p=0.15); however, only 8 respondents attended a medical school which did not offer an elective Urology rotation.

Increased numbers of matched medical students were associated with departments whose chairpersons were charismatic (p<0.0001) and nationally prominent (p<0.0001); whose program directors were available to medical students (p=0.0005); whose other faculty were charismatic (p=0.01) and nationally prominent (p<0.0001); and whose residents were charismatic (p=0.0005), supportive (p=0.002), available (p=0.0003), and nationally prominent (p<0.0001).

Medical School Factors Associated with Urology Match – Multivariate Analysis

Table 4 summarizes factors associated with students entering urology on multivariate analysis. medical school tuition (p=0.18), respondent race (p=0.53), gender (p=0.69), educational debt level (p=0.89), and the presence of a nationally prominent chairperson (p=0.27) and charismatic (p=0.16) or available (p=0.30) Urology residents were not associated with the number of successful Match participants.

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis of Medical School Factors Associated with AUA Match

| Factors Associated with More Students Matching in Urology |

p |

|---|---|

| Size of medical school Faculty | <0.0001 |

| 6-year (vs. 5-year) Urology Residency | <0.0001 |

| Presence of “supportive” program director | 0.004 |

| Presence of “charismatic” chairperson | 0.01 |

| High Urology Department ranking | 0.02 |

| medical school Class Size | 0.03 |

DISCUSSION

We herein report on the AUA Match data from 2005–2009, a unique dataset provided to the authors – all 2009–2010 members of the AUA Residents Committee – by the AUA. These data demonstrate that the number of medical students going into Urology varies widely based on medical school characteristics (Figure 2). Twenty medical schools (12.5%) sent 15 or more of medical students (greater than 1 standard deviation from the median) into Urology. This small group of schools was responsible for educating 33% (389 of 1172) of the entire cohort entering Urology during this time. The most remarkable of these “outliers” is Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, which sent 44 students into Urology between 2005 and 2009. Such deviation from the median (5.5 standard deviations) is truly remarkable, and suggests that the educational climate at Northwestern should be examined to determine why so many students choose urology as a specialty. Details regarding medical student Urology experience at Northwestern are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Details regarding medical student experience at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, which sent the most students (n=44) into Urology between 2005 and 2009 (5.5 standard deviations above the median). Source: Stephanie Kielb, MD, Program Director.

| Exposure to Urology | Details |

|---|---|

| Pre-Clinical |

|

| Core Clinical Rotations | During a three-month-long surgical clerkship, one month is dedicated to sub-specialty exposure and one month to ambulatory surgery. The majority of students spend time in the urology department either during the sub-specialty month as a four-week inpatient rotation or during the ambulatory surgery month as a two half-day per week urology clinic experience. In both rotations, there are weekly lectures and small group sessions with urology faculty in addition to casual educational experiences with the residents. |

| Sub-internship | As an elective rotation, fourth-year medical students spend one week at the Veterans Affairs Hospital, one week on each of the three Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH) inpatient services. Students spend ample time in both clinic and the operating room. The focus of the rotation is to meet and interact with the Urology attendings, provide ample exposure to many aspects of urology, increase the students’ knowledge of urology, and provide support during the application process. |

| Mentoring | Each third-year student is assigned a mentor during their rotation which provides evaluation and support during the experience. Additionally, each fourth-year medical student is assigned a mentor during the sub-internship to provide support during the application process. Students are encouraged to meet with multiple faculty members for advice on the application process, reviews of their application and personal statement, and for research opportunities. |

In general, the 413 respondents cited diversity of patient type, pathology, and procedures, personality types within Urology, earning potential and a strong job market as reasons to pursue Urology as a career. The majority of students (62%) indicated that if they did not match into urology they would have pursued another surgical specialty. Mentorship from the chairperson, faculty, and residents were cited to be positive or very positive influences by majority of respondents, similar to those from applicants to the 2003–2004 AUA Match reported by Kerfoot et al.5

In a multivariate analysis several independent variables predicted a higher number of students entering Urology. Larger class size and larger Urology faculty were independently associated with more students going into Urology. Interestingly, medical schools with 6-year Urology residency programs were more likely to send larger number of students into Urology than 5-year programs. This finding is intriguing; however, reasons for this observation cannot be determined from our data.

Strong mentorship has been suggested as a reason for more students entering Urology.5 Respondents in our study rated their medical school’s Urology chair, program director, faculty, and residents on the following four characteristics: (1) charisma, (2) supportiveness, (3) availability, and (4) prominent national reputation. A strong Urology chair and program director were both associated with high number of students entering Urology from a given medical school. Charisma, but not national reputation, appeared to be an important quality for the program chair, while supportive nature of the program director was the significant factor in our analysis.

In the multivariate analysis, higher ranking of a Urology department in the US News and World Report magazine correlated with more medical students entering Urology (p=0.02). Recently, Sehgal demonstrated that the overall ranking of Urology programs is largely a function of the US News and World Report reputation score,11 which is derived from subjective responses of ~250 surveyed urologists across the country who are asked to generate a list of the 5 “best” Urology programs.11 While a school’s rank according to US News and World Report may in fact influence medical students to enter Urology, it is also possible that the number and quality of medical students interviewed during the AUA Match season may instead influence the program rank list supplied by these ~250 urologists.

We examined whether mandatory exposure to Urology at a medical school correlated with more students entering the field. Indeed, concerns regarding decreasing exposure to Urology in U.S. medical schools were first raised in 1956.12 Since, a number of studies have documented a downward trend.7, 8, 13, 14 Most recently a survey of 95 Urology program directors revealed that there was no Urology lecture in the physical diagnosis course at 50% of medical schools with an active Urology program. Furthermore, at 34% of institutions exposure to Urology had decreased over a 10-year period. At the time when this survey was conducted in 2007, only 20% of responders reported having a required medical student rotation on the Urology service at their institution.6 A similar rate (17%) was reported by our respondents. We found that mandatory pre-clinical exposure, mandatory clinical rotation and length of clinical rotation strongly correlated with more medical students entering Urology on a bivariate analysis, but not on a multivariate model. Interestingly, we are not the first to suggest that a mandatory Urology rotation may not be critical to enlisting medical students into Urology. In a survey conducted by Kerfoot et al of 252 medical students who pursued a career in Emergency Medicine, only 2% reported that absence of exposure to Urology on the clinical wards influenced their decision to pursue a career outside Urology. Similarly, only 25% of 248 medical students who entered Urology reported that clinical exposure to Urology significantly influenced their decisions.5

We examined a number of other medical school-related variables (Figure 1, Appendix 1) which failed to show a relationship with the likelihood of medical schools sending students into urology. Several of these deserve mention. Students were asked about how informed, receptive, and supportive the administration at their medical school was regarding urology as a career, the relationship of the administration with the urology faculty, and the administration’s opinion of previous medical students who entered urology. Interestingly, these were not associated with the number of students entering urology. Identical questions were asked regarding medical school peers with similar results. Furthermore, charisma, availability, reputation, and supportiveness of urology residents had little effect on a medical school’s tendency to send medical students into urology.

Our survey only takes into account decisions of individuals who entered Urology. Responses from those students who applied to urologic residency but did not successfully match into a training program (or those who chose to pursue a career in another field) were not captured. The data were collected over a 2-week period in 2010; many individuals who participated went through the AUA match up to 5 years prior to completing the questionnaire. This interval between the Match and the survey may have influenced participant responses. Furthermore, imperfect response rates (41% in this study) have the potential to introduce response bias. Nevertheless, the response rate in this report is within the range of commonly reported rates for medical professionals.15–17

Our analysis only included those medical schools that have sent at least 1 student into Urology in the last 5 years. Medical schools that did not send students into Urology between 2005–2009 were not captured in our analysis. Furthermore, AUA Match data only include allopathic urology training programs, and several osteopathic urology training programs that exist are not captured by the AUA data. More importantly, intangible variables such as strength of faculty leadership, esprit de corps amongst students and residents, and the medical school’s and/or Urology departments’ ability to successfully navigate students through the match process are not fully reflected in these data. Furthermore, as in previous reports, our data regarding status of mandatory Urology exposure during medical school was obtained from survey respondents, since such information is currently not available through the AUA.6, 7 Due to an imperfect response rate and potential issues with respondent recall, our data and that of others may be biased. We suggest that the AUA begin to collect data regarding medical student exposure to Urology in medical schools in a prospective fashion in order to more rigorously address this important issue in the future.

Despite its limitations, the study is strengthened by a large number of respondents (n=413). Furthermore, this report integrates high fidelity, previously unavailable data from the AUA regarding AUA Match rates from all U.S. medical schools. This is the first study to demonstrate heterogeneity between medical schools in sending students to Urology and the high impact of a handful of medical schools in channeling talent into our field.

CONCLUSION

The current study presents previously unavailable data on the variability between U.S. medical schools in sending medical students to Urology. Survey results from successfully matched urology residents over the last 5 years reveal the importance of program director support, chair charisma, size of medical school faculty, 6 vs 5 year program length and, to a lesser extent, medical school class size and Urology department rank. This study only begins to answer the questions regarding why a medical school such as Northwestern is able to send on average over 8 medical students to Urology per year, while other seemingly similar institutions in some years fail to attract a single student into the field. Only by understanding the motivations, perceptions, and incentives that influence one’s decision to pursue Urology, can we ensure that Urology continues to attract high caliber talent into its ranks. Such issues are increasingly relevant in an era when the number of urologists is likely to grow.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Andriole DA, Schechtman KB, Ryan K, et al. How competitive is my surgical specialty? Am J Surg. 2002;184:1. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00890-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Urological Association Online. [Accessed June 1, 2010];Residency match: 2010 AUA Statistics. Available at: http://www.auanet.org/residents/resmatch.cfm#statistics.

- 3.Teichman JM, Anderson KD, Dorough MM, et al. The urology residency matching program in practice. J Urol. 2000;163:1878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah J, Manson J, Boyd J. Recruitment in urology: a national survey in the UK. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86:186. doi: 10.1308/003588404323043328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerfoot BP, Nabha KS, Masser BA, et al. What makes a medical student avoid or enter a career in urology? Results of an international survey. J Urol. 2005;174:1953. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000177462.61257.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loughlin KR. The current status of medical student urological education in the United States. J Urol. 2008;179:1087. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerfoot BP, Masser BA, Dewolf WC. The continued decline of formal urological education of medical students in the United States: does it matter? J Urol. 2006;175:2243. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson GS. The decline of urological education in United States medical schools. J Urol. 1994;152:169. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32848-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odisho AY, Fradet V, Cooperberg MR, et al. Geographic distribution of urologists throughout the United States using a county level approach. J Urol. 2009;181:760. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.AAPOR, editor. The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 6th ed. 2009. pp. 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sehgal AR. The role of reputation in U.S. News & World Report's rankings of the top 50 American hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:521. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-8-201004200-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns E, Hotchkiss RS, Flocks RH, et al. The present status of undergraduate urologic training. J Urol. 1956;76:309. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)66699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rous SN, Lancaster C. The current status of undergraduate urological teaching. J Urol. 1988;139:1160. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)42846-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rous SN, Mendelson M. A report on the present status of undergraduate urologic teaching in medical schools and some resulting recommendations. J Urol. 1978;119:303. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)57470-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akl EA, Maroun N, Klocke RA, et al. Electronic mail was not better than postal mail for surveying residents and faculty. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:425. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:1129. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerfoot BP, Turek PJ. What every graduating medical student should know about urology: the stakeholder viewpoint. Urology. 2008;71:549. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.