Abstract

Many bacterial chromosomes contain genomic islands, large DNA segments that became incorporated into the chromosome following their horizontal transmission. However, the mechanisms that mediate the lateral transfer of genomic islands are for the most part unknown. In this issue of Molecular Microbiology, Daccord et al describe a new type of transmissible genomic island that can be mobilized by co-resident integrating conjugative elements (ICEs). These ‘mobilizable genomic islands’ (MGIs) require many ICE-encoded factors for their transmission, including transcription activators to induce MGI excision, the relaxase to initiate transfer at the MGI oriT and the conjugation machinery to transport MGI DNA to recipient cells. However, MGIs encode their own integrases, which enable their recombination with the chromosome of a new host, as well as a variety of other genes that do not have functions related to mobility. The MGI oriT, which resembles the ICE oriT, can also serve as a site for initiation of ICE-mediated conjugative transfer of large regions of chromosomal DNA. Overall, these findings raise the possibility that mobilization of chromosomal DNA from cyptic oriTs within genomic islands or elsewhere on the chromosome could be more common place than has been previously appreciated.

With more than 700 bacterial genome sequences now available, it is clear that most bacterial chromosomes are mosaics, composed of DNA obtained via horizontal gene transfer as well as vertical inheritance. Horizontally acquired sequences typically include integrated mobile elements, such as prophages and integrating conjugative elements (ICEs, aka conjugative transposons). Many chromosomes also contain ‘genomic islands’ (GIs), DNA segments that do not encode the machinery for self-mobilization like phages and ICEs, but nevertheless are thought to be (or to have been) mobile DNA elements because they differ in G+C content from the surrounding chromosome (Boyd et al., 2009, Dobrindt et al., 2004, Juhas et al., 2009). Furthermore, GIs are often flanked by direct repeats, and they encode recombinases that likely enable their integration into the host chromosome. GIs can be large and frequently encode sets of proteins that enable the host bacterium to occupy a new niche. For example, the TCP pathogenicity island (a kind of GI that encodes virulence determinants) enables Vibrio cholerae, the agent of cholera, to colonize the human small intestine (Herrington et al., 1988, Kovach et al., 1996). Since GIs are not self-transmissible, a key question regarding these horizontally transfered DNA segments has been how are they mobilized? In this issue of Molecular Microbiology, Burrus and colleagues identify and describe mobilizable GIs (MGIs) in several vibrio species. MGIs are satellite elements that depend on ICEs for their transfer (Daccord et al., 2010). They show that MGIs, by mimicking a co-resident ICE’s origin of transfer (oriT), can exploit ICE-encoded mobilization and transfer functions to enable their conjugative transfer to other bacteria. Their work also raises the exciting possibility that similar mimicry of oriT sequences could explain the lateral transfer of up to megabase segments of chromosomal DNA.

Conjugative DNA transfer is a multistep process that begins when a plasmid or ICE encoded relaxase (often called TraI), recognizes and nicks an oriT, a cis-acting site, yielding a single-stranded DNA break (de la Cruz et al., 2009). Subsequently, single-stranded DNA is exported to the recipient cell via plasmid or ICE-encoded conjugation machinery through a mating pore. Once transferred to the recipient cell, plasmids replicate as extrachromosomal elements, whereas ICEs integrate into the host chromosome in a process that requires an ICE-encoded recombinase (Wozniak & Waldor, 2010). Daccord et al noticed that sequences similar to the oriT of SXT, an ICE that is found in gram-negative bacteria, including several species of pathogenic vibrios, were found in the chromosomes of 2 recently sequenced vibrios (Daccord et al., 2010). Analyses of the sequences surrounding these oriTSXT-like sequences revealed that they were part of GIs whose sequences were not related to SXT. Both GIs encoded a conserved putative recombinase (IntMGI), but they also had distinct gene contents. A third related GI was identified by probing a collection of strains with the intMGI sequence; all 3 MGIs were located in the same locus in their respective genomes.

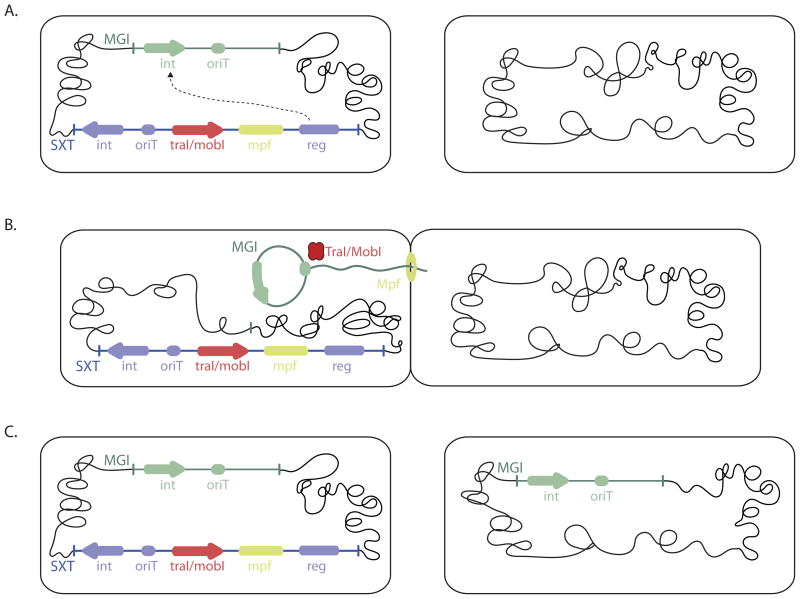

Daccord et al found that SXT-encoded proteins could recognize and mediate the transfer of an ordinarily non-mobilizable vector if it contained oriTMGI. Furthermore, the MGIs themselves were mobilizable in a SXT-dependent fashion when they were present in the same donor cell (Figure 1). Importantly, MGI transfer was dependent on oriTMGI as well as the SXT genes traI and mobI, which encode the putative SXT relaxase and a factor required for relaxase activity respectively (Ceccarelli et al., 2008); however, SXT gene products that mediate the element’s integration into and excision from the chromosome were not required for MGI transfer. IntMGI, the MGI recombinase, was critical for MGI excision as well the integration of MGI DNA into the recipient chromosome. Together, their findings suggest that excised circularized MGI DNA becomes a substrate for the ICE conjugation machinery because their oriTs are recognized and cleaved by ICE relaxases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of SXT mobilization of an MGI. A. SXT encoded transcription factors (reg) induce expression of IntMGI. B. This recombinase enables the MGI to excise from the chromosome and circularize. TraI and MobI, the SXT encoded relaxase and accessory factor generate single-stranded MGI DNA which is transported via the SXT-encoded conjugation machinery (mpf). C. In the recipient cell, IntMGI enables MGI DNA to recombine with chromosomal DNA. TraI and MobI can also initiate transfer of chromosomal DNA from oriTMGI (not shown).

ICEs are not only capable of mobilizing themselves and MGIs. SXT is known to be capable of mobilizing large fragments of chromosomal DNA in cis, via a process where transfer of chromosomal DNA initiates from the ICE’s oriT (Hochhut et al., 2000). Daccord et al found that ICEs can also mediate transfer of segments of chromosomal DNA in trans, via a process where transfer of chromosomal DNA initiates from the MGI’s oriT. Since oriTMGI and oriTSXT are far apart in the chromosome, ICE mediated transfer of chromosomal DNA in cis, from oriTSXT, or in trans from oriTMGI can in principal enable horizontal transmission of most of the chromosome.

The dependence of MGIs on ICEs for their horizontal transmission is not limited to the ICE-encoded MobI/TraI and conjugation machinery. MGIs also depend on SXT transcriptional activators, which are thought to enable expression of intMGI. Without IntMGI, MGIs would be incapable of excision and would therefore be locked into the host chromosome. Expression of the SXT activators is elevated by the host SOS response to DNA damage (Beaber et al., 2004, Beaber & Waldor, 2004). The authors found that the frequency of MGI transfer is increased more than 100-fold by the host SOS response, at least in part because MGI excision was enhanced in this setting. Thus, MGIs take advantage of ICE-encoded regulatory machinery to control their transmission.

Overall, MGIs can be thought of as satellite conjugative elements, which depend on a co-resident ICE for their transmission. Several satellite phages, such as E. coli P4 (Liu et al., 1998) and V. cholerae RS1 (Davis et al., 2002), whose DNA is packaged into virions encoded by co-resident prophages (P2 and CTXφ for P4 and RS1, respectively), have been described. However, satellite conjugative elements are unusual, although NBUs (Non-replicating Bacteriodes Units) are another type of satellite conjugative element (Salyers et al., 1995). NBUs are excised and mobilized by Bacteriodes conjugative transposons, but in contrast to MGIs, NBUs do not depend on the relaxase encoded by the conjugative transposon. Transmission of both types of satellite conjugative elements is stimulated by conditions that induce transfer of the respective parent ICE (Song et al., 2009, Daccord et al., 2010).

Finally, as Burrus and colleagues suggest, their discovery that mimicry of oriT sequences can provide a molecular basis for mobilization of chromosomal DNA by ICEs may have broad implications for genome evolution. Mobilization of chromosomal DNA from cyptic oriTs within GIs or elsewhere on the chromosome could be much more common place than has been previously appreciated. Conjugative plasmids as well as ICEs could mobilize chromosomal DNA from cryptic chromosomal oriTs as described by Meyer (Meyer, 2009). Since MGIs require many ICE-encoded functions for excision and conjugative transfer, it seems likely that these 2 elements have co-evolved. However, less intimate connections between conjugative elements and cryptic chromosomal oriTs seem possible. Since ICEs or plasmids can enable transfer of chromosomal DNA from cyptic oriTs without being transmitted themselves, it may be difficult to assess the true contribution of oriT mimicry to genome evolution.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Hue Lam for making figure 1 and Brigid Davis for helpful comments on the manuscript. The Waldor lab is supported by NIAID R37-42347 and HHMI.

References

- Beaber JW, Hochhut B, Waldor MK. SOS response promotes horizontal dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. Nature. 2004;427:72–74. doi: 10.1038/nature02241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaber JW, Waldor MK. Identification of operators and promoters that control SXT conjugative transfer. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5945–5949. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.17.5945-5949.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd EF, Almagro-Moreno S, Parent MA. Genomic islands are dynamic, ancient integrative elements in bacterial evolution. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli D, Daccord A, Rene M, Burrus V. Identification of the origin of transfer (oriT) and a new gene required for mobilization of the SXT/R391 family of integrating conjugative elements. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:5328–5338. doi: 10.1128/JB.00150-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daccord A, Ceccarelli D, Burrus V. Integrating conjugative elements of the SXT/R391 family trigger the excision and dirve the mobilization of a new class of Vibrio genomic islands. Mol Microbiol. 2010;xx:yy. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BM, Kimsey HH, Kane AV, Waldor MK. A satellite phage-encoded antirepressor induces repressor aggregation and cholera toxin gene transfer. EMBO J. 2002;21:4240–4249. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz F, Frost LS, Meyer RJ, Zechner EL. Conjugative DNA metabolism in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;34:18–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrindt U, Hochhut B, Hentschel U, Hacker J. Genomic islands in pathogenic and environmental microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:414–424. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrington DA, Hall RH, Losonsky G, Mekalanos JJ, Taylor RK, Levine MM. Toxin, toxin-coregulated pili, and the toxR regulon are essential for Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis in humans. J Exp Med. 1988;168:1487–1492. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.4.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochhut B, Marrero J, Waldor MK. Mobilization of plasmids and chromosomal DNA mediated by the SXT element, a constin found in Vibrio cholerae O139. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2043–2047. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.7.2043-2047.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhas M, van der Meer JR, Gaillard M, Harding RM, Hood DW, Crook DW. Genomic islands: tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and evolution. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;33:376–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach ME, Shaffer MD, Peterson KM. A putative integrase gene defines the distal end of a large cluster of ToxR-regulated colonization genes in Vibrio cholerae. Microbiol. 1996;142:2165–2174. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-8-2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Renberg SK, Haggard-Ljungquist E. The E protein of satellite phage P4 acts as an anti-repressor by binding to the C protein of helper phage P2. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:1041–1050. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer R. The R1162 mob proteins can promote conjugative transfer from cryptic origins in the bacterial chromosome. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:1574–1580. doi: 10.1128/JB.01471-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salyers AA, Shoemaker NB, Li LY. In the driver’s seat: the Bacteroides conjugative transposons and the elements they mobilize. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5727–5731. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5727-5731.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B, Wang GR, Shoemaker NB, Salyers AA. An unexpected effect of tetracycline concentration: growth phase-associated excision of the Bacteroides mobilizable transposon NBU1. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:1078–1082. doi: 10.1128/JB.00637-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak RA, Waldor MK. Integrative and conjugative elements: mosaic mobile genetic elements enabling dynamic lateral gene flow. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:552–563. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]