Abstract

We explored the relations between task difficulty and speech time in picture description tasks. Six native speakers of Mandarin Chinese (CH group) and six native speakers or Indo-European languages (IE group) produced quick and accurate verbal descriptions of pictures in a self-paced manner. The pictures always involved two objects, a plate and one of the three objects (a stick, a fork, or a knife) located and oriented differently with respect to the plate in different trials. An index of difficulty was assigned to each picture. CH group showed lower reaction time and much lower speech time. Speech time scaled linearly with the log-transformed index of difficulty in all subjects. The results suggest generality of Fitts’ law for movement and speech tasks, and possibly for other cognitive tasks as well. The differences between the CH and IE groups may be due to specific task features, differences in the grammatical rules of CH and IE languages, and possible use of tone for information transmission.

Keywords: speech production, picture description, reaction time, Fitts’ law, Chinese, Indo-European languages

Introduction

How long does it take a person to create and utter a phrase describing a situation (a meaning, in a general sense) quickly and accurately? Surprisingly, there is little experimental material relevant to this very basic question. Note that speech time reflects the overall outcome of many cognitive, neurophysiological, and mechanical processes involved in speech production.

To study the issue of speech timing during natural phrase formation and production, one has to be able to standardize and quantify tasks. In a recent study, we offered an approach to this problem using picture description tasks (Latash and Mikaelian 2008). Such tasks have been used to address a variety of speech related issues such as hemispheric differences, effects of priming, speech errors, and speech impairments in neurological patients (Vitevitch 1997, 2002; Branigan, Pickering, Stuart and McLean 2000; Gordon 2002; De Roo, Kolk and Holfstede 2003; Maher et al. 2005; Lincoln, Long, and Baynes 2007). A major advantage of picture description tasks is the possibility to standardize the task and manipulate its quantifiable characteristics thus standardizing and manipulating the meaning that has to be expressed by the subject.

In our first study (Latash and Mikaelian 2010), the subjects were required to describepictures as quickly as possible, while the number of objects (NO) shown in the pictures and the number of object characteristics (NC) were systematically manipulated. Speech time (ST) showed very strong linear scaling with NO; in other words, the amount of time spent to describe one object did not depend on the number of objects (assuming that all objects differed from each other). In turn, time-per-object scaled linearly with NC with a close to zero intercept. As a result, the two relations could be combined into one:

| (1) |

where a and b are constants.

Note that this relation differs qualitatively from the quadratic dependence of ST on the number of words reported by the group of Sternberg (Sternberg, Monsell, Knoll, and Wright 1978; Sternberg, Wright, Knoll, and Monsell 1980; Sternberg, Knoll, Monsell, and Wright 1988). In those studies a different question was asked: How long does it take a person to pronounce an utterance consisting of ‘n’ elements (words, numerals, or non-words) with each element consisting of ‘m’ syllables? The elements had been presented to the subject in advance. Consequently, the subjects did not need to construct a phrase but rather to utter the elements as quickly as possible.

The linear relation between ST and the product NO·NC may be viewed as a reflection of a more general relation between task difficulty and time required to perform the task. Indeed, it is intuitively clear that describing larger sets of objects takes longer than describing smaller sets of objects. It is also clear that simply naming objects takes less time than describing their properties such as, for example, size, color, location with respect to each other, etc. These intuitive considerations have been confirmed experimentally and the specific functional form linking ST and NO·NC has been expressed as Eq. (1).

This speed-difficulty trade-off resembles a well-known group of phenomena in human limb movements commonly addressed as speed-accuracy trade-offs. First, there is an increase in dispersion of the endpoint final coordinate with an increase in movement speed (for example, peak speed or mean speed, reviewed in Schmidt, Zelaznik, Hawkins, Frank and Quinn 1979). Second, there is an increase in movement time (MT) when the task becomes more difficult (reviewed in Meyer, Smith, Kornblum, Abrams and Wright 1990). The latter trade-off is particularly close in spirit to the introduced speed-difficulty trade-off in speech. It has been commonly expressed as a linear relation between movement time (MT) and an index of difficulty (ID), computed as the log-transformed ratio of movement distance to target width: MT = c + d·ID; where ID = log2(2D/W), D is movement distance, W is target width, c and d are constants. This relation, known as Fitts’ law (Fitts 1954; Fitts and Petersen 1964), has been confirmed across a broad variety of tasks, external conditions, and populations (reviewed in Plamondon and Alimi 1997).

Several hypotheses have been offered to account for Fitts’ law. The original paper by Fitts (1954) was based on the information theory; it is compatible with more recent developments suggesting that Fitts’ law originates at the level of movement planning (Gutman, Latash, Gottlieb and Almeida 1993; Duarte and Latash 2007). Why does manipulation of task parameters leading to an increase in task difficulty lead to a linear increase in ST and a logarithmic increase in MT? We hypothesized that the linearity of the relation expressed by Eq. (1) was due to two factors. First, the subjects used a particular strategy describing the objects one-by-one. Second, there were only a few simple characteristics of each object such that the tasks could correspond to a close to linear range of a more general logarithmic function.

In the first study (Latash and Mikaelian 2008), we found a linear relationship between speech time and index of difficulty. We hypothesized that the linearity of the ST(ID) was due to the relatively small range of ID values. The current study was designed to explore a broader range of ID while keeping the number of objects to a minimum (two). We hypothesized that ST would show a logarithmic increase with ID. We also explored differences between Indo-European languages (English and Russian) and Mandarin Chinese to find out if the ST(ID) relation may provide a language-sensitive measure.

Methods

Subjects

Twelve healthy volunteers participated in the experiments, five males and seven females with the age of 20 to 54 years. They all had normal or corrected to normal vision. Six subjects were native Chinese (Mandarin) speakers, three were native English speakers, and three more were native Russian speakers. The Chinese and Russian speakers were all fluent in English. All the procedures were approved by the Office for Research Protection at the Pennsylvania State University.

Apparatus and Procedures

The subject sat in a chair facing a laptop computer (Dell Latitude D830) with the 15” screen placed on the table about 0.8 m away from the subject. Plantronics digital DSP400 headphones with a microphone were placed naturally on the subject’s head such that the microphone was about 5 cm from the mouth. The microphone was connected to the USB port of the computer. The sound signal was collected at 10 kHz using a Matlab based program.

During the experiment, the subject was instructed to press the mouse key, wait for a picture to appear on the screen, and describe the picture as quickly and accurately as possible. The instruction was always given in English in the following way: “Imagine that there is a person who cannot see the computer screen. You have to tell this person as quickly as possible what you see such that he or she is able to re-create this picture in all the important details”. After describing the picture, the subject was to remain silent until the end of the trial (12 s). Then, the subject could press the key again and the next picture emerged on the screen. As such, the subjects paced the experiment themselves. They were reminded to take rest periods as needed. Rest intervals of at least two minutes were given between series. The whole experimental session took about 30 min.

Each picture showed two objects, one of which was always the same: A plate in the middle of the screen. The second objects could be a stick, a fork, or a knife (Figure 1). Prior to the experiment, the subjects were shown the objects one by one and asked to decide how they would call them during the experiment. Note that the stick is a symmetric object with the two ends and two sides identical to each other. In contrast, the fork has two ends (the prongs and the handle), while the two sides are symmetrical. The knife has two ends (the sharp end and the handle) and also the two sides (the sharp and the dull ones). The second object could be located under the plate, above the plate, to the left of the plate, to the right of the plate, or centered about one of the four corners. The objects could be oriented vertically, horizontally, 45° to the vertical, or slightly tilted. Examples of different object orientations and locations are shown in the three panels of Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Three typical pictures that the subjects were asked to describe. The object (a knife, a fork, or a stick) could be oriented vertically (not shown), horizontal (left upper panel), tilted 45° (right upper panel), and slightly tilted (lower panel). It could be located above the plate (left upper panel), below the plate, to the right of the plate, to the left of the plate (right upper panel), or centered about one of the corners (lower panel).

There were three series; each series consisted of 24 pictures. The compositions of the 72 pictures were selected at random from all possible compositions to have a balanced representation of different difficulty levels. The combinations of factors such as Object, Location, and Orientation were used to estimate difficulty index of each task (see the next section).

The subjects were free to select their preferred strategy of describing the objects, but they were always reminded to try to do this as quickly as possible. They were also reminded to obey the rules of grammar. For example, equivalent descriptions of a picture could be: “The knife is vertical to the left of the plate, the sharp end up, and the blade turned right” or “The knife is to the left of the plate with the blade facing the plate, and the sharp end pointing upwards.” Within this experiment, we did not study specific strategies of object description, rather regularities that were present in spite of the different strategies. As a result of the instruction, there was a lot of variability across the subjects and within the subjects across trials in the lexical material used. This was one of the reasons we did not perform analysis of the number of words (or syllables, or stresses) but limited ourselves in this study to analysis of the speech time and reaction time as functions of quantifiable features of the pictures. We are perfectly aware of the fact that measures of the amount of lexical material probably covaried with our task and performance variables but leave analysis of these possible covariations for future studies.

Prior to the first series, the subjects were given a detailed explanation of the task, a brief demonstration of the objects, their properties, and their possible relative configurations. Then, they performed five to ten practice trials. If a subject asked for additional practice, it was always given to the subject; this happened in two out of the 12 subjects.

Data Analysis

Analysis was performed off-line. First, a Matlab based program was used to define the times of initiation and termination of the speech signal in each trial. For this purpose, the power of the signal was computed at each sample using the integral of the power spectral density distribution over all the frequencies. Then, the peak value (PPEAK) of the signal power was computed. Further, the time when the signal first reached 10% of PPEAK was detected and used as the time of speech initiation (TSI), and the time when the signal dropped under 10% of PPEAK and remained under this value until the end of the trial was found and used as the time of speech termination (TST). Reaction time (RT) was measured as the time from the trial initiation (picture presentation) to TSI. Speech time (ST) was defined as the difference between TST and TSI.

In some trials, one of the times, TSI or TST could not be determined reliably using the described routine due to coughing or heavy breathing by the subject or extraneous noises. Such trials, as well as trials when the subjects could not describe the picture within 12 s, were rejected from further analysis. On average, less than 10% of the trials were rejected.

Each task was assigned an index of difficulty (ID) according to the following equation: ID = IDOB·IDLO·IDOR, where IDOB is index of difficulty of the object, IDLO is index of difficulty of the location, and IDOR is index of difficulty of the orientation. IDOB has been assigned three values, 1 (stick), 2 (fork), and 4 (knife). IDLO has been assigned two values, 1 (above, below, to the left, and to the right of the plate) and 2 (at one of the corners). IDOR has been assigned two values, 1 (vertical or horizontal) and 4 (tilted 45° and slightly tilted). These values have been assigned based on an intuitive consideration of the number of “things” one has to describe for the mentioned characteristics. For example, the stick only had to be named; for the fork, the direction of the prongs had also to be described, while for the knife both the direction of the sharp end and the orientation of the blade had to be described. Simple locations (IDLO = 1), required the subject to name only one thing (above, below, to the right, or to the left of the plate), while locations at the corners (IDLO = 2) required the subject to name whether the corner is above or below and whether it is to the right or to the left of the plate. For tilted objects (IDOR = 4), both the angle of the tilt and the direction of the upper end had to be described (for example, “the stick is to the right of the plate, tilted 45°, with the upper end pointing to the right”). So, we assigned the pictures ID values based on the described considerations and then tested whether speech time changed with assumed ID as predicted by Fitts’ law. One could, alternatively, assume that the data obeyed Fitts’ law and infer ID values from multiple regression analyses. We believe that our method fits the purpose of the study better. Besides, the very large amounts of variance accounted for in the analysis (see Results) provide indirect support for the method of assigning ID values.

As a result, the trials with the stick had ID values of 1, 2, 4, and 8; the trials with the fork had ID values of 2, 4, 8, and 16; and the trials with the knife had ID values of 4, 8, 6, and 32. The data were averaged within each subject across trials for each given object that had the same ID values. Further, linear and logarithmic regression analyses were used to analyze the dependences of RT and ST on ID.

Analysis of variance with repeated measures was used with factors Language (a between-factor, two levels, Chinese and Indo-European), Object (three levels, stick, fork, and knife), Location (two levels, simple and complex), and Orientation (two levels, simple and complex). Tukey’s pair-wise contrasts were used to analyze significant effects at p < 0.05.

Results

This section is organized in the following way. First, we describe regularities of the reaction time. Then, results for the speech time are presented. There were no clear differences in any of the outcome measures between the Russian speaking and English speaking subjects (parenthetically, we pilot tested two more subjects who spoke Portuguese and Hindi, and their results were similar to those of the English-Russian group). The English-Russian group was, however, significantly different from the Chinese speakers. Hence, we present the data for the English and Russian speakers combined as an “Indo-European” group.

Reaction Time Analysis

There were significant differences in RT between the Chinese speaking subjects and the English-Russian group (CH and IE groups). On average, RT for the CH group was 0.97 s, while it was 1.13 s for the IE group. There was a trend for RT to be the shortest for the pictures with the stick (1.02 s), slightly longer for the pictures with the fork (1.05 s), and even longer for the pictures with the knife (1.09 s), as well as a trend for longer RT for complex locations as compared to simple locations and for longer RT for complex orientations as compared to simple orientations (on average, 1.03 s vs. 1.07 s for both comparisons). However, ANOVA with repeated measures on RT showed significant effects only of Language (F[1,136] = 40.85; p < 0.001), but no effects of Object, Location, and Orientation (p > 0.1) and no significant interactions.

Individual subjects showed substantial variability in RT and no clear relation of RT to the index of difficulty (ID). However, when the data were averaged across the subjects within each group, a significant relation was observed between RT and ln(ID) for the IE group but not for the CH group. This result is illustrated in Figure 2, top panel. Each point represents the data averaged first within a subject (over trials with the same combinations of Object, Location, and Orientation) and then across the subjects. Note the shorter RT for the CH group (open circles and thin, solid regression line), which showed a very weak dependence on ln(ID), R2 = 0.10. The IE subjects showed longer RT, and there was a significant increase in RT with ln(ID), R2 = 0.53 (p < 0.05). Note the very similar intercept values for the two groups of subjects and the more than three-fold difference in the regression coefficients (the slopes of the regression lines). The effects of Language and the non-significant trends of Object and Orientation are illustrated in panels B and C Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Upper panel: Changes in reaction time (RT) with the log-transformed index of difficulty, ln(ID). Middle panel: RT dependence on the object to be described. Lower panel: RT dependence on the orientation of the object with respect to the plate. The data are presented separately for the CH group (open circles, white columns) and IE group (filled circles, black columns), as well as for the data pooled over all the subjects (large square symbols, striped columns). Note the higher RT that scaled with ID for the IE group. Standard errors bars across subjects are shown. The data for different symbols have been slightly misaligned for better visualization (to avoid overlapping error bars).

Speech Time Analysis

In contrast to RT, speech time (ST) showed strong dependences on all the factors, Object, Location, and Orientation, as well as a significant difference between the two groups (Language factor). ANOVA with repeated measures has shown main effects of all four factors (F > 15.0; p < 0.001) without significant interactions. The effects of Object, Location, and Orientation could be combined into a single relation between ST and ID.

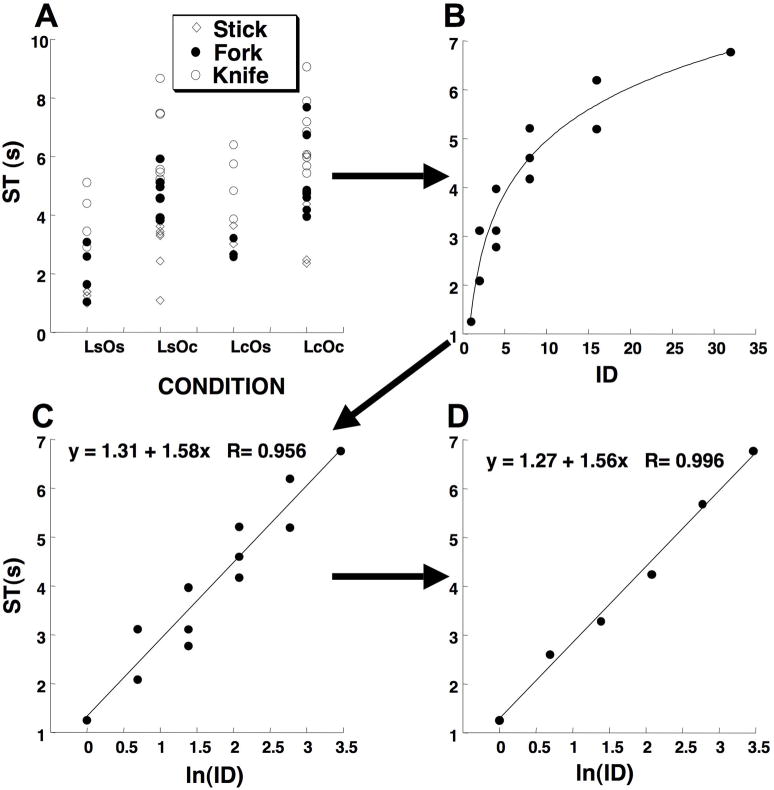

Figure 3 illustrates the major steps in the data processing. Its upper left panel shows the data for all individual trials for a representative subject (from the IE group). Different symbols show the data for pictures with different objects, while the X-axis shows different combinations of Location and Orientation factors. The upper right panel shows the data averaged over the same combinations of Object, Location, and Orientation and plotted as functions of ID. Note the typical logarithmic shape of the regression line. In the lower left panel, the same data are plotted as functions of ln(ID). Note the strong linear relation between ST and ln(ID). In the lower right panel, the data were further reduced by averaging over the same ID values resulting in six data points. Note the very strong linear relation between ST and ln(ID). Such relations were observed for all individual subjects. Note that the critical value of the correlation coefficient for 6 observations is 0.92 (p < 0.01). All the subjects shower R values higher than 0.92.

Figure 3.

An illustration of data processing in the analysis of speech time (ST) for a representative subject (native Russian speaker, IE group). The upper left graph (A) shows all the raw data for the three objects, a stick (rhombs), a fork (filled circles), and a knife (open circles) and for the four combinations of location and orientation, LsOs–location simple and orientation simple, LsOc–location simple and orientation complex, LcOs–location complex and orientation simple, and LcOc–location complex and orientation complex. In panel B, ST values were averaged across all trials with the same combinations of Object, Location, and Orientation and plotted as function of the index of difficulty (ID). A log-regression line is drawn. In panel C, the ID scale is log-transformed, and a linear regression line and equation are shown. In panel D, ST were averaged across points for the same ID values. A linear regression line and equation are shown.

Figure 4 illustrates the data for all individual subjects and also averaged data for the two groups (larger symbols and thicker regression lines). Note the strong linear relations for both individual subjects and for the averaged data. Note also the steeper slopes of the regression lines for the IE subjects (solid lines) as compared to the CH subjects (dashed lines). On average, regression coefficients were more than two-fold larger for the IE group as compared to the CH group (1.43 vs. 0.63, p < 0.01); there were no significant differences in the intercept of the linear regressions (1.42 vs. 1.49, ns).

Figure 4.

Dependences of speech time (ST) on the index of difficulty (ID) for all individual subjects (small symbols) and for the data averaged across the subjects within each group (large symbols). Linear regression lines and equations are shown. Note the clustering of the data for the IE group (filled symbols, solid lines) and for the CH group (open symbols, dashed lines). Note also the higher slopes for the IE group without a difference in the intercept.

Discussion

The main hypothesis formulated in the Introduction has been confirmed: Changes in the index of difficulty (ID) were associated with a logarithmic increase in speech time (ST). Parameters of the relation between ST and ID differed significantly between the two groups of subjects, those speaking the Indo-European languages, IE group and those speaking the Mandarin Chinese, CH group. In addition, a significant increase in reaction time (RT) with ID was observed for the IE group, but a much weaker relation (non-significant) was seen for the CH group. In the following discussion, we address such issues as the speed-difficulty trade-off in speech and movement production, and possible common origins of the effects of ID on ST and RT. We also speculate on reasons for the differences between the IE and CH groups.

Speed-Difficulty Trade-off in Speech, Movement, and Beyond

The notion of speed-accuracy trade-off has been invoked with respect to speech perception (Remington 1977), visual word recognition (Ferrand and Grainger 2003), and motion of speech articulators such as the tongue (Goozee, Stephenson, Murdoch, Darnell, and Lapointe 2005). However, to the authors’ knowledge, dependence of speech time on task difficulty has not been studied with respect to the whole act of production of natural speech.

The current set of experiments resulted in a ST(ID) dependence that is identical in form to the Fitts’s law (reviewed in Meyer, Smith and Wright 1982; Plamondon and Alimi 1997): ST = a + b·ln(IDS) and MT = c + d·ln(IDM), where a, b, c, and d are constants, and the subscripts S and M indicate that ID is computed for a speech task or for a movement task. We view this result not as a simple coincidence but, potentially, as revealing a general timing feature of human actions. For example, we would not be surprised to see the time it takes a chess player to make a move in a quick-chess game to show a logarithmic relation to the subjectively perceived complexity of the position on the board –an experiment that to our knowledge has not been performed. In the initial position, when all 32 pieces are on the board but their position is standard, the time is minimal; so, what matters is not the number of pieces but characteristics of their interaction (complexity, as perceived by the player).

As mentioned in the Introduction, it would be more accurate to address Fitts’ law not as a “speed-accuracy trade-off” but rather as a “speed-difficulty trade-off”. The latter expression fits better the accepted formulation of Fitts’ law: MT is a function of an index of difficulty (ID) not a function of an index of accuracy (for example, a measure of dispersion of the final position).

In the previous study (Latash and Mikaelian 2008,Latash and Mikaelian 2010), we observed a linear relation between ST and the product of two quantities, one related to the number of objects (NO) and the other related to the number of object characteristics (NC). To us, the fact that speech time in a picture description task can be described using a single characteristic of a task (IDS) as concisely as movement time in studies of quick-and-accurate limb movements is most encouraging independently of its exact functional form. The linear relation of ST to NO may have a simple explanation of the objects being described sequentially such that ST per object did not depend on the number of objects. The linear relation of ST to NC was a bit more unexpected. One possibility is that the few characteristics used in that study and their simplicity encouraged the subjects to describe them sequentially leading to a linear dependence. On the other hand, we could have studied a relatively linear portion of a logarithmic curve. The current study was designed to explore a broader range of ID while keeping NO constant (NO = 2). And it did lead to a logarithmic ST(ID) relation.

It is tempting to link ST to such characteristics of utterances as the number of words or syllables. In particular, in the studies of very quick speech production by the group of Sternberg (Sternberg et al. 1978, 1988), a number of potential “action units” (elements) have been considered such as words, syllables and stress groups (see also Fowler 1981). However, those studies used a different procedure to address a different question: The subjects were asked to produce very quick utterances known to the subjects in advance to find the relationships between ST and number of words (syllables). As a result, the subjects always uttered the prescribed words, and the mentioned elements could be quantified unambiguously. In contrast, the main purpose of this study has been to discover how ST is affected by ID when the subjects were free to select the lexical material. Hence, in our study, subjects could use different word combinations and different numbers of syllables to describe pictures with the same ID values in different trials. It would indeed be very interesting to address a question whether the lexical choices dictate ST independent of any particular cognitive processes. However, our study was not designed to answer this question, which we may try to address in future.

To use an analogy from limb movement studies, there were attempts to link movement time variations to the number of elements (“submovements”) defined as detectable trajectory hesitations (Meyer et al. 1982, 1990). These studies led to a particular hypothesis on the origin of Fitts’ law. Maybe, analysis at the level of words, syllables and stress groups would also lead to a comparable development.

There is a possibility that the observed ST scaling with ID has a phonetic origin. For example, the observed differences between the CH and IE speaking subjects could be due to the different number of phonemes and/or to the different speech rate. At this point, however, we limit the study to the demonstration of ST(ID) relationships similar to those typical of Fitts’ law. Investigating potential lexical and/or phonetic foundations of the findings may be pursued in future studies.

Reaction Time and Speech Time: Common Origins of Scaling with ID?

In both studies, we observed weak dependences RT(ID) that were sometimes not statistically significant, while the observed RT values were within the range reported for picture description tasks (Smith and Wheeldon 1999; Allum and Wheeldon 2007; Marian, Blumenfeld and Boukrina 2007). However, the observed RT(ID) dependences were qualitatively similar to those of ST(ID). Moreover, they showed similar differences between the groups. In particular, in the first study RT was longer in subjects performing in their second language as compared to their performance in the native language (cf. Elston-Guttler et al. 2005). The same was true for ST (cf. Nissen, Dromey and Wheeler 2007). In the current set of experiments, RT was shorter in the CH group as compared to the IE group. The same was true for ST. We suggest that these similarities may not be coincidental but reflect common rules that define RT(ID) and ST(ID) relations. Hence, we would like to propose that, under the instruction to describe a picture “as fast and accurate as possible”, the cognitive process of task analysis and phrase construction starts before RT and continues until the end of the utterance. If there are differences in the speed of this process between subjects or tasks, the differences start to accumulate from the initiation of the process such that stronger differences are accumulated over ST as compared to RT. This explanation is corroborated by the fact that simply speaking out sets of words (as in the studies of Sternberg et al. 1978, 1988) takes only 20%–25% of the time we observed in our experiments for comparable numbers of words.

According to this scheme, the difference between subjects should accumulate over longer utterances or, in other words, the ST[ln(ID)] relations should differ primarily by their slope (assuming their linearity, supported by the data), not by intercept. This is indeed true for both comparisons between the two groups and within each group. Data in Figure 4 show that the presented linear regressions differ primarily by their slopes, not by the intercepts. The same can be said about RT[ln(ID)] relation illustrated in Figure 2 for the group data.

It is common to take a deep breath before uttering a sentence: Breathing pauses occurring before sentences consisting of 14–24 syllables can take 400–800 ms (Fuchs et al. 2008; note that subjects in that study read sentences, not created them). Longer phrases are preceded by longer breathing pauses. So, it is possible that a substantial portion of the reaction time in our study (over 50%) was related to inhalation in parallel with cognitive processes. We would like to note, however, that our subjects paced the experiment themselves. Therefore, they could (and, anecdotally, they did) take a deep breath prior to pressing the key that triggered the next trial. Nevertheless, we cannot discard the possibility that taking a breath prior to speech initiation could affect our measures of reaction time.

Differences between Languages in Reaction Time and Speech Time

To us (and to all our colleagues with whom we discussed these data), the most unexpected finding has probably been the very large difference in ST between the Chinese group and the English-Russian group. A smaller but still significant advantage of the CH group was seen in RT. To our knowledge, this study is the first to show a significant difference between languages in RT and ST in phrase construction tasks. At this point, we can offer only tentative, speculative hypotheses on possible origins of this finding.

The picture description task may be viewed as involving several stages. The first one is visual analysis of the picture. We do not see reasons to assume that the CH group had an advantage over the IE group at that stage. The next stage involves cognitive analysis of the visual picture and initiating the process of phrase construction. There may be an advantage of the CH group at that stage. In particular, persons from East Asia are known to show a gradient in the effect of verbalization on cognitive tasks, with performance being better for simple tasks and deteriorating when the tasks become more complex (Kim 2008). This gradient is absent in English speaking persons. Our tasks were definitely at the simple side of the spectrum. In addition, the simplicity and schematic nature of the tasks might make them similar to Chinese character recognition, which is also expected to benefit the CH group as compared to the IE group (this is pure speculation).

There is no clear border between the previous stage and the stage of utterance reflected in our ST index: As mentioned earlier, we assume that the processes involved in task analysis and phrase construction, from visual analysis of the picture through the mechanics of voice production, start before the first measurable change in the sound signal (defined as RT) and continue until the end of the utterance.

Several studies reported an increase in speech duration and a decrease of speech rate occurring at grammatical and prosodic junctures (among others Byrd 2000; Byrd and Saltzman 2003; Krivokapić 2007). Thus, the differences in speech time between the Chinese and Indo-European speakers might be a result of their sentence, and more generally, text structure. English is a highly structured language with almost every sentence requiring a subject and a verb. Russian is somewhat less rigid, while spoken Chinese is much more forgiving. When there is no ambiguity in meaning, the subject of a sentence may be omitted. Chinese syntax is highly implicit and can tolerate the omission of, not only a single subject in a sentence, but also several subjects in a group of clauses or even sentences as long as these clauses or sentences are within the same topic chain. It is not unusual to see a single subject that takes several verb phrases without using any conjunctions in a sentence. These particularities of Chinese sentence construction might have contributed to a reduced amount of realized words and, therefore, shorter speech time to describe complex pictures for Chinese speakers in comparison to the Indo-European ones.

One of the obvious differences between the Chinese and Indo-European languages is that the former is a tone language while the latter are stress languages. Tone is an effective channel of information transmission (Brown-Schmidt and Canseco-Gonzalez 2004; Valaki, Maestu, Simos et al. 2004; Lee 2007), while stress typically carries minimal or no information (for example, as in languages with the stress always at a fixed syllable within a word such as Armenian, Polish and others). Assume, for simplicity, that, in a tone language, the total amount of information to be transferred is shared between the lexical material and tones. (Since the tones and lexical material are tightly linked to each other, this assumption is a major simplification made for the purpose of illustration.) Then, to transfer comparable amounts of information may be expected to require less lexical material in a tone language than in a stress one resulting in shorter utterings and shorter ST values. Our results suggest that using tone may be partly responsible for saving over 50% of time to transmit information, at least in simple picture description tasks used in the study. This view is compatible with recent studies showing that speaking a tone language is associated with activation patterns of distinct brain areas that do not show activation in stress language speakers (Klein, Zatorre, Milner and Zhao 2001).

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Jae Kun Shim and Jason Friedman for the vital help with programming. We also thank Dr. Alexander Barulin for many insightful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript and the two anonymous Reviewers for many excellent suggestions.

References

- Allum PH, Wheeldon LR. Planning scope in spoken sentence production: the role of grammatical units. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition. 2007;33:791–810. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.33.4.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branigan HP, Pickering MJ, Stuart AJ, McLean JF. Syntactic priming in spoken production: linguistic and temporal interference. Memory and Cognition. 2000;28:1297–1302. doi: 10.3758/bf03211830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Schmidt S, Canseco-Gonzalez E. Who do you love, your mother or your horse? An event-related brain potential analysis of tone processing in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of Psycholinguist Research. 2004;33:103–135. doi: 10.1023/b:jopr.0000017223.98667.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd D. Articulatory vowel lengthening and coordination at phrasal junctures. Phonetica. 2000;57:3–16. doi: 10.1159/000028456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd D, Saltzman E. The elastic phrase: modeling the dynamics of boundary-adjacent lengthening. Journal of Phonetics. 2003;31:149–180. [Google Scholar]

- De Roo E, Kolk H, Holfstede B. Structural properties of syntactically reduced speech: a comparison of normal speakers and Broca’s aphasics. Brain and Language. 2003;86:99–115. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00538-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte M, Latash ML. Effects of postural task requirements on the speed-accuracy trade-off. Experimental Brain Research. 2007;180:457–467. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-0871-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston-Guttler KE, Paulmann S, Kotz SA. Who’s in control? Proficiency and L1 influence on L2 processing. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2005;17:1593–1610. doi: 10.1162/089892905774597245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrand L, Grainger J. Homophone interference effects in visual word recognition. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology A. 2003;56:403–419. doi: 10.1080/02724980244000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitts PM. The information capacity of the human motor system in controlling the amplitude of movement. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1954;47:381–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitts PM, Peterson JR. Information capacity of discrete motor responses. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1964;67:103–112. doi: 10.1037/h0045689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CA. A relationship between coarticulation and compensatory shortening. Phonetica. 1981;38:35–50. doi: 10.1159/000260013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs S, Hoole P, Vornwald D, Gwinner A, Velkov H, Krivokapic J. In: Sock R, Fuchs S, Laprie Y, editors. The control of speechbreathing in relation to the upcoming sentence; Proceedings of the 8th International Seminar on Speech Production; December 8-12, 2008; Strasbourg, France. 2008. pp. 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Goozee JV, Stephenson DK, Murdoch BE, Darnell RE, Lapointe LL. Lingual kinematic strategies used to increase speech rate: comparison between younger and older adults. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics. 2005;19:319–334. doi: 10.1080/02699200420002268862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JK. Phonological neighborhood effects in aphasic speech errors: spontaneous and structured contexts. Brain and Language. 2002;82:113–145. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(02)00001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman SR, Latash ML, Gottlieb GL, Almeida GL. Kinematic description of variability of fast movements: Analytical and experimental approaches. Biological Cybernetics. 1993;69:485–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS. Culture and the cognitive and neuroendocrine responses to speech. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:32–47. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D, Zatorre RJ, Milner B, Zhao V. A cross-linguistic PET study of tone perception in Mandarin Chinese and English speakers. Neuroimage. 2001;13:646–653. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivokapi J. Prosodic planning: Effects of phrasal length and complexity on pause duration. Journal of Phonetics. 2007;35:162–179. doi: 10.1016/j.wocn.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML, Mikaelian IL. In: Sock R, Fuchs S, Laprie Y, editors. Linear and logarithmic speed-accuracy trade-offs in speech production; Proceedings of the 8th International Seminar on Speech Production; December 8-12, 2008; Strasbourg, France. 2008. pp. 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Latash ML, Mikaelian IL. How long does it take to describe what one sees? The first step using picture description tasks. Human Movement Science. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2009.11.004. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY. Does horse activate mother? Processing lexical tone in form priming. Language and Speech. 2007;50:101–123. doi: 10.1177/00238309070500010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln AE, Long DL, Baynes K. Hemispheric differences in the activation of perceptual information during sentence comprehension. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher BA, Manschreck TC, Linnet T, Candela S. Quantitative assessment of the frequency of normal associations in the utterances of schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;78:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marian V, Blumenfeld HK, Boukrina OV. Sensitivity to phonological similarity within and across languages. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 2008;37:141–170. doi: 10.1007/s10936-007-9064-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer DE, Smith JE, Kornblum S, Abrams RA, Wright CE. Speed-accuracy tradeoffs in aimed movements: Toward a theory of rapid voluntary action. In: Jeannerod M, editor. Attention and Performance XIII. Hillsdale NJ: Erlbaum; 1990. pp. 173–225. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer DE, Smith JE, Wright CE. Models for the speed and accuracy of aimed movements. Psychological Reviews. 1982;89:449–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen SL, Dromey C, Wheeler C. First and second language tongue movements in Spanish and Korean bilingual speakers. Phonetica. 2007;64:201–216. doi: 10.1159/000121373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plamondon R, Alimi AM. Speed/accuracy trade-offs in target-directed movements. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1997;20:1–31. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x97001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remington R. Processing of phonemes in speech: a speed-accuracy study. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1977;62:1279–1290. doi: 10.1121/1.381653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RA, Zelaznik H, Hawkins B, Frank JS, Quinn JT. Motor output variability: A theory for the accuracy of rapid motor acts. Psychol Rev. 1979;86:415–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Goffman L. Stability and patterning of speech movement sequences in children and adults. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 1998;41:18–30. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4101.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, Wheeldon L. High level processing scope in spoken sentence production. Cognition. 1999;73:205–246. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(99)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg S, Knoll RL, Monsell S, Wright CE. Motor programs and hierarchical organization in the control of rapid speech. Phonetica. 1988;45:175–197. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg S, Monsell S, Knoll RL, Wright CE. The latency and duration of rapid movement sequences: Comparisons of speech and typing. In: Stelmach GE, editor. Information Processing in Motor Control and Learning. Academic Press; New York: 1978. pp. 117–152. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg S, Wright CE, Knoll RL, Monsell S. Motor programs in rapid speech: Additional evidence. In: Cole RA, editor. Perception and Production of Fluent Speech. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1980. pp. 507–534. [Google Scholar]

- Valaki CE, Maestu F, Simos PG, Zhang W, Fernandez A, Amo CM, Ortiz TM, Papanicolaou AC. Cortical organization for receptive language functions in Chinese, English, and Spanish: a cross-linguistic MEG study. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42:967–979. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitevitch MS. The neighborhood characteristics of malapropisms. Language and Speech. 1997;40:211–228. doi: 10.1177/002383099704000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitevitch MS. The influence of phonological similarity neighborhoods on speech production. Journal of Experimental Psycholpgy: Learning, Memory and Cognition. 2002;28:735–747. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.28.4.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]