Abstract

Dysplastic features of erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages were observed in a cat with acute erythroid leukemia. We demonstrated that flow cytometry analysis of the expression of glycophorin A and CD71 by neoplastic cells can be helpful in the diagnosis of this type of feline leukemia.

Résumé

Érythroleucémie aiguë avec de la dysplasie multilignées chez un chat. Les caractéristiques dysplasiques des lignées érythrocytaire et mégacaryocytaire ont été observées chez un chat atteint d’érythroleucémie aiguë. Nous avons démontré que l’analyse par cytométrie de flux de l’expression de glycophorine A et CD71 par les cellules néoplasiques peut être utile pour diagnostiquer ce type de leucémie féline.

(Traduit par Isabelle Vallières)

The French-American-British (FAB) classification of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) includes a category, M6 AML, in which there is an excess of myeloblasts in a predominantly erythroid background (1). The FAB classification does not include a category for cases where the neoplastic cells are immature erythroid cells without there being an excess of myeloblasts (2). The newer World Health Organization (WHO) classification of acute erythroid leukemias recognizes 2 subtypes based on the presence or absence of a significant myeloid component: 1) erythroleukemia (erythroid/myeloid) with ≥ 20% myeloblasts; and 2) pure erythroid with > 80% of the marrow cells being erythroid and no evidence of a significant myeloblastic component (< 3%) (3). Such a classification scheme can be adapted for use in veterinary medicine. Indeed, a recognized leukemia with respect to cytomorphologic, cytochemical, and immunophenotypic characteristics is placed in a previously defined category or the former classification scheme needs to be revised. Here, we describe a cat with erythroid leukemia which cannot easily be classified by the WHO criteria or by the FAB system. In this patient, we used flow cytometry to evaluate the expression of CD71 and glycophorin A by neoplastic cells.

Case description

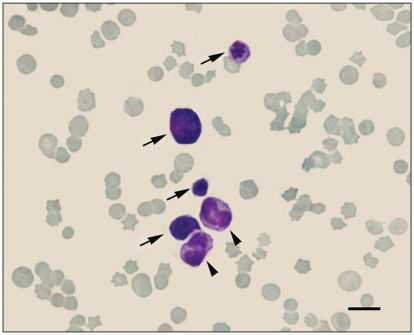

An 8-year-old 5.8-kg female domestic shorthair cat was presented with a 2-week history of severe petechiae and anorexia. On admission, the cat was recumbent and had a body condition score of 4. Physical examination revealed multifocal petechiae and ecchymoses, icteric mucous membranes, dehydration, superficial lymphadenomegaly, and massive splenomegaly and hepatomegaly which were confirmed by abdominal radiography. The hematological (Vet Hema-Screen 18; Hospitex Diagnostics, Sesto Fiorentino, Italy) and biochemical findings are shown in Table 1. The cat was positive for feline leukemia and negative for feline immunodeficiency virus (PetChek FeLV/FIV ELISA; IDEXX Corp, Westbrook, Maine, USA). A marked thrombocytopenia (16.5 × 10μL) and a macrocytic hypochromic anemia were detected. Blood chemistry showed a marked increase in lactate dehydrogenase (1160 U/L) and bilirubin (46.6 mg/L). A few circulating erythroid precursors including rubriblasts, rubricytes, and metarubricytes were typically found (Figure 1), leading us to perform a bone marrow (BM) examination.

Table 1.

Hematological and serum biochemical findings in a cat with acute erythroid leukemia

| Parameter | Results | Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| Hematocrit (%) | 25.0 | 26.5–45.0 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 60.0 | 81–165 |

| Total red cell count (1012/L) | 3.9 | 5.5–9.5 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fL) | 65 | 40–55 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (%) | 26 | 31–37 |

| Reticulocytes (109/L) | 4.8 | < 15 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 16.5 | 150–450 |

| All nucleated cells (106/L) | 22 500 | 6000–19 000 |

| Segmented neutrophils (106/L) | 12 260 | 3000–12 500 |

| Band neutrophils (106/L) | 4840 | 0–400 |

| Metamyelocytes (106/L) | 900 | 0 |

| Myelocytes (106/L) | 110 | 0 |

| Eosinophils (106/L) | 560 | 0–1500 |

| Monocytes (106/L) | 230 | 0–700 |

| Lymphocytes (106/L) | 900 | 1500–8000 |

| Erythroid precursors (106/L) | 2700 | 0 |

| Rubriblasts (106/L) | 550 | 0 |

| Rubricytes (106/L) | 450 | 0 |

| Metarubricytes (106/L) | 1700 | 0 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mmol/L) | 8.8 | 4.6–11.8 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 84.0 | 70.7–168.0 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 40 | 10–78 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 86 | 16–64 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 1160 | 51–350 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 79.7 | 1.7–8.5 |

Figure 1.

Erythroid precursors (arrows) and 2 metamyelocytes (arrowheads) in the peripheral blood (Wright–Giemsa stain). Bar = 10 μm.

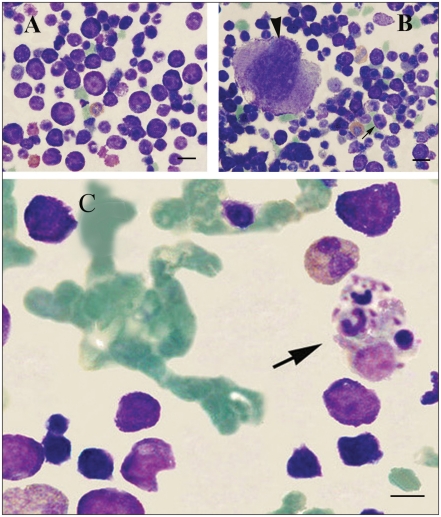

Bone marrow core biopsy revealed a cellularity of approximately 50%. A 500-cell differential count in a BM aspiration smear is presented in Table 2. Cytologic analysis of the BM aspirate showed that > 60% of the nucleated cells belonged to the erythroid series (myeloid/erythroid ratio: 0.65:1). Rubriblasts constituted 27.8% of all nucleated cells (ANC) and 46.2% of all erythroid cells. Morphologically, rubriblasts have a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio and a deeply basophilic cytoplasm. Their nuclei were round and central with 1 or 2 prominent and occasionally bizarre nucleoli (Figure 2A). Binucleation, asynchrony of nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation and cytoplasmic vacuoles were also observed in some erythroblasts (Figure 2B). A few azurophilic granules were discernible in the cytoplasm of some neoplastic cells. Thirty-five percent of the erythroid cells exhibited dysplastic features. Occasional hemophagocytosis was another abnormal feature observed in the BM of the patient (Figure 2C). Dysmegakaryocytopoiesis, including micromegakaryocytes, large megakaryocytes with nuclear hypolobulation (Figure 2B), and giant platelets were seen in approximately 30% of cells. Cellular areas of the slide contained 4 to 5 megakaryocytes per low-power field (×10 objective).

Table 2.

Differential count of cells in bone marrow from the cat

| Parameter | % |

|---|---|

| Erythroid series | 60.2 |

| Rubriblasts | 27.8 |

| Prorubricytes | 5.4 |

| Rubricytes | 11.0 |

| Metarubricytes | 16.0 |

| Myeloid series | 39.2 |

| Myeloblasts | 2.4 |

| Promyelocytes | 2.0 |

| Myelocytes | 3.6 |

| Metamyelocytes | 5.6 |

| Bands | 19.8 |

| Neutrophils | 4.8 |

| Eosinophils | 0.2 |

| Monoblasts | 0.2 |

| Promonocytes | 0.4 |

| Monocytes | 0.2 |

| Myeloid:erythroid ratio | 0.65:1 |

| Other cell types | 0.6 |

| Macrophages | 0.4 |

| Lymphocytes | 0.2 |

Figure 2.

Bone marrow cytology. A — Rubriblasts with prominent, bizarre nucleoli and dark blue cytoplasm. B — Binucleation in some neoplastic cells (arrow). Arrowhead indicates a moderate-sized, monolobular megakaryocyte typical of dysmegakaryopoiesis. C — Phagocytosed neutrophils and cellular debris along with a hematogone within the cytoplasm of a histiocyte (Wright — Giemsa stain). Bars = 20 μm in panels (A) and (B), and 10 μm in panel (C).

Perls’ staining was carried out on the BM aspirate. Ring sideroblasts, which are erythroid precursors with deposits of iron around the nucleus, were seen in the Perls’ stained smears. These cells constitute approximately 25% of the erythroid cells.

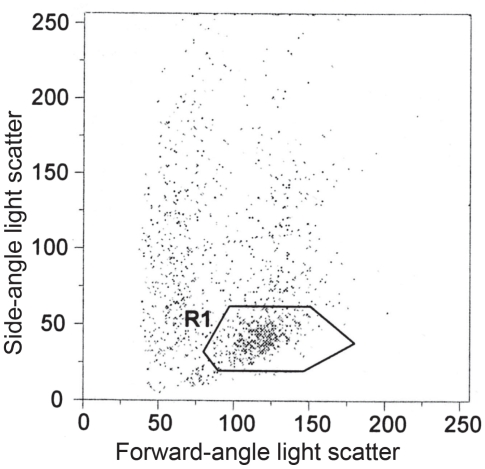

The following cytochemical stains on blood and BM smears were performed using a commercial kit (Leucognost, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany): leukocyte alkaline phosphatase (LAP), Sudan black B (SBB), chloroacetate esterase (CAE) and α-naphthyl acetate esterase (NAE), myeloperoxidase (MPO), and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). Flow cytometric analyses of blood and BM mononuclear cells using antibodies (all from Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) against human CD10, CD13, CD33, CD34, CD61, CD71, and glycophorin A were performed with ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA)-anticoagulated blood and BM samples from the patient in duplicate. For flow cytometry, an irrelevant isotype-matched antibody (Dako) was used as negative control to exclude non-specifically labeled cells from the calculation. Blood samples from 5 age-matched, clinically healthy cats were used as a control. For each flow cytometric test, 50 μL of marrow or peripheral blood was placed in a 6-mL sterile tube. Then the samples were incubated for 15 min at 4°C in the dark with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antibodies. At the end of the incubation time, 0.5 mL of erythrocyte lysis buffer composed of 0.3% formic acid solution in distilled water was added and mixed for 35 s. Then, the tubes were centrifuged and the cell pellets were resuspended in 750 μL of Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline solution and fixed with 100 μL of 1% paraformaldehyde solution. A flow cytometer (Partec PAS III, Münster, Germany) was used for analysis. In the marrow, a cell population with light-scattering characteristics of blasts was observed (Figure 3), analyzed by 1-color fluorescence histograms and displayed on a logarithmic scale. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells identified by light scattering were also analyzed. The results are reported as a percentage of the total gated population.

Figure 3.

Forward-side-scatter analysis detected a cell population with characteristics of blasts (R1). This gate was used for reanalysis of the surface antigens.

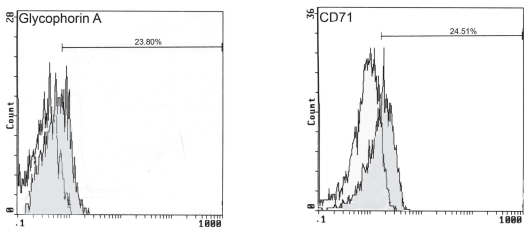

Cytochemical staining revealed that neoplastic cells were negative for LAP, SBB, CAE, NAE, MPO, and PAS. The panel of surface markers detected by flow cytometry is listed in Table 3. A significant degree of positive reactions to erythroid markers including glycophorin A and CD71 was observed (Figure 4). Control cats were negative for all of these markers, excluding the possibility of nonspecific binding of these antibodies to feline molecules.

Table 3.

Peripheral blood and bone marrow cell markersa

| Cell marker | Peripheral blood (%) | Bone marrow (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Glycophorin A | 14.0 | 23.8 |

| CD71 | 19.0 | 24.5 |

| CD10 | 3.0 | 7.0 |

| CD13 | 20.0 | 15.0 |

| CD33 | 5.5 | 11.0 |

| CD34 | 3.0 | 5.5 |

| CD61 | 13.2 | 13.3 |

The results are expressed as percentage of fluorescent-labeled cells among mononuclear cells.

Figure 4.

Flow cytometric histograms showing the control isotype and the cells labelled for glycophorin A and CD71.

A final diagnosis of acute erythroid leukemia was made. One day after admission, the condition of the cat deteriorated rapidly and the owners elected euthanasia. The animal was submitted for necropsy. At necropsy, the hallmark lesions were an icteric carcass with massive splenomegaly, hepatomegaly and generalized lymph node enlargement. Histologically, hepatic lipidosis with bile canaliculi obstruction as well as extramedullary hematopoiesis in the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes were observed. The extramedullary hematopoiesis involved cells of the erythroid, myeloid, and megakaryocytic lineages but rubriblasts were predominant, suggestive of neoplastic infiltration.

Discussion

The criteria of the FAB for defining AML-M6 exclude cases with minimal nonerythroid components (4). Cases with predominantly erythroid precursors that lacked significant nonerythroid cells (pure erythroleukemias) were later dubbed AML-M6 variant or AML-M6b and, in the veterinary literature, M6Er (3–5). Multilineage dysplasia has not been included in the set of criteria for defining M6Er (6–8); therefore, the FAB criteria are insufficient to classify the leukemia in the present cat. M6a is now called acute erythroleukemia (erythroid/myeloid) or acute erythroid/myeloid leukemia, and M6b is called pure erythroid leukemia (4). The WHO has classified acute erythroleukemia (erythroid/myeloid) as well as pure erythroid leukemia under the category of AML not otherwise categorized (AML-NOC) (9). One of the other new categories of AML based on the WHO classification is AML with multilineage dysplasia. Zini and d’Onofrio (10) suggested an epitaph for erythroleukemia because the application of the new WHO standards in a retrospective review of 13 human cases formerly diagnosed as M6a or M6b by FAB standards resulted in a change in diagnosis to AML with multilineage dysplasia in all cases. Domingo-Claros et al (3) also reported that most of the 62 patients in their study had evidence of multilineage dysplasia. It is recommended by the WHO committee that in these cases when 50% or more of the cells in 2 or more cell lines are dysplastic, the diagnosis should be AML with multilineage dysplasia, acute erythroid/myeloid type (4,9). The cat in the present study had 27.8% rubriblasts, 60% erythroid marrow, with < 50% dysplastic changes, and significantly < 20% myeloblasts within the non-erythroid compartment (myeloblasts = 2.4% of all nucleated cells). It does not meet the criteria for either type of erythroid leukemia as outlined within the WHO guidelines and does not meet the criteria for AML with multilineage dysplasia. Mazzella et al (11) have developed a modified classification scheme for M6: 1) M6a (erythroid ≥ 50% with ≥ 30% myeloblasts, based on the myeloid population), corresponding with the traditional FAB M6 category; 2) M6b or pure erythroleukemia [erythroid ≥ 50% with pronormoblasts (rubriblasts) ≥ 30%, based on the erythroid population]; and 3) M6c (erythroid ≥ 50% with ≥ 30% myeloblasts and ≥ 30% pronormoblasts, based on the myeloid and erythroid population respectively). They also stated that multilineage dysplasia may be present (11). Our case fits the M6b subtype described by Mazzella et al (11).

Although the most dysplastic features were observed in the erythroid and megakaryocytic series, hemophagocytosis was shown in a few granulocytic elements as previously reported in humans (2,12).

It is hypothesized that the macrocytic red cells and megaloblastemia in this disorder are the result of megaloblastic precursors in the marrow (13). A defect in nucleic acid synthesis or mitosis leads to asynchronous maturation of the nucleus and cytoplasm, forming megaloblasts and giant metarubricytes, and eventually macrocytic red cells in circulation (13,14). This may be due to prolonged dysplastic erythroid production resulting from FeLV-induced myelodysplasia (15).

Extramedullary hematopoiesis in lymph nodes, spleen, and liver has been previously reported in a cat with erythroleukemia and is probably related to ineffective marrow hematopoiesis (16). In this cat, the large numbers of rubriblasts in the spleen, liver, and nodes might be due to neoplastic infiltration. The results of cytochemical reactions in this patient are in line with those reported by others (16).

Marked thrombocytopenia in this cat occurred in association with neoplasia. Immune-mediated platelet destruction plays a role in the pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia associated with neoplasia (15). In addition, FeLV may destroy megakaryocytes (17). Dysplastic megakaryopoiesis may also contribute to the pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia.

Myeloproliferative disease is more prevalent in the cat than in other domestic species and usually is associated with FeLV. Hematopoietic precursors are infected with FeLV, and viral proteins are thought to interact with host cell products that are important in cell proliferation, thereby resulting in recombination or rearrangement events involving host protooncogenes (15).

The CD panel evaluated in this cat is a standard panel of surface markers that is used for the evaluation of human patients with AML. Analysis of most of these surface molecules has been recommended by the American College of Veterinary Pathologists Oncology Committee (4). Antigens expressed by more than 20% of the cells were considered positive (18). Glycophorin A and CD71 were significantly expressed by the neoplastic cells of the bone marrow, and this confirmed the diagnosis of erythroid leukemia.

Hasserjian et al (2) noted that neoplastic cells in erythroid leukemia are primitive and sometimes barely recognizable as erythroid without the aid of immunophenotypic analysis or electron microscopy. Diagnosis of this form of leukemia can be difficult because of the lack of an excess of myeloblsts or circulating leukemic cells (2). In humans, the well-known markers for erythroleukemia include glycophorin A and transferrin receptor (CD71) (19). We demonstrated that the use of anti-human antibodies for flow cytometry analysis of the expression of glycophorin A and CD71 by neoplastic cells can improve the ability to correctly diagnose this type of feline leukemia. Given that the patient suddenly showed symptoms of the disease and that she had not even lost weight on admission, it seems that this kind of leukemia is highly aggressive.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Hamid Reza Haddadzadeh, Masoud Rajabioun, and Hossein Jarolmasjed for technical assistance. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, et al. Proposed revised criteria for the classification of acute myeloid leukemia. A report of the French-American-British Cooperative Group. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:620–625. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-4-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasserjian RP, Howard J, Wood A, et al. Acute erythremic myelosis (true erythroleukaemia): A variant of AML FAB-M6. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:205–209. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domingo-Claros A, Larriba I, Rozman M, et al. Acute erythroid neoplastic proliferations. A biological study based on 62 patients. Haematologica. 2002;87:148–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McManus PM. Classification of myeloid neoplasms: A comparative review. Vet Clin Pathol. 2005;34:189–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-165x.2005.tb00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg SL, Noel P, Klumpp TR, Dewald GW. The erythroid leukemias: A comparative study of erythroleukemia (FAB M6) and Di Guglielmo disease. Am J Clin Oncol. 1998;21:42–47. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199802000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain NC. Classification of myeloproliferative disorders in cats using criteria proposed by the Animal Leukemia Study Group: A retrospective study of 181 cases (1969–1992) Comp Hematol Int. 1993;3:125–134. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain NC, Blue JT, Grindem CB, et al. Proposed criteria for classification of acute myeloid leukemia in dogs and cats. Vet Clin Pathol. 1991;20:63–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-165x.1991.tb00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raskin RE. Myelopoiesis and myeloproliferative disorders. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1996;26:1023–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(96)50054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2002;100:2292–2302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zini G, d’Onofrio G. Epitaph for erythroleukemia. Haematologica. 2004;89:ELT11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazzella FM, Kowal-Vern A, Shrit MA, et al. Acute erythroleukemia: Evaluation of 48 cases with reference to classification, cell proliferation, cytogenetics, and prognosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110:590–598. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/110.5.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roggli VL, Saleem A. Erythroleukemia: A study of 15 cases and literature review. Cancer. 1982;49:101–108. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820101)49:1<101::aid-cncr2820490121>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perkins P. Hematologic abnormalities accompanying leukemia. In: Feldman BF, Zinkl JG, Jain NC, editors. Schalm’s Veterinary Hematology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 740–746. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch VM, Dunn J. Megaloblastic anemia in the cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1983;19:873–880. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thrall MA, Weiser G, Jain N. Laboratory evaluation of bone marrow. In: Thrall MA, editor. Veterinary Hematology and Clinical Chemistry. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2004. pp. 147–178. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Comazzi S, Paltrinieri S, Caniatti M, De Dominici S. Erythremic myelosis (AML6er) in a cat. J Feline Med Surg. 2000;2:213–215. doi: 10.1053/jfms.2000.0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shelton GH, Linenberger ML. Hematologic abnormalities associated with retroviral infections in the cat. Semin Vet Med Surg (Small Anim) 1995;10:220–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villeneuve P, Kim DT, Xu W, et al. The morphological subcategories of acute monocytic leukemia (M5a and M5b) share similar immunophenotypic and cytogenetic features and clinical outcomes. Leuk Res. 2008;32:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park S, Picard F, Dreyfus F. Erythroleukemia: A need for a new definition. Leukemia. 2002;16:1399–1401. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]