Abstract

BACKGROUND

Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) decreases the shortage of liver grafts for patients in need of a liver transplant, but involves two patients – a recipient and a living donor. Despite the magnitude of the procedure for the LDLT donor, only a few studies have investigated the effect of LDLT on the quality of life (QOL) of the donor.

METHODS

We performed a systematic search of the MEDLINE database to identify peer-reviewed articles assessing QOL in adults after LDLT donation.

RESULTS

Nineteen studies describing 768 unique donors met our inclusion criteria for this review. The median number of donors enrolled in each study was 30 (range 10–143) and the median follow-up 10.4 months (range 6–51.3). Prior to donation, donor QOL is significantly better than in control adult populations across all measured QOL domains. Within the first 3 months after donation, physical domains of QOL are significantly worse than pre-donation levels but return to baseline levels at 6 months in the majority (80–93%) of patients. Mental domains of QOL remain unchanged throughout the donation process. Common donor concerns after LDLT include bloating, loss of muscle tone, poor body image, and fatigue.

DISCUSSION

Based on our review of the existing literature, most LDLT donors return to baseline QOL within 6 months. However, there is a lack of long-term data on donor QOL after LDLT and few standardized assessments include measures of common patient concerns. Additional studies are necessary to develop a comprehensive risk profile for LDLT that includes a rigorous assessment of donor QOL.

Keywords: health-related quality of life, liver donation, patient-reported outcomes

Introduction

Liver transplantation is the only life-saving intervention for patients with end stage liver disease (ESLD) and appropriate patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, there is a shortage of available grafts for liver transplantation.(1) One strategy to alleviate the shortage of liver grafts has been the introduction of living donor liver transplantation (LDLT), in which part of the living donor liver is transplanted into the recipient, rather than using an organ from a deceased donor. LDLT donors are typically healthy adults who do not derive any medical benefit from the procedure for themselves. Therefore, in order to justify exposing LDLT donors to such an operation, it is imperative to have a broad and clear understanding of the potential effects of LDLT on the donor.

While the potential mortality and morbidity of LDLT donors have been described (2–4), the effects of LDLT on the donors' quality of life (QOL) have not been well characterized. Donor death is the most serious complication after LDLT, with estimated mortality at 0.28 to 1.0 percent, however, the exact risk cannot be precisely quantified due to the lack of a centralized database measuring donor outcomes.(2, 5) Short-term post-operative complications after LDLT have been well characterized, with approximately 5 percent of donors experiencing a bile leak and between 9 to 19 percent of patients experiencing morbidity related to the abdominal incision.(2) The sizeable minority of patients that experience medical morbidity underlies the need for improved measurement of related parameters such as donor well-being and QOL, which are typically more difficult to quantify.

At its broadest, QOL can be defined as “an overall sense of well-being, including aspects of happiness and satisfaction with life as a whole”. This definition, proposed by the Center for Disease Control, includes specific, measurable concepts such as mental well being, physical functioning, and overall health status, which in turn may be influenced by multiple factors, such as occupational and marital status.(6) There are a number of methods to assess patient QOL including physician ratings, open-ended patient interviews, and standardized patient-reported outcome measures.

Within this last category of assessments, there is a range of focus from generic QOL instruments to more disease specific instruments. Generic QOL instruments ask questions general enough for broad applicability including use among individuals in good health. On the other hand, targeted measures may focus on specific symptoms (e.g. pain, mood) that are common in many health conditions or concerns and symptoms specific to a disease or to its treatment. Among the generic instruments, the Short Form-36 (SF-36) (7, 8) is the most widely employed and has been used across a number of patient populations. In contrast, disease specific instruments, such as the Liver Disease Quality of Life survey (LDQOL), have been created to better characterize QOL of a targeted patient population, namely, chronic liver disease patients. (9, 10)

In order to synthesize the available data on living liver donor QOL, we performed a systematic review of the literature. Specifically, we aimed to elucidate areas of specific concern for these donors and to highlight areas of focus for future research.

Methods

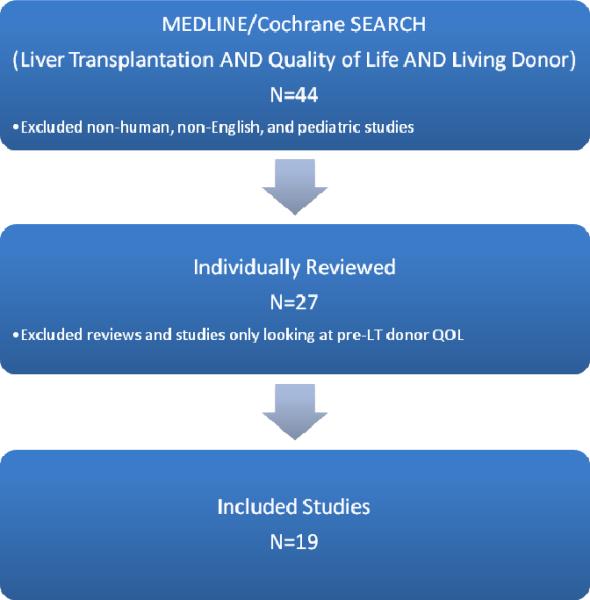

We performed a systematic search of the MEDLINE database (1969 to 2009) to identify articles assessing QOL in living donors after LDLT. Publications were included if they were original articles utilizing a donor-reported QOL assessment after liver donation. To obtain the most thorough coverage of articles, we constructed a search for MeSH terms “liver transplantation” (which includes all combinations of the terms liver or hepatic and transplant or graft) AND “living donor” AND “quality of life”. We also included any citations using the keywords QOL, HRQL, OR HRQOL (i.e. health related quality of life) in combination with “liver transplantation”. We limited our search to those publications relevant to humans and available in English. We categorized the relevant articles by study design (prospective or cross-sectional) and type of instrument used to measure QOL.

In the SF-36, one of the most commonly used generic surveys, QOL is divided into physical subscales (physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, and general health) and mental subscales (vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health). In turn, those subscales can be combined into a physical composite score (PCS) and a mental composite score (MCS). Similarly, PCS and MCS can be derived from the shorter SF-12 QOL survey. In the norm-based, general population scoring, the mean score on each composite score is 50 with a standard deviation of 10.(11) For the studies that utilized the those two generic instruments, the SF-36 and SF-12, we calculated the Physical Composite Scores (PCS) and Mental Composite Scores (MCS) using established scoring criteria if these scores were not provided in the original manuscript.(11)

Results

Our original search strategy identified 44 citations. After limiting the articles to those in English describing adult, human donors, 27 articles remained for individual review. We further excluded review articles and articles that exclusively investigated QOL in donors prior to LDLT. Nineteen studies describing 768 unique donors were included in this review.

Study Methodology

Thirteen (68%) of the 19 studies had a cross sectional design and six (32%) had a prospective design. Seventeen studies (90%) used a validated generic QOL instrument, while two studies (10%) utilized a non-validated interview. Among the seventeen studies using a validated instrument, thirteen (76%) utilized one of the generic QOL instruments, either SF-36 or SF-12 (Table 1). Furthermore, two (12%) studies employed the World Health Organization Quality of Life – BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) and two (12%) studies employed the Anamnestic Comparative Self-Assessment Scale (ACSA). (Table 2)

Table 1.

Quality of Life in Living Donors – Studies utilizing the Short Form 36 (SF-36) or Short Form 12 (SF-12) instruments

| Author | Year | N | Design | PCS | MCS | Mean follow-up (months) | Control Composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dubay | 2009 | 143 | Cross-sectional | 56.4 | 51.2 | 27 | Normative population |

| Feltrin | 2008 | 10 | Cross-sectional | 55.6 | 46.4 | 16.2 | Normative population |

| Erim | 2007 | 123 | Prospective | 56.3 | 49.9 | 3 | Normative population |

| Sevmis | 2007 | 46 | Cross-sectional | N/A | N/A | 12 | -- |

| Chan | 2006 | 30 | Prospective | 55.1 | 49.8 | 12 | -- |

| Miyagi | 2005 | 48 | Cross-sectional | 55.5 | 55.0 | 51.3 | Normative population |

| Humar | 2005 | 37 | Cross-sectional | N/A | N/A | 6 | -- |

| Verbesey | 2005 | 47 | Prospective | 61.4 | 57.4 | 12 | -- |

| Basaran | 2003 | 15 | Cross-sectional | 53.5 | 47.2 | 63 | Healthy adults |

| Karilova | 2002 | 22 | Cross-sectional | 52.9 | 50.7 | N/A | Normative population |

| Kim-Schluger | 2002 | 30 | Cross-sectional | 53.0 | 51.7 | 9.3 | Normative population |

| Beavers | 2001 | 27 | Cross-sectional | N/A | N/A | 20 | Normative population |

| Trotter | 2001 | 24 | Cross-sectional | 52.8 | 52.7 | 13.7 | Normative population |

PCS – Physical composite score

MCS – Mental composite score

N/A – not available

Mean Normative PCS and MCS scores: 50.0 ± 10.0

Table 2.

Quality of Life in Living Donors – Studies not utilizing Short Form 36 (SF-36) or Short Form 12 (SF-12) instrument

| Author | Year | N | Design | Instrument | Mean follow-up (months) | Control | Control Composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kusakabe | 2008 | 18 | Cross-sectional | Interview | N/A | No | -- |

| Hsu | 2006 | 35 | Cross-sectional | WHOQOL-BREF | 12 | Yes | Normative Sample |

| Parolin | 2004 | 19 | Cross-sectional | Interview | 13 | No | -- |

| Walter | 2003 | 28 | Prospective | WHOQOL-BREF | 6 | Yes | Normative population |

| Walter | 2002 | 23 | Prospective | ACSA | 6 | Yes | Healthy adults |

| Pascher | 2002 | 43 | Prospective | ASCA | 12 | Yes | Healthy adults |

WHOQOL-BREF – World Health Organization Quality of Life – BREF

ASCA – Anamnestic Comparative Self-Assessment Scale

The median number of donors enrolled in each of the studies was 30 with a range of 10–143. The prospective studies followed donors for a median of 9 months (range: 3–12 months) and the cross-sectional studies assessed QOL at a median of 13.7 months (range: 6–51.3 months) post-donation. Thirteen (68%) of the studies made explicit comparisons to a control group. The control comparisons were either the SF-36 general population norms or data collected concurrently from a cohort of healthy adults.

Study Findings

Based on our review, donor QOL is equal to or significantly higher than normal adult populations prior to donation across all measured domains of the QOL scales.(12–14) For example, in the Verbesey et al. report, 47 donors reported nearly half a standard deviation above the normative mean for physical and mental functioning on the SF-36, prior to donation.(14) Although they did not make an explicit comparison to the available norms, review of the pre-donation SF-36 data from Chan et al. suggests a similar pre-donation pattern.(13) Six to twelve months after LDLT donation, the majority of donors report their overall QOL to be equivalent to or better than a normative general population or a control population of healthy adults.(14–22) A few illustrative examples suggest that, in the short-term, donor QOL remains reasonably intact. In a sample of 28 donors 6 months post LDLT, Walter et al. found that while some WHOQOL-BREF domain scores had worsened compared to pre-donation values, scores on the QOL instrument were still higher than the general population.[20,21] Similarly, support for this finding is seen in Trotter's cross-sectional study of 24 donors, which reported donor SF-36 scores equivalent to or better than normative data.[19] Despite the overall stability in donor QOL after donation, it is not the case that all donors fare equally well in the first year after donation. In fact, 7 to 20 percent of LDLT donors experience a reduced QOL after donation compared to their pre-donation QOL or compared to the control group.(18, 20, 23) The issue of long-term outcomes remains an open question though. Future research may be informed by more closely examining the typical trajectory and correlates of LDLT donation.

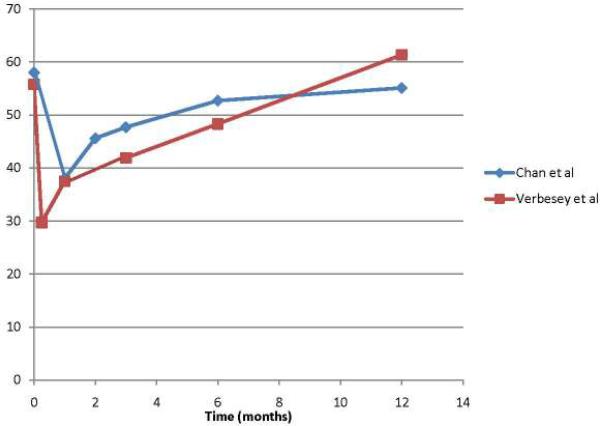

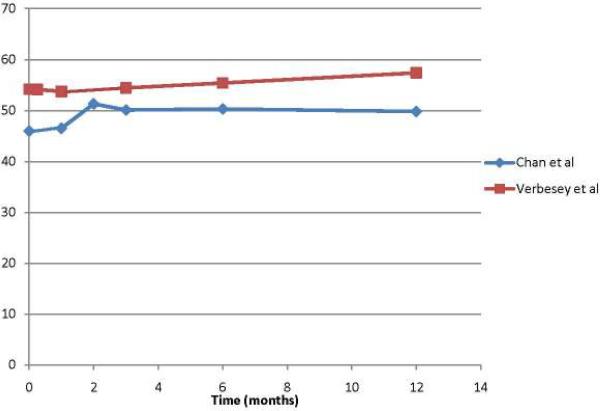

That said, the existing literature does provide a snapshot of the typical trajectory of physical and mental QOL following LDLT donation. Not surprisingly, donors experience the most impact on their physical well-being within the first three months of donation. Verbesey and Chan each reported on less than 50 liver donors apiece, but represent the most rigorous prospective studies assessing donor QOL in any systematic fashion in our review. Of note, they report similar statistically and clinically significant drops in patient-reported physical function immediately following donation. (Figure 2) However, donor physical function returns to near normal levels by six months and in the case of the Verbesey study, donors' PCS scores at 12 months surpassed pre-donation.(13, 14) (Figure 2) According to Hsu et al, the most common physical complaints in donors during the post-operative period include throbbing, itching and/or numbness around the surgical site, followed by reduced general physical vigor, sleep disturbance and slowed reaction ability.(24) In contrast with perceived physical function, donors' psychological function following donation remain stable when compared to normative controls, as demonstrated in the Verbesey and Chan cohorts.(13, 14) (Figure 3) By and large, scores on mental well-being measures remain equivalent to normative populations. (23, 25)

Figure 2.

Physical Composite Scores (PCS) in Donorsbefore and 12 months after liver transplantation

Figure 3.

Mental Composite Scores (PCS) in Donors before and 12 months after liver transplantation

Based on extant data, donors typically report decrements in physical well-being associated with the immediate post-operative period that tend to recover to baseline levels within a year. Mental well-being appears to remain comparable to normative populations over the same time period.

While such general patterns of donor QOL are useful for generalization, not all donors will follow a similar trajectory. Unfortunately, the longitudinal studies of donor QOL have not rigorously addressed the issue of predicting poor outcome, likely due to low statistical power to model these associations. However in a recent cross-sectional report, Dubay et al. failed to find predictors of donor PCS scores using the SF-36.(26)

However, with respect to mental well-being, there have been some hypothesis-generating findings. It appears that the indication for liver transplantation in the LDLT recipient is correlated with donor QOL prior to donation. For instance, donors who donated to LDLT recipients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and those who urgently donated for LDLT recipients with acute liver failure (ALF) have a significantly worse SF-36 MCS prior to donation when compared to a normative population. Specific SF-36 MCS subscales that are significantly lower in the ALF LDLT donor group than the non-urgent LDLT donor group are bodily pain, vitality, social functioning, and emotional well being. Three months after transplantation the mental QOL in ALF and HCC donors are not significantly different from a normative population.(12) Based on a study of 49 donors by Humar et al. right lobe donation versus left lateral segment donation does not impact donor QOL.(27) Furthermore, in studies by Kim-Schluger et al. (12) and Erim et al.(23) MCS scores are significantly lower in those donors whose recipients suffered complications after receiving an LDLT, although other reports have found contradictory findings.(28) Advanced donor age is significantly correlated with a higher mental QOL when compared to younger donors in one report. Past or present psychiatric history, holding a graduate degree, and concerns about the donor's own well being prior to LDLT donation all negatively impact donor mental QOL scores in the large Dubay cross-sectional study. Furthermore, those donors who have a psychiatric diagnosis at the time of donation and excessive concerns over their own health have significantly worse QOL when compared to population norms.(26)

While many LDLT donor QOL papers have used scales like the SF-36, which are relatively general in focus, several researchers have augmented their studies with more targeted symptom scales, which have provided useful information on donor well-being. Specifically, the most prominent symptoms within one month of donation in the Verbesey cohort included bloating and loss of muscle tone.(14) In the 6 to 12 month period after donation, the most common complaints are a change in body image, increased tiredness, and fatigue.(13, 21) Across various studies, 0 to 15 percent of donors experienced sexual dysfunction after donation.(13, 19, 23, 29, 30) Three months after donation, approximately 33 percent of donors are able to work and, by 12 months, 91 percent of donors are able to return to full time employment.(13, 19, 29) With respect to financial burden, the mean out-of-pocket financial cost for LDLT donors is estimated between $3,660 and $5,305 USD.(14, 19)

Discussion

This comprehensive review of the literature suggests that, overall, LDLT donors tolerate donation well and perceive near normal functioning soon after donation. While clinical morbidity associated with LDLT donation has been studied in multi-center settings, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study (A2ALL)[30], the effect of LDLT donation on the donor's QOL, has only been assessed in a cursory manner and exclusively at single centers. Based on our review of the 19 available studies with QOL data regarding LDLT donors, we make four general observations. Prior to donation, donors have a QOL that is equal to or better than comparison groups drawn from the general population. In the year after donation, physical well-being decreases immediately following donation, but returns to levels comparable to normative samples within one year, while mental well-being appears to remain relatively stable throughout the transplantation process.(13, 14) That said, while the overall mental QOL (MCS) is relatively preserved in donors throughout the pre- and post-donation period, it is diminished in those donors who donate in urgent situations, such as ALF, and in those donating for LDLT recipients with HCC.(12) Finally, cross-sectional data suggest that donor QOL after donation is diminished if donors have psychiatric comorbidities, if they have a higher level of education, and if they express worry about their own well-being prior to donation.(26)

While there is an emerging picture of the QOL impact of living liver donation, the literature on LDLT donors' well-being remains limited. Many of studies reviewed had considerable methodological limitations. Cross-sectional studies typically compared donor QOL scores to those from the general population or from selected cohorts (e.g. medical students).(31) Arguably, these are sub-optimal control groups given that LDLT donors often have higher than normative QOL prior to donation.(32) A donor with QOL scores equivalent to the normative population after LDLT donation may actually be experiencing a relative decline in QOL compared to their pre-LDLT levels.

This dilemma leads to a broader consideration of the best control group against which to gauge living liver donor QOL. It turns out that there are a variety of potential populations to consider for such a comparison, including donor acquaintances, kidney donors, blood donors, healthy adults, potential but unselected liver donor, or the donors themselves prior to transplant. While each of these suggestions has associated benefits and costs, we would be interested in seeing future investigation make use of the `acquaintance control'. In this approach, researchers would enroll acquaintances of the donors, identified by the donors themselves. While resource intensive, this approach has been used with success in Hodgkin's disease,(33–36) in ovarian cancer,(37) and in bone marrow transplant(38, 39) studies. Acquaintance controls tend to be similar to donors with respect to their socioeconomic status, age, education, and race – the key difference being the living donor liver surgery itself. Furthermore, the connection to an actual donor may make controls more willing and motivated to contribute to the process by partaking in research efforts.

Of the included studies, 68 percent were cross-sectional and only 32 percent had a prospective design. The available prospective studies have only followed donors for a median of 9 months with a maximum of 12 months. As such, there is a general paucity of knowledge on the predictors of QOL in donors and on their longer-term health status. The existing literature is also hampered by low enrollment -- eleven of the nineteen studies (58%) enrolled less than thirty donors. Six of these eleven studies found no difference between donors and controls; however, given the low sample size, it remains unclear whether this is a statistical artifact (type II error) or a true similarity. The low number of donors also precludes any meaningful subgroup analysis, which is of particular importance in those few donors who do experience a reduced QOL after LDLT donation. In addition, not all donors approached for participation in the cross-sectional studies actually respond. In five of the studies (12, 16, 23, 26, 28), response rates ranged from 59%–83%. This is important because there is evidence of decreased response rate in those donors who experienced recipient mortality. For example, Miyagi et al. reported a 40% response rate for donors whose recipient had died.(25, 27) For this reason, care should be taken to understand what factors differentiate responders vs. non-responders with respect to post-donation quality of life. A final methodological concern of the existing literature is a lack of QOL instruments available to address the specific concerns of donors. The generic QOL instruments that have been primarily used, such as the SF-36 and SF-12, may not adequately assess aspects of QOL most relevant to LDLT donation. Studies that have assessed psychological outcomes in donors report that 4–26% experience some level of psychological morbidity that may not fully be captured by these generic QOL instruments.(40–42) Additional work is necessary to develop assessments that query the most germane aspects of donors' sense of well being and QOL. The development of a LDLT donor-specific instrument may improve our assessment of donor well-being and may ultimately aid in the development of pre-donation risk stratification. Moreover, such a tool might help to predict a priori, which of those 7 to 20 percent living liver donors will go on to experience reduced QOL.(18, 20, 23) While the initial picture is promising, there is clearly important work to be done to improve our understanding of the QOL impact of LDLT.

Along these lines, the NIH funded A2ALL Cohort Study [30] has outlined the assessment of QOL as one of its primary objectives. Data from the multi-center, prospective cohort of donors has the potential to elucidate long-term QOL after LDLT donation.(19, 43). While A2ALL presents an important opportunity to better understand long-term LDLT outcomes, there are many centers worldwide that perform LDLT that have not reported on donor QOL. In some cases, centers may not routinely measure QOL, or if they do, they may be reluctant publicize sub-optimal outcomes. As with other outcomes studies, the potential for publication bias is important to consider. It should also be appreciated that there may be international differences on such outcomes, due to differences in donor selection, healthcare delivery, and societal norms.

Potential donor issues to consider going forward include body image and the impact of the abdominal incision, financial burden, sexual dysfunction, the donor-recipient relationship, and the issue of coercion in urgent LDLT. In their qualitative study of donors, Papachristou et al. (44) suggest multiple additional foci including, pre-operative emotional coping, donor autonomy, preparation and anticipation of the post-operative course and the impact of post-operative complications on the donor's life. Adequately powered, multi-center, long-term studies are necessary to better evaluate these and other QOL issues in donors. Furthermore, sensitive living donor-specific QOL instruments must be developed for accurate assessment of donor QOL. The informed assessment of QOL holds the promise for more comprehensive informed consent for potential donors and focused interventions to improve the QOL in donors after donation.

QOL and a general sense of well-being is an important outcome after any medical intervention, but even more important for LDLT donors, given the altruistic premise of the procedure. Providing donors with adequate risk information prior to LDLT donation and use of evidenced-based methods to ensure the highest possible post-LDLT QOL should be prioritized as medical and surgical advances in LDLT are developed.

Figure 1.

Search Strategy Using MEDLINE/Cochrane (LT: Liver Transplantation)

Acknowledgments

Dr. Parikh's preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by grant 5T32DK077662-04 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health. Dr. Butt's preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by grant KL2RR0254740 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

List of abbreviations

- LDLT

Living donor liver transplantation

- QOL

Quality of life

- ESLD

End stage liver disease

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- SF-36

Short-form 36

- LDQOL

Liver Disease Quality of Life survey

- PCS

Physical Composite Score

- MCS

Mental Composite Score

- WHOQOL-BREF

World Health Organization Quality of Life -BREF

- ACSA

Anamnestic Comparative Self-Assessment Scale

- ALF

Acute liver failure

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- A2ALL

Adult-to-adult Living Liver Transplant study

References

- 1.Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients: Transplant Data 1997–2006 Health Resources and Services Administration. Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation; Rockville, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trotter JF, Wachs M, Everson GT, Kam I. Adult-to-adult transplantation of the right hepatic lobe from a living donor. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(14):1074–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra011629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghobrial RM, Freise CE, Trotter JF, Tong L, Ojo AO, Fair JH, et al. Donor morbidity after living donation for liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(2):468–76. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marsh JW, Gray E, Ness R, Starzl TE. Complications of right lobe living donor liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2009;51(4):715–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surman OS. The ethics of partial-liver donation. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(14):1038. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200204043461402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Measuring Healthy Days. CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, Georgia: Nov, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ware JE, Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30(6):473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, O'Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. [see comment][comment]. BMJ. 1992;305(6846):160–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gotardo DR, Strauss E, Teixeira MC, Machado MC. Liver transplantation and quality of life: relevance of a specific liver disease questionnaire. Liver Int. 2008;28(1):99–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jay CL, Butt Z, Ladner DP, Skaro AI, Abecassis MM. A review of quality of life instruments used in liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2009;51(5):949–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.SF-36 PCS, MCS and NBS Calculator. cited 2009 May 20. Available from: http://www.sf-36.org/nbscalc/index.shtml.

- 12.Erim Y, Beckmann M, Kroencke S, Valentin-Gamazo C, Malago M, Broering D, et al. Psychological strain in urgent indications for living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2007;13(6):886–95. doi: 10.1002/lt.21168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan SC, Liu CL, Lo CM, Lam BK, Lee EW, Fan ST. Donor quality of life before and after adult-to-adult right liver live donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(10):1529–36. doi: 10.1002/lt.20897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verbesey JE, Simpson MA, Pomposelli JJ, Richman E, Bracken AM, Garrigan K, et al. Living donor adult liver transplantation: a longitudinal study of the donor's quality of life. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(11):2770–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basaran O, Karakayali H, Emiroglu R, Tezel E, Moray G, Haberal M. Donor safety and quality of life after left hepatic lobe donation in living-donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35(7):2768–9. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.09.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feltrin A, Pegoraro R, Rago C, Benciolini P, Pasquato S, Frasson P, et al. Experience of donation and quality of life in living kidney and liver donors. Transpl Int. 2008;21(5):466–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karliova M, Malago M, Valentin-Gamazo C, Reimer J, Treichel U, Franke GH, et al. Living-related liver transplantation from the view of the donor: a 1-year follow-up survey. Transplantation. 2002;73(11):1799–804. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200206150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parolin MB, Lazzaretti CT, Lima JH, Freitas AC, Matias JE, Coelho JC. Donor quality of life after living donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2004;36(4):912–3. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.03.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trotter JF, Talamantes M, McClure M, Wachs M, Bak T, Trouillot T, et al. Right hepatic lobe donation for living donor liver transplantation: impact on donor quality of life. Liver Transpl. 2001;7(6):485–93. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.24646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walter M, Dammann G, Papachristou C, Pascher A, Neuhaus P, Danzer G, et al. Quality of life of living donors before and after living donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35(8):2961–3. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walter M, Bronner E, Pascher A, Steinmuller T, Neuhaus P, Klapp BF, et al. Psychosocial outcome of living donors after living donor liver transplantation: a pilot study. Clin Transplant. 2002;16(5):339–44. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2002.02002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kusakabe T, Irie S, Ito N, Kazuma K. Feelings of living donors about adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2008;31(4):263–72. doi: 10.1097/01.SGA.0000334032.48629.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim-Schluger L, Florman SS, Schiano T, O'Rourke M, Gagliardi R, Drooker M, et al. Quality of life after lobectomy for adult liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73(10):1593–7. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200205270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu HT, Hwang SL, Lee PH, Chen SC. Impact of liver donation on quality of life and physical and psychological distress. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(7):2102–5. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyagi S, Kawagishi N, Fujimori K, Sekiguchi S, Fukumori T, Akamatsu Y, et al. Risks of donation and quality of donors' life after living donor liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2005;18(1):47–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2004.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DuBay DA, Holtzman S, Adcock L, Abbey S, Greenwood S, Macleod C, et al. Adult right-lobe living liver donors: quality of life, attitudes and predictors of donor outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(5):1169–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Humar A, Carolan E, Ibrahim H, Horn K, Larson E, Glessing B, et al. A comparison of surgical outcomes and quality of life surveys in right lobe vs. left lateral segment liver donors. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(4 Pt 1):805–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erim Y, Beckmann M, Valentin-Gamazo C, Malago M, Frilling A, Schlaak JF, et al. Quality of life and psychiatric complications after adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(12):1782–90. doi: 10.1002/lt.20907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beavers KL, Sandler RS, Fair JH, Johnson MW, Shrestha R. The living donor experience: donor health assessment and outcomes after living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2001;7(11):943–7. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.28443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sevmis S, Diken T, Boyvat F, Torgay A, Haberal M. Right hepatic lobe donation: impact on donor quality of life. Transplant Proc. 2007;39(4):826–8. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pascher A, Sauer IM, Walter M, Lopez-Haeninnen E, Theruvath T, Spinelli A, et al. Donor evaluation, donor risks, donor outcome, and donor quality of life in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8(9):829–37. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.34896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walter M, Bronner E, Steinmuller T, Klapp BF, Danzer G. Psychosocial data of potential living donors before living donor liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2002;16(1):55–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2002.00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cella DF, Tross S. Psychological adjustment to survival from Hodgkin's disease. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54(5):616–22. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kornblith AB, Anderson J, Cella DF, Tross S, Zuckerman E, Cherin E, et al. Quality of life assessment of Hodgkin's disease survivors: a model for cooperative clinical trials. Oncology (Williston Park) 1990;4(5):93–101. discussion 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kornblith AB, Anderson J, Cella DF, Tross S, Zuckerman E, Cherin E, et al. Hodgkin disease survivors at increased risk for problems in psychosocial adaptation. The Cancer and Leukemia Group B. Cancer. 1992;70(8):2214–24. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921015)70:8<2214::aid-cncr2820700833>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kornblith AB, Anderson J, Cella DF, Tross S, Zuckerman E, Cherin E, et al. Comparison of psychosocial adaptation and sexual function of survivors of advanced Hodgkin disease treated by MOPP, ABVD, or MOPP alternating with ABVD. Cancer. 1992;70(10):2508–16. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921115)70:10<2508::aid-cncr2820701020>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Monahan PO, Champion VL, Zhao Q, Miller AM, Gershenson D, Williams SD, et al. Case-control comparison of quality of life in long-term ovarian germ cell tumor survivors: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2008;26(3):19–42. doi: 10.1080/07347330802115715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andrykowski MA, Bishop MM, Hahn EA, Cella DF, Beaumont JL, Brady MJ, et al. Long-term health-related quality of life, growth, and spiritual well-being after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(3):599–608. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bishop MM, Beaumont JL, Hahn EA, Cella D, Andrykowski MA, Brady MJ, et al. Late effects of cancer and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation on spouses or partners compared with survivors and survivor-matched controls. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1403–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walter M, Pascher A, Jonas S, Danzer G, Frommer J, Neuhaus P, et al. Living donor liver transplantation from the perspective of the donor: results of a psychosomatic investigation. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2005;51(4):331–45. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2005.51.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Erim Y, Senf W, Heitfeld M. Psychosocial impact of living donation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35(3):911–2. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trotter JF, Hill-Callahan MM, Gillespie BW, Nielsen CA, Saab S, Shrestha R, et al. Severe psychiatric problems in right hepatic lobe donors for living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;83(11):1506–8. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000263343.21714.3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghobrial RM, Busuttil RW. Challenges of adult living-donor liver transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13(2):139–45. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-1020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papachristou C, Walter M, Frommer J, Klapp BF. A model of risk and protective factors influencing the postoperative course of living liver donors. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(5):1682–6. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.02.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]