A 13 year old boy with Crohn's disease in remission presented with a 10 day history of head and back pain. He also mentioned intermittent blurring of vision and had developed a new squint four days before admission. He had a history of hay fever and was being treated with fluticasone propionate aqueous nasal spray 50 μg to each nostril once a day (Glaxo Wellcome). This had been taken infrequently until five days before admission when our colleagues from the ear, nose, and throat department reviewed him and advised regular treatment.

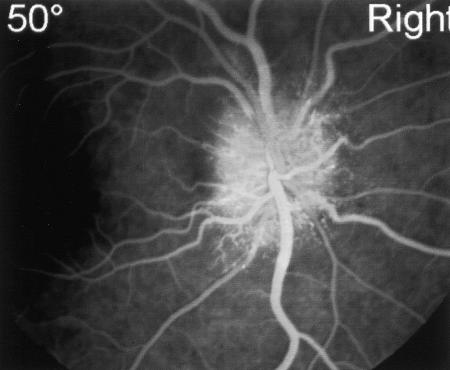

On examination his optic discs were swollen bilaterally and he had a right sixth nerve palsy. Investigations showed no evidence of intercurrent infection. Urea and electrolytes, liver function, and concentrations of calcium, phosphate, and magnesium were all within normal limits. Fluorescein angiography showed leakage of dye from the optic discs, confirming mild bilateral papilloedema (figure). An unenhanced computed tomogram gave normal results. Cerebrospinal fluid was clear and colourless with no cells, and the protein concentration was 0.1 g/l and glucose concentration 4.3 mmol/l (blood glucose 5.2 mmol/l). The opening pressure of the cerebrospinal fluid was not measured. Magnetic resonance imaging excluded cavernous sinus thrombosis.

The fluticasone propionate was stopped, and over the next few weeks his headaches and back pain disappeared. His sixth nerve palsy resolved, and his disc margins cleared. On review five months later his optic discs had returned to normal and he had remained asymptomatic.

We propose that nasal fluticasone propionate caused this child's benign intracranial hypertension because of the temporal relation between symptoms to its regular administration. After lumbar puncture and the cessation of the drug his symptoms resolved over a few weeks and the papilloedema resolved over several months.

The occurrence of benign intracranial hypertension is well documented with corticosteroids when given systemically1–3 or topically,1,4 together with their withdrawal.5 We reported this adverse reaction to the Committee on Safety of Medicines. The Medicines Control Agency and the manufacturers have confirmed that there have been no previous reports of benign intracranial hypertension with nasal fluticasone proprionate. Benign intracranial hypertension should be considered as a potential cause of headache in children taking nasal steroids.

Figure.

Disc swelling, vascular nipping, and vessel leakage shown by fluorescein angiography

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Grant DN. Benign intracranial hypertension: a review of 79 cases in infancy and childhood. Arch Dis Child. 1971;46:651–655. doi: 10.1136/adc.46.249.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vyas CK, Talwar KK, Bhatnagar V, Sharma BK. Steroid-induced benign intracranial hypertension. Postgrad Med J. 1981;57:181–182. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.57.665.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newton M, Cooper BT. Benign intracranial hypertension during prednisolone treatment for inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1994;35:423–425. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hosking GP, Elliston H. Benign intracranial hypertension in a child with excema treated with topical steroids. BMJ. 1978;1:550–551. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6112.550-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neville BGR, Wilson J. Benign intracranial hypertension following corticosteroid withdrawal in childhood. BMJ. 1970;3:554–556. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5722.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]