Abstract

Glucose is considered essential for erythrocytic stages of the malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. Importance of sugar and its permease for hepatic and sexual stages of Plasmodium, however, remains elusive. Moreover, increasing global resistance to current antimalarials necessitates the search for novel drugs. Here, we reveal that hexose transporter 1 (HT1) of Plasmodium berghei can transport glucose (Km∼87 μM), mannose (Ki∼93 μM), fructose (Ki∼0.54 mM), and galactose (Ki∼5 mM) in Leishmania mexicana mutant and Xenopus laevis; and, therefore, is functionally equivalent to HT1 of P. falciparum (Glc, Km∼175 μM; Man, Ki∼276 μM; Fru, Ki∼1.25 mM; Gal, Ki∼5.86mM). Notably, a glucose analog, C3361, attenuated hepatic (IC50∼15 μM) and ookinete development of P. berghei. The PbHT1 could be ablated during intraerythrocytic stages only by concurrent complementation with PbHT1-HA or PfHT1. Together; these results signify that PbHT1 and glucose are required for the entire life cycle of P. berghei. Accordingly, PbHT1 is expressed in the plasma membrane during all parasite stages. To permit a high-throughput screening of PfHT1 inhibitors and their subsequent in vivo assessment, we have generated Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant expressing codon-optimized PfHT1, and a PfHT1-dependent Δpbht1 parasite strain. This work provides a platform to facilitate the development of drugs against malaria, and it suggests a disease-control aspect by reducing parasite transmission.—Blume, M., Hliscs, M., Rodriguez-Contreras, D., Sanchez, M., Landfear, S., Lucius, R., Matuschewski, K., Gupta, N. A constitutive pan-hexose permease for the Plasmodium life cycle and transgenic models for screening of antimalarial sugar analogs.

Keywords: sugar transport, metabolic drug target, high-throughput screening

Apicomplexan parasites such as Plasmodium, Toxoplasma, and Eimeria are obligate intracellular pathogens of diverse ecological niches, which inflict a major burden on human and animal health care. Infections with human Plasmodium species cause malaria, with an estimated 106 deaths/yr, and impose an immense socioeconomic burden (1). Plasmodium depends on a continuous supply of host-derived sugars for its intraerythrocytic replication (2, 3), for the synthesis of fatty acids and amino sugars, and for the GPI anchors of its major surface proteins (4–6). Glucose is, therefore, an essential nutrient for in vitro blood cultures of Plasmodium species (7). The parasite replicates inside a parasitophorous vacuole, whose membrane is permeable to sugars (8). However, the transport of sugars across the parasite plasma membrane requires a facilitative permease. In this regard, hexose transporter 1 of Plasmodium falciparum (PfHT1) is known to transport glucose and fructose (3), and is essential for blood-stage parasites, in vitro (9). Although PfHT1 is considered an excellent drug target for intraerythrocytic stages, the significance of glucose and its transporter for liver and sexual stages of Plasmodium remains unresolved. In addition, emerging global resistance against available antimalarials has necessitated development of in vitro and in vivo models for a large-scale screening and pharmacological assessment of novel candidate drugs.

Glucose catabolism by Plasmodium and Toxoplasma is mostly restricted to glycolysis and does not yield any significant CO2 by consumption of pyruvate in the mitochondria; instead, it is reduced to lactate (10). Also, oxidative phosphorylation in Plasmodium mitochondria is down-regulated in the asexual stages, and the ATP in parasite is produced primarily via glycolysis (11, 12). Surprisingly, our recent research revealed the nonessential nature of host-derived glucose and its transporter in Toxoplasma gondii (13). The unanticipated dispensability of glucose is due to a crucial contribution of glutaminolysis and gluconeogenesis to the carbon metabolism of T. gondii. In Plasmodium, glycolysis- and glutaminolysis-derived carbon is used for different purposes (5), and it is known from wild isolates that the parasite can adapt to distinct physiological states (14). It remains to be determined, however, whether glycolysis is critical for Plasmodium in all life-cycle stages or can be substituted by ancillary pathways.

To address the aforementioned questions, as well as to advance the potential of hexose transport as a target for antimalarial drug development, we employed experimental genetics in the rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium berghei. This report shows that hexose transporter 1 of P. berghei (PbHT1) is equivalent to PfHT1 and transports 4 physiological hexoses. PbHT1 is a surface-localized constitutive permease and is essential for hepatic, erythrocytic, and ookinete development of P. berghei. Transgenic expression of PfHT1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and in P. berghei provides a versatile platform for high-throughput screening of selective PfHT1 inhibitors and in vivo assessment of their antimalarial efficacy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Biological reagents

Compound 3361 (C3361) was generously provided by David H. Peyton and Cheryl A. Hodson (Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA). The S. cerevisiae EBY4000 mutant was kindly provided by Eckhard Boles (University of Frankfurt, Main, Germany). Anti-PbACP and anti-PbHSP70 antibodies were donated by Johannes Friesen (Max-Planck Institute for Infection Biology, Berlin, Germany) and Moriya Tsuji (New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY, USA). Radioisotopes were procured from the American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA) and Moravek Biochemicals and Radiochemicals (Brea, CA, USA). Animal procedures were performed according to the German Animal Protection Laws, as dictated by the Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales (Berlin, Germany). NMRI mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratory (Sulzfeld, Germany). All assays were performed 3 independent times unless specified otherwise.

Functional expression in Leishmania and Xenopus

PbHT1, PfHT1, and TgGT1 were amplified from their respective P. berghei ANKA gDNA, P. falciparum 3D7 gDNA, or T. gondii RH tachyzoite cDNA using the ORF-specific primers (Table 1) and Pfu-Ultra Fusion II High-Fidelity Polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). The ORFs were cloned into pX63NeoRI and/or pL2–5 (harboring β-globulin 5′ and 3′ UTR of Xenopus) for expression in Leishmania mexicana and Xenopus laevis, respectively. For Xenopus, constructs were transcribed into cRNA using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Ultra Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Stage V–VI oocytes were injected with 27.6 nl of cRNA (∼14 ng) or water and then incubated for 4 d at 16°C in ND96 buffer. Uptake of radiolabeled sugars ([14C]d-glucose, 25 Ci/mmol; [14C]d-fructose, 300 mCi/mmol; [14C]d-galactose, 52 mCi/mmol; and [14C]d-manose, 50 mCi/mmol) was assayed by incubating oocytes with radiolabeled hexoses at room temperature, followed by 3 washes in ND96 buffer, and scintillation counting, as described before (15). For expression in L. mexicana, the Δlmgt promastigotes were transformed with ∼5 μg of linear pX63NeoRI constructs in 0.2-cm electrode-gap cuvettes (0.45 kV, 500 μF; Gene Pulser II, Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA) as described previously (16), and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (pH 7.2) with 10% FBS and the drug G418 (100 μg/ml). The parasites were washed twice in PBS (pH 7.4) and resuspended in PBS. Time courses were performed at 25°C with 100 μM of [14C]d-glucose, [14C]d-mannose, [14C]d-fructose, and [14C]d-galactose by a 2-phase rapid centrifugation method (17). For substrate saturation curves, incubations with [3H]d-glucose were performed for 30 s (n=4), and for the Ki (n=2), inhibition curves were generated with 100 μM of [3H]d-glucose as a ligand and 0–50 mM of sugars or 0–0.25 mM of C3361 as inhibitors. The Km values were determined by fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation. The Ki values were calculated from nonlinear regression formulations and the Cheng and Prusoff approximation of the data employing the Km value of 87.2 μM for PbHT1 or 175.2 μM for PfHT1 (Prism v4; GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical analysis was carried out using a 2-tailed unpaired t test.

Table 1.

Cloning primers used in this study

| Primer and restriction site | Primer sequence | Cloning vector and research objective |

|---|---|---|

| Expression in Leishmania | ||

| PbHT1-F, EcoRV | CTCATCGATATCATGGATATATTATCAAGAGGGGGGACTC | pX63NeoRI, functional expression in L. mexicana |

| PbHT1-R, EcoRV | CTCATCGATATCTTAAACTCTTGATTTGCTTATATGTTTTTGTCTTTCTTC | |

| PfHT1-F, EcoRV | CTCATCGATATCATGACGAAAAGTTCGAAAGATATATGTAGTGAG | pX63NeoRI, functional expression in L. mexicana |

| PfHT1-R, EcoRV | CTCATCGATATCTCATACAACCGACTTGGTCATAT | |

| Expression in Xenopus | ||

| PbHT1-F, BglII | CTCATCAGATCTATGGATATATTATCAAGAGGGGGGACTC | pL2–5, functional expression in X. laevis oocyte |

| PbHT1-R, PacI | CTCATCTTAATTAATTAAACTCTTGATTTGCTTATATGTTTTTGTCTTTCTTC | |

| PfHT1-F, BglII | CTCATCAGATCTATGACGAAAAGTTCGAAAGATATATGTAGTGAG | pL2–5, functional expression in X. laevis oocyte |

| PfHT1-R, PacI | CTCATCTTAATTAATCATACAACCGACTTGGTCATAT | |

| Expression in yeast | ||

| ScHXT9-F, SpeI | CTCATCACTAGTATGTCCGGTGTTAATAATACATCC | p426-Hxt7-his, functional expression in S. cerevisiae |

| ScHXT9-R, SpeI) | CTCATCACTAGTTTAGCTGGAAAAGAACCTCTTGT | |

| ScHXT9-F, NotI) | CTCATCGCGGCCGCATGTCCGGTGTTAATAATACATCC | pESC-Ura, functional expression in S. cerevisiae |

| ScHXT9-R, NotI | CTCATCGCGGCCGCTTAGCTGGAAAAGAACCTCTTGT | |

| ScHXT9-GM55-F, EcoRI | CTCGAATTCATGTCCGGTGTTAATAATACATCCG | Construction of GM55-PfHT1-Syn in pESC-Ura |

| ScHXT9-GM55-R, NotI | CTCGCGGCCGCAGAGGGGTTTTTGAGGTAAGTCAA | |

| ScITR1-GM80-F, EcoRI | CTCGAATTCATGGGAATACACATACCATATCTCAC | Construction of GM80-PfHT1-Syn in pESC-Ura |

| ScITR1-GM80-R, NotI | CTCGCGGCCGCATTGGTTAAAAGTGATCATGACCG | |

| PfHT1-Syn-F, SpeI | CTCATCACTAGTATGACTAAGTCTTCAAAGGATATCTGT | p426-Hxt7-his, functional expression in S. cerevisiae |

| PfHT1-Syn-R, SpeI | CTCATCACTAGTTTAAACAACGGACTTTGTCATATG | |

| PfHT1-GM55-F, SpeI | CTCATCACTAGTATGTCCGGTGTTAATAATACATCC | p426-Hxt7-his, functional expression in S. cerevisiae |

| PfHT1-Syn-R, SpeI | CTCATCACTAGTTTAAACAACGGACTTTGTCATATG | |

| PfHT1-GM55-F, SpeI | CTCATCACTAGTATGTCCGGTGTTAATAATACATCC | p426-Hxt7-his, functional expression in S. cerevisiae |

| PfHT1-Syn-R, SpeI | CTCATCACTAGTTTAAACAACGGACTTTGTCATATG | |

| PbHT1 knockout | ||

| PbHT1–5'UTR-F, NotI | CTCATCGCGGCCGCGCAAAACTAAATCGGATTAATGCCGA | pb3D+, for homologous recombination at 5′ end |

| PbHT1–5'UTR-R, BamHI | CTCATCGGATCCACGCAATATATTCATTTTTTCGTATTAATACACATATATTTCTTG | |

| PbHT1–3'UTR-F, ApaI | CTCATCGGGCCCCATACAAGAACACACCGGCAAT | pb3D+, for homologous recombination at 3′ end |

| PbHT1–3'UTR-R, KpnI | CTCATCGGTACCCTTATGTTAAACAATTATCCTTTCCAATTATCACAC | |

| PbHT1–5'UTR-F, NotI | CTCATCGCGGCCGCGCAAAACTAAATCGGATTAATGCCGA | pb3D+, PbHT1-HA-based PbHT1 gene deletion |

| PbHT1-HA-R, BamHI | CTCATCGGATCCTTAAGCGTAATCTGGAACATCGTATGGGTAAACTCTTGATTTGCTTATATGTTTTTGTCTTTCTTC | |

| PbHT1–5'Scr-F | GCCGTTGGAGAAAATGCAATTAAG | pDrive, T/A-cloning for testing 5′ recombination |

| PbHT1–5'Scr-R | TCCAGATGGAGATGGCTGTCTAG | |

| PbHT1–3'Scr-F PbHT1–3'Scr-R |

CAGACACACCGGTTTATGCATGATTCGCTAATATCTATGTCAAACCTCCTAGTAG | pDrive, T/A-cloning for testing 3′ recombination |

| HA-R | AGCGTAATCTGGAACATCGTATGGGTA | Test of PbHT1-HA transcript |

| PbHT1-clone-F | GAAGAAAGACAAAAACATATAAGCAAATCAAGAGTTTAA | Clonality testing of Δpbht1-PbHT1-HA |

| PfHT1-F, BamHI | CTCATCGGATCCAAAATGACGAAAAGTTCGAAAGATATATGTAGTGAG | pb3D+, PfHT1-based PbHT1 gene deletion |

| PfHT1-R, BamHI | CTCATCGGATCCTCATACAACCGACTTGGTCATATGC |

Restriction sites are underscored in primer sequences.

Culture and manipulation of P. berghei and T. gondii

In vitro cultures of ookinete were performed in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS, 0.85 mg/ml NaHCO3, 50 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin, and 50 μM xanthurenic acid. The complete medium was adjusted to pH 8 and diluted with fresh P. berghei-infected blood (1:10). Samples were incubated for 18 to 20 h at 21°C for ookinete formation. Mature ookinetes were purified using magnetic beads conjugated with anti-p28 monoclonal antibodies (18). Fresh P. berghei sporozoites were used to infect Huh7 liver cells. T. gondii tachyzoites were cultured in HFF cells, as described previously (19). All host cells were cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin (37°C, 10% CO2). Infection of Huh7 cells with P. berghei or of HFF cells with T. gondii was performed in presence of C3361 or DMSO, as indicated in the respective figure legends. The 5′ and 3′ UTRs of PbHT1 and the ORFs of PbHT1 and PfHT1 were amplified using the primers indicated in Table 1, and cloned into pb3D+-knockout vector containing the T. gondii dhfr/ts selection marker. The 5′ and 3′ UTRs used in this study represent the flanking regions upstream and downstream of the initiating and stop codons. KpnI/NotI-linearized constructs (2–5 μg)were transfected into gradient-purified schizonts of wild-type or GFP-P. berghei ANKA using the Amaxa Nucleofector device (Lonza AG, Basel, Switzerland; ref. 20).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Mosquitoes were fed on anesthetized parasite-infected NMRI mice. Sporozoites and oocysts were isolated into ice-cold PBS/4% BSA on d 17 postfeeding. The free parasites were fixed on poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA); parasite-infected erythrocytes were fixed with 4% PFA plus 0.0025% glutaraldehyde, and Huh7 cells were fixed with ice-cold methanol. All samples except oocysts were permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100, blocked in 0.2% Triton X-100 plus 2% BSA, and stained by mouse α-HSP70 (21) or rabbit α-HA antibodies. Oocysts were treated with 1% Triton X-100. Alexa488/594 α-rabbit and α-mouse antibodies were used to visualize samples.

S. cerevisiae complementation assays

The EBY4000 yeast mutant cells were grown in 2% yeast extract, 1% peptone, and 2% maltose (YPM) at 30°C. Synthetic defined uracil-free medium [SD(−Ura); 0.67% yeast nitrogen base with ammonium sulfate and without amino acids; Difco, Surrey, UK] supplemented with amino acids and 2% maltose was used to analyze the S. cerevisiae EBY4000 mutant (Δhxt1–17 Δgal2 Δstl1 Δagt1 Δmph2 Δmph3; ref. 22) using standard yeast protocol. The mutant was transformed with p426-hxt7-his vector harboring indicated ORFs under the HXT7 promoter (primers in Table 1). Yeast transfectants were selected for single colonies on SD(−Ura) with 2% maltose. Transport assays were performed with clonal transformants on SD(−Ura) supplemented with glucose or mannose.

RESULTS

PbHT1 and PfHT1 are functionally analogous pan-hexose permeases

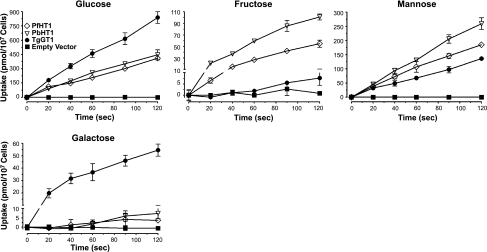

To examine the substrate specificity and transport kinetics of PbHT1, we first employed the L. mexicana null mutant Δlmgt, which is entirely deficient in hexose uptake (16), and provides the ideal background for analysis of sugar permeases. TgGT1, which can uptake all four physiological hexoses (13), and PfHT1, which transports glucose in the L. mexicana model (23), were included alongside to compare with PbHT1. Interestingly, PbHT1 and PfHT1 restored the ability of Δlmgt cells to import glucose, mannose, fructose, and galactose in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1). In contrast, the mutant harboring the empty vector (pX63NeoRI) did not transport any of these substrates. The uptake was largely linear for all sugars, and the extent of labeling indicated glucose and mannose as preferred ligands for both permeases. Fructose and galactose were transported with medium to low affinity, respectively (see below; Fig. 2). In accord with the Leishmania mutant, expression of PbHT1 and PfHT1 in Xenopus oocytes also facilitated the transport of all four hexoses in a time-dependent manner, whereas equivalent negative control cells, water-injected oocytes, displayed negligible import (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Uptake was largely linear for mannose, fructose, and galactose over time, but not for glucose, for which it reached equilibrium at 60 min. As anticipated, glucose and mannose were imported with higher efficiency than fructose and galactose.

Figure 1.

PbHT1 and PfHT1 proteins can restore the transport of glucose, mannose, fructose and galactose in the L. mexicana null mutant. Uptake of [14C]d-glucose, [14C]d-mannose, [14C]d-fructose, and [14C]d-galactose in Δlmgt promastigotes expressing PbHT1, PfHT1, or TgGT1 was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Vector-transfected cells were used as a negative control. Values are expressed as means ± sd.

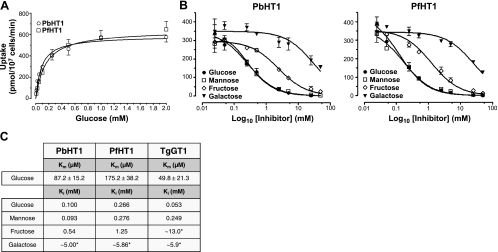

Figure 2.

Glucose and mannose exhibit high affinity toward PbHT1 and PfHT1, whereas fructose and galactose are low-affinity ligands. A) Substrate saturation curves of stable transgenic PbHT1- and PfHT1-expressing L. mexicana parasites. Δlmgt promastigotes (2×107) expressing PbHT1 or PfHT1 were incubated with 0–2 mM [3H]d-glucose for 30 s at 25°C. B) Inhibition of PbHT1- or PfHT1-mediated uptake of [3H]d-glucose (100 μM) with indicated nonlabeled hexoses as inhibitors. C) Km and Ki values for glucose, mannose, fructose, and galactose for PbHT1 and PfHT1. Kinetic data of TgGT1 (present study and ref. 13) are included for comparison. Asterisks indicate Ki values that are approximate due to incomplete (∼50–60%) inhibition. Values are expressed as means ± se.

We next determined the Km values of Plasmodium transporters for glucose in the Leishmania null mutant. For saturation curves with glucose, assays were performed for 30 s, after pilot experiments indicated that PbHT1- and PfHT1-mediated uptake was linear for this period over the range of tested amounts. The assay minimized the prospect of sugar metabolism and sequestration subsequent to their transport, and allowed us to measure initial rates. PbHT1 and PfHT1 displayed apparent Km of 87 and 175 μM, respectively (Fig. 2A, C), compared to the Km of ∼50 μM for TgGT1 (13). The Km of PfHT1 for glucose in Leishmania mutant is similar to other studies in Leishmania (∼300 μM; ref. 23) and Xenopus (∼480 μM; ref. 24).

In further experiments, we examined the concentration-dependent inhibition of glucose transport by the four hexoses (Fig. 2B, C). These assays revealed that glucose (PbHT1, Ki=100 μM; PfHT1, Ki=266 μM) and mannose (PbHT1, Ki=93 μM; PfHT1, Ki=276 μM) are high-affinity ligands for both proteins. PbHT1 and PfHT1 appear to transport these sugars with similar affinities. In accord with the time kinetics, Ki for PbHT1-expressing Leishmania parasites were consistently lower than for PfHT1-expressing cells. Ki for fructose and galactose were much higher, suggesting that both sugars are low-affinity ligands. Notably, however, Plasmodium transporters have higher affinity for fructose compared to TgGT1 (Figs. 1 and 2C). It might have some biological significance because fructose is known to effectively replace glucose in intraerythrocytic P. falciparum cultures (3). Taken together, our results demonstrate PbHT1 and PfHT1 to be functionally analogous pan-hexose permeases.

The functional similarity of PbHT1, PfHT1, and TgGT1 proteins is also supported by sequence alignments (Supplemental Fig. S1B). All permeases harbor a sugar transport domain (Pfam 00083) of the SLC2A family and 12 transmembrane regions. PbHT1 is 73, 35, and 38% identical to transporters from P. falciparum (PfHT1), T. gondii (TgGT1), and Eimeria tenella (EtHT1), respectively. PbHT1 and PfHT1 display a higher mutual resemblance in comparison to Toxoplasma and Eimeria permeases. Likewise, the coccidian proteins TgGT1 and EtHT1, with 52% identity, are more related to each other than to PbHT1 or PfHT1.

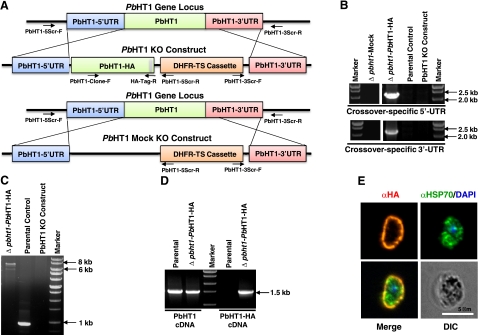

PbHT1 is indispensable for the intraerythrocytic stages of P. berghei

To examine whether PbHT1 indeed serves as the major sugar permease in P. berghei, we first searched for the expression of potential paralogs in the Plasmodium database (http://www.PlasmoDB.org). Notably, our in silico analysis did not identify any other permease with a sugar transport domain, 12 transmembrane helices, and typical membrane topology. A previous attempt to ablate PbHT1 failed, indicative of an essential function in mouse blood (9). Therefore, a complementation-based knockout approach was employed (Fig. 3) to credibly assess the in vivo significance of this hexose permease for the intraerythrocytic stages of Plasmodium. In addition to a conventional gene-knockout plasmid, we generated a targeting vector for simultaneous complementation of PbHT1 with its HA-fused isoform using the identical UTRs for the predicted recombination events (Fig. 3A). After transfection of blood-stage schizonts, pyrimethamine-resistant P. berghei parasites were selected and genotyped by PCR. In 3 independent assays, the presence of the DHFR-TS resistance cassette flanked by the 5′ and 3′ recombination-specific UTRs was detectable only in the parasite pools transfected with PbHT1-HA complementation construct (Δpbht1-PbHT1-HA) and not with the conventional knockout vector (Δpbht1-Mock; Fig. 3B). Absence of wild-type parasites in Δpbht1-PbHT1-HA lines was confirmed by PCR, which amplified an expected fragment of ∼7-kb from Δpbht1-PbHT1-HA gDNA (Fig. 3C), as opposed to ∼1-kb fragment from the parental gDNA, and no signal with the knockout vector. Sequencing of the recombination-specific products further confirmed the occurrence of crossover events at the predicted loci. PbHT1-HA mRNA was transcribed in Δpbht1-PbHT1-HA, but not in the parental strain (Fig. 3D). The encoded protein was expressed and localized to the parasite surface in blood-stage schizonts (Fig. 3E). The Δpbht1-PbHT1-HA parasite strain developed normally in Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes, and yielded sporozoites on d 17. Consistent with previous findings (9), these data show that PbHT1 encodes a surface-localized essential permease, and strengthen the notion that sugars are indispensable nutrients for the intraerythrocytic stages of P. berghei, in vivo.

Figure 3.

PbHT1 is an essential surface-localized permease, expressed in blood stages of P. berghei. A) Linearized PbHT1-HA-harboring knockout and mock constructs in alignment with the PbHT1 locus. Arrows depict crossover-specific primers (PbHT1–5Scr-F/R and PbHT1–3Scr-F/R) and clone-specific primers (PbHT1-Clone-F/PbHT1–3Scr-R) for PCR-based genotyping. B) Crossover-specific genomic PCR yields 5′/3′ bands only with PbHT1-HA-complemented KO parasite (Δpbht1-PbHT1-HA) but not with conventional KO construct-transfected (Δpbht1-Mock) or from parental strains. PCR with PbHT1 KO plasmid was included as an additional control. C) Genotyping by integration-specific PCR. Clone-specific primers (PbHT1-Clone-F and PbHT1–3Scr-R) amplify a gDNA fragment of 927 bp in the parental strains and of 6729 bp in Δpbht1-PbHT1-HA strains, and none with the plasmid control. D) RT-PCR using total RNA isolated from parental and Δpbht1-PbHT1-HA parasites. PbHT1 (PbHT1-F/PbHT1-R) and PbHT1-HA (PbHT1-F/HA-R)-specific primers produce amplicons of 1566 and 1602 bp, respectively. E) Immunofluorescence of Δpbht1-PbHT1-HA-infected erythrocytes using rabbit anti-HA antibody. Parasite cytosol is stained with anti-HSP70 antibody.

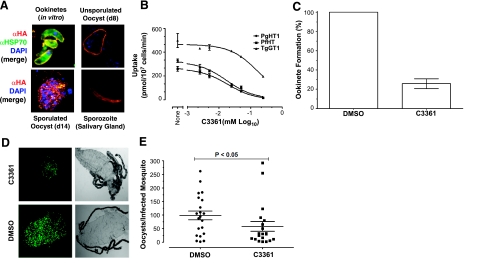

Sexual development of P. berghei is inhibited by a glucose analog

We employed Δpbht1-PbHT1-HA parasites to monitor the endogenous expression of PbHT1 in P. berghei in mosquito stages (Fig. 4A). Ookinetes, unsporulated and sporulated oocysts, and sporozoites isolated from salivary glands exhibited PbHT1-HA at their surface, as also shown by GFP tagging of the endogenous PbHT1 protein previously (9). Since PbHT1 is expressed in sexual stages but refractory to deletion without concurrent complementation, we performed assays to test its importance by inhibiting the transport function of PbHT1 using a recognized glucose analog, C3361. This compound selectively inhibits PfHT1 and P. falciparum blood cultures (25). Hence, we first tested whether the analog would inhibit the uptake of glucose in a dose-dependent manner in our L. mexicana cells expressing PbHT1 or PfHT1 (Fig. 4B). Both PbHT1 and PfHT1 are inhibited to similar degrees by C3361 and exhibit Ki values of ∼8.6 and ∼9.4 μM, respectively. Inhibition of TgGT1 was much lower (Ki∼82 μM) than of Plasmodium transporters. We therefore performed in vitro ookinete culture assays in the presence of C3361 or its carrier solvent DMSO (Fig. 4C). Ookinete formation was reduced by ∼75% in C3361-treated samples, suggesting that exogenous glucose is an important nutrient for differentiation of P. berghei gametocytes into advanced sexual stages. To examine the influence of C3361 on oocyst production in the insect vector, we infected mice with 105 GFP-expressing parasite-infected blood cells and treated the animals with C3361 (2 mg/kg body weight) for 3 d prior to mosquito feeding. The mean parasitemia on the day of insect feeding in DMSO- and C3361-treated mice were 32.5 ± 2.1 and 15.4 ± 1.7% (P<0.05), respectively. However, there was no apparent difference in the proportion of male gametocytes. The numbers of oocysts in the midgut was markedly reduced in mosquitoes that fed on drug-treated animals (Fig. 4D). Quantification of oocysts in infected insects from 3 independent assays revealed a significant decrease (Fig. 4E), in good agreement with the observed reduction in ookinete formation. Protein expression profiling and the C3361 inhibition assays together suggest that glucose and permease, PbHT1, are crucial for ookinete development of P. berghei and, perhaps as a consequence, transmission to the mosquito host.

Figure 4.

A glucose analog, C3361, can inhibit glucose transport by PbHT1 and reduces ookinete development and transmission of P. berghei. A) Surface expression of PbHT1-HA protein during the sexual stages of P. berghei. Immunofluorescence assay was performed with the Δpbht1-PbHT1-HA parasites using rabbit anti-HA antibody. All samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. B) C3361-mediated inhibition of [3H]d-glucose transport (100 μM, 30 s) by Δlmgt promastigotes (2×107) expressing PbHT1, PfHT1, and TgGT1 permeases. Unlike TgGT1, Plasmodium transporters display similar inhibition kinetics. C) Effect of C3361 and DMSO treatment on in vitro formation of ookinetes. Blood samples from P. berghei-infected mice were treated with C3361 (∼100 μM) or DMSO during in vitro differentiation of gametocytes into ookinetes for 18–20 h. Ookinetes were bead-purified and counted. D) Sexual development and transmission of P. berghei, as depicted by representative image of GFP-expressing oocysts in mosquito midgut following treatment of asexual host with C3361 (2 mg/kg body weight) or DMSO. Mice were intravenously infected with 105 parasite-infected red blood cells, and then treated with C3361 or DMSO for 3 d prior to a 30-min blood-meal on anesthetized animals. E) Total oocyst numbers were counted following dissection of mosquitoes on d 10. Graph represents the oocyst output/infected insect from 2 assays. Statistics were performed by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney test.

Glucose is required for the hepatic development of P. berghei

It is unknown whether HT1 is also expressed during the hepatic development of Plasmodium. Hence, we utilized the Δpbht1-PbHT1-HA strain to assess the PbHT1 expression during liver stage development of P. berghei (Fig. 5A). Hepatoma cells were infected with sporozoites to monitor the intracellular hepatic development by IFA. PbHT1 is present on the plasma membrane of liver stages throughout the time course of 48 h. Merozoites budding out of multinucleated schizonts also displayed abundant PbHT1 protein at 68 h. Together, with aforementioned results, these data confirm that PbHT1 is a constitutive transporter expressed in intracellular as well as extracellular stages during the entire life cycle.

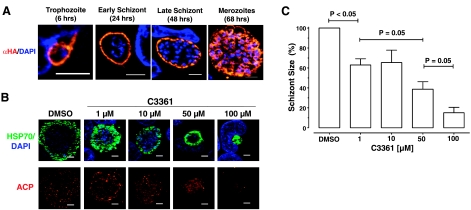

Figure 5.

PbHT1 is expressed during liver stages, and C3361 attenuates the hepatic development of P. berghei. A) Huh7 hepatoma cells were infected with sporozoites isolated from the mosquito salivary glands at an MOI of 3. Immunofluorescence assay was performed with the Δpbht1-PbHT1-HA parasites using rabbit anti-HA antibody. Samples were fixed with methanol and processed at the indicated time points. Scale bars = 5 μm. B) Huh7 cells were infected with sporozoites at an MOI of 3 and fixed with methanol after 68 h before staining with anti-HSP70 and anti-ACP antibodies. Area of the liver schizonts decreased with increasing concentrations of C3361. Apicoplast development and segregation were also inhibited. C) Mean area of ≥20 liver schizonts from 3 experiments was measured using ImageJ (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Statistics were performed by 2-tailed Mann-Whitney test. Values are expressed as means ± se.

Expression of PbHT1 during the liver stages of P. berghei also suggested a potential dependence of the parasite on import of host-derived sugars. To test this notion, we treated sporozoite-infected hepatoma cells with C3361 and monitored P. berghei growth after complete liver merozoite maturation (Fig. 5B). A significant reduction in the mean circumference of the parasites was already apparent at 1 μM C3361. Noticeably, 100 μM C3361 largely arrested the maturation of the liver-stage schizonts. Smaller size together with the reduced expression of acyl carrier protein (ACP), a signature apicoplast protein (26), implies that the P. berghei development is stalled at an early stage during intrahepatic growth. Quantification of 3 independent assays revealed a 40 to 60% decrease in the cross-sectional area of schizonts at micromolar amounts of the analog (1–50 μM C3361; Fig. 5C). Further reduction in the schizont size up to 90% was found at 100 μM C3361. Quantification of size distribution indicated that increasing doses of C3361 cause a progressive shift to smaller schizonts (Supplemental Fig. S2A). More than 90% of schizonts exhibited an area >300 μm2 at 50 μM C3361, which was reduced further to a mean area of ∼100 μm2 at 100 μM of the compound. Growth inhibition of P. berghei by C3361 (IC50∼15 μM) is very much in congruence with the Ki value for PbHT1 (∼8.6 μM), indicating a specific attenuation of hexose uptake.

To further assess the specificity of Plasmodium inhibition by C3361, we tested intracellular replication of Toxoplasma, a related apicomplexan parasite, in C3361-treated hepatoma cells (Supplemental Fig. S2B). As depicted in Fig. 4B, TgGT1 was also inhibited by C3361, albeit with 10-fold higher Ki (82 μM) than PbHT1. Doses as high as 200 μM C3361 did not affect replication of Toxoplasma tachyzoites, nor did it change growth or morphology of the host cells (Supplemental Fig. S2B). To substantiate these findings, we also monitored the growth of T. gondii in human fibroblasts by quantitative fluorescence assay. No significant growth inhibition was observed in C3361-treated samples when compared to DMSO, while the antifolate pyrimethamine (1 μM) arrested T. gondii growth (Supplemental Fig. S2C). These data, together, show that C3361 does not influence growth, morphology, or permissiveness of mammalian cells to T. gondii and P. berghei infection. In agreement, the major glucose and fructose transporters of human (Glut1, Glut5) are not inhibited by up to 1 mM of C3361 in Xenopus assays (25). Nevertheless, the attenuation of parasite growth due to an inhibition of host sugar permeases that would limit the parasite's access to glucose and have an off-target effect on P. berghei cannot be formally excluded. The former assumption, however, supports our results that import of host-derived glucose is critical for the intrahepatic growth of Plasmodium.

In vivo Δpbht1-PfHT1/mouse model for assessment of PfHT1 inhibitors

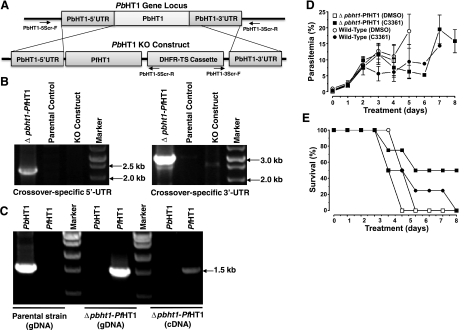

To facilitate the search and evaluation of antimalarial drugs, we exploited the functional resemblance of PfHT1 with PbHT1, and created a transgenic Δpbht1-PfHT1 P. berghei line that is entirely dependent on PfHT1 for its growth (Fig. 6). We designed and transfected a PfHT1-expressing PbHT1 deletion construct (Fig. 6A) and cloned drug-resistant transgenic parasites. PCR genotyping using recombination-specific primers amplified expected fragments in the complemented parasites but not in the parental strain (Fig. 6B). The crossover events were also verified by sequencing of amplified gDNA. The absence of PbHT1 transcripts and the concurrent presence of PfHT1 in the transgenic strain confirmed the clonality and the PfHT1-dependence of the Δpbht1-PfHT1 strain (Fig. 6C). These transgenic parasites developed normally in the mouse and mosquito hosts, consolidating the functional relationship of PbHT1 and PfHT1, in vivo. The Δpbht1-PfHT1 P. berghei/mouse model further validated the observed in vivo essentiality of PbHT1. More importantly, the strain offers an in vivo system for the pharmacological testing of PfHT1 inhibitors.

Figure 6.

Transgenic P. berghei as a model for the in vivo assessment of PfHT1 inhibitors. A) Double-crossover-mediated deletion of PbHT1 by PfHT1-dependent rescue. The PbHT1 gene locus and PfHT1-harboring knockout construct are aligned; arrows indicate primers. B) The 5′ and 3′ recombination-specific (PbHT1–5Scr-F/R and PbHT1–3Scr-F/R) primer sets amplify genomic fragments from Δpbht1-PfHT1 but not in parental strain or plasmid. C) PfHT1 can complement the absence of PbHT1 in the transgenic Δpbht1-PfHT1 parasite line. PCR-based genotyping of the Δpbht1-PfHT1 strain using PbHT1- or PfHT1-specific primers. PbHT1 is detectable in the parental strain but not in Δpbht1-PfHT1. Likewise, PfHT1 can only be amplified from transgenic gDNA or cDNA. D, E) In vivo test of C3361 efficacy in mice intravenously injected with 105 parental- or Δpbht1-PfHT1-infected red blood cells. Following a detectable parasitemia on d 3, mice were treated with C3361 (2 mg/kg body wt) or DMSO. Graphs show parasitemia (D) and animal survival curves (E) from two assays. Values are expressed as means ± se.

To put our model into perspective and practice, mice were preinfected with the Δpbht1-PfHT1 or the parental strain (105 infected erythrocytes) and allowed to develop a detectable parasitemia prior to C3361 treatment. All mice displayed a parasitemia >1% on d 3 of infection. Subsequent daily intravenous injection of C3361 (2 mg/kg body weight) yielded ∼45% reduction in parasitemia from d 3–5 (P<0.05) in compound-treated mice as compared to respective DMSO-treated controls (Fig. 6D), indicative of an effect on PfHT1 and PbHT1 in the transgenic and wild-type parasites, respectively. Survival plots of infected animals also showed a modest benefit in all C3361-treated mice as compared to mock-treated animals (Fig. 6E). As shown in vitro in Leishmania (Fig. 4B), the compound also appears to inhibit the function of Plasmodium transporters, in vivo. Most importantly, notably weak influence of C3361 on parasitemia rejects its antimalarial efficacy despite a reported strong in vitro action in P. falciparum cultures (25). Though the pharmacokinetics of C3361 in mouse is not known, our results illustrate the value of this model for the in vivo appraisal and validation of an analog drug, and bridge a crucial gap in preclinical drug development, i.e., from in vitro screening to in vivo testing of qualified drug candidates.

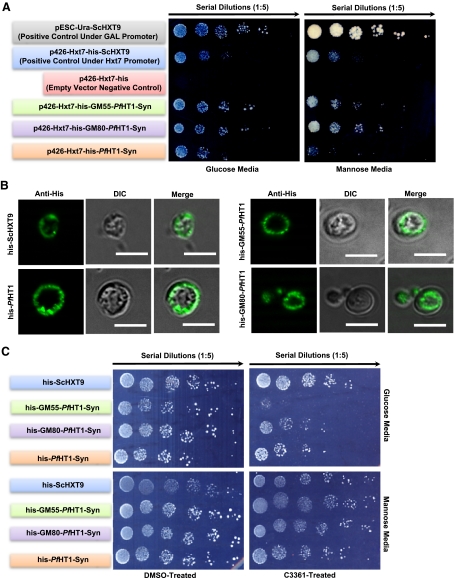

PfHT1-complemented S. cerevisiae for screening of PfHT1 inhibitors

The development of proficient antimalarial drugs stipulates in vitro models for the large-scale screening and selection of candidate PfHT1 inhibitors prior to their pharmacological assessment in animal models. To address this constraint, we focused on establishing another model that would combine user safety and amicability with minimal investment and standard laboratory resources. Toward this end, following our initial futile attempts to express the native PfHT1 ORF in S. cerevisiae, we designed a yeast-optimized synthetic ORF (PfHT1-Syn), and also generated fusion constructs of the full-length PfHT1 with the N-terminal 55 residues of the yeast hexose permease ScHxt9 (his-GM55-PfHT1-Syn) and 80 residues of the yeast inositol transporter ScITR1 (his-GM80-PfHT1-Syn) (Supplemental Fig. S3A). All constructs were expressed in the S. cerevisiae EBY4000 mutant that is compromised in its growth on most sugars, except maltose and galactose (ref. 22 and Fig. 7A). PfHT1-Syn, GM55-PfHT1-Syn as well as GM80-PfHT1-Syn rescued the growth defect on glucose and mannose as carbon sources. The rescue phenotype conferred by PfHT1-Syn is very similar to that of ScHxt9 expressed under the same promoter (HXT7) on both carbon sources. GM55-PfHT1-Syn and GM80-PfHT1-Syn conferred an enhanced complementation compared to PfHT1-Syn, which is most likely due to their improved targeting and optimal conformation at the surface. Note that these cell lines require low glucose (0.06%) for their growth and did not grow on high glucose (2%), which suggests glucose perception and import as independent modules of yeast growth, as conceptualized by recent elegant work (27). Consistent with rescue assays, PfHT1-Syn, GM55-PfHT1-Syn, and GM80-PfHT1-Syn display a peripheral localization in IFA (Fig. 7B). Moreover, all complemented yeast strains reverted to their original phenotype after plasmid loss in nonselective medium (Supplemental Fig. S3B).

Figure 7.

Yeast-optimized PfHT1 can rescue the growth of the S. cerevisiae mutant on glucose and mannose and confers a model for high-throughput screening of analog-based PfHT1 inhibitors. A) Complementation of S. cerevisiae EBY4000 mutant with the illustrated expression constructs. Yeast cells (2 μl) were spotted on uracil-free synthetic medium supplemented with 0.06% glucose or 2% mannose and incubated at 30°C for 3 or 4 d before imaging. B) Immunofluorescence assay of S. cerevisiae expressing the indicated his-tagged proteins. Zymolase-treated transgenic cells from log-phase liquid cultures were fixed with 4% PFA overnight at 4°C, then processed for IFA using mouse anti-His antibody at 1:200 dilution. C) C3361-mediated inhibition of PfHT1 transport activity on 0.06% glucose or mannose. Cells were spotted on agar plates supplemented with C3361 (100 μM) or DMSO and incubated at 30°C for 4 d before imaging. Stability of the compound C3361 is unknown.

In further assays, we examined C3361 (a glucose analog)-mediated inhibition of the transgenic yeast strains in glucose- and mannose-containing agar plates (Fig. 7C). These tests revealed that C3361 retarded the growth of yeast strains complemented with Plasmodium proteins but not with ScHxt9 on glucose. This inhibition was glucose specific, since C3361 did not influence growth on mannose. Taken together, these data further support our functional and inhibition data obtained in L. mexicana. More importantly, they emphasize the expediency of the yeast model for a high-throughput selection of PfHT1 inhibitors.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate that PbHT1 is functionally analogous to PfHT1. Our results reveal that PbHT1, with its constitutive expression, is essential for the entire development of P. berghei in its mammalian hosts and for ookinete formation. Finally, this work describes the generation of transgenic S. cerevisiae and P. berghei models for screening and validation of PfHT1 inhibitors and in vivo assessment of their antimalarial efficacy.

Expression of PfHT1 and PbHT1 in 3 complementary expression systems, L. mexicana, X. laevis, and S. cerevisiae, reveals that both Plasmodium permeases possess similar substrate specificities and transport kinetic properties. Such biochemical properties are also shared by their homologue, TgGT1. The affinity of PbHT1 and PfHT1 for the 4 hexoses, as well as the constitutive expression of PbHT1 at the parasite surface in all life-cycle stages, strongly suggested a likely essential role of these permeases for the entire Plasmodium life cycle. Our data that a recombinant Δpbht1 strain could only be selected by a concurrent exchange of PbHT1 with an epitope-fused PbHT1 or with PfHT1 confirms a vital in vivo role of PbHT1. Notably, our results on C3361-mediated inhibition of P. berghei underscore the additional requirement of PbHT1 and host glucose for the hepatic stages and ookinete development. This offers the potential for a multitarget strategy combining prophylaxis and, perhaps, antimalaria treatment with a substantial reduction in parasite transmission and the clinically silent hepatic stages. We hypothesize that PbHT1 is indispensable for all asexual stages of P. berghei, irrespective of its life cycle phase, and is also critical for its sexual development. Advanced experimental genetics using stage-specific promoters are merited to validate the findings presented in this report.

The contribution and coupling of glucose usage via glycolysis with the TCA cycle for the bioenergetics of apicomplexan parasites have been debated for years (28, 29). In this regard, the importance of glucose for Plasmodium is in stark contrast with Toxoplasma. Despite its functional resemblance with PbHT1 and PfHT1, TgGT1 is dispensable in T. gondii, and its deletion renders a modest 30% growth defect (13). Interestingly, host-derived glutamine can compensate for the lack of glucose in T. gondii, presumably via glutaminolysis and gluconeogenesis, a metabolic capacity that appears distinct from Plasmodium. Though the annotations for glutaminolysis enzymes exist in Plasmodium database, our in silico analyses did not reveal a complete set of enzymes of gluconeogenesis in P. falciparum and P. berghei (Table 2). Absence of the gluconeogenesis pathway would, therefore, render glycolysis essential in Plasmodium, which is deemed dispensable in Toxoplasma. Consistent with this notion, Plasmodium metabolomics has shown that glutaminolysis provides a carbon pool that is functionally distinct from glycolysis (5). Together with the facts that glucose consumption (30) and glycolysis (31) are induced in the parasite-infected erythrocytes, our research supports the notion of glycolysis as being essential in Plasmodium. Also, another finding that glycolytic proteins are up-regulated in mature sporozoites isolated from salivary glands (32) provides support to our results on requirement of glucose for the hepatic development of P. berghei. An intriguing emerging picture is that two otherwise related parasites, i.e., Plasmodium and Toxoplasma, adapt to distinct cellular niches by employing different metabolic networks.

Table 2.

Enzymes of glutaminolysis and gluconeogenesis in Plasmodium and Toxoplasma

| Parasite pathway and associated enzymes | Gene annotations from parasite database |

EC number | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. gondii ME49 | P. falciparum 3D7 | P. berghei ANKA | ||

| Enzymes of glutaminolysis | ||||

| Conversion of glutamine to glutamate | ||||

| Glutamine amidotransferase | TGME49_081490 | PF11_0169 | PB000299.02.0 | 6.3.5.3 |

| Glutaminase (related to class I glutamine amidotransferase) | TGME49_010760 | x | x | NA |

| Glutamine-ammonia ligase (glutamine synthetase) | TGME49_073490 | PFI1110w | PB000319.00.0 | 6.3.1.2 |

| GMP synthase (glutamine hydrolyzing) | TGME49_030450 | PF10_0123 | PB000253.01.0 | 6.3.5.2 |

| Conversion of glutamate to α-ketoglutarate | ||||

| NAD-specific glutamate dehydrogenase | TGME49_049390 | PF08_0132 | PB300354.00.0 | 1.4.1.2 |

| PB301271.00.0 | ||||

| NADP-specific glutamate dehydrogenase | TGME49_093180 | PF14_0164 | PB000714.01.0 | 1.4.1.4 |

| PF14_0286 | PB300230.00.0 | |||

| Enzymes of gluconeogenesis | ||||

| Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase | TGME49_005380 | x | x | 3.1.3.11 |

| TGME49_047510 | ||||

| Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | TGME49_089650 | PF13_0234 | PB001070.000 | 4.1.1.49 |

| TGME49_089930 | ||||

| Pyruvate carboxylase | TGME49_084190 | x | x | 6.4.1.1 |

Genomes of 3 apicomplexan organisms were mined for a broad range of glutaminolysis- and gluconeogenesis-associated genes using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) algorithm and manual inspection. Gene IDs correspond to respective parasite database. EC numbers are depicted as assigned in Toxoplasma database. Functions of enzymes associated with these pathways are based on putative annotations and require experimental verification.

The therapeutic exploitation of PfHT1 to design drugs against human malaria necessitates screening of selective sugar analogs. To this end, PfHT1 has been expressed in X. laevis (25), but utility of this model is limited to functional expression. Feistel et al. (23) developed a model to screen for inhibitors of parasite glucose transporters; however, it uses the human pathogen, L. mexicana. Functional expression of protozoan sugar permeases in S. cerevisiae hexose transport-deficient mutant have failed for more than a decade, and in the case of apicomplexan parasites, defeated the purposes of transporter testing and drug screening for which the strain was initially generated (22). We have expressed a yeast-optimized PfHT1 cDNA encoding a wild-type protein to generate a model strain for high-throughput screening. This is currently the best available model and should greatly facilitate the search for candidate PfHT1 inhibitors. Our yeast strain can be used together with strains expressing human Glut permeases to prescreen for selectivity against the parasite transporter. Two yeast lines expressing human Glut1 and Glut4 are already available for this purpose (33). Finally, the PfHT1-dependent Δpbht1 line expressing a wild-type PfHT1 protein in P. berghei allows in vivo testing of qualified drugs against human malaria. This rodent malaria model is a prerequisite for a wide pharmacological assessment of PfHT1 inhibitors in a standard animal model to deduce the clinical potential.

In summary, this report presents a comprehensive biochemical and genetic characterization of a surface-localized and constitutive pan-hexose permease from P. berghei and reveals the importance of PbHT1 for the asexual and sexual stages of the rodent malaria parasite. Besides, this study epitomizes the importance of appropriate models for the preclinical evaluation of candidate compounds against the human malaria, an urgent priority in the light of emerging resistance against artemisin-based drugs (34).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Grit Meusel (Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany) for her technical assistance. The doctoral research of M.B. is supported by the Helmholtz Foundation (Germany).

This work was also supported by an intramural research grant to K.M., German Research Foundation grant SFB618/C7 to N.G. and R.L., and U.S. National Institutes of Health grant AI25920 to S.L. The NCBI database accession numbers of the nucleotide/protein sequences derived from this research are as follows: PbHT1, HM156735; PfHT1-Synthetic, HM161875; and EtHT1, HM161877.

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sachs J., Malaney P. (2002) The economic and social burden of malaria. Nature 415, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kirk K., Horner H. A., Kirk J. (1996) Glucose uptake in Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes is an equilibrative not an active process. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 82, 195–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Woodrow C. J., Burchmore R. J., Krishna S. (2000) Hexose permeation pathways in Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 9931–9936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lim L., Linka M., Mullin K. A., Weber A. P. M., McFadden G. I. (2010) The carbon and energy sources of the non-photosynthetic plastid in the malaria parasite. FEBS Lett. 584, 549–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Olszewski K. L., Mather M. W., Morrisey J. M., Garcia B. A., Vaidya A. B., Rabinowitz J. D., Llinás M. (2010) Branched tricarboxylic acid metabolism in Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 466, 774–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 6. Gowda D. C., Gupta P., Davidson E. A. (1997) Glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors represent the major carbohydrate modification in proteins of intraerythrocytic stage Plasmodium falciparum. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 6428–6439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schuster F. L. (2002) Cultivation of Plasmodium spp. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15, 355–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Desai S. A., Krogstad D. J., McCleskey E. W. (1993) A nutrient-permeable channel on the intraerythrocytic malaria parasite. Nature 362, 643–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Slavic K., Straschil U., Reininger L., Doerig C., Morin C., Tewari R., Krishna S. (2010) Life cycle studies of the hexose transporter of Plasmodium species and genetic validation of their essentiality. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 1402–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vander Jagt D. L., Hunsaker L. A., Campus M. N., Baack B. R. (1990) D-lactate production in erythrocytes infected with Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 42, 277–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fry M., Beesley E. (1991) Mitochondria of mammalian Plasmodium spp. Parasitology 102, 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Dooren G. G., Stimmler L. M., McFadden G. I. (2006) Metabolic maps and functions of the Plasmodium mitochondrion. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30, 596–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blume M., Rodriguez-Contreras D., Landfear S. M., Fleige T., Soldati-Favre D., Lucius R., Gupta N. (2009) Host-derived glucose and its transporter in the obligate intracellular pathogen Toxoplasma gondii are dispensable by glutaminolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 12998–13003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Daily J. P., Scanfeld D., Pochet N., Le Roch K., Plouffe D., Kamal M., Sarr O., Mboup S., Ndir O., Wypij D., Levasseur K., Thomas E., Tamayo P., Dong C., Zhou Y., Lander E. S., Ndiaye D., Wirth D., Winzeler E. A., Mesirov J. P., Regev A. (2007) Distinct physiological states of Plasmodium falciparum in malaria-infected patients. Nature 450, 1091–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sanchez. M.A., Tryon R., Pierce S., Vasudevan G., Landfear S. M. (2004) Functional expression and characterization of a purine nucleobase transporter gene from Leishmania major. Mol. Mem. Biol. 21, 11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Burchmore R. J., Rodriguez-Contreras D., McBride K., Merkel P., Barrett M. P., Modi G., Sacks D., Landfear S. M. (2003) Genetic characterization of glucose transporter function in Leishmania mexicana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 3901–3906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Seyfang A., Landfear S. M. (2000) Four conserved cytoplasmic sequence motifs are important for transport function of the Leishmania inositol/H+ symporter. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 5687–5693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Siden-Kiamos I., Vlachou D., Machos G., Beetsma A., Water A. P., Sinden R. E., Louis C. (2000) Distinct roles for pbs21 and pbs25 in the in vitro ookinete to oocyst transformation in Plasmodium berghei. J. Cell Sci. 113, 3419–3426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gupta N., Zahn M. M., Coppens I., Joiner K. A., Voelker D. R. (2005) Selective disruption of phosphatidylcholine metabolism of the intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii arrests its growth. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16345–16353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Janse C. J., Frank-Fayard B., Mair G. R., Ramesar J., Thiel C., Engelmann S., Matuschewski K., van Germert G. J., Sauerwein R. W., Water A. P. (2006) High efficiency transfection of Plasmodium berghei facilitates novel selection procedures. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 145, 60–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tsuji M., Mattei D., Nussenzweig R. S., Eichinger D., Zavala F. (1994) Demonstration of heat-shock protein 70 in the sporozoite stage of malaria parasites. Parasitol. Res. 80, 16–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wieczorke R., Krampe S., Weierstall T., Freidel K., Hollenberg C. P., Boles E. (1999) Concurrent knock-out of at least 20 transporter genes is required to block uptake of hexoses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 464, 123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Feistel T., Hodson C. A., Peyton D., Landfear S. M. (2008) An expression system to screen for inhibitors of parasite glucose transporters. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 162, 71–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Woodrow C. J., Burchmore R. J., Krishna S. (1999) Intraerythrocytic Plasmodium falciparum expresses a high affinity facilitative hexose transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 7272–7277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Joët T., Eckstein-Ludwig U., Morin C., Krishna S. (2003) Validation of the hexose transporter of Plasmodium falciparum as a novel drug target. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 7476–7479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Friesen J., Silvie O., Putrianti E. D., Hafalla J. C. R., Matuschewski K., Borrmann S. (2010) Natural immunization against malaria: causal prophylaxis with antibiotics. Sci. Transl. Med. 2, ra49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Youk H., Oudenaarden A. (2009) Growth landscape formed by perception and import of glucose in yeast. Nature 462, 875–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Seeber F., Limenitakis J., Soldati-Favre D. (2008) Apicomplexan mitochondrial metabolism: a story of gains, losses and retentions. Trends Parasitol. 24, 468–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vaidya A. B., Mather M. W. (2009) Mitochondrial evolution and functions in malaria parasites. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63, 249–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Roth E. F., Jr. (1987) Malarial parasite hexokinase and hexokinase-dependent glutathione reduction in the Plasmodium falciparum-infected human erythrocyte. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 15678–15682 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roth E. F., Jr., Calvin M. C., Max-Audit I., Rosa J., Rosa R. (1988) The enzymes of the glycolytic pathway in erythrocytes infected with Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites. Blood 72, 1922–1925 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lasonder E., Janse C. J., van Gemert G. J., Mair G. R., Vermunt A. M., Douradinha B. G., van Noort V., Huynen M. A., Luty A. J., Kroeze H., Khan S. M., Sauerwein R. W., Waters A. P., Mann M., Stunnenberg H. G. (2008) Proteomic profiling of Plasmodium sporozoite maturation identifies new proteins essential for parasite development and infectivity. PLoS Pathogens 4, e1000195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wieczorke R., Dlugai S., Krampe S., Boles E. (2003) Characterisation of mammalian GLUT glucose transporters in a heterologous yeast expression system. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 13, 123–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dondorp A. M., Yeung S., White L., Nguon C., Day N. P., Socheat D., von Seidlein L. (2010) Artemisinin resistance: current status and scenarios for containment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 272–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.