Abstract

Objective

We proposed and tested a novel ECG marker of risk of ventricular arrhythmias (VA).

Methods

Digital orthogonal ECGs were recorded at rest before ICD implantation in 508 participants of a primary prevention ICDs prospective cohort study (mean age 60±12; 377 male [74%]). The sum magnitude of the absolute QRST integral in 3 orthogonal leads (SAI QRST) was calculated. A derivation cohort of 128 patients was used to define a cutoff; a validation cohort (n=380) was used to test a predictive value.

Results

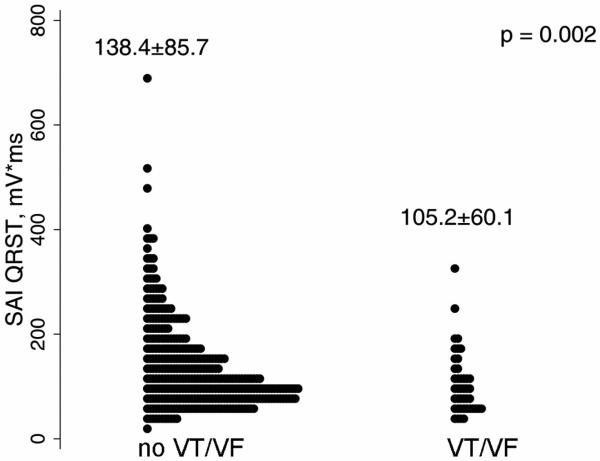

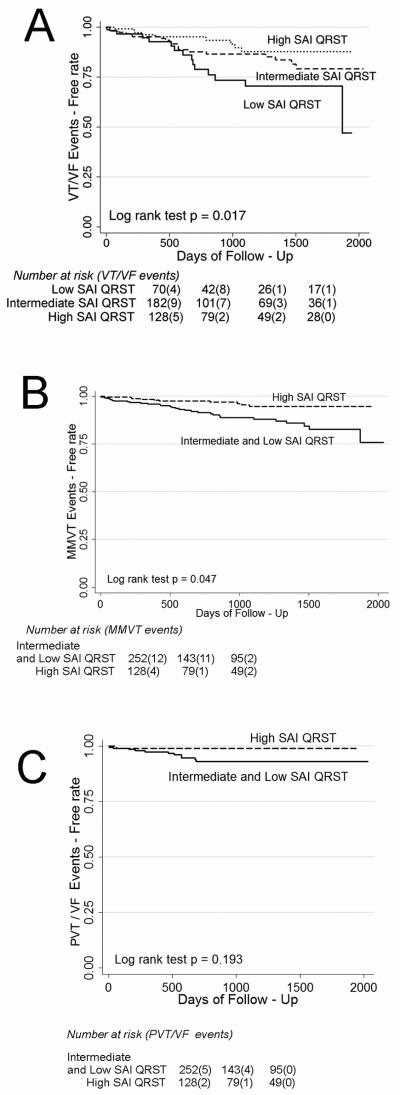

During a mean follow-up of 18 months, 58 patients received appropriate ICD therapies. SAI QRST was lower in patients with VA (105.2±60.1 vs. 138.4±85.7 mV*ms, P=0.002). In the Cox proportional hazards analysis, patients with SAI QRST ≤145 mV*ms had about 4-fold higher risk of VA (HR3.6; 95% CI: 1.96-6.71, p<0.0001), and a 6–fold higher risk of monomorphic ventricular tachycardia [MMVT] (HR 6.58; 95%CI 1.46-29.69, P=0.014), whereas prediction of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation did not reach statistical significance.

Conclusion

High SAI QRST is associated with low risk of sustained VA in patients with structural heart disease.

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) strikes about 350,000 victims in the United States every year.1 Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) are the treatment of choice2-4 for patients at risk for SCD. The need to extend risk stratification beyond use of ejection fraction is well recognized.5, 6 A U-shaped curve for ICD benefit was shown in the analysis of the MADIT II study,5 prompting a search for markers that identify low-risk patients who do not benefit from ICD implantation.

During the century of electrocardiography multiple attempts were made to decipher complex information carried by cardiac electrical signal to obtain important clinical diagnostic and prognostic information. Several approaches have been proposed to develop composite ECG metrics that account for both amplitude and duration of ECG waveforms, with the goal to diagnose hypertrophy7, 8, to determine localization and size of the scar9-11, and to assess heterogeneity of action potential12. Although modern imaging modalities question utility of diagnostic ECG, prognostic ECG markers remain of interest. Arrhythmogenic substrate in susceptible to ventricular arrhythmia (VA) patients with structural heart disease is characterized by specific electrophysiological properties of a scar, cardiac hypertrophy and dilatation, resulting in the conditions of source-sink mismatch13, 14 and dispersion of refractoriness15-17.

In this work we proposed a novel ECG metric, sum magnitude of the absolute QRST integral (SAI QRST). We hypothesized that the SAI QRST predicts VA in primary prevention ICD patients with structural heart disease.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins University IRB, and all patients gave written informed consent before entering the study.

Study population

PROSE-ICD (NCT00733590) is a prospective observational multicenter cohort study of primary prevention ICD patients with either ischemic or non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Patients were eligible for the study if the left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) was less than or equal to 35%, myocardial infarction was at least 4 weeks old, or non-ischemic LV dysfunction was present for at least 9 months. Patients were excluded if the ICD was indicated for secondary prevention of SCD, if patient had a permanent pacemaker or a Class I indication for pacing, if the patient had NYHA class IV, or if the patient was pregnant. Electrophysiologic testing to assess inducibility of VT was performed in 373 patients (73%) at the time of ICD implantation. Left ventricular diastolic diameter (LVDD) was assessed by two-dimensional echocardiography in 225 patients (44.3%). Single-chamber ICD was implanted in 263 patients (52%), dual-chamber ICD in 92 patients (18%), and cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator (CRT-D) in 153 patients (30%). The PROSE-ICD study is an ongoing active project that continues to enroll new patients. This report presents data analysis of study participants with at least 6 months of follow-up, recruited at the Johns Hopkins Hospital site.

Surface ECG recording

Digital orthogonal ECG was recorded before ICD implantation during 5 minutes at rest, using the modified Frank orthogonal XYZ leads18 by PC ECG machine (Norav Medical Ltd, Thornhill, ON, Canada), with a 1000 Hz sampling frequency, high-pass filter 0.05 Hz, low-pass filter 350 Hz, and notch filter 60Hz.

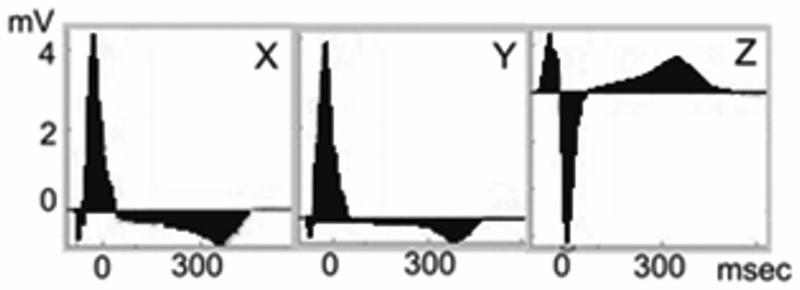

QRST integral measurement

All ECGs were analyzed by customized software in a robust automated fashion. Noise and ventricular premature and ventricular-paced beats were excluded from analysis, but ECG recordings during atrial fibrillation were analyzed. Images of areas under the QRST curve were reviewed to ensure appropriate ECG wave detection. Absolute QRST integral was measured as the arithmetic sum of areas under the QRST curve (absolute area under the QRST curve above baseline was added to the area below baseline, Figure 1), averaged during a 5-min epoch. The sum magnitude of 3 orthogonal leads absolute QRST integral (SAI QRST) was calculated.

Figure 1.

Example of SAI QRST measurement. The sum of the areas under QRST curve on 3 orthogonal ECG leads is calculated.

Endpoints

Appropriate ICD therapies [either shock or antitachycardia pacing (ATP)] for VA served as the primary endpoint for analysis. Programming of the ICD was based on the attending electrophysiologist's clinical evaluation. The ICD device was interrogated during follow-up visits every 6 months. All ICD interrogation data were reviewed by an independent endpoints adjudication committee, blinded to the results of SAI QRST analysis. ICD therapies for monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (MMVT), polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (PVT), or ventricular fibrillation (VF) were classified, as appropriate. MMVT was defined as a sustained VT with stable cycle length and electrogram morphology. PVT was defined as a sustained VT with unstable cycle length and electrogram morphology and average cycle length ≥ 200 ms. VF was defined as sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmia with unstable cycle length and electrogram morphology and average cycle length <200 ms. Sustained appropriately treated VT/VF events were categorized as MMVT group and PVT/VF group.

Statistical analysis

The first 128 consecutive participants of the PROSE-ICD study were included in the derivation cohort. The validation cohort included the remaining 380 PROSE-ICD study participants who were followed prospectively at least 6 months.

Derivation dataset analysis

Cut-off points of SAI QRST were determined in the preliminary analysis of 128 study patients, 15 of whom had sustained VT/VF events during 13±10 months of follow-up. In this derivation set the lowest SAI QRST quartile was ≤69 mV*ms, and the highest quartile was >145 mV*ms. Preliminary survival analysis of the derivation set showed that the lowest quartile of the SAI QRST predicted VT/VF (log rank test P<0.0001) with 100% sensitivity, 78% specificity, 37% positive predictive value, and 100% negative predictive value.

Validation dataset analysis

Validation cohort participants were categorized according to their baseline SAI QRST value, with SAI QRST ≤69 mV*ms labeled low, SAI QRST 70-145 mV*ms labeled intermediate, and SAI QRST >145 mV*ms labeled high. Linear regression analysis was used to study what physiologic parameters correlate with the SAI QRST. One-way ANOVA was used to compare among 3 groups of SAI QRST, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Unadjusted and adjusted Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed for subjects with low, intermediate, or high SAI QRST. The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) statistic was computed to test the equality of survival distributions. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed. An interaction between SAI QRST and bundle branch block (BBB) status, as well as between SAI QRST and LVDD, was tested in the Cox model. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves with area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of SAI QRST for freedom from VT/VF were calculated. STATA 10 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) was used for calculations.

Results

Patient population

Clinical characteristics of the derivation and validation cohort patients are outlined in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between baseline characteristics of the two cohorts. Neither did the rate of VT/VF events differ significantly (15 patients (11.7%) in derivation cohort vs. 43 patients (11.3%) in validation cohort experienced VT/VF; P=0.901). A few differences in patient management were observed: derivation cohort patients were more frequently on beta-blockers and statins, with a slightly higher rate of revascularization procedures.

Table 1.

Clinical and baseline ECG characteristics of derivation and validation cohort

| Characteristic | Derivation cohort (n=128) |

Validation cohort (n=380) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age±SD, y | 59.8±10.8 | 60.3±12.5 | 0.679 |

| Male sex, n(%) | 97(75.8) | 280(73.7) | 0.639 |

| Whites, n(%) | 89(69.5) | 267(70.3) | 0.876 |

| Ischemic CM, n(%) | 65(50.8) | 218(57.4) | 0.194 |

| Baseline LVEF ±SD, % | 21.98±7.69 | 21.99±9.08 | 0.990 |

| QRS, ms | 124.48±34.36 | 120.65±31.65 | 0.272 |

| Complete BBB, n(%) | 28(21.9) | 96(25.3) | 0.440 |

| CRT-D device, n(%) | 40(31.2) | 113(29.4) | 0.189 |

| LVDD±SD, cm | 6.05±1.02 | 5.90±0.84 | 0.304 |

| Body mass index ± SD | 29.34±5.99 | 28.91±6.13 | 0.497 |

| Beta blockers, n(%) | 126(98.4) | 356(93.7) | 0.018 |

| PTCA and/or CABG history, n(%) | 86(67.2) | 204(53.7) | 0.045 |

| Statins, n(%) | 120(93.8) | 321(84.5) | 0.018 |

| NYHA class II, n(%) | 40(31.3) | 110(29.0) | 0.283 |

| NYHA class III, n(%) | 58(45.3) | 199(52.5) | 0.283 |

| Inducible VT, n(%) | 30(23.4) | 93(24.5) | 0.821 |

| Heart rate±SD, bpm | 72.67±14.21 | 73.30±14.68 | 0.805 |

Ventricular tachyarrhythmias during follow-up

During a mean follow-up of 18.0±16.5 months, 43 (11.3% or 7.5% per person-year of follow-up) of the 380 validation cohort patients experienced sustained VA and received appropriate ICD therapies. MMVT with an average cycle length (CL) of 293±38 ms was present in 31 patients (72%). PVT/VF with an average CL 214±18 ms was documented in 12 patients (3.2% or 2.1% per person-year of follow-up). There were significantly fewer patients on beta blockers among those patients receiving subsequent appropriate ICD therapies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical and baseline ECG characteristics of patients with and those without subsequent appropriate ICD therapy for VT/VF

| Characteristic | No VT/VF events (n=337) |

VT/VF events at follow-up (n=43) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age±SD, y | 60.2±12.7 | 60.7±11.3 | 0.776 |

| Male sex, n(%) | 245(72.7) | 35(81.4) | 0.223 |

| White race, n(%) | 233(69.1) | 34(79.1) | 0.180 |

| Ischemic CM, n(%) | 189(56.1) | 29(67.4) | 0.156 |

| Baseline LVEF±SD, % | 22.20±9.20 | 20.38±7.98 | 0.178 |

| QRS, ms | 121.57±31.92 | 114.05±29.07 | 0.122 |

| Bundle branch block, n(%) | 83(24.6) | 13(30.2) | 0.426 |

| CRT-D device, n(%) | 106(31.6) | 7(16.3) | 0.122 |

| LVDD±SD, cm | 5.86±0.96 | 6.41±0.71 | 0.026 |

| Body mass index±SD | 28.79±6.14 | 29.88±5.99 | 0.270 |

| Beta blockers, n(%) | 332(95.5) | 35(81.4) | <0.0001 |

| PTCA and/or CABG history in ischemic CM patients, n(%) |

133(77.3) | 16(57.1) | 0.023 |

| NYHA class II, n(%) | 95(28.3) | 15(34.9) | 0.414 |

| NYHA class III, n(%) | 181(53.9) | 18(41.9) | 0.414 |

| Heart rate±SD, bpm | 72.66±14.51 | 69.54±15.86 | 0.226 |

Predictive value of SAI QRST in validation cohort

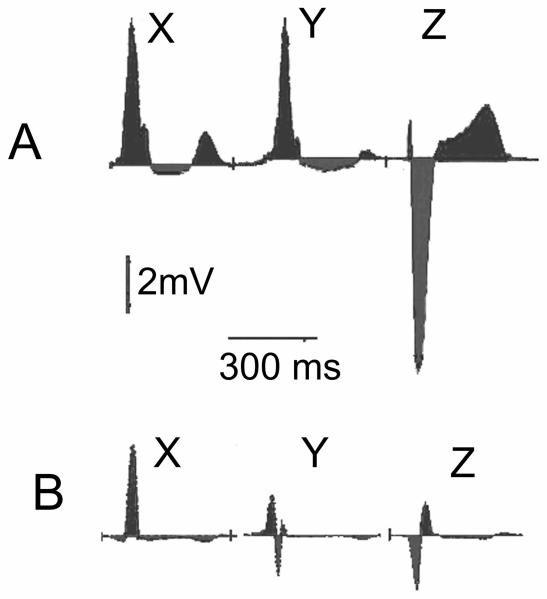

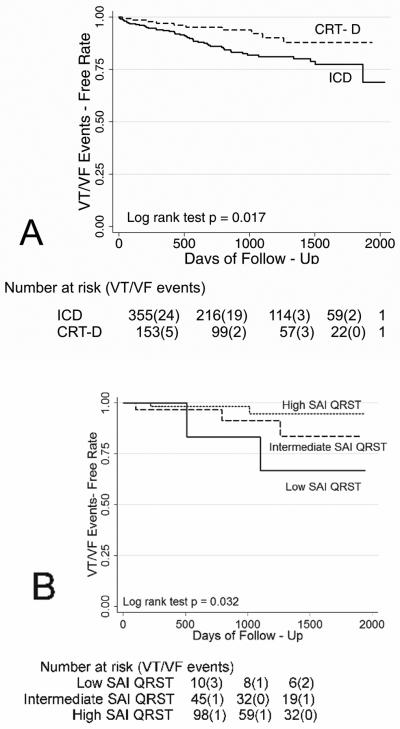

Representative examples of baseline SAI QRST ECG in a patient with and one without subsequent sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmia and appropriate ICD therapy at follow-up are shown in Figure 2. SAI QRST was significantly lower in patients with sustained VA during follow-up (Wilcoxon rank-sum test P=0.004 and Student's t-test P=0.002) [Figure 3]. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that the SAI QRST was significantly predictive for freedom from VT/VF during follow-up (Figure 4A).

Figure 2.

Representative baseline SAI QRST ECG in a patient without (A) and one with (B) subsequent sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmia and appropriate ICD therapy at follow-up.

Figure 3.

SAI QRST distribution in validation cohort patients without and with sustained VA at follow-up.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves for freedom from VT/VF events in validation cohort patients with the low, intermediate, and high SAI QRST. (A) Kaplan-Meyer all VT/VF events free survival; (B) Kaplan-Meyer MMVT events free survival; (C) Kaplan-Meyer PVT/VF events free survival.

In the univariate Cox proportional hazards analysis, patients with high SAI QRST had a 41% decrease in risk of VA compared to patients with intermediate SAI QRST, and accordingly patients with intermediate SAI QRST had a 41% decrease in risk of VA compared to patients with low SAI QRST (hazard ratio for variable “low-intermediate-high SAI QRST”(HR) 0.59; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.39-0.89, P=0.012). SAI QRST predicts MMVT (HR 0.45; 95% CI 0.20-0.99; P=0.049), rather than PVT/VF (HR 0.65; 95% CI 0.40-1.06; P=0.085). Importantly, the risk of VA in patients with low or intermediate SAI QRST was 4-fold higher, than in patients with high SAI QRST (HR 4.05; 95% CI: 2.00-8.20, P<0.0001). Risk of MMVT was more than 6-fold higher (HR 6.58; 95%CI 1.46-29.69, P=0.014) [Figure 4B]. However, prediction of freedom from PVT/VF with high SAI QRST did not reach statistical significance (HR 0.16; 95% CI 0.021-1.25; P=0.080) [Figure 4C].

Low, intermediate, and high SAI QRST

Characteristics of the patients with low, intermediate, and high SAI QRST are presented in Table 3. There were more non-ischemic cardiomyopathy patients with low LVEF, and at the same time more patients with bundle branch block and implanted CRT-D device among the high SAI QRST group. Patients with low SAI QRST had higher body mass index and were more frequently diagnosed with ischemic cardiomyopathy.

Table 3.

Comparison of patients with low, intermediate, and high SAI QRST

| Characteristic | Low SAI QRST ≤69 mV*ms (n=71) |

Intermediate SAI QRST 70 – 145 mV*ms (n=181) |

High SAI QRST >145 mV*ms (n=128) |

ANOVA P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age±SD, y | 57.6±12.9 | 60.0±12.5 | 62.0±12.0 | 0.057 |

| Males, n(%) | 53(74.7) | 140(77.4) | 86(67.2) | 0.133 |

| White race, n(%) | 52(73.2) | 126(69.6) | 89(69.5) | 0.832 |

| Ischemic CM, n(%) | 92(67.7) | 90(56.3) | 35(41.7) | 0.008 |

| Baseline LVEF ±SD, % | 23.5±8.9 | 22.4±8.5 | 20.6±8.8 | 0.043 |

| NYHA class II, n(%) | 36(26.5) | 46(28.8) | 28(33.7) | 0.555 |

| LVDD±SD, cm | 5.90±0.89 | 5.82±0.87 | 6.06±1.13 | 0.423 |

| QRS, ms | 97.5±14.9 | 111.0±25.0 | 147.3±30.8 | <0.0001 |

| Bundle branch block, n(%) | 2(2.8) | 28(15.5) | 66(51.6) | <0.0001 |

| CRT-D device, n(%) | 7(9.9) | 34(18.8) | 72(56.3) | <0.0001 |

| Heart rate±SD, bpm | 73.4 ±15.0 | 73.2±14.7 | 70.6±14.3 | 0.251 |

| QT±SD, ms | 462±61 | 471±62 | 498±62 | 0.0001 |

| Body mass index ± SD | 30.9±7.4 | 28.7±5.8 | 28.0±5.5 | 0.006 |

| Beta blockers, n(%) | 62(95.4) | 151(93.8) | 100(92.6) | 0.763 |

| Revascularization history in ischemic CM patients, n(%) |

61(67.0) | 62(77.5) | 26(90.0) | 0.214 |

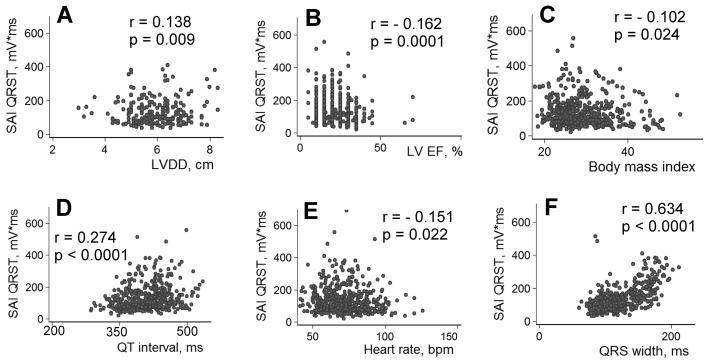

Several parameters were statistically significantly correlated with the SAI QRST: age (r=0.115, P=0.010), LVDD (r=0.138, P=0.009)[Figure 5A], EF (r= −0.162, P=0.0001) [Figure 5B], body mass index (r= −0.102, P=0.024) [Figure 5C], duration of the QT interval (r=0.274, P<0.0001)[Figure 5D], heart rate (r= -0.101, P=0.022) [Figure 5E], beat-to-beat QT variability index19 (r= −0.176, P<0.0001), and QRS width (r=0.634, P<0.0001) [Figure 5F]. SAI QRST was significantly higher in patients with either left or right complete BBB (212.5±100.8 vs. 109.4±56.62, P<0.00001), and it was diminished in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy (121.86±67.48 vs.150.45±96.52, P=0.0002).

Figure 5.

Correlations between SAI QRST, body mass index (BMI) and heart function characteristics. (A) Correlation between the SAI QRST and LVDD; (B) Correlation between SAI QRST and LV EF; (C) Correlation between SAI QRST and BMI; (D) Correlation between SAI QRST and QT interval; (E) Correlation between SAI QRST and heart rate; (F) Correlation between SAI QRST and QRS width.

Multivariate survival analysis in validation cohort

Among other clinical and ECG parameters, use of beta-blockers, implanted CRT-D device and LVDD > 6cm were significant in the univariate Cox regression for prediction of VA. Neither QT nor QRS duration predicted VT/VF events. Ejection fraction with cut-offs 20, 25 and 30% was not associated with the risk of VA.

No significant interaction was found between SAI QRST and presence of BBB, or between SAI QRST and LVDD. In the multivariate Cox regression analysis for VT/VF events, high SAI QRST remained a significant predictor of freedom from VT/VF after adjustment20 for the use of beta-blockers, implanted CRT-D, LVDD, and LV EF. The most complete multivariate Cox regression model for VT/VF prediction is shown in Table 4. Use of beta-blockers and LVDD > 6cm remained significant predictors in the multivariate model too.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate hazard ratios of tested predictors of VT/VF

| Predictor | Unadjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) and P value |

Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) and P value |

|---|---|---|

| Low – Intermediate – High | ||

| SAI QRST | 0.59(0.39-0.89), P=0.012 | 0.54(0.33-0.88), P=0.013 |

| CRT-D device | 0.42(0.17-0.94), P=0.035 | 0.68(0.29-1.58), P=0.369 |

| LVDD >6 cm | 3.57(1.28-10.01), P=0.015 | 3.74(1.30-10.77), P=0.014 |

| LV EF ≤ 25% | 1.12(0.55-2.28), P=0.749 | 1.47(0.68-3.18), P=0.332 |

| Use of beta blockers | 0.28(0.13-0.62), P=0.001 | 0.19(0.08-0.45), P=0.0001 |

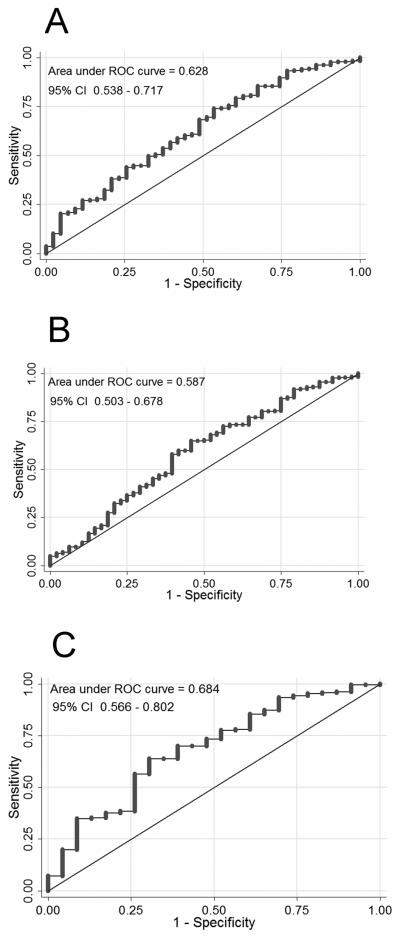

The ROC curve measuring the accuracy of the SAI QRST for freedom from VT/VF showed an AUC of 0.628 (95% CI: 0.538-0.717) [Figure 6A]. SAI QRST ≤145 mV*ms demonstrated 79% sensitivity, 65% specificity, 14% positive predictive value, and 93% negative predictive value for prediction of VA during 1.5 years of follow-up.

Figure 6.

Results of ROC analysis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve on the prediction of the freedom from sustained VT/VF events. (A) for all patients; (B) for patients with narrow QRS ≤ 120ms; (C) for patients with wide QRS > 120 ms.

SAI QRST and QRS width

No significant interaction was found between SAI QRST and the presence of BBB in the multivariate Cox regression model. This outcome means that the SAI QRST predicts VT/VF in patients with and those without BBB. However, SAI QRST was significantly larger in patients with either left or right complete BBB (212.51±100.8 vs. 109.35±56.62, P<0.00001). Therefore, we suggest that the best cut-off value of SAI QRST should be different for patients with wide vs. narrow QRS. For the purpose of this analysis we combined derivation and validation cohorts and categorized all 508 study patients as part of either the narrow QRS subgroup (QRS ≤120 ms, N=272, [53.5%]) or the wide QRS subgroup (QRS >120 ms, N=236 [46.5%]). To define the best SAI QRST cutoff value, ROC curves were constructed separately in patients with narrow and patients with wide QRS (Figures 6B and 6C). In patients with narrow QRS ≤120 ms the SAI QRST of 82 mV*ms provided 60% sensitivity and 55% specificity. In patients with wide QRS >120 ms the SAI QRST of 138 mV*ms provided 64% sensitivity and 70% specificity. A test on the equality of ROC areas between patients with narrow and those with wide QRS did not show a statistically significant difference.

SAI QRST in CRT-D patients

Both derivation and validation cohorts patients were included in this analysis. VT/VF events were less frequent in CRT-D recipients, as compared with ICD patients (Log rank test P=0.017) [Figure 7A]. There was no statistically significant difference in the MMVT rate between ICD and CRT-D patients. However, PVT/VF was observed in 7 patients with single-chamber ICD (3.7%) and 4 patients with dual-chamber ICD (5.2%), but in only 1 CRT-D patient (0.9%) [Log rank test P=0.017]. In univariate Cox regression analysis risk of sustained VT/VF was lower in patients with implanted CRT-D device than in ICD patients (HR 0.45; 95% CI 0.24-0.88; P=0.020).

Figure 7.

(A) Kaplan-Meier curves for freedom from VT/VF events in patients with the ICD and CRT-D device (N=508). (B) Kaplan-Meier curves for freedom from VT/VF events in CRT-D patients with the low, intermediate, and high SAI QRST.

Baseline SAI QRST predicted sustained VA events in CRT-D patients (Figure 7B). In multivariate Cox regression analysis (all patients cohort) in the model that included SAI QRST, presence of BBB, use of beta blockers, LVDD, and type of device (CRT-D or ICD), SAI QRST <145 mV*ms was associated with 4-fold higher risk of VA (HR 4.13; 95% CI 1.96-8.72; P<0.0001), use of beta blockers reduced the risk of VA (HR 0.286; 95% CI 0.131-0.623; P=0.002), and presence of BBB was associated with 3-fold higher risk of VA (HR 2.91; 95% CI 1.38-6.13; P=0.005).

Discussion

In this study we present a new marker of low risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmias and show that SAI QRST >145 mV*ms is associated with a low risk of arrhythmia in structural heart disease patients with implanted ICD for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death.

Substantial evidence supports the idea that patients with structural heart disease have some degree of risk of VA during their lifetime. The strategy of identifying patients at low, rather than high, risk of VA maximizes the benefit of primary prevention ICD, excluding those at low risk of VT/VF for whom the risk/benefit ratio of the ICD, including CHF progression,21 is not favorable. Biostatistical studies22-24 have identified the requirements for a good screening test and underscored the value of ROC analysis. Hazard ratios of most commonly employed predictors of SCD25 range from 2 to 4, which is insufficient for discrimination. In this analysis the SAI QRST ROC exhibited a large AUC and hazard ratio range of 4–6, as well as high sensitivity and negative predictive value, and therefore could be considered as one of the methods for screening of patients with structural heart disease to avoid ICD implantation in those at very low risk of VA.

What is SAI QRST?

The QRST integral was conceived by Wilson et al26 as the time integral of the heart vector27 and expresses the heterogeneity of the AP morphology.28 We calculated sum absolute QRST integral, which is a different metric, not previously explored. Our choice of orthogonal ECG over 12-lead ECG was based on the advantages provided by orthogonal ECG, which permit assessment of the heart vector. Summation of absolute QRST integral of all 3 orthogonal ECG leads allows assessment of the magnitude of total cardiac electrical power and eliminates bias of single lead axis position. The precise electrophysiological meaning of SAI QRST remains to be elucidated. We speculate that (1) the low SAI QRST characterizes significant cancellation of electrical forces as an important pre-existing condition that may facilitate sustained VA; (2) low SAI QRST reflects reduced mass of viable myocardium in patients with structural heart disease; (3) SAI QRST characterizes specific geometry of the heart chambers.

Cancellation of electrical forces results in low SAI QRST

Cancellation of electrical forces in the heart may reduce ECG amplitudes. An estimated 75% of the electrical energy is canceled during ventricular depolarization,29 and 92-99% is cancelled during repolarization.30 Previous experiments showed that AP morphology gradients in different sites of the heart may have opposing directions and cancel out.31 We speculate that decrease in the sum absolute QRST integral due to cancellation coexists with the locally observed increase in APD gradients and increased native QRST integral, or “ventricular gradient”, as marker of a heterogeneity of repolarization or heterogeneity of AP morphology.32, 33

SAI QRST and QRS width

Our results showed significant correlation between SAI QRST and QRS width. Consistent with previous studies34, 35, we did not find a relation between ventricular conduction abnormalities and VT/VF occurrence in the cohort of all study patients. In addition, antiarrhythmic effect of CRT could affect VT/VF rate in patients with wide QRS and BBB at baseline, as about one third of our study patient population had a CRT-D device implanted. Indeed, we confirmed a statistically significantly lower rate of VT/VF events in CRT-D patients. Subgroup analysis showed that presence of BBB was a significant predictor of VT/VF events in ICD patients, but not in CRT-D patients. Although a correlation between the QRS duration and the SAI QRST is obvious, these metrics are not identical. Notably, SAI QRST predicted VT/VF events in patients with any QRS width. Surprisingly, the predictive accuracy of SAI QRST in patients with wide QRS >120 ms was at least as good as in patients with narrow QRS ≤120ms. This important finding may lead to reevaluation of the approach to bundle branch block ECG assessment. A recent report raised the issue of reliability and reproducibility of manual QRS duration measurement.36 The robust automated measurement of SAI QRST could become a reasonable alternative in future.

SAI QRST and left ventricular size

Our results revealed significant correlation between SAI QRST and LVDD. Further studies are necessary to determine the relations between SAI QRST and left ventricular geometry, hypertrophy, and dilatation. Of note, our study patients at baseline had remarkably impaired systolic function, LV dilatation, and frequently a large area of myocardial scar. Several previous studies, focused on healthier population of hypertensive patients, showed that Cornell voltage-duration product (RaVL + SV3 [+6 mm in women]*QRS duration) is associated with the risk of SCD.37-39 Interestingly, in contrast to our findings, a large instead of a small Cornell voltage-duration product was associated with the risk of SCD. Another study of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) showed that higher (not lower) ECG amplitudes and a high 12-lead QRS-amplitude sum predicts SCD in HCM patients.40 Further studies are necessary to clarify this intriguing issue. We speculate that the SAI QRST characterizes electrical rather than geometrical characteristics of the heart, signifying cancellation of electrical forces in patients with large APD heterogeneity and high risk of life-threatening VA.

Methodology of SAI QRST

This is the first report showing the predictive value of SAI QRST. Ongoing analysis is determining whether 5 minutes of recorded ECG is necessary, or whether a shorter recorded ECG can be enough. Ongoing analysis is also making two additional comparisons: the predictive value of SAI QRST calculated from orthogonal ECG versus inverse Dower transforms derived from standard 12-lead ECG and the predictive value of the QRS amplitude versus SAI QRST.

Importantly, virtually any ECG recorded during sinus rhythm or atrial fibrillation is amenable to this analysis, thereby extending the opportunity for non-invasive VT/VF risk stratification in patient populations that would not be eligible for it otherwise.

Further studies are needed to clarify the extent to which SAI QRST reflects underlying cardiac anatomy (LV hypertrophy and/or dilatation, scar size). In this study SAI QRST remained the significant predictor in the model in the presence of the LVDD variable, thus confirming the complementary predictive value of the sum electrical forces descriptor.

Limitations

Appropriate ICD therapy as a surrogate for sudden death may overestimate the frequency of SCD.35 This is a well-recognized and unavoidable limitation in the ICD era, as it would be unethical to withhold ICD therapy to study the actual death rate. The use of ICD events as the end-point for validation of a risk stratifier is frequently viewed as a weak surrogate for actual mortality. However, as soon as the VT/VF risk stratification guides the decision about whether to implant an ICD, then a risk marker that predicts the occurrence of successfully manageable by an ICD rhythms seems more appropriate than a marker that predicts events for which ICD placement would be of no benefit. At the same time, recent studies showed that patients after appropriate ICD shocks demonstrated higher mortality.21

Statistical power of survival analysis for primary end-point (all sustained VA events) and MMVT in this study is good. However, low rate of PVT/VF resulted in low statistical power of survival analysis with PVT/VF end-point. SAI QRST in this study did not predict PVT/VF, but it was highly predictive for MMVT in the primary prevention population of structural heart disease patients. Larger study cohort and longer follow-up are needed for conclusion regarding predictive value of SAI QRST for PVT/VF. At the same time, this preliminary finding may indicate differences in underlying mechanisms of these two types of VT and underscores the difficulties in predicting PVT/VF.

Assessment of scar, LV size and geometry was limited in this study. Further investigation is necessary to determine correlations between SAI QRST and scar size, LV mass, left ventricular hypertrophy and dilatation, and LV volumes.

In summary, SAI QRST is an inexpensive and easily measured at-rest ECG marker for the assessment of VA risk in patients with structural heart disease. High SAI QRST is associated with low risk of sustained VA.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

NIH HL R01 091062 (Gordon Tomaselli) and AHA 10CRP2600257 (Larisa Tereshchenko). Donald W. Reynolds Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Registration identification number: NCT00733590

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Reference List

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De SG, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, Ford E, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott M, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Nichol G, O'Donnell C, Roger V, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Stafford R, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong N, Wylie-Rosett J, Hong Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:480–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.A comparison of antiarrhythmic-drug therapy with implantable defibrillators in patients resuscitated from near-fatal ventricular arrhythmias. The Antiarrhythmics versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1576–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711273372202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Brown MW, Andrews ML. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:877–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, Domanski M, Troutman C, Anderson J, Johnson G, McNulty SE, Clapp-Channing N, Davidson-Ray LD, Fraulo ES, Fishbein DP, Luceri RM, Ip JH. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldenberg I, Vyas AK, Hall WJ, Moss AJ, Wang H, He H, Zareba W, McNitt S, Andrews ML. Risk stratification for primary implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:288–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buxton AE, Lee KL, Hafley GE, Pires LA, Fisher JD, Gold MR, Josephson ME, Lehmann MH, Prystowsky EN. Limitations of ejection fraction for prediction of sudden death risk in patients with coronary artery disease: lessons from the MUSTT study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1150–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okin PM, Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Borer JS, Kligfield P. Electrocardiographic diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy by the time-voltage integral of the QRS complex. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:133–40. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90511-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okin PM, Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kligfield P. Electrocardiographic identification of increased left ventricular mass by simple voltage-duration products. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:417–23. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00371-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmeri ST, Harrison DG, Cobb FR, Morris KG, Harrell FE, Ideker RE, Selvester RH, Wagner GS. A QRS scoring system for assessing left ventricular function after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1982;306:4–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198201073060102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selvester RH, Wagner GS, Hindman NB. The Selvester QRS scoring system for estimating myocardial infarct size. The development and application of the system. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1877–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner GS, Freye CJ, Palmeri ST, Roark SF, Stack NC, Ideker RE, Harrell FE, Jr., Selvester RH. Evaluation of a QRS scoring system for estimating myocardial infarct size. I. Specificity and observer agreement. Circulation. 1982;65:342–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.65.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WILSON FN, Macleod AG, Barker PS, JOHNSTON FD. The determination and the significance of the areas of the ventricular deflections of the electrocardiogram. Am Heart J. 1934:46–61. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleber AG, Rudy Y. Basic mechanisms of cardiac impulse propagation and associated arrhythmias. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:431–88. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romero L, Trenor B, Alonso JM, Tobon C, Saiz J, Ferrero JM., Jr The relative role of refractoriness and source-sink relationship in reentry generation during simulated acute ischemia. Ann Biomed Eng. 2009;37:1560–71. doi: 10.1007/s10439-009-9721-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han J, Moe GK. Nonuniform recovery of excitability in ventricular muscle. Circ Res. 1964;14:44–60. doi: 10.1161/01.res.14.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allessie MA, Bonke FI, Schopman FJ. Circus movement in rabbit atrial muscle as a mechanism of tachycardia. II. The role of nonuniform recovery of excitability in the occurrence of unidirectional block, as studied with multiple microelectrodes. Circ Res. 1976;39:168–77. doi: 10.1161/01.res.39.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laurita KR, Rosenbaum DS. Interdependence of modulated dispersion and tissue structure in the mechanism of unidirectional block. Circ Res. 2000;87:922–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frank E. An accurate, clinically practical system for spatial vectorcardiography. Circulation. 1956;13:737–49. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.13.5.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger RD, Kasper EK, Baughman KL, Marban E, Calkins H, Tomaselli GF. Beat-to-beat QT interval variability: novel evidence for repolarization lability in ischemic and nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1997;96:1557–65. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.5.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregory WM. Adjusting survival curves for imbalances in prognostic factors. Br J Cancer. 1988;58:202–4. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1988.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poole JE, Johnson GW, Hellkamp AS, Anderson J, Callans DJ, Raitt MH, Reddy RK, Marchlinski FE, Yee R, Guarnieri T, Talajic M, Wilber DJ, Fishbein DP, Packer DL, Mark DB, Lee KL, Bardy GH. Prognostic importance of defibrillator shocks in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1009–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pepe MS, Janes H, Longton G, Leisenring W, Newcomb P. Limitations of the odds ratio in gauging the performance of a diagnostic, prognostic, or screening marker. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:882–90. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wald NJ, Hackshaw AK, Frost CD. When can a risk factor be used as a worthwhile screening test? BMJ. 1999;319:1562–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7224.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JH. The limitations of risk factors as prognostic tools. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2615–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldberger JJ. Evidence-based analysis of risk factors for sudden cardiac death. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:S2–S7. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WILSON FN, Macleod AG, Barker PS, JOHNSTON FD. The determination and the significance of the areas of the ventricular deflections of the electrocardiogram. Am Heart J. 1934:46–61. [Google Scholar]

- 27.BURGER HC. A theoretical elucidation of the notion ventricular gradient. Am Heart J. 1957;53:240–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(57)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geselowitz DB. The ventricular gradient revisited: relation to the area under the action potential. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1983;30:76–7. doi: 10.1109/tbme.1983.325172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abildskov JA, KLEIN RM. Cancellation of electrocardiographic effects during ventricular excitation. Sogo Rinsho. 1962;11:247–51. doi: 10.1161/01.res.11.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burgess MJ, Millar K, Abildskov JA. Cancellation of electrocardiographic effects during ventricular recovery. J Electrocardiol. 1969;2:101–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(69)81005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urie PM, Burgess MJ, Lux RL, Wyatt RF, Abildskov JA. The electrocardiographic recognition of cardiac states at high risk of ventricular arrhythmias. An experimental study in dogs. Circ Res. 1978;42:350–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.42.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burton FL, Cobbe SM. Dispersion of ventricular repolarization and refractory period. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;50:10–23. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gardner MJ, Montague TJ, Armstrong CS, Horacek BM, Smith ER. Vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmia: assessment by mapping of body surface potential. Circulation. 1986;73:684–92. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.73.4.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buxton AE, Sweeney MO, Wathen MS, Josephson ME, Otterness MF, Hogan-Miller E, Stark AJ, Degroot PJ. QRS duration does not predict occurrence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with implanted cardioverter-defibrillators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:310–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dhar R, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Estes NA, III, Moss AJ, Zareba W, Daubert JP, Greenberg H, Case RB, Kent DM. Association of prolonged QRS duration with ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II (MADIT-II) Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:807–13. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DE GM, Thambo JB, Ploux S, Deplagne A, Sacher F, Jais P, Haissaguerre M, Ritter P, Clementy J, Bordachar P. Reliability and Reproducibility of QRS Duration in the Selection of Candidates for Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wachtell K, Okin PM, Olsen MH, Dahlof B, Devereux RB, Ibsen H, Kjeldsen SE, Lindholm LH, Nieminen MS, Thygesen K. Regression of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy during antihypertensive therapy and reduction in sudden cardiac death: the LIFE Study. Circulation. 2007;116:700–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.666594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morin DP, Oikarinen L, Viitasalo M, Toivonen L, Nieminen MS, Kjeldsen SE, Dahlof B, John M, Devereux RB, Okin PM. QRS duration predicts sudden cardiac death in hypertensive patients undergoing intensive medical therapy: the LIFE study. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2908–14. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okin PM. Serial evaluation of electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy for prediction of risk in hypertensive patients. J Electrocardiol. 2009;42:584–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ostman-Smith I, Wisten A, Nylander E, Bratt EL, Granelli AW, Oulhaj A, Ljungstrom E. Electrocardiographic amplitudes: a new risk factor for sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:439–49. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]