Abstract

Objectives

To determine the association of early and long-term reductions in worry symptoms after cognitive behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in older adults.

Design

Substudy of larger randomized controlled trial

Setting

Family medicine clinic and large multi-specialty health organization in Houston, TX, between March 2004 and August 2006

Participants

Patients (N=76) 60 years or older with a principal or coprincipal diagnosis of GAD, excluding those with significant cognitive impairment, bipolar disorder, psychosis or active substance abuse.

Intervention

Cognitive behavioral therapy, up to 10 sessions over 12 weeks, or enhanced usual care (regular, brief telephone calls and referrals to primary care provider as needed)

Measurements

Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) administered by telephone at baseline, 1 month (mid-treatment), 3 months (post-treatment), and at 3-month intervals through 15 months (1-year follow-up). We used binary logistic regression analysis to determine the association between early (1-month) response and treatment responder status (reduction of more than 8.5 points on the PSWQ) at 3 and 15 months. We also used hierarchical linear modeling to determine the relationship of early response to the trajectory of score change after post-treatment.

Results

Reduction in PSWQ scores after the first month predicted treatment response at post-treatment and follow-up, controlling for treatment arm and baseline PSWQ score. The magnitude of early reduction also predicted the slope of score change from post-treatment through the 15-month assessment.

Conclusions

Early symptom reduction is associated with long-term outcomes after psychotherapy in older adults with GAD.

Keywords: psychotherapy, generalized anxiety disorder, older adults

Introduction

Community- and clinic-based studies indicate that generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is common in later life. (1) Excessive worry is considered the hallmark symptom of GAD, as underscored by recent proposals to rename the condition “generalized worry disorder” or “generalized worry and anxiety disorder” in the forthcoming fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (2–4) Although several conceptual models of GAD have been proposed, they share a common view of worry as a cognitive avoidance mechanism and/or ineffective coping strategy. (2) Thus, reducing worry is an essential goal in the treatment of GAD.

Clinical trials support the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for GAD in adults. (5) Although CBT has been shown to result in meaningful reductions in worry and related symptoms, meta-analyses of CBT outcomes in general adult samples suggest that effect sizes for treatment outcomes in GAD tend to be lower than those for several other anxiety disorders. (6, 7) Furthermore, response to CBT may be more modest in older adults with GAD than in younger adults. (8, 9) The results of one meta-analysis suggest that older age attenuates the effect of CBT on worry outcomes specifically. (10) The reasons for this are unclear. However, it is known that the course of GAD is typically chronic and in some cases lifelong, (11) and there is evidence that the “characterological” nature of chronic disorders makes symptoms difficult to ameliorate, especially in the short-term. (12) Older adults may have simply lived longer with GAD, (13) compounding the effects of chronicity on treatment outcome. Another possibility is that, in general, older adults may require longer and/or more intensive psychotherapy than younger adults due to age-related cognitive changes that affect language processing, learning, and memory. (14–16)

There is a clear need for further refinement of psychosocial interventions for GAD in older adults. Understanding predictors of worry reduction over time may inform future treatment planning and development. One approach is to examine baseline patient-level variables, such as demographic and clinical features, that predict response to treatment. (17, 18) An alternative approach is to predict post-treatment outcome from early symptom change. (19) To the extent that early response predicts subsequent reduction in worry over the course of treatment and long-term follow-up, the therapist may continue to implement CBT or consider augmentation with other interventions. Early response has predicted favorable psychotherapy outcomes in persons with major depressive disorder (20, 21) and in a university counseling-center population (22). If older adults indeed require longer intervals to experience symptom reduction, (14) then the prognostic value of early response is important to confirm in this population.

To our knowledge, the literature on early response in the treatment of GAD is limited to recent pharmacological trials. In a study of 396 adults with GAD (mean age = 41), initial response to medication (defined by score change on the Hamilton Anxiety Scale after the first and second weeks of treatment) predicted 8-week treatment outcome. (23) In another pharmacologic trial for GAD, response and remission rates also varied systematically as a function of score change in the first 2 weeks of treatment. (24) It is unknown whether a similar phenomenon occurs in psychotherapy for GAD and whether the effect of early response is specific to worry. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no studies yet have addressed whether early response may be related to long-term outcomes for older adults. The aim of this study was to determine the association of early and long-term worry reduction in a randomized controlled effectiveness trial of CBT for GAD in older adults.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited through a family medicine clinic and a large multi-specialty health organization between March 2004 and August 2006. Methodological details of the study have been described elsewhere (25) and are briefly summarized here. Participants were 60 years of age or older and had a principal or coprincipal diagnosis of GAD according to criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (26). Persons with significant cognitive impairment, bipolar disorder, psychosis, or active substance abuse were excluded. Of 968 patients referred to the study, 381 consented to an initial diagnostic interview to determine eligibility. Of these, 134 met inclusion criteria and were subsequently randomized to CBT or an enhanced usual care (EUC) control condition. In June 2005, a brief assessment of depression and worry symptoms in early treatment (administered 1 month after baseline) was added to the protocol. Therefore, early response data were available only for a subset of 76 patients (31 EUC and 45 CBT), who composed the sample for the present study.

Measures

Penn State Worry Questionnaire

The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) (27) is a 16-item self-report questionnaire that assesses symptoms of intrusive, excessive worry. The PSWQ has good internal consistency in samples of older adults with GAD (25, 28, 29) and has shown good sensitivity and specificity in detecting GAD in older adults. (30) The PSWQ assesses worry as a trait (e.g., item anchors range from “Not at all typical of me” to “Very typical of me”), with no specified time frame. However, scores are responsive to psychological treatment of GAD, and the PSWQ is a commonly used outcome measure in GAD trials. (10) In the present study, the PSWQ was administered by telephone with the aid of a blank copy of the instrument for the participant to follow. When administered in this manner, the PSWQ has psychometric properties comparable to those of the self-administered instrument. (31) Although the PSWQ was one of several primary outcomes in the trial, it was the only measure of anxiety that was administered at the 1-month interval.

Procedure

After inclusion and randomization to CBT or EUC, participants completed the PSWQ by telephone. The PSWQ was re-administered at 1 month after baseline (during treatment). Outcome assessments took place immediately at 3 months (post-treatment) and thereafter every 3 months for the next year, ending at 15 months after the baseline assessment.

Participants randomized to CBT received up to 10 sessions of CBT, delivered over a 12-week period by one of five therapists who each had prior experience with the treatment protocol. The session content included education, self-monitoring of anxiety symptoms, motivational interviewing, relaxation training, cognitive therapy, exposure, problem-solving skills training, and behavioral sleep management. After completion of treatment, CBT participants received brief “booster sessions” by telephone to reinforce skill mastery. Telephone booster sessions took place 1 month after treatment and every 3 months thereafter for the duration of the study.

In EUC, study therapists contacted participants by telephone every 2 weeks. Calls were approximately 15 minutes long and were used to monitor mood and anxiety symptoms and to provide limited support (e.g., active listening, encouragement to call if symptoms worsened). Therapists referred EUC participants to their primary care physicians for medical symptoms and notified the physicians directly if participants were judged to require immediate psychiatric care.

Data analysis

Responder analysis

We determined the relationship of early response (defined as change in PSWQ score after 1 month of treatment) to treatment response at 3 months (post-treatment) and 15 months (1-year follow-up). Although there is no established minimal clinically important difference for the PSWQ, we categorized patients according to whether they met or exceeded a magnitude of change that has been observed in previous trials supporting the efficacy of CBT in older adults. We defined treatment responders as those who showed a reduction of ≥ 8.5 points on PSWQ scores relative to their own baseline scores. (25) This criterion represents the average magnitude of change in the CBT arm of previous randomized trials of similar interventions within this clinical population. (29, 32)

Participants were coded as 0 (nonresponder) or 1 (responder) at 3 and 15 months. Participants with missing data were classified as nonresponders for the respective time point(s), which is consistent with our previous work (25) and provides a conservative estimate of participants who experienced clinically significant change. We conducted binary logistic regression analyses of responder status at 3 and 15 months, with the 1-month PSWQ change score, treatment arm (EUC or CBT), and baseline PSWQ score as predictors. In a separate step we added a term to test the interaction of treatment assignment and 1-month PSWQ score change. We used SPSS for Windows, Version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc.) to perform the logistic regression analyses.

Analysis of change trajectory

We conducted a second analysis to determine the linear effect of early change on the long-term trajectory of worry outcome through follow-up. In order to accommodate repeated PSWQ scores, we used a multilevel modeling strategy. Multilevel modeling (also known as hierarchical linear modeling) is appropriate for models that contain both within-subjects variables that change over time (e.g., repeated measures) and time-invariant, between-subjects variables (e.g., baseline values or participant traits). Outcomes on multiple measurement occasions are nested within participants to create individual change trajectories, or slopes. These slopes can then be analyzed for systematic differences as a function of between-subject variables. Multilevel model parameter estimates are robust to small to moderate amounts of missing data. (33)

We first constructed “level-1” individual growth models predicting PSWQ scores from time (3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 months) and a random error term. We then added three “level-2” variables – baseline PSWQ score, 1-month PSWQ change score, and treatment arm – as between-subjects predictors of the effect of time on PSWQ score. HLM 6.08 (Student version; Scientific Software International, Inc., Lincolnwood, IL) was used to fit the multilevel model using restricted maximum likelihood estimation.

Results

Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics are listed in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in any participant characteristics at baseline. A t test for independent groups indicated that participants in the CBT and EUC groups had comparable baseline PSWQ scores (53.8 [SD = 10.1] in CBT versus 58.4 [SD = 12.0] in EUC), t(74) = 1.793, p = .077.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Baseline

| CBT Group (n = 45) |

EUC Group (n = 31) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD |

| Age | 45 | 66.7 | 6.6 | 31 | 68.2 | 5.5 |

| Years of education | 45 | 16.09 | 2.7 | 31 | 16.00 | 3.0 |

| Sex | n | % | n | % | ||

| Female | 38 | 84.4 | 23 | 74.2 | ||

| Male | 7 | 15.6 | 8 | 25.8 | ||

| Race | ||||||

| Asian | 2 | 4.4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Black/African-American | 8 | 17.8 | 4 | 12.9 | ||

| White | 33 | 73.3 | 27 | 87.1 | ||

| More than one category | 1 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other | 1 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 4 | 8.9 | 2 | 6.5 | ||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 39 | 86.7 | 29 | 93.5 | ||

| Unknown/missing | 2 | 4.4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Mental health comorbidities/treatment | ||||||

| Any depression | 23 | 51.1 | 10 | 32.3 | ||

| Any other anxiety disorder | 24 | 53.3 | 11 | 35.5 | ||

| Taking any psychotropic medication | 19 | 42.2 | 12 | 38.7 | ||

Missing data

Of the 76 participants who entered the study, 5 (7%) provided no further data after the 1-month assessment. Overall missing data rates at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 months were 8%, 24%, 24%, 30%, and 29%, respectively, and were due to either dropout or noncompliance with assessment procedures. These rates are comparable to those of previous studies of psychotherapy for GAD in older adults (29, 34). Dropouts and completers did not differ significantly with respect to demographic variables, baseline PSWQ, or 1-month PSWQ change scores.

Prediction of treatment response

Among the 76 participants, 23 (30.3%) were deemed responders at 3 months and 28 (36.8%) were responders at 15 months. Results of a t test for independent groups indicated that 3-month responders had a significantly larger magnitude of change on the PSWQ after 1 month of treatment (mean change of −6.5 points [SD = 9.5] at 1 month) compared with 3-month nonresponders (mean change of 1.4 points [SD = 9.1] at 1 month), t(74) = 3.423, p < .001. Similar differences in early PSWQ score change were also found between 15-month responders and nonresponders (mean 1-month PSWQ change scores of −5.3 points [SD = 9.6] and 1.6 points [SD = 9.3], respectively), t(74) = 3.069, p = .003. In binary logistic regression analyses, baseline PSWQ score, treatment arm, and 1-month PSWQ change score significantly predicted responder status at 3 months, whereas at 15 months the only significant predictor of responder status was the 1-month PSWQ change score (see Table 2). The added interaction of 1-month change score and treatment arm was not a significant predictor of responder status at 3 months (Wald chi-square [1] = .30, OR = 1.05, p = .58) or 15 months (Wald chi-square [1] = .09, OR = 1.02, p = .77).

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Analysis Predicting Clinically Significant Response at 3 and 15 Months

| β | SE | Wald chi-square |

df | p | Odds ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors of responder status at 3 months | ||||||

| Treatment arm† | 1.955 | .725 | 7.267 | 1 | .007* | 7.066 |

| PSWQ score at baseline | .079 | .036 | 4.929 | 1 | .026* | 1.083 |

| PSWQ 1-month change score | −.092 | .043 | 4.651 | 1 | .031* | .912 |

| Predictors of responder status at 15 months | ||||||

| Treatment arm | .669 | .543 | 1.519 | 1 | .218 | 1.952 |

| PSWQ score at baseline | .006 | .027 | .052 | 1 | .820 | 1.006 |

| PSWQ 1-month change score | −.087 | .035 | 6.153 | 1 | .013* | .917 |

Statistically significant at the .05 level.

Binary variable; 0 = Usual care, 1 = Cognitive behavioral therapy

Note. Persons with missing data at 3 month and 15 months were coded as nonresponders for the respective interval(s). PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire

Equating all missing observations with non-response to treatment potentially underestimates the number of actual responders and may have biased the results of responder analyses. To test the robustness of our logistic regression models, we re-ran the analyses under three alternative scenarios for replacing missing data: (1) all missing observations coded as responders (yielding overall treatment response rates of 38.2% at 3 months and 65.8% at 15 months); (2) responder status for missing observations coded based on the last actual observation (response rates of 30.3% at 3 months and 46.1% at 15 months); and (3) responder status assigned at random to missing observations (response rates of 32.9% at 3 months and 52.6% at 15 months). In the latter two scenarios, 1-month PSWQ score change remained a significant predictor of both 3-month and 15-month responder status. However, 1-month response was not a significant predictor of outcomes in first scenario, which yielded inflated response rates. Thus, change in PSWQ score after the first month predicted subsequent treatment response in both a conservative estimation scenario equating all missing data with nonresponse and in alternative scenarios in which missing observations could be coded as response or nonresponse.

Twenty-four (31.6%) participants in our sample had relatively low PSWQ scores at baseline (i.e., less than 50, a cutoff previously determined to have good sensitivity and specificity for GAD in older adults [35]). These participants were significantly less likely than those with baseline scores ≥ 50 to be responders at 3 months (12.5% v. 38.5%, p = .03, Fisher’s exact test used for small cell size). However, a chi-square test indicated no significant relationship between low baseline score and responder status at 15 months, χ2 (1) = .89, p = .35.

Predictors of outcome trajectory over time

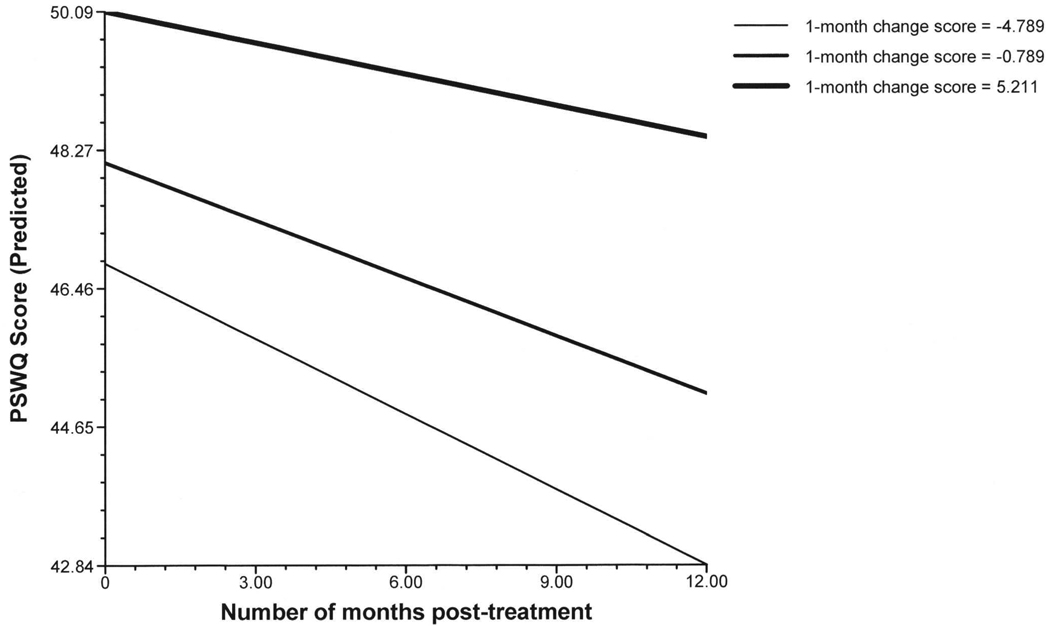

Multilevel model parameters are displayed in Table 3. All three level-2 predictor variables were significantly associated with the model intercept (i.e., the point estimate of the 3-month PSWQ score). However, only the 1-month PSWQ change score significantly predicted the slope (rate) of further change between 3 and 15 months (model graph shown in Figure). Thus, treatment arm, baseline PSWQ, and 1-month PSWQ change score were all related to post-treatment PSWQ scores, whereas the 1-month change score alone predicted the rate of further change through one year of follow-up. The addition of an interaction term (treatment arm by 1-month PSWQ change score) did not yield additional significant model parameters.

Table 3.

Predictors of Parameters for a Line Modeling PSWQ Outcomes Across 5 Measurement Occasions (3, 6, 9, 12, and 15 Months)

| β | SE | t | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors of line intercept (3-month PSWQ estimate) | |||||

| Treatment arm† | −4.997 | 1.755 | −2.85 | 67 | .006* |

| PSWQ score at baseline | .742 | .088 | 8.445 | 67 | < .001* |

| PSWQ 1-month change score | .330 | .095 | 3.455 | 67 | .001* |

| Predictors of line slope | |||||

| Treatment arm | .080 | .140 | .571 | 285 | .568 |

| PSWQ score at baseline | .008 | .007 | 1.112 | 285 | .267 |

| PSWQ 1-month change score | .019 | .008 | 2.434 | 285 | .016* |

Statistically significant at the .05 level.

Binary variable; 0 = usual care, 1 = Cognitive behavioral therapy

Figure 1.

Prediction of long-term change trajectories on the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) as a function of the 1-month PSWQ change score. Lines represent 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of PSWQ 1-month difference scores, respectively. Baseline PSWQ score and treatment arm are held constant at their respective means.

Predictors of early response to treatment

The observed relationship between 1-month PSWQ change and 15-month response led us to analyze post hoc whether the magnitude of 1-month score change was associated with demographic and clinical characteristics. We found no effect of participant age, race, ethnicity, gender, or years of education on 1-month PSWQ change scores (Table 4). We also explored whether expectancies for treatment predicted the magnitude of early change, which may have reflected a self-report bias. Finally, we tested whether optimism or depressed mood was associated with greater or lesser score change during the first month, respectively. We computed Pearson correlations to test the association between 1-month score change and participants’ scores on the Expectancy Rating Scale, a measure of treatment expectancies; (36) the Life Orientation Test, a measure of trait optimism; (37) and the Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition, a measure of depressed mood symptoms. (38) There were no significant correlations between early symptom change and baseline scores on any of these measures (Table 4).

Table 4.

Predictors of 1-month Change in PSWQ Score from Baseline

| Variable | n | Mean PSWQ Change at 1 month |

t | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 15 | −3.40 | 1.07 | 74 | .29 |

| Female | 61 | −.36 | ||||

| Race | White | 60 | −.80 | .27 | 74 | .79 |

| Not white | 16 | −1.56 | ||||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic/Latino | 6 | −2.83 | −.45 | 72 | .65 |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 68 | −.93 | ||||

| Correlation with PSWQ Change at 1 month (Pearson r) | df | p | ||||

| Age | 76 | .09 | 74 | .43 | ||

| Years of education | 76 | −.12 | 74 | .28 | ||

| Expectancy Rating Scale | 70 | −.04 | 68 | .78 | ||

| Life Orientation Test | 76 | .16 | 74 | .16 | ||

| Beck Depression Inventory-II | 76 | −.13 | 74 | .28 | ||

Note. PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Two cases had missing ethnicity data, and 6 cases had incomplete or missing data for the Expectancy Rating Scale.

Discussion

We studied the relationship between early reduction in worry symptoms and subsequent short- and long-term worry outcomes in a subsample of older primary care patients with GAD who participated in a larger clinical trial. Reduction in PSWQ scores after the first month of participation predicted PSWQ scores and responder status at post-treatment, controlling for baseline PSWQ score and treatment arm. Furthermore, the magnitude of early reduction in worry symptoms – but not baseline worry severity or treatment arm – predicted the slope of change from post-treatment through the 15-month assessment. Notably, we found no evidence to suggest that these effects differed between the CBT or enhanced usual care condition.

The mean 1-month PSWQ change score among responders at post-treatment was −6.5 points. Although this magnitude of change falls short of being “clinically significant” by our definition, it may represent a noticeable early reduction in symptom severity nonetheless. Participants who ultimately had a favorable response to treatment tended to show improvement within the first month, in contrast to those who had improved little on average by post-treatment. This finding somewhat contradicts our expectation that older adults respond to psychotherapy more slowly than younger adults. (14) It is possible that, in a subset of older adults, the trajectory of change is comparable to that of younger adults. The marked variability in early change scores among both responders and nonresponders suggests heterogeneity in response patterns that may be masked when examined in aggregate. Unfortunately, our sample consisted exclusively of older adults and we are unable to draw definitive conclusions about differences in change trajectories compared to younger adults.

Early response should be more thoroughly investigated as a prognostic factor in treatment outcomes with older adults. Furthermore, the lack of any response after an initial trial of therapy should be studied as a possible negative prognostic factor. (19) Clearly, not all patients respond to treatment rapidly, but whether to manage early and later responders differently is unclear. The extent to which the requisite “dose” of psychotherapy is determined by early response is an interesting but largely unexplored question. Knowledge of symptom change patterns may inform future trials of therapy augmentation, extension, or even abbreviation for patients according to their early response to treatment.

The present study and previous studies link early symptom change with treatment outcome, but it is not clear what early response represents. Some authors have suggested that early symptom reduction is akin to a placebo response, mediated by “common” or “nonspecific” factors. (39) Others have argued that marked changes can occur early in treatments that quickly implement cognitive behavioral techniques. (40) As we found no significant interaction of treatment arm and early score change in our predictor models, we conclude that the positive effect of early symptom change was not specific to persons who received CBT. Since our usual care condition also received an intervention, albeit a weak one, we were unable to determine whether early improvement predicted later symptom change in the absence of an intervention.

Although early response was not associated with any variables that we identified, early responders may have differed on characteristics not measured in this study, such as Axis II pathology, interpersonal functioning, and more subtle aspects of treatment engagement that we did not measure. Fennell and Teasdale (20) noted that early responders to CBT were distinguished by their acceptance of the rationale for treatment, their reaction to homework, and a stepwise, progressive approach to the topical content of treatment sessions. Early responders may also have had few external barriers to change. In one of the few studies of early symptom change in older adults, Martire et al. (41) found that family members’ subjective burden predicted early response to psychotherapy for depression. Thus, early responders may have benefited from internal or external factors that facilitated rapid progress even with minimal intervention.

Our study was limited by several factors. First, our criterion for treatment response, though informed by previous clinical trial outcomes, has not been validated against a “gold standard” diagnostic interview. Furthermore, our response criterion may have been more difficult to achieve among persons with lower baseline scores, at least in the short term. On the other hand, our criterion provided a lower threshold for treatment response than would other common conventions for defining response (e.g., requiring a magnitude of change greater than 20% of the baseline score or the baseline standard deviation). An alternative is to adjust treatment response criteria according to baseline symptom severity, but we are not aware of any empirical guidance for this practice that we could readily apply to our sample. We also considered defining response according to a fixed clinical cutoff score. A PSWQ score of 50 has shown good sensitivity and specificity to the diagnosis of GAD in older adults, but nevertheless misclassified 25% of patients. (35) More importantly, a cutoff score of 50 would present problems for our sample, in which nearly a third of participants entered the trial with PSWQ scores under 50. Pending a more rigorous evaluation of a treatment response criterion for the PSWQ, we believe that our empirically informed criterion represents a reasonable and achievable goal for clinically significant improvement in worry symptoms.

Our missing data rates, though not unusual for this type of study, warrant mention. Although for linear analyses we used a modeling strategy that is known to be robust to missing data, missing data are potentially more problematic for our treatment responder analyses. Our conservative decision to code participants with missing data as nonresponders may have systematically biased the outcomes of our responder analysis. However, two less extreme alternative methods for replacing missing data yielded comparable findings regarding the prediction of 3- and 15-month responder status from 1-month change scores. We believe that our treatment response model was therefore relatively robust to missing data. Nevertheless, specific parameter estimates should be interpreted with caution. Odds ratios for our responder analysis, for instance, should be interpreted liberally as these estimates are based on assumptions of limited treatment response in persons who dropped out of treatment or did not comply for assessment procedures.

Although we believe that early response is an interesting potential prognostic factor in long-term response, our data are not sufficient to specify a threshold for defining early response. Our relatively homogenous sample, which was predominantly White, female, and highly educated, is a further limitation to the generalizability of our findings. Finally, although worry is the defining feature of GAD, excessive worry alone is insufficient for the diagnosis. Because of our exclusive focus on worry symptoms, our findings are not generalizable to other symptoms that are not specific to GAD, such as irritability, restlessness, and sleep disturbance. At present we can only speculate that early worry reduction would also predict improvement in somatic symptoms.

In conclusion, we found a significant association between early symptom reduction and long-term outcomes in older adults enrolled in a randomized clinical trial for GAD. This finding was not specific to treatment assignment. Our results are consistent with those of other studies that have linked early response and clinical outcomes. Our study is unique in that we have found this pattern in older adults, who are usually considered to be slower responders to treatment. Differentiating early responders, and understanding why this subgroup tends to have better outcomes, are important topics for further intervention research in this population.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (R01-MH53932) for $1,826,539 from 2003–2008 to the last author and supported in part by the Houston Center for Quality of Care & Utilization Studies, Health Services Research and Development Service, Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs (HFP90-020). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bryant C, Jackson H, Ames D. The prevalence of anxiety in older adults: Methodological issues and a review of the literature. J Affective Disord. 2008;109:233–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behar E, DiMarco ID, Hekler EB, et al. Current theoretical models of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD): Conceptual review and treatment implications. J Anx Dis. 2009;23:1011–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews G, Hobbs MJ, Borkovec TD, et al. Generalized worry disorder: A review of generalized anxiety disorder and options for DSM-V. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:134–147. doi: 10.1002/da.20658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association: 300.02 Generalized Anxiety Disorder [DSM-5 Development web site] [Accessed March 10, 2010]; Available at: http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=167.

- 5.Hunot V, Churchill R, Silva de Lima M, et al. Psychological therapies for generalized anxiety disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 January;1:CD001848. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001848.pub4. [serial online] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman SG, Smits JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:621–632. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart RE, Chambless DL. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: A meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:595–606. doi: 10.1037/a0016032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayers CR, Sorrell JT, Thorp SR, et al. Evidence-based psychological treatments for late-life anxiety. Psychol Aging. 2007;22:8–17. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohlman J. Psychosocial treatment of late-life generalized anxiety disorder: Current status and future directions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:149–169. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Covin R, Ouimet AJ, Seeds PM, et al. A meta-analysis of CBT for pathological worry among clients with GAD. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Mohlman J, et al. Generalized anxiety disorder in late life: Lifetime course and comorbidity with major depressive disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:77–80. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kopta SM, Howard KI, Lowry JL, et al. Patterns of symptomatic recovery in psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:1009–1016. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck JG, Stanley MA, Zebb BJ. Characteristics of generalized anxiety disorder in older adults: A descriptive study. Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:225–234. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knight BG. Adaptations of psychotherapy for older adults, in Psychotherapy with Older Adults. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. pp. 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohlman J, Gorenstein EE, Kleber M, et al. Standard and enhanced cognitive-behavior therapy for late-life generalized anxiety disorder: Two pilot investigations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:24–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wetherell JL, Lenze EJ, Stanley MA. Evidence-based treatment of geriatric anxiety disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;28:871–896. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andreescu C, Mulsant BH, Houck PR, et al. Empirically derived decision trees for the treatment of late-life depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:855–862. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durham RC, Chambers JA, Macdonald RR, et al. Predictive validity of two prognostic indices for generalized anxiety disorder. Int J Cogn Ther. 2009;2:383–399. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van HL, Schoevers RA, Kool S, et al. Does early response predict outcome in psychotherapy and combined therapy for major depression? J Affect Disord. 2008;105:261–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fennell MJV, Teasdale JD. Cognitive therapy for depression: Individual differences and the process of change. Cogn Ther Res. 1987;11:253–271. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lutz W, Stulz N, Köck K. Patterns of early change and their relationship to outcome and follow-up among patients with major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2009;118:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambert MJ. Early response in psychotherapy: Further evidence for the importance of common factors rather than “placebo effects.”. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:855–869. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rynn M, Khalid-Khan S, Garcia-Espana JF, et al. Early response and 8-week treatment outcome in GAD. Depress Anxiety. 2006;23:461–465. doi: 10.1002/da.20214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollack MH, Kornstein SG, Spann ME, et al. Early improvement during duloxetine treatment of generalized anxiety disorder predicts response and remission at endpoint. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42:1176–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stanley MA, Wilson NL, Novy DM, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy for generalized anxiety among older adults in primary care: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1460–1467. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, et al. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28:487–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck JG, Stanley MA, Zebb BJ. Psychometric properties of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire in older adults. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 1995;1:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wetherell JL, Gatz M, Craske MG. Treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:31–40. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webb SA, Diefenbach G, Wagener P, et al. Comparison of self-report measures for identifying late-life generalized anxiety in primary care. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2008;21:223–231. doi: 10.1177/0891988708324936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Senior AC, Kunik ME, Rhoades HM, et al. Utility of telephone assessments in an older adult population. Psychol Aging. 2007;22:392–397. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss B, Calleo J, Rhoades H, et al. The utility of generalized anxiety disorder severity scale (GADSS) with older adults in primary care. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:E10–E15. doi: 10.1002/da.20520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stanley MA, Beck JG, Novy DM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of late-life generalized anxiety disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:309–319. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Webb SA, Diefenbach G, Wagener P, et al. Comparison of self-report measures for identifying late-life generalized anxiety in primary care. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2008;21:223–231. doi: 10.1177/0891988708324936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. Journal of Behaviour Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1972;3:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implication of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychol. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beck AT, Sheer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ilardi SS, Craighead WE. The role of nonspecific factors in cognitive behavior therapy for depression. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 1994;1:138–156. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang TZ, DeRubeis RJ. Reconsidering rapid early response in cognitive behavioral therapy for depression. Clin Psychol Sci Prac. 1999;6:283–288. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martire LM, Schulz R, Reynolds CF, et al. Impact of close family members on older adults’ early response to depression treatment. Psychol Aging. 2008;23:447–452. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.23.2.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]