Abstract

Aims

College students who violate alcohol policies are often mandated to participate in alcohol-related interventions. This study investigated (a) whether such interventions reduced drinking beyond the sanction alone, (b) whether a brief motivational intervention (BMI) was more efficacious than two computer-delivered interventions (CDIs), and (c) whether intervention response differed by gender.

Design

Randomized controlled trial with four conditions (BMI, Alcohol 101 Plus™, Alcohol Edu for Sanctions, delayed control) and four assessments (baseline, 1, 6, and 12 months).

Setting

Private residential university in the USA.

Participants

Students (n = 677; 64% male) who had violated campus alcohol policies and were sanctioned to participate in a risk reduction program.

Measurements

Consumption (drinks per heaviest and typical week, heavy drinking frequency, peak and typical blood alcohol concentration), alcohol problems, and recidivism.

Findings

Piecewise latent growth models characterized short-term (1-month) and longer-term (1–12 months) change. Female but not male students reduced drinking and problems in the control condition. Males reduced drinking and problems after all interventions relative to control, but did not maintain these gains. Females reduced drinking to a greater extent after a BMI than after either CDI, and maintained reductions relative to baseline across the follow-up year. No differences in recidivism were found.

Conclusions

Male and female students responded differently to sanctions for alcohol violations and to risk reduction interventions. BMIs optimized outcomes for both genders. Male students improved after all interventions, but female students improved less after CDIs than after BMI. Intervention effects decayed over time, especially for males.

Keywords: brief intervention, computer-delivered intervention, college drinking, alcohol abuse prevention, mandated students, gender

Many underage college students in the United States drink alcohol despite legal prohibitions (1). When alcohol use is conspicuous or when it causes problems, college administrators often mandate that students participate in an alcohol-related intervention. Mandated interventions can be efficacious (2–7), but three caveats are noted.

First, research has not clearly disentangled response to the sanction from response to an intervention. Some studies suggest that simply being sanctioned leads to reductions in consumption and problems; such a “sanction effect” has been observed in female students assigned to wait-list control (8) and in retrospective reports of consumption after the sanction event but before enrollment in a study (4). Morgan, White, and Mun (9) reported greater self-initiated drinking reductions after more serious sanctions. Therefore, one purpose of this study was to estimate the additional benefit of an alcohol intervention beyond the effects of time and the sanction alone.

Second, although several studies demonstrate the efficacy of brief motivation interventions (BMIs) in comparison to education-only (3) or minimal interventions (7), few have compared BMIs with computer-delivered interventions (CDIs), which can be efficacious with college student drinkers (10, 11). Therefore, this study was designed to compare the relative efficacy of an empirically-supported, face-to-face BMI and two CDIs: Alcohol 101 Plus™ (an interactive program distributed on CD-ROM by The Century Council) and AlcoholEdu® for Sanctions (a web-based course by Outside the Classroom). These CDIs differ in structure and content, and were evaluated under typical administration conditions.

Third, the extent to which gender affects response to mandated interventions is understudied. Gender effects have been observed in brief alcohol interventions in primary care favoring men (12), a finding consistent with observations that women often respond to a minimal control conditions as well as to brief interventions (13). In contrast, college alcohol interventions produce larger effect sizes for women relative to men (14). However, mandated female students responded less well to a CDI relative to a BMI (4). Thus, we explored gender patterns on responsiveness to all three interventions.

We addressed three limitations in the literature on mandated alcohol interventions for college students. First, we estimated the effect of providing any alcohol intervention relative to the effects of the sanction experience alone, predicting that all three interventions would augment the effects of being sanctioned and lead to less drinking and fewer alcohol-related problems. Second, we compared a face-to-face BMI with two CDIs developed for college student drinkers. Extrapolating from previous studies (4, 10, 11), we predicted that the BMI would reduce drinking more than either of the CDIs, which would not differ from one another. Third, we determined whether gender moderates intervention response. Based on earlier research (4), we predicted that males would respond better to CDIs than females.

Method

Design

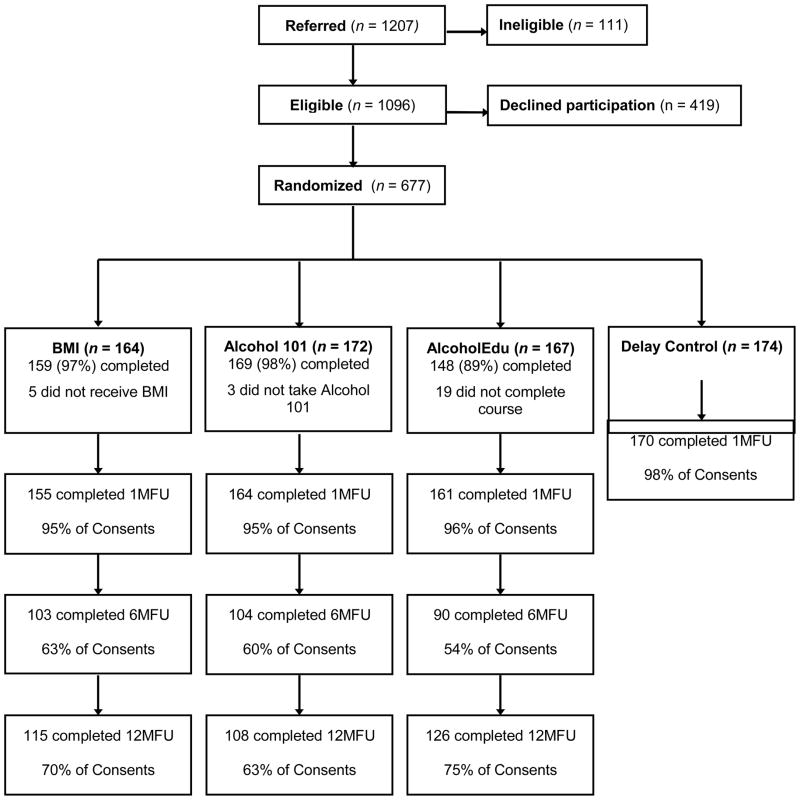

Referred students were assigned randomly by gender to one of four conditions: a BMI, Alcohol 101 Plus™ (101), Alcohol Edu for Sanctions (EDU), or a delayed intervention control (see Figure 1). Students provided data at baseline, 1-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups; students in the delayed control condition received their choice of intervention after the 1-month follow-up and did not provide further data. Ethical requirements constrained the no-intervention control condition to a 1-month delay only. Alcohol consumption, drinking-related problems, and recidivism (i.e., subsequent contacts with the judicial system) served as outcome variables.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram representing participant flow from referral through 12-month follow-ups.

Participants

Participants were 677 students enrolled in a private university who were required to participate in an alcohol program for residence hall alcohol violations. Students were predominantly first and second year students, eligible if they had no previous alcohol violations, their offense was not severe enough to warrant referral to Judicial Affairs, and they reported drinking alcohol in the month before the sanction event. As shown in Figure 1, of the 1207 students referred, 1096 were eligible; of these, 677 (62%) agreed to participate in the study and were randomized to one of the four conditions.

Measures

Participants provided descriptive information regarding gender, age, weight, race/ethnicity, residence, and fraternity or sorority affiliation. For alcohol use measures, a standard drink was defined as 12 oz. of beer; 5 oz. of 12% table wine; 12 oz. of wine cooler; or 1.25 oz. of 80 proof liquor. Baseline covered the month prior to the sanction event, whereas follow-up assessments covered the month prior to the assessment. Two 7-day grids, patterned after the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (15), assessed drinks consumed in a typical week and in the heaviest week in the last month. Participants also reported the typical and maximum number of drinks consumed in a single day and the number of hours spent drinking for each day to estimate typical and peak BAC using the formula: [(drinks/2) * (GC/weight)] − (.016*hours), where (a) drinks = number of standard drinks consumed, (b) hours = number of hours over which the drinks were consumed, (c) weight = weight in pounds, and (d) GC = gender constant (9.0 for females, 7.5 for males) (16). Participants reported frequency of heavy drinking in the previous month, defined as ≥ 5 drinks for men and ≥ 4 drinks for women on a single occasion (17). The Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI) assessed alcohol-related problems (18); a 5-point scale (never to >10 times) indicates how often each of 23 problems occurred in the last 30 days (α = .82).

With participants’ consent, we tracked disciplinary referrals throughout the 12-month follow-up period. A dichotomous variable indicated the occurrence of any additional disciplinary contact.

Procedures

The Institutional Review Board approved all procedures, and we obtained a Certificate of Confidentiality for this study. Residence Life staff referred students who violated campus alcohol policies during three academic years (2005–2008). A Research Assistant (RA) explained to each student that s/he could fulfill the sanction requirement by completing the standard sanction (AlcoholEdu for Sanctions™) or by participating in the study. Participants provided consent, completed the computerized assessment, and received an intervention appointment (for BMI and 101) or login instructions for EDU.

Interventions

The BMI has been shown to be effective with male and female college students (4, 19). Six female psychology graduate students implemented the manualized protocol in a style consistent with motivational interviewing (20). To structure the session, interventionists provided a personalized feedback sheet that summarized (a) drinking patterns (contrasted with gender-specific national and local norms), (b) typical and peak BAC, (c) alcohol-related negative consequences and associated risk behaviors; interventionists also (d) prompted personalized goal setting for risk reduction, and (e) provided tips for safer drinking. BMI sessions averaged 62 minutes (SD = 16.58), ranging from 30 to 148 minutes. Sessions were videotaped for quality assurance. To measure intervention fidelity, we developed a checklist of 46 components prescribed by the manual; two interventionists rated a random 20% of the tapes and counted the number of prescribed components present in each.

Alcohol 101 Plus™ is an interactive CD-ROM program set on a “virtual campus.” Students engage in social decision making at a virtual party, learn about factors affecting their own BAC in a virtual bar, and test their knowledge about alcohol in a game show. Students navigate through the campus locations at their own pace, but were required to spend at least 60 minutes exploring the program. To assess content exposure, an RA reviewed the Campus Map page after each session to determine how many of the 16 major components of the program had been viewed.

Alcohol Edu® for Sanctions consists of five chapters, with quiz questions, interactive exercises, and journaling opportunities. Differentiating itself from the population-based Alcohol Edu® for College, several exercises are tailored for this audience, such as “Blackouts…or Not?” and “Map of US Laws”. Students complete a risk assessment and receive feedback; students whose scores indicate problems are encouraged to consult a health professional. A grade of 70 on a final exam is required to pass. One month after completing the first four chapters, students received email prompts to complete the final chapter, designed to encourage reflection on personal experiences since taking the program, and to review strategies for drinking reduction. The total duration of the on-line course is about two hours.

Follow-ups

RAs sent email reminders for follow-up assessments at 1, 6, and 12 months post-intervention. Completion of the 1-month assessment satisfied the sanction requirement; students earned $25 and $30 (raised to $35 and $40 in the final year) for participating in the 6- and 12-month follow-ups, respectively.

Data Analytic Plan

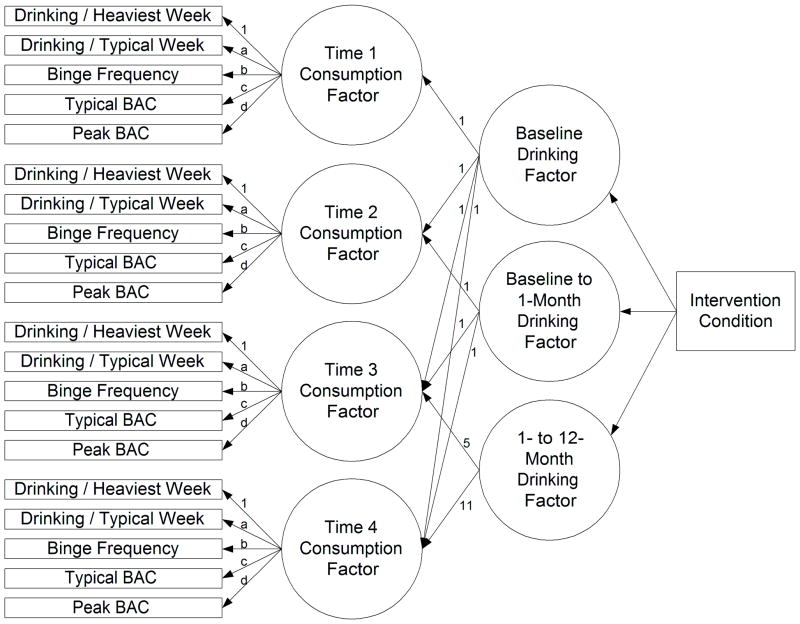

We used analysis of variance, t-test, and χ2 analyses to evaluate group equivalence at baseline and characterize post-intervention satisfaction, attrition, and recidivism across conditions. To test group differences in drinking patterns over time, we fit a piecewise latent growth model (LGM). The LGM simultaneously estimated an optimal consumption factor score at each of the four timepoints, decomposing longitudinal change into three factors: baseline drinking, baseline to 1-month change, and change from 1 to 12 month assessments (see Figure 2). For the consumption LGM, the factors were derived from five drinking measures: standard drinks consumed during the heaviest drinking week, drinks consumed during a typical week, heavy-drinking days, and estimated BACs for typical and heavy drinking occasions. A summary score was derived from the 23 RAPI items at each of the 4 timepoints, from which we estimated the three growth factors.

Figure 2.

Piecewise latent growth model for alcohol consumption.

All models were tested using MPlus 5.21 (21) and were bootstrapped 1,000 times to address skew in the problems and consumption data. Parameters were estimated using all available data, assuming data were missing-at-random.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Sample description

To assess for recruitment bias, we compared consenters (n = 207) and non-consenters (n = 117) from one academic year on age, freshmen status, ethnicity, and on alcohol use (all ps > 0.05). Consenters and non-consenters differed only by gender, χ2(1) = 4.16, p = 0.04, with a greater percentage of female (72%) than male (60%) referred students willing to participate in the study.

Males were overrepresented in the referral pool (67%) and in the sample (64%) relative to the student population (43%). Participants were mostly White (85%), underclassmen (freshmen 67%, sophomores 29%). Mean age was 19 (SD = .71). Conditions did not differ on any demographic variables (all ps >.10). Table 1 illustrates baseline values on the outcome variables; conditions were equivalent on pre-sanction drinking variables (all ps >.10). The modal violation was a single citation of illegal use or possession of alcohol (95%). Baseline assessments occurred a median of 19 days after the event leading to the sanction.

Table 1.

Baseline values for primary outcome variables, for whole sample and separately by gender.

| Whole Sample | Males | Females | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 677 | n = 426 | n = 247 | ||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | t (675) | |

| Drinks per week | 13.36 (9.73) | 14.75 (10.30) | 10.93 (8.11) | 5.01* |

| Drinks per heaviest week | 18.61 (13.04) | 21.09 (13.99) | 14.29 (9.79) | 6.75* |

| Drinks per drinking day | 4.65 (2.54) | 5.13 (2.64) | 3.80 (2.09) | 6.81* |

| Heavy drinking episodes | 5.05 (4.53) | 5.29 (4.43) | 4.63 (4.68) | 1.85 |

| Typical BAC | .082 (.057) | .077 (.052) | .090 (.065) | −2.76* |

| Peak BAC | .158 (.090) | .159 (.089) | .156 (.090) | 0.45 |

| RAPI total score | 4.96 (5.26) | 4.99 (5.32) | 4.90 (5.17) | 0.22 |

Note. All values represent behavior in the month before the sanction. BAC = blood alcohol concentration. RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problems Inventory.

p < .01

Intervention exposure

Students assigned to 101 viewed an average of 12/16 sections (76%; range 19–100%). Nearly all students assigned to EDU logged in (164/167, 98%), 157 (94%) took the final exam, and 153 (92%) achieved a passing score; 110 (66%) completed the final chapter. The BMIs were implemented with fidelity; the interventionists covered an average of 91% of the 46 prescribed sections (range 74%–98%).

Attrition

Of the 677 participants who completed baseline, data were obtained from 96% at 1 month, 58% at 6 months, and 68% at 12 months; 78% completed at least two follow-ups. Neither demographics nor intervention condition predicted attrition (ps > 0.05). Of the pre-sanction drinking variables, only higher peak BAC predicted attrition (p < 0.01).

Recidivism

Only 8% of the sample received one or more disciplinary contacts in the year after the original sanction. The interventions did not differentially impact recidivism rates, χ2 (2) = 1.35, p = 0.51.

Piecewise LGM Evaluation

Alcohol Consumption

The piecewise LGM depicted in Figure 2 was identified by (a) constraining item factor loadings (a–d in the Figure) to equality across the four assessments, (b) constraining item intercepts to equality across the four assessments (but not within an assessment), (c) constraining the means for the four consumption factors to 0, (d) constraining the disturbance for the baseline consumption factor to 0, and (e) allowing correlated errors across time for the same indicators (e.g., peak BAC at times 1 through 4). Drinks per heaviest drinking week was chosen to identify the scale of the factors (i.e., loading fixed to ‘1’), so the unstandardized coefficients can be interpreted in this metric.

The final LGM yielded adequate overall model fit, Model χ2 (429) = 1545.33, p < .001, CFI = .91, RMSEA =.08. The standardized factor loadings for the consumption factors were good: drinks per heaviest week = .93, drinks per typical week = .95, heavy-drinking days = .85, typical BAC = .75, and peak BAC = .68.

Alcohol Problems

We fit a model that included the 3 growth factors using the RAPI score at each of the four timepoints. The residual variance of baseline RAPI scores was fixed to 0 to achieve model identification. Model fit was excellent: Model χ2 (14) = 14.51, p =.41, CFI = .99, RMSEA =.01.

Gender

Standard multi-group analysis determined if final growth model parameters should be independently estimated by gender. At baseline, females drank less than males, χ2(1) = 50.76, p < .001; furthermore, constraining the baseline to 1-month consumption factor and the 1- to 12-month consumption factor to equality between males and females decreased model fit, χ2(2) = 18.86, p < .001. For problems, constraining the growth model to equality across genders did not impair model fit, but we estimated gender-specific growth parameters for both outcomes.

Intervention Efficacy

We first tested the hypotheses that any of the three interventions led to greater reductions in drinking and consequences compared to the delayed-intervention control (Hypothesis 1), focusing on baseline to 1-month change.

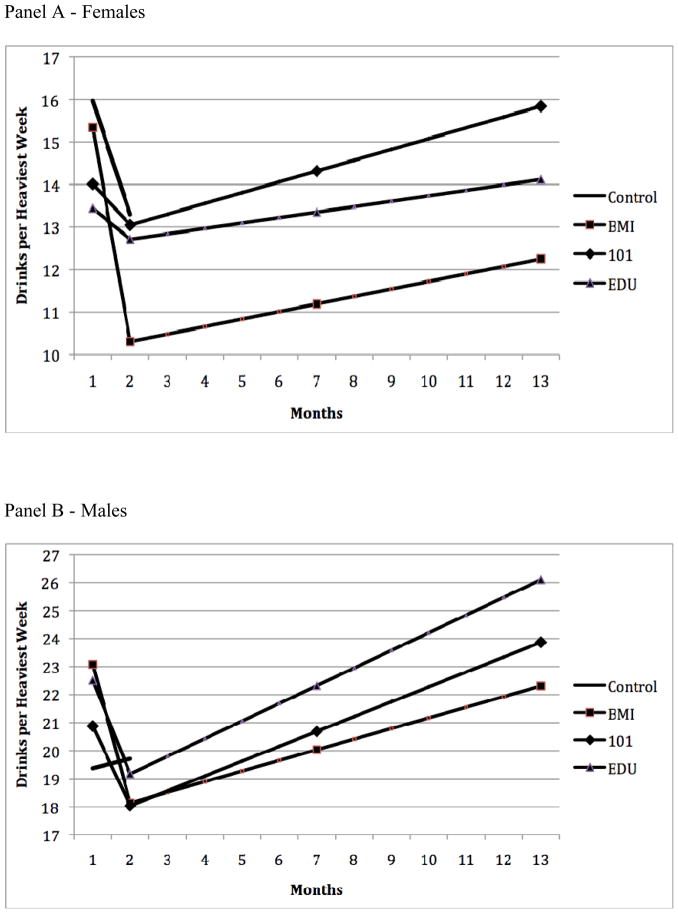

Consumption

Figure 3 depicts the changes in alcohol consumption, separately by gender. Females in the delayed-control condition reduced their drinking equivalent to −2.67 drinks per heaviest week (95% CI [−4.47, −1.13]), which differed from 0 (p < .001). Females receiving interventions also reduced consumption, but none differed from the delayed-control: BMI (M = −5.01, p = .09), 101 (M = −0.97, p = .19), EDU (M = −0.73, p = .12). Conversely, males in the delayed-control condition increased their drinking equivalent to .34 drinks per heaviest week (95% CI [−1.22, 2.06]), which did not differ from 0 (p = .67). However, all intervention conditions yielded greater reductions in males’ drinking relative to the delayed-control: BMI (M = −4.93, p < .001), 101 (M = −2.84, p = .01), and EDU (M = −3.34, p = .01).

Figure 3.

Panel A: Modeled Trajectories from Baseline (month 0), 1-Month Post-Intervention (month 1) through 12-Months Post-Intervention for Females’ Consumption. Panel B: Modeled Trajectories from Baseline (month 0), 1-Month Post-Intervention (month 1) through 12-Months Post-Intervention for Males’ Consumption.

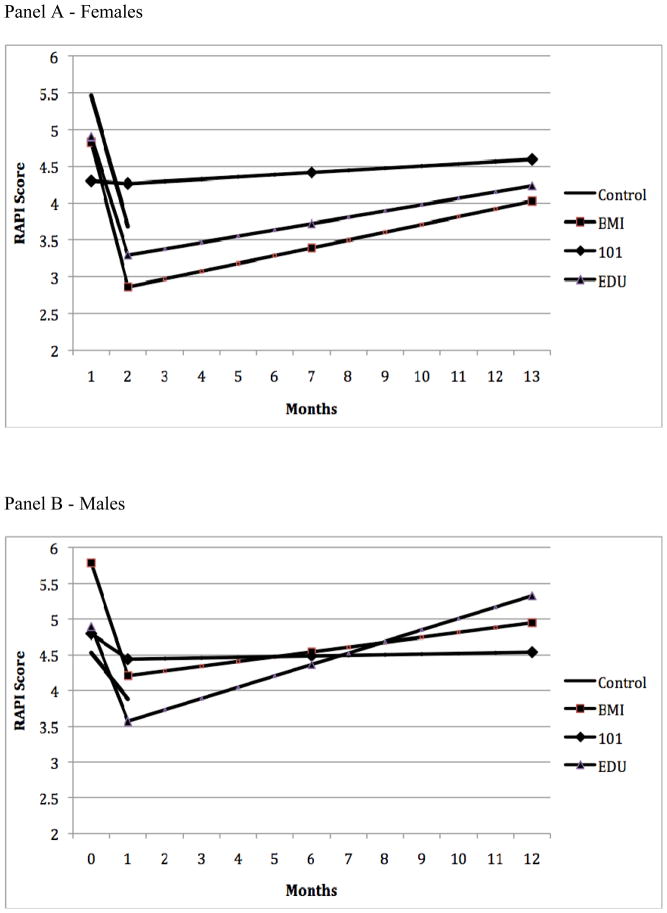

Problems

Figure 4 depicts the changes in alcohol problems, separately by gender. Females in the delayed-control condition decreased RAPI scores from baseline to 1-month (M = −1.77, p < .001, 95% CI [−2.69, −0.98]), a larger reduction than achieved in the 101 condition (M = −0.04, p = .01), but equivalent to the BMI (M = −1.97, p = .77) or EDU (M = −1.61, p = .83) conditions. Thus, females reduced problems in the delay, BMI, and EDU conditions, but not in the 101 condition. Males in the delayed control condition did not reduce RAPI scores from baseline to 1-month (M = −0.65, p = .07, 95% CI [−1.31, 0.10]), nor were there significant intervention effects relative to control: BMI (M = −1.58, p = .17), 101 (M = −0.35, p = .58), and EDU (M = −1.33, p = .30).

Figure 4.

Panel A: Modeled Trajectories from Baseline (month 0), 1-Month Post-Intervention (month 1) through 12-Months Post-Intervention for Females’ Problems. Panel B: Modeled Trajectories from Baseline (month 0), 1-Month Post-Intervention (month 1) through 12-Months Post-Intervention for Males’ Problems. RAPI = Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index.

Comparison of BMI to CDIs

Next we examined whether the BMI led to greater change when compared to the CDIs (Hypothesis 2). Two dummy-coded predictors using BMI as reference were used to predict three growth factors: baseline consumption, baseline to 1-month change, and 1- to 12-month change.

Alcohol Consumption

The three intervention groups were equivalent on baseline consumption within both genders (Table 2, panel a), confirming that randomization produced equivalent groups. For both genders, the BMI condition yielded the greatest improvement from baseline to 1-month (−5.04 and −4.94 drinks per heaviest week, see panel b). However, the BMI (−5.04) produced greater reductions than 101 (−0.97) and EDU (−0.73) for females only; females who received a CDI did not reduce their drinking. Males decreased drinking from baseline to 1-month regardless of condition (BMI = −4.94, 101 = −2.84, EDU = −3.34, all ps < .05).

Table 2.

Gender-Specific Latent Growth Model Results for Consumption, Comparing Computer-Delivered Interventions to the Brief Motivational Intervention.

| Females | Males | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | pa | 95% CI | Estimate | pa | 95% CI | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

|

(a) Baseline consumption | ||||||||

| BMI | 15.34b | 12.81 | 18.81 | 23.08b | 20.25 | 25.87 | ||

| 101 | 14.01b | 0.50 | 11.28 | 16.56 | 20.88b | 0.24 | 18.46 | 23.43 |

| EDU | 13.44b | 0.29 | 11.54 | 15.40 | 22.51b | 0.76 | 20.07 | 25.35 |

|

(b) Baseline to 1-Month Change Factor | ||||||||

| BMI | −5.04b | −7.23 | −2.87 | −4.94b | −7.37 | −2.86 | ||

| 101 | −0.97 | 0.01 | −2.82 | 1.02 | −2.84b | 0.16 | −5.07 | −1.02 |

| EDU | −0.73 | 0.00 | −2.44 | 0.99 | −3.34b | 0.31 | −5.54 | −1.03 |

|

(c) 1-Month to 12-Month Change Factor | ||||||||

| BMI | 0.18 | −0.04 | 0.37 | 0.38b | 0.17 | 0.63 | ||

| 101 | 0.25b | 0.57 | 0.05 | 0.44 | 0.53b | 0.41 | 0.26 | 0.83 |

| EDU | 0.13 | 0.74 | −0.10 | 0.34 | 0.63b | 0.14 | 0.39 | 0.88 |

Note. Baseline consumption metric is drinks per heaviest week. Baseline to 1-Month estimate represents change from baseline value in drinks per heaviest week. 1-Month to 12-Month estimate represents monthly increase in drinks per heaviest week from 1-Month value. BMI = Brief Motivational Intervention. 101 = Alcohol 101 Plus™. EDU = AlcoholEdu for Sanctions™.

for the test of the computer-delivered intervention against the BMI condition.

indicates estimate is significantly different from 0 at p < .05.

Over the next 11 months (Table 2, panel c), males increased their drinking each month by .38, .53, and .63 drinks per heaviest week in the BMI, 101, and EDU conditions, respectively. Females in the 101 condition increased their drinking each month by .25 drinks per heaviest week, but BMI and EDU trajectories did not differ from 0 for females. The 1- to 12-month drinking slopes did not differ across intervention conditions for either gender.

Alcohol Problems

As shown in Table 3 (panel a), baseline problems were equivalent across intervention conditions for both genders. From baseline to 1-month (panel b), decreases in problems were reported by students who received the BMI (−1.97 and −1.58) or EDU (−1.61 and −1.33), but not 101 (−0.04 and −0.35), for females and males, respectively. The 101 condition was less effective than BMI for females (p = .01). In the months following the 1-month assessment (panel c), only females who had a BMI and males who had EDU demonstrated increases in problems over time (i.e., slopes > 0), but the intervention slopes did not differ from each other, for either gender.

Table 3.

Gender-Specific Latent Growth Model Results for Problems, Comparing Computer-Delivered Interventions to the Brief Motivational Intervention.

| Females | Males | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | pa | 95% CI | Estimate | pa | 95% CI | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

|

(a) Baseline Problems | ||||||||

| BMI | 4.83b | 3.70 | 6.26 | 5.79b | 4.72 | 7.06 | ||

| 101 | 4.30b | 0.56 | 3.18 | 5.58 | 4.79b | 0.23 | 3.71 | 5.86 |

| EDU | 4.91b | 0.94 | 3.56 | 6.37 | 4.89 b | 0.25 | 3.96 | 5.93 |

|

(b) Baseline to 1-Month Change Factor | ||||||||

| BMI | −1.97b | −2.97 | −1.10 | −1.58b | −2.83 | −0.49 | ||

| 101 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −1.06 | 1.00 | −0.35 | 0.09 | −1.24 | 0.44 |

| EDU | −1.61b | 0.64 | −2.78 | −0.44 | −1.33b | 0.76 | −2.38 | −0.17 |

|

(c) 1-Month to 12-Month Change Factor | ||||||||

| BMI | 0.11b | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.20 | ||

| 101 | 0.03 | 0.31 | −0.08 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.48 | −0.11 | 0.12 |

| EDU | 0.09 | 0.83 | −0.05 | 0.25 | 0.16b | 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.26 |

Note. Baseline problems metric is the summary score on the Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI). Baseline to 1-Month estimate represents change from baseline RAPI value. 1-Month to 12-Month estimate represents monthly increase RAPI score from 1-Month value. BMI = Brief Motivational Intervention. 101 = Alcohol 101 Plus™. EDU = AlcoholEdu for Sanctions™.

for the test of the computer-delivered intervention against the BMI condition.

indicates estimate is significantly different from 0 at p < .05.

Maintenance of Changes

Figures 3 and 4 represent the modeled trajectories over time, illustrating a gradual return toward the elevated drinking observed at baseline. ANCOVAs comparing the 3 groups on each outcome, controlling for baseline values, failed to reveal group differences at 12 months. However, because the modeling results for the latent consumption variable shown in Figure 3 suggest more favorable outcomes for BMI than either of the CDIs, we conducted two contrasts comparing the BMI to the CDIs on each of the 12-month consumption variables, controlling for baseline values. As with the primary analyses, missing data were assumed MAR, and all results were bootstrapped 1000 times. Relative to EDU, the BMI resulted in fewer drinks per heaviest week for both male (b = 5.14, p = .04) and female students (b = 3.88, p = .02). Relative to 101, the BMI resulted in fewer drinks per heaviest week (b = 4.03, p = .01), drinks per typical week (b = 2.64, p = .02), and peak BAC (b = .04, p = .05) for female students only. Thus, at 12 months, differences between BMI and CDIs emerged only on a subset of the consumption variables, primarily for female students, but always in favor of BMIs.

We then characterized how long the intervention effects lasted before behavior was indistinguishable from baseline drinking. We assumed that the baseline consumption and problems estimates represented population values and that any predicted score falling in the baseline 95% CIs (see Tables 2 and 3) represented an equivalent level of consumption and problems, respectively. Then, using the estimated model parameters for each group, we calculated how many months had to pass before the estimated consumption and problems were equivalent to baseline.

After a BMI, males returned to baseline consumption after 6.49 months and baseline problems after 8.69 months. Females in the BMI condition were still lower than baseline consumption at 12 months, but returned to baseline problems by 8.89 months. After 101, males returned to baseline consumption after only 1.79 months, but males’ problems, and females’ consumption and problems never differed from baseline. After EDU, males returned to baseline consumption after 2.43 months and baseline problems after 3.43 months. Females in the EDU condition returned to baseline problems after 4.07 months but their consumption never differed from baseline.

Discussion

We compared three brief interventions for college students sanctioned for alcohol violations. Male and female students responded differently to both sanction process and the mandated interventions. Three primary findings emerged.

First, change consistent with a sanction effect was observed for female, but not for male, students. Even before receiving an intervention, females in the delayed-control condition reduced both consumption and problems. Explanations include reactivity to alcohol assessments, which has been documented with young adult drinkers (19, 22), and naturally occurring changes in drinking over the course of the semester. Alternatively, because an event triggered entry into the study, female students may have responded to the experience of being sanctioned with self-initiated change, consistent with previous studies that documented change from pre- to post-sanction event and before baseline assessment (4, 9) and after baseline in waitlist conditions (8, 23). It is unclear why change in the absence of an intervention was observed only with female and not male students; however, this finding corroborates research with adult women showing equivalent response to no/minimal interventions and brief interventions (13). Female students may initiate change with minimal prompting because of greater perceived vulnerability to alcohol-related consequences, the inconsistency of risky drinking with gender role expectations, or because female students enjoy greater freedom to modify drinking without violating social norms and expectations (24, 25).

In light of improvement reported by controls, interventions did not improve outcomes for female students relative to no intervention. However, relative to baseline, participation in a BMI resulted in significant reductions in both consumption and problems; participation in EDU resulted in reduction in problems only; and participation in 101 resulted in no change for females. Indeed, 101 was less effective than no intervention in reducing alcohol-related problems. In contrast, male students reported short-term improvements after all of the alcohol-focused interventions. Thus, our first hypothesis – that receiving a mandated alcohol intervention would lead to more change than the sanction process alone – was supported for males only.

Second, BMIs produced greater change than either CDI for females only. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, female students drank less after a BMI than after either CDI, and they reported fewer problems after a BMI than after 101. The BMI also suppressed drinking and problems for longer than either CDI. Thus, for mandated female students, stronger and longer lasting risk reduction follows BMIs.

In contrast, the male students responded equally well to all three interventions initially, reducing both consumption and problems relative to baseline. Supporting Hypothesis 3, mode of intervention delivery is less important in the short-term for males so CDIs are efficacious risk reduction options for male mandated students. However, males’ drinking increased over the follow-up period regardless of intervention, indicating that effects on consumption are short-lived. Thus, maintenance of initial risk reduction warrants more attention. Young men experience unique pressures related to gender roles and social norms that promote risky drinking (26) and empowering males to make safer choices remains a challenge.

Third, BMIs produced stronger effects relative to CDIs, replicating outcomes found in previous studies comparing BMI to 101 (4) and BMI to EDU (27). Taken together, the available data suggest a small, but consistent advantage of face-to-face BMIs for both male and female mandated students.

We acknowledge limitations of the study. First, the sanction events were relatively minor infractions (none involved serious behavior problems or extreme intoxication), which may have minimized the self-perceived need for change among the male students (9). These results may not generalize to students with more serious alcohol infractions. Second, participants were predominately white and from the northeastern states; replication with more diverse samples is encouraged. Third, retrospective self-reports may be subject to recall bias; integration of experience sampling methods could minimize this concern. Fourth, attrition at the 6- and 12-month assessments may introduce bias in the outcome analyses. However, our data analytic strategy used all available data to minimize the effects of attrition. Finally, the delayed-intervention control condition provided one-month follow-up data only, limiting our ability to address the longer-term effects of intervention versus no intervention.

The results of this study lead to three conclusions with implications for the implementation of mandated interventions. First, enforcing alcohol policies can reduce risky consumption and alcohol-related consequences in the short-term. The interventions were evaluated under conditions similar to those used in real world and each produce significant improvement in at least some students. Second, mandated interventions provide the greatest benefit for male students who are unlikely to change in the absence of an intervention. Third, female students benefit more from face-to-face BMIs than from a CDI. Future research needs to focus on ways to maintain short-term gains and understanding gender-specific responses to alcohol prevention interventions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carrie Luteran, the SURE Project staff, and the staff at Office of Residence Life for their contributions to this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Declaration: This project was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants R01-AA12518 and K02-AA15574 to Kate B. Carey. The authors have received no funding from the tobacco, alcohol, pharmaceutical or gaming industries.

Contributor Information

Kate B. Carey, Center for Health and Behavior, Syracuse University

Michael P. Carey, Center for Health and Behavior, Syracuse University

James M. Henson, Old Dominion University

Stephen A. Maisto, Center for Health and Behavior, Syracuse University

Kelly S. DeMartini, Center for Health and Behavior, Syracuse University

References

- 1.Office of Applied Studies. Underage Alcohol Use among Full-Time College Students. The NSDUH Report [serial on the Internet] 2006;(31) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. Efficacy of counselor vs. computer-delivered intervention with mandated college students. Addict Behav. 2007;32(11):2529–48. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borsari B, Carey KB. Two brief alcohol interventions for mandated college students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19(3):296–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey KB, Henson JM, Carey MP, Maisto SA. Computer versus in-person intervention for students violating campus alcohol policy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(1):74–87. doi: 10.1037/a0014281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doumas DM, McKinley LL, Book P. Evaluation of two Web-based alcohol interventions for mandated college students. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(1):65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White HR, Morgan TJ, Pugh LA, Celinska K, LaBouvie EW, Pandina RJ. Evaluating two brief substance-use interventions for mandated college students. J Stud Alc. 2006;67(2):309–17. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White HR, Mun EY, Pugh L, Morgan TJ. Long-term effects of brief substance use interventions for mandated college students: sleeper effects of an in-person personal feedback intervention. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(8):1380–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fromme K, Corbin W. Prevention of heavy drinking and associated negative consequences among mandated and voluntary college students. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004 Dec;72(6):1038–49. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan TJ, White HR, Mun EY. Changes in drinking before a mandated brief intervention with college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(2):286–90. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott JC, Carey KB, Bolles JR. Computer-based interventions for college drinking: A qualitative review. Addict Behav. 2008;33:994–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Elliott JC, Bolles JR, Carey MP. Computer-delivered interventions to reduce college student drinking: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2009;104:1807–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaner ELC, Heather N, McNamee P, Bond S. Promoting brief alcohol interventions by nurses in primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51:277–84. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang G. Brief interventions for problem drinking and women. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carey KB, Henson JM, Carey MP, Maisto SA. Which heavy drinking college students benefit from a brief motivational intervention? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(4):663–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self administration of alcohol. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews DB, Miller WR. Estimating blood alcohol concentration: two computer programs and their applications in therapy and research. Addict Behav. 1979;4(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wechsler H, Davenport A, Dowdall G, Moeykens B, Rimm EB. A gender-specific measure of binge drinking among college students. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(7):982–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 1989;50:30–7. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Henson JM. Brief motivational interventions for heavy college drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(5):943–54. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller WR, Rollnick SR. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muthen B, Muthen L. MPlus. 5.21. Los Angeles: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR, Field CA, Jouriles EN. Dismantling motivational interviewing and feedback for college drinkers: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(1):64–73. doi: 10.1037/a0014472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White HR, Mun EY, Morgan TJ. Do brief personalized feedback interventions work for mandated students or is it just getting caught that works? Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22(1):107–16. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landrine H, Bardwell S, Dean T. Gender expectations for alcohol use: A study of the significance of the masculine role. Sex Roles. 1988;19(11/12):703–712. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suls J, Green P. Pluralistic ignorance and college student perceptions of gender-specific alcohol norms. Health Psych. 2003;22(5):479–486. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Courtenay WH. Key determinants of the health and well-being of men and boys. Int J Men’s Health. 2003;2(1):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amaro H, Ahl M, Matsumoto A, Prado G, Mule C, Kemmemer A, et al. Trial of the university assistance program for alcohol use among mandated students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009 Jul;(16):45–56. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]