Abstract

There is comorbidity and a possible genetic connection between Bipolar disease (BP) and panic disorder (PD). Genes may exist that increase risk to both PD and BP. We explored this possibility using data from a linkage study of PD (120 multiplex families; 37 had ≥1 BP member). We calculated 2-point lodscores maximized over male and female recombination fractions by classifying individuals with PD and/or BP as affected (PD +BP). Additionally, to shed light on possible heterogeneity, we examine the pedigrees containing a bipolar member (BP+) separately from those that do not (BP−), using a Predivided-Sample Test (PST). Linkage evidence for common genes for PD +BP was obtained on chromosomes 2 (lodscore =4.6) and chromosome 12 (lodscore =3.6). These locations had already been implicated using a PD-only diagnosis, although at both locations this was larger when a joint PD +BP diagnosis was used. Examining the BP+ families and BP− families separately indicates that both BP+ and BP− pedigrees are contributing to the peaks on chromosomes 2 and 12. However, the PST indicates different evidence of linkage is obtained from BP+ and BP− pedigrees on chromosome 13. Our findings are consistent with risk loci for the combined PD +BP phenotype on chromosomes 2 and 12. We also obtained evidence of heterogeneity on chromosome 13. The regions on chromosomes 12 and 13 identified here have previously been implicated as regions of interest for multiple psychiatric disorders, including BP.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, panic disorder, linkage, phenotype, genome scan, genetic heterogeneity

INTRODUCTION

Several clinical and epidemiological studies have noted a high comorbidity between panic disorder (PD) and bipolar disorder (BP) [Savino et al., 1993; Young et al., 1993; Kessler et al., 1994; Chen and Dilsaver, 1995; Kessler, 1995; Szadoczky et al., 1998; Goodwin and Hoven, 2002]. From 10% to 60% of patients with BP also have PD. Conversely, studies investigating PD patients found that 13–23% of patients with PD also have BP [Savino et al., 1993; Bowen et al., 1994]. Both PD and BP are relatively common diseases, with a lifetime prevalence of 1.6–2.2% for PD [Weissman et al., 1997; see also Grant et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 2005] and about 1% for BP [Bebbington and Ramana 1995]. If there were no association between PD and BP, then the expected co-occurrence would be the product of each prevalence rate: 0.016 to 0.022%. The observed comorbidity exceeds this value several-fold. Furthermore, the co-occurrence of PD and BP is seen not only in patients but also in their families. While it is commonly accepted that family members of BP probands are at higher risk for BP, it is also striking that in those family members PD is seen more often than expected from the general population rate of PD [MacKinnon et al., 1997; Edmonds et al., 1998].

In this article, we use linkage analysis, classifying all individuals with either PD and/or BP as affected (PD +BP), in order to identify regions likely to contain joint PD and BP risk loci. We utilize a unique sample of 120 families ascertained for a PD genetic study. This sample has been described elsewhere [Fyer and Weissman, 1999; Hamilton et al., 2003; Fyer et al., 2006]. Thirty-seven of these families had at least one family member affected with BP. We analyzed the families allowing for the possibility that male and female recombination fractions may not be equal. Then, we separated families into those with at least one member affected with BP (BP+) versus those with no BP members (BP−) and analyzed each group separately to look for evidence of heterogeneity. The significance of this analysis was evaluated using the Predivided-Sample Test (PST)

SAMPLE AND METHODS

Families

Family ascertainment, selection, and clinical methods have been described in detail elsewhere [Fyer and Weissman, 1999]. For the present study, all subjects who had been flagged for bipolar disorder or had been diagnosed with bipolar I, bipolar II, or cyclothymia by direct interview were re-best estimated for bipolar disorder. Here we used a broad definition as our diagnosis of PD including PD definite + probable + possible + any as affected (referred to as “panic broad” category previously [Knowles et al., 1998; Fyer and Weissman, 1999; Hamilton et al., 2003; Fyer et al., 2006]).

A total of 120 families were collected with at least two family members affected with PD. Thirty-seven of those families had at least one member affected with BP (BP+ families). Eighty-three families did not have any member with BP (BP− families). These 120 families consist of 1,591 family members. Seven hundred eighty-seven family members were affected either with PD and/or BP (average 6.5 affected family members per family). Seven hundred thirty-nine family members had PD only and 22 members had BP only. Twenty-six family members had both, PD and BP.

Genotyping

CIDR performed a complete genome scan (http://www.cidr.jhmi.edu). The CIDR marker set consisted of 384 simple tandem repeats (mostly tri- and tetra-nucleotides), at an average spacing of 9 cM, with no gap greater than 20 cM (http://www.cidr.jhmi.edu/download/CIDRmarkers.txt). Here we present an analysis of the 371 autosomal markers from this set. Genotypes were available on 992 family members.

Linkage Analysis

We analyzed PD +BP using parametric lodscores because of the high power of parametric methods when analyzing large pedigrees with many affected members. We calculated 2-point lodscores allowing for independent male and female recombination fractions θ =(θm, θf) using KELVIN [Huang et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007]. We allow for independent male and female recombination fractions for several reasons: (1) because gender-dependent recombination rates can vary drastically across the genome [Mohrenweiser et al., 1998; Lynn et al., 2000] with predictable consequences for linkage analysis [Daw et al., 2000]; (2) because gender-specific phenomena are strongly suspected in PD as well as in BP, and allowing for sex-specific recombination may increase power in cases where sex-specific effects are present; and (3) because this technique has previously proven useful in the search for PD susceptibility loci in this sample [Fyer et al., 2006].

The genetic parameters for the analyses were guided by the results from our previous segregation analysis of PD [Vieland et al., 1993]. We used a disease gene frequency of 0.01 under an assumed dominant model and of 0.2 under a recessive model. The penetrance for both models was set to 0.5 and the phenocopy rate was 0.01. We are aware that these parameters might be only approximations of the unknown genetic model for PD +BP, but extensive research has shown that lodscores are relatively robust to misspecification of the penetrance and gene frequency [Hodge et al., 1997; Pal et al., 2001], as long as the “mode of inheritance” (MOI, i.e., dominant or recessive) at the locus being examined is correct. Therefore, we performed our analyses twice, once assuming a dominant MOI and once assuming a recessive MOI, as suggested by Hodge et al. [1997].

Next, we look for possible evidence of heterogeneity between the BP+ families and the BP− families. First, we computed lodscores for these pedigrees separately. Then, we computed a Predivided Sample Test (PST) for heterogeneity [Morton, 1956; Hodge et al., 1983; Ott, 1983]. The PST statistic follows an approximately χ2 distribution with one degree of freedom (as long as the max lodscore does not occur at θ =0).

Computing lodscores under two genetic models and maximizing over separate male and female recombination fractions alters the nominal significance level of a lodscore of 3. However, corrections for maximization over these two elements are well characterized. Allowing for independent male/female recombination fractions is accomplished by raising the threshold level from a lodscore of 3 to 3.3 [Ott, 1999]. Similarly, computing a lodscore under both a dominant and recessive genetic model is accommodated by raising the significance criteria by 0.3 [Hodge et al., 1997]. Therefore, we use 3.6 as our criteria for “significance.” This criteria was not further adjusted for the testing of multiple markers. Lodscores of the PD-only analysis are presented in the discussion section for completeness and comparison purposes. We refer to our previous publication for a discussion of the significance of lodscores observed using the PD-only diagnosis [Fyer et al., 2006]. We judge the significance of the separate analyses of the BP+ and BP− families through the use of the PST. However, PST is a test for heterogeneity and not a test for linkage per se. That is, it can be significant even when the individual lodscores are not large enough to establish linkage in either dataset, nevertheless indicating heterogeneity between the datasets. Nominal per-marker P-values of the PST are presented.

The two-stage analysis method used here—analyzing the data with a combined phenotype and then testing for heterogeneity with the PST—shares some resemblance to using logistic regression to model the probability of allele sharing among relative pairs as a function of covariate information as suggested in Rice [1997] and elsewhere [Devlin et al., 2002; Glidden et al., 2003; Tsai and Weeks, 2006]. However, our desire to utilize extended pedigrees as a whole precludes the use of these covariate analysis methods. Furthermore, the hypothesis being examined in our lodscore analysis is a test for linkage assuming homogeneity rather than a test of linkage in the presence of heterogeneity as in Rice [1997].

RESULTS

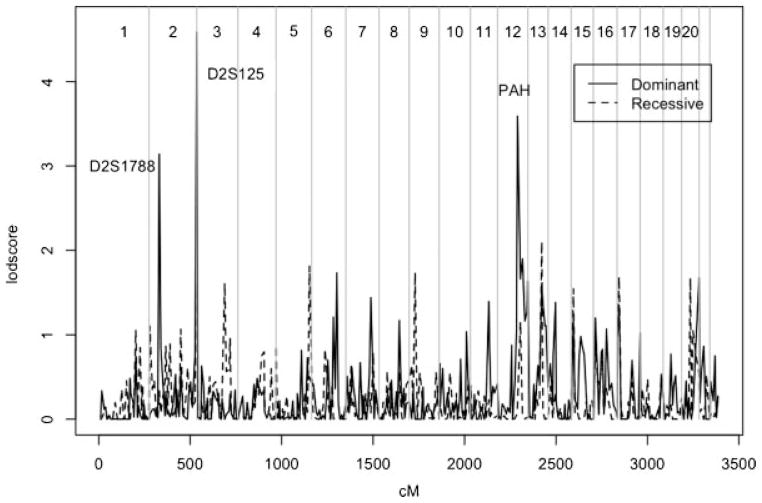

Figure 1 shows the results of the genome scan of PD +BP in all 120 families. The highest lodscores occurred on chromosome 2 and 12 under a dominant model and on chromosome 13 under a recessive model. The highest lodscore of 4.6 occurred on chromosome 2q at marker D2S125 (261 cM) under a dominant model with maximizing θ =(θm, θf) = (0.12, 0.32). On chromosome 12, the highest lodscore was 3.6 at marker PAH (109 cM) at θ =(0.15, 0.33). Lodscores on chromosome 12 are above 1 for a genetic distance of over 62 cM, from D12S1300 to 12qtel. An additional marker on chromosome 2p had a lodscore which exceeded 3, but did not meet our more stringent significance criteria: a lodscore of 3.1 was observed at D2S1788 under a dominant model at θ =(0.50, 0.25). The highest lodscore under an assumed recessive model occurred at marker D13S793 (76 cM) with a value of 2.1 at θ =(0.5, 0.08).

FIG 1.

Genome Scan of PD + BP.

Table I includes a summary of the results for all 120 pedigrees and the separate BP+ and BP− analyses. Nominally significant evidence of heterogeneity was obtained at a single locus: (P =0.004) on chromosome 13 at D13S779 (83 cM). A lodscore of 2.4 was observed in the 37 BP+ families. This is substantially higher than the lodscore of 1.4 observed at D13S799 when the 120 families were analyzed together, suggesting that the BP+ families may be genetically different than the BP− families at D13S799. However, this score is not significant if we were to perform a Bonferroni correction to control the type 1 error rate for the entire set of markers (P <0.0001).

TABLE I.

Analysis of PD +BP in all 120 Families, 37 BP+ Families, and 83 BP− Families

| Marker-MOI | All families |

BP+ families |

BP− familiesa |

PST χ2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lod | (θm,θf) | lod | (θm,θf) | lod | (θm,θf) | ||

| D2S125-D | 4.6 | (0.12, 0.32) | 1.9 | (0.22, 0.22) | 3.5 | (0.06, 0.36) | 3.5ns |

| PAH-D | 3.6 | (0.15, 0.33) | 2.6 | (0.05, 0.50) | 1.5 | (0.24, 0.31) | 2.8ns |

| D2S1788-D | 3.1 | (0.50, 0.25) | 1.1 | (0.50, 0.23) | 2.0 | (0.50, 0.26) | 0.0ns |

| D13S793-R | 2.1 | (0.50, 0.08) | 0.3 | (0.30, 0.22) | 2.5 | (0.50, 0.00) | 3.3ns |

| D13S779-D | 1.4 | (0.25, 0.30) | 2.4 | (0.01, 0.32) | 0.8 | (0.49, 0.26) | 8.1* |

| D20S477-R | 1.7 | (0.14, 0.50) | 2.2 | (0.02, 0.46) | 0.2 | (0.25, 0.50) | 1.1ns |

| D5S211-R | 1.8 | (0.15, 0.50) | 0.0 | (0.33, 0.50) | 2.2 | (0.10, 0.50) | 1.7ns |

Lodscores are maximized over mode of inheritance (MOI) and independent male/female recombination fractions. The upper section displays markers with the highest lodscores in the total sample, the lower section displays results for markers with the largest lodscores in the BP+ and BP− groups (apart from markers already noted). PST = predivided sample test statistic;

P <0.005;

nsP >0.05.

For the BP− families, the analysis of PD +BP is equivalent to analysis of a PD-only diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we analyzed our families with multiple occurrence of PD and found evidence for linkage on chromosome 2p (D2S1788), 2q (D2S125), 9p (D9S925), 12 (PAH), and 15q (near GABA-A receptor subunit genes) [Fyer et al., 2006]. Guided by clinical observation of greater than expected co-occurrence of PD and BP, we decided to define the phenotype more broadly, to include not only PD but also BP as affected.

Using a PD +BP affectedness model we found evidence for linkage on chromosome 2q and 12 with lodscores of 4.6 and 3.6, respectively. Including those with BP as affected increased lodscores from their values when PD-only was used as the diagnosis. Using the same genetic parameters but classifying only family members with PD (and not BP) as affected, the corresponding lodscores were 3.9 at D2S125 and 2.8 at PAH. The lodscore of 3.1 obtained at marker D2S1788 on chromosome 2p is less than the lodscore of 3.3 observed in the PD-only analysis.

Imprinting or parent-of-origin effects have been suggested as a possibility in BP inheritance [Stine et al., 1995; Kornberg et al., 2000; Borglum et al., 2003]. At D2S125, we observed a difference of 0.7 lodscore units when we maximized the lodscore over θm and θf, versus maximizing the lodscore over equal θ (lodscore of 4.6 under independent recombination and 3.9 if the rates are held equal). However, the map in this region is not concordant with the values at which the lodscore maximizes. That is, the recombination rate on chromosome 2 in the region of this marker (near the telomere) is larger in males than in females, yet the lodscore maximizes at θf > θm. In contrast, the lodscores obtained at PAH were concordant with the greater rate of female than male recombination in the region. The discordance of the maximizing male and female recombination rates observed at D2S125 is consistent with heterogeneity where some fraction of the families show genetic imprinting [Greenberg et al., 2002].

On chromosome 9, where we previously reported high lodscores in the PD-only analysis [Fyer et al., 2006], the lodscores were lower in the PD +BP analysis. However, the highest PD-only lodscores were observed under a narrower PD diagnostic scheme (intermediate PD) than we used in the PD +BP analysis (PD broad and/or BP). The difference in the lodscore is attributable more to the change in PD category than to the inclusion of BP in the affectedness model, with a lodscore of 1.7 under “PD broad-only” and to 2.0 under “PD broad +BP” at marker D9S925. In contrast to the PD-only analysis of Fyer et al. [2006], there was no support for linkage between PD +BP and any location on chromosome 15.

In our previous PD-only analysis we had observed substantial evidence of heterogeneity. We therefore postulated that PD with BP might be genetically different from PD without BP. We have identified a region on chromosome 13, where BP+ families and BP− families yielded substantially different evidence for linkage, as demonstrated by the PST. Under a dominant MOI, only BP+ families showed evidence for linkage at D13S779, yielding a lod-score of 2.4. At the neighboring marker, D13S1793, we observed a lodscore of 2.5 under a recessive model in the BP− pedigrees. This chromosomal area is identical to the one where we had obtained high lodscores under a different classification scheme that included PD and a “syndrome” that comprised bladder/kidney problems, headache, thyroid problems and/or mitral valve prolapse [Weissman et al., 2000; Hamilton et al., 2003; Talati et al., 2008]. However, differential linkage on chromosome 13 cannot be explained as a correlation between a family’s BP+/− status and the syndrome phenotype; the percentage of syndrome individuals is nearly identical in these two groups (percentage =33.8% both BP+ and BP− families, P =0.98).

In conclusion, our results point to linkage of a PD +BP phenotype to chromosome 2q and chromosome 12 and indicate a region of heterogeneity on chromosome 13. The region implicated in PD +BP susceptibility on chromosome 12 (12q23) has been noted in multiple linkage studies of bipolar and unipolar disorder [Dawson et al., 1995; Ewald et al., 1998; Morissette et al., 1999; Maziade et al., 2001; Abkevich et al., 2003; Curtis et al., 2003; Ekholm et al., 2003; Zubenko et al., 2003; Green et al., 2005]. Furthermore, a SNP in this region has been associated with severity scores on a severity scale of panic and agoraphobia symptoms [Erhardt et al., 2007]. Similarly, the region on chromosome 13 where we found evidence of heterogeneity has been implicated in multiple studies of both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [Lin et al., 1997; Blouin et al., 1998; Shaw et al., 1998; Brzustowicz et al., 1999; Detera-Wadleigh et al., 1999; Kelsoe et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2001; Chumakov et al., 2002; Faraone et al., 2002; Hattori et al., 2003; Mulle et al., 2005; Cheng et al., 2006]. The most studied candidate locus in this region is G72(DAOA)/G30 [Hattori et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2004; Korostishevsky et al., 2004; Schumacher et al., 2004; Fallin et al., 2005; Detera-Wadleigh and McMahon, 2006; Williams et al., 2006; Li and He, 2007; Kvajo et al., 2008; Prata et al., 2008]. While the location of G72(DAOA)/G30 is not well characterized according to the Marshfield map (90–93 cM), it is undoubtedly close to D13S779 (83 cM). A 2 lod-unit support interval around the peak lodscore of 2.4 observed in the BP+ families at D13S799 indicates that sex-averaged θ values between 0.13 and 0.41 are plausible. This recombination rate is greater than expected if G72(DAOA)/G30 was responsible for the peak at D13S779 (given the 7–10 cM distance between the two). However, misspecification of the genetic model (such as residual heterogeneity within the BP+ families) could easily cause an inflated θ estimate. Therefore, we can not rule out the possibility that G72(DAOA)/G30 plays a role in the heterogeneity implied by the PST at D13S799. This region has also been noted in a linkage study of recurrent major depressive disorder [McGuffin et al., 2005]. While a complete examination of the possible genetic overlap between BP, PD, and major depressive disorder (MDD) is beyond the scope of this article (given our prior hypothesis of the overlapping genetic diathesis of BP and PD) it would be unreasonable to assume that this region did not play a role in the development of MDD. In fact, MDD is quite prevalent in this sample, and in a prior (unpublished) 2-point sex-averaged lodscore analysis of this data using major depressive disorder as the outcome variable, the largest lodscore of 2.3 occurred at D13S793 (76 cm). Meta-analyses of BP and schizophrenia linkage scans have obtained conflicting results, with one finding the strongest evidence of linkage at this region [Badner and Gershon, 2002] and others failing to find linkage to chromosome 13 [Levinson et al., 2003; Segurado et al., 2003; McQueen et al., 2005]. Nevertheless, it is hard to dismiss the convergence of linkage findings on chromosome 13 for several different psychiatric diseases as false positives.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant Nos. MH2874 (M.M.W.), MH35792 (D.F.K., A.J.F.), MH48858 (S.E.H.), MH076100 (M.W.L.)). Genotyping services were provided to J.A.K. by the Center for Inherited Disease Research, which is fully funded through Federal Contract N01-HG-65403 from the National Institutes of Health to The Johns Hopkins University.

Footnotes

Dr. Logue, Dr. Durner, Dr. Heiman, Dr. Hodge, Dr. Hamilton, and Dr. Fyer report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest. In the past 5 years Dr. Weissman had an investigator-initiated grant from Eli Lilly and GlaxoSmithKline and has been a scientific advisor to Lilly. These grants and consulting have terminated. She currently receives research funds from NIMH, NARSAD. She receives royalties from books or assessments from the American Psychiatric Association, Perseus Press, Oxford Press, and Multihealth Systems.

References

- Abkevich V, Camp NJ, Hensel CH, Neff CD, Russell DL, Hughes DC, Plenk AM, Lowry MR, Richards RL, Carter C, Frech GC, Stone S, Rowe K, Chau CA, Cortado K, Hunt A, Luce K, O’Neil G, Poarch J, Potter J, Poulsen GH, Saxton H, Bernat-Sestak M, Thompson V, Gutin A, Skolnick MH, Shattuck D, Cannon-Albright L. Predisposition locus for major depression at chromosome 12q22-12q23.2. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:1271–1281. doi: 10.1086/379978. Epub 2003 Nov 1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badner JA, Gershon ES. Regional meta-analysis of published data supports linkage of autism with markers on chromosome 7. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:56–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington P, Ramana R. The epidemiology of bipolar affective disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1995;30:279–292. doi: 10.1007/BF00805795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin JL, Dombroski BA, Nath SK, Lasseter VK, Wolyniec PS, Nestadt G, Thornquist M, Ullrich G, McGrath J, Kasch L, Lamacz M, Thomas MG, Gehrig C, Radhakrishna U, Snyder SE, Balk KG, Neufeld K, Swartz KL, DeMarchi N, Papadimitriou GN, Dikeos DG, Stefanis CN, Chakravarti A, Childs B, Housman DE, Kazazian HH, Antonarakis SE, Pulver AE. Schizophrenia susceptibility loci on chromosomes 13q32 and 8p21. Nat Genet. 1998;20:70–73. doi: 10.1038/1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borglum AD, Kirov G, Craddock N, Mors O, Muir W, Murray V, McKee I, Collier DA, Ewald H, Owen MJ, Blackwood D, Kruse TA. Possible parent-of-origin effect of Dopa decarboxylase in susceptibility to bipolar affective disorder. Am J Med Genet Part B. 2003;117B:18–22. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.10030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen R, South M, Hawkes J. Mood swings in patients with panic disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 1994;39:91–94. doi: 10.1177/070674379403900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzustowicz LM, Honer WG, Chow EW, Little D, Hogan J, Hodgkinson K, Bassett AS. Linkage of familial schizophrenia to chromosome 13q32. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1096–1103. doi: 10.1086/302579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Dilsaver SC. Comorbidity of panic disorder in bipolar illness: Evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:280–282. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YS, Akula N, Detera-Wadleigh SD, Schulze TG, Thomas J, Potash JB, DePaulo JR, McInnis MG, Cox NJ, McMahon FJ. Findings in an independent sample support an association between bipolar affective disorder and the G72/G30 locus on chromosome 13q33. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:87–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001453. image 85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng R, Juo SH, Loth JE, Nee J, Iossifov I, Blumenthal R, Sharpe L, Kanyas K, Lerer B, Lilliston B, Smith M, Trautman K, Gilliam TC, Endicott J, Baron M. Genome-wide linkage scan in a large bipolar disorder sample from the National Institute of Mental Health genetics initiative suggests putative loci for bipolar disorder, psychosis, suicide, and panic disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:252–260. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumakov I, Blumenfeld M, Guerassimenko O, Cavarec L, Palicio M, Abderrahim H, Bougueleret L, Barry C, Tanaka H, La Rosa P, Puech A, Tahri N, Cohen-Akenine A, Delabrosse S, Lissarrague S, Picard FP, Maurice K, Essioux L, Millasseau P, Grel P, Debailleul V, Simon AM, Caterina D, Dufaure I, Malekzadeh K, Belova M, Luan JJ, Bouillot M, Sambucy JL, Primas G, Saumier M, Boubkiri N, Martin-Saumier S, Nasroune M, Peixoto H, Delaye A, Pinchot V, Bastucci M, Guillou S, Chevillon M, Sainz-Fuertes R, Meguenni S, Aurich-Costa J, Cherif D, Gimalac A, Van Duijn C, Gauvreau D, Ouellette G, Fortier I, Raelson J, Sherbatich T, Riazanskaia N, Rogaev E, Raeymaekers P, Aerssens J, Konings F, Luyten W, Macciardi F, Sham PC, Straub RE, Weinberger DR, Cohen N, Cohen D. Genetic and physiological data implicating the new human gene G72 and the gene for D-amino acid oxidase in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13675–13680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182412499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis D, Kalsi G, Brynjolfsson J, McInnis M, O’Neill J, Smyth C, Moloney E, Murphy P, McQuillin A, Petursson H, Gurling H. Genome scan of pedigrees multiply affected with bipolar disorder provides further support for the presence of a susceptibility locus on chromosome 12q23-q24, and suggests the presence of additional loci on 1p and 1q. Psychiatr Genet. 2003;13:77–84. doi: 10.1097/01.ypg.0000056684.89558.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw EW, Thompson EA, Wijsman EM. Bias in multipoint linkage analysis arising from map misspecification. Genet Epidemiol. 2000;19:366–380. doi: 10.1002/1098-2272(200012)19:4<366::AID-GEPI8>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson E, Parfitt E, Roberts Q, Daniels J, Lim L, Sham P, Nöthen M, Propping P, Lanczik M, Maier W, Reuner U, Weissenbach J, Gill M, Powell J, McGuffin P, Owen M, Craddock N. Linkage studies of bipolar disorder in the region of the Darier’s disease gene on chromosome 12q23-24.1. Am J Med Genet. 1995;60:94–102. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detera-Wadleigh SD, McMahon FJ. G72/G30 in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: Review and meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.019. Epub 2006 Apr 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detera-Wadleigh SD, Badner JA, Berrettini WH, Yoshikawa T, Goldin LR, Turner G, Rollins DY, Moses T, Sanders AR, Karkera JD, Esterling LE, Zeng J, Ferraro TN, Guroff JJ, Kazuba D, Maxwell ME, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Gershon ES. A high-density genome scan detects evidence for a bipolar-disorder susceptibility locus on 13q32 and other potential loci on 1q32 and 18p11.2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5604–5609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin B, Jones BL, Bacanu SA, Roeder K. Mixture models for linkage analysis of affected sibling pairs and covariates. Genet Epidemiol. 2002;22:52–65. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds LK, Mosley BJ, Admiraal AJ, Olds RJ, Romans SE, Silverstone T, Walsh AE. Familial bipolar disorder: Preliminary results from the Otago Familial Bipolar Genetic Study. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 1998;32:823–829. doi: 10.3109/00048679809073872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekholm JM, Kieseppa T, Hiekkalinna T, Partonen T, Paunio T, Perola M, Ekelund J, Lonnqvist J, Pekkarinen-Ijas P, Peltonen L. Evidence of susceptibility loci on 4q32 and 16p12 for bipolar disorder. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1907–1915. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhardt A, Lucae S, Unschuld PG, Ising M, Kern N, Salyakina D, Lieb R, Uhr M, Binder EB, Keck ME, Muller-Myhsok B, Holsboer F. Association of polymorphisms in P2RX7 and CaMKKb with anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord. 2007;101:159–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.11.016. Epub 2007 Jan 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald H, Degn B, Mors O, Kruse TA. Significant linkage between bipolar affective disorder and chromosome 12q24. Psychiatr Genet. 1998;8:131–140. doi: 10.1097/00041444-199800830-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallin MD, Lasseter VK, Avramopoulos D, Nicodemus KK, Wolyniec PS, McGrath JA, Steel G, Nestadt G, Liang KY, Huganir RL, Valle D, Pulver AE. Bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia: A 440-single-nucleotide polymorphism screen of 64 candidate genes among Ashkenazi Jewish case-parent trios. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:918–936. doi: 10.1086/497703. Epub 2005 Oct 2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Skol AD, Tsuang DW, Bingham S, Young KA, Prabhudesai S, Haverstock SL, Mena F, Menon AS, Bisset D, Pepple J, Sautter F, Baldwin C, Weiss D, Collins J, Keith T, Boehnke M, Tsuang MT, Schellenberg GD. Linkage of chromosome 13q32 to schizophrenia in a large veterans affairs cooperative study sample. Am J Med Genet. 2002;114:598–604. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyer AJ, Weissman MM. Genetic linkage study of panic: Clinical methodology and description of pedigrees. Vol. 88. 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyer AJ, Hamilton SP, Durner M, Haghighi F, Heiman GA, Costa R, Evgrafov O, Adams P, de Leon AB, Taveras N, Klein DF, Hodge SE, Weissman MM, Knowles JA. A third-pass genome scan in panic disorder: Evidence for multiple susceptibility loci. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:388–401. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glidden DV, Liang KY, Chiu YF, Pulver AE. Multipoint affected sibpair linkage methods for localizing susceptibility genes of complex diseases. Genet Epidemiol. 2003;24:107–117. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Hoven CW. Bipolar-panic comorbidity in the general population: Prevalence and associated morbidity. J Affect Disord. 2002;70:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00398-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Pickering RP, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green E, Elvidge G, Jacobsen N, Glaser B, Jones I, O’Donovan MC, Kirov G, Owen MJ, Craddock N. Localization of bipolar susceptibility locus by molecular genetic analysis of the chromosome 12q23-q24 region in two pedigrees with bipolar disorder and Darier’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:35–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg DA, Feenstra B, Hodge SE. Assuming independent male-female (m-f) recombination fraction (RF) can reveal imprinting. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:573. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton SP, Fyer AJ, Durner M, Heiman GA, Baisre de Leon A, Hodge SE, Knowles JA, Weissman MM. Further genetic evidence for a panic disorder syndrome mapping to chromosome 13q. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2550–2555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0335669100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori E, Liu C, Badner JA, Bonner TI, Christian SL, Maheshwari M, Detera-Wadleigh SD, Gibbs RA, Gershon ES. Polymorphisms at the G72/G30 gene locus, on 13q33, are associated with bipolar disorder in two independent pedigree series. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1131–1140. doi: 10.1086/374822. Epub 2003 Mar 1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge SE, Anderson CE, Neiswanger K, Sparkes RS, Rimoin DL. The search for heterogeneity in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM): Linkage studies, two-locus models, and genetic heterogeneity. Am J Hum Genet. 1983;35:1139–1155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge SE, Abreu PC, Greenberg DA. Magnitude of type I error when single-locus linkage analysis is maximized over models: A simulation study. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:217–227. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Segre AM, OConnell J, Wang H, Vieland V. KELVIN: A 2nd generation distributed multiprocessor linkage and linkage disequilibrium analysis program [abstract 1556]. Paper presented at ASHG 56th annual meeting.2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kelsoe JR, Spence MA, Loetscher E, Foguet M, Sadovnick AD, Remick RA, Flodman P, Khristich J, Mroczkowski-Parker Z, Brown JL, Masser D, Ungerleider S, Rapaport MH, Wishart WL, Luebbert H. A genome survey indicates a possible susceptibility locus for bipolar disorder on chromosome 22. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:585–590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011358498. Epub 2001 Jan 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. Epidemiology of psychiatric comorbidity. In: Tsuane MT, Touan M, Zahner G, editors. Textbook in psychiatric epidemiology. Wiley; New York: 1995. pp. 179–197. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles JA, Fyer AJ, Vieland VJ, Weissman MM, Hodge SE, Heiman GA, Haghighi F, de Jesus GM, Rassnick H, Preud’homme-Rivelli X, Austin T, Cunjak J, Mick S, Fine LD, Woodley KA, Das K, Maier W, Adams PB, Freimer NB, Klein DF, Gilliam TC. Results of a genome-wide genetic screen for panic disorder. Am J Med Genet. 1998;81:139–147. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980328)81:2<139::aid-ajmg4>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg JR, Brown JL, Sadovnick AD, Remick RA, Keck PE, Jr, McElroy SL, Rapaport MH, Thompson PM, Kaul JB, Vrabel CM, Schommer SC, Wilson T, Pizzuco D, Jameson S, Schibuk L, Kelsoe JR. Evaluating the parent-of-origin effect in bipolar affective disorder. Is a more penetrant subtype transmitted paternally? J Affect Disord. 2000;59:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korostishevsky M, Kaganovich M, Cholostoy A, Ashkenazi M, Ratner Y, Dahary D, Bernstein J, Bening-Abu-Shach U, Ben-Asher E, Lancet D, Ritsner M, Navon R. Is the G72/G30 locus associated with schizophrenia? single nucleotide polymorphisms, haplotypes, and gene expression analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvajo M, Dhilla A, Swor DE, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. Evidence implicating the candidate schizophrenia/bipolar disorder susceptibility gene G72 in mitochondrial function. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:685–696. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002052. Epub 2007 Aug 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson DF, Levinson MD, Segurado R, Lewis CM. Genome scan meta-analysis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Part I. Methods and power analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:17–33. doi: 10.1086/376548. Epub 2003 Jun 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, He L. G72/G30 genes and schizophrenia: A systematic meta-analysis of association studies. Genetics. 2007;175:917–922. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.061796. Epub 2006 Dec 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MW, Sham P, Hwu HG, Collier D, Murray R, Powell JF. Suggestive evidence for linkage of schizophrenia to markers on chromosome 13 in Caucasian but not Oriental populations. Hum Genet. 1997;99:417–420. doi: 10.1007/s004390050382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Badner JA, Christian SL, Guroff JJ, Detera-Wadleigh SD, Gershon ES. Fine mapping supports previous linkage evidence for a bipolar disorder susceptibility locus on 13q32. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:375–380. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn A, Kashuk C, Petersen MB, Bailey JA, Cox DR, Antonarakis SE, Chakravarti A. Patterns of meiotic recombination on the long arm of human chromosome 21. Genome Res. 2000;10:1319–1332. doi: 10.1101/gr.138100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DF, McMahon FJ, Simpson SG, McInnis MG, DePaulo JR. Panic disorder with familial bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;42:90–95. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maziade M, Roy MA, Rouillard E, Bissonnette L, Fournier JP, Roy A, Garneau Y, Montgrain N, Potvin A, Cliche D, Dion C, Wallot H, Fournier A, Nicole L, Lavallee JC, Merette C. A search for specific and common susceptibility loci for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: A linkage study in 13 target chromosomes. Mol Psychiatry. 2001;6:684–693. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuffin P, Knight J, Breen G, Brewster S, Boyd PR, Craddock N, Gill M, Korszun A, Maier W, Middleton L, Mors O, Owen MJ, Perry J, Preisig M, Reich T, Rice J, Rietschel M, Jones L, Sham P, Farmer AE. Whole genome linkage scan of recurrent depressive disorder from the depression network study. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3337–3345. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi363. Epub 2005 Oct 3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen MB, Devlin B, Faraone SV, Nimgaonkar VL, Sklar P, Smoller JW, Jamra RA, Albus M, Bacanu SA, Baron M, Barrett TB, Berrettini W, Blacker D, Byerley W, Cichon S, Coryell W, Craddock N, Daly MJ, DePaulo JR, Edenberg HJ, Foroud T, Gill M, Gilliam TC, Hamshere M, Jones I, Jones L, Juo SH, Kelsoe JR, Lambert D, Lange C, Lerer B, Liu J, Maier W, MacKinnon JD, McInnis MG, McMahon FJ, Murphy DL, Nöthen MM, Nurnberger JI, Pato CN, Pato MT, Potash JB, Propping P, Pulver AE, Rice JP, Rietschel M, Scheftner W, Schumacher J, Segurado R, Van Steen K, Xie W, Zandi PP, Laird NM. Combined analysis from eleven linkage studies of bipolar disorder provides strong evidence of susceptibility loci on chromosomes 6q and 8q. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:582–595. doi: 10.1086/491603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohrenweiser HW, Tsujimoto S, Gordon L, Olsen AS. Regions of sex-specific hypo- and hyper-recombination identified through integration of 180 genetic markers into the metric physical map of human chromosome 19. Genomics. 1998;47:153–162. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morissette J, Villeneuve A, Bordeleau L, Rochette D, Laberge C, Gagne B, Laprise C, Bouchard G, Plante M, Gobeil L, Shink E, Weissenbach J, Barden N. Genome-wide search for linkage of bipolar affective disorders in a very large pedigree derived from a homogeneous population in quebec points to a locus of major effect on chromosome 12q23-q24. Am J Med Genet. 1999;88:567–587. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19991015)88:5<567::aid-ajmg24>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton NE. The detection and estimation of linkage between the genes for elliptocytosis and the Rh blood type. Am J Hum Genet. 1956;8:80–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulle JG, McDonough JA, Chowdari KV, Nimgaonkar V, Chakravarti A. Evidence for linkage to chromosome 13q32 in an independent sample of schizophrenia families. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:429–431. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott J. Linkage analysis and family classification under heterogeneity. Ann Hum Genet. 1983;47(Pt4):311–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1983.tb01001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott J. Analysis of human genetic linkage. Johns Hopkins Press; Baltimore: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pal DK, Durner M, Greenberg DA. Effect of misspecification of gene frequency on the two-point LOD score. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9:855–859. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prata D, Breen G, Osborne S, Munro J, St Clair D, Collier D. Association of DAO and G72(DAOA)/G30 genes with bipolar affective disorder. Am J Med Genet Part B. 2008;147B:914–917. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JP. The role of meta-analysis in linkage studies of complex traits. Am J Med Genet. 1997;74:112–114. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19970221)74:1<112::aid-ajmg22>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savino M, Perugi G, Simonini E, Soriani A, Cassano GB, Akiskal HS. Affective comorbidity in panic disorder: Is there a bipolar connection? J Affect Disord. 1993;28:155–163. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90101-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher J, Jamra RA, Freudenberg J, Becker T, Ohlraun S, Otte AC, Tullius M, Kovalenko S, Bogaert AV, Maier W, Rietschel M, Propping P, Nothen MM, Cichon S. Examination of G72 and D-amino-acid oxidase as genetic risk factors for schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:203–207. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segurado R, Detera-Wadleigh SD, Levinson DF, Lewis CM, Gill M, Nurnberger JI, Craddock N, DePaulo JR, Baron M, Gershon ES, Ekholm J, Cichon S, Turecki G, Claes S, Kelsoe JR, Schofield PR, Badenhop RF, Morissette J, Coon H, Blackwood D, McInnes LA, Foroud T, Edenberg HJ, Reich T, Rice JP, Goate A, McInnis MG, McMahon FJ, Badner JA, Goldin LR, Bennett P, Willour VL, Zandi PP, Liu J, Gilliam C, Juo SH, Berrettini WH, Yoshikawa T, Peltonen L, Lönnqvist J, Nöthen MM, Schumacher J, Windemuth C, Rietschel M, Propping P, Maier W, Alda M, Grof P, Rouleau GA, Del-Favero J, Van Broeckhoven C, Mendlewicz J, Adolfsson R, Spence MA, Luebbert H, Adams LJ, Donald JA, Mitchell PB, Barden N, Shink E, Byerley W, Muir W, Visscher PM, Macgregor S, Gurling H, Kalsi G, McQuillin A, Escamilla MA, Reus VI, Leon P, Freimer NB, Ewald H, Kruse TA, Mors O, Radhakrishna U, Blouin JL, Antonarakis SE, Akarsu N. Genome scan meta-analysis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, part III: Bipolar disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:49–62. doi: 10.1086/376547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw SH, Kelly M, Smith AB, Shields G, Hopkins PJ, Loftus J, Laval SH, Vita A, De Hert M, Cardon LR, Crow TJ, Sherrington R, DeLisi LE. A genome-wide search for schizophrenia susceptibility genes. Am J Med Genet. 1998;81:364–376. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19980907)81:5<364::aid-ajmg4>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine OC, Xu J, Koskela R, McMahon FJ, Gschwend M, Friddle C, Clark CD, McInnis MG, Simpson SG, Breschel TS, Vishio E, Riskin K, Feilotter H, Chen E, Shen S, Folstein S, Meyers DA, Botstein D, Marr TG, DePaulo JR. Evidence for linkage of bipolar disorder to chromosome 18 with a parent-of-origin effect. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:1384–1394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szadoczky E, Papp Z, Vitrai J, Rihmer Z, Furedi J. The prevalence of major depressive and bipolar disorders in Hungary. Results from a national epidemiologic survey. J Affect Disord. 1998;50:153–162. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talati A, Ponniah K, Strug LJ, Hodge SE, Fyer AJ, Weissman MM. Panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and a possible medical syndrome previously linked to chromosome 13. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.021. Epub 2007 Oct 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai HJ, Weeks DE. Comparison of methods incorporating quantitative covariates into affected sib pair linkage analysis. Genet Epidemiol. 2006;30:77–93. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieland VJ, Greenberg DA, Hodge SE. Adequacy of single-locus approximations for linkage analyses of oligogenic traits: Extension to multigenerational pedigree structures. Hum Heredity. 1993;43:329–336. doi: 10.1159/000154155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Segre AM, Huang Y, O’Connell J, Vieland VJ. Rapid Computation of Large Numbers of LOD Scores in Linkage Analysis through Polynomial Expression of Genetic Likelihoods. Paper presented at IEEE Workshop on High-Throughput Data Analysis for Proteomics and Genomics; Silicon Valley. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Faravelli C, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Joyce PR, Karam EG, Lee CK, Lellouch J, Lepine JP, Newman SC, Oakley-Browne MA, Rubio-Stipec M, Wells JE, Wickramaratne PJ, Wittchen HU, Yeh EK. The cross-national epidemiology of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:305–309. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160021003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Fyer AJ, Haghighi F, Heiman G, Deng Z, Hen R, Hodge SE, Knowles JA. Potential panic disorder syndrome: Clinical and genetic linkage evidence. Am J Med Genet. 2000;96:24–35. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000207)96:1<24::aid-ajmg7>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NM, Green EK, Macgregor S, Dwyer S, Norton N, Williams H, Raybould R, Grozeva D, Hamshere M, Zammit S, Jones L, Cardno A, Kirov G, Jones I, O’Donovan MC, Owen MJ, Craddock N. Variation at the DAOA/G30 locus influences susceptibility to major mood episodes but not psychosis in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:366–373. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LT, Cooke RG, Robb JC, Levitt AJ, Joffe RT. Anxious and non-anxious bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 1993;29:49–52. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubenko GS, Maher B, Hughes HB, III, Zubenko WN, Stiffler JS, Kaplan BB, Marazita ML. Genome-wide linkage survey for genetic loci that influence the development of depressive disorders in families with recurrent, early-onset, major depression. Am J Med Genet Part B. 2003;123B:1–18. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]