Abstract

Background

National guidelines for primary prevention suggest consideration of lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease in addition to 10-year risk, but it is currently unknown how many U.S. adults would be identified as having low short-term but high lifetime predicted risk if stepwise stratification were employed.

Methods and Results

We included 6,329 CVD-free and nonpregnant individuals aged 20 to 79 years, representing approximately 156 million U.S. adults, from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004 and 2005–2006. We assigned 10-year and lifetime predicted risks to stratify participants into three groups: low 10-year (<10%)/low lifetime (<39%) predicted risk, low 10-year (<10%)/high lifetime (≥39%) predicted risk, and high 10-year (≥10%) predicted risk or diagnosed diabetes. The majority of U.S. adults (56%, or 87 million individuals) are at low short-term but high lifetime predicted risk for cardiovascular disease. Twenty-six percent (41 million adults) are at low short-term and low lifetime predicted risk, and only 18% (28 million individuals) are at high short-term predicted risk. The addition of lifetime risk estimation to 10-year risk estimation identifies higher risk women and younger men in particular.

Conclusions

Whereas 82% of U.S. adults are at low short-term risk, two-thirds of this group, or 87 million people, are at high lifetime predicted risk for cardiovascular disease. These results provide support for use of a stepwise stratification system aimed at improving risk communication, and they provide a baseline for public health efforts aimed at increasing the proportion of Americans with low short-term and low lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease.

INTRODUCTION

The vast majority of U.S. adults, particularly women and younger men, are at low short-term risk (<10% in 10 years) for a coronary event by National Cholesterol Education Program/Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP/ATP III) guidelines.1–3 However, this large “low-risk” population is actually comprised of those who remain low risk as well as those who become high risk across the lifespan. We previously developed an algorithm to predict lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and found that risk factors measured at age 50 years effectively stratified Framingham Study participants to a spectrum of observed lifetime CVD rates (5.2 to 68.9%) and median survivals (>39 to 28 years).4 These patterns were similar in contemporary U.S. multi-ethnic cohorts for risk factors measured at various ages.5 Furthermore, we recently employed this algorithm to investigate the implications of long-term predicted risk for CVD specifically among those at low 10-year predicted risk for coronary heart disease (CHD).6 Even at younger ages (32 to 50 years), individuals with low (<10%) short-term but high (≥39%) lifetime predicted risk had greater burden and progression of subclinical CVD compared with the low short-term and low (<39%) lifetime risk group.6

Recognizing that current risk assessment strategies may inadequately assess CVD risk in many women and younger men, U.S. national guidelines from the NCEP7 and the American Heart Association8 now endorse consideration of lifetime risk in primary prevention. Although pharmacotherapy based on lifetime risk is not specifically recommended in the guidelines, it is recommended that those at high lifetime risk receive intensified lifestyle counseling and risk factor monitoring. Furthermore, specific lifetime risk estimates may be used to enhance risk communication and motivation for patients with high predicted lifetime risk but low predicted short-term risk, as well as to assist policy makers and researchers seeking to understand current or project future CVD burden. However, a formal method for synthesizing information about 10-year and lifetime risks is not currently provided. A stepwise stratification system whereby individuals with low short-term predicted risk are then evaluated for lifetime predicted risk could accomplish this, but the potential utility of designating a low short-term/high lifetime risk group of Americans would be better appreciated if the population prevalence of this group were known. Therefore, we applied our previously published lifetime risk algorithm to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003 to 2006 dataset to estimate the numbers of U.S. adults in each of three risk groups: low short-term CHD/low lifetime CVD, low short-term CHD/high lifetime CVD, and high short-term CHD predicted risk.

METHODS

Study Participants

We included CVD-free, nonpregnant participants aged 20 to 79 years who completed a mobile examination in the 2003–2004 or 2005–2006 NHANES (N=7,396), which provided representative samples of the non-institutionalized U.S. population9 targeted by the NCEP/ATP III for cardiovascular risk prediction.7 We defined participants as having CVD if they answered “yes” when asked if a doctor or health professional ever told them they had coronary heart disease, heart attack, stroke, or congestive heart failure. We excluded participants with missing values for blood pressure (N=698), cholesterol (N=306), or height or weight (N=63) to obtain our final study sample (N=6,329) (Supplemental Figure 1). For self-reported data, answers other than “yes” were assumed to be “no.”

Risk Factor Ascertainment

We defined CVD risk factors as follows. Diabetes mellitus was defined by self-reported health-professional-diagnosed diabetes (but not “borderline” diabetes); cigarette smoking was defined by self-report of currently smoking every day or some days and having smoked ≥100 cigarettes in their lifetime; and antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medication use were also defined by self-report. Blood pressure measures were performed by trained and certified physicians using previously-described procedures and a mercury manometer;9 the average of the last two measurements were used whenever available, although single measurements were used if they were the only available measurements. Total and HDL cholesterol were measured as described previously.9 Obesity was defined as a body mass index ≥30 kg/m2.

Definitions of Risk Strata

We determined the distribution of three risk strata in the U.S. population: low 10-year/low lifetime, low 10-year/high lifetime, and high 10-year predicted risk, as defined below. For the main analysis, we calculated 10-year predicted risk for hard CHD (myocardial infarction or coronary death) for all participants using the ATP III risk assessment tool,10 and we defined a calculated risk of ≥10% or diagnosed diabetes as “high 10-year predicted risk,” since individuals with this level of predicted risk would potentially be eligible for intensive preventive measures, including drug therapy.7 Among the participants with low (<10%) 10-year predicted risk (and no diabetes), we assigned lifetime predicted risk for CVD (myocardial infarction, coronary insufficiency, angina, atherothrombotic stroke, intermittent claudication, or CVD death) using our previously published algorithm,4, 6 as shown in Table 1. We defined “low lifetime predicted risk” as the two lower risk strata (“all optimal” or “≥1 not optimal” risk factors), which according to our prior work have predicted lifetime risk <39%,4 and “high lifetime predicted risk” as the three higher risk strata (“≥1 elevated,” “1 major” or “≥2 major” risk factors), which have predicted lifetime risk ≥39%.4 This stratification was chosen a priori based on the previously observed apparent natural separation in lifetime risks of these two groups in the Framingham cohorts4 as well as in a large pooled sample of U.S. multi-ethnic cohorts.5 It has been further justified with recent work demonstrating differential burden and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in younger adults using the identical stratification algorithm.6

Table 1.

Risk Factor Definitions and Lifetime Risk Stratification*

| CVD Risk Factors | Optimal RF | Not Optimal RF | Elevated RF | Major RF† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic (SBP) and Diastolic (DBP) Blood | SBP <120 and | SBP 120–139 or | SBP 140–159 or | SBP ≥160 or DBP ≥100 | |

| Pressure (mm Hg) | DBP <80 AND |

DBP 80–89 OR |

DBP 90–99 OR |

or treated OR |

|

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | <180 AND |

180–199 AND |

200–239 AND |

≥240 or treated OR |

|

| Diabetes Mellitus | No AND |

No AND |

No AND |

Yes OR |

|

| Current Smoking | No | No | No | Yes | |

| Lifetime Risk Stratification | Low Predicted Lifetime Risk | High Predicted Lifetime Risk | |||

| All Optimal RF | ≥1 RF Not Optimal | ≥1 Elevated RF | 1 Major RF | ≥2 Major RF | |

| Predicted Lifetime Risk at age 50, Men | 5% | 36% | 46% | 50% | 69% |

| Predicted Lifetime Risk at age 50, Women | 8% | 27% | 39% | 39% | 50% |

Lifetime risk refers to risk of all atherosclerotic CVD (myocardial infarction, coronary insufficiency, angina, atherothrombotic stroke, intermittent claudication, or CVD death). An individual’s risk stratum is the highest risk stratum for which any of the individual’s risk factors are eligible.4

In a secondary analysis, obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and low HDL cholesterol (<40 mg/dL for a man or <50 mg/dL for a woman) were also counted as major risk factors. Lifetime risk estimates for this secondary stratification are not shown, but are similar to those above.

CVD=cardiovascular disease, RF=risk factor.

In further analyses, we also included obesity (BMI ≥30kg/m2) and low HDL cholesterol (<40 mg/dL for men, <50 mg/dL for women) as major risk factors. To examine whether a more stringent definition of low short-term risk would weaken the distinction of different lifetime predicted risk groups among those at low-short term predicted risk, we also repeated the primary stratification described above using two additional definitions of short-term risk. For the first, we defined low short-term risk as <6% predicted 10-year risk for hard CHD (and absence of diabetes) using the ATP III risk assessment tool.10 For the second, we defined low short-term risk as <20% predicted 10-year risk for total CVD (coronary death, myocardial infarction, coronary insufficiency, angina, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, transient ischemic attack, intermittent claudication, or heart failure) (and absence of diabetes) using the risk functions published by D’Agostino et al.11

Statistical Analysis

We used survey procedures in SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC) to generate accurate frequencies and variances accounting for the complex, multistage design of the NHANES. We used the survey weights to estimate the number of non-institutionalized, CVD-free and nonpregnant U.S. adults aged 20 to 79 years in each group. Analyses were performed for all eligible adults overall as well as stratified by age, sex, and race subgroups. For some subgroup analyses, we split the population into fewer categories in order to avoid presenting data from cells with fewer than 30 subjects as recommended by the NHANES Analytical Guidelines.9 When results from fewer subjects are provided, this is noted in the tables. Differences between groups in the distribution of risk strata were assessed using the χ2 test, and a two-tailed P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

A total of 6,329 individuals (representing approximately 156 million U.S. adults) met inclusion criteria and had complete information to determine their short-term and lifetime risk strata (Supplemental Figure 1). Exclusion on the basis of missing variables was somewhat more likely for blacks (19.4%) compared with whites (12.1%). The final study sample was representative of 86.4% of the non-institutionalized, nonpregnant, CVD-free U.S. population aged 20 to 79 years. Specific participant characteristics, weighted to reflect the U.S. population, are shown in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Distribution of risk strata

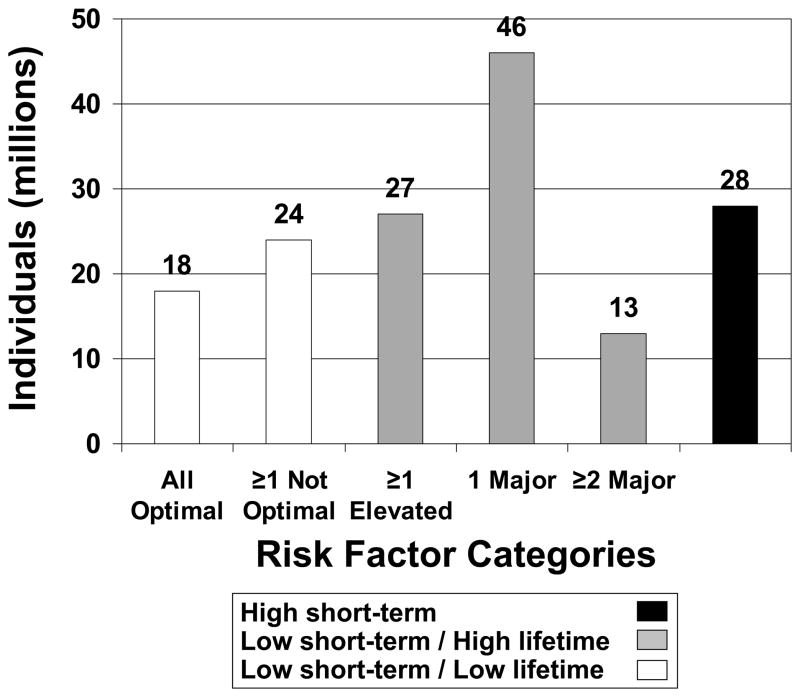

Among the overwhelming majority (82.0%) of U.S. adults with low short-term predicted risk (Table 2), two-thirds are at high lifetime predicted risk, whereas only one-third are at low lifetime predicted risk (see Table 1). Of note, the proportion of U.S. adults with very low lifetime risk due to all optimal risk factors is small, at 11.4%; the proportion is smaller in men than women and is dramatically smaller in older compared with younger age groups (Table 2). The estimated size of the U.S. population in each risk stratum is shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Distribution of Combined 10-Year CHD* and Lifetime CVD Predicted Risk Strata in the CVD-free, Nondiabetic, Nonpregnant, 20- to 79-Year Old U.S. Population

| n | Weighted, n | Percentage (SE) of U.S. Population in Risk Stratum | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low 10-Year CHD*/Low Lifetime CVD Predicted Risk | Low 10-Year CHD*/High Lifetime CVD Predicted Risk | High 10-Year CHD* Predicted Risk | |||||||

| All Optimal | ≥1 Not Optimal | ≥1 Elevated | 1 Major | ≥2 Major | |||||

| Total | 6,329 | 156,100,000 | 11.4 (0.4) | 15.1 (0.7) | 17.5 (0.7) | 29.7 (0.7) | 8.3 (0.5) | 18.0 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Men | 3,254 | 77,760,000 | 8.4 (0.6) | 14.8 (1.0) | 16.9 (1.0) | 27.9 (0.9) | 5.8 (0.7) | 26.2 (1.2) | |

| Women | 3,075 | 78,370,000 | 14.3 (0.7) | 15.3 (0.9) | 18.2 (0.9) | 31.6 (0.9) | 10.8 (0.6) | 9.9 (0.6) | |

| Age | |||||||||

| Men | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 20–29 | 686 | 16,400,000 | 18.8 (1.8) | 21.6 (1.5) | 14.4 (1.4) | 42.1 (2.1) | 2.7 (0.7)† | 0.4 (0.2)† | |

| 30–39 | 641 | 17,400,000 | 10.4 (1.5) | 21.7 (2.3) | 23.8 (2.3) | 33.1 (1.6) | 8.7 (1.4) | 2.3 (0.6)† | |

| 40–49 | 662 | 18,800,000 | 5.6 (1.1) | 14.9 (1.9) | 20.6 (2.3) | 32.1 (2.4) | 8.2 (1.3) | 18.7 (1.9) | |

| 50–59 | 469 | 14,000,000 | 3.4 (0.9)† | 9.0 (1.7) | 16.8 (2.1) | 19.0 (2.6) | 6.5 (1.6)† | 45.4 (2.7) | |

| 60–79 | 796 | 11,300,000 | 3.0 (0.8)† | 7.4 (0.9) | 89.6 (1.1) | ||||

| Women | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 20–29 | 582 | 13,900,000 | 35.5 (2.3) | 20.1 (1.8) | 10.6 (1.1) | 31.0 (2.4) | 1.4 (0.6)† | 1.4 (0.5)† | |

| 30–39 | 564 | 16,600,000 | 21.5 (1.4) | 20.9 (1.9) | 20.4 (2.0) | 28.7 (2.3) | 6.1 (1.0)† | 2.4 (0.6)† | |

| 40–49 | 626 | 18,400,000 | 11.3 (1.8) | 18.2 (1.9) | 23.4 (2.1) | 30.8 (2.0) | 9.3 (1.2) | 7.0 (1.1) | |

| 50–59 | 466 | 14,400,000 | 3.2 (0.7)† | 10.6 (1.5) | 20.9 (2.6) | 35.6 (2.7) | 20.1 (2.0) | 9.6 (1.5) | |

| 60–79 | 837 | 15,000,000 | 0.9 (0.4)† | 5.6 (0.9) | 13.7 (1.4) | 32.4 (1.7) | 17.6 (1.4) | 29.8 (1.4) | |

| Race | |||||||||

| Men | <0.001 | ||||||||

| White | 1,611 | 56,340,000 | 8.0 (0.8) | 13.7 (1.3) | 16.5 (1.4) | 28.0 (1.1) | 6.0 (0.9) | 27.9 (1.5) | |

| Black | 699 | 7,880,000 | 8.3 (1.1) | 18.7 (1.7) | 16.1 (1.5) | 27.9 (1.9) | 5.1 (1.1) | 24.0 (1.5) | |

| Mexican-American | 836 | 10,800,000 | 11.7 (1.3) | 17.0 (1.8) | 16.6 (1.5) | 28.4 (1.8) | 6.4 (1.2) | 20.0 (1.9) | |

| Other | 108 | 2,700,000 | 23.7 (4.8)† | 52.0 (4.0) | 24.3 (4.2)† | ||||

| Women | <0.001 | ||||||||

| White | 1,520 | 56,420,000 | 12.3 (0.8) | 14.8 (1.2) | 18.1 (1.1) | 33.7 (1.2) | 11.6 (0.8) | 9.6 (0.7) | |

| Black | 674 | 8,840,000 | 14.9 (1.9) | 18.0 (1.1) | 14.8 (1.5) | 28.8 (2.1) | 12.2 (1.0) | 11.4 (1.7) | |

| Mexican-American | 776 | 10,000,000 | 24.7 (2.3) | 16.4 (1.5) | 19.8 (2.2) | 22.3 (1.7) | 7.6 (1.3) | 9.3 (1.2) | |

| Other | 105 | 3,090,000 | 28.1 (4.0)† | 59.8 (4.1) | 12.2 (2.1)† | ||||

10-year hard coronary heart disease risk calculated based on D’Agostino et al10 with “low” defined as <10% 10-year predicted CHD risk and absence of diabetes.

Estimate unstable due to subsample size <30

The p value in the first row is for the comparison across columns (risk categories); all other p values are for the comparison across the rows below (demographic categories).

SE=standard error, CHD=coronary heart disease, CVD=cardiovascular disease.

Figure 1.

Population estimates of risk strata among CVD-free, nonpregnant U.S. adults aged 20 to 79 years. Low short-term risk is defined as <10% 10-year predicted risk for hard CHD (myocardial infarction or coronary death) and absence of diabetes using the ATP III algorithm.10 Low lifetime predicted risk is defined as <39% lifetime risk for CVD (myocardial infarction, coronary insufficiency, angina, atherothrombotic stroke, intermittent claudication, or CVD death) using our previously published algorithm.4 See Table 1 for lifetime risk strata definitions.

Effect of demographic variables on risk strata

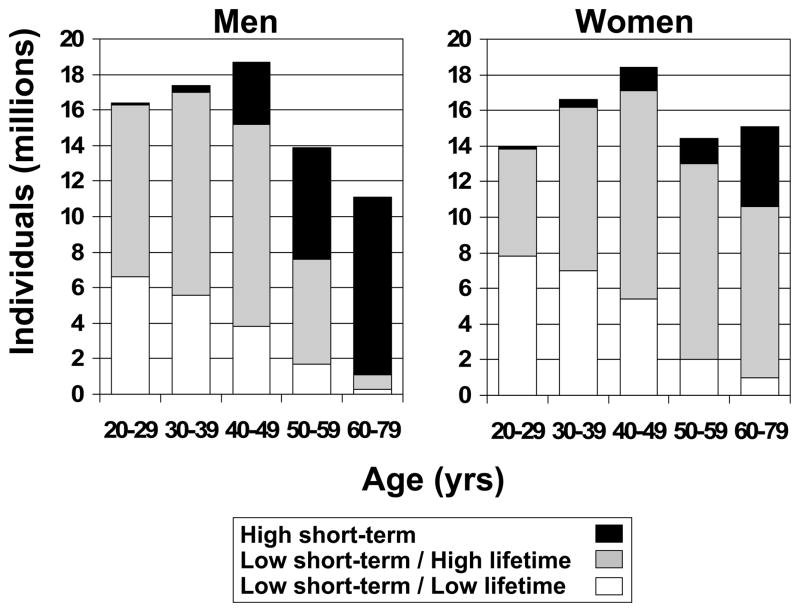

At the youngest ages, almost all men and women are at low short-term predicted risk, and further stratification by lifetime predicted risk produces two groups of substantial sizes in both sexes (Table 2). For example, as shown in Figure 2, the majority of men less than 60 years and women less than 80 years old are at low 10-year predicted risk, and among this large group the vast majority have low 10-year but high lifetime predicted risk. However, at older ages the proportion at high short-term predicted risk is markedly higher in men than in women, such that in the oldest age group (60–79 years) only 10.4% of men but 70.2% of women are at low-short term predicted risk. Thus, at older ages, lifetime risk stratification identifies a much larger group of women (63.7% of women aged 60–79 years) with low short-term/high lifetime risk compared to men (7.4% of men aged 60–79 years) (Table 2, Figure 2). Patterns of predicted risks are similar between races; although Mexican-Americans had lower predicted risk compared to other racial groups (Table 2), this is likely due to their younger age distribution (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 2.

Sex- and age-specific population estimates of risk strata distribution among CVD-free, nonpregnant U.S. adults aged 20 to 79 years. See Figure 1 for definitions.

Effect of including low HDL cholesterol and obesity as major risk factors

When low HDL cholesterol and obesity are also counted as major risk factors, the proportion with high lifetime predicted risk is larger, though modestly so (Table 3). For example, including both risk factors causes about 10.3% of adults to move from the low short-term/low lifetime predicted risk group to the low short-term/high lifetime predicted risk group.

Table 3.

Distribution of Combined 10-Year CHD* and Lifetime CVD Predicted Risk Strata in the CVD-free, Nondiabetic, Nonpregnant, 20- to 79-Year Old U.S. Population - With Obesity† and Low HDL Cholesterol‡ Included as Major Risk Factors

| n | Weighted, n | Percentage (SE) of U.S. Population in Risk Stratum | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low 10-Year CHD*/Low Lifetime CVD Predicted Risk | Low 10-Year CHD*/High Lifetime CVD Predicted Risk | High 10-Year CHD* Predicted Risk | |||||||

| All Optimal | ≥1 Not Optimal | ≥1 Elevated | 1 Major | ≥2 Major | |||||

| Neither included | 6,329 | 156,100,000 | 11.4 (0.4) | 15.1 (0.7) | 17.5 (0.7) | 29.7 (0.7) | 8.3 (0.5) | 18.0 (0.8) | |

| Both included | 6,329 | 156,100,000 | 7.5 (0.4) | 8.7 (0.6) | 10.1 (0.7) | 29.0 (0.8 | 26.7 (0.9) | 18.0 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Obesity only | 6,329 | 156,100,000 | 9.2 (0.4) | 10.4 (0.7) | 11.8 (0.7) | 33.2 (0.8) | 17.4 (0.7) | 18.0 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Low HDL-C only | 6,329 | 156,100,000 | 8.6 (0.4) | 11.4 (0.6) | 13.8 (0.7) | 31.8 (0.9) | 16.3 (0.7) | 18.0 (0.8) | <0.001 |

10-year hard coronary heart disease risk calculated based on D’Agostino et al,10 with “low” defined as <10% 10-year predicted CHD risk and absence of diabetes.

Obesity defined as BMI ≥30 kg/m2

Low HDL-C defined as <40 mg/dL for men and <50 mg/dL for women

p is for the comparison to the stratification without HDL-C and obesity included.

SE=standard error, CHD=coronary heart disease, CVD=cardiovascular disease, HDL-C=high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Distribution of major risk factors

Table 4 gives the proportion and absolute numbers of U.S. adults affected with each of the elevated and major risk factors. The wide distribution of isolated risk factors indicates that no single risk factor is responsible for determining the lifetime risk stratification. For example, despite its high prevalence (especially among younger adults), smoking as the sole risk factor results in high lifetime predicted risk status in only 9.4% of individuals who have low short-term predicted risk.

Table 4.

Estimated Prevalence of Major or Elevated Risk Factors in the CVD-free, Nonpregnant, 20- to 79-Year Old U.S. Population

| Major Risk Factor | Diabetes mellitus | Smoking | TC ≥ 240 mg/dL | Lipid-lowering treatment | SBP ≥160 | DBP ≥100 | Anti-hypertensive therapy | Obesity* | Low HDL-C* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total individuals with major risk factor | 8,770,000 (5.6%) | 40,510,000 (25.9%) | 25,300,000 (16.2%) | 16,500,000 (10.6%) | 4,680,000 (3.0%) | 1,600,000 (1.0%) | 25,720,000 (16.5%) | 50,800,000 (32.5%) | 41,350,000 (26.5%) |

| Elevated or Major Risk Factor | Diabetes mellitus | Smoking | TC ≥ 200 mg/dL | Lipid- lowering treatment | SBP ≥140 | DBP ≥90 | Anti-hypertensive therapy | Obesity* | Low HDL-C* |

| Individuals at low 10-year CHD risk† with this as the only elevated or major risk factor resulting in high lifetime CVD risk status | - | 9,700,000 (9.4%) | 19,100,000 (18.6%) | 850,000 (0.8%) | 510,000 (0.5%)‡ | 300,000 (0.3%)‡ | 870,000 (0.8%) | 5,950,000 (5.8%) | 5,300,000 (5.2%) |

Obesity = BMI ≥30 kg/m2; Low HDL = <40 mg/dL in a man and <50 mg/dL in a woman

10-year hard coronary heart disease risk calculated based on D’Agostino et al,10 with “low” defined as <10% 10-year predicted CHD risk and absence of diabetes.

Unstable estimate due to subsample size <30

CVD=cardiovascular disease, TC=total cholesterol, SBP=systolic blood pressure, DBP=diastolic blood pressure, HDL-C=high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Effect of altering low short-term risk definitions

When low short-term risk is defined either as <6% predicted 10-year risk for hard CHD (and absence of diabetes) using the ATP III risk assessment tool10 or as <20% predicted 10-year risk for total CVD (and absence of diabetes) using the risk functions published by D’Agostino et al,11 the distribution of lifetime predicted risk among those at low short-term predicted risk does not change meaningfully (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Principal Findings

The present report represents the first analysis of the distribution of lifetime CVD risk strata in the U.S. population, and it has two major findings. First, the overwhelming majority (82%) of U.S. adults are at low (<10%) short-term predicted risk for a coronary event, but this majority is comprised of two groups: one-third in the low short-term CHD/low lifetime CVD predicted risk group and two-thirds (i.e., 87 million individuals) in the low short-term CHD/high lifetime CVD predicted risk group. Among those 40 to 59 years of age, a group that may be of particular interest for clinical prevention, 80% have low short-term predicted risk, but three-fourths of these have high lifetime predicted risk. Second, the size of the low short-term/high lifetime predicted risk group is substantial in women and younger men, precisely the populations for which the ATP III risk assessment tool has been shown to discriminate risk poorly.1, 12–14

Current Study in Context

Prior studies have reported the distribution of lifetime CVD risk strata in selected cohorts.4–6 Using the same lifetime risk algorithm employed in the present study, these prior studies demonstrated that the low short-term risk group is actually comprised of two groups, which are defined by lifetime predicted risk and are quite disparate with respect to subclinical disease burden and progression6 as well as CVD event rates over the lifespan.4, 5 While these studies are valuable for their outcome measurements, a strength of the present study is that the contemporary nationally representative sample provides more relevant information about the current distribution of lifetime risk strata in the U.S.

Previous reports have provided the distribution of short-term CHD risk strata in the U.S. population, with about three-fourths of U.S. adults consistently classified as “low risk” by ATP III guidelines.1–3 However, there has been no prior report of the distribution of lifetime CVD risk strata in the U.S. population, and the present paper demonstrates the striking departure of this distribution from that of 10-year CHD risk. Whereas 82% of CVD-free U.S. adults are at “low risk” based on 10-year CHD predicted risk alone, the group at “low/low risk” based on stepwise stratification by lifetime CVD predicted risk is much smaller, at 26 percent.

Significance of demographic variables and risk factor definitions

Although the Framingham risk score (FRS) for 10-year predicted risk of CHD represents an important advance in primary prevention that has allowed clinicians to match intensity of therapy to absolute risk, it has well-recognized limitations, particularly in women and younger men.1, 12–14 The stepwise stratification system employed in the present analysis identifies a low short-term/high lifetime predicted risk group that is highly prevalent in the U.S. population, and particularly in women and younger men. This is because the lifetime risk algorithm comprising the “second step” in our stratification is not dependent on sex or age and actually stratifies observed lifetime risk similarly for both sexes and all adult age groups studied to date,5 whereas the FRS (and the related ATP III tool) is overwhelmingly dependent on the weighting of the sex and age variables. In fact, we showed in the present analysis that the lifetime risk algorithm is not driven by any single risk factor and that it identifies a substantial low short-term/high lifetime risk group even when stringent definitions of low short-term risk are applied.

Clinical and Public Health Implications

We therefore believe that our results provide support for adoption of this stratification system by health care professionals to aid risk communication for a large segment of the U.S. population. Assigning a lifetime predicted risk status to U.S. adults presenting for primary prevention would change the message to those 87 million individuals with low short-term but high lifetime predicted risk. As an example of what these individuals may be counseled to expect in terms of absolute risk, 50 year-old participants in the Framingham Heart Study with “high predicted lifetime risk” had absolute lifetime risks for CVD of 45.5 to 68.9% for men and 39.1 to 50.2% for women.4 For a specific illustration of the motivational utility of the lifetime risk estimate, consider a 50 year-old nonsmoking, nondiabetic woman with total cholesterol of 240 mg/dL, HDL cholesterol of 58 mg/dL, and untreated systolic blood pressure of 160 mm Hg. Her 10-year hard CHD risk is just 2% according to ATP III, but her lifetime CVD risk is a more motivating 50%.4 Additionally, individuals with low short-term/high lifetime predicted risk could be informed that at present, even at young ages, they likely have significantly greater subclinical disease burden compared with those with low short-term/low lifetime predicted risk due to a more favorable risk factor profile.6 Such facts may be very useful for motivating lifestyle changes or adherence to pharmacologic therapy in the 56% of the population with low short-term predicted risk but significant risk factor burden.

As noted above and strikingly apparent in Figure 2, this may be particularly true for women and younger men. The more inclusive focus on total atherosclerotic CVD as the endpoint for lifetime risk makes the estimate more relevant for women, whose majority of first events are stroke rather than CHD15 and who suffer considerable morbidity and mortality from other non-CHD outcomes such as heart failure.8, 16, 17 Furthermore, the extended time frame of lifetime risk avoids false reassurance for women and younger men with unhealthy lifestyle habits who are nonetheless “low risk” for a coronary event in the short term. Given that more women than men die of CVD each year in the U.S.17 and that younger adults are beginning to see a reversal in declines in CHD mortality18 (likely due to increases in obesity, diabetes, hypertension and metabolic syndrome in this age group), relevant and motivating risk messages are urgently needed for these segments of the population. The addition of a second step to risk assessment with lifetime risk estimates shows promise in this regard.

We believe that our results may also prove useful on a public health level. Our data might assist in the estimation of costs associated with any new guidelines regarding long-term risk, and they also provide a current baseline for population burden of lifetime predicted risk against which the effects of future public health and clinical interventions may be measured. In particular, we report that only 11.4% of American adults are at optimal predicted risk. This is important because intensive pharmacologic and behavioral therapy to normalize risk factors in the 87 million individuals with low short-term/high lifetime predicted risk is unlikely to be feasible economically. Avoidance of the onset of risk factors in the first place – or primordial prevention19, 20 – has been shown to be not only a more sustainable but also a more effective means of reducing CVD mortality than either treating these risk factors (as in primary prevention) or treating clinical CVD (as in secondary prevention).21–23 In fact, multiple studies24–28 have defined and examined an optimal risk group and demonstrated that these individuals not only live substantially longer than those with one or more elevated risk factors, but they rarely develop CVD despite this longer life span, and additionally end up with fewer comorbidities, better health-related quality of life, and decreased health care costs in older age. Clearly, increasing the proportion of Americans with both low 10-year and low lifetime predicted risk would have dramatically beneficial effects on public health. Thus, programs that focus on primordial prevention, in combination with clinical practice that stresses the maintenance of a healthy lifestyle and monitors rates of adverse change in risk factor levels even before they become “treatable,” are likely to have the best long-term success in reducing the burden of CVD in the U.S.

Potential Limitations

Since fasting glucose levels were not available for the majority of participants, we relied on self-report to identify diabetes; therefore, a small proportion of individuals with undiagnosed diabetes may have been misclassified as lower risk. Additionally, the applicability of our risk stratification algorithms to all races is not assured; both the 10-year10 and lifetime4 risk stratification algorithms were developed in the exclusively white Framingham cohorts. However, the 10-year risk functions for hard CHD have since been shown to be transportable to other races,10, 29 and the lifetime risk stratification algorithm has been validated in the multi-ethnic (black and white) U.S. cohorts of the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry30 and the Cardiovascular Lifetime Risk Pooling Project5, 31 as well in CARDIA and MESA with data on subclinical disease.6 Finally, our short-term and lifetime predicted risks were for different endpoints; whereas the short-term outcome for our main analysis is hard CHD, as recommended by current guidelines,7 the lifetime outcome is total atherosclerotic CVD. However, we did compare short-term CVD to lifetime CVD predicted risk in a secondary analysis, and although ATP III focuses on hard CHD as the outcome of interest, the more inclusive outcome of total CVD may be more clinically relevant. We believe that in spite of the potential limitations, our delineation of short-term and lifetime risk strata among U.S. adults represents valuable information for policy makers and clinicians looking to confront the substantial burden of CVD in the United States.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES

None.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ford ES, Giles WH, Mokdad AH. The distribution of 10-year risk for coronary heart disease among US adults: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1791–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keevil JG, Cullen MW, Gangnon R, McBride PE, Stein JH. Implications of cardiac risk and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol distributions in the United States for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia: data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999 to 2002. Circulation. 2007;115:1363–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.645473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Persell SD, Lloyd-Jones DM, Baker DW. Implications of changing National Cholesterol Education Program goals for the treatment and control of hypercholesterolemia. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:171–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd-Jones DM, Leip EP, Larson MG, D’Agostino RB, Beiser A, Wilson PW, Wolf PA, Levy D. Prediction of lifetime risk for cardiovascular disease by risk factor burden at 50 years of age. Circulation. 2006;113:791–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.548206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berry JD, Cai X, Garside DB, Dyer A, Lloyd-Jones DM. Lifetime risks for cardiovascular disease for risk factors measured at ages 45-, 55-, 65-, and 75-years: results from the Cardiovascular Lifetime Risk Pooling Project. 2009 Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry JD, Liu K, Folsom AR, Lewis CE, Carr JJ, Polak JF, Shea S, Sidney S, O’Leary DH, Chan C, Lloyd-Jones DM. Prevalence and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in younger adults with low short-term but high lifetime estimated risk for cardiovascular disease: the CARDIA and MESA studies. Circulation. 2009;119:382–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.800235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosca L, Banka CL, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bushnell C, Dolor RJ, Ganiats TG, Gomes AS, Gornik HL, Gracia C, Gulati M, Haan CK, Judelson DR, Keenan N, Kelepouris E, Michos ED, Newby LK, Oparil S, Ouyang P, Oz MC, Petitti D, Pinn VW, Redberg RF, Scott R, Sherif K, Smith SC, Jr, Sopko G, Steinhorn RH, Stone NJ, Taubert KA, Todd BA, Urbina E, Wenger NK. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. Circulation. 2007;115:1481–501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Agostino RB, Sr, Grundy S, Sullivan LM, Wilson P. Validation of the Framingham coronary heart disease prediction scores: results of a multiple ethnic groups investigation. JAMA. 2001;286:180–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, Kannel WB. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berry JD, Lloyd-Jones DM, Garside DB, Greenland P. Framingham risk score and prediction of coronary heart disease death in young men. Am Heart J. 2007;154:80–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavanaugh-Hussey MW, Berry JD, Lloyd-Jones DM. Who exceeds ATP-III risk thresholds? Prev Med. 2008;47:619–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sibley C, Blumenthal RS, Merz CN, Mosca L. Limitations of current cardiovascular disease risk assessment strategies in women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15:54–6. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ridker PM, Cook NR, Lee IM, Gordon D, Gaziano JM, Manson JE, Hennekens CH, Buring JE. A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1293–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosca L, Appel LJ, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Chandra-Strobos N, Fabunmi RP, Grady D, Haan CK, Hayes SN, Judelson DR, Keenan NL, McBride P, Oparil S, Ouyang P, Oz MC, Mendelsohn ME, Pasternak RC, Pinn VW, Robertson RM, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Sila CA, Smith SC, Jr, Sopko G, Taylor AL, Walsh BW, Wenger NK, Williams CL. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. Circulation. 2004;109:672–93. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114834.85476.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, Ford E, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott M, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Nichol G, O’Donnell C, Roger V, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Stafford R, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong N, Wylie-Rosett J, Hong Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2009 update. Circulation. 2009;119:480–486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford ES, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease mortality among young adults in the U.S. from 1980 through 2002: concealed leveling of mortality rates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2128–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labarthe DR. Prevention of cardiovascular risk factors in the first place. Prev Med. 1999;29:S72–8. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strasser T. Reflections on cardiovascular diseases. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews. 1978:225–30. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, Critchley JA, Labarthe DR, Kottke TE, Giles WH, Capewell S. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2388–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unal B, Critchley JA, Capewell S. Explaining the decline in coronary heart disease mortality in England and Wales between 1981 and 2000. Circulation. 2004;109:1101–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118498.35499.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Unal B, Critchley JA, Fidan D, Capewell S. Life-years gained from modern cardiological treatments and population risk factor changes in England and Wales, 1981–2000. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:103–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.029579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daviglus ML, Liu K, Greenland P, Dyer AR, Garside DB, Manheim L, Lowe LP, Rodin M, Lubitz J, Stamler J. Benefit of a favorable cardiovascular risk-factor profile in middle age with respect to Medicare costs. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1122–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810153391606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daviglus ML, Liu K, Pirzada A, Yan LL, Garside DB, Feinglass J, Guralnik JM, Greenland P, Stamler J. Favorable cardiovascular risk profile in middle age and health-related quality of life in older age. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2460–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daviglus ML, Stamler J, Pirzada A, Yan LL, Garside DB, Liu K, Wang R, Dyer AR, Lloyd-Jones DM, Greenland P. Favorable cardiovascular risk profile in young women and long-term risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. JAMA. 2004;292:1588–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stamler J, Stamler R, Neaton JD, Wentworth D, Daviglus ML, Garside D, Dyer AR, Liu K, Greenland P. Low risk-factor profile and long-term cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality and life expectancy. JAMA. 1999;282:2012–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.21.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terry DF, Pencina MJ, Vasan RS, Murabito JM, Wolf PA, Hayes MK, Levy D, D’Agostino RB, Benjamin EJ. Cardiovascular risk factors predictive for survival and morbidity-free survival in the oldest-old Framingham Heart Study participants. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1944–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chambless LE, Folsom AR, Sharrett AR, Sorlie P, Couper D, Szklo M, Nieto FJ. Coronary heart disease risk prediction in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2003;56:880–890. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lloyd-Jones DM, Dyer AR, Wang R, Daviglus ML, Greenland P. Risk factor burden in middle age and lifetime risks for cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular death. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:535–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.09.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lloyd-Jones D, Thomas A, Berry JD, Van Horn L, Tracy RP, Dyer AR. Lifetime risks for fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events in different race/ethnic groups: Cardiovascular Lifetime Risk Pooling Project. 2009 Submitted. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.