Internalization of hu14.18-IL2 occurs through IL2 receptors on NK effectors and GD2 antigen on tumor targets, with slower tumor progression accounting for effective NK/tumor interactions.

Keywords: immune synapse, GD2, IL-2R, NK cells, melanoma, neuroblastoma

Abstract

The hu14.18-IL2 (EMD 273063) IC, consisting of a GD2-specific mAb genetically engineered to two molecules of IL-2, is in clinical trials for treatment of GD2-expressing tumors. Anti-tumor activity of IC in vivo and in vitro involves NK cells. We studied the kinetics of retention of IC on the surface of human CD25+CD16– NK cell lines (NKL and RL12) and GD2+ M21 melanoma after IC binding to the cells via IL-2R and GD2, respectively. For NK cells, ∼50% of IC was internalized by 3 h and ∼90% by 24 h of cell culture. The decrease of surface IC levels on NK cells correlated with the loss of their ability to bind to tumor cells and mediate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in vitro. Unlike NK cells, M21 cells retained ∼70% of IC on the surface following 24 h of culture and maintained the ability to become conjugated and lysed by NK cells. When NKL cells were injected into M21-bearing SCID mice, IT delivery of IC augmented NK cell migration into the tumor. These studies demonstrate that once IC binds to the tumor, it is present on the tumor surface for a prolonged time, inducing the recruitment of NK cells to the tumor site, followed by tumor cell killing.

Introduction

The hu14.18-IL2 IC is the second-generation form of the original ch14.18-IL2 [1]. It is comprised of the hu14.18 anti-GD2 antibody V regions that are joined at the genetic level to the human C κ and C γ heavy chains, the latter of which is fused at the carboxyl terminus to human IL-2. The hu14.18 mAb can recognize GD2 expressed on human melanomas [2, 3] and NB [4, 5] and potentially on some other human tumors expressing GD2, including small cell lung cancers [6], certain sarcomas [7, 8], and intracranial tumors [9]. Presently, IC is being tested in clinical trials in NB and melanoma [10, 11]. In these clinical studies, it was found that NK cells from patients mediate more potent lysis of GD2+ tumor cells in vitro when obtained after they received in vivo treatment with hu14.18-IL2 [10]. In A/J mice bearing NXS2, a GD2+ mouse NB, treatment with the hu14.18-IL2 IC induced strong NK cell-dependent antitumor responses against local and metastatic disease, which significantly exceeded the antitumor effects of the mAb combined with IL-2 [12, 13].

Following administration of radiolabeled ICs in vivo, localization to the tumor has been documented [14, 15]. This phenomenon is appreciably more pronounced when IC is injected IT [16]. Accumulation of IC in the tumor is accompanied by augmented migration of the immune cells into the tumor [17]. However, it remains unclear whether IC accumulates in the tumor passively, while being bound to IL-2- or FcR-expressing T and NK cells migrating to the tumor, or whether accumulation of IC in the tumor occurs first via direct binding to tumor antigen, followed by active recruitment and adhesion of T and NK cells to the tumor via binding of their IL-2R to the IL-2 component of IC.

Once bound to the cell surface, the IC would be subject to biological processes of the cell membrane, including possible internalization via antigen or IL-2R internalization. Indeed, IL-2Rs become internalized rapidly upon binding IL-2 molecules [18–20]. High-affinity [i.e., composed of α (CD25)-, β (CD122)-, and γ (CD132)-subunits] and intermediate-affinity (i.e., composed of only β- and γ-subunits) IL-2Rs can be internalized upon IL-2 binding [21, 22]. Human peripheral blood-derived NK cells express intermediate-affinity IL-2Rs but also can express high-affinity IL-2Rs upon activation [23–25]. Similarly to IL-2Rs, ganglioside antigens on certain types of tumor cells can also mediate internalization of mAb surface antigen complexes [26, 27].

In this study, we evaluated the stability of hu14.18-IL2 IC on the surface of human GD2+ tumor cells (M21 melanoma) and IL-2R+ NK cells (NKL and RL12 human NK cell lines). We found that melanoma and NK cells internalize hu14.18-IL2 IC, but NK cells internalized IC at a much higher rate. It was also found that internalization of cell surface-bound IC by NK cells diminished their subsequent ability to conjugate to GD2+ M21 cells and effectively lyse them. IC internalization by M21 cells (as well as by mouse NXS2 NB cells) occurred at a significantly slower rate; tumor cells pre-armed with IC could be targeted and lysed effectively by NK cells at any of the time-points tested. When hu14.18-IL2 IC was injected IT, it was detectable on the M21 tumor cell surface even 24 h after IC injection and coincided with augmented migration of resident and adoptively transferred NK cells into the tumor. Thus, the stability of hu14.18-IL2 IC binding to tumor cells and immune effectors, and the relative residence time on the cell surface, is affected by differences in internalization between the antibody target and the cytokine receptor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

hu14.18 antibody and IC

The GD2-specific hu14.18 antibody and 14.18-IL2 IC, which have been described previously [1, 28, 29], were obtained from EMD-Lexigen Research Center (Billerica, MA, USA). hu14.18-IL2 IC (1 μg) contains ∼3000 IU IL-2 activity, as determined previously [30]. Custom labeling of the hu14.18 antibody or hu14.18-IL2 IC with FITC was preformed by using EZ-Label FITC protein-labeling kit (53004; Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The products were purified by using the Slide-A-Lyzer mini dialysis unit (3500 MW cut-off; also from Pierce).

Cell lines

NKL [31] and RL12 (a HS-dependent subline of human leukemia NKL, obtained from Dr. Paul Leibson, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA) human NK cell lines were grown in complete RPMI-1640 cell culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 5% of fresh HS obtained from healthy donors, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin, and 25–250 U/ml exogenous human rIL-2 (TECIN, Hoffmann-La Roche, Nutley, NJ, USA) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Under certain experimental conditions, NKL and RL12 cells were grown in complete medium but without exogenous IL-2 for 24 h prior to using in experiments. K562 human chronic myelogenous leukemia, M21 human melanoma, L5178Y mouse T cell lymphoma, and CT26 mouse colon carcinoma cell lines were cultured in complete RPMI-1640 cell culture medium formulated as detailed above but without HS and IL-2. The NXS2 mouse NB cell line was grown in complete DMEM.

Labeling of cells with intravital dyes

CFSE (excitation: 490 nm; emission: 518 nm) and BODIPY 630/650-X succinimidyl ester (excitation: 630 nm; emission: 650 nm) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Prior to labeling, the cells were washed twice with room temperature–warm PBS to eliminate serum residua, resuspended in 10 ml 37°C–warm PBS, supplemented with 5 mM CFSE or 1 mM BODIPY, and incubated for 15 min at 37°C. The labeled cells were washed once with ice-cold 10% FCS PBS (to neutralize free, cell-unbound label), resuspended in complete cell culture medium, and thereafter incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere for 0–3 days prior to using in vitro and in vivo experiments.

Arming cells with hu14.18-IL2 IC

M21, NXS2, NKL, RL12, and L5178Y cells (3×106/0.1 ml) were incubated for 1 h on ice with 2 μg/sample FITC-labeled hu14.18-IL2 IC followed by cell washing with ice-cold PBS + 2% FCS.

Flow cytometry

The following anti-human or anti-mouse antibodies were used: anti-mouse CD16/CD32-FITC (clone 2.4G2), anti-mouse CD25-FITC (3C7), anti-human CD16-FITC (3G8), and anti-human CD25-FITC (M-A251; all from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA); anti-mouse CD49b-FITC (DX5; from eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA); and PE- or APC-conjugated polyclonal G-α-H IgG (from eBioscience or Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL, USA). The cells (3×105/0.05 ml) or single-cell tumor preparations were incubated on ice for 40 min with 1 μg/ml hu14.18 antibody, hu14.18-IL2 IC, other specific antibody, or isotype-matched control IgGs, and the unbound antibody was washed off. The flow cytometry analysis was performed on CellQuest software of a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Analysis of acquired data was performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

MFI ratio calculation

The MFI ratio was calculated by dividing the flow cytometric MFI value of cells stained with antigen-specific mAb by the MFI value for the same cells stained with isotype-matched control Ig. This approach allows for comparison of multiple test samples within a group and between different groups.

Effector cell–target cell conjugate formation essay

CFSE-labeled NKL or RL12 cells (1.5×105/0.1) and BODIPY 630/650-labeled M21 melanoma cells (1.5×105/0.1 ml; unless indicated otherwise) were mixed together in flow cytometry sample tubes (Falcon-35 5-ml polystyrene tubes) in complete RPMI-1640 medium, with or without 1 μg/ml hu14.18 antibody, 3000 U/ml IL-2 (the amount of IL-2 contained in 1 μg IC), 1 μg/ml hu14.18 antibody + 3000 U/ml IL-2, 1 μg/ml hu14.18-IL2 IC, or 1 μg/ml hu14.18-IL2 IC + 3000 U/ml IL-2, and the loose pellet was formed by the cell mixture centrifugation at 100 rpm/0.5 min, followed by incubation of the pelleted cells for 30 min at 37°C. Under certain experimental conditions, the tumor cells or NK cells were pre-armed with hu14.18-IL2 IC, as described above, prior to mixing together in the flow cytometry tubes for conjugate formation. After 30 min of incubation, the pellet was agitated gently by tapping the tube on the firm surface, and the cells were tested by flow cytometry for M21-NK cell conjugate formation.

IC internalization assay

M21, NXS2, NKL, RL12, and L5178Y cells (3×106/0.1 ml complete cell culture medium without HS and IL-2) were armed with 2 μg FITC-conjugated IC on ice for 1 h, and the excess of IC was removed by cell washing in ice-cold PBS. The cells were resuspended in complete medium without HS and IL-2, distributed into 1 ml polypropylene Eppendorf tubes, and placed in 37°C water bath in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. After 0–24 h of IC-armed cell incubation, the pellets were harvested by pipetting, washed with ice-cold PBS to remove the shed IC, and thereafter labeled with secondary APC-conjugated G-α-H IgG for any IC still present on the surface. The double-labeled cells were analyzed for FITC and APC by flow cytometry. As a control for IC-FITC, a mouse anti-human IgG-FITC was used. The MFI ratios were determined by dividing FITC/APC MFI values of samples that were armed with IC-FITC and later stained with secondary G-α-H IgG-APC by the FITC/APC MFI value of the sample that was armed with mouse anti-human IgG-FITC and G-α-H IgG-APC. This approach allows for comparison of multiple samples within a group and between different groups. The kinetics of IC internalization is expressed as percentage of relative retention of FITC/APC MFI values of samples incubated at 37°C for 0.5–25 h from the maximal values of FITC/APC MFI of the sample incubated at 37°C for 0 h.

Cytotoxicity assay

The 4-h 51Cr-release cytotoxicity assay was performed as described previously [32]. NKL or RL12 effector NK cells (1.5×105, 0.75×105, or 0.375×105) were mixed in quadruplicates in U-bottom microwell cell culture clusters (Costar, Corning, NY, USA) with 5 × 103 cells/well 51Cr-pulsed GD2+ M21 or GD2– K562 target cells in 30:1, 15:1, or 7.5 E:T ratios, respectively, in complete RPMI-1640 medium (without HS), with or without 1 μg/ml hu14.18 antibody, 3000 U/ml IL-2, 1 μg/ml hu14.18 antibody + 3000 U/ml IL-2, 1 μg/ml hu14.18-IL2 IC, or 1 μg/ml hu14.18-IL2 IC + 3000 U/ml IL-2. Under certain experimental conditions, effector or target cells were pre-armed with hu14.18-IL2 IC, as described above, prior to using in the cytotoxicity assay. In other experiments, 1 × 105/ml NK cells were preincubated on ice with 10 μg/ml anti-CD25 mAb (anti-TAC, mouse IgG1, clone GL439) for 1 h, followed by two washings with ice-cold PBS, prior to being admixed with the tumor target cells. After the cells were mixed in wells, the loose pellets were formed by 5 min centrifugation at 500 rpm, followed by incubation of the pelleted cells for 4 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. After 4 h incubation, the supernatant was harvested using the Skatron harvesting system (Skatron, McLean, VA, USA), and cytotoxicity values (%) were calculated at each E:T ratio, as reported previously [33].

In vivo tumor model and IT treatment

Eight- to 10-week-old CB.17/SCID mice (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Madison, WI, USA) were housed, cared for, and used in accordance with the 1985 Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health Publication 86-23, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

M21 cells (5×106/0.1 ml) were implanted s.c. into abdominal flank, and tumor growth was monitored. On Day 27, when average tumor size was 200–250 mm3 (7–9 mm in diameter), the animals were divided randomly into three groups (n=3/group) and treated IT with 3 daily injections of 50 μl PBS (PBS×3, Group 1), 2 days of 50 μl PBS and 1 with 10 μg hu14.18-IL2 IC/0.05 ml PBS (PBS×2/IC×1, Group 2), or 3 consecutive daily injections of 10 μg IC/0.05 ml PBS (IC×3, Group 3). Immediately after the last injection of PBS (Group 1) or IC (Groups 2 and 3), all mice were injected i.v. with 5 × 106/0.2 ml BODIPY-labeled NKL cells. Twenty-four hours after NKL cell injection, the animals were killed, and the tumors were harvested and processed to a single-cell suspension. The resultant cell samples from each mouse were tested by flow cytometry for prevalence of resident CD49B+ NK cells and implanted BODIPY+ NKL cells, as well as for the presence of hu14.18-IL2 on the surface of tumor-infiltrating NK cells or tumor cells/nontumor stroma cells.

Statistical analysis

A two-tailed Student's t test was used to determine significance of differences between experimental and relevant control values within one experiment.

RESULTS

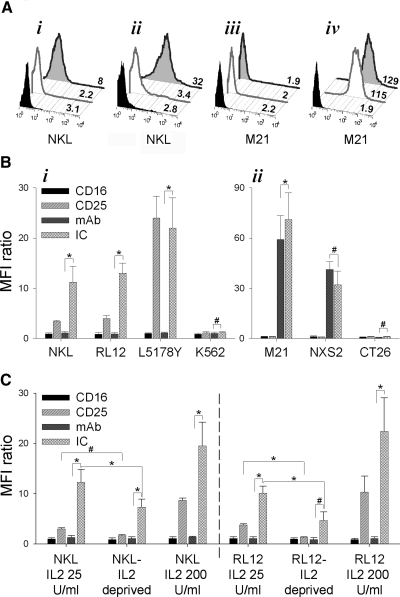

Cell immunophenotype determines specificity of mechanism of hu14.18-IL2 IC binding

The hu14.18-IL2 IC can bind to the cells expressing GD2 antigen, via its antigen-binding site. It also can bind to cells expressing IL-2Rs, via its Fc region-bound IL-2 molecule, just as it can bind to cells expressing FcRs, via the Fc region of the mAb. To analyze potential interactions of IC with the effector and target cells used in this study, we first determined the GD2, FcR, and IL-2R phenotype of two human NK cell lines, NKL and RL12, as well as two tumor cell lines—human M21 melanoma and mouse NXS2 NB (Fig. 1). Both of the NK cell lines constitutively express high levels of CD25 (IL-2Rα chain) but very low levels of CD16 (FcRγIII; Fig. 1A and B), and neither expresses GD2. In contrast, neither M21 nor NXS2 cells express CD25 or CD16, but both are recognized by the hu14.18 mAb, demonstrating their GD2 expression. Hence, NKL, RL12, M21, and NXS2 cells all bind the hu14.18-IL2 IC (Fig. 1A and B). These findings suggest that hu14.18-IL2 IC binds to these NK cells via the high-affinity form of IL-2R containing CD25 and to tumor cells via GD2. CD25 specificity of hu14.18-IL2 IC was confirmed by separate analyses, where IC binding to NKL and RL12 cells was inhibited by preincubating them with anti-CD25 (anti-TAC) mAb (Gubbels et al., unpublished manuscript). Furthermore, the binding of the hu14.18 mAb to GD2+ tumor cells but not to CD25+ NKL or RL12 cells further confirms that hu14.18-IL2 IC binds to NKL and RL12 via CD25. Cells that do not express GD2, CD16, or CD25 (K562, Fig. 1B, i; CT26, Fig. 1B, ii) do not bind hu14.18 mAb or hu14.18-IL2 IC. The amount of hu14.18-IL2 IC (and hu14.18 mAb) bound to the cells correlated with the level of CD25 and GD2 expression (Fig. 1B). L5178Y cells, expressing the highest level of CD25 shown (Fig. 1B, i), bound more hu14.18-IL2 IC than did NKL or RL12 cells. Similarly, M21 cells, expressing more GD2 than NXS2 cells, bound more hu14.18-IL2 IC than did NXS2 cells (Fig. 1B, ii). The binding of hu14.18-IL2 to NK cells, expressing only the intermediate form of the IL-2R (i.e., unstimulated human donor PBMC-derived NK cells), was not studied. However, in a parallel study (Gubbels et al., unpublished manuscript), it has been demonstrated that another IC, KS-IL2 IC, can effectively facilitate conjugate formation between ovarian cancer cells and NK cells derived from PBMC of healthy donors and ovarian cancer patients. As most NK cells (PBMC-derived and human NK cell lines growing in vitro) express at least low levels of the intermediate-affinity receptor and proliferate in response to IL-2, it is possible that the amount of hu14.18-IL2 binding to CD122 needed to induce proliferation may be too small to detect using the flow cytometric methods used in this study.

Figure 1. Binding of hu14.18-IL2 IC and hu14.18 mAb is determined by a pattern of CD16, CD25, and GD2 expression on NK cells and tumor cells.

(A) Expression of CD16 (gray open peaks) and CD25 (gray filled peaks) versus staining with isotype IgG (black filled peaks) on NKL cells (i) and M21 cells (iii). Binding of hu14.18 mAb (gray open peaks) and hu14.18-IL2 IC (gray filled peaks) or isotype IgG (black filled peaks) to NKL cells (ii) or M21 cells (iv). Numbers represent geometric mean values of the MFI of the staining with specific or control IgG antibodies. (B) Comparison of binding of anti-CD16, anti-CD25, hu14.18 mAb, or hu14.18-IL2 IC by NKL, RL12, L5178Y, or K562 cells (i) or M21, NXS2, or CT26 cells (ii). Results are presented as mean ± se (n=4 independent experiments with similar design) of MFI ratios calculated by using geometric mean values of the MFI as described in Materials and Methods. *P < 0.05; #P > 0.05. (C) Comparison of binding of anti-CD16, anti-CD25, hu14.18 mAb, or hu14.18-IL2 IC by NKL or RL12 cells grown in 25 U IL-2/ml, deprived of IL-2 for 24 h or cultured in 200 u/ml for 7 days prior to staining. Results are presented as MFI ratios. Results are presented as mean ± se (n=3 independent experiments with similar design) of MFI ratios calculated by using geometric mean values of the MFI as described in Materials and Methods. *P < 0.05; #P > 0.05.

As levels of CD25 expression can be modulated by exposure to exogenous IL-2 [34], we next tested if different cell culture conditions would affect the level of hu14.18-IL2 IC binding to NKL and RL12 cells (Fig. 1C). NKL and RL12 cells, grown under our standard in vitro conditions in medium supplemented with 25 U/ml IL-2, were grown for 7 days in the presence of high IL-2 concentration (200 U/ml) or were IL-2-deprived for 24 h prior to testing for CD16/CD25 expression and hu14.18-IL2 IC binding. As shown, culturing in the presence of 200 U/ml, IL-2 up-regulated CD25 expression on NK cells as well as augmented the capacity to bind hu14.18-IL2 IC, whereas IL-2 deprivation led to down-regulated CD25 expression and decreased IC binding, especially for RL12 cells (Fig. 1C).

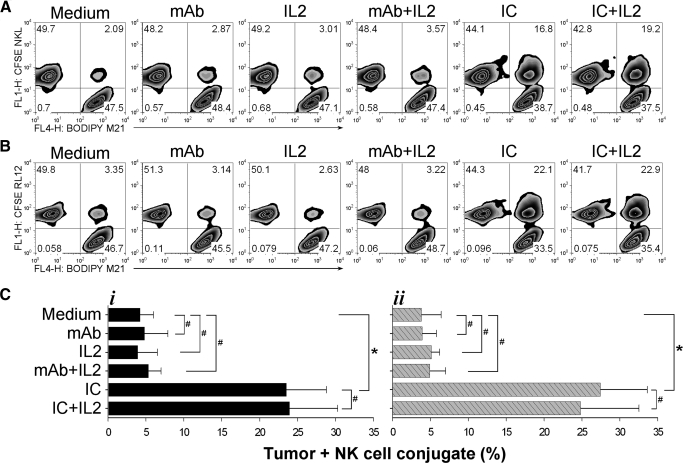

hu14.18-IL2 IC facilitates conjugation of NK with GD2+ tumor cells resulting in tumor cell lysis

We have found recently that hu14.18-IL2 IC facilitates the conjugation of fresh PMBC-derived NK cells to GD2+ tumor cells and that these conjugates exhibited a polarized immune synapse facilitated by the IL-2Rs of the effector cells (unpublished results). Here, we tested the cytotolytic activity of these IC-facilitated conjugates. We first confirmed that hu14.18-IL2 IC facilitated conjugate formation between NKL and GD2+ M21 cells (Fig. 2A) and demonstrated that a similar result is obtained with the RL12 cells (Fig. 2B). In medium alone, only ∼2% of the mixed cells were engaged in formation of conjugates that involved at least one tumor cell and one NK cell (upper right quadrant on each histogram, Fig. 2A and B). Incubating the cells in the presence of hu14.18 mAb or IL-2, alone or in combination, did not significantly increase the number of cells forming heteroconjugates. In contrast, the presence of hu14.18-IL2 IC led to formation of conjugates (involving 17–22% of the events detected by flow cytometry) within the first 30 min of incubation (Fig. 2). Addition of exogenous IL-2, similarly to the control setting of hu14.18 mAb + IL-2 at 3000 U/ml did not visibly interfere with the process of functional conjugation facilitated by hu14.18-IL2 IC. Separate analyses have shown that these conjugates are mediated through the high-affinity IL-2Rs of the effector cells, as anti-CD25 (anti-TAC) mAb dramatically inhibits conjugate formation (Gubbels et al., unpublished manuscript). When NKL or RL12 cells were tested for conjugate formation with GD2– K562 cells, no significant differences between hu14.18 mAb and hu14.18-IL2 IC were observed, and only 3–5% of the cells formed conjugates (unpublished results). Fig. 2C (i, M21+NKL; ii, M21+RL12) summarizes results of three experiments performed under identical conditions.

Figure 2. IC facilitates conjugation of NK and tumor cells in vitro.

BODIPY 630/650-labeled M21 cells (1.5×105/0.1 ml) and CFSE-labeled NKL (A, 1.5×105/0.1 ml) or RL12 (B, 1.5×105/0.1) cells were mixed together in sample tubes in complete RPMI-1640 medium, with or without 1 μg/ml hu14.18 mAb, 3000 U/ml rIL-2, 1 μg/ml hu14.18 mAb + 3000 U/ml rIL-2, 1 μg/ml hu14.18-IL2 IC, or 1 μg/ml hu14.18-IL2 IC + 3000 U/ml rIL-2, and a loose pellet was formed by centrifugation at 100 rpm/0.5 min, followed by incubation of the pelleted cells for 30 min in a 37°C water bath. After 30 min of incubation, the pellet was agitated gently, and the cells were tested by flow cytometry for M21-NK cell conjugate formation. The numbers in each quadrant indicate the percentage of events: single NK cells (left upper quadrant), single M21 cells (right lower quadrant), and conjugates containing at least one M21 cell and one NK cell (right upper quadrant). (C) Summary of NKL (i) and RL12 (ii) effector cells plus M21 tumor cell conjugate formation experiments (n=3). The assays were performed as described above and in Materials and Methods. Results are presented as mean ± se of percentage of total number of cells, mixed in a 1:1 E:T ratio, involved in conjugates as opposed to single cells by using geometric mean values of the MFI. *P < 0.05; #P > 0.05.

Mixing NKL effectors with M21 targets in the presence of IC at a 1:1 E:T ratio led to formation of conjugates between ∼28% of mixed NKL and M21 cells (Fig. 3B) and involving 45% (Fig. 3C) of total M21 cells during the first 30 min of the assay. We asked if increasing the E:T ratio would increase the percentage of M21 cells that were conjugated with effector cells. At the 3.75:1 E:T ratio, >80% of the M21 cells were bound to NKL cells (Fig. 3B and C), and 90% of the M21 cells were bound to NKL cells at the 7.5:1 E:T ratio. At the ratios of 15:1 and 30:1, >95% and 99% of M21 cells, respectively, were conjugated to NKL cells (Fig. 3C). Similar results were found with RL12 cells (data not shown). In contrast, the percentage of M21 cells involved in conjugates in the presence of hu14.18 mAb was <16%, even at the 15:1 and 30:1 E:T ratios (Fig. 3A and C).

Figure 3. Increasing E:T ratio increases percentage of M21 cells in conjugates.

NKL cells (1.5×105/0.1 ml) were mixed with 1.5, 0.4, 0.2, 1, or 0.050 × 105/0.1 ml M21 cells to achieve E:T ratios of 1:1, 3.75:1, and 7.5:1 (A and B) or 15:1 and 30:1 (C; not shown in A and B) ratios. These mixtures were cultured in medium with 1 μg/ml hu14.18 mAb (A) or hu14.18-IL2 IC (B), and conjugates were allowed to form at 37°C. After 30 min of incubation, the pellets were resuspended gently and tested by flow cytometry for M21-NK cell conjugate formation. Conjugates were scored as in Fig. 2. (C) For the purpose of calculating the distribution of M21 cells that were conjugated to NKL cells versus free (unconjugated) M21 cells, the following calculations assume that each event seen by flow cytometry represents a single M21 cell, a single NKL cell, or a conjugate consisting of one M21 and one NKL cell. However, it remains possible that some of the events detected by flow (particularly in the right upper quadrant) may have more than a single M21 or single NKL cell. The percentage of M21 cells in conjugates = 100% – [(x/y)×100%], where x is the absolute number of unbound M21 cells calculated from the percentage of events in lower right quadrants in A and B, and y is the absolute number of total M21 cells mixed with NKL cells prior to adding hu14.18 mAb or hu14.18-IL2 IC. The results are representative of two independent experiments.

In the next series of experiments, NKL (Fig. 4A, i and iii) and RL12 (Fig. 4A, ii and iv) cells were tested for killing of the GD2+ M21 (Fig. 4A, i and ii) and the GD2– K562 (Fig. 4A, iii and iv) cells. Greater cytotoxicity was mediated against M21 cells in the presence of hu14.18-IL2 IC as compared with hu14.18 mAb. Adding equivalent amounts of IL-2 with hu14.18 mAb did not enhance target lysis. In contrast, comparable killing was seen on K562, regardless of whether hu14.18-IL2 or hu14.18 mAb + IL-2 was added. M21 tumor cell lysis was markedly inhibited when effector cells, NKL (Fig. 4B, i) or RL12 (Fig. 4B, ii), were precoated with anti-CD25 (anti-TAC) mAb prior to being admixed with the M21 tumor cells. This suggests that conjugation of NK cell effectors with tumor cell targets, facilitated by mAb-IL2 IC, augmented cytotoxicity and requires interaction of IC and the IL-2R present on effectors.

Figure 4. IC facilitates NK-mediated cytotoxicity in vitro.

NKL (A, i and iii) or RL12 (A, ii and iv) cells, grown in medium supplemented with 25 U/ml IL-2, were tested for cytotoxicity against 5 × 103 M21 (i and ii) or K562 (iii and iv) in the presence of 1 μg/ml hu14.18 mAb, 3000 U/ml rIL-2, 1 μg/ml hu14.18 mAb + 3000 U/ml IL-2, or 1 μg/ml hu14.18-IL2 IC, as described in Materials and Methods. Results are presented as percent cytotoxicity mediated at different E:T ratios and are representative of at least two independent experiments. (B) NKL (i) or RL12 (ii) cells were tested for cytotoxocity against 5 × 103 M21 cells in the presence of 1 μg/ml hu14.18 mAb or 1 μg/ml hu14.18 mAb + 3000 U/ml IL-2 after some NKL and RL12 cells had been precoated with excess (10 μg/ml) anti-CD25 (anti-TAC) mAb for 1 h. This experiment was performed one time.

Differential stability of hu14.18-IL2 IC binding to GD2– CD25+ NK cells and GD2+CD25– tumor cells reflects differential IC internalization

The half-life of high-affinity IL-2R expression on the cell surface is 10–20 min [18, 20]. Shortly after IL-2 binding, the IL-2–IL-2R complex becomes internalized, and this process seems to be independent from the presence of IL-2 in the microenvironment but rather depends on temperature [19]. The IL-2 molecule as well as β- and γ-chains of IL-2R are then degraded, whereas the α-chain (CD25) is recycled to the cell surface. At 37°C, >50% of IL-2 bound to high-affinity IL-2Rs becomes internalized within the first 10–20 min and >80% by 1 h [18–20, 35].

Similarly, mAb that recognize membrane surface antigens can be internalized, shed, or remain relatively stable on the cell surface. This process is also temperature- and cell type-dependent and is affected by character and membrane location of the antigen as well as the class of mAb recognizing it. As the gangliosides expressed by tumor cells are relatively stable membrane components, antibodies that bind to them may remain on the cell surface for a longer period of time with slow shedding or internalization [26, 27].

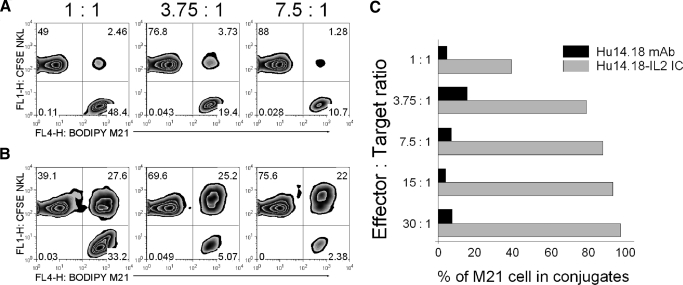

As hu14.18-IL2 IC is a bispecific fusion protein that binds to the GD2 and IL-2Rs (Fig. 1), the fate of the IC, once bound to GD2+ M21 cells or NK cells, was investigated (Fig. 5). We hypothesized that at least three potential possibilities could occur: hu14.18-IL2 IC internalization, stable binding of IC, or loss of surface-bound IC via shedding without internalization.

Figure 5. Kinetics of hu14.18-IL2 IC internalization by GD2+ tumor cells and CD25+ lymphoid cells.

(A) Three alternative possible patterns for the anticipated retention (%) of FITC (bound to hu14.18-IL2 IC) or APC (bound to secondary goat antibody against human IgG) in the hypothetical case of complete internalization (i), complete stable surface binding (ii), and complete loss as a result of shedding (iii) over a 24-h period for the hu14.18-IL2 IC bound to the surface of CD25+ cells. Previously published data about analysis of IL-2R internalization were used to generate these three hypothetical plots. (B) hu14.18-IL2 IC-FITC-armed NKL (i and ii) or M21 (iii and iv) cells (3×106/0.1 ml) were cultured for 0–24 h at 37°C. After 0–24 h, the cells were labeled with G-α-H IgG-APC to detect any IC-FITC still present on the surface. The double-labeled cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for FITC (i and iii) and APC (ii and iv). The numbers shown are MFI geometric mean values at 0 h (black open peaks) or 24 h (gray filled peaks). Black filled peaks demonstrate the FITC signal from control IgG-FITC (rather than IC-FITC; i and iii) or the APC signal from the IgG-FITC-labeled cells developed with G-α-H IgG-APC (ii and iv). (C) Comparison of time-dependent alterations of FITC (i–iii) and APC (iv–vi) dual fluorescence over 24 h for cells pre-armed with hu14.18-IL2-FITC and stained at the indicated times with G-α-H IgG-APC. NKL (i and iv) and RL12 (ii and v) NK cells grown in different culture conditions prior to IC-arming (the legend box in iv clarifies the IL-2 culture conditions used for the cells shown in i, ii, iv, and v). Tumor cells (GD2–CD25+ L5178Y T cell lymphoma, GD2+CD25– M21, and GD2+CD25– NXS2) are shown in iii for FITC and in vi for APC. Results are representative of at least four independent experiments and expressed as percent of fluorescence retention at 0.5, 1, 6, 12, and 24 h (compared with 0 h=100%) after IC-arming of the cells.

To address this hypothesis, we used FITC-labeled hu14.18-IL2 IC (IC-FITC) as well as APC-labeled secondary polyclonal G-α-H IgG antibody (IgG-APC), which would recognize human IgG (IC) specifically but not other proteins. M21, NKL, and RL12 cells were pre-armed on ice with saturating concentrations of FITC-labeled hu14.18-IL2 IC, and excess IC was washed out. The amount of IC present on the cell surface at this time (time-point 0 h) should correspond to 100% of the IC bound to the cell. Thus, the amount of IC-FITC detected on the cell surface by FITC detection and the amount of IC on the cell surface detected by the secondary anti-human IgG-APC reagent, at time = 0, were defined as 100% for FITC and APC.

In the case of IC-FITC internalization, FITC would presumably be retained in the cells (but not on the surface) without significant FITC metabolism and quenching [36]. If all of the IC were internalized, the amount of human IgG (IC-FITC) available on the cell surface for recognition by the anti-IgG-APC would become absent, resulting in reduction of APC fluorescence of the cells with internalized IC-FITC. A diagram showing the hypothetical pattern for the anticipated FITC/APC fluorescence decline under the circumstances of complete hu14.18-IL2 IC internalization is shown in Fig. 5A, i. Previously published data about the kinetics of IL-2–IL-2R complex internalization [18, 20] were used as a model.

In the hypothetical case of complete stable binding of hu14.18-IL2 IC to the cell surface (no shedding or internalization), most of the cell surface-bound IC-FITC would still be available for detection with anti-IgG-APC, and thus, no decline in FITC or APC fluorescence would be anticipated. A diagram showing this pattern for the anticipated FITC/APC fluorescence is presented in Fig. 5A, ii. Should all of the cell surface-bound IC-FITC be shed, there would be a reduction of FITC fluorescence. As less IC-FITC would be available for recognition with IgG-APC, the APC fluorescence will also decrease. This hypothetical pattern is presented in Fig. 5A, iii.

First, we tested our hypothesis by comparing FITC and APC fluorescence of NKL (Fig. 5B, i and ii) and M21 (Fig. 5B, iii and iv) cells at 0 and 24 h after pre-arming the cells with hu14.18-IL2 IC. NKL and M21 cells retained 75–85% of FITC fluorescence after being in culture for 24 h, indicating that most of the FITC-labeled hu14.18-IL2 had been retained on the surface or internalized, rather than being shed. In contrast, the anti-human IgG-APC fluorescence of NKL cells had diminished dramatically (from 330 MFI at 0 h to 12 MFI at 24 h), indicating that most of surface-bound IC-FITC had been internalized. At 24 h, the M21 cells still retained most of their IgG-APC signal (2340 MFI at 0 h and 1588 MFI at 24 h), indicating that most of their IC-FITC was retained on the surface.

Next, we evaluated the kinetics of IC cell surface retention and internalization for IL-2-dependent GD2–CD25+ NKL (Fig. 5C, i and iv) and RL12 (Fig. 5C, ii and v) NK cells and IL-2-independent GD2–CD25+ L5178Y T lymphoma cells (Fig. 5C, iii and vi) and for two CD25–GD2+ tumor cell lines M21 and NXS2 (Fig. 5C, iii and vi), based on analysis of reduction of FITC (Fig. 5C, i–iii) and APC (Fig. 5C, iv–vi) signals. We additionally tested whether modulations in the growth conditions of NK cells (increased IL-2 concentration in medium or IL-2 deprivation, as shown in Fig. 1C) have an impact on the stability of hu14.18-IL2 IC binding to the cell surface. Although NKL and RL12 cells grown in the presence of high concentrations of IL-2 (200 U/ml) bind more IC at Time 0 h (Fig. 1C), we observed no significant difference in the rate of hu14.18-IL2 IC internalization by these cells as compared with the cells propagated in standard (25 U/ml) IL-2 concentrations: at 6 h, IC-FITC fluorescence was almost unchanged from the levels detected at Time-point 0 h, whereas anti-IgG-APC fluorescence declined by 60–75% at 6 h. Likewise, no significant difference in the kinetics of hu14.18-IL2 IC internalization was found when cells were deprived of IL-2 prior to pre-arming with IC, although a reduction of the amount of IC bound to the cells at 0 h was noted and likely reflected down-regulation of CD25 expression. Similar results were documented for NKL (Fig. 5C, i and iv) and RL12 (Fig. 5C, ii and v) cells. The IL-2-dependence status [IL-2-independent CD25+ L5178Y (Fig. 5C, iii and vi) cells vs. IL-2-dependent CD25+ NKL (Fig. 5C, i and iv) and CD25+ RL12 cells (Fig. 5C, ii and v)] also had no detectable impact on the kinetics of hu14.18-IL2 IC internalization; the pattern seen for L5178Y is similar to that seen for NKL and RL12. In contrast, CD25–GD2+ tumor cells, M21 and NXS2 (Fig. 5C, iii and vi), lost <30% of their surface-bound hu14.18-IL2 IC over the 24-h culture at 37°C (as measured by APC fluorescence). Hence, it appears that effectors and targets can internalize the surface-bound IC when incubated at 37°C, but this effect is mediated more rapidly via IL-2Rs than by GD2.

Internalization of IC by NK cells modulates their effector function

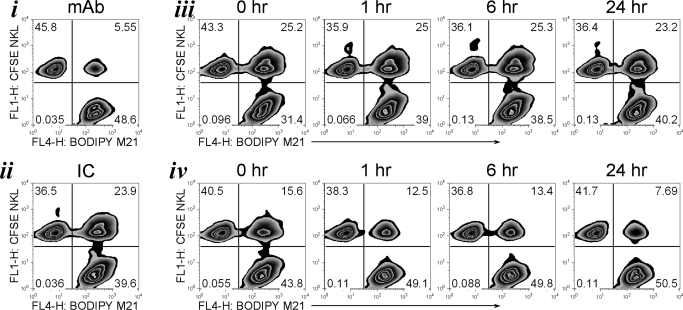

To test if internalization of surface-bound hu14.18-IL2 IC had an effect on the ability of IC-armed cells (effectors or targets) to form conjugates (Fig. 6), NKL cells (Fig. 6, iv) or M21 cells (Fig. 6, iii) were pre-armed with hu14.18-IL2 IC, washed, and cultured for 1, 6, or 24 h prior to being tested in the conjugate formation assay. As a control, cells were allowed to form conjugates in the continued presence of hu14.18 mAb (Fig. 6, i) or hu14.18-IL2 IC (Fig. 6, ii), or immediately after (i.e., at Time-point 0 h) the cells were pre-armed with hu14.18-IL2 IC. As expected, NKL and M21 cells formed more conjugates in the continuous presence of IC but not mAb (Fig. 6, i and ii). Although we found a slight reduction in the amount of IC on the surface of M21 cells over time while incubated at 37°C, this did not affect their ability to become engaged with IC-unarmed NKL cells (Fig. 6, iii), as the percentage of conjugates formed with M21 cells 24 h after pre-arming was almost the same as for the cells that were pre-armed 0, 1, and 6 h before the assay. In contrast, NKL cells pre-armed with IC formed fewer conjugates even at Time 0 than the pre-armed M21 cells (Fig. 6, iv, vs. Fig. 6, iii, at 0 h), likely reflecting the lower amount of IC that binds to NKL as compared with M21 (Figs. 1A and 4B). After the pre-armed NKL were incubated at 37°C for 1, 6, or 24 h, further decreases were seen in their ability to form conjugates; at the 24-h time-point, the percent of conjugates was similar to the number of conjugates formed in the presence of hu14.18 mAb (7.7% vs. 5.6%, respectively). Hence, rapid internalization of hu14.18-IL2 IC by pre-armed NK cells (Fig. 5C, i, ii, iv, and v) can diminish their ability to subsequently link to tumor cells, whereas pre-armed tumor cells can still be targeted effectively by NK cells, even 24 h after IC binding to the tumor cell surface.

Figure 6. IC internalization decreases M21 tumor cell–NK cell conjugate formation.

BODIPY630/650-labeled M21 cells and CFSE-labeled NKL cells were tested for conjugate formation 0, 1, 6, or 24 h after the M21 (iii) or NKL (iv) cells were pre-armed with hu14.18-IL2 IC and then washed. As a control, M21 and NKL cells were tested for conjugate formation in the continued presence of 1 μg/ml hu14.18 mAb (i) or hu14.18-IL2 IC (ii). The figure is representative of four independent experiments with similar results.

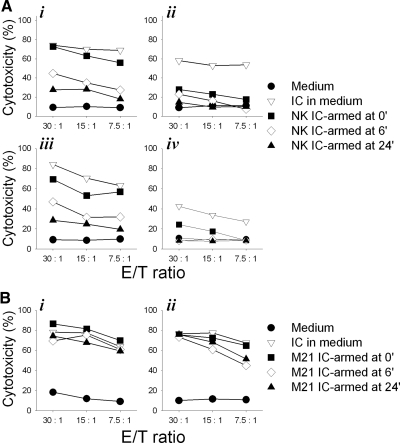

To test if internalization of IC by pre-armed NK cells impacts the hu14.18-IL2 IC-facilitated cytotoxicity, pre-armed NKL (Fig. 7A, i and ii) and RL12 (Fig. 7A, iii and iv) cells were tested for lysis of GD2+ M21 (Fig. 7A, i and iii) or GD2– K562 (Fig. 7A, ii and iv) cells at different time-points after IC-arming. The results suggest that immediately after the arming (0 h), NKL and RL12 cells could effectively lyse M21 cells at a level similar to that observed when hu14.18-IL2 IC was continuously present in the medium. The cytotoxicity levels were reduced at all E:T ratios by ∼50% and ∼75% at the 6-h and 24-h time-points, respectively (Fig. 7A, i and iii). Full recovery of cytotoxicity by the 24-h IC-pre-armed NKL (or RL12) cells could be achieved if 1 μg/ml exogenous hu14.18-IL2 IC were added to the culture (unpublished results). As noted in Fig. 3, no augmented cytotoxicity against K562 cells by IC-armed NK cells was mediated (Fig. 7A, ii and iv).

Figure 7. IC internalization decreases NK cell-mediated M21 tumor cell killing.

(A) hu14.18-IL2 IC-pre-armed NKL (i and ii) and RL12 (iii and iv) cells were tested for lysis of 51Cr-pulsed M21 (i and iii) and K562 (ii and iv) cells at 0, 6, and 24 h after NK cell pre-arming with IC or in the continued presence of 1 μg/ml hu14.18-IL2 IC (IC in medium). (B) NKL (i) or RL12 (ii) cells were tested for lysis of IC-armed, 51Cr-pulsed M21 melanoma cells at 0, 6, and 24 h after the M21 tumor cell hu14.18-IL2 IC-arming or in the continued presence of 1 μg/ml hu14.18-IL2 IC. The figure is representative of two independent experiments with similar results.

In contrast to the pre-armed NK cells, IC-armed M21 cells were lysed efficiently by unarmed NKL (Fig. 7B, i) and RL12 (Fig. 7B, ii) cells at any of the time-points after the arming, regardless of the loss of some of the hu14.18-IL2 IC from the cell surface (Fig. 5C, iii and vi). These results are consistent with the results shown in Fig. 6, iii, where efficient conjugate formation at all time-points was documented. Although the level of cytotoxicity seen in Fig. 7A, ii and iv, on K562 appears enhanced by IC and likely reflects NK stimulation by the IL-2 component of IC, this was not always reproducible; in four separate experiments (not shown), this difference was not significant (P>0.10).

hu14.18-IL2 IC preferentially binds to targets in a mixture of tumor and NK cells

hu14.18-IL2 IC effectively mediates conjugation of tumor cells with NK cells when continuously present in medium (Fig. 2), although the MFI of IC binding to NK cells is less than to tumor cells (Fig. 1), and IC is internalized more rapidly by NK cells than by tumor cells (Fig. 5). To potentially simulate the in vivo setting of IC administration, we tested the binding of hu14.18-IL2 IC to a mixture of unarmed M21 tumor cells and NK cells at 37°C.

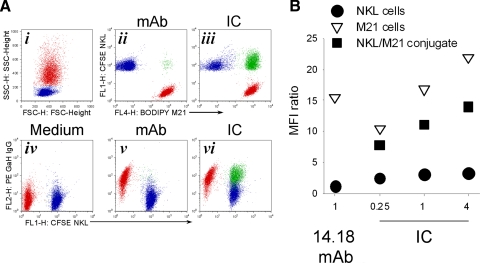

NKL (1.5×105; Fig. 8A, i, blue population) and 1.5 × 105 M21 cells (Fig. 8A, i, red population) were mixed in a 1:1 E:T ratio in the presence of 1 μg/ml hu14.18 mAb (Fig. 8A, ii and v) or hu14.18-IL2 IC (Fig. 8A, iii and vi), and conjugates (Fig. 8A, ii, iii, v, and vi, green population) were allowed to form at 37°C for 30 min. Cell surface-bound hu14.18 mAb and IC were detected with anti-human IgG mAb similar to the strategy in Fig. 5 (Fig. 8A, iv–vi). Cells kept in medium alone (no mAb or IC) were used as a control (Fig. 8A, iv). Distribution of hu14.18 mAb and hu14.18-IL2 IC on single, i.e., unconjugated cells (red, M21; blue, NKL), as well as on M21/NKL conjugates (green), is shown in Fig. 8A, v and vi. We found that hu14.18 mAb and hu14.18-IL2 IC were bound to unconjugated M21 cells (Fig. 8A, v and vi). The hu14.18-IL2 IC was also bound to M21/NKL cell conjugates (Fig. 8A, vi). NKL cells were stained negatively for hu14.18 mAb (Fig. 8A, v) and only weakly positive for hu14.18-IL2 IC (Fig. 8A, vi).

Figure 8. Binding of IC to GD2+ tumor cells and CD25+ NK cells involved in conjugates versus those not conjugated.

(A) BODIPY-labeled M21 cells (1.5×105; i–vi, red color population) were mixed with 1.5 × 105 CFSE-labeled NKL cells (i–vi, blue color population) in a 1:1 E:T ratio in medium alone (i and iv) or in the presence of 1 μg/ml hu14.18 mAb (ii and v) or 1 μg/ml hu14.18-IL2 IC (iii and vi). The forward (FSC)- and side (SSC)-scatter of the mixed population cultured with medium alone (no mAb or IC) are shown (i). Conjugates were allowed to form at 37°C for mixtures of NKL and M21 in medium, mAb, or IC. After 30 min of incubation, the cell mixtures were washed once with ice-cold PBS and stained with 1 μg/ml G-α-H IgG-PE for 40 min on ice. Based on gating for BODIPY and CFSE (ii for mAb; iii for IC; not shown for medium alone), cells were gated for unconjugated M21 cells (BODIPY+CFSE–, red population in i–vi), for unconjugated NKL cells (BODIPY–CFSE+, blue population in i–vi), and for conjugates (BODIPY+CFSE+, green population in ii, iii, v, and vi). These mixtures were then tested by flow cytometry for PE fluorescence (in iv, v, and vi) of the unconjugated M21 cells (red), unconjugated NKL cells (blue), and M21-NKL cell conjugates (green). (B) BODIPY-labeled M21 (1.5×105) and 1.5 × 105 CFSE-labeled NKL cells were mixed in a 1:1 E:T ratio in the presence of 1 μg/ml hu14.18 mAb or 0.25–4 μg/ml hu14.18-IL2 IC for 30 min at 37°C to allow conjugates to form. After 30 min of incubation, the cell mixtures were washed once with ice-cold PBS, stained with 1 μg/ml G-α-H IgG-PE for 40 min on ice, and then tested by flow cytometry for PE fluorescence. Results are presented as MFI ratio of PE fluorescence for the unconjugated M21 cells (BODIPY+CFSE–), for the unconjugated NKL cells (BODIPY–CFSE+), and for the conjugates themselves (BODIPY+CFSE+). The figure is representative of two independent experiments with similar results.

To further address the relative binding of mAb versus IC to the mixed M21 and NKL cells, we titrated concentrations of hu14.18-IL2 IC to ascertain that the IC concentration of 1 μg/ml was not a major limiting factor for the low binding of IC to the population of unconjugated NKL cells. At low (0.25 μg/ml) and high (4 μg/ml) hu14.18-IL2 IC concentrations, IC staining is far more prominent on unconjugated M21 cells (Fig. 8B, white triangles) and on M21/NKL cell conjugates (Fig. 8B, black squares), and smaller levels of IC are present on unconjugated NKL cells (Fig. 8B, black circles).

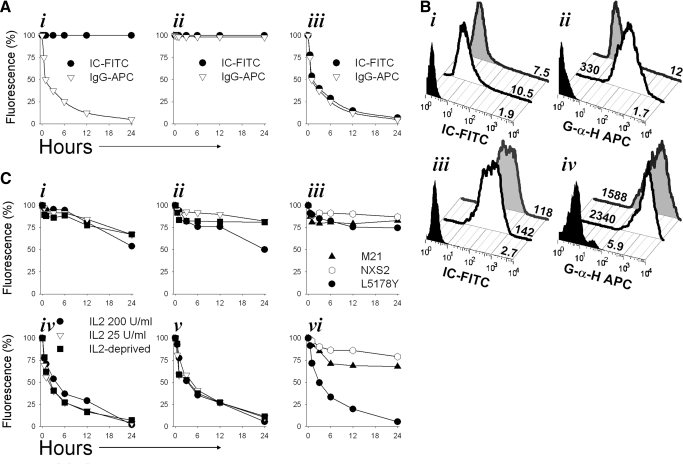

IT hu14.18-IL2 IC treatment results in migration of NK cells into the tumor

It was shown previously that systemic (i.e., i.v.) treatment with hu14.18-IL2 IC results in pronounced antitumor effects against mouse NXS2 NB [13], with even greater local and systemic effects obtained when the IC is delivered IT [16]. However, little is known about the ability of such IT treatment to facilitate migration of NK cells into the tumor. We evaluated this using an adoptive transfer xenograft model described previously [37].

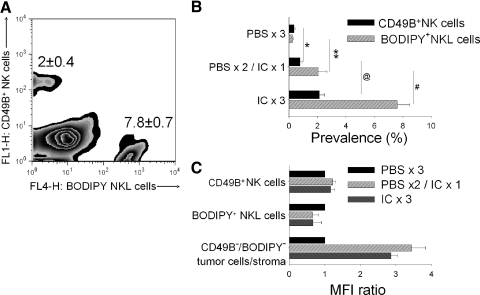

CB.17/SCID mice bearing s.c. human M21 melanoma tumors received one or three IT injections of 10 μg hu14.18-IL2 IC. To control for mechanic factors associated with IT injections, mice from the control group received three IT injections of 50 μl PBS. Immediately after the last PBS or IC treatment, all mice were adoptively transferred with 5 × 106 BODIPY-labeled NKL cells by i.v. injection. Twenty-four hours after NKL cell infusion, the tumors were harvested, processed into single-cell suspension, and evaluated for the presence of endogenous mouse CD49B+ NK cells, as well as the presence of BODIPY+ NKL cells. A representative sample from a mouse that received 3 daily i.c. treatments is shown in Fig. 9A. A summary of NK/NKL cell prevalence in the tumors from all mice in each of the three treatment groups is shown in Fig. 9B. The results suggest that even a single IT injection of hu14.18-IL2 IC induced migration of resident and adoptively transferred human NK cells into the tumor, and the effect of three IT IC treatments was greater than that of a single treatment (Fig. 9B). A single IT IC treatment was also marginally better at induction of NKL cell migration than a single i.v. treatment with the same amount of IC (unpublished results).

Figure 9. IT IC injection facilitates migration of NK cells into the tumor.

CB.17/SCID mice (n=12) bearing s.c. M21 human melanoma tumors were treated IT with PBS or IC on Days 27–29 of tumor growth. Group 1 received 50 μl PBS on Days 27–29 (PBS×3); Group 2 received 50 μl PBS on Days 27 and 28 and 10 μg IC in 50 μl PBS on Day 29 (PBS×2/IC×1); and Group 3 received 10 μg IC on Days 27–29 (IC×3). On Day 29, immediately after the last injection of PBS (Group 1) or IC (Groups 2 and 3), all mice were injected i.v. with 5 × 106/0.2 ml BODIPY-labeled NKL cells. On Day 30, 24 h after the NKL cell injection, the tumors were harvested and processed to a single cell suspension. The resultant cell samples from each mouse were counterstained with anti-CD49B-FITC, and samples were tested by flow cytometry for the prevalence of mouse resident CD49B+ NK cells and BODIPY+ NKL cells. A representative pattern of staining from a mouse that received 3 days of IT IC (IC×3) is shown (A). Numbers indicate the relative prevalence (%; mean±sem; n=3) of mouse resident CD49B+ NK cells and implanted BODIPY+ NKL cells of the IC × 3 group. A summary of results for each group of mice is shown (B). Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments. *P = 0.06; **P = 0.046; @P=0.02; #P=0.007. (C) The same tumor cell samples shown in B were also stained with 1 μg/sample G-α-H IgG-PE, which would bind specifically to the IC remaining on the tumor or effector cells, following the in vivo IT IC injections (for Groups 2 and 3). By gating on FITC or on BODIPY, it was possible to detect the IC bound to mouse resident CD49B+ NK cells, to adoptively transferred BODIPY+ NKL cells, as well as to the CD49B–/BODIPY– tumor/stroma cells. MFI of samples from the group that received no IC treatment (Group 1) were used as the reference control (defined as MFI ratio of 1.0). MFI values from the two other experimental groups were compared with the control group. The MFI ratios were calculated by dividing MFI values for each cell subset from groups that received IC treatment by the MFI value of that same cell subset from the control group that received no IC injections. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

We also asked whether IC was still present in the tumor 24 h after the last IT treatment and on which cells it might be bound. The single cell samples from the harvested tumors were labeled with secondary PE-conjugated polyclonal G-α-H IgG antibody, as well as with FITC-conjugated anti-murine NK mAb (anti-CD49B-FITC). The cells were analyzed for IC binding (PE staining) by gating on CD49B-FITC+ (murine NK cells), on BODIPY+ (human NK cells), or on FITC–BODIPY– cells (murine tumor and non-NK stromal cells) of the samples (Fig. 8A). We found that IC was detectable on the surface of FITC–BODIPY– cells (M21 tumor cells+non-NK stroma) and was not detectable on the surface of mouse resident CD49B+ NK cells or injected BODIPY+ human NK cells (Fig. 9C). The number of IC treatments (one vs. three) did not have a visible effect on the amount of IC present on FITC-BODIPY– cells (Fig. 9C).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we evaluated the stability of binding of IC to GD2+CD25–CD16– tumor cells and CD25+GD2–CD16– NK cells and evaluated in vitro the impact of IC internalization on the E:T conjugation and cytotoxicity processes. NK cells were found to internalize IC rapidly, similar to that described previously for soluble IL-2; this internalization did not depend on the amount of IC bound to the NK cell surface (Figs. 1B, i and ii, and 5C, i, ii, iv, and v), the concentration of exogenous IL-2 (Figs. 1C and 5C, i, ii, iv, and v) in the microenvironment, or overall IL-2 dependence of the CD25+ cells (Fig. 5C). Loss of IC from the cell surface of pre-armed NK cells resulted in a significant reduction in their capacity to form conjugates with (Fig. 6, iv) and kill (Fig. 7A) tumor cells. However, these functions were easily recovered by supplying additional hu14.18-IL2 into the mixed M21/NKL cell cultures (unpublished results). Although the effector cells evaluated here (NKL and RL12) express the high-affinity IL-2R (αβγ), it is possible that the kinetics of IC internalization by effectors expressing only intermediate-affinity IL-2R (βγ) may be different. Furthermore, concomitant CD16 expression by NK cells may substantially alter the process of internalization and cytotoxicity by enabling further binding of IC to the cell surface of effectors and by providing additional stimuli via activating FcγRIII. However, it appears that IC-facilitated cellular cytotoxicity can be mediated by CD25+ NK cells that lack expression of CD16, with CD25 serving as an anchoring and a stimulatory ligand. In contrast, the kinetics of IC internalization by GD2-positive tumor cells was considerably slower (Fig. 5C), as compared with NK cells; the stable surface binding of IC to these tumor cells allowed for efficient conjugation of IC-armed GD2+ tumor cells to IC-unarmed NK cells (Fig. 6, iii) and resulted in efficient tumor cell lysis (Fig. 7B).

Although the binding of hu14.18-IL2 IC to M21 cells is mediated by the GD2-specific tumor antigen recognition mAb component of IC, the ability of IC to facilitate E:T conjugate formation and tumor cell lysis (particularly by CD25+CD16– effectors) reflects the bispecific design of the IC molecule and its IL-2 components. Similar functional results, showing enhanced NKL-tumor cell conjugation, were demonstrated recently using a separate IC, the huKS-IL2 IC (Gubbels et al., unpublished manuscript), which specifically targets the KS1/4 (EpCAM) antigen expressed on lung [38], ovarian [39], colon, and other adenocarcinomas [40]. Conjugate formation between GD2+ M21 cells or KS+ OVCAR ovarian carcinoma cells and CD25+ NK effectors (NKL or RL12 cells), facilitated by hu14.18-IL2 IC or huKS-IL2 IC, respectively, was markedly inhibited by pretreating NK cells with anti-CD25 (anti-TAC) mAb (Gubbels et al., unpublished manuscript). IC target-specificity was shown by the absence of effector-tumor conjugate formation between NKL and M21 (GD2+EpCAM–) cells in the presence of saturating concentrations of huKS-IL2 IC (Gubbels et al., unpublished manuscript). Most importantly, within the NKL-tumor cell conjugates, the IC bound to the surface of the tumor cells remained evenly distributed all over the tumor cell surface, and the IC and CD25 molecules on the surface of the NKL cells copolarized to the active immune synapse at the junction of the NKL and tumor cell (Gubbels et al., unpublished manuscript). These studies indicate that the high-affinity IL-2R, upon encountering cell-bound IL-2 (as IC bound to tumor cell), functions as a potential adhesion molecule, as well as a signaling molecule, and participates in activated immune synapse formation. Prospective studies with human NK cells, resting and IL-2-activated, will address the conjugate formation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine profile of patient effectors ex vivo.

Despite ostensibly uniform binding of IC to NK and M21 cells within a sample (Fig. 1A), it was never possible to achieve 100% conjugation of all tumor cells with all NK cells when the cells were mixed at a 1:1 E:T ratio (Figs. 2 and 3). However, shifting the E:T ratio in favor of NK cells (Fig. 3) results in a greater percentage of the tumor cells becoming conjugated with the NK cells. This greater percentage of conjugation at higher E:T ratios is paralleled by better cytotoxicity (Fig. 4A). When E:T ratios were less than 1:1 (i.e., more tumor cells compared with effectors), only a fraction of tumor targets was conjugated with NK cells and resulted in diminished cytotoxicity (unpublished results). Many biological factors, such as overall density and character of surface distribution of additional adhesion receptor-ligand pairs on effectors and targets (i.e., NK-activating receptors, such as NKG2D, and its ligands), size of the cells, and others, may have a functional impact on the quantitative equilibrium of conjugation between the NK and tumor cells. Regardless of which effector line was evaluated in this study, the inclusion of the hu14.18-IL2 IC (vs. IL-2 alone, hu14.18 mAb alone, or the IL-2 and mAb together) unequivocally resulted in the highest level of conjugation formation between NKL or RL12 cells and the GD2+ tumor cells (Fig. 2).

Another aspect of IC biology was revealed by comparing the amount of IC bound to single M21 or NKL cells or to conjugated M21/NKL cells after 30 min of mixed cell pellet incubation at 37°C (Fig. 8). Cell-bound IC was predominantly targeted to tumor cells (Fig. 8A, vi, red cell population), rendering them vulnerable to killing by NK cells. In contrast, NK cells (Fig. 8A, vi, blue cell population) had a much smaller amount of IC on their surface. NKL/M21 cell conjugates (Fig. 8A, vi, green cell population) contained IC at a level comparable with the levels observed on unconjugated M21 cells. Increasing the concentration of IC in the culture medium (Fig. 8B) did not significantly alter the pattern of IC binding to the cells in the cell mixture, and M21 cells always demonstrated significantly greater binding of IC relative to NKL cells. Although this may reflect the greater cell-surface density of the GD2 antigen on M21 as compared with that of high-affinity IL-2Rs on the NK effectors, it is also possible that most IC bound to NKL cells at 37°C is internalized rapidly (Fig. 5) and no longer detectable.

As a potential in vivo correlate of our in vitro binding studies, we demonstrated that IT injections of hu14.18-IL2 IC in SCID mice resulted in augmented recruitment of NK cells into the tumor (Fig. 9A and B). In several preliminary experiments, we did not detect a significant influx of NK cells into the tumor when IC was administered i.v.; this likely reflects the nonoptimized conditions used. The number of adoptively transferred human NKL cells found in the tumor was greater for the animals receiving 3 daily IT injections than a single IT dose of IC. This effect required IC treatment, as injections of PBS in control animals did not induce active migration or passive extravasation (as a result of mechanical disturbance of the tumor) of resident mouse CD49B+ NK cells or adoptively transferred human BODIPY+ NKL cells. Interestingly, when the single cell preparations from the harvested tumors were tested for the presence of IC on the cell surface, the IC was found only on tumor cells but not on NK cells (Fig. 9C). It is possible that the tumor-infiltrating NK cells have rapidly internalized any IC bound to them after IT treatment, whereas the slower internalization kinetics of IC on the surface of tumor cells enabled its detection at the time of tissue harvest. It is unlikely that this increased number of NK cells in the tumors was a result of immunotherapy-induced tumor cytoreduction, as decreased tumor sizes were not observed during the 96 h of the experiment (unpublished results). However, we anticipate that continued (i.e., beyond 96 h) therapy with the combination of adoptively transferred NK effectors plus IT delivery of IC would result in even greater accumulation of NK cells in the tumor compartment, leading to immunotherapy-induced tumor cytoreduction.

The phenomena of differential internalization and surface labeling of tumor versus effector cells with IC may have some practical implications in the setting of in vivo treatment and may potentially relate to antitumor activity seen recently in the Phase II clinical setting [41]. In our preliminary experiments, we found that IC bound to the surface of pre-armed NKL cells did not facilitate their migration into the tumor once the IC-armed NKL cells were adoptively transferred into the systemic circulation of M21 tumor-bearing mice (unpublished results), possibly as a result of rapid IC internalization prior to NK cells reaching the tumor. In contrast, IT therapy with IC did facilitate recruitment of NK cells into the tumor compartment. Prior studies with radiolabeled IC show specific in vivo localization to tumor sites after i.v. injection of IC, with even greater amounts of IC localization to tumor sites after direct IT administration [16]. Despite the relatively short half-life of IC in the circulation after i.v. injection [10, 42, 43], the studies presented here suggest that once the IC gets to the tumor cells in vivo, it would appear to remain there for some time. The IC that remains on the tumor surface would then facilitate conjugate formation with NK effectors that express IL-2Rs, subsequently resulting in IC-mediated cytotoxicity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA032685, CA87025, CA14520, GM067386, and T32-CA090217 and grants from the Midwest Athletes for Childhood Cancer Fund, Crawdaddy Foundation, the Evan Dunbar Foundation, UW-Cure Kids Cancer Coalition, Abbie's Fund, St. Baldrick's Foundation, and Super Jake Foundation. I.N.B. is a lifetime member of the Association of Fellows of the International Union against Cancer (UICC; Geneva, Switzerland). The authors thank Mrs. Kathleen Schell for flow cytometry support and helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- APC

- allophycocyanin

- BODIPY

- 6-(((4,4-difluoro-5-(2-thienyl)-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-yl) styryloxy)acetyl) aminohexanoic acid

- EpCAM

- epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- G-α-H

- goat anti-human

- GD2

- GD2 disialoganglioside

- HS

- human serum

- hu14.18-IL2 IC

- humanized 14.18-IL2 immunocytokine

- IC

- immunocytokine

- IT

- intratumorally

- MFI

- mean fluorescence intensity

- NB

- neuroblastomas

AUTHORSHIP

I.N.B. and Z.C.N.: coprimary authors, intellectual contributors, study design, data acquisition, data analyses; J.G., M.S.P., and J.A.A.G.: intellectual contributors, study design; T.N.B.: intellectual contributor, study design, data acquisition; J.A.H., B.Y., and A.L.R.: intellectual contributors, study design, data analyses; R.A.R. and S.D.G.: intellectual contributors; and P.M.S.: principal investigator, coauthor, intellectual contributor, study design, data analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gillies S. D., Reilly E. B., Lo K. M., Reisfeld R. A. (1992) Antibody-targeted interleukin 2 stimulates T-cell killing of autologous tumor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 1428–1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Choi B. S., Sondel P. M., Hank J. A., Schalch H., Gan J., King D. M., Kendra K., Mahvi D., Lee L. Y., Kim K., Albertini M. R. (2006) Phase I trial of combined treatment with ch14.18 and R24 monoclonal antibodies and interleukin-2 for patients with melanoma or sarcoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 55, 761–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ritter G., Livingston P. O. (1991) Ganglioside antigens expressed by human cancer cells. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2, 401–409 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gilman A. L., Ozkaynak M. F., Matthay K. K., Krailo M., Yu A. L., Gan J., Sternberg A., Hank J. A., Seeger R., Reaman G. H., Sondel P. M. (2009) Phase I study of ch14.18 with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-2 in children with neuroblastoma after autologous bone marrow transplantation or stem-cell rescue: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 85–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lo Piccolo M. S., Cheung N. K., Cheung I. Y. (2001) GD2 synthase: a new molecular marker for detecting neuroblastoma. Cancer 92, 924–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheresh D. A., Rosenberg J., Mujoo K., Hirschowitz L., Reisfeld R. A. (1986) Biosynthesis and expression of the disialoganglioside GD2, a relevant target antigen on small cell lung carcinoma for monoclonal antibody-mediated cytolysis. Cancer Res. 46, 5112–5118 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang H. R., Cordon-Cardo C., Houghton A. N., Cheung N. K., Brennan M. F. (1992) Expression of disialogangliosides GD2 and GD3 on human soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer 70, 633–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lipinski M., Braham K., Philip I., Wiels J., Philip T., Goridis C., Lenoir G. M., Tursz T. (1987) Neuroectoderm-associated antigens on Ewing's sarcoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 47, 183–187 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mennel H. D., Bosslet K., Geissel H., Bauer B. L. (2000) Immunohistochemically visualized localization of gangliosides Glac2 (GD3) and Gtri2 (GD2) in cells of human intracranial tumors. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 52, 277–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. King D. M., Albertini M. R., Schalch H., Hank J. A., Gan J., Surfus J., Mahvi D., Schiller J. H., Warner T., Kim K., Eickhoff J., Kendra K., Reisfeld R., Gillies S. D., Sondel P. (2004) Phase I clinical trial of the immunocytokine EMD 273063 in melanoma patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 4463–4473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Osenga K. L., Hank J. A., Albertini M. R., Gan J., Sternberg A. G., Eickhoff J., Seeger R. C., Matthay K. K., Reynolds C. P., Twist C., Krailo M., Adamson P. C., Reisfeld R. A., Gillies S. D., Sondel P. M. (2006) A phase I clinical trial of the hu14.18-IL2 (EMD 273063) as a treatment for children with refractory or recurrent neuroblastoma and melanoma: a study of the Children's Oncology Group. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 1750–1759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lode H. N., Xiang R., Dreier T., Varki N. M., Gillies S. D., Reisfeld R. A. (1998) Natural killer cell-mediated eradication of neuroblastoma metastases to bone marrow by targeted interleukin-2 therapy. Blood 91, 1706–1715 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Neal Z. C., Yang J. C., Rakhmilevich A. L., Buhtoiarov I. N., Lum H. E., Imboden M., Hank J. A., Lode H. N., Reisfeld R. A., Gillies S. D., Sondel P. M. (2004) Enhanced activity of hu14.18-IL2 immunocytokine against murine NXS2 neuroblastoma when combined with interleukin 2 therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 4839–4847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee F. T., Rigopoulos A., Hall C., Clarke K., Cody S. H., Smyth F. E., Liu Z., Brechbiel M. W., Hanai N., Nice E. C., Catimel B., Burgess A. W., Welt S., Ritter G., Old L. J., Scott A. M. (2001) Specific localization, γ camera imaging, and intracellular trafficking of radiolabeled chimeric anti-G(D3) ganglioside monoclonal antibody KM871 in SK-MEL-28 melanoma xenografts. Cancer Res. 61, 4474–4482 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mårlind J., Kaspar M., Trachsel E., Sommavilla R., Hindle S., Bacci C., Giovannoni L., Neri D. (2008) Antibody-mediated delivery of interleukin-2 to the stroma of breast cancer strongly enhances the potency of chemotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 6515–6524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnson E. E., Lum H. D., Rakhmilevich A. L., Schmidt B. E., Furlong M., Buhtoiarov I. N., Hank J. A., Raubitschek A., Colcher D., Reisfeld R. A., Gillies S. D., Sondel P. M. (2008) Intratumoral immunocytokine treatment results in enhanced antitumor effects. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 57, 1891–1902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wagner K., Schulz P., Scholz A., Wiedenmann B., Menrad A. (2008) The targeted immunocytokine L19-IL2 efficiently inhibits the growth of orthotopic pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 4951–4960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duprez V., Dautry-Varsat A. (1986) Receptor-mediated endocytosis of interleukin 2 in a human tumor T cell line. Degradation of interleukin 2 and evidence for the absence of recycling of interleukin receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 15450–15454 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fujii M., Sugamura K., Sano K., Nakai M., Sugita K., Hinuma Y. (1986) High-affinity receptor-mediated internalization and degradation of interleukin 2 in human T cells. J. Exp. Med. 163, 550–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lowenthal J. W., MacDonald H. R., Iacopetta B. J. (1986) Intracellular pathway of interleukin 2 following receptor-mediated endocytosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 16, 1461–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hatakeyama M., Mori H., Doi T., Taniguchi T. (1989) A restricted cytoplasmic region of IL-2 receptor β chain is essential for growth signal transduction but not for ligand binding and internalization. Cell 59, 837–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hatakeyama M., Tsudo M., Minamoto S., Kono T., Doi T., Miyata T., Miyasaka M., Taniguchi T. (1989) Interleukin-2 receptor β chain gene: generation of three receptor forms by cloned human α and β chain cDNA's. Science 244, 551–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baird S. M. (2006) Morphology of lymphocytes and plasma cells. In Williams Hematology (Lichtman M. A., Williams W. J., Beutler E., Kaushansky K., Kipps T. J., Seligsohn U., Prchal J., eds.), Part VIII, Lymphocytes and Plasma Cells, Ch. 74, New York, NY, USA, McGraw-Hill, 1023 [Google Scholar]

- 24. David D., Bani L., Moreau J. L., Demaison C., Sun K., Salvucci O., Nakarai T., de Montalembert M., Chouaib S., Joussemet M., Ritz J., Theze J. (1998) Further analysis of interleukin-2 receptor subunit expression on the different human peripheral blood mononuclear cell subsets. Blood 91, 165–172 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mailliard R. B., Alber S. M., Shen H., Watkins S. C., Kirkwood J. M., Herberman R. B., Kalinski P. (2005) IL-18-induced CD83+CCR7+ NK helper cells. J. Exp. Med. 202, 941–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kusano A., Ohta S., Shitara K., Hanai N. (1993) Immunocytochemical study on internalization of anti-carbohydrate monoclonal antibodies. Anticancer Res. 13, 2207–2212 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wargalla U. C., Reisfeld R. A. (1989) Rate of internalization of an immunotoxin correlates with cytotoxic activity against human tumor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 5146–5150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reisfeld R. A. (1990) Potential of genetically engineered monoclonal antibodies for cancer immunotherapy. Pigment Cell Res. Vol. 3 (Suppl. 2), 109–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sondel P. M., Gillies S. D. (2003) Immunocytokines for cancer immunotherapy. In Handbook of Cancer Vaccines (Morse M. A., Clay T. M., Lyerly H. K., eds.), Totowa, NJ, USA, Humana, 341–357 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hank J. A., Surfus J. E., Gan J., Jaeger P., Gillies S. D., Reisfeld R. A., Sondel P. M. (1996) Activation of human effector cells by a tumor reactive recombinant anti-ganglioside GD2 interleukin-2 fusion protein (ch14.18-IL2). Clin. Cancer Res. 2, 1951–1959 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Robertson M. J., Cochran K. J., Cameron C., Le J. M., Tantravahi R., Ritz J. (1996) Characterization of a cell line, NKL, derived from an aggressive human natural killer cell leukemia. Exp. Hematol. 24, 406–415 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Imboden M., Murphy K. R., Rakhmilevich A. L., Neal Z. C., Xiang R., Reisfeld R. A., Gillies S. D., Sondel P. M. (2001) The level of MHC class I expression on murine adenocarcinoma can change the antitumor effector mechanism of immunocytokine therapy. Cancer Res. 61, 1500–1507 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hank J. A., Robinson R. R., Surfus J., Mueller B. M., Reisfeld R. A., Cheung N. K., Sondel P. M. (1990) Augmentation of antibody dependent cell mediated cytotoxicity following in vivo therapy with recombinant interleukin 2. Cancer Res. 50, 5234–5239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith K. A., Cantrell D. A. (1985) Interleukin 2 regulates its own receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82, 864–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yu A., Olosz F., Choi C. Y., Malek T. R. (2000) Efficient internalization of IL-2 depends on the distal portion of the cytoplasmic tail of the IL-2R common γ-chain and a lymphoid cell environment. J. Immunol. 165, 2556–2562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Koch A. M., Reynolds F., Kircher M. F., Merkle H. P., Weissleder R., Josephson L. (2003) Uptake and metabolism of a dual fluorochrome Tat-nanoparticle in HeLa cells. Bioconjug. Chem. 14, 1115–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ovejera A. A., Houchens D. P., Barker A. D. (1978) Chemotherapy of human tumor xenografts in genetically athymic mice. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 8, 50–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kim Y., Kim H. S., Cui Z. Y., Lee H. S., Ahn J. S., Park C. K., Park K., Ahn M. J. (2009) Clinicopathological implications of EpCAM expression in adenocarcinoma of the lung. Anticancer Res. 29, 1817–1822 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Connor J. P., Felder M., Hank J., Harter J., Gan J., Gillies S. D., Sondel P. (2004) Ex vivo evaluation of anti-EpCAM immunocytokine huKS-IL2 in ovarian cancer. J. Immunother. 27, 211–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Went P. T., Lugli A., Meier S., Bundi M., Mirlacher M., Sauter G., Dirnhofer S. (2004) Frequent EpCam protein expression in human carcinomas. Hum. Pathol. 35, 122–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shusterman S., London W. B., Gillies S. D., Hank J. A., Voss S., Seeger R. C., Reynolds C. P., Kimball J., Albertini M. A., Wagner B., Gan J., Eickhoff J., DeSantes K. D., Cohn S. L., Hecht T., Gadbaw B., Reisfeld R. A., Maris J. M., Sondel P. M. (2010) Antitumor activity of hu14.18-IL2 in relapsed/refractory neuroblastoma patients: a Children's Oncology Group (COG) phase II study. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 4969–4975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hank J. A., Surfus J. E., Gan J., Ostendorf A., Gillies S. D., Sondel P. M. (2003) Determination of peak serum levels and immune response to the humanized anti-ganglioside antibody-interleukin-2 immunocytokine. Methods Mol. Med. 85, 123–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kendra K., Gan J., Ricci M., Surfus J., Shaker A., Super M., Frost J. D., Rakhmilevich A., Hank J. A., Gillies S. D., Sondel P. M. (1999) Pharmacokinetics and stability of the ch14.18-interleukin-2 fusion protein in mice. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 48, 219–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]