Abstract

Background

Improving strategies for risk reduction among family members of patients with melanoma may reduce their risk for melanoma.

Objective

To evaluate the effects of two behavioral interventions designed to improve the frequency of total cutaneous skin examination by a health provider (TCE), skin self-examination (SSE), and sun protection practices among first degree relatives of patients with melanoma and to evaluate whether increased behavioral intentions, increased benefits, decreased barriers, and improved sunscreen self-efficacy mediated the effects of the tailored intervention as compared with the generic intervention on TCE, SSE, or sun protection.

Methods

Four hundred forty-three family members (56 parents, 248 siblings, 239 children) who were non-adherent with these practices were randomly assigned to either a generic (N= 218) or a tailored intervention (N = 225) which included 3 print mailings sent monthly and one telephone counseling session. Participants completed measures of TCE, SSE, and sun protections at baseline, six months, and one year. Participants completed measures of intentions, benefits, barriers, and self-efficacy. The retention rate at the one year follow-up was 86.7%.

Results

Those enrolled in the tailored intervention had almost a twofold increased probability of having a TCE (p < .0001). Treatment effects in favor of the tailored intervention were also noted for sun protection habits (p < .02). Increases in TCE intentions mediated the tailored intervention’s effects on TCE uptake. Increases in sun protection intentions mediated effects of the tailored intervention’s effect on sun protection habits.

Conclusions

Tailored interventions may improve risk reduction practices among family members of patients with melanoma and support a role of such interventions in melanoma prevention.

Keywords: skin examination, sun protection, intervention, melanoma patients, family members

The incidence of cutaneous melanoma (CM), the most deadly type of skin cancer, is increasing faster than any other cancer (Howe et al., 2001; Reis, Eisner & Kosary, 2005). There are primary and secondary methods for CM. Primary CM prevention involves limiting exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation (Fears et al., 2002; Koh et al., 1991) and secondary prevention methods include skin cancer surveillance and early detection. Because melanoma thickness is the best predictor of prognosis (Breslow, 1970), routine total cutaneous examination by a health care provider (TCE) and skin self-examination (SSE) are thought to increase the probability of detecting thinner melanomas thereby reducing morbidity and mortality. Various professional agencies (American Academy of Dermatology, 2009; American Cancer Society, 2009; CDC, 2009) recommend sun avoidance during peak UV hours and use of sun protective clothing. Monthly SSE for individuals more than 20 years of age is recommended by the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and the Skin Cancer Foundation (American Academy of Dermatology, 2009; Skin Cancer Foundation, 2009).

Because epidemiologic data supporting regular skin cancer surveillance remains equivocal, it may be premature to target average risk populations for interventions to improve skin cancer surveillance. First-degree relatives (FDRs) of individuals with CM have a two to eightfold increased risk of developing the disease (Balch, 1992; Ford et al., 1995; Rhodes, Weinstock, Fitzpatrick, Mihm, & Sober, 1987) and, thus, may gain particular benefit from information about melanoma risk reduction strategies.

Despite their increased CM risk, family members pay relatively little attention to UV protection and skin surveillance (Azzarello, Jacobsen, Dessureault, & Puleo, 2004; Geller & Halpern, 2006; Manne et al., 2004). There have been few interventions to promote skin cancer risk reduction practices among family members but one study suggests that such interventions may be effective (Geller et al., 2006).

In the present study, we compared a tailored, multi-component intervention targeting TCE, SSE, and sun protection with the best available public health materials. Although the generic intervention was not completely equated with the tailored intervention in terms of intervention length and the level of detail in the intervention content, the generic arm did allow for a comparison of time and attention. The present study also provides a comparison with widely-available materials on skin cancer risk reduction. This is an advance from previous work which has compared a behavioral intervention with a no-treatment control condition (Geller et al., 2006). The tailored intervention tested in the present study utilized behavioral construct tailoring (Kreuter et al., 2000) and was based on empirical research on key correlates of each behavior (Manne et al., 2004) and theoretically guided by the Preventive Health Model (PHM) (Myers et al., 1994) and the normative influences construct from the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). Constructs from the PHM that guided the tailoring and/or mediation were the representation factors of perceived risk, salience and coherence, self-efficacy, the behavioral intention factor, and the social influence factor. The TPB construct that guided tailoring was normative influence which was used to tailor sun protection material since it was associated with sun protection in our previous work (Manne et al., 2004).

The study had two aims. First, we evaluated the impact of generic print and telephone counseling (generic intervention) versus tailored print and telephone counseling interventions (tailored intervention) on engagement in TCE, SSE, and sun protection habits. We hypothesized that the tailored intervention would result in significantly greater engagement in TCE, SSE, and sun protection habits. Second, we examined whether behavioral intentions, perceived benefits, and perceived barriers mediated the associations between the interventions and TCE, SSE, and sun protection habits. In addition, for sun protection habits, we evaluated whether sunscreen self-efficacy mediated treatment effects. Our selection of mediators was based primarily on factors targeted for tailoring (benefits and barriers, sunscreen efficacy) as well as theory (the TPB proposes that behavioral intentions must increase in order for behavior change to occur) (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980).

Methods

Participants

Participants were FDRs of patients recruited from the cutaneous oncology practices at three medical centers (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Moffitt Cancer Center, and the University of Pennsylvania Health Systems). Participants were identified from tumor registries or medical records. IRB approval was received at each site. Physicians gave permission for their patients to be contacted. Recruitment began in February 2006 and ended in September 2008. Follow-ups were completed in July 2009. Eligibility criteria were: a) newly diagnosed with CM within the past five years but more than 3 months prior to being approached; b) seen at one of the three participating sites; c) greater than 18 years of age; d) English speaking; e) able to give meaningful informed consent; f) does not have a FDR with CM. Eligible patients were mailed a letter and contacted to determine eligibility. Patients gave permission to contact FDRs and permission for information to be obtained from their medical chart.

Next, identified FDRs were mailed a letter describing the study. They were contacted by telephone and eligibility was determined. Eligibility criteria were: a) current age of at least 20 years; b) has not had a TCE in the past 3 years, has done SSE three or fewer times in the past year, and has a sun protection habits mean score less than 4 (on a 5-point Likert scale). c) one or more of the following additional risk factors: blonde or red hair, marked freckling on the upper back, history of three or more blistering sunburns prior to age 20, 3 or more years of an outdoor summer job as a teenager, and actinic keratosis; d) English speaking; e) residential phone service; f) no personal history of CM or non-melanoma skin cancer; g) no personal history of dysplastic nevi, and; h) no more than one FDR with CM.

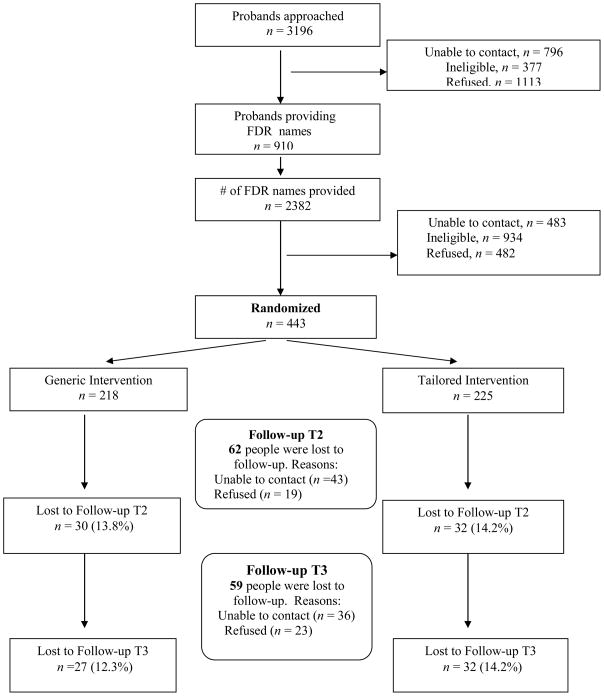

The CONSORT schema is shown in Figure 1. Of the 3196 probands approached, 11.8% were ineligible, 24.9% could not be located, 34.8% refused, and 28.5% of probands provided permission to contact their relatives. These 910 probands provided 2382 names (2.6 per proband). Of these 2382, 39.2% were ineligible and 20.2% could not be located. Of the 996 eligible and locatable FDRs identified, 443 (44.5%) enrolled. Of these 443, 381 completed Time 2 (86%) and 384 (86.7%) completed Time 3. Completion rates are outlined in Figure 1. Note that all data were used for analyses. There were no differences in completion rates between the two arms.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram

A comparison between the 482 FDRs who refused with the 443 FDR participants on available demographic information indicated that participants were significantly younger than refusers (t (743) = 3.4, p < .001; Mparticipants = 47.6, SD = 9.0, Mrefusers = 51.4, SD = 9.1) and that participants were more likely to be female (Percentage femaleparticipants = 63%; Percentage femalerefusers = 46%; Chi-square (2) = 27.2, p < .001). In addition, there was a significantly higher acceptance rate among FDRs recruited from Moffitt Cancer Center than the other two sites (Acceptance rateMofffit= 66%; Acceptance rateFox Chase = 47.2%; Acceptance rateU Penn = 42.6%; Chi-square (2) = 26.2, p < .001).

Participants were randomized to study condition by family. All participants received intervention materials on a monthly timeline. Three months after the final mailing of the intervention materials (six months after the baseline survey), participants completed the Time 2 survey. Nine months after the final intervention mailing (one year after the baseline survey), participants completed the Time 3 survey. Participants were given $10 gift certificates for each assessment completed.

Interventions

Generic intervention

There were three print mailings and one telephone counseling call delivered two weeks after the last mailing. The first mailing focused on melanoma, melanoma risk, and TCE. Participants were mailed the American Cancer Society pamphlet “Why You Should Know About Melanoma” (American Cancer Society, 2005) and the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) bookmark, “The Complete Skin Exam” (2003). The second mailing focused on SSE. A bookmark published by the AAD, “Look for the danger signs in pigmented lesions of the skin” (1992) and a pamphlet published by the Skin Cancer Foundation, “Skin Cancer: If you can spot it- you can stop it!” (1992) were included. The third mailing focused on sun protection. Participants were mailed two pamphlets published by the Skin Cancer Foundation, “Get Smart! Go Under Cover” (2005) and “Simple Steps to Sun Safety” (Skin Cancer Foundation, 2005). Letters accompanying the mailings recommended each behavioral change. The generic telephone counseling call occurred after the third mailing. During the call, the health educator reviewed the guidelines for SSE, TCE, and sun protection, the steps to performing SSE, how to protect one’s skin, and ways to reduce sun exposure. The necessity of having a TCE was reinforced. No information regarding the participant’s survey answers was provided. Calls were rated for fidelity and counselors were given regular fidelity feedback.

Tailored intervention

The first tailored print labeled “Have a Dermatologist Examine your Skin” had four pages. The first page had a “Skin Cancer Risk Profile” that was tailored to participant answers to behavioral and objective (e.g., blonde or red hair) risk factors. The second page focused on Tip 1: “Know More About Melanoma.” The content was tailored to the facts about CM that the participant did not answer correctly. The third page focused on Tip 2: “Consider the Benefits of a Total Skin Exam.” There were five barrier/benefit messages. An age and gender matched picture with a quote tailored to the highest ranked barrier was included. The fourth page focused on Tips #3 and 4. Tip #3, “Follow the Expert’s Recommendation,” contained a tailored recommendation for TCE from the dermatologist at the proband’s hospital. Tip #4, “Schedule a Total Skin Exam,” discussed the doctor’s level of support for TCE, suggested the participant discuss the family history (tailored to whether it was a sibling, parent, child) with the doctor, and what to expect from the physician during a TCE. The second tailored print titled, “Examine Your Skin Regularly” had four pages. The first page labeled, “Why is it important for you, {name}, to do regular skin exams?” stated how often the participant had engaged in SSE in the past year and had a list of reasons that people do not do SSE and reasons relevant to the participant were checked off. The second page contained Tips #1 and 2. Tip #1 was entitled “Address your reasons for not checking your skin.” There were four benefit/barrier tailored messages. Tip #2 was entitled “Know what to look for while doing your self-exam.” The first paragraph was tailored to whether or not the participant reported that s/he did not know what cancer looked like, and the ABCD’s of what melanoma looks like were shown. Tip #3, “Know how to examine your skin” had a statement tailored to whether or not the physician had shown the participant how to do SSE followed by an illustration of the steps. Tip #4, “See a dermatologist if you find something suspicious” contained a statement that the best way to find melanoma is to check your skin and have a dermatologist check your skin as well as a tailored statement about whether a doctor had recommended SSE. Tip #5 entitled, “Start a skin self-exam routine” had a body map and contained suggestions on how to use it to indicate moles.

The third print mailing was entitled “Protect Yourself from the Sun”. The first page had a chart with a sun protection score card that was personalized with a score breakdown. Page 1 contained Tip #1, “Know how your sun protection habits measure up.” The section outlined sun protection habits and possible alternative sun protection practices and included a quote from the cutaneous oncologist at each site recommending sun protection. Page 2 had Tips #2 and 3 on it. Tip #2, “Consider what dermatologists say about sun protection” outlined answers to common myths about sun protection. Tip #3, “Recognize the importance of using sunscreen” contained four messages. This section contained the four top-rated barriers to sun protection. Page 4 had Tip #4, “Be aware of the dangers of tanning” and Tip #5, “Set a good example for others.” Tip #4 contained four tailored messages based on image norms pointing out sunless tanning options and the sun damage to the skin induced by exposure, indoor tanning practices, and sunbathing intentions. A picture of UV damaged skin was included. Tip #5 outlined the importance of family and friends’ influence on tanning and contained a tailored message based on answers to the tanning norms.

During the tailored counseling call, the educator reviewed the participant’s current TCE and SSE practices, reviewed guidelines for TCE and SSE, discussed benefits of TCE and SSE, reviewed the participant’s risk factors for CM, discussed alternative ways of thinking about TCE barriers, and discussed feelings about asking the health care provider about TCE. Next, the counselor discussed the participant’s reasons for not conducting SSE regularly and queried about ways the participant might try to motivate him/herself, reviewed steps to performing SSE, benefits of discussing SSE with the physician, and possible benefits of discussing SSE with the affected FDR were discussed. Finally, current sun protection habits, barriers to better sun protection habits and ways to motivate oneself to engage in greater protection were discussed along with family and friends’ sun protection and tanning attitudes and practices and the need to serve as a role model for others with regard to sun protection. Calls were rated for fidelity and counselors were regularly given feedback in terms of content and duration of the calls.

Outcome Measures-All time points

TCE

Participants were asked whether they had seen a dermatologist, or any doctor, and had a complete examination of their skin (skin checked from head to toe) (yes/no) in the past three years (baseline) or since the last assessment (follow-ups).

SSE frequency

Participants were asked how often they examined their skin “deliberately and purposefully” in the past year (baseline) or since the last assessment (Time 2, 3) (Manne et al., 2004).

Sun protection habits

A five-item scale (Glanz, Schoenfeld, Shigaki, & Evensen, 2002) measured protection habits (using sunscreen, wearing a hat, seeking shade, wearing shirt with sleeves, wearing sunglasses) on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “never”, 5 = “always”). Items were summed and an average computed.

Covariates (Time 1 only)

Demographics

Participant age, gender, income, and education were collected.

Medical access

Items assess whether the participant saw a physician for regular medical care (yes/no) and the participant’s insurance status (yes/no).

Mediator Variables (Time 1 and 2 only)

Intentions

Four items assessed TCE intentions (e.g., “How likely is it that you will try to make an appointment to have a TCE by a doctor or other health care professional in the next year?” and three items assessed SSE intentions (e.g. “How likely are you to do skin self-examination in the next year?”). Items were based upon our previous work on colorectal cancer screening intentions among family members of patients with colorectal cancer (Manne et al., 2009). Seven items assessed sun protection intentions (“Do you plan to protect yourself from sun exposure on a regular basis when you are out in the sun for more than 30 minutes in the next year?”) and four items assessed sunbathing intentions (e.g., “I intend to sunbathe in the next year”). Items were taken from Mahler et al. (1997) and Jackson and Aiken (2000). Cronbach’s alphas across measures and time points ranged between .70 and .92.

Benefits

The TCE benefits scale (Manne et al., 2004) consisted of nine items (e.g., “Having a total skin examination is a part of good health care”). Alphas were .90 and .93 at Time 1 and 2, respectively. The SSE benefits scale (Manne et al., 2004) consisted of eight items (e.g., “Skin self-examination is very important for people with my history of cancer in the family”). Alphas were .87 at baseline and .88 at Time 2. The SSE barriers scale (Manne et al., 2004) consisted of 10 items (e.g., “Doing skin self-examination would be very embarrassing”). This measure has been associated with SSE performance in previous research (Manne et al., 2004). Alphas were .87 and .88 at Time 1 and 2, respectively. Glanz and colleagues’ (1999) sun protection benefits scale consisted of six items assessing how much the participant believed each habit would protect them against the sun (e.g., “Wear a hat”). Alphas were .69 and .65 at baseline and Time 2, respectively. This scale has been associated with sun protection in previous research (Manne & Lessin, 2006).

Barriers

The TCE barriers scale taken from Manne and colleagues (2004) consisted of nine barriers (e.g., “It would be embarrassing to have a doctor or other health care professional look at my entire body”). This measure has been associated with TCE performance in previous research (Manne et al., 2004). Alphas at both time points were .68. The SSE barriers scale (Manne et al., 2004) consists of ten barriers (e.g., “I would not go in to see a doctor for a total skin examination unless I noticed an abnormal growth on my skin”). This measure has been associated with SSE performance in previous research (Manne et al., 2004; Manne & Lessin, 2006). Alphas at baseline and Time 2 were .87 and .88. The sunscreen barriers scale (Manne et al., 2004) consisted of six barriers (e.g., “The cost of sunscreen may possibly keep me from using it”). Alphas at baseline and Time 2 were .85 and .84.

Sunscreen self-efficacy

An eight-item scale developed by Jackson and Aiken (2000) assessed efficacy (alphas at baseline and Time 2 = .88 and .90). Items assessed confidence in using sunscreen in various situations (e.g., “How confident are you that you can use sunscreen while doing outdoor activities in the winter”). This measure has been associated with sun protection intentions (Jackson & Aiken, 2000; Jackson & Aiken, 2006) and behavior (Manne & Lessin, 2006) in previous research.

Intervention evaluation, TCE confirmation, and fidelity measures

Materials Evaluation

At Time 3, participants were asked whether they received the print material and the degree to which the information was interesting and credible (Lipkus, Rimer, Halabi, & Strigo, 2000) (Brug, Steenhuis, Van Assema, & de Vries, 1996).

Confirmation of TCE

All reported TCEs were confirmed with the subject’s physician at both follow-ups.

Treatment fidelity

The GC fidelity form contained the 19 topics covered in the counseling call (e.g., guidelines, warning signs of melanoma, SSE steps, ways to protect yourself from the sun, importance of using sunscreen, and how to apply sunscreen). The TC fidelity form was comprised of the 64 topics covered in the counseling call (e,g., current TCE and SSE performance, guidelines, reasons for doing TCE and SSE, personal risk factors, personal barriers and rebuttals, how to perform SSE, sun protection practices, barriers to sun protection, and normative influences). Coverage of topics was coded yes/no and a percentage was calculated. Six raters were trained by a criterion coder and reached inter-rater reliability of 90% before completing fidelity ratings. All sessions were rated.

Statistical Analysis

Due to the repeated measures design and the fact that many respondents were members of the same family, the repeated measures were nested within the individual and the individual was nested within his/her family. As a consequence of the nesting, the data were not statistically independent and the procedures used were designed to accommodate these properties. When a continuously scaled variable was used as an outcome, the analysis involved a hierarchic linear mixed model for repeated measures implemented in the SAS procedure MIXED. When the outcome was dichotomous, a Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) approach with a logit link function was used. The SAS procedure GENMOD was employed.

Prior to undertaking the repeated measures analyses, the correlations of potential covariates with the various outcomes were examined. Covariates included participant gender, age, ethnic category, marital status, medical insurance, education, income, proband stage at diagnosis, and time since diagnosis. Variables whose correlation with each outcome yielded a p-value of less than 0.15 were selected as potential covariates. The analyses were conducted in a step-wise fashion. First, using an unconditional means model, the appropriate error variance-covariance structure was identified using Akaike’s Information Criterion (1973). Next, time of assessment was entered both as a linear and quadratic variable. Variables identified as potential covariates were then entered as a group in the repeated measures analysis. Only statistically significant covariates were retained. Treatment effects were assessed using an Intent to Treat (ITT) analysis. Once the treatment effect had been entered into the model, the assumption of non-significant treatment by covariate interactions was then assessed. Finally, potential mediator effects were considered following procedures discussed by MacKinnon (2008) and Shrout and Bolger (2002). Possible mediating variables were measured only at baseline and Time 2. Using these two measurements in a repeated measures analysis, treatment condition was evaluated as a predictor of each mediator. Those showing significant treatment effects were retained for further analysis.

The analyses were conducted in several steps. First, for each of the outcomes showing a significant treatment effect, the initial focus involved Time 2 outcomes. Second, treatment effects of Time 2 mediators on Time 3 outcomes were assessed. Third, if the treatment predicted the Time 2 outcome, the outcome at that earlier time period was also added to the model as a control. In both analyses, mediation was assumed if: a) the parameter for treatment declined in magnitude; b) the mediator was a significant predictor of the outcome; and c) the indirect path from treatment to mediator and from mediator to outcome was significant using bootstrap sampling.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Three hundred twenty four patients (324 families) provided family members.

Table 1.

Descriptive Information on the Study Sample

| Variable | Full Sample n= 443 | Generic Intervention n= 218 | Tailored Intervention n= 225 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | M | D | N | % | M | D | N | % | M | D | |

| Age (yrs) | 47.6 | 13.2 | 47.1 | 13.9 | 48.1 | 12.6 | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Men | 164 | 37 | 74 | 33.9 | 90 | 40.0 | ||||||

| Women | 279 | 63 | 144 | 66.1 | 135 | 60.0 | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Single | 131 | 29.6 | 66 | 30.3 | 65 | 28.9 | ||||||

| Married | 312 | 70.4 | 152 | 69.7 | 160 | 71.1 | ||||||

| Educational level | ||||||||||||

| Some high school | 3 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 6.9 | ||||||

| High school | 63 | 14.2 | 32 | 14.7 | 31 | 13.8 | ||||||

| Some college | 102 | 230 | 54 | 24.8 | 48 | 21.3 | ||||||

| ≥ College degree | 275 | 62.1 | 131 | 60.1 | 144 | 63.9 | ||||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Caucasian | 435 | 98.2 | 217 | 99.5 | 218 | 96.9 | ||||||

| Non-Caucasian | 8 | 1.8 | 1 | 0.5 | 7 | 3.1 | ||||||

| Income | ||||||||||||

| < $20,000 | 15 | 3.4 | 11 | 5.1 | 4 | 1.7 | ||||||

| $20,000–$59,999 | 115 | 25.9 | 55 | 25.3 | 60 | 24.6 | ||||||

| $60,000–$99,999 | 97 | 21.9 | 53 | 24.3 | 44 | 19.6 | ||||||

| $100,000–$139,999 | 93 | 21.0 | 39 | 17.9 | 54 | 24.0 | ||||||

| ≥ $140,000 | 72 | 16.2 | 36 | 16.5 | 36 | 16.0 | ||||||

| Relationship to Proband | ||||||||||||

| Parent | 56 | 12.6 | 34 | 15.6 | 22 | 9.8 | ||||||

| Sibling | 148 | 33.4 | 76 | 34.9 | 72 | 32.0 | ||||||

| Child | 239 | 53.9 | 108 | 49.5 | 131 | 58.3 | ||||||

| Health Insurance (yes) | 418 | 94.4 | 207 | 95.0 | 211 | 93.8 | ||||||

| Proband disease stage | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 75 | 16.4 | 34 | 15.5 | 41 | 18.2 | ||||||

| 1 | 187 | 41.7 | 95 | 44.7 | 92 | 40.8 | ||||||

| 2 | 94 | 22.5 | 45 | 21.7 | 49 | 21.8 | ||||||

| 3 | 60 | 13.0 | 30 | 12.4 | 30 | 13.3 | ||||||

| 4 | 27 | 6.5 | 14 | 5.6 | 13 | 5.8 | ||||||

| Proband recurrence (yes) | 35 | 10.8 | 18 | 11.1 | 17 | 10.4 | ||||||

| Proband age at diagnosis | 54.5 | 15.2 | 52.1 | 14.9 | 56.9 | 15.1 | ||||||

Process Evaluation

The majority of participants remembered receiving print materials in the mail (99%), reported reading most of the material (78.3%), and saving the materials (89%). Approximately half of the sample showed the material to family and friends (62%) but only a subset (23%) reported discussing them with their physician. Comparisons between study arms indicated that there were no significant differences with regard to whether the participants remembered receiving the print materials, whether they read the materials, and whether they saved the materials. However, tailored print materials were read for a significantly longer period of time as well as rated significantly (p < .05) higher than the generic print on the following attributes: valuable, prepared with the participant in mind, making it easier to think about having a TCE, and addressing reasons for not performing SSE, TCE, and sun protection.

Among the 347 participants receiving the telephone counseling session, the mean call length was 21 minutes. Call length was significantly greater for the tailored intervention (M = 30.2 minutes, SD = 8.6) than the generic intervention (M= 11.5 minutes, SD = 2.6) (t (381) = 29, p < .001). Seventy-three percent of participants who received the call reported that they remembered receiving it. Comparisons between study arms indicated that tailored telephone calls were rated significantly higher (p < .05) on the following attributes: helpful, novel, easy to understand, contained valuable information, prepared with the participant in mind, making it easier to think about having a TCE, SSE, or improve sun protection, addressing reasons for not having TCE, SSE, and practicing better sun protection.

Treatment fidelity

Of the 347 telephone sessions conducted, 311 were taped and rated. The remaining 36 sessions were not taped due to mechanical problems. The average rating for the generic sessions was 99.2% (range= 88.5–100%) and the average rating for the tailored sessions was 89.7% (range=46–100%).

Confirmation of TCE

Of the 101 TCE procedures reported at Time 2, 73 were confirmed (72.2%). In 6 cases, the physician reported that no procedure had been performed (6%), in 7 cases the physician’s office did not return the form (8%), and, in 15 cases, the participant did not provide sufficient information to locate the practice (15%). Of the 63 procedures reported at Time 3, 44 were confirmed (71.4%). In 10 cases, the physician reported that no procedure had been performed (15.8%), in 5 cases the physician’s office did not return the form (8%), and in 4 cases the participant did not provide sufficient information to locate the practice (6.3%). There were no significant differences in confirmation rates across study condition at either follow-up.

Intervention effects on TCE

Table 2 summarizes the TCE outcomes. Over time, there was a significant (z = 11.57; p < 0.0001) increase in the log odds of having a TCE. None of the covariates were significant predictors. The treatment main effect was highly significant (z = 3.87; p = 0.0001). Those in the tailored arm were 1.94 times more likely to have had a TCE (O.R. = 1.94; 95% C.I. 1.39, 2.72) than those in the generic group.

Table 2.

Intervention effects on TCE, SSE, and Sun Protection Habits

| Variable | Generic Intervention | Tailored Intervention | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up 1 | Follow-up 2 | Baseline | Follow-up 1 | Follow-up 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| N | % | M | SD | N | % | M | SD | N | % | M | SD | N | % | M | SD | N | % | M | SD | N | % | M | SD | |

| TCE (yes) | 0 | (0) | 39 | (20.7) | 21 | (11) | 0 | (0) | 63 | (32.6) | 43 | (22.2) | ||||||||||||

| SSE frequency | 0.34 | (.80) | 3.8 | (17.5) | 6.2 | (24.4) | 0.42 | (.86) | 5.6 | (24.8) | 8.8 | (34.9) | ||||||||||||

| Sun protection | 2.8 | (.65) | 3.2 | (.69) | 3.2 | (.73) | 2.8 | (.66) | 3.4 | (.76) | 3.4 | (.79) | ||||||||||||

Note: TCE= Total Cutaneous Exam; SSE = Skin Self-Exam

Mediator effects

Means and standard deviations for mediators are shown in Table 3. The average correlation among these mediators was 0.50. TCE benefits and barriers did not mediate treatment effects. The repeated measures analysis of TCE intentions yielded a significant (t (379) = 66.65; p < 0.0001) positive, linear increase over time. After adjustment for the covariates, there was a significant (t (439) = 2.81; p = 0.0051) treatment effect in favor of the tailored condition. Whether the respondent reported having a TCE at Time 2 was evaluated next. None of the covariates predicted TCE. However, treatment condition was significant (z = 2.62; p = 0.0087) in favor of the tailored group. The addition of TCE intention at Time 2 indicated that stronger intentions were associated with a significant (z = 4.82; p < 0.0001) increase in the log odds of TCE. The significant treatment group main effect became marginally significant (z = 1.87; p = 0.0612) suggesting that TCE intention mediated the treatment effect. The proportion of the treatment effect that was mediated was 0.27. The 95% confidence interval using 1000 bootstrap samples did not include zero indicating that the indirect effect was significant.

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations of Study Mediators

| Generic Intervention | Tailored Intervention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Time 2 | Baseline | Time 2 | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| TCE Model | ||||||||

| Intentionsa | 4.95 | (1.77) | 5.57 | (1.54) | 4.83 | (1.85) | 6.02 | (1.40) |

| Benefitsb | 5.20 | (.78) | 5.29 | (.80) | 5.18 | (.73) | 5.43 | (.61) |

| Barriersb | 2.21 | (.85) | 2.08 | (.77) | 2.14 | (.84) | 2.02 | (.82) |

| SSE Model | ||||||||

| Intentionsa | 5.00 | (1.38) | 4.58 | (1.44) | 5.04 | (1.42) | 4.81 | (1.32) |

| Benefitsb | 5.04 | (.79) | 5.13 | (.77) | 4.96 | (.74) | 5.25 | (.67) |

| Barriersb | 2.53 | (.68) | 2.66 | (.72) | 2.44 | (.71) | 2.73 | (.75) |

| Sun Protection Habits Model | ||||||||

| Sun protection intentionsc | 3.69 | (.46) | 4.35 | (.51) | 3.69 | (.48) | 4.48 | (.46) |

| Sun protection benefitsc | 4.61 | (.81) | 4.86 | (.73) | 4.61 | (.76) | 4.88 | (.81) |

| Sunscreen self-efficacye | 2.75 | (.94) | 3.04 | (.98) | 2.74 | (.96) | 3.33 | (.97) |

Note: TCE= Total Cutaneous Exam; SSE = Skin Self-Exam;

1 = not at all likely, 7 = extremely likely;

1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree;

1=not at all, 7=definitely;

1 = not at all helpful, 5 = extremely helpful,

1 = not at all confident, 5 = extremely confident.

Next, having a TCE at Time 3 was modeled as a function of treatment group controlling for whether the participant had a TCE at Time 2. Only treatment group was significant (z = 2.84; p = 0.0046) in favor of the tailored group. The inclusion of TCE intention showed it was a significant predictor of Time 3 TCE (z = 4.29; p < 0.0001). Although treatment group continued to be significant (z = 2.25; p = 0.0243), the decrease in the treatment parameter estimate suggested that Time 2 TCE intention was a mediator. The proportion of the treatment effect that was mediated was 0.19. The 95% confidence interval using 1000 bootstrap samples did not contain zero indicating that the indirect effect was significant.

SSE Performance

Analysis of SSE frequency yielded a significant (t (442) = 12.85; p < 0.0001) positive, linear trend. However, the quadratic effect for time was also significant (t (442) = −6.21; p < 0.0001). At baseline, average SSE frequency over the last year was less than once (0.14). At Time 2, the average number of times increased to 0.60 and, at Time 3, the average had increased to at least once last year (1.02). Thus, while there was an increase in the number of SSEs, the increase declined over time. Covariate analysis indicated that increases in SSE frequency were associated with the proband’s being diagnosed at a younger age (t (435) = −1.81; p = 0.0706). After controlling for the covariate, the main effect for treatment group was not significant (t (437) = 1.65; p = 0.0991).

Mediator effects

Since the treatment effect for SSE performance at Times 2 and 3 was not significant, mediation tests were not pursued.

Sun Protection Habits

Analysis of sun protection habits yielded a significant (t (442) = 12.92; p < 0.0001) linear increase over time. The quadratic effect for time was also significant (t (442) = −9.13; p < 0.0001). At baseline, the average sun protection habit score was 2.78. At Time 2, the score had increased to 3.30 and it remained at 3.30 at Time 3. None of the covariates were significant predictors. The time by treatment interaction was significant (t (441) = 1.91; p = 0.0475). The difference at Time 2 was not significant (t (441) = −1.72; p = 0.0850). At Time 3, there was a significant (t (441) = −2.27; p = 0.0237) difference between the tailored (M = 3.39) and generic conditions (M = 3.22).

Mediator effects

As noted previously, mediators were measured only at baseline and Time 2. In the first step of the mediation analyses, treatment effects were assessed for each mediator at Time 2. Analysis of Time 2 sun protection intentions indicated a significant positive, linear increase in intentions over time. After controlling for the covariates, the main effect for treatment condition was not significant and the time by treatment interaction was not significant.

There was a significant increase in sun protection benefits over time. After controlling for the covariates, the main effect for treatment condition was not significant. However, the time by treatment group interaction was clearly significant (t (331) = 2.32; p = 0.0211). There was a significant difference (t (388) = −2.63; p = 0.0090) at Time 2 in favor of the tailored group (Mtailored 31.35 vs Mgeneric = 30.40). For sunscreen self-efficacy, there was a significant increase over time. The time by treatment interaction was significant (t (379) = 2.60; p = 0.0098). At Time 2, there was a significant (t (436) = −2.88; p = 0.0049) difference in favor of the tailored group (M = 3.54 vs. Generic M = 3.27).

The first mediation model focused specifically on Time 2 sun protection habits. This model showed no treatment group differences (p = 0.1271) thus providing no support for mediation. When Time 3 sun protection habits were evaluated, none of the covariates was significant. However, there were significant treatment differences (t (290) = 2.58; p = 0.0102). Tailored group participants reported more sun protection habits (M = 3.41) than generic group participants (M = 3.19). This model was considered the base model. Each of the potential mediators (sun protection intentions, sun protection benefits, and sunscreen self-efficacy; the average correlation among these variables was 0.33) was added to the base model individually and, then, as a group. Table 4 summarizes the individual analysis results. The inclusion of each mediator in the sun protection habits model at Time 2 resulted in the loss of significance for treatment group indicating mediation. The 95% confidence interval using 1000 bootstrap samples did not contain zero indicating that the indirect effect of each was significant and each served as a mediator of treatment effects on sun protection habits at Time 3.

Table 4.

Results of Mediational Analyses for Sun Protection Habits

| Model and variable | Parameter estimate | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Effect of treatment on sun protection | 0.2099 | 0.0817 | 2.58 | 0.0107 |

| 2A. Effect of treatment on mediator measured at Time 2 | ||||

| Sun protection intentions | 0.3435 | 0.1249 | 2.75 | 0.0064 |

| Sun protection benefits | 0.9186 | 0.3286 | 2.80 | 0.0055 |

| Sunscreen self-efficacy | 0.2993 | 0.0973 | 3.08 | 0.0023 |

| 3A. Effect of mediator at Time 2 on sun protection habits measured at Time 3 | ||||

| Sun protection intentions | 0.4236 | 0.0309 | 13.71 | 0.0001 |

| Sun protection benefits | 0.0706 | 0.0108 | 6.51 | 0.0001 |

| Sunscreen self-efficacy | 0.2674 | 0.0434 | 6.16 | 0.0001 |

| 3B. Effect of treatment on Time 3 sun protection habits controlling for Time 2 mediators | ||||

| Sun protection intentions | 0.0286 | 0.0666 | 0.43 | 0.6672 |

| Sun protection benefits | 0.1188 | 0.0794 | 1.50 | 0.1358 |

| Sunscreen self-efficacy | 0.0889 | 0.0763 | 1.17 | 0.2446 |

In the final model, the three potential mediators were included as a group predicting sun protection habits along with treatment condition. Sun protection intentions continued to be significant (t (80) = 11.77; p < 0.0001) but sunscreen self-efficacy (t (80) = 1.85; p = 0.0682) and sunscreen benefits were no longer significant (p = 0.9457). In addition, the main effect for treatment was non-significant (p = 0.8155). The proportion of treatment effect that was mediated by these intentions and efficacy was 0.93.

Discussion

Although both interventions resulted in increases in TCE, SSE, and sun protection habits, the tailored intervention evidenced stronger effects. Our results for the tailored intervention’s impact on TCE were notable in that there was almost a twofold increased probability of having a TCE. Effects were of a lesser magnitude for SSE and sun protection habits. The tailored intervention did not result in a significantly greater increase in SSE frequency among participants assigned to this group although it is encouraging that the increases noted at the first follow-up were maintained at the one year follow-up. Our findings for sun protection habits indicated non-significant effects at Time 2 but a significant effect in favor of the tailored intervention at Time 3. These findings demonstrate that tailored interventions may be more efficacious than generic interventions.

The fact that our tailored intervention resulted in a greater increase in the likelihood of TCE as compared with the generic intervention has not been reported in previous research targeting CM patients’ family members (Geller & Halpern, 2006). Geller and colleagues (2006) reported that both their active intervention and usual care interventions doubled TCE screening rates with no between group differences. In that study, families in the usual care arm received a standard physician practice of suggesting that patients with melanoma should notify their family members about their diagnosis and patients were encouraged to make appointments for relatives to be screened at the same site as where the patient was seen. Participants in the active intervention received a goal setting and motivational telephone session, computer-generated tailored print materials sent at three time points, three tailored telephone calls, and linkages to free screening programs. There were no group differences with regard to TCE. These findings differ from those in the present study. However, providing an explanation for differences across studies is complicated by the fact that they differed with regard to the target population, the pre-intervention level of compliance with surveillance and protection habits, and the intensity of the treatment arms.

We found that the tailored and generic interventions were equally effective in increasing SSE. Our tailored intervention’s effects on SSE frequency contrast with previous research which noted a stronger impact for the tailored intervention as compared to usual care (Geller & Halpern, 2006). As noted above it is difficult to compare these two studies due to the different methodologies adopted. Nevertheless, it is possible that the fact that the comparison condition in the present, generic materials, was more intensive than the usual care intervention used by Geller and colleagues (2006) (asking the proband to recommend TCE) explained the fact that their study reported a stronger effect for the tailored intervention. That is, our generic intervention provided education about SSE whereas the usual care intervention in the Geller study did not target SSE.

Our results suggest that information tailored to FDRs knowledge and attitudes may not be more effective than the widely-available educational information on SSE which is accompanied by a brief educational session reviewing this material. Our results for sun protection habits are encouraging because the previous intervention study for at-risk family members did not report improvements in sun protection habits (Geller & Halpern, 2006). These findings are consistent with a number of different behavioral interventions that have successfully reduced sun protection practices (Glanz et al., 2002; Jackson & Aiken, 2006; Mahler et al., 2005; Mahler, Kulik, Butler, Gerrard, & Gibbons, 2008) and extend previous research to illustrate that tailored interventions can improve sun protection practices among FDRs of patients with melanoma.

Overall, our findings suggest that the tailored intervention was more effective than the generic intervention. The tailored intervention was viewed as more personalized, novel, valuable, and perceived as prompting participants to think more about changing their health practices than the generic intervention. These findings are consistent with previous research (e.g., Kreuter, Oswald, Bull, & Clark; 2000; Campbell et al., 1994). However, the effects of tailoring differed across the three behaviors with stronger effects noted on TCE and sun protection. An examination of the materials suggests that the tailored SSE pamphlet was more similar to the generic print intervention in that both focused on instructions about how to correctly perform an SSE. Other than the tailored content addressing benefits and barriers to SSE, the generic and tailored interventions were more similar in their content than the materials for TCE and sun protection. Future studies may improve effects by perhaps expanding tailoring on benefits and barriers to SSE and identifying additional attitudinal correlates associated with this behavior to improve the treatment effect.

The second aim was to evaluate possible mediators of treatment effects. We identified one mediator, TCE intentions, for the tailored intervention’s effects on TCE. This study represents the first examination of mechanisms for changes in TCE and, therefore, comparisons with previous work cannot be done. Sun protection intentions, sun protection benefits, and sunscreen self-efficacy mediated the effects of the tailored intervention on sun protection habits. Our findings are consistent with prior research suggesting that intentions are beneficially affected by sun protection interventions (Mahler et al., 2005, 2008; Jackson & Aiken, 2006) as well as studies indicating that sun protection intentions and sunscreen self-efficacy mediate the effects of sun protection interventions (Jackson & Aiken, 2006). Our findings provide support for the theoretical underpinnings of the tailored intervention in that intentions, benefits, and self-efficacy served as mechanisms for effects on sun protection habits and intentions mediated effects for TCE. Our findings have some potential clinical implications in that it may be important to bolster individuals’ confidence that they can incorporate sunscreen into their daily life. The fact that intentions mediated the effects of the tailored intervention on TCE and sun protection habits suggests that intentions could be targeted in behavioral interventions. For example, implementation intentions whereby participants are asked to commit to a time and place to have a TCE could be incorporated to enhance participants’ commitment to their intention to have screening. This intervention has been used effectively in other health behavior interventions (e.g., Arbour & Ginnis, 2009). However, a number of proposed variables were not mediators for the tailored intervention’s effects. Because these factors cover the gamut of possible factors included in most health behavior models, future research should use interview methods to uncover other possible mechanisms potentially responsible for the tailored intervention’s effects.

The research has a number of strengths. We targeted a population at higher risk for CM not only because of a family history of this disease but because of behavioral risk factors. Our sample size was large and attrition was low (13.3%). We employed a multiple-risk reduction approach that was based upon theoretical and empirical considerations and compared publicly-available pamphlets with tailored pamphlets to determine if the widely-available information was just as effective. Counseling session treatment fidelity was high and the majority of participants received the counseling call. We evaluated long-term outcomes and mechanisms of change. Both interventions were evaluated highly.

However, there were weaknesses. An immediate post-intervention assessment of mediators was not conducted and therefore the possibility that changes in behavior preceded changes in attitudes cannot be ruled out. Self-reports of SSE and sun protection habits were used and we were not able to confirm TCEs in about a quarter of the reported procedures due to problems obtaining confirmation. The acceptance rate among eligible family members was 50% which is lower than other studies (Geller et al., 2008). The majority of participants had medical insurance which may have biased the post-intervention uptake of TCE. Half of participants were offspring which may have biased the study’s results in favor of younger individuals. Participants were enrolled across seasons which may have affected the effects on sun protection habits. Approximately 44% of eligible FDRs approached participated which limits generalizability of the findings. The tailored counseling call was longer in duration than the generic call and it is possible that the greater level of interaction between counselor and participant and greater length accounted for the superiority of the tailored intervention. Although the importance of discussing TCE and SSE with the affected relative was addressed in the tailored intervention, communication about risk was not assessed as a possible mediator. It is possible that discussion with the affected proband was a mechanism of change in the tailored arm and should be assessed in future studies.

A next step in the research could be to disseminate the tailored intervention into the clinical setting such as a community dermatology clinic. However, dissemination may pose unique challenges. One major challenge is accessing relatives. Community recruitment through dermatology practices rather than cancer center clinics would necessitate reliance upon proband recruitment of their family members. This method of recruitment may be challenging. Even with researchers recruiting family members into the present study, acceptance rates were not high. It may be even more difficult for probands to garner sufficient interest among their relatives. A second challenge is cost. It may be expensive to obtain baseline survey data that can be used for producing tailored print and it may not be cost-effective to train individuals to deliver such an intervention. We did not conduct a cost effectiveness analysis of this intervention. However, Campbell and colleagues (2009) have recently shown that, while more costly, a combined tailored print and motivational interviewing intervention was more cost-effective than either intervention alone for promoting fruit and vegetable consumption. Future research should evaluate cost-effectiveness of the tailored print and telephone counseling intervention. Dissemination for the tailored print would not be as difficult as the telephone counseling which might be challenging to disseminate into the community setting due to the resources and personnel needed to deliver a telephone intervention. Future research might examine the cost-effectiveness of the tailored print and telephone counseling separately. In clinical settings where resources are limited, the choice of tailored print alone may be reasonable but we do not yet know if the tailored print alone had significant effects when compared with generic prints.

In summary, this study was one of the first to address skin cancer risk reduction practices in a sample of family members of patients with melanoma who were non-adherent to risk reduction practices. Publicly-available print information along with an education session may improve SSE in this population of at-risk individuals. However, more intensive intervention efforts are likely necessary to promote TCE and may also prove beneficial for increasing sun protection habits.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by CA 107312 to Sharon Manne and CA006927 to Fox Chase Cancer Center. We would like to thank Liza Brown, Rebecca Dunn, Timothy Estrella, Janelle Garcia, Julie Hess, Jennifer Iacovone, Amber Karlins, Shahbaz Khan, Tracy Max, Rebecca Moore, Nancy Rohowyz, Kristen Sorice, Kathryn Volpicelli, Sharon Voros, Emily Weitberg, and Sara Worhach for data collection. Tracy Max, Rebecca Moore, and Kathryn Volpicelli provided telephone counseling. Maryann Krayger provided technical assistance in preparation of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/hea

Contributor Information

Sharon Manne, Fox Chase Cancer Center

Paul B. Jacobsen, Moffitt Cancer Center

Michael Ming, University of Pennsylvania

Gary Winkel, City University of New York

Sophie Dessureault, Moffitt Cancer Center

Stuart R. Lessin, Fox Chase Cancer Center

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Akaike H. Information theory as an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In: Petrov BN, Csaki F, editors. Second International Symposium on Information Theory. Akademiai Kiado; Budapest, Hungary: 1973. pp. 228–267. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Dermatology. The Complete Skin Exam. 2003 https://secure.aad.org/marketplace/searchresults.aspx?k=the+complete+skin+exam.

- American Academy of Dermatology. [Accessed, October 28, 2009];2009 http://www.aad.org/public/epublications/pamphlets/sun_sun.html.

- American Cancer Society. Why You Should Know About Melanoma 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Arbour K, Martin Ginnis K. A randomised controlled trial of the effects of implementation intentions on women’s walking behaviour. Psychology and Health. 2009;24:49–65. doi: 10.1080/08870440801930312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzarello L, Jacobsen P, Dessureault S, Puleo PA. Skin cancer screening among individuals at familial risk of melanoma. Paper presented at the Society of Behavioral Medicine; Baltimore, Maryland. Mar 24–27, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Balch CM. Cutaneous melanoma: prognosis and treatment results worldwide. Seminars in Surgical Oncology. 1992;8(6):400–414. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980080611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow A. Thickness, cross-sectional area and depth of invasion in the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Annals of Surgery. 1970;172:902–908. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197011000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brug J, Steenhuis I, Van Assema P, de Vries H. The impact of a computer-tailored nutrition intervention. Preventive Medicine. 1996;25:236–242. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M, Carr C, DeVellis B, Switzer B, Biddle A, Amamoo A, Walsh J, Zhou B, Sandler R. A randomized trial of tailoring and motivational interviewing to promote fruit and vegetable consumption. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;28:71–85. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M, DeVellis BM, Strecher VJ, Ammerman AS, DeVellis RF. Improving dietary behavior: The effectiveness of tailored messages in primary care settings. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(5):783–787. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.5.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for school programs to prevent cancer. MMWR 2002. 2009;51(RR-4):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fears T, Bird C, Guerry D, Sagebiel RW, Gail M, Elder D, et al. Average midrange ultraviolet radiation flux and time outdoors predict melanoma risk. Cancer Research. 2002;62(14):3992–3996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ford D, Bliss JM, Swerdlow AJ, Armstrong BK, Franceschi S, Green A, et al. Risk of cutaneous melanoma associated with a family history of the disease. The International Melanoma Analysis Group. International Journal of Cancer. 1995;62(4):377–381. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller AC, Halpern AC. The benefits of skin cancer prevention counseling for parents and children. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2006;55(3):506–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller AC, Zwirn J, Rutsch L, Gorham SA, Viswanath V, Emmons KM. Multiple levels of influence in the adoption of sun protection policies in elementary schools in Massachusetts. Archivesin Dermatology. 2008;144(4):491–496. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Lew RA, Song V, Ah Cook V. Factors associated with skin cancer prevention practices in a multiethnic population. Health Education and Behavior. 1999;26:344–359. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Schoenfeld E, Shigaki D, Evensen D. Results of project Scape, a randomized trial of tailored communications for skin cancer prevention. Paper presented at the 130th Annual Meeting of APHA; Philadelphia, PA. 2002. Nov 9–13, [Google Scholar]

- Howe HL, Wingo PA, Thun MJ, Ries LA, Rosenberg HM, Feigal EG, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer (1973 through 1998), featuring cancers with recent increasing trends. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2001;93(11):824–842. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Aiken LS. A psychosocial model of sun protection and sunbathing in young women the impact of health beliefs, attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy for sun protection. Health Psychology. 2000;19(5):469–478. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Aiken LS. Evaluation of a multicomponent appearance-based sun-protective intervention for young women: uncovering the mechanisms of program efficacy. Health Psychology. 2006;25(1):34–46. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh H, Geller A, Miller D, Caruso A, Gage I, Lew R. Who is being screened for melanoma/skin cancer? Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1991;24:271–277. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70041-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter M, Oswald D, Bull F, Clark E. Are tailored education materials always more effective than non tailored materials? Health Education Research. 2000;14:305–315. doi: 10.1093/her/15.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkus I, Rimer B, Halabi S, Strigo T. Can tailored interventions increase mammography us among HMO women. American Journal of Prevented Medicine. 2000;18(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Taylor & Francis Group; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mahler H, Fitzpatrick B, Parker P, Lapin A. The relative effects of a health-based versus an apperance-based intervention designed to increase sunscreen use. Am J Health Promotion. 1997;11(6):426–429. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-11.6.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler HI, Kulik JA, Butler HA, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX. Social norms information enhances the efficacy of an appearance-based sun protection intervention. Social Science Medicine. 2008;67(2):321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler HI, Kulik JA, Harrell J, Correa A, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Effects of UV photographs, photoaging information, and use of sunless tanning lotion on sun protection behaviors. Archives in Dermatology. 2005;141(3):373–380. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne SL, Coups EJ, Winkel G, Markowitz A, Meropol NJ, Lesko SM, et al. Identifying cluster subtypes for intentions to have colorectal cancer screening among non-compliant intermediate-risk siblings of individuals with colorectal cancer. Health Educ Res. 2009;24(5):897–908. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne SL, Lessin S. Sun protection and skin self-examination among patients with malignant melanoma. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29(5):419–434. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne SL, Fasanella N, Connors J, Floyd B, Wang H, Lessin S. Sun protection and skin surveillance practices among relatives of patients with malignant melanoma: Prevalence and predictors. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers RE, Ross E, Jepson C, Wolf TA, Balshem AM, Millner L, et al. Modeling adherence to colorectal cancer screening. Preventive Medicine. 1994;23:142–151. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis L, Eisner MP, Kosary C. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2002. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2005. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2002/, based on November 2004 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes AR, Weinstock MA, Fitzpatrick TB, Mihm MC, Jr, Sober AJ. Risk factors for cutaneous melanoma. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1987;258(21):3146–3154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skin Cancer Foundation. “Get Smart! Go Under Cover.” Pamphlet. 2005 http://webservices.advanceware.net/skincancerb2c/home.aspx.

- Skin Cancer Foundation. “Simple Steps to Sun Safety” Pamphlet. 2005 http://webservices.advanceware.net/skincancerb2c/home.aspx.

- Skin Cancer Foundation. “Skin Cancer: If You Can Spot it, You Can Stop It.” Pamphlet. 1992 http://webservices.advanceware.net/skincancerb2c/home.aspx.

- Skin Cancer Foundation. [Accessed November 3, 2009];2009 http://www.skincancer.org/self-examination/