Abstract

Objective

To identify facilitative strategies that could be used in developing a tobacco cessation program for community dental practices.

Methods

Nominal group technique (NGT) meetings and a card-sort task were used to obtain formative data. A cognitive mapping approach involving multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis was used for data analysis.

Results

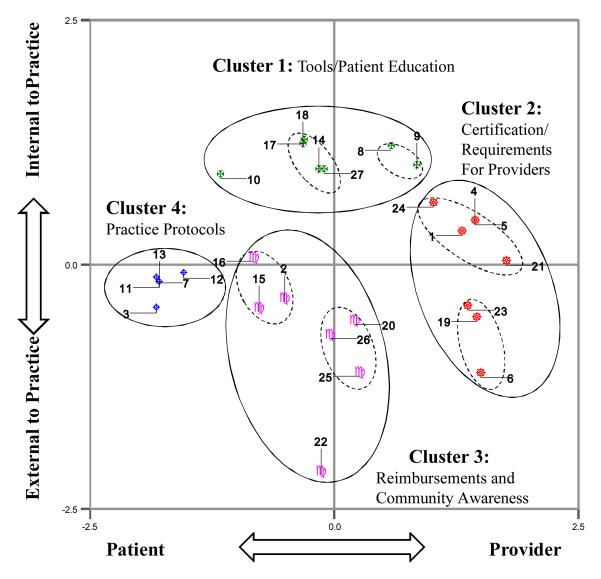

Three NGT meetings conducted with 23 dental professionals yielded 27 nonredundant facilitative strategies. A 2-dimensional 4-cluster cognitive map provided an organizational framework for understanding these strategies.

Conclusion

Views of the target population solicited in a structured format provided clear direction for designing a tobacco cessation intervention.

Keywords: Smoking Cessation, Nominal Group Technique, Card Sort, Cognitive Mapping

INTRODUCTION

Provider-delivered brief tobacco cessation advice increases rates of cessation.1 Based on the current Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence guideline, all health professionals should provide brief tobacco cessation advice to increase tobacco cessation rates among their patients.2 Although rates of cessation advice have increased in physician practices, brief provider-delivered cessation advice interventions have not been widely translated into other health care settings. Increasing diffusion and uptake of guideline-adherent approaches to reducing tobacco use is essential.

Rates of provider-delivered brief tobacco cessation advice in dental practice lags behind medical practice, although in research studies dentists and hygienists have used a variety of smoking cessation practices ranging from prescribing pharmacotherapy to brief counseling, and each has had positive results.3 Many dental providers express concern that their patients might be turned off by receiving tobacco cessation advice, even though studies have shown that smokers who receive cessation advice report greater satisfaction with the dental care they receive.4,5 In dental practices, rates of cessation advice provided to smokers range from 13% to 50% of dentists reporting some routine tobacco cessation advice,6 considerably lower than what has been reported in medical practices.7 There is a need to design/develop interventions that will promote tobacco prevention efforts by dental providers.8

Some studies have addressed barriers to tobacco cessation counseling for dentists.9,10 Barriers to tobacco cessation counseling efforts include lack of training,9 lack of time and reimbursement,10 lack of knowledge, organizational issues within the practice, a fatalistic attitude toward tobacco counseling, and patient hostility. Because many dental patients are self-pay, patient issues are critical to dental practice behavior. Less research has focused on specific strategies that could be valuable in facilitating tobacco cessation advice in dental practice.

Interventions to change provider behaviors or practice patterns are often developed using an expert, or etic, perspective based on some theoretical framework and constructs that may or may not have meaning or relevance for the targeted population.11,12 However, strategies for intervention development that rely exclusively on etic or outsiders' perspectives are likely to have limited efficacy. We believe that to be most useful, intervention strategies must also incorporate emic perspectives, or those views held by insiders or those who are most familiar with a problem in its usual environment.

In the context of developing an intervention intended to increase delivery of brief provider-delivered tobacco cessation advice in dental practice, we conducted a series of formative exercises with dental providers and tobacco cessation experts. In this article, we present results from formative research that was conducted using an emic perspective as a basis for developing a tobacco-cessation quality-improvement intervention for dentists and hygienists in dental practices.

METHODS

Study Design

This research is based on a cognitive mapping approach involving 2 distinct phases (phase I and phase II) of primary data collection and a sequence of data analytic procedures to elicit and systematically organize provider-defined strategies for increasing brief tobacco counseling during dental visits. During the first phase of a cognitive mapping approach, knowledgeable informants are asked to generate and prioritize responses to a single specific question using nominal group technique (NGT). The second phase of a cognitive mapping approach involves a card-sorting exercise and a sequence of analyses to understand how responses from phase I are represented cognitively. This approach has been used in several different settings as a formative strategy to develop health care quality improvement initiatives and health promotion and educational interventions.13-21 Because, phase II data collection derives from phase I results, the methods and results for each phase are presented separately.

The study was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board, and data were collected and analyzed in 2006 through 2007.

Phase I: Identifying Tobacco Cessation Strategies

Dental professionals were recruited from across Alabama, Georgia, and Florida from dental practices participating in the Dental Practice-Based Research Network (DPBRN), an NIH-funded practice-based research network. Each of the 23 dental professionals participated in a single NGT meeting lasting approximately 60 minutes. We conducted 3 NGT meetings of dental professionals (Dentist Panel 1: N = 8; Dentist Panel 2: N = 5; Hygienist Panel: N = 10). The NGT employs a highly structured approach that limits the level of direct interaction among participants and, unlike traditional focus group meetings, addresses one overarching question.22-24 Given the central importance of this question, we conducted several cognitive interviews with 4 dentists and 2 hygienists to evaluate potential questions for comprehension and their ability to elicit relevant responses.25,26 Based on the results of these interviews, the question selected for use in the 3 NGT panel meetings was “What sorts of things could be done to ensure that as a routine part of every dental visit all patients are asked about their tobacco use and/or advised to quit using tobacco?”

Conducting the NGT meetings

To increase geographic diversity of participants, the NGT meetings were conducted using a synchronous Internet-based virtual NGT meeting room and basic long-distance teleconference calling. Participants accessed the Internet site and were “seated” at a virtual table, where they were able to see the names of the other participants.27 Prior to the facilitation of NGT, a brief introduction of the purpose of this meeting, explanation of NGT process, and how to navigate within the virtual meeting room was provided. Next, the NGT facilitator (RMS, one of the authors) asked participants to work independently for approximately 5 minutes to develop their own lists of concise statements/phrases in response to the above question that was posted to their monitors. To identify a comprehensive array of responses, participants were encouraged to think outside the realm of their own experiences and consider all strategies they or other dental professionals would find helpful. Then, they presented their responses to the group using a discussion-free round-robin approach that involved having each participant, in turn, present a single response to the group without providing any rationale, justification, or explanation for the response. To help participants recollect previously nominated responses and avoid response repetition, the session facilitator recorded each response verbatim and immediately posted it online to a virtual flip chart. Nomination activity concluded when participants were unable to generate further responses. Using a round-robin technique to present responses in the absence of any discussion has been shown to encourage open disclosure, produce a high volume of varied responses, and provide an equal opportunity for all participants to present their ideas to the group.22,28

To ensure the responses were understood from a common perspective, each was briefly discussed for clarification but not for the purposes of evaluation. The list of responses on the virtual flip chart shown on each participant's monitor was edited to accommodate points of clarification and/or elaboration and an occasional recommendation to combine responses that the group felt were highly redundant.

After the response list was finalized, each participant was asked to anonymously select 3 responses reflecting what he or she considered to be the most important strategies for increasing tobacco counseling during dental visits. Participants were then directed to individualized online forms showing their own selections and asked to rank these in terms of importance. For each participant, the program assigned 3 votes to the most important strategy, 2 votes to the second most important strategy, and 1 vote to the third most important strategy. The votes assigned to each individually selected response then were automatically aggregated across participants to derive a group result (Table 1-3). Before adjourning each meeting, the results, reported as bar charts showing vote totals were presented to the group for final comments.

Table 1.

Strategies to Ensure Patients Are Asked About Tobacco Use and Advised to Quit During Dental Visits: Dentist Panel 1 (N = 8)

| Strategies | Number of Votes a |

Individual Weighted Votes b |

Sum of Weighted Votes |

Weighted Votes (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educate dentists about smoking cessation programs | 5 | 3,3,3,3,2 | 14 | 29.17 |

| Involve the ADA in developing a national marketing campaign that informs the public about the expertise of dental providers in tobacco cessation efforts |

2 | 3,3 | 6 | 12.50 |

| Ensure that hygienists incorporate patient's tobacco use into their patient information | 3 | 3,1,1 | 5 | 10.42 |

| Include standard questions about tobacco use in patient histories | 2 | 2,3 | 5 | 10.42 |

| Emphasize the importance of oral cancer screenings to dentist and patients | 2 | 2,2 | 4 | 8.33 |

| Provide a comprehensive smoking history or tobacco use section on a standard questionnaire for the practitioner to use with every patient |

2 | 2,1 | 3 | 6.25 |

| Train staff to ask follow-up questions about tobacco use and then have the dentist follow-up with questions to emphasize the importance |

1 | 2 | 2 | 4.17 |

| Use patient history as a prompt to discuss tobacco use with new patients | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4.17 |

| Provide periodic updates, including specific statistics, facts, and figures relating to dental pathologies, to all practitioners reminding them of the importance of giving patients tobacco use information |

2 | 1,1 | 2 | 4.17 |

| Use a model or computer program to show patients the consequences of oral cancer (tumors, bone loss, etc) and the effects of continued tobacco use (tooth loss, stain, etc) |

1 | 2 | 2 | 4.17 |

| Post “dangers of smoking” signs throughout the office where patients can view them | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2.08 |

| Delegate tobacco use questions to hygienists as part of recall/recare | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2.08 |

| Provide dentists with information about all of the modalities that can be used to encourage patients to stop smoking/using tobacco |

1 | 1 | 1 | 2.08 |

| Total | 24 | 48 | 100.00 |

There were 26 responses generated by Dentist Panel I. We list only strategies endorsed by at least one participant as one of his or her 3 most important strategies.

Each panel member was allotted 3 votes (weighted: 1=third most important, 2= second most important, and 3= most important) to assign to a set of 3 individually selected strategies.

This percentage is calculated using the sum of weighted votes for each strategy divided by the total of the weighted votes from all participants.

Table 3.

Strategies to Ensure Patients Are Asked About Tobacco Use and Advised to Quit During Dental Visits: Hygienist Panel (N = 10)

| Strategies | Number of Votes a |

Individual Weighted Votes b |

Sum of Weighted Votes |

Weighted Votes (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cue dentists about the legal consequences of failing to screen and document patient tobacco use on patient history form |

6 | 1,2,2,2,3,3 | 13 | 21.67 |

| Make it mandatory for dentists to participate in annual continuing education that addresses smoking cessation |

4 | 1,2,3,3 | 9 | 15.00 |

| Make it profitable to the dental office to ask patients about their smoking activities | 2 | 3,3 | 6 | 10.00 |

| Include questions about smoking on history form | 3 | 1,2,2 | 5 | 8.33 |

| Conduct courses to prepare dental providers in the area of tobacco cessation | 2 | 1,3 | 4 | 6.67 |

| Have brochures available to show the dangers of smoking to the patient | 1 | 3 | 3 | 5.00 |

| Tell patients that tobacco use makes periodontal disease worse as part of the periodontal protocol |

1 | 3 | 3 | 5.00 |

| Provide dental staff with an incentive (not just a good feeling) for their smoking cessation efforts |

2 | 1,2 | 3 | 5.00 |

| Get insurance programs to pay for smoking cessation programs | 2 | 1,2 | 3 | 5.00 |

| Provide smoking information to dental offices through lunch and learn programs sponsored by drug companies |

1 | 3 | 3 | 5.00 |

| Develop a smoking cessation certification program | 2 | 1,2 | 3 | 5.00 |

| Have the dental board monitor dental practices to ensure practices abide by specific guidelines |

1 | 2 | 2 | 3.33 |

| Make tobacco cessation programs available to dentists | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.67 |

| Have products available in dental office so patients can leave with a strategy to quit smoking |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1.67 |

| Have drug companies provide free advertising for dental practices endorsing them as a smoke-free dental office |

1 | 1 | 1 | 1.67 |

| Total | 30 | 60 | 100.00 |

There were 26 responses generated by Dentist Panel I. We list only strategies endorsed by at least one participant as one of his or her 3 most important strategies.

Each panel member was allotted 3 votes (weighted: 1= third most important, 2= second most important, and 3= most important) to assign to a set of 3 individually selected strategies.

This percentage is calculated using the sum of weighted votes for each strategy divided by the total of the weighted votes from all participants.

When appropriately used, the highly structured format of the NGT fosters group productivity and eliminates much of the ambiguity and process loss that often occurs with less structured, highly interactive focus group or traditional brainstorming approaches.22,28 Unlike focus groups, which require audiotape recording and the somewhat interpretative analysis of transcripts, the results from an NGT meeting provide a set of objective and easily interpretable prioritized responses to a direct question.

Phase I Results From Nominal Group Technique Meetings

NGT meeting with dentist panel 1

In the first NGT meeting, a group of 8 dentists identified strategies to ensure that all patients are asked about their tobacco use and/or advised to quit using tobacco as a routine part of every dental visit. Of this total, the 8 panelists endorsed 13 strategies as relatively more important than others (Table 1). In this meeting, there was a considerable agreement among the panelists regarding the importance of the identified strategies as indicated by the number of panelists endorsing selected strategies (number of votes) and the percentage of total weighted votes assigned to these strategies. Over 60% of the total weighted votes available for prioritization was assigned to just 4 responses: “educate dentists about smoking cessation programs” (5 votes, 29.17%); “involve the ADA in a national marketing campaign that informs the public about the expertise of dental providers in tobacco cessation efforts” (2 votes, 12.50%); “ensure that hygienists incorporate patient's tobacco use into their patient information” (3 votes, 10.42%); and “include standard questions about tobacco use in patient histories” (2 votes, 10.42%). Further, 4 of the 8 panelists thought “educating dentists about smoking cessation programs” was the most important strategy.

NGT meeting with dentist panel 2

A second NGT meeting conducted with a different group of 5 dentists elicited 23 strategies for increasing tobacco screening and counseling during dental visits. From this total, participants selected and subsequently prioritized 12 strategies (Table 2). As indicated by the vote totals and the percentage of total weighted votes, Dentist Panel 2 participants “endorsed include questions about tobacco use on health history form” (4 votes, 23.33%); “ask the patient about their own and their family's tobacco use and ask if they want help” (2 votes, 16.67%); and “discuss the role of tobacco use when performing cancer screening” (2 votes, 16.67%) as relatively more important than the other strategies identified during the session. In aggregate, these 3 strategies received 8 of the 15 available individual vote assignments and about 57% of the total weighted votes.

Table 2.

Strategies to Ensure Patients Are Asked About Tobacco Use and Advised to Quit During Dental Visits: Dentist Panel 2 (N= 5)

| Strategies | Number of Votesa |

Individual Weighted Votes b |

Sum of Weighted Votes |

Weighted Votes (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Include questions about tobacco use on health history form | 4 | 1,2,3,1 | 7 | 23.33 |

| Ask the patients about their own and their family's tobacco use and ask if they want help |

2 | 2,3 | 5 | 16.67 |

| Discuss the role of tobacco use when performing cancer screening | 2 | 3,2 | 5 | 16.67 |

| Have hygienist screen and counsel patients | 1 | 3 | 3 | 10.00 |

| Develop a cancer-screening mechanism that patients could take home and bring back to the dentist |

1 | 3 | 3 | 10.00 |

| Advertise to the public about tobacco-screening services available to dentist offices |

1 | 2 | 2 | 6.67 |

| Conduct an oral cancer screening day that is open to the public and allows any dentist to participate |

1 | 2 | 2 | 6.67 |

| Provide tobacco and oral cancer literature to the patients when they are waiting for treatment |

1 | 1 | 1 | 3.33 |

| Regularly counsel adolescents (age 11-17) about the dangers of smoking | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3.33 |

| Provide patients with visual materials that illustrate the consequences of oral and lunch cancer |

1 | 1 | 1 | 3.33 |

| Total | 15 | 30 | 100.00 |

There were 26 responses generated by Dentist Panel I. We list only strategies endorsed by at least one participant as one of his or her 3 most important strategies.

Each panel member was allotted 3 votes (weighted: 1= least important, 2= second most important, and 3= most important) to assign to a set of 3 individually selected strategies. .

This percentage is calculated using the sum of weighted votes for each strategy divided by the total of the weighted votes from all participants.

NGT meeting with dental hygienists panel

In the third NGT meeting, a group of 10 dental hygienists identified 38 strategies. This group endorsed 15 strategies as relatively more important than others (Table 3). Among the strategies identified as important, 8 of 15 were endorsed as important by at least 2 panel members. As indicated by the number of panelists endorsing strategies and the total weighted votes, the 5 strategies identified as most important by this panel were “cue dentists about the legal consequences of failing to screen and document patient tobacco use on patient history form” (6 votes, 21.67%); “make it mandatory for dentists to participate in annual continuing education that addresses smoking cessation” (4 votes, 15.00%); “make it profitable to the dental office to ask patients about their smoking activities” (2 votes, 10.00%); “include questions about smoking on history form”(3 votes, 8.33%); and “conduct courses to prepare dental providers in the area of tobacco cessation” (2 votes, 6.67%). Together, these 5 strategies received about 62% of total weighted votes.

Phase II: Mapping of Tobacco Cessation Strategies

Card-sort task

To derive a schema for organizing tobacco cessation strategies identified by dental professionals, we developed an unforced card-sorting task (Q-sort).29, 30 For this task, we recruited 20 content experts (physicians, psychologists, dentists, and hygienists) who were tobacco researchers, public health tobacco workers, health educators, and dental health professionals from academic institutions across the United States. This data collection approach involved having experts sort a set of 27 index cards, each of which was labeled with a strategy generated from the NGT meetings. Each expert was instructed to sort the cards into at least 2 but not more than 10 piles based on how he or she perceived the strategies to be similar. The data from each completed card sort were aggregated across all experts to form a group co-occurrence matrix. This matrix indicated the number of times the experts sorted each strategy together with every other strategy and provided data for calculating similarities/distances among all pairs of strategies.

Phase II Data Analyses

Multidimensional scaling. The similarity measures derived from the group co-occurrence matrix were modeled using nonmetric multidimensional scaling (MDS ALSCAL) based on squared Euclidean distances. 29 We used the MDS analysis to model the relative distances between strategies within a multidimensional space defined by axes that are assumed to represent criteria used by the experts in making decisions about how the strategies should be sorted.

The derived MDS solution was evaluated by examining specific goodness-of-fit criteria including S-stress and RSQ values. The value of S-stress indicates the level of error or “stress” that results from the discrepancies between the actual distance data (ie, observed similarities of pairs of strategies) and the modeled representation of those data (ie, a map of calculated interpoint distances between pairs of strategies). The value of RSQ is an indication of the extent to which the derived spatial representation of strategies corresponds to the observed similarities in the data. As a rule, values of S-stress less than 0.15 and values of RSQ greater than 0.90 are indications of close correspondence between modeled and observed data.31

Hierarchical cluster analysis

Cluster analysis is a technique that is frequently used in concert with MDS to analyze data that are based on the perceptions of similarity and was used in this study to identify groups or clusters of homogenous strategies. The MDS results include coordinates defining the location of each strategy within a derived multidimensional space and were used as data for a cluster analysis that was performed.32 MDS and cluster analyses often have different interpretations. For example, 2 objects can appear in close proximity in an MDS space and yet be assigned to different clusters. Moreover, an object can appear on one extreme of an MDS space and yet be clustered with objects at the opposite end of that space. Although the results obtained from an MDS and cluster analysis of the same similarity can appear contradictory, it should be noted that the 2 approaches have different but complementary purposes. The purpose of MDS concerns the relative ordering of objects (eg, strategies) along a continuum of more or less whereas the principal task of cluster analysis is to assign objects to exclusive membership categories.32 The interpretive goal of MDS is to find meaning from the ordering of objects along a dimension.

The results from the combined MDS/cluster analysis are represented geometrically by a map reflecting different aspects of the perceived similarity of objects. For our analysis, pairs of strategies perceived as similar (ie, those frequently sorted together) are represented as points that are relatively closer together on the map than strategies that are viewed as dissimilar. When MDS and cluster analysis are used together, it is possible to discern both the relative ordering of clusters and the ordering of individual strategies within each cluster along each dimension.

Results From Cognitive Mapping (MDS/Cluster Analysis)

The measures of overall goodness-of-fit for the MDS analysis indicated that a 2-dimensional solution provided a better model (S-stress =.12, R2 =.91) than a one-dimensional solution and was comparable in fit but more interpretable than a 3-dimensional solution. The MDS solution can be interpreted by examining how strategies are arrayed along the horizontal and vertical dimensional axes. Interpretation of the map is facilitated by contrasting the meaning of strategies located at the extremes of each dimension.

For these results, we interpreted one dimension of the MDS solution as relating to either the providers or the patients (Figure 1). The horizontal axis is anchored on the left (patient) by “Include a tobacco use question on health history form” and on the right (provider) by “Conduct tobacco cessation education programs for all dental providers.”

Figure 1. Cognitive Map of Tobacco Cessation Strategies.

Note: The enclosure shapes and colors are used only to distinguish strategies within each derived cluster.

Numbers Representing 27 Strategies Used for Multidimensional Scaling

1 Educate dentists about smoking cessation programs that they can develop for implementation in their practice

2 Involve the ADA in developing a marketing campaign that informs the public about the expertise of dental providers in tobacco cessation efforts

3 Include a tobacco use question on health history form

4 Provide materials that impress upon dentists the importance of oral cancer screenings

5 Provide practitioners with regular updates of statistics as they relate to tobacco-related pathologies

6 Require mandatory continuing education regarding tobacco use

7 Have staff and dentists work as a team for tobacco screening

8 Provide practices with models, materials, and computer programs to show consequences of tobacco use to patients

9 Provide practices with resources about available tobacco cessation programs for treatment or referral

10 Display graphical material throughout the office to inform patient of tobacco-related problems

11 Assign tobacco screening efforts to hygienist as part of patient recall, recare scheduling

12 Use cancer screening as an opportunity to discuss tobacco use with patients

13 Assign tobacco screening/counseling to hygienist and other dental staff

14 Provide practices with tobacco screening material that they could have patients complete at home

15 Develop TV and public awareness campaign informing the public of tobacco cessation efforts that can be provided by dentists

16 Have an oral cancer screening day

17 Provide practices with waiting room material regarding tobacco/oral cancer screening

18 Provide practices with a waiting room video that can show consequences of tobacco use

19 Cue dentists about the legal consequences of failing to screen and document patient tobacco use

20 Ensure it is “profitable” for the practice to screen and document patient tobacco use

21 Conduct tobacco cessation education programs for all dental providers

22 Make tobacco screening activities reimbursable

23 Develop a smoking cessation certification program for dental providers

24 Inform practices about tobacco cessation efforts through lunch and learn programs

25 Have the dental board monitor dental practices to ensure that tobacco cessation efforts are being conducted

26 Encourage drug companies to support dental provider efforts in smoking cessation

27 Provide practices with smoking cessation products that can be given to patients

The second dimension, represented on the vertical axis in Figure 1 relates to factors internal or external to the dental practice, was anchored at the extremes by items including “Make tobacco screening activities reimbursable” (external to practice) and “Provide practices with a waiting room video that can show consequences of tobacco use” (internal to practice).

The hierarchical cluster analysis revealed 4 distinct clusters to which each of the 27 tobacco cessation strategies was assigned exclusive membership. Because there are no assumptions that can be made about the distribution of the data used in this analysis, a subjective decision was made to interpret a 4-cluster solution. This decision was informed by examining the pattern in the agglomeration coefficients indicating which strategies were joined to form a cluster at different stages in the clustering and by visually inspecting the dendrogram and icicle plot.

The 4 clusters resulting from the hierarchical cluster analysis are superimposed on the multidimensional scaling map (Figure 1). An interpretation of the 4 clusters was made on the basis of the strategies composing each cluster (see individual strategies listed in the legend to Figure 1). Clockwise on Figure 1, the 4 clusters were interpreted to represent: tools and patient education materials, certification/requirements for providers, reimbursements and community awareness, and practice protocols.

DISCUSSION

By engaging dental professionals in formative research, we successfully identified a wide variety of issues that providers believed would facilitate the delivery of tobacco control in dental practice. As organized by our expert panel, the information solicited from providers suggests that interventions focused outside the practice to change policies and reimbursements related to tobacco control were also felt to be important by providers. Both providers and patients are appropriate and necessary targets for interventions.

Provider education was strongly endorsed as an important facilitator across panels of dental providers. Strategies involving training and education represented over 40% of the possible weighted votes in these 2 sessions. This finding is consistent with prior research, as surveys of dental providers have noted gaps in training.33 Providers who received tobacco cessation counseling training are likely to perceive fewer barriers to tobacco cessation counseling and are more likely to engage in counseling activities (i.e., asking and advising). Knowledge of approaches and development of skills for tobacco counseling are likely necessary, although not necessarily sufficient to increasing tobacco control in dental practice.

Dentists and hygienists also frequently requested tools to further support their efforts, including patient materials (patient handouts, models, videos) and practice materials (history forms). The providers also suggested standard protocols (e.g., “Assign tobacco screening/counseling to hygienist”). Practice reorganization strategies such as developing standard protocols are likely to be effective based on prior research in quality improvement.

Some recommended strategies may not be easily implemented. For example, a strategy to “cue dentists about the legal consequences of failing to screen” is more complex than some of the other issues. We could not find specific legal cases in which dentists were sued for lack of tobacco cessation counseling. Thus, this is more of a theoretical concern. In considering how to implement these strategies in an intervention, quality-improvement engineers should consider these comments within the context of what is feasible and practical in dental practice.

Our cognitive mapping also suggested that forces external to the practice are also critical to tobacco control in dental practice, representing one extreme of the 2-dimensional model. Reimbursements and certification issues represented 2of the 4 clusters identified. These results suggest that dental providers believe that outside regulation, monitoring, and funding are needed to move tobacco cessation activities forward in dental practices. In deciding to counsel smokers, dentists still must consider that many of their patients are self-pay. Thus, dentists may be more reluctant to provide sensitive counseling because they fear that patients will be dissatisfied. Although evidence suggests that dental patients value receiving tobacco cessation counseling, this may not be well known in practice. 34 In considering the decisional balance of dental providers, additional external supports (e.g., funding) may thus be needed to increase tobacco control.

Our formative assessment has several limitations. We purposefully recruited dentists and hygienists into our sample, but the number of providers participating in our nominal group technique meetings was limited, and their opinions, although valuable, may not be representative of all providers. Although there was some overlap, each meeting included unique strategies. Thus, theme saturation was not completely achieved, and the strategies proposed are not likely to be a comprehensive list.

A strength of the present study is the combination of perspectives. We have incorporated the views of 2 key informant groups: providers and experts in tobacco control and health services research by combining formative research methods. This framework offers a common basis for designing components of an intervention. Our approach and sample size did allow for an understanding of variations in opinions. Further research could include quantitative evaluations of provider characteristics that might influence dental-provider opinions regarding tobacco cessation counseling. In addition, similar research should be undertaken to identify patient- level perspectives of tobacco cessation counseling strategies. Patient-level data reflecting patients' views regarding what they perceived effective or ineffective intervention components would likely allow for developing a more comprehensive/integrated intervention approach to facilitate tobacco cessation counseling in dental practice.

We have used the results to create an Internet-delivered intervention for dental providers that includes a series of educational cases and a robust toolbox of downloadable tools for the practice. Ultimately, we will use the cognitive map derived from this formative research to test the impact of the various intervention strategies on the outcome of interest: increasing tobacco cessation advice by dental providers.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants R01-DA-17971 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) funded through RFA DE-03-007 “Translational Research In Dental Practice-Based Tobacco Control Interventions,” and grants U01-DE-16747 and U01-DE-16746 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) at the National Institutes of Health. The investigators were independent of the funding agency in terms of study design, intervention development, data collection and analyses, and interpretation. We would like to acknowledge the efforts of Andrea Hand Mathews in organizing and implementing the data collection for this project.

Contributor Information

Haiyan Qu, Department of Health Services Administration School of Health Professions University of Alabama at Birmingham 1530 3rd Ave South, WEBB 556 Birmingham, Alabama 35294-3361 Phone: 205-996-4940.

Thomas K. Houston, Division of Health Informatics and Implementation Science University of Massachusetts Medical School Office of Public Affairs and Publications (H1-580) 55 Lake Avenue North Worcester, MA 01655 Phone: (508) 856-8999.

Jessica H. Williams, Department of General Internal Medicine School of Medicine University of Alabama at Birmingham 1530 3rd Ave South, FOT 720B Birmingham, Alabama, 35294-3407 Phone: (205) 934-3007.

Gregg H. Gilbert, School of Dentistry, University of Alabama at Birmingham 1530 3rd Ave South, SDB 109, Birmingham, Alabama 35294-0007 Phone: (205) 934-5423.

Richard M. Shewchuk, Department of Health Services Administration School of Health Professions University of Alabama at Birmingham 1530 3rd Ave South, WEBB 560 Birmingham, AL 35294-3361 Phone: 205-934-4061 Fax: 205-975-6608.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gordon JS, Andrews JA, Lichtenstein E, Severson HH. The impact of a brief tobacco-use cessation intervention in public health dental clinics. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136(2):179–86. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence Guideline 2008 Updated. AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) Quick Reference Guidelines (online); Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=hstat2.chapter.28163. Accessed June 25, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warnakulasuriya S. Effectiveness of tobacco counseling in the dental office. J Dent Educ. 2002;66:1079–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quinn VP, Stevens VJ, Hollis JF, et al. Tobacco-cessation services and patient satisfaction in nine nonprofit HMOs. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conroy MB, Majchrzak NE, Regan S, et al. The association between patient-reported receipt of tobacco intervention at a primary care visit and smokers' satisfaction with their health care. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7:S29–S34. doi: 10.1080/14622200500078063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albert D, Ward A, Ahluwalla K, Sadowsky D. Address tobacco in managed care: a survey of dentists'knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):997–1001. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaén CR, Mcllvain H, Pol RL, et al. Tailoring tobacco counseling to the competing demands in the clinical encounter. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(10):859–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon JS, Lichtenstein E, Severson HH, Andrews JA. Tobacco cessation in dental settings: research findings and future directions. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25(1):27–37. doi: 10.1080/09595230500459495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu S, Pallonen U, McAlister AL, et al. Knowing how to help tobacco users: dentists' familiarity and compliance with the clinical practice guideline. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:144, 146,148. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carr AB, Ebbert JO. Interventions for tobacco cessation in the dental setting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;25(1):CD005084. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005084.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris M, Kwok L, Annes D, Lickel B. Views from inside and outside: integrating emic and etic insights about culture and justice judgment. Acad Manage Rew. 1999;24:781–796. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design Choosing Among Five Traditions. Vol. 1998. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: pp. 47–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trochim WMK. An introduction to concept mapping and planning and evaluation. Eval Program Plann. 1989;12:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frankel S. NGT + MDS: an adaptation of the nominal group technique for ill-structured problems. J Appl Behav Sci. 1997;33:543–51. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shewchuk RM, Rivera P, Elliott TR, Adams AM. Using cognitive mapping to understand problems experienced by family caregivers of persons with severe physical disabilities. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2004;11(3):141–150. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shewchuk RM, O'Connor SJ, Fine DJ. Building an understanding of the competencies needed for health administration practice. J Healthc Manag. 2005;50(1):32–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Safford MM, Shewchuk RM, Qu H, et al. Reasons for not intensifying medications: differentiating “clinical inertia” from appropriate care. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(12):1648–1655. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0433-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kristofco R, Shewchuk RM, Casebeer L, et al. Attributes of an ideal continuing medical education institution identified through Nominal Group Technique. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2005;25(3):221–228. doi: 10.1002/chp.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shewchuk RM, Franklin FA, Harrington KF, et al. Using cognitive mapping to develop a community-based family intervention. Am J Health Behav. 2004;28(1):43–53. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor WJ, Shewchuk R, Saag KG, et al. Toward a valid definition of gout flare: results of consensus exercises using Delphi methodology and cognitive mapping. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(4):535–543. doi: 10.1002/art.24166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castiglioni A, Shewchuk RM, Willett LL, et al. A pilot study using Nominal Group Technique to assess residents' perceptions of successful ward attending rounds. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1060–1065. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0668-z. (special issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delbecq AL, Van de Ven AH, Gustafson DH. Group Techniques for Program Planning: A guide to Nominal Group and Delphi Processes. Scott Foresman; Glenview: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller D, Shewchuk RM, Elliot T, Richards JS. Nominal group technique: a process for identifying diabetes self-care issues among patients and caregivers. Diabetes Educ. 2000;26(2):305–314. doi: 10.1177/014572170002600211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallagher M, Hares T, Spencer J, et al. The nominal group technique: a research tool for general practice? Fam Pract. 1993;10(1):76–81. doi: 10.1093/fampra/10.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sudman S, Bradburn NM, Schwartz N. Thinking about Answers: The Application of Cognitive Processes to Survey Methodology. Jossey Bass; San Francisco: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.UAB online NGT Access Available at: http://www.cme.uab.edu/brainstorm.asp. Accessed August 20, 2009.

- 28.Ruyter KD. Focus versus nominal group interviews: a comparative analysis. Marketing Intelligence & Planning. 1996;14(6):44–50. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenburg S, Kim MP. The method of sorting as a data-gathering procedure in multivariate research. Multivariate Behav Res. 1975;10:489–502. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr1004_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coxon APM. Sorting data:Collection and Data Analysis. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 1999. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kruskal JB, Wish M. Multidimensional Scaling. Sage Publications; Beverly Hills: 1978. pp. 1–93. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aldenderfer MS, Blashfield RK. Cluster Analysis: Methods and Applications. Sage Publications; Beverly Hills: 1984. pp. 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albert DA, Severson H, Gordon J, et al. Tobacco attitudes, practices, and behaviors: a survey of dentists participating in managed care. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(Suppl 1(2)):S9–S18. doi: 10.1080/14622200500078014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Victoroff ZK, Lewis R, Ellis E, Ntragatakis M. Patient receptivity to tobacco cessation counseling in an academic dental clinic: a patient survey. J Public Health Dent. 2006;66(3):209–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2006.tb02582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]