Abstract

Depressive symptoms may be associated with fluid and dietary non-adherence which could lead to poorer outcomes. The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between depressive symptoms and fluid and dietary adherence in 100 patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) receiving haemodialysis. A descriptive, cross-sectional design with a convenience sample of 100 patients with ESRD receiving maintenance haemodialysis completed instruments that measured self reported depressive symptoms and perceived fluid and dietary adherence. Demographic and clinical data and objective indicators of fluid and diet adherence were extracted from medical records. As many as two thirds of these subjects exhibited depressive symptoms and half were non-adherent to fluid and diet prescriptions. After controlling for known covariates, patients determined to have moderate to severe depressive symptoms were more likely to report non-adherence to fluid and diet restrictions. Depressive symptoms in patients with ESRD are common and may contribute to dietary and fluid non-adherence. Early identification and appropriate interventions may potentially lead to improvement in adherence of these patients.

Keywords: depressive symptoms, ESRD, haemodialysis, fluid and dietary non-adherence

Introduction

End stage renal disease (ESRD) is a life-threatening, potentially disabling disease with a growing adjusted prevalence rate that reached 1,500 per million Americans in 2007 (United States Renal Data System, 2009). The burden of ESRD is somewhat less onerous in European countries, as rates of ESRD in European countries are about 3 fold lower compared with US rates (Hallan, et al. 2006). ESRD is incurable and requires renal replacement therapy (RRT), such as haemodialysis (Finkelstein et al. 2002). Haemodialysis supports over 60% of patients with ESRD (Kugler et al. 2005). This therapy decreases the risk of death and improves survival; however, responses to the therapy depend on patient adherence to therapeutic regimens (Kutner, et al. 2002). Adherence to the prescribed therapy may be influenced by the presence of depression, particularly in patients with a chronic disease such as ESRD (Di Matteo, et al. 2000).

Depression and depressive symptoms are the most common psychological complication in patients with ESRD receiving haemodialysis with prevalence ranging from 20% to 90% (Koo et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2004; Taskapan et al. 2005). Patients with depressive symptoms report greater feelings of hopelessness, compromising cognitive abilities. Hopelessness, cognitive distortions and fatigue produce negative expectations of the future that may affect individual ability to carry out prescribed therapies and lead to inadequate fluid and dietary adherence behaviours (Christensen & Ehlers, 2002).

There are inconsistent findings about the relationship between depressive symptoms and fluid and dietary adherence in patients with ESRD. Sensky et al. (1996) found that younger depressed patients had higher pre-dialysis serum potassium levels. Akman et al. (2007) found double the likelihood of dietary non-adherence in depressed ESRD patients when compared to patients without depression. However, Pang and colleagues (2001) found no association between depressive symptoms and interdialytic weight gain in a group of Chinese haemodialysis patients. These contrary results were probably due to several factors.

Depression was measured using different instruments and the level of depressive symptoms considered significant varied by study.

Attitudes about depression and reporting of mood disorders may vary by culture and influence patient reporting, particularly when depression is a stigmatised condition (Koo et al. 2003; Lee et al. 2004; Soykan et al. 2004; Vazquez et al. 2005).

Studies relied on a single measure of dietary adherence in patients with ESRD (Pang, Ip, & Chang, 2001; Taskapan et al., 2005).

Although, no gold standard measure of adherence to fluid and dietary restrictions exists, it is frequently evaluated by the determination of interdialytic weight gain and measurement of serum potassium, phosphorus, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and/or self report questionnaires in research and clinical practice (Durose et al. 2004; Kara, et al. 2007).

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the relationship between depressive symptoms and fluid and dietary adherence using objective biomarkers and self report measures in patients with ESRD receiving haemodialysis who had not been previously diagnosed with depression. The specific aims of the study were to determine:

The prevalence of depressive symptoms and fluid and diet adherence in patients with ESRD receiving maintenance haemodialysis;

Whether depressive symptoms were an independent predictor of fluid and dietary non adherence after controlling for age, residual renal function, co-morbidities, perceived social support, dialysis vintage, and educational level.

Methods

Research Design

This study used an observational, cross-sectional design with an analytic purpose. Depressive symptoms and fluid and dietary adherence were measured once during a haemodialysis treatment. Demographic and clinical data were obtained from the review of medical records.

Participants and Settings

A convenience sample of 100 patients receiving haemodialysis at seven haemodialysis centres in Kentucky participated in this study. Patients were screened for eligibility by a medical record review. An invitation letter that explained the study details was used to recruit eligible patients. Interested patients met with the principle investigator who clearly explained the study, answered questions and obtained signed informed consent.

Inclusion criteria

Older than 21 years of age,

Able to read and write English,

Free of major psychiatric disorders or cerebrovascular disease that affected cognitive ability as documented in the medical records,

Receiving haemodialysis for at least 3 months.

Exclusion criteria

Presence of a coexisting terminal illness,

Prescribed antidepressant medication at time of recruitment,

History of missing more than one haemodialysis session in the previous two weeks or shortening a dialysis session by more than 10 minutes during the previous two weeks in the absence of a medically-related reason,

Severe metabolic acidosis with serum bicarbonate level of ≤ 12 mEq/L within the previous 2 weeks, and

Mean urea reduction ratio (URR) less than 65%.

These latter exclusion criteria were considered appropriate in order to eliminate the potential effect of under-dialysis and uraemia on depressive symptoms. A low URR may increase the indicators of dietary non-adherence measured by biological variables, such as serum potassium, and phosphorus among patients with ESRD receiving haemodialysis (Szczech et al., 2003).

Measurement of Variables

Depressive Symptoms

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)

The BDI-II contains 21 items that measure cognitive-affective symptoms and attitudes, impaired performance, and somatic symptoms associated with depressive symptoms (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). The items are rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3 with 0 indicating no symptoms and 3 indicating severe symptoms. The instrument takes 5 to 10 minutes to complete. Scores are calculated by summing the responses for the 21 items and the total possible score range is 0 to 63. Higher scores indicate a greater degree of depressive symptoms. Severity of depressive symptoms are categorised as minimal (0-13), mild (14-19), moderate (20-28) and severe (29 to 63) (Beck et al., 1996). For the purposes of this study, a BDI-II score of more than 13 indicated the presence of depressive symptoms (Beck et al., 1996). The BDI is considered by many investigators to be a well validated gold standard measure of depressive symptoms and for screening for clinical depression (Kimmel & Peterson, 2005).

This instrument offered us the ability to compare our results with established norms and with other populations of individuals with chronic diseases including ESRD (Chilcot, Wellsted & Farrington, 2008).

The Brief Symptom Inventory-Depression subscale

The Brief Symptom Inventory-depression subscale (BSI) measures the psychological symptoms, but not the physical manifestations of depressive symptoms. This may be an advantage over the BDI-II in patients with chronic medical illnesses (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). Depressive symptoms in the BSI depression subscale are assessed by 7 items rated on a five-point Likert scale regarding severity of symptoms experienced over the prior 7 days. Item responses range from 0, indicating not distressed by depressive symptoms, to 4, indicating extremely distressed by depressive symptoms. Scores are determined by adding the responses for the 7 items and dividing the total score by seven, the number of items in the subscale. Higher scores indicate a greater degree of depressive symptoms. A mean score of 1.80 has been reported for psychiatric outpatients, 1.77 for psychiatric inpatients, and 0.28 for a healthy population (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983). Based on these values, severity of depressive symptoms was categorised as no depressive symptoms (<0.28), mild to moderate (0.29 to 1.77), and severe (> 1.78). For this study, a score above 0.28 was used to indicate the presence of depressive symptoms.

Dietary Adherence

Subjective Fluid and Diet Adherence

Subjective fluid and diet adherence was measured by the Dialysis Diet and Fluid Nonadherence Questionnaire (DDFQ), a self report instrument composed of four items; two items assess fluid adherence and two assess diet adherence (Vlaminck et al. 2001). This scale evaluates perceived severity and estimated frequency of non-adherence to fluid and diet prescription. The degree of non-adherence is measured using a 5-point Likert scale (0 indicates no deviation up to 4 which indicates very severe deviation). The frequency of non-adherence to fluid and diet prescription is assessed by the individual patient estimating the number of days of non-adherence to diet or fluid restrictions in the prior two week period (Vlaminck et al. 2001). For analysis purposes, patients were categorised as adherent or non-adherent to fluid and diet prescriptions as follows. Perceived fluid non-adherence was a composite score of the perceived frequency and the perceived severity of fluid non-adherence (frequency × severity); perceived dietary non-adherence was a composite score of the perceived frequency and the perceived severity of dietary non-adherence (frequency × severity). Both the composite perceived fluid and diet non-adherence scores ranged from 0 (adherent) to 56 (severe non-adherence). Criterion validity of the DDFQ was previously evaluated by comparing it with the most common measures of fluid and dietary adherence (interdialytic weight gain, serum potassium, phosphate, and BUN). These objective measures correlated positively with self-reported dietary non-adherence measured by DDFQ (Kara et al., 2007; Vlaminck et al., 2001).

Objective Fluid and Dietary Adherence

Patients with an average interdialytic weight gain over the previous three months above 5% were defined as non-adherent to fluid prescription (Kobrin et al. 1991; Leggat et al., 1998). Interdialytic weight gain is the net increase in body weight from previous post-dialysis weight. In this population, post-dialysis weight is a surrogate for dry weight, which is the lowest weight a patient can tolerate without having signs and symptoms of hypovolaemia and hypotension. Objective dietary non-adherence was defined as presence of at least one of the following: serum potassium >5.5 mg/dl, serum phosphorus level >5.5 mg/dl or serum BUN >100 mg/dl. Pre-dialysis serum potassium, phosphorus and BUN levels were obtained from the medical records for the previous 3 months and the average of each was calculated for use in this study.

Perceived Social Support

Perceived social support was shown to be a significant predictor of objectively and subjectively measured dietary adherence in previous studies (Pang et al., 2001; Kara, et al. 2007). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) was used to assess perceptions of social support adequacy from the following three sources: family, friends and significant others such as health care team members (Zimet et al 1990). This is 12-item scale and each item is measured using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). The score for each subscale ranges from 4 to 28 and total scores range from 7 to 84. Higher scores indicate higher perceived social support (Zimet et al.,1990). The reliability, validity and factor structure of the MSPSS have been demonstrated across different populations including adolescents (Canty-Mitchell & Zimet, 2000), university students (Dahlem, Zimet, & Walker, 1991), pregnant women, and paediatric in-patients (Zimet et al., 1990). Higher social support scores were found to be associated with a significant 7% and 24% improvement in fluid and diet adherence respectively in patients with ESRD (OR = 0.93, 0.76, p = 0.003, 0.001 respectively) (Kara et al., 2007).

Demographic and Clinical variables

Demographic variables collected included age, gender, ethnicity, education level and marital status. Haemodialysis prescription and dialysis vintage (years receiving dialysis) were collected to fully characterise the sample. Renal residual function (RRF) was assessed by a 24-hour urine collection. The most recent RRF was obtained from the medical records, as each patient had a 24-hour urine measured every 6 months. Patients were classified as being without RRF (urine output ≤ 200 ml/day) and with RRF (urine output >200 ml/day) (Bragg-Gresham et al., 2007). Co-morbidity was assessed by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which summarises the number and severity of co-morbid conditions that may influence clinical outcomes such as mortality and health care costs. The total score for this instrument is equal to the sum of scores of the assigned weights for the co-morbid diseases. Higher scores indicate a greater co-morbidity burden. This method of classifying co-morbidity provides a simple, readily applicable and valid method of estimating risk of death from co-morbid disease (Charlson, et al. 1987; Di Iorio et al. (2004).

Procedure

The University of Kentucky Medical Institutional Review Board and the haemodialysis centres approved this study. Patients were screened for eligibility by the primary investigator and those who met study inclusion criteria were recruited using a standardised script. The study was explained clearly and completely and written informed consent was obtained from the patients. Demographic and clinical data were obtained by interview and medical record review after enrolment. Patients then completed four instruments in the following order:

the Dialysis Diet and Fluid Questionnaire (DDFQ),

the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II),

the Brief Symptom Inventory-Depression Subscale (BSI),

the Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS).

The primary investigator assisted when required by reading the questions to the patient and recording their responses. Data were collected within the first 90 minutes of a haemodialysis session. The primary health care provider was informed immediately by the primary investigator when patients reported suicidal ideation and patients were notified of this action. Data were entered into a data spreadsheet, inspected, cleaned and verified prior to analysis. Data were de-identified and confidentiality was further maintained by keeping all data in a locked cabinet in a secure area in the College of Nursing at the University of Kentucky.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterise the sample. The proportion of patients with depressive symptoms was calculated using both the BSI and the BDI-II scores and Chi square analysis determined whether there were significant differences in these proportions. The proportion of patients who were non-adherent to fluid and dietary prescription was also calculated using both the DDFQ and objective indicators. Logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the ability of depressive symptoms to predict diet and fluid non-adherence. In the first block, age, co-morbidities, dialysis vintage, residual renal function, social support and educational level were entered into the regression, as these are known to influence adherence. In the second block, either the BDI-II or the BSI scores were entered in two different models. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 15.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). An a priori alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

Patient Characteristics

More than half of participants (n = 100) were African American (55%) and female (56%). The mean age was 62 ± 15 years and patients had received haemodialysis for an average of 4 years (Table 1). The primary aetiology of ESRD was diabetes mellitus. A majority of patients (92%) were dialysed three times a week with a mean dialysis time of 222 (± 31) minutes. Patients had a high co-morbidity burden; the most common co-morbid conditions were diabetes mellitus (58%), heart failure (19%) and peripheral vascular disease (9%). Approximately one third of patients (34%) had residual renal function (UOP >200ml/24hrs).

Table1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients (n=100)

| Patient Characteristics | M ± SD | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.6 ± 14.9 | |

| Male | 44 (44%) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 30 (30%) | |

| Married | 36 (36%) | |

| Divorced/Separated | 13 (13%) | |

| Widowed | 21 (21%) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 43 (43%) | |

| African-American | 55 (55%) | |

| Employment | ||

| Full-time/part-time | 10 (10%) | |

| Unemployed | 49 (49%) | |

| Retired or disabled | 41 (41%) | |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 25 (25%) | |

| High school graduate | 40 (40%) | |

| College/University | 35 (35%) | |

| Aetiology of ESRD | ||

| Hypertension | 25 (25%) | |

| Diabetes | 44 (44%) | |

| Unknown aetiology | 10 (10%) | |

| Other | 21 (21%) | |

| Residual renal function | ||

| UOP < 200ml/24hrs | 66 (66%) | |

| UOP>200ml/24hrs | 34 (34%) | |

| Total co-morbidity score | 4.5 ± 1.9 | |

| Years of haemodialysis (years) | 4.4 ± 3.8 | |

| Serum potassium mEq/dl | 4.8 ± 0.5 | |

| Serum phosphorus mg/dl | 5.7 ± 1.4 | |

| Serum BUN mg/dl | 54 ± 16 | |

| Interdialytic weight gain (kg) | 2.7 ± 1.4 | |

| BDI Depression score | 13 ± 10.5 | |

| BSI Depression Score | 0.63 ± 0.66 | |

| Perceived social support | 72 ± 17 | |

Values are reported as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD), frequency (%).

ESRD: End-stage renal disease,

UOP: urine output,

BUN: blood urea nitrogen, BDI:

Beck Depression Inventory,

BSI: Brief Symptom Inventory.

mEq/dl: milli-equivalent/decilitre, mg/dl: milligram/ decilitre, kg: kilogram

Depressive Symptoms

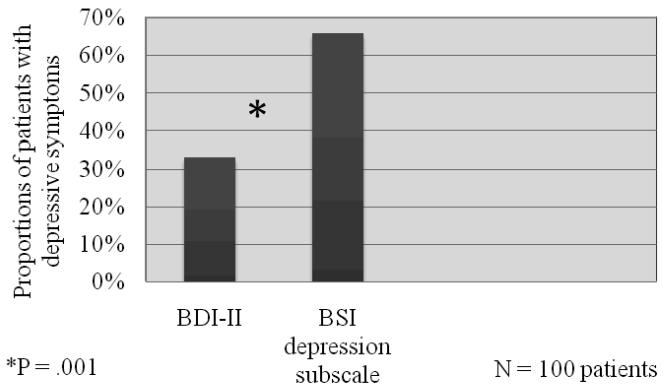

One third of participants (n = 33) exhibited depressive symptoms using the cut point BDI-II score above 13 and two thirds (n = 66) using the cut point BSI score above 0.28. When the proportions of patients with depressive symptoms using the two measures was compared, the BSI classified a significantly greater proportion of patients as having depressive symptoms compared with the BDI-II (X2 = 15.3, p = 0.0001) ( Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proportion of patients with depressive symptoms determined by the BDI-II and the BSI depression subscale.

Chi square used to test differences in proportions of patients with depressive symptoms using the two instruments

BDI –II = Beck Depression Inventory, BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory

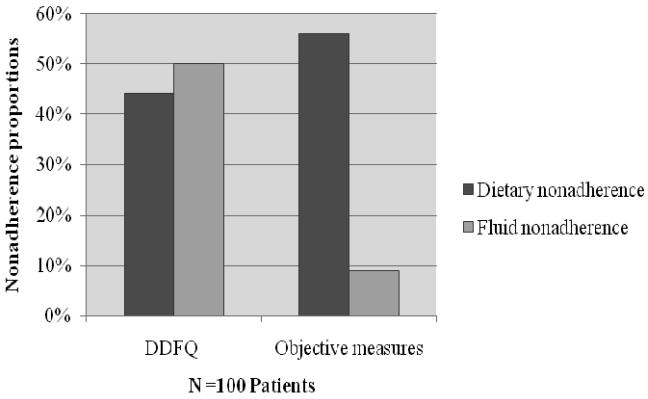

Fluid and Dietary Adherence

Half of patients (50%) reported non-adherence to fluid restriction using the self-report DDFQ. However, only 9% were non-adherent to fluid prescription using the mean interdialytic weight gain. Nearly half (44%) of patients perceived themselves to be non-adherent to dietary restrictions as measured by the self-report DDFQ. Using serum potassium, phosphorus, and BUN as indicators of dietary adherence, 56% of the patients were non-adherent to dietary restrictions. Specifically, the most common abnormality was an elevation of phosphorus (52% of patients); 10% of patients had elevation of serum potassium and 1% had increased BUN

Depressive Symptoms and Diet and Fluid Adherence

In the logistic regression models, age was the only clinical or demographic predictor of dietary non-adherence as defined by objective measures of adherence (OR=.95, p = 0.002). For every one year increase in age the likelihood of dietary adherence increased by 5%. Neither education level, residual renal function, number of co-morbidities, years of dialysis, nor perceived social support was a statistically significant predictor of fluid or dietary non-adherence. Depressive symptoms were also an independent predictor of self-reported fluid (BDI-II-OR = 1.1, p = 0.01; BSI-OR = 2.6. P = 0.02) and dietary non-adherence (BDI-II-OR = 1.1, p = 0.03; BSI- OR = 2.3, p = 0.03). Every one unit increase in the BDI-II score was associated with a 10% increased risk for self reported fluid and dietary non-adherence and every one unit increase in the BSI score was associated with more than double the risk for fluid and dietary non-adherence (Tables 2& 3). Depressive symptoms were not predictive of dietary non-adherence as indicated by objective measures; however, every one unit increase in BDI-II score was associated with a 10% increased risk of being non-adherent to fluid prescription using interdialytic weight gain as the indicator.

Table 2.

Summary of logistic regression analyses to predict self-report and objective fluid and dietary non-adherence using the BDI-II

| Self-report fluid non-adherence |

Self-report dietary non-adherence |

Objective fluid non-adherence |

Objective dietary non-adherence |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | OR (95% CI) | B | OR (95% CI) | B | OR (95% CI) | B | OR (95% CI) |

|

| Age | −.01 | .99 (.96-1.02) | .004 | 1.0 (.97-1.03) | −.01 | .99 (.94-1.05) | −.06 | *.94 (.94-.98) |

| Haemodialysis years |

.03 | 1.0 (.92-1.2) | .035 | 1.0 (.92-1.20) | −.01 | .99 (.80-1.23) | −.06 | .94 (.84- 1.05) |

| Total comorbidity score |

−.04 | .95 (.73-1.25) | .003 | 1.0 (.76-1.31) | .06 | 1.05 (.69- 1.61) |

.14 | 1.15 (.89- 1.50) |

| Residual renal function |

−.66 | .52 (.17-1.49) | .672 | 1.95 (.64-5.94) | −.16 | .85 (.16-4.66) | −.05 | 1.05 (.36- 3.04) |

| Perceived social support |

.01 | 1.0 (.98-1.03) | −.017 | .98 (.95-1.0) | 0 | .99 (.95-1.04) | −.01 | .88 (.58-1.31) |

| Educational level |

−.21 | .81 (.54-1.22) | −.235 | .79 (.52-1.20) | −.29 | .74 (.31-1.77) | −.13 | 1.67 (.59-4.73 |

| BDI-II score | .07 |

*1.10 (1.02-

1.13) |

.07 |

*1.10 (1.01-

1.13) |

.07 | *1.07 (1-1.14) | .51 | 1.67 (.59- 4.73) |

OR= odds ratio, CI= confidence interval, B=coefficient for the constant, p= p value, *p < 0.05, BDI-II= Beck Depression Inventory

Table 3.

Summary of logistic regression analyses to predict self-report and objective fluid and dietary non-adherence using the BSI OR=odds ratio, CI=confidence interval, B= coefficient for the constant p= p value, *p < 0.05, BDI-

| Self-report fluid non-adherence |

Self-report dietary non-adherence |

Objective fluid non-adherence |

Objective dietary non-adherence |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | OR (95% CI) | B | OR (95% CI) | B | OR (95% CI) | B | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age | −.004 | .99 (.96-1.02) | .008 | 1.0 (.97-1.04) | .001 | 1.0 (.94-1.05) | −.053 | *.95 (.92-.98) |

| Haemodialysis years |

.032 | 1.0 (.92-1.2) | .039 | 1.0 (.93-1.2) | .004 | 1.0 (.82-1.23) | −.061 | .94 (.84-1.05) |

| Total co- morbidity score |

−.031 | .97 (.74-1.27) | .013 | 1.0 (.77-1.33) | .112 | 1.11 (.74- 1.68) |

.16 | 1.20 (.90- 1.52) |

| Residual renal function |

−.59 | .55 (.19-1.58) | .71 | 2.0 (.68-6.20) | −.12 | 88 (.17-4.62) | .145 | 1.16 (.39- 3.37) |

| Perceived social support |

.01 | 1.0 (.98-1.03) | −.02 | .98 (.95-1.0) | −.006 | .99 (.95-1.03) | −.012 | .98 (.95-1.01) |

| Educational level |

−.26 | .76 (.52-1.15) | −0.30 | .74 (.49-1.11) | −.49 | .60 (.26-1.39) | −.24 | .78 (.52-1.17) |

| BSI score | .94 |

*2.6 (1.16-

5.7) |

.84 |

*2.30 (1.07-

4.95) |

.51 | 1.66 (.64- 4.33) |

−.37 | .68 (.25-1.86) |

II= Beck Depression Inventory

Discussion

In this group of patients with ESRD receiving haemodialysis, depressive symptoms and dietary and fluid non-adherence were common. There were significant differences in the proportion of the sample deemed to have depressive symptoms using two common self report instruments. The proportions were not statistically different between those who self-reported fluid and dietary non-adherence and those determined to be non-adherent based on biological markers. Depressive symptoms independently predicted self-reported fluid and dietary non-adherence and fluid non-adherence indicated by interdialytic weight gain after controlling for age, co-morbidities, haemodialysis years, residual renal function, perceived social support and educational level. Of these controlled variables, only age was a significant predictor of adherence.

In this study, the proportion of patients with depressive symptoms detected by the BDI-II were similar to those reported by others using clinical interviews (Craven, Rodin, & Littlefield, 1988; Lopes et al., 2002; Taskapan et al., 2005). Whereas, the proportion of patients with depressive symptoms detected by the BSI was consistent with previously reported studies using self-report instruments (30 to 90%) (Dogan, et al. 2005; Koo et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2004; Pang et al., 2001). Thus demonstrating that these instruments are not interchangeable in this population of patients. There are several explanations that can be proposed for the significant difference in the proportion of depressive symptoms detected by the BDI-II and the BSI.

First, the BDI-II cut point used for this study was based on patients with major depression disorders (Beck et al., 1996). Because of this, the BDI-II may have only detected patients with more severe depressive symptoms. Previous research studies used the BDI to screen for the presence of major depression disorders, rather than depressive symptoms of lesser severity, and produced a similar prevalence to that found in our study using the BDI-II (Craven et al., 1988; Kimmel et al., 1998; Taskapan et al., 2005). The BSI cut point of ≥0.28 was based on absence of depressive symptoms in a normal, healthy population (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983), which may make this cut point too low to be used for patients with ESRD and other chronic disorders. Thus, the chosen cut points could have led to the difference in the proportion of patients determined to have depressive symptoms.

Second, the severity of symptoms associated with ESRD may have affected the responses to these instruments. The BDI-II includes somatic symptoms when compared to the BSI, which has no items related to somatic symptoms. The present study included well dialysed patients who did not have severe symptoms related to uraemia and the presence of co-morbidities was controlled in our analyses. Thus, physical symptoms related to ESRD or co-morbidities were not factors in our results. Prior studies enrolled a more diverse group of patients who may have varied much more in their symptom experience and produced different results (Pang et al., 2001; Taskapan et al., 2005).

In this study, only 9% of the patients were non-adherent to fluid restriction as indicated by their interdialytic weight gain, which was lower than their self-reported fluid non-adherence. This is also lower than what has been previously reported. In prior studies, interdialytic weight gain was defined in different ways (Bame, et al. 1993; Saran et al., 2003; Vlaminck et al., 2001). One study used the most recent value of interdialytic weight gain upon enrolment (Saran et al., 2003); others used the mean of a set of interdialytic weight gain data collected prospectively or retrospectively for a couple of weeks (Sharp, et al. 2005; Zrinyi et al., 2003). We used the mean interdialytic weight gain for a 3 month period to provide an indication of longer term fluid adherence. Clearly, patients in our study perceived greater fluid non-adherence than that demonstrated by interdialytic weight gain. This may indicate the lack of a clear understanding of their fluid prescription or that the patients may have been educated to gain much less weight than what we used as a cut point for defining non-adherence to fluid intake.

Other investigators found rates of dietary non-adherence similar to our study using the same objective serum measures (Saran et al., 2003; Unruh, et al. 2005). In our study, half of the participants were non-adherent to phosphorus restrictions. Phosphorus was also the most common indicator of dietary non-adherence reported by other investigators (Durose et al., 2004; Vlaminck et al., 2001). This high prevalence of non-adherence may be due in part to a lack of knowledge about dietary phosphorus. The American diet provides approximately 1,500 mg of phosphorus daily, primarily from milk, meat, poultry, fish, cereal, and eggs; whereas, the recommended dietary allowance is 700 mg/day for patients with ESRD (Ford, et al. 2004). Lack of knowledge about foods that contain phosphorus and culture-related norms likely made adherence to this restriction difficult.

The prevalence of elevated potassium and BUN was low (10% and 1% respectively), also similar to prior studies (Bame et al., 1993; Saran et al., 2003). Patients may have been more likely to adhere to potassium restriction because hyperkalaemia is associated with life threatening cardiovascular complications such as fatal dysrhythmias. A more likely explanation is that potassium intake in the American diet has been demonstrated to be lower than recommended amounts; thus, dietary potassium restriction is easier to achieve (McGill et al., 2008). Serum BUN concentration was elevated in one patient only in our study. The level of BUN is also influenced by factors unrelated to dietary adherence such as dialysis associated loss of amino acid, RRF and dialysis dose (Unruh et al., 2005). ESRD patients typically lose 12 gram of amino acids and the required 200 kilocalories of energy during each dialysis treatment (Ikizler et al., 1996; Navarro et al., 2000). In addition, malnutrition is highly prevalent among haemodialysis patients because of associated loss of appetite (Kalanter-Zadeh, et al. 2001), which may cause lower levels of BUN. All of these factors rather than adherence to dietary protein restrictions could be responsible for our findings.

To our knowledge, there are no studies that have examined the relationship between depressive symptoms and self-reported fluid and dietary non-adherence in ESRD patients. In our study, regardless of the measure used, the presence of depressive symptoms predicted self-reported non-adherence to diet and fluid prescription. The variance in objectively measured fluid non-adherence based on the interdialytic weight gain in this study was explained only by the BDI-II. Reports of the association between depressive symptoms and dietary adherence using biological markers are inconsistent (Akman, et al. 2007; Kimmel et al., 1995; Pang et al., 2001; Sensky, et al. 1996; Taskapan et al., 2005). One study used a single objective measure of fluid adherence (Pang et al., 2001) and other researchers primarily used multiple biological markers to evaluate fluid and diet adherence and considered these biological markers as the gold standard measures (Sensky et al., 1996; Taskapan et al., 2005). This study used self-reported, as well as objective measures, to assess the broader picture of the relationship between depressive symptoms and dietary adherence.

In prior studies, patients with ESRD commonly overestimated their dietary adherence (Mai, et al. 1999), which is different from our findings. In the present study, depressive symptoms detected by the BDI-II and the BSI depression subscale were significantly associated with self-reported fluid and dietary non-adherence. The patient's ability to perceive his/her adherence to dietary restrictions was skewed compared to the objective indicators of dietary adherence. Several features of depressive symptoms may influence the patient perception of adherence to dietary restrictions. These include negative thoughts about self, not seeking and using knowledge appropriately, decreased cognitive function, and reduced concentration abilities.

Limitations of this study included the use of a cross-sectional design, which does not permit determination of a causal relationship between depressive symptoms and fluid and dietary adherence. The use of a convenience sample may have led to a selection bias if patients with severe depressive symptoms avoided participating in the study. However, patients with the full range of depressive symptoms were included based on the BDI-II and the BSI scores, which should decrease the effect of this limitation. The self-reported fluid and dietary non-adherence may also cause a response bias as patients respond as they think the investigator desires. In addition, the biological markers used could be affected by residual renal function. However, no relationship was found between residual renal function and the biological indicators of adherence and this variable was controlled in the regression analyses.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

A large proportion of our patients had at least mild depressive symptoms. This suggests that depressive symptoms may be under-recognised and undertreated in patients with ESRD receiving haemodialysis. Regular screening for depressive symptoms would provide an opportunity for management using pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. There is also need for regular evaluation of fluid and dietary prescription adherence using multiple measures. Biological indicators provide some insight into adherence, but are influenced by a number of other factors. A self-report measure like DDFQ could provide insight into perceived adherence to fluid and dietary prescription and an opportunity for intervention.

Because depressive symptoms predicted dietary non-adherence, interventions focused on depressive symptoms might improve dietary adherence. Patients with ESRD are often overwhelmed by their rigorous medication regimen; the addition of antidepressant drugs could produce more stress and increase the likelihood of drug-drug interaction. Thus, cognitive-behavioural therapy might be a better option by building healthy relationships between feelings, thoughts and behaviours (Sharp et al., 2005). In addition, an educational intervention might provide knowledge about the importance and the health consequences of dietary adherence. For example, an educational intervention may improve the ability to measure the prescribed quantity of fluid and evaluate the nutrients in chosen foods and match it with the prescribed amounts.

Conclusion

Depressive symptoms and dietary non-adherence were highly prevalent in our patients with ESRD receiving haemodialysis. Depressive symptoms were an independent predictor of perceived fluid and dietary non-adherence. Studies are needed to increase our understanding of the relationship between depressive symptoms and both perceived and objectively determined dietary adherence. These studies should focus on the most appropriate measures of depressive symptoms and dietary non-adherence and testing interventions to reduce non-adherence to fluid and dietary restrictions that address depressive symptoms in patients with ESRD.

Figure 2. Proportion of patients with dietary non-adherence measured by self-report (DDFQ) and objective measures.

Chi square used to test differences in proportions of patients identified as non-adherent using subjective and objective measures

DDFQ = Dialysis Diet and Fluid Questionnaire

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a Centre grant to the University of Kentucky College of Nursing from NIH, NINR, 1P20NR010679. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health.

This work was supported by Delta Psi Chapter of Sigma Theta Tau Award. We thank the Fresenius and DCI Inc outpatient haemodialysis unit patients, medical directors, administrators, nurses, and clinicians in Lexington, Frankfort and Richmond, Kentucky for their assistance in the conduct of this study.

Footnotes

Amani Khalil, is an Assistant Professor, teaching Undergraduate students at the college of Nursing, University of Jordan. Her PhD provided an in-depth exploration of the inter-relationships between the psycho-bio-social aspects of patients with end-stage renal disease receiving haemodialysis.

References

- Akman B, Uyar M, Afsar B, et al. Adherence, depression and quality of life in patients on a renal transplantation waiting list. Transplant International. 2007;5(48):1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bame SI, Petersen N, Wray NP. Variation in hemodialysis patient compliance according to demographic characteristics. Social Science & Medicine. 1993;37(8):1035–1043. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90438-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck G, Steer R, Brown G. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bragg-Gresham J, Fissell RB, Mason NA, et al. Diuretic use, residual renal function, and mortality among hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Pattern Study (DOPPS) American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2007;49(3):426–431. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcot J, Wellsted D, Farrington K. Screening for depression while patients dialyse: An evaluation. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2008;23:2653–2659. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, Ehlers S. Psychological factors in end-stage renal disease: An emerging context for behavioural medicine research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(3):712–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven JL, Rodin GM, Littlefield C. The Beck Depression Inventory as a screening device for major depression in renal dialysis patients. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1988;18(4):365–374. doi: 10.2190/m1tx-v1ej-e43l-rklf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlem NW, Zimet GD, Walker RR. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support: a confirmation study. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1991;47(6):756–761. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199111)47:6<756::aid-jclp2270470605>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychological Medicine. 1983;13(3):595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Iorio B, Cillo N, Cirillo M, et al. Charlson Comorbidity Index is a predictor of outcomes in incident hemodialysis patients and correlates with phase angle and hospitalization. The International Journal of Artificial Organs. 2004;27(4):330–336. doi: 10.1177/039139880402700409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(14):2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan E, Eryonucu B, Sayarlioglu H, et al. Relation between depression, some laboratory parameters, and quality of life in hemodialysis patients. Renal Failure. 2005;27:695–699. doi: 10.1080/08860220500242728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durose C, Holdeworth M, Watson V, et al. Knowledge of dietary restrictions and the medical consequences of noncompliance by patients on hemodialysis are not predictive of dietary compliance. Journal of The Dietetic Association. 2004;104:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein F, Watnick S, Finkelstein S, et al. The treatment of depression in patients maintained on dialysis. Journal of psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:957–960. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford J, Pope J, Hunt A, et al. The effect of diet education on the laboratory values and knowledge of hemodialysis patients with hyperphosphatemia. Journal of Renal Nutrition. 2004;14(1):36–44. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallan SI, Coresh J, Astor BC, et al. International comparison of the relationship of chronic kidney disease prevalence and ESRD risk. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2006;17:2275–2284. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikizler TA, Wingard RL, Sun M, et al. Increased energy expenditure in hemodialysis patients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1996;7(12):2646–2653. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V7122646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalanter-Zadeh K, Kopple J, Block G, et al. A malnutrition-inflammation score is correlated with morbidity and mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2001;38(6):1251–1263. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.29222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara B, Caglar K, Kilic S. Non-adherence with diet and fluid restrictions and perceived social support in patients receiving hemodialysis. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2007;39(3):243–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel P, Karen P, Samuel W, et al. Multiple measurements of depression predict mortality in a longitudinal study of chronic hemodialysis outpatients. Kidney International. 1998;57:2093–2098. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel P, Peterson R. Depression in end-stage renal disease patients treated with hemodialysis: Tool, correlates, outcomes, and needs. Seminars in Dialysis. 2005;18(2):91–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.18209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel P, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, et al. Behavioural compliance with dialysis prescription in hemodialysis patients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1995;5(10):1826–1834. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V5101826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobrin SM, Kimmel PL, Simmens SJ, et al. Behavioural and biochemical indices of compliance in hemodialysis patients. ASAIO Transactions. 1991;37(3):M378–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo J, Yoon J, Kim S, et al. Association of depression with malnutrition in chronic hemodialysis patients. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2003;41(5):1037–1042. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugler C, Valminck H, Haverich A, et al. Nonadherence with diet and fluid restrictions among adults having hemodialysis. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2005;37(1):25–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutner N, Zhang R, McClellan W, et al. Psychosocial predictors of non-compliance in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2002;17:93–99. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Lee H, Kim D, et al. The effects of antidepressant treatment on serum cytokines and nutritional status in hemodialysis patients. Journal of Korean Medical Sciences. 2004;19:384–389. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.3.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggat J, Orzol SM, Hulbert-Shearon TE, et al. Noncompliance in hemodialysis: predictors and survival analysis. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 1998;32(1):139–145. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9669435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes A, Bragg J, Young E, et al. Depression as a predictors of mortality and hospitalization among hemodialysis patients in the United States and Europe. Kidney International. 2002;62:199–207. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai FM, Busby K, Bell RC. Clinical rating of compliance in chronic hemodialysis patients. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;44(5):478–482. doi: 10.1177/070674379904400508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill CR, Fulgoni VL, 3rd, DiRienzo D, et al. Contribution of dairy products to dietary potassium intake in the United States population. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2008;27(1):44–50. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro JF, Mora C, Leon C, et al. Amino acid losses during hemodialysis with polyacrylonitrile membranes: effect of intradialytic amino acid supplementation on plasma amino acid concentrations and nutritional variables in nondiabetic patients. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;71(3):765–773. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.3.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang S, Ip W, Chang A. Psychosocial correlate of fluid compliance among Chinese hemodialysis patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;35(5):691–698. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saran R, Bragg-Grasham L, Rayner H, et al. Nonadherence in hemodialysis: Associations with mortality, hospitalization, and practice patterns in the DOPPS. Kidney International. 2003;64:245–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sensky T, Leger C, Gilmour S. Psychosocial and cognitive factors associated with adherence to dietary and fluid restriction regimens by people on chronic hemodialysis. Psychotherapy Psychosomatics. 1996;65(1):36–42. doi: 10.1159/000289029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp J, Wild M, Andrew I, et al. A cognitive behavioural group approach to enhance adherence to hemodialysis fluid restriction: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2005;45(6):1046–1057. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soykan A, Boztas H, Kutlay S, et al. Depression and its 6-month course in untreated hemodialysis patients: A preliminary prospective follow-up study in Turkey. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;11(4):243–246. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1104_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczech L, Reddan D, Klassen P, et al. Interactions between dialysis-related volume exposures, nutritional surrogates and mortality among ESRD patients. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 2003;18:1585–1591. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taskapan H, Ates F, Kaya B, et al. Psychiatric disorders and large interdialytic weight gain in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Nephrology. 2005;10:15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2005.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unruh ML, Evans IV, Fink NE, et al. Skipped treatments, markers of nutritional nonadherence, and survival among incident hemodialysis patients. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2005;46(6):1107–1116. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Renal Data System. National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Diseases in the United States. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.usrds.org/2009/pdf/V2_05-09.PDF.

- Vazquez I, Valderrabano F, Fort J, et al. Psychosocial factors and health-related quality of life in hemodailysis patients. Quality Life Research. 2005;14:179–190. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-3919-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaminck H, Maes B, Jacobs A, et al. The dialysis diet and fluid non-adherence questionnaire: Validity testing of a self-report instrument for clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2001;10:707–715. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2001.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Powell S, Farley G, Werkman S, et al. Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1990;55(3-4):610–617. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zrinyi M, Juhasz M, Balla J, et al. Dietary self-efficacy: determinant of compliance behaviours and biochemical outcomes in haemodialysis patients. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 2003;18(9):1869–1873. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]