Abstract

The mechanism of HTLV-1 transformation of cells to Adult T cell leukemia (ATL) remains not fully understood. Currently, the viral Tax oncoprotein is known to be required to initiate transformation. Emerging evidence suggests that Tax is not needed to maintain the transformed ATL phenotype. Recent studies have shown that HTLV-1 transformed cells show deregulated expression of cellular microRNAs (miRNAs). Here we discuss the possibility that early ATL cells are Tax-oncogeneaddicted while late ATL cells are oncogenic microRNA (oncomiR) – addicted. The potential utility of interrupting oncomiR addiction as a cancer treatment is broached.

Keywords: HTLV, ATL, MicroRNAs, Leukemia, oncogene

HTLV-1 was the first human retrovirus to be isolated. It was identified in 1980 by Robert Gallo and co-workers [1]; that initial finding was followed closely by important contributions from Japanese virologists [2]. HTLV-1 is causative of Adult T cell leukemia [3,4], a treatment refractory T cell cancer found endemically in Japan [5] and elsewhere [6]. Studies on this virus over the past three decades have provided insight into oncogene- and oncogenic microRNA- (oncomiR) addiction in leukemic transformation.

HTLV-1 encodes a viral Tax oncoprotein [7-9] whose expression confers prosurvival and proproliferative properties to infected cells. Extant findings have shown that Tax is sufficient to transform human T cells [10,11]. Hence, the expression of Tax-alone in transgenic mice was found to be fully proficient for in vivo tumorigenesis [12-14]. Indeed, current data are consistent with the notion that Tax expression in infected humans greatly accelerates the in vivo cycling of T cells [15]. Intriguingly, when ATL patients are followed over time, a puzzling finding reveals that Tax expression in vivo is absent from approximately 60% of late leukemias [16]. Thus, unlike other virus-induced human malignancies such as the cervical cancers caused by human papilloma virus (HPV), in which the expression of the viral E6 and E7 oncoproteins are required for tumor maintenance [17], late ATL cells are apparently not addicted to the Tax oncoprotein. Why might ATL cells extinguish Tax expression? A possible reason is because this viral protein represents the major target for cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTL) in infected patients [18,19]. Accordingly, the loss of Tax expression in vivo would facilitate the escape of virus-infected cells from CTL surveillance; and this seemingly would benefit disease progression.

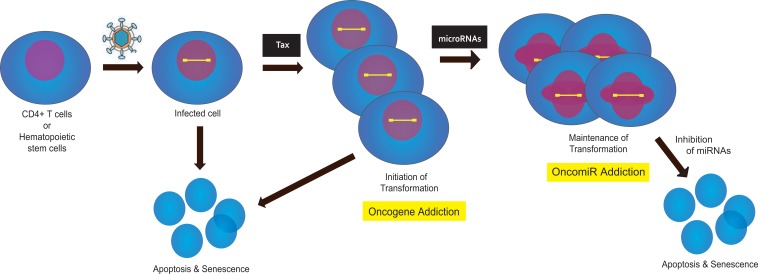

A currently accepted model for ATL genesis by HTLV-1 is that the viral Tax oncogene is used for the initiation, but not the maintenance, of leukemogenesis (Figure 1). In this regard, the HTLV-1 – ATL transformation mechanism appears not to subscribe to the oncogene addiction model of carcinogenesis [20]. What might then be some of the factor(s) needed for ATL cells to maintain their leukemic phenotype in the absence of Tax? One possible explanation rests with the observation that all ATL cells exhibit virus-mediated attenuation of the cell's spindle assembly checkpoint [21] and are thus highly aneuploid [9]. Potentially, this selected presentation of aneuploid chromosomes could be sufficient per se for maintaining the transformed ATL phenotype [22]. A second possibility is that transformed ATL cells have acquired altered expression of cellular microRNAs that are capable, in a Tax-independent fashion, of maintaining oncogenesis (e.g. oncomiRs [23] [24]).

Figure 1. Potential stages of oncogene-addiction and oncomiR-addiction in HTLV-1 transformation of ATL leukemic T cells.

Virus-infected cells either initiate transformation after Tax expression or enter apoptosis/senescence. At this stage the cells could be regarded as Tax-oncogene-addicted. Subsequently, the expression of Tax in ATL cells is extinguished, and maintenance of the transformed phenotype in the cells is postulated to emerge from altered miRNA expression (oncomiR-addiction). Inhibition of the activity of oncomiRs can send such cells in tissue culture into apoptosis/senescence. (The figure is modified from Jeang, KT, JFMA, 2010, in press).

Altered miRNA expression has indeed been linked to carcinogenesis. Early on, it was found that the loss of miR-15a and miR-16-1 correlated with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia [25]. Later, miRNA signatures for various cancers were described and linked to oncogenic transformation and found to be diagnostic of tumor types [23,26]. The deregulated expression of miRNAs in HTLV-1 transformed cells has also been reported in three independent publications [27-29]. In parsing the specific miRNA changes published in the three HTLV-1 studies, there appears to be very little over lap amongst most of the miRNA moieties [30]. Nonetheless, there was an intriguing consensus amongst the three findings. For example, in the study by Yeung et al., the authors reported that the tumor suppressor protein TP53INP1 in HTLV-1- infected/transformed cells was targeted for repression by the upregulated expression of miR-93 and miR-130b [27]. By comparison, in the subsequent study by Pichler et al., TP53INP1 was also reported to be targeted in HTLV-1 infected/transformed cells, but by the upregulated expression of miR-21, -24, -146a, and -155 [28]. Remarkably, separate from the in vitro HTLV-1 infected/transformed cells, Bellon et al. and Yeung et al. further investigated in vivo ATL leukemic cells from patients; and both noted upregulated miR-155 expression [27,29] which would be consistent with a silencing of TP53INP1 by miR-155 [31]. Thus, collectively, the three studies agree and converge on TP53INP1 as one of the important miRNA-regulated targets in ATL transformation by HTLV-1.

Based on the above data, one biological scenario is that late ATL cells may indeed be oncomiR-addicted while early ATL cells are Tax-oncogene-addicted (Figure 1). Recently, Watashi et al. have provided additional evidence that NIH 3T3 mouse cells can be transformed by singular over expression of either miR-93 or miR-130b [32]. They discovered two small molecule compounds that can be used to reduce the over expression of miR-93 or miR-130b, and they showed that the treatment of miR-93- or miR-130b transformed NIH 3T3 cells using such compounds reversed tumorigenesis [32]. These results support the interpretation that in certain settings oncomiR-addicted tumors exist, and that this addiction could represent a potential treatment target for such cancers.

One might reason that a logical extension is to treat cancers by reducing oncomiR expression as well as targeting oncogene expression. Reality may be more complicated than this simple logic. Some studies have shown that a generalized down regulation of miRNAs is frequently seen in human cancers [26,33]. While it is not fully understood how general miRNA down regulations could propitiate carcinogenesis, such observations do raise caution that small molecule inhibitors of oncomiR activity needs to be utilized judiciously and monitored carefully to ensure that they ameliorate rather than exacerbate cancers. Further investigations are needed to conclusively verify oncomiR inhibition as an important treatment option in cancers.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed here are the personal opinions of the author and do not reflect the views of his employer, the US National Institutes of Health. Work in KTJ's laboratory is supported by intramural funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The author thanks Daniel Schmidt and Lauren Lee for help with manuscript and figure preparations.

REFERENCE LIST

- 1.Poiesz BJ, Ruscetti FW, Gazdar AF, Bunn PA, Minna JD, Gallo RC. Detection and isolation of type C retrovirus particles from fresh and cultured lymphocytes of a patient with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:7415–7419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshida M, Miyoshi I, Hinuma Y. Isolation and characterization of retrovirus from cell lines of human adult T-cell leukemia and its implication in the disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:2031–2035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallo RC. The discovery of the first human retrovirus: HTLV-1 and HTLV-2. Retrovirology. 2005;2:17. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida M. Discovery of HTLV-1, the first human retrovirus, its unique regulatory mechanisms, and insights into pathogenesis. Oncogene. 2005;24:5931–5937. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takatsuki K. Discovery of adult T-cell leukemia. Retrovirology. 2005;2:16. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-2-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proietti FA, Carneiro-Proietti AB, Catalan-Soares BC, Murphy EL. Global epidemiology of HTLV-I infection and associated diseases. Oncogene. 2005;24:6058–6068. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grassmann R, Aboud M, Jeang KT. Molecular mechanisms of cellular transformation by HTLV-1 Tax. Oncogene. 2005;24:5976–5985. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higuchi M, Fujii M. Distinct functions of HTLV-1 Tax1 from HTLV-2 Tax2 contribute key roles to viral pathogenesis. Retrovirology. 2009;6:117. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-6-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuoka M, Jeang KT. Human T-cell leukaemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) infectivity and cellular transformation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:270–280. doi: 10.1038/nrc2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosin O, Koch C, Schmitt I, Semmes OJ, Jeang KT, Grassmann R. A human T-cell leukemia virus Tax variant incapable of activating NF-kappaB retains its immortalizing potential for primary T-lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6698–6703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robek MD, Ratner L. Immortalization of CD4(+) and CD8(+) T lymphocytes by human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 Tax mutants expressed in a functional molecular clone. J Virol. 1999;73:4856–4865. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4856-4865.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grossman WJ, Kimata JT, Wong FH, Zutter M, Ley TJ, Ratner L. Development of leukemia in mice transgenic for the tax gene of human T-cell leukemia virus type I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1057–1061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasegawa H, Sawa H, Lewis MJ, Orba Y, Sheehy N, Yamamoto Y, et al. Thymus-derived leukemia-lymphoma in mice transgenic for the Tax gene of human T-lymphotropic virus type I. Nat Med. 2006;12:466–472. doi: 10.1038/nm1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohsugi T, Kumasaka T, Okada S, Urano T. The Tax protein of HTLV-1 promotes oncogenesis in not only immature T cells but also mature T cells. Nat Med. 2007;13:527–528. doi: 10.1038/nm0507-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zane L, Sibon D, Jeannin L, Zandecki M, fau-Larue MH, Gessain A, et al. Tax gene expression and cell cycling but not cell death are selected during HTLV-1 infection in vivo. Retrovirology. 2010;7:17. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeda S, Maeda M, Morikawa S, Taniguchi Y, Yasunaga J, Nosaka K, et al. Genetic and epigenetic inactivation of tax gene in adult T-cell leukemia cells. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:559–567. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laughlin-Drubin ME, Munger K. Oncogenic activities of human papillomaviruses. Virus Res. 2009;143:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kannagi M, Harada S, Maruyama I, Inoko H, Igarashi H, Kuwashima G, et al. Predominant recognition of human T cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-I) pX gene products by human CD8+ cytotoxic T cells directed against HTLV-I-infected cells. Int Immunol. 1991;3:761–767. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.8.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobson S, Shida H, McFarlin DE, Fauci AS, Koenig S. Circulating CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for HTLV-I pX in patients with HTLV-I associated neurological disease. Nature. 1990;348:245–248. doi: 10.1038/348245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weinstein IB, Joe AK. Mechanisms of disease: Oncogene addiction--a rationale for molecular targeting in cancer therapy. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006;3:448–457. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin DY, Spencer F, Jeang KT. Human T cell leukemia virus type 1 oncoprotein Tax targets the human mitotic checkpoint protein MAD1. Cell. 1998;93:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chi YH, Jeang KT. Aneuploidy and cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:531–538. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:704–714. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scaria V, Jadhav V. microRNAs in viral oncogenesis. Retrovirology. 2007;4:82. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Bichi R, Zupo S, Noch E, et al. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, varez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeung ML, Yasunaga J, Bennasser Y, Dusetti N, Harris D, Ahmad N, et al. Roles for microRNAs, miR-93 and miR-130b, and tumor protein 53-induced nuclear protein 1 tumor suppressor in cell growth dysregulation by human T-cell lymphotrophic virus 1. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8976–8985. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pichler K, Schneider G, Grassmann R. MicroRNA miR-146a and further oncogenesis-related cellular microRNAs are dysregulated in HTLV-1-transformed T lymphocytes. Retrovirology. 2008;5:100. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-5-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bellon M, Lepelletier Y, Hermine O, Nicot C. Deregulation of microRNA involved in hematopoiesis and the immune response in HTLV-I adult T-cell leukemia. Blood. 2009;113:4914–4917. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-189845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruggero K, Corradin A, Zanovello P, Amadori A, Bronte V, Ciminale V, et al. Role of microRNAs in HTLV-1 infection and transformation. Mol Aspects Med. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gironella M, Seux M, Xie MJ, Cano C, Tomasini R, Gommeaux J, et al. Tumor protein 53-induced nuclear protein 1 expression is repressed by miR-155, and its restoration inhibits pancreatic tumor development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16170–16175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703942104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watashi K, Yeung ML, Starost MF, Hosmane RS, Jeang KT. Identification of Small Molecules That Suppress MicroRNA Function and Reverse Tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24707–24716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.062976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar MS, Pester RE, Chen CY, Lane K, Chin C, Lu J, et al. Dicer1 functions as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2700–2704. doi: 10.1101/gad.1848209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]