Abstract

In this prospective study, teenager mothers (mean age = 16; range = 12–18; 70% African American) were interviewed about their tobacco use during pregnancy. When their children were ten, mothers reported on their child’s behavior and the children completed a neuropsychological battery. We examined the association between prenatal cigarette smoke exposure (PCSE) and offspring neurobehavioral outcomes on data from the ten-year phase (n = 336). Multivariate regression analyses were conducted to test if PCSE predicted neurobehavioral outcomes, adjusting for demographic characteristics, maternal psychological characteristics, prenatal exposure to other substances, and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Independent effects of PCSE were found. Exposed offspring had more delinquent, aggressive and externalizing behaviors (CBCL). They were more active (Routh, EAS, SNAP) and impulsive (SNAP), and had more problems with peers (SNAP). On the Stroop test, deficits were observed in both baseline response processing measures and on the more complex interference task that requires both selective attention and response inhibition. The significant effects of PCSE on neurobehavioral outcomes were found for exposure to as few as 10 cigarettes per day. These results are consistent with results from an earlier assessment when the children were age 6, demonstrating that the effects of prenatal tobacco exposure can be identified early and are consistent through middle childhood.

Keywords: prenatal smoking, neurobehavioral, teenage mothers, children

1. Introduction

The rate of teenage pregnancy in the U.S. remains significantly higher than rates of teenage pregnancy in other developed countries [24], and it is estimated that one-third of all American girls will get pregnant by age 20. Smoking is common among pregnant adolescents, with an estimated 20–50% of pregnant adolescents smoking compared to 10–15% of all pregnant women [3]. Using the most conservative estimate, if 20% of the 435,427 girls aged 15–19 who gave birth last year [40], smoked while they were pregnant, at least 87,085 of American infants were exposed to gestational tobacco last year from these teenage pregnancies alone. The health of these and many other children may be compromised by prenatal cigarette smoke exposure (PCSE), which has been associated with negative outcomes at birth, during childhood, adolescence and adulthood [5,8,17,19,20,22,32,41,42,49,50,52,62,69,70].

Recent reviews of the literature provide significant support for concern about the neurobehavioral (NB) effects of PCSE on exposed offspring. Many of the more recent studies use prospective designs, biological measures of tobacco exposure, and multivariate statistical analyses designed to control for many possible confounds [12,18,55,60]. The effects of PCSE range from irritability and poor self-regulation during infancy [47,64,65] to behavior problems during childhood [14,34,53,57,70]. For example, preschoolers with PCSE in the Raine Study were significantly more likely to have externalizing and internalizing problems than preschoolers without PCSE, even after controlling for maternal age and SES, perinatal health status, breastfeeding, and symptoms of postnatal depression [57]. Additionally, longitudinal studies have demonstrated negative effects of PCSE on adolescent [22,44,52] and adult behavior [8,9].

It is important to include measures of other prenatal substance exposures and environmental factors when testing for teratological effects on behavior in longitudinal studies [29]. There are many factors that lead to neurobehavioral deficits and women who smoke during pregnancy are more likely to exhibit these risk factors including other maternal risk behaviors [2,10], poverty [48], and parental psychopathology [41]. In addition, women who smoke during pregnancy are more likely to expose their children to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) in the postpartum [21,27]. ETS has also been linked to behavior problems [30,31,71,73].

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the effect of PCSE on neurobehavioral (NB) outcomes during middle childhood in the offspring of teenage mothers. In a prospective study, we collected trimester-specific data on maternal substance use including tobacco, alcohol, marijuana and other illicit drugs during pregnancy and in the postpartum. We assessed NB outcomes in the offspring at age 10. We hypothesized that PCSE would predict an increased rate of child NB problems in the offspring of teenage mothers, and that this association would remain significant after controlling for covariates of maternal smoking such as other substance use and environmental factors. Additionally, we hypothesized a dose-response relationship between the amount of PCSE and scores on the NB measures, such that the offspring of adolescent mothers with more PCSE would have poorer scores on the measures of NB than would the offspring of adolescent mothers with less PCSE.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample Selection and Study Design

These data on teenage mothers and their offspring come from the Teen Mother Study, which is part of the Maternal Health Practices and Child Development (MHPCD) project, a consortium of studies on the long-term effects of prenatal substance use. The pregnant teenagers were recruited from a large inner-city teaching hospital from 1990–1994. The adolescents were seen once during a prenatal visit, at delivery with their newborn infants, and then during follow-up visits to our laboratory with their children 6 and 10 years after delivery. The 6- and 10-year follow-up visits took place between 1996–2000 and 2000–2004, respectively. Each phase of this study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the teaching hospital and the University. Participants were informed about confidentiality and assured that their information was protected by a Certificate of Confidentiality issued by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

The participants were recruited in the second trimester of their pregnancies, when they came into the clinic for their fourth or fifth prenatal visit. In a private room at the clinic, the pregnant adolescents were interviewed about their current and previous (during the first trimester and one year prior to becoming pregnant) tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and other drug use. The adolescents were seen again 24–36 hours after delivery, when they were interviewed about their substance use during the second and third trimesters of the pregnancy. At the 6-year and 10-year follow-up visits at our offices, the mothers provided information about their recent substance use (current and past year) as well as their demographic and psychological status. Medical histories were taken at this time for both mothers and children. NB measures were added to the protocol for the 10-year visit. Reports on maternal substance use, growth of the offspring, and 6-year outcomes have been provided in previous reports [19,20,23]. The present report focuses on the effects of PCSE on NB outcomes of the 336 10-year-old offspring.

2.2. Sample Description

All of the teenage mothers attending the prenatal clinic who were under the age of 19 were eligible for the present study. This included 448 pregnant girls aged 12–18 years. Of the 448 girls who were originally approached to participate in the study, 3 refused, for an initial refusal rate of 0.7%. Of the remaining 445 pregnant teenagers, 15 moved out of the area prior to delivery, and 1 refused the delivery interview. Additional losses included six twin births, five spontaneous abortions, two still-born infants, and three live-born premature infants who died. Thus, 413 live-born singletons and their teenage mothers were assessed at delivery.

A total of 330 women and their offspring were assessed at the 10-year follow-up phase: 24 mothers refused to participate, 39 were lost to follow-up, 10 had moved out of the state, 2 children were in foster care, 7 children had died, and 1 child was adopted. Prenatal substance exposure and SES did not differ significantly between the mothers and children seen at the 10-year follow-up and those who were not seen at 10 years.

The women, on average, were 16.3 years old (range=12–18) at study recruitment; 69% were African American, 31% were European American, and 99% of them were unmarried at delivery [19]. At the 10-year follow-up, the mothers’ average monthly income was US $1,788 (range = $0–$9,990) and their mean education was 12.6 years (range= 7–18). Most of the mothers (88%) had completed high school or received a General Equivalency Diploma (GED), and most of the women (76%) were not currently married. Most of the children (87%) were living with their biological mothers at the age 10-year follow-up; the remaining 13% of the children were with a custodian. If a child was not living with his or her mother, the current custodian was interviewed. Of the mothers who were living with their children, 13.4% were living with the child’s father, 29.1% lived with a husband or boyfriend who was not the child’s father, and 48.8% were living alone with their children.

2.3. Measures of Substance Use

The substance use measures used in this study were developed and extensively tested for studies of alcohol use during pregnancy in adult women. The questions were developed to reflect accurately both the pattern and level of use [25]. At all phases of testing, the participants were interviewed in a private setting by interviewers who were comfortable discussing alcohol and drug use, who were trained to use the instrument reliably, accurately identify the drugs used, and assess the amount of use. For substance use during pregnancy, calendar landmarks were used to indicate time periods that corresponded with conception and recognition of pregnancy. Assessment was done for each trimester of pregnancy. Dichotomous variables were created for each trimester to indicate “any/none” and “10+ cigarettes per day/none.” The current analyses focus on first and third trimester exposures.

At the 10-year phase, the young mothers were asked about their use of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana and other illicit drugs over the past year. Tobacco use was measured by the number of cigarettes smoked per day and brand of cigarette. Quantity and frequency of the usual, maximum, and minimum use of each alcoholic beverage were also assessed. The average daily number of drinks was calculated from these data. Because average daily number of drinks was positively skewed, log linear transformation was used to reduce the skewness. Marijuana use was assessed as the quantity and frequency of the usual, maximum, and minimum use. Marijuana, hashish, and sinsemilla use were transformed into average daily joints: a blunt of marijuana was converted to four joints, and a hashish cigarette or bowl was counted as three joints, based on the relative amount of delta-9-THC in each [35]. Only 1 pregnant teenager reported other illicit drug use.

2.4. Covariates

Many measures of the child’s environment were included in the analyses as potential covariates of neurobehavioral outcomes, based on the literature and previous findings in this cohort. These measures included maternal substance use during childhood, demographic characteristics (e.g., age, ethnicity, child gender, child custody, and single motherhood), socioeconomic status (SES), maternal stressful life events, and maternal social support. The Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment - Short Form (HOME-SF) [4] was used to measure the quality and quantity of support available to the child for cognitive, social, and emotional development.

We assessed current maternal substance use and included these measures in all multivariate analyses, to test for the independent contributions of PCSE, after controlling for environmental exposure to tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use. Children provided a urine sample as a biological measure of their passive exposure to tobacco smoke at age 10. The urine sample was collected from the children with the help of their parent or the study nurse during the break in the assessment protocol approximately 1½–2 hours from the time the child arrived at the study office. The samples were sent to an independent laboratory and analyzed using a Varian 3600 gas chromatograph that incorporated nitrogen selective detection. The level of detection for cotinine at this laboratory was 1 ng/ml. Cotinine values below the level of detection are reported as zero. All samples were analyzed by technicians who were blind to the parent’s report of the child’s exposure to environmental tobacco smoke [21].

We measured the psychological environment, defined as maternal social support, life events (number of stressful events within the past year), and maternal psychological status. The social support and life event measures were adapted from instruments used in the Human Population Laboratory studies [6] and the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview [28], respectively. Maternal psychological status was measured with the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) [56]; for depressive symptoms. The CES-D is a 20-item self-report measure developed for use in general population samples. This instrument correlates well with other established measures of depression (e.g., Zung, r=.90; Beck, r=.81), establishing its validity [51]. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (SS-TPI) [63] was used to assess anxiety and hostility. This is a self-report measure of transitory (i.e., state) and dispositional (i.e., state) anger, anxiety, curiosity and depression. The SS-TPI consists of eight 10-item subscales: state and trait subscales including anxiety, anger, curiosity, and depression. The psychometric properties of this instrument have been examined extensively on a variety of populations [63].

2.5. Neurobehavioral Outcome Measures

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [1] has 118 problem items and 20 social competence items that provide scores for eight problem scales, summary internalizing and externalizing scales, and the total problem score. The problem scales include measures for anxious/depressed, withdrawn, somatic, aggressive, delinquent, attention, thought, and social problem behaviors. The CBCL has demonstrated good test-retest reliability and discriminative validity on large normative samples. The author recommends that the raw scores be used for the separate CBCL scales [1]. These raw scores are not adjusted for age or gender, so child age and gender were considered as covariates in the analyses.

The Routh Activity Scale (RAS) [59] is a maternal report that measures child activity levels during daily routines such as playtime, mealtimes, and bedtime. This measure identifies children who are hyperactive [58]. There was convergent validity between the RAS and other parent ratings of activity in a large, non-referred sample [13].

The Swanson, Nolan and Pelham scale (SNAP) [54] is a 25-item rating scale completed by mothers to assess their child’s activity level, attention span, impulsivity, and peer interactions. Pelham and Bender [54] reported that 92% of the children defined as hyperactive on the SNAP also were termed hyperactive on the Conner’s Teacher Rating Scale.

The EAS temperament survey consists of 20 items on a 5-point scale [11]. The mother is asked to rate her child in terms of emotionality or distress, degree of activity, sociability, and shyness. The EAS is appropriate for use with less educated samples because of the straightforward wording of the questions.

The Test of Variables of Attention (TOVA-A) [39] is an auditory continuous performance test designed to assess auditory processing and attention problems in children and adults. This non-language-based test requires no left-right hand discrimination or sequencing, and is designed to measure attention and impulse control. The TOVA-A has been extensively normed with 2550 children and teenagers (ages 6–19).

The Stoop Color/Word Interference Test measures mental flexibility, specifically the ability of the subject to shift a perceptual set to conform to changing demands. The subject is presented with three different stimulus pages. On the first page, color names are presented and the subject has to read the words as quickly as possible. On the second page, words are printed in red, green, or blue ink and the subject has to name the color. On the third page, color names are presented, but printed in different color ink and the subject has to name the color of the ink as fast as possible. The subject must inhibit reading the words, the more salient response. The Golden [36] version of this test was be used.

The screening version of the Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning (WRAML-S) examines: 1) picture memory – a pictorial scene is presented for 10 seconds followed by a scene that is different, and the child is asked to identify the differences, 2) design memory - a geometric design is presented for 5 seconds which is then drawn from memory, 3) verbal learning -16 words are read aloud and 4 free-recall test trials are administered, and 4) story memory - child hears story and then retells it. In addition to an accuracy-based scaled score for each measure, a summary screening index score is also obtained. This briefer screening form is highly correlated (r=.86) with the standard WRAML. Normative data have been collected on children 5–10 and 11–15 years of age that were selected to match the 1980 U.S. Census distribution [61].

2.6. Data Analysis

The outcome variables were the RAS, WRAML score, SNAP scales, EAS scales, TOVA-A scales, raw scores of the CBCL total score and attention, delinquency, aggression, internalizing, and externalizing subscales, and the scores for baseline response processing (Word, Color) and the interference task (Color/Word) of the Stroop test. A t-test was used to compare the behavioral outcomes between the two groups without adjusting for any covariates. This was followed by a multivariate analysis including significant covariates.

The independent variables used in the bivariate analyses were “any/none” PCSE separately using PCSE in the first and PCSE in the third trimesters. Bivariate associations between PCSE and the other covariates, and then bivariate associations between PCSE and each of the neurobehavioral outcome measures were examined.

Stepwise linear regressions were used to examine the effects of PCSE on each of the continuous neurobehavioral outcomes at any time during pregnancy. Separate regressions were conducted using PCSE as a continuous (average cigarettes per day during pregnancy) and dichotomous (10+ cigs per day/none) predictor from first and third trimesters. Demographic covariates in all analyses included maternal age (years), education (years), income ($/month), presence of an adult male in the household (present/not present), child age (years), ethnicity (European American/African American), gender (male/female), prenatal alcohol (average drinks/day, log transformed) and prenatal marijuana exposure (average joints/day, log transformed). Other illicit drug use during pregnancy was rare and was not considered in these analyses.

The modified Cook’s distance [16] was used to identify influential cases, and the standardized residuals were used to identify extreme outliers. The results reported here excluded influential and outlier cases. One-sided -values were used because we hypothesized that PCSE was associated with increased neurobehavioral problems.

3. Results

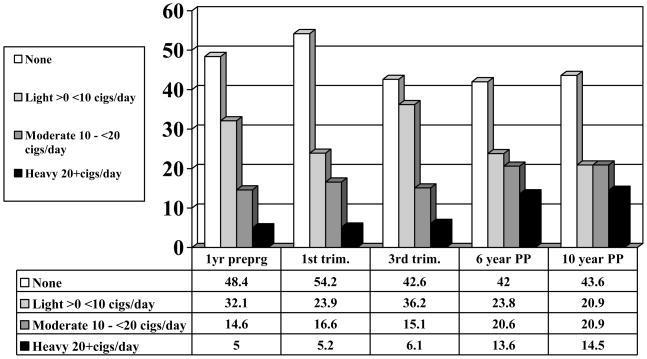

Half (52%) of the pregnant teenagers in this sample used tobacco the year prior to becoming pregnant, and almost half continued to smoke during the first trimester of the index pregnancy (Figure 1). In fact, rates of smoking increased across the teenage pregnancy. By the third trimester, 57% of the sample was using tobacco. Forty-six percent of the participants used alcohol and 15% used marijuana during the first trimester. Alcohol and marijuana use decreased by the end of the pregnancy, with only 8% of the mothers reporting any drinking, and less than 4% continuing to use marijuana in the third trimester. Maternal smoking during pregnancy was significantly associated with other prenatal substance use, so children exposed to PCSE were also more likely to be exposed to prenatal alcohol and marijuana.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Smoking from Pre-Pregnancy to 10 years Postpartum

3.1. Bivariate Relationships among PCSE and Covariates

As described in another report [26], tobacco use remained high among these mothers a decade after the index delivery. At the 10-year follow-up, there were significant demographic differences between the mothers who smoked during pregnancy and the mothers who did not smoke during pregnancy. The mothers who smoked were older, had older children, and were more likely to be married or to have a man in the household. European American mothers were significantly more likely to smoke cigarettes (70% vs. 55% of African American mothers) whereas African American mothers were significantly more likely to use marijuana (28% vs. 13% of the European American mothers). The mothers who smoked during pregnancy had higher scores for depression, anxiety and hostility at the 10-year follow-up. However, there were no statistically significant differences between prenatal smokers and nonsmokers in family income, number of life events, and quality of the home environment 10 years after the teenage pregnancy.

Children exposed to PCSE were significantly more likely to be exposed currently to environmental tobacco as measured by their urine cotinine levels (M = 16.2 ng/ml vs. 8 ng/ml, respectively, p < .001). Therefore, ETS was included as a covariate in the multivariate analyses. There were no statistically significant differences between children who had current ETS compared to those who did not have ETS in their current environment with respect to family income, number of life events reported by caretakers, and quality of the home environment.

3.2. Bivariate Relationships among PCSE and NB Outcomes

As seen in Table 1, there were significant bivariate associations between PCSE and NB outcomes at age 10. For the sake of brevity, only the results of the first trimester PCSE (any/none) analyses are presented in the table. In this comparison, PCSE children had significantly higher total problem scores and more internalizing and externalizing problems on the CBCL. They also had higher scores on the CBCL aggression and delinquency subscales than the offspring without PCSE. Exposed children had more problems with attention, impulsivity, and their peers as measured by the SNAP, although they were rated by their mothers as more sociable on the EAS than were unexposed children. There were no statistically significant differences by PCSE on the WRAML, TOVA-A, or Stroop. Third trimester PCSE significantly predicted more problems on the CBCL anxiety, attention, internalizing, externalizing and total scores, and more impulsivity on the SNAP.

Table 1.

Mean scores on Neurobehavioral Outcomes by First Trimester PCSE exposure

| NB measure | Scale | NO PCSE | PCSE | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL | Total | 48.9 | 53.1 | 0.005 |

| Externalizing | 49.5 | 54.4 | 0.002 | |

| Internalizing | 49.1 | 51.7 | 0.050 | |

| Attention Problems | 55.0 | 56.3 | NS | |

| Aggression | 53.0 | 56.1 | 0.040 | |

| Delinquency | 55.6 | 58.0 | 0.050 | |

| Routh | Activity | 34.1 | 37.7 | 0.010 |

| SNAP | Activity Problems | 9.2 | 10.3 | 0.050 |

| Attention Problems | 8.3 | 9.3 | 0.030 | |

| Impulsivity Problems | 9.6 | 11.1 | 0.010 | |

| Peer Problems | 10.8 | 12.0 | 0.050 | |

| EAS | Emotionality | 2.4 | 2.6 | NS |

| Activity | 3.7 | 3.8 | NS | |

| Sociability | 3.2 | 3.5 | 0.001 | |

| Shyness | 2.6 | 2.5 | NS | |

| WRAML | Screen | 86.7 | 88.8 | NS |

| TOVA | Omission-A | 2.3 | 2.7 | NS |

| Omission-B | 6.1 | 8.2 | NS | |

| Commission-A | 1.2 | 1.9 | NS | |

| Commission-B | 16.4 | 17.9 | NS | |

| STROOP | Word | 44.2 | 44.3 | NS |

| Color | 47.6 | 47.0 | NS | |

| Color/Word | 44.9 | 45.3 | NS | |

NS = not statistically significant (p > .05)

3.3. Multivariate Relationships among PCSE and NB Outcomes

The multivariate analyses adjusting for demographic characteristics, prenatal exposure to other substances, the child’s current exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, and maternal psychological characteristics are presented in Table 2. PCSE from first and third trimesters was considered in the models as either a continuous (average daily cigarettes) or dichotomous variable (10 or more cigarettes per day) were. Exposed offspring had more total problems and higher rates of delinquent, aggressive, and externalizing behaviors on the CBCL (Table 2). First trimester exposure significantly predicted activity on three different measures of child activity, including the Routh, EAS, and SNAP. Exposed children were also more impulsive and had more problems with peers (SNAP). Deficits were observed in both baseline response processing measures and on the more complex interference task of the Stroop Color/Word Test. Third trimester PCSE (continuous) significantly predicted higher activity on the EAS. A dose-response effect was found on the CBCL delinquency subscale and the Stroop Word and Color Word tasks in the regressions using continuous PCSE. PCSE effects were seen with the 10+ cigarettes per day cutoff, indicating a threshold effect at the level of half a pack of cigarettes per day. Most of our effects were from the first trimester. Other significant predictors of offspring behavior problems included male gender, African American ethnicity, not in maternal custody, and maternal psychological variables such as depression, anxiety, and hostility.

Table 2.

First and Third trimester PCSE and Other Significant Predictors of Neurobehavioral Outcomes

| NB measure | Scale | PCSE | Significant covariates | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL | Total | 1st trimester 10+ cigs/day | Not in maternal custody | .20 |

| Maternal depression | ||||

| Maternal hostility | ||||

| Externalizing | 1st trimester 10+ cigs/day | Not in maternal custody | .19 | |

| African American ethnicity | ||||

| Male child | ||||

| Maternal depression | ||||

| Maternal hostility | ||||

| Delinquency | 1st trimester 10+ cigs/day continuous | Not in maternal custody | .22 | |

| African American ethnicity | ||||

| Male child | ||||

| Maternal depression | ||||

| Maternal hostility | ||||

| Aggression | 1st trimester 10+ cigs/day | Not in maternal custody | .16 | |

| Male child | ||||

| Maternal depression | ||||

| Maternal hostility | ||||

| Routh | Activity | 1st trimester 10+ cigs/day | Male child | .09 |

| Maternal hostility | ||||

| SNAP | Activity Problems | 1st trimester 10+ cigs/day | African American ethnicity | .08 |

| Male child | ||||

| Maternal anxiety | ||||

| Impulsivity Problems | 1st trimester 10+ cigs/day | African American ethnicity | .13 | |

| Not in maternal custody | ||||

| Maternal hostility | ||||

| Maternal anxiety | ||||

| Personality Problems | 1st trimester 10+ cigs/day | African American ethnicity | .11 | |

| Male child | ||||

| Maternal depression | ||||

| Maternal hostility | ||||

| EAS | Activity | 1st trimester 10+ cigs/day | Environmental tobacco | .04 |

| Maternal hostility | ||||

| 3rd trimester 10+ cigs/day continuous | ||||

| STROOP | Word | 1st trimester 10+ cigs/day continuous | Male child | .10 |

| African American ethnicity | ||||

| Maternal hostility | ||||

| Color | 1st trimester 10+ cigs/day | Male child | .10 | |

| African American ethnicity | ||||

| Color/Word | 1st trimester 10+ cigs/day continuous | African American ethnicity | .09 | |

4. Discussion

In this study, offspring with PCSE had more delinquent, aggressive, and externalizing behaviors than offspring who were not exposed to tobacco prenatally. They were also more active and impulsive, had more problems with peers, and had more difficulty on tasks requiring selective attention and response inhibition. Evidence from the animal literature provides biological support for our findings in humans. Specifically, prenatal nicotine exposure increases motor activity in laboratory animals [66–68]. This increase in activity is comparable to the increased activity, impulsivity and associated behavior problems seen in exposed human children.

This study was the first to examine the effects of PCSE on neurobehavioral outcomes in the offspring of teenage mothers. Although smoking was prevalent in this group (and similar to adult rates) the average daily cigarette exposure was lower than levels found in pregnant adult women selected from the same prenatal clinic [18,23,72], resulting in a lower daily dose. Most of the significant PCSE findings in this study resulted from a threshold of 10 or more average daily cigarettes. Nonetheless, there was a dose-response effect of prenatal tobacco on delinquency (CBCL) and mental flexibility (Stroop), indicating that even lower levels of cigarette exposure are problematic for some of the neurobehavioral outcomes in these children.

The women in this study were pregnant teenagers who were recruited from a prenatal clinic. A strength of the study is that the teenagers were not selected based on tobacco or drug use. The tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use represented the entire spectrum of adolescent drug behavior from no use to heavier use. Although the demographic distribution of our sample does not reflect the total Pittsburgh population, it is representative of pregnant teenagers who attend a prenatal clinic in a large inner-city hospital. Another strength of our study was that other prenatal substance exposures were measured prospectively and considered in the statistical analyses. Prenatal alcohol exposure did not predict any of the child outcomes in our analyses. This finding is inconsistent with studies that have reported a relationship with fetal alcohol exposure and decreased attention and more aggression in exposed offspring [15,43]. We also did not find any relation between prenatal marijuana exposure and child outcomes, as has been reported by Fried [33] and Goldschmidt and colleagues [38] among offspring of adult mothers. However, both alcohol and marijuana use were low in this sample and most of the use was confined to first trimester, as most of the teenagers quit or decreased their use in later pregnancy. Cigarette smoking did not follow a similar pattern of reduction after the first trimester: in fact, more pregnant teens smoked later in their pregnancies.

A crucial aspect of this study was the collection of information on postpartum ETS. Others have found effects of ETS on child behavioral problems [e.g., 7,70,73]. However, few studies have considered exposures from both pre- and post-natal environments [46]. PCSE remained an independent predictor of more activity, impulsivity and externalizing problems in our sample after we controlled for ETS. ETS, however, was a significant independent predictor of child activity level on the EAS activity subscale, in addition to the separate effects of PCSE. These results demonstrate the necessity of considering both prenatal and postnatal effects of tobacco exposure on child behavior problems.

The present study had several limitations. PCSE was based on maternal self-report and was not verified biologically. To increase the accuracy of the reported data, we constructed detailed questions, carefully selected interviewers, and extensively trained our staff in interview techniques. The correlations between reports from each trimester of pregnancy were high (the correlation between first and third trimester smoking was .74), demonstrating consistency in reporting and indicating that maternal reports were accurate. Biological measures have disadvantages, in that they measure use for only a short window of time, whereas questionnaire data can elicit patterns of use over time. As tobacco and other drug use tend to be more sporadic among teenagers than adults [18], biological measures may miss a significant amount of tobacco and other drug use. We did not have data to examine genetic vulnerabilities to neurobehavioral outcomes [37]. For example, Langley and colleagues [45] reported that maternal smoking and the dopamine receptor D5 gene (DRD5) interacted to predict antisocial behavior among 9-year-old children with ADHD. Although our study did not collect genetic material, we did control for maternal psychological symptoms, including depression and hostility, that may have a hereditary role in both cigarette use and neurobehavioral problems.

5. Conclusions

Our findings on PCSE and child behavior are consistent with earlier results, when the children were assessed at 6 years of age [20]. At that age, we found that PCSE predicted increased activity levels and more attention problems. At age 10, we demonstrated higher activity, more externalizing behaviors, and problems with selective attention and response inhibition. This consistency of findings over time gives added credence to our results and suggests that children with PCSE may be identified early. Moreover, these results add to the converging evidence that children exposed to PCSE will continue to have NB deficits that will present later as behavior problems.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) (DA09275 PI: M Cornelius) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA08284; PI: M Cornelius). The authors wish to thank our NIDA Project Officer, Dr. Vincent Smeriglio, for his guidance and encouragement of this project from its inception through its continuation. The authors also wish to thank the young women and children who made this study possible by contributing their time and sharing their experiences with our interviewers and field staff.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Achenbach T. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams KE, Melvin CL, Raskind-Hood CL. Sociodemographic, insurance, and risk profiles of maternal smokers post the 1990s: How can we reach them? Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1121–9. doi: 10.1080/14622200802123278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen AM, Dietz PM, Tong VT, England L, Prince CB. Prenatal smoking prevalence ascertained from two population-based data sources: birth certificates and PRAMS questionnaires, 2004. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:586–92. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker P, Mott F. National Longitudinal Study of Youth Child Handbook. Center for Human Resource Research: Ohio State University; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batstra L, Hadders-Algra M, Neeleman J. Effect of antenatal exposure to maternal smoking on behavioural problems and academic achievement in childhood: prospective evidence from a Dutch birth cohort. Early Hum Dev. 2003;75:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkman L, Syme S. Social networks, host resistance and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1979;109:186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun J, Kahn R, Froehlich T, Lanphear B. Exposures to environmental toxicants and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in U.S. children: NHANES 2001–2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:956–962. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brennan PA, Grekin ER, Mednick SA. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and adult male criminal outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:215–219. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke JD, Loeber RL, Lahey BB. Adolescent conduct disorder and interpersonal callousness as predictors of psychopathy in young adults. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2007;36:334–46. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns L, Mattick RPC. Wallace Smoking patterns and outcomes in a population of pregnant women with other substance use disorders. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:969–74. doi: 10.1080/14622200802097548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buss AH, Plomin R. Temperament: early developing personality traits. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Kluwer Academic/Plenum; New York, NY: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Button T, Maughan B, McGuffin P. The relationship of maternal smoking to psychological problems in the offspring. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83:727–732. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell S, Breaux A. Maternal ratings of activity level and symptomatic behaviors in a nonclinical sample of young children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1983;8:73–82. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/8.1.73. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter S, Paterson J, Gao W. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and behaviour problems in a birth cohort of 2-year-old Pacific children in New Zealand. Early Hum Dev. 2008;84:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coles C, Platzman K, Raskind-Hood C. A comparison of children affected by prenatal alcohol exposure and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997;20:150–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook RD, Weisberg S. Residuals and Influence in Regression. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornelius MD, Day NL. Developmental consequences of prenatal tobacco exposure. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2009;22:121–125. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328326f6dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornelius M, Day N, Richardson G, Taylor P. Epidemiology of substance abuse during pregnancy. In: Ott P, Tarter R, Ammerman R, editors. Sourcebook on Substance Abuse: Etiology, Epidemiology, Assessment and Treatment. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 1999. pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornelius M, Goldschmidt L, Day N, Larkby C. Prenatal substance use among pregnant teenagers: A six-year follow-up of effects on offspring growth. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2002;24:703–710. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(02)00271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cornelius MD, Goldschmidt L, DeGenna N, Day NL. Smoking during teenage pregnancies: effects on behavioral problems in offspring. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:739–50. doi: 10.1080/14622200701416971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cornelius M, Goldschmidt L, Dempsey D. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure in low income six-year-olds: Parent report and urine cotinine measures. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5:333–339. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000094141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornelius MD, Leech SL, Goldschmidt L, Day NL. Is prenatal tobacco exposure a risk factor for early adolescent smoking? A follow-up study. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2005;27:667–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cornelius M, Taylor P, Geva D. Prenatal tobacco and marijuana use among adolescents: Effects on offspring gestational age, growth and morphology. Pediatrics. 1995;95:438–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darroch J, Frost J, Singh S. Occasional Report. 3. New York: AGI; 2001. Teenage Sexual and Reproductive Behavior in Developed Countries: Can More Progress Be Made? p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Day NL, Robles N. Methodological issues in the measurement of substance use. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1989;562:8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb21002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Genna NM, Cornelius MD, Donovan J. Risk factors for young adult substance use among women who were teenage mothers. Addictive Behaviors. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiFranza J, Aligne A, Weitzman M. Prenatal and Postnatal Environmental Tobacco Smoke Exposure and Children’s Health. Ped. 2004;113:1007–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dohrenwend BS, Dohrenwend BP. Stressful life events: Their nature and effects. Wiley; New York: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eskenazi B, Castorina R. Association of prenatal maternal or postnatal child environmental tobacco smoke exposure and neurodevelopmental and behavioral problems in children. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:991–1000. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eskenazi B, Trupin L. Passive and active maternal smoking during pregnancy as measured by serum cotinine and postnatal smoke exposure. 2. Effect on neurodevelopment at age 5 years. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;142:S19–S29. doi: 10.1093/aje/142.supplement_9.s19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Maternal smoking before and after pregnancy: effects on behavioral outcomes in middle childhood. Pediatrics. 1993;92:815–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and psychiatric adjustment in late adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:721–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fried P. Adolescents prenatally exposed to marijuana: Examination of facets of complex behavior and comparison with the influence of in utero cigarettes. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42:97S–102S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb06009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gatzke-Kopp LM, Beauchaine TP. Direct and passive prenatal nicotine exposure and the development of externalizing psychopathology. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2007;38:255–269. doi: 10.1007/s10578-007-0059-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gold M. Marijuana. Plenum; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Golden CJ. Stroop Color and Word Test: A Manual for Clinical and Experimental Uses. Chicago, Illinois: Skoelting; 1978. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golding G. The importance of a genetic component in longitudinal birth cohorts. Paedetric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2009;23:174–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2009.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldschmidt L, Day N, Richardson G. Effects of prenatal marijuana exposure on child behavior problems at age 10. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22:325–336. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(00)00066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenberg LL, Leark R, Dupuy T, Corman C, Kindschi C, Cenedela M. Test of Variables of Attention Auditory. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; Odessa, FL: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: preliminary data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2007;56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huijbregts SC, Séguin JR, Zoccolillo M, Boivin M, Tremblay RE. Maternal prenatal smoking, parental antisocial behavior, and early childhood physical aggression. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:437–53. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huizink AC, Mulder EJ. Maternal smoking, drinking or cannabis use during pregnancy and neurobehavioral and cognitive functioning in human offspring. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;20:24–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobson J, Jacobson S. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on child development. Alcohol Research Health. 2002;26:282–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kandel DB, Wu P, Davies M. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and smoking by adolescent daughters. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1407–13. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.9.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Langley K, Turic D, Rice F, Holmes P, van den Bree M, Craddock N, Kent L, Owen M, O’Donovan M, Thapar A. Testing for gene X environment interaction effects in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and associated antisocial behavior. Am J Med Genetics, Part B (Neuropsychiatric genetics) 2008;147B:49–53. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Linnet K, Dalsgaard S, Obel C. Maternal lifestyle factors in pregnancy risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and associated behaviors: review of current evidence. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1028–1040. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mansi G, Raimondi F, Pichini S. Neonatal Urinary Cotinine Correlates With Behavioral Alterations in Newborns Prenatally Exposed to Tobacco Smoke. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:257–261. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e31802d89eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin LT, McNamara M, Milot A, Bloch M, Hair EC, Halle T. Correlates of smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32:272–82. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mick E, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Sayer J, Kleinman S. Case-control study of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and maternal smoking, alcohol use, and drug use during pregnancy. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:378–85. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Chen L, Jones J. Is maternal smoking during pregnancy a risk factor for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children? Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1138–42. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.9.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Myers JK, Weissman M. Use of a self-report symptom scale to detect depression in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137:1081–1084. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olds DD. Tobacco exposure and impaired development: a review of the evidence. MRDD Research Reviews. 1997;3:257–269. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Orlebeke JF, Knol DL, Verhulst FC. Child behavior problems increased by maternal smoking during pregnancy. Arch Environ Health. 1999;54:15–9. doi: 10.1080/00039899909602231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pelham W, Bender M. Peer relationships in hyperactive children. Description and treatment. Advances in Learning Behavior Diseases. 1982;1:365–436. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Picket K, Rathouz P, Dukic V, Kasza K, Niessner M, Wright R, Wakschlag L. The complex enterprise of modeling prenatal exposure to cigarettes: What is enough? Ped Perinatal Epidemiol. 2009;23:160–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.01010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Radloff L. the CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measures. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robinson M, Oddy W, Li J, Kendall G, Garth E, de Klerk N, Silburn S, Zubrick S, Newnham J, Stanley F, Mattes E. Pre- and postnatal influences on preschool mental health: a large-scale cohort study. J Child Psychol Psychiat Allied Disciplines. 2008;49:1118–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Routh DK, Schroeder CS. Standardized playroom measures as indices of hyperactivity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1976;4:199–207. doi: 10.1007/BF00916522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Routh D, Schroeder C, O’Tuama L. Development of activity level in children. Developmental Psychology. 1974;10:163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shea A, Steiner M. Cigarette smoking during pregnancy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:267–278. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sheslow D, Adams W. Manual for the Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning. Wilmington DE: Jastak Associates; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Slotkin T. If nicotine is a developmental neurotoxicant in animal studies, dare we recommend nicotine replacement therapy in pregnant women and adolescents? Neurotox Teratol. 2008;30:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene R. Manual for the State Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stroud L, Paster R, Goodwin M. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and neonatal behavior: A large-scale community study. Ped. 2009;123:e842–e848. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stroud L, Paster R, Papandonatos G, Niaura R, Salisbury A, Battle C, Lagasse L, Lester B. Maternal Smoking during Pregnancy and Newborn Neurobehavior: Effects at 10 to 27 Days. Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;154:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thomas J, Garrison M, Slawecki C, Ehlers C, Riley E. Nicotine exposure during the neonatal brain growth spurt produces hyperactivity in preweanling rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2000;22:695–701. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(00)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tizabi Y, Popke E, Rahman M, Nespor S, Grunberg N. Hyperactivity induced by prenatal nicotine exposure is associated with an increase in cortical nicotinic receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;58:141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00461-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vaglenova J, Birru S, Pandiella N, Breese C. An assessment of the long-term developmental and behavioral teratogenicity of prenatal nicotine exposure. Behav Brain Res. 2004;150:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weissman M, Warner V, Wickramaratne P, Kandel D. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and psychopathology in offspring followed to adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:892–899. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weitzman M, Gortmaker S, Sobol A. Maternal smoking and behavior problems of children. Ped. 1992;90:2–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Williams G, O’Callaghan M, Najman J, Bor W, Andersen M, Richards D, Chunley U. Maternal cigarette smoking and child psychiatric morbidity: A longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 1998;102:e11. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Willford J, Day N, Cornelius M. Maternal Tobacco Use during pregnancy: Epidemiology and effects on offspring. In: Miller Michael., editor. Development of the mammalian central nervous system: lessons learned from studies on alcohol and nicotine exposure. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 315–328. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yolton K, Khoury J, Hornung R, Dietrich K, Succop P, Lanphear B. Environmental Tobacco Smoke Exposure and Child Behaviors. J Develop and Beh Ped. 2008;29:456–463. doi: 10.1097/dbp.0b013e31818d0c21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]