Abstract

We examined the effect of cognitive fatigue on the Attention Networks Test (ANT). Participants were 228 non-demented older adults. Cognitive fatigue was operationally defined as decline in alerting, orienting, and executive attention performance over the course ANT. Anchored in a theoretical model implicating the frontal basal ganglia circuitry as the core substrate of fatigue, we hypothesized that cognitive fatigue would be observed only in executive attention. Consistent with our prediction, significant cognitive fatigue effect was observed in executive attention but not in alerting or orienting. In contrast, orienting improved over the course of the ANT and alerting showed a trend, though insignificant, that was consistent with learning. Cognitive fatigue is conceptualized as an executive failure to maintain and optimize performance over acute but sustained cognitive effort resulting in performance that is lower and more variable than the individual’s optimal ability.

Keywords: Cognitive Fatigue, Executive Control, Aging, Attention Networks

Fatigue is a common but understudied symptom in aging (Avlund, Pedersen, & Schroll, 2003; Schultz-Larsen & Avlund, 2007; Wijeratne, Hickie, & Brodaty, 2007). Epidemiological studies indicate that 27–50% of older adults in community dwellings (Hellstrom & Hallberg, 2004; Reyes-Gibby, Mendoza, Wang, Anderson, & Cleeland, 2003; Wijeratne et al., 2007) and as high as 98% in long-term care settings (Liao & Ferrell, 2000) complain of moderate to severe levels of fatigue. Fatigue in older adults is associated with loss of functional independence (Liao & Ferrell, 2000), depression (Hayslip, Kennelly, & Maloy, 1990) and elevated risk for future adverse outcomes including disability and mortality (Avlund, Rantanen, & Schroll, 2007; Avlund, Vass, & Hendriksen, 2003; Schultz-Larsen & Avlund, 2007).

Fatigue is multi-factorial including both cognitive and physical components. While there is no conceptual framework or definition of fatigue that is universally accepted (DeLuca, 2005b), recent work makes a distinction between peripheral and central fatigue (Chaudhuri & Behan, 2000). Peripheral fatigue is attributed to known mechanisms such as the failure of neuromuscular transmission, metabolic disturbances, defects of muscle membranes, or a peripheral circulatory failure (Chaudhuri & Behan, 2004). In contrast, central or cognitive fatigue represents a failure to sustain attention that requires self-motivation to optimize performance (Chaudhuri & Behan, 2004). DeLuca (2005b)has outlined four different approaches to measure cognitive fatigue: 1. Decreased performance following an extended period of time (Prolonged effort); 2. Decreased performance after a challenging mental exertion; 3. Decreased performance after a challenging physical exertion; and 4. Decreased performance during acute but sustained mental effort. The last conceptualization has received the most empirical support (Bryant & DeLuca, 2004; DeLuca, 2005a; Roelcke, Kappos, Lechner-Scott, Brunnschweiler, Huber, Ammann, et al., 1997; Schwid, Tyler, Scheid, Weinstein, Goodman, & McDermott, 2003) and is most closely related to Chaudhuri and Behan’s definition of “central fatigue.”

It is also important to distinguish self-reported subjective assessments of fatigue, also known as fatigability, from objective assessments of cognitive or physical fatigue. Most clinical assessments of fatigue are based on subjective reports. Self-reports of fatigue correlate with depression (Bakshi, Shaikh, Miletich, Czarnecki, Dmochowski, Henschel, et al., 2000; Gold & Irwin, 2006) and anxiety (Skerrett & Moss-Morris, 2006) but not with objective measures of disease severity, duration or course (Barak & Achiron, 2006; Chaudhuri & Behan, 2004; Pittion-Vouyovitch, Debouverie, Guillemin, Vandenberghe, Anxionnat, & Vespignani., 2006; Rasova, Brandejsky, Havrdova, Zalisova, & Rexova, 2005; Skerrett & Moss-Morris, 2006; van der Werf et al., 1998). Further, whereas fatigue correlates with perceived cognitive dysfunction (Middleton, Denney, Lynch, & Parmenter, 2006) previous research has failed to demonstrate meaningful associations between subjective reports of fatigue (fatigability) and a wide range of neuropsychological measures (Bailey, Channon, & Beaumont, 2007; DeLuca, 2005a; Krupp & Elkins, 2000; Middleton et al., 2006; Parmenter, Denney, & Lynch, 2003). However, Holtzer and Foley (2009) provided a first report revealing strong associations between subjective assessment of fatigue and cognitive performance on a computerized dual-task paradigm that experimentally manipulated executive control demands. In this study subjective assessment of fatigue was related to both processing speed and accuracy only in the most demanding dual-task condition (Holtzer & Foley, 2009).

Recent functional imaging studies suggest that the frontal basal ganglia circuitry may be a core substrate in the pathogenesis of central fatigue (Chaudhuri & Behan, 2004; Niepel, Tench, Morgan, Evangelou, Auer, & Constantinescu., 2006; Roelcke et al., 1997; Tellez, Alonso, Rio, Tintore, Nos, Montalban, 2007). Moreover, a recent study showed that cognitive behavioral therapy resulted in increased brain volume in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome (de Lange, Koers, Kalkman, Bleijenberg, Hagoort, van der Meer et al., 2008). The same study also showed that increased gray matter volume in this brain region was associated with improved executive function (de Lange et al., 2008). These findings suggest that tasks that are mediated, at least in part, by the prefrontal cortex (PFC) may be more sensitive to the effect of cognitive fatigue. The effect of fatigue on test performance has been widely recognized in the neuropsychological literature (Lezak, 2004; Mitrushina, 2005), administration manuals of cognitive tests (Wechsler, 2008) and by the American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on the assessment of age-consistent memory decline and dementia (APA Presidential Task Force, 1998).

However, examining cognitive fatigue quantitatively is complicated by several challenges. Standardized neuropsychological tests measure different constructs that vary in terms of their sensitivity to cognitive fatigue. Further, individual neuropsychological tests tend to be multi-factorial and assess abilities that likely have differential sensitivity to cognitive fatigue. Therefore, empirical assessment of cognitive fatigue taking into account the effects of test order and time on multiple tests with varying degrees of difficulties and sensitivity to fatigue seems arduous if not impossible. Optimally, to address these challenges, the assessment of cognitive fatigue requires repeated trials with identical stimuli presented through the same sensory modality (e.g., visual) and identical responses (e.g., pressing a key or a mouse when the probe appears). However, even in tests that satisfy these demands several issues remain in assessing cognitive fatigue. First, decline in performance over time is a necessary condition for both conceptual and operational definitions of cognitive fatigue. For example, a recent study (DeLuca, Hillary, & Wylie 2008) aimed to identify the neural substrate of cognitive fatigue in individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS) and healthy controls. However, the paradigm used did not elicit cognitive fatigue (i.e., decline in performance). Hence, inferences about the substrate of cognitive fatigue were made by comparing brain activations in the MS and control groups without demonstrating, behaviorally, that cognitive performance declined over time (DeLuca et al., 2008). Second, it is necessary to measure cognitive fatigue and cognitive performance separately to ensure that the two are not confounded. That is, worse cognitive performance should not be confused with cognitive fatigue, and effects of cognitive fatigue, when demonstrated, should take into account within or between group differences in cognitive performance. Previous studies examining cognitive fatigue failed to directly address these important issues (Bryant & DeLuca, 2004; Cook, O'Connor, Lange, & Steffener, 2007; Schwid et al., 2003). Finally, it is noteworthy that the failure to sustain attention resides at the core of both conceptual and operational definitions of cognitive fatigue. Thus, any task that is used to assess cognitive fatigue should impose significant demands on attention resources.

Herein, we aimed to determine cognitive fatigue effects in a large cohort of non-demented older adults. A large corpus of research (Craik, 1982; McDowd & Shaw, 2000) including meta-analytic studies (Verhaeghen & Cerella, 2002; Verhaeghen, Steitz, Sliwinski, & Cerella, 2003) indicate that attention resources decline in older adults suggesting that this population may be optimal to study cognitive fatigue. However, attention is a multi-faceted construct (Pashler, 1998) with distinct components that can be distinguished both theoretically and empirically (Miyake, Friedman, Emerson, Witzki, Howerter, & Wager, 2000), and likely have differential sensitivity to cognitive fatigue.

The attention network test (ANT) examines simultaneously alerting, orienting, and executive attention (Fan, McCandliss, Fossella, Flombaum, & Posner, 2005; Fan, McCandliss, Sommer, Raz, & Posner, 2002; Posner & Petersen, 1990). In the ANT there are three warning cue conditions (no, alert, or orient) that can precede each target stimulus. Alerting cues indicate that the target stimulus is about to appear (i.e., temporal cue). Alerting requires the individual to achieve and maintain an alert state and has been linked to right parietal and frontal regions (Coull, Frith, Frackowiak, & Grasby, 1996; Marrocco, Witte, & Davidson, 1994). Orienting cues provide both temporal and spatial (i.e., location on the screen) information about the target stimulus. Orienting requires the individual to select specific information from sensory input and is thought to be associated with the superior parietal lobe (Corbetta, Kincade, Ollinger, McAvoy, & Shulman, 2000). The target stimulus of the ANT (i.e., central arrow) points either leftward or rightward and is surrounded by two flanker arrows on each side that provide either no, congruent, or incongruent information about the target stimulus. In the incongruent condition, flankers provide conflicting information that causes an interference that typically results in an increase in the time required to respond to the target, as compared to the congruent flanker condition. Executive attention requires the individual to resolve conflicting visual information and is mediated by the anterior cingulate and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Bush, Luu, & Posner, 2000; MacDonald, Cohen, Stenger, & Carter, 2000). Alerting, orienting and executive attention have been linked to different brain substrates (Fan et al., 2005; Fan et al., 2002; Konrad, Neufang, Thiel, Specht, Hanisch, Fan, et al., 2005; Posner & Petersen, 1990) and genetic polymorphisms (Fan, Fossella, Sommer, Wu, & Posner, 2003; Fossella et al., 2002). These three attention networks can be reliably assessed in young and patient populations (Posner & Rothbart, 2007; Raz & Buhle, 2006). We have recently provided evidence for the reliability and network effects of the ANT in non-demented older adults (Mahoney, Verghese, Goldin, Lipton & Holtzer, 2010).

Consistent with previous research (Chaudhuri & Behan, 2000; DeLuca, 2005a) we conceptually defined cognitive fatigue as a failure to sustain attention to optimize task performance during acute but sustained mental effort. Cognitive fatigue was operationally defined as a decline in attention network performance over the course of the ANT. In light of a recent theoretical model implicating the prefrontal basal circuitry as a core substrate of fatigue (Chaudhuri & Behan, 2000, 2004) we hypothesized that cognitive fatigue effects would be demonstrated in the executive attention but not alerting or orienting networks. Further, in any task that requires repeated exposures, learning (i.e., improved performance due to practice) can also be expected. Therefore, we examined whether, in the context of the ANT, learning was also demonstrated.

Method

Participants

Participants were enrolled in the Einstein Aging Study (EAS), a longitudinal study of aging and dementia located at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in Bronx, New York. The study design, recruitment, and follow-up methods have been previously described elsewhere (Lipton, Katz, Kuslansky, Sliwinski, Stewart, Verghese et al., 2003; Verghese, Katz, Derby, Kuslansky, Hall, & Lipton, 2004). Briefly, EAS has used a telephone-based screening procedure to recruit and follow a community-based cohort since 1993. The primary aim of the EAS is to identify risk factors for dementia. Eligibility criteria require that participants be 70 years of age and older, reside in Bronx county, and speak English. Exclusion criteria include severe audiovisual disturbances that would interfere with completion of neuropsychological tests, significant loss of vision, inability to ambulate even with a walking aid or in a wheelchair, and institutionalization. Potential participants over age 70 from the Center for Medicaid/Medicare Services population lists were first contacted by letter, then by telephone, explaining the nature of the study. The telephone interview included verbal consent, a brief medical history questionnaire, and telephone-based cognitive screening tests (Lipton et al., 2003). Following the interview, an age-stratified sample of subjects who matched on a computerized randomization procedure was invited for further evaluation at the medical center. This procedure was implemented to ensure that the individuals included in the EAS represented the Bronx population at that age stratum and that those who agreed to participate were not different from non-responders in terms of key demographic characteristics. Written informed consent was obtained at clinic visits according to study protocols and approved by the Committee on Clinical Investigation (CCI; the institutional review board of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine).

The ANT was incorporated into the experimental procedures of the EAS in 2007. To address the decline in vision inherent in the aging population, we used a variant of the original ANT (Fan et al., 2002) that enhanced the size of the stimuli (see procedures and measures). A total of 228 non-demented subjects (as determined by established clinical case conference diagnostic procedures; Holtzer, Verghese, Wang, Hall, & Lipton, 2008; Verghese, Lipton, Hall, Kuslansky, Katz, & Buschke, 2002) whose ANT performance was above 75% accurate were eligible to participate in the current study. This subsample was comparable in terms of key demographic characteristics to the entire non-demented EAS sample at baseline.

Procedures and Measures

ANT

All ANT sessions were conducted in the same quiet and well lit room. Each participant was tested alone. A research assistant supervised the training and testing procedures. The ANT version used in this study consisted of a 24-trial training block, which was followed by 288 testing trials separated into three 96-trial blocks. Participants were required to attain 75% accuracy or higher during training in order to proceed to the testing session. The total administration time was approximately 35 minutes. Reaction time (RT) and accuracy data for the ANT were recorded by the computer. The participant’s task was to report the direction of the target (i.e., central) arrow by pressing the left mouse button for leftward pointing arrows and the right mouse button for rightward pointing arrows. Participants were required to fixate on a central fixation point (a black cross) visible on the monitor and respond to each stimulus as quickly as possible without making errors. The stimuli employed in the ANT are rows of five black lines with arrowheads that point leftward or rightward and appear directly above or below a central fixation cross. The target stimulus is the central arrow and is always surrounded by two flankers on each side. There are three flanker types: neutral flankers (two dashes on each side of the central arrow), congruent flankers (two arrows on each side that point in the same direction as the central target stimulus), and incongruent flankers (two arrows on each side that point in the opposite direction of the central target stimulus). In addition, there are four types of warning cues that can precede each target trial: no cue, center cue, double cue, and spatial (i.e., orient) cues. Alerting cues indicate when the target stimulus is about to appear. Orienting cues provide both temporal and spatial information with respect to the target stimulus. The actual warning cue is an asterisk (*) that is presented in the center of the screen for center cue conditions, above and below central fixation for double cue conditions, and either above or below central fixation for spatial cue conditions. In the no cue condition, the fixation point (+) remains visible until the target stimulus is displayed. The no cue condition serves as the control, whereas the double and center cue conditions measure alerting, and the spatial cues measure orienting. The stimuli that follow the no, central, and double cue conditions were centrally presented; however, the stimuli that followed the spatial cue conditions were presented 1.06° above or below central fixation depending upon the location of the orienting cue. This visual angle of 1.06° above and below fixation also corresponds to the placement of the asterisks for the double and spatial cue conditions. In the current version of the ANT, the diameter of the cues (i.e., asterisks) was increased from 0.32 cm to 0.64 cm. Similarly, the height of the arrows (i.e., target and flanker stimuli) was increased from 0.32 cm to 0.64 cm, while the width of the arrows was increased from 2.54 cm to 3.81 cm.

Attention networks calculation

Due to concerns of redundancy (see Fan et al., 2005; Mahoney et al., 2010) two-tailed Pearson correlations were used to determine whether the inclusion of neutral and congruent flankers, as well as double and center cue conditions was extraneous. The mean RTs for the neutral and congruent flankers, averaged across cues, were highly correlated (r = 0.96; p < 0.01). The mean RTs for the double and center cues, averaged across flanker types, were also highly correlated (r = 0.97; p < 0.01). Thus, derivation of the attention networks and statistical analyses were based on a two-level flanker (congruent and incongruent) and three-level cue (no, center and orienting). Mean attention network scores were calculated for each of the three blocks and for the entire ANT. Each attention network was calculated using simple subtractions to determine the influence of cues and flankers on reaction times. For alerting, the averaged mean RT of all center cue trials was subtracted from the averaged mean RT of all no cue trials. The center cues are designed to enhance alertness by directing the subject’s attention to the center of the screen, whereas the no cue trials serve as the control. The orienting attention network was obtained by subtracting the averaged mean RT of the orienting cue trials from the averaged mean RT of the center cue trials. The orienting cues provide both temporal and spatial information with respect to the appearance of the target stimulus. Therefore, the derivation of the orienting attention network represents the incremental effect of spatial cues as compared to temporal/alerting cues on ANT performance. For the executive attention network, the averaged mean RT of all congruent trials was subtracted from the averaged mean RT of all incongruent trials. While larger alerting and orienting network scores are indicative of faster cue-related performance, larger executive attention network scores are indicative of worse performance (i.e., longer RTs required for conflict resolution).

Cognitive fatigue

Conceptually, cognitive fatigue was defined as a failure to sustain attention to optimize task performance during acute but sustained mental effort. Operationally, cognitive fatigue was defined as decline in attention network performance over the course of the ANT. Specifically, alerting, orienting and executive attention scores were calculated for each of the three blocks to depict time effects on these attention networks.

Global Disease Status

Trained research assistants used structured clinical interview, and the study physician obtained medical history during the neurological examination independently of the structured clinical interview. Medical history was obtained from multiple sources including significant others or caregivers when available. Family physicians were contacted or hospital records reviewed as needed to obtain additional medical information. Consistent with our previous studies (Holtzer et al., 2008; Holtzer, Friedman, Lipton, Katz, Xue, & Verghese, 2007; Holtzer, Verghese, Xue, & Lipton, 2006; Verghese, Wang, Lipton, Holtzer, & Xue, 2007) dichotomous rating (presence or absence) of diabetes, chronic heart failure, arthritis, hypertension, depression, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, chronic obstructive lung disease, angina, and myocardial infarction was used to calculate a global disease status summary score (range 0–10).

Cognitive Status

The Blessed Information Memory Concentration test (BIMCT; best score: 0 errors and worst possible score: 32 errors), is a screening test for cognitive impairment that is highly related to functional status, and scores of 8 or higher are associated with presence of dementia (Blessed, Tomlinson, & Roth, 1968). This test has high test-retest reliability (0.86) and correlates well with the pathology of Alzheimer disease (Fuld, 1978; Grober, Buschke, Crystal, Bang, & Dresner, 1988).

Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)

The abbreviated 15-item version was used to assess depressive symptoms. This version has been validated for use in the aging population (Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986; Yesavage, Brink, Rose, Lum, Huang, Adey, et al., 1982).

Statistical Analyses

Linear Mixed Effects Models

Attention network effects were examined using a linear mixed effect model. The 3-level cue and 2-level flanker served as the within subject repeated measures. Reaction time served as the dependent measure. The advantage of the linear mixed model is that the heterogeneity and correlation of repeated measures under different conditions are taken into account (Laird & Ware, 1982). The effect of cognitive fatigue was assessed with linear mixed effects models run separately for the alerting, orienting and executive attention networks. Blocks served as the three-level repeated-measures variable with attention network scores serving as the dependent measures. Analyses controlled for age, sex, education, ethnicity, global disease status, and GDS scores. A random intercept was included in the model to allow the entry point to vary across individuals. Further, it has been established that speed of processing has a robust effect on age-related differences in cognitive performance (Salthouse 1985). We controlled for speed of processing using two separate approaches. First, speed of processing (ie., average RT across all ANT trials) was used as a covariate. Second, individual differences with respect to the effect of time on speed of processing should be expected. Therefore, average reaction times based on all ANT trials were calculated for each person for the first and last blocks. Participants were then dichotomized into two subgroups using zero as the empirical cutscore (i.e., no effect of time on RT) to distinguish those whose overall RT accelerated or declined over the course of the ANT. This was done to examine the effect of cognitive fatigue on attention network performance in relation to RT trajectories.

Results

Demographics

Participants were community dwelling non-demented older adults with a mean age of 80.6(4.9) years who were relatively healthy as determined by their mean global health status of 1.1(0.93) and BIMCT average score of 1.5(1.5); see Table 1 for details). Of the 228 participants, 61 % were females and 71.5% were Caucasians. The average number of years of education was 14.5(3.2). The low levels of depressive symptoms and illness index attest to the relatively healthy nature of this sample. Mean attention network effects were consistent with previous research (Fan et al., 2002). The demographic characteristics of this sample are comparable to those reported for the source EAS sample at baseline (see Holtzer et al., 2008). The two subgroups comprising individuals whose average RT either declined or accelerated over the course of the ANT were comparable on all demographic variables, overall RT, and average attention networks performance (see Table 1). Average ANT performance accuracy was very high (97%) indicating that the participants were able to reliably determine the direction of the target stimulus.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Overall Sample (n=228) |

RT Decline (n=136) |

RT Accelerate (n=92) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | |||

| Age, y | 80.6 (4.9) | 80.6 (5.0) | 80.7 (4.8) |

| Education, y | 14.5 (3.2) | 14.2 (3.2) | 14.8 (3.2) |

| BIMCT | 1.5 (1.5) | 1.5 (1.6) | 1.3 (1.6) |

| GDS | 1.9 (2.1) | 1.9 (2.2) | 1.3 (1.6) |

| Alerting | 22.7 (39) | 21.9 (40.2) | 23.8 (37.6) |

| Orienting | 38.7 (39.5) | 38.5 (41.1) | 39.1 (37.2) |

| Executive | 119.8 (57.2) | 122.3 (59.6) | 116.2 (53.7) |

| Overall RT | 747.5 (113.4) | 743.6 (112.8) | 753.2 (114.4) |

| Medical Illness | 1.1 (.93) | 1.1 (1.0) | 1.0 (.77) |

| % (N) | |||

| Gender | |||

| Females | 61 (139) | 62.5 (85) | 58.7 (54) |

| Males | 39 (89) | 37.5 (51) | 41.3 (38) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 71.5 (163) | 66.9 (91) | 78.3 (72) |

| African American | 22.8 (52) | 26.5 (36) | 17.4 (16) |

| Other | 5.7 (13) | 6.6 (9) | 4.4 (4) |

BIMCT: Blessed information concentration and memory test; GDS: geriatric depression scale; Alerting, Orienting and Executive Attention denote overall network effects of the ANT measured in millisecond reaction time. RT denotes reaction time; RT decline denotes individuals whose overall RT across all ANT trial types declined from block 1 to block 3 of the ANT using zero as the empirical cut score; RT accelerate denotes individuals whose overall RT across all ANT trial types accelerated from block 1 to block 3 of the ANT using zero as the empirical cut score.

Independent sample t tests and Chi square analysis for continuous and categorical variables, respectively, showed that the two groups were not statistically different on any of the variables included in Table 1.

Linear mixed effects models

The first linear mixed effects model examined the main effects of alerting, orienting and executive attention. The results revealed significant effects for alerting (Beta=33.39; 95%CI.−18.37- 48.40; p<0.001) orienting (Beta=−36; 95%CI.−52.04 - −21; p<0.001) and executive attention (Beta=−126.55; 95%CI−139.12- −113.97; p<0.001).

Cognitive fatigue: Three separate linear mixed effects models examined the effect of fatigue on attention network performance (see Table 2). For executive attention, the main effect of time between blocks 1 and 2 (Beta=−106.6; 95%CI.−190-.25- −22.95; p=0.013) and the interaction of time between block 1 and 2 and speed of processing (Beta=-.156; 95%CI.04-.26; p=0.006) were statistically significant revealing decline in executive attention performance that is consistent with cognitive fatigue. The main effects and interactions of time and speed of processing were not significant for the alerting and orienting networks.

Table 2.

| Beta | t | 95%CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alerting | ||||

| Time: 1–2 | 6.64 | .175 | −68.05–81.32 | 0.861 |

| Time: 1–3 | −8.92 | −.234 | −83.97–66.12 | 0.815 |

| RT | −0.08 | −2.61 | −.15-−.02 | 0.01 |

| Time: 1–2 × RT | 0.006 | 0.13 | −.09–1.06 | 0.894 |

| Time: 1–3 × RT | 0.028 | 0.56 | −.07–.13 | 0.576 |

| Orienting | ||||

| Time: 1–2 | 29.27 | 0.77 | −45.09–103.63 | 0.44 |

| Time: 1–3 | 68.24 | 1.837 | −4.77–141.26 | 0.067 |

| RT | .027 | 0.831 | −.038–.09 | 0.407 |

| Time: 1–2 × RT | −.008 | −0.161 | −.10–.09 | 0.872 |

| Time: 1–3 × RT | −.075 | −1.533 | −.17–.02 | 0.126 |

| Executive | ||||

| Time: 1–2 | −106.60 | −2.505 | −190.25- −22.95 | 0.013 |

| Time: 1–3 | −30.39 | −0.726 | −112.67–51.88 | 0.468 |

| RT | .132 | 3.332 | .05–.21 | 0.001 |

| Time: 1–2 × RT | .156 | 2.763 | .04–.26 | 0.006 |

| Time: 1–3 × RT | .05 | 0.913 | −.05–.16 | 0.362 |

Time: 1–2 denotes time effect on attention network performance between blocks 1 and 2; Time: 1–3 decline denotes time effect on attention network performance between blocks 1 and 3; RT denotes overall speed of processing (average reaction time across all ANT trials).

All mixed linear effects models controlled for RT group status, age, education, gender, ethnicity, overall ANT reaction time, medical illness, and GDS scores.

Linear mixed effects models adjusting for RT trajectories

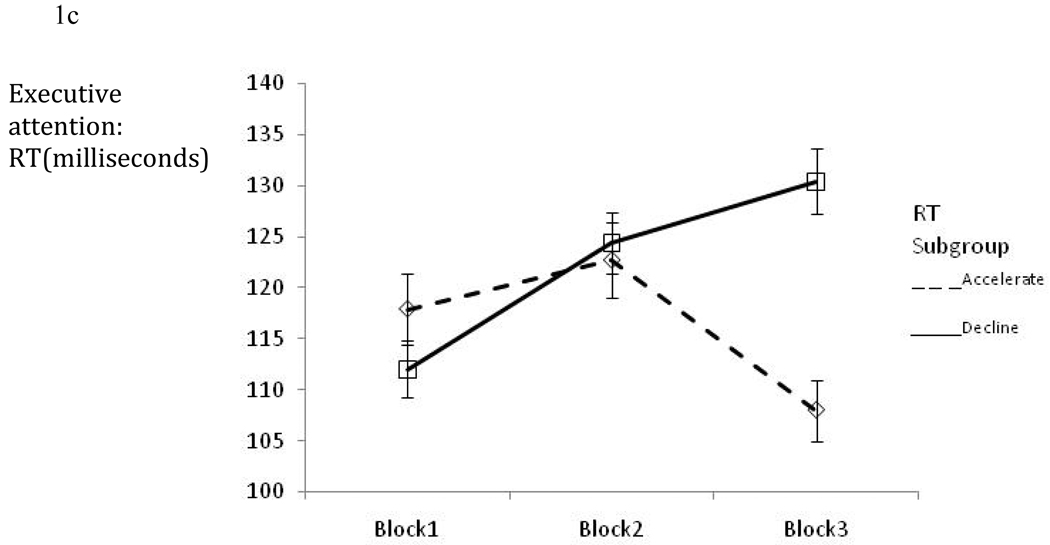

Figure 1a–c depicts alerting, orienting and executive attention effects for those participants whose overall RT either declined or accelerated over the course of the ANT. Descriptively, executive attention performance worsened in a manner consistent with cognitive fatigue for individuals whose overall RT declined over the course of the ANT. In contrast, improvement over time in attention network performance was noted for orienting with a similar but smaller trend for alerting.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a: Alerting network performance (mean ±SE) across the three ANT blocks per RT subgroup.

Figure 1b: Orienting network performance (mean ±SE) across the three ANT blocks per RT subgroup.

Figure 1c: Executive network performance (mean ±SE) across the three ANT blocks per RT subgroup.

Three linear mixed effects models controlling for RT subgroup status, age, sex, education, ethnicity, global disease status, and GDS scores examined the effect of cognitive fatigue on attention network performance in relation to RT trajectories (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary Mixed linear effects models examining cognitive fatigue separately in the alerting, orienting and executive attention networks.

| Beta | t | 95%CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alerting | ||||

| Time: 1–2 (RT decline) | 9.38 | 1.30 | −4.80 – 23.56 | 0.194 |

| Time: 1–3 (RT decline) | 9.17 | 1.27 | −4.98 – 23.33 | 0.203 |

| Time: 1–2 (RT accelerate) | 16.47 | 1.86 | −0.86 – 33.81 | 0.063 |

| Time: 1–3 (RT accelerate) | 15.37 | 1.74 | −1.93 – 32.69 | 0.082 |

| RT group | −1.70 | −0.22 | −16.76 – 13.35 | 0.824 |

| Time: 1–2 × RT group | 7.09 | 0.62 | −15.30 – 29.49 | 0.534 |

| Time: 1–3 × RT group | 6.20 | 0.54 | −16.16 – 28.56 | 0.586 |

| Orienting | ||||

| Time: 1–2 (RT decline) | 12.99 | 1.84 | −0.85 – 26.83 | 0.066 |

| Time: 1–3 (RT decline) | 24.98 | 3.47 | 10.87 – 39.10 | 0.001 |

| Time: 1–2 (RT accelerate) | 10.31 | 1.19 | −6.61 – 27.23 | 0.230 |

| Time: 1–3 (RT accelerate) | 20.66 | 2.35 | 3.40 – 37.92 | 0.019 |

| RT group | 3.02 | 0.40 | −11.64 – 17.70 | 0.685 |

| Time: 1–2 × RT group | −2.67 | −0.24 | −24.54 – 19.18 | 0.810 |

| Time: 1–3 × RT group | −4.32 | −0.38 | −26.62 – 17.97 | 0.703 |

| Executive | ||||

| Time: 1–2 (RT decline) | 12.33 | 1.52 | −3.60 – 28.27 | 0.129 |

| Time: 1–3 (RT decline) | 18.41 | 2.33 | 2.87 – 33.94 | 0.020 |

| Time: 1–2 (RT accelerate) | 5.85 | 0.59 | −13.61 – 25.35 | 0.554 |

| Time: 1–3 (RT accelerate) | −9.06 | −0.93 | −28.06 – 9.92 | 0.348 |

| RT group | 3.13 | 0.35 | −14.28 – 20.55 | 0.723 |

| Time: 1–2 × RT group | −6.47 | −0.50 | −31.64 – 18.70 | 0.614 |

| Time: 1–3 × RT group | −27.48 | −2.20 | −52.02 - −2.94 | 0.028 |

Time: 1–2 RT decline denotes time effect on attention network performance between blocks 1 and 2 for individuals whose RT declined over the course of the ANT; Time: 1–3 RT decline denotes time effect on attention network performance between blocks 1 and 3 for individuals whose RT declined over the course of the ANT; Time: 1–2 RT accelerate denotes time effect on attention network performance between blocks 1 and 2 for individuals whose RT declined over the course of the ANT; Time: 1–3 RT accelerate denotes time effect on attention network performance between blocks 1 and 3 for individuals whose RT declined over the course of the ANT; RT group denotes a two level group separating individuals whose average RT across all ANT trial types declined or accelerated between blocks 1 and 3 using 0 as the empirical cut score.

All mixed linear effects models controlled for RT group status, age, education, gender, ethnicity, medical illness, and GDS scores.

For executive attention, the interaction of time between block 1 and 3 and RT group status was significant (Beta=−27.48; 95%CI=−52.02 - −2.94; p=0.028) revealing significant decline for individuals whose average RT declined (Beta=18.41; 95%CI=2.87 – 33.94; p=0.020) but not for those whose average RT accelerated (Beta=−9.06; 95%CI=−28.06 – 9.92; p=0.348; see Table 3 and Figure 1c). The effect of time between blocks 1 and 3 on orienting was significant for individuals whose RT accelerated (Beta=24.98; 95%CI=10.87−39.10; p=0.001) or declined (Beta=20.66; 95%CI=3.40 – 37.92; p=0.019) revealing improvement in attention network performance over time (see Table 3 and Figure 1b). The main effects and interactions of time with RT subgroup status were not significant for the alerting network (see Table 3 and Figure 1a).

Discussion

The current study was designed to identify the effect of cognitive fatigue in the context of attention networks in non-demented older adults. Consistent with our hypothesis, cognitive fatigue was observed in executive attention but not in alerting or orienting. Neuroimaging studies indicate that executive control (Carter, Macdonald, Botvinick, Ross, Stenger, Noll, et al., 2000; Koechlin, Ody, & Kouneiher, 2003; Koechlin & Summerfield, 2007; MacDonald, Cohen, Stenger, & Carter, 2000) including the executive attention network of the ANT (Fan et al., 2003; Fan et al., 2005) is sub-served by prefrontal circuits, whereas alerting and orienting have been linked to other neuroanatomical substrates (Corbetta et al., 2000; Coull et al., 1996; Posner & Rothbart, 2007). Hence, this finding provides empirical support to a theoretical model implicating the frontal basal ganglia circuitry as a core substrate of cognitive fatigue (Chaudhuri & Behan, 2000, 2004). The circumscribed effect of cognitive fatigue on the executive attention network may also help refine the conceptual definition of cognitive fatigue.

We suggest that cognitive fatigue may be defined as an executive failure to monitor performance over acute but sustained cognitive effort, which results in decline and more variable performance than the individual’s optimal ability.

It is noteworthy that when adjusting for RT trajectories cognitive fatigue was observed only in individuals whose overall RT declined over the course of the ANT. This is consistent with recent evidence linking speed of processing to the frontal cortex in older adults (Kochunov et al., 2009). Conceptually, these findings can be explained in the context of the frontal lobe hypothesis of aging suggesting that functions mediated by the frontal and prefrontal cortex are among the first cognitive processes to decline with old age (Albert, 1980; Fuster, 1989; Raz, 2000; West, 1996). There is evidence of reduction in brain weight and cortical thickness in the frontal lobes by the seventh or eighth decade of life in most individuals (Haug, Knebel, Mecke, Orun, & Sass, 1981; Terry, DeTeresa, & Hansen, 1987), with the most severe reductions observed in PFC gray and white matter (Tisserand et al., 2002). The age-dependent and disproportionate atrophy in the PFC is related to cognitive performance on attention demanding tasks (Raz, 2000; Raz, Gunning-Dixon, Head, Dupuis, & Acker, 1998). Further, studies assessing functional changes in the aging brain have shown significant reductions in regional cerebral blood flow in anterior relative to posterior cortical regions (i.e., hypofrontality; Gur, Gur, Obrist, Skolnick, & Reivich, 1987; Melamed, Lavy, Bentin, Cooper, & Rinot, 1980) during attention demanding tasks (Sorond, Schnyer, Serrador, Milberg, & Lipsitz, 2008) suggesting decreased task-specific efficiency of the frontal lobes. Thus, cognitive fatigue, as observed in this study, may be explained by the negative effect of old age on the neuroanatomical substrates that subserve the executive attention network making it more vulnerable to fatigue.

For the orienting network, the effect of time was diametrically opposite to cognitive fatigue with performance improving over the course of the ANT. This finding indicates that individuals maintained and improved their ability to utilize spatial cuing in order to facilitate performance. The orienting network plays an essential role in the voluntary and involuntary selection of and shifting of attention towards the direction of an incoming stimulus (Posner & Petersen, 1990). The neuroanatomical substrates of orienting which include the superior and inferior parietal lobes, frontal eye fields, superior colliculus, pulvinar, and reticular thalamic nuclei (Corbetta et al., 2000; Mayer, Dorflinger, Rao, & Seidenberg, 2004), and its neuromodulator, acetylcholine, (Marrocco et al., 1994) are distinct from those subserving the executive attention network (for reviews see Posner & Rothbart, 2007; Raz & Buhle, 2006). Compelling evidence in support of the critical role the cholinergic system has in learning and memory exists in both animal and human studies (Gold, 2003) including recent computational models aiming to identify the interaction between attention and learning (Pauli & O'Reilly, 2008). Relevant to the improvement in orienting attention reported here is a recent investigation demonstrating that the enhancement of cholinergic function using physostigmine improved both learning and maintenance of performance whereas inhibiting cholinergic function using scopolamine caused the opposite effect on a selective attention task (Furey, Pietrini, Haxby, & Drevets, 2008). In contrast, dopaminergic circuits and function have been implicated in central fatigue in mice (Foley & Fleshner, 2008; Salamone, Correa, Farrar, Nunes, & Pardo, 2009) and in humans (Chaudhuri & Behan, 2000). Moreover, Levadopa treatment resulted in reduced levels of self-reported fatigue in patients with early stage Parkinson disease (Schifitto, Friedman, Oakes, Shulman, Comella, Marek, et al., 2008). Thus, it appears that the differential effect of time on executive attention and orienting networks, cognitive fatigue and learning respectively, has a neurobiological basis.

The findings reported in this study have important implications with respect to the assessment of cognitive fatigue. First, using tasks that maximize executive control demands will increase the likelihood of establishing reliable cognitive fatigue effects. In contrast, it appears that orienting and alerting are not likely to elicit cognitive fatigue effects, at least for approximately similar testing time as required in this experiment. The differential sensitivity of these attention networks to fatigue cannot be attributed to psychometric limitations such as floor and ceiling effects or restricted range. It is important to emphasize that sensory input and motor output were equivalent for the three networks. Further, there is equal number of trial types in each block of the ANT but the order of trials is randomly varied across individuals. Hence, measurement confounds such as trial order effects cannot account for the cognitive fatigue and learning effects observed in the executive attention and orienting networks, respectively. Second, at least in this relatively healthy sample of non-demented older adults approximately 35 minutes of testing was necessary to elicit cognitive fatigue. It remains to be evaluated whether this length of testing time is necessary for other paradigms and for individuals with cognitive impairments, dementia or other diseases that affect the central nervous system. Third, speed of processing is sensitive to fatigue. Thus, it seems imperative to use experimental paradigms that allow for separate measurement of and adjustment for speed of processing when evaluating the effect of cognitive fatigue. Also, as demonstrated in this study, it is important to determine that the effect of cognitive fatigue is not attributed to differences in cognitive ability/performance (average attention networks performance was equivalent in analyses that stratified for RT trajectories). Fourth, using multivariate models that afford statistical control over potential confounds including but not limited to relevant demographic variables, disease and health status, and levels of depressive symptoms help protect the internal validity of studies designed to assess cognitive fatigue. As reviewed earlier, perceptions of fatigue tend not to correlate with objective measures of cognitive functions (but see Holtzer & Foley, 2009). However, exploring the relationship of subjective assessment of fatigue, motivation and boredom with cognitive fatigue may be informative. Fifth, it is important to recognize that similar to other cognitive functions individual differences exist in cognitive fatigue. In this cohort approximately 60 percent of the sample showed decline in speed of processing over the course of the ANT. This may be especially relevant to neuroimaging or pharmacological studies with much smaller samples where pre-testing designed to identify those subjects who are more vulnerable to fatigue can be advantageous. Finally, these findings could have potential implications with respect to cognitive rehabilitation efforts where the optimal number and length of sessions for cognitive functions will take into account cognitive fatigue effects as well.

In summary, the present study showed that the effect of cognitive fatigue was unique to the executive attention network in healthy older adults. In contrast, improvement and a trend for improvement over time were observed in orienting and alerting, respectively. These diametrically opposite effects can be understood in light of differences in the neuroanatomical substrates underlying the aforementioned attention networks. Moreover, we suggest that cognitive fatigue may be conceptualized as an executive failure to maintain and optimize performance over acute but sustained cognitive effort resulting in performance that is lower and more variable than the individual’s optimal ability.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The Einstein Aging Study is supported by the National Institute on Aging program project grant AGO3949. Dr. Holtzer is supported by the National Institute on Aging Paul B. Beeson Award K23 AG030857.

References

- Albert M, Kaplan E. Organic implications of neuropsychological deficits in the elderly. In: Poon JLFLW, Cermark LS, Arenberg S, Thompson LW, editors. New directions in memory and aging. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1980. pp. 403–429. [Google Scholar]

- APA Presidential Task Force. American Psychological Associations' Presidential Task Force on the assessment of age-consistent memory decline and dementia. Guidelines for the evaluation of dementia and age-related cognitive decline. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avlund K, Pedersen AN, Schroll M. Functional decline from age 80 to 85: influence of preceding changes in tiredness in daily activities. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65(5):771–777. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000082640.61645.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avlund K, Rantanen T, Schroll M. Factors underlying tiredness in older adults. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;19(1):16–25. doi: 10.1007/BF03325206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avlund K, Vass M, Hendriksen C. Onset of mobility disability among community-dwelling old men and women. The role of tiredness in daily activities. Age & Ageing. 2003;32(6):579–584. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afg101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A, Channon S, Beaumont JG. The relationship between subjective fatigue and cognitive fatigue in advanced multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis. 2007;13(1):73–80. doi: 10.1177/1352458506071162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi R, Shaikh ZA, Miletich RS, Czarnecki D, Dmochowski J, Henschel K, et al. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis and its relationship to depression and neurologic disability. Multiple Sclerosis. 2000;6(3):181–185. doi: 10.1177/135245850000600308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak Y, Achiron A. Cognitive fatigue in multiple sclerosis: findings from a two-wave screening project. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2006;245(1–2):73–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Roth M. The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1968;114(512):797–811. doi: 10.1192/bjp.114.512.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant DCN, Deluca J. Objective Measurement of Cognitive Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2004;49(2):114–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Luu P, Posner MI. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2000;4(6):215–222. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, Macdonald AM, Botvinick M, Ross LL, Stenger VA, Noll D, et al. Parsing executive processes: strategic vs. evaluative functions of the anterior cingulate cortex. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science U S A. 2000;97(4):1944–1948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri A, Behan PO. Fatigue and basal ganglia. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2000;179(S 1–2):34–42. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri A, Behan PO. Fatigue in neurological disorders. Lancet. 2004;363(9413):978–988. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15794-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DB, O'Connor PJ, Lange G, Steffener J. Functional neuroimaging correlates of mental fatigue induced by cognition among chronic fatigue syndrome patients and controls. Neuroimage. 2007;36(1):108–122. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta M, Kincade JM, Ollinger JM, McAvoy MP, Shulman GL. Voluntary orienting is dissociated from target detection in human posterior parietal cortex. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3(3):292–297. doi: 10.1038/73009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull JT, Frith CD, Frackowiak RS, Grasby PM. A fronto-parietal network for rapid visual information processing: a PET study of sustained attention and working memory. Neuropsychologia. 1996;34(11):1085–1095. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(96)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craik F, Byrd M. Aging and cognitive deficits: the role of attentional resources. In: Trehub FIMCS, editor. Aging and Cognitive Processes. New York: Plenum; 1982. pp. 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- de Lange FP, Koers A, Kalkman JS, Bleijenberg G, Hagoort P, van der Meer JW, et al. Increase in prefrontal cortical volume following cognitive behavioural therapy in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 8):2172–2180. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca J. Fatigue, cognition and mental effort. In: D J, editor. Fatigue as a Window to the Brain. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 2005a. pp. 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca J. Fatigue: Its Definition, its Study and its Future. In: DeLuca J, editor. Fatigue as a Window to the Brain. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 2005b. pp. 319–325. [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca J, G H, Hillary FG, Wylie GB. Neural correlates of cognitive fatigue in multiple sclerosis using functional MRI. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2008;270:28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Fossella J, Sommer T, Wu Y, Posner MI. Mapping the genetic variation of executive attention onto brain activity. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science U S A. 2003;100(12):7406–7411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0732088100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, McCandliss BD, Fossella J, Flombaum JI, Posner MI. The activation of attentional networks. Neuroimage. 2005;26(2):471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, McCandliss BD, Sommer T, Raz A, Posner MI. Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2002;14(3):340–347. doi: 10.1162/089892902317361886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley TE, Fleshner M. Neuroplasticity of dopamine circuits after exercise: implications for central fatigue. Neuromolecular Medicine. 2008;10(2):67–80. doi: 10.1007/s12017-008-8032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossella J, Sommer T, Fan J, Wu Y, Swanson JM, Pfaff DW, et al. Assessing the molecular genetics of attention networks. BMC Neuroscience. 2002;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuld P. Psychological testing in the differential diagnosis of the dementias. In: Katzman R TR, KL Bick, editors. Alzheimer’s disease: senile dementia and related disorders. Vol. 7. New York: Raven Press; 1978. pp. 185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Furey ML, Pietrini P, Haxby JV, Drevets WC. Selective effects of cholinergic modulation on task performance during selective attention. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(4):913–923. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster JM. The prefrontal cortex. 2nd ed. New York: Raven Pres; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Gold PE. Acetylcholine modulation of neural systems involved in learning and memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2003;80(3):194–210. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold SM, Irwin MR. Depression and immunity: inflammation and depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Neurologic Clinics. 2006;24(3):507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Buschke H, Crystal H, Bang S, Dresner R. Screening for dementia by memory testing. Neurology. 1988;38(6):900–903. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.6.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RC, Gur RE, Obrist WD, Skolnick BE, Reivich M. Age and regional cerebral blood flow at rest and during cognitive activity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44(7):617–621. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800190037006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug H, Knebel G, Mecke E, Orun C, Sass NL. The aging of cortical cytoarchitectonics in the light of stereological investigations. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research. 1981;59B:193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayslip B, Jr, Kennelly KJ, Maloy RM. Fatigue, depression, and cognitive performance among aged persons. Experimental Aging Research. 1990;16(3):111–115. doi: 10.1080/07340669008251537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom Y, Hallberg IR. Determinants and characteristics of help provision for elderly people living at home and in relation to quality of life. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science. 2004;18(4):387–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzer R, Foley F. The relationship between subjective reports of fatigue and executive control in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurological Sciences. 2009;281(1–2):46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.02.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzer R, Friedman R, Lipton RB, Katz M, Xue X, Verghese J. The relationship between specific cognitive functions and falls in aging. Neuropsychology. 2007;21(5):540–548. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.21.5.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzer R, Verghese J, Wang C, Hall CB, Lipton RB. Within-person across-neuropsychological test variability and incident dementia. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(7):823–830. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.7.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzer R, Verghese J, Xue X, Lipton RB. Cognitive Processes Related to Gait Velocity: Results From the Einstein Aging Study. Neuropsychology. 2006;20(2):215–223. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.20.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochunov P, Coyle T, Lancaster J, Robin DA, Hardies J, Kochunov V, et al. Processing speed is correlated with cerebral health markers in the frontal lobes as quantified by neuroimaging. Neuroimage. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.052. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koechlin E, Ody C, Kouneiher F. The architecture of cognitive control in the human prefrontal cortex. Science. 2003;302(5648):1181–1185. doi: 10.1126/science.1088545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koechlin E, Summerfield C. An information theoretical approach to prefrontal executive function. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2007;11(6):229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad K, Neufang S, Thiel CM, Specht K, Hanisch C, Fan J, et al. Development of attentional networks: an fMRI study with children and adults. Neuroimage. 2005;28(2):429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupp LB, Elkins LE. Fatigue and declines in cognitive functioning in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2000;55(7):934–939. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38(4):963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Diane BH, Loring DW. Neuropsychological Assessment. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Liao S, Ferrell BA. Fatigue in an older population. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2000;48(4):426–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton RB, Katz MJ, Kuslansky G, Sliwinski MJ, Stewart WF, Verghese J, et al. Screening for dementia by telephone using the memory impairment screen. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2003;51(10):1382–1390. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald AW, Cohen JD, Stenger VA, Carter CS. Dissociating the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex in cognitive control. Science. 2000;288(5472):1835–1838. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney JR, Verghese J, Goldin Y, Lipton R, Holtzer R. Alerting, orienting and executive attention in non-demented older adults. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2010;27:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710000767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrocco RT, Witte EA, Davidson MC. Arousal systems. Current Opinions in Neurobiology. 1994;4(2):166–170. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer AR, Dorflinger JM, Rao SM, Seidenberg M. Neural networks underlying endogenous and exogenous visual-spatial orienting. Neuroimage. 2004;23(2):534–541. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowd JM, Shaw RJ. Attention and aging: A functional perspective. In: Craik FIM, Salthouse TA, editors. The handbook of aging and cognition. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2000. pp. 221–292. [Google Scholar]

- Melamed E, Lavy S, Bentin S, Cooper G, Rinot Y. Reduction in regional cerebral blood flow during normal aging in man. Stroke. 1980;11(1):31–35. doi: 10.1161/01.str.11.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton LS, Denney DR, Lynch SG, Parmenter B. The relationship between perceived and objective cognitive functioning in multiple sclerosis. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2006;21(5):487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrushina M, Boone KB, Razani J, D’Elia L. Handbook of normative data for neuropsychological assessment. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex "Frontal Lobe" tasks: a latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology. 2000;41(1):49–100. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niepel G, Tench Ch R, Morgan PS, Evangelou N, Auer DP, Constantinescu CS. Deep gray matter and fatigue in MS: a T1 relaxation time study. Journal of Neurology. 2006;253(7):896–902. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmenter BA, Denney DR, Lynch SG. The cognitive performance of patients with multiple sclerosis during periods of high and low fatigue. Multiple Sclerosis. 2003;9(2):111–118. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms859oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashler HE. The psychology of attention. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 1998. p. 494. The psychology of attention xiv. [Google Scholar]

- Pauli WM, O'Reilly RC. Attentional control of associative learning--a possible role of the central cholinergic system. Brain Research. 2008;1202:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittion-Vouyovitch S, Debouverie M, Guillemin F, Vandenberghe N, Anxionnat R, Vespignani H. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis is related to disability, depression and quality of life. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2006;243(1–2):39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Petersen SE. The attention system of the human brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1990;13:25–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Rothbart MK. Research on attention networks as a model for the integration of psychological science. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasova K, Brandejsky P, Havrdova E, Zalisova M, Rexova P. Spiroergometric and spirometric parameters in patients with multiple sclerosis: are there any links between these parameters and fatigue, depression, neurological impairment, disability, handicap and quality of life in multiple sclerosis? Multiple Sclerosis. 2005;11(2):213–221. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1155oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz A, Buhle J. Typologies of attentional networks. Nature Review Neuroscience. 2006;7(5):367–379. doi: 10.1038/nrn1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz N. Aging of the brain and its impact on cognitive performance: Integration of structural and functional findings. In: Craik FIM, Salthouse TA, editors. The handbook of aging and cognition. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2000. pp. 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- Raz N, Gunning-Dixon FM, Head D, Dupuis JH, Acker JD. Neuroanatomical correlates of cognitive aging: evidence from structural magnetic resonance imaging. Neuropsychology. 1998;12(1):95–114. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Gibby CC, Mendoza TR, Wang S, Anderson KO, Cleeland CS. Pain and fatigue in community-dwelling adults. Pain Medicine. 2003;4(3):231–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelcke U, Kappos L, Lechner-Scott J, Brunnschweiler H, Huber S, Ammann W, et al. Reduced glucose metabolism in the frontal cortex and basal ganglia of multiple sclerosis patients with fatigue: a 18F–fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography study. Neurology. 1997;48(6):1566–1571. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.6.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamone JD, Correa M, Farrar AM, Nunes EJ, Pardo M. Dopamine, behavioral economics, and effort. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009;3:13. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.013.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Speed of behavior and its implication for cognition. In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, editors. Handbook of the Psychology of Aging. 2nd ed. North-Holland: Amsterdam; 1985. pp. 400–426. [Google Scholar]

- Schifitto G, Friedman JH, Oakes D, Shulman L, Comella CL, Marek K, et al. Fatigue in levodopa-naive subjects with Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;71(7):481–485. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000324862.29733.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz-Larsen K, Avlund K. Tiredness in daily activities: a subjective measure for the identification of frailty among non-disabled community-living older adults. Archives of Gerontology & Geriatrics. 2007;44(1):83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwid SR, Tyler CM, Scheid EA, Weinstein A, Goodman AD, McDermott MP. Cognitive fatigue during a test requiring sustained attention: a pilot study. Multiple Sclerosis. 2003;9(5):503–508. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms946oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontologist. 1986;5(1–2):165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Skerrett TN, Moss-Morris R. Fatigue and social impairment in multiple sclerosis: the role of patients' cognitive and behavioral responses to their symptoms.[see comment] Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;61(5):587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorond FA, Schnyer DM, Serrador JM, Milberg WP, Lipsitz LA. Cerebral blood flow regulation during cognitive tasks: effects of healthy aging. Cortex. 2008;44(2):179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellez N, Alonso J, Rio J, Tintore M, Nos C, Montalban X, et al. The basal ganglia: a substrate for fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Neuroradiology. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s00234-007-0304-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry RD, DeTeresa R, Hansen LA. Neocortical cell counts in normal human adult aging. Ann Neurol. 1987;21(6):530–539. doi: 10.1002/ana.410210603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisserand DJ, Pruessner JC, Sanz Arigita EJ, van Boxtel MP, Evans AC, Jolles J, et al. Regional frontal cortical volumes decrease differentially in aging: an MRI study to compare volumetric approaches and voxel-based morphometry. Neuroimage. 2002;17(2):657–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Werf SP, Jongen PJ, Lycklama a Nijeholt GJ, Barkhof F, Hommes OR, Bleijenberg G. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: interrelations between fatigue complaints, cerebral MRI abnormalities and neurological disability. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 1998;160(2):164–170. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese J, Katz MJ, Derby CA, Kuslansky G, Hall CB, Lipton RB. Reliability and validity of a telephone-based mobility assessment questionnaire. Age & Ageing. 2004;33(6):628–632. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese J, Lipton RB, Hall CB, Kuslansky G, Katz MJ, Buschke H. Abnormality of gait as a predictor of non-Alzheimer's dementia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(22):1761–1768. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese J, Wang C, Lipton RB, Holtzer R, Xue X. Quantitative gait dysfunction and risk of cognitive decline and dementia. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2007;78(9):929–935. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.106914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P, Cerella J. Aging, executive control, and attention: a review of meta-analyses. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Review. 2002;26(7):849–857. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P, Steitz DW, Sliwinski MJ, Cerella J. Aging and dual-task performance: a meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18(3):443–460. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. WAIS-IV: Administration and scoring manual. San Antonia, TX: Pearson; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- West RL. An application of prefrontal cortex function theory to cognitive aging. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;120(2):272–292. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijeratne C, Hickie I, Brodaty H. The characteristics of fatigue in an older primary care sample. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2007;62(2):153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1982;17(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]