Abstract

Calreticulin is a soluble calcium-binding chaperone of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that is also detected on the cell surface and in the cytosol. Calreticulin contains a single high affinity calcium-binding site within a globular domain and multiple low affinity sites within a C-terminal acidic region. We show that the secondary structure of calreticulin is remarkably thermostable at a given calcium concentration. Rather than corresponding to complete unfolding events, heat-induced structural transitions observed for calreticulin relate to tertiary structural changes that expose hydrophobic residues and reduce protein rigidity. The thermostability and the overall secondary structure content of calreticulin are impacted by the divalent cation environment, with the ER range of calcium concentrations enhancing stability, and calcium-depleting or high calcium environments reducing stability. Furthermore, magnesium competes with calcium for binding to calreticulin and reduces thermostability. The acidic domain of calreticulin is an important mediator of calcium-dependent changes in secondary structure content and thermostability. Together, these studies indicate interactions between the globular and acidic domains of calreticulin that are impacted by divalent cations. These interactions influence the structure and stability of calreticulin, and are likely to determine the multiple functional activities of calreticulin in different subcellular environments.

Keywords: Chaperone Chaperonin, Circular Dichroism (CD), Protein Folding, Protein Stability, Protein Structure, Calnexin, Calreticulin, Isothermal Titration Calorimetry, Protein Aggregation

Introduction

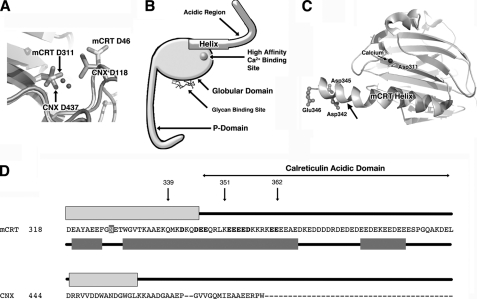

Calreticulin (CRT)2 and calnexin are structurally related lectin-binding chaperones that aid in the folding of glycoproteins via binding to oligosaccharide components of substrate proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (1, 2). Calreticulin is a soluble protein, whereas its homologue calnexin is membrane-linked at its C terminus. The crystal structure of soluble calnexin revealed the presence of a globular domain, composed primarily of β-strands, containing the predicted glycan and calcium-binding sites of the protein (3). The recently reported crystal structures of the globular domain of calreticulin (PDB codes 3O0V, 3O0W, and 3O0X) have revealed a high degree of conservation with calnexin in the overall structure and in the residues corresponding to the high affinity calcium (Fig. 1A) and glycan-binding sites (4). Calnexin and calreticulin also contain a proline-rich domain, the P-domain (Fig. 1B), which forms a hook-like arm comprising a β-stranded hairpin, the tip of which contains the binding site for the partner oxidoreductase ERp57 (3, 5, 6). In calreticulin, the presence of a high affinity calcium-binding site within the P-domain has been suggested based on biochemical studies of 45Ca2+ binding to calreticulin truncation constructs (1, 7). However, based on crystallographic studies of calreticulin and calnexin, Asp311 and other residues within the globular domain of calreticulin are predicted to be involved in high affinity calcium binding (3, 4) (Fig. 1, A and C). Calreticulin also has an acidic C-terminal domain within the ER lumen (Fig. 1B), a region not conserved in the luminal domain of calnexin (Fig. 1D). This domain contains low affinity, high-capacity calcium-binding sites (1, 7, 8) that function in calcium storage and contribute to the maintenance of calcium homeostasis in the ER (9–11). In turn, ER calcium concentrations impact protein secretion (12), and numerous cellular functions (13–15). Currently, there is very little structural information available concerning the modes of calcium binding by the acidic domain, and it remains unclear whether the acidic domain is folded independently of the globular domain. Recent biophysical studies of the isolated acidic domain and its segments have suggested that the N-terminal portion adopts an α-helical conformation independent of calcium binding, whereas the C-terminal region acquires a weak β-strand-like secondary structure in a calcium-dependent manner (16).

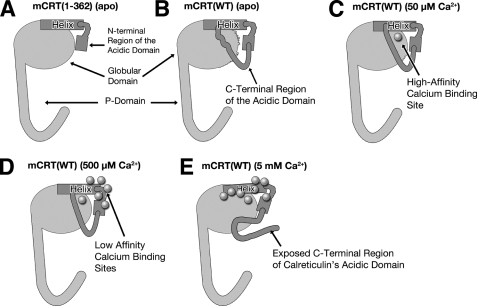

FIGURE 1.

Structural features of calreticulin and calnexin. A, superimposition of the globular domains of calnexin (PDB code 1JHN) (3) and calreticulin (PDB code 3O0V) (4) comparing the putative high affinity calcium-binding sites of the two proteins (shown as sticks). Calcium ions from the two crystal structures are shown as spheres. B, schematic of calreticulin showing the locations of the glycan and high affinity calcium-binding sites of calreticulin. The globular, P-, and acidic domains of calreticulin are also shown. The long helix of calreticulin, which precedes the acidic domain, is indicated. C, structure of the globular domain of calreticulin (PDB code 3O0V (4); corresponding to mCRT residues 1–351, excluding the P-domain). The long C-terminal helix of calreticulin is indicated. An arrow denotes the location of residue 339, which truncates seven C-terminal residues of the visible helix. The mCRT(1–351) construct includes the entire visible helix and five C-terminal unstructured residues. Asp311, which is a component of the high affinity binding site of calreticulin, is labeled. The calcium atom bound to the high affinity site is indicated and rendered as a black sphere. Asp342, Asp345, and Glu346, which could contribute to the low affinity calcium-binding sites of mCRT(1–351) are labeled. Glu347, which could additionally contribute to low affinity calcium binding in mCRT(1–351), was not visible in the crystal structure of the globular domain of calreticulin (PDB code 3O0V) (4). The image was produced using PyMOL (DeLano Scientific, Palo Alto, CA). D, sequence alignment (with observed and predicted secondary structures) of calreticulin residues 318–399 (corresponding to the long C-terminal helix in the globular domain of calreticulin along with its acidic regions), and the C-terminal sequence of the luminal region of canine calnexin (CNX) (residues 444–483). The observed secondary structure content from the crystal structures of the globular domain of calreticulin (PDB code 3O0V) (4) and the luminal domain of calnexin (PDB code 1JHN) (3) are shown above the corresponding sequences in light gray. The predicted secondary structure content for calreticulin is shown below the sequence in dark gray. Secondary structure predictions were obtained using PSIPRED (28), with sequence alignments obtained using Clustal W2 (29). α-Helices are rendered as rectangles. Numbered arrows indicate the location of residues 339, 351, and 362 in the calreticulin sequence, which correspond to the C-terminal truncation mutants characterized in this study. Asn327, the putative glycosylation site of calreticulin, which remains non-glycosylated in murine fibroblasts unless exposed to calcium-depleting conditions, is shaded with a gray background. Asp342, Asp345, Glu346, and Glu347, which could contribute to low affinity calcium binding by mCRT(1–351) and mCRT(1–362), and Glu352, Glu353, Glu354, Glu355, Asp356, Glu361, and Glu362, which could additionally contribute to low affinity calcium binding by mCRT(1–362), are indicated in bold.

Although calreticulin is predominantly localized in the ER, several studies describe the cell surface and cytosolic expression of calreticulin (reviewed in Ref. 17). Compared with the ER, the cytosol is a calcium-depleted environment, whereas extracellular calcium concentrations, typically in the millimolar range, are significantly higher than those in the ER. Thus, calreticulin must have the intrinsic ability to fold and function in highly variable calcium environments.

Calcium binding is known to impact the protein recognition features of both calnexin and calreticulin (18–22). Previous studies have indicated that calcium binding impacts the conformational properties of calreticulin, inducing increased resistance to protease digestion (23), chemical and thermal denaturation (24), and enhancing protein rigidity as assessed by near-UV circular dichroism analyses (25). However, it is not well understood whether occupancy of the high affinity site alone or both calcium-binding sites is required to induce such changes.

Here we investigated the nature of the calcium-binding sites of calreticulin as well as structural changes that are associated with calcium binding to the high and low affinity sites. Calcium binding to calreticulin was analyzed using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), and calcium-induced changes in the secondary and tertiary structures of calreticulin were studied using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). In comparison to previous far-UV CD studies that have been undertaken with calreticulin (23, 26), we present far-UV CD data on calreticulin undertaken over a wider spectrum as well as thermodynamic data on the binding of calcium to the high and low affinity calcium-binding sites of calreticulin. We undertook these biophysical measurements with wild type calreticulin as well as calreticulin constructs that lack all or part of the acidic C-terminal domain (Fig. 1D). These studies revealed novel aspects of the structural features of calreticulin and evidence for calcium-dependent interactions between the globular and acidic domains of calreticulin.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Supplies

Unless indicated, all reagents were purchased from Sigma. Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin was purchased from Invitrogen.

Calreticulin Mutants

Construction of N-terminal histidine-tagged murine calreticulin (mCRT(WT)) (residues 1–399), a truncation mutant lacking the entire acidic domain (mCRT(1–339)), a truncation mutant including the N-terminal region of the acidic domain (mCRT(1–362)), and a truncation mutant lacking the P-domain (a full-length construct lacking residues 187–283; mCRT(ΔP)), were described previously (27). Other mCRT constructs described here were generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) using the protocol specified by the manufacturer and mCRT in the pMCSG7 vector. The following primers were used: mCRT(1–351) construct: forward, 5′-GAG GAG CAG AGG CTT AAG TAA GAA GAA GAG GAC AAG-3′; reverse, 5′-CTT GTC CTC TTC TTC TTA CTT AAG CCT CTG CTC CTC-3′. mCRT(S391W) mutant: forward, 5′-GAG AAG GAG GAA GAT GAG GAA GAA TGG CCT GGC CAA GCC AAG GAT GAG CTG-3′; reverse, 5′-CAG CTC ATC CTT GGC TTG GCC AGG CCA TTC TTC CTC ATC TTC CTC CTT CTC-3′. mCRT(A395W) mutant: forward, 5′-GAG AAG GAG GAA GAT GAG GAA GAA TCC CCT GGC CAA TGG AAG GAT GAG CTG-3′; reverse, 5′-CAG CTC ATC CTT CCA TTG GCC AGG GGA TTC TTC CTC ATC TTC CTC CTT CTC-3′. mCRT(D311A) mutant: forward, 5′-GTC AAG TCC GGG ACA ATC TTT GCC AAT TTC CTC ATC ACC AAT GAT GAG-3′; reverse, 5′-CTC ATC ATT GGT GAT GAG GAA ATT GGC AAA GAT TGT CCC GGA CTT GAC-3′. Following mutagenesis, DNA constructs were verified by sequencing at the University of Michigan Sequencing Core prior to being transformed into competent Escherichia coli (BL21 strain).

Protein Purification

All calreticulin constructs were purified by nickel affinity chromatography as described previously (27). The eluted proteins were dialyzed overnight with 0.5 mg of TEV protease against 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 5 mm CaCl2, and 10 mm NaCl at 4 °C. Following TEV cleavage of the N-terminal His6 tag, calreticulin was purified to homogeneity via size exclusion chromatography at 4 °C using a Superdex-200 column (Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 5 mm CaCl2, and 10 mm NaCl at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Fractions containing the calreticulin monomer were pooled and concentrated to 4 mg/ml using an Amicon Ultra concentrator with a 10,000 Da molecular mass cut-off (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The apo forms of calreticulin were made via the addition of 5 mm EDTA to the respective proteins followed by three rounds of dialysis in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) and 10 mm NaCl to ensure complete removal of any residual calcium and EDTA. All calreticulin constructs described here contained a Ser-Asn-Ala tripeptide sequence prior to the start of the calreticulin sequence.

Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy

Near (340–250 nm) and far (260–195 nm) UV CD spectroscopy was undertaken using a Jasco J-715 or an Aviv model 62DS spectropolarimeter. Far-UV spectra of calreticulin in the range of 260–195 nm were measured at a [CRT] = 0.1 mg/ml in 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.5) and 500 mm NaF with the addition of 50, 500, or 5 mm CaCO3 as needed. These buffer conditions were used because HEPES and chloride ions exhibit strong CD signals in the far-UV region. The following instrument settings were used: 0.1-mm path length, 5-nm bandwidth, and 1-nm data pitch. 10 spectra (run at a rate of 50 nm/min) were averaged over the measured range of wavelengths at temperatures ranging from 20 to 60 °C. No changes in pH were observed over the temperature range from 20 to 60 °C, with the indicated buffer (50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 0.5 m NaF, and 500 μm CaCO3). The far-UV spectrum scans reported in this article represent the average of at least two independent repetitions. Far-UV temperature scans of calreticulin were undertaken with a [CRT] = 0.1 mg/ml in 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.5) and 500 mm NaF with the addition of 500 μm CaCO3 as needed. The CD signal around 222 nm was measured from 20 −90 °C with the temperature increasing at a rate of 40 °C/h.

Near-UV wavelength and temperature scans of calreticulin were undertaken at a [CRT] = 2 mg/ml in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) and 10 mm NaCl with the addition of 50 μm, 500 μm, or 5 mm CaCl2 alone or with 1 mm MgCl2 as specified, and using the following settings: 0.1-mm path length, 5-nm bandwidth, and 1-nm data pitch. Temperature scans were measured from 20 to 60 °C at 280 nm with the temperature increasing at a rate of 40 °C/h. Variable temperature scans in the near- and far-UV regions represent the average of at least two repetitions.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

ITC measurements (at 37 °C) with the various mCRT constructs were undertaken using a Nano-ITC (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE). ITC runs were performed with calreticulin at a concentration of 100 μm in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) and 10 mm NaCl in a total volume of 1.5 ml. For the high affinity site, 10-μl injections of a 250 or 500 μm stock CaCl2 solution in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) and 10 mm NaCl were titrated into the protein sample and the change in was enthalpy measured and analyzed using NanoAnalyze (version 2.0.1) (TA Instruments). For the low affinity site measurements, binding to the high affinity site was blocked by preincubating calreticulin with 50 μm stock CaCl2. 10 μl injections of a 5 mm stock CaCl2 solution in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) and 10 mm NaCl were then titrated into the protein sample and the change in enthalpy was measured. Twenty-five total injections were performed for both sets of binding measurements. Binding of CaCl2 to calreticulin in the presence of Mg2+ was similarly assessed by performing calcium injections as described above, but including 1 mm MgCl2 prior to the indicated CaCl2 injections. Each ITC experiment was repeated at least twice and the average thermodynamic and affinity values are reported.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

Measurements of the temperature-induced enthalpy changes in calreticulin were assessed via DSC using a N-DSC II (Calorimetry Sciences Corp.). DSC scans of the various calreticulin constructs were undertaken from 20 to 120 °C in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mm NaCl, and the indicated CaCl2 concentrations with a [CRT] = 1 mg/ml. Baseline runs were performed with buffer alone. The data were processed in CpCalc (Calorimetry Sciences Corp.) and the baseline-subtracted scans were analyzed in Graphpad Prism (version 5.0). Each DSC scan was repeated at least three times and the average transition temperature (TTrans) is reported.

Fluorescence Measurements

Fluorescence measurements of mCRT(WT), mCRT(S391W), and mCRT(A395W) were undertaken using a FluoroMax-3 spectrofluorometer (Horiba Scientific) with calreticulin at a concentration of 1 mg/ml in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) and 10 mm NaCl with the addition of 50 μm, 500 μm, or 5 mm CaCl2 as needed. Tryptophan emission spectra were measured from 290 to 390 nm following excitation at 280 nm. Each fluorescence experiment was repeated at least twice.

Bioinformatics

Secondary structure predictions for the C terminus of the globular domain of calreticulin together with its acidic domain were obtained using the PSIPRED server (28). Sequence alignments were obtained using ClustalW2 (29).

Data Analyses and Statistics

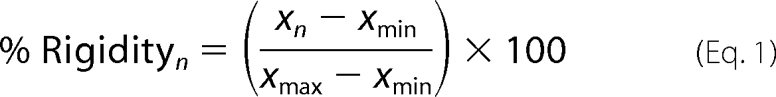

Data for the near-UV temperature scans of full-length calreticulin and other calreticulin constructs under differing calcium conditions were normalized via conversion to % rigidity. % Rigidity at a temperature point n, with an absolute CD value of xn was defined as follows (xmin and xmax represent the highest and lowest absolute CD values in the dataset).

|

The resulting data were plotted as % rigidity versus temperature and analyzed via non-linear regression using Richard's five-parameter dose-response curve to obtain values for the temperatures at which calreticulin lost 50% of its rigidity (denoted as TR50). Fluorescence spectra were normalized such that the emission maximum of a calreticulin construct at 50 μm CaCl2 was set at 1.0 and measurements at other [CaCl2] within a construct are reported relative to its spectrum at 50 μm CaCl2.

All statistical analyses were undertaken using Graphpad Prism (version 5.0). Differences in TTrans values for the calreticulin constructs at various calcium concentrations were assessed for significance using paired t tests. Two-tailed unpaired t tests were used to assess differences in TR50 values.

RESULTS

Physiological Variations of ER Calcium (50 μm to 500 μm) Correspond, Respectively, to Significant Occupancy of Just the High Affinity Site Located within the Globular Domain, or of Additional Occupancies of C-terminal Low Affinity Sites

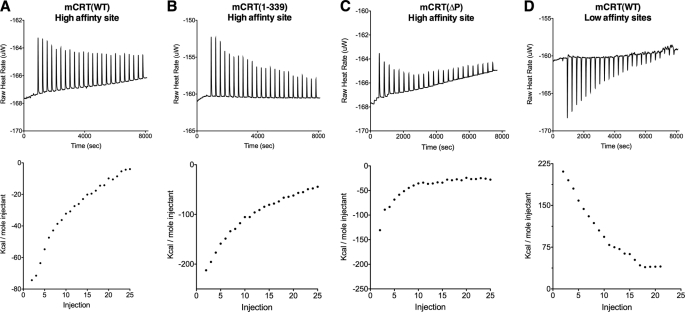

Using ITC (Fig. 2), we measured high affinity calcium binding to wild type murine calreticulin mCRT(WT), as well as to truncated constructs lacking the acidic or P-domains (mCRT(1–339) and mCRT(ΔP), respectively) (27) (Fig. 1). With mCRT(WT), sequential injection of 3.3 μm CaCl2 to the apoprotein allowed for a binding event to be visualized with a KD value corresponding to 16.6 ± 2.0 μm (Fig. 2A and Table 1). Similar analyses with mCRT(1–339) and mCRT(ΔP) yielded KD values of 13.6 ± 1.3 and 22.6 ± 0.5 μm, respectively (Fig. 2, B and C, and Table 1), confirming that the binding event being measured with mCRT(WT) (Fig. 2A and Table 1) indeed corresponds to the occupancy of a high affinity site that is not located in the acidic C terminus of calreticulin or its P-domain. Furthermore, mCRT(D311A) displayed an inability to bind calcium at the high affinity site (Table 1), a finding consistent with the calcium-binding site identified from the crystal structures of the calreticulin globular domain (PDB codes 3O0V, 3O0W, and 3O0X) and of soluble calnexin (PDB code 1JHN) (3, 4) (Fig. 1A). Under resting conditions where [Ca2+]ER is estimated in the range of 500 μm, and under conditions of agonist-induced depletion of ER calcium stores, where [Ca2+]ER levels are expected to transiently decrease to ∼50 μm (reviewed in Refs. 30–32), the high affinity calcium-binding site of calreticulin is expected to be significantly occupied. In the cytosol, where the calcium concentration is expected to be in the nanomolar range under resting conditions, the high affinity site is expected to be largely unoccupied.

FIGURE 2.

Calreticulin has high and low affinity calcium-binding sites within the globular and acidic domains. Isothermal titration calorimetry at 37 °C of calcium binding to the high affinity sites of apo-mCRT(WT) (A), apo-mCRT(1–339) (B), and apo-mCRT(ΔP) (C) by sequential injections of 3.3 or 1.7 μm CaCl2. D, isothermal titration calorimetry at 37 °C of calcium binding to the low affinity sites of mCRT(WT) using a starting calcium concentration of 50 μm (to saturate the high affinity site) followed by sequential injections of 33 μm CaCl2. The figure shows representative raw titration curves (above) and the corresponding curve fit (below). The calculated thermodynamic parameters for at least two replicates of each analyzed construct are reported in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Measurement of calcium binding to the high and low affinity calcium-binding sites of mCRT via isothermal titration calorimetry

Isothermal calorimetric binding data at 310.15 K (37 °C) for the calcium-binding sites for calreticulin.

| Calcium binding site/mCRT construct | Starting [CaCl2] | [CaCl2] per injection | Calorimetric dataa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K | ΔH | n | KD | |||

| μm | mol−1 | kJ/mol | mol | μm | ||

| High affinity site/mCRT(WT) | 0 | 3.3 | 61236.4 ± 7494.3 | −53.9 ± 12.2 | 0.8 ± 0.45 | 16.6 ± 2.0 |

| High affinity site/mCRT(1–339) | 0 | 1.7 and 3.3 | 74101 ± 6962.9 | −109.2 ± 25.2 | 0.45 ± 0.25 | 13.6 ± 1.3 |

| High affinity site/mCRT(ΔP) | 0 | 1.7 | 44251.99 ± 901.7 | −84.15 ± 34.6 | 0.48 ± 0.23 | 22.6 ± 0.5 |

| High affinity site/mCRT(D311A) | 0 | 3.3 | NDb | ND | ND | ND |

| High affinity site/mCRT(1–339) + 1 mm MgCl2 | 0 | 1.7 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| High capacity, low affinity sites/mCRT(WT) | 50 | 33 | 1786.5 ± 312.7 | 9.8 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 590.6 ± 88.0 |

| High capacity, low affinity sites/mCRT(1–339) | 50 | 33 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| High capacity, low affinity sites/mCRT(D311A) | 50 | 33 | 2319.2 ± 273.7 | 10.8 ± 3.0 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 437.3 ± 51.6 |

| High capacity, low affinity sites/mCRT(1–351) | 50 | 33 | 1514.8 ± 65.3 | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 0.03 | 661.4 ± 28.5 |

| High capacity, low affinity sites/mCRT(1–362) | 50 | 33 | 1976.5 ± 90.8 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 5.9 ± 1.1 | 507.0 ± 23.3 |

| High capacity, low affinity sites/mCRT(WT) + 1 mm MgCl2 | 50 | 33 | 166.7 ± 5.1 | 86.8 ± 4.9 | 1.04 ± 0.06 | 6003.6 ± 184.5 |

a Data represent mean ± S.E. for at least two replicates.

b ND, no detectable binding.

To measure the thermodynamics of calcium binding to the low affinity sites of calreticulin in the context of mCRT(WT), its high affinity site was initially saturated with a calcium concentration of 50 μm CaCl2 (corresponding to ∼80% occupancy), followed by sequential injections of 33 μm CaCl2. This allowed for an estimate of a KD value of 590.6 ± 88.0 μm for the low affinity, high capacity sites of mCRT(WT) (Fig. 2D and Table 1) with a stoichiometry of 3.8 ± 0.5 mol of calcium/mol of calreticulin. No further binding events were observed in mCRT(WT) when going from 0.5 to 4.6 mm CaCl2 (data not shown). Repeating the low affinity site measurements in the context of mCRT(1–339) revealed the absence of low affinity calcium-binding sites (Table 1), thereby verifying that the enthalpy-driven low affinity sites localize C-terminal to residue 339.

Previous data based on 45Ca2+ binding to calreticulin had suggested the stoichiometry of binding to be ∼17–18 mol/calcium/mol of calreticulin (7). The differences in stoichiometries reported here and previously published data could be accounted for by differences in techniques used. Because ITC measures changes in enthalpy associated with ligand binding, it is possible that the binding of additional Ca2+ could be entropically (rather than enthalpically) driven. It is also possible that additional low affinity binding sites are masked by the heat of dilution of the ligand (CaCl2) into the protein solution.

The design of mCRT(1–339) was based upon sequence alignments with calnexin (Fig. 1D). Although the globular domains of calreticulin and the luminal domain of calnexin are remarkably similar from a structural standpoint, differences exist with respect to the length of the C-terminal helices in their globular domains. The crystal structure of the luminal domain of calnexin (PDB code 1JHN) (3) showed its C-terminal helix globular domain to be relatively short (13 residues), whereas the crystal structure of the globular domain of calreticulin (PDB ID 3O0V) (4) revealed 29 visible residues to be present in its C-terminal helix (Fig. 1D). Thus, we also generated and characterized another calreticulin construct (mCRT(1–351)) containing the entire C-terminal helix as visualized in its globular domain structure, along with five additional C-terminal residues. The mCRT(1–351) truncation was designed based on the report of a natural proteolytic cleavage at residue 351 of murine calreticulin, and the same C-terminal truncation was used to solve the crystal structure of the globular domain of calreticulin (4).

Secondary structure prediction undertaken using PSIPRED (28) suggested that the C-terminal helix in the globular domain of calreticulin might be even longer than that seen in the globular domain structure, extending to residue 366 (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, previous research has suggested that a peptide corresponding to the C terminus of the globular domain of calreticulin, together with 20 N-terminal residues of its acidic domain (residues 341–366; KDKCDEEQRLKEEEEEKK-RKEEEEAE), adopts an α-helical structure independent of calcium binding (16). To better understand how the N terminus of the acidic domain might contribute to calcium binding and structural stability, we additionally used mCRT(1–362), a previously described construct (27), in the present studies.

Somewhat surprisingly, binding of calcium to low affinity sites was measurable in the contexts of both mCRT(1–351) and mCRT(1–362), with KD values of 661.4 ± 28.5 and 507.0 ± 23.3 μm, respectively (Table 1). Estimated binding stoichiometries were 5.9 ± 1.1 and 2.1 ± 0.03 mol of calcium/mol of calreticulin for mCRT(1–362) and mCRT(1–351), respectively. The binding stoichiometry derived for mCRT(1–362) was slightly higher than that for mCRT(WT) (3.8 ± 0.5 mol), suggesting that the N-terminal region of the acidic domain is sufficient to account for the enthalpically driven calcium binding to low affinity sites present within the full-length protein. However, taking into consideration the fact that ITC measures enthalpically driven ligand binding, together with the possible masking of additional low affinity sites through heat of dilution effects, it is possible that additional low affinity calcium-binding sites exist in the acidic domain that are not detectable by ITC.

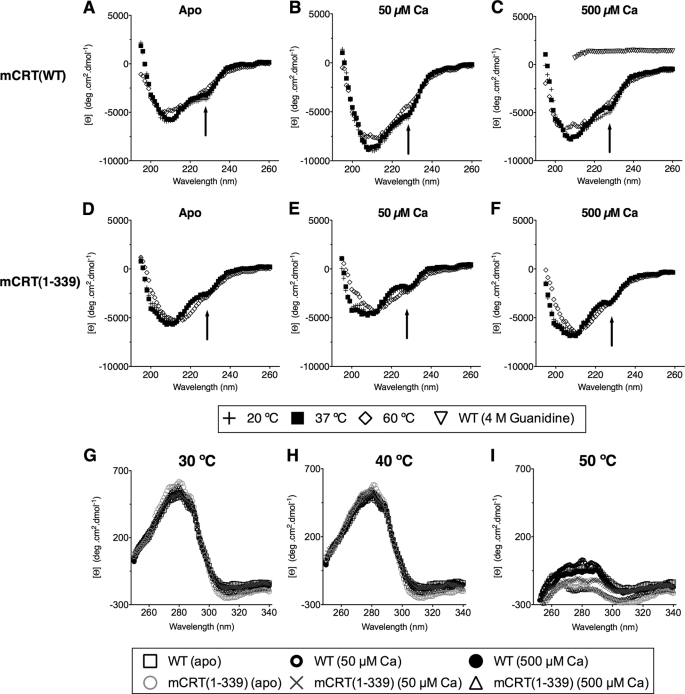

Secondary Structure of Calreticulin Is Heat Stable to 60 °C

To obtain initial biophysical insights into heat-induced structural transitions in calreticulin, mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–339) were used as constructs containing both the high and low affinity sites or just the high affinity site, respectively. Analyses of the far-UV spectrum scans of mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–339) revealed that the secondary structure of calreticulin is remarkably heat stable to temperatures of at least 60 °C (Fig. 3, A–F). This heat stability was present with calcium-bound protein (50 and 500 μm CaCO3) as well as with the apoprotein. Heat stability was observed with wild-type protein (Fig. 3, A–C) as well as with mCRT(1–339) (Fig. 3, D–F).

FIGURE 3.

At any given concentration of calcium, the secondary structure composition of calreticulin shows little variation to 60 °C. Far-UV CD spectra for mCRT(WT) (A–C) or mCRT(1–339) (D–F) under apo, 50 μm or 500 μm CaCO3 conditions. Also shown for contrast (in panel C) is the far-UV CD spectrum (measured from 260 to 210 nm) of mCRT(WT) denatured with 4 m guanidine HCl. An arrow denotes the shoulder seen at 228 nm. G–I, overlay of near-UV CD spectra of mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–339) in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) and 10 mm NaCl buffer containing 0, 50 μm, or 500 μm CaCl2 as indicated at 30 (G), 40 (H), and 50 °C (I). Unlike its secondary structure composition, which is invariant at a given calcium concentration, mCRT looses structural rigidity upon heating from 40 to 50 °C (panels H and I). Data were collected using a Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter and represent the average of 2 independent sets of scans.

However, some structural changes were noted following heat treatments. In particular, a shoulder was observed in the far-UV CD spectrum of calreticulin at 228 nm (20 or 37 °C; denoted by arrows in Fig. 3, A–F), likely arising from the contribution of aromatic residues such as tryptophan (33), which are highly abundant in the globular domains of mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–339) (both of which contains 11 tryptophan residues). The intensity of the shoulder is decreased upon heating the proteins to 60 °C, suggesting a temperature-induced loss of tryptophan rigidity and an increase in the overall flexibility of the calreticulin molecule. On the other hand, significant secondary structure was maintained at increased temperatures under all conditions tested and at temperatures up to 90 °C (data not shown). In contrast, complete loss of the secondary structure could be visualized by protein denaturation in 4 m guanidine hydrochloride (Fig. 3C).

Tertiary Structural Rigidity of Calreticulin Is Heat Labile

Although the secondary structure of calreticulin is heat stable to 60 °C, near-UV CD analysis of full-length mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–339) revealed a loss of signal upon heating the proteins from 40 to 50 °C (Fig. 3, G–I). Loss of protein rigidity was observed at all tested calcium concentrations, a finding consistent with previously reported results (24–26). Because CD in the near-UV region measures the chirality around aromatic residues, these findings are also consistent with the results from Fig. 3, A–F (analysis of the 228 nm “shoulder” seen in the far-UV spectra), that calreticulin experiences a loss of rigidity upon the application of heat.

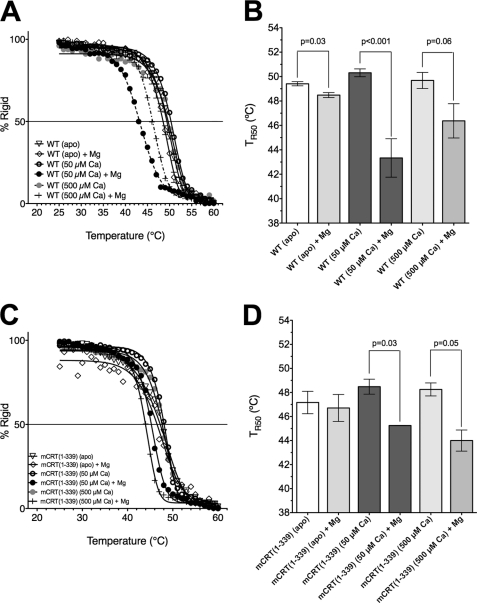

Furthermore, observing the near-UV CD signal at 280 nm while varying the temperature from 20 to 60 °C allowed for the calculation of a midpoint for the loss of rigidity (TR50) for mCRT(WT) as well as mCRT(1–339) in their apo forms, as well as with 50 μm, 500 μm, or 5 mm CaCl2 (Fig. 4, A and B). mCRT(WT) displayed variability in its TR50 depending on the level of calcium in the environment (Fig. 4C). As observed in the near UV-CD analyses, occupancy of the high affinity site at 50 μm CaCl2 significantly increased the TR50 value (ΔTR50 = 0.9 °C), whereas a nonsignificant decrease in the mCRT(WT) TR50 was observed upon further increasing the calcium concentration from 50 to 500 μm. Further increasing the calcium concentration to 5 mm caused a reduction in structural rigidity (ΔTR50 = 2.0 °C) to a level similar to that seen with mCRT(1–339). A small increase in rigidity was also observed with mCRT(1–339) on increasing the calcium concentration from 0 to 50 μm (Fig. 4C), although the extent of the increase was statistically nonsignificant. Further increasing the calcium concentration to 500 μm and 5 mm did not significantly change the rigidity of mCRT(1–339) (Fig. 4C). Together, these findings indicate that wild type calreticulin experiences an increase in rigidity upon occupancy of its high affinity site, and a decrease in its structural rigidity at high calcium concentrations.

FIGURE 4.

Calreticulin undergoes a loss of rigidity upon heating. Measurement (A and B) and quantification (C) of the TR50 of calreticulin for mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–339) in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) and 10 mm NaCl buffer containing 0, 50 μm, 500 μm, or 5 mm CaCl2 as indicated. Bar chart depicts mean TR50 ± S.E. (average of 2–6 independent analyses). D, in contrast to its tertiary structural rigidity, mCRT does not undergo a melting reaction (significant loss of secondary structure) upon heating from 20 to 90 °C as seen via the measurement of the far-UV CD signal for mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–339) in 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.5) and 500 mm NaF buffer containing 0 or 500 μm CaCO3 as indicated. Data represent the average of 2 independent scans. The reported p values indicate significant differences and were derived using two-tailed unpaired t tests. The p value for the difference in the TR50 of mCRT(WT) when going from 500 μm to 5 mm CaCl2 was 0.06. Unlike mCRT(WT), mCRT(1–339) showed no significant changes in TR50 (all p values > 0.3) associated with increasing [CaCl2]. Data were obtained using a Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter.

These findings with the lability of the tertiary structure rigidity of calreticulin are in sharp contrast to its secondary structural stability. This was measured by monitoring the CD signal in the far-UV region (at 222 nm) over a temperature range from 20 to 90 °C, which indicates that calreticulin does not undergo a true melting reaction upon the application of heat (Fig. 4D), thereby supporting our prior observations (as depicted in Fig. 3) that within any given concentration of calcium, the secondary structure of calreticulin is largely invariant as a function of temperature.

Impacts of Magnesium on Structural Rigidity and Calcium Binding of Calreticulin

Previous measurements of the structural rigidity of calreticulin were carried out in the presence of 3 mm MgCl2 with 50 or 1000 μm CaCl2 (25). These studies indicated that high concentrations of calcium enhanced the rigidity of calreticulin when 3 mm MgCl2 was also present. To explain differences between these findings and the results shown in Fig. 4, wherein structural rigidity of calreticulin was reduced by millimolar concentrations of calcium, we asked whether magnesium competed with calcium for binding to calreticulin. Near-UV temperature scans of mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–339) were undertaken in 0, 50, or 500 μm CaCl2, in the presence or absence of 1 mm MgCl2.

As can be seen in Fig. 5, the presence of 1 mm MgCl2 indeed results in significant decreases in the observed TR50 values for mCRT(WT) under all calcium conditions tested. The magnitudes of the reductions were highest in the 50 μm CaCl2 condition (ΔTR50 = 7.0 °C). MgCl2-induced reductions in TR50 values were also significant with mCRT(1–339) at 50 and 500 μm CaCl2. Consistent with the lack of significant increase of the TR50 of mCRT(1–339) by 50 μm CaCl2, (Fig. 4C), the extent of MgCl2-induced reduction in TR50 was less significant with mCRT(1–339) compared with mCRT(WT) at 50 μm CaCl2. These findings suggested that magnesium competes with both calcium-binding sites of calreticulin. ITC was thus used to measure calcium binding to the high affinity site of mCRT(1–339) in the presence of 1 mm MgCl2. Twenty-five sequential injections of 1.7 μm CaCl2 were added to mCRT(1–339) in 1 mm MgCl2. Additionally, calcium binding to the low affinity sites of calreticulin was also analyzed in the presence of 1 mm MgCl2 by performing 25 sequential injections of 33 μm to mCRT(WT) in 50 μm CaCl2 and 1 mm MgCl2. These results (Table 1) showed no measurable binding of calcium to the high affinity calcium-binding site of calreticulin in the presence of 1 mm MgCl2, and greatly reduced binding (>10-fold decrease in affinity for calcium) to the low affinity sites. Taken together with the near-UV CD data (Fig. 5), these findings suggest that magnesium exerts its destabilizing effect on calreticulin by competing with calcium for binding to the high affinity site, as well as by occupying its low affinity calcium-binding sites.

FIGURE 5.

Magnesium affects the tertiary structural rigidity of mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–339) in a calcium-dependent manner. A and B, effects of 1 mm MgCl2 on rigidity of mCRT(WT). Measurement (A) and quantification (B) of TR50 values for mCRT(WT) in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) and 10 mm NaCl buffer with or without 50 or 500 μm CaCl2 and in the presence or absence of 1 mm MgCl2. C and D, similar to panels A and B, but analyzing effects of 1 mm MgCl2 on rigidity of mCRT(1–339). Bar charts show mean TR50 ± S.E. (average of 2–6 independent analyses). Data derived in the absence of 1 mm MgCl2 were presented in Fig. 4. The reported p values indicate significant differences obtained from two-tailed unpaired t tests. As shown in panel D, mCRT(1–339) in its apo state did not show a significant decrease in TR50 in the presence of 1 mm MgCl2 (p = 0.78). Data were obtained using a Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter.

Different Segments of the Acidic Domain Differentially Impact Secondary Structure Content of Calreticulin and Calcium-dependent Changes in Secondary Structure

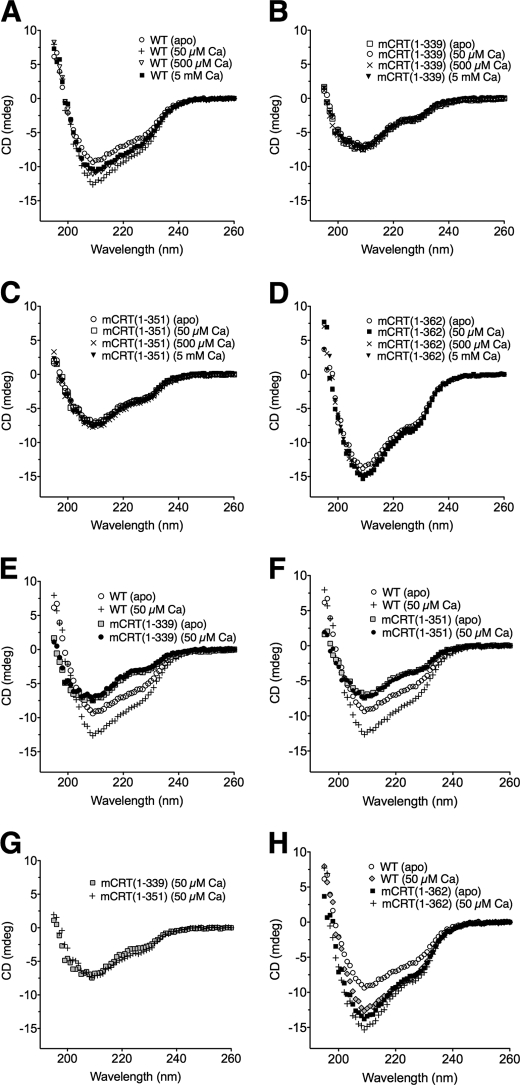

The data thus far revealed an increase in the structural rigidity of calreticulin upon occupancy of its high affinity site and a decrease in structural rigidity at high calcium concentrations (Fig. 4). To better understand the nature of structural changes in calreticulin as a function of calcium binding, far-UV CD spectra and DSC scans were undertaken at different calcium concentrations with mCRT(WT), mCRT(1–339), mCRT(1–362) (which contains the N-terminal region of the acidic domain but lacks the C terminus of the acidic domain), and mCRT(1–351) (which contains the entire C-terminal helix visualized in the crystal structure of the globular domain of calreticulin (PDB code 3O0V) (4) as well as five additional unstructured residues at the start of the acidic domain).

Far-UV CD spectra at 37 °C revealed that the stability of the secondary structure of mCRT(WT) is dependent upon the concentration of calcium in the environment (Fig. 6A). Indeed, in the case of the apoprotein, the far-UV CD signal is consistently weaker than that seen in 50 (corresponding to low ER calcium) or 500 μm CaCO3 (resting calcium concentration in the ER). Furthermore, the far-UV CD signal of mCRT(WT) is slightly weaker at 500 μm and 5 mm CaCO3 than that seen in 50 μm CaCO3, indicating that occupancy of the low affinity sites of calreticulin reduces its secondary structure content (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

The environmental calcium concentration impacts the secondary structure content of mCRT(WT), but not of mCRT(1–339), mCRT(1–351), or mCRT(1–362). Far-UV CD scans of mCRT(WT) (A), mCRT(1–339) (B), mCRT(1–351) (C), mCRT(1–362) (D), overlay of mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–339) (E) in 0 and 50 μm CaCO3, overlay of mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–351) in 0 and 50 μm CaCO3 (F), overlay of mCRT(1–351) and mCRT(1–339) in 50 μm CaCO3 (G), and overlay of mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–362) in 0 and 50 μm CaCO3 (H). Proteins were in 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.5) and 500 mm NaF with 50 μm, 500 μm, or 5 mm CaCO3 added as indicated. Data represent the averaged values of 4 independent sets of scans and were obtained using an Aviv 62DS spectropolarimeter.

With mCRT(1–339), the far-UV CD signal is not significantly enhanced by the addition of calcium, compared with the apo condition (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, at a given calcium concentration, mCRT(1–339) shows a decreased far-UV CD signal compared with mCRT(WT), particularly at 50 μm CaCO3 (Fig. 6E). Similar differences in calcium-induced secondary structure changes between mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–339) were seen at 20 and 60 °C (data not shown). Interestingly, the far-UV CD spectra of mCRT(1–351) were remarkably similar to those of mCRT(1–339) with respect to the strength of the far-UV CD signal and its invariance in the presence of calcium when compared with mCRT(WT) (Fig. 6, C, F, and G). Compared with mCRT(WT), weaker far-UV CD signals and calcium-dependent changes in the far-UV CD signals of mCRT(1–339) and mCRT(1–351) suggested that the acidic domain may be the region whose secondary structure is stabilized upon occupancy of the high affinity calcium-binding site of mCRT(WT), and/or that the presence of the acidic domain helps stabilize the secondary structure content of the globular domain.

Previous far-UV CD data using a C-terminal His6-tagged (totaling 23 residues) rabbit calreticulin acidic domain deletion construct (consisting of residues 1–343) showed a secondary structure profile similar to that seen in full-length rabbit calreticulin (24). The discrepancy between this result and the findings reported in this paper (24) might be accounted for by C-terminal differences between the two proteins used. It is possible that the addition of 23 residues C-terminal to the calreticulin construct (24) could alter the secondary structure profile of the protein and result in the observed discrepancy. All mCRT constructs used in the present studies contain residual N-terminal tripeptide sequences following cleavage of the histidine tag, but were untagged at the C terminus. Indeed as discussed below, the C-terminal sequence of calreticulin profoundly impacts its structural stability.

The far-UV CD spectra for apo-mCRT(1–362) revealed it to have a stronger secondary structure profile than apo-mCRT(WT) (Fig. 6, D and H). In addition, the secondary structure profile of mCRT(1–362) is less variable in response to calcium additions compared with mCRT(WT). These findings indicate that the reduced secondary structure content of the apo form of mCRT(WT) and calcium-dependent enhancement in secondary structure content seen in mCRT(WT) arise due to the presence of the C terminus of the acidic domain. Furthermore, the increased far-UV CD signal in mCRT(1–362) compared with mCRT(1–339) and mCRT(1–351) suggests that the presence of residues 352–362 is strongly stabilizing to the overall secondary structure of mCRT. Calcium occupancies of the high and low affinity sites in mCRT(WT) partially protect against the destabilization mediated by the C terminus of its acidic domain.

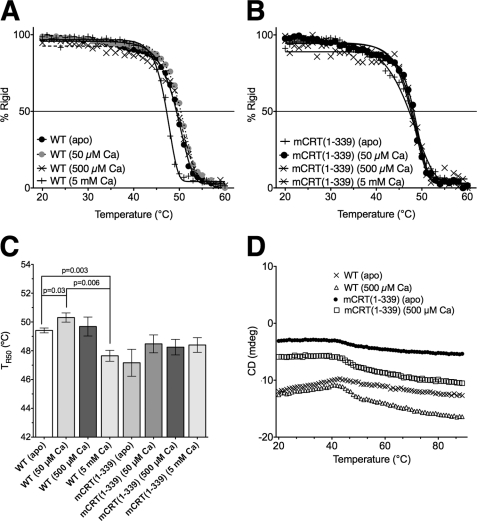

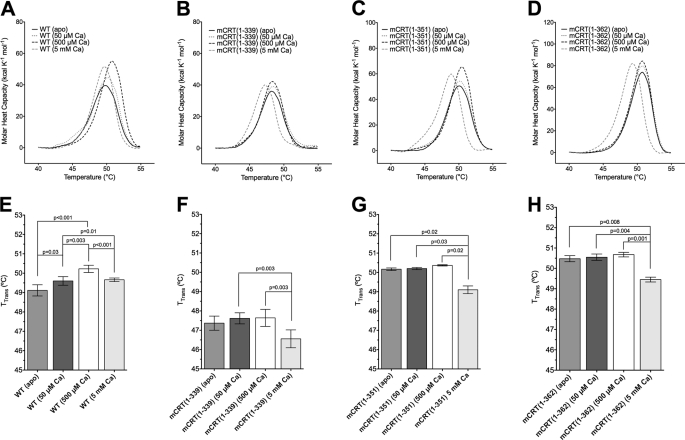

Enhanced Exposure of Aromatic Residues in High Calcium and Calcium-depleted Environments

DSC analyses of mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–339) revealed a single temperature of transition (TTrans; the transition midpoint for exposure of hydrophobic residues of the protein to solvent) at temperatures up to 120 °C. For mCRT(WT), TTrans values increased significantly upon raising the [CaCl2] from 0 to 50 μm as well as from 50 to 500 μm, with a decrease in TTrans upon further increasing the [CaCl2] to 5 mm (Fig. 7, A and E).

FIGURE 7.

The C terminus of the acidic region of calreticulin is required for calcium-dependent enhancements in thermostability over the ER range of calcium concentrations, whereas the globular domain mediates the reduction in thermostability of calreticulin at high calcium concentrations. Representative DSC scans (top panels) and quantifications of TTrans values (lower panels) for mCRT(WT) (A and E), mCRT(1–339) (B and F), mCRT(1–351) (C and G), and mCRT(1–362) (D and H) in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) and 10 mm NaCl buffer containing 0, 50 μm, 500 μm, or 5 mm CaCl2 as indicated. Bar graphs represent mean TTrans ± S.E. (average of at least 3 independent sets of analyses). The p values shown on the bar graphs indicate significant differences obtained from paired t tests. Apo-mCRT(WT) was found to have a significantly lower TTrans value than apo-mCRT(1–351) (p = 0.05 in an unpaired t test) and mCRT(1–362) (p = 0.009 in an unpaired t test). The TTrans value for apo-mCRT(1–351) was not significantly lower than apo-mCRT(1–362) (p = 0.16 in an unpaired t test). The TTrans values for mCRT(1–339) under all tested [CaCl2] (0 μm, 50 μm, 500 μm, and 5 mm CaCl2) were significantly lower compared with other constructs at similar [CaCl2] (all p values < 0.009 in unpaired t tests). The p value for the difference in TTrans between apo-mCRT(1–339) versus mCRT(1–339) in 5 mm CaCl2 was 0.2 in an unpaired t test.

DSC analysis of mCRT(1–339) revealed it to exhibit reduced variability and no significant differences between TTrans values that were derived from 0 to 500 μm CaCl2, although a significant decrease in TTrans was observed upon increasing the [CaCl2] from 500 μm to 5 mm (Fig. 7, B and F). Similarly, mCRT(1–351) and mCRT(1–362) revealed minimal changes in TTrans from 0 to 500 μm CaCl2 (Fig. 7, C, D, G, and H). Furthermore, basal TTrans values for the apo forms of both mCRT(1–351) and mCRT(1–362) were significantly higher than that for apo-mCRT(WT). Additionally, the TTrans values for mCRT(1–339) were significantly lower than those of other mCRT constructs under all conditions tested (Fig. 7). Taken together, these findings suggest that the reduction in the basal TTrans of the apo form, as well as the calcium-dependent increases in TTrans seen with mCRT(WT) over the calcium concentration range of 0–500 μm are, to a large extent, mediated by the presence of the C terminus of the acidic domain. Additionally, the C terminus of the long helix of calreticulin appears to be an important determinant of the ease of exposure of hydrophobic residues in the protein.

In a manner similar to mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–339), further increasing the [CaCl2] from 500 μm to 5 mm (corresponding to >80% occupancy of the low affinity calcium binding sites) resulted in significant decreases in TTrans values for mCRT(1–351) and mCRT(1–362) (Fig. 7, C, D, G, and H). Given the significant decrease in TTrans observed in all tested calreticulin constructs over the 500 μm to 5 mm range of calcium concentrations, these findings suggest the occurrence of a global conformational change involving the globular domain, possibly one involving the C-terminal helix within the globular domain.

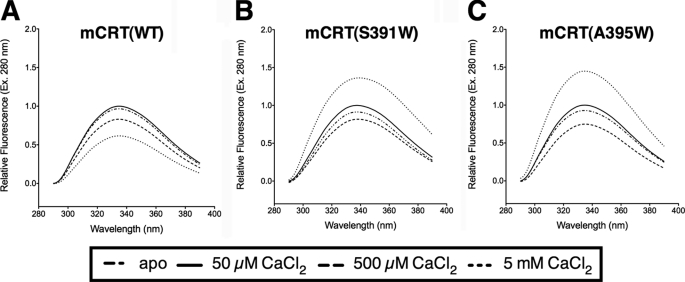

The C-terminal Portion of the Acidic Domain Becomes More Exposed in High Calcium Environments

Thus far, the data suggested that the presence of the C terminus of the acidic domain was destabilizing to calreticulin, particularly at low calcium concentrations. However, information on the exposure of the C terminus of the acidic domain in different calcium environments was unclear. To this end, fluorescence measurements were undertaken with mCRT(WT), mCRT(S391W), and mCRT(A395W). The latter two mutants were generated to assess whether different calcium-dependent conformational changes result in altered exposure of tryptophan residues introduced near the C terminus of the acidic domain of calreticulin.

Fluorescence analyses revealed mCRT(WT) to undergo a small increase in fluorescence emission (following excitation at 280 nm) upon increasing the [CaCl2] from 0 to 50 μm, followed by a progressive decrease in fluorescence emission (increased quenching) upon further increasing the [CaCl2] from 50 to 500 μm and 5 mm (Fig. 8A). Similarly, both mCRT(S391W) and mCRT(A395W) (constructs that have tryptophan residues at the C-terminal end of the acidic domain of calreticulin) showed a small increase in fluorescence emission upon increasing the [CaCl2] from 0 to 50 μm, followed by a decrease in fluorescence emission upon further increasing the [CaCl2] to 500 μm, with mCRT(A395W) showing increased quenching at 500 μm CaCl2 compared with mCRT(WT) and mCRT(S391W). These findings suggest increased burial of the C terminus of calreticulin over this range of calcium concentrations. In sharp contrast to mCRT(WT), a marked increase in fluorescence emission was observed for mCRT(S391W) and mCRT(A395W) upon further increasing the [CaCl2] to 5 mm (Fig. 8, B and C). Taken together with our findings from far-UV CD and DSC analyses of mCRT(WT), mCRT(1–339), mCRT(1–351), and mCRT(1–362), these data suggest that at high calcium concentrations, conformational changes in the interactions between the acidic and globular domains of calreticulin result in increased exposure of its C terminus to the external solvent environment.

FIGURE 8.

The C terminus of calreticulin becomes more exposed at high calcium concentrations. Fluorescence spectra of mCRT(WT) (A), mCRT(S391W) (B), and mCRT(A395W) (C) in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5) and 10 mm NaCl buffer with varying CaCl2 concentrations (0 μm, 50 μm, 500 μm, and 5 mm) depicting changes in intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence following excitation at 280 nm are shown. Data were collected in the range of 290–390 nm. Data represent the average of at least 2 independent sets of scans.

DISCUSSION

In these studies, we show that calreticulin possesses two distinct sets of calcium-binding sites: a single high affinity site located in the globular domain of calreticulin that binds a single calcium with a KD value of 16.6 μm, along with C-terminal low affinity, high capacity sites with approximate KD values of 590.6 μm (Table 1). Taken together, the ITC measurements undertaken in this study are consistent with the 45Ca2+-based binding studies of Baksh and Michalak (7) that indicated the presence of a high affinity (KD = 11.4 μm) and multiple low affinity (KD = 2 mm) binding sites in calreticulin. However, measurements of high affinity calcium binding to both mCRT(ΔP) and mCRT(1–339) with binding parameters similar to those derived for mCRT(WT) indicate that the globular domain, rather than the P-domain, is the region wherein the high affinity calcium-binding site of calreticulin is located. Asp311 within the globular domain is a key residue that defines the high affinity calcium-binding site (Table 1). These results confirm findings of the nature of the high affinity calcium-binding site of calreticulin from the crystal structure of its globular domain (4). Additionally, the studies reveal the presence of low affinity calcium-binding sites within the C terminus of the globular domain and the N terminus of the acidic domain that appear to be independent of the rest of the acidic domain.

4–6 enthalpically driven low affinity sites were measured within the C-terminal region of mCRT(WT) as well as mCRT(1–362) (Table 1), whereas previous data showed calreticulin binding 17–18 mol/calcium/mol of protein (7). Given the differences in technique (equilibrium dialysis versus ITC), it is possible that there are additional low affinity calcium-binding sites in the C-terminal region of the acidic domain of calreticulin that are not detectable via ITC due to the nature of calcium binding (entropy- versus enthalpy-driven) and/or heat-of-dilution effects. Further assessments of the abilities of different C-terminal truncation constructs to function in the restoration of ER calcium homeostasis in calreticulin-deficient cells will provide additional insights into functional requirements for calcium binding by the C-terminal segments of the acidic domain.

Given the relatively high concentration of intracellular magnesium (estimated at 0.8 mm (34)), we asked whether magnesium could compete with calcium for binding to the high and low affinity calcium-binding sites of calreticulin. Using ITC, we showed that magnesium indeed competes with calcium for binding to both sites (Table 1). These findings indicate that the prevailing divalent cation environment will profoundly impact calreticulin structure and its ability to bind calcium. Under conditions of decreasing ER calcium following stimulation of cells, a magnesium concentration of 0.8 mm is expected to compete with calcium binding based on the data shown in Fig. 5 and Table 1, which in turn could facilitate calcium release from calreticulin, enhancing the pool of free ER calcium for transport into the cytosol. Thus, competition by magnesium for calcium-binding sites could be an important mechanism for calcium storage that is coupled to the regulated release of calcium.

A surprising finding from these studies is that the secondary structure of calreticulin is quite invariant at high temperatures (up to 60 °C and higher). These findings indicate that calreticulin is a thermostable protein behaving similarly to small heat-shock protein family members like catfish αB-crystallin and HSP16.5 from Methanococcus jannaschii with reported secondary structure stabilities up to 60–80 °C (35, 36). In addition to its secondary structural stability, several structural and functional features of calreticulin resemble those described for small heat shock protein family members (reviewed in Ref. 37). Similarities include the ability to inhibit irreversible aggregation of proteins and stress-induced chaperone activity. Although calreticulin is generally considered to be a glycoprotein-specific chaperone, a number of in vitro studies have demonstrated that calreticulin also displays glycan-independent polypeptide-specific chaperone activities (21, 38). Efficient polypeptide-specific chaperone activity requires specific conformational changes in calreticulin, including those induced by calcium depletion and heat shock (21). We show here that calreticulin maintains significant secondary structure content even when heated beyond its TR50 and TTrans (Fig. 3, A–F). Thus, rather than mediating a complete unfolding of calreticulin, heat induces reorganization of the calreticulin structure, exposing hydrophobic residues while maintaining significant secondary structure content (Figs. 3 and 7). Calreticulin is known to be up-regulated by heat shock (39), and the observed heat stability of its secondary structure likely contributes to the chaperone functions of calreticulin under heat stress in vivo. Furthermore, the heat stability of the secondary structure of calreticulin (Fig. 3), coupled with exposure of hydrophobic residues (Fig. 7) at temperatures approaching the TTrans values is likely responsible for the occurrence of calreticulin oligomerization upon heating and cooling (40, 41). As such, the findings presented here provide further structural evidence for the notion that the cellular requirements for calreticulin may extend beyond its classical lectin-based functions.

Remarkably, the heat stability of the secondary structure of calreticulin was observed even with the apoprotein (Fig. 3), indicating that, at 37 °C, calreticulin is likely to be significantly structured when localized in the cytosol (42, 43). At calcium concentrations prevalent in the cytosol (∼100 nm (reviewed in Refs. 30 and 31)), the structural features of calreticulin are expected to resemble those described here for the apoprotein, with neither its high nor low affinity sites occupied. Calcium depletion induces the polypeptide-specific chaperone activity of calreticulin in vitro (21, 27). Therefore, in the low calcium environment of the cytosol, calreticulin is expected to function as a more efficient polypeptide-specific chaperone when compared with the ER. Several protein-protein interactions mediated by calreticulin in the cytosol may be governed by hydrophobic interaction-based binding, including interactions with steroid hormone receptors and its putative interactions with the cytoplasmic regions of α-integrins (reviewed in Ref. 1).

In contrast to the thermostability of its secondary structure, the tertiary structural rigidity of calreticulin was found to be heat-labile and dependent upon the calcium levels in the environment (Fig. 4). A similar observation was made with DSC, with the temperature at which calreticulin exposes buried hydrophobic residues (TTrans) varying as a function of calcium concentration (Fig. 7). Interestingly, despite being a multidomain protein, calreticulin showed a single thermal event as measured via DSC, suggesting that the observed transition corresponds to exposure of hydrophobic residues in the globular domain. This possibility is supported by the fact that the acidic domain of calreticulin contains very few hydrophobic residues, along with the fact the P-domain (which consists of a hairpin fold) lacks a hydrophobic core, as seen in its NMR structure (5).

The results of the studies presented here support a model (depicted in Fig. 9) wherein the core globular domain of calreticulin has a defined secondary structural content, even in the apo condition. Upon increasing the concentration of calcium from 0 to 50 μm (corresponding to 80% occupancy of its high affinity site) mCRT(WT) increases its secondary structure content (Fig. 6A), along with its tertiary structure rigidity and thermostability (as assessed via increased TR50 and TTrans values) (Figs. 4 and 7). Apo-mCRT(1–362) has higher TTrans values than apo-mCRT(WT) (Fig. 7), displays a stronger secondary structure profile than apo-mCRT(WT), and displays reduced secondary structural variability in response to calcium binding compared with mCRT(WT) (Fig. 6). On the other hand, although mCRT(1–351) displayed a reduced secondary structural content than mCRT(WT) and mCRT(1–362), the thermostability of its tertiary structure was enhanced relative to mCRT(WT) and calcium-dependent variations in secondary and tertiary structures were reduced relative to those seen in mCRT(WT) (Figs. 6 and 7). Taken together, these findings suggest that in the apo condition, the N terminus of the acidic domain may interact with, and stabilize the globular domain structure (Fig. 9A). N-terminal residues of the acidic domain may adopt a helical structure, a possibility supported by secondary structure predictions (Fig. 1D) and biophysical studies of an N-terminal-derived peptide (16). The helix could either be an extension of the long C-terminal helix of the globular domain or an independent helix. The increased helical content of mCRT(1–362) could in part explain its stronger far-UV CD profile relative to mCRT(1–339) and mCRT(1–351) (Fig. 6). On the other hand, C-terminal residues of the acidic domain may destabilize interactions within the globular domain as well as interactions between the globular domain and the N terminus of the acidic domain (Fig. 9B).

FIGURE 9.

The acidic domain of calreticulin interacts with the globular domain and contributes to calcium dependence of the secondary structure content and thermostability of calreticulin. The long helix and acidic domain of calreticulin are depicted in dark gray. A, under calcium-depleted (apo) conditions, the presence of the N terminus of the acidic domain in mCRT(1–362) increases its secondary structure content stability and thermostability, suggesting that the N-terminal region of the acidic domain forms stabilizing interactions with the globular domain. B–D, the presence of the C-terminal residues of the acidic domain in mCRT(WT) destabilizes the globular domain, an effect that is mitigated upon occupancy of the calcium-binding sites of calreticulin. E, at high concentrations of calcium (5 mm), as the low affinity calcium-binding sites move toward full occupancy, independent disruption of electrostatic interactions within the globular domain initiates a global conformational change, including one that causes the C-terminal portion of the acidic domain of calreticulin to become more exposed to the external solvent environment.

Tryptophan fluorescence measurements indicate that the C terminus of the acidic domain is relatively buried at calcium concentrations ranging from 0 to 50 μm (Fig. 8), and suggest that the destabilizing effects of C-terminal residues of the acidic domain likely do not arise from a fully exposed and disordered structure. Occupancy of the calcium-binding sites of calreticulin reduces the extent of destabilization mediated by the C terminus acidic domain, possibly by rigidifying the structure and stabilizing multiple interactions centered around the calcium-binding site (Fig. 9, B and C).

Further increasing the calcium concentration to 500 μm results in ∼50% occupancy of the enthalpy-driven low affinity calcium-binding sites in the N terminus of the acidic domain and the C terminus of the globular domain. In the context of mCRT(WT), occupancy of low affinity sites result in increased structural stability as assessed by an increased TTrans (Fig. 7). Thus, it is reasonable to postulate that occupancy of low affinity sites may further protect against tertiary structural destabilization by enhancing interactions between the N-terminal region of the acidic domain and the globular domain (Fig. 9D). Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (Fig. 8) indicates that the C terminus of the acidic domain is also relatively buried at a calcium concentration of 500 μm. There is a slight reduction in secondary structural content of mCRT(WT) at 500 μm compared with 50 μm, but compared with the apo condition, the higher secondary structural content is observed for mCRT(WT) at calcium concentrations of both 50 and 500 μm (Fig. 6).

At high calcium concentrations (5 mm), the low affinity calcium-binding sites move toward full occupancy and the associated tertiary structure destabilization, as observed by decreases in TTrans values, is independent of the presence of the acidic domain (because the decrease in thermostability is observed for all tested calreticulin constructs) (Fig. 7). In addition, increased exposure of the C terminus of the acidic domain (observed in the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence) (Fig. 8) suggests that the conformational changes that accompany the increased occupancy of the low affinity sites of calreticulin complement a re-organization of the interactions between the acidic domain and the rest of the globular domain (Fig. 9E). This destabilizing conformational change may occur via disruption of electrostatic interactions between the long C-terminal helix in the globular domain and the rest of the calreticulin molecule. Analysis of the crystal structure of the globular domain of calreticulin (PDB code 3O0V) (4) revealed that the long helix of calreticulin forms electrostatic interactions with the convex β-sheet in its globular domain. In particular, interactions between Glu337 and Lys81, Glu323 and Gln77, Glu323 and Lys168, Trp330 and Asp170, Lys334 and Asp170, Glu319 and Arg160, and Asn327 and Asn171 could be altered or disrupted based on the environmental calcium milieu.

Previous findings indicated that the isolated acidic domain of calreticulin is able to fold and attain a more compact form as it binds calcium (16). However, although it could be the case that the acidic domain of calreticulin is folded independently of its globular domain in high calcium environments (Fig. 8), it appears that folding of the acidic domain per se does not drive the transition of the acidic domain to the independently folded state, because all tested calreticulin constructs were shown to be less thermostable at high calcium levels (Fig. 7). Rather, as noted above, high calcium-induced destabilization of the structure of the globular appears to induce the structural transition of the acidic domain into one in which its C terminus is in a more solvent-exposed conformation.

Overall, the data provide strong evidence for interactions between the acidic and globular domains of calreticulin over the range of ER calcium concentrations. Interactions between the acidic and globular domains of calreticulin vary as a function of calcium concentration, with interactions being enhanced over the range of ER calcium concentrations (50–500 μm calcium) and destabilized under calcium-depleting (apo) conditions and at higher calcium concentrations (5 mm) (Fig. 9). The latter conformations are likely relevant to the functions of calreticulin in the cytosol and cell surface, respectively. More subtle but distinct changes were also observed over the 50–500 μm calcium concentration range, representative of variations that occur within the ER. Recent findings from our laboratory have shown that calreticulin becomes glycosylated in calcium-depleting environments, with calreticulin mutants that exhibit lower thermostabilities relative to mCRT(WT) being more significantly glycosylated (44). Interestingly, Asn327, the only potential N-linked glycosylation site on mCRT (based on its primary sequence) is located in the long helix of the calreticulin and is predicted to be an exposed residue (as seen in the crystal structure of the globular domain of calreticulin (PDB code 3O0V) (4)) (Fig. 1). Based on the findings reported in this article, we propose that in normal ER calcium environments, interactions between the acidic domain and the globular domain of calreticulin help shield Asn327 from glycosylation. On the other hand, under calcium-depleted conditions, altered interactions between the acidic and globular domains could result in increased exposure of Asn327, allowing it to become accessible for glycosylation. Similarly, mutations in calreticulin that decrease its thermostability could induce more open conformations of the acidic domain due to decreased tertiary structural rigidity and allow for increased accessibility of Asn327.

In cells, the calreticulin-ERp57 complex has been shown to interact with the sacroplasmic endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA), inhibiting its activity in a calcium-dependent manner. High [Ca2+]ER inhibited SERCA 2b activity, whereas lowering [Ca2+]ER induced the dissociation of calreticulin-ERp57 from SERCA 2b (tested over a 10 to 300 μm range) (45). This interaction has been suggested to be important for the regulated entry of calcium into the ER in a calcium concentration-dependent manner (45). The observed structural changes that take place in calreticulin in response to different calcium levels could underlie such calcium-dependent functional outcomes. Furthermore, different calcium environments could also impact intracellular trafficking of calreticulin via effects on calreticulin structure and interactions with other ER proteins. The acidic domain of calreticulin has been shown to be important for ER retention as well as for the retro-translocation of calreticulin to the cytosol (42, 46). It is possible that cellular differences in ER calcium concentration and calreticulin binding factors could underlie its localization in post-ER compartments and in the cytosol of some cell types, via effects on acidic domain-mediated interactions.

In conclusion, based on biophysical studies, our results provide a model for changes in inter-domain interactions in calreticulin under varying divalent cation environments. Furthermore, ITC-based studies indicate that low affinity binding sites are detectable with mCRT(1–362) and mCRT(1–351) but not with mCRT(1–339). Together, the data suggest that low affinity calcium-binding sites are occupied in the context of the acidic domain/globular domain interactions rather than in an independently folded acidic domain context, results that have implications for mechanisms and structures that contribute to ER calcium homeostasis. These findings provide preliminary insights into the putative in vivo domain organization of the intact protein and serve to guide on-going efforts to solve the x-ray crystal structure of full-length calreticulin. Experimentally derived structures for calreticulin in calcium-depleted and high-calcium states would aid in further refinement of the proposed models.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Joseph Schauerte and Dr. Kathleen Wiser for technical assistance with undertaking measurements using the CD and ITC instruments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant AI 066131.

- CRT

- calreticulin

- DSC

- differential scanning calorimetry

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry.

REFERENCES

- 1. Michalak M., Groenendyk J., Szabo E., Gold L. I., Opas M. (2009) Biochem. J. 417, 651–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Williams D. B. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119, 615–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schrag J. D., Bergeron J. J., Li Y., Borisova S., Hahn M., Thomas D. Y., Cygler M. (2001) Mol. Cell 8, 633–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kozlov G., Pocanschi C. L., Rosenauer A., Bastos-Aristizabal S., Gorelik A., Williams D. B., Gehring K. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 38612–38620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ellgaard L., Riek R., Herrmann T., Güntert P., Braun D., Helenius A., Wüthrich K. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 3133–3138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frickel E. M., Riek R., Jelesarov I., Helenius A., Wuthrich K., Ellgaard L. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 1954–1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baksh S., Michalak M. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 21458–21465 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nash P. D., Opas M., Michalak M. (1994) Mol. Cell Biochem. 135, 71–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fasolato C., Pizzo P., Pozzan T. (1998) Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 1513–1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nakamura K., Zuppini A., Arnaudeau S., Lynch J., Ahsan I., Krause R., Papp S., De Smedt H., Parys J. B., Muller-Esterl W., Lew D. P., Krause K. H., Demaurex N., Opas M., Michalak M. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 154, 961–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Xu W., Longo F. J., Wintermantel M. R., Jiang X., Clark R. A., DeLisle S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 36676–36682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sambrook J. F. (1990) Cell 61, 197–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hogan P. G., Lewis R. S., Rao A. (2010) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28, 491–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mattson M. P. (2010) Sci. Signal 3, pe10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang K. (2010) Int. J. Clin Exp. Med. 3, 33–40 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Villamil Giraldo A. M., Lopez Medus M., Gonzalez Lebrero M., Pagano R. S., Labriola C. A., Landolfo L., Delfino J. M., Parodi A. J., Caramelo J. J. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 4544–4553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gold L. I., Eggleton P., Sweetwyne M. T., Van Duyn L. B., Greives M. R., Naylor S. M., Michalak M., Murphy-Ullrich J. E. (2010) FASEB J. 24, 665–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Corbett E. F., Oikawa K., Francois P., Tessier D. C., Kay C., Bergeron J. J., Thomas D. Y., Krause K. H., Michalak M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 6203–6211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Le A., Steiner J. L., Ferrell G. A., Shaker J. C., Sifers R. N. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 7514–7519 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ong D. S., Mu T. W., Palmer A. E., Kelly J. W. (2010) Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 424–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rizvi S. M., Mancino L., Thammavongsa V., Cantley R. L., Raghavan M. (2004) Mol. Cell 15, 913–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thammavongsa V., Mancino L., Raghavan M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33497–33505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Corbett E. F., Michalak K. M., Oikawa K., Johnson S., Campbell I. D., Eggleton P., Kay C., Michalak M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27177–27185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Conte I. L., Keith N., Gutiérrez-Gonzalez C., Parodi A. J., Caramelo J. J. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 4671–4680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li Z., Stafford W. F., Bouvier M. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 11193–11201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bouvier M., Stafford W. F. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 14950–14959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Del Cid N., Jeffery E., Rizvi S. M., Stamper E., Peters L. R., Brown W. C., Provoda C., Raghavan M. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 4520–4535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jones D. T. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 292, 195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I. M., Wilm A., Lopez R., Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G. (2007) Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burdakov D., Petersen O. H., Verkhratsky A. (2005) Cell Calcium 38, 303–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Meldolesi J., Pozzan T. (1998) Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 10–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pinton P., Rizzuto R. (2006) Cell Death Differ. 13, 1409–1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Woody R. W. (1994) Eur. Biophys. J. 23, 253–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kelepouris E., Kasama R., Agus Z. S. (1993) Miner. Electrolyte Metab. 19, 277–281 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim R., Lai L., Lee H. H., Cheong G. W., Kim K. K., Wu Z., Yokota H., Marqusee S., Kim S. H. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 8151–8155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yu C. M., Chang G. G., Chang H. C., Chiou S. H. (2004) Exp. Eye Res. 79, 249–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Haslbeck M., Franzmann T., Weinfurtner D., Buchner J. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 842–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Saito Y., Ihara Y., Leach M. R., Cohen-Doyle M. F., Williams D. B. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 6718–6729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Conway E. M., Liu L., Nowakowski B., Steiner-Mosonyi M., Ribeiro S. P., Michalak M. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 17011–17016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jørgensen C. S., Ryder L. R., Steinø A., Højrup P., Hansen J., Beyer N. H., Heegaard N. H., Houen G. (2003) Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 4140–4148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mancino L., Rizvi S. M., Lapinski P. E., Raghavan M. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 5931–5936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Afshar N., Black B. E., Paschal B. M. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 8844–8853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shaffer K. L., Sharma A., Snapp E. L., Hegde R. S. (2005) Dev. Cell 9, 545–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jeffery E., Peters L. R., Raghavan M. (November 16, 2010) J. Biol. Chem. 10.1074/jbc.M110.180877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li Y., Camacho P. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 164, 35–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sönnichsen B., Füllekrug J., Nguyen Van P., Diekmann W., Robinson D. G., Mieskes G. (1994) J. Cell Sci. 107, 2705–2717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]