Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α induces cytoskeleton and intercellular junction remodeling in tubular epithelial cells; the underlying mechanisms, however, are incompletely explored. We have previously shown that ERK-mediated stimulation of the RhoA GDP/GTP exchange factor GEF-H1/Lfc is critical for TNF-α-induced RhoA stimulation. Here we investigated the upstream mechanisms of ERK/GEF-H1 activation. Surprisingly, TNF-α-induced ERK and RhoA stimulation in tubular cells were prevented by epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibition or silencing. TNF-α also enhanced phosphorylation of the EGFR. EGF treatment mimicked the effects of TNF-α, as it elicited potent, ERK-dependent GEF-H1 and RhoA activation. Moreover, EGF-induced RhoA activation was prevented by GEF-H1 silencing, indicating that GEF-H1 is a key downstream effector of the EGFR. The TNF-α-elicited EGFR, ERK, and RhoA stimulation were mediated by the TNF-α convertase enzyme (TACE) that can release EGFR ligands. Further, EGFR transactivation also required the tyrosine kinase Src, as Src inhibition prevented TNF-α-induced activation of the EGFR/ERK/GEF-H1/RhoA pathway. Importantly, a bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation assay and electric cell substrate impedance-sensing (ECIS) measurements revealed that TNF-α stimulated cell growth in an EGFR-dependent manner. In contrast, TNF-α-induced NFκB activation was not prevented by EGFR or Src inhibition, suggesting that TNF-α exerts both EGFR-dependent and -independent effects. In summary, in the present study we show that the TNF-α-induced activation of the ERK/GEF-H1/RhoA pathway in tubular cells is mediated through Src- and TACE-dependent EGFR activation. Such a mechanism could couple inflammatory and proliferative stimuli and, thus, may play a key role in the regulation of wound healing and fibrogenesis.

Keywords: Epithelial Cell, ERK, Rho, Signal Transduction, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF), Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor, GDP/GTP Exchange Factors, GEF-H1, Cytoskeleton

Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) is a pleiotropic proinflammatory cytokine that is synthesized as a membrane protein in response to inflammation, infection, and injury (1). Subsequently it is cleaved by the metalloproteinase TNF-α convertase enzyme (TACE)4 to release a 17-kDa soluble peptide (for review, see Ref. 2). TNF-α is a major regulator of immunity and inflammation as well as cell differentiation and death. Importantly, in the past years TNF-α has emerged as a central pathogenic factor in a number of chronic inflammatory diseases including rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease (3). TNF-α was also shown to contribute both to acute renal injury and chronic kidney disease (4, 5). In normal kidneys TNF-α is almost undetectable, but elevated intrarenal, serum, or urine concentrations were reported in various pathological states including ischemia reperfusion, endotoxemia, and early diabetic nephropathy (4–6). Recently it became clear, that TNF-α is produced in the injured kidneys not only by infiltrating immune cells but also by stimulated resident cells including the tubular epithelium. Importantly, kidney injury in various pathological states was prevented or mitigated by inhibition of TNF-α production, the addition of neutralizing antibodies or in TNF receptor knock-out mice (4). The central role of TNF-α in mediating kidney injury is, therefore, well established; however, the underlying mechanisms are incompletely understood. Effects of locally released TNF-α on the tubular epithelium could contribute to its deleterious actions. However, there are still gaps in our understanding of how TNF-α affects the tubular cells. For example, TNF-α is a well characterized inducer of apoptosis; however, in tubular cells some studies report that TNF-α induces apoptosis, whereas others show that it is a pro-survival factor (7–9).

TNF-α has a marked effect on both epithelial and endothelial cytoskeleton and intercellular junctions. Importantly, junction disruption and enhanced paracellular permeability induced by TNF-α seems to be a key contributor to various diseases, e.g. inflammatory bowel disease and lung injury (10–12). Our own work as well as that of others has also demonstrated that acute treatment with TNF-α enhances permeability of kidney tubular epithelial cells (13–15), which in turn could contribute to tubulointerstitial inflammation. Alterations in the cytoskeleton play a key role in downstream effects of TNF-α, including junction remodeling. The cytoskeleton rearrangement is mediated by Rac, RhoA, and Cdc42, members of the Rho family of small GTPases (16). Indeed, we have shown that the TNF-α-induced permeability increase in tubular cells requires RhoA and Rho kinase-dependent myosin phosphorylation (13). The activity of the Rho GTPases is tightly controlled by the action of a large family of stimulator GDP/GTP exchange factors (GEFs) and inhibitor GTPase activating proteins (17, 18). In search for mechanisms involved in TNF-α-induced RhoA activation, we have identified the RhoA/Rac exchange factor GEF-H1/Lfc as a mediator of the effect. Moreover, our work also showed that TNF-α stimulates GEF-H1 through ERK-dependent phosphorylation (13). The MEK/ERK pathway, therefore, is critical for GEF-H1 and RhoA stimulation. The upstream mechanisms of TNF-α-induced activation of the ERK/GEF-H1 pathway, however, remained undefined.

TNF-α has two receptors, the constitutively expressed, ubiquitous TNF receptor 1 TNFR1, p55) and the inducible TNF receptor 2 (TNFR2, p75) (19). In most cells, including normal tubular epithelial cells, TNFR1 is the predominant receptor (4). The receptors couple to a number of adapter proteins and initiate complex signaling cascades (1, 16, 20). The best explored of these are the pathways mediating activation of the caspase cascade, the p38, and JNK MAP kinases and the nuclear factor κB (NFκB) transcription factor. In contrast, the pathways leading to activation of ERK and Rho family small GTPases were much less studied and remain incompletely understood.

The aim of this work was to explore the mechanisms leading to TNF-α-induced activation of the ERK/GEF-H1/RhoA pathway. The best characterized activators of ERK are the growth factor receptors. Interestingly, TNF-α was shown to induce transactivation of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (EGFR) in a variety of cells (21–24). EGFR transactivation involves the release of EGFR ligands by metalloproteinases of the ADAM (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase) family, of which TACE or ADAM-17 is the best characterized member (25). Activated TACE cleaves the ectodomains of various transmembrane proteins, including the pro-form of EGFR ligands. TACE activation, therefore, leads to the release of active EGFR ligands, which in turn activate the EGFR. In fact, EGFR transactivation mediated by ADAM-family metalloproteinases is emerging as a common theme for a large variety of cells and stimuli (26). A similar mechanism, however, for TNF-α-induced signaling has not been explored in the tubular epithelium. Even more importantly, a potential role for EGFR transactivation in TNF-α-induced stimulation of the GEF-H1/RhoA pathway and cytoskeleton remodeling has not been studied. The EGFR is a strong activator of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway and is also known to stimulate small GTPases of the Rho family (27, 28). However, GEFs involved in the regulation of RhoA by EGFR remain mostly unidentified.

In this study we explored the hypothesis that the TNF-α-promoted cytoskeleton remodeling involves the EGFR. We show that TNF-α-induced activation of the ERK/GEF-H1/RhoA pathway in tubular cells requires TACE-dependent transactivation of the EGFR, identify GEF-H1 as the GEF involved in EGF-induced RhoA activation, and demonstrate that the tyrosine kinase Src mediates the TNF-α-induced EGFR transactivation. Our data, therefore, identify the EGFR/ERK/GEF-H1 pathway as a central mediator of TNF-α-induced RhoA activation. Finally, we also show that TNF-α stimulates EGFR-mediated proliferation of tubular epithelial cells and EGFR-independent activation of the early inflammatory transcription factor, NFκB. These data indicate that TNF-α exerts its effects on the tubular epithelium through EGFR-dependent and -independent pathways.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

PD98059, PP2, AG1478, and TAPI-1 (N-(R)-[2-(hydroxyaminocarbonyl)methyl]-4-methylpentanoyl-l-naphthylalanyl-l-alanine, 2-aminoethyl amide, TNF-α protease inhibitor-1) were from EMD Biosciences (Mississauga, On). EGF, TNF-α, and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) were from Sigma. BSA was from BioShop Canada (Burlington, On). The Complete Mini Protease inhibitor and PhosSTOP Phosphatase Inhibitor tablets were from Roche Diagnostics.

Antibodies against the following proteins were used: RhoA, phospho-p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) (Thr-202/Tyr-204), GEF-H1, phospho-Src family kinase (SFK) (Tyr-416), and EGF receptor (for detecting EGFR in MDCK cells) from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA); ERK1/2 and pERK1/2, EGF receptor (16F8) (for the immunoprecipitation experiments) and anti-p65 NFκB from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc (Santa Cruz, CA); GAPDH from EMD Biosciences; phosphotyrosine (Tyr(P), 4G10) and avian Src from Millipore (Billerica, MA); HA tag from Covance (Emeryville, CA); Vav2 from Epitomics (Burlingame, CA); β-actin from Sigma. Peroxidase and Cy3-labeled secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). HA-tag antibody coupled to agarose and A/G-agarose beads were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. DAPI nucleic acid stain was from Invitrogen.

Cells and Cell Treatment

LLC-PK1, a kidney proximal tubule epithelial cell line (clone 101 and 4), and MDCKII, a canine distal tubular epithelial cell line, were used as in our earlier studies (13, 29). Cells were maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotic suspension (penicillin and streptomycin) in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All tissue culture media and reagents were from Invitrogen. Confluent cells were serum-depleted for at least 3 h in DMEM before the experiments.

Vectors and Transient Transfection

The vectors used were kind gifts from the following investigators. cDNAs encoding for the glutathione transferase (GST)-Rho binding domain (RBD) portion of Rhotekin and GST-RhoA(G17A) (30) were from Dr. K. Burridge (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC); HA-ERK-2 was from Dr. M. Kohno (31); kinase-dead, dominant negative Src, and active Src were from Dr. S. Courtneidge (Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute), human EGFR was from Dr. S. J. Parsons (University of Virginia) (32), and HA-tagged TACE was from Dr. A. Ullrich (Max-Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Martinsried, Germany). LLC-PK1 cells were transfected using FuGENE 6 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The following DNA concentrations were used for transfecting 10-cm dishes: 3 μg of HA-ERK with or without 6 μg of dominant negative (DN)-Src or active Src or 7 μg of EGFR.

Short Interfering RNA

The siRNAs targeting the sequence in porcine GEF-H1 (AACAAGAGCATCACAGCCAAG) (13, 29) and canine EGFR (AAACTGCACCTATGGCTGTGA) were obtained from Applied Biosytems/Ambion Inc. (Austin, TX). Cells were transfected with 100 nm siRNA oligonucleotide using the LipofectamineTM RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Control cells were transfected with 100 nm Silencer siRNA negative control #2 (non-related siRNA) (Applied Biosytems/Ambion). Experiments were performed 48 h after transfection. The levels of GEF-H1 or EGFR were routinely checked by Western blotting.

Western Blotting

After treatment, cells were lysed on ice with cold lysis buffer (100 mm NaCl, 30 mm Hepes (pH 7.5), 20 mm NaF, 1 mm EGTA, 1% Triton X-100 supplemented with 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm PMSF, and protease inhibitors). For the detection of phosphoproteins the lysis buffer was also supplemented with the PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor. SDS-PAGE and Western blotting was performed as in Refs. 13 and 29. Briefly, blots were blocked in Tris-buffered saline containing 3% BSA and incubated with the primary antibody overnight. Antibody binding was visualized with the corresponding peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and the enhanced chemiluminescence method (kit from GE Healthcare). Where indicated, blots were stripped and reprobed to demonstrate equal loading or detect levels of GEF-H1 or EGFR. As the phospho-ERK (pERK) antibody proved difficult to strip, these blots were first developed using total ERK antibody followed by reprobing with pERK. Alternatively, in some cases the samples were run in duplicate; and one blot was developed for ERK and the other for pERK.

Preparation of GST-RBD and GST-RhoA(G17A) Fusion Proteins

GST-RBD (RhoA binding domain (RBD), amino acids 7–89 of Rhotekin) and GST-RhoA(G17A) beads were prepared as described (13, 33). Protein bound to the beads was estimated by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining, and the beads were kept at 4 °C for immediate use or stored frozen in the presence of glycerol.

RhoA Activity Assay

The amount of active RhoA was determined using an affinity precipitation assay with GST-RBD as in our earlier studies (13, 29). Briefly, confluent LLC-PK1 cells grown on 6- or 10-cm dishes were treated as indicated in the legends for Figs. 2–5. Cells were lysed with ice-cold Triton X-100 lysis buffer containing 100 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris base (pH 7.6), 20 mm NaF, 10 mm MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS, 1 mm Na3VO4, and protease inhibitors. After centrifugation, aliquots for determination of total RhoA were removed. The remaining supernatants were incubated at 4 °C for 45 min with 20–25 μg of GST-RBD beads followed by extensive washing. Total cell lysates and the RBD-captured proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using RhoA antibody. Results were quantified by densitometry, and the amount of active RhoA in each sample was normalized to the corresponding total RhoA. The data obtained in each experiment were expressed as -fold increase compared with the control active/total RhoA ratio, taken as unity.

FIGURE 2.

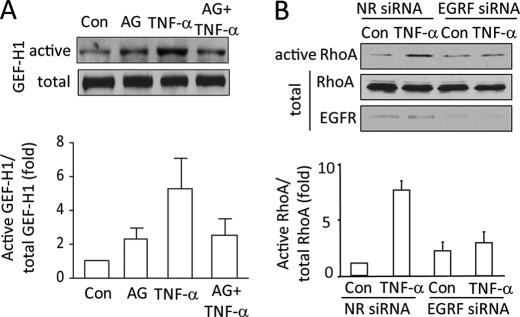

Inhibition of EGFR prevents TNF-α-induced GEF-H1 and RhoA activation. A, confluent LLC-PK1 cells were serum-depleted, then pretreated with 100 nm AG1478 (AG, 30 min) in serum-free DMEM followed by the addition of 10 ng/ml TNF-α for 10 min. Active GEFs were precipitated using GST-RhoA(G17A). GEF-H1 in the precipitates and total cell lysates (active and total, respectively) was detected by Western blotting. B, MDCK cells were transfected with NR siRNA or EGFR-specific siRNA. Forty-eight hours after transfection cells were treated with 10 ng/ml TNF-α (10 min), and active RhoA was captured using Rhotekin GST-RBD. RhoA in the precipitates (active) and total cell lysates was detected by Western blotting. The total cell lysates were redeveloped using an EGFR antibody. The blots were quantified by densitometry (see “Experimental Procedures”). The graphs below the blots show the mean ± S.E. from n = 3 independent experiments.

FIGURE 3.

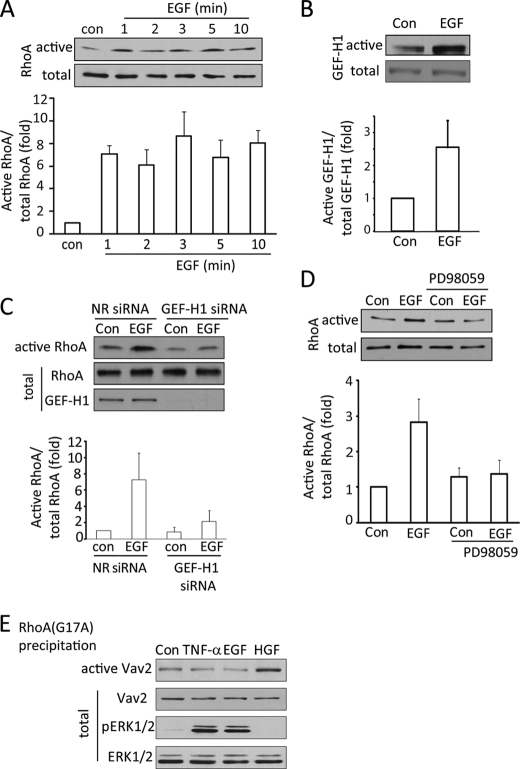

EGF activates the ERK/GEF-H1/RhoA pathway. A–D, LLC-PK1 cells were serum-depleted for 3 h. In C, 48 h before the experiment, cells were transfected using NR or GEF-H1-specific siRNA. The cells were exposed to 10 ng/ml EGF for the indicated times (A) or 1 min (B) or 10 min (D) or 2 min (C). In D, cells were treated with 10 μm PD98059 before and during stimulation with EGF. At the end of the treatments cells were lysed, and the amount of active RhoA (A, C, and D) or GEF-H1 (B) was detected and analyzed as described earlier. The graphs below the blots show data from the densitometric analysis (mean ± S.E. n = 3). E, LLC-PK1 cells were serum-depleted and treated using 10 ng/ml TNF-α (10 min) or 100 ng/ml EGF (10 min) or 10 ng/ml HGF (30 min). Cells were lysed, and active GEFs were precipitated using RhoA(G17A) as in B. Vav2 in the precipitates or cell lysates (active and total, respectively) were detected by Western blotting. The total cell lysates were redeveloped to detect pERK and ERK levels.

FIGURE 4.

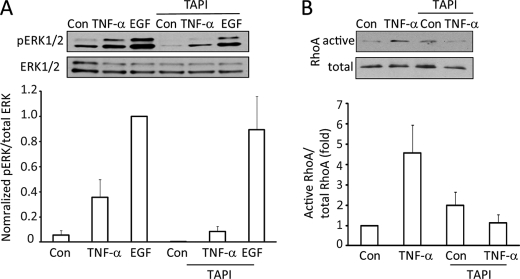

The TACE inhibitor TAPI-1 prevents TNF-α-induced ERK and RhoA activation. LLC-PK1 cells were treated for 15 min with 10 μm TAPI-1 before the addition of TNF-α or EGF (10 ng/ml, 10 min). pERK (A) or active RhoA (B) levels were detected and quantified as described earlier. In A the maximal effect (EGF-induced pERK) was taken as 100%, as the control (untreated) values in some experiments were too close to the background.

FIGURE 5.

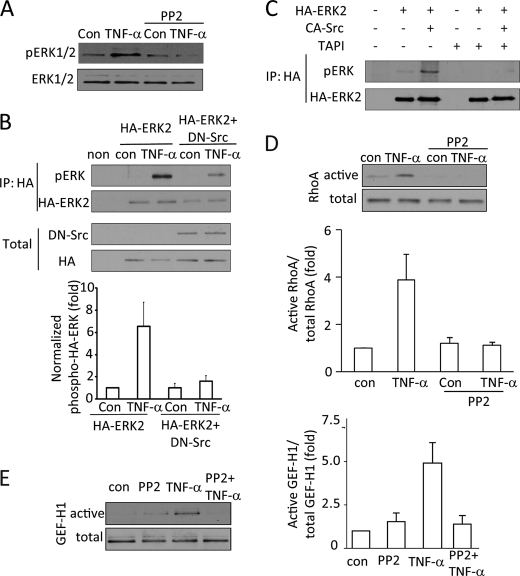

Src kinase mediates TNF-α-induced ERK, GEF-H1, and RhoA activation. A, D, and E, LLC-PK1 cells were pretreated with 10 μm Src family inhibitor PP2 (15 min) followed by 10 ng/ml TNF-α for 5 min. The inhibitor was present during the TNF-α treatment. Levels of pERK (A), RhoA (D), or GEF-H1 (E) were determined as described earlier. B and C, LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with HA-tagged ERK2 with or without dominant negative Src kinase (B) or active Src kinase (C). Forty-eight hours after transfection the cells were treated with TNF-α (10 ng/ml, 10 min) as indicated. In C, cells were pretreated for 1 h with TAPI-1 as indicated before the addition of TNF-α. At the end of the treatment the cells were lysed, and HA-ERK2 was immunoprecipitated (IP). Phospho-ERK was detected in the precipitates. The blots were stripped and redeveloped using an HA-antibody to detect precipitated HA-ERK2. In B, the transfected HA-ERK2 and avian dominant negative Src were also detected in the total cell lysates. Please note that the avian Src antibody does not react with mammalian Src. In the experiments shown on C neither the transfected HA-ERK nor the avian Src was detectable in the total cell lysates (not shown). No signal was visible when untransfected cell lysates are used (non). The graph in B shows densitometric analysis done as described under “Experimental Procedure” (mean ± S.E. n = 3).

Affinity Precipitation of Activated GEFs

Active GEFs were precipitated from cell lysates using the RhoA(G17A) mutant that cannot bind nucleotide and, therefore, has high affinity for GEFs (30) as in our earlier works (13, 29). GEF-H1 or Vav2 in the precipitates were detected by Western blotting. Precipitation with glutathione-Sepharose beads, containing no fusion proteins, resulted in no GEF-H1 precipitation (13). The GEFs in total cell lysates were also detected for each sample (total GEF-H1 or Vav2). Blots were quantified by densitometry. The amount of active GEF-H1 in each sample was normalized to the corresponding total GEF-H1, and the data obtained in each experiment were expressed as -fold increase compared with the control active/total GEF-H1 ratio taken as unity.

Immunoprecipitation

To assess EGFR phosphorylation, LLC-PK1 cells transfected with human EGFR were treated with TNF-α or EGF and inhibitors as indicated in the figure legends in serum-free DMEM. At the end of the treatment the cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed using radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (Triton X-100 lysis buffer supplemented with 0.1% SDS and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate). Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation (12,000 rpm for 5 min). Total cell lysate samples were removed from the supernatant, and the rest of the supernatant was precleared using A/G-agarose beads. Next, the lysates were incubated with anti-EGFR (0.8 μg/sample) or anti-Tyr(P) (2 μg/sample) antibody for 1 h at 4 °C under constant rotation. The antibodies were captured using 25 μl of A/G-agarose beads for 1 h at 4 °C. After washing 3 times with Triton X-100 lysis buffer supplemented with 1 mm Na3VO4, the precipitated proteins were eluted by boiling for 5 min in Laemmli sample buffer. The precipitated proteins and the total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting.

To assess phosphorylation of HA-ERK2, LLC-PK1 cells in 10-cm dishes were transfected with HA-ERK2 with or without DN-Src or active Src. Forty-eight hours later the cells were serum-depleted and treated as indicated in the corresponding figure legends. Cells were lysed as above, and HA-tagged ERK was precipitated using 20 μl of HA-antibody coupled to agarose beads for 1 h at 4 °C. The precipitates were washed and eluted as described above. Samples were subjected to Western blot analysis, and membranes were probed with anti-phospho-ERK followed by anti-HA. In control experiments, lysates from non-transfected cells were used to verify the specificity of the immunoprecipitation.

For all immunoprecipitation experiments, results were quantified by densitometry, and the Tyr(P) or pERK signal in each sample was normalized to the corresponding total precipitated amount of the proteins. Data obtained in each experiment were expressed as -fold increase compared with the level of the control ratio taken as unity.

Electric Cell-Substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS)

The ECIS technology (Applied Biophysics, Troy, NY) was used to follow cell growth and establishment of the epithelial monolayer, as described in Refs. 34 and 35. This method follows electrical parameters of cells grown on small gold-film electrodes. Changes in impedance and capacitance to AC current flow at different frequencies are measured. Attachment, spreading, and growth of cells on the electrodes cause and increase in impedance measured at 500 Hz and decrease in the capacitance at 40 kHz. For the measurements, MDCK cells were trypsinized and counted using the Countess® Automated Cell Counter (Invitrogen). The cells were then inoculated into the wells of an 8W10E+ electrode array (Applied Biophysics) at 4 × 105 cells/well in a volume of 400 μl with the following treatments as indicated: 20 ng/ml TNF-α, 100 nm AG1478, or their combination. Resistance and capacitance data were collected continuously for 12 h using the frequency scan mode. Each treatment was done in duplicate. The obtained curves were normalized to the first point using the ECIS software. For further analysis of the capacitance data, the time points corresponding to a 75% drop in the capacitance (0.25 point on the normalized capacitance curve) for each sample were determined, and data from similar treatment conditions were averaged.

BrdU Incorporation Cell Proliferation Assay

A BrdU Cell Proliferation Assay kit from Exalpha Biologicals (Shirley, MA) was used. MDCK cells were trypsinized, counted using the Countess® Cell Counter, and plated on 96-well plates (2 × 104/well) using serum-containing culture medium. After allowing 2 h for the cells to adhere, the medium was replaced with serum-free medium overnight. Next, cells were stimulated by 100 ng/ml EGF or10 ng/ml TNF-α for 24 h. BrdU was added for the last 6 h. BrdU incorporation was quantified according to the manufacturer's instruction using a SpectraMax Plus384 microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices) at 450 nm.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Confluent cells grown on coverslips were treated as indicated in the legend for Fig. 7 followed by fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde. Immunofluorescence staining was carried out as in Refs. 13 and 29. Briefly, after permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100, the coverslips were blocked with 3% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline. Next, cells were incubated with anti-p65 NFκB (1:100). Bound antibody was detected using the corresponding fluorescent secondary antibody (1:1000). DAPI was used to counterstain nuclei. All samples were viewed using an Olympus IX81 microscope (Melville, NY) coupled to an Evolution QEi Monochrome camera (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD) controlled by the QED InVivo Imaging software.

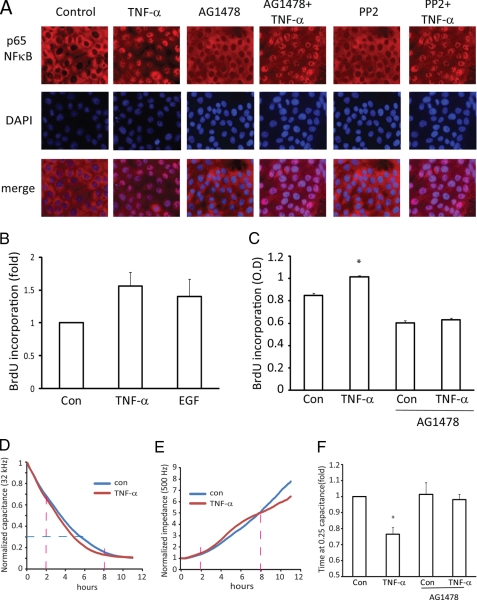

FIGURE 7.

A, TNF-α activation of NFκB is independent of Src and EGFR. LLC-PK1 cells grown on coverslips were pretreated with 100 nm AG1478 or PP2 for 30 min followed by 10 ng/ml TNF-α for 30 min. The cells were fixed and permeabilized, and p65 NFκB was visualized by immunostaining with anti-p65 and CY3-coupled secondary antibody. The nuclei were counterstained using DAPI. The pictures show p65 (red) and DAPI (purple) staining of the same field as well as the merged image. B and C, TNF-α enhances proliferation through the EGFR. MDCK cells were plated in 96-well plates, serum-depleted overnight, and then exposed to 10 ng/ml TNF-α or 100 ng/ml EGF for 24 h. DNA synthesis was assessed using a BrdU incorporation assay as described under “Experimental Procedures.” In each experiment the BrdU signal in the control cells were taken as 1, and-fold changes were calculated. B shows data from n = 4 independent experiments performed in triplicate. C shows data of a typical experiment performed in 6 parallel determinations. In C, the asterisk indicates that the column is significant versus control (p < 0.05). D–F, shown is the effect of TNF-α on epithelial cell growth measured using ECIS. Changes in the capacitance (D) and impedance (E) were followed using ECIS as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Curves represent the averages of the duplicate measurements. D and E show capacitance and resistance data of the same measurement, respectively. All curves were normalized to the first obtained point. The red dashed lines on D and E indicate the 2 and 8 h time points, and the blue dashed lines indicate the 0.25 capacitance point. F summarizes data from capacitance measurements. In each measurement the time required for a 75% drop in the capacitance (0.25 value on the normalized capacitance curve) was determined and expressed as -fold change compared with the control in the same experiment taken as 1. The graph shows data from n = 8 curves obtained in 4 independent experiments (mean ± S.E., n = 8). The asterisk indicates p < 0.01 versus control.

Protein Assay

Protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce) with BSA used as standard.

Densitometry

Films with non-saturated exposures were scanned, and densitometry analysis was performed using a GS-800 calibrated densitometer and the “band analysis” option of the Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

Statistical Analysis

All shown blots are representatives of at least three similar experiments. Data are presented as the means ± S.E. of the number of experiments indicated (n). Statistical significance was calculated with the Wilcoxon non-parametric test or one-way analysis of variance as appropriate using GraphPad Instat.

RESULTS

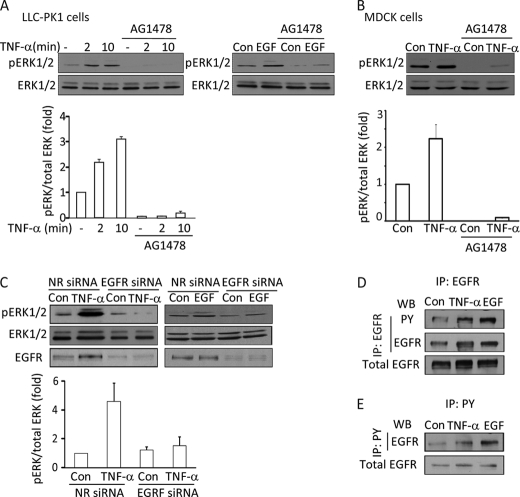

TNF-α-induced ERK Activation Requires the EGFR

The MAP kinases ERK1 and -2 play a key role in TNF-α-induced activation of the Rho exchange factor GEF-H1 in tubular cells (13). However, the upstream mechanism whereby TNF-α activates ERK in this pathway is not known. As the EGFR is a strong activator of ERK, we investigated whether it has a role in TNF-α-induced ERK activation. Levels of phospho-ERK1 and -2 in LLC-PK1 and MDCK tubular cells were followed by Western blotting using a pERK-specific antibody. In accordance with our earlier studies, treatment of cells using 10 ng/ml TNF-α induces rapid ERK1/2 phosphorylation in both LLC-PK1 and MDCK cells (Fig. 1, A and B). Interestingly, MDCK cells consistently exhibit higher basal pERK levels, and therefore, the effect of TNF-α is somewhat smaller in these cells. To test the role of the EGFR, we treated the cells with the specific EGFR inhibitor AG1478. As shown in Fig. 1, A and B, 100 nm AG1478 abolished the effect of TNF-α on ERK phosphorylation in both cell types. As expected, the inhibitor also prevented EGF-induced ERK activation (Fig. 1A, right panel). To rule out nonspecific effects of AG1478 and substantiate the finding that EGFR is required for TNF-α-induced ERK activation, we also used a non-pharmacological approach. We designed a short interfering RNA (siRNA) against the canine EGFR. Fig. 1C demonstrates that transfection of MDCK cells with the EGFR-specific siRNA caused a substantial reduction in the level of the EGFR. Lack of a functional EGFR was also substantiated by the absence of EGF-induced ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 1C, right panel). Importantly, TNF-α failed to induce ERK phosphorylation in cells treated with the EGFR siRNA (Fig. 1C, left panel), verifying results obtained with the inhibitor.

FIGURE 1.

Inhibition of the EGFR prevents TNF-α-induced ERK activation. A and B, LLC-PK1 (A) or MDCK (B) cells were grown to confluence and serum-depleted for 3 h before the treatments. The cells were pretreated with 100 nm AG1478 for 30 min in serum-free DMEM followed by the addition of 10 ng/ml TNF-α for 2 or 10 min (A) or 10 min (B) or 100 ng/ml EGF for 10 min as indicated. Where used, the inhibitor was present throughout the TNF-α or EGF treatment. At the end of the treatments the cells were lysed, and pERK and ERK were detected using Western blotting. C, MDCK cells were transfected with NR siRNA or an siRNA against canine EGFR. Forty-eight hours after transfection the cells were serum-depleted and then treated with 10 ng/ml TNF-α (5 min) or 100 ng/ml EGF (10 min). ERK and pERK were detected as above. The graphs below the blots summarize densitometric analysis of the pERK blots (see “Experimental Procedures”). Data presented are the mean ± S.E. of n = 3 experiments. D and E, LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with human EGFR. 48 h later the cells were serum-depleted and treated with 10 ng/ml TNF-α (15 min) or 10 ng/ml EGF (5 min). At the end of the treatment cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated (IP) using EGFR (D) or phosphotyrosine (PY) (E) antibody as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The immunoprecipitated proteins and samples of the total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting (WB) using Tyr(P) and EGFR antibodies as indicated. In D the transfected EGFR in the total cell lysates was also visualized. The EGFR antibody in the total cell lysates and precipitates from untransfected cells yielded only a marginal signal (not shown).

TNF-α Enhances EGFR Tyrosine Phosphorylation

The above data suggest that TNF-α might exert its effect on ERK by transactivating the EGFR. To demonstrate that TNF-α indeed activates the EGFR, we next asked whether TNF-α-promotes EGFR phosphorylation. The levels of endogenous EGFR in LLC-PK1 and MDCK cells are low, and various phospho-EGFR antibodies in our hands failed to detect reliably even the EGF-induced EGFR phosphorylation. Similarly, we were not able to consistently immunoprecipitate the endogenous protein. Therefore, to overcome this problem, we transiently transfected LLC-PK1 cells with a human EGFR construct and then immunoprecipitated the expressed protein and detected its tyrosine phosphorylation using a phosphotyrosine antibody. As shown in Figs. 1D and 6, D–F, in unstimulated cells the precipitated EGFR showed a small but clearly detectable tyrosine phosphorylation. Importantly, exposure of the cells to TNF-α for 15 min significantly enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation of the EGFR. To verify the specificity of the observed signal, we performed the reverse immunoprecipitation using the phosphotyrosine antibody and then detected EGFR in the precipitates. In untreated cells the phosphotyrosine antibody precipitated only a marginal amount of EGFR (Fig. 1E). In contrast, EGFR was well detectable in the precipitates when lysates from TNF-α- or EGF-treated cells were used. These data, therefore, verify that the EGFR is activated in tubular cells stimulated with TNF-α.

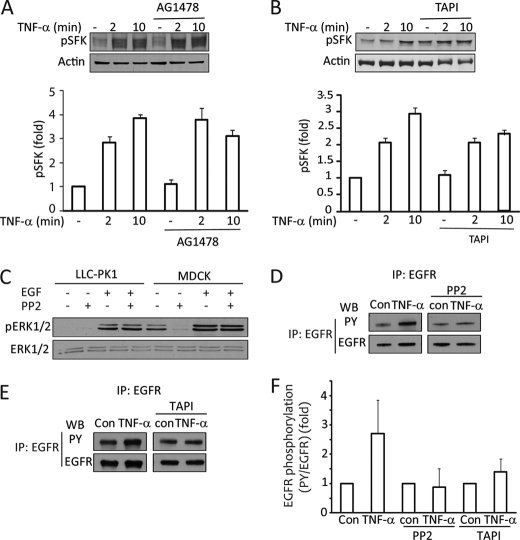

FIGURE 6.

A and B, TNF-α-induced Src activation is upstream of the EGFR and TACE. LLC-PK1 cells were treated with 100 nm AG1478 (A) or 10 μm TAPI-1 (B) before the addition of 10 ng/ml TNF-α for the indicated times. The cell lysates were probed using a phospho-SFK antibody. This antibody detects all Src family kinases phosphorylated at Tyr-416 (corresponding to activated SFK). The graph summarizes densitometric quantification (mean ± S.E. of n = 3 experiments). Actin was used to verify equal loading, as the total SFK antibody did not react with Src kinases in LLC-PK1 cells. C, EGF-induced ERK activation is independent of Src kinases. LLC-PK1 and MDCK cells were treated with PP2 and EGF as indicated, and pERK was detected as described earlier. D–F, TNF-α-induced EGFR activation requires Src and TACE. LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with EGFR. Cells were treated as indicated. EGFR was immunoprecipitated (IP), and phosphotyrosine (PY) and EGFR were detected as in Fig. 1. The graph in F shows densitometric analysis of three independent experiments, performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” In each experiment the normalized phosphorylation was expressed as -fold increase from the corresponding untreated sample or the sample treated with TAPI-1 or PP2 alone. The blots shown in D and E are from the same experiment run on the same gel (D) or on separate gels (E). WB, Western blot.

TNF-α-induced GEF-H1 and RhoA Activation Is Mediated by the EGFR

We have previously shown that ERK mediates TNF-α-induced activation of the Rho exchange factor GEF-H1 (13). Having found that the TNF-α-induced ERK activation requires the EGFR, we next asked whether GEF-H1 activation is also downstream of the EGFR. To follow GEF-H1 stimulation, we used a precipitation assay as in our earlier studies (13, 29). Active GEFs were precipitated from cell lysates using a GST-tagged RhoA mutant (RhoA(G17A). This mutant does not bind nucleotides (“nucleotide free” mutant) and has a high affinity for activated GEFs (30). Precipitated GEF-H1 was visualized by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 2A, as described by us earlier, TNF-α induced an ≈5-fold increase in the amount of GEF-H1 precipitated by RhoA(G17A) corresponding to activation of GEF-H1 (13). Importantly, the TNF-α-elicited activation of GEF-H1 was prevented by the EGFR inhibitor AG1478 (Fig. 2A).

To further substantiate the role of the EGFR in the TNF-α-induced activation of the ERK/GEF-H1/RhoA pathway, we next investigated the effect of EGFR down-regulation on TNF-α-stimulated RhoA activation. RhoA activation was followed using a GST-RBD precipitation assay as earlier (13, 29). As expected, TNF-α induced potent RhoA activation (Fig. 2B). Importantly, the TNF-α-induced RhoA activation was also prevented by down-regulation of the EGFR (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these data verify that the TNF-α-induced activation of the ERK/GEF-H1/RhoA pathway requires the activity of the EGFR.

EGF Activates the ERK/GEF-H1/RhoA Pathway

The mechanisms involved in EGF-induced RhoA activation and the exchange factor(s) mediating the effect are not well defined. The data presented above point to a potential role of GEF-H1 in EGF-induced RhoA activation. To verify this, we next explored the effect of direct stimulation of the EGFR using EGF. Exposure of LLC-PK1 cells to 100 ng/ml EGF elicited rapid RhoA activation (Fig. 3A). An increase in RhoA activity was detected as early as 1 min after EGF addition and remained high for the time period studied (10 min). Similar to RhoA, GEF-H1 activation was also detected after 1 min of EGF stimulation (Fig. 3B).

Having shown that EGF activates GEF-H1, we next wished to verify that GEF-H1 is indeed a critical mediator of EGF-induced RhoA activation. To this end, GEF-H1 was down-regulated in LLC-PK1 cells as in our earlier studies using a specific siRNA (13, 29). Cells treated with non-related (NR) or GEF-H1-specific siRNA were challenged with EGF, and RhoA activity was determined using the RBD precipitation assay. As Fig. 3C demonstrates, EGF induced ≈7-fold RhoA activation in NR siRNA-treated cells. Importantly, the absence of GEF-H1 nearly abolished the EGF-induced RhoA activation. This verifies that GEF-H1 is critical for EGF-induced RhoA activation.

Next we wished to explore the upstream mechanism of GEF-H1 activation by EGF by assessing the role of the MEK/ERK pathway. Cells were treated with the MEK inhibitor PD98059, and EGF-induced RhoA activation was tested. As shown in Fig. 3D, the MEK inhibitor prevented RhoA activation upon EGF stimulation.

In a recent publication Vav2 was implicated in EGFR-mediated RhoA activation in mesangial cells (36). This prompted us to ask whether Vav2 is also activated in tubular cells by EGF or TNF-α. To assess Vav2 activation, we again used the RhoA(G17A) precipitation assay. As shown in Fig. 3E, in unstimulated LLC-PK1 cells a small but well detectable amount of Vav2 is precipitated by RhoA(G17A), likely corresponding to basal Vav2 activity. The precipitated amount of Vav2, however, remained unchanged when cells were stimulated by TNF-α or EGF. In contrast, HGF, a known stimulator of Vav2 (37), significantly increased the levels of active Vav2. In contrast to TNF-α and EGF, which caused marked ERK activation, HGF did not elevate pERK levels (Fig. 3E). Therefore, Vav2 in tubular cells is not regulated by EGF or TNF-α. Moreover, HGF is not an activator of the MEK/ERK pathway, and in contrast to GEF-H1, Vav2 regulation seems to be independent of pERK.

TNF-α-induced ERK and RhoA Activation and EGFR Phosphorylation Are Mediated by TACE

The above data point to a key role for TNF-α-induced EGFR transactivation in ERK/GEF-H1/RhoA activation. TACE was shown to be involved in EGFR activation induced by a large variety of stimuli (for review, see Ref. 26). Upon activation, TACE releases EGFR ligands, which in turn stimulate the EGFR. We considered a similar mechanism in the TNF-α-induced EGFR activation. To study the role of TACE, we used its specific inhibitor, TAPI-1. As shown in Fig. 4A the TNF-α-induced elevation in pERK levels was fully prevented in cells treated with TAPI-1. In contrast, a marked elevation in the pERK levels was detectable after the addition of EGF, showing that direct stimulation of the EGFR does not require TACE action. These findings are consistent with TACE mediating the release of EGFR ligands upon TNF-α addition. Similar to ERK activation, the TNF-α-promoted RhoA activation was also prevented by TAPI-1 (Fig. 4B).

Finally, we also tested the involvement of TACE in TNF-α-induced EGFR phosphorylation. Similar to the experiments presented on Fig. 1, LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with human EGFR, and the protein was immunoprecipitated and tested for tyrosine phosphorylation. The TNF-α-enhanced EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation was potently reduced in the presence of the TACE inhibitor (see Fig. 6, E and F). Taken together, these data verify that TNF-α transactivates the EGFR through TACE.

TNF-α-induced ERK and RhoA Activation Is Src-dependent

To gain further insight into the mechanism of TNF-α-induced regulation of GEF-H1 and RhoA, we next considered a potential role for the SFK. Src kinases have been implicated in EGFR transactivation by various stimuli (26). On the other hand, they are also important downstream effectors of the EGFR. Indeed, similar to other cell types, SFKs were rapidly activated by TNF-α, as shown by Western blotting using an activation-specific phospho-Src antibody (Fig. 6, A and B). This antibody recognizes the active form of all SFKs. When LLC-PK1 cells were stimulated with TNF-α, the phospho-SFK antibody visualized multiple bands, likely corresponding to different members of the Src family (Fig. 6, A and B).

To test the role of the SFKs, we first used their specific inhibitor, PP2. PP2 abolished TNF-α-induced ERK activation (Fig. 5A). To further substantiate the role of Src kinases and to verify that the observed inhibition is not due to a nonspecific effect of PP2, we next used a kinase dead, DN avian Src kinase. The efficiency of transient transfection is relatively low, and therefore, the effect of the expressed protein is masked by a signal from non-transfected cells. To overcome this issue and to enhance the signal from the transfected cells, we used an HA-tagged ERK2 that was transfected alone or together with the DN-Src protein. We have previously shown that under the used transfection conditions proteins show high co-expression (e.g. Ref. 38). Forty-eight hours after transfection, HA-ERK2 was precipitated through the tag from lysates of untreated or TNF-α-treated cells. The precipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with a pERK antibody. As shown in Fig. 5B, precipitated HA-ERK2 showed a small but well detectable basal phosphorylation. The pERK signal was significantly enhanced in TNF-α-treated cells. Importantly, cotransfection with the DN-Src reduced both the basal phosphorylation and the TNF-α-induced increase in pERK.

Having shown that Src activity is necessary for TNF-α-induced ERK activation, we next asked whether activation of Src is sufficient to promote ERK phosphorylation. To test this, we expressed an active avian Src along with HA-ERK2 and tested the phosphorylation of the precipitated ERK. As shown in Fig. 5C, active Src induced a well detectable increase in pERK (compare pERK levels in second and third lanes).

Finally, we also tested the requirement of SFKs for TNF-α-induced RhoA and GEF-H1 activation. Fig. 5D demonstrates that treatment of the cells with PP2 eliminates TNF-α-induced RhoA activation. Similarly, TNF-α-elicited GEF-H1 activation was prevented by the Src family inhibitor (Fig. 5E). Taken together, these data demonstrate that Src has a key role in mediating TNF-α-induced activation of the ERK/GEF-H1/RhoA pathway.

Src Kinase Is Upstream of the EGF Receptor

Although Src kinases have been implicated in EGFR transactivation by various stimuli (26), Src is also an important downstream effector of the EGFR (39). Therefore, we next asked whether the observed Src activation in TNF-α-stimulated cells is upstream or downstream of the EGFR. We first tested whether TNF-α activates SFK through the EGFR. Cells were exposed to TNF-α in the presence of the EGF receptor inhibitor AG1478. As demonstrated in Fig. 6A, AG1478 failed to prevent SFK activation induced by TNF-α. Similarly, when TACE activity was blocked using TAPI-1, TNF-α could still cause efficient SFK activation (Fig. 6B). We also tested whether EGF stimulation requires Src to activate ERK. Fig. 6C shows results obtained using LLC-PK1 (first 4 bands) and MDCK cells (last 4 bands). EGF-induced ERK activation in both cells was completely unaffected by PP2. As mentioned earlier, MDCK cells exhibit higher basal ERK activity. Interestingly, this basal ERK phosphorylation is completely eliminated by PP2. However, EGF enhances pERK levels even in PP2-treated cells. Therefore, EGF does not induce ERK activation through Src kinases.

These data imply that Src acts upstream of the EGFR. We next examined the role of SFKs in the TNF-α-promoted EGFR phosphorylation. EGFR phosphorylation was tested as described earlier using immunoprecipitation and phosphotyrosine Western blots of transfected human EGFR. As shown earlier, TNF-α enhanced the tyrosine phosphorylation of the EGFR (Fig. 6, D and F). However, when the cells were treated with PP2, TNF-α was no longer able to enhance EGFR phosphorylation (Fig. 6, D and F).

Finally, we also asked whether active Src indeed requires TACE for enhancing ERK activation. As shown on Fig. 5C, active Src failed to induce ERK phosphorylation when cells were pretreated with the TACE inhibitor TAPI-1 before TNF-α, suggesting that the effect of active Src is indeed mediated by TACE. Taken together, we have shown that Src kinases are required for the TNF-α-induced EGFR transactivation and act upstream of the EGFR.

TNF-α-induced Activation of NFκB Is Independent of the EGFR

We next wished to assess the functional significance of the cross-talk between the TNF-EGFR signaling. TNF-α is a potent activator of the early inflammatory transcription factor NFκB. Moreover, in fibroblasts and airway epithelia, the EGFR or Src were found to mediate TNF-α-induced NFκB activation (40, 41). Activation of NFκB involves its translocation to the nucleus, which was detected using immunofluorescent staining of the p65 subunit. As shown on Fig. 7A, TNF-α addition for 30 min causes potent nuclear accumulation of p65. This nuclear accumulation, however, was unchanged by AG1478 or PP2 (Fig. 7A). These observations suggest that NFκB activation is not mediated by the Src/EGFR pathway and point to the existence of EGFR-dependent and independent TNF-α effects in tubular epithelium.

TNF-α Stimulates Cell Proliferation through the EGFR

The EGFR transmits key proliferative signals. TNF-α on the other hand is a well known inducer of apoptosis. Interestingly, in a number of cells TNF-α was shown not to induce apoptosis but, rather, to enhance survival and proliferation (e.g. Refs. 9, 22, and 42). Therefore, we asked, whether TNF-α can enhance proliferation of the tubular cells through the EGFR. To detect changes in cell proliferation, we used two methods; the BrdU incorporation assay and ECIS. First, we measured DNA synthesis in dividing cells by detecting the incorporation of the thymidine analog BrdU using an immunochemical BrdU detection kit. BrdU is incorporated into the newly synthesized DNA strands in actively proliferating cells. MDCK cells were deprived of serum overnight to reduce basal proliferation followed by the addition of either TNF-α or EGF. As shown on Fig. 7B, stimulation of cells with 10 ng/ml TNF-α induced a >50% increase in BrdU incorporation. This effect was not increased further by elevating TNF-α concentration (not shown). The addition of 100 ng/ml EGF resulted in a similar elevation in BrdU incorporation (Fig. 7B). Next, we tested the effect of AG1478. As shown in Fig. 7C, the EGFR inhibitor caused a slight reduction in the basal BrdU incorporation. Importantly, TNF-α did not enhance BrdU incorporation in the presence of AG1478, showing that its effect on proliferation indeed requires the EGFR.

TNF-α Enhances the Development of the Monolayer as Measured Using ECIS

To further analyze the effect of TNF-α and EGFR on epithelial cell growth, we used ECIS. This technique enables accurate and real time monitoring of the formation of an epithelial monolayer (43). MDCK cells were seeded in wells containing gold electrodes, and changes in impedance and capacitance to AC current flow at different frequencies were measured. The changes occurring after seeding MDCK cells in ECIS arrays have been well characterized (34, 43). High frequency capacitance measurements (32 kHz and higher) are sensitive to changes in cell attachment, spreading, and growth on the electrode, and therefore, this parameter is a good measure of the coverage of the electrode by cells, as it decreases approximately linearly with increasing surface coverage. The early phases of the low frequency resistance measurements (500 Hz) are also sensitive to cell growth, whereas later phases, when the cells reach confluence, reflect the development and maturation of the tight junctions (34, 35). Fig. 7, D and E, demonstrate the changes in the capacitance and impedance, respectively, during a typical ECIS measurement. The early changes (decrease in the capacitance and increase in impedance) detected using the TNF-α-treated and untreated cells do not show significant differences, suggesting that the adhesion and early spreading processes are not affected by TNF-α. MDCK cells attach and spread on the electrodes in the first 2–3 h (44). Interestingly, after 2 h (indicated by the red dashed lines on the graphs in Fig. 7, D and E), the TNF-α-treated samples show a faster drop in capacitance and rise in impedance than the untreated samples, suggesting that the growth phase is enhanced by TNF-α. Finally, at around 8 h after seeding, the capacitance reaches its minimum, indicating full coverage of the electrode. To study whether EGFR is involved in the observed effect of TNF-α, we performed measurements using untreated cells or cells treated with TNF-α, AG1478, or the combination of these. The graph in Fig. 7F summarizes the time required to reach a 75% drop in the capacitance for each condition (indicated by the blue dashed line on the graph in Fig. 7D). TNF-α treatment caused an ≈20% reduction in the time required to reach this level of capacitance, suggesting that the proliferation of the cells was indeed enhanced. Importantly, this effect was prevented by the EGFR inhibitor (Fig. 7E). Taken together, these data suggest that TNF-α, through the EGFR, can enhance proliferation of the epithelial layer, leading to faster establishment of the monolayer.

DISCUSSION

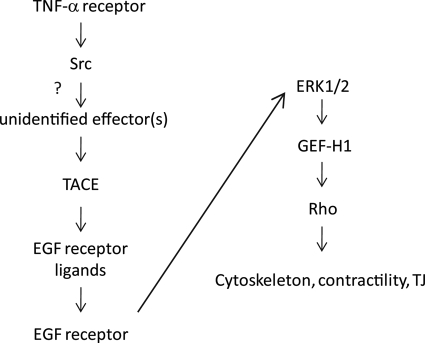

The aim of the current study was to further our understanding of the mechanisms through which TNF-α affects tubular epithelia. The major novel findings of this study are the following. 1) We have shown that TNF-α activates the ERK/GEF-H1/RhoA pathway in tubular cells through Src- and TACE-dependent EGFR activation. 2) We have identified GEF-H1 as the exchange factor mediating EGF-induced RhoA activation. Finally, 3) we have demonstrated that TNF-α enhances proliferation through the EGFR, whereas activation of NFκB is independent of the EGFR. Fig. 8 summarizes the proposed mechanism of TNF-α-induced RhoA activation.

FIGURE 8.

Proposed mechanism of the TNF-α-induced activation of the ERK/GEF-H1/RhoA pathway.

A number of studies including our own have shown that TNF-α modulates the cytoskeleton through the activation of the Rho family small GTPases Rac, RhoA, and Cdc42 (13, 45–49). In our earlier work we have identified GEF-H1 as the exchange factor mediating TNF-α-induced RhoA activation and showed that GEF-H1 is activated through ERK-mediated phosphorylation. This mechanism, therefore, connects the MEK/ERK and Rho pathways and places ERK upstream of RhoA.

TNF-α signaling has been extensively studied. Stimulation of the TNF receptors initiates a complex signaling mechanism involving a number of adapter proteins (1, 16, 19). Activation of NFκB, JNK, and p38 requires the formation of a protein complex that binds to the death domain of the receptor consisting of the adapter proteins TNFR-associated death domain protein (TRADD), receptor interacting protein (RIP), and death domain- and TNF receptor associated factor (TRAF). On the other hand, activation of caspases and apoptosis is mediated through the Fas-associated death domain (FADD) protein that binds to the death domain of the receptor and recruits the initiator caspase-8. Interestingly, in fibroblasts TNF-α-induced ERK activation was dependent on the FADD-caspase-8 pathway and required the presence of the death domain in the TNFR1 (50). However, the mechanism of Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway activation is less explored in tubular cells (for review, see Ref. 16). Here we propose a novel mechanism for TNF-α-induced ERK activation in tubular epithelium; our data place Src, TACE and the EGFR upstream of ERK.

Transactivation of the EGFR is emerging as a common theme in the action of a large variety of extracellular stimuli, including G-protein-coupled receptor ligands (e.g. angiotensin II and thrombin) and physical stimuli (e.g. hyperosmolarity, reactive oxygen species) (26, 51). All are acting through enzymes of the ADAM family that release EGFR ligands. Transactivation of the EGFR by TNF-α has also been shown in a variety of cells, including intestinal and airway epithelia, hepatocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial and smooth muscle cells (21, 23, 24, 40, 52–54). In this study we show that ADAM17/TACE mediates some of the effects of TNF-α in tubular epithelium. The mechanism whereby TNF-α activates TACE remains to be determined. TACE can be regulated by phosphorylation. Indeed, the kinases p38, ERK, and PDK1 have been shown to phosphorylate and activate TACE (55–57). In addition, Src was also implicated in TACE regulation (see below). Although our findings place ERK downstream and not upstream of TACE, the potential role of phosphorylation in mediating TNF-α-induced TACE activation remains to be established.

Our finding that Src mediates ERK and RhoA activation is in line with earlier studies that showed that Src mediates TNF-α-induced actin remodeling in macrophages (58) and ERK activation in keratinocytes and fibroblasts (59, 60). The potential involvement of Src in GEF-H1 regulation, however, has not been evaluated. As the TNF-α-induced RhoA and GEF-H1 activation are potently prevented by SFK inhibition, we considered that GEF-H1 might be directly regulated by Src. However, we were not able to detect tyrosine phosphorylation of GEF-H1 or co-precipitation of GEF-H1 and Src (not shown.). Instead, our data point to a more indirect role of Src in GEF-H1 regulation through the promotion of EGFR transactivation. Src inhibition prevents TNF-α-stimulated EGFR phosphorylation. Moreover, expression of an active Src was sufficient to enhance ERK phosphorylation. These findings suggest a central role for Src in mediating TNF-α-induced EGFR activation. Two possible mechanisms could account for the role of Src. Src is known to directly phosphorylate and activate the EGFR (32). Although we cannot rule out the existence of such an effect in our case, prevention of the TNF-α-induced EGFR phosphorylation and signaling by a TACE inhibitor as well as the inhibition of the Src-induced ERK phosphorylation by the same inhibitor argues against a direct activation of the EGFR by Src. Instead, it is likely that Src is upstream of TACE and is required for its activation. The mechanisms through which TNF-α-induced Src activation leads to enhanced TACE activity, however, are unknown. Using immunoprecipitation of an HA-tagged TACE followed by phosphotyrosine or Src Western blotting, we did not find evidence for basal or TNF-α-induced TACE tyrosine phosphorylation or for co-precipitation of Src and TACE (not shown). These findings suggest that Src activates TACE through an indirect mechanism. Such a conclusion is in line with previous findings showing that gastrin releasing peptide activates TACE through Src-dependent activation of PI3K and phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1), which in turn phosphorylates TACE on serine and threonine (57). Furthermore, while this manuscript was under review, a study by Maretzky et al. (61) reported that oncogenic (constitutively active) Src enhances TACE-mediated shedding, and this effect does not require the cytoplasmic tail of TACE that harbors the potential phosphorylation sites. Taken together, Src is likely to activate TACE through an indirect mechanism (see Fig. 8). The uncovering of the molecular events connecting Src and TACE in TNF-α-stimulated tubular cells, however, will require future studies.

The upstream steps of Src activation in tubular cells remain to be established. Interestingly, Src was shown to bind directly to the p55 TNF receptor and could, therefore, potentially act as a signal initiator (62). An alternative possibility is suggested by the findings that ceramide production and the neutral sphingomyelinase are required for TNF-α-induced ERK activation and small GTPase-mediated stress fiber formation (63, 64). Interestingly sphingomyelinase was also shown to bind to the TNFR. Moreover, sphingomyelinase can mediate Src family kinase and EGFR activation. For example, the CD95 ligand-induced apoptosis in hepatocytes involves the sphingomyelinase-dependent activation of the NADPH oxidase, which in turn mediates activation of the Src family kinase Yes that stimulates the EGFR (65). We are currently testing the possibility that a similar pathway is involved in TNF-α-induced Src and ERK activation.

This work also explored how EGF stimulation activates RhoA. We identified GEF-H1 as a downstream effector of the EGFR in tubular cells. EGF has been known for many years to be a strong activator of Rho family small GTPases (27); the regulators involved in this effect, however, are only now starting to emerge. Recently, Vav2 was shown to mediate RhoA activation by mechanical stretch in mesangial cells. Stretch in turn acts through the EGFR. Similarly, Vav family GEFs are also activated in EGF-treated HeLa cells and mediate RhoG activation (66). This prompted us to test whether Vav2 is activated by EGF in tubular cells. We found that in contrast to mesangial and HeLa cells, in tubular cells EGF does not activate Vav2. In addition, RhoA activation is ERK-dependent, whereas Vav2 seems to be activated independent of ERK. These data argue against a role for Vav2 in tubular cells and suggest cell type-specific differences in the GEFs used by the EGFR pathway. Instead of Vav2, our experiments point to a key role for GEF-H1 in mediating EGF-induced RhoA activation in tubular cells; GEF-H1 is activated by EGF, and its down-regulation strongly reduces EGF-induced RhoA activation. GEF-H1 is a RhoA- and Rac-specific exchange factor (67) that has been implicated in junction regulation (13, 68, 69). Interestingly, it was also found to be required for cytokinesis (70) and cell proliferation (71, 72). The latter effect involves induction of cyclin D1, mediated by RhoA, and requires the Y-box transcription factor ZONAB. Recently, GEF-H1 was also identified as a key regulator of smooth muscle expression and fibrotic processes in retinal pigment epithelium (73). Interestingly, GEF-H1 is also a target of the proliferative MEK/ERK pathway (13, 31). It will be of interest to test whether GEF-H1 has a role in growth factor promoted proliferation.

To gain insight into the importance of the TNF-α-EGFR cross-talk with regard to tubular functions, we investigated two aspects. As the activation of the early inflammatory transcription factor NFκB was previously reported to require the EGFR or Src in fibroblasts and airway epithelia, respectively (40, 41), we first focused on this transcription factor. Our findings, however, show that TNF-α does not promote NFκB activation through the EGFR or Src in tubular cells, suggesting cell type-specific differences in the regulation of NFκB. These data imply that in tubular cells the TNF-α-elicited inflammatory effects, such as expression of adhesion receptors and production of cytokines, are mediated through an EGFR independent pathway.

Second, we explored the effect of TNF-α on cell proliferation and the establishment of the epithelial layer. Several lines of evidence suggest that the effect of TNF-α on cell fate depends on a delicate balance between two opposite effects; that, is the initiation of apoptotic and pro-survival signals. Although TNF-α has been first described as a pro-apoptotic cytokine (74), it is now known that in many cells it promotes survival and/or proliferation, partly due to activation of ERK (for review, see Ref. 74). Our data assign a key role for the EGFR in TNF-α-induced ERK activation. EGFR transactivation, therefore, could be a switch between pro-apoptotic and pro-survival effects of TNF-α. Indeed, in intestinal epithelial cells TNF-α was found to become proapoptotic only in the presence of EGFR inhibition (21). We did not find evidence that EGFR inhibition promotes TNF-α-induced apoptosis in tubular cells (data not shown). However, our data show that TNF-α enhances proliferation and promotes the establishment of the epithelial layer. These effects are similar to those found in hepatocytes (22).

Finally, it is likely that the TNF-α-EGFR cross talk might play an important role in the development of kidney diseases. Interestingly, angiotensin II, an important pathogenic factor in chronic kidney disease, was also shown to exert some of its effects through TACE-dependent release of the EGFR ligand TGF-α leading to EGFR activation (75). TNF-α, similar to angiotensin II, was also implicated in the development of chronic kidney disease (4). Therefore, our finding that TNF-α can also exert some effects through the EGFR in kidney cells raises the possibility that the EGFR activation is a common key step in kidney diseases. EGFR activation might help wound healing upon injury, enhancing recovery. However, a tilted balance leading to EGFR overactivation could also contribute to the detrimental effects of various mediators. Indeed, it is now acknowledged that EGFR signaling exerts a dual effect in the kidney. Although it promotes wound healing in short exposures, its long term effects are probably deleterious at least partly because it can promote pro-fibrotic events such as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (e.g. Ref. 76). Future studies are needed to explore the exact role of the cross-talk between the TNF receptor and EGFR signaling pathways in promoting kidney injury.

In this study we have used two well characterized cell lines. LLC-PK1 cells, derived from pig proximal tubule (77) and MDCK cells, originating from dog distal tubule (78, 79) form a polarized monolayer and have been used as favored models to study transcellular and paracellular transport processes, membrane trafficking, and signaling (for review, see Ref. 80). Although these cell lines are widely used and accepted as good models of tubular epithelia, they do not fully mimic exclusively proximal or distal tubular cells, as they were shown to exhibit some features of a mixed phenotype (81). It will be of interest to test the described effects in primary tubular cells as well as in vivo.

In summary, we showed that the TNF-α-induced activation of the ERK/GEF-H1/RhoA pathway in tubular cells is due to Src and TACE-dependent EGFR transactivation (see Fig. 8). The coupling of a proinflammatory (TNF-α) and a proliferative (EGFR) signaling pathway might serve as a proliferation/apoptosis switch and could be involved in determining the final outcome of the response. This mechanism could be important for efficient and fast wound healing but could also contribute to epithelial-mesenchymal transition and fibrogenesis. Studying the role of the TNF-α-EGFR cross-talk in kidney pathology will be an exciting further area of research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Andras Kapus and Caterina DiCiano-Oliveira for valuable advice and critical reading of the manuscript. We are also grateful to Pam Speight for technical support and expert advice.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Kidney Foundation of Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant MOP-97774, and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Grant 480619.

- TACE

- TNF-α convertase enzyme

- ADAM

- a disintegrin and metalloproteinase

- ECIS

- electric cell-substrate impedance sensing

- EGFR

- epidermal growth factor receptor

- GEF

- GDP-GTP exchange factor

- NR

- non-related

- RBD

- Rho binding domain

- SFK

- Src family kinases

- TNFR

- TNF receptor 1

- HGF

- hepatocyte growth factor

- DN

- dominant negative

- MDCK

- Madin-Darby canine kidney cells.

REFERENCES

- 1. Baud V., Karin M. (2001) Trends Cell Biol. 11, 372–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wajant H., Pfizenmaier K., Scheurich P. (2003) Cell Death Differ. 10, 45–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clark I. A. (2007) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 18, 335–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vielhauer V., Mayadas T. N. (2007) Semin. Nephrol. 27, 286–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pascher A., Klupp J. (2005) BioDrugs 19, 211–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Navarro J. F., Mora-Fernández C. (2006) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 17, 441–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peralta Soler A., Mullin J. M., Knudsen K. A., Marano C. W. (1996) Am. J. Physiol. 270, F869–F879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Al-Lamki R. S., Wang J., Vandenabeele P., Bradley J. A., Thiru S., Luo D., Min W., Pober J. S., Bradley J. R. (2005) FASEB J. 19, 1637–1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Papakonstanti E. A., Stournaras C. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 1273–1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vandenbroucke E., Mehta D., Minshall R., Malik A. B. (2008) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1123, 134–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mullin J. M., Agostino N., Rendon-Huerta E., Thornton J. J. (2005) Drug Discov. Today 10, 395–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bruewer M., Samarin S., Nusrat A. (2006) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1072, 242–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kakiashvili E., Speight P., Waheed F., Seth R., Lodyga M., Tanimura S., Kohno M., Rotstein O. D., Kapus A., Szászi K. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 11454–11466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mullin J. M., Marano C. W., Laughlin K. V., Nuciglio M., Stevenson B. R., Soler P. (1997) J. Cell Physiol. 171, 226–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patrick D. M., Leone A. K., Shellenberger J. J., Dudowicz K. A., King J. M. (2006) BMC Physiol. 6, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mathew S. J., Haubert D., Krönke M., Leptin M. (2009) J. Cell Sci. 122, 1939–1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rossman K. L., Der C. J., Sondek J. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6, 167–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moon S. Y., Zheng Y. (2003) Trends Cell Biol. 13, 13–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wallach D., Varfolomeev E. E., Malinin N. L., Goltsev Y. V., Kovalenko A. V., Boldin M. P. (1999) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17, 331–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee N. K., Lee S. Y. (2002) J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 35, 61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yamaoka T., Yan F., Cao H., Hobbs S. S., Dise R. S., Tong W., Polk D. B. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 11772–11777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Argast G. M., Campbell J. S., Brooling J. T., Fausto N. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 34530–34536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee C. W., Lin C. C., Lin W. N., Liang K. C., Luo S. F., Wu C. B., Wang S. W., Yang C. M. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 292, L799–L812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smith P. C., Guerrero J., Tobar N., Cáceres M., González M. J., Martínez J. (2009) J. Periodontal. Res. 44, 73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Doedens J. R., Mahimkar R. M., Black R. A. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 308, 331–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Higashiyama S., Iwabuki H., Morimoto C., Hieda M., Inoue H., Matsushita N. (2008) Cancer Sci. 99, 214–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Burgess A. W. (2008) Growth Factors 26, 263–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ramos J. W. (2008) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40, 2707–2719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Waheed F., Speight P., Kawai G., Dan Q., Kapus A., Szászi K. (2010) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 298, E1376–E1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. García-Mata R., Wennerberg K., Arthur W. T., Noren N. K., Ellerbroek S. M., Burridge K. (2006) Methods Enzymol. 406, 425–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fujishiro S. H., Tanimura S., Mure S., Kashimoto Y., Watanabe K., Kohno M. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 368, 162–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Biscardi J. S., Maa M. C., Tice D. A., Cox M. E., Leu T. H., Parsons S. J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 8335–8343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Di Ciano-Oliveira C., Sirokmány G., Szászi K., Arthur W. T., Masszi A., Peterson M., Rotstein O. D., Kapus A. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 285, C555–C566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wegener J., Keese C. R., Giaever I. (2000) Exp. Cell Res. 259, 158–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heijink I. H., Brandenburg S. M., Noordhoek J. A., Postma D. S., Slebos D. J., van Oosterhout A. J. (2010) Eur. Respir. J. 35, 894–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Peng F., Zhang B., Ingram A. J., Gao B., Zhang Y., Krepinsky J. C. (2010) Cell. Signal. 22, 34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kodama A., Matozaki T., Fukuhara A., Kikyo M., Ichihashi M., Takai Y. (2000) Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 2565–2575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Masszi A., Speight P., Charbonney E., Lodyga M., Nakano H., Szászi K., Kapus A. (2010) J. Cell Biol. 188, 383–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Belsches A. P., Haskell M. D., Parsons S. J. (1997) Front. Biosci. 2, d501–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hirota K., Murata M., Itoh T., Yodoi J., Fukuda K. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 25953–25958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Huang W. C., Chen J. J., Chen C. C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 9944–9952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Radeff-Huang J., Seasholtz T. M., Chang J. W., Smith J. M., Walsh C. T., Brown J. H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 863–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lo C. M., Keese C. R., Giaever I. (1995) Biophys. J. 69, 2800–2807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wegener J., Janshoff A., Galla H. J. (1999) Eur. Biophys. J. 28, 26–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McKenzie J. A., Ridley A. J. (2007) J. Cell Physiol. 213, 221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Puls A., Eliopoulos A. G., Nobes C. D., Bridges T., Young L. S., Hall A. (1999) J. Cell Sci. 112, 2983–2992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lohi J., Harvima I., Keski-Oja J. (1992) J. Cell Biochem. 50, 337–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gadea G., Roger L., Anguille C., de Toledo M., Gire V., Roux P. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117, 6355–6364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wójciak-Stothard B., Entwistle A., Garg R., Ridley A. J. (1998) J. Cell Physiol. 176, 150–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lüschen S., Falk M., Scherer G., Ussat S., Paulsen M., Adam-Klages S. (2005) Exp. Cell Res. 310, 33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bhola N. E., Grandis J. R. (2008) Front. Biosci. 13, 1857–1865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ueno Y., Sakurai H., Matsuo M., Choo M. K., Koizumi K., Saiki I. (2005) Br. J. Cancer 92, 1690–1695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chokki M., Mitsuhashi H., Kamimura T. (2006) Life Sci. 78, 3051–3057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Izumi H., Ono M., Ushiro S., Kohno K., Kung H. F., Kuwano M. (1994) Exp. Cell Res. 214, 654–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gooz M. (2010) Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 45, 146–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Díaz-Rodríguez E., Montero J. C., Esparís-Ogando A., Yuste L., Pandiella A. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 2031–2044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang Q., Thomas S. M., Lui V. W., Xi S., Siegfried J. M., Fan H., Smithgall T. E., Mills G. B., Grandis J. R. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6901–6906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kim J. Y., Lee Y. G., Kim M. Y., Byeon S. E., Rhee M. H., Park J., Katz D. R., Chain B. M., Cho J. Y. (2010) Biochem. Pharmacol. 79, 431–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ziv E., Rotem C., Miodovnik M., Ravid A., Koren R. (2008) J. Cell Biochem. 104, 606–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. van Vliet C., Bukczynska P. E., Puryer M. A., Sadek C. M., Shields B. J., Tremblay M. L., Tiganis T. (2005) Nat. Immunol. 6, 253–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Maretzky T., Zhou W., Huang X. Y., Blobel C. P. (2010) Oncogene, in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pincheira R., Castro A. F., Ozes O. N., Idumalla P. S., Donner D. B. (2008) J. Immunol. 181, 1288–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Belka C., Wiegmann K., Adam D., Holland R., Neuloh M., Herrmann F., Krönke M., Brach M. A. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 1156–1165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hanna A. N., Berthiaume L. G., Kikuchi Y., Begg D., Bourgoin S., Brindley D. N. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 3618–3630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Reinehr R., Becker S., Eberle A., Grether-Beck S., Häussinger D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 27179–27194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Samson T., Welch C., Monaghan-Benson E., Hahn K. M., Burridge K. (2010) Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 1629–1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Birkenfeld J., Nalbant P., Yoon S. H., Bokoch G. M. (2008) Trends Cell Biol. 18, 210–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Benais-Pont G., Punn A., Flores-Maldonado C., Eckert J., Raposo G., Fleming T. P., Cereijido M., Balda M. S., Matter K. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 160, 729–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Birukova A. A., Adyshev D., Gorshkov B., Bokoch G. M., Birukov K. G., Verin A. D. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 290, L540–L548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Birkenfeld J., Nalbant P., Bohl B. P., Pertz O., Hahn K. M., Bokoch G. M. (2007) Dev. Cell 12, 699–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Aijaz S., D'Atri F., Citi S., Balda M. S., Matter K. (2005) Dev. Cell 8, 777–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Nie M., Aijaz S., Leefa Chong San I. V., Balda M. S., Matter K. (2009) EMBO Rep. 10, 1125–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tsapara A., Luthert P., Greenwood J., Hill C. S., Matter K., Balda M. S. (2010) Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 860–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. MacEwan D. J. (2002) Br. J. Pharmacol. 135, 855–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Shah B. H., Catt K. J. (2006) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 27, 235–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Smith J. P., Pozzi A., Dhawan P., Singh A. B., Harris R. C. (2009) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 296, F957–F965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hull R. N., Cherry W. R., Weaver G. W. (1976) In Vitro 12, 670–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Gaush C. R., Hard W. L., Smith T. F. (1966) Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 122, 931–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Taub M., Saier M. H., Jr. (1979) Methods Enzymol. 58, 552–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Bens M., Vandewalle A. (2008) Pflugers Arch. 457, 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Gstraunthaler G., Pfaller W., Kotanko P. (1985) Am. J. Physiol. 248, F536–F544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]