Abstract

The β-subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels regulate their functional expression and properties. Two mechanisms have been proposed for this, an effect on gating and an enhancement of expression. With respect to the effect on expression, β-subunits have been suggested to enhance trafficking by masking an unidentified endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention signal. Here we have investigated whether, and how, β-subunits affect the level of CaV2.2 channels within somata and neurites of cultured sympathetic neurons. We have used YFP-CaV2.2 containing a mutation (W391A), that prevents binding of β-subunits to its I-II linker and found that expression of this channel was much reduced compared with WT CFP-CaV2.2 when both were expressed in the same neuron. This effect was particularly evident in neurites and growth cones. The difference between the levels of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) and CFP-CaV2.2(WT) was lost in the absence of co-expressed β-subunits. Furthermore, the relative reduction of expression of CaV2.2(W391A) compared with the WT channel was reversed by exposure to two proteasome inhibitors, MG132 and lactacystin, particularly in the somata. In further experiments in tsA-201 cells, we found that proteasome inhibition did not augment the cell surface CaV2.2(W391A) level but resulted in the observation of increased ubiquitination, particularly of mutant channels. In contrast, we found no evidence for selective retention of CaV2.2(W391A) in the ER, in either the soma or growth cones. In conclusion, there is a marked effect of β-subunits on CaV2.2 expression, particularly in neurites, but our results point to protection from proteasomal degradation rather than masking of an ER retention signal.

Keywords: Calcium Channels, Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), Fluorescence, Protease Inhibitor, Trafficking, GFP

Introduction

The voltage-gated calcium channel (CaV)2 family plays a major role in the physiology of excitable cells. Three subfamilies of CaV channels have been identified; CaV1 to -3. The CaV1 (L-type) channels and the CaV2 (N-, P/Q-, and R-type) channels are thought to be heteromultimers composed of the pore-forming α1-subunit, associated with auxiliary CaVβ- and α2δ-subunits (for reviews, see Refs. 1 and 2).

β-Subunits enhance the functional expression and influence the biophysical properties of the CaV1 and CaV2 channels, and two processes have been proposed to account for this. β-subunits hyperpolarize the voltage dependence of activation and increase the maximum open probability, which will increase current through individual channels and therefore result in augmented macroscopic current density (3–5). However, β-subunits have also been found to increase the number of channels inserted into the plasma membrane, as determined by gating charge measurements, imaging, and biochemical means (6–12). Nevertheless, increased membrane insertion of channels in the presence of a β-subunit has not been observed in all studies (13). As a mechanism for the effect on expression, β-subunits have been postulated to mask an ER retention signal in α1-subunits (9, 14), although no specific motif has been identified (14).

N-type calcium channels (CaV2.2) are present in both the central and peripheral nervous systems, and they have a major presynaptic role particularly in the sensory and autonomic nervous system in regulation of transmitter release (15–19). It remains unclear how CaV channels are trafficked into neuronal processes, although a previous study has implicated domains in the C terminus of the CaV2.2a long C-terminal splice variant (20). Here we have investigated whether and, if so, how β-subunits affect the expression and trafficking of N-type channels in cultured sympathetic neurons, particularly their penetration into neurites and growth cones. To do this, we have mutated tryptophan (Trp391) in the AID sequence in the I-II loop of CaV2.2. This residue is key to the interaction between β-subunits and the AID motif (21–24) and to the enhancement of functional expression of CaV2.2 by β-subunits (10, 25).

In this study, we found that YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) is expressed to a much smaller extent, compared with YFP- or CFP-CaV2.2(WT), particularly in the neurites and growth cones of SCG neurons. However, we did not find selective co-localization of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) with an ER marker. In contrast, we found that the ratio of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) to CFP-CaV2.2(WT) in both the neurites and somata was markedly increased by exposure to inhibitors of proteasomal degradation. This and further biochemical evidence suggests that the lack of high affinity interaction between a β-subunit and the I-II linker of CaV2.2(W391A) results in its increased proteasomal degradation relative to CaV2.2(WT) channel protein, rather than increased ER retention.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Constructs Used

The calcium channel cDNAs used in this study were rabbit CaV2.2 (D14157), CaVβ1b(X61394), and α2δ-1 (M86621). These cDNAs were subcloned into the vector pRK5 for expression in SCGs. Other cDNAs used were mut3bGFP (26) in pMT2 vector, dsRed-ER (calreticulin, NM004343.3, in pdsRed2 vector), dsRed-Golgi (β1,4- galactosyltransferase, NM001497.3, in pdsRed2-C1 vector), pECFP, and pEYFP (Clontech).

Cell Culture and Heterologous Expression

The tsA-201 cells were cultured in DMEM, 10% FBS, 1% Glutamax, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). The cDNAs (all at 1 μg/μl) were transfected using Fugene6 (Roche Applied Science; DNA/Fugene6 ratio of 20 μg/30 μl). Unless otherwise stated, CaV2.2 constructs were co-expressed with α2δ-1 and β1b.

Western Blot Analysis

Whole cell lysates (2.5–250 μg of protein) were prepared from tsA-201 cells, as described for COS-7 cells (27), except for the inclusion of N-ethylmaleimide (240 mm). These and other samples were separated by SDS-PAGE on 3–8% Tris acetate or 12% BisTris gels and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Immunodetection was performed with antibodies to the Cav2.2 II-III linker (27), monoclonal anti-GFP Ab (Clontech), GAPDH Ab (Abcam), anti-Akt Ab (Cell Signaling Technology), and monoclonal anti-ubiquitin Ab (P4D1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA)).

Cell Surface Biotinylation

At 18 h after transfection, cells were rinsed twice with PBS and then incubated with PBS containing 1 mg/ml Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin (Perbio) for 30 min at room temperature (unless stated). The biotin solution was removed, and cells were rinsed once with PBS and twice with PBS containing 200 mm glycine at room temperature, to quench the reaction. The cells were gently rinsed twice with PBS and then harvested in PBS containing protease inhibitors (Complete tablet from Roche Applied Science) and N-ethylmaleimide (240 mm). Cells were lysed in PBS, 1% Igepal, and protease inhibitors for 30 min on ice. The detergent lysates were then clarified by centrifugation (14,000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C). Biotinylated proteins were precipitated by adding 100 μl of streptavidin-agarose beads (Perbio) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The streptavidin-agarose beads were washed three times and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with 100 mm dithiothreitol and 2× Laemmli sample buffer. Eluted proteins were then resolved by SDS-PAGE.

Immunoprecipitation

YFP-CaV2.2 (WT or W391A mutant) was immunoprecipitated from transiently transfected tsA-201 cells as follows. Cells were harvested and lysed as described above. Clarified cell lysates were cleared with 50 μg of protein A-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) for 1 h at 4 °C. Supernatants were incubated with 2 μg/ml mouse monoclonal anti-GFP Ab (Clontech) overnight at 4 °C with constant agitation. A further 20 μg of protein A-Sepharose was added and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed three times with PBS containing 0.1% Igepal and incubated for 15 min at 65 °C with 100 mm dithiothreitol and 2× Laemmli sample buffer. Eluted proteins were then resolved by SDS-PAGE.

Construction and Expression of GFP-tagged and Palmitoylated Constructs and Confocal Imaging

GFP was fused in-frame to the C terminus of Cavβ1b and expressed from the vector pMT2. The palmitoylation sequence MTLESIMACCL was added to the N terminus of the I-II loop (amino acids 356–483) of CaV2.2, and also to the CaV2.2 I-II loop containing the mutation W391A. GFP-tagged and palmitoylated constructs were transfected into tsA-201 cells in the ratio 1:2. Where constructs were missing, the volume was made up with blank vector (pMT2). Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) 42 h after transfection. Confocal microscopy was carried out using 1-μm optical slices.

Primary Culture of SCG Neurons

This was performed essentially as previously described (28). Rats were killed by either CO2 inhalation or cervical dislocation, according to United Kingdom Home Office Schedule 1 guidelines. SCGs were dissected from rats at postnatal day 17. Ganglia were desheathed and lightly gashed before successive collagenase (Sigma) and trypsin (Sigma) treatment, both at 3 mg/ml. To produce a single-cell suspension, ganglia were dissociated by trituration and centrifugation. Dissociated cells were plated onto glass-bottomed plates (MatTeK Corp., Ashland, MA) precoated with laminin (Sigma), using one ganglion per five plates. Cells were maintained with Liebovitz L-15 medium (Sigma), supplemented with 24 mm NaHCO3, 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 33 mm glucose (Sigma), 20 mm l-glutamine, 1000 IU of penicillin, 1000 IU of streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 50 ng/ml nerve growth factor (NGF). MG132 (Sigma) or lactacystin (Sigma), when used, or their vehicle (DMSO) was applied following dilution in culture medium.

Microinjection

cDNAs were injected into SCG neurons 6–18 h after they were dissociated. Injection mixes consisted of YFP-CaV2.2 (WT or W391A) in pRK5, together with α2δ-1 and β1b, in a ratio of 3:2:2. Injection mixes for ratiometric analysis were composed of YFP-Cav2.2(WT or W391A) and CFP-Cav2.2(WT) together with α2δ-1 and β1b, in a ratio 0.75:2.25:2:2. Injection mixes for Golgi and ER visualization were composed of GFP-Cav2.2(WT), α2δ-1, β1b, and dsRED-ER or dsRED-Golgi in a ratio of 3:2:2:3. Microinjection was performed with an Eppendorf microinjection system on a Zeiss Axiovert 200 m microscope, using the following settings: 90–120-hectopascal injection pressure, an injection time of 0.1–0.2 s, and constant pressure of between 40 and 50 hectopascals. The cDNA was injected at 25–50 ng/μl diluted in 200 mm KCl. For neurite intensity experiments, the injection mix was supplemented with 20 mm dextran 647 (Invitrogen).

Staining and Fixation

In some experiments, Cell Mask Deep Red plasma membrane stain (Invitrogen) was applied at a concentration of 2.5 μg/ml for 5 min in Hanks' basal salt solution containing 47 mm sucrose. Neurons were then washed three times in Hanks' basal salt solution containing sucrose and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. Neurons were washed a further three times in Hanks' basal salt solution containing sucrose and then imaged.

Imaging

All imaging was performed on a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta scanning confocal microscope equipped with a Neofluor ×40/1.3 numerical aperture differential interference contrast oil immersion objective. The following imaging settings in nm were used throughout the project, independently and in combination. CFP imaging settings were as follows: emission band pass (BP), 475–525; laser 458 set to 17–25%; beam splitters, main dichroic 458/514 and secondary dichroic 545. GFP channel image settings were as follows: emission BP, 505–550; laser 488 set to 20–50%; beam splitters, main dichroic 488 and secondary dichroic 490. YFP channel imaging settings were as follows: emission BP, 530–600; laser 514 set to 3–9%; beam splitters, main dichroic 458/514 and secondary dichroic 545. Red channel imaging settings were as follows: emission BP, 560–615; laser 543 set to 40–60%; beam splitters, main dichroic 477/543 and secondary dichroic 490. Far red channel imaging settings were as follows: emission filters low pass, 650; laser 633 set to 30–60%; beam splitters, main dichroic UV/488/543/633.

Neurite Imaging

SCGs were imaged 18–24 h after microinjection, as stated. A neuron was centered and imaged using one or more of the above imaging channels. The pixel-dwell time was set to 3.20 μs, and the averaging was set to 4×. Settings were kept constant throughout each experiment to ensure comparison between conditions. For ratiometric comparisons of neurons expressing CFP-Cav2.2(WT) and YFP-Cav2.2(WT/W391A), the imaging settings were balanced to give an identical output from the CFP and YFP channels. Image settings were determined using neurons expressing CFP-Cav2.2(WT) and YFP-Cav2.2(WT) and then applied to neurons expressing CFP-Cav2.2(WT) and YFP-Cav2.2(W391A).

Neurite intensity analysis was performed using ImageJ on 8-bit images. The dextran 647 channel image was thresholded to an arbitrary low value to produce a mask (stencil) image of the neurites. Removal of the soma was achieved by drawing an oval highlight over the soma to ensure that only neurite regions remained. The integral intensity of the mask was measured and divided by 256 to ascertain the pixel area of the mask and therefore the neurites within the image field. Next, to convert the area from pixels to μm2, the pixel area was divided by 0.1024 (0.32 × 0.32 pixels/μm2), representing the conversion factor of a pixel to μm2 in the image field. The YFP/CFP channel images were then adjusted for background by subtraction of average intensity. The stencil image was then subtracted from the YFP/CFP channel image using the “Image calculator” function. The resultant stenciled YFP/CFP image contains only pixel values in the regions positive for neurites. The integral intensity of the stenciled YFP/CFP image was measured and normalized to the area of the neuron (μm2) to yield average neurite intensity for that channel.

Time Series Imaging of Particle Movement

Neurons were imaged at 37 °C in L15-Air medium: Liebovitz L-15 medium (Sigma), supplemented with 10 mm HEPES (Sigma), 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 33 mm glucose (Sigma), 20 mm l-glutamine, 1000 IU of penicillin, 1000 IU of streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 50 ng/ml NGF. A 3.0× scan zoom region was located, which encapsulated an area of neurites. A time series was then set using the LSM software. The time series was set for a minimum of 20 frames duration, and the rate of image capture was set to the highest achievable rate.

Time series were imported into ImageJ as a sequence of images. Using the manual tracking plugin, particles were manually highlighted through each frame of the time series. The manual tracking software outputs pixel coordinates for each location of the particle. The distance traveled in pixels was calculated and then converted into μm by multiplying with the image pixel resolution (0.15). Particles were selected on the basis that they traveled at least 10 μm within a time series. Particles were tracked from their first frame of movement, and this was terminated if the particle either stopped moving for the remaining duration of the movie or moved out of the image plane. The average speed calculated over the time series was recorded, and the maximum speed achieved by the particle was also recorded. 1–7 particles were recorded per time series, and the average speed and maximum speed were calculated from the individual particles for each cell. This was repeated for a number of cells for each condition, with each cell representing n = 1 for error calculation.

Electrophysiology

Xenopus oocytes were prepared, injected, and utilized for electrophysiology as described previously (29), with the following exceptions. Plasmid cDNAs for the different CaV subunits, α1, α2δ-1, and β1b, were mixed in 2:1:2 ratios at 1 μg/μl, unless otherwise stated, and 9 nl was injected intranuclearly after 2-fold dilution of the cDNA mixes. Recordings in Xenopus oocytes were performed as described (30), and all recordings were performed 48–60 h after injection for CaV2.2. The Ba2+ concentration was 10 mm. Current-voltage plots were fit with a modified Boltzmann equation, as described previously (30), for determination of the voltage for 50% activation (V50, act). Steady-state inactivation curves were fit with a Boltzmann equation to determine the voltage for 50% inactivation (V50, inact) (30).

RESULTS

Expression and Properties of YFP-CaV2.2 and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A)

In order to examine the trafficking of CaV2.2 in neurons, we made tagged constructs, attaching GFP, YFP, or CFP to the N terminus, for both the WT and the W391A mutant CaV2.2. We first examined the stability of these constructs by immunoblot following expression in tsA-201 cells. No free YFP or CFP was observed (supplemental Fig. 1, A and B), indicating that the fusion proteins were intact, as described previously for GFP-CaV2.2 (27). We then compared the properties of YFP-CaV2.2 and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A), together with the accessory subunits α2δ-1 and β1b, expressed in Xenopus oocytes. As expected, the W391A mutation reduced IBa very substantially (supplemental Fig. 1C), by 81% at −5 mV and by 73% at 0 mV (supplemental Fig. 1D). This mutation also depolarized both the activation and steady-state inactivation curves, as expected for the absence of interaction of the I-II linker with β-subunits (supplemental Fig. 1, C and E). Similar results were obtained previously in tsA-201 cells for the non-tagged channels (10), where an 81% reduction in peak current density was observed for untagged CaV2.2(W3891A) compared with the WT channel.

Importantly for our subsequent studies, co-expression of YFP-CaV2.2 with YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) did not cause any significant suppression of CaV2.2 currents (supplemental Fig. 1D), unlike the dominant negative suppression that we observed previously to result from expression of CaV2.2 together with non-functional truncated constructs (27, 31, 32).

No Interaction Was Observed between GFP-tagged CaVβ1b and the I-II Loop of CaV2.2(W391A)

In order to examine further whether the small currents arising from CaV2.2(W391A) were due to plasma membrane expression, despite lack of interaction with β-subunits, or to a low affinity interaction of the mutant I-II linker with β-subunits, we devised an imaging assay to specifically examine this interaction.

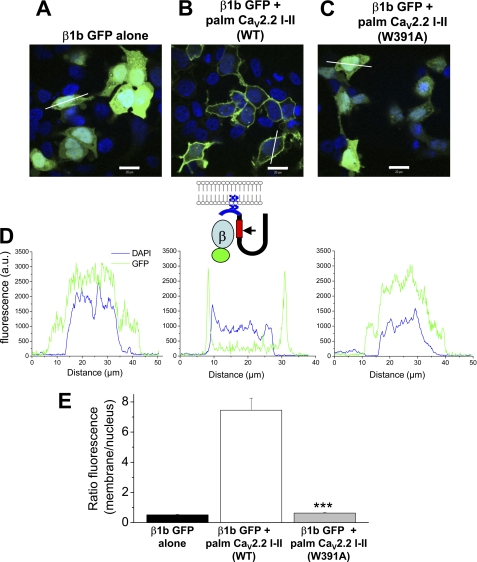

When GFP-tagged β1b was expressed alone in tsA-201 cells, it showed a uniform distribution throughout the cytoplasm and was also present in the nucleus (Fig. 1A). We took the I-II loop (amino acids 356–483) of CaV2.2 and added a palmitoylation sequence, MTLESIMACCL, to its N terminus (palm CaV2.2 I-II), in order to target it to the plasma membrane. We found that co-expression of palmitoylated CaV2.2 I-II with GFP-tagged β1b directed GFP-β1b out of the nucleus to the plasma membrane (Fig. 1B), demonstrating a positive interaction. In contrast, in the presence of palmitoylated I-II loop containing the W391A mutation (palm CaV2.2 I-II W391A), the GFP-β1b still showed a uniform distribution throughout the cytoplasm and in the nucleus (Fig. 1C). The inset schematic (in Fig. 1D) shows the likely mechanism for membrane association of GFP-β1b illustrated in Fig. 1B. Quantification of line scans, including those shown in Fig. 1D, indicated that there was no difference between the ratio of nuclear to membrane staining for GFP-β1b alone and GFP-β1b expressed with palmitoylated CaV2.2 I-II W391A, whereas in the presence of the WT CaV2.2 I-II loop construct, the ratio was more than 14-fold greater than for CaV2.2 I-II W391A (Fig. 1E). This confirms the complete lack of interaction of β1b-subunit with the CaV2.2 I-II linker containing the W391A mutation.

FIGURE 1.

Effect of co-expression of palmitoylated CaV2.2 I-II loop constructs on the subcellular distribution of GFP-tagged CaVβ1b in tsA-201 cells. A, expression of β1b-GFP alone. B, co-expression of β1b-GFP and CaV2.2 I-II loop, palmitoylated on its N terminus (palm CaV2.2 I-II WT). C, co-expression of β1b-GFP and palmitoylated CaV2.2 I-II loop containing the W391A mutation (palm CaV2.2 I-II W391A). In all images (A–C), GFP is shown in green, and nuclear staining (DAPI) is shown in blue. Scale bars, 20 μm. D, representative line scan fluorescence profiles of GFP (green) and DAPI (blue) for cells shown in A–C; for β1b-GFP alone (left), β1b-GFP plus palmitoylated CaV2.2 I-II loop (middle), and β1b-GFP plus palmitoylated CaV2.2 I-II loop containing the W391A mutation (right). Fluorescence was measured along a typical cross-section of a single cell and plotted over distance. It is expressed as arbitrary units (a.u.), determined from images in which all scanning parameters were constant. Lines used for these examples are shown in A-C. The inset schematic shows the palmitoylated construct used and the mechanism for membrane association in B. The palmitoylation motif MTLESIMACCL, shown in blue, was fused to the N terminus of the I-II loop (amino acids 356–483) of Cav2.2. The two Cys residues will be palmitoylated, which should direct the construct to the plasma membrane. The β-binding site on the I-II loop, shown in red, contains a tryptophan residue (Trp391, indicated by the arrow) which is critical for interaction with the β-subunit. E, quantification of fluorescence distribution within a cell. The ratio of fluorescence at the plasma membrane divided by the average fluorescence in the nucleus, in the region indicated by DAPI staining, was calculated for a number of cells for β1b-GFP alone (black bar, n = 11 cells), β1b-GFP plus palmitoylated CaV2.2 I-II loop (white bar, n = 10), and β1b-GFP plus palmitoylated CaV2.2 I-II loop containing the W391A mutation (gray bar, n = 12). Statistical significance of difference between WT and W391A CaV2.2 I-II loop was determined by Student's t test (***, p < 0.001). Error bars, S.E.

Quantification of Expression of YFP-CaV2.2 and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) in SCG Neurites

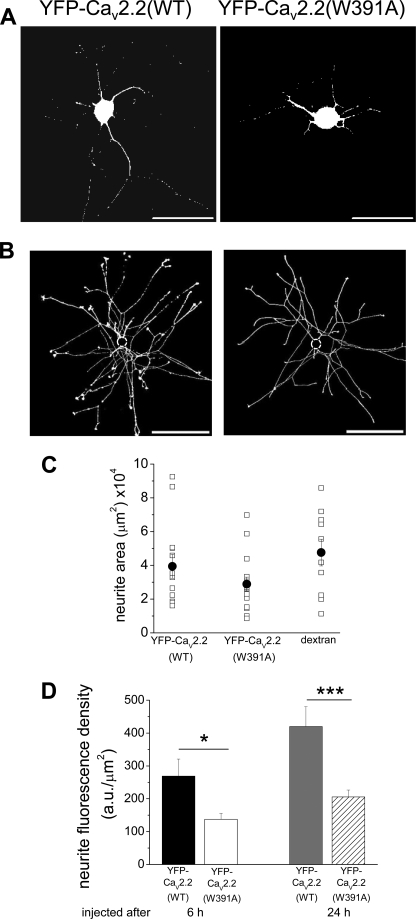

Following their microinjection into cultured SCG neurons, both YFP-CaV2.2(WT) and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A), in combination with α2δ-1 and β1b, resulted in expression in both the somata and the neurites (Fig. 2A). We developed an assay to examine quantitatively the amount of fluorescence in the neurites, to determine if there was any difference in this compartment between the expression of YFP-CaV2.2 and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A). We imaged the entire neurite arborization and excluded fluorescence from the soma (Fig. 2B). Cells were injected after 6 h in culture and imaged 18 h after microinjection. We then determined the total neurite area, using dextran 647, to obtain the neurite fluorescence density for each condition (see “Experimental Procedures”). The total neurite area of injected SCG neurons was not altered under the different conditions (Fig. 2C), but the fluorescence density was significantly reduced by 51% for YFP-CaV2.2(W391A), compared with YFP-CaV2.2 (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of expression of WT and W391A mutant YFP-CaV2.2 in SCG neurites. A, examples of SCG neurons expressing YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (left) and YFP-CaV2.2W391A (right), injected after 6 h in culture, and imaged 18 h later. Scale bars, 100 μm. B, examples of thresholded dextran 647 images showing the complete neurite arborization of SCG neurons expressing YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (left) and YFP-CaV2.2W391A (right), injected after 6 h in culture, and imaged 18 h later. Scale bars, 400 μm. The soma has been digitally removed (dotted circle). C, total neurite area for individual cells (□) expressing YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (left, n = 13) and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (center, n = 16) and cells injected with dextran red alone (right, n = 10). The mean ± S.E. (error bars) data are also given (●). D, bar chart of total neurite fluorescence density from mean data, including those illustrated in A and B. The left pair of bars represents cells injected after 6 h in culture, and imaged 18 h later: for YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (black bar, n = 13) and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (white bar, n = 15). The statistical significance between the two conditions is shown: *, p < 0.018, Student's t test. The right pair of bars shows data for cells injected after 24 h in culture, and imaged 24 h later: for YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (gray bar, n = 12) and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (hatched bar, n = 23). The statistical significance between the two conditions is indicated: ***, p < 0.001.

To examine the possibility that YFP-CaV2.2 was trafficked to the plasma membrane within the soma, which then extended neurites containing these channels, we also microinjected cells after 24 h in culture, when the neurites were already very extensive, and imaged them 24 h later. We found that the differential between YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) and YFP-CaV2.2 was maintained under this condition (Fig. 2D), with a 51% reduction in neurite fluorescence density for the YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) construct, suggesting that the channels reached the neurites, at least in part, on internal membranes.

In order to determine whether the reduction of expression of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) in the neurites occurred as a result of retention of the mutant channels in the cell body, we imaged the expression in the somatic compartment, in cells injected after 6 h in culture, and imaged 18 h after microinjection. The somatic fluorescence density was quite variable between neurons, being 169.1 ± 49.1 arbitrary units/μm2 (n = 10) for YFP-CaV2.2(WT) and 116.0 ± 34.0 arbitrary units/μm2 for YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (n = 8; p > 0.05). Nevertheless, these results do not provide any evidence for selective retention of the mutant channels within the cell body as a mechanism for the reduction in their fluorescence within the neurite compartment.

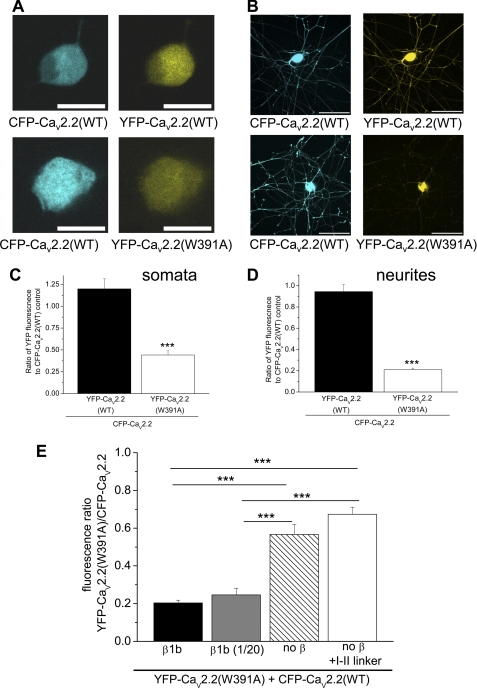

The Role of β-Subunits in the Expression of YFP-CaV2.2 and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) in SCG Neurites

Because we observed variability of expression levels between different neurons, we then included CFP-CaV2.2 in each condition, in order to have an internal control, rather than comparing between neurons (Fig. 3, A and B). In each experiment, confocal settings were used such that the control ratio of WT YFP-CaV2.2/CFP-CaV2.2 fluorescence was approximately unity. Other experimental conditions were then compared with this (Fig. 3, A and B). Using this assay, we quantified the effect of expression of the W391A mutant channel, by determining the ratio of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A)/CFP-CaV2.2 fluorescence in the cell bodies alone (Fig. 3A) or in the total neurite compartment excluding the soma (Fig. 3B). The results show that there was a reduction in the expression of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) relative to WT CaV2.2 of 63.2% in the somatic compartment (Fig. 3C) and a more marked reduction of 77.7% in the total neurite compartment (Fig. 3D), determined by this method.

FIGURE 3.

Expression of WT and W391A mutant YFP-CaV2.2 in SCG neurons, using CFP-CaV2.2 as an internal control. A, examples of SCG neuron somata expressing CFP-CaV2.2(WT) (left) together with YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (top right) or YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (bottom right), injected after 6 h in culture, and imaged 18 h later. Scale bars, 20 μm. B, examples of SCG neurons expressing CFP-CaV2.2(WT) (left), together with YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (top right) or YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (bottom right), injected after 6 h in culture, and imaged 18 h later. Scale bars, 100 μm. C, bar chart of the ratio of YFP/CFP fluorescence in somata from data such as those in A, for YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (black bar, n = 5) and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (white bar, n = 6), both expressed together with CFP-CaV2.2. The statistical significance between the two conditions is shown: ***, p < 0.0001, Student's t test. D, bar chart of the ratio of YFP/CFP fluorescence in neurites, excluding the cell bodies, from data such as those in B, for YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (black bar, n = 6) and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (white bar, n = 7), both expressed together with CFP-CaV2.2. The statistical significance between the two conditions is shown: ***, p < 0.0001, Student's t test. E, bar chart of the ratio of YFP/CFP fluorescence, from data such as those in B, for YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) expressed together with CFP-CaV2.2, in conjunction with the standard concentration of β1b (black bar, n = 10) with a 20-fold dilution of β1b (gray bar, n = 13), with no exogenous β-subunit (hatched bar, n = 10), and with the I-II linker of CaV2.2 (white bar, n = 11). The statistical significances between the conditions are shown as follows: ***, p < 0.001, one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test. Error bars, S.E.

We then investigated the effect on the relative expression of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) compared with CFP-CaV2.2(WT) of manipulating the concentration of β-subunits, together with the additional presence of a CaV2.2 I-II linker construct to sequester endogenous β-subunits. The results demonstrate the dependence of expression of WT CFP-CaV2.2 relative to YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) on both exogenous and endogenous β-subunits (Fig. 3E). The ratio between CaV2.2(W391A) and CaV2.2(WT) increased, particularly when exogenous β1b was omitted, indicating that β-subunits are a limiting factor in the expression of WT CaV2.2 in the neurites. In agreement with this, we also observed that the expression of CaV2.2(WT) in tsA-201 cells was reduced by 35% in the absence of β-subunit co-expression, whereas no effect was observed on the expression of CaV2.2(W391A) (supplemental Fig. 2, A and B). Furthermore, the effect of a reduction in β-subunit co-expression on the level of YFP-CaV2.2(WT) in neurites was also observed directly, without using the ratiometric method (supplemental Fig. 2C).

Taken together, these results indicate that YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) is expressed in neurites to a significantly smaller extent than YFP-CaV2.2 or CFP-CaV2.2, and its level of expression is not dependent on β-subunits, whereas the expression of WT CaV2.2 is strongly dependent on the presence of β-subunits.

Subcellular Localization of YFP-CaV2.2 and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) in SCG Neurites

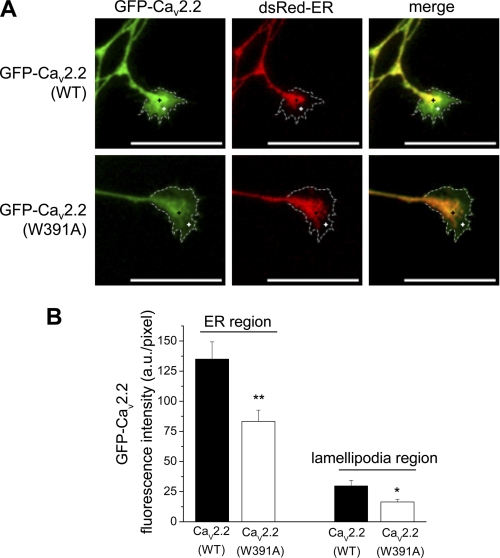

The results described above suggested to us that the low concentration of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) that is present in the neurites may not be associated with the plasma membrane. To test the accepted view that the role of β-subunits is to mask an ER retention signal (9), we compared the localization of the channels in the ER compared with post-ER compartments. To do this, we concentrated particularly on growth cones because we found the ER to be present not only throughout the soma, where it co-localized with GFP-CaV2.2(WT) (supplemental Fig. 3A), but also as a continuous network within the neurites, as previously described for hippocampal neurons (33). However, ER staining extended only into the bulb of the growth cone and was not present in the lamellipodia (Fig. 4A). A similar distribution was found for a Golgi marker in the growth cone bulb (supplemental Fig. 3B), although overall it showed a more restricted localization than the ER marker.

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of co-localization of WT and W391A mutant GFP-CaV2.2 with ER marker in neurites and growth cones. A, images of SCG growth cones showing the expression of GFP-CaV2.2(WT) (top left) and GFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (bottom left), compared with the distribution of the subcellular organelle marker, dsRed-ER (center). The merged images are shown on the right, and the extremities of the growth cones are identified by a dotted white line, determined by the use of Cell Mask dye. Scale bars, 20 μm. The black cross represents the ER region (100% ER signal), and the white cross represents the lamellipodia region outside the ER marker but within Cell Mask stain region. B, bar chart of GFP fluorescence in a region of interest (ROI) either in the region of high ER staining, indicated by the black cross (left pair of bars), or in the extremities of growth cones, indicated by the white cross (right pair of bars), from data such as that in A, for GFP-CaV2.2(WT) (black bars; n = 20) and GFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (white bars; n = 21). The statistical significance between the two conditions is shown: **, p = 0.004; *, p = 0.013, Student's t test. Error bars, S.E.

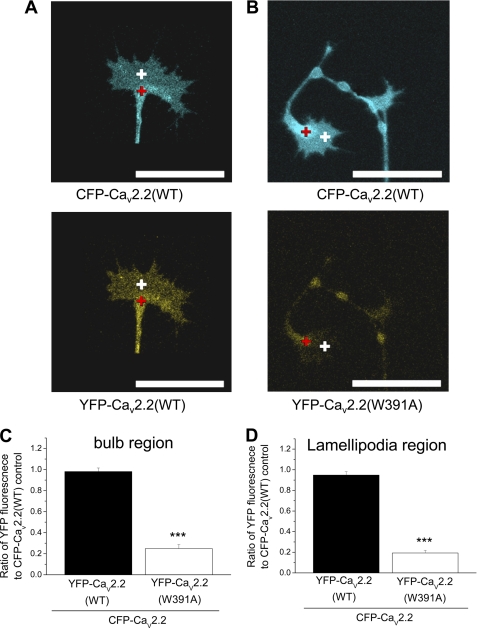

We found that WT GFP-CaV2.2 was concentrated in the bulb of the growth cones, but was also distributed in the filopodia and lamellipodia (Fig. 4A). We then compared the co-localization of GFP-CaV2.2(W391A) and GFP-CaV2.2(WT) with the ER marker dsRed-ER in the growth cones (Fig. 4, A and B). There was no differential retention of GFP-CaV2.2(W391A) within the ER region in the growth cone bulb because the ratio of fluorescence for GFP-CaV2.2(W391A) compared with GFP-CaV2.2(WT) was 61.7% within the ER region and 55.2% for the lamellipodia. There was no difference in the fluorescence signal for the ER marker under the two different conditions (supplemental Fig. 3C). To confirm this finding, we then determined the ratio of YFP/CFP fluorescence in both the bulb and the lamellipodia regions of growth cones for cells co-expressing CFP-CaV2.2(WT) and either YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (Fig. 5A) or YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (Fig. 5B). Quantification of these data showed a reduction of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) relative to the WT channel by 74.7% in the growth cone bulb region (Fig. 5C) and a slightly larger decrease, by 79.6% in the lamellipodia (Fig. 5D). These results do not provide evidence that CaV2.2(W391A) is selectively retained in the ER compartment.

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of co-localization of WT and W391A mutant CFP/YFP-CaV2.2 in growth cones. A and B, examples of growth cones from SCG neurons expressing CFP-CaV2.2(WT) (top panels) and either YFP-CaV2.2 (A, bottom) or YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (B, bottom), injected after 6 h in culture, and imaged 18 h later. ROIs such as those shown here, in the bulb of the growth cone (red cross) and in the lamellipodia (white cross), were used to calculate the data in C and D. Scale bars, 20 μm. C and D, bar chart of the ratio of YFP/CFP fluorescence in a ROI in the ER region (C) or in the lamellipodia region in the extremities of growth cones (D), from data such as those in A and B, for YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (black bars; n = 10) and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (white bars; n = 11), expressed together with CFP-CaV2.2. The statistical significance between the two conditions is shown: ***, p < 0.0001, Student's t test. Error bars, S.E.

Retrograde Transport of YFP-CaV2.2 but Not YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) in SCG Neurites

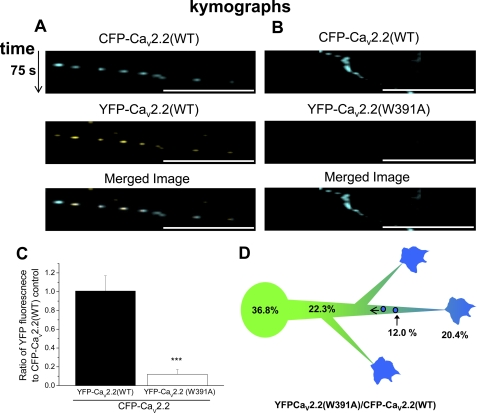

We next examined whether either YFP-CaV2.2(WT) or YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) within the neurites could be observed as discrete motile particles, as well as diffuse fluorescence. In neurons that had been injected 6 h previously, it was possible to observe particles within neurites containing YFP-CaV2.2(WT), and we therefore performed time series experiments to determine whether they were motile (supplemental Fig. 4 and associated movie). Almost all of the motile particles were observed to move in a retrograde direction and contained both YFP-CaV2.2 and CFP-CaV2.2 when these were co-expressed (Fig. 6A shows time series as kymographs). The average rate of movement of these particles was 0.54 ± 0.04 μm/s (n = 9), with a maximum rate of 1.17 ± 0.09 μm/s (n = 9). When a YFP-TrkA receptor construct was co-expressed, it was observed to co-localize in the motile particles (data not shown), indicating that they derive at least in part from growth cones. In contrast, when YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) was co-expressed with CFP-CaV2.2(WT), very little co-localization of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) with CFP-CaV2.2(WT) (12.0%) was observed in the retrogradely motile particles (Fig. 6, B and C). These results do not support the hypothesis that there was a greater retrograde transport of the mutant channel as an explanation for its lower level in the neurites.

FIGURE 6.

Ratiometric analysis of retrogradely moving particles in neurites of SCG neurons expressing CFP-CaV2.2(WT) and YFP-CaV2.2(WT/W391A). A and B, CFP-CaV2.2(WT) (top row) and YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (A) or YFP-Cav2.2(W391A) (B) (middle row) were co-expressed in SCG neurons, and retrogradely moving particles were imaged, 6 h after microinjection. Time series were recorded in the CFP and YFP channels. Imaging sensitivity was balanced in the CFP and YFP channels using the YFP-Cav2.2(WT) and CFP-Cav2.2(WT) control. Image stacks were corrected for non-motile structures, by subtraction of the time series median image. Kymographs were plotted along particle trajectories, showing time in the vertical direction, and the merged image is shown in the bottom row. The intensity of CFP-containing particles was measured and compared with the same ROI in the YFP channel. No particle movement was observed in the YFP channel of the YFP-CaV2.2(W391A)/CFP-CaV2.2(WT) condition (B). Scale bar, 20 μm. Vertical time scale, 75 s. C, bar chart of the ratio of YFP/CFP fluorescence in retrograde particle ROIs, from data such as those in A and B, for YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (black bar; n = 6 neurons) and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (white bar; n = 6 neurons), expressed together with CFP-CaV2.2(WT). The statistical significance between the two conditions is shown: ***, p < 0.001, Student's t test. D, diagram of the observed gradient of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) relative to CFP-CaV2.2 from the soma to the growth cones and retrogradely moving particles.

Taking our ratiometric imaging experiments together, we found that the ratio of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) to CFP-CaV2.2(WT) was 36.8% of the ratio of the WT channels in the soma, falling to 25.3% in the growth cone bulb, 20.4% in the lamellipodia, and 12.0% in retrograde particles, indicating that there is a gradient from the soma to distal structures (Fig. 6D).

Proteasomal Degradation of YFP-CaV2.2 and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) in SCG Neurites

The results described above suggested that YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) was subjected to increasing loss relative to the WT channel, at increasing distances from the soma. A potential explanation for this observation is that the mutant channels that do not interact with the β-subunit have a shorter lifetime. This possibility was also suggested by our observation that when β-subunits were not co-transfected with CaV2.2 in tsA-201 cells, a reduced level of CaV2.2 protein was observed (supplemental Fig. 2, A and B).

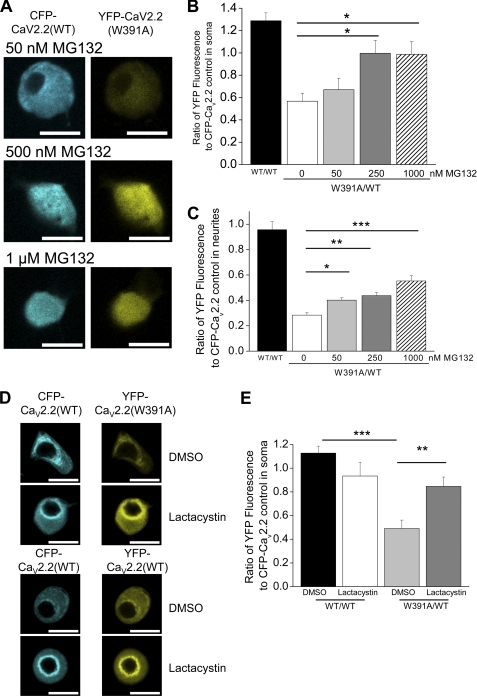

We therefore examined whether increased degradation of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) compared with YFP-CaV2.2(WT) could be responsible for its reduced level in SCG neurites and growth cones. To do this, we applied the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (34, 35) for 18 h, from 30 min after transfection, at concentrations between 50 nm and 1 μm. We found that the ratio of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) to CFP-CaV2.2(WT) in the somatic compartment showed a concentration-dependent increase, from 0.57 in the absence of MG132 to 1.0 in the presence of 250 nm MG132 (p < 0.05; Fig. 7, A and B). Furthermore, the total CFP + YFP CaV2.2 fluorescence in the somatic compartment showed an increase in the presence of MG132, suggesting that there is an overall reduction in degradation of both of these species (supplemental Fig. 5A). The use of this ratiometric method has a major advantage in that it obviates the possibility of the observed outcome being due to the proteasome inhibitor increasing expression indirectly by an effect on transcription (36), translation (37), or cell morphology (34, 38). This allowed us to deduce that there is normally greater degradation of CaV2.2(W391A) than CaV2.2(WT).

FIGURE 7.

Effect of proteasomal inhibition by MG132 and lactacystin on expression of YFP-tagged WT and W391A-CaV2.2 in SCG somata and neurites, using CFP-CaV2.2 as an internal control. A, examples of SCG neuron somata expressing CFP-CaV2.2(WT) (left), together with YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (right), injected after 6 h in culture, and imaged 18 h later, in the presence of 50 nm (top), 500 nm (middle), and 1 μm (bottom) MG132. Scale bars, 20 μm. Note that the image plane does not go through the nucleus in all cases. B, bar chart of the ratio of YFP/CFP fluorescence in cell bodies, from data such as those in A, for YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (black bar; n = 14), YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (white bar; n = 12), and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) together with 50 nm (light gray bar; n = 13), 250 nm (dark gray bar; n = 13), or 1 μm (hatched bar; n = 13) MG132. All experiments also included CFP-CaV2.2(WT). The statistical significance between YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) in the absence and presence of MG132 is shown: * p < 0.05, one-way analysis of variance and Bonferroni's post-test. C, bar chart of the ratio of YFP/CFP fluorescence in neurites, for YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (black bar; n = 17), YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) (white bar; n = 17), and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) together with 50 nm (light gray bar; n = 13), 250 nm (dark gray bar; n = 14), or 1 μm (hatched bar; n = 19) MG132. All experiments also included CFP-CaV2.2(WT). The statistical significances are shown as follows: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni's post-test. D, examples of SCG neuron somata expressing CFP-CaV2.2(WT) (left), together with YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) or YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (right), injected after 6 h in culture, and imaged 18 h later, in the presence of DMSO or lactacystin (10 μm), as indicated. Scale bars, 20 μm. Note that the image plane goes through the nucleus in all cases. E, bar chart of the ratio of YFP/CFP fluorescence in cell bodies, from data such as those in D, for YFP-CaV2.2(WT) + DMSO (black bar; n = 8), CaV2.2(WT) + lactacystin (white bar; n = 7), YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) + DMSO (light gray bar; n = 11), and CaV2.2(W391A) + lactacystin (dark gray bar; n = 11). All experiments also included CFP-CaV2.2(WT). The statistical significances are shown: ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01, one-way analysis of variance and Bonferroni's post-test. Error bars, S.E.

In the total neurite compartment, we found that the ratio of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) to CFP-CaV2.2(WT) also showed a concentration-dependent increase, from 0.28 in the absence of MG132 to 0.55 in the presence of 1 μm MG132 (p < 0.001; Fig. 7C). Furthermore, there was no effect of MG132 on the overall neurite morphology as measured by neurite branching (supplemental Fig. 5B).

In order to ascertain whether this effect would generalize to other proteasome inhibitors, we also used lactacystin (10 μm). We found that this proteasome inhibitor also markedly increased the ratio of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) to CFP-CaV2.2(WT) measured in the SCG cell bodies (Fig. 7, D and E). In these experiments, the SCG somata were all imaged in the plane of the nucleus, and lactacystin can be seen to increase the perinuclear CaV2.2 concentration.

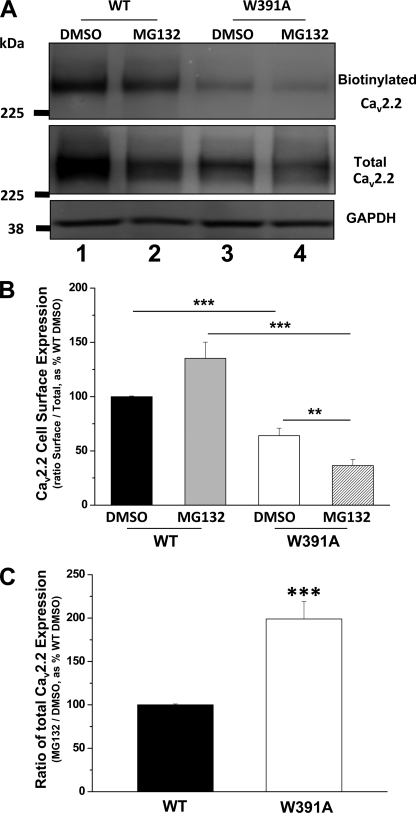

Effect of Proteasomal Inhibition on Cell Surface Localization of CaV2.2(WT) and CaV2.2(W391A)

Because of the lack of either an exofacial epitope Ab for CaV2.2 or a functional CaV2.2 construct containing a tag in an extracellular loop, we were unable to examine the effect of proteasomal inhibition on cell surface localization of CaV2.2 in microinjected SCG neurons. We therefore turned to cell surface biotinylation following expression in tsA-201 cells. As expected from our previous study (10), CaV2.2(W391A) showed less cell surface expression than CaV2.2(WT), and we found that this was reduced, rather than increased, by MG132 (Fig. 8, A and B). This indicates that, despite the reduction in degradation of CaV2.2(W391A) induced by MG132, it is likely to be in a misfolded and polyubiquitinated state that does not reach the cell surface. The data were very similar when biotinylation was carried out at 22 °C or at 17–18 °C (at which there is no endocytosis in tsA-201 cells (39)), indicating that there was no confounding effect of endocytosis during the biotinylation procedure (data not shown).

FIGURE 8.

Effect of proteasomal inhibition by MG132 on expression of WT and W391A-CaV2.2 in tsA-201 cells. A, cell surface biotinylation experiment, showing biotinylated CaV2.2 (top) and total CaV2.2 (middle), for cells transfected with CaV2.2(WT)/α2δ-1/β1b (lanes 1 and 2) and CaV2.2(W391A)/α2δ-1/β1b (lanes 3 and 4) either treated with vehicle DMSO (lanes 1 and 3) or MG132 (250 nm, lanes 2 and 4). Results are representative of nine experiments with similar results. GAPDH was used as a loading control (bottom). The biotinylation procedure did not biotinylate any cytoplasmic protein (Akt) (supplemental Fig. 6A). B, bar chart showing proportion of total CaV2.2 present at the cell surface from nine experiments, including that illustrated in Fig. 8A, for CaV2.2(WT)/α2δ-1/β1b (black and gray bars) and CaV2.2(W391A)/α2δ-1/β1b (white and hatched bars) either treated with MG132 (250 nm; gray and hatched bars) or vehicle DMSO (black and white bars). The data were corrected with the loading control (GAPDH). **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, one-way analysis of variance and Bonferroni's post-test. C, bar chart of total CaV2.2 from eight experiments, including that illustrated in Fig. 8A, expressed as a ratio of that in the presence and absence of MG132 for CaV2.2(WT)/α2δ-1/β1b (black bar) and CaV2.2(W391A)/α2δ-1/β1b (white bar). **, p = 0.00026, Student's t test. Error bars, S.E.

The total CaV2.2 immunoreactivity (Fig. 8A) was markedly increased for CaV2.2(W391A) relative to CaV2.2(WT) by MG132 (Fig. 8C), mimicking the results found in the imaging experiments. It has been shown for other channels that polyubiquitination leads to loss of function (40, 41). Our results would indicate that after MG132 treatment, the increase in CaV2.2(W391A) relative to CaV2.2(WT) does not represent CaV2.2(W391A) at the cell surface but rather an accumulation of intracellular misfolded channel that cannot be degraded by the proteasome.

This conclusion is reinforced by experiments in which YFP-CaV2.2(WT) and YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) were expressed in tsA-201 cells and then immunoprecipitated to determine the relative amount of ubiquitinated CaV2.2 (supplemental Fig. 7A). As expected, the amount of ubiquitinated CaV2.2 was increased by incubation of cells with MG132, and this was more marked for the W391A channel (a 3.6-fold increase) than for the WT channel (58% increase). However, in the absence of the proteasome inhibitor, the relative amount of ubiquitination was significantly lower for YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) than for YFP-CaV2.2(WT) (supplemental Fig. 7B), suggesting that it is normally subject to rapid degradation.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we initially investigated the role of β-subunits on the distribution of CaV2.2 channels in the cell bodies, neurites, and growth cones of SCG neurons. The β-subunits bind with high affinity to the AID sequence within the I-II linker of all CaV1 and CaV2 α1-subunits (21). The 18-amino acid AID motif has a conserved Trp that is essential for binding β-subunits (10, 21, 42). Structural data have provided detailed information concerning the interaction between the AID motif and CaVβ complex, showing that this Trp is embedded in the AID binding groove within the guanylate kinase domain of β-subunits (22–24, 43). One of the main effects of β-subunits is to increase current density for all CaV1 and CaV2 calcium channels. The mechanism for this increase is thought to be a result of both greater insertion into the plasma membrane (6–12) and hyperpolarization of the voltage-dependence of channel activation and increase in the maximum open probability (3, 4, 13).

Although the relative importance of increased membrane insertion has been disputed (13), we found previously in tsA-201 cells that when β-subunits were not co-expressed with WT CaV2.2 channels or when a β-subunit was co-expressed with CaV2.2(W391A) channels, there was reduced expression at the plasma membrane, as determined by cell surface biotinylation, which would be expected to contribute to the reduced currents observed. These results therefore provided strong evidence that the binding of β-subunits to these channels is an important requirement for functional expression of CaV2.2 at the plasma membrane (10). Similar results were also obtained previously for CaV1.2 channels (11).

However, we observed in Xenopus oocytes (present study) and previously in tsA-201 cells (10) that when CaV2.2(W391A) channels were expressed together with a β-subunit, small currents remained, either because the overexpressed β-subunit was able to bind with very low affinity to the mutated I-II linker of CaV2.2(W391A) or to other domains of the channel or because, in the absence of interaction with exogenous β-subunit, the mutant channel is still able to traffic to a small extent to the plasma membrane and conduct current. Furthermore, currents through CaV2.2(W391A) channels show a depolarized activation and steady-state inactivation (supplemental Fig. 1, C and E), characteristic of lack of interaction with a β-subunit (10). The reduced level of CaV2.2(W391A) channels at the cell surface could be due to reduced forward trafficking (9), increased endocytosis, or increased degradation from an intracellular compartment. In the present study, we have addressed these possibilities, particularly with respect to expression of the channels in the neurites of SCG neurons.

A previous study showed that β-subunit interaction with CaV1.2 was essential for trafficking into dendritic spines in hippocampal neurons (25). However, for the N-type channel CaV2.2, it is not yet possible to study its plasma membrane localization by imaging techniques because of the absence of a functional CaV2.2 construct with an exofacial tag and the lack of antibodies to extracellular loops.

In the present study, we have found that both XFP-CaV2.2(WT) and XFP-CaV2.2(W391A) channels are well expressed following microinjection into SCG neuronal somata. However, there was a lower level of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) compared with YFP-CaV2.2(WT), and this was most pronounced in neurites and in their growth cones. These experiments benefited from the use of the ratiometric assay, in which the ratio of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) to CFP-CaV2.2(WT) was compared between neurons in the same experiment with the ratio of YFP-CaV2.2(WT) to CFP-CaV2.2(WT). Using this technique, differences due to variation in microinjection efficiency or different expression levels are eliminated. In this way, we observed that, whereas the penetration of YFP-CaV2.2(WT) into the neurites was strongly dependent on the presence of β-subunits, the level being reduced by up to 70% in their absence, there was no similar effect on YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) channel expression.

Because it has been postulated that the mechanism of action of β-subunits is to mask an ER retention signal (9, 14), we investigated whether YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) was retained within the neuronal somata, where ER retention might be particularly expected to occur. We found that there was no selective retention of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) compared with CFP-CaV2.2(WT) in the cell soma, indicating that this was not an explanation for its lack of expression in the neurites. We found that the ER was present throughout the SCG neurites but only extended into the bulb of the growth cones. Because YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) fluorescence in the neurites was largely diffuse rather than confined to discrete organelles, it was therefore possible that much of the YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) that exists in the neurites might be present within the ER. However, no evidence was obtained for selective ER retention of the mutant CaV2.2(W391A) channel because the ratio of fluorescence of the mutant compared with the wild-type channel was very similar in the ER-rich region within the bulb of the growth cone, compared with the lamellipodia region, where ER was absent.

Endogenous N-type channels have been observed in growth cones of cultured sympathetic neurons (44). Although we have no direct evidence that YFP-CaV2.2(WT) reached the plasma membrane of the neurites when expressed in SCG neurons, we have indirect evidence that this is the case. We have observed retrograde transport in neurites of particles in which YFP-CaV2.2(WT) and CFP-CaV2.2(WT) are co-localized and have also observed co-localization of these particles with TrkA receptors (data not shown), which are internalized following binding to NGF (45) and therefore originate from the plasma membrane. Almost no retrograde transport of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) was observed, suggesting that it only reached the plasma membrane to a very small extent and that increased endocytosis and retrograde transport was not an explanation for its lower levels in neurites and growth cones. Furthermore, we noted that there was a gradient in the ratio of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) to CFP-CaV2.2(WT) relative to the ratio of the YFP- and CFP-WT channel pair from the soma, where it was 36.8%, decreasing to 12.0% in retrograde particles, suggesting that as it progresses down the neurites, the YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) is subjected to increasing loss or degradation relative to the WT channel (Fig. 6D).

In agreement with this hypothesis, we found that the ratio of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) to CFP-CaV2.2(WT) in both somata and neurites was markedly increased by exposure to a proteasome inhibitor (MG132) in a concentration-dependent manner. This result was replicated with another proteasome inhibitor (lactacystin). In addition, the total fluorescence attributable to both YFP-CaV2.2(W391A) and CFP-CaV2.2(WT) was increased by MG132 in the somata, indicating that the change in ratio is a result of reduced degradation. Our study is in agreement with a report in abstract form that CaV1.2 is a substrate for proteasomal degradation and is protected by the β-subunit (46). Components of the ubiquitination machinery and of the proteasome have been identified in axons and growth cones (47–49), and it is possible that the proteasome inhibitors act in neurites as well as in the somata to inhibit the degradation of YFP-CaV2.2(W391A), which is otherwise degraded more rapidly than its WT counterpart, due to protection of the WT channel by interaction with a β-subunit. Thus, the proteasome inhibitor normalizes the expression levels of the mutant and WT channels. Despite this apparent rescue of CaV2.2(W391A) by the proteasomal inhibitor, this is likely to represent the build-up of intracellular polyubiquitinated, rather than functional, channels. Indeed, our results show that MG132 did not enhance the cell surface expression of CaV2.2(W391A) in tsA-201 cells but very markedly increased its observed level of ubiquitination.

Evidence suggests that interaction of β-subunits via the AID region may promote lower affinity interactions with other domains of the channel (10, 50). Interference by the β-subunit with the proteasomal degradation of the channel may thus involve the β-subunit promoting correct channel folding and masking ubiquitination sites either on the I-II linker or elsewhere on the channel, but it may also involve prevention of retrotranslocation out of the ER (for a review, see Ref. 51). It is also possible that the β-subunit may play a direct, rather than indirect, role in inhibiting these processes.

In conclusion, interaction with the β-subunit plays an essential role in the stabilization and hence functional expression of CaV2.2 channels in addition to effects on channel biophysical properties studied previously (3–5, 10). Our studies suggest that the mechanism for this effect is for the most part not the promotion of forward trafficking as a result of decreased ER retention of the channels following interaction with β-subunit but rather protection from proteasomal degradation. We have found that loss of high affinity interaction with a β-subunit via the I-II linker results in reduced expression of CaV2.2(W391A), particularly in neurites and growth cones. This opens an important and novel area for investigation of the dynamics of calcium channel regulation, for example in the control of neuropathic pain, where N-type channel function is up-regulated (52). This is associated with an up-regulation and increased trafficking of α2δ-1 subunit protein (53). However it also involves interaction with β-subunits because knock-out of β3-subunits, the main β-subtype in sensory neurons, results in a reduction of CaV2.2 channels and a phenotype including a reduction in late phase pain behavior (54).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Claudia S. Bauer and Dr. Kurt De Vos for constructive suggestions for experiments.

This work was supported by a British Heart Foundation Ph.D. studentship (to D. W.) and Wellcome Trust Grant 077883.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–7.

- CaV

- voltage-gated calcium

- Ab

- antibody

- AID

- α-interaction domain

- BP

- band pass

- CFP

- cyan fluorescent protein

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- ROI

- region of interest

- SCG

- superior cervical ganglion

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

REFERENCES

- 1. Catterall W. A. (2000) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 521–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dolphin A. C. (2006) Br. J. Pharmacol. 147, Suppl. 1, S56–S62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Matsuyama Z., Wakamori M., Mori Y., Kawakami H., Nakamura S., Imoto K. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, RC14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meir A., Bell D. C., Stephens G. J., Page K. M., Dolphin A. C. (2000) Biophys. J. 79, 731–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Neely A., Garcia-Olivares J., Voswinkel S., Horstkott H., Hidalgo P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 21689–21694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Josephson I. R., Varadi G. (1996) Biophys. J. 70, 1285–1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kamp T. J., Pérez-García M. T., Marban E. (1996) J. Physiol. 492, 89–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brice N. L., Berrow N. S., Campbell V., Page K. M., Brickley K., Tedder I., Dolphin A. C. (1997) Eur. J. Neurosci. 9, 749–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bichet D., Cornet V., Geib S., Carlier E., Volsen S., Hoshi T., Mori Y., De Waard M. (2000) Neuron 25, 177–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leroy J., Richards M. S., Butcher A. J., Nieto-Rostro M., Pratt W. S., Davies A., Dolphin A. C. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 6984–6996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Altier C., Dubel S. J., Barrère C., Jarvis S. E., Stotz S. C., Spaetgens R. L., Scott J. D., Cornet V., De Waard M., Zamponi G. W., Nargeot J., Bourinet E. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 33598–33603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cohen R. M., Foell J. D., Balijepalli R. C., Shah V., Hell J. W., Kamp T. J. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 288, H2363–H2374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Neely A., Wei X., Olcese R., Birnbaumer L., Stefani E. (1993) Science 262, 575–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cornet V., Bichet D., Sandoz G., Marty I., Brocard J., Bourinet E., Mori Y., Villaz M., De Waard M. (2002) Eur. J. Neurosci. 16, 883–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Turner T. J., Adams M. E., Dunlap K. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 9518–9522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hirning L. D., Fox A. P., McCleskey E. W., Olivera B. M., Thayer S. A., Miller R. J., Tsien R. W. (1988) Science 239, 57–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bowersox S. S., Gadbois T., Singh T., Pettus M., Wang Y. X., Luther R. R. (1996) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 279, 1243–1249 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clasbrummel B., Osswald H., Illes P. (1989) Br. J. Pharmacol. 96, 101–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brock J. A., Cunnane T. C. (1999) Br. J. Pharmacol. 126, 11–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maximov A., Bezprozvanny I. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22, 6939–6952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pragnell M., De Waard M., Mori Y., Tanabe T., Snutch T. P., Campbell K. P. (1994) Nature 368, 67–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen Y. H., Li M. H., Zhang Y., He L. L., Yamada Y., Fitzmaurice A., Shen Y., Zhang H., Tong L., Yang J. (2004) Nature 429, 675–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Opatowsky Y., Chen C. C., Campbell K. P., Hirsch J. A. (2004) Neuron 42, 387–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van Petegem F., Clark K. A., Chatelain F. C., Minor D. L., Jr. (2004) Nature 429, 671–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Obermair G. J., Schlick B., Di Biase V, Subramanyam P., Gebhart M., Baumgartner S., Flucher B. E. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 5776–5791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cormack B. P., Valdivia R. H., Falkow S. (1996) Gene 173, 33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Raghib A., Bertaso F., Davies A., Page K. M., Meir A., Bogdanov Y., Dolphin A. C. (2001) J. Neurosci. 21, 8495–8504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ferron L., Davies A., Page K. M., Cox D. J., Leroy J., Waithe D., Butcher A. J., Sellaturay P., Bolsover S., Pratt W. S., Moss F. J., Dolphin A. C. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 10604–10617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cantí C., Page K. M., Stephens G. J., Dolphin A. C. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 6855–6864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cantí C., Davies A., Berrow N. S., Butcher A. J., Page K. M., Dolphin A. C. (2001) Biophys. J. 81, 1439–1451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Page K. M., Heblich F., Margas W., Pratt W. S., Nieto-Rostro M., Chaggar K., Sandhu K., Davies A., Dolphin A. C. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 835–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Page K. M., Heblich F., Davies A., Butcher A. J., Leroy J., Bertaso F., Pratt W. S., Dolphin A. C. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24, 5400–5409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kucharz K., Krogh M., Ng A. N., Toresson H. (2009) PLoS ONE 4, e5250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tsubuki S., Kawasaki H., Saito Y., Miyashita N., Inomata M., Kawashima S. (1993) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 196, 1195–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Palombella V. J., Rando O. J., Goldberg A. L., Maniatis T. (1994) Cell 78, 773–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Drisaldi B., Stewart R. S., Adles C., Stewart L. R., Quaglio E., Biasini E., Fioriti L., Chiesa R., Harris D. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 21732–21743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ding Q., Dimayuga E., Markesbery W. R., Keller J. N. (2006) FASEB J. 20, 1055–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Laser H., Mack T. G., Wagner D., Coleman M. P. (2003) J Neurosci. Res. 74, 906–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tran-Van-Minh A., Dolphin A. C. (2010) J. Neurosci. 30, 12856–12867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhou R., Patel S. V., Snyder P. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20207–20212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fotia A. B., Ekberg J., Adams D. J., Cook D. I., Poronnik P., Kumar S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 28930–28935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Berrou L., Klein H., Bernatchez G., Parent L. (2002) Biophys. J. 83, 1429–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Richards M. W., Butcher A. J., Dolphin A. C. (2004) TiPS 25, 626–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lipscombe D., Madison D. V., Poenie M., Reuter H., Tsien R. Y., Tsien R. W. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 2398–2402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Howe C. L., Valletta J. S., Rusnak A. S., Mobley W. C. (2001) Neuron 32, 801–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Altier C., Garcia-Caballero A., Simms B., Walcher J., Tedford H., Hermasilla T., Zamponi G. (2009) Soc. Neurosci. Abs. 519.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Campbell D. S., Holt C. E. (2001) Neuron 32, 1013–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Verma P., Chierzi S., Codd A. M., Campbell D. S., Meyer R. L., Holt C. E., Fawcett J. W. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 331–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Drinjakovic J., Jung H., Campbell D. S., Strochlic L., Dwivedy A., Holt C. E. (2010) Neuron 65, 341–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Maltez J. M., Nunziato D. A., Kim J., Pitt G. S. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 372–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ye Y., Shibata Y., Kikkert M., van Voorden S., Wiertz E., Rapoport T. A. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 14132–14138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Snutch T. P. (2005) NeuroRx 2, 662–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bauer C. S., Nieto-Rostro M., Rahman W., Tran-Van-Minh A., Ferron L., Douglas L., Kadurin I., Sri Ranjan Y., Fernandez-Alacid L., Millar N. S., Dickenson A. H., Lujan R., Dolphin A. C. (2009) J. Neurosci. 29, 4076–4088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Murakami M., Nakagawasai O., Yanai K., Nunoki K., Tan-No K., Tadano T., Iijima T. (2007) Brain Res. 1160, 102–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.