Abstract

Longitudinal models are becoming increasingly prevalent in the behavioral sciences, with key advantages including increased power, more comprehensive measurement, and establishment of temporal precedence. One particularly salient strength offered by longitudinal data is the ability to disaggregate between-person and within-person effects in the regression of an outcome on a time-varying covariate. However, the ability to disaggregate these effects has not been fully capitalized upon in many social science research applications. Two likely reasons for this omission are the general lack of discussion of disaggregating effects in the substantive literature and the need to overcome several remaining analytic challenges that limit existing quantitative methods used to isolate these effects in practice. This review explores both substantive and quantitative issues related to the disaggregation of effects over time, with a particular emphasis placed on the multilevel model. Existing analytic methods are reviewed, a general approach to the problem is proposed, and both the existing and proposed methods are demonstrated using several artificial data sets. Potential limitations and directions for future research are discussed, and recommendations for the disaggregation of effects in practice are offered.

Keywords: multilevel modeling, growth modeling, trajectory analysis, within-person effects

INTRODUCTION

Many central theories in psychology and allied fields either implicitly or explicitly focus on within-person processes. For example, when an individual engages in effective coping, this is thought to mitigate the effects of stress for this individual (e.g., Roth & Cohen 1986). Similarly, when a person experiences negative affect, this person is expected to be more likely to engage in alcohol or substance use (e.g., Kassel et al. 2010). Finally, when an individual exercises more, it is expected that his or her positive affect will subsequently increase (e.g., Penedo & Dahn 2005). These three examples all highlight that the underlying theory posits what will happen within a given individual (that is, with respect to intraindividual processes), but not across a set of individuals (that is, with respect to interindividual processes).

Despite the fact that the majority of psychological theories posit within-person processes, the research conducted to empirically evaluate these theories often involves the collection and analysis of strictly between-person data. Such between-person data almost always take the form of cross-sectional (or single time point) assessments of behavior. However, as has long been known, such data are poorly suited for evaluating within-person processes (Molenaar 2004, Schaie 1965). For example, if at a single point in time one person reports being both depressed and alcohol dependent and another person reports being neither depressed nor alcohol dependent, this does not imply that either person will drink more alcohol when experiencing negative affect. Thus, theory explicitly posits an effect at one level of analysis, yet standard cross-sectional designs and associated statistical models test an effect at a different level of analysis (e.g., Curran & Willoughby 2003).

Fortunately, there is growing recognition in our field that greater emphasis must be placed on the study of within-person processes and that this can only be accomplished through the study of intraindividual differences in repeated measures data (Collins 2006; Molenaar 2004; Molenaar & Newell 2010; Nesselroade 1991a,b; Raudenbush 2001a,b). Long- and short-term longitudinal studies are therefore becoming increasingly prevalent, including both traditional designs (e.g., Goldstein 1981) as well as newer experience sampling and ecological momentary assessment approaches (e.g., Walls & Schafer 2006). Despite this encouraging trend, the importance of focusing on within-person processes is still not universally appreciated. Interestingly, it is common to see the articulated strengths of longitudinal data designs to include factors such as the establishment of temporal precedence, the reduction of alternative potential models, and increases in statistical power (e.g., Muthén & Curran 1997). However, it is much less common to see an emphasis placed on the fact that only longitudinal data allow for the proper separation of between-person and within-person effects and that this is critically needed for fully evaluating many theories in psychology.

We are thus faced with a curious juxtaposition of recent developments. On the one hand, it is comforting to see that a clear emphasis has been placed on the importance of collecting and analyzing longitudinal data; yet on the other hand, it does not appear that a similar emphasis has been placed on the testing of within- and between-person influences on behavior once such data are obtained. The net result is that, although empirical data are increasingly available that will allow for the direct disaggregation of within-person and between person effects, this important opportunity is not often fully capitalized upon, if capitalized upon at all.

There is certainly a variety of reasons why many researchers do not take full advantage of the data that are available to them, including the potentially high cost of conducting long-term studies and the possible introduction of selective attrition over time. However, one likely factor on which we focus here is the relative lack of attention that has been paid to these rather complex issues in both the substantive and quantitative disciplines of psychology. From a substantive perspective, it is sometimes difficult to fully articulate precisely in what ways a given influence on an outcome might vary in magnitude and form when looking within persons versus across persons. For example, one might be interested in studying the relation between anxiety and substance use (e.g., Kaplow et al. 2001). It can be quite challenging to unambiguously articulate the theoretically derived expected relations between variability in overall level of anxiety and substance use across individuals (the between-person effect) and a specific individual’s variation in anxiety and variation in substance use (the within-person effect). This is even further exacerbated by the fact that these two levels of influence can operate simultaneously and even in opposite directions. We are quite sympathetic to this challenge, having wrestled with these same issues in our own substantive research.

From a quantitative perspective, undoubtedly much thoughtful and quality work has focused on these issues over the past several decades; indeed, this literature is too extensive to fully summarize here. However, there are two potential limitations of this existing work. First, many quantitative and statistically oriented resources are found in books and journals that are not typically read by substantively oriented psychologists, and (let’s be honest here) they are not always written in a way that is widely accessible to nonmethodologists. There is thus a potential problem of ineffective dissemination. Second, and more importantly, we argue that much new work is needed to overcome several unresolved issues that commonly arise in applied research settings but have not yet been closely considered from a quantitative perspective. There is thus a clear limitation in the general applicability of current analytic methods relative to the types of data that are often collected in the behavioral sciences. Taken together, although repeated measures data are becoming increasingly common in the psychological sciences, much more emphasis is needed on methods for capitalizing on these data to better test our underlying theories and hypotheses.

The purpose of our review is to thoroughly explore both the conceptual and statistical issues related to the disaggregation of between-person and within-person influences in longitudinal data. We begin with a brief conceptual discussion of exactly why evaluating within-person processes is critical in many areas of the behavioral sciences. We describe the long-known issue of disaggregating within-and between-group processes, and we describe how these same issues apply to the individual. We then move to a more analytically oriented perspective and introduce the multilevel growth model. We define the model and review standard methods that are recommended for disaggregating between- and within-person effects in practice. We then propose a more general definition of these two types of effects to better understand when standard methods can and cannot be applied, and we describe new methods of disaggregation to augment existing techniques. We move to three empirical demonstrations based on simulated data, and we demonstrate the potential utility of our new methods of disaggregation. We conclude with a discussion of unresolved issues and recommendations for the use of these methods in practice.

THE DISAGGREGATION OF LEVELS OF EFFECTS

It is well known that when a set of measures is collected at a single point in time from multiple individuals, the resulting data provide information only about between-person relationships (e.g., Molenaar 2004, Raudenbush 2001b, Raudenbush & Bryk 2002, Singer & Willett 2003). The statistical models fitted to such data are necessarily limited to between-person inferences, and thus estimation and interpretation can proceed in a rather straightforward manner (albeit in a manner that often does not test our theories in the way we desire).

In contrast, when a set of measures is collected at multiple points in time from multiple individuals, the resulting data simultaneously contain information about both between-person and within-person differences (e.g., Raudenbush & Bryk 2002, p. 183). Such data provide the opportunity to identify relationships that hold within persons as well as relationships that hold across persons. Both types of relationships can have important implications for theory. However, the statistical models fitted to these data must be carefully specified to avoid confounding the two sources of variability. Further, the substantive interpretation of results can be more challenging given the need to simultaneously consider effects operating at two levels of analysis. To think further about these issues, it is helpful to consider a specific case.

An example from the medical literature nicely illustrates the need to disaggregate levels of effect. Empirical evidence has shown that an individual is more likely to experience a heart attack while exercising (i.e., the within-person effect), but at the same time people who exercise more tend to have a lower risk of heart attack (i.e., the between-person effect) (e.g., Curfman 1993, Mittleman et al. 1993). Both the within-person and between-person findings are valid, and each has direct public health relevance. However, generalizing the between-person effect to the individual would be an error of inference (e.g., the more you exercise the more likely you are to suffer a heart attack). Further, examining only one level of this more complex two-level effect would necessarily limit the development of complete understanding of the true nature of these relations. The issues explicated in this example generalize directly to many (if not nearly all) areas of psychological research. As such, the psychological sciences can derive many benefits from the application of statistical models that generate separate and unambiguous estimates of within- and between-person effects. Yet such models are not as prevalent in the psychological sciences as they are in other related disciplines.

When considering how to disaggregate within- and between-person effects, we can begin by examining the much longer history of methodological developments for separating effects at different levels of analysis more generally. Interestingly, the problem of separating within- and between-person effects mirrors the problem of separating within- and between-group effects that has long been a focus of concern in sociology and education (e.g., Cronbach & Webb 1975, Duncan & Davis 1953, Firebaugh 1978, Mason et al. 1983, Raudenbush & Willms 1995, Robinson 1950). Because these fields are often concerned with macrolevel influences on individuals, such as teacher, school, or community effects, data are often collected in which multiple individuals are nested within each of many groups (Raudenbush & Bryk 2002, Raudenbush & Sampson 1999). Classic examples of nested/hierarchical data include children within classrooms, individuals within neighborhoods, spouses within marriages, and patients within therapists.

In these contexts, many substantive theories posit effects at both the individual and group levels. For example, positive behavior gains associated with a particular psychotherapeutic intervention may be influenced by characteristics of the individual patient (e.g., gender, ethnicity, baseline symptomatology), characteristics of the group within which the therapy was delivered (e.g., therapist experience, group size, group gender composition), or the interaction of characteristics of the patient with characteristics of the group. Thus, for many years, a distinction has been made in the study of hierarchically structured data between the examination of individual effects and contextual (or sometimes ecological) effects (e.g., Raudenbush & Sampson 1999).

Failing to recognize the important distinction between these effects can result in consequential errors of inference. In some cases, results obtained from individual data have been used to make inferences to the group level;more commonly, results obtained from group-level data are misattributed to individuals. This latter condition is known as the ecological fallacy and was first described more than half of a century ago by Robinson (1950).1 Simply put, the ecological fallacy occurs when a researcher mistakenly believes that the observed relation between two variables at the aggregate level (that is, at the level of groups) also applies at the individual level (Firebaugh 1978, Robinson 1950, Schwartz 1994). Of course, the between-group and within-group relations may ultimately be the same, but the relation at one level is neither necessary nor sufficient to imply the same relation at another level.

A classic example of the ecological fallacy is reflected in results published by Durkheim (1897) that suggested European countries with a higher proportion of Protestants were characterized by higher rates of suicide. One explanation offered to account for this observed relation was that people living under the harsh dictates of Protestantism were more likely to end their own lives. However, this is a classic case of the ecological fallacy. Specifically, there is no evidence that Protestant individuals are more likely to commit suicide than are non-Protestants within a given country. Further, there is equally no evidence to suggest that the proportion of Protestants plays any explanatory role at all; this may simply be a third-variable correlate that accounts for some other effect that was not included in the model.

Another more contemporary example comes from a study of psychostimulant prescription rates for black and white children diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Foster 2010). Although psychostimulants are a recommended treatment for ADHD, prescription rates at public agencies are lower for black than white children, reflecting broader racial disparities in health care. This difference, however, is more a consequence of between-agency differences than within-agency differences. For instance, a black child is more likely to be prescribed psychostimulants if he or she attends a clinic that services predominantly white children. Separating these two levels of effect is critical for better understanding the reasons behind racial disparities: Between-clinic differences likely reflect sources of institutional racism, such as residential segregation, whereas within-clinic differences may predominantly reflect the implicit prejudices of care providers.

A final example that is less relevant to the psychological sciences yet clearly highlights the issues at hand relates to the relation between body mass and life expectancy in mammals. Two facts have been well established (Millar & Zammuto 1983). First, on average, species that are characterized by larger body mass tend to have longer life expectancies than species with smaller body mass. So whales tend to live longer than cows who tend to live longer than ducks. However, on average, individual members within a species who are characterized by larger body mass tend to have shorter life expectancies relative to members of their own species. So fat ducks tend to have shorter life expectancies than skinny ducks. It would thus be an error to make an inference from the aggregate level (that larger species-specific body mass is associated with longer life expectancy) to the individual level (where the opposite effect actually holds). This is the heart of the ecological fallacy. Importantly, the ecological fallacy only applies when an aggregate relation is misattributed to the level of the individual. That is, the finding that species with larger body mass have longer life expectancies is unambiguously accurate at the level of the species. An error is made only when the group-level effect is applied to the individuals within the groups.2

In sum, more than half a century of both quantitative and substantive research has focused on the disaggregation of between- and within-group processes, and these methods have been used to great advantage for decades. Further, it has been long assumed that these same methods can also be used to distinguish within- and between-person effects given that the two data structures are quite similar (e.g., Enders & Tofighi 2007). In hierarchical data, individuals are nested within groups; in longitudinal data, repeated measures are nested within person. The extension of methods from one structure to the other is quite logical. However, as we demonstrate below, several key issues often arise with repeated measures data that, although less relevant in hierarchically structured data, can substantially complicate (if not wholly invalidate) the disaggregation of between- and within-person effects using existing methods.

Now we turn to a more detailed description of current analytic methods available for disaggregating levels of effect in longitudinal data. Although a variety of well-developed methods exist for analyzing such data structures, the multilevel model is extremely well suited for this endeavor, and hence it is our sole focus here.

THE MULTILEVEL GROWTH MODEL

We begin with a formal definition of the multilevel growth model. We briefly summarize this approach here, but see Bryk & Raudenbush (1987), Raudenbush (2001b), Raudenbush & Bryk (2002), and Singer & Willett (2003) for excellent in-depth overviews of these methods. Equations are necessary for formalizing these ideas, but we augment these with verbal descriptions and visual graphics whenever possible.

First, let us denote the repeated measure observed at time point t for individual i as yti. The repeated measure might represent any psychologically relevant outcome such as substance use, self-esteem, depression, or academic achievement. In a linear growth model, the observed repeated measure is expressed as a simple linear function of time, given as

| (1) |

where β0i and β1i represent the intercept and linear slope for individual i, xti is the observed value of time3 at assessment t for individual i, and rti is the time- and individual-specific residual. This represents the within-person trajectory and is sometimes called the level-1 equation. Note that more complex within-person equations can be specified, for instance to allow for nonlinear patterns of change over time (e.g., a curved trajectory), but we retain the linear form here to simplify our exposition.

An important element of the growth model is that the values of the intercept and slope components vary randomly across persons. That is, some individuals might have larger versus smaller intercepts (or initial levels), and some individuals might change more rapidly versus less rapidly over time. This variability can be expressed as

| (2) |

where γ00 and γ10 are the overall mean intercept and slope, and u0i and u1i are the individual-specific deviations from these means, respectively. This captures between-person (or interindividual) differences in within-person (or intraindividual) change and is sometimes called the level-2 equation.

The level-1 and level-2 equations are primarily of pedagogical value to allow for the within-person and between-person equations to be made explicit. However, the formal statistical model results from the substitution of Equation 2 into Equation 1 that in turn defines the reduced form expression:

| (3) |

The terms within the first set of parentheses are referred to as the fixed effects of the model, whereas the terms in the second set of parentheses are the random effects. The parameters that define the multilevel growth model described in Equations 1 and 2 are E(β0i) = γ00, E(β1i) = γ10, var(u0i) = τ00, var(u1i) = τ11, and . The covariance between random effects is also commonly estimated as part of this model (e.g., cov[u0i, u1i] = τ10). Finally, although there are a number of alternative possible covariance structures for rti, here we assume the residuals are independent and homoscedastic over time.

This model can be expanded to include one or more time-invariant covariates (TICs). Because TICs vary only across persons (e.g., gender, ethnicity, diagnostic status) and not within persons (i.e., take on different values for each person over time), their effects are strictly between-person. TICs thus enter into the level-2, or between-person, equations. For instance, denoting a single TIC as wi, we can expand Equation 2 so that

| (4) |

where γ01 and γ11 represent the fixed effect regression of the random intercept and slope components on the TIC, respectively. These regression parameters reflect the expected change in the intercept and slope of the trajectory relative to a one-unit change in the TIC. It is clear that the predictor wi is time invariant because the subscript is unique to individual i but is equal across all time points t.

Alternatively, one or more time-varying covariates (TVCs) can be incorporated into the level-1 equation that vary over both individual and time point. We denote the TVC as zti, indicating that a unique value may be obtained at any time point t for any individual i. It is easy to see that TVCs simultaneously contain both within-person and between-person variability. For example, a simple expression for the TVC is given as

| (5) |

where z̄i is the person-specific mean of the TVC pooling over time, and rti is the time-specific deviation of the TVC from the person-specific mean. It is thus clear that considering zti in isolation embodies an aggregation of both within-person and between-person variability. As such, we must carefully consider the disaggregation of these two components.

For simplicity, let us consider how a TVC enters into a model that includes a random intercept but no random time slope (that is, we do not include xti as a level-1 predictor of yti). For example, we might want to use a diary study to examine how day-to-day fluctuations in anxiety (the TVC) predict daily levels of substance use (e.g., Hussong et al. 2001). Substance use might not be expected to change systematically with the passage of time when assessed on a daily basis, so only a random intercept is needed to capture individual variability in substance use over time.

The level-1 equation for this model is given as

| (6) |

where zti represents a measure on the covariate z at time t for individual i, and all else is defined as above. Although the influence of the TVC (i.e., β1i) can itself be defined as random (Raudenbush & Bryk 2002, equation 6.21), for simplicity we assume this is a fixed effect. The corresponding level-2 equations are thus

| (7) |

with reduced form

| (8) |

Conceptually, this is expressed in precisely the same way as an ordinary least squares regression would be, but with an additional residual term (i.e., u0i) to account for the fact that there are unexplained differences among individuals in the average values of yti. These unexplained differences arise from the collection of repeated observations taken on each individual.

As is well known in the quantitative literature (but less so in the substantive literature), the effect of the TVC on the outcome (i.e., γ10) represents an aggregation of between-person and within-person influences of the TVC on the outcome (e.g., Raudenbush & Bryk 2002, equation 5.38). The reason is that zti varies both between individuals (in average level) and within individuals (across time). In some respects, these two types of differences mirror the classic distinction between traits and states (Nezlek 2007). Because zti is a combination of both sources of variability, when we estimate just one effect for zti, the result is an inextricable combination of potentially different effects operating at the two levels of analysis. To differentiate these effects, we must decompose zti into components that isolate between- and within-person differences, respectively. Fortunately, assuming certain conditions hold in the population, there are well-established methods for achieving this disaggregation of effects within the multilevel model. It is to this topic that we next turn.

TRADITIONAL METHODS FOR DISAGGREGATING BETWEEN- AND WITHIN-PERSON EFFECTS

It is well known that between- and within-person effects can be efficiently and unambiguously disaggregated within the multilevel model using the strategy of person-mean centering. Traditionally, the term centering is used to describe the rescaling of a random variable by deviating the observed values around the variable mean (e.g.,Aiken&West 1991, pp. 28–48). For example, within the standard fixed-effects regression model, a predictor xi is centered via , where x̄ is the observed mean of xi, and is the mean-deviated rescaling of xi (see, e.g., Cohen et al. 2003, p. 261). By definition, the mean of a centered variable is equal to zero, and this offers both interpretational and sometimes computational advantages in a number of modeling applications.

However, centering becomes more complex when considering TVCs. This is because multiple repeated measures are nested within each individual, and there are thus two means to consider: the grand mean of the TVC pooling over all time points and all individuals, and each person-specific mean pooling over all time points within individual. There are two ways that we can center the TVC.

First, we can deviate the TVC around the grand mean pooling over all individuals. Here,

| (9) |

where z̈ti represents the grand mean centered TVC, zti is the observed TVC, and z̄‥ is the grand mean of zti pooling over all individuals and all time points. In other words, we simply compute the grand mean of the TVC and subtract this from each individual- and time-specific TVC score. Second, we can deviate the TVC around the person-specific mean of the TVC unique to each individual. Here,

| (10) |

where żti represents the person-mean centered TVC, zti is again the observed TVC, and z̄i is the person-specific mean for individual i. In other words, we subtract just the person-specific mean of the TVC from each of that same person’s time-specific TVC scores. We can use zti, żti, or z̈ti as the level-1 predictor in Equation 8, and each is associated with a potentially different inference with respect to the disaggregation of effects.

Methods exist that allow for the disaggregation of the between-person and within-person effects using zti, żti, or z̈ti (Kreft et al. 1995, Raudenbush & Bryk 2002). However, direct estimates of these effects can be most easily obtained within the multilevel model by incorporating the person-mean centered TVC at level-1 (i.e., żti) and the person-mean at level-2 (i.e., z̄i) (Raudenbush & Bryk 2002, equation 5.41). Specifically,

| (11) |

where all is defined as above. This requires three steps: We first compute the mean of the time-specific TVCs within each individual to obtain z̄i; we then subtract that person-specific mean from each individual’s time-specific TVC values to obtain żti; finally, we use both z̄i and żti as predictors in our multilevel model.

The reduced form equation for this model is

| (12) |

where γ00 is the intercept (or grand mean), γ01 is a direct estimate of the between-person effect, and γ10 is a direct estimate of the within-person effect. Following our earlier hypothetical example, γ01 would capture the relation between average levels of anxiety and average levels of substance use pooling over individuals. In contrast, γ10 would capture the mean relation between a given person’s time-specific deviation in anxiety (relative to the overall level of anxiety) and the individual’s time-specific substance use.

The approach we outline above is currently regarded as best practice for the disaggregation of between-person and within-person effects in multilevel growth models (e.g., Raudenbush & Bryk 2002, pp. 181-85; Singer & Willett 2003, pp. 173-77), and there is no question that this is a valid method for accomplishing these goals. As we describe in greater detail below, however, the validity of this approach heavily relies on a set of specific conditions that may or may not be met in practice. Further, we have found that these conditions are rarely, if ever, discussed in either the quantitative or applied literatures. To better define these specific conditions, we next propose a more general framework for defining within-person and between-person effects. This framework both more formally establishes these expressions and allows us to explicate precisely under what conditions standard approaches are and are not valid.

A GENERAL DEFINITION OF WITHIN-PERSON AND BETWEEN-PERSON EFFECTS

The existing methods used to disaggregate within- and between-person effects implicitly assume that within- and between-person variability can be unambiguously and validly represented via z̄i and żti (as we describe above). Indeed, the historical justification for using this approach has verged on tautology: You use z̄i and żti to disaggregate between- and within-person effects because between- and within-person differences are disaggregated via z̄i and żti. This method of disaggregation is indeed valid, albeit only under certain conditions. To better explicate these conditions, we propose a more general definition of between- and within-person components of the TVC. In an attempt to avoid the siren’s song of tautology ourselves, we propose a new notation to reflect more broadly defined terms that do not rely on how the values are actually calculated. Once expressed in this way, we can then consider how these values are best estimated from empirical data.

First, we denote the between-person component of the TVC as zbi and the within-person component as zwti. The z reflects that we are referencing the TVC zti; the b and w denote between and within components of z, respectively; and the subscripts denote that the between component is unique to individual i and the within component is unique to time t for individual i. Our intent is that these more general expressions define the relevant components of the TVC in terms other than how these values are computed in sample data.

Once expressed in this way, the between-and within-person effects of the TVC on the outcome can be expressed via the model

| (13) |

where γ01 represents the between-person effect and γ10 the within-person effect. Note this is a simple restatement of Equation 12, with the caveat that we no longer presume that z̄i and żti are necessarily the best empirical representations of zbi and zwti. As before, an important distinction to keep in mind here is that zbi and zwti represent the between- and within-person components of the TVC itself, whereas γ01 and γ10 represent the between- and within-person components of the relationships between the TVC and the outcome. These different components are quite important to distinguish, and we return to this repeatedly throughout our review.

Now that we have a general notational scheme defining the disaggregation of TVC effects, we can more carefully consider the estimation of these effects under different population conditions. We consider three conditions here: when the TVC is unrelated to time, when the TVC is characterized by just a fixed effect of time, and when the TVC is characterized by both a fixed and random effect of time.

Disaggregation of Effects When the TVC is Unrelated to Time

A key aspect of our approach is to write an explicit model for the TVC itself. Given the historical presumption that z̄i and żti are prima facie valid, there has not been a prior need to write a model for the TVC. However, such a model is necessary to better establish the underlying conditions that are required to validly disaggregate the within-person and between-person levels of effect.

To do this, we begin by expressing variability in the TVC at the population level via a standard two-level model.4 The level-1 expression for the TVC is

| (14) |

where zti is the measure of the TVC at time t for individual i, β0i is the person-specific mean of zti pooling over time, and rti is the time-specific deviation of the TVC from the mean of zti for individual i. Next, the level-2 expression is

| (15) |

where γ00 is the grand mean of the TVC pooling over both time and individual, and u0i is the deviation of the person-specific mean from the grand mean. Finally, the reduced form is

| (16) |

where all terms are defined as above.

Note that this is nothing more than a random intercept model written for the TVC instead of for the outcome as is usually done. The advantage of this expression is that we can clearly see that rti captures the within-person variability of the TVC around the person-specific mean (i.e., β0i) and u0i captures the between-person variability of the TVC around the grand mean (i.e., γ00). Given this, we wish to define the within-person component of the TVC (i.e., zwti) to solely reflect variability in rti and the between-person component of the TVC (i.e., zbi) to solely reflect variability in u0i. We can now consider whether the traditional approach of setting zbi = z̄i and zwti = żti validly accomplishes this goal.

Let us first consider what z̄i represents in this case. Conceptually, we want to estimate the person-specific overall level of the TVC pooling over time. To do this, we can take the expected value of the reduced-form expression in Equation 16 for individual i. In other words, we want to compute the long run average of the TVC within each individual. This is given as

| (17) |

where γ00 is the grand mean of the TVC and u0i is the deviation of the person-specific mean from the grand mean. Importantly, because γ00 is constant across individuals, u0i represents the individual-specific between-person component of the TVC. If we replace Ei(zti) in Equation 17 with the sample realization z̄i, we get

| (18) |

and with simple manipulation we get

| (19) |

which is our estimate of zbi. Given that γ̂00 is constant, the person-specific mean alone (without deviation by γ̂00) provides a valid representation of the between-person component of the TVC unique to individual i when the model defined in Equation 16 holds in the population. Therefore, using z̄i as zbi will produce a valid estimate of the between-person component of the TVC under these conditions.

Let us next consider the within-person component of the TVC. Conceptually, we want to isolate the within-person variability of the TVC around the person-specific level of the TVC pooling over time. Recall that above we noted that the level-1 residual term (i.e., rti) captured with the within-person variability of the TVC around the person-specific mean. Given this, we can do a simple manipulation of Equation 16 to express the within-person residual as

| (20) |

highlighting that the within-person component of the TVC is indeed rti. We saw in Equation 18 that the person-specific mean can be expressed as γ̂00 + û0i, so we can in turn define the sample representation of r̂ti to be

| (21) |

Again assuming that Equation 16 holds in the population, the within-person component of the TVC can be computed by defining zwti = żti, where żti is defined as above (e.g., żti = zti − z̄i). Thus, we can obtain a valid estimate of the within-person effect using the traditional person-mean centering strategy.

A key component of these expressions is that we are defining the between- and within-person components of the TVC in terms of general expressions and then determining the appropriate sample realizations for these expressions. In this specific case, we find that computing these components as zbi = z̄i and zwti = żti meets the stated goals of the analysis. Expressing the model in this way helps us avoid the potential circularity that is sometimes present in prior discussions about methods for disaggregating TVC effects. More importantly, this allows us to generalize these expressions to conditions under which Equation 16 does not hold in the population.

More specifically, in the present case the population model for the TVC defined in Equation 16 is independent of the passage of time. In other words, although the TVC can take on a unique value at any given time point t, the conditional mean of the TVC is not systematically related to time; more succinctly, although there may be growth in the outcome (i.e., yti), there is no growth in the TVC itself (i.e., zti). However, in many longitudinal applications in the behavioral sciences, it could be quite likely (if not theoretically predicted) that the TVC is changing systematically with the passage of time. Such systematic growth might be less prevalent (if not wholly absent) in diary data or experience sampling designs in which observations are assessed daily, or even hourly. However, in designs in which assessments are made monthly or even yearly (e.g., Hussong et al. 2007, 2008), growth in the TVC might be fully expected and highly salient. Yet the standard methods used to disaggregate these effects implicitly assume the passage of time is irrelevant with respect to the TVC. We must thus carefully consider what occurs when the TVC is indeed related to time.

Disaggregation of Effects When the TVC is Characterized by a Fixed-effect of Time

We begin by extending the model for the TVC presented in Equation 16 to include a main effect of time, but the magnitude of this effect is constant over individuals. Descriptively, this model implies that the conditional mean of the TVC is linearly changing with the passage of time, but that all individuals are changing at precisely the same rate. The level-1 model is thus

| (22) |

where xti is the measure of time at time t for individual i, β1i is the linear relation between time and the TVC for individual i, and all else is defined as above. The level-2 equations are

| (23) |

where γ00 and γ10 represent the mean intercept and rate of change, respectively, and u0i is the deviation of the intercept for individual i from the overall mean. Note that there is no corresponding u term for β1i, indicating that the magnitude of the relation between time and the TVC is constant over all i. That is, individual trajectories on zti appear as parallel lines, with differences in level but not slope. Finally, the reduced form is

| (24) |

where all is defined as above.

As before, we wish to construct representations of the between- and within-person components of zti (i.e., zbi and zwti) that will isolate the between-person variability in u0i and the within-person variability in rti. Let us begin by re-expressing the between-person and within-person components of zti under this expanded model. The person-specific expected value of zti as defined in Equation 24 is now

| (25) |

Note that the between-person variability on zti is now both a reflection of u0i (i.e., the first term) and the expected value of time (i.e., the second term). Ideally, we would prefer that our measure of between-person variability not depend on the timing of assessments and instead reflect differences in level, or u0i, alone. We must thus take the influence of time into account in obtaining our sample estimates of zbi.

Rearranging Equation 25 and inserting sample estimates, we obtain

| (26) |

where x̄i is the mean of time for person i (e.g., x̄i = Σxti/Ti where Ti is the total number of time points for person i). Remember that, drawing on our general definitions above, we want to construct a variable zbi to represent this component of the TVC, yet the person-mean of the TVC contains additional variation due to potential individual differences in the mean value of time (i.e., γ̂10x̄i). Indeed, in this case, the only instance in which z̄i will provide an adequate measure for zbi is when x̄i is constant across all individuals in the sample (i.e., the data are time structured); if x̄i varies across individuals, then setting zbi = z̄i will not isolate the between-person component of the TVC in the way that we desire.

Continuing on to the expression of the within-person component, after a bit of simple algebra we can represent the person- and time-specific residual defined in Equation 24 as

| (27) |

where all remains defined as before. Note that the first term contains the person-mean centered TVC (because żti = zti − z̄i) and that in isolation this is an imperfect representation of the within-person component of the TVC because it fails to consider the time trend reflected in the second term. Similar to what we found for the between-person component of the TVC, setting zwti = żti will not isolate the within-person component of the TVC in the way that we desire. When the TVC is related to the passage of time, additional adjustments are needed to obtain ideal estimates of both zbi and zwti.

Disaggregation of Effects When the TVC is Characterized by a Fixed- and Random-Effect Time

We considered the condition in which the TVC was related to the passage of time, but the rate of change was constant in magnitude for all individuals. However, in many applications this time effect might vary randomly over individuals; indeed, in many conditions this might be expected (e.g., Hussong et al. 2007, 2008). Continuing with our hypothetical example, we might expect that not only does anxiety systematically change as a function of time, but the rates of change vary randomly over individual; some people may be changing at a faster rate, others at a slower rate, and others may not be changing at all. We can expand our equations to take this additional source of variability into account.

The level-1 model remains precisely as before:

| (28) |

but we now expand the level-2 model to allow for person-specific deviations in both the intercept and slope components of the time trends:

| (29) |

where all is as defined above, but now u1i represents the deviation of the person-specific slope from the overall mean slope. Finally, the reduced form is

| (30) |

where the first parenthetical term represents the fixed effects and the second the random effects.

In this setting, two random effects determine the between-person differences at any given point in time: between-person variability in the intercept and between-person variability in the slope. Interestingly, given the random slope component (i.e., u1i), the rank order of individuals can (and usually will) differ from one occasion to the next. This can be visualized by picturing a set of individual trajectories, each of which is defined by its own intercept and slope. Because some are changing at faster rates than others, the rank ordering of individuals on the TVC at a given point in time depends upon the specific point chosen. At one point in time there will be one rank ordering, and at another point in time there will be a different rank ordering.

As we discuss below, the time-dependent nature of the rank ordering makes it more difficult to conceptualize precisely what zbi ought to represent. This is because the between-person component of the TVC captures between-person variability, yet this same variability changes at each time point in the presence of random growth (e.g., Biesanz et al. 2004). One reasonable way to define between-person differences in this context is as the difference in average levels of zti that we would expect to observe at the average value of time. If we assume time (xti) is scored so that zero is placed in the center of the time axis, then this is precisely what u0i represents, so we can again isolate this term to determine how best to compute zbi. However, our between-person component of the TVC is taken at the mean of time, and this value can (and likely would) change at any other point in time.

The expression for the person-specific expected value of the TVC is slightly more complex than before, but not terribly so:

| (31) |

This expression highlights the influence of both the person-specific intercept (via u0i) and person-specific slope (via u1i) weighted by the person-mean of time. Thus, between-person differences can be represented in the sample via

| (32) |

which contains information about both the fixed and random effects of time. Clearly, z̄i does not isolate variability in û0i, and hence a different measure for zbi must be constructed. Similar to the previous case, time-structured data present an exception. In this case, if the data are time structured and time has been centered around the mean (as we have assumed), then this implies that x̄i = 0 for all i. Thus Equation 32 will simplify to the set of terms in the first parentheses, and z̄i will be an adequate sample representation for u0i. However, this scenario rarely occurs in practice.

Moving on to the within-person component of the TVC, we can also isolate the individual-and time-specific residual such that

| (33) |

This also highlights the salient role of both the fixed and random effects defining the relation between the TVC and time. The first term again contains the person-mean centered TVC, or żti, and this continues to be an insufficient measure of zwti because it fails to consider the individually varying time trend reflected in the second term.

A key issue to which we have already alluded relates to whether time is balanced or unbalanced. Because traditional methods for disaggregating between- and within-person levels of influence assume no systematic relation between time and the TVC (i.e., Equation 16), there has been no need to consider the impact of different ways in which time might enter the model. However, when the TVC is related to time (i.e., Equations 24 and 30), we must more carefully evaluate in precisely what ways time can enter into the model. Of key importance here is whether the repeated measures data are collected using a design that is balanced or unbalanced with respect to time.

The Structure of Time: Balanced Versus Unbalanced

A design is time structured, or balanced with respect to time, if all individuals are the same age when assessed at the same time periods over the same total span of time (e.g., Bollen & Curran 2006, p. 75). This is a highly restrictive condition that is more prevalent in controlled lab-based designs but is relatively rare in most observational studies conducted in the behavioral sciences. For example, behavioral aggression in lab mice might be measured starting precisely at 28 days of age and reassessed every seven days for two months. There are no missing data, and all mice are the same age at each assessment. Although not common, there are situations when such designs also appear in studies of humans. One example is a birth cohort design in which a sample of individuals is collected from a single birth cohort (e.g., all children born in January of a given year) and is then followed annually over time. However, even in this situation we must make the unrealistic assumption of no missing data over time. Of importance to our discussion here, data that are balanced on time offer several simplifying conditions relevant to the separation of the TVC effects.

We showed above that when the TVC is related to time, both the time-specific value of time (i.e., xti) and the person-specific mean of time (i.e., x̄i) play a role in the disaggregation of effects (i.e., Equations 26 and 27, and Equations 32 and 33). An interesting characteristic of designs that are balanced on time is that all individuals have the same value of x̄i. It is easy to see why. The person-specific mean of time is defined as

| (34) |

where t = 1, 2, …, T represents the observation number for the person. For balanced designs, the values for xti are identical across cases for any given value of t. For instance, at the first time point, or t = 1, everyone in the sample might be 16 years old, and additional observations from that point forward might be made on the entire sample at one-year intervals. As such, the person-mean of time is equal for all individuals; more formally, x̄i = x̄ for all i. As we demonstrate empirically, this characteristic makes the disaggregation and interpretation of the between-person component of the TVC rather straightforward.

In contrast, a design is considered unbalanced with respect to time if all individuals are not assessed at all of the same points in time (e.g., Mehta & West 2000). Given this, in a design that is unbalanced with respect to time, individual ages will vary at any given assessment point. That is, xti is no longer constant over i for a given t. For example, one subset of observations may have been taken at ages 6, 7, 8, and 9, whereas another subset was taken at ages 8, 9, 10, and 11. This type of design is actually quite common in the behavioral sciences and often takes the form of a cohort-sequential (or accelerated longitudinal) design (e.g., Schaie 1965). Instead of all subjects being 6 years old at the first assessment, children might range between 6 and 10 years of age at first assessment. Thus multiple cohorts of children are combined within each assessment (e.g., cohort one subjects were age 6 at the first assessment, cohort two were age 7 at the first assessment, and so on).

Now consider a more general expression for the person-specific mean of time that allows for variability in time across observations:

| (35) |

Here t = 1 represents the first time of assessment, and Ti represents the total number of observations made on individual i. The values of xti need not be constant for a given t. To continue the example from above, in the case of a multiple cohort design, xti might take on values of 6, 7, 8, 9 for a person in cohort one and values of 8, 9, 10, 11 for a person in cohort two. Unlike balanced designs, in which the person-mean of time is constant over individual, the person-mean of time now varies over individuals. For example, an individual assessed at 6 through 9 has a midpoint of 7.5, but an individual assessed at 8 through 11 has a midpoint of 9.5. This has direct implications for how we disaggregate the between-person component of the TVC when the data are not balanced on time.

Summary

We have covered much ground thus far and here briefly summarize our key developments prior to examining how these impact the disaggregation of effects in practice. First, we proposed a general definition for the between-person and within-person components of the TVC and denoted their sample representations as zbi and zwti, respectively. Second, we showed that under the assumption that the TVC is wholly unrelated to time, these components can be validly expressed via the person-mean (z̄i) and person-mean centered deviate (żti). We also showed that when there are time trends in the TVC, z̄i and żti are often poor choices for zbi and zwti. An exception is the rather rare condition where data are time structured (i.e., observations are balanced on time, and there are no missing data). In this circumstance, zbi can be validly defined as z̄i, even when there are time trends in zti. However, even in this case, żti remains inadequate for zwti.

Thus, when the TVC model is unrelated to time, the standard methods currently recommended in practice provide valid estimates of within- and between-person effects. However, when the TVC is systematically related to time, the standard methods are no longer sufficient to accurately capture the between- and within-person components of the TVC, and additional analytic steps are needed to isolate these effects. Several empirical demonstrations below highlight how these issues are manifested in practice and illustrate alternative methods for computing zbi and zwti.

EMPIRICAL DEMONSTRATIONS

Up to this point, we have primarily approached our thesis at the level of equations. To both augment our communication of these ideas and to empirically validate our analytic developments, we turn to three empirical demonstrations. We use artificially generated data so that we know precisely what is the population-generating model. This allows us to draw unambiguous conclusions about the extent to which a sample estimate is or is not recovering the known population parameter. We draw on characteristics of previously published applications of this type to define what we considere to be typical situations in which these methods might be applied in practice. However, all of our conclusions would hold equally across a wide range of alternative design characteristics (e.g., number of time points, spacing of time points, sample size, etc.).

We could consider six possible conditions: three types of growth in the TVC (no growth, growth with only a fixed effect, and growth with a fixed and random effect), each crossed with two types of structure of time (balanced or unbalanced). We focus here on the three that we believe are most common in practice: (a) no growth in the TVC with balanced time,5 and individually varying time trends in the TVC under structures of time that are either (b) balanced or (c) unbalanced.

Disaggregation of Effects With No Growth in the TVC and Time is Balanced

We begin by examining an artificial data set that was created to correspond to conditions under which the person-mean centering approach is expected to properly disaggregate within- and between-person effects. More specifically, we assume that Equations 13 and 16 hold in the population. For our initial data set we generated n = 500 simulated cases, each with T = 9 repeated measures. We scaled time so that the mean of time was zero (i.e., t = −4, −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4), although given the absence of growth in this condition, the scaling of time has no impact in the current model. Finally, because this design is balanced on time, all individuals are the same age, are assessed at the same points in time, and there are no missing data.

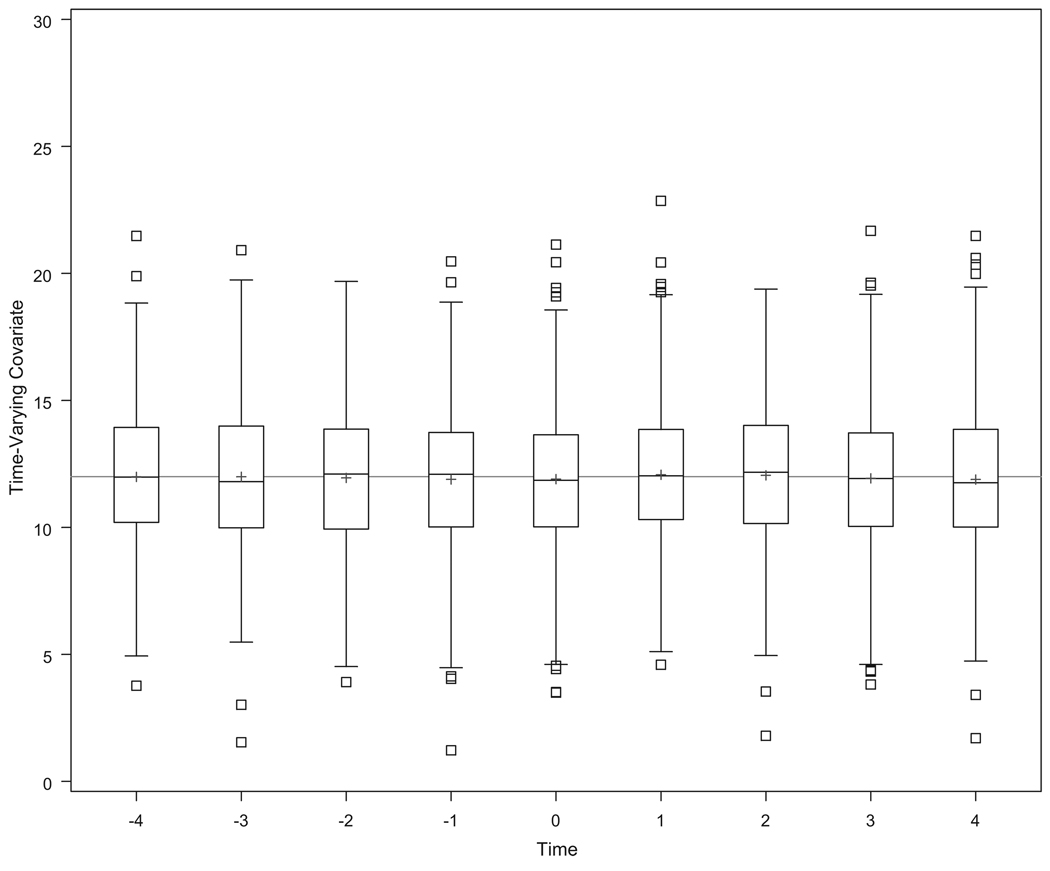

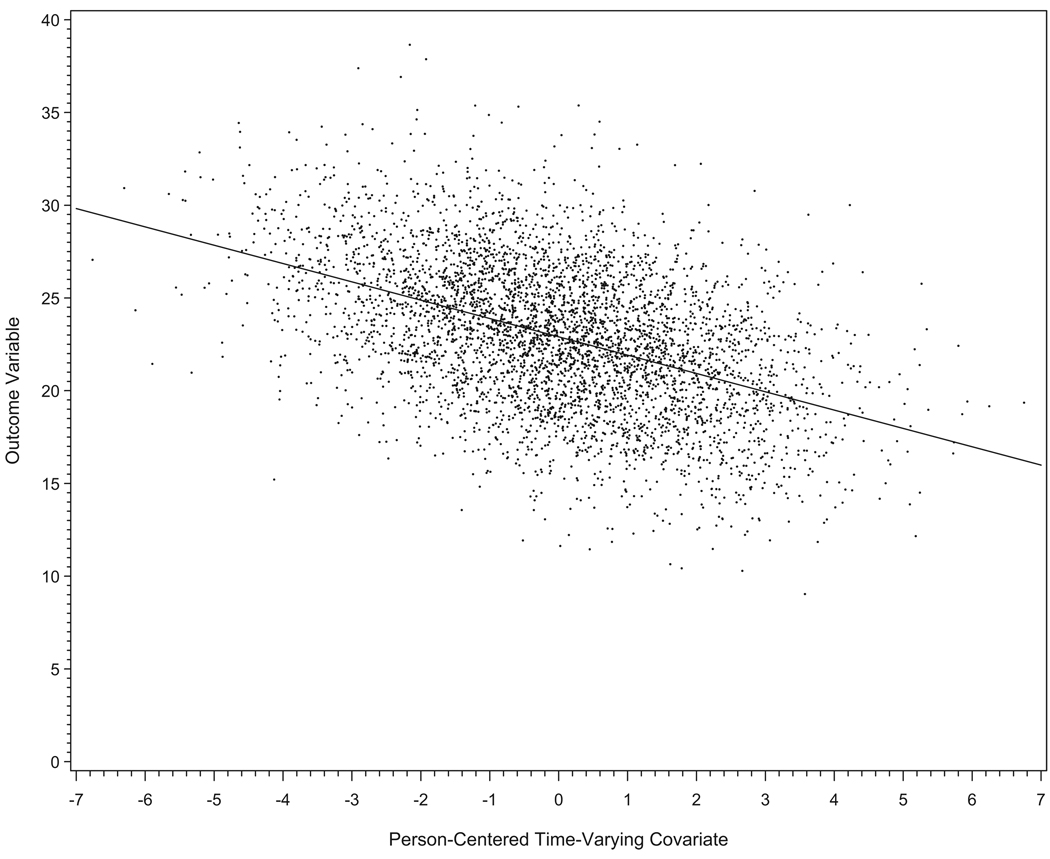

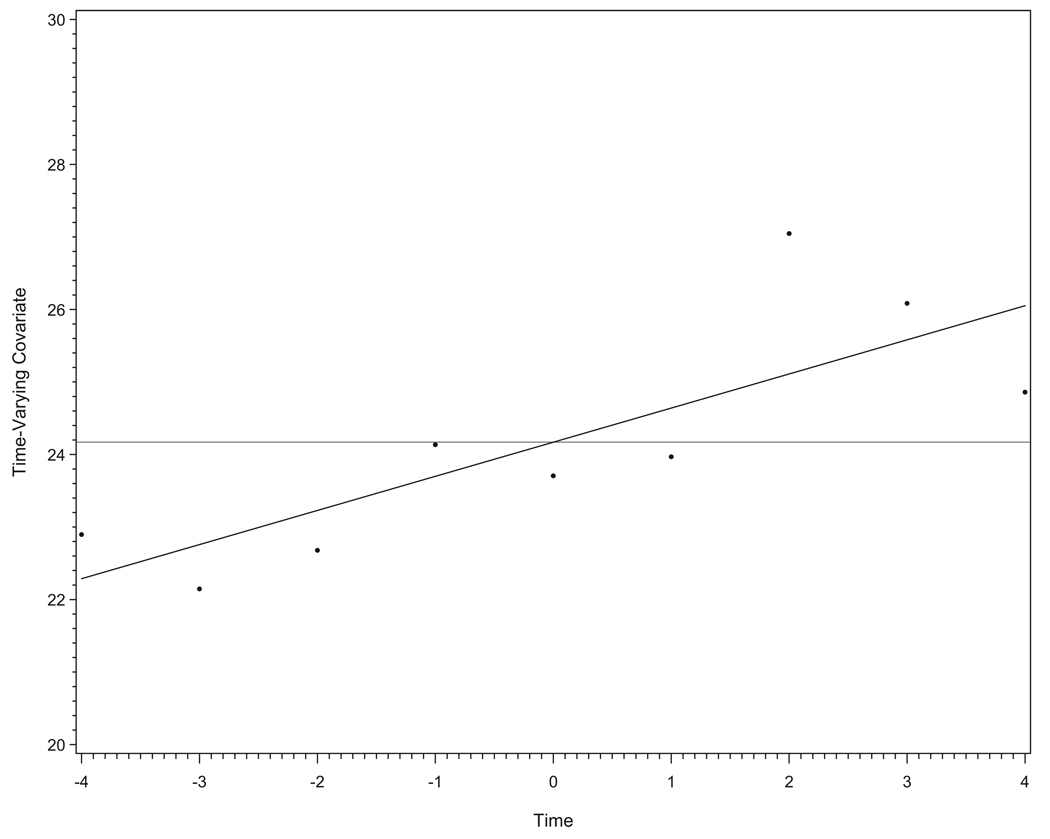

We can first consider the characteristics of the TVC itself prior to examining the simulated outcome variable. We generated the TVC to be independent of the passage of time; in other words, there is no systematic growth process that underlies zti, consistent with Equation 16. This might be reflective of daily measures of anxiety in which anxiety varied both within and between individuals, but it did not systematically increase or decrease over time. This can be seen in the conditional distribution of the TVC as a function of time presented in Figure 1, in which the distribution of the TVC at each specific time point is nearly identical; that is, the mean of the TVC is independent of time.

Figure 1.

The time-specific distributions of the TVC (zti) for the first artificial data set.

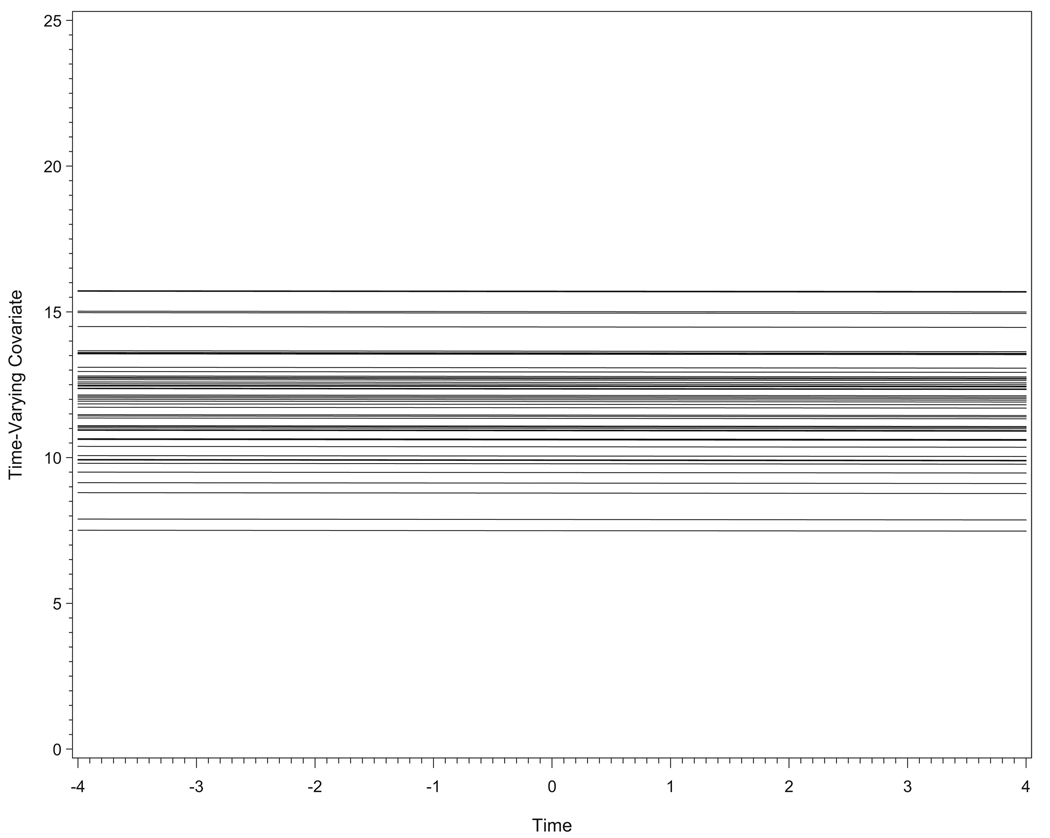

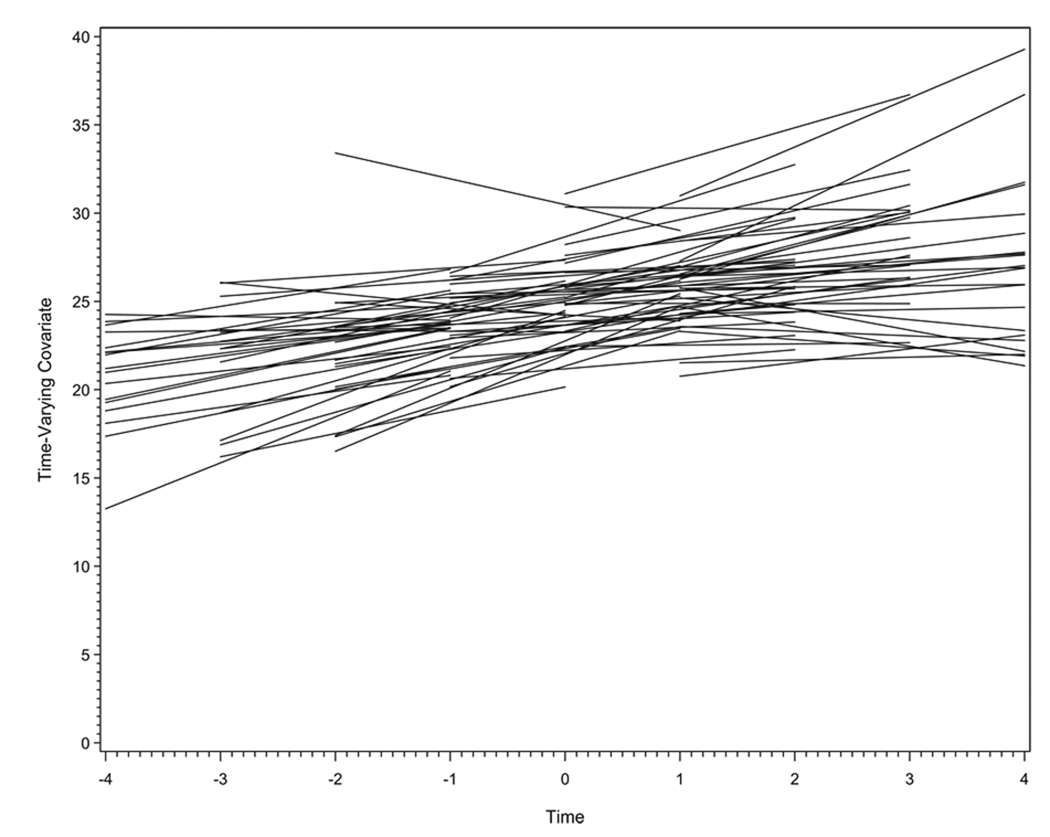

The box plots in Figure 1 show the distributions of the TVC pooling over individuals within each time point. However, we can also examine the individual trajectories of the TVC over time. Figure 2 shows the model-implied trajectories of the TVC for 50 randomly selected observations. Two characteristics are particularly important. First, because there is no time trend in the population model, the estimated trajectories are perfectly flat with respect to time. That is, there is no systematic change in the TVC as a function of time. Second, there is substantial individual variability in the relative heights of the individual trajectories. That is, some observations reflect higher levels of the TVC, and others report lower levels. This between-person variability is captured in the random intercept term in Equation 15 from above. Extending our hypothetical example, this figure shows that although anxiety does not change systematically as a function of time, some people are reporting higher overall levels of anxiety, whereas others are not.

Figure 2.

Model-implied growth trajectories for the TVC (zti) over time for 50 randomly drawn observations from the first artificial data set.

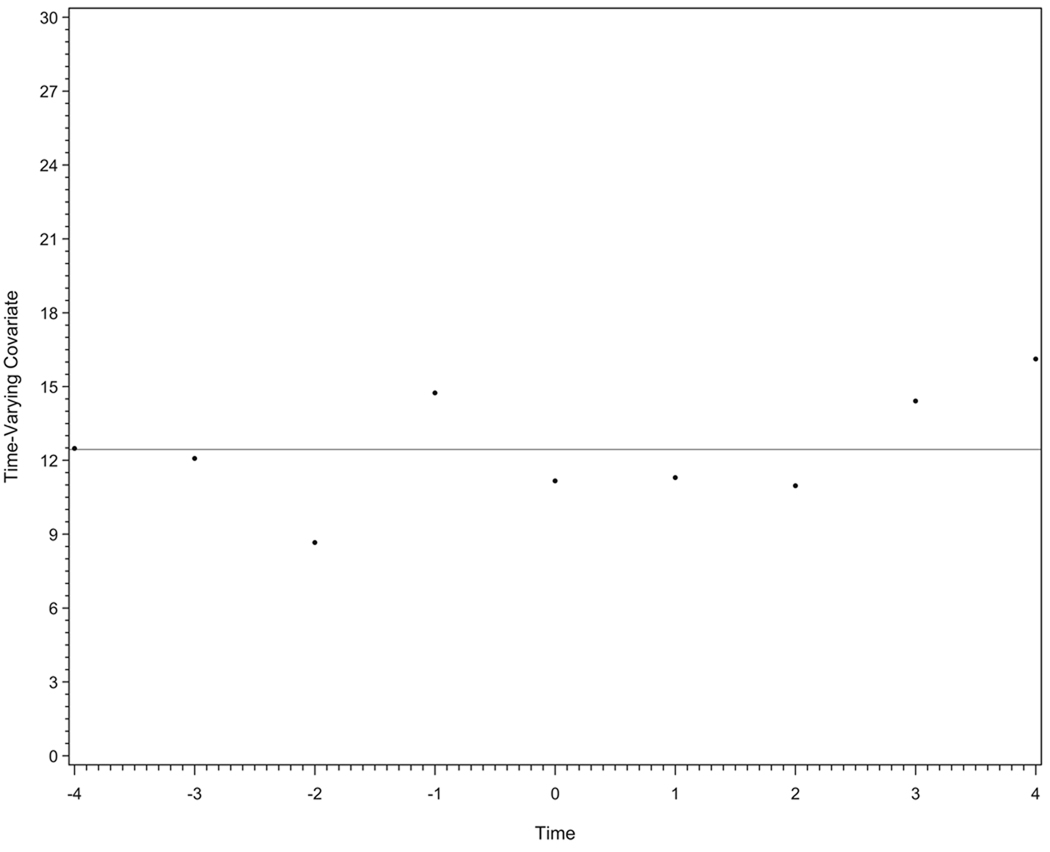

It is also helpful to consider the set of observations for just one individual plotted over all the time points; this highlights the within-person variability around each individual trajectory. For example, we could consider the nine repeated measures of anxiety taken on just one individual. The data for a single randomly chosen individual is presented in Figure 3, in which the observed TVC values are plotted against time. The points are the time-specific measures of the TVC, and the horizontal line demarcates the sample mean for the person, pooling over the set of TVCs. The horizontal line thus shows the overall level of anxiety for this individual, and the points show the time-specific values of anxiety relative to the overall level. We can see that the TVC does not appear to be related to time and that the time-specific measures of the TVC vary randomly around the person-specific mean. This is precisely what allows us to deviate each time-specific measure of the TVC from the person-mean to disaggregate the between-person and within-person effects.

Figure 3.

The time-specific values of the TVC over time for a randomly drawn case from the first artificial data set.

Thus far we have considered only the overtime characteristics of the TVC itself. Next we turn to our simulated outcome, yti, which was generated to be consistent with Equation 13; in words, this is a random intercept-only model for a continuously and normally distributed outcome variable with both a within-person and between-person effect of the single TVC zti. In our hypothetical example, the outcome could represent daily alcohol use that varies both within and between individuals but does not systematically change over time. The overall intercept of the model for yti was defined to be γ00 = 5.0, the within-person effect was γ10 = −1.0, and the between-person effect was γ01 = 1.5. Thus, higher time-specific deviations of the TVC from the overall person-mean are associated with lower values of the outcome, whereas higher overall person-means are associated with higher values of the outcome.

We chose these values to reflect the hypothetical relation that might be found between daily anxiety symptoms and daily alcohol use. More specifically, the positive between-person effect reflects that, on average, people who are more anxious tend to drink more alcohol; this might be attributable to a self-medication process, where alcohol is consumed to modulate anxiety symptoms (e.g., Kassel et al. 2010). In contrast, the negative within-person effect reflects that, on average, people tend to drink less alcohol on days when their anxiety is elevated relative to their typical stable level; this might be attributable to an individual avoiding alcohol-related social contexts on days when anxiety is particularly pronounced (e.g., Kaplow et al. 2001). Note that although theory is predictive of these relations, for our purposes here we consider these strictly hypothetical (although we would sure like to see this study done).

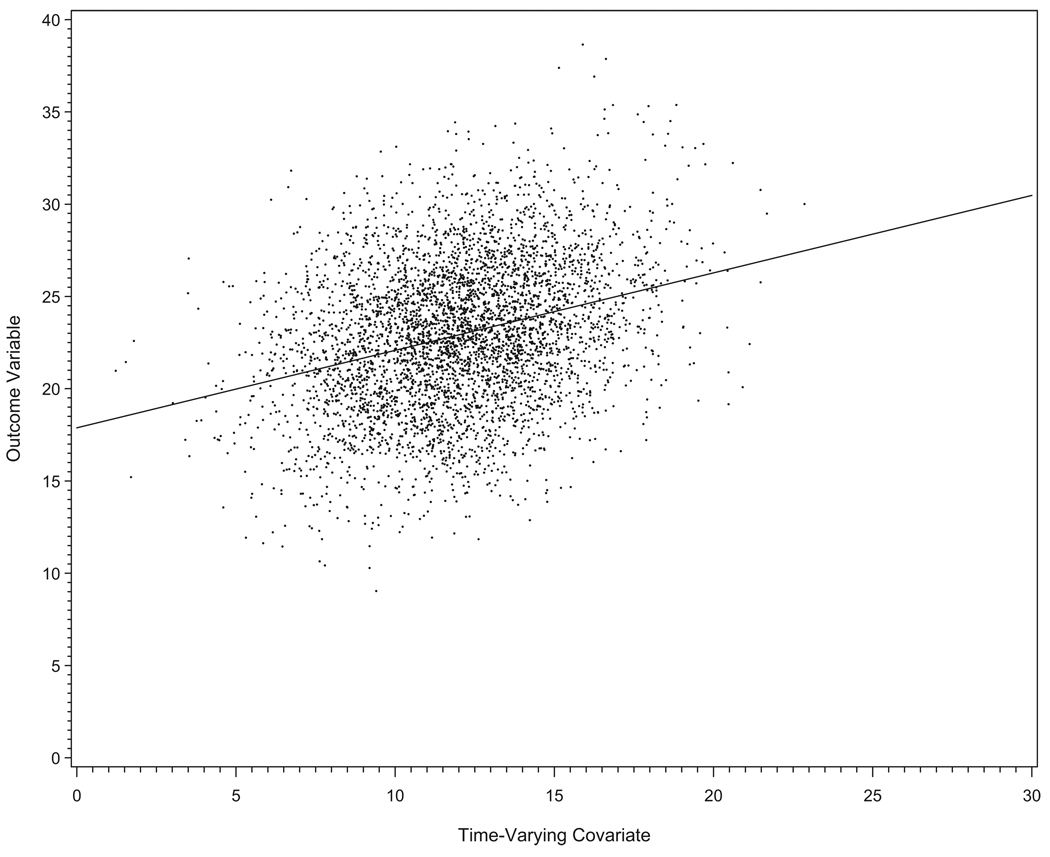

To begin, consider the simple bivariate scatter plot in Figure 4, where the TVC is plotted on the x-axis and the outcome on the y-axis. Although we see a generally positive trend, this is an inextricable aggregation of the between-person effect (which is positive) and the within-person effect (which is negative). Following our hypothetical example, we would conclude from the aggregate analysis that there is a positive relation between anxiety and alcohol use that is modest in size and holds across all individuals in the sample. However, we know the true relation to be patently different. To recover the more complex relation that truly exists, we must disaggregate the TVC into the between-person component (zbi) and the within-person component (zwti).

Figure 4.

The bivariate distribution between the outcome (i.e., yti) and the time-varying covariate (i.e., zti).

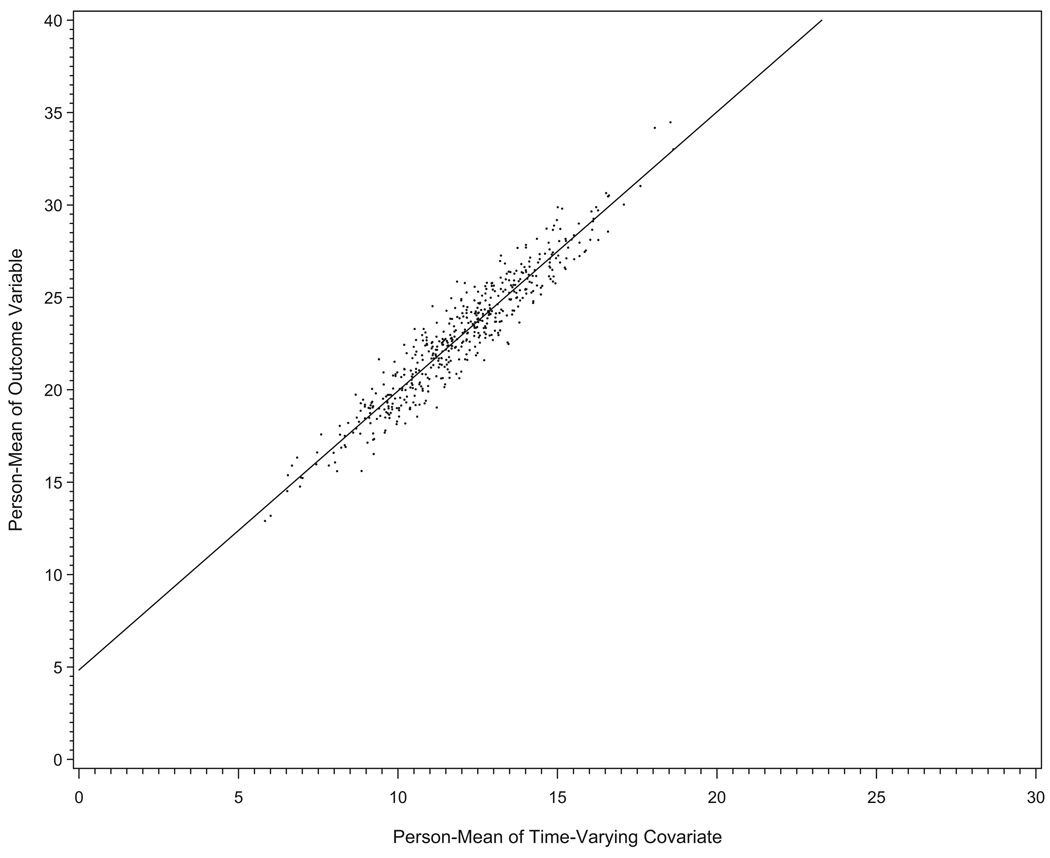

One way to get a better visual sense of these two effects is to plot the relationships observed at each level of analysis. Note that we are only using these plots to visually examine potential differences in levels of effect, and we will formally test these disaggregated effects through the parameterization of the multilevel model. To see the within-person effect, we can plot outcome yti against the person-mean centered żti; to see the between-person effect, we can plot the person-means ȳi against the person-means z̄i. Figure 5 presents the person-mean centered TVC plotted against the outcome, and Figure 6 presents the person-mean of the TVC plotted against the person-mean of the outcome.

Figure 5.

The bivariate distribution between the outcome (yti) and the person-mean centered time-varying covariate (żti).

Figure 6.

The bivariate distribution between the person-mean of the outcome (ȳi) and the person-mean of the time-varying covariate (z̄i).

These plots clearly reflect the strong negative within-person relation between the time-specific measure of the TVC and the outcome (Figure 5) and the strong positive between-person relation between the mean of the TVC and the mean of the outcome (Figure 6). This is of course precisely how we generated these data. We now use the techniques described above to obtain estimates of the between- and within-person effects via the multilevel model, in which zbi = z̄i and zwti = żti are included as separate predictors of yti.

To do this, we fitted a multilevel model consistent with Equation 13 to formally test the between- and within-person influences of the TVC. Recall that 500 individuals were each assessed nine times, resulting in a total of 4500 person-time observations. We fitted a two-level model under full information maximum likelihood and obtained an estimate of the within-person effect of γ̂10 = −0.99 (se = 0.008) and of the between-person effect of γ̂01 = 1.51 (se = 0.022). Recall that the corresponding population values were γ10 = −1.0 and γ01 = 1.5, respectively; thus, as expected, we closely replicated these values in our artificial sample.6 Continuing with our hypothetical example, these results would reflect that, on average, people reporting higher overall levels of anxiety tended to drink more alcohol; but at the very same time, on average, people tended to drink less alcohol on days when they reported higher levels of anxiety. This nicely highlights that the first conclusion made with respect to between individual differences, and the second conclusion is made with respect to within individual differences.

As we fully expected based on prior analytic theory, the person-mean centering approach accurately recovered the known population-generating values. However, although comforting, this is at best a modest victory. That is, we generated a population model consistent with Equations 13 and 16, and then we fit a sample model that corresponded to these same generating equations. Had we found anything other than these results, you would do well to suspect that we made an error in our computer programming. However, we view this as an important endeavor in that it demonstrates that the existing methods work properly when the underlying assumptions are met. Further, it gooses us to think more carefully about the specific conditions under which person-mean centering is a valid method for disaggregating multiple levels of effect.

Disaggregation of Effects with Growth in the TVC and Time is Balanced

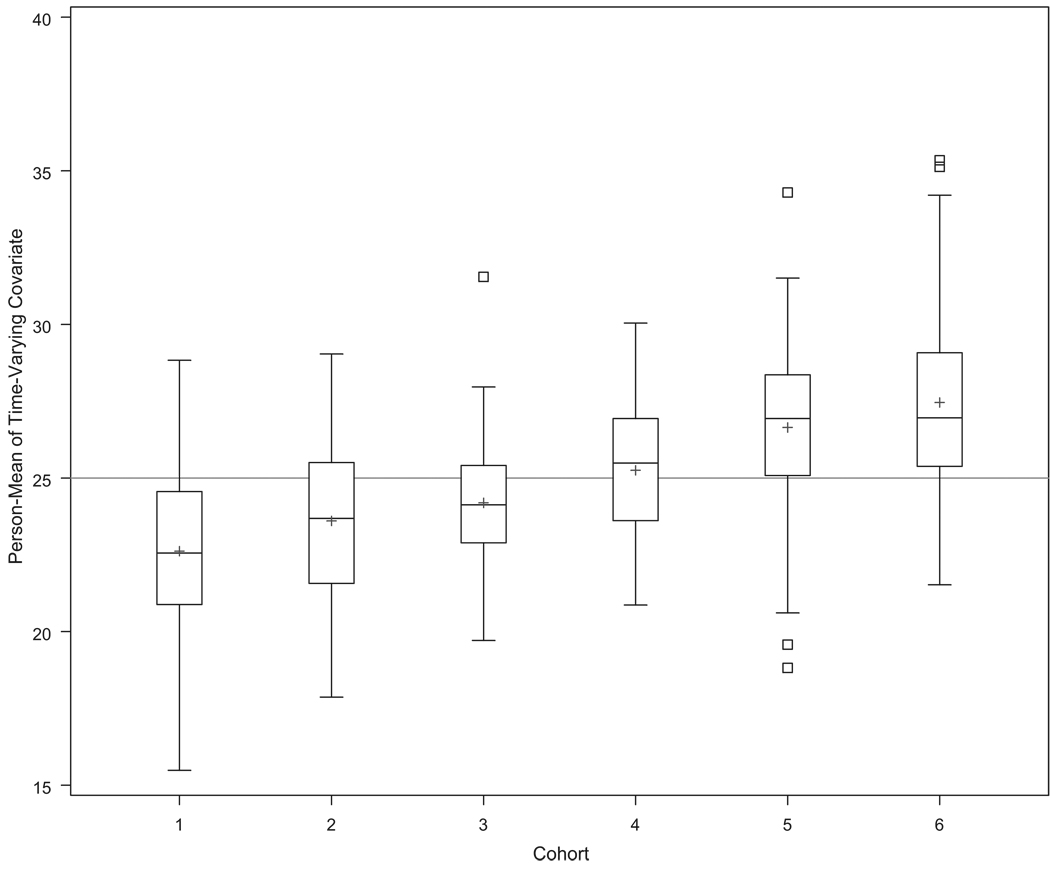

The second situation we consider is when there are both fixed and random effects of growth underlying the TVC and the design is balanced on time (i.e., Equation 30). Extending our hypothetical example, we remain interested in studying the relation between anxiety and alcohol use. However, we now want to consider the situation in which anxiety is not only increasing over time, but there are also individual differences in both starting point and rate of change. We thus defined a linear growth model to underlie the TVC itself based on the same sample size (N = 500) and same number of time points (T = 9) as before. The TVC in this second data set was defined to have an intercept equal to 25.0 and a linear slope equal to 1.0; these are arbitrary values, but they define a linear growth trajectory for the TVC. Further, we coded time so that the middle point was equal to zero, meaning that that the intercept is defined as the mean of the outcome at the mean of time, and the TVC increased in value by one unit with each unit increase in time. Finally, we allowed for individual variability (that is, random effects) in both the starting point (τ00 = 4) and rate of change over time (τ11 = 1) and a level-1 residual equal to σ2 = 1.

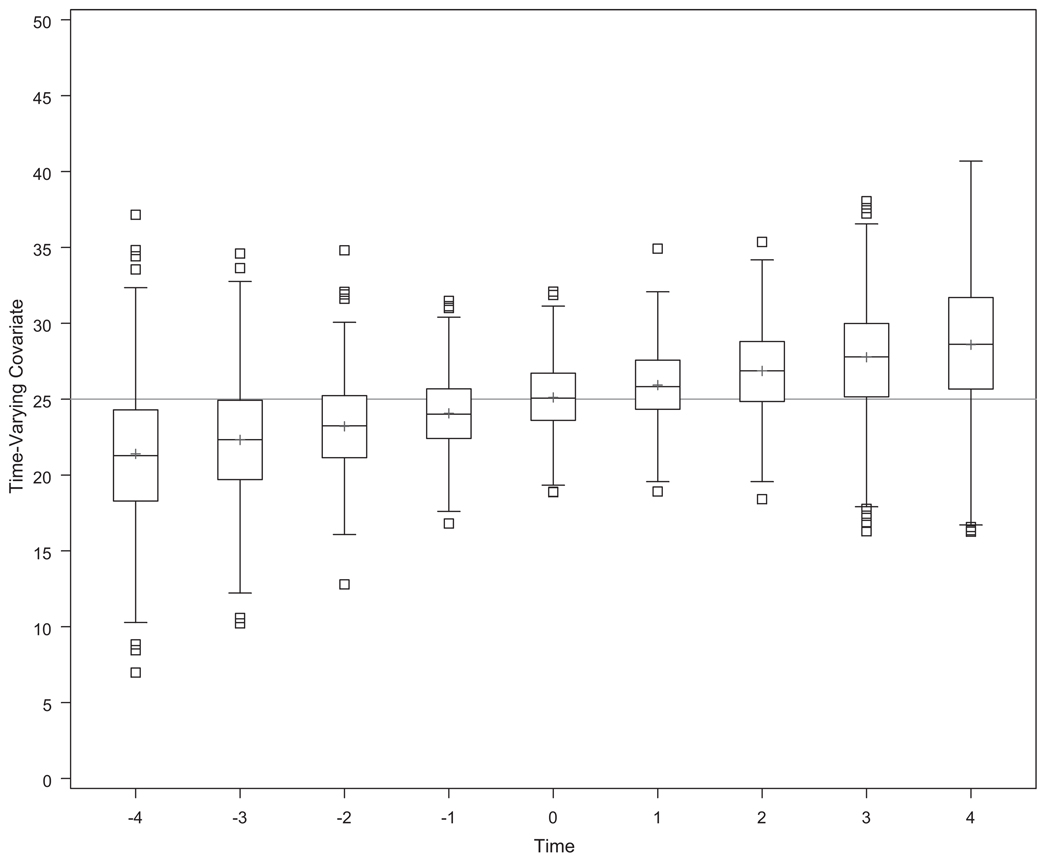

To better illustrate the implications of the inclusion of this time trend, Figure 7 presents the conditional distributions of the TVC as a function of time. It is clear that the time-specific means are (as we intended) increasing as a function of time. Further, note that the variance of the TVC varies as a function of time; this is also consistent with our population-generating model because there is a random slope component that differentially influences time-specific variability over time. In terms of our hypothetical example, both the mean and variance of anxiety are changing as a function of time; the mean is increasing linearly, and the variance is changing quadratically.

Figure 7.

The time-specific distributions of the TVC (zti) for the second artificial data set.

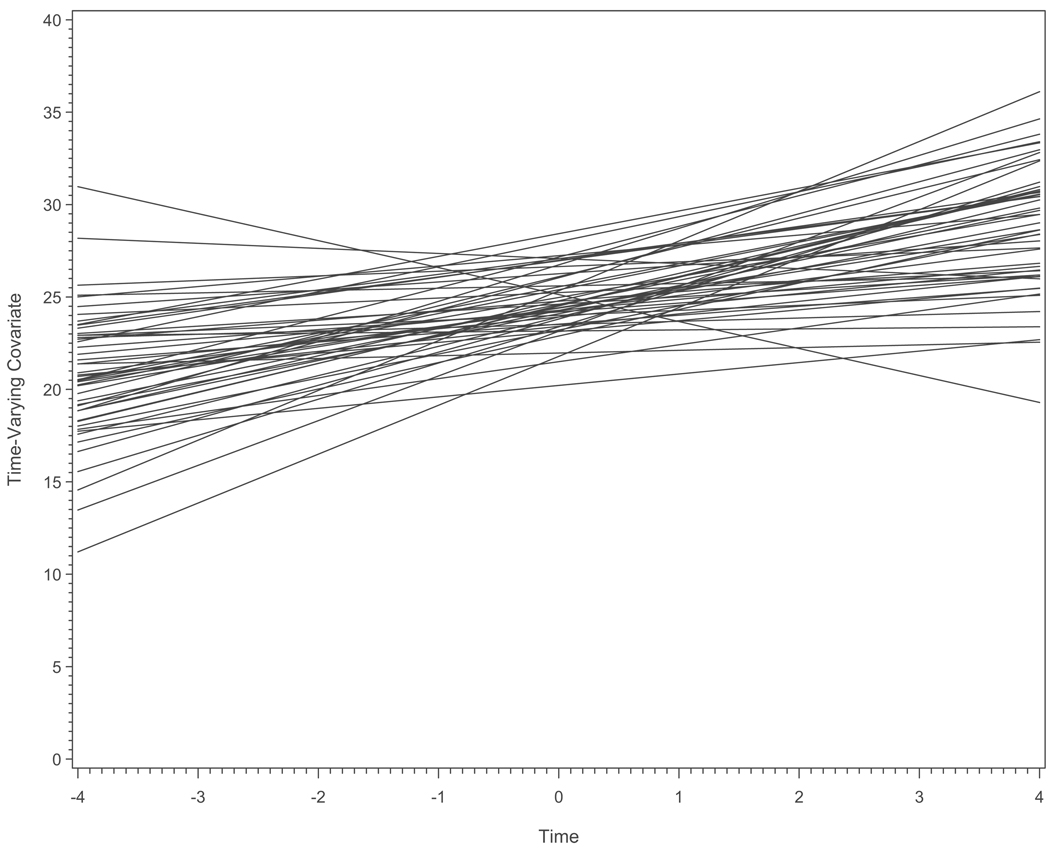

To see the influence of the random components on growth, in Figure 8 we present the individual model-implied trajectories of the TVC for 50 randomly drawn cases. This highlights not only the systematic increase in the TVC over time, but also the individual variability in starting point and rate of change. You can consider each of these lines as an individual’s own trajectory of anxiety symptoms unfolding over the period of observation. On a related point, note that each trajectory spans the entire period of time, reflecting that these data are balanced with respect to time. Finally, relevant to later analysis, note that the relative rank ordering of values on the outcome changes over time. To see this, picture drawing a vertical line at each value of time; because the slopes are not parallel, the individual standing on the TVC varies at each vertical line drawn at a given value of time.

Figure 8.

Model-implied growth trajectories for the TVC (i.e., zti) over time for 50 randomly drawn observations from the second artificial data set.

However, why would the systematic relation between the TVC and time potentially undermine the validity of the person-mean centering approach? Although we showed this analytically above (i.e., Equation 33), this threat to validity can be saliently visualized when examining the distribution of the TVCs over time for an individual case. In Figure 9, the TVC is plotted on the y-axis, time is plotted on the x-axis, and the horizontal line demarcates the person-specific mean of the set of TVCs. However, the positively sloped line is the regression line of best fit linking the TVC to time. This is consistent with the increasing value of the TVC associated with the passage of time; that is, the hypothetical individual is reporting progressively higher values of anxiety at each time point.

Figure 9.

The time-specific values of the TVC over time for a randomly drawn case from the second artificial data set.

Importantly, note that the person-mean centering strategy deviates each TVC relative to the horizontal line because of the implicit assumption that the value of the TVC is independent of time. Yet it is clear from this plot that person-mean centering fails to differentiate within-person fluctuations around the time trend. Using existing standard methods, all of the values of the TVC falling below the person-mean receive a negative deviated score, and all of the values falling above the person-mean receive a positive deviated score. These values are incorrect for obtaining a sample estimate of the within-person variability of the TVC over time. Instead, we must deviate the time-specific values of the TVC not from the horizontal line but instead from the positively sloped regression line. Only this will properly isolate the within-person component of the TVC.

To demonstrate this, we first applied the standard methods for disaggregating the between- and within-person effects of the TVC on the outcome. Given that the TVC was generated to be related to time yet the standard methods assume no relation to time, we a priori expect these results to be biased. To evaluate this, we fitted precisely the same person-mean centered model to the second data set as we did to the first. Although in the first data set we nearly perfectly recovered the corresponding population parameters, this did not occur here.

The person-mean deviated TVC resulted in a highly biased estimate of the within-person effect. Specifically, the within-person effect was estimated to be γ̂01 = −0.07 (se = 0.006), whereas the corresponding population value was γ10 = −1.0. Thus, applying the standard methods of person-mean centering to data in which the TVC varies as a function of time results in a within-person effect that drastically underestimates the known population value. In our hypothetical example, we would conclude that there was indeed a negative within-person effect, yet we would underestimate the magnitude of this effect by 93%. This is a striking amount of bias that occurs even under what are otherwise ideal conditions (e.g., large sample size, large numbers of repeated measures, no missing data).

In contrast to the highly biased within-person effect, we accurately recovered the population between-person effect; our obtained value was γ̂10 = 1.49 (se = 0.029), whereas the corresponding population value was γ10 = 1.5. To better understand this accurate recovery, recall that we generated the TVC such that the mean of time was equal to zero (i.e., time was centered around zero). As such, because this condition is balanced, x̄i = x̄ = 0 for all individuals. Thus the omitted second set of terms in Equation 32 (i.e., [γ10 + û1i]x̄i), drops out and the person-mean accurately recovers the between-person effect. Note, however, that this is strictly a function of the balanced design. If time were unbalanced (e.g., if there were missing data or a cohort-sequential design), then the person-mean would not accurately capture the between-person effect in this situation. Indeed, we demonstrate just this point in the next example.

Whereas in the balanced case the person-specific mean of time (x̄i) is constant over individual, the deviation of the individual value of time from the mean (xti − x̄i) is not. Thus the traditional method neglects the term (γ10 + û1i)(xti − x̄i) from Equation 33 in the calculation of the time-specific deviation of zti from the person-mean. This is why our sample estimate of the within-person effect was equal to −0.07 when the corresponding population value was equal to −1.0. Fortunately, though, we can draw on our prior developments to obtain an unbiased estimate of this known population effect.

To do this, we need a person-specific estimate of γ10 + u1i to use in the calculation of zwti. More specifically, instead of deviating the time-specific TVC measures with respect to the person-mean, we can deviate the TVCs with respect to the individual-specific regression line linking the TVC and time. This strategy can be more clearly understood by reconsidering Figure 9. Here we plotted the TVCs against time for a single individual, and we superimposed both a horizontal line representing the person-mean and the best-fitting regression line estimating the positive relation between time and the TVC. Whereas the traditional person-mean centering approach deviates the TVC with respect to the horizontal line, we can instead deviate the TVC with respect to the regression line. We refer to this strategy as detrending.

The general concept of detrending is far from novel, and it has been used in various forms in time-series analysis for decades (e.g., Chatfield 1996). However, to our knowledge there has been no prior discussion of applying these techniques in the multilevel model in order to disaggregate between- and within-person effects of a TVC on the outcome when the TVC itself is related to time. Our proposed approach for detrending is simple. We first regress the TVC on time separately for each individual using ordinary least squares (OLS). We then deviate each time-specific TVC not from the overall person-mean (as is done in the traditional approach) but instead from the model-implied value of the TVC specific to that particular unit of time. In other words, our deviated TVC measure is simply the residual (i.e., the observed minus expected value) from the regression of the TVC on time computed separately for each individual case.

We can present this more formally as a one-predictor regression equation estimated separately (case by case) for each individual in the sample. This is given as

| (36) |

where zti is the time-specific measure of the TVC, xti is the measure of time, b0i and b1i are sample estimates of the intercept and the slope of the regression of the TVC on time, respectively, and eti is the time-specific residual.7 A trivial rearrangement of this equation shows that

| (37) |

where eti is the detrended rescaling of the TVC. In other words, the residual eti is computed by deviating the time-specific TVC from the model-implied value of the TVC that includes information about the specific value of time. Thus the TVC is deviated not relative to the horizontal line but instead relative to the regression line. We now define zwti as eti.

An interesting generalization can be seen here as well. We could fit the OLS regression of the TVC on time defined in Equation 36 to our initial artificial data set in which the TVC was unrelated to the passage of time. Given the structure of the data, there would be no b1xti term in Equation 36, and this would simplify to

| (38) |

and the deviation of the TVC would be

| (39) |

which is precisely equal to the traditional person-mean centering approach we first described (because b0i = z̄i when there are no predictors in the regression equation). However, the more general conclusion is that the person-mean centering approach is equivalent to detrending but under the implicit assumption that there is no relation between the TVC and time, and thus b1i is zero for all cases. Here we simply extend this approach to allow b1i to take on some nonzero value from the data.

To examine the utility of this approach, we detrended the TVC in the second data set with respect to the regression line fitted to each case individually.8 Once detrended, we then used this rescaling of the TVC in precisely the same way as before; namely, we included the detrended TVC as the level-1 predictor (zwti), and we retained the OLS intercept from Equation 36 as the level-2 predictor (zbi). Because in this balanced condition the OLS intercept is equal to the person-mean used in our initial model that we fitted to these data, we get the same estimate of the between-person effect as we did before: γ̂ =1.49 (se = 0.029). However, whereas our prior estimate of the within-person effect was highly biased when using the person-mean centered TVC, we recover this with near-precision using the detrended TVC: γ̂ = −0.99 (se = 0.018). These results demonstrate that when the TVC is systematically related to the passage of time, it is critical that the TVC be deviated not with respect to the person-mean but instead with respect to the individual-specific regression linking the TVC and time.

In sum, this second artificial data set was generated so that there was a random growth process underlying the TVC. However, this was embedded in the unrealistic condition of complete and balanced data. Our third and final data example considers the same growth model for the TVC but embedded in a more realistic condition of unbalanced time.

Disaggregation of Effects with Growth in the TVC and Time is Unbalanced

An important characteristic of the first two artificial data sets is that each simulated subject was followed for precisely the same nine time periods. This is consistent with a birth-cohort design in which an entire cohort of individuals is assessed at the same age at each assessment period and there are no missing data. Because we numerically coded time to range from −4 to 4, the mean value (or midpoint) of time is equal to 0 for each of the 500 individuals. As such, every single person has the same mean of time, equal to zero. The person-mean of the TVC cannot then covary with the person-mean of time because all person-mean values of time are equal for all individuals.

However, as we described above, the time-balanced birth-cohort design is rare in many behavioral science research applications. Instead, multiple cohorts are often considered simultaneously, whether intentionally by design (e.g., one sample of 5-year-olds is recruited, one sample of 6-year-olds is recruited, etc.) or unintentionally by happenstance of the distribution of age within each assessment (e.g., inclusion criteria include children 5 to 9 years of age at first assessment). Further, given that missing data are endemic in longitudinal social science research, even a true birth cohort design will typically be unbalanced.