Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the likelihood of, and factors associated with, recovery from exhaustion in older adults

Design and Setting

Retrospective analysis of data from six annual examinations of a community-based cohort study

Participants

4584 men and women aged 69 years or older

Measurements

Exhaustion was considered present when a participant responded “a moderate amount” or “most of the time” to either of two questions: “How often have you had a hard time getting going?” and “How often does everything seem an effort?”

Results

Of the 964 participants who originally reported exhaustion, 634 (65.8%) were exhaustion-free at least once during follow up. When data from all time points were considered, 48% of exhaustion-reporters were exhaustion-free the following year. After adjustment for age, sex, race, education, and marital status, one-year recovery was less likely among individuals with worse self-rated health, ≥ six medications, obesity, depression, musculoskeletal pain, and history of stroke. In proportional hazards models, the following risk factors were associated with more persistent exhaustion over five years: poor self-rated health, ≥ six medications, obesity, and depression. Recovery was not less likely among participants with a history of cancer or heart disease.

Conclusion

Exhaustion is common in old age but is quite dynamic, even among those with a history of cancer and congestive heart failure. Recovery is especially likely among seniors who have a positive perception of their overall health, take few medications, and are not obese or depressed. These findings support the notion that resiliency is associated with physical and psychological well-being.

Keywords: symptoms, frailty, fatigue, transition analysis

INTRODUCTION

Exhaustion, which is the perception of inadequate energy levels to meet one's demand, is a commonly reported symptom among older adults and is associated with diminished quality of life and adverse health outcomes(1-4). Exhaustion is related to other self-reported symptoms such as fatigue and tiredness, which have been shown to predict mortality and poor physical function in older adults(5-7). As operationalized in the Cardiovascular Health Study, exhaustion is a key component in the geriatric syndrome of frailty(8, 9),which predisposes individuals to higher rates of mortality, health care utilization, and disability(9-13). Observational data have suggested that exhaustion and weight loss tend to develop later than other components of frailty, and may identify people at greatest risk for subsequent rapid decline(14).

Despite the frequency and negative consequences of self-reported exhaustion in the elderly, as well as the subjective burden associated with limited energy reserve, little is known about how exhaustion persists or remits over time, and what clinical factors may predict recovery from exhaustion. Although existing literature and clinical judgment provide some insights about what sorts of patients are likely to have exhaustion(9, 15), factors associated with recovery could differ and must be addressed longitudinally. Using data from a large observational study of older adults, we estimated the likelihood of, and factors associated with, recovery from exhaustion over six years. The findings can be used by clinicians for prognostic purposes and suggest potentially modifiable factors which could guide efforts at reducing exhaustion, thereby improving quality and perhaps quantity of life in older adults. Understanding the dynamics and potential underpinnings of important geriatric symptoms such as exhaustion is a necessary step in maximizing health and quality of life for an aging population.

METHODS

Participants

The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) is a population-based observational study that recruited persons who were 65 years of age or older at enrollment from four communities in the United States: Sacramento County, CA; Allegheny County, PA; Forsyth County, NC; and Washington County, MD. Details of the study design and sampling methods have been described elsewhere (16, 17). Potential participants were excluded if they were institutionalized, non-ambulatory in their home, unable to be interviewed, receiving hospice care, receiving radiation or chemotherapy for cancer, or not expected to remain in the area for three years. The original cohort included 5201 men and women enrolled between 1989 and 1990. To improve minority representation, an additional 687 African-Americans were recruited between 1992 and 1993. Participants received annual examinations until 1999. To make use of the most recent data, the analyses presented here are restricted to data collected from 1993/94 through 1998/99; hereafter, we refer to the 1993/94 data collection wave as “baseline.” The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at each site and this analysis was approved by the IRB at the University of Washington, where the analysis was conducted. The study was compliant with the ethical rules for human experimentation that are stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measurements

Exhaustion

Consistent with the CHS frailty index(9), we identified exhaustion using two items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale(18), “How often have you had a hard time getting going?” and “How often does everything seem an effort?” Participants who responded “A moderate amount of time” or “Most of the time” to either question were classified as exhausted, whereas those who answered either “Rarely or none of the time” or “Some or a little of the time” to both questions were classified as not exhausted.

Predictor Variables

Age in years was calculated from date of birth. Sex, race (white or non-white), marital/partnered status, and education level (number of years of school) were determined by self report. In addition to these sociodemographic variables, we selected nine health-related factors which were available in the dataset and which we hypothesized might be 1) direct contributors to low energy reserve (and thus to the subjective symptom of exhaustion) or 2) general markers of poor health (and thus identify individuals with less potential for resiliency). Recognizing that almost any clinical factor could potentially contribute to the persistence of exhaustion, our variable selection emphasized conditions in which exhaustion has been frequently described (cancer, heart disease, depression, stroke)(19-22) and health factors that are potentially modifiable (depression, obesity, polypharmacy, pain). We selected self-rated health as an easily reproducible measure of overall well-being, which may hold prognostic value for clinicians.

Self-rated health was determined by asking participants, “Would you consider your health in general to be excellent, very good, good, fair or poor?” Number of medications was determined by patient report and by transcribing labels from participants’ pill bottles during annual examinations, a method which has been found to be highly reliable(23). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from measured height and weight as follows: weight in kilograms / (height in meters)2. Depression was assessed by a modified CES-D score, which used eight items from the CES-D, excluding the two items used to detect exhaustion(18, 24, 25). Musculoskeletal pain was assessed with a single yes/no question about pain in any bones or joints. Participants reported at baseline whether they had ever been diagnosed by a physician with cancer, and self-report of physician diagnosis of cancer was assessed yearly. Coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, and stroke were adjudicated outcomes which were assessed by self-report and also confirmed by review of medications and medical record and modified over the years to reflect the newest and most accurate information about the presence or absence of diagnosis at each time point(26).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the cohort at baseline (1993/94). Exhaustion status was re-assessed annually. Of the participants who were exhausted at baseline, we calculated the percentage that were alive and without exhaustion for at least one of the five subsequent examinations (at least partial remission).

We then examined data from all available one-year transitions during the five years of the study. There were 20,112 available one-year transitions, meaning that the participant was alive at a given year and sufficient data were available the following year to classify the participant as exhausted, not exhausted, or dead. We computed the one-year probability of transition between states of exhaustion, no exhaustion, and death(27). Next, we examined those one-year transitions for which the participant was exhausted at the beginning of the transition and alive the following year, so that he or she could be classified as either still exhausted or no longer exhausted (N=4639 transitions). Using generalized estimating equations and grouping by subject identifier in order to account for multiple observations on the same individuals, we estimated the effects of the potential predictor variables on the one-year likelihood of transitioning from a state of exhaustion to no exhaustion. The transition probability analysis uses contemporaneous values of the predictor variables, which were updated during annual examinations.

Next, we performed a survival analysis among those participants who were exhausted at baseline. With censoring at death or drop-out, we modeled the time to first remission from exhaustion. Using Cox proportional hazards models, we estimated the association between predictor variables (determined at baseline) and time to first remission from exhaustion. For both the transition probability analysis and the Cox proportional hazards analysis, we constructed models that included only the sociodemographic variables which were age, race, sex, marital status and education (Model 1), models that included each health-related factor individually after adjusting for sociodemographic variables (Model 2) and models that adjusted for sociodemographic variables and all health-related factors simultaneously (Model 3). Analyses were conducted with Stata version 9.0 (College Station, TX), and SPSS version 11.5.0 (Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Exhaustion was present in 964 (21.0%) of the 4584 participants surveyed at the index year (1993/94). At that time, the cohort had a mean age of 77.8 years and 59.3% were women. Participants who reported exhaustion were older and more likely to be female, non-white, non-married and have fewer years of formal education (Table 1). Exhaustion reporters had poorer self-rated health, more medications, and more depressive symptoms. They were more likely to be obese, to report pain, and to have diagnoses of coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, and stroke.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Cohort at Baseline (1993/1994)

| Characteristic | Participants without Exhaustion N=3620 | Participants with Exhaustion N=964 | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, N (%) Women | 2081 (57.5%) | 639 (66.3%) | 0.002 |

| Age in Years, Mean ± SD† | 77.0 (5.1) | 78.1 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Race, N (%) White | 3077 (85.0%) | 746 (77.3%) | <0.001 |

| Marital Status, N (%) | |||

| Married/partnered | 2305 (63.7%) | 508 (52.7%) | <0.001 |

| Education (N = 4575‡) | |||

| <HS§, N (%) | 877 (24.3%) | 336 (34.9%) | < 0.001 |

| HS, N (%) | 1002 (27.7%) | 252 (27.2%) | 0.312 |

| Some College, N (%) | 904 (25.0%) | 213 (22.1%) | 0.189 |

| College grad, N (%) | 830 (23.0%) | 161 (16.7%) | 0.039 |

| Self-Rated Health (N=4571) | |||

| Excellent / Very Good, N (%) | 1452 (40.2%) | 165 (17.2%) | <0.001 |

| Good, N (%) | 1592 (44.1%) | 390 (40.6%) | 0.312 |

| Fair / Poor, N (%) | 567 (15.7%) | 405 (42.2%) | <0.001 |

| No. of Medications (N=4574) | |||

| 0, N (%) | 691 (19.1%) | 120 (12.5%) | 0.039 |

| 1-2, N (%) | 1334 (36.9%) | 262 (27.4%) | 0.001 |

| 3-5, N (%) | 1200 (33.2%) | 365 (38.0%) | 0.048 |

| >=6, N (%) | 388 (10.7%) | 214 (22.3%) | <0.001 |

| Body Mass Index (N=4582) | |||

| Underweight, <= 18.5, N (%) | 46 (1.3%) | 10 (1.0%) | 0.476 |

| Normal weight, 18.5 – 25, N (%) | 1334 (36.9%) | 323 (33.5%) | 0.131 |

| Overweight, 25 – 30, N (%) | 1559 (43.1%) | 383 (39.8%) | 0.118 |

| Obese, >30, N (%) | 680 (18.8%) | 247 (25.6%) | 0.011 |

| Depression symptoms: Modified CES-D Score¶ (N=4454) | |||

| None/Few, <= 4, N (%) | 3037 (85.8%) | 470 (51.3%) | <0.001 |

| Some, 5-10, N (%) | 400 (11.3%) | 247 (27.0%) | <0.001 |

| Significant, >10, N (%) | 101 (2.9%) | 199 (21.7%) | <0.001 |

| N (%) with Musculoskeletal Pain (N=4426) | 1293 (37.0%) | 494 (53.2%) | <0.001 |

| N (%) with Cancer (N=4555) | 172 (4.8%) | 63 (6.6%) | 0.291 |

| N (%) with Coronary Heart Disease | 807 (22.3%) | 290 (30.1%) | 0.004 |

| N (%) with Congestive Heart Failure | 228 (6.3%) | 130 (13.5%) | 0.007 |

| N (%) with Stroke | 199 (5.5%) | 105 (10.9%) | 0.036 |

P-values of comparisons between groups defined by t-tests and X2 tests.

SD = standard deviation

N for a particular variable is noted when it differs from N=4584 due to missing values

HS = high school

Modified CES-D = Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale, excluding 2 items used to define exhaustion

Of the 964 participants who reported exhaustion at baseline, 634 (65.8%) were exhaustion-free at least once during the follow-up period. Of the 330 participants who reported exhaustion at baseline and never had a documented year free of exhaustion, 90 (27.3%) lacked any additional observations because of death or drop-out whereas 240 (72.7%) continued to report exhaustion at every remaining year until death (N=138) or end of study (N=102). Of the 138 who reported exhaustion until their death, the median time to death was 3.3 years.

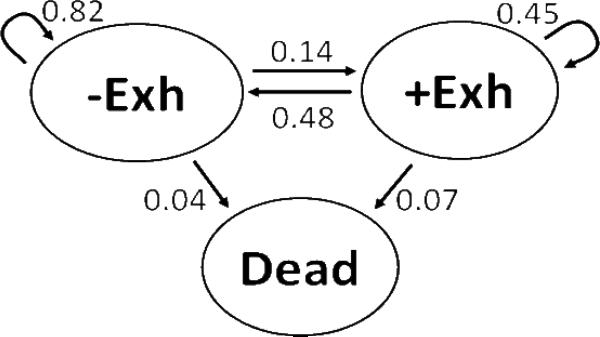

Recovery at One Year

Figure 1 shows the one-year probability of transition among the states of exhaustion, no exhaustion, and death based on 20,112 available transitions. The arrows represent the likelihood that a subject who starts as either exhausted or not exhausted would remain in that state or transition to another state one year later. When data from all available one-year transitions were considered, 82% of those who were not exhausted remained exhaustion-free the next year, 14% became exhausted, and 4% died. In contrast, 48% of those reporting exhaustion were exhaustion-free the next year, 45% remained exhausted, and 7% died.

FIGURE 1.

-Exh and +Exh represent the states of not having or having exhaustion, respectively. Arrows represent the likelihood of moving to another state or staying in the same state over a one-year interval, using data from all available one-year transitions in the five-year study.

One-year probabilities of transition between states of exhaustion, no exhaustion, and death (N=20,112 transitions)

Using data from 4639 one-year transitions in which the participant was exhausted in the first year of the transition, we examined factors associated with transitioning to a state of no exhaustion (as compared to persistent exhaustion) the following year (Table 2). Exhausted participants who were older were less likely to be exhaustion-free one year later. Adjusting for sociodemographic variables, these factors were associated with a lower likelihood of transitioning from exhaustion to no exhaustion at one year: worse self-rated health, more medications, obesity, greater depressive symptoms, musculoskeletal pain, and a diagnosis of stroke or congestive heart failure. Adjusting for sociodemographics and the potential health-related predictors simultaneously, congestive heart failure was no longer a significant predictor of recovery.

Table 2.

Predictors of Transition from a State of Exhaustion to No Exhaustion the Following Year (N=4639 transitions*)

| Model 1† Predictors | Odds Ratio (95% CI¶) | P value | Model 2‡ Predictors | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value | Model 3§ Predictors | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 1.13 (0.94-1.35) | 0.19 | Self-rated health | Self-rated health | ||||

| Age (per year) | 0.98 (0.97-1.00) | 0.01 | Excellent/Very Good | Reference | Excellent/Very Good | Reference | ||

| White | 1.05 (0.84-1.31) | 0.68 | Good | 0.66 (0.51-0.84) | 0.001 | Good | 0.73 (0.57-0.95) | 0.02 |

| Married / partnered | 1.11 (0.93-1.34) | 0.26 | Fair/Poor | 0.34 (0.26 -0.44) | <0.001 | Fair/Poor | 0.46 (0.35-0.61) | <0.001 |

| Education (per grade) | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 0.19 | No. of medications | No. of medications | ||||

| 0 | Reference | 0 | Reference | |||||

| 1-2 | 0.67 (0.49-0.91) | 0.01 | 1-2 | 0.76 (0.55-1.04) | 0.09 | |||

| 3-5 | 0.59 (0.43-0.81) | 0.001 | 3-5 | 0.77 (0.56-1.07) | 0.13 | |||

| ≥ 6 | 0.30 (0.20-0.44) | <0.001 | ≥ 6 | 0.47 (0.31-0.73) | 0.001 | |||

| Body Mass Index | Body Mass Index | |||||||

| < 18.5 | 0.59 (0.24-1.47) | 0.26 | < 18.5 | 0.57 (0.23-1.37) | 0.21 | |||

| 18.5 -24.9 | Reference | 18.5 -24.9 | Reference | |||||

| 25-30 | 0.81 (0.65-1.02) | 0.08 | 25-30 | 0.82 (0.65-1.02) | 0.07 | |||

| >30 | 0.55 (0.43-0.71) | <0.001 | >30 | 0.62 (0.48-0.80) | <0.001 | |||

| Depression Score# | Depression Score | |||||||

| <5 | Reference | <5 | Reference | |||||

| 5-10 | 0.67 (0.55-0.81) | <0.001 | 5-10 | 0.79 (0.65-0.97) | 0.02 | |||

| >10 | 0.36 (0.28-0.45) | <0.001 | >10 | 0.43 (0.33-0.55) | <0.001 | |||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 0.61 (0.51-0.71) | <0.001 | Musculoskeletal pain | 0.68 (0.56-0.84) | <0.001 | |||

| Cancer | 0.88 (0.59-1.31) | 0.52 | Cancer | 0.96 (0.65-1.41) | 0.84 | |||

| Coronary heart disease | 0.86 (0.70-1.06) | 0.17 | Coronary heart disease | 1.18 (0.95-1.47) | 0.13 | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 0.72 (0.54-0.95) | 0.02 | Congestive heart failure | 1.03 (0.76-1.38) | 0.87 | |||

| Stroke | 0.59 (0.44-0.81) | 0.001 | Stroke | 0.71 (0.53-0.97) | 0.03 |

Includes all one-year transitions in which participant is exhausted the first year and alive the following year

Model 1 includes sociodemographic variables

Model 2 includes sociodemographic variables and each predictor is included separately

Model 3 is fully adjusted and includes sociodemographic variables and all predictor variables

CI=confidence interval

Depression score refers to score on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale after excluding the two items used to define exhaustion

Time to First Remission

The hazards ratios shown in Table 3 indicate that the time to first remission from exhaustion was less favorable among participants with poor self-rated health, more medications, obesity, significant depression symptoms, and musculoskeletal pain. With borderline significance, stroke and coronary heart disease were also associated with worse recovery patterns. In models adjusted for all the covariates (Model 3), factors that remained significantly associated with longer time to remission were worse self-rated health, six or more medications, obesity, and significant depression symptoms.

Table 3.

Predictors of Time to Remission of Exhaustion in Cox Proportional Hazards Models*

| Model 1† Predictors | Hazards Ratio (95% CI¶) | P value | Model 2‡ Predictors | Hazards Ratio (95% CI) | P value | Model 3§ Predictors | Hazards Ratio (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 0.95 (0.80, 1.13) | 0.57 | Self-rated health | Self-rated health | ||||

| Age (per year) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.29 | Excellent/Very Good | Reference | Excellent/Very Good | Reference | ||

| White | 0.93 (0.75, 1.16) | 0.53 | Good | 0.76 (0.62-0.93) | 0.01 | Good | 0.79 (0.64-0.97) | 0.03 |

| Married / partnered | 1.06 (0.88, 1.28) | 0.52 | Fair/Poor | 0.56 (0.45-0.70) | <0.001 | Fair/Poor | 0.66 (0.51-0.85) | 0.001 |

| Education (per grade) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.25 | No. of medications | No. of medications | ||||

| 0 | Reference | 0 | Reference | |||||

| 1-2 | 0.78 (0.61-1.00) | 0.05 | 1-2 | 0.79 (0.61-1.02) | 0.08 | |||

| 3-5 | 0.72 (0.57-0.92) | 0.01 | 3-5 | 0.79 (0.61-1.03) | 0.08 | |||

| ≥ 6 | 0.52 (0.39-0.69) | <0.001 | ≥ 6 | 0.60 (0.42-0.85) | 0.004 | |||

| Body Mass Index | Body Mass Index | |||||||

| < 18.5 | 0.82 (0.33-2.01) | 0.66 | < 18.5 | 0.94 (0.38-2.35) | 0.89 | |||

| 18.5 -24.9 | Reference | 18.5 -24.9 | Reference | |||||

| 25-30 | 0.91 (0.76-1.10) | 0.32 | 25-30 | 0.93 (0.77-1.12) | 0.43 | |||

| >30 | 0.74 (0.59-0.92) | 0.01 | >30 | 0.78 (0.62-0.98) | 0.03 | |||

| Depression Score# | Depression Score | |||||||

| <5 | Reference | <5 | Reference | |||||

| 5-10 | 0.90 (0.75-1.09) | 0.30 | 5-10 | 0.99 (0.81-1.20) | 0.90 | |||

| >10 | 0.63 (0.51-0.79) | <0.001 | >10 | 0.71 (0.57-0.90) | 0.004 | |||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 0.77 (0.68-0.91) | 0.002 | Musculoskeletal pain | 0.88 (0.74-1.05) | 0.16 | |||

| Cancer | 0.87 (0.61-1.26) | 0.47 | Cancer | 0.96 (0.67-1.39) | 0.84 | |||

| Coronary heart disease | 0.85 (0.71-1.01) | 0.07 | Coronary heart disease | 1.02 (0.84-1.25) | 0.82 | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 0.84 (0.65-1.08) | 0.18 | Congestive heart failure | 1.12 (0.84-1.48) | 0.44 | |||

| Stroke | 0.76 (0.57-1.01) | 0.05 | Stroke | 0.87 (0.64-1.18) | 0.37 |

Includes all one-year transitions in which participant is exhausted the first year and alive the following year

Model 1 includes sociodemographic variables

Model 2 includes sociodemographic variables and each predictor is included separately

Model 3 is fully adjusted and includes sociodemographic variables and all predictor variables

CI=confidence interval

Depression score refers to score on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale after excluding the two items used to define exhaustion

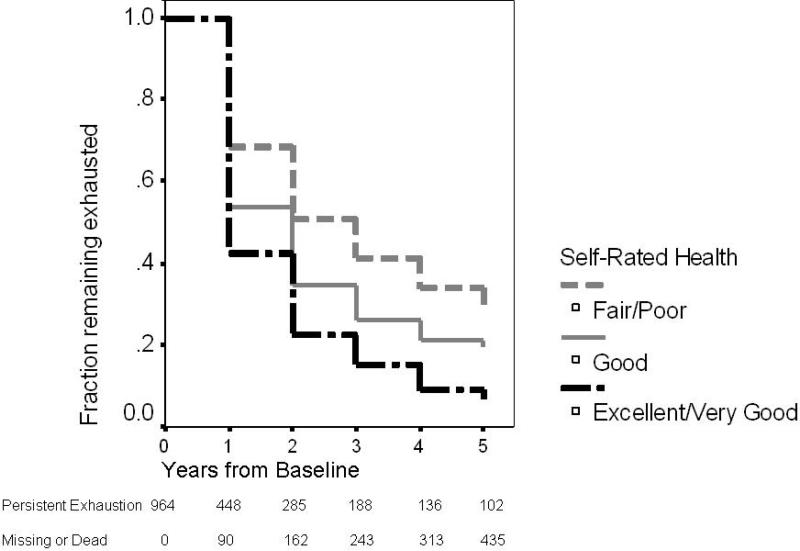

In the analyses presented in Tables 2 and 3, the factor that had the most consistent and robust association with likelihood of recovery from exhaustion was self-rated health. The survival curves in Figure 2 reflect the effects of self-rated health, measured at baseline, on the likelihood of remission of exhaustion over the next 5 years.

FIGURE 2.

The survival analysis includes the 964 participants who were exhausted and baseline and models time to first remission of exhaustion, with censoring for death or loss to follow-up.

Survival Curves Demonstrating Remission of Exhaustion over Five Years, by Self-rated Health Categories

DISCUSSION

Exhaustion was common among older adults in the Cardiovascular Health Study, but our findings indicate that exhaustion is not intractable. Although predictive of mortality, exhaustion often remits, and thus is not a pre-terminal symptom. Almost two-thirds of the participants who originally endorsed exhaustion were exhaustion-free at least one time in the next five years. For those who reported exhaustion, the symptom was absent the following year in nearly half the cases. Survival functions suggested that the majority of older adults with subjective exhaustion will experience remittance of the symptom within the next two years. Even in subjects with negative health characteristics, such as obesity, poor self-rated health, and depression, exhaustion had resolved the next year in about one in four. These findings challenge the notion that exhaustion, once present in an older adult, is likely to persist until death.

Our results suggest that recovery from exhaustion is associated with some factors which are potentially modifiable. Exhaustion was more likely to remit among participants who were not obese, reported fewer depressive symptoms, had better self-rated health, denied musculoskeletal pain, and took fewer than six medications. Although causation cannot be inferred from these results, intentional weight loss or treatment of depression may be promising means of ameliorating exhaustion for some. These findings also suggest that while treatment of pain and depression may favor resolution of exhaustion, over-medication may have the opposite effect, highlighting the importance of ongoing efforts to define and encourage appropriate use of medications for a growing population of seniors with multiple co-existing conditions(28-31). This study does not identify what factors may connect multiple medications with exhaustion. Subjects who take more medications are likely sicker, although adjusting for other measures of health, including self-rated health, did not eliminate the effects of medication burden on one-year recovery from exhaustion.

Although this construct of exhaustion is frequently used to detect the frailty syndrome(10), to our knowledge this is the first analysis to describe the transiency of exhaustion in many older adults. It has been reported that exhaustion, compared to other frailty criteria, is a less robust predictor of adverse health outcomes by itself, although it appears to strengthen the association with outcomes when aggregated with other criteria(2). Perhaps the relative weakness of exhaustion as an independent predictor of outcomes is due in part to its dynamic nature. Whereas limited or fleeting exhaustion could have a simple precipitant, persistent exhaustion may be a more specific indicator of complex physiologic disarray associated with the frailty syndrome. Frailty indices may be strengthened by altering the criteria to reflect persistent exhaustion over a specified period of time.

Although this analysis highlights several possible underpinnings of exhaustion (depression, obesity, polypharmacy), it is important to note that exhaustion is likely to be multi-factorial. Indeed, the “frailty phenotype” has been hypothesized to represent a final common pathway which may be reached through a variety of insults, diseases, or aging processes that ultimately produce physiologic dysregulation across multiple systems(32). Like many geriatric syndromes (e.g. falls, delirium, incontinence) and other components of frailty (weakness, wasting, slowness), exhaustion defies the traditional, single-disease paradigm that guides most diagnosis and treatment in medicine(28, 33, 34). Too often, “non-specific” symptoms such as exhaustion or fatigue, dizziness, or decreased appetite may be dismissed by clinicians as inevitable signs of age that lack a specific treatment. To the contrary, our results suggest that although exhaustion is common, it is far from an inevitable or an intractable feature of getting old. Our findings should encourage efforts to address the multiple potential contributors underlying an older patient's complaint of exhaustion.

Further, participants with a history of cancer and heart disease were not at a disadvantage in terms of their potential to recover from exhaustion. The diagnoses of cancer, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure and stroke were more common in participants who had exhaustion, but they were not robust indicators of the likelihood of exhaustion recovery, particularly in the fully adjusted models. To be sure, associations may have been diminished by the crudeness of the diagnosis variables, such as failure to distinguish disease severity or specific types and stages of cancer, and the fact that the study excluded individuals who were actively undergoing chemotherapy or radiation for cancer at baseline. However, the finding is consistent with other recent reports which suggest that diagnostic information alone is a poor indicator of health trajectories in older adults(35, 36).

It is also notable that those who reported exhaustion were more often female, non-white, non-married, and less educated, but these demographic and socioeconomic factors were not strong predictors of recovery from exhaustion. This may suggest that exhaustion, which is the perception of inadequate energy levels to meet one's demands, is determined in part by socioeconomic or psychosocial factors. Those with limited social or economic resources may be more likely to perceive exhaustion because they experience greater energy demands in daily life (for example, a widowed person may perform more household chores on his own or an economically disadvantaged person may live in a building that lacks an elevator). However, fluctuations in the perception of exhaustion over time may be more influenced by factors intrinsic to the older adult, such as mental and physical well-being.

Several limitations of this study may impact the interpretation of the findings. First, exhaustion was defined based on two questions from a depression scale. Although our definition is consistent with previous work on frailty(1, 9, 37-39), it is unknown whether the participants identified in this manner would have described themselves as “exhausted.” Nevertheless, this construct of exhaustion is widely used and captures a subjectively undesirable state; thus, understanding the dynamics of this construct is valuable. Second, exhaustion was assessed only once a year; thus, our estimations of rates of remission may be underestimates. Third, although the CHS dataset comprises a large, diverse cohort of older adults with meticulous longitudinal data collection on the variables of interest, the data were collected in the prior decade. It is unlikely that the observed patterns and associations related to exhaustion would have shifted substantially. Finally, as commonly occurs in longitudinal research involving older adults, we observed a high rate of death and moderate loss to follow-up. We selected analytic approaches (transition probability analysis and Cox proportional hazards analysis) which minimize survival bias.

This study advances current knowledge regarding the symptom of exhaustion in older adults as well as the related concept of frailty. Although exhaustion is more common with advancing age, the perception of inadequate energy levels is quite dynamic, and the majority of older patients with exhaustion will experience at least one point in the future without exhaustion. Participants were most likely to recover from exhaustion if they had better self-rated health, took fewer than six medications, and were not obese or depressed. These results suggest that the resiliency associated with physical and psychological well-being persists into old age.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts relevant to this research.

Conflicts of Interest Table

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [AG-023629, CHS was supported by contract numbers N01-HC-85079 through N01-HC-85086, N01-HC-35129, N01 HC-15103, N01 HC-55222, N01-HC-75150, N01-HC-45133, grant number U01 HL080295 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, with additional contribution from the National Institute on Aging R01-AG-023629, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and R01 AG-15928, R01 AG-20098, and AG-027058 from the National Institute on Aging, R01 HL-075366 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, University of Pittsburgh Pepper Center P30-AG-02482]. A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.chs-nhlbi.org/pi.htm. Dr. Whitson is supported by the American Federation for Aging Research, the Duke Pepper Center P30-AG-028716 and K23-AG-032867. Dr. Thielke received support from the John A. Hartford Foundation. Dr. Chaudhry is supported by K23-AG-030986.

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | HEW | ST | PD | AO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | PC | NZ | AA | SC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | DI | ABN | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | ||||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | ||||||

| Honoraria | X | X | ||||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | ||||||

| Consultant | X | X | ||||||

| Stocks | X | X | ||||||

| Royalties | X | X | ||||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | ||||||

| Board Member | X | X | ||||||

| Patents | X | X | ||||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | ||||||

Footnotes

Meeting: This work has not been presented at national meetings.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ensrud KE, Ewing SK, Taylor BC, et al. Comparison of 2 frailty indexes for prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and death in older women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:382–389. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothman MD, Leo-Summers L, Gill TM. Prognostic significance of potential frailty criteria. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2211–2116. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leveille SG, Fried LP, McMullen W, Guralnik JM. Advancing the taxonomy of disability in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:86–93. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.1.m86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, et al. Depressive symptoms and physical decline in community-dwelling older persons. Jama. 1998;279:1720–1726. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardy SE, Studenski SA. Fatigue predicts mortality in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1910–1914. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardy SE, Studenski SA. Fatigue and function over 3 years among older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:1389–1392. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.12.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitson HE, Sanders LL, Pieper CF, et al. Correlation between symptoms and function in older adults with comorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:676–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Studenski S, et al. Designing randomized, controlled trials aimed at preventing or delaying functional decline and disability in frail, older persons: a consensus report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:255–263. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyd CM, Xue QL, Simpson CF, Guralnik JM, Fried LP. Frailty, hospitalization, and progression of disability in a cohort of disabled older women. Am J Med. 2005;118:1225–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ottenbacher KJ, Graham JE, Al Snih S, et al. Mexican Americans and frailty: findings from the Hispanic established populations epidemiologic studies of the elderly. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:673–679. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandeen-Roche K, Xue QL, Ferrucci L, et al. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women's health and aging studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:262–266. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue QL, Bandeen-Roche K, Varadhan R, Zhou J, Fried LP. Initial manifestations of frailty criteria and the development of frailty phenotype in the Women's Health and Aging Study II. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:984–990. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.9.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu DS, Lee DT, Man NW. Fatigue among older people: a review of the research literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 47:216–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tell GS, Fried LP, Hermanson B, et al. Recruitment of adults 65 years and older as participants in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1993;3:358–366. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appels A, Mulder P. Fatigue and heart disease. The association between ‘vital exhaustion’ and past, present and future coronary heart disease. J Psychosom Res. 1989;33:727–738. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(89)90088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portenoy RK, Itri LM. Cancer-related fatigue: guidelines for evaluation and management. Oncologist. 1999;4:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skapinakis P, Lewis G, Mavreas V. Temporal relations between unexplained fatigue and depression: longitudinal data from an international study in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:330–335. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000124757.10167.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glader EL, Stegmayr B, Asplund K. Poststroke fatigue: a 2-year follow-up study of stroke patients in Sweden. Stroke. 2002;33:1327–1333. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000014248.28711.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith NL, Psaty BM, Heckbert SR, Tracy RP, Cornell ES. The reliability of medication inventory methods compared to serum levels of cardiovascular drugs in the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:143–146. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1701–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Van Limbeek J, et al. Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D): results from a community-based sample of older subjects in The Netherlands. Psychol Med. 1997;27:231–235. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796003510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ives DG, Fitzpatrick AL, Bild DE, et al. Surveillance and ascertainment of cardiovascular events. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:278–285. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evashwick C, Rowe G, Diehr P, Branch L. Factors explaining the use of health care services by the elderly. Health Serv Res. 1984;19:357–382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. Jama. 2005;294:716–724. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tinetti ME, Bogardus ST, Jr., Agostini JV. Potential pitfalls of disease-specific guidelines for patients with multiple conditions. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2870–2874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb042458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fried TR, McGraw S, Agostini JV, Tinetti ME. Views of older persons with multiple morbidities on competing outcomes and clinical decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1839–1844. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy TE, Agostini JV, Van Ness PH, et al. Assessing multiple medication use with probabilities of benefits and harms. J Aging Health. 2008;20:694–709. doi: 10.1177/0898264308321006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fried LP, Xue QL, Cappola AR, et al. Nonlinear multisystem physiological dysregulation associated with frailty in older women: implications for etiology and treatment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1049–1057. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tinetti ME, Fried T. The end of the disease era. Am J Med. 2004;116:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nardi R, Scanelli G, Corrao S, et al. Co-morbidity does not reflect complexity in internal medicine patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2007;18:359–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, Allore HG. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. N Engl J Med. 362:1173–1180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman AB, Gottdiener JS, McBurnie MA, et al. Associations of subclinical cardiovascular disease with frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M158–166. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walston J, McBurnie MA, Newman A, et al. Frailty and activation of the inflammation and coagulation systems with and without clinical comorbidities: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2333–2341. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirsch C, Anderson ML, Newman A, et al. The association of race with frailty: the cardiovascular health study. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]