Abstract

Joint models are frequently used in survival analysis to assess the relationship between time-to-event data and time-dependent covariates, which are measured longitudinally but often with errors. Routinely, a linear mixed-effects model is used to describe the longitudinal data process, while the survival times are assumed to follow the proportional hazards model. However, in some practical situations, individual covariate profiles may contain changepoints. In this article, we assume a two-phase polynomial random effects with subject-specific changepoint model for the longitudinal data process and the proportional hazards model for the survival times. Our main interest is in the estimation of the parameter in the hazards model. We incorporate a smooth transition function into the changepoint model for the longitudinal data and develop the corrected score and conditional score estimators, which do not require any assumption regarding the underlying distribution of the random effects or that of the changepoints. The estimators are shown to be asymptotically equivalent and their finite-sample performance is examined via simulations. The methods are applied to AIDS clinical trial data.

Keywords: Changepoint, Conditional score, Corrected score, Measurement error, Random effects, Proportional hazards

1 Introduction

An ordinary objective in many medical studies is to investigate how survival times, which are usually censored are related to some time-independent or time-varying covariates. When the true values of the time-varying covariates are always observed, the Cox [1] proportional hazards model is a powerful tool which is commonly used to describe the relationship. However, instead of observing the true time-dependent covariate process, some measurements are taken longitudinally. These measured values of the covariate are usually error-prone and their replacements for the true covariate values in the proportional hazards model may cause biased estimation [2].

A popular approach for the analysis of survival time and longitudinal data measured with error is to jointly model the time-to-event data and the covariate process. This makes possible the exploitation of the information contained in both data in dealing with the measurement errors. Joint modeling often assumes a proportional hazards model for the survival times and a linear mixed-effects model for the longitudinal data. The literature is rich in methods developed under this framework. These approaches include parametric methods with an assumption about the distribution function of the random effects and that of the measurement errors [3–5], semiparametric methods such as the conditional score approach [6,7], the corrected score method [8] and the time-varying coefficients proportional hazards model [9].

However, in many studies the trajectories of individual longitudinal data may show some nonlinearity, indicating that a linear random effects model may not be suitable for the covariate process [10]. A motivating example arises from the AIDS clinical trial ACTG-175 data in which the CD4 cells counts tend to increase initially and drop down later for some individuals. Nonlinearity sometimes may be captured by a changepoint model. Models of this type are often of interest in the analysis of data from clinical studies. Kiuchi et al. [11] used a piecewise linear model for the T4 counts to analyze data from homosexual men who were mostly HIV-infected. Their goal was to estimate the distribution of the time of the change that occurs in the T4 counts and the parameters were estimated based on empirical and hierarchical Bayes methods. In a joint modeling with change point framework, Faucett et al. [12] assumed a piecewise linear random effects model for the logCD4 and the proportional hazards model for the time to AIDS for the analysis of data from the AIDS clinical trial ACTG-019 with the purpose of comparing zidovudine (zdv) treatment and placebo. The zdv treatment is believed to cause an initial increase in the CD4 count that tends to later decline. In their model, the random effects are normally distributed and the changepoint follows a lognormal distribution. Multiple-imputation techniques were used to estimate the parameters in the model which was aimed to characterize the association between the CD4 counts and the survival time. In another context, Jacqmin-Gadda et al. [13] jointly modeled cognitive decline and risk of dementia assuming a piecewise polynomial mixed-effects model with random changepoints to describe the cognitive decline and a log-normal model for time-to-dementia. The parameters were estimated using a maximum likelihood-based method. These approaches are very restrictive as they require specification of the underlying distribution functions of the random effects and changepoints.

In this paper, we propose a more flexible joint model of survival time and error-prone longitudinal covariate data, with less restrictive estimation techniques. More explicitly, we assume a subject-specific changepoint model for the longitudinal covariate data and the proportional hazards model is considered for the time-to-event data. The proposed nonlinear random effects model is different and more flexible compared with the aforementioned models. A sharp transition changepoint model is assumed to characterize the longitudinal covariate process. However, asymptotic results are not straightforward for such model as pointed out by Seber and Wild [14]. This has led us to incorporate a smooth transition function into the changepoint model. We concentrate on the estimation of the parameter in the proportional hazards regression model and develop two estimators based on approaches, which leave unspecified the distributions of the random effects and changepoints, namely the conditional score and corrected score methods. These estimators are shown to be asymptotically equivalent.

We describe our model formulation in Section 2 and construct in Section 3 the corrected score and conditional score estimators of the parameter in the model for the survival time data. In Section 4, the performance of the estimators is investigated via simulation studies. The approaches are applied to the ACTG-175 data and the results of the analysis are presented in Section 5. Finally, some concluding remarks are given in Section 6.

2 Model formulation

Suppose there are n subjects, which are followed up over the study period [0, L], where 0 < L < ∞. For each subject i, i = 1, …, n, let denote the possibly right-censored survival time and Ci be the censoring time. The observed survival data for subject i are the observed survival time and the failure time indicator , where I(.) is an indicator function. Let Zi(u) denote the true time-dependent covariate process, which is not observable, and Z0i(u) = {Z01i(u), …, Z0K0i(u)}′ be a K0-dimensional vector of covariates consisting of both time-independent and time-dependent covariates, which can be accurately measured at any time u. Some longitudinal measurements of size mi are taken on the covariate Zi at ordered occasions tij with timi ≤ Ti, j = 1, …, mi, i = 1, …, n. The univariate assumption for the covariate Zi(u) is simply for convenience and the general multivariate case can be extended similarly but with more complicated calculations.

2.1 The longitudinal data submodel

In our problem, the true covariate data Zi(tij), i = 1, …, n, j = 1, …, mi, are subject to measurement error. The longitudinal observations of Zi are Wij, j = 1, …, mi, i = 1, …, n, which are assumed to follow the nonlinear random effects model

| (1) |

where D(u, a) ≡ [1, (u − a), …, (u − a)p, (u − a)sign(u − a), …, (u − a)psign(u − a)] for any u and a, αi denotes a (2p+1)-dimensional vector of random coefficients, and τi is the subject-specific changepoint occurring in the time trajectory of the covariate Zi for the ith subject. Here, τi and αi are allowed to be correlated and τi should verify ti2 ≤ τi ≤ timi−1. The function sign(.) is defined such that sign(u) = −1 for u < 0, sign(0) = 0 and sign(u) = 1 otherwise. Hence, the true process of the possibly mismeasured longitudinal covariate is assumed to be Zi(u) = D(u, τi)αi, i = 1, …, n. Note that model (1) can be rewritten as

This submodel assumes a two-phase polynomial random effects model with a sharp but continuous transition at the changepoint for the process of the longitudinal covariate. It provides a flexible parameterization of the covariate process and the simplest case corresponds to that of p = 1, where the submodel reduces to a two-phase piecewise linear model:

The vector of errors ei = (ei1, …, eimi)′ is assumed to follow a zero-mean multivariate normal distribution with covariance matrix σ2Imi, where Imi is the identity matrix of size mi, and σ2 is a nonnegative real number. Let θi denote and ti = (ti1, …, timi)′ be the vector of measurement times for subject i. It is assumed that θi and Z0i are independent, and ei is independent of . Moreover, , i = 1, …, n, are independent and identically distributed random variables and the sets of individual observation times possibly differ among subjects. Let μ and ϒ denote the mean and variance covariance matrix of θ1, respectively. The notations Wi = (Wi1, …, Wimi)′ and η = (σ2, μ′, vec(ϒ))′ are used further.

2.2 The submodel for the survival time data

The survival times are linked to the longitudinal covariates via the proportional hazards model. Assuming a non-informative censoring as well as the independence of survival times to measurement times and errors, the hazards function for subject i is defined as follows:

where and λ0(.) is an unspecified baseline hazards function. The main challenge is that Zi(u) is not observed and has a changepoint. Hence, inference of the parameter estimation will be based on the finite number of longitudinal data Wi, i = 1, …, n.

3 Estimation

Our interest focuses on the characterization of the relationship between the survival time and the longitudinal covariate. Hence, we aim to estimate the parameter β in the survival time submodel. However, the true covariate process is unknown and one may like to naively replace the individual random effects and changepoints with their nonlinear least squares estimators, based on the individual longitudinal data. Note that the regression function f(u, θi) ≡ D(u, τi)αi is not differentiable with respect to τi. This irregularity constitutes a major drawback for model (1) since desirable properties, such as the consistency and normality of the estimators of the random effects and changepoints, may not hold. In addition, the derivation of the variance covariance matrix of the estimator of θi, which is crucial in the estimation of β, may be cumbersome. An alternative would be the use of smoothing techniques. Following Bacon and Watts [15], we replace sign(u) in D(u, τi) with a smooth transition function of the form turn(u/γ), where γ is a positive smoothing parameter. To mimic sign(u), the function turn(u/γ) has to satisfy conditions including the followings:

The parameter γ controls the sharpness of the transition at the changepoint, the smaller value it takes the steeper the change and the more turn(u/γ) and sign(u) agree at a given time point u. Further insight into smooth transition functions can be found in [15]. We consider “smoothing” the changepoint model (1) with the hyperbolic tangent function, tanh(.), and obtain a more general version of model (1) which is given as follows:

| (2) |

where f̃(u, θi) ≡ D̃(u, τi)αi and D̃(u, τi) is defined similarly as D(u, τi), but with sign(u−τi) replaced by tanh{(u−τi)/γi}. The parameter γi denotes the ith subject’s specific smoothing parameter, which may also need to be estimated along with θi. In such case, the estimation would require an increase in the minimum number of observations per individual. For simplicity, it is assumed here that γi is known. Moreover, since the transition at each changepoint is considered abrupt, we further assume the same and small smoothing parameter γ for all individuals. Based on some simulation results, which did not change considerably for values of γ smaller than 0.01, the value of γ is taken to be 0.01. It is worth mentioning that the regression function f̃(.) has the nice property of being continuously differentiable at each component of θi, i = 1, …, n. Next, treating θi as a vector of fixed parameters, we proceed as follows for its estimation at any given time u. Let denote the number of longitudinal observations for subject i by time u. The estimator of θi at time u, such that , is taken to be , which is the minimizer of . Let denote the true value of θi. A first order Taylor series expansion of f̃(u, θi) about yields

| (3) |

where H(u, θ) ≡ (∂/∂θ)f̃(u, θ). Let . Also, let , where is the -dimensional matrix whose jth row is . Based on (3), it can be obtained that is approximately , and can be approximated as . With the assumption of normal error, it is straightforward to see that conditionally on θi, is approximately normally distributed with mean θi and variance . Hence, given θi and for known σ2, Ẑi(u) follows an approximate normal distribution with mean Zi(u) and variance that can be approximated as σ2Ωi(u), where . Let , and Σi(u) ≡ diag[Ωi(u), 0K0×K0], where 0K0 and 0K0×K0 are K0-dimensional zero vector and K0 × K0 zero matrix respectively. Based on X̂i(u), we can formulate the following additive measurement error model:

Let Yi(u) ≡ I(Ti ≥ u, ti2p+2 ≤ u) denote the at-risk process and define the counting process increment dNi(u) ≡ I(Δi = 1, u ≤ Ti ≤ u + du, ti2p+2 ≤ u). For the estimation of β, the “ideal” regression corresponds to the case when the true longitudinal covariate process is known. In this case, the usual Cox partial likelihood score would be defined as

where X denotes the vector , k = 0, 1. The “ideal” estimator of β is the solution to . As the true longitudinal profile is unobserved for each subject i, a simple approach, which is referred to here as the “naive” regression, consists of using X̂i(u) in place of Xi(u) in at any time u. The “naive” estimator for β, denoted by β̂na, solves , where . Note that β̂na is biased for β [2] and the substitution of X̂ for X may lead to erroneous conclusions. In the following, we develop some functional methods based on the corrected and conditional scores approaches.

3.1 Corrected score method

The principle of the corrected score method consists of removing the bias from a biased estimating function by means of some techniques which involve approximating the expectation of the biased estimating function [8,9,16]. The approach is free from a priori assumptions about the distribution of the random effects or that of the changepoints. Nakamura [16]’s method requires all individuals to have an equal number of longitudinal observations. In [8,9] the number of measurements is allowed to vary across subjects, and the time-dependent covariate process is described by a linear random effects model. Here, a changepoint model is considered and starts from a different biased estimating function for the parameter β. We define a biased estimating function for β as follows:

where and , k = 0, 1. Next we try to find a corrected score estimating function from . For fixed u, β, and σ2, let sk(u, β), and s̃k(u, β, σ2) denote E{Sk(u, β, X)}, and E{S̃k(u, β, σ2)}, respectively, k = 0, 1. With the assumption of independence between the errors and the random effects, it can be shown that s̃0(u, β, σ2) = s0(u, β) and s̃1(u, β, σ2) = s1(u, β) + σ2s0(u, β)Σ(u, β), where Σ(u, β) is the limit of as n goes to infinity. Letting ẽ(u, β, σ2) and e(u, β) denote s̃1(u, β, σ2)/s̃0(u, β, σ2), and s1(u, β)/s0(u, β), respectively, it is clear that ẽ(u, β, σ2) = e(u, β) + σ2Σ(u, β). Based on the functional Taylor series expansion of order one of the function (x, y) ↦ x/y, an approximation to E{S̃1(u, β, σ2)/S̃0(u, β, σ2)} yields the following corrected score function:

For known σ2, the corrected score estimator of β, denoted by β̂cr, solves . Let β0 denote the true value of β and define

where . When approximation (3) is accurate, the asymptotic properties of are given in the following.

Property 1

Under conditions (A1)–(A5) in Appendix A, is asymptotically normally distributed with mean zero and variance, which can be estimated by the robust sandwich estimator {ϑ(β̂cr)}−1 κ(β̂cr)[{ϑ(β̂cr)}−1, where and C⊗2 denotes CC′ for any vector C.

We provide a proof of the asymptotic properties of in Appendix A. For notational convenience, let θ̂i denote and Fi be F̃i(timi, θ̂i), i = 1, …, n. When the estimation of the nuisance parameter, η, is of interest an estimating equation for η based on the method of moments and (3) is given by , where Φi(η) = {φi1(η), (φi2(η))′, vec(φi3(η))}′, φi1(η) = {Wi − f̃i(timi, θ̂i)}′ {Wi − f̃i(timi, θ̂i)} − σ2(mi − 2p − 2), φi2(η) = θ̂i − μ and . Denote by η̂ the estimator of η which solves this estimating equation. Also, let Θ = (β′, η′)′, and , where η0 is the true value of the nuisance parameter. The asymptotic variance covariance matrix of can be estimated by the sandwich estimator {ϑ̃(Θ̂)}−1κ̃(Θ̂) [{ϑ̃(Θ̂)}−1]′, where and Ψi(Θ) ≡ {ωi(β, σ2), I(mi > 2p + 2)Φi(η)}′. Note that higher order Taylor series expansion of the function (x, y) ↦ x/y can be considered for the approximation to E{S̃1(u, β, σ2)/S̃0(u, β, σ2)}.

3.2 Conditional score estimation

The conditional score method was first introduced by Stefanski and Carroll [17] in generalized linear models with covariate measurement error. Tsiatis and Davidian [7] developed the method further in joint modeling. Their model was later extended by Song et al. [6] to account for multiple longitudinal covariates data measured with error. Note that in their method, the longitudinal covariate process follows a linear model with random effects. The idea behind the approach is to adjust the bias by conditioning on a sufficient statistic of the nuisance parameter. Similar to its corrected score counterpart, the conditional score method does not need any specification of the distribution of the random effects or that of the changepoints. In our case, Qi(u, β, σ2) = X̂i(u)+ σ2Σi(u)βdNi(u) is a sufficient statistic for Xi(u) and the dependence of the hazards function for subject i on Xi(u) can be removed by conditioning on Qi(u, β, σ2). Proceeding as in [7] the conditional hazards function can be shown to be

where for k = 0, 1, and . Moreover, the conditional score estimating function for β is

where for k = 0, 1. For known σ2, the conditional score estimator, denoted by β̂cs, solves . When (3) holds, an interesting relationship between the conditional and corrected scores estimators is given as follows.

Property 2

Under the regularity conditions (A1)–(A5) in Appendix A, the conditional and corrected scores estimators under the changepoint modeling are asymptotically equivalent.

A sketch of the proof of the asymptotic equivalence between the two estimators can be found in Appendix B.

4 Simulation studies

An extensive simulation study is carried out to investigate the performance of the methods presented in Section 3. A single error-prone time-dependent covariate is considered and its process is assumed to follow the two-phase piecewise linear model Zi(u) = α0i+α1i(u−τi)+ α2i|u − τi|. The observations of Zi are generated according to the model Wij = Zi(tij) + eij, where the error eij is simulated from a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance σ2 = 0.1, 0.2. The measurement are taken at time tij in {0, 4, 8, 10, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, 56, 64, 72, 80} with at least eight measurements per subject. The available longitudinal observations are obtained prior to the observed event times. The survival times are generated according to the hazards function λi(t) = λ0(t) exp {β1Zi(t) + β2Z0i}, where Z0i is a Bernoulli random variable with probability of success p = 0.5; β = (β1, β2)′ is (−ln(2), 0)′ or (−ln(3), 0.5)′. The baseline hazard function is taken to be a constant λ0 = 1. A common censoring time is imposed to all individuals such that the censoring rate is 25%. Two scenarios are considered for the distributions of the random effects and changepoints. In the first situation, αi are generated from a multivariate normal distributions N((μ1, μ2, μ3)′, G), where (μ1, μ2, μ3) = (2, 0.2, −0.5) and G is a diagonal matrix with , which is (1, 0.01, 0.001). The changepoint, τi, is generated from a normal distribution , where μ4 = 12, and . The second scenario deals with the situation where the distributions of αi and τi deviate from normality. αi is drawn from a homoscedastic normal mixture distribution ρN(μm1, G)+(1 − ρ)N(μm2, G), where ρ = 0.5, μm1 = (2, 0.2, −0.5)′, μm2 = (2.5, 0.3, −0.6)′, and G is a diagonal matrix with diag(G) = (1, 0.01, 0.001). The changepoint, τi, is simulated from , where ρ = 0.5, μτ1 = 12, μτ2 = 10 and .

For each scenario, a total of 500 Monte Carlo samples are generated with a sample size n = 200 and 600. The parameter β = (β1, β2)′ is estimated using the methods described in the previous Section. The main results of the simulations are presented in Tables 1 and 2 in which “Bias” denotes the average of the 500 estimates β̂k of βk minus βk, “ASE” stands for the average of 500 estimates of the standard deviations of the estimate β̂k, “SDE” means the square root of the sample variance of 500 estimates of βk, k = 1, 2, and “CP” is the coverage probability for the 95% confidence interval.

Table 1.

Simulation results for normally distributed random effects and change points; Ideal, “ideal” regression; Naive, “naive” regression; CDS, conditional score approach; CRS, corrected score method.

| n | β |

σ2 = 0.10 |

σ2 = 0.20 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal | Naive | CDS | CRS | Ideal | Naive | CDS | CRS | ||||

| 200 | (−ln(2), 0) | β1 | Bias | −0.0054 | 0.0114 | −0.0058 | −0.0072 | −0.0054 | 0.0269 | −0.0065 | −0.0092 |

| ASE | 0.0507 | 0.0497 | 0.0521 | 0.0527 | 0.0507 | 0.0487 | 0.0543 | 0.0557 | |||

| SDE | 0.0524 | 0.0517 | 0.0550 | 0.0554 | 0.0524 | 0.0513 | 0.0580 | 0.0589 | |||

| CP | 0.9460 | 0.9460 | 0.9460 | 0.9460 | 0.9460 | 0.8920 | 0.9460 | 0.9420 | |||

| β2 | Bias | −0.0052 | −0.0036 | −0.0035 | −0.0035 | −0.0052 | −0.0029 | −0.0028 | −0.0028 | ||

| ASE | 0.1665 | 0.1664 | 0.1674 | 0.1677 | 0.1665 | 0.1664 | 0.1677 | 0.1682 | |||

| SDE | 0.1697 | 0.1693 | 0.1728 | 0.1731 | 0.1697 | 0.1696 | 0.1768 | 0.1774 | |||

| CP | 0.9480 | 0.9560 | 0.9600 | 0.9600 | 0.9480 | 0.9520 | 0.9480 | 0.9480 | |||

| (−ln(3), 0.5) | β1 | Bias | −0.0076 | 0.0441 | −0.0100 | −0.0178 | −0.0076 | 0.0890 | −0.0126 | −0.0298 | |

| ASE | 0.0745 | 0.0709 | 0.0887 | 0.0936 | 0.0745 | 0.0679 | 0.0969 | 0.1100 | |||

| SDE | 0.0759 | 0.0743 | 0.0858 | 0.0883 | 0.0759 | 0.0729 | 0.0965 | 0.1034 | |||

| CP | 0.9500 | 0.8600 | 0.9660 | 0.9700 | 0.9500 | 0.6980 | 0.9640 | 0.9720 | |||

| β2 | Bias | −0.0038 | −0.0215 | −0.0003 | 0.0030 | −0.0038 | −0.0379 | 0.0019 | 0.0092 | ||

| ASE | 0.1711 | 0.1707 | 0.1791 | 0.1812 | 0.1711 | 0.1703 | 0.1809 | 0.1862 | |||

| SDE | 0.1739 | 0.1748 | 0.1845 | 0.1860 | 0.1739 | 0.1764 | 0.1961 | 0.1999 | |||

| CP | 0.9420 | 0.9380 | 0.9480 | 0.9500 | 0.9420 | 0.9380 | 0.9440 | 0.9480 | |||

| 600 | (−ln(2), 0) | β1 | Bias 1 | −0.002 | 0.0142 | −0.0029 | −0.0033 | −0.0021 | 0.0298 | −0.0033 | −0.0042 |

| ASE | 0.0287 | 0.0281 | 0.0296 | 0.0298 | 0.0287 | 0.0276 | 0.0309 | 0.0314 | |||

| SDE | 0.0280 | 0.0280 | 0.0297 | 0.0298 | 0.0280 | 0.0277 | 0.0313 | 0.0314 | |||

| CP | 0.9620 | 0.9140 | 0.9560 | 0.9580 | 0.9620 | 0.7820 | 0.9520 | 0.9560 | |||

| β2 | Bias | 0.0003 | 0.0009 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | 0.0003 | 0.0010 | 0.0012 | 0.0012 | ||

| ASE | 0.0949 | 0.0949 | 0.0951 | 0.0951 | 0.0949 | 0.0949 | 0.0952 | 0.0953 | |||

| SDE | 0.0971 | 0.0993 | 0.1012 | 0.1012 | 0.0971 | 0.1006 | 0.1045 | 0.1046 | |||

| CP | 0.9520 | 0.9500 | 0.9460 | 0.9460 | 0.9520 | 0.9480 | 0.9380 | 0.9380 | |||

| (−ln(3), 0.5) | β1 | Bias | −0.0042 | 0.0481 | −0.0062 | −0.0090 | −0.0042 | 0.0940 | −0.0075 | −0.0134 | |

| ASE | 0.0419 | 0.0398 | 0.0513 | 0.0531 | 0.0419 | 0.0381 | 0.0566 | 0.0614 | |||

| SDE | 0.0415 | 0.0408 | 0.0472 | 0.0476 | 0.0415 | 0.0397 | 0.0526 | 0.0538 | |||

| CP | 0.9540 | 0.7560 | 0.9660 | 0.9680 | 0.9540 | 0.3240 | 0.9620 | 0.9740 | |||

| β2 | Bias | 0.0027 | −0.0171 | 0.0044 | 0.0056 | 0.0027 | −0.0347 | 0.0053 | 0.0078 | ||

| ASE | 0.0969 | 0.0967 | 0.1010 | 0.1017 | 0.0969 | 0.0965 | 0.1018 | 0.1033 | |||

| SDE | 0.0972 | 0.1016 | 0.1067 | 0.1069 | 0.0972 | 0.1042 | 0.1149 | 0.1157 | |||

| CP | 0.9600 | 0.9360 | 0.9400 | 0.9400 | 0.9600 | 0.9220 | 0.9300 | 0.9320 | |||

Table 2.

Simulation results when the random effects and changepoints follow bimodal distributions; Ideal, “ideal” regression; Naive, “naive” regression; CDS, conditional score approach; CRS, corrected score method.

| n | β |

σ2 = 0.10 |

σ2 = 0.20 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal | Naive | CDS | CRS | Ideal | Naive | CDS | CRS | ||||

| 200 | (−ln(2), 0) | β1 | Bias | −0.0044 | 0.0110 | −0.0062 | −0.0075 | −0.0044 | 0.0261 | −0.0073 | −0.0100 |

| ASE | 0.0507 | 0.0497 | 0.0524 | 0.0530 | 0.0507 | 0.0488 | 0.0546 | 0.0559 | |||

| SDE | 0.0508 | 0.0502 | 0.0533 | 0.0537 | 0.0508 | 0.0493 | 0.0557 | 0.0565 | |||

| CP | 0.9540 | 0.9280 | 0.9420 | 0.9420 | 0.9540 | 0.8940 | 0.9480 | 0.9440 | |||

| β2 | Bias | 0.0164 | 0.0144 | 0.0147 | 0.0147 | 0.0164 | 0.0136 | 0.0140 | 0.0141 | ||

| ASE | 0.1664 | 0.1663 | 0.1671 | 0.1674 | 0.1664 | 0.1663 | 0.1674 | 0.1680 | |||

| SDE | 0.1651 | 0.1658 | 0.1689 | 0.1692 | 0.1651 | 0.1665 | 0.1729 | 0.1735 | |||

| CP | 0.9460 | 0.9440 | 0.9420 | 0.9420 | 0.9460 | 0.9480 | 0.9360 | 0.9360 | |||

| (−ln(3), 0.5) | β1 | Bias | −0.0076 | 0.0418 | −0.0125 | −0.0204 | −0.0076 | 0.0865 | −0.0159 | −0.0333 | |

| ASE | 0.0745 | 0.0711 | 0.0901 | 0.0950 | 0.0745 | 0.0681 | 0.0983 | 0.1115 | |||

| SDE | 0.0746 | 0.0726 | 0.0834 | 0.0859 | 0.0746 | 0.0702 | 0.0923 | 0.0987 | |||

| CP | 0.9620 | 0.8880 | 0.9640 | 0.9680 | 0.9620 | 0.7120 | 0.9600 | 0.9720 | |||

| β2 | Bias | 0.0203 | −0.0024 | 0.0194 | 0.0228 | 0.0203 | −0.0209 | 0.0198 | 0.0272 | ||

| ASE | 0.1712 | 0.1708 | 0.1793 | 0.1815 | 0.1712 | 0.1704 | 0.1812 | 0.1866 | |||

| SDE | 0.1726 | 0.1736 | 0.1824 | 0.1838 | 0.1726 | 0.1753 | 0.1935 | 0.1972 | |||

| CP | 0.9420 | 0.9480 | 0.9500 | 0.9540 | 0.9420 | 0.9480 | 0.9400 | 0.9520 | |||

| 600 | (−ln(2), 0) | β1 | Bias | −0.0029 | 0.0135 | −0.0036 | −0.0040 | −0.0029 | 0.0291 | −0.0040 | −0.0049 |

| ASE | 0.0287 | 0.0281 | 0.0298 | 0.0300 | 0.0287 | 0.0275 | 0.0311 | 0.0316 | |||

| SDE | 0.0281 | 0.0280 | 0.0298 | 0.0299 | 0.0281 | 0.0277 | 0.0313 | 0.0315 | |||

| CP | 0.9600 | 0.9300 | 0.9460 | 0.9500 | 0.9600 | 0.7920 | 0.9520 | 0.9500 | |||

| β2 | Bias | 0.0019 | 0.0019 | 0.0019 | 0.0019 | 0.0019 | 0.0019 | 0.0019 | 0.0020 | ||

| ASE | 0.0949 | 0.0949 | 0.0950 | 0.0951 | 0.0949 | 0.0949 | 0.0951 | 0.0952 | |||

| SDE | 0.0950 | 0.0963 | 0.0980 | 0.0981 | 0.0950 | 0.0971 | 0.1007 | 0.1008 | |||

| CP | 0.9520 | 0.9520 | 0.9460 | 0.9460 | 0.9520 | 0.9420 | 0.9360 | 0.9360 | |||

| (−ln(3), 0.5) | β1 | Bias | −0.0052 | 0.0469 | −0.0075 | −0.0103 | −0.0052 | 0.0928 | −0.0090 | −0.0150 | |

| ASE | 0.0418 | 0.0398 | 0.0516 | 0.0535 | 0.0418 | 0.0380 | 0.0569 | 0.0617 | |||

| SDE | 0.0401 | 0.0400 | 0.0464 | 0.0469 | 0.0401 | 0.0390 | 0.0522 | 0.0535 | |||

| CP | 0.9660 | 0.7340 | 0.9700 | 0.9740 | 0.9660 | 0.3080 | 0.9720 | 0.9740 | |||

| β2 | Bias | 0.0022 | −0.0183 | 0.0031 | 0.0042 | 0.0022 | −0.0362 | 0.0036 | 0.0061 | ||

| ASE | 0.0969 | 0.0967 | 0.1010 | 0.1016 | 0.0969 | 0.0965 | 0.1017 | 0.1032 | |||

| SDE | 0.0971 | 0.0999 | 0.1048 | 0.1051 | 0.0971 | 0.1016 | 0.1120 | 0.1127 | |||

| CP | 0.9540 | 0.9460 | 0.9540 | 0.9540 | 0.9540 | 0.9260 | 0.9260 | 0.9340 | |||

Table 1 shows the results of the simulation from scenario 1. It can be observed from this table that for β1 the “ideal” estimator, which is not applicable in real problems, outperforms all the other estimators with regard to the bias. Its coverage probability is also close to the nominal 95% level. The bias correction methods hold a clear advantage over the “naive” estimator in terms of bias and coverage probability. They display smaller biases and larger coverage probabilities, close to the nominal level. However, the standard deviations of the “naive” estimator are smaller than the corrected and conditional scores counterparts. Hence, the bias reduction by both functional methods leads to a variance inflation. Also, the standard deviations and biases of both corrected score and conditional score estimators increase with |β1| and σ2. The same phenomenon was reported in different settings by [8], Song and Wang [9] and Kong and Gu [18]. In addition, it can be noted that the conditional score estimator shows smaller bias and standard deviation compared with the corrected score estimator when n = 200. Therefore, the conditional score approach has better performance than the corrected score method under small sample size situations. But, the advantage diminishes when n = 600 as the two estimators are asymptotically equivalent. It can also be seen that the biases and standard deviations of all the estimators, except those for the “naive” estimator, are generally decreasing functions of the sample size, n.

The results of the simulation from the second scenario are presented in Table 2. They are similar to those reported in Table 1, suggesting that the performance of the conditional score and corrected score approaches are neither related to the distribution function of the changepoints nor to that of the random effects. Furthermore, it can be observed from Tables 1 and 2 that the estimation of β2 is also affected by large σ2 and |β2| although, the effect is less pronounced than that on β1. In addition to estimating the parameter of interest, we have also estimated the nuisance parameter under the first scenario. The results of the estimation are given in Table 3, where it can be noted that the measurement error clearly affects the estimation of the nuisance parameter. The standard deviations of the estimates of the components of η are increasing functions of the variance of the measurement error and decreasing functions of the sample size, n. Additionally, the effect of the smoothing parameter on the results from the estimation of the parameter of interest has been investigated via simulations, under the same settings as those of the first scenario with γ = 0.5, 0.1, 0.01 and 0.001. The results of these simulations are presented in Table 4 and can be seen to be almost the same across the two γ values, 0.01 and 0.001.

Table 3.

Simulation results regarding the estimation of the nuisance parameter under the first scenario.

| n | Parameter |

σ2 = 0.10 |

σ2 = 0.20 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias | ASE | SDE | CP | Bias | ASE | SDE | CP | |||

| 200 | σ2 | −0.0002 | 0.0049 | 0.0047 | 0.9600 | −0.0010 | 0.0099 | 0.0094 | 0.9580 | |

| μ1 | −0.0045 | 0.0725 | 0.0708 | 0.9580 | −0.0089 | 0.0746 | 0.0734 | 0.9600 | ||

| μ2 | −0.0004 | 0.0072 | 0.0070 | 0.9560 | 0.0000 | 0.0074 | 0.0071 | 0.9560 | ||

| μ3 | −0.0004 | 0.0027 | 0.0028 | 0.9340 | −0.0008 | 0.0032 | 0.0032 | 0.9280 | ||

| μ4 | 0.0050 | 0.0779 | 0.0803 | 0.9280 | 0.0079 | 0.0856 | 0.0877 | 0.9260 | ||

|

|

−0.0066 | 0.1044 | 0.1077 | 0.9260 | −0.0055 | 0.1107 | 0.1134 | 0.9280 | ||

|

|

−0.0002 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | 0.9220 | −0.0002 | 0.0011 | 0.0011 | 0.9220 | ||

|

|

0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.9340 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.9260 | ||

|

|

0.0093 | 0.1235 | 0.1309 | 0.9340 | 0.0509 | 0.1572 | 0.1719 | 0.9320 | ||

| 600 | σ2 | −0.0001 | 0.0029 | 0.0029 | 0.9620 | −0.0007 | 0.0057 | 0.0058 | 0.9440 | |

| μ1 | −0.0052 | 0.0421 | 0.0401 | 0.9700 | −0.0098 | 0.0433 | 0.0415 | 0.9660 | ||

| μ2 | −0.0011 | 0.0041 | 0.0042 | 0.9380 | −0.0007 | 0.0043 | 0.0043 | 0.9340 | ||

| μ3 | −0.0002 | 0.0016 | 0.0016 | 0.9480 | −0.0006 | 0.0018 | 0.0018 | 0.9400 | ||

| μ4 | 0.0077 | 0.0450 | 0.0428 | 0.9620 | 0.0108 | 0.0494 | 0.0474 | 0.9440 | ||

|

|

0.0018 | 0.0615 | 0.0620 | 0.9500 | 0.0032 | 0.0652 | 0.0660 | 0.9440 | ||

|

|

−0.0002 | 0.0006 | 0.0006 | 0.9240 | −0.0002 | 0.0006 | 0.0006 | 0.9340 | ||

|

|

0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.9600 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.9640 | ||

|

|

0.0052 | 0.0719 | 0.0691 | 0.9520 | 0.0428 | 0.0916 | 0.0890 | 0.9520 | ||

Table 4.

Simulation results for various values of γ under the settings of the first scenario when the random effects and changepoints are normally distributed; β = (−log(3), 0.5)′; σ2 = 0.20; n = 200; Ideal, “ideal” regression; Naive, “naive” regression; CDS, conditional score approach; CRS, corrected score method.

|

γ = 0.5 |

γ = 0.10 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias | ASE | SDE | CP | Bias | ASE | SDE | CP | |||

| Ideal | β1 | −0.0076 | 0.0745 | 0.0759 | 0.9500 | −0.0076 | 0.0745 | 0.0759 | 0.9500 | |

| β2 | −0.0038 | 0.1711 | 0.1739 | 0.9420 | −0.0038 | 0.1711 | 0.1739 | 0.9420 | ||

| Naive | β1 | 0.0893 | 0.0678 | 0.0729 | 0.6980 | 0.0891 | 0.0679 | 0.0729 | 0.7020 | |

| β2 | −0.0380 | 0.1703 | 0.1763 | 0.9380 | −0.0379 | 0.1703 | 0.1764 | 0.9380 | ||

| CDS | β1 | −0.0121 | 0.0968 | 0.0964 | 0.9620 | −0.0126 | 0.0969 | 0.0965 | 0.9620 | |

| β2 | 0.0017 | 0.1809 | 0.1959 | 0.9480 | 0.0018 | 0.1809 | 0.1961 | 0.9440 | ||

| CRS | β1 | −0.0291 | 0.1098 | 0.1032 | 0.9740 | −0.0297 | 0.1099 | 0.1034 | 0.9720 | |

| β2 | 0.0090 | 0.1861 | 0.1997 | 0.9480 | 0.0092 | 0.1862 | 0.1999 | 0.9480 | ||

| Nuisance parameter | ||||||||||

| σ2 | −0.0009 | 0.0099 | 0.0094 | 0.9580 | −0.0010 | 0.0099 | 0.0094 | 0.9560 | ||

| μ1 | −0.0254 | 0.0747 | 0.0735 | 0.9480 | −0.0090 | 0.0747 | 0.0734 | 0.9600 | ||

| μ2 | −0.0016 | 0.0073 | 0.0071 | 0.9520 | 0.0000 | 0.0074 | 0.0071 | 0.9560 | ||

| μ3 | 0.0012 | 0.0032 | 0.0032 | 0.9260 | −0.0008 | 0.0032 | 0.0032 | 0.9280 | ||

| μ4 | 0.0316 | 0.0841 | 0.0869 | 0.9200 | 0.0079 | 0.0856 | 0.0877 | 0.9260 | ||

|

|

−0.0034 | 0.1109 | 0.1137 | 0.9300 | −0.0054 | 0.1107 | 0.1134 | 0.9280 | ||

|

|

−0.0002 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | 0.9320 | −0.0002 | 0.0011 | 0.0011 | 0.9260 | ||

|

|

0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.9300 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.9240 | ||

|

|

0.0261 | 0.1553 | 0.1707 | 0.9260 | 0.0511 | 0.1571 | 0.1719 | 0.9300 | ||

|

γ = 0.01 |

γ = 0.001 |

|||||||||

| Bias | ASE | SDE | CP | Bias | ASE | SDE | CP | |||

| Ideal | β1 | −0.0076 | 0.0745 | 0.0759 | 0.9500 | −0.0076 | 0.0745 | 0.0759 | 0.9500 | |

| β2 | −0.0038 | 0.1711 | 0.1739 | 0.9420 | −0.0038 | 0.1711 | 0.1739 | 0.9420 | ||

| Naive | β1 | 0.0891 | 0.0679 | 0.0729 | 0.7020 | 0.0890 | 0.0679 | 0.0729 | 0.6980 | |

| β2 | −0.0380 | 0.1703 | 0.1763 | 0.9380 | −0.0379 | 0.1703 | 0.1764 | 0.9380 | ||

| CDS | β1 | −0.0124 | 0.0969 | 0.0965 | 0.9640 | −0.0126 | 0.0969 | 0.0965 | 0.9640 | |

| β2 | 0.0017 | 0.1809 | 0.1959 | 0.9440 | 0.0019 | 0.1809 | 0.1962 | 0.9440 | ||

| CRS | β1 | −0.0294 | 0.1098 | 0.1034 | 0.9720 | −0.0298 | 0.1100 | 0.1034 | 0.9720 | |

| β2 | 0.0090 | 0.1861 | 0.1997 | 0.9480 | 0.0092 | 0.1862 | 0.1999 | 0.9480 | ||

| Nuisance parameter | ||||||||||

| σ2 | −0.0012 | 0.0099 | 0.0094 | 0.9560 | −0.0010 | 0.0099 | 0.0094 | 0.9580 | ||

| μ1 | −0.0114 | 0.0747 | 0.0734 | 0.9580 | −0.0089 | 0.0746 | 0.0734 | 0.9600 | ||

| μ2 | −0.0002 | 0.0074 | 0.0071 | 0.9560 | 0.0000 | 0.0074 | 0.0071 | 0.9560 | ||

| μ3 | −0.0005 | 0.0032 | 0.0032 | 0.9360 | −0.0008 | 0.0032 | 0.0032 | 0.9280 | ||

| μt | 0.0104 | 0.0854 | 0.0878 | 0.9260 | 0.0079 | 0.0856 | 0.0878 | 0.9260 | ||

|

|

−0.0048 | 0.1108 | 0.1134 | 0.9300 | −0.0055 | 0.1107 | 0.1134 | 0.9260 | ||

|

|

−0.0002 | 0.0011 | 0.0011 | 0.9280 | −0.0002 | 0.0011 | 0.0011 | 0.9220 | ||

|

|

0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.9280 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.9260 | ||

|

|

0.0533 | 0.1577 | 0.1720 | 0.9380 | 0.0510 | 0.1572 | 0.1720 | 0.9320 | ||

5 ACTG 175 data analysis

5.1 Data

The AIDS Clinical Trial Group Study 175 (ACTG-175) is a double-blind randomized trial comparing the efficacy of four different antiretroviral treatments: zidovudine (zdv) monotherapy, the combination of didanosine with zidovudine (zdv/ddl), zidovudine plus zalcitabine (zdv/ddc) and didanosine (ddl) alone. The study involved 2467 HIV-infected patients who were enrolled in the clinical trial units between December 1991 and October 1992 and followed longitudinally for almost three years (until November 1994). For each patient, some baseline characteristics (e.g. gender, race, age) were recorded along with the censoring time or the time to the event of interest, which is death or diagnosis with AIDS disease. The time-dependent covariate was the CD4 cell count, which was measured intermittently and approximately at 0, 8, 20, 32, …, 168 weeks after randomization. The number of longitudinal observations at each individual level ranges from 1 to 19 with 13 as median. Note that the data on the CD4 count were collected for a secondary objective which was the investigation of a possible link between this covariate and the time to AIDS disease development or death. More details on the clinical trial can be found in [19]. The time is rescaled with origin at the time of randomization because the subjects entered the study at different times. In the following analysis, we include individuals with more than 5 longitudinal observations, resulting in a subset of n = 2027 subjects and a total of NT = 24333 CD4 count measurements. Individual observations obtained after diagnosis of AIDS disease were not included. In the considered subset, 255 individuals were diagnosed with AIDS or died in the study period. The censoring was due to administrative censoring in most cases.

5.2 Analysis models

The primary interest in the ACTG-175 study was to compare the four treatments, and the zidovudine momotherapy was found to be the least efficient treatment. Here, we focus on the secondary objective, which is the characterization of the relationship between the CD4 count covariate and the time to AIDS disease progression or death. In the analysis, we use the logarithmic transformation to stabilize the variance and normalize the within-subject measurement error for the CD4 counts.

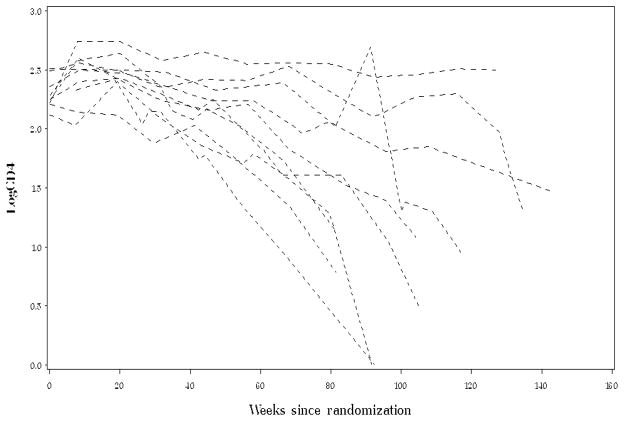

Figure 1 displays the log10-transformed CD4 count trajectories for ten subjects from the analyzed data set. It can be observed that the log10CD4 initially increases and later drops down for some individuals, showing evidence of changepoints for those individuals. We then consider using the following changepoint model for individual log10 CD4 profile:

| (4) |

where eij, the measurement error at time tij, is assumed to follow a zero-mean normal distribution with variance σ2, i = 1, …, n, j = 1, …, mi. Note that measurements on CD4 counts are usually error-prone and subject to individual biological variation. Moreover, observe that model (4) is a two-phase piecewise linear model with an abrupt transition at the subject-specific changepoint. For subject i, the slopes before and after the changepoint, τi, are αi2 − αi3 and αi2 + αi3, respectively, i = 1, …, n. In the analysis, model (4) is approximated by the hyperbolic tangent model, which consists of replacing |tij − τi| in (4) with (tij − τi) tanh{(tij − τi)/γ} similarly as in (2). The value of the smoothing parameter is chosen as γ = 0.01 and the choice of an appropriate value of γ is discussed later. The simple linear and quadratic models are routinely used to model the log-transformed CD4 count in many applications. We compare the two-phase piecewise linear model with these models based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC), which is defined as N ln(RSS/N)+2(q+1), and the root mean square error (RMSE), which is . Here RSS is short for the sum of squared residuals of the model, q denotes the number of parameters and N is the number of observations in the model. The AIC for the two-phase piecewise linear model is found to be −106706.3, while those for the simple linear and quadratic models are −99863.1 and −104073.5, respectively. Moreover, the two-phase piecewise linear model has the smallest RMSE (0.09796) compared with the simple linear and quadratic models, whose RSME’s are 0.11913 and 0.10596, respectively. Clearly, both criteria favor the two-phase piecewise linear model, which we adopt afterward to describe the process of log10 CD4. Figure 2 depicts the fitted profiles using the two-phase piecewise linear model, the simple linear and quadratic models, along with the observed log10 CD4 profiles of the ten individuals in Figure 1. It is seen that the simple linear or quadratic model does not fit as well as the changepoint model among several individuals.

Figure 1.

log10 CD4 profiles of ten individuals from the analyzed data set.

Figure 2.

Observed log10 CD4 for the ten individuals in Figure 1 with the fitted profiles using the two-phase piecewise linear, simple linear and quadratic models.

We characterize the relationship between the time to AIDS disease development or death and the covariates through the proportional hazard function

where Z1(t) represents the process of log10CD4, Z2 is the gender variable, taking 1 for female and 0 for male, Z3 = (Z31, Z32, Z33)′ and Z4 = (Z41, Z42, Z43)′ are vectors of dummy variables for treatment (zdv, zdv/ddl, zdv/ddc, ddl) and race (non-hispanic white, non-hispanic black, hispanic, other), respectively. The reference category for treatment is zdv and that for race is non-hispanic white. The parameter is estimated using the “naive” regression, the corrected and conditional scores methods. Furthermore, the p-values for the significance of the parameters are based on Wald statistics.

5.3 Results

The main results of the analysis are presented Table 5. It appears that the estimates of β1 by all methods are significant (p-values are smaller than 0.001) at the significance level of 5%, indicating an association between log10CD4 and the time to AIDS disease progression or death. The negative sign of the estimates of β1 implies that the hazards function is a decreasing function of the CD4 counts. The “naive” regression leads to a smaller absolute value of the estimates of β1 as well as smaller standard errors compared with the corrected or conditional score counterparts. For β2 and the components of β3, none of the estimates is significant (p-values are greater than 0.4), suggesting that gender and treatment are not associated with the time to AIDS progression or death when log10CD4 and race variables are included in the proportional hazards model. Regarding β4, the “naive” estimation of β41 yields a non-significant estimate (p-value is 0.0741), while the results ( p-values are smaller than 0.01) of the conditional and corrected scores estimations signal an association between race and time to AIDS or death. Non-hispanic black patients have higher hazards in comparison with non-hispanic white patients according to both bias-correction estimations. Meanwhile, there is no evidence of significant difference in the hazards between patients in the non-hispanic white, hispanic and other groups.

Table 5.

Results of the analysis of the ACTG-175 data; Naive, “naive” regression; CDS, conditional score method; CRS, corrected score method; Est, estimate; SE, standard error.

| β | Naive |

CDS |

CRS |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | p-value | Est | SE | p-value | Est | SE | p-value | |

| β1 | −0.9500 | 0.0412 | < 0.0001 | −1.3559 | 0.1354 | < 0.0001 | −1.4410 | 0.1723 | < 0.0001 |

| β2 | −0.1038 | 0.2003 | 0.6041 | −0.1383 | 0.2202 | 0.5301 | −0.1495 | 0.2101 | 0.4766 |

| β31 | −0.1314 | 0.1828 | 0.4722 | −0.0947 | 0.2262 | 0.6755 | −0.0823 | 0.1904 | 0.6655 |

| β32 | 0.0198 | 0.1794 | 0.9122 | 0.0884 | 0.2121 | 0.6767 | 0.1128 | 0.1987 | 0.5704 |

| β33 | −0.1406 | 0.1742 | 0.4194 | 0.0386 | 0.2480 | 0.8764 | 0.0523 | 0.1955 | 0.7891 |

| β41 | 0.3855 | 0.2159 | 0.0741 | 0.5583 | 0.2324 | 0.0163 | 0.5454 | 0.2313 | 0.0184 |

| β42 | 0.2126 | 0.2902 | 0.4636 | 0.2961 | 0.3022 | 0.3271 | 0.2744 | 0.3040 | 0.3668 |

| β43 | −1.4172 | 1.0267 | 0.1675 | −0.8480 | 1.0367 | 0.4134 | −0.8362 | 1.0286 | 0.4162 |

| η | Nuisance parameter |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | p-value | ||

| σ2 | 0.0096 | 0.0004 | < 0.0001 | |

| μ1 | 2.4886 | 0.0063 | 0.0002 | |

| μ2 | −0.0017 | 0.0005 | < 0.0001 | |

| μ3 | −0.0029 | 0.0004 | < 0.0001 | |

| μ4 | 62.1790 | 0.7461 | < 0.0001 | |

|

|

0.0759 | 0.0068 | < 0.0001 | |

| σ12 | 0.0011 | 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |

| σ13 | −0.0003 | 0.0001 | 0.0553 | |

| σ14 | −1.2269 | 0.2093 | < 0.0001 | |

|

|

0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.1926 | |

| σ23 | −0.0003 | 0.0003 | 0.3087 | |

| σ24 | −0.0905 | 0.0257 | 0.0004 | |

|

|

0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.2018 | |

| σ34 | 0.0350 | 0.0256 | 0.1711 | |

|

|

1127.0142 | 27.1854 | < 0.0001 | |

Note: represents the vector of the parameters of interest which characterizes the relationship between the time to AIDS or death and the covariates; β1, β2, β3 and β4 are the coefficients of log10 CD4 count, gender and the vectors of dummy variables for treatment and race, respectively; η is the nuisance parameter, whose components are the variance of the error, the mean of the random effects and the non-redundant elements of the covariance matrix of the random effects.

Table 5 also shows the results of the estimation of the nuisance parameter, denoted by η = (σ2, μ′, vech(ϒ))′, where μ = (μ1, μ2, μ3, μ4)′ and ϒ are the mean and variance covariance matrix of the vector θi = (αi1, αi2, αi3, τi)′, respectively. Here, vech(ϒ) denotes . The results of the estimation show a significant (p-value is smaller than 0.0001) estimate of σ2, pointing out evidence that measurement error is present in the log10CD4. Moreover, the estimates of all the components of μ are significant (p-value is smaller than 0.0001), indicating a change in the mean slope of log10CD4 over time. The estimate of the mean slope in the first phase (μ2 − μ3) is positive (0.0012), suggesting a somewhat initial rise in the mean log10CD4 probably due to the treatments. Meanwhile, the mean slope in the second phase (μ2 + μ3) has a negative estimate (−0.0046), which suggests a decline in the mean log10CD4 following the initial increase. The estimated mean changepoint is 62.179 weeks. Moreover, the estimate of σ44, which is the standard deviation of the changepoints, is significant (p-value is smaller than 0.0001) and large (33.571 weeks), indicating a large amount of heterogeneity in the individual changepoints. This is understandable since observation times vary widely across individuals.

5.4 Choice of the smoothing parameter

To estimate the parameter of interest in the analysis, it is necessary to specify the value of the smoothing parameter γ, which governs the sharpness of the hyperbolic tangent model. This model becomes sharper as γ approaches zero [14,15]. Hence, it is advisable to choose a small value of γ in order for the hyperbolic tangent model to be almost identical to the original model (4), which is an abrupt changepoint model. To select γ, an approach is to consider a decreasing sequence (γk)k≥0 of positive real numbers, such that γk converges to zero as k goes to infinity. Then, for a given k, one has to carry out the estimation of the parameter of interest, β, using γk as the value of γ. Letting β̂k denote the estimate of β using γk, a plausible value of γ is chosen as γk* such that k* = min{k: ||β̂k+1 − β̂k|| < ε, k ≥ 0}, where ||C|| = max{|C1|, …, |Cq|} for any vector C = (C1, …, Cq)′, and ε is a small tolerance. In the analysis, we set ε at 10−2 and consider γk = γ0a−k for any k, where γ0 = 1 and a = 10. The value of k* is found to be 2 and therefore, γ is chosen as 0.01. We note that the results do not vary considerably for values of γ smaller than 0.01. In Table 6, we report the results of the analysis using several values of the smoothing parameter. It can be observed from this table that the discrepancy between the results for γ = 0.01 and γ = 0.001 is small.

Table 6.

Results of the ACTG-175 data analysis for various values of the smoothing parameter; Naive, “naive” regression; CDS, conditional score method; CRS, corrected score method; Param, parameter; Est, estimate; SE, standard error.

| Param |

γ = 1 |

γ = 0.1 |

γ = 0.01 |

γ = 0.001 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | Est | SE | Est | SE | Est | SE | ||

| Naive | |||||||||

| β1 | −0.9913 | 0.0437 | −0.9508 | 0.0412 | −0.9500 | 0.0412 | −0.9500 | 0.0412 | |

| β2 | −0.1016 | 0.2002 | −0.1038 | 0.2003 | −0.1038 | 0.2003 | −0.1038 | 0.2003 | |

| β31 | −0.1308 | 0.1825 | −0.1313 | 0.1827 | −0.1314 | 0.1828 | −0.1314 | 0.1828 | |

| β32 | 0.0092 | 0.1795 | 0.0199 | 0.1794 | 0.0198 | 0.1794 | 0.0198 | 0.1794 | |

| β33 | −0.1237 | 0.1742 | −0.1410 | 0.1742 | −0.1406 | 0.1742 | −0.1406 | 0.1742 | |

| β41 | 0.3958 | 0.2159 | 0.3855 | 0.2159 | 0.3855 | 0.2159 | 0.3855 | 0.2159 | |

| β42 | 0.2197 | 0.2903 | 0.2128 | 0.2902 | 0.2126 | 0.2902 | 0.2126 | 0.2902 | |

| β43 | −1.0850 | 1.0213 | −1.3893 | 1.0260 | −1.4172 | 1.0267 | −1.4171 | 1.0267 | |

| CDS | |||||||||

| β1 | −1.5121 | 0.1662 | −1.3524 | 0.1372 | −1.3559 | 0.1354 | −1.3574 | 0.1386 | |

| β2 | −0.1554 | 0.2218 | −0.1377 | 0.2205 | −0.1383 | 0.2202 | −0.1395 | 0.2202 | |

| β31 | −0.1174 | 0.2495 | −0.0937 | 0.2265 | −0.0947 | 0.2262 | −0.0970 | 0.2270 | |

| β32 | 0.0831 | 0.2446 | 0.0891 | 0.2122 | 0.0884 | 0.2121 | 0.0859 | 0.2128 | |

| β33 | 0.0163 | 0.2750 | 0.0395 | 0.2483 | 0.0386 | 0.2480 | 0.0362 | 0.2490 | |

| β41 | 0.6353 | 0.2369 | 0.5566 | 0.2325 | 0.5583 | 0.2324 | 0.5594 | 0.2326 | |

| β42 | 0.3305 | 0.3159 | 0.2953 | 0.3020 | 0.2961 | 0.3022 | 0.2955 | 0.3023 | |

| β43 | −0.7134 | 1.0363 | −0.8707 | 1.0352 | −0.8480 | 1.0367 | −0.8475 | 1.0371 | |

| CRS | |||||||||

| β1 | −1.5992 | 0.1959 | −1.4378 | 0.1732 | −1.4410 | 0.1723 | −1.4431 | 0.1713 | |

| β2 | −0.1690 | 0.2141 | −0.1489 | 0.2101 | −0.1495 | 0.2101 | −0.1511 | 0.2101 | |

| β31 | −0.1122 | 0.2084 | −0.0812 | 0.1903 | −0.0823 | 0.1904 | −0.0854 | 0.1899 | |

| β32 | 0.1034 | 0.2379 | 0.1133 | 0.1983 | 0.1128 | 0.1987 | 0.1096 | 0.1977 | |

| β33 | 0.0239 | 0.2306 | 0.0533 | 0.1951 | 0.0523 | 0.1955 | 0.0491 | 0.1950 | |

| β41 | 0.6323 | 0.2399 | 0.5436 | 0.2313 | 0.5454 | 0.2313 | 0.5470 | 0.2316 | |

| β42 | 0.3112 | 0.3238 | 0.2737 | 0.3038 | 0.2744 | 0.3040 | 0.2735 | 0.3043 | |

| β43 | −0.6885 | 1.0351 | −0.8588 | 1.0279 | −0.8362 | 1.0286 | −0.8353 | 1.0286 | |

| Nuisance parameter | |||||||||

| μ1 | 2.4887 | 0.0063 | 2.4886 | 0.0063 | 2.4886 | 0.0063 | 2.4886 | 0.0063 | |

| μ2 | −0.0017 | 0.0004 | −0.0017 | 0.0004 | −0.0017 | 0.0005 | −0.0017 | 0.0005 | |

| μ3 | −0.0029 | 0.0004 | −0.0029 | 0.0004 | −0.0029 | 0.0004 | −0.0029 | 0.0004 | |

| μ4 | 62.1867 | 0.7458 | 62.1779 | 0.7462 | 62.1790 | 0.7462 | 62.1789 | 0.7461 | |

| σ2 | 0.0096 | 0.0004 | 0.0096 | 0.0004 | 0.0096 | 0.0004 | 0.0096 | 0.0004 | |

|

|

0.0756 | 0.0068 | 0.0759 | 0.0068 | 0.0759 | 0.0068 | 0.0758 | 0.0068 | |

| σ12 | 0.0011 | 0.0001 | 0.0011 | 0.0001 | 0.0011 | 0.0001 | 0.0011 | 0.0001 | |

| σ13 | −0.0003 | 0.0001 | −0.0003 | 0.0001 | −0.0003 | 0.0001 | −0.0003 | 0.0001 | |

| σ14 | −1.2277 | 0.2092 | −1.2278 | 0.2093 | −1.2269 | 0.2093 | −1.2270 | 0.2093 | |

|

|

0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | |

| σ23 | −0.0003 | 0.0003 | −0.0003 | 0.0003 | −0.0003 | 0.0003 | −0.0003 | 0.0003 | |

| σ24 | −0.0891 | 0.0260 | −0.0905 | 0.0255 | −0.0905 | 0.0256 | −0.0904 | 0.0257 | |

|

|

0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | |

| σ34 | 0.0343 | 0.0259 | 0.0349 | 0.0254 | 0.0350 | 0.0256 | 0.0349 | 0.0256 | |

|

|

1124.4563 | 27.1443 | 1127.3108 | 27.1906 | 1127.0142 | 27.1845 | 1126.8695 | 27.1854 | |

6 Conclusion

The paper presents a new joint model of survival time and longitudinal covariate data. A subject-specific changepoint model is proposed for the longitudinal covariate process and the time-to-event data are modeled through the Cox proportional hazards model. Under the changepoint model framework, two estimators based on the corrected score and the conditional score methods are developed for the regression parameter in the proportional hazards model. These estimators perform well and are shown to be asymptotically equivalent. However, the conditional score estimator has a better finite sample size performance.

Spline is commonly used to model nonlinear longitudinal profile [20–23], and it has been used in joint modeling of survival times and longitudinal data [24]. Our approach for longitudinal measurements is different from nonparametric smoothing spline, which generally assumes smoothness and requires a large sample size for longitudinal measurements. On the other hand, our approach may be somewhat similar to regression spline. Nevertheless, the change point model that we propose in the paper does not require continuous derivatives, which are generally assumed in say cubic splines. Hence, our change point model is less restrictive in terms of dealing with abrupt changes.

The proposed estimators are not sensitive to the choice of the transition function for the two-phase piecewise linear model as long as the function satisfies the conditions given in Section 3. However, their performance is affected by large variance of the measurement error, or by large |β1|. Nonetheless, these estimators are more reliable than the “naive” estimator in any situation. An important feature of the proposed methods is their ability to account for the nonlinearity in the longitudinal covariate trajectories without any assumption regarding the distribution function of the random effects or that of the change points.

There may be applications where the proportional hazards model does not hold, and under this situation, a change point in the survival function may be considered. We are currently investigating the piecewise proportional hazards model for time-to-event data. Another interesting situation to explore is the consideration of a more than two-phase change point model, which may be relevant for the longitudinal covariates in some applications. This will obviously give rise to more computational complexity.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Health grants CA 53996, R01ES17030 (C.Y. Wang) and the National Science Foundation grant 97-2118-M-035-002-MY2 (S.M. Lee).

Appendix A: Proof of the asymptotic properties of the corrected score estimator

Regularity conditions

(A1) Pr {Yi(L) = 1} > 0 for any t ∈[0, L], i = 1, …, n.

(A2) Zi(u) is bounded almost surely.

(A3) mi and tij are random variables i = 1, …, n; j = 1, …, mi.

(A4) Σi(u) is bounded and continuously differentiable function of u, i = 1, …, n.

(A5) is positive definite, where s2(u, β) is the limit of as n goes to infinity.

Consistency

For simplicity we assume that σ2 is known. Note that the corrected score estimating function can be expressed as follows:

where is a local-square martingale, and Ẽ(u, β, σ2) denotes S̃1(u, β, σ2)/S̃0(u, β, σ2). Define the process . Under assumptions (A1)–(A4), and by Anderson and Gill [25], S̃0(u, β, σ2), S̃1(u, β, σ2), S0(u, β, X), S1(u, β, X) and Σ̂(u, β) converge in probability to s̃0(u, β, σ2), s̃1(u, β, σ2), s0(u, β), s1(u, β) and Σ(u, β), respectively, and uniformly in u and β. It can be noted that s̃0(u, β, σ2) = s0(u, β) and s̃1(u, β, σ2) = s1(u, β) + σ2Σ(u, β)s0(u, β). Therefore, it is not difficult to see that Ẽ (u, β, σ2) has limit e(u, β) + σ2Σ(u, β), where e(u, β) = s1(u, β)/s0(u, β).

| (5) |

| (6) |

Note that (5) converges to zero in probability since it is a local-square integrable martingale with variance that converges to zero. Furthermore, using similar arguments as in [8], it can be shown that supu,β ||e(u, β) + σ2Σ̂ (u, β) − Ẽ (u, β, σ2)|| = op(1). As a result, (6) is op(1) and so is A2.

where , which is a sum of independent and identically distributed random variables with mean zero. Hence, A4 converges in probability to zero and A3 = U (β) + op(1), where . As a result, converges in probability to U(β) uniformly in β. Hence, U(β̂cr) converges to 0 in probability. Since U(.) is concave and β0 is the unique solution to U (β) = 0, the consistency of β̂cr follows readily from the inverse function theorem [26]. In the following, we prove that asymptotically follows a normal distribution.

Asymptotic distribution

By the mean value theorem, , where and β* is in the line segment joining β̂cr and β0. With similar arguments as in the proof of the convergence in probability of to U(β) uniformly in β, we can also show that converges in probability to

uniformly in β, under conditions (A1)–(A5). With the consistency of β̂cr and the continuity of Γ(.) at β0, the convergence in probability of to Γ(β0) is straightforward. In the following, we show that is asymptotically normally distributed. We first express as a mapping of empirical processes.

where Ki(u, β0, σ2) ≡ X̂i(u) + σ2 Σi(u)β0 and for all c. It appears that is a function of five empirical processes and for any (F, G, P0, P1, N) in D5[0, L] the function is defined as follows:

With conditions (A1)–(A4), the limit of each process exists and by the extended strong law of large number stated in [20], it follows that each process converges almost surely to its limit uniformly in u ∈ [0, L]. Now, let E {K(u, β0, σ2)N(u)}, , E{S̃1(u, β0, σ2)}, E{S̃0(u, β0, σ2)}, E {N(u)} denote the limit of Ê{K(u, β0, σ2)N(u)}, , Ê{S̃1(u, β0, σ2)}, Ê {S̃0(u, β0, σ2)}, Ê {N(u)} respectively. Furthermore, for each u, let Fn(u), Gn(u), Pn0(u), Pn1(u), Nn(u) be defined as follows:

Under conditions (A1)–(A4), the multivariate central limit theorem leads to the convergence in probability of to a zero-mean Gaussian process. Moreover, under the bounded variability condition the limiting distribution of is tight and therefore converges weakly to a zero-mean Gaussian process with a continuous path. Also, the mapping ϕ is Hadamard differentiable and

Then, a functional Taylor series expansion of is the following:

where K(u) and Ki(u) denote K(u, β0, σ2) and Ki(u, β0, σ2), respectively, for notational convenience. After rearranging the above expression we obtain the following:

where

Hence, is a normalized sum of independent and identically distributed random variables, and it follows from the central limit theorem that it is asymptotically normally distributed. We then conclude that has an asymptotic normal distribution with mean zero and variance {Γ(β0)}−1 var {Ψ1(β0, σ2)} {Γ(β0)}−1]′. Note that var {Ψ1(β0, σ 2)} can be consistently estimated by , where

Appendix B: Proof of the asymptotic equivalence between the corrected score and conditional score estimators

In the following, we assume for simplicity that σ2 is known and use similar arguments as in [27]. Note that

where , and . Using similar arguments as in the proof that converges in probability to U(β), and uniformly in β, it can be shown that, under conditions (A1)–(A5), both and converge in probability to Γ(β) uniformly in β. Therefore,

Moreover, the argument of the functional delta method can be applied once again to show that , where Ψ̃i(β0, σ2) is given by

dN(u) is the limit of , and vk(u, β0, σ2) = E{Vk(u, β0, σ2)}. Using the Lebesgue measure, it can be obtained that Vki(u, β0, σ2) = S̃ki(u, β0, σ2), i = 1, …, n, k = 0, 1, almost surely, for fixed u. It follows that vk(u, β0, σ2) = s̃k(u, β0, σ2) almost surely, for fixed u. Furthermore, we can derive , where

It is straightforward to obtain that , and as a result, . The asymptotic equivalence between the two functional estimators is then proven.

References

- 1.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prentice R. Covariate measurement errors and parameter estimates in failure time regression. Biometrika. 1982;69:331–342. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diggle PJ, Sousa I, Chetwynd AG. Joint modelling of repeated measurements and time-to-event outcomes: The fourth Armitage lecture. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27:2981–2998. doi: 10.1002/sim.3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang CY. Corrected score estimator for joint modeling of longitudinal and failure time data. Statistica Sinica. 2006;16:235–253. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wulfsohn M, Tsiatis AA. A joint model for survival and longitudinal data measured with error. Biometrics. 1997;53:330–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song X, Davidian M, Tsiatis AA. An estimator for the proportional hazards model with multiple longitudinal covariates measured with error. Biostatistics. 2002;3:511–528. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/3.4.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsiatis AA, Davidian M. A semiparametric estimator for the proportional hazards model with longitudinal covariates measured with error. Biometrika. 2001;88:447–458. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/3.4.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang CY, Wang N, Wang S. Regression analysis when covariates are regression parameters of a random effect model for observed longitudinal measurements. Biometrics. 2000;56:487–495. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song X, Wang CY. Semiparametric approaches for joint modeling of survival time and longitudinal data with time-varying coefficients. Biometrics. 2008;64:557–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu L, Liu W, Hu XJ. Joint inference on HIV viral dynamics and immune suppression in presence of measurement errors. Biometrics. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1541–0420.2009.01308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiuchi AS, Hartigan JA, Holford TR, Rubinstein P, Stevens CE. Change points in the series of T4 counts prior to AIDS. Biometrics. 1995;51:236–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faucett CL, Schenker N, Taylor JM. Survival analysis using auxiliary variables via multiple imputations with application to AIDS clinical trial data. Biometrics. 2002;58:37–47. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2002.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacqmin-Gadda H, Commenges D, Dartigues JF. Random change point model for joint modeling of cognitive decline and dementia. Biometrics. 2006;62:254–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00443.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seber GAF, Wild CJ. Nonlinear regression. Wiley; New York: 2003. pp. 433–489. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bacon DW, Watts DG. Estimating the transition between two intersecting straight lines. Biometrika. 1971;58:525–534. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura T. Proportional hazards model with covariates subject to measurement error. Biometrics. 1992;48:829–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stefanski LA, Carroll RJ. Conditional scores and optimal scores in generalized linear measurement error models. Biometrika. 1987;74:703–716. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong F, Gu M. Consistent estimation in Cox proportional hazards model with covariate measurement errors. Statistica Sinica. 1999;9:953–969. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammer SM, Katzenstein DA, Huges MD, Gundacker H, Schooley RT, Haubrich MR, Henry WK, Lederman MM, Phair JP, Niu M, Hirch MS, Merigan TC. A trial comparing nucleoside monotherapy with combination therapy in HIV-infected adults with CD4 cell counts from 200 to 500 per cubic millimeter. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335:1081–1090. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610103351501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Taylor JMG. Inference for smooth curves in longitudinal data with application to AIDS clinical trial. Statistics in Medicine. 1995;14:1205–1218. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson S, Jones H. Smoothing splines for longitudinal data. Statistics in Medicine. 1995;14:1235–1248. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rice J, Wu C. Nonparametric mixed effects models for unequally sampled noisy curves. Biometrics. 2001;57:253–259. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durbán M, Harezlak J, Wand MP, Carroll RJ. Simple fitting of subject-specific curves for longitudinal data. Statistics in Medicine. 2005;24:1153–1167. doi: 10.1002/sim.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding J, Wang JL. Modeling longitudinal data with nonparametric multiplicative random effects jointly with survival data. Biometrics. 2008;64:546–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson PK, Gill RD. Cox’s regression model for counting process: a large sample study. Annals of Statistics. 1982;10:1100–1120. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudin W. Principle of mathematical analysis. McGraw-Hill; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song X, Huang Y. On corrected score approach for proportional hazards model with covariate measurement error. Biometrics. 2005;61:702–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]