Abstract

Young men who have sex with men (YMSM) face myriad challenges when deciding to disclose their sexual orientation to family members. Key to this decision is consideration of how disclosure may influence the support they receive from family. This paper explores a diverse sample of YMSM’s (N = 43) perspectives on disclosure of their same-sex attractions to key family members and its impact on family support. Several stages/categories of disclosure are described and some YMSM seemed to continue to move between categories. Additionally, relationships after disclosure included negotiations between the expression of their sexual orientation and the maintenance of family support.

Keywords: adolescents, youth, coming out/disclosure, family, gay, bisexual

The lives and experiences of Lesbian, Bisexual, Gay, Transgender, Intersexual, Queer and Questioning (LBGTIQQ) youth have become the focus of increased research in recent years. Ever more present in this scholarship is the examination of the coming out process for these youth and their families. Much of the research is focused on disclosure of same-sex attraction as a crucial milestone and key component of identity formation (Savin-Williams, 2000). Data also highlight that revealing a same-sex orientation, especially to parents, is a stressful process (Savin-Williams & Dubé, 1998). For many young people, the fear and anxiety around disclosure leads to the decision to hide or conceal their sexual orientation from their families. Fear of negative parental reactions to disclosure of a same-sex sexual orientation has been found to be among the major reasons sexual minority youth do not tell their families (D'Augelli & Hershberger, 1993). Several researchers have contributed to the broadened body of knowledge around the additional factors that influence an individual’s decision to disclose, such as age, gender (Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000), ethnic identity (Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2004), family relations (Waldner & Magruder, 1999) and levels of trust (Miller & Boon, 2000).

In the discussion of how, when, and to whom one chooses to disclose one’s sexual identity or orientation, developmental or stage models have been used for decades to understand non-heterosexual identity formation (Savin-Williams, 2000). Many of these models present a linear process by which an individual goes from a hidden same-sex attraction to questioning and comparing heterosexual versus homosexual identities, to sexual experimentation (homosexual and heterosexual), to self identification as homosexual, to disclosure, and finally, to an integrated or healthy homosexual identity (Cass, 1979). Building on these models, researchers of sexual identity development suggest that individuals move through and revisit stages of development as they explore their sexual orientation within the context of different environments (D'Augelli, 1994; Fassinger & Miller, 1996; McCarn & Fassinger, 1996). Similarly, Harry (1993) contended that stage theories are inadequate in describing the reality of the developmental process and that possibly the most normal situation is one in which, after disclosing a same-sex sexual orientation, an individual remains partly in and out of the closet and adapts one’s set of disclosures to audiences as those audiences change. This indicates that even after disclosure, where many theorists have asserted the sexual identity formation process is complete, stages of disclosure remain and an individual may revert to an earlier stage of more selective disclosure.

Some of the researchers in this field have asserted that a number of the most widely cited models do not adequately address the complexities and variations of the development of a non-heterosexual identity (Diamond, 2005; Eliason, 1996; Mosher, 2001). Rather, their research indicates that the process of sexual identity development is not necessarily linear, nor is a homosexual identity inevitable (Savin-Williams, 2000). Additionally, researchers and counselors alike have begun to assert that identity formation is a continual and interactive process (Horowitz and Newcomb, 2001). Likewise, research continues to indicate that there is a need to further investigate the complexities of the coming out process for sexual minority youth and their families (Ben-Ari, 1995; Hillier, 2002; Savin-Williams & Dubé, 1998).

In addition to family support, other factors are involved in deciding whether or not to disclose one’s sexual orientation. In a study with gay, lesbian and bisexual (GLB) adolescents in a school environment, Lasser and Tharinger (2003) uncovered a strategy of “visibility management,” a careful process of deciding when, to whom, and how a young person decides to disclose or reveal their sexual orientation. In an effort to sustain certain available forms of support, many youth prefer to remain discrete and selective when sharing their same-sex attractions and experiences with close friends and family members (Elizur & Ziv, 2001; Savin-Williams, 2000).

One particular complexity for youth with a same-sex orientation is maintaining familial support after disclosing to family members. Numerous studies have found that because of their sexual orientation, these youth are often not afforded the same familial support as their heterosexual peers (Gonsiorek, 1988; Hetrick & Martin, 1987; Savin-Williams, 1990; Telljohann & Price, 1993). Some families do not react well to the disclosure (Telljohann & Price, 1993) of a non-heterosexual identity and negative reactions from family may range from extreme hostility and rejection, abuse or violence (Hunter & Mallon, 1999) to tolerance rather than active support of the individual (Diaz, 1998). Additionally, it is well documented that even those parents and other family members who try to be supportive will go through their own process of “coming out” when a child or sibling discloses a non-heterosexual identity (Wells-Lurie, 1996). The process of acceptance can take time, and service providers who work with families are encouraged to provide accurate information about sexual orientation and refer families to appropriate counselors and support groups (Ryan & Futterman, 1998).

For adolescents in general, late adolescence and early adulthood is developmentally a period during which young people experiment with behaviors that often bring increased risk (e.g., drug use and sexually risky behaviors). It is a time when young people begin to explore new roles and relationships; establish more intimate attachments and sexual relationships with both male and female peers; and begin to define their sexual identity, both privately and publicly (Arnett, 2000). Likewise, for all young people regardless of their sexual orientation or identity, family support is associated with several healthy developmental outcomes through promoting psychological and emotional health and serving as a protective factor against drug use and high-risk sexual behaviors (Flaherty & Richman, 1986; Kipke et al., in press; Kobak & Sceery, 1988; Sarason, Pierce, Bannerman, & Sarason, 1993). However, unlike their heterosexual peers, LBGTIQQ youth, facing heterosexism from various sources, often cannot turn to their families for support because their families may espouse homophobic and heterosexist beliefs and as a result, youth find themselves feeling disconnected or isolated from their families (D'Augelli & Hershberger, 1993; Gonsiorek, 1988; Hetrick & Martin, 1987; Hunter & Mallon, 1999; Savin-Williams, 1989; Savin-Williams, 1990; Telljohann & Price, 1993; Uribe, 1992).

This current study seeks to gain a more in-depth understanding of one layer of the complex process of coming out to family members--how young men perceive that their disclosure influences their relationships and support from key family members. In particular, we were interested in examining the interplay between disclosure and perceived levels of family support. Based on qualitative interviews from 43 ethnically diverse young men who have sex with men (YMSM), this paper describes the myriad ways they decide how, what and to whom to disclose their sexual identity and how relationships are negotiated after disclosure in order to access and maintain family support.

Method

Setting and Recruitment

Data presented in this paper were collected in 2004 during the formative phase of the Healthy Young Men’s study (HYM), a longitudinal study examining risk and protective factors for substance use and sexual risk among an ethnically diverse sample of YMSM. Study participants represented four primary racial/ethnic identities: African American, Asian Pacific Islander (API) of Filipino descent, Latino of Mexican descent, and White. To identify and recruit eligible participants, the research team approached young men who appeared to be in the appropriate age range for the study and of one of the targeted ethnic populations from social venues (e.g. bars/clubs), youth programs and from ads placed on the Internet.

Screening to determine eligibility was conducted among the young men who appeared to meet requirements for the study: males between the ages of 18 and 22, self-identifying as one of the study’s target ethnic groups and identifying as either gay or bisexual or, if identifying as heterosexual, reporting having had sex with another man. This process yielded a pool of 74 potential study participants and of those 54 (73%) consented to participate in the study.

Of those who consented, 40 completed the series of two semi-structured qualitative interviews, and 3 completed only one of the interviews. The sample consisted of 11 African American, 10 API of Filipino descent, 10 Latino of Mexican descent, and 12 White YMSM. Interviews were conducted in project offices in a large Western US city as well as at cafes and restaurants that were more convenient for the participant, and where privacy could be maintained. Each respondent received a $35 cash incentive per interview.

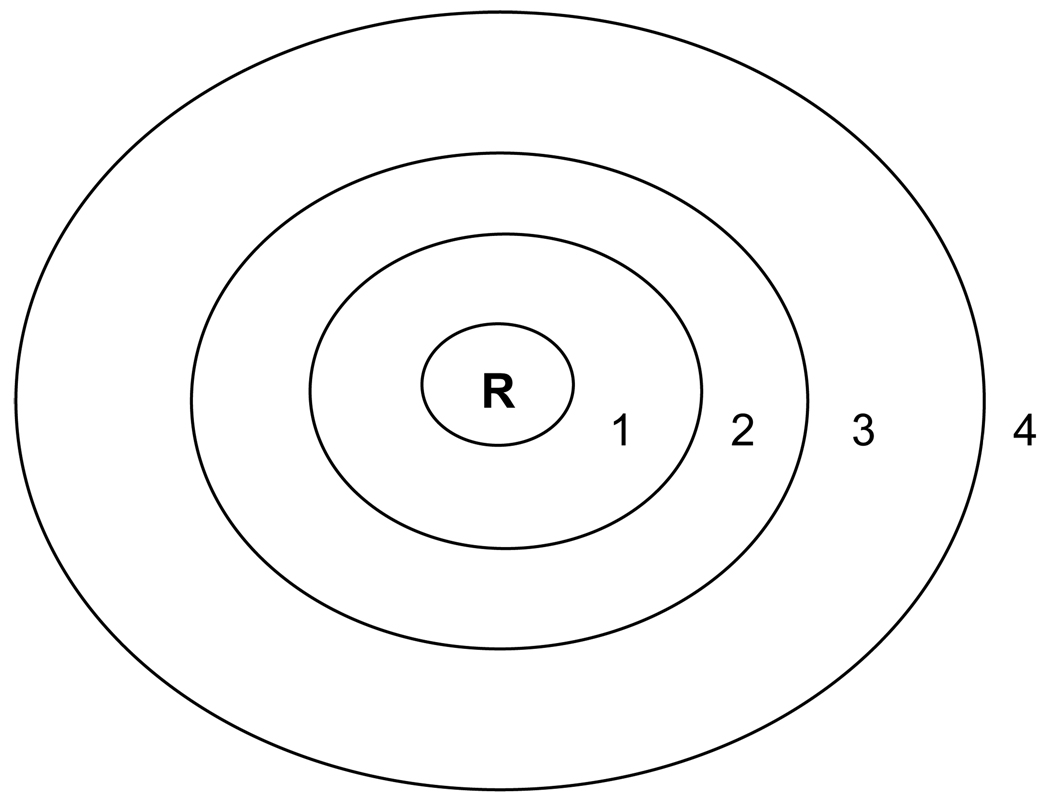

Qualitative interviews

The interview discussion guides used in this phase of the HYM Study were designed as exploratory tools to gather a breadth of information on a variety of key constructs including: family structure, social support, connectedness with communities, racism/discrimination/homophobia, risk prevention strategies, cultural norms and partner relationship dynamics. Specific to this current study, respondents were asked several sets of questions related to sexual identity, family structure and family support. For example, respondents were asked to define their families in their own words--allowing them to include both biological and non-biological people whom they identified as members of their families. Respondents were also asked to graphically depict how close they felt to each self-identified member by placing the individual on a diagram (Figure 1). This diagram was divided into tiers of 1 to 4, representing, in descending order, different levels of emotional closeness to the respondent. Those included in the first tier were considered to form the core of the respondent’s family structure and therefore those from whom the respondent desired or depended on the most for support. In addition, respondents were asked to describe how family members and others (e.g., friends, mentors, service providers) demonstrated support and what forms of support respondents would like to see from their family members. Finally, respondents were asked how they defined their sexual identity and whether or not and to what extent they had disclosed this identity to family members or others in their support networks. Actual names were not included in transcripts, and only pseudonyms appear in this article.

Figure 1.

Family Structure Circle used in the Qualitative Interviews

Analysis of qualitative interviews

The qualitative analysis for this study was based on grounded theory, which entails the simultaneous process of data collection, analysis and theory construction (Glaser, 1992; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). As the data were collected, they were immediately analyzed for patterns and themes, with the primary objective of discovering theory that is implicit in the data. QSR-N6, software developed for qualitative data analysis, was used to analyze the data, in this case, the relationship between disclosure of sexual orientation and maintenance of family support.

All qualitative interviews were audio-recorded, professionally transcribed and cleaned to ensure accuracy. Members of the research team reviewed an initial sample of interviews to identify key themes, which formed the basis of project codebooks. Initially codes focusing on a range of topics were identified and defined based on the key constructs included in the discussion guides. The codebook was modified as needed during the initial stages of coding. Inter-coder reliability was assessed through double coding a sample of approximately 10% of the interviews. Differences in coding were discussed and resolved by the team.

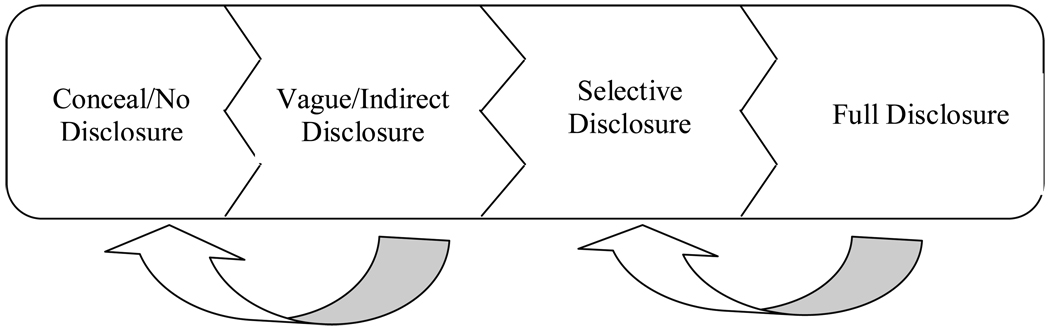

After the initial coding phase, the open coding process began which allowed for constructs of interest to be identified and labeled. For this current study, codes related to family structure, support, sexual identification and the extent to which an individual respondent had disclosed his sexual orientation were included. This open coding process included refining the codes based on the descriptions of experiences by respondents. This process concluded with the development of categories to identify respondents’ level of disclosure regarding sexual orientation in relation to individual family structure: Conceal; Vague/Indirect; Selective; and Full Disclosure. Central to this paper is the examination of the relationship and interactions between family structure, perceived social support and disclosure of sexual orientation or attractions among this ethnically diverse sample of YMSM.

With each of the four disclosure categories developed, we began to look for patterns within each ethnic cohort. The majority of the respondents, regardless of ethnic identity, were placed in the Full Disclosure category. There was relatively even distribution in the Selective disclosure category, with White in the majority, and in the Conceal and Vague disclosure categories, the majority were African American or Filipino. While this is an interesting finding and ethnic and cultural identity may play an integral role in determining when and to whom a young man may disclose his sexual orientation, an almost equal proportion of both of these ethnic identity groups were also included in the Full Disclosure category.

Results

Families and Family Structure

The first phase of analysis focused on identifying how respondents defined their families and what kinds of support or assistance respondents believed a family was supposed to provide. These analyses assisted in understanding how respondents created and maintained their family structures. In general, respondents described a family as a supportive group of people, those who provide love and support, and persons who will always be there:

I define family by the people who basically allow me into their hearts and love me unconditionally according to the things that I haven’t done yet. People that have really looked out for me, who allow me to be there for them and helped me through some really hard times in my life, a lot of transition in growing up. These are the people that have really showed me I can be a lot more than what I thought.

While respondents were mostly in agreement concerning what a family should provide with regard to support, the actual composition of families varied a great deal. Family structure was determined for respondents through the family circle exercise. In this exercise, respondents were asked to define their family in their own terms, and to include those whom he considered to be family based on his definition of the term. In general, their responses yielded two primary categories of family structure: those that included only individuals fitting the definition of a biological family and those that were created from the integration of friends or others such as service providers or surrogate families along with biological family members. A few participants (n = 3) listed only non-biological individuals as family members. Regardless of who was included in the circles, respondents tended to agree that to be included in the circle meant that a certain level of support was expected.

For those describing a family as primarily biological, the rationale appeared to be that the biological bond between family members meant that those individuals would be with you forever:

Blood and bonding. That’s about it….These are the people that you’ve spent your life with and you have a blood bond to them. They will forever be your family. A part of you. And they have altered you and so be it negative or positive, like they’ve had a huge effect on your life.

For respondents who described their families as a mixture of biological and non-biological relationships, the message seemed to be that family was comprised of those who have a deep connection with the respondent and have demonstrated that they understand and love him unconditionally, regardless of genetics or biological bonds:

Well, the immediate family is obvious. And then my cousins are still my family. And then my really close friends, I probably treat them better than my immediate family right now, and, like, they influence me SO much more because they relate to me, they understand me. And so the things that I do, it’s really based on a lot of things that they tell me to do.

Decision Making Surrounding Disclosure

The majority of the young men in this study self-identified as gay or homosexual (n = 30) with several (n = 8) identifying as bisexual and the remainder rejecting labels to describe their sexual identity or behavior. Regardless of which identity they endorsed, these young men had much to say about their willingness and/or ability to disclose their sexual orientation to family members. They described a careful decision-making process that was largely based on how they perceived disclosure would impact needed support from family members such as financial (e.g., college tuition, housing) and emotional (e.g., acceptance, love, encouragement, support). From these narratives, an evolving process of disclosure strategies were identified that reflect the ideas these young men described around disclosing or concealing their sexualities from their families.

Narratives were analyzed within the context of their level of disclosure and the individual family structures to explore their decision-making process as it specifically related to their experiences with and perceptions of family support. Respondents were placed in a particular category based on whether or not they had chosen to disclose their sexual identity and to whom they had disclosed to on their family circle. The categories identified in this study were: Conceal/No Disclosure; Vague/Indirect Disclosure; Selective Disclosure; and Full Disclosure. While these categories were developed to describe some of the processes of disclosing sexual identity, several amalgamations of disclosure occurred within the categories.

Several young men did not easily fit into a category due to individual circumstances. However, the majority of respondents (n = 24) were categorized as having fully disclosed their sexual identity to their family members. The model of disclosure categories presented here was informed by the fluidity of disclosure represented within this sample. For example, some individuals straddled two different categories depending on situations or interactions with particular individuals, similar to the model described by Harry (1993). Figure 2 illustrates our process of disclosure and how young men may move from one category to another with regard to what information or parts of their lives they decided to share with family members. In the figure, the arrows illustrate the fluidity of the categories and how YMSM in our sample often chose to move in between categories (with regard to what information they shared) in order to maintain familial support.

Figure 2.

HYM Study Respondents’ Process of Sexual Orientation Disclosure as Described in the Qualitative Interviews

The following sections present descriptions of the young men who fit into each of these categories, describing their concerns and anxieties about disclosing this part of their identity to their closest family members. In addition, a case study of one participant’s process of disclosing his sexual orientation to his parents is included at the end of this section to illustrate the negotiations that sexual minority youth encounter in deciding when and how to disclose their sexual identity as well as the ongoing negotiations that continue after the initial disclosure.

Conceal/No Disclosure

Young men who did not disclose their sexual orientation (n = 8) described concerted efforts to conceal from their family members any behaviors or language that may reveal a same-sex attraction. These individuals often cited fears of losing support, being rejected, or not wanting to make family members feel uncomfortable or offended. Oftentimes the fear and anxiety was based on perceptions of their family members’ views on homosexuality.

Several young men discussed the various ways they dealt with the struggle of maintaining key family relationships and still remaining true to themselves. For some, the anxiety and anticipation they felt about the consequences of disclosure resulted in the decision to hide their same-sex attraction:

I’d rather pretend, go on pretending. I’d only be lying about one thing. Everything else would be the truth. I’d just be lying about my sexual preference…. I mean it sucks to lie, but at the same time, I’m not willing to lose people in my life just because of my sexual preference. That’s the dumbest thing ever. I’d rather tell them a little white lie or just avoid it.

Well I know for sure my mom would, like, be devastated. That's the only reason why I wouldn't tell them because I know things right now are going really well…But then again I would really want them to know, but then knowing their beliefs and how they are, I don't think they would be very, accepting of that. And I don't know if I can take their rejection right now.

Some young men described very close relationships with family members where they were able to discuss most topics openly, except their sexuality. At times, as in the following example, family members went as far as to mention to the respondents that they would not be accepting of them disclosing their sexual identity, thereby further complicating the decision to disclose:

I can talk to [my mother] about private stuff. It’s, like, if I wouldn’t have my mom it would be hard for me. And that’s why my mom has always been close. And the same way with my grandmother, like, I can go to her for anything, and talk to her and tell her anything. That’s how close, like, we are…I don’t tell her the gay stuff because she’s not ready for all of that…my mom told me once, like, she was, like, if you were to tell me that you were gay I wouldn’t be able to accept it.

Some of these young men also expressed disappointment and anxiety about how concealing their identity had an impact on their relationship with their family. One young man who chose not to discuss his boyfriend with his family felt that this act resulted in a loss of connection within the relationship:

And the challenge of concealing it from my family, that's been not so much a challenge, but one can speculate that it has cost me my family, cost me my family even, my relationship with them because I want to keep this away from them but this is such a huge part of me that I've decided to keep my whole self away from them. Maybe that's what happened.

Interestingly, while respondents were encouraged to include individuals in their lives in their family circles as they saw fit, few of the young men in this category chose to include friends in their family circles. While respondents were asked to explain why certain people were included in the family circles and to explain the relationships, they were not asked specifically why certain people were not included in the family circle. One respondent in this category described family as a more permanent fixture in your life, with biological family members not really having the option of coming and going, therefore their presence and perhaps support are more unconditional:

Like friends, I’ve learned over time, they come and go. And these people [in my family circle] will always be there. Family is more permanent to me. Cause friends come and go and these people will always be there… I don’t really need my family for anything, other than, like, love.

Vague or Indirect Disclosure

Within this category were those young men (n = 3) who had begun to suggest or drop hints about their sexual identity through their behavior or language. These young men had not yet explicitly disclosed their sexual identities to their families, but through their vague or indirect disclosure they appeared to be closer to disclosing their identity than those who were fully concealing. These young men talked about wearing certain clothing that was either “feminine” (e.g. tight fitting) or displayed well known gay-identified images (e.g. rainbows and pink triangles), or engaged in typically “feminine” activities (e.g. shopping, watching soap operas, liking dolls). For some, giving hints or insinuating a same-sex sexual identity through these means was a way of testing the waters and sensing how family members may react upon a more direct disclosure:

I haven't really come out to them but I give them hints, I just don't, I want to come out soon, I'm easing my way in to it you know…It feels good because I feel like when I come out I'm not gonna have nothing to worry about, that they will take me and accept me.

For some respondents, hints and insulations were safer modes of communicating a possible same-sex sexual identity. Many of these young men pointed to the possibility of losing support or the maintenance of it as a reason for not fully disclosing to family members. For these young men, the perception that family members would not support or accept a same-sex sexual identity instilled anxiety around disclosure:

But then the second thing, like, I really don't think they would understand. They try to understand because it's - granted, even though I haven't specifically told them, they know. I've brought my boyfriends over. They know. But they don't know, but they know. You know? … I just don't want to deal with the drama of telling them right now because where my mother has threatened all my life, like, take away stuff from me – like, she has. She'll just get mad and do stuff.

Selective Disclosure

Participants identified as Selective Disclosers (n = 7) reported being deliberate in selecting to whom they disclosed their sexual orientation. These young men were selective around who could know about their sexuality based on their perceptions of how family members would react with the news. This is similar to what other researchers have found in that sexual minority youth often disclose to friends or siblings prior to parents or primary caregivers (D'Augelli & Hershberger, 1993). Those who were able to identify family members to whom they felt they could disclose found comfort and support from selective disclosure:

Interviewer: And, why is it that they know everything and your parents know nothing?

Respondent: Because, I have already told [my sisters] about my sexuality, what I like and it is more comfortable to talk to them because they listen to me and know what I like. And, it is just easier to talk to them.

However, this young man, like many others who were selective about who they could disclose to, also felt the stress about having to hide his identity from other family members. For him and other young men, the potential reality of being exposed and losing support from other key family members generated fear and anxiety:

I am not open and it makes me very scared. Because [my parents] still don’t know, my sisters know but not my entire family, the fear is always there. It is what oftentimes brings people down. It is mostly the fear of what your parents are going to say.

Some also offered descriptions of the types of information they could share with specific family members who knew of their sexual identity to minimize rejection or further loss of support. These young men felt they had to hide activities relating to their identity (e.g. socializing with other gay youth and same-sex relationships) or they had to sacrifice closeness and intimacy to family members in order to access support from gay friends. One respondent, Michael, disclosed his sexuality to his brother and while he was away on a trip, his parents began questioning his brother and figured out that the respondent was gay:

I finally told myself that [I’m gay]. And my mom’s just really close-minded and she’s like “No, that’s a person’s choice whether they’re gay or not and you can change that about yourself. You’re just at a stage where you’re experimenting. So don’t disappoint us. You gotta change that about you.” And I just kept telling them, “Okay, I’ll hide it.” And she’s like, “No, you have to change it, change that about yourself. Me and your dad have had a lot of sacrifices for you and this is what you do to us”.…I was crying the whole time cause I didn’t know what to do… I’ve tried to change. I’ve prayed about it. But feelings were there. I couldn’t stop.

Full Disclosure

Twenty-four young men were categorized as having fully disclosed their sexual identity to their family. However, a few young men (n = 3) in the study were forced to disclose their sexual identity because they were “outed,” either by another family member or by accident. They were categorized as Full Disclosure because, while they did not choose to disclose to their family, they were presented with the unique challenge of having to deal with disclosure before they were ready to make that decision. For example, after his forced disclosure to his parents, Michael described his relationship with his parents as changed, and he no longer considered his parents to be among those family members closest to him. As a result, he often sought support from friends who his parents did not approve of due to their sexual identity. Even though he had disclosed to them, his decision to remain selective was driven by the initial reaction of his parents to his same-sex sexuality:

Ever since my parents found out about me, I’ve been kind of keeping them outside of me ‘cause I’ve never really been able to open up to them. They’ve been close-minded and that just proved more when they found out about me being gay. So, like, I pushed them aside but when it doesn’t deal with that personal side of me, I’ve always felt pretty close to my parents…I think the things I lie to them about, I can't think of anything else except for the fact that I'm gay and I want to hang out with my gay friends. … And, I just can’t take [my gay friends] out of my life. So, I have to lie to my parents sometimes.

For some, the reactions of family members to the disclosure were not what the young person had expected and feared. In this example, “Fredrick,” who described being “yanked out” of the closet, explained how his disclosure plans changed after his aunt found a manuscript he was writing and distributed it to the family:

[My aunt] saw the manuscript on my desk. Well she took it…mailed it…and that’s how my mom found out I was gay. I was yanked out….I never came out and said, “Mom, I’m gay.” I didn’t, the way that I planned on it was to tell her when I moved out. So just in case she tried to put me out, she couldn’t because I’d already have my own space…then [my being gay] came up and tore it all to shit.

Although the premature outing changed his plans, his mother was more supportive than he expected and he was not kicked out of his home. In fact, he described that his mother was not hostile at all about his sexual orientation:

She knows that I’m gay and it’s not an issue that comes up….we know it’s there, you know, we kind of overlook it until it needs to be talked about.

The other young men in this category directly disclosed their sexual identity to the family members closest to them as depicted in their family circle. For many of these young men, having fully disclosed to family members was an integral part of their identity and played a powerful role in shaping their sense of self. Others in the Full Disclosure category still felt they had to negotiate what kind and how information was shared with family members in order to maintain family cohesion and support, supporting the idea that negotiating what kinds of information to share to family members does not end at the time of disclosure about one’s sexual identity.

The family cultures these young men described were diverse in their levels of communication and in their reactions to same-sex sexuality. Young men placed in this category came from a variety of backgrounds and ethnicities. Regardless of their family culture and/or reaction to same-sex attraction, most of these respondents described their process of disclosure as wanting to be open about their sexuality and the activities relating to their sexuality in order to be honest and enhance communication with their family members:

Ever since I was 15, I've been a gay activist...I wanted to be validated and I knew wasn't nobody else going to validate me, so I wanted to validate myself. So I did what I had to do to make sure I was going to be validated for what I did. I put myself in a play. I put myself on stage, singing in front of the school. I put myself singing the Star Spangled Banner for the football game…I did it because I wanted you to see my face. I wanted you to know that this was a gay man who was known to be gay, doing it! For hisself. Doing it and let it be known…My mother didn't understand it. But she's accepted it, because she has no choice. She knows how I am. But she still don't understand it.

Some respondents described the need to be open with their family members about their sexuality but at the same time expressed some of the apprehensions they felt about disclosing their sexual identity to their families – particularly in reference to needing and wanting their continued emotional and, sometimes, financial support:

My parents, my family was kind of the people I came out to last. I almost feel ‘cause I was so close to them that I wasn’t sure how they were gonna react ‘cause we never talked about same-sex whatever. So I didn’t want to break the closeness that my family had had, so I was kind of hesitant. But at the same time, since I was raised to be so open and honest about it, you know, I had to.

Young men in this category described a variety of familial reactions and consequences to their disclosure. Some young men illustrated a certain level of comfort about talking openly with their family members about their boyfriends or other aspects of their sexual identity. In return, they also described layers of support from family that were either uninterrupted or enhanced by the disclosure of identity:

My parents have always [known] since I was 16 and had my first boyfriend, they've always met my boyfriends and - like there are no secrets between my family and myself…I don't know, it's just kind of like if I'm dating somebody, then they meet them and we talk about that and who I'm dating and stuff like that. …I feel it's the same as when my younger sister is dating a guy, like the same that they talk about with her.

Young men who described this level of support after disclosing their sexuality appeared to find this support comforting and appreciated their families’ willingness to try to understand this aspect of their lives. For example, the following respondent reported that his parents and grandparents were initially supportive of him when he “came out” to them. He reported that his mother and grandparents began attending meetings for Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG) in an effort to support him and to gain information of his sexual orientation:

My mother had the first gay sex talk with me a year after I came out, and she [did the] Internet thing, she basically looked at porn and found out how men had sex and she came back and she explained to me, this is how gay[s] have sex (laughs) I was like, what? She just explained the ways they could go about having sex and why it is important to have safe sex, how gay men can penetrate each other, how you're not suppose to do certain things, like, and why and this and that.

While some young men felt full support from their families after choosing to disclose to them, others felt that their family placed limitations on what could be discussed in regards to their sexual orientation. Some family members did not initiate (or avoided) discussion around sexual attraction, while others gave explicit directions that same-sex attraction was not to be discussed. This inability to talk with the people considered to be among those closest to the respondent was typically taken as a sign of the family member not supporting nor trying to understand this aspect of his life. The following respondent explained that his sexuality was not something to ever be discussed again among his family after he disclosed to his parents, resulting in him being unable to bring male friends to his home without upsetting the family balance:

I didn't really talk about that situation with anybody, 'cause Filipino families are really they don't talk about anything…Like, they just don't talk about anything. When I came out to my mother two years ago, a year and a half, two years, she just said let's just don't bring it up anymore. Yeah. That's pretty much they just don't talk about anything.

Some young men felt uncomfortable with certain aspects of their lives after disclosing to their family about their sexual orientation. While they were still able to interact and be with their family, the lack of acceptance was apparent to the respondent. This level of discomfort often prevented them from being able to freely express themselves around their family members. Thus, even after making a conscious decision to disclose their sexuality to family members, they were not able to fully disclose particular aspects of their lives with them. For example, this respondent described how some of the family members he felt closest to were not comfortable in seeing him with gay friends:

Some of [my friends], most of them actually don’t interact with, like, my grandmother or my aunt or my family very much because …my family is not really accepting of my being gay, so they all know but they don’t accept it, so it would be such a problem for them. My aunt straight out one time told me, “Don’t bring them over, I don’t want them over”…Don’t bring my gay friends over.

Others desired a closer relationship with family members and were deeply disappointed by their family’s refusal to discuss their sexual orientation or make efforts to identify with the respondent. For these young men, the diminished relationship and support was an undesirable consequence of their disclosure. The following respondent described losing support from a sister, a key relationship for him following his mother’s death. When this respondent refers to wanting his sister to go to “Pride” with him, he is referring to those events that are held as part of a world wide movement and philosophy that asserts that all LGBTIQQ individuals should be proud of their sexual orientation and gender identity:

I wish my sister would get over it, I wish she would come to Pride, I wish she would come to a Pride event and show that she supports, she supports the lifestyle…she knows that I’m gay and she’s slowly accepting it but she’s not very accepting. She wished it wasn’t the lifestyle that I chose but she’s, I’m her brother and she loves me no matter what and I just wish she would come to a Pride event with me because then it would feel like I kind of have my mom with me because I wasn’t able to have her come.

In some cases, disclosure of one’s sexual attractions resulted in rejection from family members, essentially losing all familial support. Types of rejection ranged from insults, to refusal to accept their son’s sexual identity and to ejection from the family’s home. The following example describes Diego, a young man who went to live with his aunt and developed an enhanced relationship with her as a “second mom” after being kicked out of his own house by his father after disclosing his sexual attractions:

I came out to them and he [my father] didn't like it. He didn't accept it. And from that day on, he never spoke to me again. So! I mean it's either I mope around and try to get his attention or I just move on. And I decided just to move on.

The initial reaction from both parents to Diego’s disclosure was negative and he explained that in imagining their reaction - it was an unknown to him. “It kind of sucked cause I really don't know what I was expecting. I mean coming out to your parents, you really don't know what to expect.” He found the support he needed immediately after the disclosure from an aunt - and that immediate acceptance from her indicated to Diego that her support would be unconditional and he placed her among those closest to him on the family circle. As a result of his father’s reaction, his father was not included as a family member in his family circle. He explained that he would like to see support from his father as someone he can depend on:

Respondent: To see my dad as somebody I could talk to, somebody I can hang out with, somebody I could explain every problem that I have. And unfortunately, I can't do that with him. So I really can't depend on him. That's pretty much it…I don't think he has any expectations for me. I don't think he's happy with me.

Interviewer: Do you think he has any hopes for you?

Respondent: Oh none! None. If he did, he would still be in my life. He'd probably give me advice. But he doesn't even do that. He doesn't do anything. He's never there so I'm not gonna be looking out for him. Looking for his help, so if he's not gonna give me any help, that's okay, I mean I could help myself and I still have other people.

Illustrating the Disclosure Process - A Case Study

The process of deciding to disclose one’s sexual orientation and the consequences that sexual minority youth often face as a result are well illustrated by Brian who described the negotiations he often makes in deciding what information to share with close family members. In the initial “coming out” to his parents, he described playing a guessing game with his parents due to his apprehensions about directly disclosing his identity:

I gave them hints, so they said, “Are you attracted to guys?” and I said “Yeah.” And they said, “What, so you think you might be gay?” and of course I knew I was – it wasn’t I think I might be. But I’m like “Yeah,” just trying to answer yes to their questions. I think that’s where I made my first mistake was that I agreed that I might be instead of saying “Yes, I am.” So, in their minds there was a still a possibility that I wasn’t and I was just confused and trying to figure things out.

Brian’s decision to disclose his sexual identity continued to concern him after this initial conversation. Over the next several months his parents tried to get him more involved in church activities to try to get him back “on the right path.” Right before he was getting ready to leave for college, his mother spoke to him about it for the first time:

My mom said, “Don’t ever tell me that you’re gay cause I could not live with myself.” And I’m like, great – that’s a nice situation to put your child in! So now I’m all worried about her. She said that she couldn’t handle the stress or the depression or whatever it was. She’d just break down…so I was like, OK – great. Now what am I gonna do? Cause I was at that point ready to just say, “YES! I am!”

He eventually sent his parents a letter letting them know that he is gay and it was not going to change. While he had completely disclosed to his entire family that he is gay, he realized that they were not entirely accepting of this part of him:

I don’t really know if they really accept me being gay, but they at least tolerate it. It’s not something that they like to talk about and they don’t want anybody else to know - their friends or coworkers.

His parents not wanting to talk about this part of his life forced Brian to continue to hide information from his parents in order to ensure that he did not push them too far with regard to his relationship with them. He described situations where he was able to open up with his mother about his romantic life but was not able to maintain that level of communication with her:

It would be nice if she were a little more willing to talk about it. She just had this mentality that it’s evil …she has an underlying concern that all mothers have so it’s harder to talk to her. She kind of puts up a wall. But then every once in a while, she’ll actually open up and seems interested. And I take full advantage of that opportunity to tell her anything that I can so that while she’s in that kind of mindset and then you can tell she’s getting down and depressed when I start…and I probably said too much already.

Brian’s story is a good example of how the disclosure process unfolds for many LGBTIQQ youth. Within this sample, there was a great deal of variation in familial reactions to disclosure, disclosure methods and information shared with family members. The young men in this study shared an apprehension to disclose their sexuality to family members due to fears of their reactions and the consequences of those reactions. Brian illustrates that for many of the young men in this study, this apprehension continues after disclosing and as a result, youth may feel that they are unable to share integral pieces of their lives with those who they rely on the most for support and assistance.

Discussion

Disclosure of a same-sex orientation or identity to family members is a continued negotiation. By focusing on the fluidity of young men’s disclosure strategies, this study contributes to a shift in focus on research on sexual identity development, which historically has tended to focus on disclosure as a fixed stage of identity development and consolidation (Diamond, 2005). The findings of this study demonstrate the process young men navigate when deciding to disclose a same-sex sexual orientation to their family members. This navigation includes decisions and evaluations of how disclosure may impact the support they receive from individual family members. The process continues after disclosure when young people make decisions about the level of openness they can have about their sexual orientation to those on whom they depend for emotional and other kinds of support. Additionally, these narratives highlight that relationships after disclosure are likely to involve as much, if not more, negotiation between an individual’s ability to express his sexual orientation or identity and maintaining family support after the disclosure is acknowledged.

Implications for Counseling

Counselors and others seeking to provide support for sexual minority young people need to consider the full range of diversity of disclosure strategies and of the LBGTIQQ youth population as a whole. Consistent with what Lasser and Tharinger (2003) found with GLB adolescents in schools, we found that YMSM practice a system of managing the expression of their sexual orientations and identities within family environments. These strategies seem largely tied to the individual’s unique relationship with family members and their ability to access and maintain important forms of support from those people. Several of the respondents in this study mentioned a strong desire to maintain connection with key family members during and after disclosure. At times, this desire provoked them to disclose and at times it required them to conceal their sexual orientation. Their stories highlight the availability of support from family as central to their own sense of wellness.

Counselors with sufficient time who work with young people who may be considering disclosure should seek to understand these relationships fully and recognize their essential role in an individual’s decision-making process. This may involve assessing the ability of the young person to effectively manage the emotional fallout of potential negative reactions. For some youth who choose to disclose, it may also be important to help them evaluate whether they have alternative sources of emotional and material support, such as housing, on which they could rely should key family members react negatively. As noted by Iasenza, Colucci & Rothberg (1996), counselors should take a family history as part of the process of determining the potential reaction to disclosure. In addition, it may be valuable to consider how family members have responded to differences within the family in the past.

As these narratives attest, young men are aware of the importance of maintaining family support and disclosing before an individual is ready may damage his most important support systems. Therefore, counselors working with LGBITQQ youth who may be considering disclosure should fully consider the individual’s support structures and carefully process the possible reactions to disclosure with each individual. Prior to an individual disclosing his sexual orientation, counselors need to fully assess each individual’s biological and non-biological family structures and support systems. This can assist in helping to provide additional support resources for both the young person and their family members. Additionally, counselors should be aware that disclosing too early and before an individual is developmentally ready to handle the possible conflict and rejection can be traumatic (D'Augelli, 1994).

Similar to Maguen, Floyd, Bakeman & Armistead’s (2002) findings, our narratives suggest that disclosure to family members is not necessarily the marker of the end of the sexual identity formation process nor is it necessarily a prerequisite for overall wellness (Dew, Myers & Wightman 2005). These stories highlight that individuals may move through different levels of disclosure as their identity and relationships shift and change. Counselors should be aware of the heterogeneity of disclosure strategies among LGBTIQQ youth and support individuals as they move through the different stages of disclosure.

School counselors and others serving LGBTIQQ youth with limited time, should be realistic about how much they can actually do to support a youth in the coming out process given the high degree of complexity of this process that our data revealed. Therefore, counselors with limited time should even more so, be prepared with referrals to high quality gay affirming counseling resources that can spend more time with the youth.

Limitations of the Study and Implications for Future Research

The observation that the Filipino and African American young men were more likely to be placed in the Conceal or Vague Disclosure categories, coincides with Dubé and Savin-Williams’ (1999) findings that ethnicity is one, among many, important variables to consider when examining the timing and sequence of disclosure. This study, designed to cover a broad range of topics relating to the experiences of a diverse sample of sexual minority youth, was not intended to specifically examine the role of ethnicity in the disclosure process. However, these results support the need for future research to diversify their samples, which historically have been largely white and male, and examine the cultural relationships (i.e., religion, language, family support and structure) that may exist in determining one’s unique process of disclosing sexual orientation.

Although many questions addressed relevant topics, this study was part of a larger study and not designed to expressly examine disclosure and its relationship to family structure and support. The decision to have participants define “family” themselves allowed each individual’s unique support systems to emerge more fully and highlighted the extent to which non-biological family members play important supportive roles in these young men’s lives. However, analysis of the intergenerational differences that may influence disclosure to biological family members is limited as these individuals may or may not have appeared on the participant’s family circle. While several questions were asked about family relationships, support, and levels of openness about sexual orientation, if respondents were asked specifically to reflect on this topic, more detail about parental reactions and post-disclosure relationships may have emerged.

The voices of this study, like many that have examined sexual minority youth, are of the young men themselves. In order to glean a more thorough and accurate picture of how disclosure influences family relationships and level of support, parents’ points of view need to be included in future research. Additionally, these young men may change their decisions around identity and disclosure as their lives and relationships shift and change, just as the reactions of their family members are likely to change.

Because the majority of the recruitment was from gay-identified venues, this sample may have included youth who are more connected to the gay community and therefore better integrated into that community. Likewise, this sample may have had a larger-than-average percentage of youth who have disclosed and were willing to participate this research project. Research focusing on sexual minority youth with less connection to gay communities and spaces may reveal a different continuum of disclosure strategies.

An additional limitation is that this study was cross-sectional in nature; therefore it did not allow an examination of changes in family relations over time. It is essential that we gain greater insight into what influences a long-term healthy post-disclosure relationship between sexual minorities and their families, by conducting longitudinal research focusing on the evolution of the parent-child relationship before, during and after disclosure.

Conclusion

The ethnically diverse YMSM featured in this study made careful considerations and negotiations when deciding to disclose their sexual orientation to family members. One key component of this decision was how disclosure may influence the support they receive from family. Many of the young men described the ways in which they navigate disclosure in order to access and maintain certain available forms of support. The data revealed several stages of disclosure (Conceal, Vague/Indirect, Selective and Full). Interestingly, several young men seemed to move in an out of each category with different family members. This movement seemed largely tied to the support they received from that particular family member. The results of this study support future research, which can provide counselors with a broader framework through which to address issues of support and disclosure.

Table 1.

Disclosure Categories by Ethnic Identity

| Conceal/No Disclosure |

Vague/Indirect Disclosure |

Selective Disclosure |

Full Disclosure |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 10 |

| API (Filipino Descent) | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 10 |

| Latino (Mexican Descent) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 10 |

| White | 0 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 12 |

| Total | 8 | 3 | 7 | 24 | 43 |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the staff who contributed to collection and analysis of this data: Donna Lopez, Bryce McDavitt, Marcia Reyes, Anamara Ritt-Olson, Conor Schaye, Siavoche Siassi, and Brandon Tseng. We would also like to acknowledge the insightful commentary of the members of The Community Advisory Board: Noel Alumit, Asian Pacific AIDS Intervention Team, Chi-Wai Au, LA County Dept of Health Services, Ivan Daniels III, Los Angeles Black Pride, Ray Fernandez, AIDS Project Los Angeles, Trent Jackson, Youth, Dustin Kerrone, LA Gay and Lesbian Center, Miguel Martinez, Division of Adolescent Medicine, CHLA, Ariel Prodigy, West Coast Ballroom Scene, Brion Ramses, West Coast Ballroom Scene, Ricki Rosales, City of LA, AIDS Coordinator’s Office, Haquami Sharpe, Minority AIDS Project

Support for the original research was provided by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (R01 DA015638-03).

Biographies

Julie Carpineto is a Research Associate at the Community Health Outcomes and Intervention Research (CHOIR) program at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA). Her research interests include; sexual identity development among youth, identity expression among youth, as well as community-based participatory research practices.

Ellen Iverson, MPH, is Deputy Director of the CHOIR program at CHLA.

Katrina Kubicek, PhDc, is an Ethnographer with the CHOIR program at CHLA.

George Weiss is Program Director of the Healthy Young Men’s study at CHLA.

Michele D. Kipke, PhD, is a Professor of Pediatrics and Preventive Medicine at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California and Director of the CHOIR program at CHLA.

References

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari A. The discovery that an offspring is gay: Parents', gay men's, and lesbians' perspectives. Journal of Homosexuality. 1995;30(1):89–112. doi: 10.1300/J082v30n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass V. Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality. 1979;4(3):219. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR. Identity development and sexual orientation: Toward a model of lesbian, gay, and bisexual development. In: Trickett EJ, Watts RJ, Birman D, editors. Human diversity: Perspectives on people in context. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1994. pp. 312–333. [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR, Hershberger SL. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings: Personal challenges and mental health problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21(4):421–448. doi: 10.1007/BF00942151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dew BJ, Myers JE, Wightman LF. Wellness in adult gay males: Examining the impact of internalized homophobia, self-disclosure, and self-disclosure to parents. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 2005;1(1):23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM. What we got wrong about sexual identity development: Unexpected findings from a longitudinal study of young women. In: Omoto A, Kurtzman H, editors. Sexual orientation and mental health: Examining identity and development in lesbian, gay, and bisexual people. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2005. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz R. Latino gay men and HIV: Culture, sexuality and risk behavior. New York: Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dubé EM, Savin-Williams RC. Sexual identity development among ethnic sexual-minority male youths. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(6):1389–1398. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.6.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason MM. Identity formation for lesbian, bisexual, and gay persons: Beyond a "minoritizing" view. Journal of Homosexuality. 1996;30(3):31–58. doi: 10.1300/J082v30n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elizur Y, Ziv M. Family support and acceptance, gay male identity formation, and psychological adjustment: A path model. Family Process. 2001;40(2):125–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4020100125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassinger RE, Miller BA. Validation of an inclusive model of sexual minority formation on a sample of gay men. Journal of Homosexuality. 1996;32(2):53–78. doi: 10.1300/j082v32n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty JA, Richman JA. Effects of childhood relationships on the adult's capacity to form social supports. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;143(7):851–855. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.7.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. Emergence versus forcing: Basics of grounded theory analysis. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gonsiorek JC. Mental health issues of gay and lesbian adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health Care. 1988;9:114–122. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(88)90057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetrick ES, Martin AD. Developmental issues and their resolution for gay and lesbian adolescents. Journal of Homosexuality. 1987;14(1–2):25–43. doi: 10.1300/J082v14n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier L. "It's a catch 22": Same sex attracted young people on coming out to parents. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2002;97:75–91. doi: 10.1002/cd.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz JL, Newcomb MD. A multidimensional approach to homosexual identity. Journal of Homosexuality. 2001;42(2):1–19. doi: 10.1300/j082v42n02_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J, Mallon G. Gay and lesbian adolescent development: Dancing with your feet tied together. In: Greene BC, Croom G, editors. Gay and lesbian development: Education, research and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. pp. 226–243. [Google Scholar]

- Iasenza S, Colucci PL, Rothberg B. Coming out and the mother-daughter bond. In: Laird J, Green RJ, editors. Lesbians and gays in couples and families. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1996. pp. 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kennamer JD, Honnold J, Bradford J, Hendricks M. Differences in disclosure of sexuality among African American and White gay/bisexual men: Implications for HIV/AIDS prevention. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12(6):519–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipke MD, Weiss G, Ramirez M, Dorey F, Ritt-Olsen A, Iverson E, et al. Club drug use in Los Angeles among young men who have sex with men. Substance Use and Misuse. doi: 10.1080/10826080701212261. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Sceery A. Attachment in late adolescence: Working models, affect regulation, and representations of self and others. Child Development. 1988;59:135–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser J, Tharinger D. Visibility management in school and beyond: A qualitative study of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26:234–244. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(02)00132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguen S, Floyd FJ, Bakeman R, Armistead L. Developmental milestones and disclosure of sexual orientation among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2002;23:219–233. [Google Scholar]

- McCarn SR, Fassinger RE. Revisioning sexual minority identity formation: A new model of lesbian identity and its implications for counseling and research. The Counseling Psychologist. 1996;24:508–534. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JR, Boon SD. Trust and disclosure of sexual orientation in gay males' mother-son relationships. Journal of Homosexuality. 2000;38(3):41–63. doi: 10.1300/j082v38n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales ES. Ethnic minority families and minority gays and lesbians. Marriage and Family Review. 1990;14:214–239. [Google Scholar]

- Mosher CM. The social implications of sexual identity formation and the coming-out process: A review of the theoretical and empirical literature. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families. 2001;9(2):164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Futterman D. Lesbian & gay youth: Care and counseling. New York: Columbia University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Ethnic/racial differences in the coming-out process of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: A comparison of sexual identity development over time. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10(3):215–228. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason BR, Pierce GR, Bannerman A, Sarason IG. Investigating the antecedents of perceived social support: Parents' views of and behavior toward their children. Journal of Social Psychology. 1993;66(3):1071–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Coming out to parents and self-esteem among gay and lesbian youth. Journal of Homosexuality. 1989;17(3):1–35. doi: 10.1300/J082v18n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Gay and lesbian youth: Expressions of identity. New York: Hemisphere; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Mom, Dad. I'm gay. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Diamond LM. Sexual identity trajectories among sexual-minority youths: Gender comparison. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2000;29(6):607–627. doi: 10.1023/a:1002058505138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Dubé EM. Parental reactions to their child's disclosure of a gay/lesbian identity. Family Relations. 1998;47:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Telljohann SK, Price JH. A qualitative examination of adolescent homosexuals' life experiences: Ramifications for secondary school personnel. Journal of Homosexuality. 1993;26(1):41–56. doi: 10.1300/J082v26n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe V, Harbeck K. Addressing the needs of lesbian, gay and bisexual youth: The origins of Project 10 and school-based intervention. In: Harbeck K, editor. Coming out of the classroom closet: Gay and lesbian students, teachers and curricula. New York: The Haworth Press; 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldner LK, Magruder B. Coming out to parents: Perceptions of family relations, perceived resources, and identity disclosure for gay and lesbian adolescents. Journal of Homosexuality. 1999;37(2):83–100. doi: 10.1300/J082v37n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells-Lurie L. Working with parents of gay and lesbian children. In: Alexander CJ, editor. Gay and lesbian mental health: A sourcebook for practitioners. New York: Harrington Park Press; 1996. pp. 159–171. [Google Scholar]