Abstract

A procedure for the synthesis of oxazolidinone and tosyl enamines is reported. Alkynoyl oxazolidinones and tosyl imides undergo reaction to form enamines in the presence of catalytic amounts of tertiary amines. The data suggest that an amide anion is formed during the reaction, which undergoes conjugate addition to form the final product.

Keywords: enamine, oxazolidinone, tosyl imide, catalysis

Enamines have become widely used intermediates in organic synthesis since the development of facile methods for their use in the alkylation and acylation of carbonyl compounds by Stork.1 These substrates are able to form carbon–carbon bonds easily, and the use of chiral amines provides an entry into asymmetric syntheses.2 Over the past decade, there has been an expansion of the reactions that may undergo enamine organocatalysis, such as α-oxidations3 and alkylations,4 aldol condensation,5 Michael additions,6 and enantioselective reductions.7 These developments have been showcased in the recent syntheses of (−)-anisomycin8 and (+)-conicol.9 The present report describes a method for preparing enamine products from N-propynoyl oxazolidinones and tosyl imides through tertiary amine catalysis.

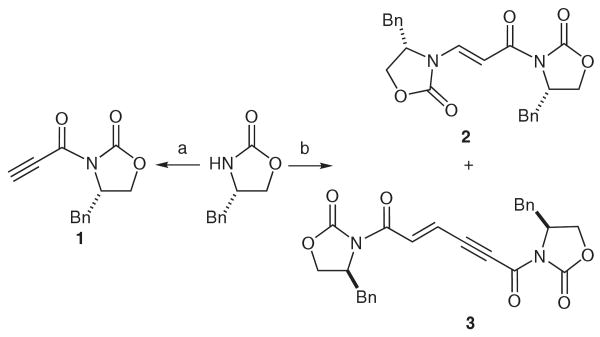

In the process of synthesizing N-propynoyl-(4S)-4-benzyl-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one (1) by Evans' conditions10 to prepare analogues of locostatin, an N-crotonyl oxazolidinone that inhibits cell migration and disrupts specific protein–protein interactions involved in the regulation of cell signaling,11 we unexpectedly discovered that the reaction underwent a secondary transformation to yield the bis-oxazolidinone enamine 2 (Scheme 1). The structure was confirmed by one- and two-dimensional NMR and ESI-MS (Table S1 in Supporting Information).12 In addition, compound 2 was hydrolyzed under acidic conditions and found to react sluggishly, suggesting that the presence of the electron-withdrawing group adversely affects the ability of the enamine to undergo hydrolysis.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of N-propynoyl-(4S)-4-benzyl-1,3-oxazolidin-2-one (1), its enamine derivative 2 and its ene-yne dimer derivative 3. Reagents and conditions: (a) 1. n-BuLi, THF, −78 °C;. 2. propiolic acid, pivaloyl chloride, K2CO3, THF, r.t.; (b) 1. n-BuLi, THF, −78 °C; 2. propiolic acid, pivaloyl chloride, Et3N, −78 °C to 0 °C.

To explain how 2 arose from the reaction, we first explored generation of 1. Replacing Et3N with K2CO3 as the base allowed for generation of the propynoyl mixed anhydride, thus facilitating synthesis of 1 in 42% yield without formation of 2 (Scheme 1). Exposure of 1 to not only stoichiometric but also substoichiometric amounts of Et3N gave 2, along with the ene-yne dimer 3 (Table 1, entries 1–7, and Table S2 in Supporting Information), implying a catalytic reaction. Alternative amines were used at 15 mol% catalyst loading in different solvents, and we found that DABCO also catalyzed the reaction at room temperature (Table 1, entries 8–14). No reaction was observed with DIPEA or imidazole (Table 1, entries 16 and 17). With (−)-sparteine (Table 1, entry 15), mild heating was required for the reaction to reach completion. Other solvents with 15 mol% Et3N and DABCO were screened (Table 1, entries 1–14). The catalyst–solvent system of Et3N in toluene gave the best results with an 86% yield of 2 (Table 1, entry 7). From these data, we concluded that the reaction requires a nucleophilic tertiary amine with diminished steric encumbrance, since imidazole and DIPEA failed to react and (–)-sparteine required mild heating.

Table 1. Solvents and Amines Tested for Formation of 2 and 3a.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Amine | Solvent | Yield of 2 (%) and E:Z ratiob | Yield of 3 (%)b |

| 1 | Et3N | MeCN | 36 (12:1) | tracec |

| 2 | Et3N | benzene | 19 (99:1) | 2 |

| 3 | Et3N | CHCl3 | 20 (1:1) | 25 |

| 4 | Et3N | Et2O | 49 (3:2) | tracec |

| 5 | Et3N | EtOAc | 65 (12:1) | tracec |

| 6 | Et3N | THF | 20 (99:1) | 8 |

| 7 | Et3N | toluene | 86 (14:1) | tracec |

| 8 | DABCO | MeCN | 37 (99:1) | 31 |

| 9 | DABCO | benzene | 65 (99:1) | 14 |

| 10 | DABCO | CHCl3 | 56 (99:1) | 5 |

| 11 | DABCO | Et2O | 43 (4:1) | 5 |

| 12 | DABCO | EtOAc | 54 (8:1) | 28 |

| 13 | DABCO | THF | 16 (99:1) | 51 |

| 14 | DABCO | toluene | 60 (20:1) | 25 |

| 15 | (−)-sparteined | THF | 24 (99:1) | 7 |

| 16 | DIPEA | THF | –e | –e |

| 17 | imidazole | THF | –f | –f |

Reactions were performed at 0.22 M and 15 mol% amine at 24 °C.

Isolated yield and E:Z ratio in parentheses.

Trace signifies less than 1% product.

Reaction was performed at 0.22 M, 15 mol% amine at 50 °C.

No reaction, with 62% recovered starting material.

No reaction, with 33% recovered starting material.

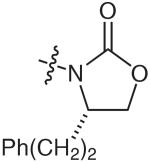

Other systems (N-propynoyl oxazolidinones and tosyl imides) also underwent a similar reaction with catalytic Et3N (Table 2) in toluene. While the original oxazolidinone substrate 1 (Table 2, entry 1) furnished the enamine 2 with a yield of 86%, the other oxazolidinone substrates reacted to form enamine products with reduced yields of 26–38% (Table 2, entries 2–4). The tosyl imides, however, gave enamine products with 55–72% yields (Table 2, entries 7–10). Interestingly, the reaction appeared to necessitate the presence of an electron-withdrawing group, since tertiary and secondary alkyl ynamides failed to react under the same conditions (Table 2, entries 5 and 6). This result suggests that the oxazolidinone or tosyl moieties presumably act to facilitate the displacement of the nitrogen anion from the alkynoyl imide, as well as to decrease the hardness of the nitrogen anion to allow for conjugate addition onto a second molecule of the alkynoyl imide.

Table 2. Enamine and Ene-Yne Dimer Products from Et3N-Catalyzed Reaction of N-Propynoyl Oxazolidinones and Tosyl Imidesa.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | Yield of A (%)b | Yield of B (%)b |

| 1 |  |

86 | tracec |

| 2 |  |

26 | 8 |

| 3 |  |

38 | 6 |

| 4 |  |

38 | 9 |

| 5 |  |

–c | –c |

| 6 |  |

–c | –c |

| 7 |  |

58 | traced |

| 8 |  |

68 | traced |

| 9 |  |

72 | traced |

| 10 |  |

55 | traced |

Reactions were performed at 0.22 M and 15 mol% Et3N.

Isolated yield.

No observable reaction.

Trace denotes <1% product.

The mechanism of the reaction presumably begins with conjugate addition of the tertiary amine onto the ynamide to form an allenoate intermediate.13 The allenoate undergoes elimination of the amide anion to generate the nucleophile for subsequent addition onto a separate ynamide moiety, forming the enamine. Alternatively, the allenoate mediates deprotonation of the acetylenic hydrogen of another equivalent of substrate to ultimately form the eneyne dimer (Scheme 2).14 Treatment of 1 with NaH and 20% aqueous DCl in D2O gave deuterated 1, which was subjected to the catalytic conditions with DABCO and Et3N. We found that in both cases, the β position of the enamine product retained high levels of the deuterium label (70% for DABCO and 58% for Et3N), while the α-position contained lower levels (26% for DABCO and 39% for Et3N). The data suggest that it is more likely that deprotonation occurs through residual water than by direct deprotonation of the acetylenic hydrogen. Quenching the reaction mixture with TMSCl or 20% aqueous DCl in D2O resulted in no incorporation of the trapping species in the final enamine product. Thus, the vinyl anion may not be neutralized during the aqueous workup, and the proton must be incorporated during the reaction.

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism of enamine formation; EWG = electron-withdrawing group

We have found that N-propynoyl oxazolidinones and tosyl imides will form enamine products when exposed to catalytic amounts of Et3N and DABCO.15 The reaction involves conjugate addition of the tertiary amine onto the alkynoyl imide β carbon to furnish a putative allenoate intermediate. The allenoate then undergoes elimination of an amide (or carbamate) anion, generating the final nucleophile for product formation. This reaction could be used to furnish alternative enamines to yield asymmetric aldol products.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Profs. Philip P. Garner, Duncan J. Wardrop, John T. Wood and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM077622).

Footnotes

Supporting Information for this article is available online at http://www.thieme-connect.com/ejournals/toc/synlett.

References and Notes

- 1.Stork G, Brizzolara A, Landesman H, Szmuszkovicz J, Terrell R. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;85:207. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Hayashi Y, Otaka K, Saito N, Narasaka K. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1991;64:2122. [Google Scholar]; (b) List B. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:5573. [Google Scholar]; (c) List B. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:548. doi: 10.1021/ar0300571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mukherjee S, Yang JW, Hoffmann S, List B. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5471. doi: 10.1021/cr0684016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hodgson DM, Kaka NS. Angew Chem. 2008;120:10106. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown SP, Brochu MP, Sinz CJ, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10808. doi: 10.1021/ja037096s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vignola N, List B. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:450. doi: 10.1021/ja0392566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) List B, Lerner RA, Barbas CF., III J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:2395. [Google Scholar]; (b) List B, Pojarliev P, Castello C. Org Lett. 2001;3:573. doi: 10.1021/ol006976y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) List B, Castello C. Synlett. 2001:1687. [Google Scholar]; (d) Pidathala C, Hoang L, Vignola N, List B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:2785. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Yang JW, Hechavarria Fonseca MT, List B. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15036. doi: 10.1021/ja055735o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Garcia-Garcia P, Ladepeche A, Halder R, List B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:4719. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Yang JW, Hechavarria Fonseca MT, List B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:6660. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ouellet SG, Tuttle JB, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:32. doi: 10.1021/ja043834g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Martin NJA, List B. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13368. doi: 10.1021/ja065708d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tuttle JB, Ouellet SG, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12662. doi: 10.1021/ja0653066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chouthaiwale PV, Kotkar SP, Sudalai A. ARKIVOC. 2009;ii:88. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong BC, Kotame P, Tsai CW, Liao JH. Org Lett. 2010;12:776. doi: 10.1021/ol902840x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Evans DA, Bartroli J, Shih TL. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:2127. [Google Scholar]; (b) Evans DA, Gage JR, Leighton JL. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:9434. [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) McHenry KT, Ankala SV, Ghosh AK, Fenteany G. ChemBioChem. 2002;3:1105. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20021104)3:11<1105::AID-CBIC1105>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhu S, McHenry KT, Lane WS, Fenteany G. Chem Biol. 2005;12:981. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Guo J, Wu HW, Hu G, Han X, De W, Sun YJ. Neuroscience. 2006;143:827. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Mc Henry KT, Montesano R, Zhu S, Beshir AB, Tang HH, Yeung KC, Fenteany G. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:972. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ma J, Li F, Liu L, Cui D, Wu X, Jiang X, Jiang H. Liver Int. 2009;29:567. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.01981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Beshir AB, Argueta CE, Menikarachchi LC, Gascón JA, Fenteany G. Forum Immunopath Dis Ther. 2011;2:47. doi: 10.1615/forumimmundisther.v2.i1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Compound 2 appeared as a single band from chromatographic techniques; additionally, compound 2 underwent palladium hydrogenation, and its spectra were in accordance with the reduced enamine (see Supporting Information).

- 13.(a) Winterfeldt E. Chem Ber. 1964;97:1952. [Google Scholar]; (b) Crisp GT, Millan MJ. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:637. [Google Scholar]; (c) Matsuya Y, Hayashi K, Nemoto H. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:646. doi: 10.1021/ja028312k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Matsuya Y, Hayashi K, Nemoto H. Chem Eur J. 2005;11:5408. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Fan MJ, Li GQ, Liang YM. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:6782. [Google Scholar]

- 14.The freed allenone yielded a black tar, possibly the result of decomposition or polymerization.

- 15.For experimental procedures and compound characterization data, see Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.