Abstract

Objectives

Labeling biomolecules with 18F is usually done through coupling with prosthetic groups, which requires several time-consuming radiosynthesis steps and therefore results in low labeling yield. In this study we designed a simple one-step 18F-labeling strategy to replace the conventional complex and long process of multiple-step radiolabeling procedure.

Methods

Both Monomeric and dimeric cyclic RGD peptides were modified to contain 4-NO2-3-CF3 arene as precursors for direct 18F labeling. Binding of the two functionalized peptides to integrin αvβ3 was tested in vitro using MDA-MB-435 human breast cell line. The most promising functionalized peptide, the dimeric cyclic RGD, was further evaluated in vivo in an orthotopic MDA-MB-435 tumor xenograft model.

Results

The use of relatively low amount of precursor (~0.5μmol), gave reasonable yield, ranging from 7–23% (decay corrected, calculated from start of synthesis) after HPLC purification. Overall reaction time was 40 min and the specific activity of the labeled peptide was high. Modification of RGD peptides did not significantly change the biological binding affinities of the modified peptides. Small animal PET and biodistribution studies revealed integrin specific tumor uptake and favorable biokinetics.

Conclusions

We have developed a novel one-step 18F radiolabeling strategy for peptides that contain a specific arene group, which shortens reaction time and labor significantly, requires low amount of precursor and results in specific activity of 79 ± 13 GBq/μmol. Successful introduction of 4-fluoro-3-trifluoromethylbenzamide into RGD peptides may be a general strategy applicable to other biologically active peptides and proteins.

Keywords: 18F-fluoride, direct fluorination, PET, RGD peptides, integrin αvβ3

INTRODUCTION

Labeling peptides and proteins with 18F-F− is usually done in several radiosynthesis steps using prosthetic groups, which can be attached to the biomolecule, mostly through amino- or thiol-reactive groups via acylation, alkylation, amidation, imidation, oxime or hydrazone formations (1–8). The choice of prosthetic group for the labeling should take into account the complexity of its radiosynthesis, which in general requires number of lengthy radiosynthesis steps, and therefore results in relatively low labeling yield. Multistep synthesis is also not amenable for automation.

One alternative route for labeling bioactive molecules is 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of terminal alkynes and azides in the presence of Cu(I) as a catalyst, to give the corresponding triazole (click chemistry). 18F-click chemistry has been used in several studies for labeling peptides (5, 7, 9–11). However, it requires the preparation of azide or alkyne functional group modified peptides, two radiochemical synthesis steps, and in some cases, it involves volatile 18F-azide synthon.

There have been several attempts to develop a direct labeling of peptides with 18F (12–15). Höhne et al. (12) showed a direct 18F-fluoride labeling on di-tert-butyl silyl functionalized bombesin analogues. Although their peptides were stable in the blood, low tumor uptake was observed probably due to the high lipophilicity of the modified bombesin peptides. Becaud et al. (14) reported on the direct one-step labeling of peptides via 18F-fluoride nucleophilic aromatic substitution using trimethylammonium as a leaving group without in vivo data. Roehn et al. (15) described the one-step labeling with 18F-fluoride via ring opening of activated aziridines. However, the 18F-fluoride incorporation yield is rather low. McBride and Laverman et al. (16–17) reported on the chelation of 18F-aluminum fluoride (Al18F) by 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid (NOTA) conjugated Octreotide.

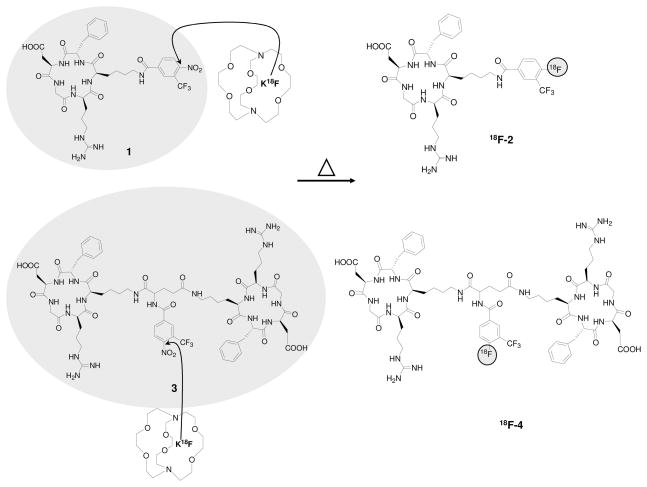

Introduction of no-carrier-added 18F-fluoride into aromatic compounds is mostly limited to substitution on electron-deficient arenes. Nitro is a known leaving group for aromatic nucleophilic substitution (18–20). The presence of electron-withdrawing groups, such as cyano, trifluoromethyl, aldehyde, ketone and nitro, in the ortho or para positions on the aromatic ring decreases the electron density, which allows sufficient activation for the nucleophilic substitution (5, 21). Here we report on a new straightforward one-step labeling strategy with 18F-fluoride by displacing a nitro group in an arene that is activated toward nucleophilic aromatic substitution by an ortho trifluoromethyl group. We applied this new labeling method to cyclic Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide derivatives containing 4-nitro-3-trifluoromethyl arene as precursors for the direct F-18 labeling (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

One-step 18F-labeling of RGD peptides.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

General

Kryptofix 2.2.2 was purchased from EMD Chemicals (Darmstadt, Germany). All other solvents and chemicals were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO). c(RGDfk) and E[c(RGDfk)2] were purchased from Peptide International (Louisville, KY). 18F-fluoride was obtained from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center (CC) cyclotron facility by irradiation of an 18O-water target by the 18O(p,n)18F nuclear reaction. C18 cartridges (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) were each activated with 5 mL of EtOH and 10 mL of water.

Mass spectrometry analysis

LC/MS analysis employed a Waters LC-MS system (Waters, Milford, MA) that included an Acquity UPLC system coupled to the Waters Q-Tof Premier high resolution mass spectrometer. An Acquity BEH Shield RP18 column (150 × 2.1 mm) was employed for chromatography. Elution was achieved with a binary mixture of two components. Solution A was composed of 2 mM ammonium formate, 0.1% formic acid, and 5% acetonitrile (ACN); solution B was composed of 2 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid in ACN. The elution profile, at 0.35 mL/min, had the following components: initial condition at 100% (v:v) A and 0% B; gradient 0–40% B over 5 min; isocratic elution at 40% B for an additional 5 min; 40–80% B over 2 min; and re-equilibrated with A for an additional 3 min. The retention time for 1 and 3 were 9.8 min and 5.8 min, respectively. The retention time for 2 and 4 were 9.2 min and 5.4 min, respectively. The injection volume was 10 μL. The entire column eluent was introduced into the Q-Tof mass spectrometer. Ion detection was achieved in ESI mode using a source capillary voltage of 3.5 kV, source temperature of 110°C, desolvation temperature of 200 °C, cone gas flow of 50 L/H (N2), and desolvation gas flow of 700 L/H (N2).

Synthesis of 4-nitro-3-trifluoromethylbenzoyl chloride

4-Nitro-3-trifluoromethybenzoic acid (1.06 g, 4.5 mmol) was treated with α, α-dichloromethyl methyl ether (0.6 mL, 6.75 mmol). One mL of dichloroethane was added, and the reaction was heated at 50 °C for 4 h. Full conversion to the acid chloride was verified by GC-MS. The solvent and excess reagents were evaporated and the residual oil was distilled in a Kugelrohr apparatus (140° C, 1 mm) to give 0.9 g (3.55 mmol) of the desired 4-nitro-3-trifluoromethybenzoyl chloride. The oil solidified upon standing and was used without any additional manipulations. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.04-7.99 (d, 2H), 8.52-8.43 (dd, 2H), 8.57 (d, 2H). GC–MS (CI–CH4) 253.95 (M+).

Synthesis of 4-nitro-3-trifluoromethylbenzoyl-c(RGDfk) (1) and 4-nitro-3-trifluoromethylbenzoyl-E[c(RGDfk)2] (3)

The conjugation procedure of 4-nitro-3-trifluoromethylbenzoyl chloride with monomeric RGD peptide c(RGDfK) and dimeric RGD peptide E[c(RGDfK)]2 was conducted by dissolving the peptide (8–10 mg) in 0.3–0.5 mL N,N-dimethylformamide. Then, 1.2 eq. of 4-nitro-3-trifluoromethylbenzoyl chloride were added, followed by adding 10 eq. of triethylamine. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for several hours. Purification of 1 and 3 was conducted on a reversed-phase HPLC system using a Higgins C18 column (5 μm, 20 × 250 mm). The flow was set at 12 mL/min using two gradient systems; for 1, starting from 95% of solvent A (0.1% TFA in water) and 5% of solvent B (0.1% TFA in ACN) and increasing to 35% solvent A and 65% solvent B at 32 min. The retention time of 1 under these conditions was 27.1 min. For compound 3, the gradient started from 95% of solvent A and 5% of solvent B and increasing to 35% solvent A and 65% solvent B at 35 min. The retention time of 3 under these conditions was 26.3 min. The desired functionalized conjugated peptides (compounds 1 and 3) were collected and the solvents were removed by lyophlization. The purities of 1 and 3 were determined by injection into analytical HPLC, using Phenomenex C18 column (Luna, 5 μm, 250 × 4.6 mm) at flow rate of 1 mL/min and a gradient system starting from 70% of solvent A and 30% of solvent B and increasing to 60% solvent A and 40% solvent B at 35 min. The retention times of 1 and 3 on this system were 17.3 min and 13.1 min, respectively. LC–MS also confirmed the mass of the conjugated peptides: 1, 821.37 [M+H]+, calculated: 820.31; 3, 1535.70 [M+H]+, calculated: 1534.66.

Synthesis of 4-fluoro-3-trifluoromethylbenzoyl-c(RGDfk) (2) and 4-fluoro-3-trifluoromethylbenzoyl-E[c(RGDfk)2] (4)

Non-radioactive standards for 18F-2 and 18F-4 were prepared by conjugation of c(RGDfk) and E[c(RGDfk)2] with the commercially available 4-fluoro-3-trifluorobenzoyl chloride, under the same conditions as described above. The conjugation of 4-fluoro-3-trifluorobenzoyl chloride with the peptides was confirmed by LC-MS analysis: 2, 794.40 [M+H+], calculated: 793.32; 4, 1508.90 [M+H+], calculated: 1507.66. The purities of 2 and 4 were determined by the same analytical HPLC conditions described above for compounds 1 and 3. The retention time of 2 and 4 on this system were 16.9 min and 12.5 min, respectively.

Synthesis of 4-18F-fluoro-3-trifluoromethylbenzoyl-c(RGDfk) (18F-2) and 4-18F-fluoro-3-trifluoromethylbenzoyl-E[c(RGDfk)2] (18F-4)

Reactive 18F-fluoride ion was prepared by adding to 50–100 μL 18F/H218O solution (0.74–2.22 GBq), K2CO3 (1.38 mg, 10 μmol), and Kryptofix in 500 μL ACN (7.52 mg, 20 μmol). Azeotropic removal of water was achieved by adding 500 μL ACN and evaporation by heating under a stream of argon. Adding a second portion of ACN (500 μL) followed by evaporation further removes the remaining water. The dried K18F•Kryptofix 2.2.2 complex was then dissolved in 300 μL anhydrous dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and added to 440–800 μg (~ 0.5 μmol) of the modified peptides (1 and 3) in a screw-cap test tube. The tube was capped, vortexed and heated in the microwave for 3.5 min at 130 °C.

After cooling the reaction vial to ambient temperature in a water bath, the vial content was diluted with 10 mL of water and loaded onto an activated C18 Sep-Pak cartridge. The cartridge was washed with water (10 mL) and the desired labeled peptide (18F-2 or 18F-4) was eluted with 10 mM HCl in ethanol (1 mL) into a glass test tube. The ethanol was evaporated for 2–3 min under a stream of argon at 60 °C and then the crude labeled peptide was diluted with 0.1% TFA/H2O and injected into reversed-phase HPLC using a Phenomenex C18 column (Luna, 5 μm, 250 × 10 mm). The flow was set at 4 mL/min using a gradient system starting from 70% of solvent A (0.1% TFA in water) and 30% of solvent B (0.1% TFA in ACN) and increasing to 60% solvent A and 40% solvent B at 35 min. 18F-2 and 18F-4 were eluted with a retention time of 17 min and 12.7 min, respectively. 18F-2 and 18F-4 were analyzed using HPLC and compared to nonradioactive standards by coinjection.

MDA-MB-435 Cell Culture

MDA-MB-435 cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and grown in Leibovitz’s L-15 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) under a 100% air atmosphere at 37 °C.

Integrin αvβ3 receptor binding assay

MDA-MB-435 cells were scraped off and resuspended with binding buffer [25 mM 2-amino-2-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-propanediol, hydrochloride (Tris-HCl), pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)]. Incubation was conducted in a 96-well plate with a total volume of 200 μL in each well containing 2×105 cells, 0.02 μCi (0.74 kBq) 125I-echistatin (Perkin-Elmer) and 0–5000 nM of c(RGDfk) or unlabeled 2, or 0–500 nM of E[c(RGDfk)2] or unlabeled 4, for 2 h on a shaker at room temperature. After incubation, cells were washed three times with cold phosphate buffer saline (PBS) with 0.1 % BSA. Thereafter, the plate was heated to 40 °C and dried. The dried filter membranes were punched off from the wells and collected in polystyrene culture test tube (12×75 mm).

Cell bound radioactivity was measured using a gamma counter (1480 Wizard 3, Perkin–Elmer). The IC50 values were calculated by nonlinear regression analysis using the GraphPad Prism computer-fitting program (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Each data point is a result of the average of duplicate wells.

Tumor xenograft model

Athymic nude mice were purchased from Harlan (Frederick, MD) and housed under pathogen free conditions. All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Animals, and under protocols approved by the NIH Clinical Center Animal Care and Use Committee (CC/ACUC). The MDA-MB-435 tumor model was generated by orthotopical injection of 5×106 cells in the left mammary fat pad of female athymic nude mice. The mice were ready for use in 2–3 weeks after tumor inoculation when the tumor size reached 100–300 mm3.

Small animal PET studies

Tumor-bearing mice were anesthetized using isoflurane/O2 (1.5–2% v/v) and injected with 100 μCi (3.7 MBq) of 18F-4. PET scans were performed using an Inveon DPET scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions) at 0.5, 1 and 2 h postinjection (n = 5/group). For blocking experiments, 100 μCi (3.7 MBq) of 18F-4 were co-injected with 300 μg of c(RGDfk) (n = 5). The images were reconstructed by a two-dimensional ordered subsets expectation maximum (2D-OSEM) algorithm, and no correction was applied for attenuation or scatter. Image analysis was done using ASI Pro VM™ software.

Biodistribution

Each tumor-bearing mouse was injected 100 μCi (3.7 MBq) of 18F-4 in a volume of 100 μL phosphate-saline buffer through the tail vein. At 2 h postinjection after the PET scans were completed, blood was drawn from the heart and the mice were then sacrificed. Liver, muscle, kidneys, intestine and tumor were removed (n = 5). The organs were wet weighed and assayed for radioactivity using a gamma counter.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± SD. Two-tailed paired and unpaired Student’s t tests were used to test differences within groups and between groups, respectively. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Synthesis of precursors 1 and 3

4-Nitro-3-trifluoromethylbenzoyl chloride was synthesized via chlorination of the corresponding acid, using α, α-dichloromethyl methyl ether as a chlorination agent (22). The conversion to the desired benzoyl chloride was efficient, with chemical yield of 80%. 4-Nitro-3-trifluoromethylbenzoyl chloride was conjugated to both RGD monomer c(RGDfK) and dimer E[c(RGDfK)]2 in the presence of triethylamine at room temperature to give 1 and 3, which were purified on a reversed-phase HPLC system. Eight to ten mg of c(RGDfK) and E[c(RGDfK)]2 were used for the conjugation to give functionalized conjugated peptides 1 and 3, respectively, which were achieved in reasonable chemical yield of 50–60 % and were sufficient for several radioactive runs. The chemical purity of 1 and 3 from the above reaction was greater than 99%, as determined by analytical HPLC and LC-MS analysis.

Synthesis of standards 2 and 4

The synthesis of unlabeled standards for the fluorination was done in a similar way to 1 and 3 using the commercially available 4-fluoro-3-trifluoromethylbenzoyl chloride. The yields of compounds 2 and 4 were slightly lower (42–46 %) than those of 1 and 3. The chemical purity of 2 and 4 was found to be greater than 99% as determined by analytical HPLC and LC-MS analyses.

Synthesis of 18F-2 and 18F-4

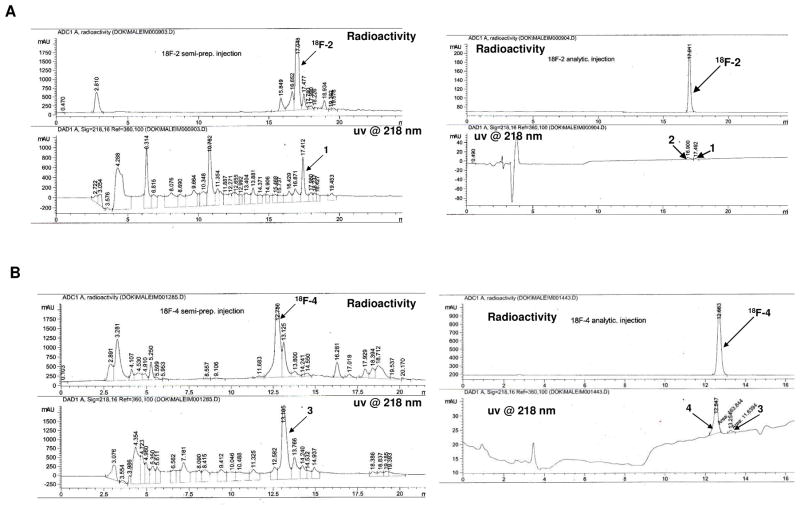

18F-fluoride displacement of the nitro group in 1 and 3, was done rapidly using a microwave device set to a temperature of 130°C and low amount of peptide precursors (~ 0.5 μmol, Figure 1). After 18F-fluoride displacement, the unreacted 18F-fluoride was washed out using activated C-18 sep-pak cartridge and the crude labeled peptides were injected into reversed-phase HPLC system. The incorporation of 18F-fluoride into 1 resulted in one major radioactive peak of the desired labeled peptide 18F-2 with a retention time of 17 min. 18F-4 was eluted from the HPLC with retention time of 12.7 min (Figure 2). The monomeric peptide 18F-2 was achieved in higher radiochemical yield (19 ± 4%, n = 6) than the dimeric peptide 18F-4 (9 ± 2%, n = 4). Both have radiochemical purity greater than 99%, with high specific activity of 79 ± 13 GBq/μmol (SOS). The overall radio-synthesis time to get 18F-2 or 18F-4 formulated and ready for injection, was approximately 40 min.

Figure 2.

(A) Left - HPLC (UV at 218 nm) and radioactivity chromatograms of 18F-2 (injection of crude reaction). 18F-2 was eluted at retention time of 17.04 min.

Right - (A) Analytical HPLC (UV at 218 nm) and radioactivity chromatograms of 18F-2.

(B) Left - HPLC (UV at 218 nm) and radioactivity chromatograms of 18F-4 (injection of crude reaction). 18F-4 was eluted at retention time of 12.75 min.

Right - Analytical HPLC (UV at 218 nm) and radioactivity chromatograms of 18F-4.

It is of note that attempts to perform this direct fluorination using an oil bath at 130 °C for 20 min with the same small amount of conjugated peptides, were also successful and gave similar radiochemical yields.

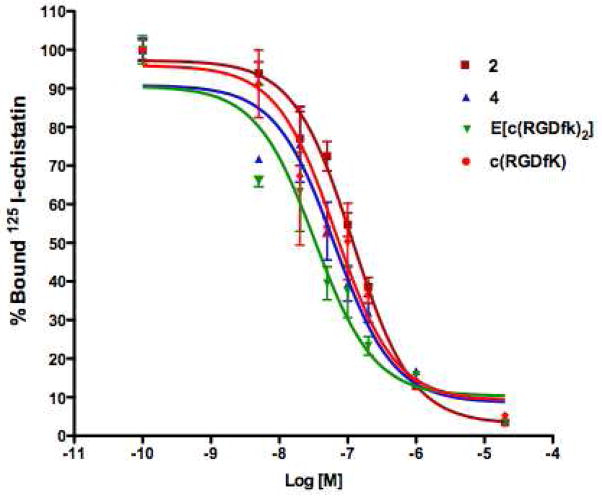

Competitive binding assay with radiolabeled 125I-echistatin

The affinity of 2 and 4 for integrin αvβ3, was tested using the human breast carcinoma cell line MDA-MB-435, which is known to express medium level of integrin αvβ3. Binding affinities of the modified-RGD peptides, 2 and 4, were compared with the non-modified RGD peptides, c(RGDfk) and E[c(RGDfk)2]. The IC50 values of 2 and 4 binding to MDA-MB-435 cells were 119 nM and 63 nM, which were comparable with those of c(RGDfk) (67 nM) and E[c(RGDfk)2] (33 nM), respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Competitive binding assay of RGD-modified peptides (2 and 4) in comparison to the non-modified peptides (c(RGDfK) and E[c(RGDfK)]2) with 125I-echistatin using MDA-MB-435 cells.

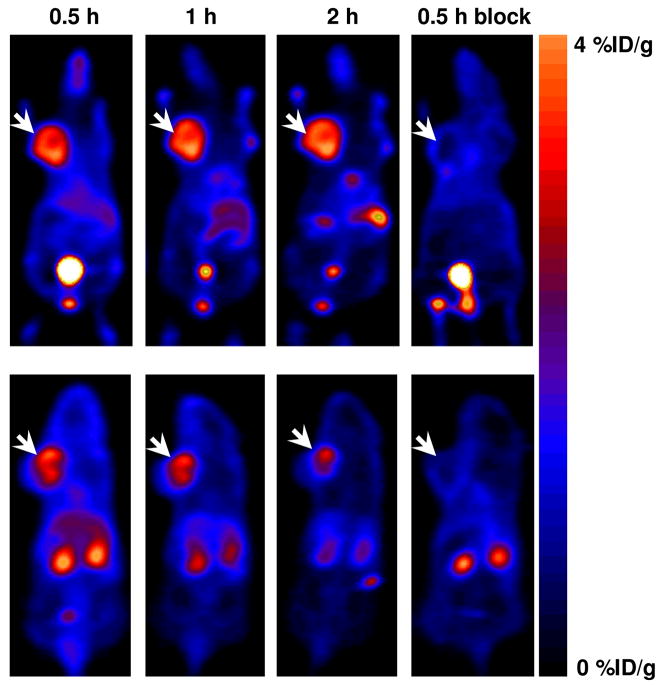

PET imaging and biodistribution

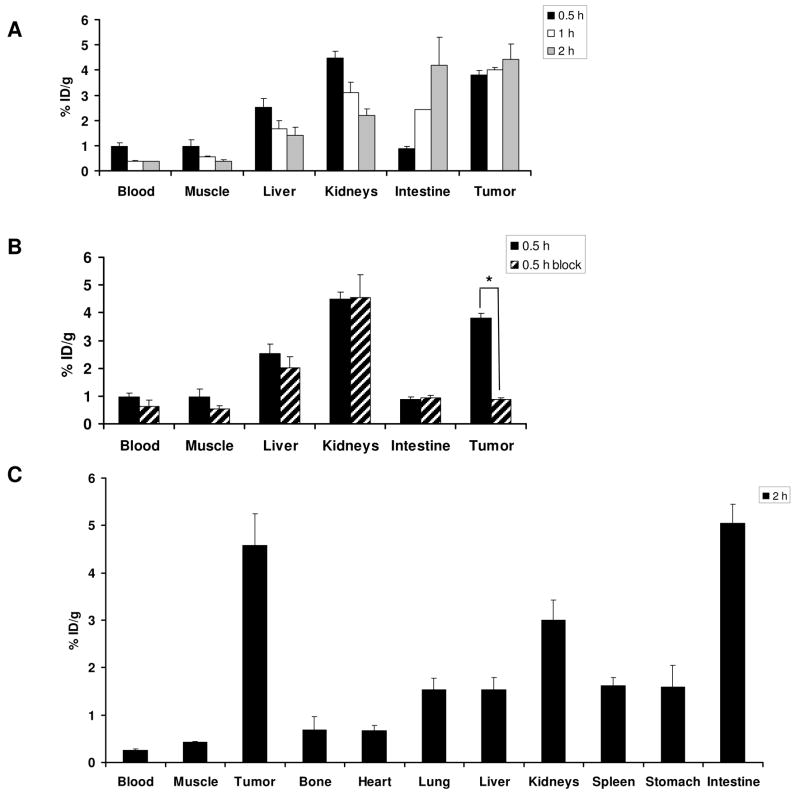

Since compound 4 showed higher affinity for integrin αvβ3 in binding assay than compound 2, it was further evaluated in vivo in orthotopic MDA-MB-435 tumor mice. PET images of 18F-4 were acquired at 0.5, 1 and 2 h postinjection (Figure 4). 18F-4 had initial high tumor uptake (3.8 ± 0.16 %ID/g) and good tumor-to-background contrast at 0.5 h post injection, which was slightly increased at 2 h time point (4.43 ± 0.6 %ID/g, Figures 4 and 5a). At 0.5 h postinjection, 18F-4 uptake in metabolic organs such as liver and intestine was low (2.5 ± 0.3 and 0.87 ± 0.09 %ID/g, respectively, Figures 4 and 5a). At 1 h postinjection, 18F-4 uptake in the liver decreased to 1.67 ± 0.34 %ID/g, however the uptake in the intestine increased (2.43 ± 0.04 %ID/g, Figures 4 and 5a). At 2 h post injection, the uptake in the intestine increased to 4.19 ± 1.1 %ID/g (Figure 5a) and some uptake in the gallbladder was detected (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Representative PET images of an athymic nude mouse bearing orthotopic MDA-MB-435 tumor on the left mammary fat pad, at 0.5, 1 and 2 h postinjection of 100 μCi (3.7 MBq) of 18F-4, or coinjection with 300 μg of c(RGDfK). Upper row – ventral slices, arrows indicate MDA-MB-435 tumor. Lower row – dorsal slices.

Figure 5.

(A) Biodistribution of 18F-4 in MDA-MB-435 tumor-bearing mice at 0.5, 1, and 2 h postinjection of the labeled peptide. (B) Biodistribution of mice injected either with 18F-4 or co-injection of 18F-4 with nonradioactive c(RGDfK) (300 μg), 0.5 h postinjection. Results are calculated from PET scans and are shown as averages of 5 mice ± SD. *P < 0.01. (C) Bioditribution of 18F-4 (calculated from gamma counting of dissected organs) in MDA-MB-435 tumor-bearing mice at 2 h postinjection of the labeled peptide. Results are shown as averages of 5 mice ± SD.

Blocking studies were done by co-injection of 18F-4 with an excess (0.5 μmol) of monomeric c(RGDfk). 18F-4 tumor uptake was reduced by 82 % (Figures 4 and 5b) at 0.5 h, which suggested that the 18F-4 uptake in the tumor is due to a specific binding to integrin αvβ3. The inhibition of 18F-4 uptake in other organs and tissue expressing low level of integrin αvβ3 was also found, which was consistent with previously reported observations (2, 23–25).

In addition to the PET scans, biodistribution of 18F-4 by organ dissection was performed at 2 h postinjection. The results achieved by dissection of the organs and counting using a gamma counter (Figure 5c). Similar to the PET scan data, the uptake in the tumor was 4.57 ± 0.67 %ID/g and the uptake in the intestine was relatively high (5.04 ± 0.39 %ID/g) at 2 h postinjection. Low uptake (0.68 ± 0.28 %ID/g) was detected in the bone (Figure 5c).

DISCUSSION

18F-2 was achieved in higher radiochemical yield than 18F-4. Direct fluorination on monomeric RGD peptide 1, to yield 18F-2, gave lesser radioactive by-products than fluorination on the dimeric RGD, 3, to yield 18F-4 (Figure 2). Future analysis of the byproducts might be beneficial for finding ways to eliminate the by-products and to give better yields.

The 18F-fluoride displacement reaction was conducted at relatively high temperature (130 °C), which resulted in slight decomposition of 1 and 3, as detected by UV at 218 nm (Figures 2a and 2b) but had minimal effect on the labeling efficiency. Attempts to perform the labeling at other temperatures such as 120 and 145 °C did not result in a significant difference in the labeling efficiency as detected by radio-TLC and HPLC (data not shown).

One downside of labeling 1 and 3 is the difficulty of separating the nitro containing precursors (1 and 3) from the desired 18F-labeled products (Figure 2). The specific activity of the final product is thus related to the amount of precursor and radioactivity used for the reaction.

In order to verify that the introduction of substituted arene into the peptide does not affect its biological behavior in vitro, the nonradioactive standards 2 and 4 were tested for binding to integrin αvβ3 expressing MDA-MB-435 cells in a competitive binding assay against 125I-echistatin. Modification of RGD peptides did not change significantly the biological binding affinities in comparison to RGD monomer c(RGDfK) and dimer E[c(RGDfK)]2 (Figure 3).

18F-4 has higher integrin binding affinity than 18F-3 and was further evaluated for its usability as a PET imaging agent by injection into MDA-MB-435 tumor-bearing mice. Biodistribution of 18F-4 was analyzed at 0.5, 1 and 2 h postinjection using PET scans of live animals. At 0.5 h time point, 18F-4 showed very clear image with high tumor to background contrast (Figure 4), high tumor uptake (3.81 ± 0.16 %ID/g) and low accumulation in metabolic organs such as liver and intestine. The tumor uptake elevated at 1 and 2 h postinjection (Figure 5a). However, accumulation of 18F-4 was higher in the intestine at 2 h postinjection (Figures 4 and 5a), suggesting a hepatobiliary clearance of 18F-4. The 18F-labeled RGD peptides are metabolically stable with little to no defluorination as evidenced by very low bone uptake at 2 h time point (Figure 5c) Co-injection of 18F-4 with c(RGDfK) effectively blocked the uptake in the tumor (Figures 4 and 5a) which implies specific binding of 18F-4 to integrin αvβ3. The PET quantification (Figure 5a) was consistent with the results obtained from direct tissue sampling (Figure 5c).

The goal of this study was to develop a robust one-step F-18 labeling method for the dimeric RGD peptide that can be applied for clinical translation. Based on our previous experience, E[c(RGDyK)]2 is more hydrophilic and thus has more rapid renal clearance and improved imaging quality than E[c(RGDfK)]2. However, attempts to label E[c(RGDyK)]2 using this method did not succeed, most likely due to two possible reasons: 1) the OH group of Tyr may undergo deprotonation. This may interfere with the labeling reaction by capturing the fluoride ion, preventing nucleophilic substitution of the nitro group; 2) E[(RGDyK)]2 is not very stable under this condition and thus the precursor may have been partially decomposed. In general, tyrosine containing peptides may not be suitable substrates for this type of fluorination.

Therefore, we applied this labeling method to RGDfk derivatives. Introduction of 4-fluoro-3-trifluoromethylbenzamide into cyclic RGD peptide did not affect the biological properties in vitro or in vivo. The PET imaging and biodistribution results described here are comparable to the previously reported results of the RGDyk dimers (2, 25–26). Nevertheless, the other reported procedures require several radiosynthesis steps, significantly longer reaction time and have similar radiochemical yield. The complex and long process of multiple-step radiolabeling reassured the value of developing an alternative one-step route for labeling. The simplicity of this labeling method makes it amenable for automation and the high PET image quality of one-step 18F-radiolabeled RGD dimer makes it attractive for clinical translation.

CONCLUSIONS

We have developed a novel and rapid one-step F-18 radiolabeling strategy for peptides that contain a specific arene group activated for nucleophilic aromatic substitution with 18F-F−. This method significantly shortens reaction and overall synthesis time, requires low amount of precursor, and provides acceptable yields of high specific activity product. The success of this procedure for RGD peptide labeling can be generalized to other thermally stable peptides and proteins.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program (IRP) of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.Li X, Link JM, Stekhova S, Yagle KJ, Smith C, Krohn KA, Tait JF. Site-specific labeling of annexin V with F-18 for apoptosis imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1684–8. doi: 10.1021/bc800164d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Z, Li ZB, Cai W, He L, Chin FT, Li F, Chen X. 18F-labeled mini-PEG spacered RGD dimer (18F-FPRGD2): synthesis and microPET imaging of αvβ3 integrin expression. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:1823–31. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0427-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen X, Park R, Shahinian AH, Tohme M, Khankaldyyan V, Bozorgzadeh MH, Bading JR, Moats R, Laug WE, Conti PS. 18F-labeled RGD peptide: initial evaluation for imaging brain tumor angiogenesis. Nucl Med Biol. 2004;31:179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Namavari M, Cheng Z, Zhang R, De A, Levi J, Hoerner JK, Yaghoubi SS, Syud FA, Gambhir SS. A novel method for direct site-specific radiolabeling of peptides using [18F]FDG. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:432–6. doi: 10.1021/bc800422b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobson O, Chen X. PET Designated flouride-18 production and chemistry. Curr Top Med Chem. 2010;10:1048–59. doi: 10.2174/156802610791384298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai W, Zhang X, Wu Y, Chen X. A thiol-reactive 18F-labeling agent, N-[2-(4-18F-fluorobenzamido)ethyl]maleimide, and synthesis of RGD peptide-based tracer for PET imaging of αvβ3 integrin expression. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1172–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li ZB, Wu Z, Chen K, Chin FT, Chen X. Click chemistry for 18F-labeling of RGD peptides and microPET imaging of tumor integrin alphavbeta3 expression. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:1987–94. doi: 10.1021/bc700226v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiesewetter DO, Kramer-Marek G, Ma Y, Capala J. Radiolabeling of HER2 specific Affibody® molecule with F-18. J Fluor Chem. 2008;129:799–805. doi: 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hausner SH, Marik J, Gagnon MK, Sutcliffe JL. In vivo positron emission tomography (PET) imaging with an αvβ6 specific peptide radiolabeled using 18F-“click” chemistry: evaluation and comparison with the corresponding 4-[18F]fluorobenzoyl- and 2-[18F]fluoropropionyl-peptides. J Med Chem. 2008;51:5901–4. doi: 10.1021/jm800608s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thonon D, Kech C, Paris J, Lemaire C, Luxen A. New strategy for the preparation of clickable peptides and labeling with 1-(azidomethyl)-4-[18F]-fluorobenzene for PET. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:817–23. doi: 10.1021/bc800544p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wangler C, Schirrmacher R, Bartenstein P, Wangler B. Click-chemistry reactions in radiopharmaceutical chemistry: fast & easy introduction of radiolabels into biomolecules for in vivo imaging. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:1092–116. doi: 10.2174/092986710790820615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hohne A, Mu L, Honer M, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM, Graham K, Stellfeld T, Borkowski S, Berndorff D, Klar U, Voigtmann U, Cyr JE, Friebe M, Dinkelborg L, Srinivasan A. Synthesis, 18F-labeling, and in vitro and in vivo studies of bombesin peptides modified with silicon-based building blocks. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1871–9. doi: 10.1021/bc800157h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mu L, Hohne A, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM, Graham K, Cyr JE, Dinkelborg L, Stellfeld T, Srinivasan A, Voigtmann U, Klar U. Silicon-based building blocks for one-step 18F-radiolabeling of peptides for PET imaging. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:4922–5. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becaud J, Mu L, Karramkam M, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM, Graham K, Stellfeld T, Lehmann L, Borkowski S, Berndorff D, Dinkelborg L, Srinivasan A, Smits R, Koksch B. Direct one-step 18F-labeling of peptides via nucleophilic aromatic substitution. Bioconjug Chem. 2009;20:2254–61. doi: 10.1021/bc900240z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ulrike Roehn JB, Mu Linjing, Srinivasan Ananth, Stellfeld Timo, Fitzner Ansgar, Graham Keith, Dinkelborg Ludger, Schubiger August P, Ametamey Simon M. Nucleophilic ring-opening of activated aziridines: A one-step method for labeling biomolecules with fluorine-18. J Fluorine Chem. 2009;130:902–912. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McBride WJ, Sharkey RM, Karacay H, D’Souza CA, Rossi EA, Laverman P, Chang CH, Boerman OC, Goldenberg DM. A novel method of 18F radiolabeling for PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:991–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.060418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laverman P, McBride WJ, Sharkey RM, Eek A, Joosten L, Oyen WJ, Goldenberg DM, Boerman OC. A novel facile method of labeling octreotide with 18F-fluorine. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:454–61. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.066902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dolle F. Fluorine-18-labelled fluoropyridines: advances in radiopharmaceutical design. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:3221–35. doi: 10.2174/138161205774424645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kilbourn MR, Haka MS. Synthesis of [18F] GBR13119, a presynaptic dopamine uptake antagonist. Int J Rad Appl Instrum A. 1988;39:279–82. doi: 10.1016/0883-2889(88)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mishani E, Cristel ME, Dence CS, McCarthy TJ, Welch MJ. Application of a novel phenylpiperazine formation reaction to the radiosynthesis of a model fluorine-18-labeled radiopharmaceutical (18FTFMPP) Nucl Med Biol. 1997;24:269–73. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(97)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berridge MS, Tewson TJ. Chemistry of fluorine-18 radiopharmaceuticals. Int J Rad Appl Instrum A. 1986;37:685–93. doi: 10.1016/0883-2889(86)90262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiesewetter DO, Jagoda EM, Kao CH, Ma Y, Ravasi L, Shimoji K, Szajek LP, Eckelman WC. Fluoro-, bromo-, and iodopaclitaxel derivatives: synthesis and biological evaluation. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:11–24. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00351-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X. Multimodality imaging of tumor integrin αvβ3 expression. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2006;6:227–34. doi: 10.2174/138955706775475975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Z, Liu S, Wang F, Chen X. Noninvasive imaging of tumor integrin expression using 18F-labeled RGD dimer peptide with PEG4 linkers. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:1296–307. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu S, Liu Z, Chen K, Yan Y, Watzlowik P, Wester HJ, Chin FT, Chen X. 18F-Labeled galacto and PEGylated RGD dimers for PET imaging of αvβ3 integrin expression. Mol Imaging Biol. 2010;12:530–8. doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0284-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X, Tohme M, Park R, Hou Y, Bading JR, Conti PS. Micro-PET imaging of αvβ3-integrin expression with 18F-labeled dimeric RGD peptide. Mol Imaging. 2004;3:96–104. doi: 10.1162/15353500200404109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]