Main Text

Roderick R. McInnes

Fellow geneticists and genomicists from around the world, I welcome you to the 60th annual meeting of the American Society of Human Genetics. I wish to thank you for the privilege of being the President of this increasingly important, international, and multicultural society during the past year.

The subject of my address, “Culture: The Silent Language Geneticists Must Learn,” occurred to me when I recently discovered a reprint of a favorite book, The Silent Language, by Edward T. Hall, first published in 1959.1 The silent language referred to in the title is culture. He wrote that “…cultural patterns are literally unique, and therefore they are not universal … Consequently, difficulties in intercultural communication are seldom seen for what they are.” As geneticists and genomicists have reached out to study the world's populations, particularly indigenous populations, the opportunities for cultural misunderstanding have grown. In some instances, remarkable progress has been made, both in doing research with indigenous communities and doing it in ways welcomed by them. In others, the cultural perspective of the researchers, and their more powerful cultural position in society, has prevented them from fully considering the priorities of the study population, well-intended research could not be undertaken or completed, and the population under study has been left with a sense of mistrust, stigmatization, or weakened political authority.2,3 Rebecca Tsosie has used the term “cultural harm” to refer to the negative impact, for Native Americans, of many of their experiences with genetics researchers,4 and examples of such unwanted outcomes were reported in AJHG in 1998.5 Consequently, Hall's observation about the potential for difficulties in intercultural communications is becoming increasingly relevant to indigenous communities around the world and to research studies with these communities by members of the American Society of Human Genetics.

Culture: What You First See Isn't What You Get

The subtlety of cultural differences is well illustrated by a European tourist visiting North America for the first time. On touring the continent, she might gain the impression that Canada and the United States have nearly identical cultures—the buildings look much the same, people dress similarly, talk the same language, have the same stores, and so on. To a tourist, Toronto and Chicago might seem to belong to a single quite homogeneous culture. But underneath this veneer of cultural similarity, there are very significant differences. Two tongue-in-cheek examples refer to some of these distinctions. One example is a statement by the wonderful Canadian novelist Margaret Atwood: “When Americans win things such as Miss America crowns, Oscars, murder trial verdicts, and literary prizes, they weep and thank people. When Canadians are awarded things, they look behind them to see if it was meant for somebody else.” A second joke alludes to other Canadian-American cultural differences. “Question: What's the definition of a Canadian? Answer: “An unarmed North American with health insurance.”

A geneticist's first impression of an indigenous culture is similar to viewing an iceberg: what you see isn't what you get. The obvious differences—the visible one-seventh of the iceberg above the water, are only a small fraction of all the distinct features of the indigenous culture. These surface features poorly represent the larger substratum of profound differences hidden beneath the surface.

The Perspectives and Concerns of Indigenous Populations

My first goal today is to increase your awareness of the perspectives and concerns of indigenous populations regarding genetic research. I use the word “populations” because there is often remarkable uniformity amongst indigenous populations from around the world, with respect to the issues I will discuss.6,7 Perhaps the predominant reality for indigenous populations, with respect to research, is the fact that we, geneticists from western-oriented cultures, are from the dominant culture. We have greater economic, political, and scientific knowledge. This fact generally permeates almost all interactions between researchers and indigenous populations. As exemplified by the experience of Mohatt and his colleagues in conducting research on sobriety with Alaskan natives, the researcher must be aware of the “power differential between those who traditionally control the research and those who are the researched” and must avoid unconsciously sending the “… message that the researcher, as someone holding specialized knowledge and language, could tell the community what was right, thereby denigrating their experience.”8 The power differential may be unwittingly and unfavorably tilted against the representatives of the indigenous culture before even a word has been spoken.

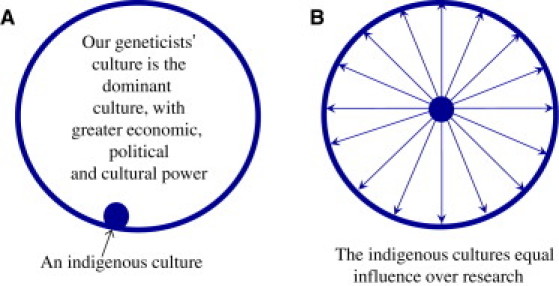

My second goal is to present examples of both successful and unsuccessful research studies of indigenous populations and to consider why some succeeded and others failed. Third, I will emphasize that the culture, priorities, values, and jurisdiction of the indigenous community must be respected and that, in successful studies, they have been. The take-home message is that we must do “culturally competent”9–11 research, research that respects the indigenous community's beliefs, their desire for self-determination, their desire to benefit from the research, and their wish to retain intellectual property rights and ownership of samples of DNA, tissues, and body fluids. One can visualize the ideal dynamic between researchers and indigenous communities schematically: imagine that a large circle is us, the dominant culture, and that the indigenous community is a very much smaller circle within or partially within our larger culture (Figure 1). The equality of the reach and influence of the indigenous population over the whole research project can be represented by the arrows radiating out from the small central circle of the indigenous community, to the perimeter of the large circle.

Figure 1.

The Relationship between the Dominant Western Culture and an Indigenous Population

(A) The view of our culture from the perspective of an indigenous culture.

(B) The ideal equality of an indigenous culture's influence over research is represented by the arrows reaching to the full perimeter of the dominant culture's circle of influence.

At this point, I would like to issue a caution: as Bartha Knoppers has pointed out, in reviewing earlier genetic studies of indigenous populations, we have to be very hesitant to judge the conduct of previous research—and previous researchers—by today's standards.12 Standards change rapidly, and in this area, they've changed greatly in the last 10 years. Another potential misjudgement, I believe, is that the indigenous community is anti-science. This is not the case, and I think I will be able to convince you of that. To paraphrase Debra Harry, the indigenous community is not so much anti-science as “pro-indigenous rights.”13

When Genetics and Genomic Research Studies of Indigenous Populations Have Led to Controversy

One of the first unfortunate interactions between geneticists and an indigenous population occurred in Canada and involved the Nuu-chah-nulth, a tribe whose people live on the west coast of Vancouver Island in British Columbia.14,15 The Nuu-chah-nulth have a high frequency of rheumatoid arthritis. In the early 1980s, Dr. R. H. Ward, at that time at the University of British Columbia, approached the tribal leaders about undertaking a search for HLA alleles that might be linked to the arthritis in this tribe. A study of 900 participants failed to demonstrate linkage. These studies were conducted according to the ethical guidelines of the time. For example, both the leaders of the community and every individual who was involved offered their informed consent. The problems arose later. Between 1985 and up to 2000, the DNA was moved to other research centres without the knowledge or consent of the tribe and was used for research that hadn't been authorized in the original agreement between Dr. Ward and the tribe. Such misuse of DNA samples for studies outside the original research question has been a recurrent problem for indigenous populations.16,17 The affair was drawn to the attention of the scientific community about 8 years ago in a commentary in Nature entitled, “Tribe blasts ‘exploitation’ of blood samples.”14 Of particular concern to the Nuu-chah-nulth was the use of the samples for genetic ancestry studies, an area of genetic research that is particularly challenging to Native Americans for a variety of culturally specific reasons.17–19

The DNA was not returned to the Nuu-chah-nulth until 20 years after sampling. The perception of researchers that DNA collected for research becomes their property is actually a common problem: once the DNA is taken, if the indigenous community wants to change the rules of the game, it can be very difficult for them to recover the samples. (The experience of the Yanomamö Indians in Brazil and Venezuela illustrates the same problem,20 but it must be noted here that allegations of misconduct against the prominent human geneticist James V. Neel, for his research on the Yanomamö, have been shown to be false). 21 Regrettably, the outcome for the Nuu-chah-nulth was a sense of betrayal and a loss of trust in researchers. But the tribe responded to this sense of mistrust with action. The elected chief formed a committee to establish conditions to be followed by researchers who wished to carry out research with their community. Subsequently, the Nuu-chah-nulth made important contributions to the development of the Canadian guidelines on research with indigenous populations,10 which I will discuss later.

A second illustration of the conflicts that can develop between indigenous populations and genetic researchers may be more familiar because it has recently been reported in the scientific literature.11,22 In this instance, the tribe involved was the Havasupai of Arizona, and the controversy was highlighted in a News Feature in Nature in 2004, entitled: “When two tribes go to war: Medical geneticists and isolated Native American communities afflicted by inherited diseases should have much to gain from working together. But the relationship can go sour …”12. Geneticists are one of the “tribes” referred to in the title of this commentary. In this instance, the tribe approached the University of Arizona in the early 1990s to obtain insight into the very high incidence of type 2 diabetes in the Havasupai. A search for linkage to HLA loci, particularly to HLA-A2, which had been shown to be associated with type 2 diabetes in Pima Indians, was conducted, but no linkage was found. Subsequently, a freezer failure was thought to have made the DNA samples useless. But in 2000 the development of microsatellite markers made it possible to examine genetic variability in the Havasupai, despite the poor quality of the DNA. The tribe soon learned of these studies, which they had not authorized, and to which they objected.

The subsequent events were contentious and unfortunate. The News Feature in Nature makes instructive reading for any geneticist who plans to conduct research with indigenous populations.12 All of the outcomes were bad. No insight was gained into the high incidence of diabetes, despite the fact that it occurs in a little more than a third of men and about half of the women in this population—one of the highest incidences in the world. Secondly, the tribe felt stigmatized. At least one study of genetic variability in the Havasupai was published and documented a high degree of consanguinity,23 which is hardly surprising because in the early 20th century, the tribe had been reduced to only 40 men and 40 women of reproductive age—a narrow genetic bottleneck. However, the tribe felt stigmatized by the identification of the high level of consanguinity, revealed by studies they had not authorized. Tremendous negative press was generated for the University of Arizona and for the investigators. I'm sure this experience was traumatic and detoured their academic careers.

The Genographic Project (see Web Resources) is another large-scale genomics project which has very much been in the news since its launch in 2005. Sponsored by the National Geographic Society and IBM, this initiative attracted negative press very quickly. The headline of an article in the New York Times on this project read “DNA Gatherers Hit Snag: Tribes Don't Trust Them.” What are the issues in this instance? If you visit the website of the Genographic Project, it looks very impressive. The aim, presented there, is “to analyze historical patterns in DNA from participants around the word, to understand human genetic roots.” A major research component—there are several—is “to obtain field research data in collaboration with indigenous and traditional peoples.” The website states that the project is to be “anonymous, non-medical, non-profit, and that the data are in the public domain.” There have been good scientific outcomes from this project. One publication arising from the project, and presented on the website, reported efforts “… to identify … male genetic traces [of the Phoenecians] in modern populations around the Mediterranean.” The work was published in The American Journal of Human Genetics in 2008.24 Another paper from the Genographic Project reported a novel deletion, in healthy individuals, of a region of the mitochondrial DNA molecule that had previously been thought to control replication of the molecule.25 This discovery, in homoplasmic individuals in one family, challenges the idea that this is a replication control region. These two publications demonstrate that good things can arise from the Genographic Project.

Given these useful outcomes of the Genographic Project, what concerns do indigenous populations have about it? In fact, the issues are quite different from the ones that have arisen from studies of particular diseases in individual tribes. For example, with respect to the statement that this is a non-profit enterprise, critics have wondered about “secondary” profit. This problem has been thoughtfully considered by Jenny Reardon, who wrote “… as the project's FAQ web page (see Web Resources) explains, ”‘Family Tree DNA [a genetic ancestry company] does have access to some of the DNA and data to assist in the analytical research.” But “… will access to these data enable Family Tree DNA to develop a new generation of ancestry tests that they can then sell?” I think this is a fair question. Reardon then asks “Who will profit economically from the films made about the Genographic Project [by the National Geographic Society]?” A second more common concern about ancestry studies in indigenous populations, such as The Genographic Project, has been expressed well by Pullman and Arbour: “[The findings of the Genographic Project could] undermine cultural narratives about a people's origins that have been held for generations or centuries and could alter perceptions of who's in and who's out of particular cultural groups.”15 A nuanced commentary on this problem has been written by Kim TallBear, a social scientist at the University of California-Berkeley and a Dakota. She wrote that, “Indigenous [peoples'] ways of understanding their origins … [are] based in particular histories, cultures, and landscapes. [The Genographic Project] is not going to tell me how I am related to my various Dakota tribal kin, the ultimate set of relations in tribal life. Nor can [The Genographic Project] tell me how we got here today, although it could tell me that I have the founding “Native American” lineage dubbed “haplogroup A.” The question of how we as Dakota got to where we are has already been answered, and the answer is not one of genetics”.18

You might ask whether this perspective of Native Americans, as expressed by Kim TallBear, is inconsistent with cultural beliefs held by members of the dominant culture, including most geneticists at this meeting. On the very day that I was re-reading TallBear's paper18 in preparation for this talk, an article entitled “Parentage is about more than DNA” appeared in a Canadian newspaper, The Globe and Mail.26 The article begins “A woman born of a genetic sperm donation is challenging the law that prevents her from knowing her genetic father's identity.” (Let's agree to ignore the fact that one can't conceive of a “nongenetic” sperm donation!). The authors write, in what I think is a very powerful statement, that “the rhetoric of genetic connection risks erasing social bonds between parents and children. It implies that identity results from genetics. And the idea that genetic origin makes people who they are devalues the diverse means by which people form families.” Similarly, one could summarize the concepts expressed above by Kim TallBear as “Ancestry is about more than DNA.” As you can see, there's really little difference between our culture's perspective on this issue of personal identity and the perspective of indigenous populations on their tribal identity.

One of the recurrent complaints of indigenous people about research is that it benefits the researchers and not the population being studied. An Alaskan Native saying perfectly captures the resentment bred of experiences like those of the Nuu-chah-nulth and the Havasupai: “Researchers are like mosquitoes; they suck your blood and leave.”11

The great disconnect here is between our culture of research and the “participatory research” approach we must adopt for studies with indigenous populations, an approach that has now been advocated by many social scientists and geneticists.8,11,27–31 As pointed out to me by Laura Abour of the University of British Columbia, our investigator-driven biomedical research model is science focused, the goal being to add to the body of knowledge and hopefully help battle disease. In our model, the subjects have little voice in the research process, they waive rights of benefit sharing in general, the data and samples are “owned” by the researcher, and the results go to journals and are not specifically ever directed back to or shared with the research subjects.

When Genetics and Genomic Research Studies of Indigenous Populations Have Been Successful, and Why

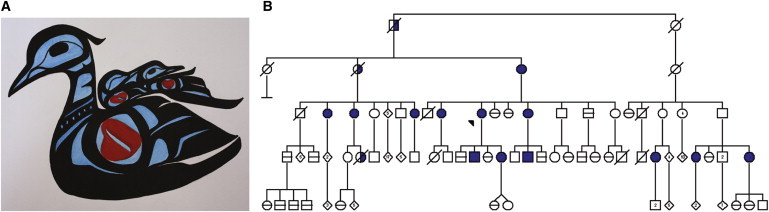

Many Canadian researchers realized that our “investigator-driven” paradigm had to be changed for studies with indigenous populations. The outcome was the Guidelines for Health Research Involving Aboriginal People developed by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.10 The community-based participatory approach outlined in these guidelines, and that all of us would be well advised to use, is exemplified by a study undertaken by Laura Arbour and her colleagues in northern British Columbia with the Gitxsan people.32 In the Gitxsan community, the long-QT syndrome and sudden death are very prevalent and therefore a major health priority. Community members brought this problem to the attention of university researchers. To provide advice and govern the research, the Gitxsan Health Society formed a local research advisory committee consisting of lay community members and medical personnel. Laura's studies showed that up to ∼1/100 individuals carry a Val205Met mutation in the KCNQ1 gene, which encodes one of the ion channels associated with this disease (Figure 2). This prevalence is about 50-fold greater than that found in the general population, where it affects about 1/5000 individuals.

Figure 2.

Long QT Syndrome in the Gitxsan Tribe of Northern British Columbia

(A) The painting “Loon Representing Family Unit,” by the Gitxsan artist Virginia Morgan, depicts the mother loon with LQTS by a break in her heart, as well as in the heart of one of her two baby loons, who has inherited LQTS. The image represents the autosomal-dominant nature of the condition.

(B) A simplified family pedigree of one index case family of Gitxsan, representing one of three kindreds from the same community with the V205M mutation in the KCNQ1 gene. The index case is indicated by an arrowhead. The presence of a V205M mutation confirmed by genotyping is designated by the filled symbols, and its absence by a horizontal line through the symbol. Unexplained death is designated with half-filled symbols with an oblique line designating death. Up to 1/100 Gitxsan individuals may carry the V205M mutation in the KCNQ1 gene (image reprinted with permission from Genetics in Medicine and originally published in Arbour et al.32).

The features of the Gitxsan long-QT syndrome research that were characteristic of participatory research were that the Gitxsan initiated the research, participated in the development of the research protocol, and maintained an on-going advisory and governance role. In addition, there were tribal research assistants, the community reviewed the results with the investigators, reviewed the paper before it was submitted for publication, and agreed with the decision to use their tribal name in the publication. This successful application of participatory research is not unique. For example, the late Gerry Mohatt initiated an admirable series of investigations with Alaskan Natives, including “culturally anchored participatory action research on sobriety in Alaskan Natives.”8 Some of the key features here were the same as those employed with the Gitxsan, including, for example, the facts that Alaska Natives became coresearchers and were part of the coordinating council for the study. Particularly instructive in the report of this research was the description of the gradual realization by the researchers that their initial communications with the native community were ineffective because they were not “communicatively competent.” “Many Alaskan Natives … perceived the [initial] discourse as dominated by one-way communication … that communicated [only] the perspectives and values of the alcohol research community” and not that of the native population”8.

There are other successful examples of long-term relationships between investigators and Native American and aboriginal Canadians. One of the most productive has been directed elucidating the causes of type 2 diabetes in the Gila River community of Pima Indians in Arizona for over 25 years.33 In comparison to a typical American city, this tribe has an almost 20-fold increased incidence of T2D.34 Of course, their interest in this research originally arose from the effects of the disease on their community.

An example of a population genomic study that appears to have avoided many of the missteps of its predecessors is the determination of the complete Khoisan (South African bushman) and Bantu genomes from southern Africa.35 In this case, the complete genome sequence of one bushman and one Bantu, and the exome sequences of three other bushman, were obtained. The results were remarkable, and this paper is a fascinating read. For example, 13,146 novel amino acid SNPs were identified, contributing many new candidate functional sites to SNP databases for future whole-genome association studies. Moreover, these variants will facilitate studies of correlations between genome data and family and medical histories, thereby potentially benefitting the larger Bantu and Khoisan populations. As outlined in the article in Nature, the researchers carefully addressed ethical issues, particularly the consent process, associated with a study of this type. Informative interviews with Dr. Stephan Schuster about this research can be seen on YouTube.36,37 Despite the researchers' efforts, a critical commentary in Nature followed, stating “… the terms Khoisan, Bantu, and Bushman are perceived by those populations as outdated and even derogatory”.38 However, the authors appear to have more than justified their use of “Khoisan, Bantu, and Bushman” in their response to the author of this commentary: “The Namibian [referring to the country where most Bushman live] hunter-gatherer participants chose the name ‘Bossiesman’ (Afrikaans for ‘bushmen’) as their group identifier and expressed pride in the affiliation, stressing that the negative connotation is almost obsolete. Archbishop Tutu has declared himself proud to be Bantu and Bushmen since becoming aware of his Bushmen ancestry through our study.”38

Earlier, I referred to the Guidelines for Health Research Involving Aboriginal People published by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR),10 developed by a team led by Dr. Doris Cook of the Akwesasne Mohawk Nation that crosses the Canadian-US border. CIHR is the Canadian equivalent of the NIH. You may be surprised to learn that one of its 13 Institutes is the Institute of Aboriginal People's Health (IAPH). The establishment of this institute, in 2000, is making a huge impact on support for research, and the conduct of it, in aboriginal communities in Canada. The first scientific director of the IAPH was Jeff Reading, a Mohawk Indian who works at the University of Victoria. Notably, on the CIHR website, there are translations of the guidelines in Inuktitut, one of the Inuit languages.

I believe the guidelines are worth your inspection. The first article of the guidelines refers to cultural respect and jurisdiction. “A researcher should understand and respect Aboriginal world views, including responsibilities to the people and culture that flow from being granted access to traditional or sacred knowledge. These should be incorporated into research agreements, to the extent possible.” Second, “A community's jurisdiction over the conduct of research should be understood and respected.” Many of the aboriginal communities in Canada have review boards to examine ethical issues and consents. The third article addresses the importance of participatory research that I have already mentioned: “Communities should be given the option of a participatory-research approach. Genuine research collaboration is developed between researchers and Aboriginal communities when it promotes partnership within a framework of mutual trust and cooperation.”

Article 13 states that “Biological samples should be considered ‘on loan’ to the researcher unless otherwise specified in the research agreement.”10 This article addresses the fact that genetics researchers must recognize how indigenous cultures, particularly North American indigenous populations, regard biological materials. The point was expressed beautifully by Frank Dukapoo, a Hopi Indian and American geneticist who recently died: “To us, any part of us is sacred. Scientists say it's just DNA. For an Indian, it's not just DNA … it is part of the essence of a person.”39 Therefore, all blood and tissues accepted for research in aboriginal communities (in Canada) must be considered the continued property of the donor or community involved. The guiding principle is that the DNA is “on loan” to the researcher and is to be returned if requested.29 All decisions about any secondary use other than the original goal has to be first confirmed with the community.

Article 14, which speaks to the issue of pre-submission community review, is also important: “An Aboriginal community should have an opportunity to participate in the interpretation of data and the review of conclusions drawn from the research to ensure accuracy and cultural sensitivity of interpretation [before submission for publication]. This should not be construed as the right to block the publication of legitimate findings; rather, it refers to the community's opportunity to contextualize the findings and correct any cultural inaccuracies.”10

Indigenous communities, like any other, would obviously like to benefit from research when possible. But if their historical view is that researchers are like mosquitoes who fly in, take blood, and then fly out, you can understand why they might be particularly sensitive to the issue of benefits to their community. Some of the major issues in this regard are referred to in Articles 8–10:10

-

•

Article 8: Community and individual concerns over, and claims to, intellectual property should be explicitly addressed in the negotiation.

-

•

Article 9: Research should be of benefit to the community as well as the researcher. (Author's note: Of course this is the reason why indigenous communities are more willing to participate in research related to diseases of significance to them, rather than, say, genomic studies of populations.)

-

•

Article 10: A researcher should support education and training of Aboriginal people in the community, including training in research methods and ethics.

This explicit articulation of the desire of indigenous communities to benefit from studies of their genes and genomes is not different from the desires of other communities asked to participate in comparable research projects. Consider, for example, the Estonian Genome Project (EGP; see Web Resources), which began almost 10 years ago. The overarching goal of the EGP is to collect one million Estonians into a single health and genetic database. Some of the anticipated benefits are better healthcare, better healthcare delivery, development of gene technology, medical-sector infrastructure, and economic benefits (including jobs, investments, and education). Although not all has been smooth sailing,40 the aspirations for the EGP expressed by the people of Estonia are little different from the expectations from research that aboriginal Canadians have expressed in the CIHR Guidelines. In other words, why should indigenous populations expect less?

I believe that the CIHR Guidelines are an excellent template for all studies with indigenous populations around the world. Of course, the cultures of indigenous populations around the world are hardly uniform. Even tribes within the same region of British Columbia do not necessarily have identical cultural perspectives. With respect to the possibility that these Canadian guidelines might be adopted widely around the world, Margaret Atwood again had something to say: “Canadians have the greatest freedom of speech in the world: we can say anything we want, because no one is listening.” But I hope, in this instance, that isn't the case!

While reading the literature on genetic research with indigenous populations, I wondered whether the “best practice” principles that have been developed by many researchers, ethicists, and social scientists over the past 10–15 years to facilitate research with indigenous communities are relevant to research with other non-Western cultures. I contacted Jeff Murray at the University of Iowa, who spent months in rural parts of the Philippines where there is a very high frequency of cleft lip and palate. He was trying to identify genetic variants that confer the increased risk of cleft lip and palate in these populations. His studies demonstrated that one allele, which changes valine 274 to isoleucine in interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6), was responsible for 12% of the genetic contribution to these malformations in this and other populations.41 When I contacted Jeff, I didn't refer to issues related to genetic research with indigenous populations; I didn't tell him about the CIHR Guidelines. I was intent on not biasing his response to my question, “Can you send me a brief summary of issues you regard as critical to establishing and maintaining a long-term research relationship with communities in countries less developed than the ones most genome/genetic scientists come from?”

Three of the principles that Jeff Murray considers central to successful genetic research in developing communities are: (1) while respecting local culture, do not violate basic ethical principles. IRB rules must be followed, and financial inducements (i.e., bribes) are out of the question, but this does not mean that the communities should not expect to benefit from the studies; (2) realize that there may be many local cultures even within one seemingly homogenous group, and act accordingly; (3) make a long-term commitment; you may need (and will want) to return year after year to build trust with the community. (Similarly, Laura Abour and her colleagues participated in discussions with the Gitxsan for years before the actual research on the long-QT syndrome was initiated).

Apart from informing science and clinical care, Jeff argues that genetic research in less developed communities facilitates technology transfer; affords opportunities for education; provides a cultural, social, and political connection to better inform the world about these communities; and serves as a sentinel for related efforts, attracting funding and students and enabling novel studies. It is clear, once again, that these outcomes strongly resemble those that indigenous communities might also expect to obtain from genetic research.

What is the way forward? There is a wonderful examination of this question in an article entitled “Bridging the Divide between Genomic Science and Indigenous Peoples” by researchers at Georgetown University, recently published in the Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics.42 This is an admirable document. One reason I like it in particular, if I may be slightly partisan, is because this article by American researchers recognizes the merits of the CIHR Guidelines for Health Research Involving Aboriginal People. So, with respect to Canadians being heard, Margaret Atwood was wrong!

In preparing this address, I was reminded of the Presidential Address of Hunt Willard in 2001. In his address, he spoke to the major issue confronting the American Society of Human Genetics at that time: our concern that the genomicists, who were becoming numerous and intensely muscular, might break off and form their own separate society. Of course, you all realize what a disaster that would have been for genetic research. At the end of his talk, Hunt challenged the society, saying, “What we must do is bring the genomicists into the ASHG tent.” With respect to genetic research with indigenous populations, I suggest that we must now be invited into the metaphorical tent of the indigenous communities. The multicultural and international nature of The American Society of Human Genetics creates a major opportunity for it to make this happen, to the benefit of all peoples. If we succeed, both genetics and the populations of the world will be the richer.

Acknowledgements

Many fellow researchers from around the world guided me through the literature related to this address. I am deeply indebted to Laura Arbour, Kim TallBear, Wylie Burke, Charmaine Royal, Ed Ramos, Jeff Reading, Jeff Murray, Daryl Pullman, Deborah Bolnick, Michael MacDonald, Emma Kowal, Tim Caulfield, and Lynn Jorde. I also wish to thank Jeff Murray and Stephan Schuster for sharing their experiences in developing their research in the Phillipines and with the Khoisan and Bantu genomes, respectively, and Robin Williamson for the transcription of this address. I also wish to thank Virginia Morgan for the remarkable image of the loons, shown in Figure 2.

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

The Estonian Genome Project, http://www.geenivaramu.ee;

The Genographic Project, https://genographic.nationalgeographic.com/genographic/index.html

References

- 1.Hall E.T. Anchor Books; New York: 1990. The Silent Language. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manson S.M. Barrow alcohol study: Emphasis on its ethical and procedural aspects. Am. Indian Alsk. Native Ment. Health Res. 1989;2:5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dukepoo F.C. It's more than the Human Genome Diversity Project. Politics and the life sciences. The Journal of the Association for Politics and the Life Sciences. 1999;18:293–297. doi: 10.1017/s0730938400021493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsosie R. Cultural challenges to biotechnology: Native American genetic resources and the concept of cultural harm. J. Law Med. Ethics. 2007;35:396–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juengst E.T. Group identity and human diversity: Keeping biology straight from culture. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1998;63:673–677. doi: 10.1086/302032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodson M., Williamson R. Indigenous peoples and the morality of the Human Genome Diversity Project. J. Med. Ethics. 1999;25:204–208. doi: 10.1136/jme.25.2.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mead, A.T.P., and Ratuva, S. (2007). Pacific Genes & Life Patents: Pacific Indigenous Experiences & Analysis of the Commodification & Ownership of Life. (Wellington, New Zealand: United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies and Call of the Earth [Llamado de la Tierra]). http://calloftheearth.wordpress.com/publications/.

- 8.Mohatt G.V., Hazel K.L., Allen J., Stachelrodt M., Hensel C., Fath R. Unheard Alaska: Culturally anchored participatory action research on sobriety with Alaska Natives. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2004;33:263–273. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027011.12346.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster M.W., Sharp R.R. Genetic research and culturally specific risks: One size does not fit all. Trends Genet. 2000;16:93–95. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01895-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2010). CIHR Guidelines for Health Research Involving Aboriginal People. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29134.html.

- 11.Cochran P.A., Marshall C.A., Garcia-Downing C., Kendall E., Cook D., McCubbin L., Gover R.M. Indigenous ways of knowing: Implications for participatory research and community. Am. J. Public Health. 2008;98:22–27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.093641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalton R. When two tribes go to war. Nature. 2004;430:500–502. doi: 10.1038/430500a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reardon J. “Anti-colonial genomic practice?” Learning from the Genographic Project and the Chacmool Conference. Int. J. Cult. Property. 2009;16:205–212. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalton R. Tribe blasts ‘exploitation’ of blood samples. Nature. 2002;420:111. doi: 10.1038/420111a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pullman D., Arbour L. Genetic Research and Culture: Where Does the Offense Lie? In: Young J.O., editor. The ethics of cultural appropriation. Wiley-Blackwell; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. pp. 115–139. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S.S., Bolnick D.A., Duster T., Ossorio P., Tallbear K. Genetics. The illusive gold standard in genetic ancestry testing. Science. 2009;325:38–39. doi: 10.1126/science.1173038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Royal C.D., Novembre J., Fullerton S.M., Goldstein D.B., Long J.C., Bamshad M.J., Clark A.G. Inferring genetic ancestry: Opportunities, challenges, and implications. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86:661–673. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.TallBear K. Narratives of race and indigeneity in the Genographic Project. J. Law Med. Ethics. 2007;35:412–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolnick D.A., Fullwiley D., Duster T., Cooper R.S., Fujimura J.H., Kahn J., Kaufman J.S., Marks J., Morning A., Nelson A. The science and business of genetic ancestry testing. Science. 2007;318:399–400. doi: 10.1126/science.1150098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Couzin-Frankel J. Researchers to return blood samples to the Yanomamö. Nature. 2010;328:1218. doi: 10.1126/science.328.5983.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Society of Human Genetics Response to Allegations against James V. Neel in Darkness in El Dorado, by Patrick Tierney. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:1–10. doi: 10.1086/338147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mello M.M., Wolf L.E. The Havasupai Indian tribe case—Lessons for research involving stored biologic samples. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:204–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1005203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markow T.A., Martin J.F. Inbreeding and developmental stability in a small human population. Ann. Hum. Biol. 1993;20:389–394. doi: 10.1080/03014469300002792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zalloua P.A., Platt D.E., El Sibai M., Khalife J., Makhoul N., Haber M., Xue Y., Izaabel H., Bosch E., Adams S.M. Identifying genetic traces of historical expansions: Phoenician footprints in the Mediterranean. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;83:633–642. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Behar D.M., Blue-Smith J., Soria-Hernanz D.F., Tzur S., Hadid Y., Bormans C., Moen A., Tyler-Smith C., Quintana-Murci L., Wells R.S. A novel 154-bp deletion in the human mitochondrial DNA control region in healthy individuals. Hum. Mutat. 2008;29:1387–1391. doi: 10.1002/humu.20835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell, A., and Leckey, R. (2010). Parentage is about more than DNA. The Globe and Mail. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/opinions/opinion/parentage-is-about-more-than-dna/article1775470/

- 27.Foster M.W., Sharp R.R., Freeman W.L., Chino M., Bernsten D., Carter T.H. The role of community review in evaluating the risks of human genetic variation research. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;64:1719–1727. doi: 10.1086/302415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowekaty M.B., Davis D.S. Cultural issues in genetic research with American Indian and Alaskan Native people. IRB: Ethics and Human Research. 2003;25:12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arbour L., Cook D. DNA on loan: issues to consider when carrying out genetic research with aboriginal families and communities. Community Genet. 2006;9:153–160. doi: 10.1159/000092651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohatt G.V., Plaetke R., Klejka J., Luick B., Lardon C., Bersamin A., Hopkins S., Dondanville M., Herron J., Boyer B. The Center for Alaska Native Health Research Study: A community-based participatory research study of obesity and chronic disease-related protective and risk factors. Int. J. Circumpolar Health. 2007;66:8–18. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v66i1.18219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharp R.R., Foster M.W. Grappling with groups: Protecting collective interests in biomedical research. J. Med. Philos. 2007;32:321–337. doi: 10.1080/03605310701515419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arbour L., Rezazadeh S., Eldstrom J., Weget-Simms G., Rupps R., Dyer Z., Tibbits G., Accili E., Casey B., Kmetic A. A KCNQ1 V205M missense mutation causes a high rate of long QT syndrome in a First Nations community of northern British Columbia: A community-based approach to understanding the impact. Genet. Med. 2008;10:545–550. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e31817c6b19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanson R.L., Millis M.P., Young N.J., Kobes S., Nelson R.G., Knowler W.C., DiStefano J.K. ELMO1 variants and susceptibility to diabetic nephropathy in American Indians. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010;101:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knowler W.C., Bennett P.H., Hamman R.F., Miller M. Diabetes incidence and prevalence in Pima Indians: A 19-fold greater incidence than in Rochester, Minnesota. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1978;108:497–505. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuster S.C., Miller W., Ratan A., Tomsho L.P., Giardine B., Kasson L.R., Harris R.S., Petersen D.C., Zhao F., Qi J. Complete Khoisan and Bantu genomes from southern Africa. Nature. 2010;463:943–947. doi: 10.1038/nature08795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Penn State University. (2010). How was Archbishop Desmond Tutu involved in your research? http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=czHd4wgFEkc.

- 37.Penn State University. (2010). Will there be any benefit to the South African countries who participated in this research? http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=av80ZgFTG1E

- 38.Schlebusch C. Issues raised by use of ethnic-group names in genome study. Nature. 2010;464:487. doi: 10.1038/464487a. author reply, 487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petit, C. (1998). Trying to Study Tribes While Respecting Their Cultures. San Franciso Chronicle. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/1998/02/19/MN61803.DTL

- 40.Kattel R., Suurna M. The Rise and Fall of the Estonian Genome Project. Studies in Ethics, Law, and Technology. 2008;2 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zucchero T.M., Cooper M.E., Maher B.S., Daack-Hirsch S., Nepomuceno B., Ribeiro L., Caprau D., Christensen K., Suzuki Y., Machida J. Interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6) gene variants and the risk of isolated cleft lip or palate. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351:769–780. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobs B., Roffenbender J., Collmann J., Cherry K., Bitsoi L.L., Bassett K., Evans C.H., Jr. Bridging the divide between genomic science and indigenous peoples. J. Law Med. Ethics. 2010;38:684–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2010.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]