Abstract

We conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) and a follow-up study of bipolar disorder (BD), a common neuropsychiatric disorder. In the GWAS, we investigated 499,494 autosomal and 12,484 X-chromosomal SNPs in 682 patients with BD and in 1300 controls. In the first follow-up step, we tested the most significant 48 SNPs in 1729 patients with BD and in 2313 controls. Eight SNPs showed nominally significant association with BD and were introduced to a meta-analysis of the GWAS and the first follow-up samples. Genetic variation in the neurocan gene (NCAN) showed genome-wide significant association with BD in 2411 patients and 3613 controls (rs1064395, p = 3.02 × 10−8; odds ratio = 1.31). In a second follow-up step, we replicated this finding in independent samples of BD, totaling 6030 patients and 31,749 controls (p = 2.74 × 10−4; odds ratio = 1.12). The combined analysis of all study samples yielded a p value of 2.14 × 10−9 (odds ratio = 1.17). Our results provide evidence that rs1064395 is a common risk factor for BD. NCAN encodes neurocan, an extracellular matrix glycoprotein, which is thought to be involved in cell adhesion and migration. We found that expression in mice is localized within cortical and hippocampal areas. These areas are involved in cognition and emotion regulation and have previously been implicated in BD by neuropsychological, neuroimaging, and postmortem studies.

Main Text

Bipolar disorder (BD [MIM 125480]) is a highly heritable disorder of mood, characterized by recurrent episodes of mania and depression that are often accompanied by behavioral and cognitive disturbances. Linkage and candidate-gene studies were the only available approaches for unraveling the genetic underpinnings of the disorder until the recent introduction of genome-wide association studies (GWAS). To date, six GWAS using common SNPs have been published.1–6 Although there has been only limited consistency across studies regarding the top associated genomic regions,1–3,5,6 meta-analyses of some of these studies have revealed common association signals: a meta-analysis7 of the Baum et al.2 and Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium (WTCCC)1 data sets found evidence of a consistent association between BD and variants in the genes JAM3 (MIM 606871) (rs10791345, p = 1 × 10−6) and SLC39A3 (MIM 612168) (rs4806874, p = 5 × 10−6). A combined analysis4 of the Sklar et al.3 and WTCCC1 studies, which included a total of 4387 patients and 6209 controls, identified a genome-wide significant association signal for BD in ANK3 (MIM 600465) (rs10994336, p = 9.1 × 10−9). The second strongest finding was for rs1006737 in CACNA1C (MIM 114205) (p = 7 × 10−8). Further independent support for ANK3 rs10994336 has recently been found by Schulze et al.8 in samples from Germany (overlapping with samples used in the present GWAS; see Table S1 available online) and the USA; the same study8 reported evidence for allelic heterogeneity at the ANK3 locus. Although GWAS studies of BD have identified a number of potentially relevant genetic variants, the widely acknowledged formal threshold for genome-wide significance of p = 5 × 10−8 has been surpassed only for variation in ANK3 so far.

In the present study, we performed a GWAS and a two-step follow-up study of clinically well-characterized BD samples from Europe, the USA, and Australia. The GWAS and replication I included only European BD samples and produced genome-wide significant evidence for association in the neurocan gene (NCAN [MIM 600826]) (rs1064395, p = 3.02 × 10−8; odds ratio [OR] = 1.31). We then replicated this finding in large, independent samples from Europe, the USA, and Australia (p = 2.74 × 10−4; OR = 1.12). A combined analysis across all samples, adding up to 8441 patients with BD and 35,362 controls, gave p = 2.14 × 10−9 (OR = 1.17). Further support for an involvement of this gene in BD comes from our observation that Ncan expression in mice is localized within cortical and hippocampal areas. These regions have previously been implicated in BD by neuropsychological, neuroimaging, and postmortem studies.

In the following text, we provide a phenotype description of the samples used in each step of our study (GWAS, replication I, replication II), specifications of the SNP genotyping, and the quality control (QC) measures applied to the raw genotyping data:

The patients included in our GWAS and replication I step received a lifetime diagnosis of BD according to the DSM-IV9 criteria on the basis of a consensus best-estimate procedure10 and structured diagnostic interviews.11,12 Protocols and procedures were approved by the local ethics committees. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and controls. They were recruited from consecutive admissions to psychiatric inpatient units at (1) The Central Institute of Mental Health, Mannheim (n = 1081), (2) Department of Psychiatry, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznan, Poland (n = 446), (3) Alexandru Obregia Clinical Psychiatric Hospital, Bucharest, Romania (n = 237), (4) Civil Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga, Spain (n = 298), (5) Russian State Medical University, Moscow (n = 329), and (6) Kosevo Hospital, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina (n = 125). All controls of replication I were also recruited by the abovementioned institutions. All GWAS controls were drawn from three population-based epidemiological studies: (1) PopGen13 (n = 490), (2) KORA14 (n = 488), and (3) the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study (Risk Factors, Evaluation of Coronary Calcification, and Lifestyle) (HNR,15 n = 383). Ancestry was assigned to patients and controls on the basis of self-reported ancestry. More detailed sample descriptions are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Data for Patients with Bipolar Disorder and Controls Following Quality Control

| Sample | Ancestry | N Patients | N Controls | BD1 (%) | BD2 (%) | SAB (%) | BD-NOS (%) | MaD (%) | Diagnosis | Interview | Controls Screened? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS | |||||||||||

| Germany I | German | 682 | 1300 | 679 (99.56) | 2 (0.29) | 1 (0.15) | 0 | 0 | DSM-IV | SADS-L, SCID | no |

| Replication I | |||||||||||

| Germany II | German | 361 | 755 | 138 (38.23) | 93 (25.76) | 130 (36.01) | 0 | 0 | DSM-IV | SADS-L, SCID | no |

| Poland | Polish | 411 | 504 | 323 (78.59) | 88 (21.41) | 0 | 0 | 0 | DSM-IV | SCID | no |

| Spain | Spanish | 297 | 391 | 290 (97.64) | 7 (2.36) | 0 | 0 | 0 | DSM-IV | SADS-L | no |

| Russia | Russian | 326 | 329 | 324 (96.38) | 2 (0.61) | 0 | 0 | 0 | DSM-IV | SCID | no |

| Romania | Romanian | 227 | 221 | 227 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | DSM-IV | SCID | yes |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina / Serbia | Bosnian / Serbian | 107 | 113 | 107 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | DSM-IV | SCID | no |

| Total | 2411 | 3613 | 2088 | 192 | 131 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Replication II | |||||||||||

| GAIN-EA / TGEN1 | European | 2189 | 1434 | 2062 (94.20) | 0 | 127 (5.80) | 0 | 0 | DSM-III, DSM-IV, RDC |

DIGS | yes |

| WTCCC-BD / Exp. Ref. Grp. | British | 1868 | 14,311 | 1594 (85.33) | 134 (7.17) | 98 (5.25) | 38 (2.03) | 4 (0.21) | RDC | SCAN | no |

| Germany III | German | 497 | 857 | 376 (75.65) | 88 (17.71) | 2 (0.04) | 31 (6.24) | 0 | DSM-IV | AMDP, CID-S, SADS-L, SCID | yes |

| France | French | 471 | 1758 | 360 (76.43) | 99 (21.02) | 0 | 12 (2.55) | 0 | DSM-IV | DIGS | no |

| Iceland | Icelandic | 422 | 11,487 | 323 (76.54) | 72 (17.06) | 0 | 27 (6.40) | 0 | DSM-III, DSM-IV, ICD10, RDC |

CID-I, SADS-L | no |

| Australia | European | 380 | 1530 | 291 (76.58) | 87 (22.89) | 1 (0.26) | 1 (0.26) | 0 | DSM-IV | DIGS, FIGS, SCID | no |

| Norway | Norwegian | 203 | 372 | 128 (63.05) | 65 (32.02) | 0 | 10 (4.93) | 0 | DSM-IV | SCID, PRIME-MD | yes |

| Total | 6030 | 31,749 | 5134 | 545 | 228 | 119 | 4 | ||||

| Grand Total | 8441 | 35,362 | 7222 | 737 | 359 | 119 | 4 | ||||

Patients received diagnoses according to the indicated diagnostic criteria and interviews. Protocols and procedures were approved by the local Ethics Committees. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and controls. Ancestry was assigned to patients and controls on the basis of self-reported ancestry. The samples from Bosnia and Herzegovina / Serbia were merged due to the small number of subjects. The Expanded Reference Group for the WTCCC-BD sample comprised the 1958 British Birth Cohort controls, the UK Blood Services controls supplemented by the other 6 disease sets (coronary artery disease, Crohn's disease, hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 and type 2 diabetes) as defined by the WTCCC (2007).1

The following abbreviations are used: AMDP, Association for Methodology and Documentation in Psychiatry;31 BD1, bipolar disorder type 1; BD2, bipolar disorder type 2; BD-NOS, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified; CID-I, Composite International Diagnostic Interview;32,33 CID-S, Composite International Diagnostic Screener;34 DIGS, Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies;35 DSM-III / DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders;9 Exp. Ref. Grp., Expanded Reference Group (11,373 controls);1 FIGS, Family Interview for Genetic Studies;36 GAIN-EA, BD sample with European ancestry from the Genetic Association Information Network (1001 patients and 1033 controls);6 ICD10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems;37 MaD, Manic disorder according to RDC; N, number of subjects; PRIME-MD, Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders;38 RDC, Research Diagnostic Criteria;39 SAB, schizoaffective disorder (bipolar type); SADS-L, Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia;40 SCAN, Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry;41 SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM disorders;11 TGEN1, Translational Genomics Research Institute (genotyping wave 1 with 1190 patients and 401 controls).

Lymphocyte DNA was isolated from ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid anticoagulated venous blood by a salting-out procedure using saturated sodium chloride solution16 or by a Chemagic Magnetic Separation Module I (Chemagen, Baesweiler, Germany). Genotyping was performed on HumanHap550v3 BeadArrays (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). QC was performed with PLINK17 (version 1.05). In detail, the X-chromosomal heterozygosity rates were used to determine the sex of each subject; subjects with a discrepant sex status were excluded (five patients and three controls). Subjects with a call rate (CR) < 0.97 were also excluded (eight patients and 26 controls). Using identical-by-state (IBS) analysis, cryptically related individuals (IBS > 1.65) were identified, and the DNA sample with the lower CR was removed. For the identification of possible population stratification, a multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis was performed. In total, seven patients and 32 controls were excluded on the basis of relatedness or outlier detection. SNPs with a CR < 0.98 and monomorphic SNPs were excluded (18,618 SNPs in patients and 14,880 in controls). Additional markers were excluded on the basis of nonrandom differences in missingness patterns with respect to phenotype and for significant results in the “pseudo” patient-control analysis using control samples and a Cochran-Armitage test for linear trend (TREND) (a total of 7101 SNPs in patients and 8076 in controls). SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) < 1% in patients or controls were excluded (11,434 in patients and 12,155 in controls), as were SNPs in Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium (Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium [HWE], pexact < 1 × 10−4, 351 SNPs in controls; pexact < 1 × 10−6, 132 SNPs in patients). With the use of the remaining patients and controls, a MDS analysis was performed, first with patients and controls from our GWAS sample and then with the GWAS sample and unrelated individuals from the CEU (Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe), CHB (Han Chinese in Beijing, China), JPT (Japanese in Tokyo, Japan), and YRI (Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria) HapMap panels. On the basis of this analysis, seven controls and zero patients were excluded (Figure S2). At the marker level, nonrandom missingness patterns were identified with the use of PLINK's “mishap” test, and another 1825 SNPs were excluded. In total, we excluded 20 patients and 68 controls as well as 49,488 SNPs in the course of our QC before association analysis. The effect of our QC on the resulting p values with data sets has been depicted in a quantile-quantile plot (Figure S1). The genomic inflation factor (λ) after QC was 1.071 (1.107 before QC).

The follow-up SNP set (replication I) was genotyped on the MALDI TOF-based MassARRAY system with the use of the iPLEX Gold assay (Sequenom, San Diego, CA, USA). The iPLEX primer sequences and assay conditions may be obtained from the authors upon request. Of the top 79 SNPs from the GWAS, 18 were excluded from the follow-up step on the basis of linkage disequilibrium (LD), failed assay design, or poor genotype clustering in the iPLEX genotyping assay. Of the remaining 61 SNPs, 13 did not pass our QC filters (six SNPs with CR < 0.95, two SNPs with nonrandom differences in missingness patterns between subsamples, one SNP with an MAF < 0.01 in controls, and four SNPs with deviations from HWE [pexact < 1 × 10−4 in controls]). In total, 181 individuals were excluded (n = 31 cryptically related individuals, n = 150 with call rates < 95%). To identify the cryptically related individuals (IBS > 1.65), we had computed an IBS matrix on the basis of the quality-controlled GWAS sample and all six replication samples.

For the replication II step, NCAN rs1064395 genotypes were extracted from the following genome-wide data sets: GAIN-EA6/TGEN1, WTCCC-BD,1 Germany III, France, Iceland, Australia, and Norway, which are described in Table 1 and Table S2.

The quality-controlled genotype data were subjected to the following association tests: In the GWAS and replication I steps, analyses were computed with PLINK17 (version 1.05). Autosomal-wide analysis was performed via the TREND test with 1 degree of freedom (df). The X chromosome (females and males combined) was analyzed via the Wald test with 1 df. In replication I and the meta-analysis (GWAS and replication I), autosomal and X-chromosomal SNPs were investigated via the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) test, stratified for ethnicity with the use of a 2 × 2 × K table in which K = 6, reflecting the six European countries. The CMH test was two-tailed for all analyses. To investigate the homogeneity of ORs for the replicated SNPs, we used the Breslow-Day test. We selected p < 5 × 10−8 as the threshold for genome-wide significance, assuming one million noncorrelated common SNPs in the genome, as proposed by the Diabetes Genetics Initiative18 and the International HapMap Consortium.19 In the replication II step, NCAN rs1064395 was investigated via logistic regression (assuming an additive effect), which was a two-tailed test. NCAN rs1064395 was also investigated with the use of a fixed-effects meta-analysis based on the weighted Z-score method,20 which was two-tailed for replication II samples (n = 7) and for the combined analysis of all study samples (n = 14).

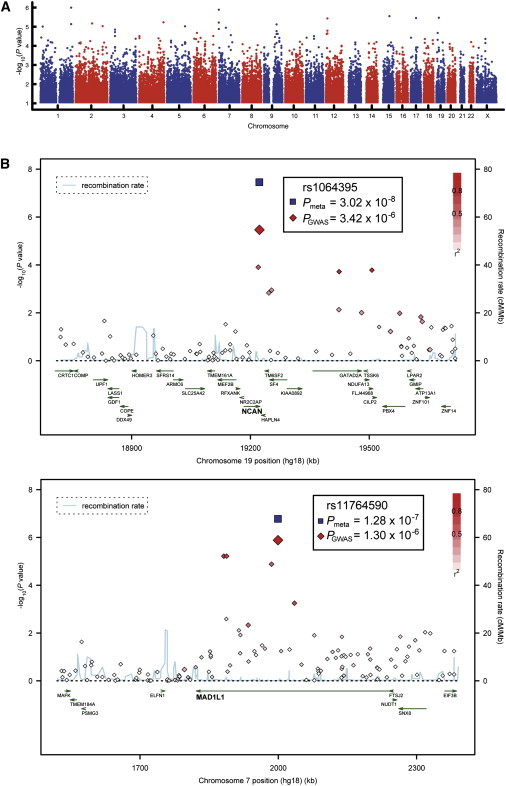

On the basis of the QC specifications and statistical procedures described above, we performed a GWAS of 682 BD patients and 1300 controls (Table 1), using 499,494 autosomal SNPs and 12,484 X-chromosomal SNPs. A genome-wide overview of the GWAS p values is given in Figure 1A. In the first follow-up step (replication I), we genotyped the most significant 48 SNPs (autosomal SNPs: p ≤ 7.57 × 10−5; X-chromosomal SNPs: p ≤ 1.89 × 10−4; for SNPs in LD (r2 ≥ 0.8), only the SNP with the smallest GWAS p value was genotyped in the follow-up) in six European follow-up samples comprising a total of 1729 BD patients and 2313 controls (Table 1). The same set of instruments was used across all centers.21 In the replication, we used phenotypically more relaxed criteria than in the initial GWAS and also included patients with a diagnosis of BD type II, schizoaffective disorder (bipolar type), and BD not otherwise specified. To account for possible heterogeneity, autosomal and X-chromosomal we investigated SNPs via the CMH test and stratified them with regard to ethnicity. Eight of the 48 SNPs showed nominally significant association in the combined replication samples, all with the same alleles as in the GWAS (Table 2, Table S3). This number of replicated SNPs is significantly higher than would be expected to occur by chance (nexpected = 2.4; p = 2.11 × 10−4). The strongest evidence for replication was obtained for rs1064395, which is located in the 3′ untranslated region of NCAN on 19p13.11 (p = 4.61 × 10−4, OR = 1.23), and for rs11764590, which is located in an intron of MAD1L1 (MIM 602686) on 7p22.3 (p = 0.0020, OR = 1.18). Our top GWAS signal, rs2774339, located in GNG4 (MIM 604388) on 1q42.3 (p = 1.02 × 10−6; Figure S3) was not replicated (p = 0.5772). Given that our follow-up samples were derived from six different European countries, we specifically tested for possible heterogeneity by using the replication data. In the case of the successfully replicated SNPs, there was no evidence of ethnic heterogeneity (Breslow-Day pmin = 0.178). In support of this was the observation that subtraction of any individual replication sample did not markedly alter the effect sizes (Table S4).

Figure 1.

Association Results for the GWAS and the Two Best-Supported Genes from the Follow-Up Study

(A) Manhattan plot.

(B) Regional association plots (RAPs) displaying NCAN and MAD1L1. The most associated marker from the GWAS (enlarged red diamond) is centered in a genomic window of 1 Mb (hg18, RefSeq genes); its p value from the combined analysis (meta) is shown (enlarged blue diamond). The LD strength (r2) between the sentinel SNP from the GWAS and its flanking markers is demonstrated by the red (high) to white (low) color bar. The recombination rate (cM/Mb; second y axis) is plotted in blue, according to HapMap-CEU. RAPs were generated with SNAP.42

Table 2.

Eight GWAS SNPs Showing Evidence for Association with BD In Six Independent Samples of BD

|

Association Data (BD) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

GWAS |

Replication I |

Combined |

||||||||

|

SNP Data |

TREND |

MAF |

CMH (K = 6) |

MAF |

CMH (K = 6) |

Gene Data |

||||

| Band | SNP, MA | p Value | OR | Pat / Con (682 / 1300) | p Value | OR | Pat / Con (1729 / 2313) | p Value | OR | Nearest Gene or Transcript |

| 19p13.11 | rs1064395, A | 3.42 × 10−6 | 1.53 | 0.19 / 0.14 | 4.61 × 10−4 | 1.23 | 0.20 / 0.16 | 3.02 × 10−8 | 1.31 | NCAN, 3′ UTR |

| 7p22.3 | rs11764590, T | 1.30 × 10−6 | 1.47 | 0.27 / 0.20 | 2.01 × 10−3 | 1.18 | 0.26 / 0.22 | 1.28 × 10−7 | 1.26 | MAD1L1, intron |

| 7p22.3 | rs10278591, T | 6.05 × 10−6 | 1.43 | 0.27 / 0.21 | 0.0348 | 1.12 | 0.26 / 0.23 | 1.81 × 10−5 | 1.21 | MAD1L1, intron |

| 2p23.2 | rs6547829, T | 7.21 × 10−5 | 1.59 | 0.11 / 0.07 | 0.0134 | 1.22 | 0.09 / 0.08 | 2.50 × 10−5 | 1.32 | BRE, intron |

| 7q22.1 | rs985409, G | 6.52 × 10−5 | 1.31 | 0.45 / 0.38 | 0.0206 | 1.11 | 0.47 / 0.44 | 3.89 × 10−5 | 1.17 | LHFPL3, intron |

| 9q21.31 | rs2209263, A | 3.44 × 10−5 | 0.73 | 0.24 / 0.30 | 0.0436 | 0.90 | 0.26 / 0.28 | 5.58 × 10−5 | 0.84 | TLE4; TLE1 |

| 3q28 | rs779279, A | 4.25 × 10−5 | 0.76 | 0.41 / 0.48 | 0.0402 | 0.91 | 0.46 / 0.48 | 6.39 × 10−5 | 0.86 | FGF12; PYDC2 |

| 14q21.1 | rs9322993, T | 7.56 × 10−5 | 1.75 | 0.07 / 0.04 | 0.0382 | 1.23 | 0.06 / 0.05 | 7.54 × 10−5 | 1.37 | SIP1, intron |

In the six different clusters (countries), all SNPs were in HWE in patients and controls (p > 0.05).

The following abbreviations are used: MA, minor allele, refers to dbSNP build 130; TREND, Cochran-Armitage test; OR, odds ratio referring to the minor allele; MAF, minor allele frequency; Pat, patients; Con, controls; CMH, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test; K, CMH's cluster variable; UTR, untranslated region.

In a subsequent analysis, we applied a meta-analysis approach (CMH test) to combine all investigated samples. SNP rs1064395 in NCAN surpassed the threshold for genome-wide significance (p = 3.02 × 10−8, OR = 1.31; Figure 1B); the minor allele (A) was overrepresented in patients in comparison to controls (19.5% versus 15.3%). The second-best result was found for MAD1L1 rs11764590 (p = 1.28 × 10−7, OR = 1.26; Figure 1B): an excess of T alleles was observed in patients (26.0% versus 21.6%). Another MAD1L1 marker, rs10278591, which was in moderate LD with rs11764590 (r2 = 0.70), showed p = 1.81 × 10−5. HapMap-based imputations of our BD GWAS data provided additional support for the NCAN and MAD1L1 regions (Figures S4a and S4b). After QC of real genotypes, locus-targeted imputations were performed in MACH (version 1.0.16) (Y. Li and G.R. Abecasis, 2006, Am. Soc. Hum. Genet. abstract) with phased haplotypes from the 60 HapMap CEU founders (release 22) used as a reference. The imputations were restricted to windows of 2 Mb on either side of the sentinel SNP. Imputed SNPs with a MACH quality score less than 95% were excluded before the association analysis. Regional association plots for the other five replicated SNPs are provided in Figures S4c–S4g and Figures S5a–S5e.

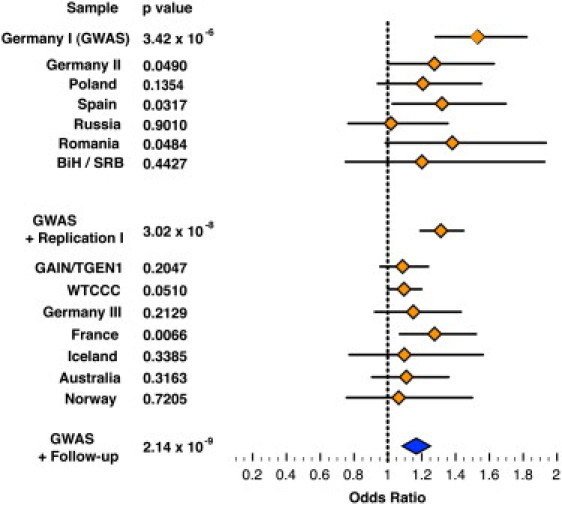

In a second replication step, we sought further support for the genome-wide significant finding in NCAN and tested rs1064395 in BD samples from Europe (WTCCC-BD,1 Germany III, France, Iceland, Norway), from the USA (combined GAIN-EA6/TGEN1), and from Australia. In all seven patient samples, the A allele was overrepresented (Table 3). Through logistic regression assuming an additive effect, the GAIN-EA/TGEN1 samples showed p = 0.2047 (OR = 1.09), WTCCC-BD/Expanded Reference Controls showed p = 0.0510 (OR = 1.09), Germany III samples showed p = 0.2129 (OR = 1.15), those from France showed p = 0.0066 (OR = 1.28), those from Iceland showed p = 0.3385 (OR = 1.10), those from Australia showed p = 0.3163 (OR = 1.11), and those from Norway showed p = 0.7205 (OR = 1.06). The fixed-effects meta-analysis of these samples, totaling 6030 patients and 31,749 controls, resulted in p = 2.74 × 10−4 (OR = 1.12).

Table 3.

Association Results for NCAN rs1064395 at All Steps of the Analysis: GWAS, Replication I, and Replication II

| Sample | N Patients | N Controls | Test, p Value | OR | MA | MAF: Patients | MAF: Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS | 682 | 1300 | TREND, 3.42 × 10−6 | 1.53 | A | 0.19 | 0.14 |

| Germany I | |||||||

| Replication I | 1729 | 2313 | CMH (K = 6), 4.61 × 10−4 | 1.23 | |||

| Germany II | TREND, 0.0490 | 1.28 | A | 0.17 | 0.14 | ||

| Poland | TREND, 0.1354 | 1.21 | A | 0.17 | 0.15 | ||

| Spain | TREND, 0.0317 | 1.32 | A | 0.26 | 0.21 | ||

| Russia | TREND, 0.9010 | 1.02 | A | 0.18 | 0.17 | ||

| Romania | TREND, 0.0484 | 1.38 | A | 0.21 | 0.17 | ||

| Bosnia and Herzegovina / Serbia | TREND, 0.4427 | 1.20 | A | 0.21 | 0.18 | ||

| GWAS + Replication I | 2411 | 3613 | CMH (K = 6), 3.02 × 10−8 | 1.31 | |||

| Replication II | 6030 | 31,749 | FEM1 (n = 7), 2.74 × 10−4 | 1.12 | |||

| GAIN-EA / TGEN1 | 2189 | 1434 | L, 0.2047 | 1.09 | A | 0.17 | 0.15 |

| WTCCC-BD / Exp. Ref. Grp. | 1868 | 14,311 | L, 0.0510 | 1.09 | A | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| Germany III | 497 | 857 | L, 0.2129 | 1.15 | A | 0.17 | 0.14 |

| France | 471 | 1758 | L, 0.0066 | 1.28 | A | 0.22 | 0.19 |

| Iceland | 422 | 11,487 | L, 0.3385 | 1.10 | A | 0.16 | 0.15 |

| Australia | 380 | 1530 | L, 0.3163 | 1.11 | A | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| Norway | 203 | 372 | L, 0.7205 | 1.06 | A | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| GWAS + Replication I + Replication II | 8441 | 35,362 | FEM2 (n = 14), 2.14 × 10−9 | 1.17 | |||

The following abbreviations are used: TREND, Cochran-Armitage test; CMH, Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test; FEM, fixed-effects meta-analysis based on the weighted z-score method;20 L, logistic regression assuming an additive effect; OR, odds ratio referring to the minor allele (MA); n, number of analyzed study samples; MAF, MA frequency; Pat, patients; Con, controls.

The combined analysis of all study samples (GWAS + replication I + replication II), with 8441 patients and 35,362 controls, resulted in p = 2.14 × 10−9 (OR = 1.17). An overview of the significance levels and genetic effect sizes of NCAN rs1064395 at all steps of analysis is provided in Figure 2 and Table 3. It is interesting to note that there is no improvement of the OR when we perform an analysis of BD type I only (OR = 1.16), providing no strong evidence that genetic variation in NCAN would have a much stronger effect in BD type I compared to the other diagnoses included in our study (BD type II, schizoaffective disorder [bipolar type], and BD not otherwise specified).

Figure 2.

Genetic Effect Sizes and Significance Levels for NCAN rs1064395 at All Steps of Analysis

Forest plot shows odds ratios (orange diamonds) and their 95% confidence intervals (horizontal lines) of individual study samples. The odds ratio referring to the meta-analysis of all study samples is represented by the enlarged blue diamond. BiH / SRB, Bosnia and Herzegovina / Serbia.

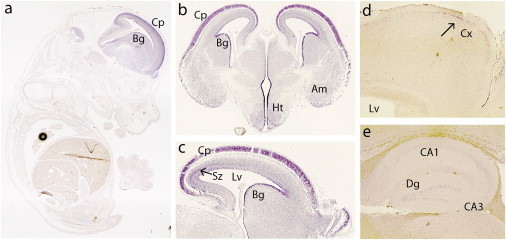

Neurocan was originally described in the rat brain,22 where its expression decreases significantly in the first week after birth.23 To validate whether Ncan is expressed in brain areas previously implicated in BD,24 we performed RNA in situ hybridization with whole mounts and sections from embryonic and postnatal wild-type mice, using procedures described previously.25 We amplified Ncan probes from postnatal day 46 (P46) mouse brain cDNA (strain C57BL/6), covering nucleotides 5715–6515 of GenBank accession NM_007789.3. This was cloned into pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). Animals were handled according to European and German laws. At embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5), Ncan expression was confined to the central nervous system (Figure 3A). However, Ncan transcripts have also been described in the peripheral nervous system in later developmental stages.26 Between E14.5 and E16.5, Ncan was highly expressed in the cortical plate, as well as in the ventricular zone of the basal ganglia (Figures 3A–3C). In the subventricular zone of the neocortex, the transcripts were located mainly in the caudal region (Figure 3C), where neurocan proteins may be involved in axon guidance.27 Ncan was also present in the developing hippocampus (data not shown). After birth, its general expression was found to be decreased. It was detected in the dentate gyrus and CA1 of the hippocampus (Figure 3E), as well as in the cortical layer II (Figure 3D) at P46. Its expression in the cortical layer II remained unabated, at least up to P18, with higher expression in the frontal cortex (data not shown). On the contrary, Ncan expression was not detected in any hippocampal area at this age.

Figure 3.

Expression Patterns of Neurocan in Mouse Brain Areas Previously Implicated in BD

RNA in situ hybridization of Ncan in sagittal (A, C–E) and coronal (B) sections at E14.5 (A), E15.5 (B), E16.5 (C), and P46 (D and E). In the embryo, Ncan is observed exclusively in the CNS, with high expression in the cortical plate (Cp) and subventricular zone (Sz, arrow in C) of the neocortex and in the ventricular zone of the basal ganglia (Bg, A–C). Ncan was also detected in the hypothalamus (Ht) and amygdala (Am, B). In postnatal mice, Ncan expression in the cortex (Cx) is restricted to layer II (arrow in D). In the hippocampus (E), it was detected at lower intensity in the dentate gyrus (Dg) and CA1. Lv indicates the lateral ventricle.

To investigate whether NCAN and MAD1L1 are expressed in the human brain, we analyzed the transcriptional expression of both genes in human hippocampus tissue samples (n = 148), using data from whole-genome HumanHT-12 Expression BeadChips (Illumina, San Diego, USA). Tissues were obtained from surgery on patients with pharmaco-resistant epilepsy. Total RNA was isolated from fresh frozen tissues and underwent QC via BioAnalyzer measurements (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). The background of expression profiles was subtracted and signals were normalized (average-normalization) with Illumina's GenomeStudio software. The analysis showed that NCAN and MAD1L1 were expressed in the hippocampus (Figure S6). For NCAN, an average signal-intensity log2 ratio of 7.99 with a standard deviation of 0.8 (intensities, min = 5.82 and max = 10.4) was detected, and for MAD1L1, an average signal-intensity log2 ratio of 5.21 with a standard deviation of 0.46 (intensities, min = 3.55 and max = 6.1) was detected.

Our GWAS and follow-up study of BD samples, including a total of 43,803 individuals (8441 patients and 35,362 controls), provided a significant level of statistical support for the idea that common genetic variation in NCAN is involved in the etiology of this common and severe neuropsychiatric disorder. The overall p value for the top-associated SNP, rs1064395, was 2.14 × 10−9 (OR = 1.17). NCAN encodes neurocan (MIM 600826), an extracellular matrix glycoprotein. The gene is highly expressed in the brain, and is thought to be involved in cell adhesion and migration. To map its spatiotemporal expression, we performed in situ hybridizations in embryonic and postnatal wild-type mice. We observed that murine Ncan was expressed in cortical and hippocampal areas and could confirm that NCAN transcripts are highly abundant in the human hippocampus. These brain regions, which are involved in cognition and regulation of circuits involved in emotion, have previously been implicated in BD by neuropsychological, neuroimaging, and postmortem studies.28 Ncan-deficient mice show no obvious defect in brain morphology, and basic synaptic transmission appears to be normal.26 However, the maintenance of late-phase long-term potentiation in the hippocampal CA1 region in null mutants is reduced, which could lead to mild deficits in learning and memory;26 i.e., there are disturbances in the mechanisms that underlie the cognitive deficits observed in BD. This suggests that Ncan-deficient mice should be reexamined for more subtle changes in the brain, such as synaptic plasticity.

MAD1L1 (mitotic arrest deficient-like 1 [MIM 602686]) is a component of the chromosome spindle-assembly checkpoint in mitosis. Defects in mitotic checkpoints can lead to aneuploidy, which may play a role in carcinogenesis and aging.29 Homozygous knockout of Mad1l1 in mice confers embryonic lethality, which indicates that it has an essential function in development.30 MAD1L1 is expressed in the human hippocampus (Figure S6), although its neurobiological effects have not been established.

In summary, the present study has identified a susceptibility factor for BD, NCAN, and a potential BD susceptibility factor, MAD1L1. Expression studies in mice provide strong support for a role of NCAN in BD, because its expression is localized to brain areas (cortex, hippocampus) in which abnormalities have been identified in BD. These abnormalities may be indicative of disturbances in key neuronal circuits.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all patients who contributed to this study. We also thank all probands from the community-based cohorts of PopGen, KORA, those from the Heinz Nixdorf Recall (HNR) study, and the Munich controls. This study was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), within the context of the National Genome Research Network 2 (NGFN-2), the National Genome Research Network plus (NGFNplus), and the Integrated Genome Research Network (IG) MooDS (grant 01GS08144 to S.C. and M.M.N., grant 01GS08147 to M.R.). M.M.N. also received support from the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Stiftung. M.G.-S. was supported by the Romanian Ministry for Education and Research (grant 42151/2008). C.C.D. was supported by the SOP HRD and was financed from the European Social Fund and by the Romanian Government (contract POSDRU/89/1.5/S/64109). This study was also supported by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (grant N N402 244035 to P.M.C.) The KORA research platform was initiated and financed by the Helmholtz Center Munich, German Research Center for Environmental Health, which is funded by the BMBF and by the State of Bavaria. KORA research was supported within the Munich Center of Health Sciences (MC Health) as part of LMUinnovativ. The HNR cohort was established with the support of the Heinz Nixdorf Foundation. We acknowledge the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium (www.wtccc.org.uk), its membership, and its funder, the Wellcome Trust, for generating and publishing data used for replication. Recruitment of the French sample was supported by ANR (ANR NEURO2006, MANAGE_BPAD), INSERM, AP-HP, and the FondaMental Foundation (www.fondation-fondamental.org). Recruitment of the Australian BD sample was supported by the Australian NHMRC program, grant number 510135. The Norwegian study was supported by the Research Council of Norway (#167153/V50, #163070/V50, #175345/V50) and by the South-East Norway Health Authority (#123-2004). We are grateful to A. Becker, Department of Neuropathology, University of Bonn, Germany, for providing the human hippocampus tissue that was used in the gene expression analysis.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

The International HapMap Project, http://www.hapmap.org/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/

PLINK: Whole Genome Association Analysis Toolset, http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/∼purcell/plink/

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism database (dbSNP), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/

SNAP: A web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap, http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/snap/

References

- 1.Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum A.E., Akula N., Cabanero M., Cardona I., Corona W., Klemens B., Schulze T.G., Cichon S., Rietschel M., Nöthen M.M. A genome-wide association study implicates diacylglycerol kinase eta (DGKH) and several other genes in the etiology of bipolar disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2008;13:197–207. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sklar P., Smoller J.W., Fan J., Ferreira M.A., Perlis R.H., Chambert K., Nimgaonkar V.L., McQueen M.B., Faraone S.V., Kirby A. Whole-genome association study of bipolar disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2008;13:558–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferreira M.A., O'Donovan M.C., Meng Y.A., Jones I.R., Ruderfer D.M., Jones L., Fan J., Kirov G., Perlis R.H., Green E.K., Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Collaborative genome-wide association analysis supports a role for ANK3 and CACNA1C in bipolar disorder. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1056–1058. doi: 10.1038/ng.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott L.J., Muglia P., Kong X.Q., Guan W., Flickinger M., Upmanyu R., Tozzi F., Li J.Z., Burmeister M., Absher D. Genome-wide association and meta-analysis of bipolar disorder in individuals of European ancestry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:7501–7506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813386106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith E.N., Bloss C.S., Badner J.A., Barrett T., Belmonte P.L., Berrettini W., Byerley W., Coryell W., Craig D., Edenberg H.J. Genome-wide association study of bipolar disorder in European American and African American individuals. Mol. Psychiatry. 2009;14:755–763. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baum A.E., Hamshere M., Green E., Cichon S., Rietschel M., Noethen M.M., Craddock N., McMahon F.J. Meta-analysis of two genome-wide association studies of bipolar disorder reveals important points of agreement. Mol. Psychiatry. 2008;13:466–467. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulze T.G., Detera-Wadleigh S.D., Akula N., Gupta A., Kassem L., Steele J., Pearl J., Strohmaier J., Breuer R., Schwarz M., NIMH Genetics Initiative Bipolar Disorder Consortium Two variants in Ankyrin 3 (ANK3) are independent genetic risk factors for bipolar disorder. Mol. Psychiatry. 2009;14:487–491. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Psychiatric Association (APA) Fourth Edition. American Pychiatric Association; Washington, D.C.: 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leckman J.F., Sholomskas D., Thompson W.D., Belanger A., Weissman M.M. Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: a methodological study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1982;39:879–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290080001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B., Gibbon M., First M.B. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080032005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farmer A.E., Wessely S., Castle D., McGuffin P. Methodological issues in using a polydiagnostic approach to define psychotic illness. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1992;161:824–830. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.6.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krawczak M., Nikolaus S., von Eberstein H., Croucher P.J., El Mokhtari N.E., Schreiber S. PopGen: population-based recruitment of patients and controls for the analysis of complex genotype-phenotype relationships. Community Genet. 2006;9:55–61. doi: 10.1159/000090694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wichmann H.E., Gieger C., Illig T., MONICA/KORA Study Group KORA-gen—resource for population genetics, controls and a broad spectrum of disease phenotypes. Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67(Suppl 1):S26–S30. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmermund A., Möhlenkamp S., Stang A., Grönemeyer D., Seibel R., Hirche H., Mann K., Siffert W., Lauterbach K., Siegrist J. Assessment of clinically silent atherosclerotic disease and established and novel risk factors for predicting myocardial infarction and cardiac death in healthy middle-aged subjects: rationale and design of the Heinz Nixdorf RECALL Study. Risk Factors, Evaluation of Coronary Calcium and Lifestyle. Am. Heart J. 2002;144:212–218. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller S.A., Dykes D.D., Polesky H.F. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purcell S., Neale B., Todd-Brown K., Thomas L., Ferreira M.A., Bender D., Maller J., Sklar P., de Bakker P.I., Daly M.J., Sham P.C. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saxena R., Voight B.F., Lyssenko V., Burtt N.P., de Bakker P.I., Chen H., Roix J.J., Kathiresan S., Hirschhorn J.N., Daly M.J., Diabetes Genetics Initiative of Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, Lund University, and Novartis Institutes of BioMedical Research Genome-wide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science. 2007;316:1331–1336. doi: 10.1126/science.1142358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.International HapMap Consortium A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Bakker P.I., Ferreira M.A., Jia X., Neale B.M., Raychaudhuri S., Voight B.F. Practical aspects of imputation-driven meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17(R2):R122–R128. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fangerau H., Ohlraun S., Granath R.O., Nöthen M.M., Rietschel M., Schulze T.G. Computer-assisted phenotype characterization for genetic research in psychiatry. Hum. Hered. 2004;58:122–130. doi: 10.1159/000083538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rauch U., Karthikeyan L., Maurel P., Margolis R.U., Margolis R.K. Cloning and primary structure of neurocan, a developmentally regulated, aggregating chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan of brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:19536–19547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milev P., Monnerie H., Popp S., Margolis R.K., Margolis R.U. The core protein of the chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan phosphacan is a high-affinity ligand of fibroblast growth factor-2 and potentiates its mitogenic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:21439–21442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinowich K., Schloesser R.J., Manji H.K. Bipolar disorder: from genes to behavior pathways. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:726–736. doi: 10.1172/JCI37703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miró X., Zhou X., Boretius S., Michaelis T., Kubisch C., Alvarez-Bolado G., Gruss P. Haploinsufficiency of the murine polycomb gene Suz12 results in diverse malformations of the brain and neural tube. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2:412–418. doi: 10.1242/dmm.001602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou X.H., Brakebusch C., Matthies H., Oohashi T., Hirsch E., Moser M., Krug M., Seidenbecher C.I., Boeckers T.M., Rauch U. Neurocan is dispensable for brain development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:5970–5978. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.5970-5978.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe E., Aono S., Matsui F., Yamada Y., Naruse I., Oohira A. Distribution of a brain-specific proteoglycan, neurocan, and the corresponding mRNA during the formation of barrels in the rat somatosensory cortex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1995;7:547–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frey B.N., Andreazza A.C., Nery F.G., Martins M.R., Quevedo J., Soares J.C., Kapczinski F. The role of hippocampus in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder. Behav. Pharmacol. 2007;18:419–430. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282df3cde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herzog F., Primorac I., Dube P., Lenart P., Sander B., Mechtler K., Stark H., Peters J.M. Structure of the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome interacting with a mitotic checkpoint complex. Science. 2009;323:1477–1481. doi: 10.1126/science.1163300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwanaga Y., Chi Y.H., Miyazato A., Sheleg S., Haller K., Peloponese J.M., Jr., Li Y., Ward J.M., Benezra R., Jeang K.T. Heterozygous deletion of mitotic arrest-deficient protein 1 (MAD1) increases the incidence of tumors in mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:160–166. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The AMDP System . Springer; Berlin: 1982. The AMDP-System Association of Methodology and Documentation in Psychiatry. Manual For the Assessment and Documentation of Psychopathology. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters L., Andrews G. Procedural validity of the computerized version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI-Auto) in the anxiety disorders. Psychol. Med. 1995;25:1269–1280. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wittchen H.U., Zhao S., Abelson J.M., Abelson J.L., Kessler R.C. Reliability and procedural validity of UM-CIDI DSM-III-R phobic disorders. Psychol. Med. 1996;26:1169–1177. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wittchen H.U., Höfler M., Gander F., Pfister H., Storz S., Üstün T.B., Müller N., Kessler R.C. Screening for mental disorders: performance of the Composite International Diagnostic-Screener (CID-S) Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 1999;8:59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nurnberger J.I., Jr., Blehar M.C., Kaufmann C.A., York-Cooler C., Simpson S.G., Harkavy-Friedman J., Severe J.B., Malaspina D., Reich T. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies. Rationale, unique features, and training. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:849–859. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950110009002. discussion 863–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maxwell M.E. National Institute of Mental Health; Bethesda, MD: 1992. Family Interview for Genetic Studies (FIGS): Manual For FIGS. Clinical Neurogenetics Branch. Intramural Research Program. [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO; Geneva: 1992. The ICD 10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B., Kroenke K., Linzer M., deGruy F.V., 3rd, Hahn S.R., Brody D., Johnson J.G. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spitzer R.L., Endicott J., Robins E. Research diagnostic criteria: rationale and reliability. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1978;35:773–782. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Endicott J., Spitzer R.L. A diagnostic interview: the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1978;35:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770310043002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wing J.K., Babor T., Brugha T., Burke J., Cooper J.E., Giel R., Jablenski A., Regier D., Sartorius N., Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry SCAN. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1990;47:589–593. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810180089012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson A.D., Handsaker R.E., Pulit S.L., Nizzari M.M., O'Donnell C.J., de Bakker P.I.W. SNAP: a web-based tool for identification and annotation of proxy SNPs using HapMap. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2938–2939. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.