Summary

Head-on encounters between the replication and transcription machineries on the lagging DNA strand can lead to replication fork arrest and genomic instability1,2. To avoid head-on encounters, most genes, especially essential and highly transcribed genes, are encoded on the leading strand such that transcription and replication are co-directional. Virtually all bacteria have the highly expressed rRNA genes co-directional with replication3. In bacteria, co-directional encounters seem inevitable because the rate of replication is about 10-20-fold greater than the rate of transcription. However, these encounters are generally thought to be benign2,4-9. Biochemical analyses indicate that head-on encounters10 are more deleterious than co-directional encounters8, and that in both situations, replication resumes without the need for any auxiliary restart proteins, at least in vitro. Here we show that in vivo, co-directional transcription can disrupt replication leading to the involvement of replication restart proteins. We found that highly transcribed rRNA genes are hotspots for co-directional conflicts between replication and transcription in rapidly growing Bacillus subtilis cells. We observed a transcription-dependent increase in association of the replicative helicase and replication restart proteins where head-on and co-directional conflicts occur. Our results indicate that there are co-directional conflicts between replication and transcription in vivo. Furthermore, in contrast to the findings in vitro, the replication restart machinery is involved in vivo in resolving potentially deleterious encounters due to head-on and co-directional conflicts. These conflicts likely occur in many organisms and at many chromosomal locations and help to explain the presence of important auxiliary proteins involved in replication restart and in helping to clear a path along the DNA for the replisome.

The DNA replication machinery (replisome) often encounters obstacles along the genome that can cause replication fork arrest1,2 (Supplementary Fig. 1). In bacteria, replication, transcription, and translation occur concurrently, and RNA polymerase (RNAP) transcribing the lagging strand (head-on relative to replication) is a well-known obstacle encountered by the replisome1,4-7,9,11-14. Transcription-replication conflicts are compounded during rapid growth when transcription initiation of many genes, especially those encoding the protein synthesis machinery, increases. In Bacillus subtilis, head-on conflicts between replication and transcription slow the overall rate of replication fork progression, largely due to obstruction of the replisome9,12.

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes (Supplementary Fig. 2) are among the most highly expressed in rapidly growing bacteria, and are co-directional with replication (i.e., encoded on the leading strand), thereby avoiding head-on conflicts3. Nonetheless, co-directional encounters between bacterial replication and transcription machineries seem inevitable since the rate of replication (~500-1000 nucleotides/sec) is ~10-20 times faster than that of transcription1. The potential for co-directional conflicts is widely recognized1,2,11, but these conflicts have not been detected in vivo4-6,9, with the exception of co-directionally positioned transcription terminators that can inhibit replication fork progression7. In addition, during co-directional encounters engineered to occur in vitro, the replicative helicase translocating along the lagging strand simply displaces RNAP translocating along the leading strand2,8. Thus, co-directional encounters are generally thought to have little or no effect on replication1,2,11.

All organisms have mechanisms for loading a helicase onto DNA during replication fork assembly. DnaA-dependent mechanisms load the replicative helicase at the origin of replication, oriC, and recombination-based and PriA-dependent mechanisms restart forks from stalled sites15. Although DnaA and PriA are ubiquitous, other helicase-loading proteins differ among bacteria. In B. subtilis, and other low G+C Gram-positive organisms, DnaD and DnaB participate in loading the replicative helicase, DnaC, both at oriC and during replication restart at stalled forks16-20. We measured association of DnaD, DnaB, and helicase with chromosomal regions using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and either quantitative real time PCR (ChIP-qPCR) to detect specific regions, or hybridization to DNA microarrays (ChIP-chip) for genome-wide analysis (Methods).

We analysed head-on conflicts between transcription and replication in a specific chromosomal region. Pxis, a promoter from the conjugative transposon ICEBs1, is highly expressed in the absence of the transposon-encoded immunity repressor ImmR (Methods). Using ChIP-qPCR, we found that there was a 2-fold increase in association of DnaD, DnaB, and helicase with the chromosomal region (thrC) expressing a Pxis-lacZ fusion compared with other chromosomal regions (Supplementary Fig. 3). In contrast, when Pxis-lacZ was off, in cells containing ICEBs1 and its repressor, there was no detectable enrichment of these proteins (Supplementary Fig. 3). Thus, head-on conflicts between replication and transcription in vivo can be detected by increased association of the replicative helicase and the replication restart proteins with the region of conflict. The association of helicase likely indicates replisome stalling in this region. Association of DnaD and DnaB indicates that these proteins are most likely acting to reload the helicase for replication restart. It is formally possible that DnaD and DnaB are part of the replisome or are associated with the replication fork. If true, then their association could indicate fork stalling and/or restart. However, neither DnaD nor DnaB are required for replication elongation, nor do they appear to be associated with the replication fork21,22. Thus, it seems most likely that their association is indicative of replication restart.

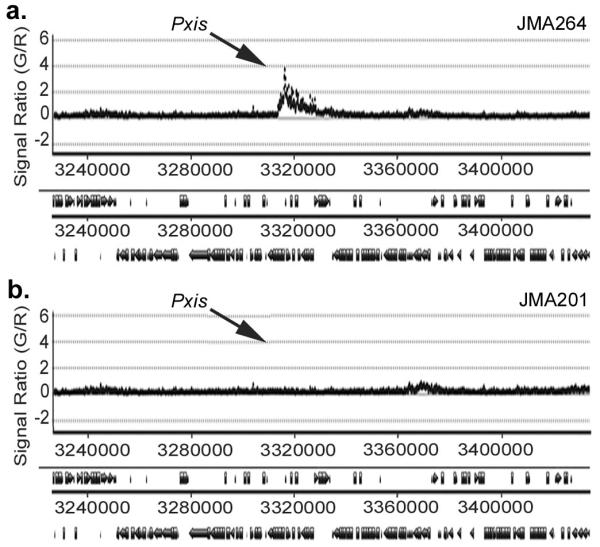

We also detected the head-on conflict between replication and transcription in ChIP-chip assays. When Pxis-lacZ was expressed, there was increased association of DnaB with this region (Fig. 1a). In contrast, in cells not expressing Pxis-lacZ, there was little or no detectable association of DnaB with this region (Fig. 1b), although there was association of DnaB with other chromosomal regions (see below). These results indicate that association of DnaB with the region near Pxis-lacZ depends on transcription from Pxis.

Fig. 1.

Head-on conflicts between transcription and replication cause increased association of helicase loader protein DnaB. Association of DnaB was assessed in ChIP-chip experiments in strains containing Pxis-lacZ inserted at thrC. Cells were grown in rich medium (LB) and sampled during exponential growth. The relative enrichment of a given chromosomal position is plotted on the y-axis vs the chromosomal position on the x-axis (in bp clockwise from oriC). Data are shown for the chromosomal region from ~3,240 kb through ~3,400 kb. The location of Pxis-lacZ inserted at thrC is indicated. Pxis-lacZ is head-on with replication. a. Data from cells expressing Pxis-lacZ (strain JMA264). b. Data from cells not expressing Pxis-lacZ (strain JMA201). These findings were verified by qPCR (Supplementary Fig. 3).

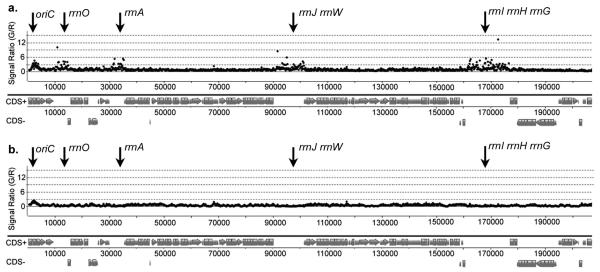

We analysed genome-wide association of the replication restart proteins DnaD and DnaB in wild type cells using ChIP-chip. There was significant enrichment of the oriC region and the 10 rrn (rRNA) loci in the DnaD (Supplementary Fig. 4a) and DnaB (Fig. 2a; Supplementary Fig. 5) immunoprecipitates compared to most other chromosomal regions (Supplementary Discussion). rrn loci are among the most highly transcribed genes during rapid growth and are transcribed on the leading strand. The presence of DnaD and DnaB might be indicative of replication restart after fork stalling in these highly transcribed regions. This enrichment was dependent on rapid growth. During slow growth in minimal medium, there was little or no detectable enrichment of rrn loci in the DnaD (Supplementary Fig. 4b) or DnaB (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 5) immunoprecipitates. Since the genome sequencing project for B. subtilis used a “consensus sequence” for all rRNA genes23, and the sequences of each were reported as identical, our results indicate that at least one, and likely multiple rrn loci are enriched in the immunoprecipitates (see below), and that this enrichment is reproducible and most noticeable during rapid growth when the rrn loci are most highly expressed.

Fig. 2.

ChIP-chip analysis of DnaB. Wild type cells (strain 168) were grown in LB (a) or defined minimal medium (b) and sampled during exponential growth. Data are plotted as in Fig. 1, except the chromosomal positions are shown from 0 kb (oriC) to just past rrnI, H, G at ~200 kb. Similar results were obtained at each identical rrn with both DnaD and DnaB, indicating the reproducibility of the data. Results were also confirmed by qPCR with independent samples from different strains (Fig. 3). Data from other rrn regions are presented in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 5). The rrn sequences represent a consensus and were thus presented as identical23. For clarity and simplicity, we unambiguously label each individual locus according to its chromosomal location.

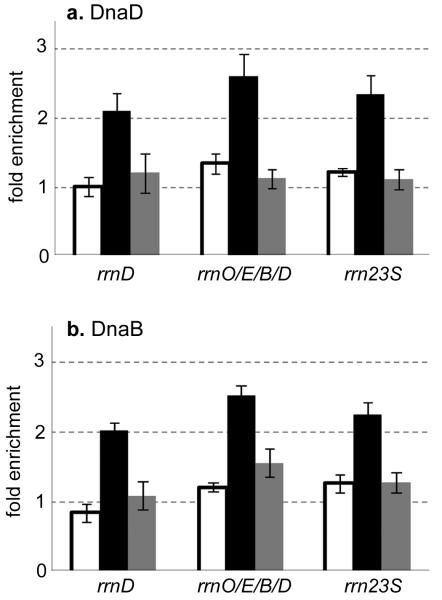

We also used ChIP-qPCR to measure association of DnaD and DnaB with rrn loci. Primer pairs were designed to detect DNA from three different regions of rRNA genes (Supplementary Fig. 2b-d): 1) a region unique to rrnD immediately upstream of its 16S gene and far from oriC (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b); 2) a region just upstream and overlapping the 16S genes of rrnO, E, D, B (Supplementary Fig. 2c); and 3) a region that should be common to all 23S genes (Supplementary Fig. 2d). There was significant enrichment of the rrn loci in samples from both the DnaD (Fig. 3a) and DnaB (Fig. 3b) immunoprecipitates, similar to the results from the ChIP-chip analyses (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 4). The ChIP signals were similar with all three probes because the qPCR normalizes to the number of copies of each region. These results indicate that DnaD and DnaB are associated with rrnD, and likely most or all rrn loci.

Fig. 3.

Association of helicase loader proteins DnaD and DnaB with rrn loci depends on transcription and the replication restart protein priA. Wild type cells (AG174) and the priA-ssrA* mutant (WKS338) were grown to mid-exponential phase in LB medium. For wild type, samples were taken in the absence (black bars) or 4 min after treatment (gray bars) with rifampicin (30 μg/ml) to block transcription initiation. The priA-ssrA* mutant (grown in the presence of 1 μg/ml of chloramphenicol to maintain selection for the mutant allele) was sampled in the absence of rifampicin (white bars). Association of DnaD (a) and DnaB (b) was analysed by ChIP-qPCR with three different primer pairs (Supplementary Fig. 2) that recognize the indicated rrn loci. The ChIP-qPCR signals are normalized to gene copy number (Methods), so that the signal for the 23S rrn probe, which should detect all 10 rrn loci, is normalized per locus. Data are averages from at least three independent cultures. Error bars represent standard error.

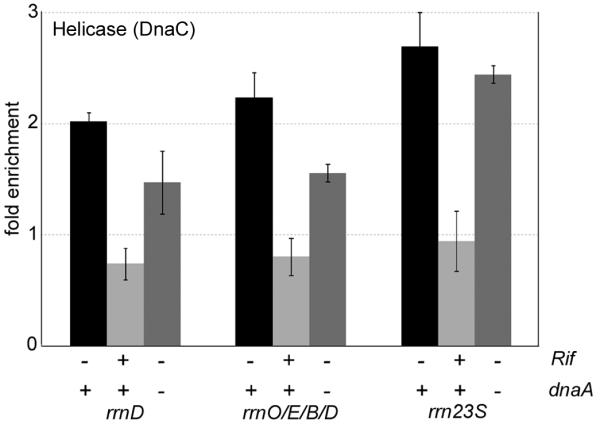

Even though co-directional conflicts between replication and transcription are not thought to be deleterious to replication2,4-7, the association of DnaD and DnaB with rrn loci is most likely due to replication fork stalling and restart. If true, then this association should depend on transcription, and the replicative helicase should also be associated with rrn loci. There was a decrease in association of DnaD (Fig. 3a) and DnaB (Fig. 3b) with rrn loci after inhibition of transcription initiation with rifampicin (which blocks RNAP at the promoter). In addition, the replicative helicase was associated with rrn loci during rapid growth (Fig. 4), and this association also decreased following treatment with rifampicin (Fig. 4). Using strains in which replication initiates from an ectopic origin inserted near oriC to maintain proper orientation of transcription and replication (Supplementary Discussion), we found that association of helicase at the rrn loci was independent of DnaA and replication initiation from oriC (Fig. 4). Together, these results support the hypothesis that association of helicase, DnaD, and DnaB with the rrn loci is a consequence of replication fork stalling and restart due to co-directional conflicts between replication and transcription. These results, and the finding that association of DnaD, DnaB, and helicase with the rrn loci was dependent on rapid growth, indicate that a high density of elongating RNAP molecules cause replication fork stalling and restart. We estimate that there are at least 40, and more likely >100, RNAP molecules per rRNA operon in B. subtilis during rapid growth (Supplementary Discussion).

Fig. 4.

Association of the replicative helicase with rrn loci depends on transcription and is independent of dnaA. Samples from wild type cells (AG174) with and without rifampicin (Rif) and a dnaA null mutant (AIG200) were grown and analysed as described for Fig. 3. Data are averages from at least three independent cultures. Error bars represent standard error. We also tested association of DnaB with the rrn loci using the 23S rrn probe and found similar association in the dnaA null mutant (data not shown).

The essential replication restart protein PriA was required for association of DnaD and DnaB with rrn loci (Fig. 3). PriA enables the resumption of replication at regions of replication fork collapse15-17,19,24-26. priA mutants interact genetically with mutations that affect RNAP progression and stability27,28, indicating a possible role for the restart machinery in resolving conflicts between transcription and replication in vivo. In a partially defective priA mutant (Methods), association of DnaD and DnaB with the rrn regions was reduced (Fig. 3). These results strongly support the conclusion that PriA, DnaD, and DnaB are functioning in replication restart at rRNA genes (Supplementary Fig. 1).

In vitro studies with purified E. coli proteins indicate that during both co-directional and head-on encounters between the replisome and RNAP, RNAP is displaced and the replisome resumes replication without coming off the DNA, without the need for replication restart proteins8,10. It is not clear if or how frequently this happens in vivo in rapidly growing cells where the replisome likely encounters multiple RNAP molecules aligned in tandem at highly transcribed genes4. Cells have mechanisms for removing RNAP to allow progression of replication forks13,14,27,29, thereby avoiding such conflicts.

Our findings indicate that in vivo, both head-on and co-directional encounters between replication and transcription can lead to replication fork stalling and recruitment of the helicase loading machinery. Head-on encounters are clearly more severe since inversion of rrn operons causes an appreciable slowing of replication4-6,9. Helicase loading machineries are likely utilized in all organisms to restart replication in regions of both head-on and co-directional transcription-replication conflicts. During these conflicts, the helicase will sometimes disengage from the template DNA, leaving behind a forked DNA substrate with a single stranded region on the lagging strand. PriA binds strongly to this type of substrate. This is likely followed by the sequential recruitment of B. subtilis DnaD and DnaB, and then DnaI-mediated loading the replicative helicase17 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

We estimate that ~5-10% of cells in an asynchronous population have a conflict between the transcription and replication machineries at a rRNA operon. This estimate is based on an ~50-100-fold greater association of helicase at oriC in a synchronous population at the time of replication initiation20 than at one of the ten rRNA operons, assuming that there are similar crosslinking efficiencies at oriC and rrn loci. The co-directional conflicts between replication and transcription likely account for a significant fraction of endogenous events requiring repair of stalled replication forks1,26, and may even account for some of the sensitivity to rapid growth conditions of priA mutants defective in replication restart25,30. Since inability to repair a stalled fork would prevent completion of a replication cycle and the production of viable progeny, there is strong selective pressure to avoid such catastrophes.

In conclusion, even though they are co-directionally aligned, highly transcribed rrn loci with a high occupancy by RNAP are natural obstacles for replication in vivo. This can cause replication fork stalling and/or collapse that leads to the intervention by the replication restart machinery (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Methods Summary

Strains are listed in the Supplementary Table. Relevant properties are described in the text. Strain constructions, growth conditions, and oligonucleotides are described in Methods. Standard procedures were used for ChIP experiments and are described (Methods). Full Methods and associated references are available in the online version at www.nature.com/nature.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Grainger, C. Lee, T. Baker, and W.K. Smits for discussions, W.K. Smits for constructing the priA-ssrA* mutant, and C. Lee, C. Bonilla, S.P. Bell, and J.D. Wang for comments on the manuscript.

Work in the P.S.’s lab was supported by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council grant BB/E006450/1 and a Wellcome Trust grant 091968/Z/10/Z. Work in A.D.G.’s lab was supported by NIH grant GM41934 and H.M. was supported in part by NIH postdoctoral fellowship GM093408. The Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and the Royal Society provided funds for a sabbatical visit of P.S. in A.D.G.’s lab.

Methods

Strains

B. subtilis strain 168 (trp) and derivatives of strain JH642 (trp phe) were used for all experiments (Supplementary Table) and were constructed by standard procedures31. The priA mutation was constructed by attaching an ssrA* tag onto the 3′-end of priA. ssrA* encodes a tag that makes the gene product unstable in the presence of the adaptor protein SspB32. A PCR product carrying a C-terminal fragment of priA was cloned into pKG1268 to give the plasmid pGCS-priA. This plasmid was introduced by single crossover into priA, generating priA-ssrA*, in strain KG1098 (amyE::{Pspank(-7TA)-sspB, spc}) that contains sspB under control of the weakened IPTG-inducible promoter Pspank(-7TA)32. The priA-ssrA* mutant (WKS338) was defective even in the absence of induction of SspB expression, likely because of the low level of expression without induction.

Media and growth conditions

For all experiments, cells were grown at 30°C and samples taken during mid-exponential phase. Growth was in either rich medium (LB) or LeMaster minimal medium33, prepared as follows: L-Ala 0.5 g, L-Arg(HCl) 0.58 g, L-Asp 0.41 g, L-Cysteine 0.03 g, L-Glu 0.67 g, L-Gly 0.54 g, L-His 0.06 g, L-Ile 0.23 g, L-Leu 0.23 g, L-Lys(HCl) 0.42 g, L-Met 0.5 g, L-Phe 0.13 g, L-Pro 0.10 g, L-Ser 2.08 g, L-Thr 0.23 g, L-Tyr 0.17 g, L-Val 0.23 g, adenine 0.5 g, guanosine 0.67 g, thymine 0.17 g, uracil 0.5 g, sodium acetate 1.50 g, succinic acid 1.50 g, ammonium chloride 0.75 g, sodium hydroxide 1.08 g, anhydrous K2HPO4.3H2O 8.0 g were suspended in one liter of dH2O and autoclaved. The pH of this pre-medium was checked and adjusted to ~7.5 if necessary. The final medium was completed by the addition of filtered-sterilized glucose (10 g/100 ml), MgSO4.7H2O (0.25 g/100 ml), FeSO4 (4.2 mg/100 ml), thiamine-HCl (5 mg/100 ml) and concentrated HCl (8 μl/100 ml).

ChIP-chip analysis

Polyclonal rabbit anti-DnaB and anti-DnaD antibodies were produced and tested as described34. Preparation of DNA samples for ChIP-chip analysis was carried out as described34 with minor modifications. An overnight culture of Bacillus subtilis (strain 168) was used to inoculate 800 ml of LB or LeMaster minimal medium. The culture was incubated at 30°C and during exponential growth (OD595 = 0.8) 1% v/v formaldehyde was added for 20 min to cross-link protein-DNA complexes. The reaction was quenched by 0.5 M glycine. Preparation of samples for microarray analysis was carried out as described34.

B. subtilis (strain 168) Agilent 4x44K ChIP arrays with AMADID 023001 were prepared by Oxford Gene Technologies (OGT) who also carried out array hybridizations and provided the final data. Each array comprised 41,770 probes in total, covering 4,185 genes. Each probe was 60 bp and generated using Agilent’s inkjet in-situ synthesis technology. The probes covered comprehensively the entire genome. They had an average spacing of ~100 bp with a maximum inter-probe distance of ~140 bp. The reference sample in the red (Cy5) channel was genomic B. subtilis (strain 168) DNA. Data analysis was carried out with a ChIP browser developed and supplied by OGT.

ChIP and quantitative real time PCRs

Cells were grown in LB medium at 30°C to mid-exponential phase. Samples were crosslinked as above and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against DnaD, DnaB and helicase (DnaC) were used as described previously20. Immunoprecipitations were done at room temperature for 2 hours with the antibody, followed by 1 hour with 3% protein A-sepharose beads.

The quantitative real time PCRs were performed as described 20. Primer pairs included: HM84 (5′-CAAGCTCACAGCGGCGGGAAAAT-3′) and HM85 (5′-GCCCTAGTTTGACTGACTACGC-3′) that amplify a sequence upstream of rrnD; HM43 (5′-CTGCACGACGCAGGTCACACAGGTG-3′) and HM44 (5′-CTCCCATCTGTCCGCTCGACTTGC-3′) that amplify sequences beginning upstream of rrnO, rrnE, rrnD, and rrnB and extending into the 16S rRNA gene; HM80 (5′-AGGATAGGGTAAGCGCGGTATT-3′) and HM81 (5′-TTCTCTCGATCACCTTAGGATTC-3′) that amplify sequences internal to all 23S rRNA genes.

yhaX is a chromosomal locus that does not have increased association with DnaD, DnaB, and helicase and was used for comparison. yhaX was detected with primers WKS145 (5′-CGAGCAAGGTGTCGCTTA-3′) and WKS146 (5′-GCAGGCGGTCATCATGTA-3′).

qRT-PCRs were quantified by comparison of the crossing point values generated in the PCR for each sample to standard curves generated for that primer set using chromosomal DNA as template. Data were first normalized to immunoprecipitations of yhaX, and then to gene copy number as determined by PCRs from “total” samples (lysates pre-immunoprecipitation). The final “fold enrichment” was determined as: (“x” IP/yhaX IP) / (“x” total/yhaX total), where “x” represents the region of interest. All data presented are the averages of at least 3 biological replicates ± standard error.

Footnotes

Author Information Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary Information contains and additional figures, a table, and discussion.

References

- 1.Mirkin EV, Mirkin SM. Replication fork stalling at natural impediments. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71:13–35. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00030-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pomerantz RT, O’Donnell M. What happens when replication and transcription complexes collide? Cell Cycle. 2010;9:2537–2543. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.13.12122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rocha EP. The replication-related organization of bacterial genomes. Microbiology. 2004;150:1609–1627. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26974-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.French S. Consequences of replication fork movement through transcription units in vivo. Science. 1992;258:1362–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.1455232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olavarrieta L, Hernandez P, Krimer DB, Schvartzman JB. DNA knotting caused by head-on collision of transcription and replication. J Mol Biol. 2002;322:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00740-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirkin EV, Mirkin SM. Mechanisms of transcription-replication collisions in bacteria. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:888–895. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.3.888-895.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirkin EV, Castro Roa D, Nudler E, Mirkin SM. Transcription regulatory elements are punctuation marks for DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7276–7281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601127103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pomerantz RT, O’Donnell M. The replisome uses mRNA as a primer after colliding with RNA polymerase. Nature. 2008;456:762–766. doi: 10.1038/nature07527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srivatsan A, Tehranchi A, MacAlpine DM, Wang JD. Co-orientation of replication and transcription preserves genome integrity. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pomerantz RT, O’Donnell M. Direct restart of a replication fork stalled by a head-on RNA polymerase. Science. 2010;327:590–592. doi: 10.1126/science.1179595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudolph CJ, Dhillon P, Moore T, Lloyd RG. Avoiding and resolving conflicts between DNA replication and transcription. DNA Repair (Amst) 2007;6:981–993. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JD, Berkmen MB, Grossman AD. Genome-wide coorientation of replication and transcription reduces adverse effects on replication in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5608–5613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608999104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tehranchi AK, et al. The transcription factor DksA prevents conflicts between DNA replication and transcription machinery. Cell. 2010;141:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boubakri H, de Septenville AL, Viguera E, Michel B. The helicases DinG, Rep and UvrD cooperate to promote replication across transcription units in vivo. EMBO J. 2010;29:145–157. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heller RC, Marians KJ. Replisome assembly and the direct restart of stalled replication forks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:932–943. doi: 10.1038/nrm2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruand C, Farache M, McGovern S, Ehrlich SD, Polard P. DnaB, DnaD and DnaI proteins are components of the Bacillus subtilis replication restart primosome. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:245–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsin S, McGovern S, Ehrlich SD, Bruand C, Polard P. Early steps of Bacillus subtilis primosome assembly. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45818–45825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101996200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rokop ME, Auchtung JM, Grossman AD. Control of DNA replication initiation by recruitment of an essential initiation protein to the membrane of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:1757–1767. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruand C, et al. Functional interplay between the Bacillus subtilis DnaD and DnaB proteins essential for initiation and re-initiation of DNA replication. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1138–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smits WK, Goranov AI, Grossman AD. Ordered association of helicase loader proteins with the Bacillus subtilis origin of replication in vivo. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75:452–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06999.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imai Y, et al. Subcellular localization of Dna-initiation proteins of Bacillus subtilis: evidence that chromosome replication begins at either edge of the nucleoids. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:1037–1048. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meile JC, Wu LJ, Ehrlich SD, Errington J, Noirot P. Systematic localisation of proteins fused to the green fluorescent protein in Bacillus subtilis: identification of new proteins at the DNA replication factory. Proteomics. 2006;6:2135–2146. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kunst F, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGlynn P, Al-Deib AA, Liu J, Marians KJ, Lloyd RG. The DNA replication protein PriA and the recombination protein RecG bind D-loops. J Mol Biol. 1997;270:212–221. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polard P, et al. Restart of DNA replication in Gram-positive bacteria: functional characterisation of the Bacillus subtilis PriA initiator. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1593–1605. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabbai CB, Marians KJ. Recruitment to stalled replication forks of the PriA DNA helicase and replisome-loading activities is essential for survival. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trautinger BW, Jaktaji RP, Rusakova E, Lloyd RG. RNA polymerase modulators and DNA repair activities resolve conflicts between DNA replication and transcription. Mol Cell. 2005;19:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahdi AA, Buckman C, Harris L, Lloyd RG. Rep and PriA helicase activities prevent RecA from provoking unnecessary recombination during replication fork repair. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2135–2147. doi: 10.1101/gad.382306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guy CP, et al. Rep provides a second motor at the replisome to promote duplication of protein-bound DNA. Mol Cell. 2009;36:654–666. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nurse P, Zavitz KH, Marians KJ. Inactivation of the Escherichia coli priA DNA replication protein induces the SOS response. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6686–6693. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.21.6686-6693.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 31.Harwood CR, Cutting SM. Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffith KL, Grossman AD. Inducible protein degradation in Bacillus subtilis using heterologous peptide tags and adaptor proteins to target substrates to the protease ClpXP. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70:1012–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LeMaster DM, Richards FM. 1H-15N heteronuclear NMR studies of Escherichia coli thioredoxin in samples isotopically labeled by residue type. Biochemistry. 1985;24:7263–7268. doi: 10.1021/bi00346a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grainger WH, Machon C, Scott DJ, Soultanas P. DnaB proteolysis in vivo regulates oligomerization and its localization at oriC in Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2851–2864. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.