Abstract

Homeostatic signaling systems stabilize neural function through the modulation of neurotransmitter receptor abundance, ion channel density and presynaptic neurotransmitter release. Molecular mechanisms that drive these changes are being unveiled. In theory, molecular mechanisms may also exist to oppose the induction or expression of homeostatic plasticity, but these mechanisms have yet to be explored. In an ongoing electrophysiology-based genetic screen we have tested 162 new mutations for genes involved in homeostatic signaling at the Drosophila NMJ. This screen identified a mutation in the rab3-GAP gene. We show that Rab3-GAP is necessary for the induction and expression of synaptic homeostasis. We then provide evidence that Rab3-GAP relieves an opposing influence on homeostasis that is catalyzed by Rab3 and which is independent of any change in NMJ anatomy. These data define new roles for Rab3-GAP and Rab3 and uncover a mechanism, acting at a late stage of vesicle release, that opposes the progression of homeostatic plasticity.

INTRODUCTION

Throughout the nervous system there is evidence that homeostatic signaling systems can modulate synaptic transmission or neuronal excitability and thereby stabilize neural function (Davis, 2006; Marder and Goaillard, 2006; Turrigiano, 2008). It is now widely hypothesized that defective homeostatic signaling may contribute to the cause or progression of diverse neurological disease. Maladaptive homeostatic signaling may participate in the progression of Alzheimer's Disease (Kamenetz et al., 2003) and post-traumatic epilepsy (Houweling et al., 2005), while impaired homeostatic signaling could reasonably contribute to other forms of epilepsy (Davis, 2006, for review) and complex neurological disease (Dickman and Davis, 2009). Ultimately, however, the involvement of homeostatic signaling in neural development and disease will require a molecular description of this form of neural plasticity.

A number of recent studies have identified molecules that when disrupted or deleted block the homeostatic control of neural function. For example, the secreted signaling molecules BDNF and TNF-alpha have both been shown to be necessary for a homeostatic increase in glutamate receptor abundance following prolonged activity blockade (Rutherford et al., 1997; Stellwagen and Malenka, 2006). Likewise, mechanisms that participate in the translation, trafficking or scaffolding of glutamate receptors have been shown to be required (Sutton and Schuman, 2006; Seeburg et al., 2008). At the Drosophila neuromuscular junction, a presynaptic signaling system that includes the Eph receptor, Ephexin, Cdc42 and presynaptic calcium channels has been implicated in the homeostatic control presynaptic neurotransmitter release (Frank et al., 2006; Frank et al., 2009). These are among a growing list of studies that have identified molecules that are necessary for the induction or execution of homeostatic signaling in the nervous system (Futai et al., 2007; Dickman and Davis, 2009).

To date, every molecule that has been identified normally functions to promote homeostatic change. In theory, homeostatic signaling systems will also require mechanisms that limit or oppose homeostatic compensation (Davis, 2006). However, in the nervous system, molecular mechanisms that limit or oppose homeostatic plasticity remain entirely unknown. In an ongoing, electrophysiology-based, forward genetic screen we have uncovered a presynaptic signaling system that participates in synaptic homeostasis and includes a mechanism to oppose the homeostatic increase of presynaptic neurotransmitter release.

At the NMJ of organisms ranging from Drosophila to human, decreased postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptor sensitivity elicits a homeostatic, compensatory increase in presynaptic transmitter release that precisely offsets the decrease in postsynaptic receptor function and, thereby, restores normal muscle depolarization (Davis, 2006). We previously reported a genetic screen, based upon synaptic electrophysiology at the Drosophila NMJ, designed to identify mutations that disrupt the homeostatic control of presynaptic release (Dickman and Davis, 2009). Here we report a continuation of this screen and identify the Rab3 GTPase-activating protein (Rab3-GAP) as an essential component involved in this homeostatic signaling system.

Rab3 and Rab3-GAP have been implicated in the modulation of presynaptic neurotransmitter release (Südhof, 2004; Sakane et al,. 2006). Rab3 is a small GTPase that is present in relatively high copy number on synaptic vesicles (Takamori et al., 2006). Only the GTP-bound form of Rab3 associates with the membrane of synaptic vesicles (Fischer von Mollard et al., 1990). In mammals the investigation of Rab3 function is complicated by the presence of four Rab3 paralogs (Rab3A-D), which are functionally redundant in mice (Schlüter et al., 2004b). Based on the finding that overexpression of either Rab3 or a constitutively active Rab3 decrease Ca2+-triggered exocytosis (Holz et al., 1994; Johannes et al., 1994; Chung et al., 1999; Iezzi et al., 1999; Schlüter et al., 2002), and that rab3A knockout mice release more transmitter quanta in response to stimulation (Geppert et al., 1997), it was initially suggested that Rab3 directly, or indirectly inhibits secretion (Schlüter et al., 2002). However, the generation of quadruple rab3A-D knockout mice uncovered a 30% decrease in synaptic vesicular release probability indicating that Rab3 might function, instead, to promote presynaptic release (Schlüter et al., 2004a; Schlüter et al., 2006). The examination of Rab3 function is greatly facilitated in Drosophila because there is only one predicted rab3 gene in fruit flies (Lloyd et al., 2000). At the Drosophila NMJ, Rab3 has been recently shown to be crucial for the organization of presynaptic active zone proteins including calcium channels (Graf et al., 2009).

Rab3-GAP is predicted to regulate the function of Rab3 by accelerating the hydrolysis of GTP-bound Rab3 to GDP-bound Rab3 (Fukui et al., 1997). Mutations in rab3-GAP cause Warburg Micro syndrome, an autosomal recessive disorder causing severe mental retardation (Aligianis et al., 2005). However, very little is known about the relevance of Rab3-GAP function during synaptic transmission. The only study that has investigated Rab3-GAP function in the context of synaptic transmission found altered short-term plasticity at hippocampal CA1 synapses of rab3-GAP mutant mice (Sakane et al., 2006). Here we define a novel role for Rab3-GAP and Rab3 during the homeostatic modulation of synaptic transmission and describe a form of negative regulation that acts to oppose the progression of synaptic homeostasis at a late stage of synaptic vesicle release.

RESULTS

An Electrophysiology-Based Forward Genetic Screen Identifies rab3-GAP

A rapid, homeostatic increase in presynaptic transmitter release can be observed at the Drosophila NMJ within 10 minutes following bath application of the glutamate receptor antagonist philanthotoxin-433 (PhTX; Frank et al., 2006). Previously, this assay was used as the basis for a forward genetic screen to isolate mutations that disrupt the rapid induction of synaptic homeostasis (Dickman and Davis, 2009). We have continued this screening strategy, testing the involvement of an additional 162 independent mutations. In brief, we generated a list of 450 genes that had been previously annotated as having enriched expression in the nervous system. From this list, we obtained mutations in 162 independent genes from the gene disruption project (the FlyBase Consortium), whenever possible selecting transposon insertions that reside within gene coding regions. For each of these 162 mutant lines, we recorded the amplitudes of spontaneous miniature EPSPs (mEPSPs) and action potential-evoked EPSPs following incubation of the NMJ in PhTX (10 μM) for 10 minutes (n≥4 NMJs per mutant, muscles 6 and 7, segment 2/3) (Fig. 1). We then assessed baseline synaptic transmission (EPSP and mEPSP in the absence of PhTX) in 73 mutant lines (n≥4 NMJs per mutant).

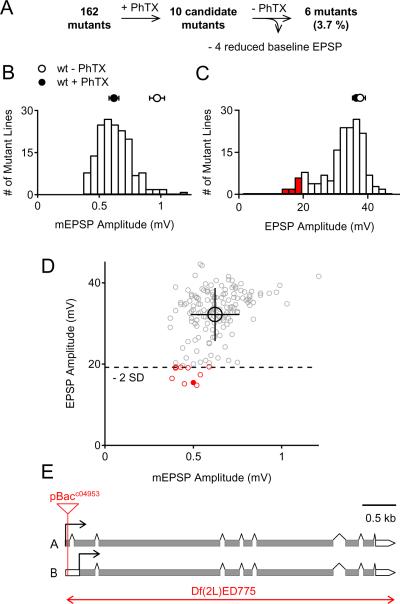

Figure 1. An Electrophysiology-Based Genetic Screen Identifies rab3-GAP as a Synaptic Homeostasis Mutant.

(A) Flow diagram of screen strategy and outcome.

(B) Histogram of mean mEPSP amplitude for each mutant line (n≥4 synapses per mutant, N=162 mutants) following PhTX treatment. The wild-type (wt) average mEPSP under baseline conditions (-PhTX, n=12), and after PhTX application (+PhTX, n=10) are shown as an open circle and a filled circle (+PhTX), respectively.

(C) Histogram of mean EPSP amplitude for each mutant line (n≥4 synapses per mutant, N=162 mutants) following PhTX treatment. The red bars highlight mutations that are 2 standard deviations smaller than the distribution mean. The average EPSP amplitude of wild-type synapses without PhTX (-PhTX, open white circle, n=12) and following PhTX incubation (+PhTX, filled circle, n=10) are also shown.

(D) EPSP amplitudes as a function of mEPSP amplitude following PhTX treatment. The average across all mutants is shown as a black open circle (± standard deviation). Red data points represent mutants with an EPSP amplitude two standard deviations smaller than the mean EPSP (− 2 SD; broken line indicates this cut-off). The data for the rab3-GAP mutant (pBacc04953, see E) is shown as a red filled circle.

(E) The Drosophila rab3-GAP locus on chromosome arm 2L at 33C1 – 33C2. Translated exons and untranslated exons of the two rab3-GAP isoforms (A and B) are shown as gray and white bars, respectively. The transposon insertion pBacc04953 resides in variant A, and in an untranslated 5' exon of variant B. The deficiency Df(2L)ED775 spans from 33B8 – 34A3. Scales are as indicated.

As shown in Figure 1B, the mean mEPSP amplitude after PhTX incubation, averaging across all mutants tested, was 0.62 ± 0.14 mV (N=162). This value is similar to the mean mEPSP amplitude seen in wild-type animals following PhTX incubation (0.62 ± 0.04 mV; n= 10; Fig. 1B, black circle, p=0.98) and is significantly smaller than the mean mEPSP amplitude recorded at wild-type NMJs in the absence PhTX (0.97 ± 0.06 mV; n=12; Fig. 1B, open circle, p<0.001). The mean EPSP amplitude after PhTX application was similar comparing mutant synapses (32.2 ± 6.5 mV; N= 162) and wild-type synapses (36.5 ± 1.2 mV; n=10, Fig. 1C, open circle; p=0.04). Thus, the majority of the mutant lines that we tested showed robust synaptic homeostasis, restoring EPSP amplitudes toward wild-type levels despite a large reduction in mEPSP amplitude in the presence of PhTX. However, 10 independent mutant lines had average EPSP amplitudes that were more than two standard deviations smaller than the distribution mean (Fig. 1C, red bars; Fig. 1D, red circles). These represent candidate mutations that may disrupt synaptic homeostasis.

Next, we explored the basis for the apparent block of synaptic homeostasis in these 10 candidate homeostatic mutations. First, we assayed synaptic transmission in the absence of PhTX for each of these ten mutations to ensure that the mutations did not simply disrupt neurotransmission. We uncovered defects in baseline transmission in 4 out of the 10 candidate homeostasis mutants (data not shown), leaving us with 6 mutant lines (3.7 %) that have a specific block in the rapid induction of synaptic homeostasis (Fig. 1A). Next, we sought to determine if there might have been false negatives in our screen. For example, if a mutation had increased baseline synaptic transmission relative to wild-type, failed homeostatic compensation following PhTX application would cause EPSP amplitudes to be reduced, but the reduction might result in an EPSP similar to that observed in wild-type. To assess this possibility, we assayed synaptic transmission in the absence of PhTX for 73 of the mutations, allowing us to compare each mutation with and without PhTX. We did not uncover any additional candidate homeostatic mutations, indicating that our false negative rate is quite low. These analyses also highlight the specificity of those mutations that we did identify as candidate homeostatic mutants. Of the 6 mutations that did show a strong block of synaptic homeostasis (Fig. 1D, red circles) one is a transposon insertion that resides in the Drosophila homolog of rab3-GAP (CG7061; Fig. 1D and E, filled red circle). This gene was selected for further analysis.

The Rapid Induction of Synaptic Homeostasis Is Blocked in rab3-GAP Mutants

The rab3-GAP mutation identified in our screen is a transposon insertion residing within an untranslated 5' exon (pBacc04953, henceforth called rab3-GAP; Fig. 1E). We find a significant 87±1 % (n=6 samples) decrease in mRNA levels in rab3-GAP compared to wild-type, indicating that the rab3-GAP transposon insertion is a loss-of-function allele (not shown). We then examined baseline synaptic transmission in rab3-GAP and find that the average mEPSP amplitude, EPSP amplitude, and quantal content do not differ from wild-type (mEPSP, p=0.4; EPSP, p=0.98; quantal content, p =0.18; Fig. 2). Throughout this study, average values are presented in figure format and sample sizes are reported in figure legends. For each data set, average values with associated sample sizes are also presented in Table S1. Thus, we conclude that there is no major defect in baseline synaptic transmission in a rab3-GAP loss-of-function allele.

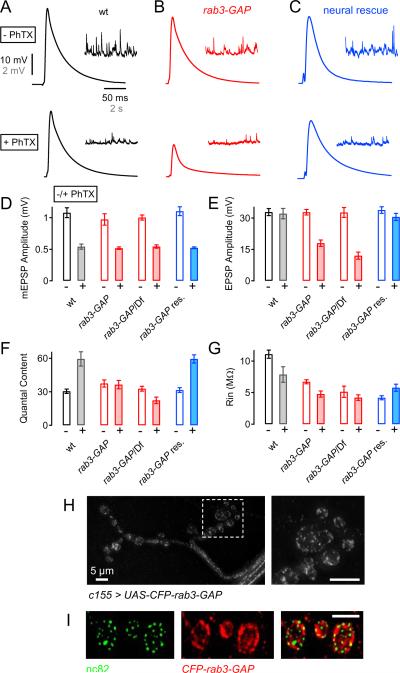

Figure 2. Presynaptic Rab3-GAP is Sufficient for the Induction of Synaptic Homeostasis.

(A – C) Representative EPSP (Y-scale: 10 mV, X-scale: 50 ms), and spontaneous mEPSP (Y-scale: 2 mV, X-scale: 2 s) traces recorded in the absence and presence of PhTX (− PhTX, + PhTX; top and bottom, respectively) at a wild-type NMJ (wt, A), a rab3-GAP mutant NMJ (B), and a rab3-GAP mutant NMJ in which UAS-CFP-rab3-GAP was driven using the pan-neuronal driver elav-GAL4 (C, `neural rescue').

(D – G) Average mEPSP amplitude (D), EPSP amplitude (E), quantal content (calculated as EPSP amplitude/mEPSP amplitude, F), and muscle input resistance (Rin, G). The following gentotypes are presented: wild-type synapses (− PhTX: n=12; + PhTX: n=8; white/gray bars), rab3-GAP mutant NMJs (− PhTX: n=16; + PhTX: n=16; red bars), rab3-GAP/Df synapses (− PhTX: n=9; + PhTX: n=13; red bars), and rab3-GAP mutant NMJs bearing a UAS-CFP-rab3-GAP rescue construct driven by elav-Gal4 (− PhTX: n=8; + PhTX: n=21; blue bars). PhTX challenge (−/+ PhTX) are shown as open and filled bars, respectively. The defect in homeostatic compensation was rescued by driving UAS-CFP-rab3-GAP using elav-GAL4 (blue bars, F).

(H) Image of an in vivo Drosophila NMJ (muscle 4, segment A2) in which UAS-CFP-rab3-GAP was overexpressed using the pan-neuronal driver elav-Gal4. The right image shows the bouton highlighted by the white box in the left image. Note that Rab3-GAP-CFP forms discrete puncta that are distributed throughout the presynaptic nerve terminal and the axon.

(I) Immunostaining against the active zone component Bruchpilot (anti-nc82, `nc82', green, left) and UAS-CFP-rab3-GAP (anti-GFP, `CFP-rab3-GAP', red, middle) of a fixed NMJ (muscle 4, segment A2) in which UAS-CFP-rab3-GAP was expressed using elav-Gal4.

Next we confirmed that rab3-GAP mutations disrupt the rapid induction of synaptic homeostasis. Bath application of 10 μM PhTX induced a significant decrease in mEPSP amplitude at both wild-type synapses (Fig. 2D, p<0.001) and rab3-GAP mutant synapses (Fig. 2D, p<0.001). Note that in all experiments p-values are based on the comparison of data collected for a single genotype in the presence versus absence of PhTX. At wild-type synapses, a significant increase in quantal content (Fig. 2F; p<0.001) offsets the decrease in postsynaptic mEPSP amplitude and restores EPSP amplitudes to baseline values. By contrast, in the rab3-GAP mutants, there is no homeostatic increase in quantal content following application of PhTX to the NMJ (Fig. 2F, p=0.85). As a consequence, EPSP amplitudes are significantly smaller in the rab3-GAP mutant following PhTX application compared to rab3-GAP mutants recorded in the absence of PhTX (Fig. 2E; p<0.001). A similar block of synaptic homeostasis was also observed when rab3-GAP was placed in trans to a deficiency [Df(2L)ED775] that uncovers the rab3-GAP locus (Fig. 1E). There is no apparent defect in baseline synaptic transmission in rab3-GAP/Df mutant animals (Fig. 2D–F). However, following PhTX application, the average mEPSP amplitude (p<0.001) and average EPSP amplitude (p<0.001) are significantly decreased in rab3-GAP/Df mutants and quantal content remains unchanged (Fig. 3F). These data confirm that the rapid induction of synaptic homeostasis is blocked in rab3-GAP mutants, and confirm that the rab3-GAP transposon insertion mutation is likely to be loss-of-function mutation in the rab3-GAP gene. It is worth emphasizing that the defect in synaptic homeostasis is not accompanied by a deficit in baseline synaptic transmission under standard recording conditions.

Figure 3. The Sustained Expression of Synaptic Homeostasis is Impaired in rab3-GAP Mutants.

(A – D) Representative EPSP and mEPSP traces from wild-type (A), rab3-GAP mutant (B), GluRIIASP16 mutant (C), and rab3-GAP, GluRIIASP16 double mutant synapses (D).

(E – H) Average mEPSP amplitude (E), EPSP amplitude (F), quantal content (G), and muscle input resistance (Rin, H) from wild-type (n=7; white bars), GluRIIASP16 mutants (n=11; gray bars), rab3-GAP mutants (n=6; bars outlined in red), rab3-GAP, GluRIIASP16 double mutants (n=15; red bars). The decrease in mEPSP amplitude induced a significant (p<0.001) increase in quantal content in GluRIIASP16 mutants (red bar, G) relative to wild-type (white bar, G). In contrast, there was no significant increase in quantal content in rab3-GAP, GluRIIASP16 double mutants (p=0.2; red bar, G) relative to rab3-GAP mutants (bar outlined in red, G), indicating that the sustained expression of synaptic homeostasis is blocked in the rab3-GAP, GluRIIASP16 double mutants.

Rab3-GAP Functions Presynaptically During the Induction of Synaptic Homeostasis

The rab3-GAP gene is ubiquitously expressed in both rats (Oishi et al., 1998), and Drosophila (Chintapalli et al., 2007), and is enriched in the synaptic, soluble fraction of rat brains (Oishi et al., 1998). Therefore, we hypothesize that Rab3-GAP acts presynaptically during synaptic homeostasis. To test this possibility, we generated a UAS-CFP-rab3-GAP transgene (CFP was placed at the N terminus of rab3-GAP cDNA; see Experimental Procedures), and expressed this transgene in the rab3-GAP mutant background using the pan-neuronal GAL4 driver line elav-GAL4. As shown in Figs. 2C and 2F, a homeostatic increase in presynaptic quantal content (p<0.001) is observed following application of PhTX to the rab3-GAP mutant expressing the UAS-CFP-rab3-GAP transgene. The observed increase in quantal content offsets the PhTX-dependent decrease in mEPSP amplitude (p<0.001; Fig. 2D) and restores EPSP amplitudes to baseline values (p=0.28, comparing EPSP amplitude with, and without PhTX; Fig. 2E). Thus, presynaptic expression of UAS-CFP-rab3-GAP rescues synaptic homeostasis in the rab3-GAP mutant background. These data support the conclusion that presynaptic rab3-GAP is sufficient for the rapid induction of synaptic homeostasis.

It should be noted that the input resistance of rab3-GAP mutant muscles is significantly smaller than that observed in wild-type muscles (Fig. 2G, red bars). However, the defect in input resistance persists in the rab3-GAP rescue animals even though synaptic homeostasis is fully restored. Thus, this effect cannot be the cause of impaired synaptic homeostasis in the rab3-GAP mutant. The cause of impaired muscle input resistance could represent a genetically separable postsynaptic function of rab3-GAP. We also controlled for the possibility that overexpression of Rab3-GAP levels might influence baseline synaptic transmission and synaptic homeostasis. Therefore, we overexpressed UAS-CFP-rab3-GAP in a wild-type background and found no difference in synaptic homeostasis with respect to control (Figure S1) and a slight, statistically significant, decrease in evoked neurotransmitter release (p=0.04; Figure S1). Thus, elevated Rab3-GAP levels do not cause an increase in neurotransmitter release during basline conditions or after a homeostatic challenge.

To investigate where Rab3-GAP localizes within the presynaptic neuron, we imaged CFP-Rab3-GAP in larvae expressing UAS-CFP-rab3-GAP under the control of the elav-GAL4 driver. Ectopically expressed CFP-Rab3-GAP forms small puncta that are distributed throughout the axon and presynaptic nerve terminal in vivo (Fig. 2H). Within individual synaptic boutons, CFP-Rab3-GAP appears to concentrate at or near the presynaptic plasma membrane. We also show that UAS-CFP-rab3-GAP is resides in close proximity to active zones by co-labeling with the active zone marker Brp (Figure 1I). Since the UAS-CFP-rab3-GAP transgene is sufficient to rescue synaptic homeostasis, we propose that this distribution reflects, at least in part, the sites at which Rab3-GAP normally functions within the presynaptic nerve terminal, where it could participate in the modulation of transmitter release during synaptic homeostasis (Fig. 2H).

Rab3-GAP is Required for the Sustained Expression of Synaptic Homeostasis

We next asked whether Rab3-GAP is also required for the sustained expression of synaptic homeostasis. To do so, we generated double-mutant flies harboring mutations in both rab3-GAP and GluRIIA, a subunit of the muscle-specific ionotropic glutamate receptors present at the Drosophila NMJ (Petersen et al., 1997). As shown previously, the GluRIIASP16 mutation causes a significant decrease in mEPSP amplitude compared to wild-type (Fig. 3A, C, and E; p<0.001) (Petersen et al., 1997; Frank et al., 2006; Frank et al., 2009). This decrease in mEPSP amplitude is offset by a pronounced increase in quantal content (Fig. 3G, white and gray bar; p<0.001) that restores EPSP amplitudes to wild-type values (Fig. 3A, C, and F, white and gray bar; p=0.8). Because this perturbation persists throughout larval development, this effect has been interpreted as the persistent expression of synaptic homeostasis (Frank et al., 2006).

We then examined GluRIIASP16, rab3-GAP double mutants. In these double mutants, the mEPSP amplitudes are significantly reduced compared to rab3-GAP mutant synapses alone (Fig. 3B, D, and E; p<0.001). However, there is no significant change in presynaptic quantal content at GluRIIASP16, rab3-GAP double mutant synapses (Fig. 3G, filled red bar) compared to rab3-GAP control synapses (Fig. 3G, red open bar; p=0.2). As a consequence, the mean EPSP amplitude of GluRIIASP16, rab3-GAP double mutant NMJs (Fig. 3F) is significantly smaller than the EPSP amplitude recorded in rab3-GAP mutants alone (Fig. 3B, D, and F; p<0.001). Based upon these data, we conclude that the rab3-GAP mutation blocks synaptic homeostasis in the GluRIIA mutant background. By extension, we conclude that rab3-GAP is necessary for both the rapid induction and the sustained expression of synaptic homeostasis at the Drosophila NMJ.

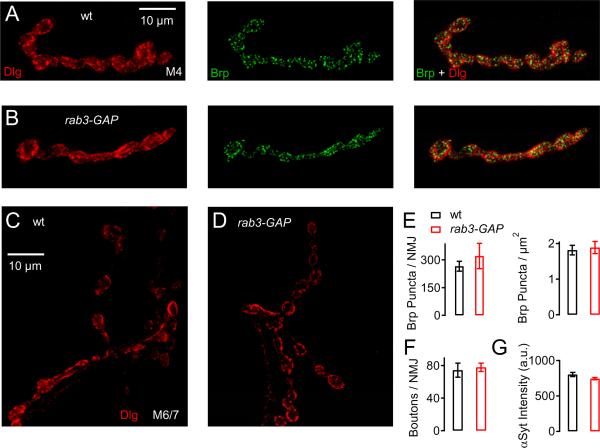

Synaptic Morphology is Normal in rab3-GAP Mutants

In principle, the defect in synaptic homeostasis seen in rab3-GAP animals could be due to altered synapse development. This is a particular concern given the recent demonstration that rab3 mutations cause a dramatic change in synaptic development at the Drosophila NMJ (Graf et al., 2009). However, the absolute number of active zones per NMJ as assayed by immunostaining against the active zone component Bruchpilot (Brp) in rab3-GAP (321 ± 68, n=6; Fig. 4E, left) is not significantly different when compared to wild-type (267 ± 24, n=6, p=0.47). We also quantified the density of active zones per NMJ area by normalizing the number of Brp puncta to synapse area, which was assessed by co-staining with an antibody recognizing the postsynaptic protein Discs-large (Dlg, Fig. 4A, 4B, red). We found no apparent difference in active zone density comparing the rab3-GAP mutant (1.89 ± 0.17, n=9, Fig. 4E, right) with wild-type NMJs (1.81 ± 0.13, n=7, p=0.7). We next probed the absolute number of boutons per NMJ at muscle 6/7. We find that bouton number did not differ between rab3-GAP (78 ± 5, n=9; Fig. 4D, 4F) and wild-type (74 ± 9, n=7, Fig. 4C, 4F; p=0.71). We also asked whether there was a change in the abundance of the synaptic vesicle protein Synaptotagmin 1 (anti-Syt). We did not detect a significant difference in anti-Syt intensity between rab3-GAP (745 ± 16 a.u., n=9; Fig. 4G) and wild-type (803 ± 29 a.u., n=9; p=0.06). Finally, there was also no apparent change in the level and the distribution of Rab3 based on immuno-staining against Rab3 (Figure S2). Thus, the disruption of synaptic homeostasis is unlikely to be a secondary consequence of impaired anatomical development or active zone number, or a change in level or distribution of Rab3 at the NMJ. This is in agreement with our finding that Rab3-GAP mutations show normal baseline synaptic transmission.

Figure 4. Normal Morphology of rab3-GAP Mutant NMJs.

(A and B) Representative images of NMJs from wild-type (top row) and rab3-GAP (bottom row) at muscle 4 (M4). The NMJ are co-labeled with antibodies against postsynaptic discs large (Dlg, red, left images) and presynaptic Bruchpilot (nc82, green, middle).

(C and D) Discs-large staining of a wild-type (left) and a rab3-GAP mutant NMJ (right) of muscles 6/7 in abdominal segment 2.

(E) Average number of nc82 (Brp) puncta per NMJ (left), and per synapse area (right) in wild-type (black bars, n=7), and rab3-GAP mutant NMJs (red bars, n=9) at muscle 4. There is no significant difference in active zone number (p= 0.47), or active zone density (p= 0.7).

(F) Average number of boutons in wild-type (black bars, n=7), and rab3-GAP NMJs (red bars; n=9) at muscles 6/7 in abdominal segment 2. There is no significant difference in bouton number (p= 0.7).

(G) Average intensity of synaptotagmin immunostaining (αSyt) in wild-type (black bars, n=9), and rab3-GAP (red bars, n=9) at muscle 4. There is no difference in anti-Syt intensity (p=0.06).

Evidence for Altered Neurotransmitter Release at rab3-GAP Mutant Synapses

We have established that baseline synaptic transmission in response to a single action potential, under standard recording conditions, is unaltered in rab3-GAP mutants (Figs. 2, 3). Synaptic homeostasis is achieved by an increase in transmitter release probability in response to a single action potential in the same standard recording conditions. Somehow, the mutation in rab3-GAP prevents this homeostatic increase in release probability. To identify a function for Rab3-GAP that might be related to the homeostatic modulation of release probability, we tested baseline synaptic transmission under a variety of different stimulation protocols and extracellular calcium concentrations. As exemplified in Figures 5A and 5B, a 20-Hz stimulus train induced synaptic depression in both wild-type (Fig. 5A) and rab3-GAP mutants (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, the average steady-state EPSP amplitude was slightly, but statistically significantly larger at rab3-GAP synapses as compared to wild-type (Fig. 4C; p<0.001). As reported earlier (Fig. 2, 3), there was no significant difference in the EPSP amplitude elicited by the first stimulus of a train between rab3-GAP mutants and wild-type (Fig. 5C; p=0.72). This shows that rab3-GAP mutant synapses exhibit less synaptic depression. Interestingly, these data are consistent with what has been observed at central synapses in rab3-GAP knockout mice (Sakane et al., 2006). We can conclude that the defect in synaptic homeostasis is not secondary to a defect in the recycling of the releasable pool of synaptic vesicles.

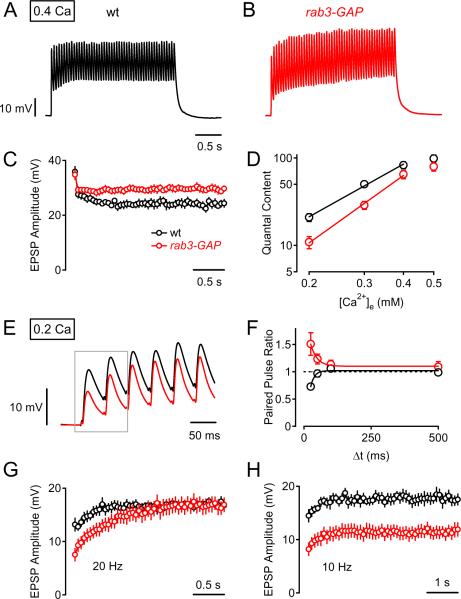

Figure 5. Short-Term Dynamics and Ca2+ Cooperativity of Release at rab3-GAP Mutant Synapses.

(A and B) Representative EPSP trains from a wild-type NMJ (black) and rab3-GAP (red) in response to 20-Hz stimulation (50 stimuli) in 0.4 mM extracellular calcium.

(C) Average EPSP amplitudes (20-Hz stimulation, 50 stimuli, n=6) for wild-type (black) and rab3-GAP synapses (red, n=8). 20-Hz stimulation induces significantly less depression in rab3-GAP mutants (steady-state EPSP amplitude in response to the last 10 stimuli: 85 ± 4% of the first EPSP amplitude) compared to wild-type (67 ± 2% of the first EPSP; p<0.001).

(D) Quantal content of single AP-evoked EPSPs for wild-type (black) and rab3-GAP at different extracellular Ca2+ concentrations, [Ca2+]e . Quantal content values were corrected for nonlinear summation (see Experimental Procedures). Logarithmized data were fit with a line that is superimposed. Note that the quantal content of rab3-GAP is significantly smaller than wild-type at low extracellular [Ca2+]e concentrations (0.2 and 0.3mM, p<0.001 compared to wild-type at each concentration).

(E) Representative EPSPs elicited by the first six stimuli of a 20 Hz train at a [Ca2+]e of 0.2 mM for rab3-GAP (red) and wild-type (black).

(F) Paired-pulse ratio (ratio between the second and the first EPSP amplitude, see gray box in E) as a function of inter-stimulus interval (Δt) for wild-type (n=9, black) and rab3-GAP (n=11, red) at 0.2 mM [Ca2+]e. Data of the respective genotype were fit with an exponential function.

(G and H) Average EPSP amplitudes in response to 20-Hz stimulation (G) and 10-Hz stimulation (H) (50 stimuli) at 0.2 mM [Ca2+]e of n=9 wild-type synapses (black data), and n=11 rab3-GAP mutant synapses (red data). Note that EPSP amplitudes of rab3-GAP mutants are smaller than wild-type EPSPs in response to the first (~20) stimuli of the 20-Hz train, and that mutant EPSP amplitudes reach wild-type levels thereafter (G). In contrast, during 10-Hz stimulation, rab3-GAP mutant EPSP amplitudes remain significantly smaller than wild-type (H).

We next assayed synaptic transmission at a range of different extracellular calcium concentrations [Ca2+]e (Fig. 5D). When quantal content in rab3-GAP (red) and wild-type (black) are plotted as a function of [Ca2+]e (Fig. 5D), we find a defect in synaptic transmission that is revealed primarily at lower extracellular calcium concentrations. Whereas quantal content at 0.5 mM [Ca2+]e is not different from wild-type (p=0.15), quantal content is significantly decreased at 0.2 mM [Ca2+]e in rab3-GAP (p<0.001). This effect translates into a change in the apparent Ca2+ cooperativity of transmitter release (Fig. 5D).

To further explore the defect in synaptic transmission that was uncovered at low [Ca2+]e, we tested short-term plasticity at low [Ca2+]e by stimulating the presynaptic axon repetitively at various inter-stimulus intervals (0.2 mM [Ca2+]e). Figure 5E shows a representative response from rab3-GAP (red trace) and wild-type (black trace) during the first six stimuli of a 20-Hz train at low [Ca2+]e. Average paired-pulse ratios, calculated as the ratio between the first two EPSP amplitudes (EPSP2/EPSP1) of each stimulus train, are plotted for a range of inter-stimulus intervals (Figure 5F). At the shortest inter-stimulus interval tested (25 ms), the average paired-pulse ratio seen in rab3-GAP facilitated (1.5 ± 0.2; n=9; Fig. 5F, red data), while wild-type synapses showed depression (0.73 ± 0.03; Fig. 5F, n=7; black data, p=0.005). With increasing inter-stimulus interval the paired-pulse facilitation seen in rab3-GAP decayed exponentially with a time constant of 24 ms (Fig. 5F, red exponential fit) reaching the paired-pulse ratio of wild-type at an interval of 100 ms. It is generally observed that the paired-pulse ratio is inversely related to transmitter release probability. Thus, our results indicate that there is a decrease in presynaptic release probability at rab3-GAP mutant synapses that is revealed at low extracellular calcium concentrations. Our results are, again, similar to what has been observed at CA1 synapses of rab3-GAP mouse mutants, which show an increase in paired-pulse facilitation (Sakane et al., 2006).

Finally, we observe that the difference in EPSP amplitude between rab3-GAP and wild-type becomes less pronounced during the course of a 20-Hz stimulus train at low [Ca2+]e (Fig. 5E and G). On average, the EPSP amplitude of rab3-GAP mutants, which is significantly smaller in response to the first few stimuli, reaches the level of wild-type EPSPs after approximately the first 20–25 stimuli of a 20-Hz train (Fig. 5G). In contrast, rab3-GAP mutant EPSPs remain significantly smaller than the amplitude of wild-type EPSPs if the stimulation frequency is reduced to 10 Hz (Fig. 5H). Therefore, the initial small EPSP amplitude of rab3-GAP mutants at low [Ca2+]e can reach wild-type levels if the mutant synapses are stimulated at a high frequency (20 Hz). Based on the decay of the presynaptic AP-evoked spatially averaged Ca2+ transient at the Drosophila NMJ (tau ~ 100 ms; Lnenicka et al., 2006), this might indicate that the rab3-GAP mutants are capable of sustaining high levels of synaptic vesicle release if intra-terminal Ca2+ levels rise during a stimulus train.

At one level, the changes in baseline transmission that we detect in rab3-GAP are not dramatic. We observe changes in short-term plasticity, but the NMJ can sustain release during a 20-Hz train. Thus, the loss of synaptic homeostasis in the rab3-GAP mutant is unlikely to be due to a major defect in the release mechanism. However, the types of changes that we observe may inform us regarding rab3-GAP activity during homeostatic plasticity. For example, we find that a defect in release probability that is revealed only at low extracellular calcium concentrations and this effect is masked during a stimulus train when intracellular calcium concentrations increase. We speculate that this defect in release probability is directly related to impaired homeostatic modulation of presynaptic release probability. One possibility is that the activity of Rab3-GAP is necessary to position vesicles close to the presynaptic calcium channels. It is possible that this action is required for any subsequent homeostatic modulation of release probability (see discussion). Irrespective of the exact mechanisms by which Rab3-GAP is regulating synaptic transmission, we have shown that Rab3-GAP is required for homeostatic plasticity at the Drosophila NMJ (Fig. 2 and 3). The role of Rab3-GAP in synaptic transmission has remained largely elusive, and the effects of rab3-GAP mutations on baseline synaptic transmission are relatively subtle in both mice (Sakane et al., 2006) and Drosophila (this study). Thus, we now define a new role for Rab3-GAP in the homeostatic modulation of vesicle release.

Synaptic Homeostasis is Normal in rab3 Mutants

Drosophila Rab3-GAP is predicted to regulate the function of the small GTPase Rab3 (Lloyd et al., 2000). Assuming that Rab3-GAP acts on Rab3, we considered two major possibilities for how Rab3-GAP might regulate synaptic homeostasis. First, Rab3-GAP-dependent hydrolysis of Rab3-GTP might be a required catalytic step for synaptic homeostasis. If this hypothesis is true, then Rab3 should also be required for synaptic homeostasis. A second possibility is that Rab3-GAP normally relieves an opposing effect of Rab3-GTP on homeostasis by inactivating Rab3. In this case, Rab3 would be a negative regulator of homeostasis and mutations in rab3 might not disrupt synaptic homeostasis. To this point, our morphological data and our electrophysiological data favor the latter possibility. First, loss of rab3-GAP does not lead to a change in synapse morphology (Fig. 4), while loss of rab3 causes an unmistakable change in active zone size and distribution within the presynaptic terminal (Graf et al., 2009). Second, we show that rab3-GAP mutant synapses have a slightly lower release probability at low extracellular calcium (Fig. 5), while there is an increase in release probability at rab3 mutant NMJs (Graf et al., 2009).

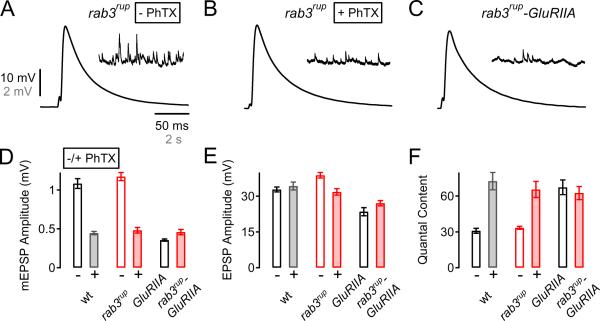

We therefore investigated synaptic homeostasis in a recently characterized rab3 mutant (rab3rup; Graf et al., 2009). As shown in Figure 6, the average mEPSP (Fig. 6A, 6D) and EPSP amplitudes (Fig. 6A, 6E) as well as quantal content (Fig. 6F) were similar to wild-type (p>0.05) confirming that synaptic efficacy in response to single APs is normal in rab3 mutants (see Graf et al., 2009). We then challenged the rab3rup mutant with PhTX incubation, causing a significant decrease in mEPSP amplitude with respect to control (Fig. 6B, 6D; p<0.001). In the rab3rup mutant, following application of PhTX, we find a robust increase in quantal content (Fig. 6F, p<0.001) that restores EPSP amplitudes toward wild-type (Fig. 6E, p<0.001). Although EPSP amplitudes remain significantly smaller than baseline, this difference is relatively small and there is a pronounced, significant increase in quantal content indicative of a clear homeostatic increase in presynaptic release (Fig. 6F). We next assessed whether a prolonged homeostatic challenge imposed by a mutation in the GluRIIA subunit would affect synaptic homeostasis in the rab3 mutant. We therefore generated rab3rup-GluRIIASP16 double mutants and find a robust, homeostatic increase in transmitter release in the double mutant that is similar to the one seen in GluRIIA mutants alone (Fig. 6C – F). This demonstrates that the sustained expression of synaptic homeostasis is unaffected in a rab3 mutant. We conclude that Rab3 is not required for the rapid induction or the sustained expression of synaptic homeostasis.

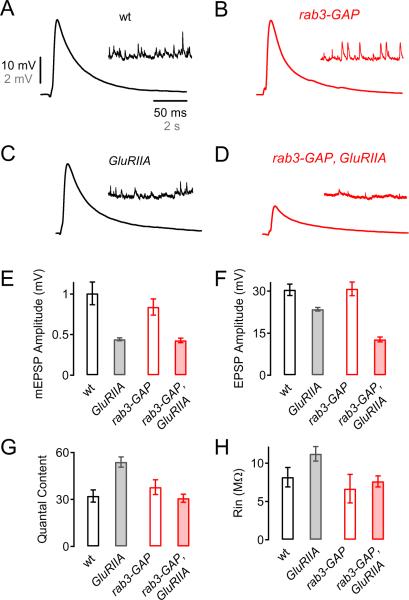

Figure 6. Normal Synaptic Homeostasis in rab3rup Mutants.

(A – C) Representative EPSP and mEPSPs from rab3rup mutant NMJs recorded in the absence or presence of PhTX (−PhTX, A; +PhTX, B), and from a rab3rup-GluRIIASP16 double mutant (C).

(D – F) Average mEPSP amplitude (D), EPSP amplitude (E), and quantal content (F) from wild-type (− PhTX: n=6; + PhTX: n=10; white/gray bars), rab3rup (− PhTX: n=18; + PhTX: n=12; open/filled red bars), GluRIIASP16 (n=9; open black bars), and rab3rup-GluRIIASP16 double mutants (n=16; filled red bar). Note that PhTX induces a significant decrease in mEPSP amplitude (D), and a significant increase in quantal content in both wild-type (p<0.001) and rab3rup with respect to control (p<0.001, F). Similarly, the GluRIIASP16 mutation decreased mEPSP amplitude (D), and increased quantal content in both GluRIIASP16 mutants compared to wild type without PhTX (F, p<0.001), and rab3rup-GluRIIASP16 double mutants compared to rab3rup without PhTX (F, p<0.001).

Rab3 is the Effector GTPase for Rab3-GAP during Synaptic Homeostasis

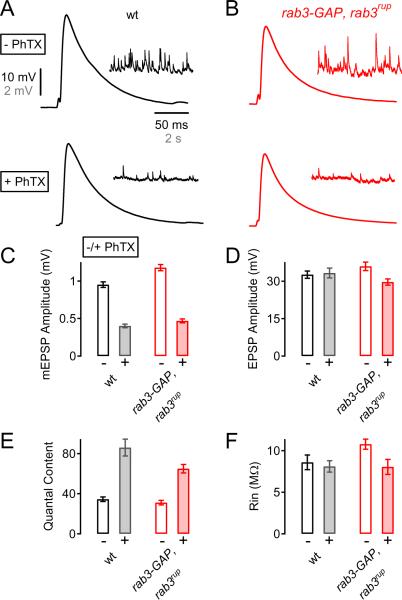

The observation that synaptic homeostasis is normal in a rab3 mutant could mean that Rab3-GAP controls synaptic homeostasis via a small GTPase other than Rab3 (Tcherkezian and Lamarche-Vane, 2007). To test this possibility, we generated double mutants of rab3-GAP and rab3rup. The presence of the rab3-GAP transposon insertion in the double mutant was unambiguous based on the presence of the mini-white gene in the w- background of the rab3rup mutation. A defect in synaptic homeostasis in the double mutant would indicate that Rab3-GAP does not function with Rab3 during homeostasis, while normal homeostasis would imply that Rab3 is the effector GTPase of Rab3-GAP. As shown in Figure 7, PhTX incubation causes a significant decrease in mEPSP amplitude in rab3-GAP–rab3rup double mutants (p<0.001; Fig. 7C). We find a significant, nearly 2-fold, increase in quantal content following PhTX-treatment in rab3-GAP–rab3rup double mutants (Fig. 7E) compared to controls (p<0.001). Thus, rab3-GAP–rab3rup double mutants undergo synaptic homeostasis. Finally, rab3-GAP–rab3rup mutant synapses also did not exhibit major defects in baseline transmission (mEPSP, p=0.002; EPSP, p=0.21; quantal content, p=0.32; all p-values compare wild-type to the rab3-GAP–rab3rup double mutant). The presence of synaptic homeostasis in rab3-GAP–rab3rup double mutants is consistent with Rab3-GAP acting upon Rab3 during synaptic homeostasis. Furthermore, in genetic terms, these data are consistent with the interpretation that Rab3 functions, directly or indirectly, to oppose the induction or expression of synaptic homeostasis. The action of Rab3-GAP would then be to relieve Rab3-dependent opposition and allow homeostatic plasticity to proceed.

Figure 7. Normal Synaptic Homeostasis in rab3-GAP–rab3rup Double Mutants.

(A and B) Representative EPSP and mEPSPs for wild-type (A), and rab3-GAP–rab3rup double mutant (B), recorded in the absence or presence of PhTX (− PhTX, +PhTX; top and bottom, respectively).

(C – F) Average mEPSP amplitude (C), EPSP amplitude (D), quantal content (E), and muscle input resistance (F) of wild-type (− PhTX: n=5; + PhTX: n=7; white/gray bars), and rab3-GAP–rab3rup double mutant NMJs (− PhTX: n=10; + PhTX: n=15; open/filled red bars). PhTX application significantly decreased mEPSP amplitude relative to control in both genotypes (C, both genotypes p<0.001), and induced a significant increase in quantal content with respect to control in both wild-type (p<0.001) and rab3-GAP–rab3rup double mutants (E, p<0.001).

We also examined synapse morphology in the rab3-GAP–rab3rup double mutants. The rab3-GAP mutant has no defect in synapse development (Fig. 4), whereas the rab3rup mutant shows a dramatic change in synapse organization and active zone size (Graf et al., 2009). In the double mutant, synapse morphology shows defects that are identical to that observed in rab3rup alone (data not shown). Thus, all aspects of synapse morphology and physiology are epistatic to rab3rup, but the data highlight different activities of Rab3 during synapse development and homeostasis. The data suggest that Rab3 is necessary for normal morphological synapse development (Graf et al., 2009), whereas it opposes the expression of homeostatic plasticity (this study).

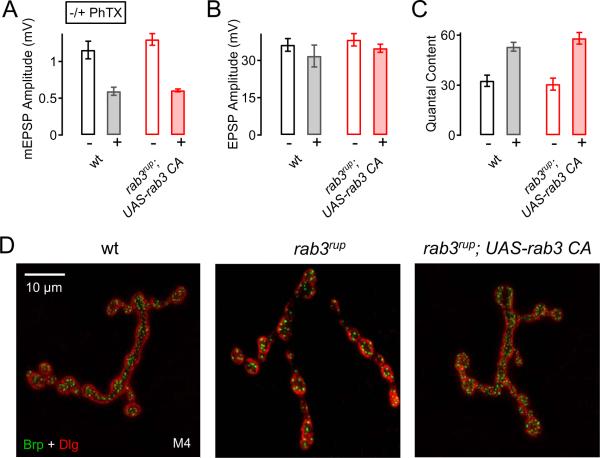

Rab3-GAP converts the GTP-bound form of Rab3 to Rab3-GDP (Fukui et al., 1997). One possibility, therefore, is that Rab3-GTP could accumulate presynaptically in the rab3-GAP mutant, and thereby block homeostatic plasticity. If this is the case, then overexpression of a constitutively active rab3 (GTPase defective: UAS-YFP-rab3.Q80LCA ; Zhang et al., 2007) should block synaptic homeostasis. A similar constitutively active Rab3CA (rab3A.Q81L) was shown to interact with Rab3-GAP in vitro (Clabecq et al., 2000). We overexpressed the GTPase defective rab3 mutation (here referred to as UAS-rab3CA) in either a wild-type (not shown) or in the rab3rup mutant background (Figure 8). In neither case did we observe a defect in synaptic homeostasis. We confirmed that UAS-rab3CA is functional by demonstrating that this transgene is able to rescue the defects in active zone organization observed in the rab3rup mutant (Fig. 8D) (Graf et al., 2009). Based on these data, several conclusions can be made. First, rab3-GAP mutations do not block synaptic homeostasis simply by causing an inappropriate accumulation of Rab3-GTP. Second, the hydrolysis of Rab3-GTP to Rab3-GDP is not required for synaptic homeostasis. This is consistent with the observation that rab3 mutations do not block synaptic homeostasis. We also attempted the converse experiment to overexpress a dominant negative rab3 transgene (UAS-YFP-rab3.T35N; Zhang et al., 2007). However, we find that this transgene is not efficiently trafficked to the NMJ (see also Niwa et al., 2008), which precludes us from testing the function of this mutant transgene at the NMJ.

Figure 8. Expression of Constitutively Active Rab3 Does Not Block Synaptic Homeostasis.

(A – C) Average mEPSP amplitude (A), EPSP amplitude (B), and quantal content (C) of wild-type (− PhTX: n=6; + PhTX: n=7; white/gray bars), and neural expression of a constitutively active (CA) rab3 in the rab3rup mutant background (− PhTX: n=7; + PhTX: n=14; open/filled red bars). In both wild-type and elav-Gal4; rab3rup; UAS-rab3CA, PhTX incubation induced a significant increase in quantal content with respect to control (p<0.001, C). Thus, synaptic homeostasis is normal in elav-Gal4; rab3rup; UAS-rab3CA mutants.

(D) Wild-type (left), rab3rup (middle), and elav-Gal4; rab3rup; UAS-rab3CA mutant (right) muscle 4 NMJs co-labeled with antibodies against discs large (Dlg, red), and Bruchpilot (nc82, green). Note that neural expression of UAS-rab3CA (right) rescues the morphological phenotype seen in rab3rup mutants (middle).

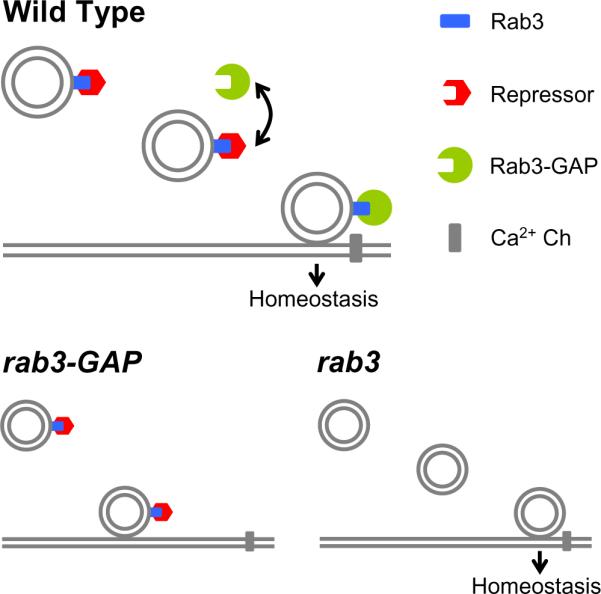

One plausible explanation for our data is that Rab3 does not directly oppose homeostatic plasticity. Rather, Rab3 could scaffold a homoeostatic repressor that prevents homeostatic plasticity and Rab3-GAP competes with this repressor for Rab3 binding. If Rab3-GAP functions at or near the active zone, then the homeostatic repressor would be displaced by Rab3-GAP and vesicles at or near the synapse could participate in homeostatic plasticity. In the rab3-GAP mutant, the repression of synaptic homeostasis would persist and homeostasis would be blocked, as observed. Conversely, in the absence of Rab3, the repressor would never be scaffolded to the vesicle and synaptic homeostasis would proceed regardless of whether or not Rab3-GAP was present, as observed (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Model for the Control of Synaptic Homeostasis Involving Rab3-GAP and Rab3.

Our genetic data support the conclusion that Rab3-GAP is required for synaptic homeostasis. We propose that homeostasis cannot proceed if Rab3-GTP is bound to an unidentified homeostatic repressor (red) at or near the active zone. Binding of Rab3-GAP (green) to Rab3-GTP displaces the homeostatic repressor and allows synaptic homeostasis to proceed (top). In the rab3-GAP mutation (lower left) the homeostatic repressor remains bound to Rab3-GTP and prevents an additional step necessary for homeostatic plasticity. Based on a decreased release probability observed at low extracellular calcium in the rab3-GAP mutant, we speculate that the repressor might prevent close association of docked vesicles with the presynaptic calcium channel. In the rab3 mutant (lower right) the repressor fails to bind to the vesicle and homeostasis proceeds.

DISCUSSION

Here we define a novel function for Rab3-GAP and Rab3 during synaptic homeostasis. We suggest that these molecules participate in a presynaptic signaling system that controls the expression of synaptic homeostasis. We also provide genetic evidence for a novel mechanism that can oppose the homeostatic modulation of presynaptic release probability. Rab3 and Rab3-GAP are well known signaling molecules that are thought to modulate a late stage in synaptic vesicle release (Wang et al., 1997; Schlüter et al., 2004a; Sakane et al., 2006). These molecules have never before been implicated in the mechanisms of homeostatic plasticity.

An Emerging Model for Homeostatic Control of Presynaptic Release

The function of Rab3-GAP and Rab3 have been analyzed extensively, both biochemically and genetically, in systems ranging from yeast to the mammalian central nervous system (Fischer von Mollard et al., 1990; Fukui et al., 1997; Wang et al., 1997; Geppert and Südhof, 1998; Clabecq et al., 2000). Rab3 associates with the synaptic vesicle only in a GTP-bound form (Fischer von Mollard et al., 1990), and there are several (~10 on average) copies of Rab3-GTP on an individual synaptic vesicle (Takamori et al., 2006). It was also shown that Rab3 binds to several presynaptic proteins, most often in its GTP-bound form (Wang et al., 1997; Kanno et al., 2010). Rab3-GAP is required to promote hydrolysis of Rab3-GTP to Rab3-GDP (Fukui et al, 1997). It is unknown precisely when and where Rab3-GAP acts upon Rab3-GTP, but evidence suggests that this interaction may occur at the synapse (Oishi et al., 1998). For example, Rab3-GTP is on the vesicle (Takamori et al., 2006), and delivered to the synapse, where it is found bound to the active zone associated protein RIM (Wang et al., 1997). Biochemical data indicate that clathrin-coated vesicles lack Rab3-GTP (Fischer von Mollard et al., 1991). In combination, these data place Rab3-GAP activity at or near the release site.

The data presented here are consistent with a model in which Rab3-GTP acts, directly or indirectly, to inhibit the progression of synaptic homeostasis at a late stage of vesicle release, and that Rab3-GAP functions to inactivate this action of Rab3-GTP. We show that loss of Rab3-GAP blocks both the rapid induction and sustained expression of synaptic homeostasis. Rab3 mutations alone do not block synaptic homeostasis and synaptic homeostasis proceeds normally in the rab3–rab3-GAP double mutant. Genetically, these data indicate that the presence of Rab3 is required for the block of synaptic homeostasis observed in the rab3-GAP mutant. Thus, Rab3 is likely to be the cognate GTPase for Rab3-GAP. Furthermore, in genetic terms, Rab3 functions to oppose the progression of synaptic homeostasis and, when it is removed, homeostasis proceeds.

We considered the possibility that homeostasis proceeds in the absence of Rab3 because another, redundant Rab takes the place of Rab3. In yeast membrane trafficking, there is evidence for semi-redundant Rab function (Grosshans et al., 2006). However, this seems to be an exception because Rabs are hypothesized to have unique binding affinities for downstream effector proteins that are essential for their ability to define discrete membrane domains within membrane trafficking and secretory systems (Grosshans et al., 2006; Wickner and Schekman, 2008). In C. elegans, Rab3 and Rab27 are both involved in synaptic vesicle release and they can be activated by a common exchange factor (Mahoney et al., 2006). However, based upon available genetic data, these Rabs doe not appear to function redundantly during release (Mahoney et al., 2006). In Drosophila, loss of Rab3 causes a dramatic change in active zone size and organization (Graf et al., 2009). Thus, a redundant Rab would have to selectively and completely replace Rab3 function during synaptic homeostasis without rescuing synapse development, and this seems unlikely. Finally, since Rab3 is required for the complete block of synaptic homeostasis observed in the rab3-GAP mutant, we can conclude that Rab3 itself participates in mechanisms that determine whether or not synaptic homeostasis will proceed.

Next, we considered the possibility that Rab3 accumulates in a GTP-bound form at the synapse in the rab3-GAP mutant background, and this accumulation could block homeostatic plasticity. This model is attractive because it could explain why loss of Rab3 does not block homeostatic plasticity. However, a direct test of this model failed to provide supporting evidence. We overexpressed a constitutively active rab3 transgene in the rab3 mutant background. This experiment should mimic the accumulation of Rab3-GTP in a rab3-GAP mutant background. We find that the constitutively active rab3 transgene (rab3CA) is trafficked to the NMJ and localizes in a manner that is indistinguishable from overexpressed wild-type Rab3 (not shown). Furthermore, rab3CA has activity at the synapse because it rescues the defects in active zone organization that are caused by loss of rab3. In addition, constitutively active Rab3A was shown to biochemically interact with Rab3-GAP (Clabecq et al., 2000). However, the expression of rab3CA did not disrupt synaptic homeostasis. Therefore, aberrant accumulation of Rab3-GTP is not the cause of impaired synaptic homeostasis in the rab3-GAP mutant and we are forced to consider another model.

Another activity of Rab3-GAP that could be relevant to synaptic homeostasis is its ability to physically bind Rab3-GTP (Clabecq et al., 2000). We know that Rab3-GTP can bind several synaptic proteins including RIM and Rabphillin (Kanno et al., 2010). Moreover, we provide evidence that Rab3's GTPase activity is not limiting during synaptic homeostasis (Fig. 8). Therefore, we propose that Rab3-GAP competes for Rab3-GTP binding with another protein. If this other protein inhibits synaptic homeostasis when bound to the synaptic vesicle, then displacement by Rab3-GAP binding would be a required step for synaptic homeostasis to proceed. This model can explain all of our experimental data (Figure 9). First, Rab3-GAP would be necessary for synaptic homeostasis. Second, synaptic homeostasis would proceed normally in the rab3 mutant because the homeostatic inhibitor would no longer localize to the synaptic vesicle. Third, overexpression of rab3CA in the rab3 mutant background would not block synaptic homeostasis because Rab3-GAP would still be able to compete for Rab3-GTP binding, displace the homeostatic inhibitor, and allowing homeostatic plasticity to proceed.

This model is consistent with a conserved function of Rab proteins throughout the membrane trafficking and secretory pathways of organisms ranging from yeast to mammals. Rab proteins, in their GTP bound state, function to nucleate the assembly of `effector' protein complexes that define membrane micro-domains (Grosshans et al., 2006; Wickner and Schekman, 2008). However, throughout the literature, more is known about the assembly of these Rab-dependent complexes than is known about their disassembly (Nottingham and Pfeffer, 2009). Our model assumes that the binding of Rab3-GAP to Rab3 and the Rab3CA mutant protein is sufficient to disrupt effector binding (including the proposed homeostatic inhibitor). It is generally believed that Rab-GAPs interact with their cognate GTPases with lower affinity than the effector proteins. However, although Rab3-GAP has a relatively low affinity for Rab3A, Rab3-GAP effectively competes with an effector (Rabphillin) for binding to Rab3A and this is true even when Rab3A harbors the Q81L mutation (Clabecq et al., 2000). These data support the possibility that Rab3-GAP could compete for effector binding and disrupt a Rab3-GTP dependent scaffold. This is not the only manner in which Rab3-GAP differs from other Rab-GAPs. Rab3-GAP is somewhat unique in that it does not contain additional protein-protein interaction motifs. Thus, unlike IQ-GAP proteins for instance, it seems unlikely that Rab3-GAP has unique functions that are independent of Rab3, consistent with our double mutant analysis of rab3 and rab3-GAP.

Finally, we have considered the possibility is that the rab3-GAP mutation could create a ceiling effect where baseline transmission is normal but release cannot be potentiated under any condition. Several pieces of data argue against this possibility. First, by elevating extracellular calcium, quantal content can be increased in the rab3-GAP mutant, indicating that there is no restriction on the absolute number of quanta that can be released. Second, during a stimulus train (20Hz, 0.4mM extracellular calcium), the rab3-GAP mutant plateaus at a higher EPSP amplitude compared to wild type (Figure 5A–C). Again, there is no evidence for a ceiling effect in rab3-GAP. Finally, we have previously demonstrated that mutations that cause a severe defect in baseline transmission can still undergo homeostatic compensation (Dickman and Davis, 2009). Taken together, these data argue against a simple ceiling effect and support the conclusion that Rab3-GAP is directly involved in the mechanisms of synaptic homeostasis.

A question that we are not yet able to address is which step in our model is modified during the induction of synaptic homeostasis. One interesting possibility is that the interaction of Rab3-GTP with the homeostatic repressor is regulated. For example, if this interaction is stabilized, then homeostatic plasticity would be opposed and, conversely, if the interaction is weakened, then homeostasis would be allowed to proceed. A recent study in C. elegans (Simon et al., 2008) provided evidence that an unknown retrograde signal, from muscle to motoneuron, causes increased expression of YFP-Rab3 at the presynaptic terminal. Although we do not find evidence for a similar phenomenon at the Drosophila NMJ during synaptic homeostasis, these data support the possibility that the Rab3/Rab3-GAP signaling complex could be a downstream, regulated, target of a homeostatic, retrograde signal at the NMJ.

Additional Considerations

Interpreting our data requires consideration of a recent study examining the effects of a rab3 mutation on synapse organization at the Drosophila NMJ (Graf et al., 2009). In this study, it was discovered that a rab3 mutation caused a dramatic accumulation of both the active zone-associated protein Bruchpilot (Brp, T-bars, the Drosophila homolog of CAST/ELKS, (Kittel et al., 2006) and presynaptic calcium channels at a subset of active zones (Graf et al., 2009). Based on these and other data it was suggested that Rab3 promotes the nucleation of new active zones, and without this activity, active zones coalesce (Graf et al., 2009). We are able to clearly dissociate any morphological reorganization of the NMJ from a blockade of synaptic homeostasis. The rab3 mutants have altered NMJ morphology, but normal synaptic homeostasis (Fig. 6), whereas rab3-GAP mutants have normal NMJ morphology and a defect in synaptic homeostasis (Figs. 4, 5).

It is also important to consider why rab3 mutants do not show excessive homeostatic compensation. We predict that Rab3 and Rab3-GAP will not control the magnitude of the homeostatic response, just whether or not it is allowed to proceed. Additional negative feedback signaling mechanisms would be responsible for determining the magnitude of the homeostatic response. This would explain why we do not observe excessive homeostatic compensation in the absence of Rab3. Thus, Rab3 and Rab3-GAP provide an additional layer of control on synaptic homeostasis, ensuring that modulation of release probability only occurs when, and perhaps where, appropriate.

Potential mechanisms underlying the homeostatic modulation of vesicle release probability

Ultimately, we would like to understand how presynaptic vesicle release is modulated during homeostatic plasticity. We know from previously published data that a homeostatic increase in vesicle release is due to a change in presynaptic release probability without a change in active zone number (Frank et al., 2006; Frank et al., 2009; Dickman et al., 2009). Mechanistically, the full functionality of presynaptic calcium channels is necessary for synaptic homeostasis (Frank et al., 2006, 2009). However, it remains unknown whether synaptic homeostasis involves a change in calcium channel number versus calcium channel function. Given these prior data, one possibility is that the homeostatic signaling system, identified here, acts upon presynaptic calcium channels to prevent a change in calcium influx. In this respect, the involvement of RIM and RIM binding protein are intriguing since RIM binds to Rab3-GTP and has been proposed to influence calcium-channel function (Kiyonaka et al., 2007; Hibino et al., 2002).

Rab3-GAP is the first protein to be implicated in the homeostatic modulation of presynaptic release that directly interacts with a resident synaptic vesicle protein. This fact, and our analysis of baseline synaptic transmission in the rab3-GAP mutant raise the possibility that the homeostatic modulation of presynaptic release also includes mechanisms that are independent of increased calcium influx. For example, we observe a defect in presynaptic release probability in the rab3-GAP mutant that occurs only when we record in low extracellular calcium. This defect could reveal a function of Rab3-GAP during vesicle release, or it could reflect the activity of the proposed homeostatic repressor on baseline synaptic transmission. One possibility that could explain the decrease in release probability is that synaptic vesicles reside at a greater physical distance from the calcium channel in the rab3-GAP mutant. When recording in low extracellular calcium, the calcium microdomains at the active zone would not effectively trigger the release of these more distant vesicles. This model would suggest that enhanced coupling of the synaptic vesicle and the calcium channel is part of the homeostatic modulation of presynaptic release. By extension, the action of the homeostatic repressor would be to prevent a tight association of the synaptic vesicle with the calcium channel. It is interesting to speculate that the homeostatic repressor could be Rabphillin. It has been shown that Rabphillin can compete with Rab3-GAP for binding to Rab3-GTP (Clabecq et al., 2000) . Rabphillin has two C2 domains that could confer calcium-dependence to this protein-protein interaction and, by extension, homeostatic plasticity (Geppert and Südhof, 1998). Ultimately, we cannot rule out a molecular change that influences the functionality of the calcium sensor for vesicle fusion. Regardless, our data identify a homeostatic mechanism that functions at a late stage of vesicle release to modulate presynaptic release probability.

Rab3-GAP and Dysbindin Mutations Have Similar Effects On Synaptic Transmission And Synaptic Homeostasis

In combination with a previously published genetic screen (Dickman and Davis, 2009) we have now identified 13 mutations that disrupt the expression of synaptic homeostasis without severely altering baseline synaptic transmission. Among these genes are rab3-GAP and dysbindin (Dickman and Davis, 2009). The mutant phenotypes for rab3-GAP and dysbindin are remarkably similar. In both cases loss of function mutations have little effect on baseline transmission under standard recording conditions (0.4 mM extracellular calcium). However, decreasing extracellular calcium reveals a significant decrease in release probability. In agreement, we also observe an increase in short-term synaptic facilitation in both mutations. Furthermore, neither mutation has an effect on synapse morphology or active zone number. In dysbindin mutants, these effects were shown to be downstream or independent of presynaptic calcium influx. It is tempting to place Dysbindin into the proposed model for homeostatic plasticity (Figure 9). One possibility is that Dysbindin functions to stabilize the close association of synaptic vesicles with the presynaptic calcium channel. The absence of Dysbindin would therefore phenocopy the rab3-GAP mutant but function through a different set of molecular interactions on the synaptic vesicle. The similarity between the phenotypes of dysbindin and rab3-GAP are also interesting because dysbindin has been linked to schizophrenia in human (Ross et al., 2006). The intriguing possibility that Dysbindin interacts with Rab3–Rab3-GAP signaling will be the subject of future studies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Electrophysiology

Sharp-electrode recordings were made from muscle 6 in abdominal segment 2 and 3 of third instar larvae using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments), as previously described (Frank et al., 2006; Frank et al., 2009). The extracellular HL3 saline contained (in mM): 70 NaCl, 5 KCl, 10 MgCl2, 10 NaHCO3, 115 sucrose, 4.2 trehalose, 5 HEPES, and 0.4 (unless specified) CaCl2. For acute pharmacological homeostatic challenge, larvae were incubated in Philanthotoxin-433 (PhTX ; 10, or 20 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min (Frank et al., 2006). See supplemental methods for additional detail.

Immunocytochemistry

Larvae were fixed and analyzed as described previously (Frank et al., 2009). The following primary antibodies were used at the indicated dilutions: anti-Brp (1:100; nc82; Wagh et al., 2006); anti-Dlg (1:5,000), anti-synaptotagmin (1:500), anti-Rab3 (1:1000; Graf et al., 2009), and anti-GFP (1:200). See supplemental methods for additional detail.

Generation of UAS-CFP-Rab3-GAP

The UAS-CFP-Rab3-GAP construct was generated by first amplifying the full-length rab3-GAP open reading frame of isoform A from the BDGP DGC cDNA clone LD40982 and cloning into pENTR™/D-TOPO® (Invitrogen). The rab3-GAP cDNA was then directly cloned into the UASN-terminal Venus (EYFP) vector, pTCW (T. Murphy, Drosophila Genomics Resource Center) using the Gateway® recombination cloning system (Invitrogen). The following primers were used to amplify the rab3-GAP open reading frame: caccATGGCTTGCGAAGTAAAACAC and CTAATTCTGCAGGATACGCA. The construct was confirmed by sequencing. Transgenic flies were generated by standard injection methods by BestGene Inc.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Primer-probes were designed and developed by Applied Biosystems (see supplemental methods for additional detail).

Fly Stocks and Genetics

Drosophila stocks were maintained at 22 – 25 °C on normal food. Unless otherwise noted, all fly lines were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN, USA) or the Exelixis Collection (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA). The rab3rup mutant was kindly provided by Aaron DiAntonio (Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA). Standard second and third chromosome balancers and genetic strategies were used for all crosses and for maintaining mutant lines. For pan-neuronal expression, we used driver elavc155-Gal4 on the X chromosome, and used male larvae (elavc155-Gal4/Y) for all experiments. The w1118 strain was used as a wild-type control.

Data Analysis

Evoked EPSPs were analyzed using custom-written routines in Igor Pro 5.0 (Wavemetrics), and spontaneous mEPSPs were analyzed using Mini Analysis 6.0.0.7 (Synaptosoft).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a fellowship of the Swiss National Science Foundation (PBSKP3-123456/1) to M.M., and a National Institute of Health grant (NS39313) to G.W.D.

We thank Daniel Brasier, Dion Dickman, Meg Younger, and the members of the Davis lab for comments and discussion.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA Supplemental data includes one table, two figures and supplemental text with additional methodology.

REFERENCES

- Aligianis IA, Johnson CA, Gissen P, Chen D, Hampshire D, Hoffmann K, Maina EN, Morgan NV, Tee L, Morton J, Ainsworth JR, Horn D, Rosser E, Cole TR, Stolte-Dijkstra I, Fieggen K, Clayton-Smith J, Megarbane A, Shield JP, Newbury-Ecob R, Dobyns WB, Graham JM, Jr., Kjaer KW, Warburg M, Bond J, Trembath RC, Harris LW, Takai Y, Mundlos S, Tannahill D, Woods CG, Maher ER. Mutations of the catalytic subunit of RAB3GAP cause Warburg Micro syndrome. Nat Genet. 2005;37:221–223. doi: 10.1038/ng1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintapalli VR, Wang J, Dow JA. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39:715–720. doi: 10.1038/ng2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SH, Joberty G, Gelino EA, Macara IG, Holz RW. Comparison of the effects on secretion in chromaffin and PC12 cells of Rab3 family members and mutants. Evidence that inhibitory effects are independent of direct interaction with Rabphilin3. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18113–18120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.18113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clabecq A, Henry JP, Darchen F. Biochemical characterization of Rab3-GTPase-activating protein reveals a mechanism similar to that of Ras-GAP. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31786–31791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GW. Homeostatic control of neural activity: from phenomenology to molecular design. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:307–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman DK, Davis GW. The schizophrenia susceptibility gene dysbindin controls synaptic homeostasis. Science. 2009;326:1127–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.1179685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzl G, Chen D, Schnorrer F, Su KC, Barinova Y, Fellner M, Gasser B, Kinsey K, Oppel S, Scheiblauer S, Couto A, Marra V, Keleman K, Dickson BJ. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;448:151–156. doi: 10.1038/nature05954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer von Mollard G, Sudhof TC, Jahn R. A small GTP-binding protein dissociates from synaptic vesicles during exocytosis. Nature. 1991;349:79–81. doi: 10.1038/349079a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer von Mollard G, Mignery GA, Baumert M, Perin MS, Hanson TJ, Burger PM, Jahn R, Sudhof TC. rab3 is a small GTP-binding protein exclusively localized to synaptic vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:1988–1992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank CA, Pielage J, Davis GW. A presynaptic homeostatic signaling system composed of the Eph receptor, ephexin, Cdc42, and CaV2.1 calcium channels. Neuron. 2009;61:556–569. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank CA, Kennedy MJ, Goold CP, Marek KW, Davis GW. Mechanisms underlying the rapid induction and sustained expression of synaptic homeostasis. Neuron. 2006;52:663–677. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M. Regulation of secretory vesicle traffic by Rab small GTPases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2801–2813. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8351-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui K, Sasaki T, Imazumi K, Matsuura Y, Nakanishi H, Takai Y. Isolation and characterization of a GTPase activating protein specific for the Rab3 subfamily of small G proteins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4655–4658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.8.4655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futai K, Kim MJ, Hashikawa T, Scheiffele P, Sheng M, Hayashi Y. Retrograde modulation of presynaptic release probability through signaling mediated by PSD-95-neuroligin. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:186–195. doi: 10.1038/nn1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geppert M, Südhof TC. RAB3 and synaptotagmin: the yin and yang of synaptic membrane fusion. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1998;21:75–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geppert M, Goda Y, Stevens CF, Sudhof TC. The small GTP-binding protein Rab3A regulates a late step in synaptic vesicle fusion. Nature. 1997;387:810–814. doi: 10.1038/42954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf ER, Daniels RW, Burgess RW, Schwarz TL, DiAntonio A. Rab3 dynamically controls protein composition at active zones. Neuron. 2009;64:663–677. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosshans BL, Ortiz D, Novick P. Rabs and their effectors: achieving specificity in membrane traffic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11821–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601617103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holz RW, Brondyk WH, Senter RA, Kuizon L, Macara IG. Evidence for the involvement of Rab3A in Ca2+-dependent exocytosis from adrenal chromaffin cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10229–10234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houweling AR, Bazhenov M, Timofeev I, Steriade M, Sejnowski TJ. Homeostatic synaptic plasticity can explain post-traumatic epileptogenesis in chronically isolated neocortex. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:834–845. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzi M, Escher G, Meda P, Charollais A, Baldini G, Darchen F, Wollheim CB, Regazzi R. Subcellular distribution and function of Rab3A, B, C, and D isoforms in insulin-secreting cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:202–212. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.2.0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes L, Lledo PM, Roa M, Vincent JD, Henry JP, Darchen F. The GTPase Rab3a negatively controls calcium-dependent exocytosis in neuroendocrine cells. Embo J. 1994;13:2029–2037. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamenetz F, Tomita T, Hsieh H, Seabrook G, Borchelt D, Iwatsubo T, Sisodia S, Malinow R. APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron. 2003;37:925–937. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno E, K I, Kobayashi H, Matsui T, Ohbayashi N, Fukuda M. Comprehensive Screening for Novel Rab-Binding Proteins by GST Pull-Down Assay Using 60 Different Mammalian Rabs. Traffic. 2010;11:491–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyonaka S, Wakamori M, Miki T, Uriu Y, Nonaka M, Bito H, Beedle AM, Mori E, Hara Y, De Waard M, Kanagawa M, Itakura M, Takahashi M, Campbell KP, Mori Y. RIM1 confers sustained activity and neurotransmitter vesicle anchoring to presynaptic Ca2+ channels. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:691–701. doi: 10.1038/nn1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittel RJ, Wichmann C, Rasse TM, Fouquet W, Schmidt M, Schmid A, Wagh DA, Pawlu C, Kellner RR, Willig KI, Hell SW, Buchner E, Heckmann M, Sigrist SJ. Bruchpilot promotes active zone assembly, Ca2+ channel clustering, and vesicle release. Science. 2006;312:1051–1054. doi: 10.1126/science.1126308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd TE, Verstreken P, Ostrin EJ, Phillippi A, Lichtarge O, Bellen HJ. A genome-wide search for synaptic vesicle cycle proteins in Drosophila. Neuron. 2000;26:45–50. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Goaillard JM. Variability, compensation and homeostasis in neuron and network function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:563–574. doi: 10.1038/nrn1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin AR. A further study of the statistical composition on the end-plate potential. J Physiol. 1955;130:114–122. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelstaedt T, Alvarez-Baron E, Schoch S. RIM proteins and their role in synapse function. Biol Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1515/BC.2010.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa S, Tanaka Y, Hirokawa N. KIF1Bbeta- and KIF1A-mediated axonal transport of presynaptic regulator Rab3 occurs in a GTP-dependent manner through DENN/MADD. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1269–79. doi: 10.1038/ncb1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottingham RM, Pfeffer SR. Defining the boundaries: Rab GEFs and GAPs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14185–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907725106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi H, Sasaki T, Nagano F, Ikeda W, Ohya T, Wada M, Ide N, Nakanishi H, Takai Y. Localization of the Rab3 small G protein regulators in nerve terminals and their involvement in Ca2+-dependent exocytosis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34580–34585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen SA, Fetter RD, Noordermeer JN, Goodman CS, DiAntonio A. Genetic analysis of glutamate receptors in Drosophila reveals a retrograde signal regulating presynaptic transmitter release. Neuron. 1997;19:1237–1248. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA, Margolis RL, Reading SA, Pletnikov M, Coyle JT. Neurobiology of schizophrenia. Neuron. 2006;52:139–153. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford LC, DeWan A, Lauer HM, Turrigiano GG. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor mediates the activity-dependent regulation of inhibition in neocortical cultures. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4527–4535. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04527.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakane A, Manabe S, Ishizaki H, Tanaka-Okamoto M, Kiyokage E, Toida K, Yoshida T, Miyoshi J, Kamiya H, Takai Y, Sasaki T. Rab3 GTPase-activating protein regulates synaptic transmission and plasticity through the inactivation of Rab3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10029–10034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600304103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlüter OM, Khvotchev M, Jahn R, Sudhof TC. Localization versus function of Rab3 proteins. Evidence for a common regulatory role in controlling fusion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40919–40929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203704200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlüter OM, Basu J, Sudhof TC, Rosenmund C. Rab3 superprimes synaptic vesicles for release: implications for short-term synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1239–1246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3553-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlüter OM, Schmitz F, Jahn R, Rosenmund C, Sudhof TC. A complete genetic analysis of neuronal Rab3 function. J Neurosci. 2004a;24:6629–6637. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1610-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlüter OM, Schmitz F, Jahn R, Rosenmund C, Sudhof TC. A complete genetic analysis of neuronal Rab3 function. J Neurosci. 2004b;24:6629–6637. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1610-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeburg DP, Feliu-Mojer M, Gaiottino J, Pak DT, Sheng M. Critical role of CDK5 and Polo-like kinase 2 in homeostatic synaptic plasticity during elevated activity. Neuron. 2008;58:571–583. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellwagen D, Malenka RC. Synaptic scaling mediated by glial TNF-alpha. Nature. 2006;440:1054–1109. doi: 10.1038/nature04671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon DJ, Madison JM, Conery AL, Thompson-Peer KL, Soskis M, Ruvkun GB, Kaplan JM, Kim JK. The microRNA miR-1 regulates a MEF-2-dependent retrograde signal at neuromuscular junctions. Cell. 2008;133:903–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Südhof TC. The synaptic vesicle cycle. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:509–547. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MA, Schuman EM. Dendritic protein synthesis, synaptic plasticity, and memory. Cell. 2006;127:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamori S, Holt M, Stenius K, Lemke EA, Gronborg M, Riedel D, Urlaub H, Schenck S, Brugger B, Ringler P, Muller SA, Rammner B, Grater F, Hub JS, De Groot BL, Mieskes G, Moriyama Y, Klingauf J, Grubmuller H, Heuser J, Wieland F, Jahn R. Molecular anatomy of a trafficking organelle. Cell. 2006;127:831–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG. The self-tuning neuron: synaptic scaling of excitatory synapses. Cell. 2008;135:422–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Okamoto M, Schmitz F, Hofmann K, Südhof TC. Rim is a putative Rab3 effector in regulating synaptic-vesicle fusion. Nature. 1997;388:593–598. doi: 10.1038/41580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickner W, Schekman R. Membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:658–64. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]