Abstract

Although the brain has classically been considered “immune-privileged”, current research suggests an extensive communication between the immune and nervous systems in both health and disease. Recent studies demonstrate that immune molecules are present at the right place and time to modulate the development and function of the healthy and diseased central nervous system (CNS). Indeed, immune molecules play integral roles in the CNS throughout neural development, including affecting neurogenesis, neuronal migration, axon guidance, synapse formation, activity-dependent refinement of circuits, and synaptic plasticity. Moreover, the roles of individual immune molecules in the nervous system may change over development. This review focuses on the effects of immune molecules on neuronal connections in the mammalian central nervous system – specifically the roles for MHCI and its receptors, complement, and cytokines on the function, refinement, and plasticity of geniculate, cortical and hippocampal synapses, and their relationship to neurodevelopmental disorders. These functions for immune molecules during neural development suggest that they could also mediate pathological responses to chronic elevations of cytokines in neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and schizophrenia.

Keywords: cytokine, major histocompatibility complex, complement, synapse, refinement, autism, schizophrenia, plasticity

Introduction

Although the brain has classically been considered “immune-privileged”, current research suggests that there is extensive communication between the nervous and the immune systems in both health and disease (Carson et al., 2006; McAllister and van de Water, 2009). The primary goal of this review is to discuss recent evidence that a large number of “immune” proteins are expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) where they play critical modulatory roles in activity-dependent refinement of connections, synaptic transmission, synaptic plasticity, and homeostasis during brain development. These roles for immune molecules during neural development suggest that they could also mediate pathological responses to chronic elevations of cytokines in neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and schizophrenia.

Ever since the 1900s when bacteriologists Ehrlich, Goldman, and Lewandowsky injected dye into animals and noted that the dye stained all of the organs except for the brain, the concept that the brain is compartmentalized from the rest of the body by the “blood–brain barrier” (BBB) has persisted. Until recently, immune cells were thought to infiltrate the CNS only in rare times of disease or trauma (Maehlen et al., 1989; Amantea et al., 2009). Under these circumstances, glial cells in the brain produce cytokines that cross the BBB and signal recruitment of blood-derived monocytes which migrate back through the compromised BBB into the CNS and aid microglia in causing neural inflammation, degeneration, and cell death (Janeway et al., 2005; Bauer et al., 2007). The effects of immune cell infiltration into the CNS has historically been documented as mostly detrimental, especially in the context of autoimmune disorders such as paraneoplastic syndrome, multiple sclerosis (MS), and systemic lupus erythematosus (Bhat and Steinman, 2009).

Despite the dogma that peripheral immune responses could not affect CNS function under normal circumstances, substantial evidence over the past 10 years suggests that immune-CNS cross-talk may be the norm rather than the exception. An intriguing example supporting this new idea comes from studies of immune-deficient (severe combined immunodeficient, SCID) mice. These mice, which lack peripheral T-cells, show impairments in the acquisition of cognitive tasks. Repopulating their T cells via bone marrow transfer significantly restores their adaptive immunity and improves learning. Similarly, acute depletion of adaptive immunity in normal adult mice impairs their learning behavior (Brynskikh et al., 2008). Thus, peripheral immune cells can alter cognition in the absence of CNS immune cell infiltration, suggesting that neural–immune cross-talk may involve more than the simple “breaching” of the BBB.

Moreover, breaching of the BBB may not always be harmful. In traumatic and ischemic injury, MS, infection, and neurodegenerative diseases, activation of an immune response in the CNS may instead contribute to the maintenance, functional integrity, and repair of tissue following an insult (Graber and Dhib-Jalbut, 2009). Furthermore, new therapies for neurodegenerative disorders, including administration of the cytokine interferon-beta (IFN-β) and intravenous immunoglobulin, enhance the protective and regenerative aspects of the immune system in the CNS (Sozzani et al., 2010). A better understanding of both the neuroprotective and destructive roles of the immune response within the CNS is thus essential for continuing to improve treatments. It is increasingly clear that immune molecules should not be blocked entirely from interaction with the brain, but rather that the interplay between the nervous and immune systems retain balance in order to promote health.

Numerous recent studies (many of which will be centrally addressed in this review) have brought attention to important roles for immune molecules in the nervous system. In the absence of disease, many types of immune molecules are normally expressed in the healthy brain and are essential for brain development (Boulanger, 2009; Carpentier and Palmer, 2009; Deverman and Patterson, 2009). Multiple members of the large family of cytokines are normally produced in the healthy brain where they play critical roles in almost every aspect of neural development, including neurogenesis, migration, differentiation, synapse formation, plasticity, and responses to injury (Boulanger, 2009; Carpentier and Palmer, 2009; Deverman and Patterson, 2009). In addition, other immune molecules from both the innate and adaptive immune systems, including major histocompatibility complex (MHC) I molecules, putative MHCI receptors, and components of the complement cascade have recently been found in the healthy brain during development. These immune molecules play critical roles in synapse refinement and plasticity in the cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum, in information processing in the olfactory system, and in potentially mediating the effects of cytokine infiltration during disease (Boulanger, 2009; Shatz, 2009).

Despite these recent advances, most of the details of when, where, and how immune molecules function in the CNS remain unknown. Moreover, it is unclear if these molecules behave similarly in the CNS as they do in the immune system. Do these molecules have completely novel functions in the CNS or can we deduce their mechanism from their role in the immune system? In order to understand this burgeoning concept of “immune” proteins as key players in brain development and function, it is necessary first to have a basic understanding of their already extensively studied roles in the immune response. For this purpose we will begin this review with an overview of the basic concepts of the immune response, focusing on the immunological roles of a limited number of molecules, including MHCI, cytokines, and complement, whose novel roles in the nervous system will be discussed in later sections. This introduction to the immune system will be followed by sections detailing the localization of immune molecules in the CNS, as well as their roles in refinement of connections, synaptic transmission, plasticity, and homeostatic synaptic scaling. The intent of this review is to highlight the importance of this exciting new research area, underscoring the importance of immune molecules in development and function of connections during brain development and disease.

The Immune Response

The immune system, like the nervous system, is highly complex and comprised of specialized components that are fundamental to the existence of an individual. Humans are constantly bombarded with infectious organisms and invading pathogens. Fortunately, we have evolved a highly ordered defense – the immune system. Many details of how the immune response works have been elucidated, but an extensive overview of the immune system is not the purpose of this review. Instead, we seek here only to draw a basic outline of what is known about specific molecules of interest to neuroscientists and the roles of these molecules in immunity.

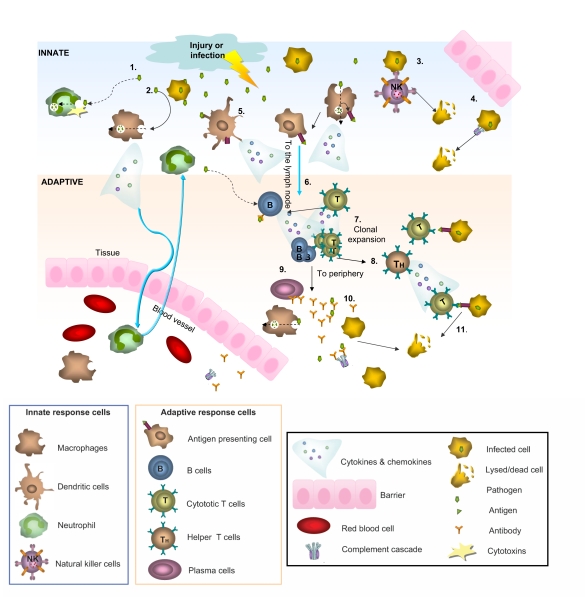

Vertebrate immunity is composed of two complementary branches: an innate and an adaptive system (Figure 1; Janeway et al., 2005). Innate immunity produces a rapid response to evolutionarily conserved pathogens and serves as the first line of defense in the immune system. Cells with important roles in the innate immune system include macrophages, dendritic cells and natural killer (NK) cells. If an antigen gets past the innate immune system, it is attacked and destroyed by components of the adaptive immune response composed of highly specialized lymphoid cells, called B and T-lymphocytes, and antigen-specific antibodies that help eliminate pathogens (Janeway et al., 2005). The adaptive response is defined by its ability to recognize and remember specific pathogens and thus mount stronger and more rapid responses upon subsequent exposures to the same pathogen. The adaptive response is dependent upon the innate response. Helping to bridge this connection are certain proteins common to both pathways including those of the complement system as well as signaling molecules called cytokines that play key roles in the initial innate immune response and the subsequent adaptive response (Rothman et al., 1990; Janeway et al., 2005).

Figure 1.

Innate and adaptive immunity. A simplified schematic of the two branches of the immune response. Following injury or infection, pathogens (bacteria, virus or foreign protein) infiltrate tissue. The innate response provides immediate defense against infection (1–5): 1. Neutrophils engulf the pathogen and destroy it by releasing antimicrobial toxins. 2. Macrophages can directly phagocytose pathogens, leading to production of cytokines and recruitment of more cells from the blood. 3. Infected cells displaying low levels of MHCI on their surface are directly detected by natural killer (NK) cells, which release lytic enzymes causing the infected cell to die via apoptosis. 4. Bacteria can also be recognized by the complement system, resulting in their lysis. 5. Macrophages and dendritic cells can become antigen presenting cells (APCs) by taking up peripheral antigens and migrating to lymph nodes to present antigen on their surface to naïve B- and T- cells. The adaptive response confers the ability to recognize and remember specific pathogens to generate immunity (6–11): 6. APC interaction with B- and T- cells in the lymph nodes leads to B- and T-cell activation and migration to the periphery where they mediate adaptive immunity. 7. Once activated, the T-cell undergoes a process of clonal expansion in which it divides rapidly to produce multiple identical effector cells. Activated T-cells then travel to the periphery in search of infected cells displaying cognate antigen/MHCI complex. 8. Peripheral APCs induce helper T cells to release cytokines and recruit cytotoxic T cells (CTL). 9. Activated antigen-specific B cells receiving signals from helper T-cells differentiate into plasma cells and secrete antibodies. 10. Antibodies bind to target antigens forming immune complexes which can then activate complement or be taken up by macrophages through Fc receptors 11. Formation of cytotoxic T-cell synapses causes lysis of the infected cell.

Cytokines

The ability to convey information is fundamental to an effective immune system, making signaling molecules of paramount importance. Cytokines are one of the largest and most diverse families of signaling molecules in the body. Under healthy conditions, most cytokines circulate at very low concentrations but can increase up to 1,000-fold during trauma or infection (Janeway et al., 2005). Released early in the immune response, they cause a myriad of outcomes including increased MHCI expression and secretion of additional cytokines which augment inflammatory responses (Linda et al., 1998). Cytokines bind to specific membrane receptors, which then signal via second messengers eventually resulting in alterations in gene transcription. There are more than 50 known cytokines, often classified into pro-and anti-inflammatory families. The major pro-inflammatory cytokines responsible for early responses are IL1-α, IL1-β, IL-6, and TNF-α. Other pro-inflammatory mediators include LIF, IFN-γ, OSM, CNTF, TGF-β, GM-CSF, IL11, IL12, IL17, IL18, and a variety of chemokines such as IL-8, CCL2 (MCP-1), CCL5 (RANTES), and CX3CL1 (Fractalkine) that chemoattract inflammatory cells. Anti-inflammatory cytokines limit the potentially detrimental effects of sustained or excess inflammatory reactions. The major anti-inflammatory cytokines include the interleukin (IL)-1 receptor antagonist (IL1-ra), IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-11, IL-13, and TGF-β. With the possible exception of IL-1ra, all of these anti-inflammatory cytokines have at least some pro-inflammatory properties (Janeway et al., 2005). A highly dynamic balance exists between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and this signaling can result in diverse outcomes, such as increased or decreased expression of membrane proteins, proliferation, and/or secretion of effector molecules. In fact, it is often difficult to make generalizations about the roles of individual cytokines due to their frequently redundant and pleiotropic effects. To add to this complexity, combinations of cytokines can act either synergistically or antagonistically depending on the state of the target cells and the combinations, doses, and temporal sequence of cytokine secretion (Janeway et al., 2005).

In this review, we will focus mostly on three cytokines that have been extensively studied in the nervous system – tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL)-1, and IL-6. Deregulated overproduction of these three pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as the resultant disequilibrium between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory functions, have been shown to underlie the pathophysiology of many diseases such as autoimmune diseases, therefore these cytokines are attractive candidates for central signaling roles (Hawkes et al., 1999; Cunningham et al., 1996). All three of these cytokines are involved in the acute immune response and initial inflammation. They are produced by many cell types including macrophages, monocytes, fibroblasts, dendritic cells, T cells, B cells, monocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells. Among one of the first cytokines discovered, IL-1 (α and β) is most potent at activating fever. IL-6 was originally identified as a T-cell-derived factor that induces activated B cells to differentiate into antibody-producing cells (Figure 1). TNFα is well known for its ability to induce inflammation, inhibit tumorigenesis and viral replication, and to induce apoptotic cell death. Although these three cytokines are associated with the acute response in innate immunity, they also act to regulate molecules associated with adaptive immunity such as MHCI.

MHCI

Because activation of adaptive immunity can be highly destructive, it is essential that it is activated only in response to foreign proteins and not to self proteins (Janeway et al., 2005). The adaptive immune response is triggered by recognition of non-self antigens, which are displayed on antigen presenting cells (APCs) through MHC. MHCI proteins are cell-surface ligands that bind to T cell receptors (TCR) and other immunoreceptors and act to regulate the activation state of immune cells. One of the defining features of MHC molecules and their receptors is their complexity. They are both polygenic-containing multiple genes and polymorphic-containing multiple variants of each gene. The MHC genes are the most polymorphic genes known (Janeway et al., 2005). The specific genes and variants that an individual expresses comprise its MHCI haplotype. The human MHC is encoded on chromosome 6 and contains 140 genes. In humans, there are three classical MHCI genes, the HLA class I antigens A, B, and C; the other MHCI genes are classified as non-classical. The rat MHC is encoded on chromosome 20 and contains a classical class I MHC-encoding region, RT1A, and other adjacent encoding regions including a non-classical class I MHC-encoding region, RT1-C/E/M. The RT1A region of the RT1 complex encodes between 1 and 3 classical class I molecules, depending on the rat strain. The mouse MHCI region is located on chromosome 17 and encodes the three H-2 genes – H2-K, H2-D, and H2-L. Each inbred mouse strain expresses a unique combination of MHCI molecules. Each of the classical MHCI molecules includes a β2-microglobulin (β2m) light chain, encoded by a single gene. Finally, the non-classical MHCI region in both rats and mice encodes numerous molecules, many of which have not yet been characterized even in the immune system (Abbas et al., 2000).

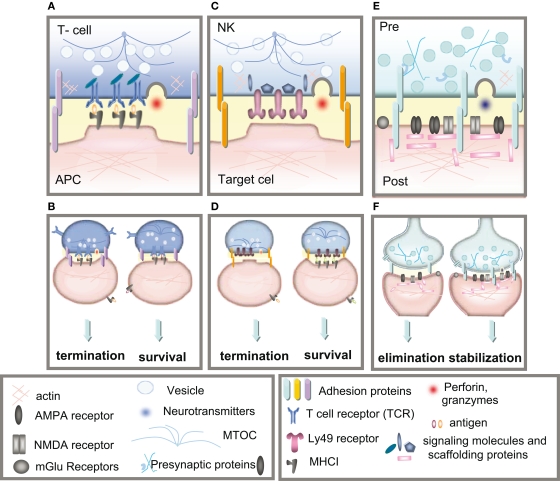

Classical MHCI molecules are trimeric proteins comprised of a transmembrane heavy chain, the β2m light chain, and a peptide bound in the groove of the heavy chain. Complete trimers are transported to the cell surface of almost all cells in the body (Machold and Ploegh, 1996). Peptides presented by MHCI heavy chain on the cell surface are derived from proteolysis of intracellular proteins and are monitored by T-cells. The T-cell repertoire is established during development through the creation of millions of T-cells, each harboring a unique TCR. When a TCR binds to an MHC molecule presenting a non-self peptide, an immunological synapse is formed (Figure 2A). The immune synapse consists of the TCR (αβ subunits) bound by a cluster of differentiation protein 3 complex (CD3) and ζ-chain (CD3ζ) proteins. In mammals, the CD3 complex contains a CD3γ chain, a CD3δ chain, and two CD3ε chains. The CD3γ, CD3δ, and CD3ε chains are highly related cell-surface proteins of the immunoglobulin superfamily containing a single extracellular immunoglobulin domain. Formation of the complete T-cell immune synapse initiates an immune response, leading to eventual lysis of cells displaying foreign peptide (Cantrell, 1996; Abbas et al., 2000).

Figure 2.

Immune and neuronal synapses. Highly simplified schematics of these synapses illustrate the common core components of these asymmetric junctions. (A) A cytotoxic T-cell immune synapse is formed between an antigen-specific T-cell and a cell infected with an intracellular pathogen. The close junction is formed from a ring of adhesion proteins (purple cylinders) surrounding an inner signaling molecular domain of antigen receptors (MHCI; gray y) bound to T-cell receptors (TCR; blue Y). Cytokine receptors also cluster in the synapse (not shown in the diagram) where they are exposed to cytokines secreted into the synapse. (B, left) Activation of TCR signaling by MHCI molecules presenting non-self antigens (orange ovals) causes a signaling cascade resulting in polarization of the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton (blue lines) in the T-cell, recruitment of lytic granules (circles) and cell-surface receptors and co-stimulatory molecules (including trans-synaptic adhesion molecules [purple ovals]) to the synapse, secretion of lytic granules (red) and apoptosis of the infected cell. (B, right) Conversely, TCR interaction with an MHC1 molecule containing a non-TCR specific peptide (orange ovals) does not affect microtubule reorganization and does not recruit lytic granules, resulting in termination of the contact and survival the APC. (C)The lytic natural killer (NK) cell immune synapse is also specialized for mediating cytotoxicity. An encounter between an NK cell and a target cell results in adhesion (orange ovals). The balance between activating and inhibitory receptor (pink) signaling at the cell–cell contact determines the outcome of the interaction. (D, left) A lack of MHCI on the target cell, caused by viral infection or tumorigenesis, triggers a signaling cascade in the NK cell resulting in reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, clustering of cell-surface receptors (pink) and signaling molecules (blue) in the NK cell, recruitment and secretion of lytic granules, ultimately resulting in lysis of the target cell. (D, right) Conversely, the presence of MHCI (gray y) on the target cell results in binding of MHCI to NK inhibitory receptors, including PirB and Ly49s and initiates dominant inhibitory signaling, preventing the formation of the NK cell activation synapse and resulting in survival of the target cell. (E) Glutamatergic synapses in the mammalian CNS are comprised of several major protein classes. In the presynaptic axon terminal (blue), synaptic vesicles (circles) containing the neurotransmitter glutamate (blue) cycle at the active zone, which is composed of many kinds of proteins including presynaptic scaffolding proteins (blue Xs and hooks). The presynaptic terminal is separated from the postsynaptic dendrite (pink) by the synaptic cleft (yellow). A number of families of trans-synaptic adhesion molecules (blue ovals) span this cleft, providing a molecular connection capable of rapid signaling between the pre- and postsynaptic membranes. Glutamate receptors (gray), including AMPA and NMDA receptors, are found in the postsynaptic membrane, where they are associated with a large number of scaffolding and signaling proteins (pink rectangles) that together comprise the postsynaptic density. (F) If the synapse is weakened by long-term depression (LTD) then it can be eliminated (left), but if it is strengthened by long-term potentiation (LTP) then it will be stabilized and grow (right).

In addition to binding T-cell receptors, MHCI molecules also bind to inhibitory receptors (IRs) on natural killer (NK) cells, which are part of the innate immune system (Krzewski and Strominger, 2008; Long, 2008). There are three major families of MHCI receptors found on NK cells including killer cell-immunoglobulin receptor (KIR), CD94/NKG2 and leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor (LILR) in humans and LY49, murine NKG2 and the paired immunoglobulin-like receptor (PIR) receptors in rodents. Each family has multiple members that can either inhibit or activate apoptosis of a target cell. The balance between activating and inhibitory receptor (IR) signaling on the NK–target cell interface determines the outcome of the interaction. A lack of MHCI on the target cell, caused by viral infection or tumorigenesis, favors formation of the activating immune synapse (Figure 2B). Conversely, the presence of MHCI on the target cell results in binding of MHCI to NK-IRs, which initiate a classical NK-IR signaling pathway that prevents the formation of immune synapses required for NK activation and apoptosis of the target cell (Krzewski and Strominger, 2008; Long, 2008).

The complement system

The complement system is a critical component of both innate and adaptive immunity. Although the complement system is most commonly classified under innate immunity, this process is also induced by antibodies, constituents of adaptive immunity, to more rapidly mark pathogens for destruction (Janeway et al., 2005). Activation of complement initiates a complex biochemical activation cascade of over 25 proteins and protein fragments that opsonize pathogens and induce inflammatory responses. It consists of three distinct pathways – the classical, the mannose binding lectin (MBL), and the alternative pathways, that all depend on different molecules for their initiation but converge on the C3-convertase and result in the same cascade of complement activation. The classical pathway is triggered by activation of the C1 complex (C1q, two C1r, and two C1s molecules thus forming C1qr2s2), which occurs when C1q binds to antibody: antigen complexes or when C1q binds directly to the surface of a pathogen. Binding leads to conformational changes in the C1q molecule, in turn leading to the activation of complement proteases that cleave specific proteins to release cytokines and initiate a cascade of further cleavages, resulting in amplification of the response and activation of the cell-killing membrane attack complex. C3-convertase cleaves and activates component C3, creating C3a and C3b and causes a cascade of further cleavage and activation events. Activation of the complement cascade leads to lysis of the target cell.

Immune Molecules are Present in Healthy Neurons and GLIA

It has been appreciated for years that stress, trauma, infection, and seizures can increase neural–immune cross-talk. These insults all have dramatic effects on increasing cytokine expression in both neurons and glia. In turn, at least some cytokines like IFNγ upregulate MHCI expression in central and peripheral neurons in vitro and in vivo (Fujimaki et al., 1996; Zhou, 2009). However, in the past 10 years, discoveries that immune molecules are expressed in the healthy CNS and are essential for brain development have disproven the once-dominant paradigm of CNS immune privilege (Boulanger, 2009; Carpentier and Palmer, 2009; Deverman and Patterson, 2009). The presence of immune molecules in the CNS was overlooked until recently in large part because the expression patterns of many immune proteins in the CNS change over development and the levels of expression under normal healthy conditions tend to be quite low. This makes detecting mRNA and protein challenging and may have added to the misconception that immune molecules are only expressed in the CNS during periods of infection or trauma.

The nervous and immune systems share many proteins (Tian et al., 1999; Khan et al., 2001; Pacheco et al., 2004; Suzuki et al., 2008), including cytokines, MHCI, and proteins of the complement system to name a few. Both systems also employ tightly controlled communication through specialized, sophisticated cell–cell junctions called synapses (Figure 2; Yamada and Nelson, 2007). Confining the molecules released – neurotransmitters in the CNS and lytic enzymes and cytokines in the immune system – to synapses ensures that they will act specifically and locally on target cells, with minimal effects on neighboring cells. Immunological synapses can form between a T-cell and an APC (Figure 2A) and between an NK cell and a target cell (Figure 2B; Yamada and Nelson, 2007). Just as the immune synapse transfers information and is necessary for immune activation, the CNS synapse (Figure 2C) transfers information and is necessary for cognition. Although the synaptic localization of most immune molecules in neurons remains understudied, especially in vivo, several immune molecules and/or receptors, including some cytokines and their receptors (Vikman et al., 1998; Kubota et al., 2009), MHCI molecules (Huh et al., 2000) and components of the complement system (Stevens et al., 2007) have functions associated with synaptic changes in the healthy CNS (see Roles of immune molecules in the healthy CNS). It is tempting to speculate that immune molecules will play a similar role at the CNS synapse as at the immune synapse, but much more needs to be known about location and function of immune molecules in the CNS to draw direct parallels.

Cytokines in the CNS

For years it has been well-established that many cytokines, chemokines, and their receptors are constitutively expressed in the brain throughout development and in the adult. Although many cytokines and their receptors remain unstudied, the major cytokines IL1-α, IL1-β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-11, IL-13, IL-18, TNF-α, IL1-ra, TGF-β, and CCL2 are all expressed in the healthy CNS (Bauer et al., 2007). Many of these cytokines and their receptors have differential expression patterns across the CNS that vary over development (Takao et al., 1992; Gadient and Otten, 1994; Pousset, 1994). For example, mRNAs for IL-6 and its receptor (IL-6R) are developmentally regulated in a tissue-specific manner in the rat brain (Gadient and Otten, 1994). The adult hippocampus has the highest detectable levels of both transcripts, while IL-6 mRNA levels are highest during early brain development in most other brain regions. Levels of IL-6 mRNA can be dramatically upregulated with age; they increase up to 8-fold in the striatum during development (Gadient and Otten, 1994). In the majority of studies, the expression profiles of cytokines and their receptors have been examined using in situ hybridization and RT-PCR in rodent brains (Rothwell and Hopkins, 1995; Rothwell et al., 1996; Meng et al., 1999; Ishii and Mombaerts, 2008). Confirming cytokine expression at the protein level in the CNS has been challenging and remains mostly incomplete given the purported lack of specificity of many commercially available antibodies necessary for western blot and immunocytochemistry experiments. Despite this caveat, it is clear that cytokines are produced by, and can act on, almost all CNS cells including neurons, astrocytes, and resident microglia (Hopkins and Rothwell, 1995; Mehler and Kessler, 1995; Kaufmann et al., 2001; Kielian et al., 2002; Geppert, 2003; Harkness et al., 2003; Koyama et al., 2007). Interestingly, IFN-γ and is found at neuronal synapses (Vikman et al., 1998) suggesting that it may act at the level of the synapse to influence brain function. In order to generate well-informed hypotheses for the function of cytokines in the healthy CNS, the field of neuroimmunology must generate specific antibodies to cytokines and their receptors and use them to determine their distribution during development and plasticity. In addition, an understanding of the signaling mechanisms underlying cytokine function in neurons is needed to provide essential insights into the roles of cytokines that regulate normal and abnormal brain functions.

MHCI in the CNS

Perhaps the biggest surprise in this field has been the discovery that many of the proteins central to the innate and adaptive immune responses are found on neurons and glia in the healthy brain (Ishii and Mombaerts, 2008). One of the first and most influential papers to demonstrate this constitutive expression was published 12 years ago from the Shatz laboratory (Corriveau et al., 1998). Using an unbiased PCR-based differential display screen for activity-regulated genes in the developing feline visual system, the Shatz lab discovered a substantial decrease in neuronal MHCI mRNA following activity blockade. Examination of the expression of several MHCI forms using in situ hybridization showed that MHCI molecules are expressed in unique, spatially and temporally restricted patterns in healthy, unmanipulated brains (Corriveau et al., 1998). Subsequently, MHCI mRNA and/or protein has been detected in several neuronal populations, including dorsal root ganglia neurons and brainstem motoneurons (Lidman et al., 1999; Loconto et al., 2003; Edstrom et al., 2004; Harnesk et al., 2009) as well as developing and adult hippocampal pyramidal (Neumann et al., 1997; Corriveau et al., 1998; Goddard et al., 2007; Ribic et al., 2010) and cerebellar (Corriveau et al., 1998; McConnell et al., 2009) neurons. MHCI protein is also enriched in neuronal synaptic membranes (Huh et al., 2000).

The search for the receptor through which MHCI functions in neurons has been much more challenging than initially expected. In the immune system, peptide-presenting MHCI molecules are usually thought to bind to T-cell receptors (TCRs) to mediate the adaptive immune response. However, there is no evidence for TCRα or TCR protein in neurons (Syken and Shatz, 2003; Boulanger and Shatz, 2004). Yet, many other immunoreceptors and associated effector molecules for MHCI such as PIRB (Syken et al., 2006; Atwal et al., 2008), Ly49 receptors (Zohar et al., 2008), KIR (Bryceson et al., 2005), and CD3ζ (Corriveau et al., 1998; Xu et al., 2010) are all found in the CNS where they display distinct gene expression and/or protein patterns and most are expressed in highly plastic regions. PirB is found throughout the CNS, and is present in the visual system during the period of activity-dependent plasticity (Syken et al., 2006). PirB protein is localized to axonal growth cones and dendrites, where it is often very close to, but rarely overlaps with, the presynaptic proteins synaptophysin or synapsin, suggesting that PirB is localized near synapses (Syken et al., 2006). Ly49 mRNA is also amply expressed in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus, and cerebellum in adult mouse brain (Zohar et al., 2008). Ly49 protein in neurites colocalizes with synapsin and alternates with the postsynaptic marker Shank (Zohar et al., 2008). KIR genes are selectively expressed in olfactory bulbs, rostral migratory stream, and dentate gyrus of hippocampus, subregions of the mouse brain where synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis occur (Bryceson et al., 2005). Finally, CD3ζ is also found throughout the developing and adult CNS and in the retina, where it is preferentially expressed by retinal ganglion cells (RGC) and colocalizes with PSD95 and CtBP2, a presynaptic ribbon protein in the IPL during the period of synaptic formation (Xu et al., 2010).

Mechanistically, MHCI may act through one or all of these receptors in an analogous fashion to its signaling in the immune system. However, the documented expression patterns of MHCI immunoreceptors do not adequately account for the documented functions (see below) and diversity of localization of specific MHCI forms. Thus, MHCI may bind multiple receptors or as yet unidentified neuronal receptors. In the future, the subcellular distribution of MHCI in neurons, at synapses, and in all glial cell types must be determined in order to propose testable models for MHCI function. Proteomic and biochemical identification of all possible MHCI receptors and downstream signaling molecules, as well as the development of more specific antibodies to localize all of the MHCI and MHCI receptor subtypes, are essential to clarify these fundamental issues.

Complement

In addition to cytokines and MHCI, essential components of the complement cascade, including C1q and C3, are also expressed in the CNS. They are expressed in a punctate pattern in the developing but not the adult brain, peaking during periods of synapse formation and activity-dependent refinement (Perry and O'Connor, 2008). In the retina, C1q protein is detected in immunostained cryosections in the synaptic inner plexiform layer (IPL) of postnatal mouse retinas and in developing RGCs. It colocalizes with synaptic proteins, postsynaptic density-95 (PSD-95) and synaptophysin puncta – mostly with one or the other of these proteins, but not often with both, at non-synaptic sites in the early postnatal retina. RGCs upregulate complement proteins in response to secreted molecules from astrocytes (Stevens et al., 2007). Moreover, C1q is often colocalized with MHCI at synapses between hippocampal neurons (Datwani et al., 2009), suggesting that these immune molecules may interact to alter synaptic function.

Roles of Immune Molecules in the Healthy CNS

Immune molecules are present at the right place and time to modulate the development and function of the healthy and diseased CNS. Indeed, recent research suggests that immune molecules play integral roles in the CNS throughout neural development, including affecting neurogenesis, neuronal migration, axon guidance, synapse formation, activity-dependent refinement of circuits, and synaptic plasticity (Zhao and Schwartz, 1998; Deverman and Patterson, 2009). Complicating this already complex field is the observation that the functions of individual immune molecules in the nervous system may change over development. For example, during sequential stages of development, TGFβ regulates neural induction, cell lineage commitment, neuronal differentiation, axon growth and guidance (Pousset, 1994; Charron and Tessier-Lavigne, 2007), and neuromuscular synapse formation and function (Sanyal et al., 2004; Feng and Ko, 2008; Heupel et al., 2008). Because we cannot adequately cover all of the roles for immune molecules in CNS development in a single review, we focus here on the effects of immune molecules on neuronal connections – specifically on the function, refinement, and plasticity of primarily geniculate, cortical and hippocampal synapses, and their relationship to neurodevelopmental disorders.

Refinement of connectivity

In order to create cohesive synaptic networks, appropriate connections must be formed and superfluous ones selectively eliminated. Most studies of the effects of immune molecules on refinement of connections in the CNS during development have used one of the most classical models for activity-dependent refinement of connections – visual system plasticity (Shatz, 2009). Visual information is carried from the retina through RGC axons into the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) of the thalamus and from there up to primary visual cortex. In binocular adult animals, axons carrying information from each eye are segregated into eye-specific layers in the LGN and into eye-specific regions, called ocular dominance (OD) columns, in layer 4 of visual cortex. Initially, inputs from each eye are thought to overlap in both the LGN and cortex and then become segregated later only after a period of activity-dependent synaptic refinement (Katz and Shatz, 1996). Studies from many laboratories have demonstrated that segregation of both retinogeniculate and geniculocortical axons is activity-dependent and involves competition between axons from each eye (Katz and Shatz, 1996; Hua and Smith, 2004). During critical periods, neural activity sculpts connections by strengthening and stabilizing subsets of synapses and weakening and eliminating others. If vision is restricted to only one eye during this critical period, the areas innervated by the deprived eye shrink while those innervated by the non-deprived eye expand (Katz and Shatz, 1996).

How neural activity ultimately leads to refinement is not well understood, but immune molecules appear to play an important role in this process. MHCI genes were first identified in the LGN in a screen for genes involved in the activity-dependent refinement of retinogeniculate axons (Corriveau et al., 1998). More recently, components of both the innate and adaptive immune systems – MHCI, its receptors, and complement – have been implicated in this process (Boulanger et al., 2001; Oliveira et al., 2004). The prevailing hypothesis in this field is that immune molecules in neurons engage MHCI receptors, generating common intracellular signals in both neurons and immune cells that ultimately alter synaptic strength, neuronal morphology, and circuit properties downstream of synaptic activity (Boulanger et al., 2001; Syken et al., 2006; Fourgeaud and Boulanger, 2007).

Consistent with this idea, transgenic mice have been used to discover dramatic effects of immune molecules on refinement of connectivity during brain development. In order to determine the role for MHCI during activity-dependent plasticity, retinogeniculate projections were examined in β2m/TAP1 double-knockout (DKO) mice, in which MHCI on the surface of their cells is dramatically decreased due to the lack of β2m, the MHCI light chain required for transport of MHCI to the membrane, and the transporter associated with antigen processing 1 (TAP1), which packages proteasomal peptides required for most MHCI receptor-mediated signaling (Abbas et al., 2000). These β2m/TAP1 DKO mice have a significantly larger projection from the ipsilateral eye in the LGN (Corriveau et al., 1998; Huh et al., 2000), interpreted as indicating a lack of pruning of the inappropriate retinogeniculate axons. A similar impairment of refinement of retinogeniculate layers was found in an MHCI KO mouse lacking both H2-Kb and H2-Db genes (Datwani et al., 2009) and in mice lacking CD3ς (Huh et al., 2000). Interestingly, OD plasticity was enhanced in the KbDb KO mouse (Datwani et al., 2009), further supporting the conclusion that MHCI might be critical for mediating the effects of activity in modifying neural connections (Huh et al., 2000). Because the PirB KO mouse phenocopies the enhanced OD plasticity in the KbDb KO, PirB is likely the MHCI receptor in cortex (Syken et al., 2006; Datwani et al., 2009). However, retinogeniculate remodeling was unaltered in the PirB KO (Syken et al., 2006), implying that there are likely additional means by which MHCI molecules exert their effects in the developing LGN.

Although the hypothesis that MHCI acts at CNS synapses to mediate activity-dependent synaptic weakening and elimination of inappropriate connections (Shatz, 2009) is consistent with effects of MHCI on synaptic plasticity (see below), a recent report has suggested an alternate hypothesis – that MHCI contributes to retinogeniculate refinement indirectly by altering the structure and function of RGCs (Xu et al., 2010). CD3ς is expressed in RGCs and CD3ς-deficient mice exhibit reduced RGC dendritic motility, an increase in RGC dendritic density, and a selective defect of glutamate-receptor-mediated synaptic activity in the retina (Xu et al., 2010). In contrast with previously reported hypotheses that MHCI directly regulates refinement, this change in glutamate-receptor-mediated synaptic activity suggests that MHCI may instead be altering activity patterns and thus indirectly affecting refinement. Furthermore, it is clear that MHCI is not required for all forms of activity-dependent refinement since loss of MHCI molecules does not alter refinement of climbing fiber-Purkinje cell projections (Letellier et al., 2008; McConnell et al., 2009). Thus, the roles for MHCI in refinement of connections during CNS development may be complex and system-specific. There is much to be done to fully understand the effects of these immune molecules in brain development. Elucidating the precise role for MHCI molecules and its receptors in synaptic refinement is a critical issue for this field.

Classical complement proteins also play a role in retinogeniculate refinement. Like those seen in the β2m/TAP DKO mice, defects in eye-specific segregation occur in mice in which components of the complement cascade are knocked out (C1q and C3 KOs), thus complement may mediate activity-dependent elimination of exuberant connections (Stevens et al., 2007). Using a gene profiling approach on RGCs, immature astrocytes were found to induce the expression of the C1qA, C1qB, C1q – components of the complement system – on neurons (Stevens et al., 2007). C1q localizes to synapses both in culture and in the postnatal CNS and this expression significantly declines by P30 (Stevens et al., 2007). Although the mechanism by which complement-tagged synapses might be eliminated has not been discovered, it is possible that microglia expressing the C3 receptor may be involved (Gasque et al., 1998). In motor neurons, microglia have been proposed to eliminate synapses via phagocytosis-synaptic stripping (Schiefer et al., 1999) and a similar process may occur in the CNS. Whether complement and MHCI molecules interact to regulate activity-dependent refinement of connections has not yet been addressed. A major challenge for this field in the future will be to determine whether and how immune molecules interact mechanistically to alter connectivity in the developing CNS.

The role of cytokines and their receptors in refinement of connections in the developing CNS is much less clear. However, two recent studies suggest that these diffusible factors are key players in this process. First, following monocular lid suture, mice deficient in TNFα show the normal initial decrease in cortical responses from the deprived eye, but do not show the subsequent increase in response to the open eye (Kaneko et al., 2008). Second, chronic exposure of Xenopus to TNFα decreases the number of immature synapses containing only NMDARs and no AMPARs on tectal neurons. Thus, chronic exposure to this pro-inflammatory cytokine may cause premature maturation and stabilization of these synapses (Lee et al., 2010). Interestingly, TNFα increases the growth of dendrites of tectal neurons and enhances connectivity, similar to what is seen in immature, less well-refined tectal circuits (Lee et al., 2010). Given the widespread effects of many cytokines on synaptic plasticity (see below), especially long-term potentiation and depression which are believed to underlie activity-dependent refinement of connections (Hensch et al., 1998), it is likely that many members of the large family of cytokines will also play important roles in refinement of connections in the developing brain.

Although exuberant connectivity in the visual system in β2m/TAP1 DKO, PirB KO, H2-Kb/H2-Db DKO, C1q KO, and C3 KO mice has been interpreted to indicate a lack of synapse elimination, it is equally possible that this phenotype is the result of increased axonal growth, synapse formation, and/or synapse stabilization. Clarifying this issue is absolutely critical to understand how these molecules alter activity-dependent refinement of connections. Yet, there is currently no assay available that can distinguish whether a molecule changes synapse density through altering the formation or elimination of synapses. Development of new assays allowing long-term imaging of synaptic connections is critical to address this fundamental issue in the future.

Synaptic transmission

In addition to mediating activity-dependent refinement of connections during CNS development, many immune molecules also regulate synaptic transmission between hippocampal and cortical neurons. For example, MHCI molecules affect basal transmission at glutamatergic synapses in cultured hippocampal neurons and cortical slices. β2m/TAP1 DKO mice exhibit slightly larger presynaptic terminals in cultured hippocampal neurons and a small (10%) but significant increase in the number of synaptic vesicles at synapses in adult hippocampal slices as determined by electron microscopy (Goddard et al., 2007). Consistent with these changes in synaptic composition, mEPSCs are altered in cultured hippocampal neurons from β2m/TAP1 DKO mice compared to controls. mEPSC frequency increases by 40% in hippocampal DKO cultures and by over 100% in acute cortical slices from DKO mice, while mEPSC amplitude is unchanged. Because the authors did not detect a change in synapse density in their DKO hippocampal cultures, they interpreted the increase in mEPSC frequency as due to a change in synaptic vesicle release probability (Goddard et al., 2007). The cause of the 100% increase in mEPSC frequency in cortical slices was not assessed. Finally, H2-KbDb DKO mice show enhanced presynaptic glutamate release at climbing fiber (CF)-Purkinje cell (PC) synapses in the cerebellum (McConnell et al., 2009). Measures of postsynaptic function, including mEPSC amplitude, were not altered by manipulation of MHCI levels in either system, suggesting that MHCI molecules selectively regulate synaptic vesicle release.

Several cytokines also alter synaptic transmission, but the nature of their effects is highly dependent on the specific cytokine studied and its dose. For example, recombinant IL-1β decreases the frequencies but not the amplitudes of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSC) and mEPSCs in cultured hippocampal neurons. IL-1β also increases the NMDA receptor-mediated current and the amplitude of the voltage-dependent Ca2+current (ICa), in a dose-dependent manner (Yang et al., 2005). Conversely, recombinant TGFβ2 increases both the frequency and amplitude of mEPSCs in hippocampal neurons (Fukushima et al., 2007). Similarly, recombinant TNF-α increases mEPSC frequency and amplitude and enhances EPSPs (Beattie et al., 2002; Stellwagen et al., 2005; Stellwagen and Malenka, 2006). TNFα works in large part by promoting the surface accumulation of AMPA-type glutamate receptors (AMPARs) in hippocampal neurons in vitro (Beattie et al., 2002). TNFα appears to work primarily postsynaptically since there is no effect on paired-pulse facilitation, a measure of presynaptic function (Beattie et al., 2002). Similarly, blocking endogenous TNFα using a soluble TNF receptor, sTNFR1, decreases mEPSC frequency and amplitude, surface AMPAR levels, and the AMPA/NMDA ratio in hippocampal slices (Beattie et al., 2002; Stellwagen et al., 2005). While it is unclear if all cytokines are released from glia, the endogenous TNFα that alters synaptic transmission does come primarily from glial sources (Beattie et al., 2002; Stellwagen et al., 2005).

In contrast to their effects on the function of excitatory synapses, the effects of immune molecules on inhibitory synapses remain mostly unknown. MHCI may control GABAergic inputs since it is a target of the transcription factor Npas4, which enhances GABAergic synapse density (Lin et al., 2008). Likewise, several cytokines, including IL-1β (Zeise et al., 1992) and TNF-α (Stellwagen et al., 2005) regulate inhibitory synaptic transmission. Recombinant IL-1β inhibits GABAergic currents and GABAergic synaptic transmission in hippocampal neurons (Zeise et al., 1992; Wang et al., 2000). Similarly, recombinant TNFα decreases the strength of GABAergic synapses (Stellwagen et al., 2005), suggesting that TNFα could mediate the balance between excitation and inhibition on hippocampal neurons. Because so little is known about the effects of immune molecules on inhibition, future studies are necessary to better understand the potential effects of immune molecules on the ratio of excitatory-to-inhibitory synapses.

Synaptic plasticity

The cellular mechanisms underlying activity-dependent refinement of connections during CNS development are thought to involve a regulated combination of Hebbian synaptic plasticity –long-term plasticity (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) – and homeostatic plasticity. Many immune molecules studied to date modulate one or both of these forms of long-term plasticity (Bauer et al., 2007; Boulanger, 2009).

LTP/LTD

Although the mechanisms through which MHCI molecules regulate activity-dependent refinement of circuits are yet unclear, many manipulations of MHCI result in changes to long-term plasticity. Hippocampal LTP is enhanced (Huh et al., 2000; Barco et al., 2005) and LTD is abolished at standard stimulation frequencies in β2m/TAP1 DKO mice (Huh et al., 2000). Like MHCI, CD3ζ is also required for hippocampal LTD and limits LTP (Huh et al., 2000). Finally, another signaling component of MHCI receptors in immune cells – DAP12 – also limits LTP (Roumier et al., 2004, 2008). Together these results support the interpretation that MHCI molecules play an integral role in activity-dependent plasticity specifically by enhancing synapse weakening and possibly elimination.

The role for MHCI in long-term plasticity is dependent upon the circuit analyzed. Two specific MHCI molecules, H2-Kb and H2-Db increase the threshold for LTD at parallel fiber (PF)-PC synapses in the adult cerebellum. Mice deficient in both these forms of MHCI show improved performance on the rotarod behavioral test, indicative of enhanced cerebellar plasticity (McConnell et al., 2009). Interestingly, rotarod performance at high speed is reduced in CD3ε KO mice (Nakamura et al., 2007) while similar tests on CD3ζ KO mice and PirB deficient mice show no impairments (McConnell et al., 2009). Future studies are needed to determine if and how MHCI alters long-term plasticity in different areas of the CNS using similar or distinct mechanisms.

Similar to MHCI molecules and its co-receptors, a growing number of cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β (Katsuki et al., 1990; Cunningham et al., 1996; Spulber et al., 2009), IL-2 (Tancredi et al., 1990), IL-6 (Bellinger et al., 1995; Li et al., 1997; Tancredi et al., 2000), IL-8 (Xiong et al., 2003), IL-18 (Curran and O'Connor, 2001; Alboni et al., 2010), TGFβ, and interferon-α and -β (D'Arcangelo et al., 1991; Mendoza-Fernandez et al., 2000) all inhibit hippocampal LTP. These cytokine-induced effects are dose-dependent and mediated by distinct receptors (D'Arcangelo et al., 1991). Exogenous TNFα may inhibit LTP (Tancredi et al., 1992) and LTD is abolished in mice lacking the TNF receptor (Albensi and Mattson, 2000). The role of TNFα in LTP and LTD has been questioned, however, by recent results published by two groups showing no impairment in hippocampal and cortical LTP and LTD in TNFα- and TNFR-deficient mice (Stellwagen and Malenka, 2006; Kaneko et al., 2008). IL-6 and IL-2 inhibit LTP and short-term potentiation (STP) in a dose-dependent manner (Li et al., 1997). In addition, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α regulate synaptic plasticity in models of learning and memory and have been associated with cognitive decline and dementia (Schmidt et al., 2002; Holmes et al., 2003; Dik et al., 2005). Moreover, IL-1β blocks induction of LTP in the mossy fiber CA3 pathway of mouse hippocampal slices (Katsuki et al., 1990) and this effect can be mimicked with TNF-α and LPS in slices (Katsuki et al., 1990; Cunningham et al., 1996). IL-18 depresses the amplitude of pharmacologically isolated NMDA receptor-mediated fEPSPs and impairs LTP in hippocampal slices (Curran and O'Connor, 2001). Finally, LTP induction in turn upregulates levels of IL-1β, TGFβ, and IL-6 (Jankowsky et al., 2000; Balschun et al., 2004). Thus, alterations in the levels of cytokines can profoundly change synaptic efficacy, and changes in synaptic function can alter cytokine levels. Because all of the cytokines tested so far limit LTP, it is important in the near future to determine if they act through common or distinct pathways to alter mechanisms of LTP expression.

Synaptic scaling (homeostasis)

In addition to their effects on Hebbian plasticity, immune molecules have also been implicated in the regulation of homeostatic plasticity. The concept of homeostasis is ubiquitous in biology. In order to maintain balance in any system, a method to insure that it can function independently of fluctuating environments must be in place. In neural networks, this homeostatic mechanism is known as synaptic scaling or homeostatic plasticity (Turrigiano, 2008). Synaptic scaling occurs in both cultured neurons and in hippocampal slices, although in slice it appears to be heterogeneous, varying in both a target- and afferent-specific manner (Kim and Tsien, 2008). Dynamic, activity-dependent AMPAR trafficking may underlie synaptic scaling and is seen in several experience-driven phenomena – from neuronal circuit formation to alterations of behavior (Kessels and Malinow, 2009). Synaptic homeostasis is thought to prevent positive feedback mechanisms in neural circuits from destabilizing over time and becoming hyper- or hypo-active (Desai et al., 2002; Ibata et al., 2008; Turrigiano, 2008; Gainey et al., 2009; Savin et al., 2009).

MHCI molecules have been implicated in mediating homeostatic plasticity. Blocking action potentials with tetrodotoxin (TTX) in the LGN in vivo decreases levels of MHCI mRNA (Corriveau et al., 1998) and in cultured hippocampal neurons decreases levels of MHCI protein (Goddard et al., 2007). Because neither synapsin nor PSD-95 increase in size in response to TTX in β2m/TAP1 DKO mice as they do in WT mice (Goddard et al., 2007), it has been suggested that changing MHCI levels might mediate the increase in synaptic strength caused by chronic activity blockade. Presynaptic proteins were already increased in size in these DKO mice and thus, might have occluded presynaptic-mediated synaptic scaling (Goddard et al., 2007). However, MHCI molecules are clearly important for increasing the size of postsynaptic scaffolding proteins in response to activity blockade. How these immune molecules might read out the effects of neural activity is not yet known and is one of the most exciting open questions in this field.

Although most cytokines have not yet been studied in synaptic scaling, TNFα clearly plays an important role in mediating homeostatic plasticity. Exogenous TNFα modulates synaptic strength in hippocampal neurons by rapidly promoting surface expression of AMPA receptors (Beattie et al., 2002; Stellwagen et al., 2005). TNFα secretion from glia, but not neurons, mediates the robust increase in synaptic strength in response to activity blockade with TTX (Stellwagen and Malenka, 2006). However, TNFα does not mediate the corresponding decrease in synaptic strength produced by increased neuronal activity (Stellwagen and Malenka, 2006). The ability of TNFα to alter AMPAR trafficking in response to activity-blockade is mediated through upregulation of β3 integrin expression (Cingolani and Goda, 2008). Loss of TNFα through genetic knockout or pharmacological inhibition also blocks homeostatic synaptic scaling of mEPSCs in visual cortex in acute slices and in vivo (Kaneko et al., 2008). Similarly, pharmacological blockade of TNF activity prevents the TTX-induced decrease in mIPSC amplitude, indicating that TNFα mediates homeostatic scaling of both excitatory and inhibitory synapses (Stellwagen et al., 2005; Stellwagen and Malenka, 2006). Finally, the TNFα KO mouse shows normal loss of responses to the deprived eye following monocular deprivation but no subsequent compensation by the open eye (Kaneko et al., 2008), supporting the conclusion that TNFα mediates homeostatic plasticity both in vitro and in vivo. Although there are differences in the phenotypes observed between the TNF KO and the MHCI-deficient mice, MHCI in neurons and astrocytes can be regulated by TNFα (Lavi et al., 1988; Neumann et al., 1997; Sourial-Bassillious et al., 2006), and thus some of the effects of TNF-α could be mediated by changing MHCI levels in neurons. This possible interaction underscores the importance of future work in defining the mechanisms used by these immune molecules to alter plasticity, and their potential overlapping pathways.

Implications for Neurodevelopmental Disorders

The formation of functional neuronal circuits in the CNS during development provides the substrate for human learning, memory, perception, and cognition. Improper formation or function of these synapses may lead to a number of neurodevelopmental disorders including ASD and schizophrenia. ASD and schizophrenia are complex diseases that appear to be caused by combinations of genetic changes and environmental insults during early development (Boulanger, 2004; Arion et al., 2007; Patterson, 2009). Although a wide range of environmental stimuli have been proposed to play a role in the pathogenesis of these disorders, many of these stimuli have in common the ability to alter immune function.

The link between environmental factors, the immune response, and neurological dysfunction is not completely clear at present, but it is receiving increasing attention and support. Multiple studies have associated schizophrenia and ASD with autoimmunity and allergies (Sperner-Unterweger, 2005; Arion et al., 2007). In both schizophrenia and ASD, evidence is growing that there are abnormalities in peripheral immune cells, as well as associations with specific genetic variants in cytokines, cytokine receptors, and MHCI genes (Daniels et al., 1995; Warren et al., 1996; Shi et al., 2009a; Stefansson et al., 2009). In addition, a polymorphism of the cytokine interleukin-1 (IL-1) gene complex appears to be linked to schizophrenia (Hanninen et al., 2008). Finally, interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein-like 1(IL1RAPL1) gene mutations are associated with cognitive impairment ranging from non-syndromic X-linked mental retardation to autism (Pavlowsky et al., 2010).

It is not necessary, however, that immune genes themselves be mutated to yield the alterations observed in a diseased brain, as expression and signaling of these factors can be dynamically altered by many environmental influences, including stress, infection, hormones, and brain activity. Accumulating evidence suggests that abnormalities in cytokine levels both systemically and in the CNS may be responsible for changes in brain connectivity associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. Elevated levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β have been found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), blood, and post-mortem brain tissue of people with autism (Vargas et al., 2005). These three cytokines have also been associated with schizophrenia (Monji et al., 2009) and epilepsy (Galic et al., 2008; Vezzani et al., 2008). Moreover, microglial and astrocyte activation is concurrent with cytokine up-regulation in the autistic brain and CSF (Vargas et al., 2005; Saetre et al., 2007).

Whether these increases in cytokines and/or mutations in immune molecules cause neurodevelopmental disorders is unknown. Because immune molecules directly alter development and cognition, any changes in the levels of these molecules could contribute to disease. It may be that connectivity in the CNS is altered by effects of immune molecules directly on synaptic transmission, refinement of connectivity, plasticity, and/or synaptic scaling. But what is the origin of the initial imbalance? Although neurodevelopmental disorders could cause immune dysregulation, growing evidence suggests that maternal immune activation (MIA) may lead to developmental abnormalities in the CNS. MIA has recently received much attention in the ASD field because several known factors that alter the fetal environment can increase the risk for ASD. Maternal exposure to valproic acid or thalidomide greatly increases the risk for ASD in children (Patterson, 2009) and maternal viral infection has been called “the principle non-genetic cause of autism” (Ciaranello and Ciaranello, 1995). Large-scale epidemiological studies will soon illuminate the true contribution of maternal infection to ASD. Similar data support the hypothesis that MIA might contribute to schizophrenia, including the controversial observation that maternal influenza infection during gestation may be a risk factor for schizophrenia (Mednick et al., 1988; Mak et al., 2008; Short et al., 2010).

Mouse models of MIA support the hypothesis that a peripheral immune response during development alters CNS structure and function. Adult offspring of pregnant mice given intra-nasal influenza virus on embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5) exhibit behavioral abnormalities including a deficit in social interaction, reluctance to interact with a novel object, deficient prepulse inhibition and increased anxiety under mildly stressful conditions (Shi et al., 2003), as well as changes in brain structure (Fatemi et al., 2002; Shi et al., 2003; Fatemi et al., 2008; Shi et al., 2009b). Many of these abnormalities are similar to those associated with ASD and schizophrenia. Because the virus was not detected in the fetus in this mouse model, it is the maternal immune response to influenza infection that causes these behavioral abnormalities (Shi et al., 2005). Indeed, many of these abnormal behaviors can also be elicited in the absence of infection by activating the maternal immune response with synthetic dsRNA (polyI:C) injection, which acts to initiate an inflammatory response similar to that caused by viral infection (Shi et al., 2003). The hallmark structural abnormality in schizophrenia, ventricular enlargement, is also observed in the poly (I:C) MIA mouse model along with a delay in hippocampal myelination (Jaaro-Peled et al., 2007; Piontkewitz et al., 2007). Other neuropathological changes identified include reduced NMDA receptor expression in hippocampus and enhanced tyrosine hydroxylase in striatal structures. In the prefrontal cortex, the numbers of reelin- and parvalbumin-positive cells as well as dopamine D1 and D2 receptors were also reduced (Meyer et al., 2008a,b). Adult offspring display increased levels of GABAA receptor α2 immunoreactivity and dopamine hyperfunction as seen in schizophrenia (Yee et al., 2005). Importantly, the timing of MIA determines the nature and extent of the neuropathology and behavioral outcome (Meyer et al., 2006; Fatemi et al., 2008), as well as the types of cytokines that are acutely activated within hours of MIA (Meyer et al., 2006).

Cytokines released by the mother's immune response can cross the placenta and cause the pathological and behavioral changes exhibited by virally infected or PolyI:C-injected mice (Patterson, 2002). LPS-induced MIA alters placental cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) and induces cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN) in the fetus. Specifically, IL-6 is upregulated in the placenta and amniotic fluid after MIA and it can cross the BBB in early to mid-gestation (Smith et al., 2007; Patterson, 2009). IL-6 injection of pregnant dams in mid-gestation mimics the effects of immune activation on neuropathology and behavior, and the effects of PolyI:C on fetal brain development and subsequent behavior are prevented by co-injection of an IL-6 antibody (Smith et al., 2007). Moreover, maternal injection of poly (I:C) in an IL-6 knockout mouse results in offspring with normal behavior. In addition to preventing the development of abnormal behaviors, the IL-6 antibody also blocks the changes in brain transcription induced by maternal poly (I:C) (Smith et al., 2007). These elegant studies demonstrate that elevation of maternal cytokines during gestation can cause neuropathology and abnormal behaviors in offspring consistent with several neurodevelopmental disorders, including schizophrenia and ASD.

Despite recent progress in developing and characterizing mouse models of MIA, little is known about how maternal cytokines alter fetal brain development. One possibility is that maternal cytokines cross into the fetal brain, where they cause neuroinflammation (Patterson, 2009). Several reports have recently identified increases in cytokine levels in fetal brain following MIA, but these studies were performed only shortly after PolyI:C injection (2–4 h), pooled multiple brain areas, and focused on only a few cytokines (Gilmore et al., 2005; Meyer et al., 2006; Patterson, 2009). These reports found significant increases in IL-1β and IL-6 in fetal brains 6 h after maternal PolyI:C injection (Meyer et al., 2006). Another recent report showed that IL-6 levels are increased in the fetal brain after multiple IL-6 injections of pregnant rats and remain elevated in these offspring at 4 and 24 weeks of age (Patterson, 2009). This chronic elevation of a cytokine in the fetal rat brain is similar to the chronic elevation of a panel of cytokines and chemokines found in the brains and CSF of autistic individuals. IL-6, IL-10, and TGFβ (out of 13 cytokines tested) were significantly increased in cortical tissue of autistic individuals, while 10 out of 20 chemokines were elevated in autistic brain, including MCP-1 (also called CCL2; Vargas et al., 2005). In another study, TNFα was elevated in CSF from 10 autistic children with a history of regression (Chez et al., 2007). Finally, many immune-related genes, including several cytokines, their receptors, and other elements of their signaling pathways, have been reported to be elevated in serum from autistic individuals compared to controls (Pardo et al., 2005; Ashwood et al., 2006; Garbett et al., 2008; Meyer et al., 2008a; Enstrom et al., 2009). Together, these data support the hypothesis that MIA leads to chronic neuroinflammation that alters CNS development and behavior and may contribute to neurodevelopmental disorders (Patterson, 2002, 2009).

Although viruses and bacteria cannot cross the placenta, some cytokines can. In the poly (I:C) MIA model, IL-6 crosses the placenta and induces an immunological response in the unborn fetus and developing brain. During development in utero, the brain is extremely vulnerable (Oliver et al., 1997). Not only is it not fully developed until well after birth, but the BBB is highly permeable during this critical time. Gene and protein expression in the brain suggest a precise temporal and spatial role for immune modulators during this period. A surge in immune activation early in development may be extremely detrimental, if not fatal (Korteweg and Gu, 2008; Basurko et al., 2009; Carcopino et al., 2009). If brain circuits are altered during a later developmental window, gross defects may be spared, but more subtle changes, perhaps affecting synaptic strength or plasticity may occur. Intriguingly, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α, elevated in neurodevelopmental disorders, are known to serve specific functions in synaptic plasticity and cognitive processes (see above).

Immune dysregulation in neurodevelopmental disorders is not only seen as a correlation to an initial insult, but may occur throughout the lifespan of the individual. What is the impact of chronic neuroinflammation? It may be that the similarities between the nervous and immune systems provide insight into this question. The developing immune system may be as vulnerable during this developmental window as the nervous system. A fetus’ immunity in utero is poorly developed, what little defenses it does have are contiguous with its mother (Inman et al., 2010). Infants have the capability to develop some responses to antigens at birth, but a lot of their initial immunity is passively acquired from their mother during pregnancy and after, from breast milk (Goldman et al., 1996; Srivastava et al., 1996; Wallace et al., 1997; Garofalo and Goldman, 1998; Hawkes et al., 1999; Garofalo, 2010). The immune system is composed of a detailed network of balanced cascades. If this delicate balance is disrupted during this critical time of life, in utero and during the postpartum period, it may cause permanent deficits resulting in an imbalance and hyper-responsiveness manifested as immune dysregulation accompanied by neuroinflammation throughout life.

Final Thoughts

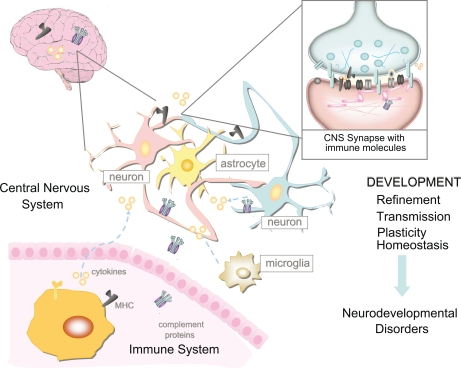

The relationship between the immune and nervous systems is much more complicated than once thought (Figure 3). Immune molecules mediate essential nervous system functions during healthy development independent of immune and inflammatory processes (Bauer et al., 2007; Boulanger, 2009). The immune system appears to influence the nervous system during typical functioning and in disease. Chronic infection or severe illness may disrupt the balance of normal neural–immune cross-talk resulting in permanent structural changes in the brain during development, and/or contributing to pathology later in life. The diversity, promiscuity, and redundancy of “immune” signaling molecules allow for a complex coordination of activities and precise signaling pathways, fundamental to both the immune and nervous systems. However, the sheer number of immune molecules that could be important for nervous system development and function is staggering. Although much progress has been made in the past 10 years in our appreciation that immune molecules play critical roles in the healthy brain, the large majority of immune molecules have not yet been studied for their presence and function in the brain. For the immune molecules that we know are important, almost nothing is understood about their mechanisms of action. There is no doubt that many immune molecules will change their functions over development and will affect one another, but how this will affect neural function and development is also completely unknown. Rapid progress in this newly energized and exciting field holds tremendous promise not only for enhancing our understanding of typical development, but also for elucidating and potentially even treating neuropsychiatric disorders.

Figure 3.

The relationship between the immune system and nervous system is highly complicated. However, it is now apparent that immune molecules not only cross the blood–brain barrier in times of injury, but are expressed during normal brain development. Recent evidence suggests roles for MHCI and its receptors, complement, and cytokines on the function, refinement, and plasticity of cortical and hippocampal synapses. These functions for immune molecules during neural development suggest that they could also mediate pathological responses to chronic elevations of cytokines in neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and schizophrenia.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Daniel Braunschweig, Samantha Spangler, Stephanie Barrow, Leigh Needleman, Brad Elmer, and Myka Estes for comments on the manuscript and Cure Autism Now, the Higgins Family Foundation, The Bernard Gassin Family Foundation, the John Merck Fund, Autism Speaks, and NARSAD for funding our research into the roles for immune molecules in synapse formation.

References

- Abbas A, Lichtman A. H., Pober J. (2000). Cellular and Molecular Immunology. Philadelphia, PA: W.E. Saunders Company [Google Scholar]

- Albensi B. C., Mattson M. P. (2000). Evidence for the involvement of TNF and NF-kappaB in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Synapse 35, 151–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alboni S., Cervia D., Sugama S., Conti B. (2010). Interleukin 18 in the CNS. J. Neuroinflammation 7, 9. 10.1186/1742-2094-7-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amantea D., Nappi G., Bernardi G., Bagetta G., Corasaniti M. T. (2009). Post-ischemic brain damage: pathophysiology and role of inflammatory mediators. FEBS J. 276, 13–26 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06766.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arion D., Unger T., Lewis D. A., Levitt P., Mirnics K. (2007). Molecular evidence for increased expression of genes related to immune and chaperone function in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 62, 711–721 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwood P., Wills S., Van de Water J. (2006). The immune response in autism: a new frontier for autism research. J. Leukoc. Biol. 80, 1–15 10.1189/jlb.1205707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwal J. K., Pinkston-Gosse J., Syken J., Stawicki S., Wu Y., Shatz C., Tessier-Lavigne M. (2008). PirB is a functional receptor for myelin inhibitors of axonal regeneration. Science 322, 967–970 10.1126/science.1161151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balschun D., Wetzel W., Del Rey A., Pitossi F., Schneider H., Zuschratter W., Besedovsky H. O. (2004). Interleukin-6: a cytokine to forget. FASEB J. 18, 1788–1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barco A., Patterson S., Alarcon J. M., Gromova P., Mata-Roig M., Morozov A., Kandel E. R. (2005). Gene expression profiling of facilitated L-LTP in VP16-CREB mice reveals that BDNF is critical for the maintenance of LTP and its synaptic capture. Neuron 48, 123–137 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basurko C., Carles G., Youssef M., Guindi W. E. (2009). Maternal and fetal consequences of dengue fever during pregnancy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 147, 29–32 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S., Kerr B. J., Patterson P. H. (2007). The neuropoietic cytokine family in development, plasticity, disease and injury. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 221–232 10.1038/nrn2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie E. C., Stellwagen D., Morishita W., Bresnahan J. C., Ha B. K., Von Zastrow M., Beattie M. S., Malenka R. C. (2002). Control of synaptic strength by glial TNFalpha. Science 295, 2282–2285 10.1126/science.1067859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger F. P., Madamba S. G., Campbell I. L., Siggins G. R. (1995). Reduced long-term potentiation in the dentate gyrus of transgenic mice with cerebral overexpression of interleukin-6. Neurosci. Lett. 198, 95–98 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11976-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat R., Steinman L. (2009). Innate and adaptive autoimmunity directed to the central nervous system. Neuron 64, 123–132 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger L. M. (2004). MHC class I in activity-dependent structural and functional plasticity. Neuron Glia Biol. 1, 283–289 10.1017/S1740925X05000128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger L. M. (2009). Immune proteins in brain development and synaptic plasticity. Neuron 64, 93–109 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger L. M., Shatz C. J. (2004). Immune signaling in neural development, synaptic plasticity and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 521–531 10.1038/nrn1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger L. M., Huh G. S., Shatz C. J. (2001). Neuronal plasticity and cellular immunity: shared molecular mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 11, 568–578 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00251-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryceson Y. T., Foster J. A., Kuppusamy S. P., Herkenham M., Long E. O. (2005). Expression of a killer cell receptor-like gene in plastic regions of the central nervous system. J. Neuroimmunol. 161, 177–182 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brynskikh A., Warren T., Zhu J., Kipnis J. (2008). Adaptive immunity affects learning behavior in mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 22, 861–869 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell D. (1996). T cell antigen receptor signal transduction pathways. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 14, 259–274 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcopino X., Raoult D., Bretelle F., Boubli L., Stein A. (2009). Q Fever during pregnancy: a cause of poor fetal and maternal outcome. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1166, 79–89 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04519.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier P. A., Palmer T. D. (2009). Immune influence on adult neural stem cell regulation and function. Neuron 64, 79–92 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson M. J., Doose J. M., Melchior B., Schmid C. D., Ploix C. C. (2006). CNS immune privilege: hiding in plain sight. Immunol. Rev. 213, 48–65 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00441.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charron F., Tessier-Lavigne M. (2007). The Hedgehog, TGF-beta/BMP and Wnt families of morphogens in axon guidance. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 621, 116–133 10.1007/978-0-387-76715-4_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chez M. G., Dowling T., Patel P. B., Khanna P., Kominsky M. (2007). Elevation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in cerebrospinal fluid of autistic children. Pediatr. Neurol. 36, 361–365 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciaranello A. L., Ciaranello R. D. (1995). The neurobiology of infantile autism. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 101–128 10.1146/annurev.ne.18.030195.000533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani L. A., Goda Y. (2008). Differential involvement of beta3 integrin in pre- and postsynaptic forms of adaptation to chronic activity deprivation. Neuron Glia Biol. 4, 179–187 10.1017/S1740925X0999024X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]