Abstract

GABAergic interneuronal network activities in the hippocampus control a variety of neural functions, including learning and memory, by regulating θ and γ oscillations. How these GABAergic activities at pre- and postsynaptic sites of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells differentially contribute to synaptic function and plasticity during their repetitive pre- and postsynaptic spiking at θ and γ oscillations is largely unknown. We show here that activities mediated by postsynaptic GABAARs and presynaptic GABABRs determine, respectively, the spike timing- and frequency-dependence of activity-induced synaptic modifications at Schaffer collateral-CA1 excitatory synapses. We demonstrate that both feedforward and feedback GABAAR-mediated inhibition in the postsynaptic cell controls the spike timing-dependent long-term depression of excitatory inputs (“e-LTD”) at the θ frequency. We also show that feedback postsynaptic inhibition specifically causes e-LTD of inputs that induce small postsynaptic currents (<70 pA) with LTP-timing, thus enforcing the requirement of cooperativity for induction of long-term potentiation at excitatory inputs (“e-LTP”). Furthermore, under spike-timing protocols that induce e-LTP and e-LTD at excitatory synapses, we observed parallel induction of LTP and LTD at inhibitory inputs (“i-LTP” and “i-LTD”) to the same postsynaptic cells. Finally, we show that presynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition plays a major role in the induction of frequency-dependent e-LTD at α and β frequencies. These observations demonstrate the critical influence of GABAergic interneuronal network activities in regulating the spike timing- and frequency-dependences of long-term synaptic modifications in the hippocampus.

Keywords: STDP, CA1, GABA, spike timing, frequency, hippocampal oscillation

Introduction

GABAergic interneuronal network activities regulate a variety of neural functions, such as modulation of activity-dependent synaptic plasticity (Meredith et al., 2003), i.e., long-term potentiation (LTP) and depression (LTD), and serve as a driving force for the hippocampal θ and γ oscillations important for processing learning and memory (Buzsáki, 2002; Csicsvari et al., 2003; Lisman et al., 2005). GABA functions as a major inhibitory neurotransmitter at both excitatory (glutamatergic) and inhibitory (GABAergic) neurons in the central nervous system by activating GABAA receptors (GABAARs) and GABAB receptors (GABABRs) in both pre- and postsynaptic cells (Connors et al., 1988; Davies and Collingridge, 1996). However, the inhibitory function of GABA on postsynaptic GABAARs depends on the state of the Cl− ion reversal potential relative to the resting membrane potential (Staley et al., 1995). For example, in the hippocampus, GABAergic inhibition induced by stimuli at the α/β (low, 10 Hz) frequency shifts to excitation when stimuli occur at the γ (high, 40 Hz) frequency as a consequence of intracellular Cl− ion ([Cl−]i) accumulation in postsynaptic CA1 pyramidal cells (Staley et al., 1995; Bracci et al., 2001). In addition, GABA inhibition through presynaptic GABABRs, which are linked to G-protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRK), imposes different frequency dependencies at excitatory and inhibitory presynaptic terminals that are effective, respectively, above the α/β frequency (Ohliger-Frerking et al., 2003) and near the θ frequency (Davies and Collingridge, 1996).

In hippocampal neural networks, different populations of GABAergic interneurons (Maccaferri et al., 2000; Klausberger and Somogyi, 2008) contribute to postsynaptic feedforward (FF) and feedback (FB) inhibition at CA1 pyramidal cells (Pouille and Scanziani, 2001, 2004) and to presynaptic inhibition at excitatory and inhibitory presynaptic terminals to CA1 pyramidal cells. However, it is unknown how these distinct GABA actions affect excitatory synaptic gains, either differentially or synergistically. Depending on the precise timing of pre- and postsynaptic neuronal spikes, repetitive spiking reliably induces either LTP or LTD, collectively known as spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP), in hippocampal neurons in culture (Bi and Poo, 1998; Debanne et al., 1998), in hippocampal or cortical neurons in slices (Markram et al., 1997; Feldman, 2000; Nishiyama et al., 2000; Sjöström et al., 2001; Froemke and Dan, 2002; Woodin et al., 2003), and in neurons of the tectum in vivo (Zhang et al., 1998). Previously, we showed that at hippocampal Schaffer collateral (SC)-CA1 pyramidal cell excitatory synapses, STDP induced by stimuli at 5 Hz (θ frequency) is composed of two distinct LTD time intervals (−LTD: −28 to −16 ms and +LTD: +15 to +20 ms) that flank an LTP time interval (−2 to +15 ms) (Nishiyama et al., 2000). Interestingly, this LTP/LTD time interval cycle is completed within 25 ms at 40 Hz (γ frequency), similar to the time course of the γ oscillation in vivo (Csicsvari et al., 2003), which hippocampal GABAergic interneuronal networks are believed to regulate (Whittington et al., 1995; Bartos et al., 2007; Cardin et al., 2008; Sohal et al., 2008). Also, repetitive stimuli at SC inputs persistently alter synaptic efficacy at GABAergic inputs to CA1 pyramidal cells (Woodin et al., 2003; Chevaleyre and Castillo, 2004; Lamsa et al., 2005; Gibson et al., 2008). We, therefore, monitored synaptic efficacy at CA1 pyramidal cells to investigate how these dynamic patterns of GABAergic interneuronal inputs regulate spike timing- and frequency-dependent STDP at excitatory synapses (e-STDP).

Materials and Methods

Hippocampal slice preparation

Hippocampal slices were prepared by a standard procedure (Nishiyama et al., 2000). Male Sprague-Dawley rats (26- to 35-day old) were anaesthetized and decapitated. Right hippocampi were dissected rapidly and placed in a gassed (95% O2–5% CO2) extracellular solution containing (in mM) 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2.6 CaCl2, 1.3 MgSO4, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 22 NaHCO3 and 10 D-glucose at 10°C. Transverse slices of 500-μm thickness were cut with a rotor tissue slicer (Dosaka, DTY7700) and maintained at room temperature (23–26°C) in an incubation chamber for at least 2 h. For experiments, individual slices were transferred to a submersion recording chamber and perfused continuously with extracellular solution (4.0∼4.5 ml/min) at room temperature. Experiments using a K+-based internal recording solution (see below) were performed at 30–33°C. To prevent epileptiform activity, the CA3 region was removed in experiments that used GABA and muscarinic receptor antagonists.

Whole-cell recording

Whole-cell recordings were made in the CA1 cell body layer with the “blind” patch clamp method, using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Inst.). Test stimuli were applied at 0.05 Hz and alternated between two non-overlapping SC inputs using bipolar electrodes (MCE-100, RMI) under voltage-clamp (Vc = −80 mV) [except when inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) were measured] to evoke excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs). Both stimulating electrodes were positioned at the stratum radiatum at least 500 μm distant from the recording electrode to avoid stimulation of monosynaptic (direct) inhibitory inputs. The non-overlap of the two inputs was confirmed by applying alternate paired-pulse test stimuli (at 50-ms intervals) to demonstrate the absence of cross facilitation between the two inputs. Constant current pulses (amplitude, 6–14 μA; duration, 300 μs) evoked EPSCs with amplitudes of 100–200 pA. These current intensities were at least three fold smaller than the stimulation currents that evoke population spikes. Following a stable recording period of about 12 (K+-based internal recording solution) or 15 (Cs+-based internal recording solution) min, the recording was switched to current clamp and a train of stimuli at a frequency of 5 Hz was delivered to one of the two inputs for either 20 s (K+-based) or 16 s (Cs+-based). Each presynaptic stimulus was paired with the injection of a spike-form (K+-based: 2 nA for 2 ms at the peak, Imax) or square (Cs+-based: 2 nA for 2 ms) depolarizing current pulse into the postsynaptic neuron to initiate spiking at various time intervals. The spike-form depolarizing currents (t in ms): Imax·10·t, 0 ≤ t < 0.1; Imax, 0.1 ≤ t < 2.1; Imax·[(1−(0.8/1.5)·(t−2.1)], 2.1 ≤ t < 3.6; Imax·[0.2−(0.12/2)·(t−3.6)], 3.6 ≤ t < 5.6; Imax·0.08·[1−(1/2.5)·(t−5.6)], 5.6 ≤ t < 8.1 were designed to reduce the jitter of postsynaptic spikes but not to affect the spike decay time. Depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI) was induced by changing Vc from −80 to 0 mV for 2–3 s, followed by the application of the spike-timing protocol (at 5-, 12- and 25-Hz for 16, 6.7 and 3.2 s, respectively) for various time intervals after 5–10 s. A voltage-step of +90 mV from the holding potential (at −80 mV) was applied for 40 ms every 60 s to visualize feedforward (FF)-IPSCs during the concurrent monitoring of EPSC/FF-IPSC. A 40-ms voltage-step was chosen to avoid the induction of DSI (estimated to be less than 1% according to Lenz and Alger, 1999) but was long enough to detect peak currents of disynaptic FF-IPSCs. During this voltage-step, EPSC was masked because the commanding potential (i.e., +10 mV) was approximately equivalent to the EPSC reversal potential. The identity of FF-IPSC was confirmed as a result of its abolition by bath-applied gabazine (10–100 μM) and kynurenic acid (5 mM). Data were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz. Patch electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass (1.2-mm O.D.) and had a resistance of 3.5∼6 MΩ. Pipettes were filled with a solution containing (in mM): 120 K-gluconate, 10 KMeSO3, 10 KCl, 0.075 BAPTA, 20 HEPES, 4 Mg-ATP, 2 Na2-ATP, pH adjusted to 7.35 with KOH. For experiments that required sustained postsynaptic depolarization, a Cs+-based internal solution was used that contained (in mM): 130 cesium methanesulphonate (CsMeSO3), 10 tetraethylammonium (TEA) chloride (Cl−), 0.25 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA), 10 N-[1-hydroxyethyl]-piperazine-N’-[2-ethanesulphonic acid] (HEPES), 2 Mg-ATP, 2 Na2-ATP, pH adjusted to 7.35 with CsOH,. The series resistance (typically 10–14 MΩ) was compensated 50–80% and was monitored throughout the experiment using a −5 mV step command. Cells that showed an unstable series resistance (>20% changes after the spike-timing protocol) were not used. To monitor monosynaptic IPSCs, 40 μM CNQX and 50 μM D(–)-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (AP5) were present in the extracellular solution and CsCl instead of CsMeSO3 was used intracellularly while the cells were held at −70 mV. Drugs (bicuculline, kynurenic acid, gabazine, CNQX, AP5 and phaclofen) were purchased from either RBI or Tocris. CGP35348 was a generous gift from Novartis.

Results

Single, pre- and postsynaptic spiking at the θ frequency recruits both feedforward and feedback postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition

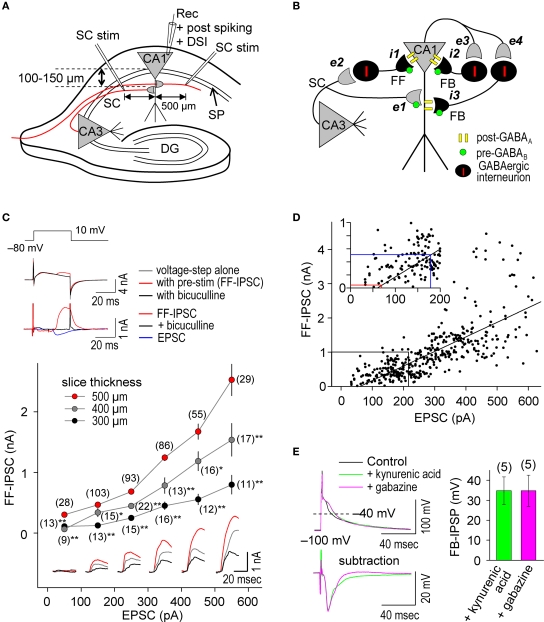

We performed whole-cell recordings at CA1 pyramidal cells in hippocampal slices (Figure 1A) in which the GABAergic networks are well defined (Figure 1B) (Maccaferri et al., 2000; Pouille and Scanziani, 2001, 2004; Klausberger and Somogyi, 2008). We stimulated SC inputs in the stratum radiatum at 100–150 μm away from the stratum pyramidale (SP, somatic layer) to evoke both EPSCs and FF-IPSCs in 500 μm thick slices. We used a CsMeSO3-based (Cs+-based) internal solution, which blocks GIRKs, to isolate the effects of postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition from those of postsynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition. In this configuration, we found that substantially more GABAergic inputs relative to glutamatergic inputs were retained than in thinner (300 and 400 μm) slices (Figure 1C); the FF-IPSC amplitude was 1045 ± 44 pA when the EPSC amplitude was 301 ± 8 pA (±sem, n = 408; differences between commanding and reversal potentials were ca. 90 mV for both FF-IPSCs and EPSCs) (Megias et al., 2001). Consistent with the idea that monosynaptic EPSCs and disynaptic FF-IPSCs normally share the same population of SC inputs in our experimental paradigm, the magnitudes of both EPSCs and FF-IPSCs changed in positive correlation with the magnitudes of presynaptic stimuli at SC inputs (Figures 1C,D). Weak, superlinearly- increased FF-IPSC amplitudes, greater than those of EPSCs, were observed when strong stimuli were applied to SC inputs (i.e., EPSC amplitudes >300 pA; Figure 1D, bottom). This superlinearity, the mechanism for which is unknown, may help to facilitate the failure of LTP induction at strong inputs, which has been demonstrated in cultured hippocampal neurons (Bi and Poo, 1998) and is believed to maintain gain levels of the entire network activity (van Rossum et al., 2000). It is noteworthy that as presynaptic stimulation was decreased, FF-IPSCs disappeared at a level at which EPSCs of ∼70 pA remained (see Figure 1D inset), indicating that e-STDP can be examined in the absence of functional FF-IPSCs to individually-recorded pyramidal cells.

Figure 1.

Repetitive, single pre- and postsynaptic spiking recruits both FF and FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. (A) Experimental paradigm depicting the positions of stimulating and recording electrodes. Whole-cell recordings were made in the CA1 cell body and the test stimuli were applied at the stratum radiatum at least 500 μm distant from the recording electrode. (B) Schematic diagram of neuronal networks involved in the induction of STDP in CA1 pyramidal cells. Locations of excitatory (e) and inhibitory (i) inputs and GABA receptors are indicated. (C) Procedure for concurrent measurement of EPSCs and FF-IPSCs (top) and summary of their amplitudes (bottom). FF-IPSC is detected (top middle) with the use of voltage-steps (top upper) and presynaptic stimulation (pre-stim). The magnitude of FF-IPSC (top lower, black) is calculated by subtracting the voltage-step alone (top middle, black) from the pre-stimulation value (top middle, blue). The voltage-step at +10 mV was applied for 40 ms to prevent the induction of DSI (less than 1%; Lenz and Alger, 1999). The FF-IPSC was confirmed by GABAA blockade with bicuculline (20 μM, top middle and lower, red). The ratio of FF-IPSCs to EPSCs increased as the slice thickness increased. Data represent the mean EPSC/FF-IPSC (±sem). Traces: FF-IPSC in 500-μm (red), 400-μm (gray) and 300-μm (black) thick slices. The (number) indicates the total number of trials. Significant differences from corresponding data in 500-μm thick slices are indicated (“*” p < 0.05 and “**” p < 0.01; Mann–Whitney U test). (D) The amplitude of FF-IPSC is proportional to the EPSC amplitude. When the EPSC level is <70 pA, there is no FF-IPSC (see red line in inset). The EPSC amplitude normally used in this study is indicated (blue line in inset). (E) Prominent FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition is recruited by repetitive 5-Hz postsynaptic spiking in CA1 pyramidal cells. Postsynaptic spiking was induced by depolarizing current injections (6 nA, 2 ms, 20 pulses at 5 Hz) while postsynaptic CA1 pyramidal cells were held at −100 mV in a current-clamp configuration using a Cs+-based internal recording solution. The top left panel shows the postsynaptic membrane potentials monitored when FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition was blocked by either kynurenic acid (5 mM) or gabazine (10 μM). The control, in which GABAAR was not blocked, showed a feedback inhibition-inclusive membrane potential. Subtraction analysis (bottom left) revealed a membrane potential resulting from FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition. Average FB-IPSP (right).

To ascertain whether FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition occurred during the θ frequency (5 Hz) spike-timing protocol, we injected postsynaptic spike-inducing depolarizing currents (6 nA for 2 ms) through the whole-cell recording electrodes for 20 pulses (at 5 Hz) in the absence of presynaptic stimuli. The recorded cell was held at −100 mV under the current clamp to avoid sustained depolarization after spikes in the absence of K+ channel function. Feedback postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated membrane hyperpolarization was measured as differential potentials in which the spike afterpotential (averaged between the 15th and 20th spikes) in the presence of either gabazine (10–100 μM), a GABAAR antagonist, or kynurenic acid (5 mM), a glutamate receptor antagonist (to eliminate disynaptic responses), was subtracted from that in the absence of antagonists (Figure 1E). We observed a FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated hyperpolarizing effect of ca. −34 mV when cell membrane potentials were at ca. −40 mV, demonstrating the occurrence of functional FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition. Thus, our experimental paradigm is a unique method to investigate differential GABAergic effects (e.g., pre- vs. postsynaptic, GABAAR- vs. GABABR-mediated and FF vs. FB) on the induction of e-STDP.

e-STDP induced at the θ frequency is independent of postsynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition

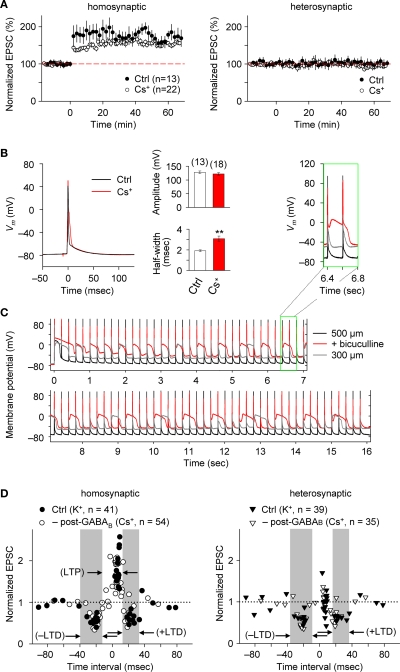

Blocking postsynaptic K+ channel activity, including that linked to GABABR function, may also affect the spike-timing dependence of e-STDP. We, therefore, examined the timing-dependent feature of e-STDP using a K-gluconate-based (control) internal solution in the recording pipette. We applied SC stimulation that evoked EPSCs of amplitude >70 pA to ensure the presence of functional FF-IPSCs (Figure 1D). When presynaptic stimuli at SC-CA1 synapses were paired with postsynaptic spike-inducing depolarizing currents with a time interval of +5 ms at 5 Hz for 20 s, we observed input-specific e-LTP (Figure 2A), which was comparable to that induced by a 16-s spike-timing protocol (at positive time interval) in the Cs+-based internal solution (Figure 2A). That a comparable LTP was induced is likely attributable to the fact that activated postsynaptic sites were close enough to the soma to receive back-propagating action potentials due to the absence of prominent A-type K+ channel activity (Hoffman et al., 1997). These conditions permit repetitive, single pre- and postsynaptic spiking to induce e-LTP (Nishiyama et al., 2000).

Figure 2.

e-STDP is induced at the θ frequency independently of postsynaptic GABABR function at SC-CA1 synapses. (A) Time course of changes in EPSC amplitudes induced by the LTP-timing protocol in homosynaptic, activated inputs (left) and heterosynaptic, non-activated inputs (right). Input-specific e-LTP was observed in K+-based (control, Ctrl) and Cs+-based internal recording solution. Data represent the normalized mean EPSC (±sem). (B) Action potentials recorded at the soma with the LTP time intervals in the presence or absence of K+ channel activities. Membrane potential (Vm) changes in either K+-based (black) or Cs+-based (red) internal solution (left). The average spike amplitude (right upper) and the half maximum width (right lower) were not as significantly different between the two experimental conditions as reported previously (Wittenberg and Wang, 2006). This may be due to extensive postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition in our preparation. Significant difference from the control is indicated (“**” p < 0.01; Mann–Whitney U test). (C) Membrane potentials (Vm) controlled by GABAAR-mediated inhibition. Stable Vm was observed in 500-μm (black), but not in 300-μm (gray) thick hippocampal slices in which elimination of postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition by bicuculline (20 μM) treatment caused depolarization (red). Inset: twice magnified view. (D) Summary of normalized EPSC changes in homosynaptic (left) and heterosynaptic (right) inputs. A similar timing dependence of e-STDP was observed in both K+-based (Ctrl) and Cs+-based (–post-GABAB; without postsynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition) internal solution. e-LTD at both negative and positive time intervals propagated to heterosynaptic, non-activated synapses (right). Gray areas indicate e-LTD time intervals in the K+-based internal solution. Data recorded in the Cs+-based internal solution is adapted from (Nishiyama et al., 2000).

We also compared the postsynaptic spike wave forms during the LTP-timing protocol in the Cs+-based internal solution with those in the K+-base internal solution (Figure 2B). In the Cs+-based internal solution, the spikes evoked by the postsynaptic depolarizing currents were ca. 50% broader (half-maximal width of 3.1 ± 0.3 ms, n = 18) than in the K+-based solution. However, this spike width is noticeably smaller than that reported previously in thinner (300 μm) slices (Wittenberg and Wang, 2006). Moreover, membrane potential changes recorded in the postsynaptic cell during the LTP-timing protocol were stably maintained, even when the Cs+-based internal solution was used, in 500-μm thick slices (Figure 2C). In contrast, a strong depolarization was observed when we applied the same spike-timing protocol in thinner (i.e., 300-μm thick) slices or slices (500-μm thick) treated with 20 μM bicucullin, which eliminated postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition (Figure 2C). Collectively, the observations of relatively small spike width and stable postsynaptic membrane potential in the Cs+-based internal solution support the presence of prominent postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition that accelerated spike after-repolarization.

We systematically examined the spike-timing dependence of e-STDP at the θ frequency. As shown in Figure 2D, we observed two distinct time windows for the induction of e-LTD, −31 to −18 ms (–LTD) and +18 to +34 ms (+LTD), that flanked single time intervals of +3 to +9 ms for the induction of e-LTP. Moreover, the induction of e-LTD for both negative and positive time intervals at activated synapses was associated with heterosynaptic e-LTD at non-activated synapses. Although a broader time window for +LTD (20 ms duration) was observed in the K+-based internal solution, the timing dependence of this e-STDP was similar to that in the Cs+-based internal solution (in the absence of postsynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition, Figure 2D; modified from Nishiyama et al., 2000 by the addition of new data points). This suggests that postsynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition-linked GIRKs and other K+ channel activities, including that of A-type K+ channels, are not essential determinants of the spike-timing dependence of e-STDP induced at the θ frequency.

Postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition controls the spike-timing dependence of e-LTD

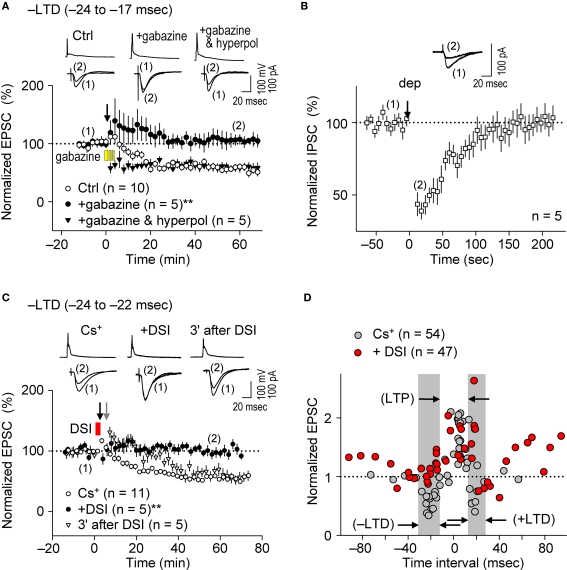

The induction of STDP depends on the pattern of postsynaptic Ca2+ elevation (Magee and Johnston, 1997; Nishiyama et al., 2000; Sjöström and Nelson, 2002; Dan and Poo, 2006; Nevian and Sakmann, 2006; Caporale and Dan, 2008), which results from interactions between dendritic back-propagating action potentials and excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) (Koester and Sakmann, 1998; Schiller et al., 1998; Stuart and Häusser, 2001). Since dendritic action potentials are regulated by FF and FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition (Buzsáki et al., 1996; Tsubokawa and Ross, 1996; Pouille and Scanziani, 2001), we examined whether postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition affects the spike-timing dependence of e-STDP induced at the θ frequency. We first investigated the impact of postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition on the induction of e-LTD (–LTD; Figure 2D), in the K+-based internal solution as a control. To eliminate postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition, gabazine (5 μM), a GABAAR antagonist (Pouille and Scanziani, 2004), was administrated in the bath a few minutes before the spike-timing protocol and remained throughout the e-LTD induction protocol. As shown in Figure 3A, e-LTD was abolished in the presence of gabazine, demonstrating that GABAAR activity is required for the induction of e-LTD. To confirm that postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated membrane hyperpolarization was responsible for the e-LTD induction, the recorded cells were held at −85 mV (in current clamp) while postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition was blocked by bath-applied gabazine. The reversal potential of GABAAR was −73.8 ± 3.1 mV (n = 4), when the Cs+-based internal solution was used. Application of hyperpolarizing currents to the recorded cells restored the induction of e-LTD, which, unlike in the control, was expressed immediately after the spike-timing protocol (Figure 3A). The slow onset of e-LTD in the presence of GABAAR function may be due to robustly enhanced FF-IPSCs immediately after the spike-timing protocol (see Figure 5C), the FF-IPSC component of which is expected to be 14.5 ± 0.8% of the EPSC amplitude (n = 4) before the induction protocol.

Figure 3.

Postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition controls the spike-timing dependence of e-LTD at the θ frequency. (A) Bath application of gabazine (5 μM, yellow bars) abolished e-LTD (time intervals: −24 to −17 ms), whereas hyperpolarization (hyperpol) of postsynaptic cells restored e-LTD. (B) Brief postsynaptic depolarization (arrow; dep, 3 s) induced DSI at SC inputs. (C) DSI (red bar) induction immediately preceding the spike-timing protocol (black arrow) abolished e-LTD (time intervals: −24 to −22 ms), whereas DSI applied 3 min before (gray arrow) had no effect on the e-LTD. Data represent normalized mean EPSCs/IPSCs (±sem). Sample traces of membrane potentials during the spike-timing protocol (top, in A,C) and of IPSCs (in B)/EPSCs (bottom, in A,C) before (1) and after (2) the induction protocols. Significant differences from corresponding controls are indicated (“**” p < 0.01; Mann–Whitney U test). (D) Summary of time windows for e-STDP in the presence (filled red circle) and absence (filled gray circle) of DSI. Gray areas show LTD time intervals in the absence of DSI.

Figure 5.

Parallel induction of e-LTP/i-LTP and e-LTD/i-LTD occurs under prominent postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition. (A) Normalized EPSC/FF-IPSC amplitudes (%) without the spike-timing protocol. No changes in either EPSCs or FF-IPSCs were observed during the time course of the experiments. (B,C) EPSCs and FF-IPSCs were both potentiated at the LTP time intervals (B), and depressed at the –LTD time intervals (C). (D) DSI abolished LTD of EPSC, but not of FF-IPSC at the –LTD time intervals. Data represent normalized mean EPSCs/FF-IPSCs (±sem). Sample traces of EPSCs/FF-IPSCs (in B–D) before (1) and after (2) the induction protocols. Significant differences from corresponding controls are indicated (“*” p < 0.05 and “**” p < 0.01; Mann–Whitney U test).

The bath application of gabazine would eliminate total GABAAR function in hippocampal networks. Therefore, to test the effects of postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition specifically on the recorded cells, we applied the method of depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI, Lenz and Alger, 1999) by clamping the recorded cell at 0 mV using the Cs+-based internal solution. Since stimulation at the stratum oriens/alveus has been used to demonstrate DSI (Lenz and Alger, 1999), we examined the effects of DSI on IPSCs evoked by stimuli at the stratum radiatum. Application of a 2–3 s depolarization (from −70 to 0 mV) to the recorded postsynaptic CA1 pyramidal cell induced DSI (43 ± 6% of the control, n = 5) for about 2 min (Figure 3B), similarly as previously reported (Lenz and Alger, 1999). In this particular experiment, we applied ca. two to three fold stronger stimuli (amplitude, 20–40 μA; duration, 300 μs) to evoke monosynaptic IPSCs of ca. 70 pA. When the DSI procedure was applied 5–10 s before the application of the spike-timing protocol at the θ frequency, induction of e-LTD within the time interval of −24 to −22 ms (–LTD) was eliminated (Figure 3C). In contrast, when the DSI procedure was applied 3 min before the same spike-timing protocol, by which time FF-IPSCs should have recovered to normal levels from the DSI (Figure 3B), the induction of e-LTD was successfully restored to control levels (Figure 3C). The postsynaptic Ca2+ increase caused by the DSI procedure, which is known to last for only a few seconds (Isokawa and Alger, 2006), is unlikely to have overlapped with that subsequently induced by the spike-timing protocol (applied 5–10 s later).

The effects of DSI on e-STDP induced at various time intervals (from −92 to +94 ms) were also examined. As shown in Figure 3D, the DSI did not affect significantly the magnitude of e-LTP induced by the LTP-timing protocol (time interval at +5 ms). In contrast, DSI not only eliminated e-LTD induction at both the –LTD and +LTD time intervals, but induced the most robust e-LTP at the original +LTD time intervals (Figure 3D). This might be due to the induction of higher NMDA receptor-mediated currents that coincided with postsynaptic spikes (Vargas-Caballero and Robinson, 2004). Moreover, reduction of postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition to approximately one half by the DSI resulted in two effects on the STDP time window for e-LTP induction: First, the original window of −2 to +15 ms was expanded to −15 to +20 ms, and second, additional LTP time windows appeared at −100 to −55 ms and at +45 to +100 ms (Figure 3D). This temporal feature of e-LTP induction may be consistent with the idea that DSI biases the STDP learning rule toward LTP. In the presence of DSI, we observed two distinct time windows (−55 to −15 ms and +20 to +45 ms) in which no e-LTP could be induced. The absence of e-LTP at −55 to −15 ms may have been due to the overlapping slow component of spike afterhyperpolarization, which was sensitive to blockade of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (unpublished data). The current study, however, cannot explain the absence of e-LTP (and slight e-LTD) at the intervals of +20 to +45 ms. Taken together, these results demonstrate the essential role of postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition as a critical determinant for the timing dependence of the e-STDP induction protocol at the θ frequency.

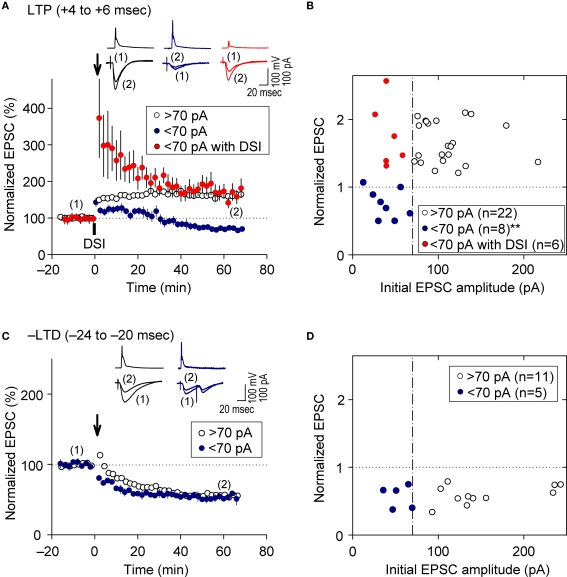

Feedback postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition causes e-LTD to enforce cooperative e-LTP

As demonstrated above, prominent FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition was induced by 5-Hz postsynaptic spiking (Figure 1E), whereas FF postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition was diminished as the intensity of presynaptic stimulation at SC inputs was reduced to a level that induced EPSCs of amplitudes <70 pA (red line in Figure 1D inset). We, therefore, examined the effect of FB inhibition on e-STDP in the absence of functional FF inhibition by stimulating a smaller population of SC inputs that evoked small EPSCs (<70 pA), using the Cs+-based recording solution. Unexpectedly, we found that the LTP-timing protocol (spiking intervals of +4 to +6 ms) induced e-LTD instead of e-LTP (Figures 4A,B), consistent with the requirement of cooperativity among multiple, coincident inputs for the induction of e-LTP (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993). Moreover, when FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition was suppressed by DSI, this e-LTD became a robust e-LTP, similar to that induced at inputs of amplitudes >70 pA (Figures 4A,B). Associative e-LTP can be induced at a single SC input to CA1 pyramidal cells by the pairing protocol (postsynaptic depolarization to 0 mV with presynaptic stimuli of 200 pulses at 1 Hz) in the absence of GABAAR-mediated inhibition (Petersen et al., 1998). These results, therefore, suggest that FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition not only prevents e-LTP induction at LTP time intervals (i.e., enforcing the requirement of cooperativity), but also causes the induction of e-LTD (i.e., gating for the induction of e-LTD). Similar e-LTD induction with the LTP-timing protocol has been reported in layer V cortical neurons at inputs from layer II/III neurons with stimuli at 50 Hz (Sjöström and Häusser, 2006). This e-LTD induction by a high-frequency (>50 Hz) protocol may be attributable to the difference of the threshold frequency of the spiking required to evoke FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition in these cortical neurons (Silberberg and Markram, 2007). Thus, this gating function of e-LTD by FB inhibition may be a universal rule for e-STDP. In contrast, e-LTD induction at the negative time intervals (–LTD) did not show this cooperative requirement (Figures 4C,D). An EPSC amplitude of 70 pA normally represents the co-activation of 10–20 synapses, as estimated from the average mini-EPSC amplitude of 3–5 pA (Kato et al., 1994), which may be capable of generating local dendritic Ca2+ spikes (Schiller et al., 2000). Therefore, intricate dendritic processing (e.g., integration or competition) of information according to the learning rule based on local spiking and that based on the back-propagating action potential (Jarsky et al., 2005; Rumsey and Abbott, 2006) may occur during the spike-timing protocol at the θ frequency.

Figure 4.

Feedback postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition causes e-LTD that enforces the requirement of cooperative e-LTP. (A,B) e-LTD is induced by the LTP-timing protocol when the initial EPSC amplitudes are <70 pA. DSI converts this e-LTD to e-LTP to the same extent as that induced normally at EPSC inputs of amplitude > 70 pA. (C,D) e-LTD is induced to a similar extent independent of the initial EPSC amplitudes. Significant difference from corresponding controls is indicated (“**” p < 0.01; Mann–Whitney U test).

Parallel induction of e-LTP/i-LTP and e-LTD/i-LTD occurs at θ frequency stimulation

It is widely accepted that during the induction of e-LTP at SC-CA1 inputs by tetanic stimulation, inhibitory inputs undergo LTD (i-LTD, McMahon and Kauer, 1997; Chevaleyre and Castillo, 2003; Gibson et al., 2008), which is mediated by endocannabinoid signaling (Chevaleyre and Castillo, 2003). Conversely, repetitive presynaptic stimulation, even at relatively low frequency (10 Hz), induces endocannabinoid-mediated i-LTD that facilitates e-LTP induction at neighboring synapses (Chevaleyre and Castillo, 2004). Furthermore, the DSI procedure facilitates LTP induction known as endocannabinoid-mediated disinhibition, which requires 50-Hz tetanic stimulation with small numbers of pulses at excitatory synapses (Carlson et al., 2002). We, therefore, examined i-STDP induction following application of the θ frequency spike-timing protocol at excitatory synapses. We concurrently measured EPSCs and FF-IPSCs from the same CA1 pyramidal cells at spiking time intervals for both LTP (+4 to +6 ms) and –LTD (−24 to −20 ms). Stimuli of the same intensity were applied to the same SC inputs to evoke both EPSCs and FF-IPSCs while 40-ms voltage-steps from −80 to +10 mV (the EPSC reversal potential) were applied to the recorded neurons to monitor FF-IPSCs. This allowed the stable recording of both EPSCs and FF-IPSCs for more than 90 min (Figure 5A). Surprisingly, we found that EPSCs and FF-IPSCs underwent parallel potentiation and depression of similar magnitudes following paired stimulation with spiking intervals that induced e-LTP (Figure 5B) and e-LTD (Figure 5C), although FF-IPSCs showed extensive short-term potentiation, regardless of the timing of the induction protocol. These results suggest that endocannabinoid-mediated i-LTD (Chevaleyre and Castillo, 2004) did not occur following the induction of e-LTP in our preparations (Figure 5B). Moreover, we found that DSI preceding the LTD-timing protocol abolished only e-LTD, not i-LTD (Figure 5D), demonstrating that the effects of the DSI were specific. Importantly, the magnitude of FF-IPSC immediately after the spike-timing protocol, regardless of the presence of DSI, was significantly greater than that of the basal FF-IPSC (indicated by red arrowheads, Figure 5B–D), suggesting the occurrence of prominent postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition during the spike-timing protocol at the θ frequency. This indicates that endocannabinoid-mediated disinhibition, i.e., passive modulation (Carlson et al., 2002), was also unlikely to have occurred. Thus, these results support the idea that postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition actively controls the timing dependence of e-LTD at the θ frequency.

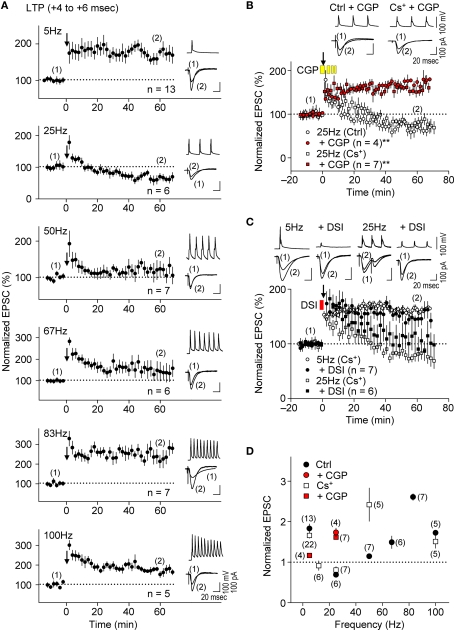

Presynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition causes frequency-dependent e-LTD

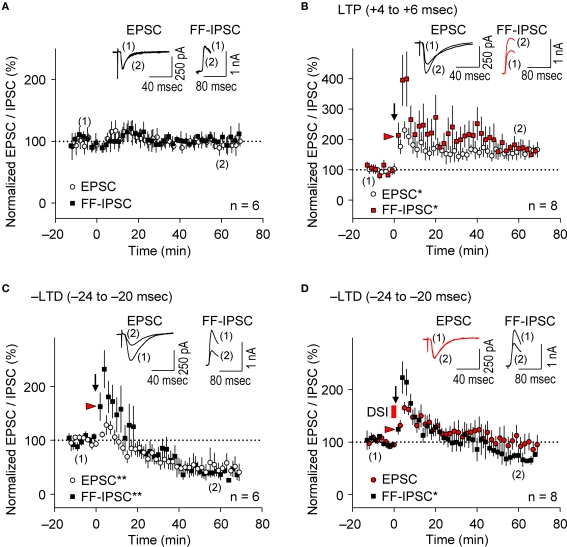

Presynaptic glutamate release, which determines the EPSC amplitude, would be reduced if the frequency of presynaptic spiking were to increase (Ohliger-Frerking et al., 2003) as a result of activation of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) at presynaptic terminals (Wu and Saggau, 1997). Because GABABRs are the major GPCRs at glutamatergic presynaptic terminals (Wu and Saggau, 1997), we tested whether presynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition could also cause e-LTD as the frequency of the spike-timing protocol increased. Application of the LTP-timing protocol (time intervals at the +4 to +6 ms), which normally induced e-LTP at the θ frequency (Figure 6A, top), had no significant effect on synaptic efficacy at 12 Hz (α frequency, for 6.7 s; 91.4 ± 10.6%, n = 6, in the Cs+-based internal solution; see Figure 6D). A further increase in the frequency of paired stimulation to 25 Hz (β frequency) resulted in e-LTD, not e-LTP, in both K+- and Cs+-based solutions. Furthermore, the most robust e-LTP was observed (substantially greater than that induced by the LTP-timing protocol at 5 and 100 Hz) when the frequency of the LTP-timing protocol reached the γ frequency (50–80 Hz) in both the K+- and Cs+-based internal solutions. However, the optimal frequency for induction of the maximal e-LTP in the Cs+-based internal solution (50 Hz) appears to be lower than that in the K+-based internal solution (83 Hz). This may have resulted from the slower kinetics of EPSPs in the Cs+-based internal solution, which allows overlap with the preceding EPSPs to cause a postsynaptic depolarization, even at a lower frequency. It is noteworthy that during LTP induction at the γ frequency the postsynaptic GABAAR function should be excitatory (Staley et al., 1995; Taira et al., 1997; Bracci et al., 2001), thereby likely enhancing the magnitude of e-LTP. These results support the idea that the induction of e-LTD also depends on the frequency of the spike-timing protocol, which is independent of postsynaptic K+ channel function.

Figure 6.

Presynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition causes frequency-dependent e-LTD at α/β frequencies. (A,D) Summary of frequency-dependent changes in synaptic efficacy induced by the spike-timing protocol for LTP-timing (+4 to +6 ms). Frequency-dependent effects (between 5 Hz and 100 Hz) in either the K+- or Cs+-based internal recording solution. Frequency-dependent e-LTD is induced at the same magnitude at 25 Hz and e-LTP is robust at the γ frequency in both recording solutions. (B) Bath application of CGP 35348 (1 mM, yellow bars) abolished e-LTD at 25 Hz, and instead induced e-LTP in both K+- and the Cs+-based internal recording solutions. (C) DSI failed to restore e-LTP induction at 25 Hz and had no significant effect on e-LTP at 5 Hz. Data represent normalized mean EPSCs (±sem). Membrane potentials during the spike-timing protocol (upper traces) and EPSCs (lower traces) before (1) and after (2) the induction protocols (in A–C). Scales: 100 pA (or 100 mV), 20 ms. Significant differences from corresponding controls are indicated (“**” p < 0.01; Mann–Whitney U test).

We examined further the effect of presynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition on the frequency-dependent induction of e-LTD by applying the GABABR antagonist CGP35348 (1 mM, Davies and Collingridge, 1996) in the bath during the spike-timing protocol. This treatment abolished e-LTD induction at 25 Hz and resulted in a substantial e-LTP instead, in both K+- and Cs+-based solutions (Figures 6B,D), suggesting that GABABR function is required for the induction of this frequency-dependent e-LTD. Interestingly, CGP35348 suppressed e-LTP induction at 5 Hz, the frequency at which presynaptic GABABR is most prominent at inhibitory inputs (Figure 6D, Davies and Collingridge, 1993), suggesting that postsynaptic GABAAR function is enhanced as a consequence of this treatment. Bath application of phaclofen, another GABABR antagonist, at the concentration (100 μM) that blocks presynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition at excitatory (Hasselmo and Fehlau, 2001) but not at inhibitory (Davies and Collingridge, 1993) inputs during the spike-timing protocol, similarly converted the e-LTD to robust e-LTP at 25 Hz (178.0 ± 17.4%, n = 4). Thus, presynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition at excitatory synapses is likely responsible for the frequency-dependent expression of e-LTD. Consistent with the idea that presynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition, but not postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition, may be a major inducer of frequency-dependent e-LTD, DSI affected e-LTD at 25 Hz only partially, while it had no significant effect on e-LTP induction at 5 Hz (Figure 6C). This partial effect could be due to a reduction of GABA release by DSI (Lenz and Alger, 1999), which would also reduce presynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition. Taken together, these results suggest that presynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition controls the frequency dependence of e-LTD at α/β frequencies and accounts for the expression of e-LTP at θ and γ frequencies.

Discussion

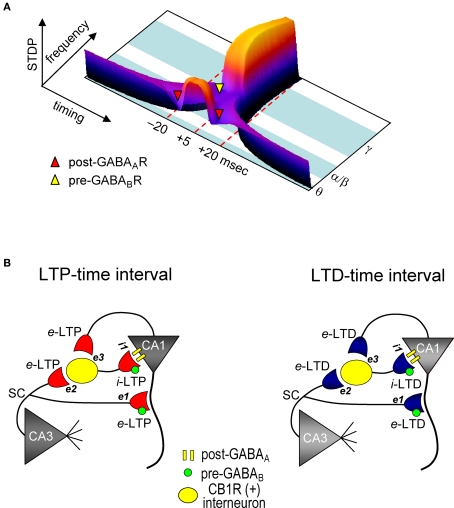

We demonstrated that GABAergic interneuronal network activities control the spike timing- and frequency-dependent induction of the e-LTD (at –LTD and +LTD time intervals) that delineates the expression of e-LTP in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells (see Figure 7A). The timing dependence of e-LTD induced by the θ frequency spike-timing protocol is regulated by both FF and FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition. Feedback postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition enforces the cooperative induction of e-LTP by causing e-LTD from a small population of the SC inputs during the LTP-timing. In contrast, the frequency-dependent expression of e-LTD at α/β frequencies is regulated predominantly by presynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition. This e-LTD then segregates the expression of e-LTP into θ (timing-dependent) and γ (timing-independent) frequencies. The induction of similar magnitudes of e- and i-STDP in hippocampal SC-CA1 networks further demonstrates a novel mechanism by which GABAergic inhibition actively causes the induction of e-LTD.

Figure 7.

Model for STDP controlled by GABA functions in the CA1 network. (A) Both spike timing- and frequency-dependence of e-STDP and differential GABA function that gates e-LTD. (B) Parallel induction of e-LTP/i-LTP and e-LTD/i-LTD. Upon application of the LTP- (left) or LTD-timing (right) protocol at 5 Hz, all excitatory synapses undergo, respectively, either e-LTP or e-LTD. e-LTP or e-LTD in the CB1R-expressing interneuron (both at inputs e2 and e3) propagates passively to input i-1, respectively, as either i-LTP or i-LTD.

Previously, the timing dependence of e-STDP was extensively studied using a low-frequency (<2 Hz) spike-timing induction protocol in various systems (Bi and Poo, 1998; Debanne et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 1998; Feldman, 2000; Froemke and Dan, 2002; Nevian and Sakmann, 2006). These studies led to the formulation of the asymmetric STDP learning rule: pre-before-post (causal order) results in e-LTP and post-before-pre (anti-causal order) results in e-LTD at the negative time intervals. The asymmetric STDP learning rule, which is compatible with Hebbian synaptic plasticity (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993) has been applied to explain bidirectional neuronal functions. In contrast, stimulation at the θ frequency (5 Hz), as in our previous (Nishiyama et al., 2000) and current studies and those of others (Wittenberg and Wang, 2006), results in the induction of a second e-LTD time window at positive time intervals. Also, a low-frequency (<2 Hz) spike-timing protocol induces a relatively broad e-LTD time window (>50 ms) at negative time intervals, whereas θ frequency induction of the STDP protocol induces relatively narrow e-LTD time windows (∼20 ms) at both –LTD and +LTD. Although the mechanisms of the appearance of narrow windows and an additional +LTD stimulated by the θ frequency are not understood, we found that while –LTD is fully sensitive to postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition, +LTD is only partially sensitive (Wittenberg and Wang, 2006), suggesting the involvement of unidentified mechanisms other than postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition and mechanisms related to spike afterhyperpolarization that suppress postsynaptic Ca2+ increase. Interestingly, computational analyses predict the stable presence of +LTD if the number of postsynaptic NMDARs increases (Shouval and Kalantzis, 2005). In support of this idea, recent electron microscopy study using the freeze-fracture replica method (Shinohara et al., 2008) demonstrated a much greater number of NMDARs at the spines of CA1 pyramidal cells compared to that reported previously (Racca et al., 2000). The greater number of NMDARs may be attributable to the persistent presence of +LTD induced by the θ frequency spike-timing protocol. Alternatively, it is also plausible that in addition to the different frequency dependency of FB IPSC recruitment in cortical neurons (Silberberg and Markram, 2007), cortical neurons may be innately endowed with an asymmetric, not a symmetric, STDP learning rule by these low-frequency stimuli.

In the current study, we applied DSI to investigate the timing dependence of e-STDP. Surprisingly, the DSI procedure caused drastic effects on the induction of e-STDP, even though a relatively minor population of interneurons (Glickfeld and Scanziani, 2006) are expected to be sensitive to it. Endocannabinoid receptor CB1R-expressing basket cells apparently receive inputs from both CA3 (the SC) and CA1 (the recurrent) pyramidal cells (Glickfeld and Scanziani, 2006). Therefore, these CB1R-expressing interneurons are highly likely to be involved in the determination of the timing dependence and the requirement for cooperative e-STDP by inducing both FF and FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition to the CA1 pyramidal cells during the spike-timing protocol. It has been demonstrated that burst postsynaptic spiking is required for e-LTP induction by θ frequency stimuli at SC-CA1 synapses (Thomas et al., 1998; Pike et al., 1999; Meredith et al., 2003; Wittenberg and Wang, 2006). In this case, the burst spiking, which is known to silence A-type K+ channel activity in distal dendrites (Hoffman et al., 1997), likely facilitates the back-propagation of action potentials during the induction protocol. In our protocol, however, repetitive single (no burst) postsynaptic spiking is sufficient to induce e-LTP (Nishiyama et al., 2000), suggesting that the activated synapses are distant from functional A-type channels (Hoffman et al., 1997). We also found that the magnitudes of FF postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition in thin slices (300–400 μm) were significantly smaller than in thick (500 μm) slices. Moreover, we observed FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition during θ frequency postsynaptic spiking, which is unlikely to occur during the application of a low-frequency (<2 Hz) spike-timing protocol (Silberberg and Markram, 2007). Therefore, the molecular mechanisms underlying the induction of e-LTD through postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition stimulated at the θ frequency likely differ from those of low-frequency stimulation-induced STDP (Bi and Poo, 1998; Feldman, 2000; Normann et al., 2000; Froemke and Dan, 2002). In support of this idea, the activity of mGluRs, rather than VDCCs, is required for e-LTD induction in our preparations (Nishiyama et al., 2000). We also compared the postsynaptic spike wave forms during the LTP-timing protocol in a Cs+-based internal solution with those in a K+-base internal solution and found a broadened spike width in the Cs+-based internal solution. However, it appears that postsynaptic spikes broadened by Cs+ do not contribute significantly to the features of e-STDP. This may also be consistent with the idea that Ca2+ entry through VDCCs is not essential for the induction of e-LTP (Bi and Poo, 1998) and e-LTD (Nishiyama et al., 2000). Our experimental paradigm is, thus, a unique procedure for the investigation of GABAergic activities during STDP. It has been shown that local dendritic spikes, without back-propagating action potentials, cause the induction of e-LTP (Golding et al., 2002). This type of synaptic plasticity is prominent at synaptic inputs of distal dendrites, where A-type channels prohibit invasion of single back-propagating action potentials (Hoffman et al., 1997). Our study, however, reveals the existence of bidirectional synaptic plasticity at proximal synaptic inputs that relies on the timing of single back-propagating action potentials. Depending on the location (i.e., proximal or distal dendrites) of activated synapses, different types of induction mechanisms, therefore, may be required to determine bidirectional synaptic plasticity.

Using weak SC input stimuli, we demonstrated that FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition enforces the cooperative requirement for LTP induction (i.e., EPSC amplitude of >70 pA). However, we cannot exclude the following possibilities: The DSI procedure may diminish the postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated actions by one half, including tonic inhibition (Mody and Pearce, 2004). Thus, the actual EPSC amplitude during the LTP-timing protocol (i.e., EPSP amplitude) may become greater than 70 pA as a result of the diminished shunting effect. Since, in our preparation, the EPSP amplitude is below 1 mV when the EPSC amplitude is smaller than 70 pA, it is not possible to accurately assess changes in EPSP amplitudes during the spike-timing protocol if they increased above the amplitude equivalent to EPSCs of 70 pA. We did not observe noticeable differences in the EPSP amplitudes in the presence of DSI compared to the control (data not shown). Moreover, the DSI permits induction of robust LTP, even at inputs with initial EPSC amplitudes of less than 40 pA (see Figure 4B). Therefore, DSI is unlikely to have caused increases of the actual EPSP during the spike-timing protocol. We demonstrated the absence of functional FF-IPSCs when the EPSC amplitude was less than 70 pA with the use of single stimuli at SC inputs. However, in response to sequential stimuli, such as during the spike-timing protocol, FF-IPSCs may become manifest due to sequential pulse facilitation, particularly in interneurons that receive both SC and recurrent inputs. Even if a potential contamination from FF-IPSCs occurs, it is likely negligible compared to the prominent FB-IPSCs (an IPSP amplitude of ca. −34 mV, which is equivalent to an IPSC amplitude of ca. 800 to 900 pA). Therefore, our conclusion that FB postsynaptic GABAAR-mediated inhibition enforces the cooperative requirement for LTP induction would not be affected significantly.

We showed that FF-IPSCs undergo i-LTP and i-LTD, which are associated, respectively, with e-LTP and e-LTD induced by the θ frequency spike-timing protocol at SC-CA1 excitatory synapses. Two distinct mechanisms, passive and active induction, that cause synaptic efficacy changes in excitatory inputs to interneurons have been demonstrated. Both e-LTP and e-LTD propagate passively to FB interneurons (Maccaferri and McBain, 1995, 1996). Interneurons also express e-LTP directly (Kullmann and Lamsa, 2007) at the SC input (Lamsa et al., 2005) and at the input from CA1 pyramidal cells (Lamsa et al., 2007). Interestingly, e-LTP at the SC-FF interneuron synapses propagates to the inhibitory input to CA1 pyramidal cells (Lamsa et al., 2005). The parallel induction of e-LTP/i-LTP and e-LTD/i-LTD that we observed may, therefore, depend on both the passive and active mechanisms of induction of inhibitory synaptic plasticity (Figure 7B). Since CB1R-expressing basket cells (Glickfeld and Scanziani, 2006) receive inputs from both CA3 and from the recorded CA1 pyramidal cells, the magnitudes of which are each sufficient to spike these interneurons, both e-LTP and e-LTD can be induced. These excitatory inputs to interneurons may follow a similar STDP learning rule for excitatory inputs to recorded CA1 pyramidal cells. During the LTP-timing protocol, the disynaptic inputs from CA3 and CA1 should be the LTP-timing for one another (i.e., time intervals of ∼0 ms). Conversely, during the LTD-timing protocol, these inputs become either the +LTD or –LTD time intervals for one another, because the time difference between two inputs to an interneuron is approximately 20 ms, which is the LTD time interval. Therefore, upon application of the spike-timing protocol, excitatory inputs to both CA1 recording cells and interneurons undergo e-STDP with the same polarity. Then, either e-LTP or e-LTD in interneurons propagates passively to inputs to CA1 recording cells to become, respectively, either i-LTP or i-LTD. Thus, the parallel induction of e- and i-LTP may help to maintain the temporal resolution of excitatory synaptic integration and the generation of an action potential in excitatory LTP-expressing CA1 pyramidal cells (Pouille and Scanziani, 2001; Lamsa et al., 2005).

We also showed that the frequency dependence of e-LTD at α/β frequencies, which likely delineates the expression of e-LTP at the θ and γ frequencies, requires presynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition. This is consistent with the optimal frequencies required for induction of presynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition, which are maximal at the θ and above the α/β frequencies for inhibitory and excitatory presynaptic terminals, respectively (Davies and Collingridge, 1996; Ohliger-Frerking et al., 2003). In addition to the appearance of e-LTD at α/β frequencies, we observed that the magnitude of e-LTP begins to decrease if the frequency of the spike-timing protocol increases above the γ frequency (i.e., at 100 Hz). Although the molecular mechanisms underlying the reduction of e-LTP at a high frequency requires further investigation, its non-linearity apparently violates Ca2+ theory for synaptic plasticity. Despite this, our study demonstrates that e-STDP in CA1 pyramidal cells is likely self-limited by the neural network function. It has been reported that postsynaptic GABABRs inactivate VDCCs independent of GIRK activity (Perez-Garci et al., 2006). However, since e-LTD at the θ frequency appears to be independent of VDCC activity (Nishiyama et al., 2000), postsynaptic GABABRs may not be involved in e-LTD induction. The potential contribution of postsynaptic GABABR-mediated inhibition to frequency-dependent e-LTD at the α/β frequencies requires further investigation.

Taken together, our study demonstrates the mechanism by which GABAergic inhibitory activities cause e-LTD at time intervals of ±20 ms (at the θ frequency) or at α/β frequencies to control the timing- and frequency-dependent features of e-STDP; e-LTP/e-LTD switches within the γ cycle (Nishiyama et al., 2000) and e-LTP appears at the θ and γ frequencies. Therefore, the GABAergic interneuronal network activities that regulate STDP may similarly govern hippocampal oscillations in vivo (Buzsáki, 2002; Csicsvari et al., 2003; Lisman et al., 2005). Interestingly, the parallel induction of STDP demonstrated in this study, in which e-LTP likely depolarizes dendrites when i-LTP hyperpolarizes the soma, is consistent with the in vivo hippocampal θ oscillation that yields a phase-shift, a current sink at the dendrite and a current source at the soma resulting from GABAergic and cholinergic activities (Kamondi et al., 1998; Buzsáki, 2002). Future studies will determine whether the underlying mechanisms of GABAergic interneuronal network activities that govern STDP also apply to θ and γ oscillations.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the CRCNS program NSF/NIH (MH068027), the Whitehall Foundation Inc. and the Brain Science Foundation. We thank Drs. M. M. Poo, D. Debanne, H. Eichenbaum, B. H. Gaehwiler, J. E. Lisman, N. Spruston and H. Sei for discussion and comments; W. Jelinek and N. Cowen for critical comments on the manuscript; K. Kato for technical support.

References

- Bartos M., Vida I., Jonas P. (2007). Synaptic mechanisms of synchronized gamma oscillations in inhibitory interneuron networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 45–56 10.1038/nrn2044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi G.-q., Poo M.-m. (1998). Synaptic modifications in cultured hippocampal neurons: dependence on spike timing, synaptic strength, and postsynaptic cell type. J. Neurosci. 18, 10464–10472 10.1016/S0031-9384(02)00933-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss T. V., Collingridge G. L. (1993). A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature 361, 31–39 10.1038/361031a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracci E., Vreugdenhil M., Hack S. P., Jefferys J. G. R. (2001). Dynamic modulation of excitation and inhibition during stimulation at gamma and beta frequencies in the CA1 hippocampal region. J. Neurophysiol. 85, 2412–2422 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00212-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G. (2002). Theta oscillations in the hippocampus. Neuron 33, 325–340 10.1002/hipo.20113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G., Penttonen M., Nádasdy Z., Bragin A. (1996). Pattern and inhibition-dependent invasion of pyramidal cell dendrites by fast spikes in the hippocampus in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 9921–9925 10.1002/hipo.450050210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporale N., Dan Y. (2008). Spike timing-dependent plasticity: a Hebbian learning rule. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 31, 25–46 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardin J. A., Carlén M., Meletis K., Knoblich U., Zhang F., Deisseroth K., Tsai L. H., Moore C. I. (2008). Driving fast-spiking cells induces gamma rhythm and controls sensory responses. Nature 459, 663–667 10.1038/nature08002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson G., Wang Y., Alger B. (2002). Endocannabinoids facilitate the induction of LTP in the hippocampus. Nat. Neurosci. 5, 723–724 10.1038/nn879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V., Castillo P. (2003). Heterosynaptic LTD of hippocampal GABAergic synapses: a novel role of endocannabinoids in regulating excitability. Neuron 38, 461–472 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00235-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V., Castillo P. (2004). Endocannabinoid-mediated metaplasticity in the hippocampus. Neuron 43, 871–881 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors B. W., Malenka R. C., Silva L. R. (1988). Two inhibitory postsynaptic potentials, and GABAA and GABAB receptor-mediated responses in neocortex of rat and cat. J. Physiol. 406, 443–468 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)63621-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csicsvari J., Jamieson B., Wise K., Buzsáki G. (2003). Mechanisms of gamma oscillations in the hippocampus of the behaving rat. Neuron 37, 311–322 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01169-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan Y., Poo M.-M. (2006). Spike timing-dependent plasticity: from synapse to perception. Physiol. Rev. 86, 1033–1048 10.1152/physrev.00030.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies C. H., Collingridge G. L. (1993). The physiological regulation of synaptic inhibition by GABAB autoreceptors in rat hippocampus. J. Physiol. 472, 245–265 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90073-C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies C. H., Collingridge G. L. (1996). Regulation of EPSPs by the synaptic activation of GABAB autoreceptors in rat hippocampus. J. Physiol. 496, 451–470 10.1038/349609a0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D., Gahwiler B. H., Thompson S. M. (1998). Long-term synaptic plasticity between pairs of individual CA3 pyramidal cells in rat hippocampal slice cultures. J. Physiol. 507, 237–247 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.237bu.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman D. (2000). Timing-based LTP and LTD at vertical inputs to layer II/III pyramidal cells in rat barrel cortex. Neuron 27, 45–56 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00008-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froemke R., Dan Y. (2002). Spike-timing-dependent synaptic modification induced by natural spike trains. Nature 416, 433–438 10.1038/416433a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson H. E., Edwards J. G., Page R. S., Van Hook M. J., Kauer J. A. (2008). TRPV1 channels mediate long-term depression at synapses on hippocampal interneurons. Neuron 57, 746–759 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glickfeld L. L., Scanziani M. (2006). Distinct timing in the activity of cannabinoid-sensitive and cannabinoid-insensitive basket cells. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 807–815 10.1038/nn1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding N., Staff N., Spruston N. (2002). Dendritic spikes as a mechanism for cooperative long-term potentiation. Nature 418, 326–331 10.1038/nature00854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo M. E., Fehlau B. P. (2001). Differences in time course of ACh and GABA modulation of excitatory synaptic potentials in slices of rat hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol. 86, 1792–1802 10.1016/S0925-2312(01)00411-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman D., Magee J., Colbert C., Johnston D. (1997). K+ channel regulation of signal propagation in dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Nature 387, 869–875 10.1038/43119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isokawa M., Alger B. E. (2006). Ryanodine receptor regulates endogenous cannabinoid mobilization in the hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol. 95, 3001–3011 10.1152/jn.00975.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarsky T., Roxin A., Kath W. L., Spruston N. (2005). Conditional dendritic spike propagation following distal synaptic activation of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1667–1676 10.1038/nn1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamondi A., Acsady L., Wang X., Buzsáki G. (1998). Theta oscillations in somata and dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal cells in vivo: activity-dependent phase-precession of action potentials. Hippocampus 8, 244–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K., Clark G. D., Bazan N. G., Zorumski C. F. (1994). Platelet-activating factor as a potential retrograde messenger in CA1 hippocampal long-term potentiation. Nature 367, 175–179 10.1038/367175a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T., Somogyi P. (2008). Neuronal diversity and temporal dynamics: the unity of hippocampal circuit operations. Science 321, 53–57 10.1126/science.1149381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koester H. J., Sakmann B. (1998). Calcium dynamics in single spines during coincident pre- and postsynaptic activity depend on relative timing of back-propagating action potentials and subthreshold excitatory postsynaptic potentials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 9596–9601 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann D. M., Lamsa K. P. (2007). Long-term synaptic plasticity in hippocampal interneurons. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 687–699 10.1038/nrn2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamsa K., Heeroma J., Kullmann D. (2005). Hebbian LTP in feed-forward inhibitory interneurons and the temporal fidelity of input discrimination. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 916–924 10.1038/nn1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamsa K. P., Heeroma J. H., Somogyi P., Rusakov D. A., Kullmann D. M. (2007). Anti-Hebbian long-term potentiation in the hippocampal feedback inhibitory circuit. Science 315, 1262–1266 10.1126/science.1137450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz R. A., Alger B. (1999). Calcium dependence of depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition in rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J. Physiol. 521, 147–157 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00147.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman J., Talamini L., Raffone A. (2005). Recall of memory sequences by interaction of the dentate and CA3: a revised model of the phase precession. Neural. Netw. 18, 1191–1201 10.1016/j.neunet.2005.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G., David J., Roberts B., Szucs P., Cottingham C. A., Somogyi P. (2000). Cell surface domain specific postsynaptic currents evoked by identified GABAergic neurones in rat hippocampus in vitro. J. Physiol. 524, 91–116 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-3-00091.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G., McBain C. J. (1995). Passive propagation of LTD to stratum oriens-alveus inhibitory neurons modulates the temporoammonic input to the hippocampal CA1 region. Neuron 15, 137–145 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90071-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G., McBain C. J. (1996). Long-term potentiation in distinct subtypes of hippocampal nonpyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 16, 5334–5343 10.1097/00001756-199409080-00032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee J. C., Johnston D. (1997). A synaptically controlled, associative signal for Hebbian plasticity in hippocampal neurons. Science 275, 209–213 10.1126/science.275.5297.209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H., Lübke J., Frotscher M., Sakmann B. (1997). Regulation of synaptic efficacy by coincidence of postsynaptic APs and EPSPs. Science 275, 213–215 10.1126/science.275.5297.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon L. L., Kauer J. A. (1997). Hippocampal interneurons express a novel form of synaptic plasticity. Neuron 18, 295–305 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80269-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megias M., Emri Z., Freund T., Gulyas A. (2001). Total number and distribution of inhibitory and excitatory synapses on hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Neuroscience 102, 527–540 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00496-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith R. M., Floyer-Lea A. M., Paulsen O. (2003). Maturation of long-term potentiation induction rules in rodent hippocampus: role of GABAergic inhibition. J. Neurosci. 23, 11142–11146 10.1152/jn.00717.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody I., Pearce R. A. (2004). Diversity of inhibitory neurotransmission through GABAA receptors. Trends Neurosci. 27, 569–575 10.1016/j.tins.2004.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevian T., Sakmann B. (2006). Spine Ca2+ signaling in spike-timing-dependent plasticity. J. Neurosci. 26, 11001–11013 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1749-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama M., Hong K., Mikoshiba K., Poo M., Kato K. (2000). Calcium stores regulate the polarity and input specificity of synaptic modification. Nature 408, 584–588 10.1038/35046067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normann C., Peckys D., Schulze C. H., Walden J., Jonas P., Bischofberger J. (2000). Associative long-term depression in the hippocampus is dependent on postsynaptic N-type Ca2+ channels. J. Neurosci. 20, 8290–8297 10.1088/0957-4484/19/43/435301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohliger-Frerking P., Wiebe S. P., Stäubli U., Frerking M. (2003). GABAB receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition has history-dependent effects on synaptic transmission during physiologically relevant spike trains. J. Neurosci. 23, 4809–4814 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00360-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Garci E., Gassmann M., Bettler B., Larkum M. (2006). The GABAB1b isoform mediates long-lasting inhibition of dendritic Ca2+ spikes in layer 5 somatosensory pyramidal neurons. Neuron 50, 603–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen C. C., Malenka R. C., Nicoll R. A., Hopfield J. J. (1998). All-or-none potentiation at CA3-CA1 synapses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 4732–4737 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike F. G., Meredith R. M., Olding A. W., Paulsen O. (1999). Rapid report: postsynaptic bursting is essential for 'Hebbian' induction of associative long-term potentiation at excitatory synapses in rat hippocampus. J. Physiol. 518, 571–576 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0571p.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouille F., Scanziani M. (2001). Enforcement of temporal fidelity in pyramidal cells by somatic feed-forward Inhibition. Science 293, 1159–1163 10.1126/science.1060342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouille F., Scanziani M. (2004). Routing of spike series by dynamic circuits in the hippocampus. Nature 429, 717–723 10.1038/nature02615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racca C., Stephenson F. A., Streit P., Roberts J. D., Somogyi P. (2000). NMDA receptor content of synapses in stratum radiatum of the hippocampal CA1 area. J. Neurosci. 20, 2512–2522 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01303.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumsey C. C., Abbott L. F. (2006). Synaptic democracy in active dendrites. J. Neurophysiol. 96, 2307–2318 10.1152/jn.00149.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller J., Major G., Koester H. J., Schiller Y. (2000). NMDA spikes in basal dendrites of cortical pyramidal neurons. Nature 404, 285–289 10.1038/35005094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller J., Schiller Y., Clapham D. (1998). NMDA receptors amplify calcium influx into dendritic spines during associative pre- and postsynaptic activation. Nat. Neurosci. 1, 114–118 10.1038/363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara Y., Hirase H., Watanabe M., Itakura M., Takahashi M., Shigemoto R. (2008). Left-right asymmetry of the hippocampal synapses with differential subunit allocation of glutamate receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 19498–19503 10.1073/pnas.0807461105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shouval H. Z., Kalantzis G. (2005). Stochastic properties of synaptic transmission affect the shape of spike time-dependent plasticity curves. J. Neurophysiol. 93, 1069–1073 10.1152/jn.00504.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg G., Markram H. (2007). Disynaptic inhibition between neocortical pyramidal cells mediated by Martinotti cells. Neuron 53, 735–746 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström P., Nelson S. (2002). Spike timing, calcium signals and synaptic plasticity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 12, 305–314 10.1016/S0959-4388(02)00325-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström P., Turrigiano G., Nelson S. (2001). Rate, timing, and cooperativity jointly determine cortical synaptic plasticity. Neuron 32, 1149–1164 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00542-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström P. J., Häusser M. (2006). A cooperative switch determines the sign of synaptic plasticity in distal dendrites of neocortical pyramidal neurons. Neuron 51, 227–238 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohal V. S., Zhang F., Yizhar O., Deisseroth K. (2008). Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance. Nature 459, 698–702 10.1038/nature07991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley K., Soldo B., Proctor W. (1995). Ionic mechanisms of neuronal excitation by inhibitory GABAA receptors. Science 269, 977–981 10.1126/science.7638623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart G., Häusser M. (2001). Dendritic coincidence detection of EPSPs and action potentials. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 63–71 10.1038/82910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taira T., Lamsa K., Kaila K. (1997). Posttetanic excitation mediated by GABAA receptors in rat CA1 pyramidal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 77, 2213–2218 10.1097/00001756-199201000-00028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M. J., Watabe A. M., Moody T. D., Makhinson M., O'Dell T. J. (1998). Postsynaptic complex spike bursting enables the induction of LTP by theta frequency synaptic stimulation. J. Neurosci. 18, 7118–7126 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80179-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubokawa H., Ross W. N. (1996). IPSPs modulate spike backpropagation and associated [Ca2+]i changes in the dendrites of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 76, 2896–2906 10.1016/S0168-0102(97)81682-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rossum M. C., Bi G. Q., Turrigiano G. G. (2000). Stable Hebbian learning from spike timing-dependent plasticity. J. Neurosci. 20, 8812–8821 10.1016/S0925-2312(01)00360-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Caballero M., Robinson H. P. (2004). Fast and slow voltage-dependent dynamics of magnesium block in the NMDA receptor: the asymmetric trapping block model. J. Neurosci. 24, 6171–6180 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1380-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington M., Traub R., Jefferys J. (1995). Synchronized oscillations in interneuron networks driven by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation. Nature 373, 612–615 10.1038/373612a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg G. M., Wang S. S.-H. (2006). Malleability of spike-timing-dependent plasticity at the CA3-CA1 synapse. J. Neurosci. 26, 6610–6617 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5388-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodin M., Ganguly K., Poo M. (2003). Coincident pre- and postsynaptic activity modifies GABAergic synapses by postsynaptic changes in Cl- transporter activity. Neuron 39, 807–820 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00507-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L., Saggau P. (1997). Presynaptic inhibition of elicited neurotransmitter release. Trends Neurosci. 20, 204–212 10.1016/S0166-2236(96)01015-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Tao H., Holt C., Harris W., Poo M. (1998). A critical window for cooperation and competition among developing retinotectal synapses. Nature 395, 37–44 10.1038/25665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]