Abstract

Purpose

BRCA1/2 test disclosure has, historically, been conducted in-person by genetics professionals. Given increasing demand for, and access to, genetic testing, interest in telephone and Internet genetic services, including disclosure of test results, has increased.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews with genetic counselors were conducted to determine interest in, and experiences with telephone disclosure of BRCA1/2 test results. Descriptive data are summarized with response proportions.

Results

194 genetic counselors completed self-administered surveys via the web. Although 98% had provided BRCA1/2 results by telephone, 77% had never provided pre-test counseling by telephone. Genetic counselors reported perceived advantages and disadvantages to telephone disclosure. Thirty-two percent of participants described experiences that made them question this practice. Genetic counselors more frequently reported discomfort with telephone disclosure of a positive result or variant of uncertain significance (p<0.01) than other results. Overall, 73% of participants reported interest in telephone disclosure.

Conclusion

Many genetic counselors have provided telephone disclosure, however, most, infrequently. Genetic counselors identify potential advantages and disadvantages to telephone disclosure, and recognize the potential for testing and patient factors to impact patient outcomes. Further research evaluating the impact of testing and patient factors on cognitive, affective, social and behavioral outcomes of alternative models of communicating genetic information is warranted.

Keywords: BRCA 1/2, communication, genetic counselors, genetic testing, telephone

INTRODUCTION

Genetic screening for disease susceptibility holds great promise for informing tailored risk reduction and prevention recommendations. This application of “personalized medicine” has become standard practice in cancer prevention, where genetic testing for cancer susceptibility for a variety of cancer sites has become routine for high-risk populations, particularly breast, ovarian and colon cancer1-4. Heightened consumer awareness of “cancer genes” and other disease susceptibility genomic testing has escalated interest in and demand for genetic risk assessment. Future demand for predictive genetic testing in prevention of cancer and other diseases is expected to surpass accessibility to genetic specialists 5,6. Thus, alternative, more efficient methods of service delivery have been proposed for the clinical translation of genetic information to “personalized medicine”.

Professional societies currently recommend that predictive genetic testing be paired with pre- and post-test counseling5,2 to optimize patients’ informed consent, understanding and processing of the implications of genetic test results 5,7. Given these recommendations, the complexity of genetic information, the potential for false reassurance, the potential for psychological distress (e.g. persistent anxiety and guilt about the development of cancer in themselves or offspring8-11), communication of predictive genetic information has traditionally been conducted in-person by health care professionals trained in clinical genetics8,12,13. With new genomic discoveries, population demand for genetic screening will necessitate considering new modes and methods for effective, efficient genetic risk communication. Historically, genetic counselors have incorporated telephone communication of teratogenic information and prenatal test results into counseling services 14-18, suggesting one model to extend genetic services in response to geographical or other constraints. Telephone communication of predictive genetic testing for cancer susceptibility has been reported19-27, but to our knowledge, has not been widely adopted. We designed this study to evaluate interest in, and experience with, telephone disclosure among genetic counselors to inform clinically relevant components of, and outcomes for, the future study of alternative models for communicating genetic information.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Genetic counselors with experience in clinical cancer genetics were recruited through the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) Cancer Special Interest Group (caSIG) listserv. Respondents were NSGC members who either had graduate training in genetic counseling or another related field, were board eligible or certified by the American Board of Genetic Counseling or the American Board of Medical Genetics and have provided genetic counseling for at least 3 years. Participants were excluded if they reported that less than 10% of their current clinical activities are dedicated specifically to genetic counseling and testing for hereditary cancer syndromes. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at the Fox Chase Cancer Center (FCCC) and an e-mail link to the survey was posted for a 3 week period (May 2008 – June 2008). Two reminder emails with the link were posted. All participants completed electronic informed consent.

Survey Instrument

A 34-item mixed-methods self-administered survey was developed by study investigators to evaluate genetic counselors use and frequency of telephone pre-test and post-test counseling for hereditary cancer syndromes, interest in telephone disclosure for BRCA1/2 testing and opinions of, and experiences with, telephone disclosure of BRCA1/2 test results. The combined methods survey included closed-ended items reported on Likert scales and open-ended response items. Genetic counselors reporting experience with telephone disclosure of genetic test results on closed items were asked additional questions about their experiences with, and opinions regarding, telephone disclosure.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were utilized to generate response proportions to close-ended items. Framework analysis was utilized to analyze open-ended responses28-33. Investigators intensively reviewed responses for a subsample (20%) of participants and developed a thematic framework of primary and secondary themes for each open-ended item34. Next, two investigators (AB, LPM) independently assigned thematic codes to the subsamples’ open-ended responses (inter-coder agreement 96-97%)35. The thematic framework was then applied to the remaining samples’ open-ended responses and refined to include new themes as they emerged. Differences in code assignments were resolved through inter-coder discussion, which established agreement for all responses. Closed-ended responses and coded responses for open-ended items were entered into a database for analysis using standard statistical software (STATA, Release 9.0; STATA Corp, College Station, TX).

We used symmetry tests36,37 to investigate whether the frequency of telephone communication differed for pre-test and post-test counseling (StataCorp, College Station, TX). A statistically significant symmetry test would suggest that genetic counselors differ in their rate of use of telephone of pre- and post-test counseling. We also used symmetry tests to investigate if genetic counselor comfort with providing test results over the phone differed depending on the patients’ test results. To investigate univariable relationships between genetic counselor characteristics and utilization of telephone disclosure, we used ordinal logistic regressions assuming proportional odds38. The ordinal outcome used in the model was a three category variable describing the frequency of utilization of telephone for disclosure of BRCA1/2 test results (<25%, 25-75%, >75%).

RESULTS

Participants

According to the NSGC, there were 775 members of the caSIG (NSGC, personal communication 3/13/2008) at the time the survey was posted. Five genetic counselors who participated in the development or piloting of the survey were excluded. Additionally, 11 who responded did not meet inclusion criteria, and an additional 17 eligible participants started but did not complete the survey. One-hundred ninety-four genetic counselors completed the survey, providing a response rate of 26%, assuming the remaining caSIG members would have met eligibility criteria. Participant demographics and practice characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Consistent with the field and the demographics of the NSGC membership in 2008, the majority of participating genetic counselors were women under 40 years old and spend the majority of their professional time in clinical counseling. Participants in our study were more likely to practice in an academic center and were less likely to have practiced for more than 10 years as compared respondents to the NSGC Professional Status Survey 2008 (available, www.nsgc.org).

Table 1.

Respondent demographics and practice characteristics (n=194)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 33 (25 −62 YO) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 183 (94) |

| Male | 11 (6) |

| Number of years providing clinical testing for hereditary cancer syndromes | |

| Less than 5 years | 83 (43) |

| 5-10 years | 79 (41) |

| more than 10 years | 32 (16) |

| Clinical setting | |

| Academic medical center | 101 (52) |

| Community/private hospital | 68 (35) |

| Other* | 25 (13) |

| # counseling sessions per week | |

| 0-5 | 53 (27) |

| 5-10 | 84 (43) |

| 10-15 | 45 (23) |

| >15 | 12 (6) |

| % time dedicated to: | Mean (SD) |

| clinical genetic counseling | 83.3 (20.7) |

| research | 13.2 (17.0) |

| other activities | 15.4 (20.0) |

Commercial laboratory, private company, private practice, government.

Frequency and incorporation of telephone communication in genetic counseling and testing

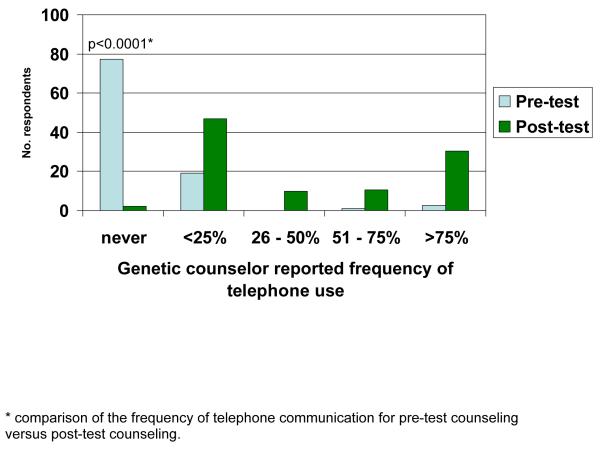

Seventy-seven percent of genetic counselors had never provided pre-test counseling by telephone (Figure 1). In contrast, 98% (190/194) of genetic counselors reported having provided BRCA1/2 genetic test results by telephone (p<0.01). Almost half of genetic counselors reported rarely (<25% of the time) sharing results by telephone, however 30% reported sharing results by telephone frequently (>75% of the time) (Figure 1). Genetic counselor characteristics, including age, gender, years in practice, graduation year, practice setting, percent of practice comprised of clinical activities, and number of genetic counseling sessions per week, did not predict frequency of telephone disclosure use by the ordinal logistic regression models (univariable and multivariable). In response to an open-ended question, genetic counselors provided a variety of circumstances in which they would consider providing BRCA1/2 genetic test results by telephone. Use of telephone communication of BRCA1/2 test results was reported most frequently to reduce patient burden or increase convenience (e.g. travel, illness, scheduling and financial, 52%), on the basis of patient preference (32%) or for specific test results (e.g. negative results, 32%). Additionally, 167 (86%) reported providing other genetic test results by telephone, including genetic test results for other hereditary cancer syndromes (n=91), prenatal test results (n=45), “non-cancer genetic test results” (n=19) and pediatric genetic tests (n=18).

FIGURE 1.

Frequency of telephone communication for pre-test and post-test counseling / N = 194

(p<0.0001)

Among those who have shared BRCA1/2 test results by telephone, 64% indicated that they do not modify their disclosure session procedures for telephone disclosure and 56% reported that they do not send written materials in advance to facilitate telephone disclosure. Genetic counselors reported contacting patients for telephone disclosure in a variety of settings, including home (86%), work (41%), on their cellular phones (22%), or any setting that the patient preferred (20%). The majority (62%) of genetic counselors who have used telephone disclosure reported contacting patients during normal business hours (8am-5pm). Forty-six percent of genetic counselors reported that patients never include other individuals in the phone disclosure. The majority (86%) of genetic counselors who conduct telephone disclosure report having never included a physician in that communication and 44% reported frequently encouraging patients to follow-up with them in-person.

Opinions and experiences regarding telephone disclosure

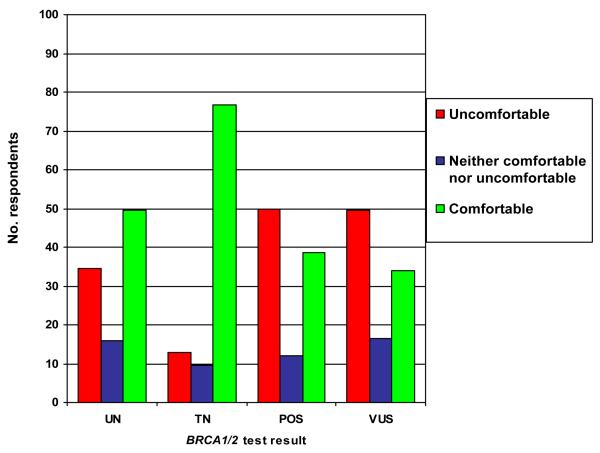

Genetic counselors reporting experience with telephone disclosure were asked in 4 individual questions how comfortable they are communicating by telephone each of the four possible testing outcomes: positive, true negative, uninformative negative results, and variants of uncertain significance. Genetic counselors more frequently reported being uncomfortable with telephone communication of a positive result or variant of uncertain significance (p<0.01, Figure 2). Comfort with telephone communication of the individual test results did not differ significantly by reported years in practice. Higher frequency of telephone disclosure use was associated with greater comfort with disclosure for each of the test results (p<=0.001).

FIGURE 2.

Genetic counselor comfort with providing BRCA1/2 test results by telephone according to patient test result / N = 190: UN = uninformative negative (negative BRCA1/2 result with no known mutation in the family), TN = true negative (negative BRCA1/2 result with a known mutation in the family), POS = positive (deleterious mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2), VUS = variant of uncertain significance in BRCA1 or BRCA2)

(p <0.0001 for all pairwise comparisons except for comparison of POS versus VUS in which p=0.12)

Genetic counselors were asked to share their opinions regarding potential advantages and disadvantages of telephone disclosure in two separate open-ended questions (Table 2). The most frequently reported perceived advantages were increased convenience for patients (n=122), medical benefit (n=70) of receiving results more quickly to inform medical management decisions, time for patients to process results and prepare questions for follow-up visits with health care providers, and psychological benefits (n=64, see Table 2). The most frequently reported disadvantages were potential challenges for genetic counselors in communicating and counseling by telephone (73%), and the potential for poorer understanding among patients due to omitted or misunderstood information (37%).

Table 2.

Perceived advantages and disadvantages of telephone communication of BRCA1/2 test results

| N | |

|---|---|

| PERCEIVED ADVANTAGES (N=184*) | |

| Advantages for PATIENTS | |

| Convenience | 122 |

| Less travel/transportation | 60 |

| More convenience (overall) | 49 |

| Less time | 37 |

| Medical benefits | 70 |

| Result available sooner for medical management decisions | 47 |

| Patient preparation time greater for follow-up appointment | 32 |

| Psychological benefits | 64 |

| More control | 26 |

| More satisfaction | 25 |

| Less anxiety | 13 |

| More privacy | 11 |

| Advantages for GENETIC COUNSELORS | |

| Time savings | 32 |

| Less time per patient | 13 |

| More patient capacity | 10 |

| Time saving (overall) | 6 |

| PERCEIVED DISADVANTAGES (N=180**) | |

| Disadvantages for PATIENTS | |

| Communication and understanding | 67 |

| Omitted information (abbreviated or disrupted call) | 39 |

| Misunderstood information | 25 |

| Patients unprepared for call | 8 |

| Psychological | 26 |

| Less emotional support from genetic counselor (18); family/friends (5) | 23 |

| More anxiety | 13 |

| Medical (Less compliance with f/u appointment) | 22 |

| Disadvantages for GENETIC COUNSELORS | |

| Communication | 132 |

| More difficult to counsel by telephone | 70 |

| More difficult to assess/respond to patient emotions | 50 |

| More difficult to assess/respond to patient understanding | 38 |

| More difficult to counsel without visual aids/written materials | 25 |

| More difficult to assess/respond to patient’s environment | 11 |

| Financial (inability to bill for services) | 24 |

| Time (reaching patient and/or additional follow-up phone calls) | 10 |

10 participants did not answer the item

14 participants did not answer the item.

In response to a yes/no question, many genetic counselors (32%) reported having telephone disclosure experiences that made them question the use of telephone disclosure as a practice. Descriptions of those experiences were elicited in open-ended follow-up query and are summarized in Table 3. Reporting negative experiences with telephone disclosure was not significantly related to reported frequency of telephone disclosure. When asked to rate, on a 5-point Likert scale, how interested they are in providing BRCA1/2 test results by telephone, seventy-three percent of genetic counselors reported being somewhat or very interested.

Table 3.

Experiences that have made respondents question utilization of telephone disclosure* (n=63)

| N | |

|---|---|

| PATIENT EVENTS | 32 |

| Poor communication and understanding * | 23 |

| Noncompliance with in-person follow-up visit | 20 |

| Misunderstood information | 16 |

| Omitted information (abbreviated or disrupted call) | 8 |

| Negative psychological outcomes * | 11 |

| Strong emotional response | 11 |

| Dissatisfaction | 3 |

| GENETIC COUNSELOR EVENTS | 24 |

| Difficulty assessing patient cognitive or emotional response | 11 |

| Difficulty disclosing VUS or positive results* | 11 |

Frequencies <3 not included

7 participants did not answer the open-ended item

Experience with and interest in other methods of communicating genetic test results

Twenty-nine percent of genetic counselors indicated that they had used methods other than in-person communication to share genetic test results, including mail (n=26), email (n=24), telemedicine (n=8), and indirect (to the patient’s physician) (n=7). In many cases, genetic counselors described these as rare events, only used after multiple attempts to schedule an in-person visit or a telephone conversation. Responses to open-ended query regarding other useful modes of communicating genetic test results included videoconferencing/telemedicine (n=40), email (8), and instant messaging (1).

DISCUSSION

The results of our study suggest that the majority of genetic counselors have used telephone to communicate BRCA1/2 test results to patients, although only 30% of participating genetic counselors reported using telephone for disclosure of BRCA1/2 test results the majority of the time. Others have reported similar use of telephone for disclosure BRCA1/2 results among practicing cancer genetic counselors24,25. Our study provides additional detail regarding how telephone communication is incorporated into the delivery of genetic services, as well as, genetic counselors’ experiences with telephone disclosure. Results from our survey indicate that genetic counselors use telephone communication for post-test counseling more frequently than for pre-test counseling. Additionally, genetic counselors reported using telephone disclosure for communication of other types of genetic test results for both cancer, and non-cancer conditions. Thus, an alternative model to in-person pre-test and post-test counseling for genetic testing for hereditary predisposition to cancer and other medical conditions has begun to be adopted in clinical settings.

Participating genetic counselors identified both perceived advantages and disadvantages to telephone communication of genetic test results, highlighting several potential benefits, such as, increased convenience for patients, faster return of results for medical decision-making, and increased patient satisfaction and control. Despite perceptions of potential disadvantages and reports of perceived negative experiences, the majority of participating genetic counselors reported interest in telephone communication of genetic test results. Nonetheless, genetic counselors’ comfort with telephone disclosure varied by the test result. They reported significantly less comfort sharing positive and variant of uncertain significance results by telephone, suggesting less comfort with potentially emotionally distressing or cognitively complex results by telephone. Additionally, genetic counselors reported a variety of patient factors (e.g. financial or medical hardship, preference, comprehension, and psychological well-being) which they consider in deciding to utilize telephone disclosure of BRCA1/2 results, suggesting a need for empirical data to assess the impact of patient factors on adaptation to test results.

While some studies have begun to evaluate outcomes of telephone communication of BRCA1/2 test results, they have included select populations22,23,25,26, such as patients self-selecting the delivery mode23,25. In the only randomized study that has evaluated telephone versus in-person disclosure, Jenkins et al. reported no significant difference in knowledge, anxiety or patient satisfaction between telephone and in-person disclosure of genetic test results22, although this study was not powered to evaluate differences among subgroups, such as different test results. Other relevant outcomes (e.g. performance of risk reduction behaviors, and communication to at-risk family members) and the biopsychosocial factors mediating these outcomes remain poorly described.

Genetic counselors identified perceived advantages and disadvantages of telephone disclosure specific to their practice that are relevant to future studies investigating alternative delivery models for genetic services. Many genetic counselors identified perceived time-savings with telephone communication of genetic test results, although some indicated increased effort associated with additional follow-up calls or activities. The inability to bill for telephone services was reported as a disadvantage and might present a significant barrier to alternative models of delivery. Additionally, many genetic counselors identified discomfort with telephone disclosure in general, or in specific situations. The development of provider training programs and provider experience could help to optimize provider comfort and skills, and potentially patient outcomes.

We acknowledge several limitations to this study. It is possible that genetic counselors interested in, or currently using telephone disclosure may have been more willing to participate in the study. Thus, it is possible that these findings may not represent the experiences and views of a broader population of practicing genetic counselors. Additionally, participants in our study were more likely to practice in academic settings and to have less than 10 years experience in clinical cancer genetic counseling. Thus, the findings in this study may not reflect the opinions and experiences of genetic counselors practicing in non-academic settings and those with more than 10 years experience. This survey was completed in 2008, and practices may have changed since the time of investigation. Additionally, items inquiring about practice frequencies were based on participant recall and participants may have interpreted items inquiring about “interest in” providing genetic test results differently; open-ended items were intended to be exploratory, identifying the spectrum of experiences and opinions. The reported negative experiences might also be reported with in-person disclosure, highlighting the value of randomized studies to evaluate modifications to genetic service delivery models.

Many genetic counselors utilize the telephone to share BRCA1/2 and other genetic test results, however, most, infrequently. While many genetic counselors are interested in telephone disclosure of BRCA1/2 results, they identify potential advantages and disadvantages to telephone disclosure, and recognize the potential impact of testing factors and patient factors on disclosure outcomes. Further research evaluating the potential advantages and disadvantages of telephone disclosure, including the impact of testing and patient factors on cognitive, affective, social and behavioral outcomes is warranted before telephone communication becomes widely and uniformly adopted as standard-of-care.

Acknowledgements

This project is funded, in part, under a grant with the Pennsylvania Department of Health. The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions. Support was also provided by NIH grant P30 CA006927.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Angela R. Bradbury, M.D. – no conflict of interest

Linda Patrick-Miller, Ph.D. – no conflict of interest

Dominique Fetzer, B.A. – no conflict of interest

Brian Egleston, Ph.D. – no conflict of interest

Shelly A. Cummings, M.S. – contributed to this work while employed at the University of Chicago but reviewed and edited the final publication while an employee for Myriad Genetic Laboratories, Inc – Salt Lake City, UT. Ms. Cummings receives stock options from Myriad Genetic Laboratories, Inc.

Andrea Forman, M.S., CGC – no conflict of interest

Lisa Bealin, B.S. – no conflict of interest

Candace Peterson, M.S., CGC – no conflict of interest

Melanie Corbman, M.S., CGC – no conflict of interest

Janice O’Connell, MS, CGC – no conflict of interest

Mary B. Daly, M.D., Ph.D. – no conflict of interest

Contributor Information

Angela R. Bradbury, Department of Clinical Genetics, Fox Chase Cancer Center

Linda Patrick-Miller, Cancer Institute of New Jersey, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey/Robert Wood Johnson Medical School

Dominique Fetzer, Department of Clinical Genetics, Fox Chase Cancer Center Brian Egleston, Ph.D., Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Facility, Fox Chase Cancer Center

Shelly A. Cummings, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago (at time of research); Myriad Genetics, Inc., Salt Lake City, UT, (currently)

Andrea Forman, Department of Clinical Genetics, Fox Chase Cancer Center.

Lisa Bealin, Department of Clinical Genetics, Fox Chase Cancer Center

Candace Peterson, Department of Clinical Genetics, Fox Chase Cancer Center.

Melanie Corbman, Department of Clinical Genetics, Fox Chase Cancer Center.

Janice O’Connell, VIRTUA Fox Chase Cancer Program.

Mary B. Daly, Department of Clinical Genetics, Fox Chase Cancer Center

REFERENCES

- 1.Schwartz GF, Hughes KS, Lynch HT, et al. Proceedings of the international consensus conference on breast cancer risk, genetics, & risk management, April, 2007. Cancer. 2008;113:2627–37. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robson ME, Storm CD, Weitzel J, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 28:893–901. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olopade OI, Grushko TA, Nanda R, et al. Advances in breast cancer: pathways to personalized medicine. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7988–99. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke W, Psaty BM. Personalized medicine in the era of genomics. Jama. 2007;298:1682–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2397–406. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikkelsen EM, Sunde L, Johansen C, et al. Psychosocial consequences of genetic counseling: a population-based follow-up study. Breast J. 2009;15:61–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2008.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berliner JL, Fay AM. Risk Assessment and Genetic Counseling for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer: Recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2007;16:241–260. doi: 10.1007/s10897-007-9090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biesecker BB, Boehnke M, Calzone K, et al. Genetic counseling for families with inherited susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancer. Jama. 1993;269:1970–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broadstock M, Michie S, Marteau T. Psychological consequences of predictive genetic testing: a systematic review. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:731–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch HT, Snyder C, Lynch JF, et al. Patient responses to the disclosure of BRCA mutation tests in hereditary breast-ovarian cancer families. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;165:91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lodder L, Frets PG, Trijsburg RW, et al. Psychological impact of receiving a BRCA1/BRCA2 test result. Am J Med Genet. 2001;98:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Oostrom I, Tibben A. A Counselling Model for BRCA1/2 Genetic Susceptibility Testing. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2004;2:19–23. doi: 10.1186/1897-4287-2-1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calzone KA, Stopfer J, Blackwood A, et al. Establishing a cancer risk evaluation program. Cancer Pract. 1997;5:228–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gattas MR, MacMillan JC, Meinecke I, et al. Telemedicine and clinical genetics: establishing a successful service. J Telemed Telecare. 2001;7(Suppl 2):68–70. doi: 10.1258/1357633011937191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stalker HJ, Wilson R, McCune H, et al. Telegenetic medicine: improved access to services in an underserved area. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12:182–5. doi: 10.1258/135763306777488762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ormond KE, Haun J, Cook L, et al. Recommendations for Telephone Counseling. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2000;9:63–71. doi: 10.1023/A:1009433224504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sangha KK, Dircks A, Langlois S. Assessment of the Effectiveness of Genetic Counseling by Telephone Compared to a Clinic Visit. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2003;12:171–184. doi: 10.1023/A:1022663324006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang VO. Commentary: What Is and Is Not Telephone Counseling? Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2000;9:73–82. doi: 10.1023/A:1009437308575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keating NL, Stoeckert KA, Regan MM, et al. Physicians’ experiences with BRCA1/2 testing in community settings. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5789–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.8053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen WY, Garber JE, Higham S, et al. BRCA1/2 genetic testing in the community setting. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4485–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helmes AW, Culver JO, Bowen DJ. Results of a randomized study of telephone versus in-person breast cancer risk counseling. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenkins J, Calzone KA, Dimond E, et al. Randomized comparison of phone versus in-person BRCA1/2 predisposition genetic test result disclosure counseling. Genet Med. 2007;9:487–95. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e31812e6220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klemp JR, O’Dea A, Chamberlain C, et al. Patient satisfaction of BRCA1/2 genetic testing by women at high risk for breast cancer participating in a prevention trial. Fam Cancer. 2005;4:279–84. doi: 10.1007/s10689-005-1474-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wham D, Vu T, Chan-Smutko G, et al. Assessment of clinical practices among cancer genetic counselors. Fam Cancer. doi: 10.1007/s10689-010-9326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumanis L, Evans JP, Callanan N, et al. Telephoned BRCA1/2 Genetic Test Results: Prevalence, Practice, and Patient Satisfaction. J Genet Couns. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10897-009-9238-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz MD, Lerman C, Brogan B, et al. Impact of BRCA1/BRCA2 counseling and testing on newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1823–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolfberg AJ. Genes on the Web--direct-to-consumer marketing of genetic testing. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:543–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pope C, van Royen P, Baker R. Qualitative methods in research on healthcare quality. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:148–52. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.2.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, editors. Analysing Qualitative Data. Routledge; London: 1994. pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott SE, Grunfeld EA, Main J, et al. Patient delay in oral cancer: a qualitative study of patients’ experiences. Psychooncology. 2006;15:474–85. doi: 10.1002/pon.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velikova G, Awad N, Coles-Gale R, et al. The clinical value of quality of life assessment in oncology practice-a qualitative study of patient and physician views. Psychooncology. 2008;17:690–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weaver NF, Hayes L, Unwin NC, et al. “Obesity” and “Clinical Obesity” Men’s understandings of obesity and its relation to the risk of diabetes: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:311. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Husain LS, Collins K, Reed M, et al. Choices in cancer treatment: a qualitative study of the older women’s (>70 years) perspective. Psychooncology. 2008;17:410–6. doi: 10.1002/pon.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradbury AR, Patrick-Miller L, Pawlowski K, et al. Should genetic testing for BRCA1/2 be permitted for minors? Opinions of BRCA mutation carriers and their adult offspring. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2008;148C:70–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agresti A. Catagorical Data Analysis. Second edition John Wiley and Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bowker AH. A test for symmetry in contingency tables. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1948;43:572–574. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1948.10483284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hosmer DW, Lameshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. ed 2nd. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 2000. New York. [Google Scholar]