Abstract

The cJun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) signal transduction pathway has been implicated in the growth of carcinogen-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. However, the mechanism that accounts for JNK-regulated tumor growth is unclear. Here we demonstrate that compound deficiency of the two ubiquitously expressed JNK isoforms (JNK1 and JNK2) in hepatocytes does not prevent hepatocellular carcinoma development. Indeed, JNK deficiency in hepatocytes increased the tumor burden. In contrast, compound JNK deficiency in hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells reduced both hepatic inflammation and tumorigenesis. These data indicate that JNK plays a dual role in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. JNK promotes an inflammatory hepatic environment that supports tumor development, but also functions in hepatocytes to reduce tumor development.

Keywords: JNK, partial hepatectomy, hepatocellular carcinoma

The cJun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway is implicated in tumor development (Davis 2000). Targets of JNK signaling include members of the activating protein 1 (AP1) transcription factor group (e.g., cJun, JunB, JunD, and related proteins). These transcription factors function within a regulatory network that controls multiple aspects of cellular physiology, including proliferation (Eferl and Wagner 2003). Studies of murine embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) demonstrate that loss of JNK causes major defects in cellular proliferation (Tournier et al. 2000) and AP1-dependent gene expression (Ventura et al. 2003). These effects of JNK are mediated, in part, by the AP1 transcription factor. Indeed, cJun phosphorylation is required for normal serum-stimulated cell growth (Behrens et al. 1999). The JNK signaling pathway therefore represents an important regulatory mechanism that can control growth. Moreover, dysregulated JNK may contribute to tumor development (Davis 2000).

Studies of the role of the JNK and cJun in the liver have confirmed the importance of this signaling pathway in growth regulation. Thus, cJun-deficient mice (Behrens et al. 2002; Stepniak et al. 2006), JNK1-deficient mice (Hui et al. 2008), and mice treated with a JNK inhibitor (Schwabe et al. 2003) exhibit major defects in liver regeneration following partial hepatectomy (PHx). Furthermore, both cJun-deficient mice (Eferl et al. 2003) and JNK1-deficient mice (Sakurai et al. 2006; Hui et al. 2008) are protected against the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) following exposure to the carcinogen diethylnitrosamine (DEN). The critical role of JNK in HCC has been confirmed by pharmacological inhibition of JNK and studies of human HCC cells (Hui et al. 2008).

The mechanism of JNK and cJun signaling in the liver that contributes to regeneration and HCC is unclear, but down-regulation of the proliferation inhibitor p21CIP1 and up-regulation of the growth promoter cMyc appear to be critical factors (Stepniak et al. 2006; Hui et al. 2008). An alternative mechanism for the contribution of JNK to HCC is represented by the role of compensatory proliferation in hepatic tumor development (Fausto 1999). It has been reported that JNK1 is required for hepatocyte death in the DEN model of HCC (Sakurai et al. 2006). Reduced hepatocyte death in JNK1-deficient mice results in reduced compensatory proliferation and suppression of HCC (Sakurai et al. 2006). These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive, and it is possible that JNK plays multiple roles in HCC, including regulation of cell death and gene expression. Nevertheless, a common theme among these mechanisms is that JNK plays a critical role in hepatocytes that is required for HCC development.

The purpose of this study was to examine the role of JNK in the development of HCC. Specifically, we tested whether JNK in hepatocytes contributes to tumor formation. Previous studies have focused on an analysis of Jnk1−/− mice (Sakurai et al. 2006; Hui et al. 2008). Here we report the analysis of mice with tissue-specific deficiency of JNK and mice with compound deficiency of both JNK1 and JNK2. Our analysis demonstrates that compound JNK deficiency in hepatocytes increases the development of HCC. JNK therefore functions in liver parenchymal cells to reduce tumor development. We show that the protumorigenic effects of JNK on HCC are associated with inflammation and require JNK function in nonparenchymal cells.

Results

Compound JNK deficiency in hepatocytes does not prevent liver regeneration following PHx

PHx causes JNK activation and a robust regeneration response that results in rapid restoration of liver mass (Westwick et al. 1995). It has been reported that Jnk1−/− mice exhibit a defect in the regeneration response to PHx (Hui et al. 2008). In initial studies, we compared hepatic regeneration in control mice, Jnk1−/− mice, and Jnk2−/− mice following PHx. This analysis demonstrated similar hepatic regeneration in control and Jnk2−/− mice, but hepatic regeneration was suppressed in Jnk1−/− mice (Supplemental Fig. S1). These data indicate that JNK1 may play an important role in hepatocyte proliferation (Hui et al. 2008).

The Jnk1 and Jnk2 genes are both expressed in hepatocytes (Davis 2000). Consequently, the reduced hepatic regeneration detected in Jnk1−/− mice (Supplemental Fig. S1) is not caused by loss of total JNK in hepatocytes. These considerations indicated that studies of hepatic regeneration in mice with compound ablation of Jnk1 plus Jnk2 are required. We employed a conditional gene ablation strategy using Alb-Cre transgenic mice to create animals with compound deficiency of JNK1 plus JNK2 in hepatocytes (Das et al. 2009). Control HWT mice (Alb-Cre+/−) and JNK-deficient HΔJNK mice (Alb-Cre+/− Jnk1LoxP/LoxP Jnk2−/−) were examined following PHx or a sham surgical procedure (Fig. 1A).

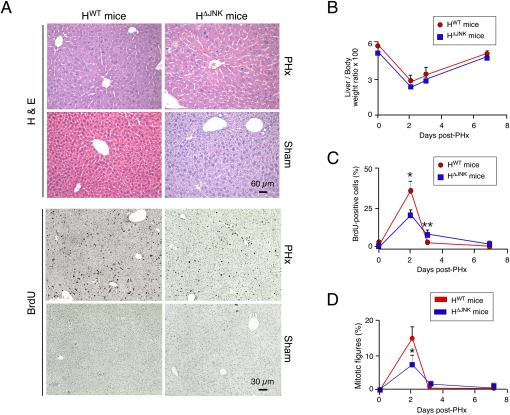

Figure 1.

JNK deficiency in hepatocytes does not prevent liver regeneration after PHx. (A) Control mice (HWT mice: Alb-Cre-/+) and JNK-deficient mice (HΔJNK mice: Alb-Cre-/+ Jnk1LoxP/LoxP Jnk2−/−) were subjected to two-thirds PHx or a sham procedure. The mice were injected (i.p.) with 100 μg/g BrdU (dissolved in saline) at 2 h prior to euthanasia. Representative sections of liver from mice at 48 h post-surgery were stained with H&E (top panels) and an antibody to BrdU (bottom panels). (B) The liver/body weight ratio was calculated and expressed as the mean percentage ± SD (n = 6 mice) in HWT and HΔJNK mice. No statistically significant differences between HWT and HΔJNK mice were detected. (C) The percentage of BrdU-positive hepatocytes in HWT and HΔJNK mice (mean ± SD; n = 8 mice) is presented. Statistically significant differences between HWT and HΔJNK mice are indicated. (*) P < 0.05; (**) P < 0.001. (D) The percentage of hepatocyte mitotic figures detected in H&E-stained sections of liver from HWT and HΔJNK mice (mean ± SD; n = 8 mice) is presented. Statistically significant differences between HWT and HΔJNK mice are indicated. (*) P < 0.05.

Biochemical analysis of the liver of HWT and HΔJNK mice at 48 h post-PHx demonstrated that JNK deficiency did not significantly change the expression of cJun, JunB, or Cyclin D1 mRNA, but a modest reduction in JunD mRNA expression was detected in the liver of HΔJNK mice compared with HWT mice (Supplemental Fig. S2A). These changes were associated with reduced activation of JNK and reduced phosphorylation of cJun in the liver of HΔJNK mice compared with HWT mice (Supplemental Fig. S2B). These observations are consistent with ablation of the JNK signaling pathway in the hepatocytes of HΔJNK mice. We detected no statistically significant changes in activation of AKT or the ERK and p38 MAPKs in the JNK-deficient liver compared with control liver (Supplemental Fig. S2B).

Measurement of hepatic mass demonstrated that compound deficiency of JNK1 plus JNK2 in hepatocytes caused no significant change in regeneration (Fig. 1B). To confirm this conclusion, we examined hepatocyte proliferation by measuring the incorporation of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) (Fig. 1A). This analysis demonstrated increased BrdU incorporation at 48 h post-PHx in both HWT and HΔJNK mice, but the amount of BrdU incorporation was reduced in HΔJNK mice compared with HWT mice (Fig. 1C). This reduction in BrdU incorporation is consistent with the reduced number of mitotic figures detected in hepatocytes of HΔJNK mice compared with HWT mice at 48 h post-PHx (Fig. 1D). However, a time-course analysis demonstrated that the overall hepatic proliferation in HWT and HΔJNK mice following PHx was similar (Fig. 1C,D). These data demonstrate that compound JNK deficiency does not prevent hepatic regeneration following PHx.

The discovery that mice with compound JNK deficiency in hepatocytes were capable of hepatic regeneration following PHx was unexpected for two reasons. First, hepatic regeneration is strongly reduced in Jnk1−/− mice (Supplemental Fig. S1; Hui et al. 2008). Second, studies of Jnk1−/− Jnk2−/− primary MEFs demonstrate that these JNK-deficient cells exhibit severe defects in proliferation, including early senescence (Tournier et al. 2000; Das et al. 2007). Compound JNK deficiency was therefore anticipated to similarly cause growth retardation in other cell types, including hepatocytes. We therefore sought to confirm that liver regeneration following PHx is JNK-independent using a different mouse model with compound hepatic JNK deficiency (Supplemental Fig. S3). Together, these data confirm the conclusion that hepatic regeneration following PHx occurs in mice with deficiency of both JNK1 and JNK2 in the liver (Fig. 1; Supplemental Fig. S3). JNK is therefore not essential for hepatic regeneration.

JNK deficiency in hepatocytes promotes HCC

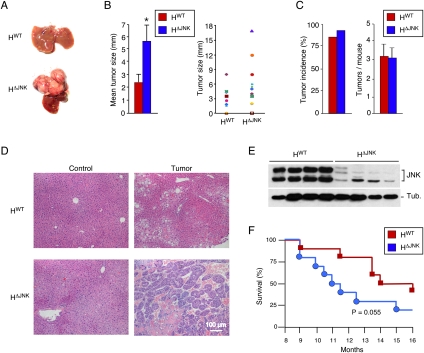

The conclusion that JNK is not essential for hepatic regeneration led us to question whether JNK is required for hepatocyte proliferation in the context of HCC. We therefore tested whether JNK in hepatocytes is required for HCC development by treating HWT and HΔJNK mice with the carcinogen DEN. Previous reports indicate that DEN-induced HCC is markedly reduced in Jnk1−/− mice (Sakurai et al. 2006; Hui et al. 2008). In contrast, we found that HΔJNK mice developed HCC following exposure to DEN (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Fig. S4). Indeed, the tumor size in HΔJNK mice was significantly greater than in HWT mice (Fig. 2B). However, no significant difference in tumor incidence or the number of tumor nodules between HWT and HΔJNK mice was detected (Fig. 2C). This effect of JNK deficiency to increase HCC was associated with increased hepatic expression of cJun (Supplemental Fig. S5A). Histological analysis of hepatic sections demonstrated the presence of lesions ranging from adenoma to carcinoma in HWT mice, but primarily carcinoma in HΔJNK mice (Fig. 2D; Supplemental Figs. S6, S7). Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that HΔJNK tumors were JNK deficient (Fig. 2E). Together, these data indicate that JNK in hepatocytes acts as to reduce tumor development in this model of HCC. However, Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that the increased tumor burden in the HΔJNK mice did not cause a statistically significant (P = 0.055) change in survival compared with HWT mice (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

Effect of hepatocyte-specific JNK deficiency on HCC. (A) DEN-induced HCC in control mice (HWT mice: Alb-Cre+/−) and JNK-deficient mice (HΔJNK mice: Alb-Cre+/− Jnk1LoxP/LoxP Jnk2−/−) at 38 wk of age. (B) The maximum diameter of individual tumor nodules (right panel) and the mean ± SD (n = 13) width of the tumor nodules (left panel) are presented. Statistically significant differences between HWT and HΔJNK mice are indicated. (*) P < 0.05. (C) The tumor incidence (left panel) and the number of tumors per mouse (right panel) were examined (n = 14). No statistically significant differences between HWT and HΔJNK mice were detected. (D) Representative sections of liver from mice treated without DEN (control) and with DEN (tumor) stained with H&E are presented. (E) Immunoblot analysis of tumors isolated from HWT mice and HΔJNK mice was performed by probing with antibodies to JNK and α-Tubulin (Tub.). (F) Kaplan-Meier analysis of the survival of HWT mice and HΔJNK mice (n = 10) treated with DEN is presented. No statistically significant difference between the survival or mortality of HWT mice and HΔJNK mice was detected (log-rank test; P = 0.055).

JNK deficiency can prevent HCC development

The finding that JNK in hepatocytes acts to reduce HCC (Fig. 2) was not anticipated because studies of Jnk1−/− mice (but not Jnk2−/− mice) have indicated that JNK plays a critical role in HCC development (Sakurai et al. 2006; Hui et al. 2008). Together, these findings suggest that JNK may both inhibit and promote tumor formation during DEN-induced HCC development. The protumorigenic role of JNK does not require the function of JNK in hepatocytes (Fig. 2), but may involve functions of JNK in nonparenchymal cells. To test this hypothesis, we examined DEN-induced HCC development in mice with compound JNK deficiency using Mx-1-Cre mice and conditional gene ablation in hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells (Das et al. 2009).

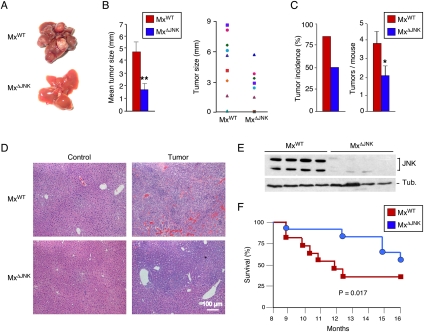

Control MxWT mice (Mx-1-Cre+/−) and JNK-deficient MxΔJNK mice (Mx-1-Cre+/− Jnk1LoxP/LoxP Jnk2−/−) were tested for HCC development. We found that HCC was strongly suppressed in MxΔJNK mice compared with MxWT mice (Fig. 3A; Supplemental Fig. S4). The tumor size in MxΔJNK mice was significantly smaller than in MxWT mice (Fig. 3B). Moreover, both the tumor incidence and the number of tumor nodules were reduced in MxΔJNK mice compared with MxWT mice (Fig. 3C). This effect of JNK deficiency to suppress HCC was associated with markedly reduced hepatic expression of cJun (Supplemental Fig. S5B). Histological analysis of hepatic tissue sections demonstrated lesions ranging from adenoma to carcinoma in MxWT mice, but primarily only localized adenoma were detected in MxΔJNK mice (Fig. 3D; Supplemental Figs. S7, S8). Immunoblot analysis demonstrated that MxΔJNK tumors were JNK-deficient (Fig. 3E). Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that the reduced tumor burden in MxΔJNK mice caused significantly increased survival (P = 0.017) compared with MxWT mice (Fig. 3F). Together, these data demonstrate that JNK can play a protumorigenic role in HCC development. This protumorigenic role does not require JNK in hepatocytes (Fig. 2), but does require JNK in nonparenchymal cells (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of hepatic JNK deficiency on HCC. (A) DEN-induced HCC in control mice (MxWT mice: Mx1-Cre+/−) and JNK-deficient mice (MxΔJNK mice: Mx1-Cre+/− Jnk1LoxP/LoxP Jnk2−/−) at 38 wk of age. The JNK-deficient mice lack expression of JNK1 plus JNK2 in both hepatocytes and nonparenchemyal hepatic cells. (B) The maximum diameter of individual tumor nodules (right panel) and the mean ± SD (n = 13) width of the tumor nodules (left panel) are presented. Statistically significant differences between MxWT and MxΔJNK mice are indicated. (*) P < 0.05; (**) P < 0.01. (C) The tumor incidence (left panel) and the number of tumors per mouse (right panel) were examined (n = 16). Statistically significant differences between MxWT and MxΔJNK mice are indicated. (*) P < 0.05. (D) Representative sections of liver from mice treated without DEN (control) and with DEN (tumor) stained with H&E are presented. (E) Immunoblot analysis of tumors isolated from MxWT mice and MxΔJNK mice was performed by probing with antibodies to JNK and α-Tubulin (Tub.). (F) Kaplan-Meier analysis of the survival of MxWT mice and MxΔJNK mice (n = 11) treated with DEN is presented. The survival of MxWT mice was significantly shorter than MxΔJNK mice (log-rank test; P = 0.017).

JNK regulation of HCC proliferation mediated by p21CIP1 and cMyc

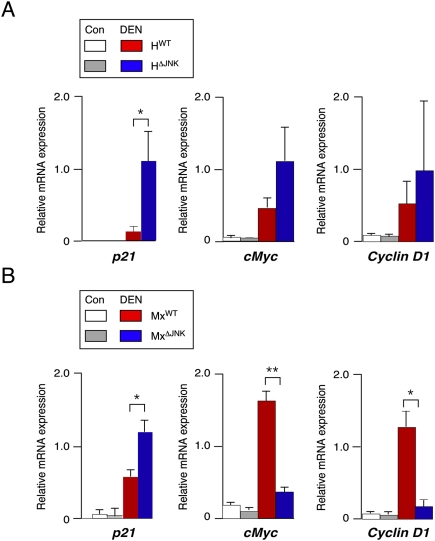

JNK-mediated transcriptional down-regulation of the growth inhibitor p21CIP1 and up-regulation of the growth promoter cMyc have been implicated as critical steps during HCC development (Hui et al. 2008). We therefore examined p21CIP1 and cMyc expression in the liver of mice with compound deficiency of JNK1 plus JNK2 (Fig. 4). We found that p21CIP1 expression was significantly increased in DEN-treated JNK-deficient mice (HΔJNK and MxΔJNK) compared with DEN-treated control mice (HWT and MxWT) (Fig. 4). Since HCC is increased in HΔJNK mice (Fig. 2) and decreased in MxΔJNK mice (Fig. 3), these data demonstrate no correlation between p21CIP1 expression and HCC development in compound JNK-deficient mice. In contrast, an association between JNK, expression of cMyc, and HCC development was detected. No significant difference between cMyc expression between tumors in mice with (HΔJNK) and without (HWT) compound JNK deficiency in hepatocytes was observed (Fig. 4A). However, cMyc expression in tumors of mice with compound JNK deficiency in hepatocytes plus nonparenchymal cells (MxΔJNK) was strongly reduced compared with tumors of control (MxWT) mice (Fig. 4B). This down-regulation of cMyc expression (Fig. 4B) correlates with markedly decreased expression of Cyclin D1 (Fig. 4B) and decreased tumor formation (Fig. 3). Together, these data support a potential role for JNK-regulated expression of cMyc, but not p21CIP1, during HCC development.

Figure 4.

Effect of JNK deficiency on p21CIP1 and cMyc expression in HCC. Mice were treated without (Con) or with DEN and euthanized at 38 wk of age. The expression of p21CIP1, cMyc, and Cyclin D1 mRNA was examined by RT–PCR using TaqMan assays. The data presented are normalized for the amount of Gapdh mRNA in each sample and represent the mean ± SD (n = 5). Statistically significant differences are indicated. (*) P < 0.05. (A) Control mice (HWT) and mice with JNK deficiency in hepatocytes (HΔJNK). (B) Control mice (MxWT) and mice with JNK deficiency in hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells (MxΔJNK).

JNK regulates compensatory proliferation during HCC development

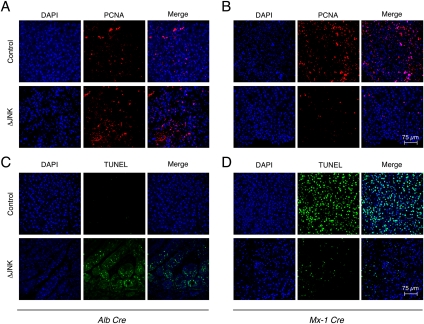

It is established that compensatory hepatocyte proliferation plays a major role in the development of HCC (Fausto 1999). This form of hepatocyte proliferation represents a regenerative response to hepatocyte death that is associated with inflammation (Grivennikov et al. 2010). We therefore examined hepatocyte proliferation and death in control mice (HWT and MxWT) and mice with compound deficiency of JNK1 plus JNK2 (HΔJNK and MxΔJNK) following treatment with DEN. Sections of liver tumors were stained for the proliferation marker PCNA (Fig. 5A,B) and for cell death using the TUNEL assay (Fig. 5C,D). We also examined caspase activation by immunoblot analysis of Caspase 3 processing to the activated form (Supplemental Fig. S9). Studies of mice with hepatocyte-specific compound JNK deficiency (HΔJNK mice) demonstrated increased cell death and increased proliferation compared with control HWT mice (Fig. 5A,C; Supplemental Fig. S9). In contrast, compound deficiency of JNK in hepatocytes plus nonparenchymal cells (MxΔJNK mice) caused both reduced cell death and reduced proliferation compared with control MxWT mice (Fig. 5B,D; Supplemental Fig. S9). These data suggest that decreased compensatory proliferation may account for the reduction in tumor growth caused by JNK in hepatocytes, and that increased compensatory proliferation may account for the protumorgenic activity of JNK in nonparenchymal cells.

Figure 5.

Effect of JNK deficiency on hepatocyte death and compensatory proliferation. (A–D) Control mice (HWT and MxWT) and JNK-deficient (ΔJNK) mice (HΔJNK and MxΔJNK) were treated with DEN. Hepatic tissue sections of mice (age 38 wk) were examined by staining with an antibody to the proliferation marker PCNA (A,B) or by TUNEL assay (C,D). DNA was stained with DAPI. Quantitation of triplicate independent samples demonstrated that 29.0% ± 1.1% of HWT and 49.9% ± 7.2% of HΔJNK nuclei were positive for PCNA (P < 0.05), 61.1% ± 12.5% of MxWT and 17.4% ± 1.4% of MxΔJNK nuclei were positive for PCNA (P < 0.05), 2.5% ± 1.2% of HWT and 32.4% ± 6.1% of HΔJNK nuclei were TUNEL-positive (P < 0.01), and 44.2% ± 6.6% of MxWT and 10.7% ± 2.3% of MxΔJNK nuclei were TUNEL-positive (P < 0.01).

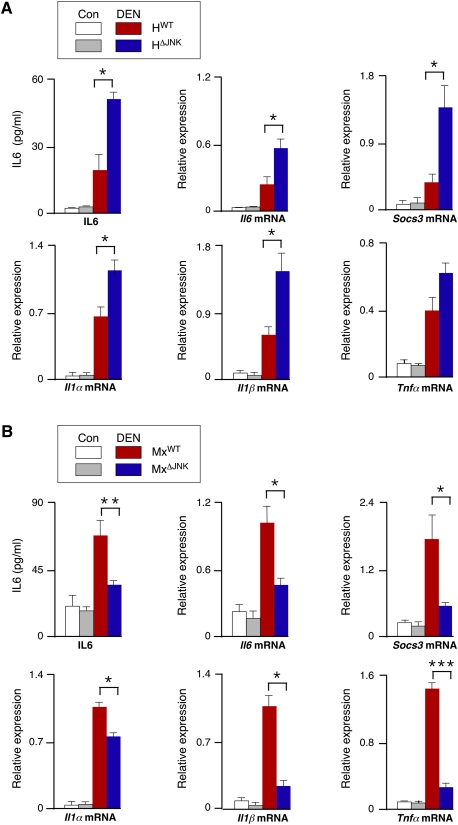

JNK regulates the expression of hepatic cytokines

The compensatory proliferation caused by hepatocyte death (Fausto 1999) may be mediated by the release of IL1α by necrotic cells (Chen et al. 2007; Sakurai et al. 2008) and the subsequent expression of protumorigenic IL6 (and also TNFα in obese mice) by hepatic innate immune cells (Naugler et al. 2007; Park et al. 2010). Indeed, HCC development in mice can be suppressed by ablation of the Il6 and Tnfα genes (Naugler et al. 2007; Park et al. 2010). We therefore examined the expression of inflammatory cytokines in control and JNK-deficient mice (Fig. 6). Studies of mice with compound deficiency of JNK1 plus JNK2 in hepatocytes (HΔJNK mice) demonstrated that JNK deficiency caused increased hepatic expression of Il1α, Il1β, Il6, and Tgfβ1 mRNA (Fig. 6A; Supplemental Fig. S10). In contrast, studies of mice with compound deficiency of JNK1 and JNK2 in hepatocytes plus nonparenchymal cells (MxΔJNK mice) demonstrated that JNK deficiency caused decreased expression of Il1α, Il1β, Il6, Tgfβ1, and Tnfα mRNA (Fig. 6B; Supplemental Fig. S10).

Figure 6.

Effect of JNK deficiency on the expression of hepatic cytokines. (A,B) HWT and HΔJNK mice (A) or MxWT and MxΔJNK mice (B) were treated without (Con) or with DEN and euthanized at 38 wk of age. The blood concentration of IL6 was measured by ELISA and is presented as the mean ± SD (n = 7). Total RNA was isolated from the liver, and the expression of Il1α, Il1β, Il6, Socs3, and Tnfα mRNA was examined by RT–PCR using TaqMan assays. The data presented are normalized for the amount of Gapdh mRNA in each sample and represent the mean ± SD (n = 5). Statistically significant differences between the control and JNK-deficient mice are indicated (P < 0.05).

Together, these data indicate that JNK deficiency in hepatocytes (HΔJNK mice) causes increased cell death (Fig. 5C; Supplemental Fig. S9), increased expression of inflammatory cytokines (Figs. 6A; Supplemental Fig. S10), and increased compensatory hepatocyte proliferation (Fig. 5A). However, JNK deficiency in hepatocytes plus nonparenchymal cells (MxΔJNK mice) causes decreased cell death (Fig. 5D; Supplemental Fig. S9), decreased expression of inflammatory cytokines (Figs. 6B; Supplemental Fig. S10), and decreased compensatory hepatocyte proliferation (Fig. 5B). The primary actions of JNK disrupted in HΔJNK mice may reflect a role for JNK in cell survival (Lamb et al. 2003) and thus decreased compensatory proliferation. The primary actions of JNK disrupted in MxΔJNK mice may be expression of the protumorigenic cytokines IL6 and TNFα (Sabio et al. 2008; Das et al. 2009).

The role of IL6 in JNK-regulated development of HCC

It is established that IL6 plays a key role in hepatocyte proliferation (Cressman et al. 1996), and that IL6 is critically required for DEN-induced HCC (Naugler et al. 2007). We therefore examined the hepatic IL6 signaling pathway in mice with compound JNK deficiency. Treatment of control mice with DEN caused an increase in hepatic Il6 mRNA and IL6 protein in the blood (Fig. 6). The Socs3 gene is a target of IL6-stimulated STAT3 signaling in the liver. Treatment of mice with DEN caused increased Socs3 mRNA expression (Fig. 6). This DEN-induced increase in Socs3 gene expression was suppressed in MxΔJNK mice (Fig. 6B) and potentiated in HΔJNK mice (Fig. 6A). These data are consistent with the increased HCC and hepatic IL6 expression in HΔJNK mice (Figs. 2, 6A) and reduced HCC and hepatic IL6 expression in MxΔJNK mice (Figs. 3, 6B).

The miR-21 gene has been identified as a target of inflammatory signaling pathways, including IL6 (Jazbutyte and Thum 2010). Indeed, treatment of mice with IL6 caused increased hepatic expression of miR-21 (Supplemental Fig. S11), and it is established that IL6-induced miR-21 expression is mediated by two conserved STAT3-binding sites in the miR-21 promoter (Loffler et al. 2007). The expression of miR-21 in the liver is increased during HCC development (Kutay et al. 2006; Meng et al. 2007; Connolly et al. 2008; Jiang et al. 2008), and studies using a knockdown approach demonstrate that miR-21 contributes to HCC proliferation (Connolly et al. 2008). These data establish that miR-21 plays an important role in HCC development.

We examined the effect of JNK deficiency on hepatic expression of miR-21. Control studies demonstrated that DEN caused increased expression of miR-21 (Supplemental Fig. S12). Hepatocyte-specific JNK deficiency (HΔJNK mice) caused increased miR-21 expression compared with control (HWT) mice following treatment with DEN (Supplemental Fig. S13A). In contrast, DEN-treated mice with JNK deficiency in hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells (MxΔJNK) expressed reduced miR-21 compared with control (MxWT) DEN-treated mice (Supplemental Fig. S13A). These effects of JNK deficiency on miR-21 expression are consistent with the observed increase (HΔJNK) and decrease (MxΔJNK) in the expression of hepatic IL6 (and other inflammatory cytokines) following DEN treatment (Fig. 6; Supplemental Fig. S10).

Targets of miR-21 include repressors of the AKT (Pten) and receptor tyrosine kinase (Sprouty) signaling pathways (Cabrita and Christofori 2008). We therefore examined Pten and Sprouty expression in DEN-treated control (MxWT) mice and JNK-deficient (MxΔJNK) mice. JNK deficiency did not change the expression of Pten or Sprouty mRNA (Supplemental Fig. S13C,D). Similarly, JNK deficiency did not cause altered expression of PTEN protein (Supplemental Fig. S13D). In contrast, JNK deficiency caused increased expression of Sprouty protein (Supplemental Fig. S13C). To test whether this increased expression of Sprouty is functionally relevant, we examined signaling pathways downstream from activated receptor tyrosine kinases, including AKT and ERK. We found that increased expression of the negative regulator Sprouty in JNK-deficient (MxΔJNK) mice was associated with reduced AKT and ERK activity (Supplemental Fig. S13B). These data suggest that Sprouty (Supplemental Fig. S13C) may be a relevant target of the miR-21 pathway that is required for HCC development (Connolly et al. 2008).

Discussion

The role of JNK in proliferation is cell type-dependent

It is established that JNK is critically required for the proliferation of primary MEFs (Davis 2000). Compound mutant Jnk1−/− Jnk2−/− MEFs exhibit a severe growth retardation phenotype (Tournier et al. 2000) and premature senescence (Das et al. 2007). The rapid senescence of primary Jnk1−/− Jnk2−/− MEFs is mediated by increased expression of the Trp53 tumor suppressor (Das et al. 2007). This engagement of p53-dependent senescence in primary Jnk1−/− Jnk2−/− MEFs (Das et al. 2007) is similar to cJun−/− MEFs (Schreiber et al. 1999). Indeed, reduced expression of cJun by Jnk1−/− Jnk2−/− MEFs may contribute to the early senescence phenotype (Ventura et al. 2003). These observations indicate that JNK may have a general role in the proliferation of many cell types. Reports that JNK1 plays an essential role in both hepatic regeneration following PHx (Hui et al. 2008) and DEN-induced HCC (Sakurai et al. 2006; Hui et al. 2008) are consistent with this conclusion.

The finding that compound JNK deficiency does not prevent hepatocyte proliferation was unexpected (Figs. 1, 2; Supplemental Fig. S3). The simplest explanation for these data is that JNK is not required for proliferation of hepatocytes (Fig. 1; Supplemental Fig. S3), but JNK is selectively required to prevent Trp53-dependent senescence of MEFs (Das et al. 2007). Cell type-specific responses to JNK deficiency may reflect differences in the requirement of JNK for the expression of cJun, a repressor of the Trp53 promoter (Schreiber et al. 1999). Compound JNK deficiency in MEFs causes down-regulation of cJun expression (Ventura et al. 2003). In contrast, compound JNK deficiency in hepatocytes did not cause significantly decreased cJun expression (Supplemental Fig. S2A). The failure of JNK deficiency to down-regulate cJun expression in hepatocytes may reflect signaling pathway redundancy, including roles of JNK in AP1-dependent cJun expression (Ventura et al. 2003) and p38 MAPK in MEF2-dependent cJun expression (Han et al. 1997). Indeed, it is intriguing that the p38 MAPK pathway in hepatocytes is constitutively activated and subject to metabolic regulation (Mendelson et al. 1996), but p38 MAPK is stress-inducible from a low basal activity in MEFs (Raingeaud et al. 1995). The p38 MAPK pathway may therefore act redundantly with JNK to regulate cJun expression in hepatocytes, but the p38 MAPK pathway may not compensate for JNK deficiency in MEFs. Cross-talk, partially redundant signaling, and partially antagonistic signaling by the JNK and p38 MAPK pathways may therefore contribute to the tissue-specific effects of JNK on proliferation (Wagner and Nebreda 2009).

The role of JNK in liver regeneration

The function of JNK in hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells of the liver is not required for hepatic regeneration following PHx (Fig. 1; Supplemental Fig. S3). Nevertheless, liver regeneration is reduced in Jnk1−/− mice (Supplemental Fig. S1; Hui et al. 2008). The mechanism that accounts for this phenotype of Jnk1−/− mice is unclear. The simplest hypothesis is that JNK1 plays a critical role in a nonhepatic tissue, and that this JNK1-dependent function is disrupted in Jnk1−/− mice. The identity of the relevant tissue that mediates JNK1-dependent hepatic regeneration has not been established. One possibility is represented by the hypothalamus, a region of the brain that strongly influences liver regeneration (Kiba 2002). This possibility is consistent with the discovery that the major metabolic phenotypes of Jnk1−/− mice are largely accounted for by the effects of JNK1 deficiency in the hypothalamus, rather than in peripheral tissues (Belgardt et al. 2010; Sabio et al. 2010). A goal for further studies will be to identify the specific tissue that accounts for the required role of JNK1 for hepatic regeneration. This role of JNK1 contrasts with the absence of a requirement for hepatic JNK during liver regeneration following PHx (Fig. 1; Supplemental Fig. S3).

The role of JNK in the promotion of HCC

It is established that JNK plays a key role in the development of DEN-induced HCC (Sakurai et al. 2006; Hui et al. 2008). Two mechanisms have been reported to account for JNK-mediated protumorigenic activity. First, JNK1 may be required for down-regulation of p21CIP1 expression and up-regulation of cMyc expression (Hui et al. 2008). Our analysis demonstrates that p21CIP1 expression does not correlate with tumorigenic potential in studies of HCC development in compound JNK-deficient mice (HΔJNK and MxΔJNK) (Fig. 4). In contrast, expression of cMyc (Fig. 4) correlates with the tumor burden in HΔJNK and MxΔJNK mice (Figs. 2, 3). These data are consistent with a role for cMyc in JNK-dependent formation of HCC (Hui et al. 2008).

A second proposed mechanism is that JNK1 causes hepatocyte death (Sakurai et al. 2006), resulting in compensatory proliferation that contributes to the development of HCC (Fausto 1999). However, compound deficiency of JNK1 and JNK2 in hepatocytes (HΔJNK mice) does not inhibit hepatocyte death following treatment with DEN (Fig. 5C; Supplemental Fig. S9). These data demonstrate that JNK-mediated hepatocyte death does not contribute to compensatory proliferation and HCC. This analysis indicates that another mechanism must account for the protumorigenic effects of JNK on HCC development.

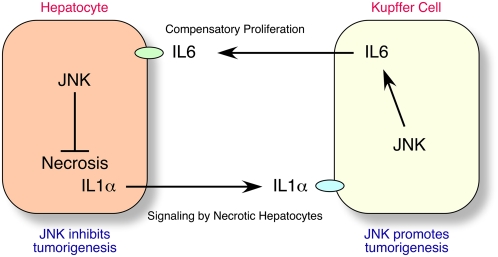

The observation that compound JNK deficiency in hepatocytes (HΔJNK mice) does not reduce DEN-induced HCC (Fig. 2), but compound JNK deficiency in hepatocytes plus nonparenchymal cells (MxΔJNK mice) does reduce DEN-induced HCC (Fig. 3), provides important insight into the mechanism of JNK-promoted HCC development. These findings indicate that the protumorigenic function of JNK may be localized to nonparenchymal cells, rather than hepatocytes. Indeed, functions of nonparenchymal cells are implicated in HCC development (Maeda et al. 2005; Grivennikov et al. 2010). Specifically, the release of IL1α by necrotic cells (Chen et al. 2007; Sakurai et al. 2008), and the subsequent expression of the protumorigenic cytokine IL6 (and also TNFα in obese mice) by hepatic innate immune cells, including Kupffer cells (Naugler et al. 2007; Park et al. 2010), may drive compensatory hepatocyte proliferation and, subsequently, HCC (Fig. 7). It is therefore significant that compound JNK deficiency in MxΔJNK mice, but not HΔJNK mice, causes markedly decreased expression of IL6 and TNFα (Fig. 6). These data are consistent with the conclusion that JNK is required for the expression of the protumorigenic cytokines IL6 and TNFα by hepatic innate immune cells during the development of HCC (Fig. 6B). Thus, the protumorigenic activity of JNK may be mediated by a role for JNK in nonparenchymal cells (Fig. 3) in the creation of an inflammatory environment that supports HCC development (Grivennikov et al. 2010). The previously described genetic interactions between Jnk1 and p21CIP1 (Hui et al. 2008) may therefore reflect an inhibitory action of p21CIP1 on hepatic innate immune cells, rather than hepatocytes. Studies using mice with tissue-specific p21CIP1 deficiency will be required to resolve this question.

Figure 7.

JNK functions in hepatocytes to reduce HCC development and in nonparenchymal cells to promote HCC development. JNK in nonparenchymal cells functions to promote HCC development by providing an inflammatory environment that supports HCC, including the expression of the protumorigenic cytokines IL6 and TNFα that contribute to compensatory hepatocyte proliferation. However, JNK in hepatocytes functions to reduce HCC development by promoting hepatocyte survival, therefore decreasing IL1α release by necrotic hepatocytes and the activation of hepatic innate immune cells, including Kupffer cells, that express the protumorgenic cytokine IL6.

The role of JNK in hepatocytes during HCC development

Studies of mice with compound deficiency of JNK1 plus JNK2 demonstrate that cell death and compensatory proliferation are key targets of JNK function in HCC (Fig. 5). Specifically, we find that compound JNK deficiency in hepatocytes causes increased hepatocyte death and, consequently, increased compensatory proliferation and HCC development (Figs. 2, 5). The increased death caused by compound JNK deficiency is consistent with previous studies that demonstrate a role for JNK in cell survival (Kuan et al. 1999; Lamb et al. 2003) and the presence of JNK-independent pathways that can mediate hepatocyte death (Das et al. 2009). Although the cell type of HCC origin is unclear (Mishra et al. 2009), tumors detected using Albumin-Cre transgenic mouse models of DEN-induced HCC demonstrate efficient ablation of floxed genes in tumor cells (Fig. 2E; Maeda et al. 2005). These data suggest that JNK in hepatic parenchymal cells functions to reduce tumor development in the DEN model of HCC. This effect of JNK to influence hepatocyte death, compensatory proliferation, and HCC development (Figs. 2, 5) is similar to the reported effects of hepatocyte-specific deficiency of the NF-κB activator IKKβ (Maeda et al. 2005). Together, these data are consistent with the proposed role of compensatory proliferation in hepatic tumor development (Fausto 1999).

Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that JNK plays a complex role in the development of HCC. JNK is required for HCC development because it functions in nonparenchymal cells to cause expression of protumorigenic cytokines, including IL6 and TNFα. In contrast, JNK in hepatocytes reduces tumor development by decreasing hepatocyte death and compensatory proliferation. It is likely that previous studies using mice with whole-body knockout of Jnk1 or Jnk2 reflect a composite phenotype derived from the cell type-specific functions of JNK in hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells.

We conclude that JNK both promotes and inhibits tumor development in the DEN model of HCC. This conclusion has implications for the more general role of JNK in cancer. Both tumor promotion and inhibition by JNK may contribute to cancer development (Davis 2000; Whitmarsh and Davis 2007). This complicates the analysis of JNK pathway mutations that have been identified in human cancer (Greenman et al. 2007; Kan et al. 2010). Moreover, this dual role of JNK should be considered in the context of the potential use of JNK as a therapeutic target for drug development and the treatment of human cancer.

Materials and methods

Mice

We previously described Jnk1LoxP/LoxP mice (Das et al. 2009) and Jnk2−/− mice (Yang et al. 1998). B6.Cg-Tg(Alb-cre)21Mgn/J mice (Postic et al. 1999), B6.Cg-Tg(Mx1-cre)1Cgn/J mice (Kuhn et al. 1995), and C57BL/6J mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratories (stock numbers 003574, 003556, and 000664, respectively). The mutant mice were maintained on a C57BL/6J strain background (backcrossed 10 generations), and were housed in a facility accredited by the American Association for Laboratory Animal Care (AALAC). Deletion of floxed alleles in Mx1-Cre mice was performed by treatment of 4-wk-old mice with 20 μg/g polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (polyIC) (Mikkola et al. 2003) followed by recovery (4 wk). Control mice were similarly injected with polyIC. PHx was performed on 10-wk-old mice using methods described previously (Greene and Puder 2003). The animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Genotype analysis

Genotype analysis was performed by PCR using genomic DNA as the template. The Jnk1+ (540 base pairs [bp]) and Jnk1LoxP (330 bp) alleles were identified using the amplimers 5′-AGGATTTATGCCCTCTGCTTGTC-3′ and 5′-GAACCACTGTTCCAATTTCCATCC-3′. The Jnk1LoxP (1100 bp) and Jnk1Δ (400 bp) alleles were identified using the amplimers 5′-CCTCAGGAAGAAAGGGCTTATTTC-3′ and 5′-GAACCACTGTTCCAATTTCCATCC-3′. The Jnk2+ (400 bp) and Jnk2− (270 bp) alleles were identified using the amplimers 5′- GGAGCCCGATAGTATCGAGTTACC-3′, 5′-GTTAGACAATCCCAGAGGTTGTGTG-3′, and 5′-CCAGCTCATTCCTCCACTCATG-3′. Cre alleles (450 bp) were detected using the amplimers 5′-TTACTGACCGTACACCAAATTTGCCTGC-3′ and 5′- CCTGGCAGCGATCGCTATTTTCCATGAGTG-3′.

HCC assays

Carcinogen-induced HCC was studied using procedures described previously (Sakurai et al. 2008). Two-week-old male mice were treated by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection with a single dose (25 mg/kg) of DEN (Sigma, N0258) diluted in glyceryl trioctanoate (Sigma, T9126). Control mice were injected with solvent alone. The mice were euthanized at 38 wk of age to examine tumor development. Surface tumor size and number were measured using stereomicroscopy (Maeda et al. 2005). The Cre+/− genetic background altered the tumor burden in the DEN-induced HCC studies; more tumors were found in the Mx1-Cre+/− genetic background than in the Alb-Cre+/− genetic background (Figs. 2, 3). We therefore compared control Mx1-Cre+/− mice with JNK-deficient Mx1-Cre+/− mice or control Alb-Cre+/− mice with JNK-deficient Alb-Cre+/− mice.

Serum analysis

Alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotrasferase (AST) activity in serum was measured using the ALT and AST Reagent kit (Pointe Scientific) with a Tecan Sapphire microplate reader (Tecan Trading AG). The serum concentration of cytokines was measured by multiplexed ELISA using a Luminex 200 instrument (Millipore).

Biochemical analysis

Immunoblot analysis was performed by probing with antibodies to activated Caspase 3 (Cell Signaling, #9661) Sprouty2 (Abcam, #ab50317), PTEN (Cell Signaling, #9198), p21 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, #SC 6246), and α-Tubulin (Sigma, #T5168). Immunoblots were quantitated using a LiCOR Odyssey imager. The amount of total and phospho-JNK, ERK, p38 MAPK, and AKT in tissue extracts was measured using a multiplexed ELISA kit (Bio-Rad) and a Luminex 200 instrument (Millipore).

Quantitative RT–PCR assays (TaqMan) of mRNA expression were performed using a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems) with total RNA prepared from tissues with an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). The probes were cFos (Mm00487425_m1), cJun (Mm 00495062_s1), cMyc (Mm00487804_m1), Cyclin D1 (Mm00432359_m1), Il1a (00439621_m1), Il1b (Mm00434228_m1), Il6 (Mm00446190_m1), JunB (Mm00492781_s1), JunD (Mm 00495088_s1), p15 (Mm00483241_m1), p21 (Mm 00432448_m1), Pten (Mm01212532_m1), Socs3 (Mm00545913_s1), Spr2 (Mm00442344_m1), Tgfβ1 (Mm03024053_m1), and Tnf (Mm00443258_m1) (Applied Biosystems). The relative mRNA expression was normalized by measuring the amount of Gapdh RNA in each sample using TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems, 4352339E-0904021).

We prepared RNA from tissue samples using the mirVana microRNA isolation kit (Ambion) for the analysis of miR-21 expression using TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems, miR-21 RT 2493). The relative miR-21 expression was normalized by measuring the amount of U6 RNA in each sample using TaqMan assays (Applied Biosystems,U6 RT1973).

Analysis of liver sections

Histology was performed using tissue fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Sections (7 μm) were cut and stained using hematoxylin and eosin (American Master Tech Scientific). Terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining of deparafinized liver sections was performed using the In Situ Cell Death Detection kit Flourescein (Roche) following antigen retrieval (Antigen Unmasking Solution, Vector Laboratories). Immunofluorescence analysis of deparafinized liver sections was performed using antigen retrieval (Vector Laboratories); incubation (1 h) with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 1% normal goat serum, and 0.4% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS); incubation (12 h) at 4°C with a biotin-linked antibody to PCNA (Zymed Laboratories, 13-3940) in PBS with 3% BSA; and detection of immune complexes with Streptavidin-conjugated Alexa fluor 633 (Invitrogen, S 21375) in PBS with 3% BSA. The liver sections were mounted on glass slides. Nuclei were stained with DAPI using Vectashield (Vector Laboratories). Fluorescence microscopy was performed using a Leica SP2 confocal microscope.

The incorporation of BrdU was examined using liver sections prepared from mice injected (i.p.) with 100 μg/g BrdU (dissolved in saline) at 2 h prior to euthanasia. Livers were fixed in formalin, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm sections were prepared. Deparafinized liver sections were processed for antigen retrieval and incubated with an antibody to BrdU (Biogenex, #MU247-UC). Immune complexes were detected with a Streptavidin/Biotin-based Link-Label Detection kit (Biogenex, Supersensitive Link label immunohistochemistry detection system) and DAB substrate (Vector Laboratories, #SK4100).

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were examined for statistical significance using the Student's test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Fisher's test. Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed using the log-rank test.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tammy Barrett, Vicky Benoit, Linda Leehy, and Jian-Hua Liu for expert technical assistance, and Kathy Gemme for administrative assistance. These studies were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA65861 and AI046629). Core facilities at the University of Massachusetts used by these studies were supported by the NIDDK (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases) Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center (DK32520). R.J.D. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1989311.

Supplemental material is available for this article.

References

- Behrens A, Sibilia M, Wagner EF 1999. Amino-terminal phosphorylation of c-Jun regulates stress-induced apoptosis and cellular proliferation. Nat Genet 21: 326–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens A, Sibilia M, David JP, Mohle-Steinlein U, Tronche F, Schutz G, Wagner EF 2002. Impaired postnatal hepatocyte proliferation and liver regeneration in mice lacking c-jun in the liver. EMBO J 21: 1782–1790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgardt BF, Mauer J, Wunderlich FT, Ernst MB, Pal M, Spohn G, Bronneke HS, Brodesser S, Hampel B, Schauss AC, et al. 2010. Hypothalamic and pituitary c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 signaling coordinately regulates glucose metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 6028–6033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrita MA, Christofori G 2008. Sprouty proteins, masterminds of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Angiogenesis 11: 53–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CJ, Kono H, Golenbock D, Reed G, Akira S, Rock KL 2007. Identification of a key pathway required for the sterile inflammatory response triggered by dying cells. Nat Med 13: 851–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly E, Melegari M, Landgraf P, Tchaikovskaya T, Tennant BC, Slagle BL, Rogler LE, Zavolan M, Tuschl T, Rogler CE 2008. Elevated expression of the miR-17-92 polycistron and miR-21 in hepadnavirus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma contributes to the malignant phenotype. Am J Pathol 173: 856–864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cressman DE, Greenbaum LE, DeAngelis RA, Ciliberto G, Furth EE, Poli V, Taub R 1996. Liver failure and defective hepatocyte regeneration in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Science 274: 1379–1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M, Jiang F, Sluss HK, Zhang C, Shokat KM, Flavell RA, Davis RJ 2007. Suppression of p53-dependent senescence by the JNK signal transduction pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 15759–15764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M, Sabio G, Jiang F, Rincon M, Flavell RA, Davis RJ 2009. Induction of hepatitis by JNK-mediated expression of TNF-α. Cell 136: 249–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RJ 2000. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell 103: 239–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eferl R, Wagner EF 2003. AP-1: a double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 3: 859–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eferl R, Ricci R, Kenner L, Zenz R, David JP, Rath M, Wagner EF 2003. Liver tumor development. c-Jun antagonizes the proapoptotic activity of p53. Cell 112: 181–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausto N 1999. Mouse liver tumorigenesis: models, mechanisms, and relevance to human disease. Semin Liver Dis 19: 243–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AK, Puder M 2003. Partial hepatectomy in the mouse: technique and perioperative management. J Invest Surg 16: 99–102 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, Dalgliesh GL, Hunter C, Bignell G, Davies H, Teague J, Butler A, Stevens C, et al. 2007. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature 446: 153–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M 2010. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140: 883–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Jiang Y, Li Z, Kravchenko VV, Ulevitch RJ 1997. Activation of the transcription factor MEF2C by the MAP kinase p38 in inflammation. Nature 386: 296–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui L, Zatloukal K, Scheuch H, Stepniak E, Wagner EF 2008. Proliferation of human HCC cells and chemically induced mouse liver cancers requires JNK1-dependent p21 downregulation. J Clin Invest 118: 3943–3953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazbutyte V, Thum T 2010. MicroRNA-21: from cancer to cardiovascular disease. Curr Drug Targets 11: 926–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Gusev Y, Aderca I, Mettler TA, Nagorney DM, Brackett DJ, Roberts LR, Schmittgen TD 2008. Association of microRNA expression in hepatocellular carcinomas with hepatitis infection, cirrhosis, and patient survival. Clin Cancer Res 14: 419–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan Z, Jaiswal BS, Stinson J, Janakiraman V, Bhatt D, Stern HM, Yue P, Haverty PM, Bourgon R, Zheng J, et al. 2010. Diverse somatic mutation patterns and pathway alterations in human cancers. Nature 466: 869–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiba T 2002. The role of the autonomic nervous system in liver regeneration and apoptosis–recent developments. Digestion 66: 79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan CY, Yang DD, Samanta Roy DR, Davis RJ, Rakic P, Flavell RA 1999. The Jnk1 and Jnk2 protein kinases are required for regional specific apoptosis during early brain development. Neuron 22: 667–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn R, Schwenk F, Aguet M, Rajewsky K 1995. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science 269: 1427–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutay H, Bai S, Datta J, Motiwala T, Pogribny I, Frankel W, Jacob ST, Ghoshal K 2006. Downregulation of miR-122 in the rodent and human hepatocellular carcinomas. J Cell Biochem 99: 671–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb JA, Ventura JJ, Hess P, Flavell RA, Davis RJ 2003. JunD mediates survival signaling by the JNK signal transduction pathway. Mol Cell 11: 1479–1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffler D, Brocke-Heidrich K, Pfeifer G, Stocsits C, Hackermuller J, Kretzschmar AK, Burger R, Gramatzki M, Blumert C, Bauer K, et al. 2007. Interleukin-6 dependent survival of multiple myeloma cells involves the Stat3-mediated induction of microRNA-21 through a highly conserved enhancer. Blood 110: 1330–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S, Kamata H, Luo JL, Leffert H, Karin M 2005. IKKβ couples hepatocyte death to cytokine-driven compensatory proliferation that promotes chemical hepatocarcinogenesis. Cell 121: 977–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson KG, Contois LR, Tevosian SG, Davis RJ, Paulson KE 1996. Independent regulation of JNK/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases by metabolic oxidative stress in the liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci 93: 12908–12913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng F, Henson R, Wehbe-Janek H, Ghoshal K, Jacob ST, Patel T 2007. MicroRNA-21 regulates expression of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in human hepatocellular cancer. Gastroenterology 133: 647–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkola HK, Klintman J, Yang H, Hock H, Schlaeger TM, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH 2003. Haematopoietic stem cells retain long-term repopulating activity and multipotency in the absence of stem-cell leukaemia SCL/tal-1 gene. Nature 421: 547–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra L, Banker T, Murray J, Byers S, Thenappan A, He AR, Shetty K, Johnson L, Reddy EP 2009. Liver stem cells and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 49: 318–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naugler WE, Sakurai T, Kim S, Maeda S, Kim K, Elsharkawy AM, Karin M 2007. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science 317: 121–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EJ, Lee JH, Yu GY, He G, Ali SR, Holzer RG, Osterreicher CH, Takahashi H, Karin M 2010. Dietary and genetic obesity promote liver inflammation and tumorigenesis by enhancing IL-6 and TNF expression. Cell 140: 197–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postic C, Shiota M, Niswender KD, Jetton TL, Chen Y, Moates JM, Shelton KD, Lindner J, Cherrington AD, Magnuson MA 1999. Dual roles for glucokinase in glucose homeostasis as determined by liver and pancreatic β cell-specific gene knock-outs using Cre recombinase. J Biol Chem 274: 305–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raingeaud J, Gupta S, Rogers JS, Dickens M, Han J, Ulevitch RJ, Davis RJ 1995. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and environmental stress cause p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by dual phosphorylation on tyrosine and threonine. J Biol Chem 270: 7420–7426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabio G, Das M, Mora A, Zhang Z, Jun JY, Ko HJ, Barrett T, Kim JK, Davis RJ 2008. A stress signaling pathway in adipose tissue regulates hepatic insulin resistance. Science 322: 1539–1543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabio G, Cavanagh-Kyros J, Barrett T, Jung DY, Ko HJ, Ong H, Morel C, Mora A, Reilly J, Kim JK, et al. 2010. Role of the hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid axis in metabolic regulation by JNK1. Genes Dev 24: 256–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Maeda S, Chang L, Karin M 2006. Loss of hepatic NF-κ B activity enhances chemical hepatocarcinogenesis through sustained c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 10544–10551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, He G, Matsuzawa A, Yu GY, Maeda S, Hardiman G, Karin M 2008. Hepatocyte necrosis induced by oxidative stress and IL-1α release mediate carcinogen-induced compensatory proliferation and liver tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 14: 156–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber M, Kolbus A, Piu F, Szabowski A, Mohle-Steinlein U, Tian J, Karin M, Angel P, Wagner EF 1999. Control of cell cycle progression by c-Jun is p53 dependent. Genes Dev 13: 607–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe RF, Bradham CA, Uehara T, Hatano E, Bennett BL, Schoonhoven R, Brenner DA 2003. c-Jun-N-terminal kinase drives cyclin D1 expression and proliferation during liver regeneration. Hepatology 37: 824–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepniak E, Ricci R, Eferl R, Sumara G, Sumara I, Rath M, Hui L, Wagner EF 2006. c-Jun/AP-1 controls liver regeneration by repressing p53/p21 and p38 MAPK activity. Genes Dev 20: 2306–2314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournier C, Hess P, Yang DD, Xu J, Turner TK, Nimnual A, Bar-Sagi D, Jones SN, Flavell RA, Davis RJ 2000. Requirement of JNK for stress-induced activation of the cytochrome c-mediated death pathway. Science 288: 870–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura JJ, Kennedy NJ, Lamb JA, Flavell RA, Davis RJ 2003. c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase is essential for the regulation of AP-1 by tumor necrosis factor. Mol Cell Biol 23: 2871–2882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EF, Nebreda AR 2009. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 537–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westwick JK, Weitzel C, Leffert HL, Brenner DA 1995. Activation of Jun kinase is an early event in hepatic regeneration. J Clin Invest 95: 803–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ 2007. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 in cancer. Oncogene 26: 3172–3184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang DD, Conze D, Whitmarsh AJ, Barrett T, Davis RJ, Rincon M, Flavell RA 1998. Differentiation of CD4+ T cells to Th1 cells requires MAP kinase JNK2. Immunity 9: 575–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]