Abstract

Cerebral cortical γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic interneurons originate from the basal forebrain and migrate into the cortex in 2 phases. First, interneurons cross the boundary between the developing striatum and the cortex to migrate tangentially through the cortical primordium. Second, interneurons migrate radially to their correct neocortical layer position. A previous study demonstrated that mice in which the cortical hem was genetically ablated displayed a massive reduction of Cajal-Retzius (C-R) cells in the neocortical marginal zone (MZ), thereby losing C-R cell-generated reelin in the MZ. Surprisingly, pyramidal cell migration and subsequent layering were almost normal. In contrast, we find that the timing of migration of cortical GABAergic interneurons is abnormal in hem-ablated mice. Migrating interneurons both advance precociously along their tangential path and switch prematurely from tangential to radial migration to invade the cortical plate (CP). We propose that the cortical hem is responsible for establishing cues that control the timing of interneuron migration. In particular, we suggest that loss of a repellant signal from the medial neocortex, which is greatly decreased in size in hem-ablated mice, allows the early advance of interneurons and that reduction of another secreted molecule from C-R cells, the chemokine SDF-1/CXCL12, permits early radial migration into the CP.

Keywords: Cajal–Retzius cells, Cxcl12, Cxcr4, guidance cues

Introduction

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic interneurons regulate the balance of excitation and inhibition in the cerebral cortex and are therefore integral to the physiological processes of the forebrain (Gilbert and Wiesel 1985; Jones 1986; Freund 2003; Hensch 2005; Somogyi and Klausberger 2005; Woo and Lu 2006). As might be expected, altered GABAergic transmission has been reported in many human psychiatric and neurological disorders such schizophrenia, epilepsy, autism, and Alzheimer's disease (Young 1987; Fonseca et al. 1993; Keverne 1999; Cobos et al. 2005; Levitt 2005; Gant et al. 2009). Understanding the control of interneuron development has therefore received considerable recent attention (Fishell 2007; Butt et al. 2008; Marsh et al. 2008; Potter et al. 2009).

Cortical interneurons in the mouse originate from progenitor cells in the telencephalic ganglionic eminences (Anderson et al. 1997, 1999) and adopt the same cortical layer as pyramidal neurons born at the same time in the cortical ventricular zone (VZ) (Hevner et al. 2004). Thus, coordinating the timing of different stages of interneuron migration may be key to determining the final position of the interneurons and their functional integration into cortical circuitry (Hevner et al. 2004; Li et al. 2008; Lopez-Bendito et al. 2008).

Several factors have been identified as regulators of cortical interneuron migration (Marin and Rubenstein 2003; Huang 2009). To reach the cerebral cortex, cortical interneurons are directed toward the corticostriate boundary from the ganglionic eminences. Neuregulin proteins are chemoattractants in this early stage of migration. GABAergic cells born in the medial ganglionic eminence follow a corridor through the lateral ganglionic eminence (LGE) that expresses Neuregulin1 (Nrg1), which encodes the ligand of the tyrosine kinase receptor Erbb4 (Flames et al. 2004; Ghashghaei et al. 2006). Chemorepulsion additionally directs interneurons along this route, mediated by Neuropilin receptors (Nrp1, Nrp2), and activated by class-3 Semaphorins (Sema3a and Sema3f) in the striatal mantle zone (Marin et al. 2001).

Time-lapse videomicroscopy shows that the migratory behavior of interneurons in the cortical primordium is complex and dynamic (Ang et al. 2003; Li et al. 2008; Lopez-Bendito et al. 2008). We focus here, however, on a simplified model of interneuron movement: tangential migration in 2 streams through the marginal zone (MZ) and subventricular/intermediate zones (SVZ/IZ), followed by radial migration into the cortical plate (CP) (Huang 2009). Directly relevant to our study, invasion of the CP is delayed for both early- and late-born interneurons such that even early-born interneurons fail to enter the CP until after E15.5 (Lopez-Bendito et al. 2008).

Factors identified as regulators of tangential and radial interneuronal migration include the chemokine CXCL12, previously called SDF-1 (stromal cell derived factor-1), which is generated by meningeal cells overlying the cortex, Cajal–Retzius (C-R) cells in the MZ, and pyramidal cell precursors along the SVZ/IZ migratory route (Daniel et al. 2005; Tiveron et al. 2006). CXCL12 in the MZ and SVZ/IZ provides interneurons with 2 “most permissive” routes through the cortical primordium (Borrell and Marin 2006; Lopez-Bendito et al. 2008). In mice deficient in the chemokine CXCL12, or its receptor CXCR4, interneurons alter their tangential migratory routes. When CXCL12 is disrupted in the SVZ/IZ, the cells switch their migration to the MZ route. If CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling is abolished, interneurons migrate broadly throughout the thickness of the cortical primordium and enter the CP prematurely (Stumm et al. 2003; Tiveron et al. 2006; Lopez-Bendito et al. 2008; Zhao et al. 2008). Thus, CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling not only directs interneurons along their 2 major tangential migration routes but also controls the timing of their exit from these routes into the CP (Li et al. 2008).

Other factors responsible for timing interneuron migration into the cortex have been demonstrated but not yet identified at the molecular level (Britto et al. 2006). Cell behavior in cortical slice cultures reveals that explants of the medial cortical primordium inhibit tangential migration of interneurons at early stages of corticogenesis. Subsequently, medial cortex becomes a permissive substrate for interneurons. Medially located cues therefore regulate the advance of interneurons from lateral to medial in the cortical primordium (Britto et al. 2006).

In a previous study, mice were engineered to lack a cortical signaling center, the cortical hem, by introducing the diphtheria toxin subunit A (dt-a) into the hem by Cre-lox recombination (Yoshida et al. 2006). Hem-ablated mice showed a massive loss of reelin-expressing C-R cells, demonstrating that the hem is the source of a major population of neocortical C-R cells (Yoshida et al. 2006). Given the production of reelin by C-R cells (D'Arcangelo et al. 1995; Ogawa et al. 1995; Meyer et al. 1999; Derer et al. 2001), and previous reports of neocortical layering defects in the reeler mutant mouse, which lacks reelin, and other mutants with defects in reelin signaling (Caviness 1982a, 1982b; Howell et al. 1997; Sheldon et al. 1997; Trommsdorff et al. 1999; Hammond et al. 2006), a perturbed neocortical layer distribution was expected in hem-ablated neocortex. Contrary to expectation, the laminar pattern was near normal. The sheet of C-R cells that covers the neocortical primordium therefore appears not to be required to direct the radial migration and laminar distribution of neocortical pyramidal neurons (Yoshida et al. 2006).

In the present study, we investigated the effect of cortical hem loss on interneuron migration, taking advantage of the previously generated mouse line (Yoshida et al. 2006). In contrast to the lack of major effects on pyramidal cells, we found prominent defects in the timing of interneuron migration in hem-ablated mice. Both the tangential advance of interneurons into the cortical primordium and the subsequent shift to a radial mode of migration were premature in hem-ablated mice compared with control mice. We therefore investigated the progression of interneuron migration in hem-ablated mice to determine which stages, and likely guidance mechanisms, were affected by loss of the hem.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Lines

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Chicago approved all protocols, and mice were used according to National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines. Generation of hem-ablated mice has been previously described (Yoshida et al. 2006). Briefly, a cassette carrying an internal ribosome entry site (IRES), followed by stop codons flanked by loxP sites, followed by a cDNA encoding the diphtheria toxin subunit A (dt-a) (Lee et al. 2000), was inserted into the 3′ end of the Wnt3a locus, using standard embryonic stem cell technology (Yoshida et al. 2006). In mice carrying this mutant Wnt3a allele, activation of the toxin was prevented by the stop codons preceding dt-a (Lee et al. 2000). Dt-a was activated in the hem by crossing mice carrying the Wnt3a-IRESxneox-dt-a allele with an Emx1-IRES-Cre mouse line (Gorski et al. 2002). In cells that coexpressed Emx1 and Wnt3a dt-a was activated, killing the cells. In the telencephalon, such cells were confined to the cortical hem. Mice-termed controls have the Wnt3a IRESxneoxdt-a/+; Emx1+/+ genotype and show an entirely normal hem. Mice with the Wnt3aIRESxneoxdt-a/+; Emx1IRESCre/+ genotype are referred as hem-ablated mice and die shortly after birth, apparently due to a jaw defect that prevents normal feeding. Hem-ablated mice were compared with littermate controls.

Tissue Processing

Brains were collected from embryos aged E12.5–E17.5 and fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed brains were embedded in 30% sucrose, 10% gelatin in phosphate-buffered saline, and sectioned coronally or sagittally with a Leica SM2000R microtome. Sections were processed for in situ hybridization (ISH) with digoxigenin (Dig)-labeled riboprobes (Yoshida et al. 2006). Sections were first permeabilized by treatment with proteinase K (1 μg/mL) for 20 min. After posthybridization washes, bound Dig was detected with anti-Dig antibody (Roche). Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed on coronal and sagittal brain sections with fluorescein isothiocynate (FITC)-labeled riboprobes. After posthybridization washes, bound FITC was detected with a peroxidase-conjugated anti-FITC antibody (Perkin Elmer) and incubation with the peroxidase substrate FITC-tyramide (Roche). For double FISH, following inactivation at 70 °C, the second probe was localized with a peroxidase-conjugated anti-Dig antibody and Cy5-tyramide (Roche). At least 3 mutant and 3 control embryos were analyzed for expression of each gene at each age described in Results.

Quantification

At least 6 sections from 3 brains from each genotype were used for quantitative analysis of tangential migration of Lhx6-expressing interneurons. Lhx6 is expressed in the vast majority of cortical interneurons (Cobos et al. 2006). Sections were imaged using an Axioscope with an Axiocam camera and software (Zeiss); contrast and brightness were adjusted with Adobe Photoshop CS4. The tangential distance traveled by interneurons from their entry point into the cortex at the corticostriate boundary to their migration front at a given age was measured using ImageJ software (series 1.4, NIH, public domain). The mean distance traveled through the cortical primordium was compared between control and hem-ablated brains at E12.5 and E13.5. Statistical significance was determined with the t-test (Microsoft Excel).

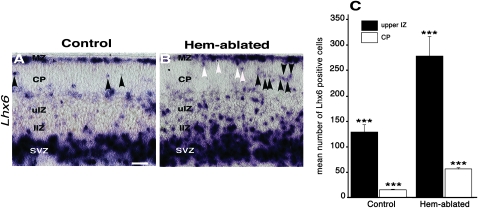

To compare the number of Lhx6 interneurons occupying the CP and the upper intermediate zone (uIZ) at E15.5 in hem-ablated and control brains, sagittal sections were processed with ISH for Lhx6. Four sections, evenly spaced through one hemisphere, were analyzed from each of 3 control and 3 hem-ablated brains, and a field of the cortical primordium, 1 mm wide, was selected from each section at the same dorsoventral level for cell counting. In each imaged field, upper and lower boundaries were drawn for the CP (Adobe Photoshop, CS4), which was visible at E15.5 as a densely packed cell layer, and for a band of equal width to the CP, immediately beneath, containing the uIZ. Cells were counted separately in the CP and uIZ bands. Total cell counts for the CP and uIZ in all sections from each brain were compared between control and hem-ablated cortices. The difference in cell number in the CP and uIZ between the 2 groups was evaluated with a one-tailed t-test (Microsoft Excel).

Results

Genetic Ablation of the Cortical Hem Results in Aberrant Tangential Migration of Gabaergic Neurons

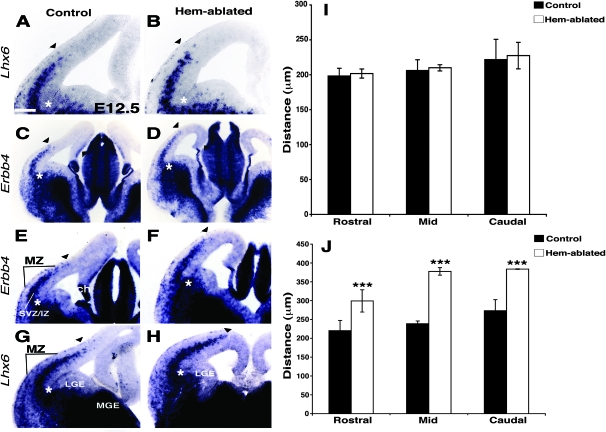

To test for differences in the migration of interneurons between hem-ablated and control brains, interneurons were identified by expression of Lhx6 and Erbb4 (Yau et al. 2003; Alifragis et al. 2004; Zhao et al. 2008), and tangential migration was assessed at 2 embryonic stages. In both hem-ablated mice and controls, interneurons migrated along a superficial stream in the MZ and a deeper and more populated stream in the SVZ/IZ (Ang et al. 2003; Tanaka et al. 2006; Huang 2009). At E12.5, there was no significant difference in the extent of tangential migration between hem-ablated mice and controls (Fig. 1A,B,I). At E13.5, however, in both migratory streams, Lhx6- and Erbb4-expressing interneurons extended further dorsally in the mutants than in controls (Fig. 1C–H,J).

Figure 1.

Genetic ablation of the hem results in premature tangential migration of interneurons into cortex. (A-H) Coronal sections through E12.5 (A-B) and E13.5 (C,H) brains, processed with ISH for the genes indicated. Arrowheads mark the extent of interneuron tangential migration into the cortical primordium through the SVZ/IZ and the MZ. (I,J) Distance traveled from the corticostriate boundary in mutants and controls at E12.5 (I) and E13.5 (J). Asterisks (A-H) indicate the corticostriate boundary, the point of entry into cortex. (C-F) Low (C,D) and higher (E,F) magnification of Erbb4-expressing interneurons. The SVZ/IZ stream of interneurons extends further dorsally into the cortical primordium in hem-ablated compared with control brains (C-F). Higher magnification shows a similar difference in the MZ migratory stream (E,F). (G,H) Lhx6-expressing interneurons also extend further in hem-ablated than control cortices. (I,J) At E13.5 (J), but not at E12.5 (I), the migration front of Lhx6-expressing interneurons in the SVZ/IZ has reached significantly further into the cortical primordium in the mutant compared with the control at rostral, mid, and caudal levels in the brain. Distance traveled by Lhx6-expressing interneurons from the corticostriate boundary in microns is expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. Three asterisks represent P < 0.005. Abbreviations: ch, cortical hem; SVZ/IZ; MZ; MGE, medial ganglionic eminence; LGE, lateral ganglionic eminence. Scale bar, 100 μm (A,B, and E-H), 250 μm (C,D).

The maximum dorsal extension of Lhx6-expressing interneurons along the SVZ/IZ route was quantified by measuring the distance of the migration front from the corticostriate boundary at rostral, mid, and caudal levels of the cortex. At E13.5, Lhx6-positive interneurons had migrated significantly further into the cortical primordium in hem-ablated mice compared with controls at all 3 levels (Fig. 1J). These observations indicate that interneurons advance prematurely through hem-ablated cortex.

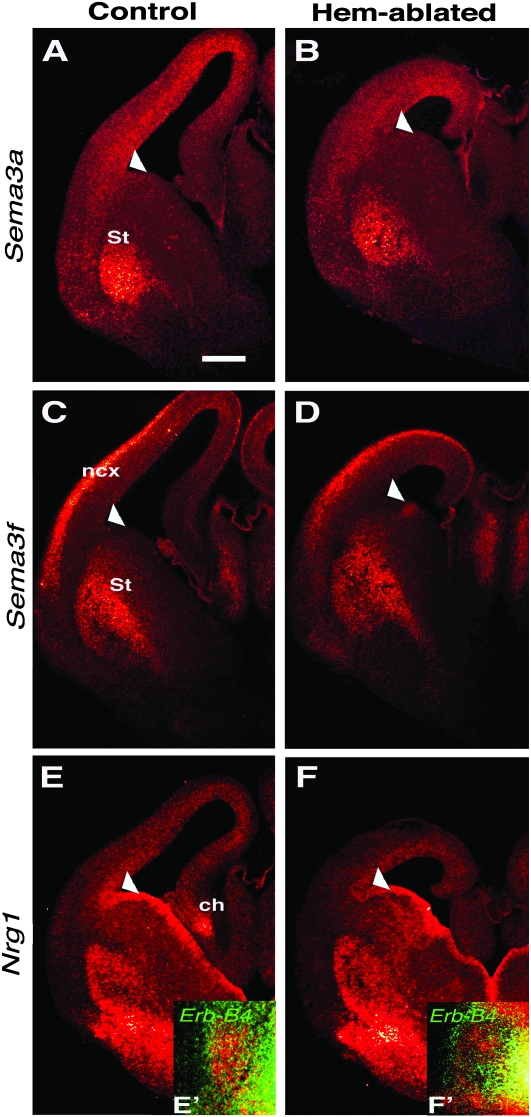

Subcortical Cues Regulating Interneuron Migration Are Unaffected

To determine the possible causes of early interneuron invasion of the cortical primordium, we first tested whether loss of the hem affects selected guidance cues in the developing striatum, through which the interneurons migrate, or disrupts the corticostriate boundary, or “anti-hem” (Assimacopoulos et al. 2003), which interneurons cross to enter the cortical primordium. Because the cortical hem is a dorsal telencephalic organizer, its loss could affect development throughout the dorsoventral axis of the telencephalon, including the anti-hem and ventral telencephalon. We found no obvious defects, however, in the expression of major interneuron guidance molecules in the ventral telencephalon (Corbin et al. 2001; Tanaka et al. 2003). At E13.5, no differences were observed between control and hem-ablated mice in the expression patterns of genes encoding Semaphorin3a (Sema3a) and Semaphorin3f (Sema3f) (Fig. 2A–D), which create an inhibitory territory for migrating interneurons (Marin et al. 2001; Tamamaki et al. 2003). Similarly, no differences were seen in the expression of the gene encoding Nrg1 (Fig. 2E,F), which guides Erbb4-expressing interneurons through the LGE (Flames et al. 2004; Ghashghaei et al. 2006), or in the position of Erbb4-expressing interneurons, relative to domains of Nrg1 (Fig. 2E′,F'). Furthermore, Sema3a, Sema3f, and Nrg1 were expressed similarly in the cortical primordium of mutant and control mice (Fig. 2A–F).

Figure 2.

Distribution of major subpallial guidance cues for interneurons is similar in control and hem-ablated brains. (A-F) Coronal sections of E13.5 brains, processed with FISH for class III Semaphorins (Sema3a and Sema3f) (A-D) and Neuregulin1 (Nrg1) (E,F). Arrowheads in (A-F) mark the corticostriate boundary as a landmark for evaluating gene expression patterns. (A-F) Expression patterns of Sema3a, Sema3f, and Nrg1 appear highly similar between control and hem-ablated mice in the developing striatum (St) and neocortex (ncx). An exception is the cortical hem (ch) in which Nrg1 is strongly expressed in the control (E) but absent, as expected, in the hem-ablated mouse (F). Double FISH for Erb-B4 (green), marking interneurons, and Nrg1 (red) (E',F'). Scale bar, 250 μm (A-F).

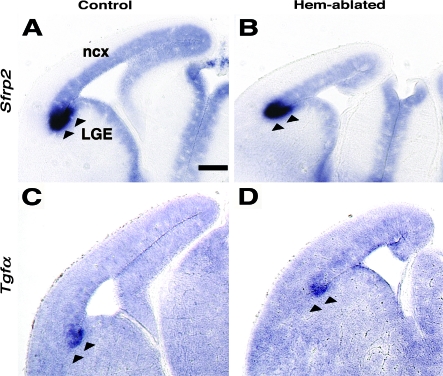

The corticostriate boundary, or “anti-hem” (Assimacopoulos et al. 2003), produces several secreted signaling molecules, including FGF7, sFrp2, and TGFα, and is marked by boundaries of Dlx2, Emx2, Ascl1, and Gsx2 expression (Assimacopoulos et al. 2003; Backman et al. 2005; Long et al. 2009). Defects in the position of the anti-hem, or its production of signaling molecules, could well affect interneuron migration across the region. Indeed, defective positioning of the corticostriate boundary in the small-eye mutant causes an apparently excessive migration of interneurons into the cortical primordium (Gopal and Golden 2008). We saw no differences between control and hem-ablated brains, however, in the pattern or density of expression of Sfrp2, Tgfα (Fig. 3A–D), Fgf7, Ascl1, and Gsx2 (data not shown), indicating that the anti-hem was normally positioned in hem-ablated mice and that anti-hem signaling was unaffected. Defects at the anti-hem are therefore unlikely to be responsible for the premature advance of interneurons into the cortical primordium.

Figure 3.

Corticostriate boundary is properly positioned in hem-ablated mice. (A-D) Coronal sections of E13.5 brains, processed with ISH for Sfrp2 and Tgfα. Arrowheads mark the position of the corticostriate boundary, or “anti-hem,” which appears similarly positioned between the lateral ganglionic eminence and cortical primordium in control and hem-ablated brains. Anti-hem expression of Sfrp2 and Tgfα appears equivalently strong in both brains. Abbreviations: ncx, neocortex; LGE, lateral ganglionic eminence. Scale bar, 230 μm (A-D).

In the cortical primordium, the chemokine CXCL12, produced by pyramidal neuron progenitor cells, provides a permissive substrate in the SVZ/IZ along which interneurons migrate (Tiveron et al. 2006). Similarly, CXCL12 produced by the meninges directs tangential interneuron migration in the neighboring MZ (Tiveron et al. 2006). At E13.5, Cxcl12 was expressed at equivalent levels in the SVZ/IZ and meninges in hem-ablated mice ((see Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating that a major chemoattractant along the 2 tangential migratory routes was unaffected, at this age, by loss of the hem.

Medial Cortex Controls Timing of Tangential Interneuron Migration and Is Reduced by Hem Loss

Previous slice culture experiments demonstrated that overlaying a cortical slice with a medial cortical explant inhibits interneuron migration at E12.5 (Britto et al. 2006) but that medial cortex becomes permissive for migration about a day later (Britto et al. 2006). The correspondence between the active period of this inhibitory cue and the timing of the premature advance of interneurons in hem-ablated cortex led us to examine whether medial neocortex is reduced in the hem-ablated brain.

Cre-mediated recombination directed by the Emx1-IRES-Cre mouse begins at E9.5 (Gorski et al. 2002). By E10, the cortical hem in Wnt3aIRESxneoxdt-a/+; Emx1IRESCre/+ mice was almost completely ablated, evident by the loss of characteristic hem expression of Wnt3a and Lmx1a as well as tissue loss (Yoshida et al. 2006). By E12.5, gene expression that identifies the hippocampal primordium was missing, and, at E18.5, gene expression markers of the hippocampal formation from the dentate gyrus to the subiculum were absent (Yoshida M, Grove EA, unpublished data). Loss of the hippocampus would be predicted given that loss of a single signaling molecule, Wnt3a, from the hem prevents hippocampal development (Lee et al. 2000).

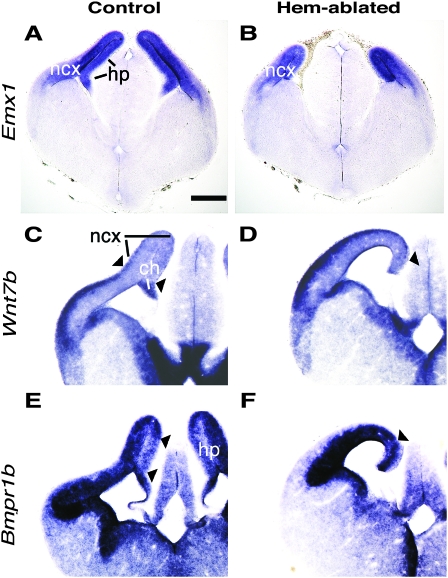

In addition to loss of the hippocampus, we observed a large reduction in the primordium of medial neocortex in hem-ablated brains. At E13.5, the hippocampal and neocortex primordia express Emx1, an ortholog of Drosophila empty spiracles. The domain of Emx1 expression in hem-ablated cortex at E13.5 was much smaller than expected from the loss of the hippocampus alone (Fig. 4A,B), suggesting additional reduction of medial neocortex. In control mice at E13.5, Wnt7b is strongly expressed in the lateral neocortical primordium but relatively weakly expressed in the medial neocortical and hippocampal primordia (Fig. 4C). In hem-ablated mice, strong Wnt7b expression continued to the far medial edge of the cortical primordium and the medial region of weak expression was virtually absent (Fig. 4D). The hippocampal primordium at E13.5 is further distinguished from the rest of the cortical primordium by comparatively weak expression of Bmpr1b encoding a type I bone morphogenetic protein receptor (Fig. 4E, arrowheads). As expected, this region was missing in the hem-ablated brain (Fig. 4F). The phenotype of a reduced medial neocortical primordium was observed in all mutant brains analyzed (n > 30). Future analysis will determine which areas are missing or reduced and the percentage of cortical tissue loss in hem-ablated brains.

Figure 4.

Ablation of the hem results in a reduction of medial cortex. (A-F) Coronal sections of E13.5 brains, processed with ISH for the genes indicated. (A,B) Emx1 expression fills the neocortical and hippocampal primordia in a control brain (A). The hem-ablated brain (B) has no hippocampus, but the cortical primordium is reduced in length more than is accounted for hippocampal loss (C,D). Arrowheads mark the relatively Wnt7b-poor medial portion of the neocortical primordium (lines in C). This region is virtually absent in the hem-ablated mouse (D, arrowhead). (E,F) The expression pattern of Bmpr1b distinguishes the hippocampal primordium as a more lightly stained territory than the rest of the cortex (E). This domain is missing as expected in the mutant (F). Abbreviations: ncx, neocortex; hp, hippocampal primordium; ch, cortical hem. Scale bar, 250 μm (A-F).

Our observations support the hypothesis that inhibitory activity in medial neocortex transiently prevents tangential migration of interneurons (Britto et al. 2006), suggesting that when inhibitory medial cortex is reduced in hem-ablated mice, interneurons are free to advance prematurely toward the dorsomedial edge of the cortical primordium.

Loss Of Cxcl12-Expressing Cajal–Retzius Cells in Hem-Ablated Mice Is Associated With Early Interneuron Invasion of the CP

To integrate into the developing CP, tangentially migrating GABAergic cells switch their mode of migration from tangential to radial, invading the CP from the MZ and SVZ/IZ migratory streams in a temporally regulated manner (Li et al. 2008; Lopez-Bendito et al. 2008; Zimmer et al. 2008). In wild-type mice, interneurons invade the CP after E15.5 (Li et al. 2008; Lopez-Bendito et al. 2008). In hem-ablated mice, however, interneurons entered the CP prematurely.

At E15.5, as expected, most Lhx6-expressing interneurons in control cortex were in the MZ and SVZ/IZ, with few labeled cells in the upper IZ and almost none in the CP (Fig. 5A). In hem-ablated cortex, by contrast, many more interneurons appeared in the CP and in the upper IZ. In total, the CP in hem-ablated cortex contained about 4 times as many Lhx6-expressing interneurons as the CP in control cortex (Fig. 5C). The greater number of interneurons invading the CP in the mutant is unlikely to result from a generally larger number of interneurons that have migrated into the cortical primordium. First, an active mechanism is believed to be required for interneurons to enter the CP (Li et al. 2008; Lopez-Bendito et al. 2008). Second, the total number of interneurons invading the entire cortical primordium is not 4 times greater in the hem-ablated mice than in controls (Figs 1, 5,6).

Figure 5.

Radial migration of interneurons in hem-ablated cortex. (A-B) E15.5 coronal sections processed with ISH to label Lhx6-expressing interneurons. Labeled cells are more abundant in the CP of the hem-ablated brain (A,B, arrowheads) as well as the uIZ. White arrowheads indicate cells apparently detaching from the marginal zone (MZ). (C) The number of interneurons occupying the CP and the uIZ was significantly higher in hem-ablated mice than in control brains. Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. *** indicates P < 0.005. Abbreviations: SVZ, subventricular zone; lIZ, lower intermediate zone. Scale bar, 100 μm (A,B).

Figure 6.

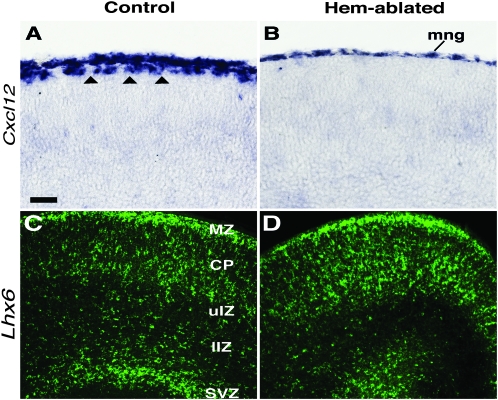

Premature radial migration correlates with loss of Cxcl12-positive C-R cells. (A,B) Coronal sections of E17.5 brains processed with ISH for Cxcl12. Arrowheads in (A) mark Cxcl12-expressing C-R cells in the MZ of the dorsal neocortical primordium, which are missing from the same region of hem-ablated cortex (B). (C-D) Lhx6-expressing interneurons are more profuse in the CP and uIZ of hem-ablated brains compared with controls, whereas fewer interneurons appear in the lower intermediate zone (lIZ) and SVZ/IZ of the mutant. Abbreviation: mng, meninges. Scale bar, 50 μm (A,B), 100 μm (C,D).

The effects of precocious invasion of the CP were also evident later in corticogenesis. At E17.5, Lhx6-expressing interneurons appeared in the upper IZ and CP of control brains (Fig. 6C) but were substantially more profuse in the CP of hem-ablated brains. Conversely, there were markedly fewer Lhx6-expressing cells in the lower IZ and SVZ of hem-ablated cortex compared with control brains, suggesting that cells had left the SVZ/IZ migratory stream in greater numbers in the mutants than in controls (Fig. 6C,D).

Previous reports indicate that disruption or loss of CXCL12/CXCR4 chemokine signaling causes aberrant migration by interneurons, including a premature entry into the CP (Stumm et al. 2003; Tiveron et al. 2006; Li et al. 2008; Lopez-Bendito et al. 2008). In control mice at the earliest stages of corticogenesis, Cxcl12 expression near the MZ is confined to the meninges overlying the brain (Supplementary Fig. 1). C-R cells in the MZ begin to express Cxcl12 at about E14.5 (Daniel et al. 2005; Lopez-Bendito et al. 2008). At later embryonic stages, therefore, both the meninges and C-R cells produce CXCL12 near the cortical pial surface (Fig. 6A). Meanwhile, by E16.5, the SVZ/IZ source of CXCL12 declines in both control and mutant mice. Thus, at later stages of corticogenesis, C-R cells contribute substantially to available CXCL12. Consequently, as a result of the massive loss of C-R cells in hem-ablated brains, CXCL12 is considerably reduced (Fig. 6A,B). Furthermore, the timing of the reduction of CXCL12 correlates well with the timing of precocious interneuron migration into the CP in hem-ablated mice. Our findings therefore suggest that reduced CXCL12 accounts for the premature migration of interneurons into the CP of hem-ablated brains.

Discussion

A previous study indicated that secretion of reelin by a dense layer of C-R cells is not required for near-normal pyramidal cell lamination (Yoshida et al. 2006). A low level of reelin from residual C-R cells and from sources outside the cortical MZ is sufficient for migration and layer targeting (Yoshida et al. 2006). Whether interneurons respond to reelin from C-R cells remains unclear. In mice lacking all reelin, or the reelin receptor adaptor protein Disabled1 (Dab1), interneuron layering is perturbed (Hevner et al. 2004; Pla et al. 2006; Yabut et al. 2007), but the distribution of pyramidal neurons and interneurons remains coupled, suggesting interneurons respond to cues from pyramidal cells already in place or that reelin affects interneurons and pyramidal neurons in a correlated manner (Hevner et al. 2004; Pla et al. 2006; Yabut et al. 2007). Thus, we might expect the reduction of C-R cell–produced reelin in hem-ablated brains to have little effect on interneuron migration.

C-R cells produce another secreted ligand, CXCL12, however, which has been demonstrated to regulate the migration of interneurons in the cerebral cortex (Stumm et al. 2003; Berger et al. 2007; Li et al. 2008; Lopez-Bendito et al. 2008). In mice lacking a hem, CXCL12 is substantially reduced in the neocortical primordium by the loss of C-R cells. We found that interneurons behave very similarly in hem-ablated mice and mice in which Cxcl12 or Cxcr4 are genetically deleted, namely interneurons populate the CP prematurely (Stumm et al. 2003; Li et al. 2008; Lopez-Bendito et al. 2008).

Only time-lapse video microscopy would allow us to identify unequivocally whether one or both interneuron migratory streams invade the CP prematurely in the absence of the hem. Meanwhile, some observations suggest that interneurons migrate into the CP precociously from both streams. At E15.5, cells were seen apparently detaching from the MZ to enter the CP. Moreover, a large excess of interneurons was present in the upper IZ, presumably heading for the CP from the SVZ/IZ (Fig. 5). By E17.5, both the IZ and SVZ were more depleted of interneurons in the mutant cortex compared with controls (Fig. 6), suggesting an early clearance of the SVZ/IZ pathway in the mutant.

The mechanism of CXCL12 control of interneuron migration is not yet known, but in 2 models, CXCL12 activity maintains interneurons in tangential migration and must be suppressed to allow the cell to escape and integrate into the CP. One proposal is that CXCL12 is initially a chemoattractant for local interneurons but that later in corticogenesis, interneurons lose their responsiveness to CXCL12 and are free to migrate radially into the CP (Li et al. 2008), which contains a chemoattractant for interneurons (Lopez-Bendito et al. 2008). In a second proposal, CXCL12 influences the exploratory behavior of interneurons as they migrate (Lysko and Golden 2009). In the first model, a reduction of CXCL in the MZ, such as occurs in hem-ablated mice, might be expected to affect primarily local interneurons migrating through the MZ. In the second model, loss of CXCL12 in the MZ could affect interneurons anywhere in its range of diffusion, a model that is perhaps more consistent with our findings.

The migration of interneurons in hem-ablated mice shows an additional abnormality, not seen in mice deficient in Cxcl12/Cxcr4 signaling or any other mutant mouse of which we are aware. At E12.5, interneurons have crossed into the cortical primordium in both mutants and controls, and the position of the migratory front is not significantly different between the 2 groups. By contrast, at E13.5, the migratory front is significantly more advanced dorsomedially in hem-ablated mice compared with controls. This implies that the initial crossing of interneurons into the cortical primordium is relatively normal in hem-ablated cortex but that subsequent progress is increased.

A previous study supports the hypothesis that differential promotion and inhibition of interneuron migration in the lateral and medial cortical primordium plays a key role in the timing of tangential interneuron migration (Britto et al. 2006). Our findings provide further support for this idea. After genetic deletion of the hem, the lateral cortical primordium appears intact, and in keeping with previous observations that the lateral cortex at E12.5 is an attractive substrate for interneurons (Britto et al. 2006), we saw no difference between hem-ablated and control mice at E12.5 in interneuron migration into lateral cortex. Between E12.5 and E13.5, medial cortex produces a cue that is transiently inhibitory to interneurons in slice culture (Britto et al. 2006). A reduction of medial cortex, as is observed in hem-ablated brains, could therefore allow interneurons to invade further into the cortical primordium by E13.5.

In conclusion, we identified premature tangential and radial interneuron migration in hem-ablated mice. Final layer position of the interneurons born at different ages could not be determined directly because the hem-ablated mice die at birth. However, the early entry of interneurons into the CP suggests, at least, that they were unlikely to arrive in the same layer at the same time as pyramidal cells born at the same age, potentially disrupting interneuron integration into cortical circuitry (Hevner et al. 2004; Li et al. 2008; Lopez-Bendito et al. 2008). Strikingly, the cortical hem, a structure that is distant from both the source and entry point of cortical interneurons, nonetheless regulates their migration. Specifically, the hem establishes cell types and tissues that in turn provide cues directing the timing of both tangential and radial interneuron migration.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material can be found at: http://www.cercor.oxfordjournals.org/.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (R37 H059962 to E.A.G.).

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Alifragis P, Liapi A, Parnavelas JG. Lhx6 regulates the migration of cortical interneurons from the ventral telencephalon but does not specify their GABA phenotype. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5643–5648. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1245-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S, Eisenstat D, Shi L, Rubenstein JL. Interneuron migration from basal forebrain to neocortex: dependence on Dlx genes. Science. 1997;278:474–476. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S, Mione M, Yun K, Rubenstein JL. Differential origins of neocortical projection and local circuit neurons: role of Dlx genes in neocortical interneuronogenesis. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:646–654. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.6.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang ES, Jr, Haydar TF, Gluncic V, Rakic P. Four-dimensional migratory coordinates of GABAergic interneurons in the developing mouse cortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5805–5815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05805.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assimacopoulos S, Grove EA, Ragsdale CW. Identification of a Pax6-dependent epidermal growth factor family signaling source at the lateral edge of the embryonic cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6399–6403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-16-06399.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backman M, Machon O, Mygland L, van den Bout CJ, Zhong W, Taketo MM, Krauss S. Effects of canonical Wnt signaling on dorso-ventral specification of the mouse telencephalon. Develop Biol. 2005;279:155–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger O, Li G, Han SM, Paredes M, Pleasure SJ. Expression of SDF-1 and CXCR4 during reorganization of the postnatal dentate gyrus. Develop Neurosci. 2007;29:48–58. doi: 10.1159/000096210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrell V, Marin O. Meninges control tangential migration of hem-derived Cajal–Retzius cells via CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1284–1293. doi: 10.1038/nn1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto JM, Obata K, Yanagawa Y, Tan SS. Migratory response of interneurons to different regions of the developing neocortex. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16(1 Suppl):i57–i63. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt SJ, Sousa VH, Fuccillo MV, Hjerling-Leffler J, Miyoshi G, Kimura S, Fishell G. The requirement of Nkx2-1 in the temporal specification of cortical interneuron subtypes. Neuron. 2008;59:722–732. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caviness VS., Jr Development of neocortical afferent systems: studies in the reeler mouse. Neurosci Res Program Bull. 1982a;20:560–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caviness VS., Jr Neocortical histogenesis in normal and reeler mice: a developmental study based upon [3H]thymidine autoradiography. Brain Res. 1982b;256:293–302. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(82)90141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos I, Calcagnotto ME, Vilaythong AJ, Thwin MT, Noebels JL, Baraban SC, Rubenstein JL. Mice lacking Dlx1 show subtype-specific loss of interneurons, reduced inhibition and epilepsy. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1059–1068. doi: 10.1038/nn1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobos I, Long JE, Thwin MT, Rubenstein JL. Cellular patterns of transcription factor expression in developing cortical interneurons. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16(Suppl 1):i82–i88. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhk003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin JG, Nery S, Fishell G. Telencephalic cells take a tangent: non-radial migration in the mammalian forebrain. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(Suppl):1177–1182. doi: 10.1038/nn749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Arcangelo G, Miao GG, Chen SC, Soares HD, Morgan JI, Curran T. A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature. 1995;374:719–723. doi: 10.1038/374719a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel D, Rossel M, Seki T, Konig N. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) expression in embryonic mouse cerebral cortex starts in the intermediate zone close to the pallial-subpallial boundary and extends progressively towards the cortical hem. Gene Expr Patterns. 2005;5:317–322. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derer P, Derer M, Goffinet A. Axonal secretion of Reelin by Cajal–Retzius cells: evidence from comparison of normal and Reln(Orl) mutant mice. J Comp Neurol. 2001;440:136–143. doi: 10.1002/cne.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishell G. Perspectives on the developmental origins of cortical interneuron diversity. Novartis Found Symp. 2007;288:21–35. ; discussion 35–44, 96–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flames N, Long JE, Garratt AN, Fischer TM, Gassmann M, Birchmeier C, Lai C, Rubenstein JL, Marin O. Short- and long-range attraction of cortical GABAergic interneurons by neuregulin-1. Neuron. 2004;44:251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca M, Soriano E, Ferrer I, Martinez A, Tunon T. Chandelier cell axons identified by parvalbumin-immunoreactivity in the normal human temporal cortex and in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience. 1993;55:1107–1116. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF. Interneuron diversity series: rhythm and mood in perisomatic inhibition. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:489–495. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gant JC, Thibault O, Blalock EM, Yang J, Bachstetter A, Kotick J, Schauwecker PE, Hauser KF, Smith GM, Mervis R, et al. Decreased number of interneurons and increased seizures in neuropilin 2 deficient mice: implications for autism and epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50:629–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghashghaei HT, Weber J, Pevny L, Schmid R, Schwab MH, Lloyd KC, Eisenstat DD, Lai C, Anton ES. The role of neuregulin-ErbB4 interactions on the proliferation and organization of cells in the subventricular zone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1930–1935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510410103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert CD, Wiesel TN. Intrinsic connectivity and receptive field properties in visual cortex. Vision Res. 1985;25:365–374. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(85)90061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal PP, Golden JA. Pax6-/- mice have a cell nonautonomous defect in nonradial interneuron migration. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:752–762. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski JA, Talley T, Qiu M, Puelles L, Rubenstein JL, Jones KR. Cortical excitatory neurons and glia, but not GABAergic neurons, are produced in the Emx1-expressing lineage. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6309–6314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06309.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond V, So E, Gunnersen J, Valcanis H, Kalloniatis M, Tan SS. Layer positioning of late-born cortical interneurons is dependent on Reelin but not p35 signaling. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1646–1655. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3651-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK. Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nat Rev. 2005;6:877–888. doi: 10.1038/nrn1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hevner RF, Daza RA, Englund C, Kohtz J, Fink A. Postnatal shifts of interneuron position in the neocortex of normal and reeler mice: evidence for inward radial migration. Neuroscience. 2004;124:605–618. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell BW, Hawkes R, Soriano P, Cooper JA. Neuronal position in the developing brain is regulated by mouse disabled-1. Nature. 1997;389:733–737. doi: 10.1038/39607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z. Molecular regulation of neuronal migration during neocortical development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;42:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG. Neurotransmitters in the cerebral cortex. J Neurosurg. 1986;65:135–153. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.65.2.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keverne EB. GABA-ergic neurons and the neurobiology of schizophrenia and other psychoses. Brain Res Bull. 1999;48:467–473. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KJ, Dietrich P, Jessell TM. Genetic ablation reveals that the roof plate is essential for dorsal interneuron specification. Nature. 2000;403:734–740. doi: 10.1038/35001507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt P. Disruption of interneuron development. Epilepsia. 2005;7(46 Suppl):22–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Adesnik H, Li J, Long J, Nicoll RA, Rubenstein JL, Pleasure SJ. Regional distribution of cortical interneurons and development of inhibitory tone are regulated by Cxcl12/Cxcr4 signaling. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1085–1098. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4602-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JE, Cobos I, Potter GB, Rubenstein JL. Dlx1 and Mash1 transcription factors control MGE and CGE patterning and differentiation through parallel and overlapping pathways. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:i96–i106. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Bendito G, Sanchez-Alcaniz JA, Pla R, Borrell V, Pico E, Valdeolmillos M, Marin O. Chemokine signaling controls intracortical migration and final distribution of GABAergic interneurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1613–1624. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4651-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysko D, Golden J. SDF-1 signaling directs the migration behavior of interneurons. Program #219.5. Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Chicago (IL): Society for Neuroscience; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marin O, Rubenstein JL. Cell migration in the forebrain. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2003;26:441–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin O, Yaron A, Bagri A, Tessier-Lavigne M, Rubenstein JL. Sorting of striatal and cortical interneurons regulated by semaphorin–neuropilin interactions. Science. 2001;293:872–875. doi: 10.1126/science.1061891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh ED, Minarcik J, Campbell K, Brooks-Kayal AR, Golden JA. FACS-array gene expression analysis during early development of mouse telencephalic interneurons. Develop Neurobiol. 2008;68:434–445. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G, Goffinet AM, Fairen A. What is a Cajal–Retzius cell? A reassessment of a classical cell type based on recent observations in the developing neocortex. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:765–775. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.8.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M, Miyata T, Nakajima K, Yagyu K, Seike M, Ikenaka K, Yamamoto H, Mikoshiba K. The reeler gene-associated antigen on Cajal–Retzius neurons is a crucial molecule for laminar organization of cortical neurons. Neuron. 1995;14:899–912. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pla R, Borrell V, Flames N, Marin O. Layer acquisition by cortical GABAergic interneurons is independent of Reelin signaling. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6924–6934. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0245-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter GB, Petryniak MA, Shevchenko E, McKinsey GL, Ekker M, Rubenstein JL. Generation of Cre-transgenic mice using Dlx1/Dlx2 enhancers and their characterization in GABAergic interneurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;40:167–186. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon M, Rice DS, D'Arcangelo G, Yoneshima H, Nakajima K, Mikoshiba K, Howell BW, Cooper JA, Goldowitz D, Curran T. Scrambler and yotari disrupt the disabled gene and produce a reeler-like phenotype in mice. Nature. 1997;389:730–733. doi: 10.1038/39601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi P, Klausberger T. Defined types of cortical interneurone structure space and spike timing in the hippocampus. J Physiol. 2005;562:9–26. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.078915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumm RK, Zhou C, Ara T, Lazarini F, Dubois-Dalcq M, Nagasawa T, Hollt V, Schulz S. CXCR4 regulates interneuron migration in the developing neocortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5123–5130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05123.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamaki N, Fujimori K, Nojyo Y, Kaneko T, Takauji R. Evidence that Sema3A and Sema3F regulate the migration of GABAergic neurons in the developing neocortex. J Comp Neurol. 2003;455:238–248. doi: 10.1002/cne.10476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka D, Nakaya Y, Yanagawa Y, Obata K, Murakami F. Multimodal tangential migration of neocortical GABAergic neurons independent of GPI-anchored proteins. Development. 2003;130:5803–5813. doi: 10.1242/dev.00825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka DH, Maekawa K, Yanagawa Y, Obata K, Murakami F. Multidirectional and multizonal tangential migration of GABAergic interneurons in the developing cerebral cortex. Development. 2006;133:2167–2176. doi: 10.1242/dev.02382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiveron MC, Rossel M, Moepps B, Zhang YL, Seidenfaden R, Favor J, Konig N, Cremer H. Molecular interaction between projection neuron precursors and invading interneurons via stromal-derived factor 1 (CXCL12)/CXCR4 signaling in the cortical subventricular zone/intermediate zone. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13273–13278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4162-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trommsdorff M, Gotthardt M, Hiesberger T, Shelton J, Stockinger W, Nimpf J, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Herz J. Reeler/disabled-like disruption of neuronal migration in knockout mice lacking the VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2. Cell. 1999;97:689–701. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80782-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo NH, Lu B. Regulation of cortical interneurons by neurotrophins: from development to cognitive disorders. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:43–56. doi: 10.1177/1073858405284360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabut O, Renfro A, Niu S, Swann JW, Marin O, D'Arcangelo G. Abnormal laminar position and dendrite development of interneurons in the reeler forebrain. Brain Res. 2007;1140:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau HJ, Wang HF, Lai C, Liu FC. Neural development of the neuregulin receptor ErbB4 in the cerebral cortex and the hippocampus: preferential expression by interneurons tangentially migrating from the ganglionic eminences. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:252–264. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Assimacopoulos S, Jones KR, Grove EA. Massive loss of Cajal–Retzius cells does not disrupt neocortical layer order. Development. 2006;133:537–545. doi: 10.1242/dev.02209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AB. Cortical amino acidergic pathways in Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1987;24:147–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Flandin P, Long JE, Cuesta MD, Westphal H, Rubenstein JL. Distinct molecular pathways for development of telencephalic interneuron subtypes revealed through analysis of Lhx6 mutants. J Comp Neurol. 2008;510:79–99. doi: 10.1002/cne.21772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer G, Garcez P, Rudolph J, Niehage R, Weth F, Lent R, Bolz J. Ephrin-A5 acts as a repulsive cue for migrating cortical interneurons. European J Neurosci. 2008;28:62–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.