Abstract

We present a case of bilateral severe retinal edema with subretinal fluid in an infant diagnosed with neonatal hemochromatosis and liver failure. A macular cherry-red spot in each eye mimicked the clinical appearance of many metabolic storage diseases. Both the clinical retinal appearance and the anatomic abnormalities observed on spectral domain optical coherence tomography resolved after successful liver transplant.

Case Presentation

A 28-day-old boy born at term to a 29-year-old woman was transferred to our institution with the diagnosis of liver failure. The mother’s prenatal history was positive for cigarette smoking, herpes simplex virus, cervical cerclage, and anxiety treated with bupropion. Family history included seizures of unknown etiology in the father and epistaxis requiring cautery in the mother; the family ocular history was unremarkable. Birth weight was 1,786 g. During the first week of life, he was found to have neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, and hypoproteinemia consistent with liver failure. Iron studies suggested hemochromatosis as a possible diagnosis. The patient also had a history of seizures, possible birth-related retinal hemorrhages, right parietal and frontal parenchymal hemorrhages, and a patent foramen ovale. Ascites was present on an abdominal ultrasound. Negative tests included toxoplasmosis and cytomegalovirus (CMV) titers (mother and infant), CMV urine shell vial culture, GAL-1-P uridyltransferase (galactosemia), succinylacetone (tyrosinemia type 1), and lactate and plasma creatine kinase (mitochondrial disorders).

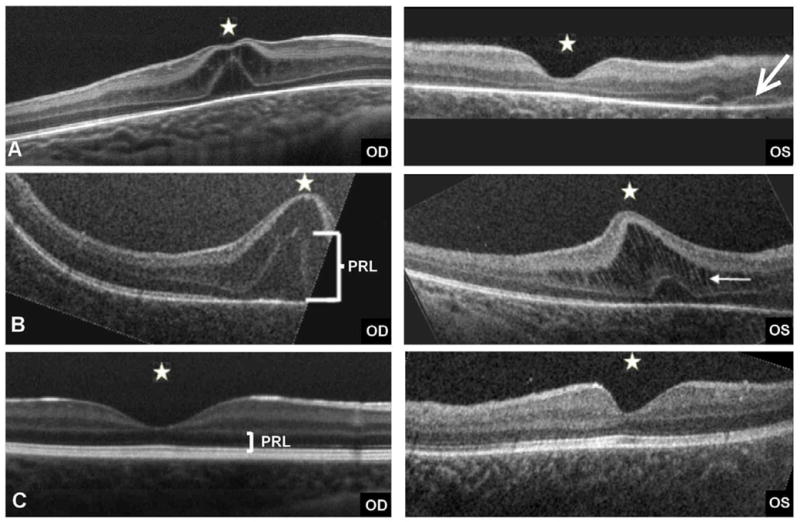

An ophthalmologic consultation at our institution on day 26 of life identified multiple subretinal hemorrhages in the left eye and normal findings in the right. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SDOCT; Bioptigen, Inc,Triangle Park, NC) images showed hyporeflective cysts within the inner nuclear layer of the retina and a bulging foveal elevation consistent with macular edema on the right and subretinal fluid but not macular edema on the left (Figure 1A).

FIG 1.

Retinal changes observed with SDOCT; white stars mark the foveal centers. Note the moderate foveal elevation with cystic changes and thickening of inner and outer nuclear layers in the right eye and normal foveal contour in the left eye. A, An arrow points to areas of subretinal fluid (likely hemorrhages) at 1 month of age. B, Increased foveal thickness with edema in both eyes at 2 months. Note the increased thickness of the photoreceptor layer (PRL) in both eyes. On the left eye, a white arrow marks the thickened inner nuclear layer bridged by the stretched Mueller cells (white vertical strands). C, At 7 months, 3 months after liver transplant, normal foveal configuration is present in both eyes with healthy PRL configuration.

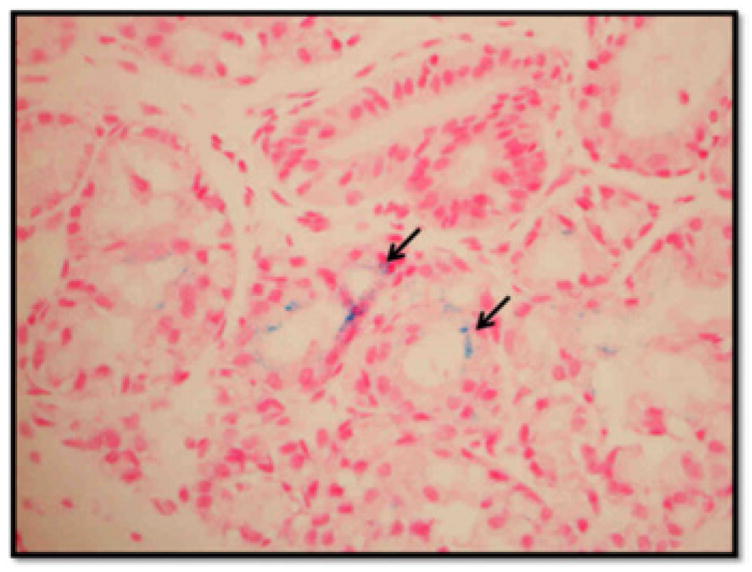

A diagnosis of primary neonatal hemochromatosis was supported by elevated ferritin levels, abnormal iron studies, and a positive lip biopsy demonstrating staining positive for iron deposition (Figure 2). On day 28 of life, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed extra-axial right parietal fluid collection (compatible with a subacute hemorrhage) with areas of hemosiderin, and an arteriovenous malformation in the precentral gyrus of the right frontal lobe, which was thought to be coincidental. Abdominal MRI revealed ascites but no iron reflectance in tissues.

FIG 2.

Upper lip biopsy with iron staining. Iron is visualized as a fine particulate matter (black arrows).

One month after the first examination, questionable edema was noted in the posterior pole of both eyes, with the clinical appearance mimicking “cherry-red spot” maculas. SDOCT imaging revealed cysts and a thickening fovea in both eyes, with a worse appearance in the right eye (Figure 1B).

At 4 months of age, the boy underwent orthotopic liver transplant with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Histopathology of liver tissue showed minimal iron deposits in a small number of hepatocytes and no evidence of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Three months after liver transplant, the baby responded to light and tracked objects. Retinal examination was normal. SDOCT revealed normal foveal configuration for age in both eyes (Figure 1C). His general health was stable, without systemic complications. At 1 year of age, his visual function by preferential looking measured 6.4 cycles/degree at 55cm, within normal range for age.

Discussion

Although ophthalmoscopy initially detected hemorrhages but no edema, worsening edema likely contributed to the clinical perception of macular cherry red spots. Consistent with our experience in other pathologies in neonates, such as tractional schisis or focal retinal detachment, macular edema was visible on SDOCT imaging but not ophthalmolscopy.1 In this case, because of the reversal of the progressive retinal thickening after the liver transplant, we believe that the hyporeflective spaces within the swollen retina were from edema that resolved after the liver transplant.

Some studies have reported hepatic retinopathy in adults with chronic liver disease, describing alterations in the electroretinogram,3 suggesting neuronal damage without consistent abnormalities on ophthalmoscopy other than pigmentary changes.4 Of note, the patient did not receive deferoxamine, an iron chelator that can cause retinal toxicity.2 To our knowledge, this is the first report of infantile retinal edema in the setting of liver failure and its resolution after successful liver transplant. SDOCT allowed for precise diagnosis and follow-up of the resolution of edema. Fluorescein angiography, which is useful in identifying the source of edema fluid, was not performed since intravenous dye injection would have been required.

Macular edema is associated with a decrease in visual acuity in adults and would likely decrease the visual potential of an eye; however, the normal infant visual acuity at ages 2-6 months is calculated to be poor due to the low cone density and lack of complete development of the photoreceptors.5 Transient bilateral macular edema might not affect final visual function, but it might have a disruptive impact on developing neuronal cells. A longer duration of asymmetric macular edema might cause vision loss due to secondary amblyopia.

The cystic changes observed on SDOCT in this case were localized to the inner and outer nuclear layers of the retina; prominent neuronal swelling resembled vertical hyperreflective columns that were likely Muller cells. These findings demonstrate that Muller cells, with the capacity to stretch and elongate in the setting of macular edema, may help prevent further destruction of retinal architecture. We hypothesize that Muller cells support the retinal architecture and function as an expansible net during edema. The return to normal foveal configuration in our patient after liver transplant may have been facilitated by Muller cells. Some patterns of retinal injury may be well tolerated, allowing neuronal tissue to recover from severe edema, as in this case, whereas disruptive damage observed in other retinal diseases albeit with similar foveal swelling, such as x-linked retinoschisis, are less amenable to recovery.

Infants have not previously had access to diagnostic tools such as optical coherence tomography without complex set-up under anesthesia. New portable systems utilizing imaging algorithms are appropriate for young children and have proved useful.6 Future use of such imaging is likely to result in an improved understanding of the ocular pathology associated with certain pediatric diseases and to aid in monitoring response to treatment.

Literature Search

MEDLINE was searched for the period 1960 to the present for the following terms: hepatic retinopathia, neonatal hemochromatosis, and neonatal liver failure.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by the following grants: Angelica and Euan Baird; The Hartwell Foundation; Grant Number 1UL1 RR024128-01 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

The authors thank Dr. Leslie Dodd for providing the histopathology image for this case report.

Footnotes

Study conducted at Duke University.

Financial disclosures (CAT): Alcon Laboratories: royalties, research support, consultant fees; Genentech: research support, consultant fees; Bioptigen: research support, patents.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chavala SH, Farsiu S, Maldonado R, Wallace DK, Freedman SF, Toth CA. Insights into advanced retinopathy of prematurity utilizing handheld spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging. Ophthalmol. 2009;11:2448–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baath JS, Lam WC, Kirby M, Chun A. Deferoxamine-related ocular toxicity: Incidence and outcome in a pediatric population. Retina. 2008;28:894–9. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181679f67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uhlmann S, Uhlman D, Hauss J, Reichembach A, Wiedemann P, Faude F. Recovery from hepatic retinopathy after liver transplantation. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241:451–7. doi: 10.1007/s00417-003-0639-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckstein AK, Reichenback A, Jacobi P, Weber P, Gregor M, Zrenner E. Hepatic Retinopathia. Changes in Retinal Function. Vis Res. 1997;37:1699–706. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(96)00318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendrickson AE, Yuodelis C. The morphological development of the human fovea. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:603–12. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maldonado RS, Izatt JA, Sarin NS, Freedman SF, Wallace DK, Cotten CM, et al. Optimizing hand-held spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging for neonates, infants, and children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:2678–85. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]