Abstract

FXYD proteins, small single-transmembrane proteins, have been proposed to be auxiliary regulatory subunits of Na+–K+-ATPase and have recently been implied in ion osmoregulation of teleost fish. In freshwater (FW) fish, numerous ions are actively taken up through mitochondrion-rich cells (MRCs) of the gill and skin epithelia, using the Na+ electrochemical gradient generated by Na+–K+-ATPase. In the present study, to understand the molecular mechanism for the regulation of Na+–K+-ATPase in MRCs of FW fish, we sought to identify FXYD proteins expressed in MRCs of zebrafish. Reverse-transcriptase PCR studies of adult zebrafish tissues revealed that, out of eight fxyd genes found in zebrafish database, only zebrafish fxyd11 (zfxyd11) mRNA exhibited a gill-specific expression. Double immunofluorescence staining showed that zFxyd11 is abundantly expressed in MRCs rich in Na+–K+-ATPase (NaK-MRCs) but not in those rich in vacuolar-type H+-transporting ATPase. An in situ proximity ligation assay demonstrated its close association with Na+–K+-ATPase in NaK-MRCs. The zfxyd11 mRNA expression was detectable at 1 day postfertilization, and its expression levels in the whole larvae and adult gills were regulated in response to changes in environmental ionic concentrations. Furthermore, knockdown of zFxyd11 resulted in a significant increase in the number of Na+–K+-ATPase–positive cells in the larval skin. These results suggest that zFxyd11 may regulate the transport ability of NaK-MRCs by modulating Na+–K+-ATPase activity, and may be involved in the regulation of body fluid and electrolyte homeostasis.

Keywords: calcium, Danio renio, FXYD-domain ion transport regulator, mitochondria-rich cell, Na+–K+-ATPase, osmoregulation, salinity, teleost

Introduction

Na+–K+-ATPase is an energy transducing ion pump that couples ATP hydrolysis to the active transport of 3Na+ ions out of and 2K+ ions into the cell. Na+–K+-ATPase generates the electrochemical gradient for Na+ and K+ ions across the plasma membrane that is required for maintaining cell volume, membrane potential, and pH homeostasis in excitable and non-excitable cells. In the epithelia of the renal tubules and gut, the Na+ gradient generated by Na+–K+-ATPase drives various ion and nutrient transporters, accomplishing ion- and osmoregulation and nutrient uptake. Na+–K+-ATPase functions as a hetero-oligomer of a large catalytic α subunit (∼110 kDa) and a heavily glycosylated β subunit (∼55 kDa). The pump activity of the α subunit is tightly regulated by various factors, such as intracellular Na+ concentration and phosphorylation which is under hormonal control (Therien and Blostein, 2000; Feraille and Doucet, 2001). The β subunit has important roles in maturation, stability, and trafficking of Na+–K+-ATPase to the plasma membrane, as well as in K+ binding (Geering, 2001; Shinoda et al., 2009). As an additional regulatory subunit, the FXYD-domain containing ion transport regulator (FXYD) family of small single-transmembrane proteins has been identified (Sweadner and Rael, 2000; Geering, 2006). FXYD proteins are characterized by a conserved Phe-X-Tyr-Asp motif at the cytoplasmic sides flanking their transmembrane domains. The transmembrane domain and the FXYD motif have been shown to play a role in binding to the α- and β-subunits (Béguin et al., 1997; Shinoda et al., 2009). FXYD proteins modulate Na+–K+-ATPase activity by affecting the apparent affinities for intracellular Na+ and extracellular K+ ions (Béguin et al., 1997, 2001, 2002; Arystarkhova et al., 1999; Pu et al., 2001; Crambert et al., 2002, 2005; Garty et al., 2002; Geering, 2006; Delprat et al., 2007). In mammals, seven FXYD members (FXYD1–7) have been identified and shown to be expressed in a tissue-specific manner with distinct modulatory effects. The physiological roles of several FXYD proteins have been investigated by phenotypic analyses of knockout mice. FXYD1 (also known as phospholemman; PLM) is mainly expressed in heart, liver, and skeletal muscle, and its gene disruption leads to mild cardiac hypertrophy, increased ejection fraction, and a decrease in Na+–K+-ATPase activity and protein expression (Jia et al., 2005). Together with the fact that FXYD1 is physically and functionally associated with Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in myocytes (Zhang et al., 2003; Mirza et al., 2004), FXYD1 is likely involved in the regulation of cardiac contractility and intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Disruption of Fxyd2 (also known as γ subunit), which is highly expressed in the kidney, causes an increase in affinities for Na+ and ATP of renal Na+–K+-ATPase, but no obvious effect is seen on renal function (Jones et al., 2005). However, a mutation in the transmembrane domain of FXYD2 has been associated with renal hypomagnesemia (Meij et al., 2000; Pu et al., 2002). Knockout mice for Fxyd4 (also known as corticosteroid hormone-induced factor; CHIF), which is expressed in the distal nephron and colon, exhibit only mild renal impairment such as increased urine excretion and glomerular filtration rate during a high-K+ or low-Na+ diet (Aizman et al., 2002; Goldschimdt et al., 2004). Moreover, in the distal colon, Na+ absorption is decreased even under normal conditions, suggesting the role of FXYD4 in electrolyte balance. Although less characterized than in mammals, some of orthologous and paralogous FXYD have been cloned from non-mammalian vertebrates, including spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias) (Mahmmoud et al., 2000, 2003), Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) (Tipsmark, 2008), and spotted green pufferfish (Tetraodon nigroviridis) (Wang et al., 2008). Recent studies have demonstrated that several teleost fxyd isoforms are expressed in the gills and kidney and their expression levels are altered in response to ambient salinity changes, suggesting a possible role in the regulation of body fluid and electrolyte homeostasis (Tipsmark, 2008; Wang et al., 2008).

Fish living in freshwater (FW) are hyperosmotic to their environment (∼300 vs. ∼1 mOsm/l), and therefore constantly lose ions, mainly Na+ and Cl−, and gain water. FW fish try to compensate this ionic and osmotic disturbance by active ion uptake through the gill and skin epithelium and excretion of dilute urine (Evans et al., 2005). In the gills and skin, mitochondrion-rich cells (MRCs, also called ionocytes or chloride cells) are the major sites of ion uptake, where Na+–K+-ATPase and numerous ion transporters are present (Marshall, 2002; Hirose et al., 2003; Perry et al., 2003; Kirschner, 2004; Evans et al., 2005; Hwang, 2009). Na+–K+-ATPase pumps Na+ ions out of MRCs across the basolateral membrane, maintaining a low intracellular Na+ concentration. The Na+ gradient across the apical membrane is proposed to provide the driving force for ion uptake. Although there is no doubt that Na+–K+-ATPase activity is essential for hypoosmotic adaptation of FW and euryhaline teleosts, a clear understanding as to how the activity in MRCs is regulated remains to be achieved. Recently, Wang et al. (2008) have provided evidence for FXYD-mediated regulation of Na+–K+-ATPase activity in MRCs of euryhaline teleost pufferfish, that is, (1) a pufferfish FXYD protein (pFXYD) is coincident and associated with Na+–K+-ATPase in the gill MRCs, and (2) the mRNA and protein expression levels of pFXYD are significantly increased after FW adaptation. In contrast, little is known about fxyd expression in MRCs of FW teleosts. It is therefore necessary to determine the identity and function of fxyd isoforms expressed in FW fish MRCs in order to further understand the ion uptake mechanism by MRCs.

Zebrafish (Danio renio) is a stenohaline FW fish that can adapt to salinity changes in FW but not in seawater, and is increasingly recognized as a useful model organism for studies on the mechanism of ionic and osmotic homeostasis. The advantages of this model in studies are that (1) a combination of molecular and genetic approaches has been established, and (2) database of gene expression and genome information are currently available. Zebrafish has at least three types of MRCs in the skin and gill: MRCs rich in vacuolar-type H+-ATPase (vH+-ATPase) (vH-MRCs or HR cells), Na+–K+-ATPase (NaK-MRCs or NaR cells), or Na+–Cl− cotransporter (NCC cells) (Hwang, 2009). Multiple lines of evidence have demonstrated a primary role of vH-MRCs in Na+ ion uptake through cooperation of vH+-ATPase, Na+/H+ exchanger, and carbonic anhydrases (Lin et al., 2006, 2008; Esaki et al., 2007; Horng et al., 2007; Yan et al., 2007). On the other hand, the physiological roles of other two MRC subpopulations remain to be established, but NaK-MRCs and NCC cells are likely responsible for uptake of Ca2+ and Cl− ions, respectively (Pan et al., 2005; Liao et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2009). Most recently, Liao et al. (2009) have reported that each type of MRC expresses different Na+–K+-ATPase α isozymes in the zebrafish gill, mRNA expression levels of which are affected by environmental Na+, Cl−, and Ca2+ concentrations. Thus, it is conceivable that FXYD proteins may be expressed as a Na+–K+-ATPase regulator in the MRCs of FW fish. To address this issue, in this study, we sought to identify a FXYD protein(s) that is expressed in zebrafish MRCs. We demonstrated that zebrafish Fxyd11 (zFxyd11) is highly expressed in NaK-MRCs of the larval skin and gills, the expression levels of which are induced in low salinity environment. We further showed that zFxyd11 was associated with Na+–K+-ATPase in NaK-MRCs, and its knockdown affected the number of Na+–K+-ATPase–positive cells of the larval skin. These results suggest that zFxyd11 is likely the regulator of Na+–K+-ATPase and involved in transepithelial ion transport across NaK-MRCs.

Materials and Methods

Zebrafish culture

Zebrafish were maintained as described in “The Zebrafish Book” (Westerfield, 1995). The wild-type zebrafish Tubingen long fin (TL) line was generously provided by Dr. Atsushi Kawakami (Yokohama, Japan). Unless otherwise mentioned, fertilized eggs were incubated at 28.5°C in 1× FW [60 mg ocean salt (Rohtomarine; Rei-sea, Tokyo, Japan) per 1 l of distilled water, pH 7.7], which was used as our standard FW and corresponded to “Fish Water” (Westerfield, 1995). The concentration of major ions of 1× FW are as follows: Na+, 686 μM; K+, 14.6 μM; Ca2+, 16.2 μM; Mg2+, 78.3 μM; Cl− 804 μM; SO4−, 41.6 μM; and Br−, 1.25 μM. Hatched or dechorionated larvae were used for the following experiments without feeding. The animal protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tokyo Institute of Technology.

Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA of whole larvae and various tissues of adult zebrafish was isolated as described previously (Tran et al., 2006; Nakada et al., 2007). For cDNA synthesis, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed with oligo(dT)20 primer and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The resulting first strand cDNA (0.5 μl) was used for PCR amplification in a reaction mixture containing 1.25 U of ExTaq DNA polymerase (Takara, Shiga, Japan), 2.5 μl of 10× ExTaq buffer (Takara), 0.2 mM dNTP, and the following primer sets (0.2 mM each; listed in the order of forward and reverse): zfxyd2, 5′-atgggagtggaaagtcctgagcattcagat-3′ and 5′-atcgtagcagaggactttccacatctgag-3′; zfxyd12, 5′-atgtcaggagctcaggaggaagaggagcct-3′ and 5′-atcgaaatggcttcatccccatgcttgccc-3′; zfxyd5, 5′-atgtcattcctcattccttatcagatgacc-3′ and 5′-atcgaacttctggtcacctcgtatgaactt-3′; zfxyd6, 5′-atggaaactgttctggtcttcctttttccc-3′ and 5′-atccagttttctgctgtaggagtctccttg-3′; zfxyd8, 5′-atggaactttgtgttgctgcagcgcttttg-3′ and 5′-atctttgcacctctggctgcctctgcgtca-3′; zfxyd9, 5′-atgaaatctttggcactagtgttcttgaca-3′ and 5′-atcgagcattcactcgccctcgctgtgtcg-3′; zfxyd7, 5′-atggaagcctcaacagggtcatacacgcat-3′ and 5′-atcgaaaaatacagcagtagatcagcattt-3′; and zfxyd11, 5′-atgagccagctcacagaactagttctccta-3′ and 5′-atcgagattttgcttgcgtcatcatcatgc-3′. The Thermal cycler program was 3 min at 94°C, followed by 25 cycles of 20 s at 94°C, 30 s at 58°C, and 1 min at 72°C. The PCR experiments were repeated twice (Figure 2A) or three times (Figures 1A and 2B,C) and representative results are shown.

Figure 2.

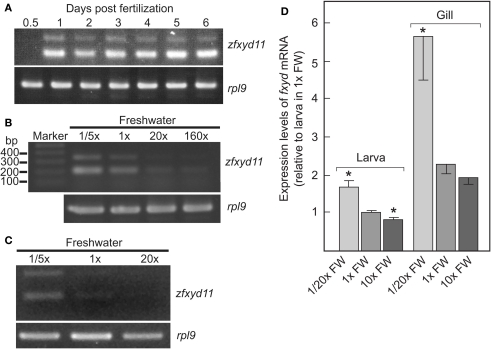

Developmental stage- and ionic strength-dependent expression of zfxyd11 mRNA. (A) Expression of zfxyd11 at different developmental stages of zebrafish. RT-PCR was performed with total RNA isolated from the indicated stages of whole embryos/larvae. rpl9 was used as an internal control. (B) Expression of zfxyd11 and rpl9 was analyzed by RT-PCR with total RNA isolated from 7-dpf larvae acclimated to 1/5×, 1×, 20×, and 160× FW. Each acclimation was started at 1-dpf and extended to 7-dpf. (C) Expression of zfxyd11 and rpl9 was analyzed by RT-PCR with total RNA isolated from the gills of seven adult zebrafish acclimated to 1/5×, 1×, and 20× FW for 2 weeks. (D) zfxyd11a mRNA expression in larvae and gills of zebrafish acclimated to the indicated salinity by quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) (n = 4). Data are expressed relative to the mRNA level of larvae acclimated to 1× FW. *p < 0.05 in the comparison with 1× FW (Student's t-test).

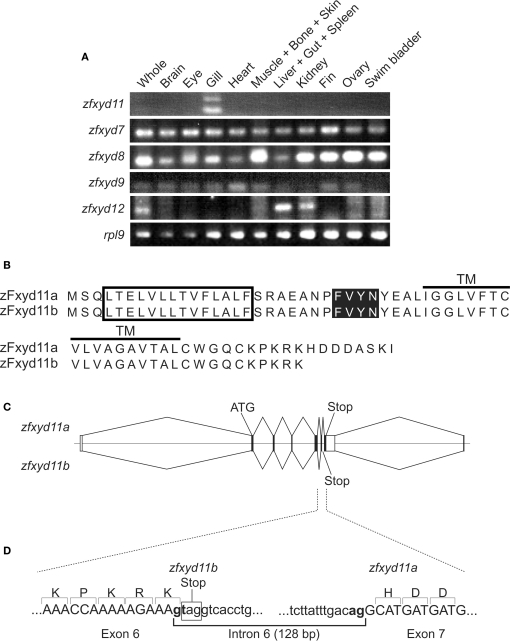

Figure 1.

Tissue expression pattern of zebrafish fxyd isoforms and structure of zfxyd11 variants. (A) Total RNA isolated from various tissues of adult zebrafish were subjected to RT-PCR amplification by using specific primers for the indicated zebrafish fxyd isoforms and ribosomal protein L9 (rpl9). (B) Amino acid sequences of zFxyd11a and zFxyd11b. The putative signal sequences and the transmembrane (TM) domains are indicated by box and horizontal, respectively. The FXYD motifs are highlighted. (C) Schematic representation of alternative splicing of the zfxyd11 gene. Exons are indicated by boxes, and introns and flanking regions are indicated by horizontal lines. The coding and untranslated regions are indicated by dark and open boxes, respectively. zFxyd11b is generated through alternative use of the stop codon in intron 6. (D) Exon-intron organization and boundary sequence of zfxyd11a. The splice donor and acceptor sequences are bold, and the stop codon of zfxyd11b is indicated by the box.

Plasmids

The zfxyd11a cDNA fragment amplified with the above mentioned primer set was cloned into the EcoRV site of pBluescript II SK(−) (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), yielding pBS-zfxyd11a. By using pBS-zfxyd11a as template, primer-based site-directed mutagenesis was performed to introduce a stop codon at the end of the open reading frame of zfxyd11a with primers (5′-acgcaagcaaaatctagatatcgaattcctg-3′ and 5′-caggaattcgatatctagattttgcttgcgt-3′). The XhoI–XbaI-digested fragment of the mutated pBS-zfxyd11a was cloned into pCS2+ vector (RZPD German Resource Center for Genome Research, Berlin, Germany), yielding pCS2-zfxyd11a. A C-terminally 3× FLAG-tagged zFxyd11a (zFxyd11a-FLAG) was constructed by cloning the HindIII-EcoRV fragment of pBS- zfxyd11a into the same sites of p3× FLAGCMV14 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). An extracellularly 3× FLAG-tagged major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecule was constructed by cloning a cDNA fragment encoding residues 25–365 of HLA-A6802 into the EcoRI-XbaI site of the pSecTag-FLAG-furin vector (Nakamura et al., 2005). All constructs were verified by sequencing.

Semi-quantification of gene expression levels in different salinity condition by RT-PCR

In addition to 1× FW as a routine medium, we prepared 1/5× FW (12 mg ocean salt per liter) as a dilute FW medium and 20× FW (1.2 g ocean salt per liter) and 160× FW (9.6 g ocean salt per liter) as a concentrated medium. Adult zebrafish were cultured in 1/5× FW, 1× FW, 20× FW, and 160× FW for 2 weeks, and the gills were then isolated. Total RNA of the gills was isolated and RT-PCR was performed as described above.

In situ hybridization

A cDNA encoding the open reading frame of zfxyd11a was subcloned into pGEMT-Easy vector (Promega, Medison, WI, USA) and was used for generation of digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled sense or antisense RNA probes. Paraffin-embedded sections of zebrafish gills (6-μm thickness) were de-paraffined with xylene, and rehydrated through an ethanol series and PBS. The sections were fixed 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min and then washed with PBS. The sections were treated with 8 g/ml proteinase K in PBS for 30 min at 37°C, washed with PBS, re-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, again washed with PBS, and placed in 0.2 N HCl for 10 min. After washing with PBS, the sections were acetylated by incubation in 0.1 M tri-ethanolamine-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.25% acetic anhydride for 10 min. After washing with PBS, the sections were dehydrated through a series of ethanol. Hybridization was performed with probes at concentrations of 300 ng/ml in the Probe Diluent-1 (Genostaff, Tokyo, Japan) at 60°C for 16 h. The sections were washed in 5× HybriWash (Genostaff), equal to 5× SSC, at 60°C for 20 min and then in 50% formamide, 2× HybriWash at 60°C for 20 min, followed by RNase treatment in 50 μg/ml RNaseA in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA for 30 min at 37°C. The sections were washed twice with 2× HybriWash at 60°C for 20 min and once with TBST (0.1% Tween-20 in TBS). After treatment with 0.5% blocking reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) in TBST for 30 min, the sections were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG antibodies (diluted 1:1,000 with TBST) for 2 h at room temperature. The sections were washed twice with TBST and then incubated in 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween-20, 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.5. Coloring reactions were performed with NBT/BCIP solution (Sigma) overnight and then washed with PBS. The sections were counterstained with Kernechtrot stain solution (Muto Pure Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan), dehydrated, and then mounted with Malinol (Muto Pure Chemicals).

Antibodies

Polyclonal antiserum specific for zFxyd11a was made in rabbits that had been immunized with a keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH)-conjugated synthetic peptide corresponding to residues 53–69 of zFxyd11a (Operon Biotechnologies, Tokyo, Japan). Polyclonal antiserum specific for vH+-ATPase was made in rats that had been immunized with recombinant proteins of the vH+-ATPase β subunit of dace (Tribolodon hakonensis) (Hirata et al., 2003).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining of larvae at 2 days postfertilization (dpf) were performed as described previously (Esaki et al., 2007), with exceptions that larvae were incubated two overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-zFxyd11 antiserum (diluted 1:2,000 with PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 10% sheep serum), rat anti-eel (Anguilla japonica) α-subunit of Na+–K+-ATPase antiserum (Miyamoto et al., 2002) (diluted 1:2,000), and rat anti-dace vH+-ATPase antiserum (diluted 1:1,000). Immunohistochemistry of gill sections was performed as described previously (Nakada, et al., 2007). After blocking with fetal bovine serum (FBS), the sections were incubated with anti-zFxyd11 (diluted 1:2,000) and anti-eel α-subunit of Na+–K+-ATPase antisera (diluted 1:2,000) overnight at 4°C, followed by appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Hoechst 33342 (100 ng/ml; Invitrogen) was added in the secondary antibody solutions for nuclei staining. Fluorescence images were acquired by using Axiovert 200M epifluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) equipped with an ApoTome optical sectioning device (Carl Zeiss).

Morpholino-mediated knockdown

Morpholinos are chemically modified oligonucleotides that are more stable in, and less toxic to, living cells. An antisense morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) specific for zfxyd11 (5′-ctcacagaactagttctcctaacaggtaagtcaggattatttgtgtatac-3′) was designed to complementarily anneal to the splicing donor site of the first exon of the zfxyd11 transcript to block pre-mRNA splicing, and synthesized by Gene Tools (Philomath, OR, USA). For negative control experiments, Standard Control Oligo, Classic (Gene Tools) was used. Approximately 3 nl of 1 ng/nl MOs in 1× Danieau buffer [58 mM NaCl, 0.7 mM KCl, 0.4 mM MgSO4, 0.6 mM Ca(NO3)2, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.6] was injected into the yolk of one-cell stage embryos, and then reared in 1× FW. The inhibitory action of MO was confirmed by RT-PCR; no doublet bands corresponding to zfxyd11a and zfxyd11b mRNA, which are typically seen in Figures 1 and 2, were amplified from total RNA preparations of MO-treated larvae (data not shown). For rescue experiments, the pCS2-zfxyd11 vector was linearized by NotI, and used as template to synthesize capped and polyadenylated zfxyd11a mRNA by using an SP6 RNA polymerase kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). The synthesized zfxyd11a mRNA was injected into cells at one-cell stage embryos at 30 pg/nl together with the zfxyd11 MOs.

In situ proximity ligation (PLA) assay

Gill sections were prepared as described above, and were blocked with 1% FBS in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were incubated with rabbit anti-zFxyd11 (diluted to 1:1,000) and rat anti-eel α-subunit of Na+–K+-ATPase antisera (diluted 1:1,000) for 2 days at room temperature, followed by corresponding secondary antibodies conjugated with the PLA oligonucleotide probes (PLA probe rabbit PLUS and PLA probe rat MINUS; Olink Bioscience, Uppsala, Sweden; diluted 1:5 with 1% FBS in PBS) for 2 h at 37°C. Hybridization and ligation of the connector oligonucleotides, a rolling-circle amplification, and detection of the amplified DNA products were performed with in situ PLA detection kit 613 (Olink Bioscience) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Following addition of 0.1% p-prenylenediamine and 90% glycerol in PBS, the slides were covered with cover slips and photographed.

Cell culture and transfection

Human embryonic kidney fibroblast 293T cells and human cervical HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium containing 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Transient transfection of plasmid DNA was performed using TransFectin reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Membrane extraction assay

293T cells transfected with zFxyd11a-FLAG were homogenized in 600 μl of PBS containing protease inhibitors (10 mM leupeptin, 1 mM pepstatin, 5 mg/ml aprotinin, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The homogenates were divided into four aliquots of 150 μl each, and they were centrifuged at 100× g for 20 min to separate the membranes from the cytosol. Extraction and fractionation of the membranes were performed as described previously (Nakamura and Hirose, 2008).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

HeLa cells grown on cover slips were transfected with either zFxyd11a-FLAG or FLAG-MHC-I. Immunofluorescence staining of transfected cells was performed as described previously (Nakamura et al., 2005) with exception that the permeabilization step was omitted to examine extracellular staining of the proteins.

Cell-surface biotinylation

HeLa cells grown on a 6-well plate were transfected with zFxyd11a-FLAG. At 2 days after transfection, cell-surface proteins were biotinylated, extracted, and then purified with streptavidin–agarose beads (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) as described previously (Nakamura et al., 1999).

Real-time PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA used for qPCR was extracted independently of that used for RT-PCR from (i) twenty 5-dpf larvae adapted for 4 days to 1/20×, 1×, and 10× FW and (ii) gills from two adult zebrafish adapted for 3 days to 1/20×, 1×, and 10× FW by the acid guanidine isothiocyanate-phenol-chloroform method with Isogen (Nippon Gene Co., Toyama, Japan). Synthesis of first strand cDNA and qPCR were performed as described previously (Hoshijima and Hirose, 2007). The primer sets used for qPCR were as follows (in the order of forward and reverse): fxyd11a, 5′-gccagctcacagaactagttctc-3′ and 5′-aagcacacatgtgaagaccaaac-3′; β-actin, 5′-tgttttcccctccattgttggac-3′ and 5′-cgtgctcaatggggtatttgagg-3′, which were designed to have Tm of 59.7/59.0 and 60.3/60.6°C and generate products of 125 and 134 bp, respectively.

Results

Identification of a gill-specific isoform of zebrafish fxyd

Through database searches, we found eight members of the zebrafish Fxyd (zFxyd) family (zfxyd2, zfxyd5, zfxyd6, zfxyd8, zfxyd7, zfxyd9, zfxyd11, and zfxyd12). To determine the tissue distribution of each zfxyd isoform, we performed RT-PCR analysis by using RNA prepared from various tissues of adult zebrafish. We could detect amplified products for five out of eight zfxyd genes (zfxyd7, zfxyd8, zfxyd9, zfxyd11, and zfxyd12; Figure 1A). Among them, only zfxyd11 was found to be specifically expressed in the gill. The zfxyd12 message was detected in the liver and kidney, and other three members (zfxyd7, zfxyd8, and zfxyd9) showed broad expression patterns. We expected that zfxyd11 has an important role in the gill function, in particular ion transport, and initiated its characterization.

Gene structure and alternative splicing of zfxyd11

In the RT-PCR assay, two zfxyd11 cDNA fragments were amplified by using a single primer set (Figure 1A). Sequencing of the PCR products revealed that the short fragment (210 bp) encodes a 69-amino acid protein, termed here zFxyd11a, and the long one (338 bp) encodes a truncated zFxyd11a lacking eight C-terminal amino acids, termed here zFxyd11b (Figure 1B). Each nucleotide sequence was mapped back to the zebrafish genome by Blast search to identify the exon–intron structure of the zfxyd11 gene. The zfxyd11b transcript consists of five coding exons whereas the zfxyd11a is generated by a further alternative splicing within exon 6 (Figure 1C). This splicing follows the canonical GT–AG rule and the donor site is located just before the stop codon for the zfxyd11b open reading flame (Figure 1D). The zfxyd11a transcript thus acquires an 8-amino acid C-terminal extension by skipping this stop codon.

Developmental stage- and salinity-dependent expression of zfxyd11 mRNA

We examined expression of zfxyd11 mRNA at different developmental stages from 12 h postfertilization (hpf) to 6-dpf. Total RNA of whole zebrafish embryos/larvae was extracted at each developmental stage and subjected to RT-PCR amplification with primers for zfxyd11 and ribosomal protein L9 (rpl9, used as an internal control). As shown in Figure 2A, the zfxyd11 expression was detectable at 1-dpf and all subsequent stages we examined. Since it has been shown that ambient ionic strength affects the expression levels of several teleost fxyd isoforms in salmon (Tipsmark, 2008) and pufferfish (Wang et al., 2008), we next examined whether zfxyd11 mRNA expression responds to environmental salinity. Zebrafish larvae were transferred from standard FW (1× FW) to either fivefold diluted FW (1/5× FW) or 20- or 160-fold concentrated FW (20× or 160× FW) at 24-hpf and cultured for 6 days. As shown in Figure 2B, zfxyd11 mRNA expression was increased in 1/5× FW-acclimated larvae whereas it was decreased under high salinity conditions. A similar effect was observed in the gill of adult zebrafish acclimated to 1/5×, 1×, and 20× FW for 2 weeks (Figure 2C). The salinity-dependent expression of fxyd11 in larvae and gills was confirmed by real-time PCR (Figure 2D).

Expression of zfxyd11 in NaK-MRCs

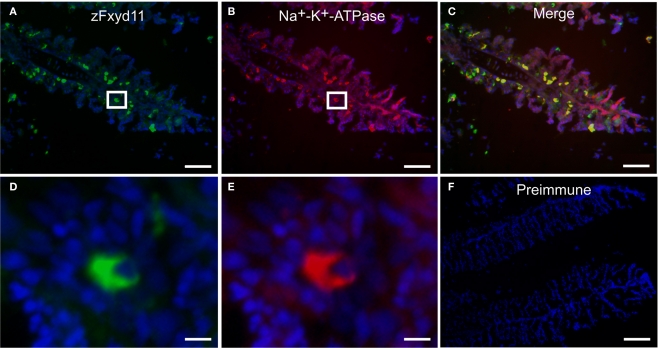

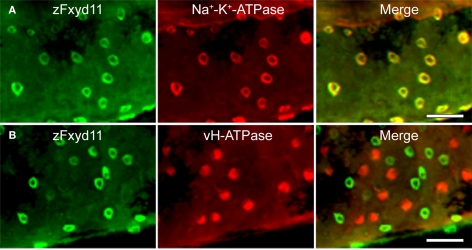

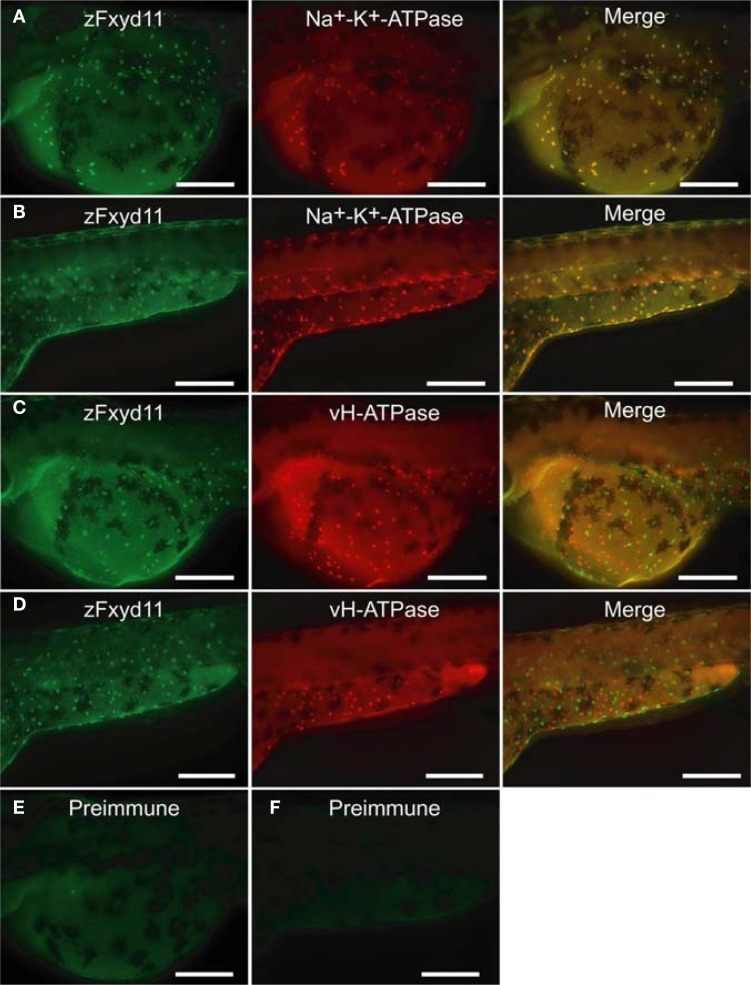

To elucidate localization of zfxyd11 mRNA at the cellular level, we carried out in situ hybridization on paraffin-embedded gill sections of adult zebrafish. Strong labeling was detected in the basal regions of the secondary lamellae with the antisense zfxyd11 probe (Figure 3A). No such staining was observed in control experiments with the sense probe (Figure 3B). We also performed in situ hybridization using 1- to 7-dpf zebrafish larvae, but we could not detect any positive signal in either 1× FW- or 1/5× FW-acclimated larvae (data not shown). Expression of zfxyd11 in larvae was probably too low to detect under our experimental conditions. Since FXYD proteins are known to modulate Na+–K+-ATPase activity, we expected that zFxyd11 is expressed in the Na+–K+-ATPase-rich MRCs in the gills. To examine this, we carried out immunohistochemical analysis of the gills by using rabbit polyclonal antiserum specific to the C-terminus of zFxyd11a. Gill sections of adult zebrafish were doubly stained with anti-zFxyd11 antiserum and anti-Na+–K+-ATPase antiserum (to stain NaK-MRCs). As expected, signals for zFxyd11 were detected on NaK-MRCs in the gill filaments (Figures 4A–E). No specific staining was observed with preimmune serum (Figure 4F), confirming the specificity of the antiserum. In contrast to our results of in situ hybridization, which failed to detect signals in the skin of larvae, we could detect zFxyd11 protein expression in 2-dpf zebrafish larvae by immunohistochemistry. The staining of zFxyd11 was colocalized with that of Na+–K+-ATPase in the skin of the yolk sac, yolk sac extension, and trunk (Figure 5A and Figures S1A,B in Supplementary Material). When zFxyd11 was labeled with vH+-ATPase, a marker for vH-MRCs, two proteins were detected separately (Figure 5B and Figures S1C,D in Supplementary Material). No such zFxyd11 signal was observed with preimmune serum (Figures S1E,F in Supplementary Material). Therefore, these results indicate that zFxyd11 is expressed preferentially in NaK-MRCs of the gills and larval skin.

Figure 3.

Expression pattern of zfxyd11 mRNA in the gill of adult zebrafish. In situ hybridization was performed on paraffin-embedded gill sections of adult zebrafish with a DIG-labeled zfxyd11 antisense probe (A) or a sense probe as a control (B). Signals for zfxyd11 mRNA (violet) appeared to be abundant in the basal regions of the secondary lamellae. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Figure 4.

Localization of zFxyd11 in NaK-MRCs of the gill of adult zebrafish. Immunofluorescence staining was performed on cryosections of the gill of adult zebrafish with anti-Na+–K+-ATPase antiserum [red in (B), (C), (E)] along with either anti-zFxyd11 antiserum [green in (A), (C), (D)] or with preimmune serum [green in (F)]. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). High magnification images of zFxyd11-positive cells in the boxed areas in (A,B) are shown in (D,E), respectively. Scale bars in (A–C), 50 μm; in (D,E), 5 μm; in (F), 100 μm.

Figure 5.

Localization of zFxyd11 in NaK-MRCs of the skin of zebrafish larvae. Immunofluorescence staining was performed on 2-dpf zebrafish larvae with anti-zFxyd11 antiserum [green in (A), (B)], along with anti-Na+–K+-ATPase (red in (A)] or anti–vH+-ATPase antiserum [red in (B)]. Regions of the yolk sac extension are shown. Note that signals for zFxyd11 entirely overlap with NaK-MRCs (A), and are not colocalized with vH-MRCs (B). Scale bars, 40 μm.

Interaction of zfxyd11 with Na+–K+-ATPase in the gills

To examine whether zFxyd11 interacts with Na+–K+-ATPase, we performed the in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA) that enables to visualize endogenous protein–protein interactions at single molecular resolution (Söderberg et al., 2008). Cryosections of the gills of adult zebrafish were incubated with anti-zFxyd11 and anti-Na+–K+-ATPase antisera followed by corresponding secondary antibodies conjugated with different oligonucleotides (PLA probes) that provide templates for two connector oligonucleotides. Annealing and ligation of the connector oligonucleotides produced a circular single-stranded DNA molecule, which was then amplified by rolling-circle amplification to generate a long single-strand DNA composed of tandem repeats of the DNA circle. The DNA products were visualized by hybridizing fluorescent-labeled oligonucleotide probes. As shown in Figure 6, a number of in situ PLA signals were detected on the gill lamellas with anti-zFxyd11 and anti-Na+–K+-ATPase antisera, while no signal was observed with preimmune serum instead of anti-zFxyd11 antiserum. The result suggests that zFxyd11 interacts with Na+–K+-ATPase in NaK-MRCs.

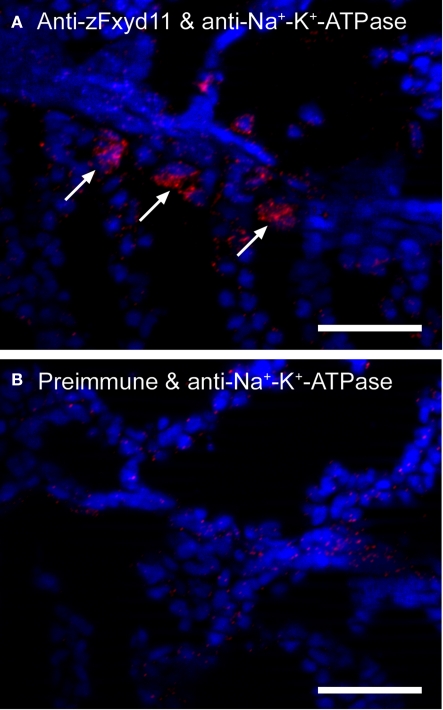

Figure 6.

Interaction between zFxyd11 and Na+–K+-ATPase. In situ PLA was performed on cryosections of the gills of adult zebrafish with anti-Na+–K+-ATPase antiserum along with either anti-zFxyd11 antiserum (A) or corresponding preimmune serum (B). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Signals of interaction of two proteins were detected on the basal regions of the secondary lamellae (red, arrows). Scale bars, 25 μm.

Effects on zfxyd11 knockdown on the number of Na+–K+-ATPase–positive cells

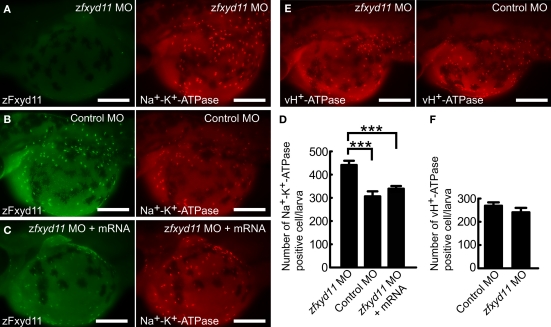

To investigate the physiological functions of zFxyd11, we performed zfxyd11 knockdown experiments using morpholino antisense oligonucleotides (MOs) in zebrafish larvae. Control or zfxyd11 MOs were injected into fertilized eggs at the one-cell stage, and the embryos were then allowed to develop to 2-dpf. Immunostaining of zfxyd11 morphants showed no signal for zFxyd11, confirming zfxyd11 knockdown at the protein level (Figure 7A). We analyzed the protein levels of Na+–K+-ATPase in NaK-MRCs by immunofluorescence microscopy. Average fluorescence intensity of labeled cells was similar between control and zfxyd11 morphants. However, to our surprise, the number of Na+–K+-ATPase–positive cells apparently increased in the zfxyd11 morphants compared with control larvae (compare Figure 7A and Figure 7B). Quantitative analysis revealed that the number of Na+–K+-ATPase–positive cells was significantly increased by zfxyd11 knockdown [221 ± 24.2 vs. 153 ± 28.7 (control), p < 0.001; Figure 7D]. The effect of zfxyd11 knockdown was abrogated by co-injection with mRNA encoding zFxyd11a, and the number of NaK-MRCs was restored to control levels (Figures 7C,D) In contrast, the number of vH+-ATPase–positive cells was not changed by zfxyd11 knockdown (Figures 7E,F).

Figure 7.

Effects of zFxyd11 knockdown. (A–C) Immunofluorescence staining was performed on zfxyd11-MO-injected (A), control-MO-injected (B), and zfxyd11-MO with zfxyd11a mRNA-injected larvae (C) with anti-zFxyd11 antiserum (green), along with anti–Na+–K+-ATPase antiserum (red). No signal for zFxyd11 was detected in zfxyd11 morphants (A). (D) The number of Na+–K+-ATPase–positive cells in the skin was counted and is represented as the mean ± SEM. Significant differences were evaluated by one-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparison test (***p < 0.001, n = 7). (E) Immunofluorescence staining was performed on zfxyd11-MO-injected (left panel), control-MO-injected larvae (right panel) with anti–vH+-ATPase antiserum. (F) The number of vH+-ATPase–positive cells in the skin was counted and is represented as the mean ± SEM. The number of vH+-ATPase-positive cells was not affected by zFxyd11 knockdown (n = 7).

Membrane topology of zFxyd11a

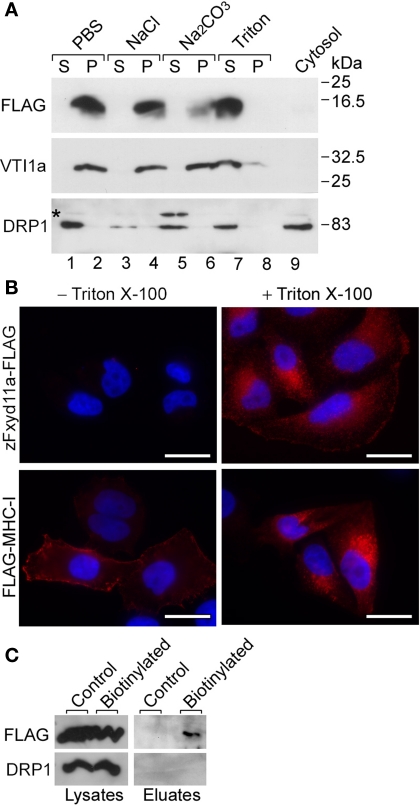

zFxyd11a has two hydrophobic regions, corresponding to an N-terminal signal sequence and a transmembrane span (see Figure 1B). zFxyd11a is thus predicted to be a type-I single- transmembrane protein (i.e., the protein has an Nout–Cin orientation). To examine if zFxyd11a is an integral membrane protein, the membrane fractions were prepared from 293T cells transfected with a C-terminal FLAG-tagged zFxyd11a (zFxyd11a-FLAG) and were then incubated in PBS, 1 M NaCl, 0.1 M Na2CO3 (pH 11.5), or 1% Triton X-100. After ultracentrifugation, the resulting supernatants and membrane pellets were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies to FLAG, VTI1A [an integral membrane protein (Xu et al., 1998)], and dynamin-related protein 1 [DRP1, a cytosolic and peripheral membrane protein (Yoon et al., 1998)]. Under these conditions, zFxyd11a-FLAG could be solubilized effectively only in Triton X-100, an extraction profile similar to VTI1A (Figure 8A, top and middle panels). In contrast, DRP1 was released from the membranes by treatments with 1 M NaCl and 0.1 M Na2CO3 (Figure 8A, bottom panel). Next, to confirm the topology of zFxyd11a, we performed immunofluorescence microscopy of transfected HeLa cells. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with either zFxyd11a-FLAG or extracellularly FLAG-tagged MHC class I (FLAG-MHC-I). The cells were then stained by using anti-FLAG antibody with or without Triton permeabilization. As shown in Figure 8B, both proteins were stained with permeabilization whereas only FLAG-MHC-I was stained without permeabilization. To confirm cell-surface expression of zFxyd11a-FLAG in the transfected cells, cell-surface proteins were biotinylated, isolated by binding to streptavidin beads, and then subjected to Western blotting with anti-FLAG antibody. As shown in Figure 8C, the protein band corresponding to zFxyd11a-FLAG was detected in the biotinylated protein sample. These results suggest that zFxyd11a is an integral membrane protein extruding its C-terminal tail to the cytosol.

Figure 8.

Membrane topology of zFxyd11a. (A) Homogenates of 293T cells expressing zFxyd11a-FLAG were fractionated into the cytosolic (lane 9) and membranous fractions. The membranes were incubated with PBS (lanes 1 and 2), 1 M NaCl (lanes 3 and 4), 0.1 M Na2CO3 (pH 11.5, lanes 5 and 6), or 1% Triton X-100 (lanes 7 and 8) followed by ultracentrifugation to separate soluble protein supernatants (S; lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) from membranous pellets (P; lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). The samples were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against FLAG, VTI1a (a TM protein), and DRP1 (a cytosolic protein). (B) HeLa cells were transfected with either zFxyd11a-FLAG (top panels) or FLAG-MHC-I (bottom panels) and were then processed for immunofluorescence staining with anti-FLAG antibody (red) without (left panels) or with (right panels) membrane permeabilization. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bars, 20 μm. (C) HeLa cells transfected with zFxyd11a-FLAG were lysed directly (Control) or were subjected to cell-surface biotinylation (Biotinylated). Whole cell lysates (left panels) and biotinylated samples (right panels) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-FLAG antibody (top panels) and anti-DRP1 antibody (bottom panels).

Discussion

A number of studies have demonstrated that MRCs play a crucial role in ion and osmotic regulation in teleost FW fish (Marshall, 2002; Hirose et al., 2003; Perry et al., 2003; Kirschner, 2004; Evans et al., 2005; Hwang, 2009). Although it is evident that active ion transport of MRCs as well as other ion-transporting epithelial cells is coupled to Na+–K+-ATPase, the regulatory mechanism of Na+–K+-ATPase activity in MRCs remains to be clarified. Since the first fish FXYD was identified from shark rectal glands (Mahmmoud et al., 2000), the presence of teleost FXYD has been detected in osmoregulatory organs such as gills, intestine, and kidney (Tipsmark, 2008; Wang et al., 2008). A recent study has identified a euryhaline pufferfish FXYD protein (pFXYD) highly expressed in the gill MRCs, and has suggested its role in adaptation to environmental salinity changes (Wang et al., 2008). In the present study, we identified an additional FXYD that is likely to modulate Na+–K+-ATPase activity in the gill and skin MRCs of the FW fish zebrafish.

As reported by Tipsmark (2008), there are at least eight fxyd genes in the zebrafish database. Among them, we identified, by RT-PCR experiments using multiple tissue total RNA, zfxyd11 as a gill-specific isoform (Figure 1A). We confirmed zfxyd11 mRNA expression in the secondary gill lamella of adult zebrafish by in situ hybridization (Figure 3). Tipsmark (2008) has reported that Atlantic salmon fxyd11, a homolog of zfxyd11, also shows a gill-specific expression, suggesting that the fxyd11 isoform likely has a conserved function in the gills of teleost fish. Since expression of other fxyd isoforms (i.e., zfxyd7, zfxyd8, and zfxyd9) was detected in, but not restricted to, the gills (Figure 1A), we cannot exclude their possible involvement in the gill function. The RT-PCR experiments also revealed that the zfxyd11 gene generates two variant transcripts, zfxyd11a and zfxyd11b, by alternative splicing, which differ in their C-terminal length (Figure 1B). Immunofluorescence microscopy and cell-surface biotinylation analyses demonstrated that zFxyd11a-FLAG was localized to the plasma membrane in mammalian cultured cells (Figures 8B,C). In addition, zFxyd11a-FLAG was found to be an integral membrane protein extruding its C-terminal tail in the cytoplasm (Figures 8A,B), which is consistent with a typical membrane topology seen in mammalian FXYD proteins (Geering, 2006). zFxyd11b lacks the eight most C-terminal residues of zFxyd11a, and its C-terminal sequence matches the endoplasmic reticulum retention signal (-K-X-K). It is possible that zFxyd11b might be localized to the endoplasmic reticulum, as is seen for mammalian FXYD1 (PLM), which has been shown to be retained in the endoplasmic reticulum by a C-terminal -R-X-R motif in Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (Lansbery et al., 2006). A phylogenetic tree analysis indicated that zFxyd11 is related to human FXYD3 and FXYD4 (Tipsmark, 2008), even though zFxyd11 shows distant sequence identities to them (32.2% for FXYD3 and 26.6% for FXYD4). Mammals have two FXYD3 splice isoforms with distinct modulatory roles: the short isoform decreases the apparent affinities for intracellular Na+ and extracellular K+ of Na+–K+-ATPase (Crambert et al., 2005; Bibert et al., 2006) whereas the long one decreases the apparent K+ affinity in a voltage-dependent manner and increases the apparent Na+ affinity (Bibert, et al., 2006). FXYD4 increases the apparent affinity for intracellular Na+ of Na+–K+-ATPase (Béguin et al., 2001; Garty et al., 2002). The low homology and the diverse properties of the mammalian FXYD proteins make it difficult to predict the functional role of zFxyd11 in the regulation of Na+–K+-ATPase activity. We tried to determine the effect of zFxyd11 knockdown on the activity of Na+–K+-ATPase by using anthroylouabain, a fluorescence dye of ouabain, which has been used to detect the Na+–K+-ATPase activity in intact MRCs of tilapia (McCormick, 1990), but such an approach is so far unsuccessful in zebrafish larvae. The exact effect of zFxyd11 interaction on the kinetics of Na+–K+-ATPase activity should be elucidated in future investigations.

Immunohistochemical analyses by using a specific polyclonal antibody revealed that zFxyd11 is abundantly expressed in NaK-MRCs of the larval skin and the adult gills (Figures 4 and 5, and Figure S1 in Supplementary Material). Moreover, by using in situ PLA assay, we demonstrated a physical association between zFxyd11 and Na+–K+-ATPase α subunit in NaK-MRCs (Figure 6). Taking into account the recent report by Wang et al. (2009) that the NCC cells, the third population of MRCs, are not stained with anti-Na+–K+-ATPase antibody, zFxyd11 is unlikely to be highly expressed in NCC cells as in the case of vH-MRCs. The abundance of zFxyd11 reasonably reflects the high expression and activity of Na+–K+-ATPase in NaK-MRCs. The gill and skin NaK-MRCs have been proposed to be responsible for active Ca2+ uptake via a set of Ca2+ channels and transporters to maintain calcium homeostasis (Pan et al., 2005; Craig et al., 2007; Liao et al., 2007, 2009; Tseng et al., 2009). The current model of transepithelial Ca2+ transport in mammalian kidney involves apical Ca2+ entry via epithelial Ca2+ channels (TRPV5 and TRPV6, also known as ECaC1 and ECaC2, respectively) and basolateral exit mediated by an Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX1) and a Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA1b) (Hoenderop et al., 2005). By analogy to this model, the following mechanism for Ca2+ uptake at zebrafish gills is postulated: environmental Ca2+ ions are absorbed into NaK-MRCs through the apical Ca2+ channel zECaC (Pan et al., 2005) and extruded to the blood by basolateral Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX1b) and/or Ca2+ pump (zPMCA2) (Liao et al., 2007). In this Ca2+ transporting pathway, Na+–K+-ATPase is implicated in generating a Na+ gradient across basolateral membrane that drives the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. It has been shown that the Na+–K+-ATPase α-subunit isozyme zatp1a1a.1 is specifically expressed in the gill MRCs and its expression, as well as zecac/zECaC expression, is upregulated by low environmental Ca2+ (Liao et al., 2009). We observed a salinity-dependent regulation of zfxyd11 mRNA levels in the whole larvae and adult gills, in which it was increased by low ionic strength (Figures 2B,D). Since Ca2+ ion concentration of the diluted FW we used was 3.2 μM, which is low enough to upregulate zecac and zatp1a1a.1 expression, zfxyd11 expression was likely affected in response to environmental Ca2+ levels. Our findings suggest that zFxyd11 may contribute to the regulation of the Ca2+ uptake pathway by modulating the transport properties of Na+–K+-ATPase. Pan et al. (2005) have investigated the developmental regulation of Ca2+ uptake in zebrafish and showed that Ca2+ influx begins to occur at 36-hpf and is greatly enhanced during the hatching period (48- to 72-dpf). They have also reported that zecac mRNA and Na+–K+-ATPase protein expression are first detectable at 24-hpf, and the number of zecac-expressing NaK-MRCs is gradually increased during development (Pan et al., 2005). These facts suggest that the Ca2+-transporting machinery is equipped in zebrafish embryos before hatching and its expression is controlled to meet the increased Ca2+ demand of development. In our RT-PCR experiments, zfxyd11 expression was detected at 24-hpf and subsequent developmental stages, which closely resembles the case of zecac expression (Figure 2A). This would be additional supporting evidence for a possible role of zFxyd11 in Ca2+ uptake. Perry and colleagues have demonstrated that the zebrafish Slc26 Cl−/HCO3− exchangers are expressed in a subset of NaK-MRCs of the gill and larval skin, and their knockdown causes a reduction of Cl− uptake in zebrafish larvae (Bayaa et al., 2009; Perry et al., 2009). Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that zFxyd11 might be involved in Cl− transport through NaK-MRCs.

Our interesting observation is that knockdown of zFxyd11 expression resulted in a significant increase in the number of Na+–K+-ATPase–positive cells in the larval skin (Figure 7). It has been reported that the number and density of the skin MRCs are affected by environmental ionic and pH conditions (Pan et al., 2005; Horng et al., 2009). In particular, cultivation of zebrafish embryos in low-Ca2+ FW increases the zecac-positive cells in the yolk sac skin (Pan et al., 2005), suggesting that proliferation and differentiation of NaK-MRCs accompany early embryonic development. The mechanism for MRC formation has recently been investigated and the factors involved have been identified and characterized. Both NaK-MRCs and vH-MRCs are derived from the same precursor cell in the epidermal epithelium, in which the Delta-Notch signaling pathway controls proliferation and distribution of MRC precursors, and the Foxi3a and Foxi3b transcription factors regulate following differentiation into individual MRCs (Hsiao et al., 2007; Jänicke et al., 2007; Esaki et al., 2009). After expression of foxi3a and foxi3b at 10-hpf, expression of atp1b1b, a β-subunit of Na+–K+-ATPase, becomes detectable around 14-hpf (Hsiao et al., 2007). Thus, it seems likely that the ion-transporting machinery is expressed after cell proliferation and determination of cell specificity. Knockdown of zFxyd11 expression is unlikely to affect proliferation and differentiation of MRC precursors since its mRNA expression initiates between 12 and 24-hpf (Figure 2A). Hence, the following speculation could be put forward for the mechanism of the effects of zFxyd11 knockdown: there is a subpopulation of MRCs expressing Na+–K+-ATPase and zFxyd11 at very low levels, and loss of zFxyd11 causes a functional impairment of Na+–K+-ATPase and a subsequent decrease in ion-transporting ability of the cell, which leads to a feedback upregulation of Na+–K+-ATPase expression in the corresponding MRC population.

The localization, regulated expression, Na+–K+-ATPase interaction of zFxyd11 suggest its important role in zebrafish calcium homeostasis to allow proper development and to adapt changes of environmental ion concentrations. Other than NaK-MRCs, there are at least two populations of MRCs in zebrafish: vH-MRCs and NCC cells, which appear to be responsible for Na+ and Cl− ions, respectively. It has been shown that vH-MRCs and NCC cells specifically express different Na+–K+-ATPase α isozymes, zatp1a1a.5 and zatp1a1a.2, respectively, which raises the possibility that their enzymatic activities are modulated by distinct FXYD proteins. Characterization of localization and functions of other FXYD isoforms would provide insight with regard to body fluid and electrolyte homeostasis in FW fish.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1.

Localization of zFxyd11 in NaK-MRCs of the skin of zebrafish larvae. Immunofluorescence staining was performed on 2-dpf zebrafish larvae with anti-zFxyd11 antiserum [green in (A–D)], along with anti–Na+–K+-ATPase [red in (A), (B)] or anti–vH+-ATPase antiserum [red in (C), (D)]. Control staining was carried out with preimmune serum (E,F). Regions of the yolk sac (A,C,E) and the yolk sac extension and the trunk (B,D,F) are shown. Note that signals for zFxyd11 entirely overlap with NaK-MRCs on the skin of yolk, yolk extension, and trunk (A,B), and are not colocalized with vH-MRCs (C,D). Scale bars, 200 μm.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Atsushi Kawakami for providing the zebrafish TL line, Akira Kato, Taro Ichinose, and Tomoya Takahashi for their help in qPCR, Yoichi Noguchi and Kazuo Okubo of Genostaff for technical assistance in in situ hybridization histochemistry, and Keijiro Munakata, Tsutomu Nakada, Keiko Kawai, Noriko Isoyama, and Setsuko Sato for helpful suggestions and for technical and secretary assistance. This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (14104002, 18059010, 21026010, and 22370029) and for Young Scientists (20770156 and 22770123) and by the Global COE Programs of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

References

- Aizman R., Asher C., Fuzesi M., Latter H., Lonai P., Karlish S. J., Garty H. (2002). Generation and phenotypic analysis of CHIF knockout mice. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 283, F569–F577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arystarkhova E., Wetzel R. K., Asinovski N. K., Sweadner K. J. (1999). The gamma subunit modulates Na+ and K+ affinity of the renal Na,K-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 33183–33185 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayaa M., Vulesevic B., Esbaugh A., Braun M., Ekker M. E., Grosell M., Perry S. F. (2009). The involvement of SLC26 anion transporters in chloride uptake in zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 3283–3295 10.1242/jeb.033910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béguin P., Crambert G., Guennoun S., Garty H., Horisberger J. D., Geering K. (2001). CHIF, a member of the FXYD protein family, is a regulator of Na,K-ATPase distinct from the gamma-subunit. EMBO J. 20, 3993–4002 10.1093/emboj/20.15.3993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béguin P., Crambert G., Monnet-Tschudi F., Uldry M., Horisberger J. D., Garty H., Geering K. (2002). FXYD7 is a brain-specific regulator of Na,K-ATPase alpha 1-beta isozymes. EMBO J. 21, 3264–3273 10.1093/emboj/cdf330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béguin P., Wang X., Firsov D., Puoti A., Claeys D., Horisberger J. D., Geering K. (1997). The gamma subunit is a specific component of the Na,K-ATPase and modulates its transport function. EMBO J. 16, 4250–4260 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibert S., Roy S., Schaer D., Felley-Bosco E., Geering K. (2006). Structural and functional properties of two human FXYD3 (Mat-8) isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 39142–39151 10.1074/jbc.M605221200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig P. M., Wood C. M., McClelland G. B. (2007). Gill membrane remodeling with soft-water acclimation in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Physiol. Genomics 30, 53–60 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00195.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crambert G., Fuzesi M., Garty H., Karlish S., Geering K. (2002). Phospholemman (FXYD1) associates with Na,K-ATPase and regulates its transport properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 11476–11481 10.1073/pnas.182267299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crambert G., Li C., Claeys D., Geering K. (2005). FXYD3 (Mat-8), a new regulator of Na,K-ATPase. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 2363–2371 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delprat B., Schaer D., Roy S., Wang J., Puel J. L., Geering K. (2007). FXYD6 is a novel regulator of Na,K-ATPase expressed in the inner ear. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 7450–7456 10.1074/jbc.M609872200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esaki M., Hoshijima K., Kobayashi S., Fukuda H., Kawakami K., Hirose S. (2007). Visualization in zebrafish larvae of Na+ uptake in mitochondria-rich cells whose differentiation is dependent on foxi3a. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 292, R470–R480 10.1152/ajpregu.00200.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esaki M., Hoshijima K., Nakamura N., Munakata K., Tanaka M., Ookata K., Asakawa K., Kawakami K., Wang W., Weinberg E. S., Hirose S. (2009). Mechanism of development of ionocytes rich in vacuolar-type H+-ATPase in the skin of zebrafish larvae. Dev. Biol. 329, 116–129 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. H., Piermarini P. M., Choe K. P. (2005). The multifunctional fish gill: dominant site of gas exchange, osmoregulation, acid–base regulation, and excretion of nitrogenous waste. Physiol. Rev. 85, 97–177 10.1152/physrev.00050.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feraille E., Doucet A. (2001). Sodium–potassium-adenosinetriphosphatase-dependent sodium transport in the kidney: hormonal control. Physiol. Rev. 81, 345–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garty H., Lindzen M., Scanzano R., Aizman R., Fuzesi M., Goldshleger R., Farman N., Blostein R., Karlish S. J. (2002). A functional interaction between CHIF and Na–K-ATPase: implication for regulation by FXYD proteins. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 283, F607–F615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geering K. (2001). The functional role of beta subunits in oligomeric P-type ATPases. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 33, 425–438 10.1023/A:1010623724749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geering K. (2006). FXYD proteins: new regulators of Na–K-ATPase. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 290, F241–F250 10.1152/ajprenal.00126.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschimdt I., Grahammer F., Warth R., Schulz-Baldes A., Garty H., Greger R., Bleich M. (2004). Kidney and colon electrolyte transport in CHIF knockout mice. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 14, 113–120 10.1159/000076932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata T., Kaneko T., Ono T., Nakazato T., Furukawa N., Hasegawa S., Wakabayashi S., Shigekawa M., Chang M. H., Romero M. F., Hirose S. (2003). Mechanism of acid adaptation of a fish living in a pH 3.5 lake. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 284, R1199–R1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose S., Kaneko T., Naito N., Takei Y. (2003). Molecular biology of major components of chloride cells. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 136, 593–620 10.1016/S1096-4959(03)00287-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenderop J. G., Nilius B., Bindels R. J. (2005). Calcium absorption across epithelia. Physiol. Rev. 85, 373–422 10.1152/physrev.00003.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horng J. L., Lin L. Y., Huang C. J., Katoh F., Kaneko T., Hwang P. P. (2007). Knockdown of V-ATPase subunit A (atp6v1a) impairs acid secretion and ion balance in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 292, R2068–R2076 10.1152/ajpregu.00578.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horng J. L., Lin L. Y., Hwang P. P. (2009). Functional regulation of H+-ATPase-rich cells in zebrafish embryos acclimated to an acidic environment. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 296, C682–C692 10.1152/ajpcell.00576.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshijima K., Hirose S. (2007). Expression of endocrine genes in zebrafish larvae in response to environmental salinity. J. Endocrinol. 193, 481–491 10.1677/JOE-07-0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao C. D., You M. S., Guh Y. J., Ma M., Jiang Y. J., Hwang P. P. (2007). A positive regulatory loop between foxi3a and foxi3b is essential for specification and differentiation of zebrafish epidermal ionocytes. PLoS ONE 2, e302. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000302. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang P. P. (2009). Ion uptake and acid secretion in zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Exp. Biol. 212, 1745–1752 10.1242/jeb.026054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jänicke M., Carney T. J., Hammerschmidt M. (2007). Foxi3 transcription factors and Notch signaling control the formation of skin ionocytes from epidermal precursors of the zebrafish embryo. Dev. Biol. 307, 258–271 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.04.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L. G., Donnet C., Bogaev R. C., Blatt R. J., McKinney C. E., Day K. H., Berr S. S., Jones L. R., Moorman J. R., Sweadner K. J., Tucker A. L. (2005). Hypertrophy, increased ejection fraction, and reduced Na–K-ATPase activity in phospholemman-deficient mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 288, H1982–H1988 10.1152/ajpheart.00142.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. H., Li T. Y., Arystarkhova E., Barr K. J., Wetzel R. K., Peng J., Markham K., Sweadner K. J., Fong G. H., Kidder G. M. (2005). Na,K-ATPase from mice lacking the γ subunit (FXYD2) exhibits altered Na+ affinity and decreased thermal stability. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 19003–19011 10.1074/jbc.M500697200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner L. B. (2004). The mechanism of sodium chloride uptake in hyperregulating aquatic animals. J. Exp. Biol. 207, 1439–1452 10.1242/jeb.00907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansbery K. L., Burcea L. C., Mendenhall M. L., Mercer R. W. (2006). Cytoplasmic targeting signals mediate delivery of phospholemman to the plasma membrane. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 290, C1275–R1286 10.1152/ajpcell.00110.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao B. K., Chen R. D., Hwang P. P. (2009). Expression regulation of Na+–K+-ATPase α1-subunit subtypes in zebrafish gill ionocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 296, R1897–R1906 10.1152/ajpregu.00029.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao B. K., Deng A. N., Chen S. C., Chou M. Y., Hwang P. P. (2007). Expression and water calcium dependence of calcium transporter isoforms in zebrafish gill mitochondrion-rich cells. BMC Genomics 8, 354. 10.1186/1471-2164-8-354. 10.1186/1471-2164-8-354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L. Y., Horng J. L., Kunkel J. G., Hwang P. P. (2006). Proton pump-rich cell secretes acid in skin of zebrafish larvae. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 290, C371–C378 10.1152/ajpcell.00281.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T. Y., Liao B. K., Horng J. L., Yan J. J., Hsiao C. D., Hwang P. P. (2008). Carbonic anhydrase 2-like a and 15a are involved in acid-base regulation and Na+ uptake in zebrafish H+-ATPase-rich cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 294, C1250–R1260 10.1152/ajpcell.00021.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmmoud Y. A., Cramb G., Maunsbach A. B., Cutler C. P., Meischke L., Cornelius F. (2003). Regulation of Na,K-ATPase by PLMS, the phospholemman-like protein from shark: molecular cloning, sequence, expression, cellular distribution, and functional effects of PLMS. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 37427–37438 10.1074/jbc.M305126200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmmoud Y. A., Vorum H., Cornelius F. (2000). Identification of a phospholemman-like protein from shark rectal glands. Evidence for indirect regulation of Na,K-ATPase by protein kinase c via a novel member of the FXYDY family. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35969–35977 10.1074/jbc.M005168200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W. S. (2002). Na+, Cl−, Ca2+ and Zn2+ transport by fish gills: retrospective review and prospective synthesis. J. Exp. Zool. 293, 264–283 10.1002/jez.10127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick S. D. (1990). Fluorescent labelling of Na+, K+-ATPase in intact cells by use of a fluorescent derivative of ouabain: salinity and teleost chloride cells. Cell Tissue Res. 260, 529–533 10.1007/BF00297233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meij I. C., Koenderink J. B., van Bokhoven H., Assink K. F., Groenestege W. T., de Pont J. J., Bindels R. J., Monnens L. A., van den Heuvel L. P., Knoers N. V. (2000). Dominant isolated renal magnesium loss is caused by misrouting of the Na+, K+-ATPase γ-subunit. Nat. Genet. 26, 265–266 10.1038/81543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza M. A., Zhang X. Q., Ahlers B. A., Qureshi A., Carl L. L., Song J., Tucker A. L., Mounsey J. P., Moorman J. R., Rothblum L. I., Zhang T. S., Cheung J. Y. (2004). Effects of phospholemman downregulation on contractility and [Ca2+]i transients in adult rat cardiac myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 286, H1322–H1330 10.1152/ajpheart.00997.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto K., Nakamura N., Kashiwagi M., Honda S., Kato A., Hasegawa S., Takei Y., Hirose S. (2002). RING finger, B-box, and coiled-coil (RBCC) protein expression in branchial epithelial cells of Japanese eel, Anguilla japonica. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 6152–6161 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada T., Hoshijima K., Esaki M., Nagayoshi S., Kawakami K., Hirose S. (2007). Localization of ammonia transporter Rhcg1 in mitochondrion-rich cells of yolk sac, gill, and kidney of zebrafish and its ionic strength-dependent expression. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 293, R1743–R1753 10.1152/ajpregu.00248.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N., Fukuda H., Kato A., Hirose S. (2005). MARCH-II is a syntaxin-6-binding protein involved in endosomal trafficking. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 1696–1710 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N., Hirose S. (2008). Regulation of mitochondrial morphology by USP30, a deubiquitinating enzyme present in the mitochondrial outer membrane. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 1903–1911 10.1091/mbc.E07-11-1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N., Suzuki Y., Sakuta H., Ookata K., Kawahara K., Hirose S. (1999). Inwardly rectifying K+ channel Kir7.1 is highly expressed in thyroid follicular cells, intestinal epithelial cells and choroid plexus epithelial cells: implication for a functional coupling with Na+, K+-ATPase. Biochem. J. 342, 329–336 10.1042/0264-6021:3420329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan T. C., Liao B. K., Huang C. J., Lin L. Y., Hwang P. P. (2005). Epithelial Ca2+ channel expression and Ca2+ uptake in developing zebrafish. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 289, R1202–R1211 10.1152/ajpregu.00816.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry S. F., Shahsavarani A., Georgalis T., Bayaa M., Furimsky M., Thomas S. L. (2003). Channels, pumps, and exchangers in the gill and kidney of freshwater fishes: their role in ionic and acid–base regulation. J. Exp. Zool. A Comp. Exp. Biol. 300, 53–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry S. F., Vulesevic B., Grosell M., Bayaa M. (2009). Evidence that SLC26 anion transporters mediate branchial chloride uptake in adult zebrafish (Danio rerio). Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 297, R988–R997 10.1152/ajpregu.00327.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu H. X., Cluzeaud F., Goldshleger R., Karlish S. J., Farman N., Blostein R. (2001). Functional role and immunocytochemical localization of the γa and γb forms of the Na,K-ATPase γ subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 20370–20378 10.1074/jbc.M010836200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu H. X., Scanzano R., Blostein R. (2002). Distinct regulatory effects of the Na,K-ATPase γ subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 20270–20276 10.1074/jbc.M201009200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinoda T., Ogawa H., Cornelius F., Toyoshima C. (2009). Crystal structure of the sodium-potassium pump at 2.4 Å resolution. Nature 459, 446–450 10.1038/nature07939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderberg O., Leuchowius K. J., Gullberg M., Jarvius M., Weibrecht I., Larsson L. G., Landegren U. (2008). Characterizing proteins and their interactions in cells and tissues using the in situ proximity ligation assay. Methods 45, 227–232 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweadner K. J., Rael E. (2000). The FXYD gene family of small ion transport regulators or channels: cDNA sequence, protein signature sequence, and expression. Genomics 68, 41–56 10.1006/geno.2000.6274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therien A. G., Blostein R. (2000). Mechanisms of sodium pump regulation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 279, C541–C566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipsmark C. K. (2008). Identification of FXYD protein genes in a teleost: tissue-specific expression and response to salinity change. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 294, R1367–R1378 10.1152/ajpregu.00454.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran Y. H., Xu Z., Kato A., Mistry A. C., Goya Y., Taira M., Brandt S. J., Hirose S. (2006). Spliced isoforms of LIM-domain-binding protein (CLIM/NLI/Ldb) lacking the LIM-interaction domain. J. Biochem. 140, 105–119 10.1093/jb/mvj134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng D. Y., Chou M. Y., Tseng Y. C., Hsiao C. D., Huang C. J., Kaneko T., Hwang P. P. (2009). Effects of stanniocalcin 1 on calcium uptake in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryo. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 296, R549–R557 10.1152/ajpregu.90742.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. J., Lin C. H., Hwang H. H., Lee T. H. (2008). Branchial FXYD protein expression in response to salinity change and its interaction with Na+/K+-ATPase of the euryhaline teleost Tetraodon nigroviridis. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 3750–3758 10.1242/jeb.018440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. F., Tseng Y. C., Yan J. J., Hiroi J., Hwang P. P. (2009). Role of SLC12A10.2, a Na-Cl cotransporter-like protein, in a Cl uptake mechanism in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 296, R1650–R1660 10.1152/ajpregu.00119.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. (1995). The Zebrafish Book: A Guide to the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Press [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Wong S. H., Tang B. L., Subramaniam V. N., Zhang T., Hong W. (1998). A 29-kilodalton Golgi soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (Vti1-rp2) implicated in protein trafficking in the secretory pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 21783–21789 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J. J., Chou M. Y., Kaneko T., Hwang P. P. (2007). Gene expression of Na+/H+ exchanger in zebrafish H+-ATPase-rich cells during acclimation to low-Na+ and acidic environments. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 293, C1814–C1823 10.1152/ajpcell.00358.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Y., Pitts K. R., Dahan S., McNiven M. A. (1998). A novel dynamin-like protein associates with cytoplasmic vesicles and tubules of the endoplasmic reticulum in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 140, 779–793 10.1083/jcb.140.4.779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. Q., Qureshi A., Song J., Carl L. L., Tian Q., Stahl R. C., Carey D. J., Rothblum L. I., Cheung J. Y. (2003). Phospholemman modulates Na+/Ca2+ exchange in adult rat cardiac myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 284, H225–H233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]