Abstract

The Mt. Desert Island Biological Laboratory (MDIBL) has played a central role in the study of fish osmoregulation for the past 80 years. In particular, scientists at the MDIBL have made significant discoveries in the basic pattern of fish osmoregulation, the function of aglomerular kidneys and proximal tubular secretion, the roles of NaCl cotransporters in intestinal uptake and gill and rectal gland secretion, the role of the shark rectal gland in osmoregulation, the mechanisms of salt secretion by the teleost fish gill epithelium, and the evolution of the ionic uptake mechanisms in fish gills. This short review presents the history of these discoveries and their relationships to the study of epithelial transport in general.

Keywords: fish osmoregulation, kidney, gill, epithelial transport

Introduction

In 1921, the Harpswell Laboratory, which housed Tufts University's Summer School of Biology, moved to Mt. Desert Island, ME from South Harpswell, ME, where it had been functioning as a teaching and research laboratory since 1898. The property in Salisbury Cove had been purchased by the Wild Gardens of Acadia, a group of philanthropists led by George Dorr, who was instrumental in establishing much of Mt. Desert Island as the Acadia National Park. The relocated laboratory, called the Mt. Desert Island Biological Laboratory (MDIBL) after 1923, consisted of a single, two-story teaching laboratory that was modeled after the main building at Harpswell. Undergraduate courses continued to be taught at the MDIBL in its early years, but by the late 1920s, much of the teaching mission of the MDIBL had been replaced by research groups that were attracted to the local marine species, the scientific collegiality, and Maine island ambience. Thus, began over 80 years of research on various aspects of comparative physiology that has brought together collaborative researchers from various biomedical and biological departments throughout the US and overseas1. The intent of this review is to describe the history of six areas of research that have been important in the study of fish osmoregulation and epithelial transport in general. In each case, the research at the MDIBL has been central to what is presently known.

The Basic Pattern of Marine Fish Osmoregulation2

By the late 1920s, it was known that marine teleost fishes were hypotonic to their surrounding seawater and could not produce urine more concentrated than the plasma (reviewed in Evans, 2008). There was some suggestion that marine teleosts might ingest the medium, because fluid was often found in the intestine (Smith, 1930), but the suite of homeostatic mechanisms that teleosts employ in osmoregulation was unknown. Homer Smith studied the American eel (Anguilla rostrata) in his NYU lab and the sculpin (Myoxocephalus sp.) and goosefish (Lophius sp.) at the MDIBL. Using the volume marker phenol red, he demonstrated that both the sculpin and the eel ingested seawater, and, since the phenol red was concentrated in the gut, it was clear that the intestinal epithelium absorbed much of the ingested water. Since ligation of the pylorus abolished the appearance of phenol red in the intestine, it was settled that the intestinal dye entered the fish via the mouth, not by diffusion across the gills. Smith calculated that approximately 90% of the ingested fluid was excreted extrarenally, but he appeared to be unaware of the fact that the osmotic gradient across the gills would favor the osmotic withdrawal of water from the fish across the thin epithelium. By sampling gut fluids at various sites along the intestine, Smith found that the Mg2+ and concentrations increased far above the level of even the surrounding seawater. The total osmolarity, however, decreased along the intestine (reaching approximate isotonicity with the fish plasma), suggesting that NaCl was absorbed in addition to water.

Importantly, Smith also confirmed early studies that the urine was “invariably” isotonic or even hypotonic to the plasma, and that, like the intestinal fluids, the urine contained high concentrations of Mg2+ and . It is interesting to note that Smith observed that the “osmotic pressure and inorganic composition” of the urine in the goosefish (“possesses a purely tubular kidney”) was similar to that found in the eel and sculpin, both of which have glomerular kidneys. He concluded: “the osmotic pressure and inorganic composition of normal urine is not significantly dependent on the pressure or absence of glomeruli (Smith, 1930).” Since the NaCl concentration was relatively low in both intestinal fluids and urine, Smith concluded that extrarenal secretory mechanisms must exist, and suggested that the gills are the most likely site of extrarenal NaCl secretion. Thus, in a single publication, Smith proposed the basic outline of marine teleost fish osmoregulation: ingestion of seawater, retrieval of NaCl (and some Mg2+ and ) and water from the intestine, followed by excretion of the divalents via the urine, and the monovalents across the gills.

During this same period, Smith (1931) also worked out some of the osmoregulatory strategies of marine elasmobranchs. Using elasmobranch species available near the MDIBL, as well as some from the New York Aquarium, Smith confirmed that marine elasmobranch plasma was actually slightly hypertonic to seawater, and that the urine was usually hypotonic to the plasma. Thus, the elasmobranchs actually gain some water osmotically, which is balanced by the excretion of hypotonic urine. Smith also confirmed that the hypertonicity of the plasma was primarily the result of substantial concentrations of urea, which were maintained by urea reabsorption in the kidney. He also suggested that in marine elasmobranchs, like marine teleosts, the gills were the site of extrarenal excretion of NaCl. The function of the rectal gland was not discovered until 1960, at the MDIBL; nevertheless, most of the basic strategies of marine elasmobranch osmoregulation had been worked out by Smith (Figure 1).

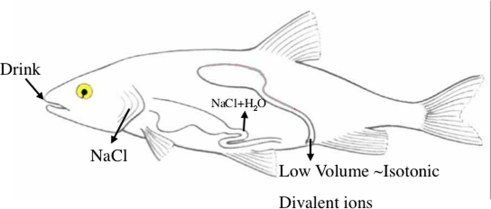

Figure 1.

Basic pattern of marine teleost osmoregulation. To offset the osmotic loss of water across the gill epithelium, the fish ingests seawater and absorbs NaCl and water across the esophageal and intestinal epithelium. Urinary water loss is kept to a minimum by production of a low volume of urine that is isotonic to the plasma, but contains higher concentrations of divalent ions than the plasma. Excess NaCl is excreted across the gill epithelium. Redrawn from Evans (2008).

Aglomerular Kidneys and Proximal Tubular Secretion

E. K. Marshall came from Johns Hopkins to the MDIBL in the summer of 1926, because he was interested in proving his theories about renal tubular secretion by using the aglomerular goosefish, Lophius piscatorius. Working with Homer Smith3, Marshall measured the diameter of the renal corpuscle (glomerulus plus Bowman's capsule) in a variety of marine and freshwater teleosts. The corpuscles of freshwater fishes (e.g., carp, goldfish, trout, and perch) ranged from 60 to 106 μm in diameter, and those of glomerular marine teleosts (e.g., sculpin, sea bass, cod, haddock, and flounder) ranged from 35 to 81 μm. Sixteen species (such as pipefish, seahorse, toadfish4, and goosefish) were found to have no renal corpuscles (Marshall and Smith, 1930). Marshall also demonstrated that the urine flows he measured in the goosefish and toadfish were of the same order as those measured in glomerular, marine teleosts, such as the sculpin. In addition, his measurements of urine ionic (Cl−, Mg2+, ) and organic (urea and creatinine) constituents found no differences between glomerular and aglomerular species. Marshall concluded: “The present study proves unquestionably that the renal tubule can be excretory as well as reabsorptive in its function: that it can pass substances from the blood and lymph across the tubule into its lumen (Marshall, 1930).”

James Shannon (who worked in the Smith lab at NYU and MDIBL, and who later became the first Director of the NIH) invited Roy Forster to come to MDIBL in the summer of 1937. Nearly 40 years later, at his retirement dinner (Forster, 1977), Forster talked about his amazement on the first day in Shannon's lab, when E. K. Marshall and Homer Smith both appeared. Forster initially used clearance techniques to study glomerular function, secretion, and reabsorption in the amphibian kidney, and also studied renal hemodynamics in rabbits. After WWII, Forster became interested in studying tubular secretion more directly by examining thin slices of kidney tissue, or isolated renal tubules using a technique that had been described earlier for the chicken kidney (Chambers and Kempton, 1933). His initial experiments demonstrated that functional tubules could be isolated from a variety of fish species (e.g., founder, killifish, and sculpin), but flounder tubules were the basis for much of the study. These tubules could concentrate phenol red to nearly 4000× that in the perfusate, and this secretion could be inhibited by cold, anoxia, cyanide, azide, dinitrophenol, and mercury (Forster and Taggart, 1950), demonstrating the energy requirements of this secretory process. More recently, this technique has been used to study the mechanisms and control of transport of various organic molecules across the flounder and killifish proximal tubules (e.g., Miller, 2002).

Using the isolated, perfused proximal tubule techniques first worked out in rabbit nephrons (Burg et al., 1966), and also used with flounder tubules at the MDIBL (Burg and Weller, 1969), Klaus Beyenbach and colleagues studied the role of proximal tubular salt and water secretion in fish renal function at the MDIBL during the 1980s and early 1990s. The initial studies demonstrated that the proximal tubule of the shark, Squalus acanthias, secreted Cl− into the lumen of the perfused tubule, against the electrochemical gradient, with basolateral uptake possibly via a furosemide-sensitive NaCl cotransport carrier (Beyenbach and Fromter, 1985). A subsequent study showed that the shark tubule could produce a furosemide-sensitive, net secretion of fluid that was slightly hypertonic to the peritubular fluid, but contained primarily Na+ and Cl−, at concentrations equivalent to the peritubular fluid. They proposed that the driving force for fluid secretion in the shark proximal tubule was basolateral entry of NaCl via a furosemide-sensitive cotransporter, followed by apical extrusion of Cl− via a Cl− channel, with Na+ following via a paracellular pathway (Sawyer and Beyenbach, 1985). Interestingly, similar studies on the perfused flounder tubule found that the secreted fluid contained significantly more Cl− than the peritubular bath, but that the Mg2+ and concentrations were 10-fold enriched, suggesting these divalent ions as the driving force (Beyenbach et al., 1986). This hypothesis was confirmed in an accompanying study that showed that fluid secretion was dependent upon both peritubular Mg2+ and Na+, suggesting dual driving forces: MgCl2 and NaCl secretion (Cliff et al., 1986). These studies, and many others on various aspects of proximal tubular secretion at the MDIBL and elsewhere, have been reviewed relatively recently by Beyenbach (2004), and Grantham and Wallace have reviewed the importance of proximal tubular secretion in mammalian renal function (Grantham and Wallace, 2002). Both conclude that, in addition to the secretion of unwanted toxins, proximal secretion of ions and water plays a significant role in total renal ion and water balance throughout the vertebrates, including mammals. In fact, Beyenbach calculated that proximal tubular fluid secretion may approach 300% of the glomerular filtration rate in marine fishes and 5% in humans (Beyenbach, 2004), which may become critically important during acute renal failure (Grantham and Wallace, 2002).

The NaCl Cotransporters5

Na+ + Cl− cotransport

A electroneutral NaCl cotransport system was first suggested by Jared Diamond6, who worked on the freshwater fish (roach) gallbladder at Cambridge University. He found that both Na+ and Cl− were actively transported, but the low transepithelial electrical potentials indicated that their transport was “on the same carrier molecules (Diamond, 1962).” We now know, however, that the transport of NaCl across the vertebrate gallbladder is not chemically coupled, but rather via parallel Na+/H+ and Cl−/ exchangers (Reuss et al., 1991). Larry Renfro came to the MDIBL in the early 1970s, as Bodil Schmidt-Nielsen's7 postdoc and studied NaCl transport across the flounder urinary bladder, which, unlike the toad bladder, is a mesodermal derivative of the mesonephric ducts, and therefore can be treated as an extension of the distal kidney. Renfro found that the perfused bladder reabsorbed Na+ and Cl− at the same rate, and the transepithelial potential was <5 mV, lumen fluids positive. Moreover, the transepithelial fluxes of both ion were relatively unaffected by clamping the voltage across the bladder at zero or ±50 mV. Both ouabain and furosemide inhibited Na+, Cl−, and water movement across the bladder. Renfro concluded that “in addition to the fact that both Na+ and Cl− appear to be actively transported, their movements through the epithelial membranes indicated that they are linked (Renfro, 1975).” David Dawson came to the MDIBL in the summer of 1979 to study this system further, using isolated sheets of bladder in an Using chamber. He confirmed that the short-circuit current (Isc) and net uptakes of Na+and Cl− were equivalent, and inhibited by ouabain (Dawson and Andrew, 1979). John Stokes came the next summer to attempt to differentiate between three possible mechanisms for this electroneutral NaCl absorption by the flounder urinary bladder: Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransport, parallel Na+/H+ and Cl−/OH− exchanges, and simple Na+ + Cl− cotransport. He confirmed that the uptakes of either Na+ or Cl− were dependent upon the other ion in the bathing solution, but not on the presence of K+. The Isc was unaffected by amiloride, DIDS or acetazolamide, suggesting that parallel exchangers were unlikely. Ouabain inhibited the uptake much more than furosemide or bumetanide did, but hydrochlorothiazide inhibited the Isc even more significantly, in a concentration-dependent manner, and completely inhibited the uptake of Na+. Stokes concluded: “The mechanism of NaCl absorption in this tissue appears to be a simple interdependent process. Its inhibition by thiazide diuretics appears to be a unique feature”. Stokes proposed that the flounder bladder “may be a model for NaCl absorption in the distal renal tubule (Stokes, 1984).” Subsequently, Steve Hebert's group used cDNA from flounder bladders they had harvested at the MDIBL (and at the MBL, Woods Hole) to clone and sequence this thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransporter (Gamba et al., 1993), which is now termed NaCl cotransporter (NCC), and is a product of the SLC12 gene family (SLC12A3) (Hebert et al., 2004). Subsequent studies, however, by Renfro on the winter flounder urinary bladder (Renfro, 1977) suggested that approximately 25% of the NaCl uptake was via Na+/H+ and Cl−/ exchangers, and this was confirmed in another flounder species (Demarest, 1984). More recently, studies using urinary bladders from freshwater, salmonid species have corroborated this suggestion that luminal Na+/H+ and Cl−/ exchangers, rather than Na+ + Cl− cotransport, accounts for NaCl uptake (Marshall, 1986; Burgess et al., 2000). Thus, it appears that the urinary bladder of fishes extracts NaCl from the lumen via both NCC and parallel Na+/H+ and Cl−/ exchangers.

Na+ + K+ + 2Cl− cotransport

Working with Bill Kinter at the MDIBL in the mid-1970s, Michael Field and collaborators showed that the flounder intestine absorbed both Na+ and Cl−, but that the uptake of Cl− was abolished by replacing the mucosal Na+ with choline, as was the uptake of Na+ when Cl− was replaced by Moreover, Cl− uptake was inhibited by the addition of ouabain. The authors proposed that the mucosal uptake of NaCl was coupled 1:1 (Field et al., 1978). Field invited Ray Frizzell to the MDIBL in the summer of 1977 to work on the flounder intestine, and they confirmed that mucosal NaCl uptake was dependent upon both Na+ and Cl− in the luminal solution and inhibited by furosemide. Ionic replacement and furosemide inhibition had equivalent effects on both ion fluxes, confirming that the NaCl coupling was probably 1:1 (Frizzell et al., 1979b). These, and many other studies on a variety of NaCl absorbing tissues in the vertebrates (e.g., mammalian ileum, gallbladder, and colon; amphibian proximal renal tubule, intestine, and skin), were reviewed by Frizzell (1979a). As the authors pointed out, this NaCl coupled uptake is characteristic of “leaky epithelia,” which possess relatively low-resistance, paracellular pathways, and was driven by Na+/K+ exchange on the serosal membrane, which maintained intracellular Na+ concentrations low. They also suggested that the flounder intestine might be a good model for the thick ascending limb in the mammalian kidney (Frizzell et al., 1981).

The role of mucosal K+ in this mucosal, furosemide-sensitive NaCl uptake by the flounder intestine was not appreciated until Field's group (Musch et al., 1982) demonstrated that this uptake by the flounder intestine was dependent upon mucosal K+. In addition, K+ uptake (measured by 86Rubidium) was dependent upon both Na+ and Cl− in the mucosal solution, and was inhibited by furosemide. They proposed that the NaCl uptake cotransporter on the flounder intestine mucosal membrane was actually a Na+ + K+ + Cl− carrier (actually Na+ + K+ + 2Cl−), similar to that being described for the erythrocyte (Haas et al., 1982), the MDCK cell line (McRoberts et al., 1982), and the ascending limb of the loop of Henle (Greger and Schlatter, 1981). This carrier has now been localized to the luminal membrane in the intestine of various species (Suvitayavat et al., 1994; Marshall et al., 2002; Lorin-Nebel et al., 2006; Cutler and Cramb, 2008), and Biff Forbush's group at the MDIBL has cloned an NKCC2 and localized the transcript to intestinal tissue in the killifish (Djurisic et al., 2003). Presumably, it is a product of the SLC12 gene family (SLC12A1) (Hebert et al., 2004). Interestingly, mammalian intestinal NaCl uptake is thought to be via parallel Na+/H+ (NHE2 and NHE3) and Cl−/ (AE4, DRA, and PAT1) exchangers (Venkatasubramanian et al., 2010)8. In addition, more recent evidence suggests that some Cl− uptake by the fish intestine is, in fact, via Cl−/ exchange (Marshall and Grosell, 2006; Grosell and Taylor, 2007). Indeed, the Cl−/ exchanger provides for the precipitation of intestinal Ca2+ and may actually play an important role in the ocean's inorganic carbon cycle (Tsui et al., 2009). In addition, basolateral and apical H+-pumps, as well as a basolateral Na+/H+ exchanger, K+ + Cl− cotransporter, Cl− channel, and a Na + HCO3 cotransporter (NBC1) have been described for fish intestine (Halm et al., 1985; Loretz and Fourtner, 1988; Grosell et al., 2009; Taylor et al., 2010) (Figure 2).

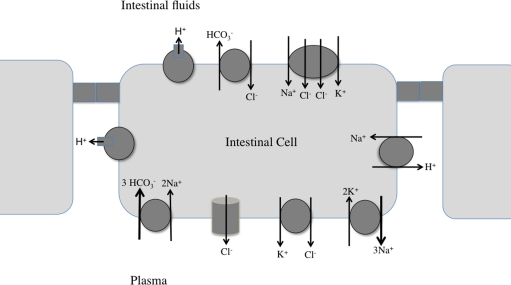

Figure 2.

Working model for NaCl uptake and bicarbonate secretion by the fish intestine. Three intestinal cells, with connecting tight junctions are shown. See text, as well as recent reviews (Grosell, 2006; Marshall and Grosell, 2006; Grosell et al., 2009) for details.

The Shark Rectal Gland9

As mentioned above, Homer Smith determined that elasmobranchs must have extrarenal mechanisms for salt extrusion, and suggested that possibly the gills were the site of this transport. Wendell Burger's work at the MDIBL in the early 1960s provided the first suggestion that the rectal gland was, in fact, the site of extrarenal salt secretion. His initial study demonstrated that the rectal gland fluid was approximately isotonic to the plasma, but contained nearly twice as much NaCl (and even more than seawater!) and virtually no urea (Burger and Hess, 1960). Since extremely high concentrations of Na+, K+-ATPase had been found in the rectal gland of Squalus acanthias (Bonting, 1966) Lowell Hokin, responding to an invitation from Frank Epstein (see below) came to the MDIBL in the summers of 1971–1972 to harvest as many shark rectal glands as possible. The result was the most complete purification (66–95%, depending on the calculated molecular weight of the putative protein) of Na+, K+-ATPase to date. Within 2 years, Hokin and Shirley Hilden had produced vesicles from the shark rectal gland containing >90% pure Na+, K+-ATPase, which could mediate the 3:2 exchange of K+ for Na+ (Hilden and Hokin, 1975).

Study of the actual transport mechanisms that produce the secretion of the rectal gland was initiated when John Hayslett's group came to the MDIBL in the summer of 1973 and perfected the first perfusion of the isolated gland from Squalus acanthias (Hayslett et al., 1974). They demonstrated that the perfused gland could secrete fluid at rates comparable to the intact gland, and that the glandular fluid contained about 50% more Na+ than the perfusion fluid. Measurement of the electrical potential between the secreted fluid and the perfusate showed that both Na+ and Cl− were secreted against their respective electrochemical gradients, but the gradient for Cl− was more than twice that for Na+ (Hayslett et al., 1974). In a subsequent study, Hayslett's group demonstrated more clearly that Cl− was secreted against a much steeper electrochemical gradient than Na+ and that Na+ secretion was dependent upon perfusate Cl− (Siegel et al., 1976).

Since these initial studies, this perfused gland preparation has been used (largely by Frank Epstein and colleagues at the MDIBL) to dissect both the transport steps and control mechanisms for NaCl secretion by the shark rectal gland. In the early studies of the perfused rectal gland, the perfusion rate often declined over time, so that some inhibitor studies were not possible. Working in Epstein's lab in the summer of 1976, Jeff Stoff discovered that the gland could be stimulated to maintain nearly constant perfusion rates for up to 60 min if theophylline and dibutyryl cyclic AMP were applied, suggesting that intracellular cyclic AMP levels was an important mediator of secretion (Silva et al., 1977b). The group also demonstrated that ouabain, furosemide, and substitution of perfusate Na+ with choline inhibited gland Cl− secretion significantly. Based upon these data, this group proposed a model for transepithelial transport mediated by a basolateral, linked NaCl carrier that was driven by the inward electrochemical gradient for Na+, which in turn was produced by and adjacent, basolateral Na+, K+-ATPase. Intracellular Cl− was thought to exit the apical membrane by some unknown Cl− carrier or channel, and Na+ moved through the paracellular pathway down its electrochemical gradient (Silva et al., 1977b). Along with a companion paper outlining a similar hypothesis for salt secretion by the teleost gill (Silva et al., 1977a, and see below), this was one of the first proposals for a NaCl coupled transporter driving salt secretion across an epithelium (Frizzell et al., 1979a). Work on the spiny dogfish rectal gland also generated the first antibodies for the Na+ + K+ + Cl− cotransporter (Lytle et al., 1992), and the first cloning and functional expression of a bumetanide-sensitive Na+ + K+ + Cl− cotransporter (Xu et al., 1994) by Biff Forbush's group at the MDIBL in 1992–1994. It is now known that this rectal gland Na+ + K++ + 2Cl− cotransporter is NKCC1, a product of the SLC12 gene family (SLC12A2; Hebert et al., 2004). The apical Cl− channel of the rectal gland displayed many of the electrical characteristics of the cystic fibrosus transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) when expressed in Xenopus oocytes by Mike Field's group (Sullivan et al., 1991) (not working at the MDIBL), and shark CFTR was cloned independently by two non-MDIBL groups (Grzelczak et al., 1990; Marshall et al., 1991). More recently, John Forrest's group at the MDIBL has cloned a K+ channel from the rectal gland, which presumably mediates basolateral cycling of K+ (Waldegger et al., 1999).

Subsequent studies at the MDIBL have produced a relatively good understanding of the myriad of physiological controls of the secretion by the rectal gland, and, by inference in some cases, putative controls of both the basolateral NKCC1 and the apical CFTR (e.g., Riordan et al., 1994; Hanrahan et al., 1996). Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) is a potent stimulant of rectal gland secretion (Stoff et al., 1979), as is atrial natriuretic peptide, by stimulation of VIP release (Silva et al., 1987). Subsequent work with cultured rectal gland tissue sheets demonstrated that ANP also can stimulate the Isc across this tissue directly (Karnaky et al., 1991). Other studies have demonstrated that the endogenous natriuretic peptide is actually C-type natriuretic peptide in elasmobranchs (Schofield et al., 1991), and the appropriate receptor (NPR-B) was cloned from rectal gland tissue by John Forrest's group (Aller et al., 1999). Forrest's group has also cloned the VIP receptor from the rectal gland (Bewley et al., 2006). Neuropeptide Y inhibits secretion by the perfused gland (Silva et al., 1993), as does somatostatin (Silva et al., 1985). Bombesin also inhibits gland secretion, but via the release of somatostatin (Silva et al., 1990a). Adenosine inhibits gland secretion at low concentrations (<10−7 M) but stimulates secretion at concentrations greater than 10−6 M (Kelley et al., 1990). In addition to exogenous and endogenous signals that may stimulate or inhibit salt transport across the glandular epithelium, it appears that the gland also may be regulated by alterations in perfusion via the posterior mesenteric artery since the anterior mesenteric artery responds to both putative constrictory (acetylcholine and endothelin) and dilatory (C-type natriuretic peptide and prostanoids) signaling agents (Evans, 2001). In addition, the rectal gland has a circumferential ring of smooth muscle, and so the gland itself responds to this same suite of putative vasoactive substances (Evans and Piermarini, 2001). Somewhat surprisingly, it appears that the rectal gland responds to plasma volume rather than salt concentration (Solomon et al., 1985).

Marine Teleost Gill Salt Secretion10

As mentioned in Section “Introduction,” Homer Smith proposed that the gills were the likely site of net salt secretion in marine teleosts, since the kidney was unable to produce a urine that was hypertonic to the fish's plasma (Smith, 1930). This proposition was supported by the very careful experiments by Ancel Keys in August Krogh's laboratory in Copenhagen that demonstrated that the perfused eel gill could secreted Cl against the chemical gradient, probably the first description of active transport across an epithelium (Keys, 1931). Keys also described what he termed “chloride-secreting cells” in the gill epithelium of the eel (Keys and Willmer, 1932), which he proposed could be the site of this active salt transport. Subsequent studies demonstrated that this cell displayed morphological characteristics of other transporting cells (e.g., elaboration of the basolateral membrane and numerous mitochondria11 (Philpott, 1965), and expressed high concentration of Na+, K+-activated ATPase (Kamiya, 1972; Sargent et al., 1975). Previously, Frank Epstein's lab at the MDIBL had demonstrated relatively high concentrations of Na+, K+-ATPase in the gill tissue of marine teleosts (Jampol and Epstein, 1970). Two early studies presented evidence that the Na+/K+ exchange might be apical (seawater K+ for intracellular Na+; (Maetz, 1969; Evans and Cooper, 1976), but Karl Karnaky went to do a postdoc with Bill Kinter at the MDIBL in 1972 and demonstrated conclusively that tritiated ouabain (binding to Na+, K+-activated ATPase) was on the basolateral membrane of the chloride cell in the killifish gill (Karnaky et al., 1976)12. Reasoning that basolateral Na+, K+-ATPase should be inhibited by injected ouabain, Patricio Silva in Epstein's group discovered that such an injection into the seawater acclimated eel inhibited both Na+ and Cl− efflux, with little effect on the efflux of tritiated water (suggesting that a change in branchial blood flow was not the cause of the ionic efflux declines) (Silva et al., 1977a). They suggested that such functional coupling of Na+ and Cl− efflux was best explained by the model that they proposed at the same time for salt secretion by the shark rectal gland (Silva et al., 1977b). This model was confirmed by Karl Karnaky, using the isolated killifish opercular membrane, which he showed had a high concentration of chloride cells (Karnaky and Kinter, 1977). Karnaky and colleagues at the MDIBL found that this tissue could be mounted in a small-aperture, Ussing chamber which allowed measurement of ionic fluxes under short-circuited conditions. They showed clearly that the Isc was accounted for by the net efflux of Cl−, which was inhibited by basolateral addition of either ouabain or furosemide. There was no net efflux of Na+ under the short-circuited conditions (Degnan et al., 1977), indicating that Na+ movement was passive, through the tight junctions between the epithelial cells (Figure 3). More recently, a potassium channel has been localized in MRC, presumably the site of recycling of K+ (Suzuki et al., 1999).

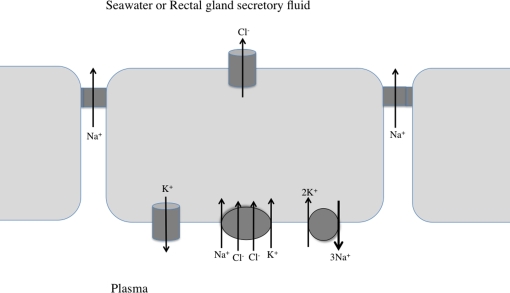

Figure 3.

Working model for NaCl secretion by the shark rectal gland and marine teleost gill epithelium. Three epithelial cells, with connecting tight junctions are shown. See text for details.

Karnaky's group also demonstrated that the Isc across the killifish opercular membrane was inhibited by epinephrine (Degnan et al., 1977), and subsequent studies found that this inhibition was mediated by α-adrenergic receptors, while stimulation of β-adrenergic receptors resulted in an increase in the Isc (Mendelsohn et al., 1981). A variety of signaling agents have been shown to modulate teleost gill salt extrusion (for reviews see McCormick, 2001; Evans, 2002; Evans et al., 2005), including endothelin, which our work at the MDIBL has shown, inhibits Isc across the opercular membrane via an axis that includes nitric oxide, superoxide, and a prostaglandin (Evans et al., 2004).

Evolutionary Origin of NaCl Uptake Mechanisms in Freshwater Fishes13

August Krogh was a Danish contemporary of Smith and Marshall, and the postdoctoral advisor of Ancel Keys. His notable contribution to the study of fish osmoregulation was the hypothesis that freshwater fishes extract needed NaCl from the environmental via parallel Na+/ and Cl−/ exchangers (Krogh, 1937, 1938). He proposed these ionic exchanges because he demonstrated that non-feeding catfishes, sticklebacks, perch, and trout could reduce the Cl− concentration of tank water surrounding the head end of the fish in divided chamber experiments. Importantly, he found that the Cl− uptake was independent of the cation (Na+, K+, and Ca2+), and the uptake of Na+ was independent of the anion (Cl−, Br−, and NO3−). In fact, he found similar results with freshwater annelids, mollusks, and crustacea, and proposed that these ionic exchange mechanisms were a general phenomenon in hyper-regulating, freshwater organisms (Krogh, 1939). Data published in the last two decades suggests that the Na+ uptake actually is coupled to H loss, either by an apical Na+/H+ exchanger or via an apical Na+ channel which moves Na+ inward down an electrochemical gradient produced by an apical proton pump (V-H+-ATPase) (e.g., Hwang, 2009). Chloride uptake is thought to be either via Krogh's Cl−/ exchanger (SLC26; Perry et al., 2009) or possibly via an apical NCC coupled to a basolateral CIC-type Cl channel (Hwang, 2009; Tang et al., 2010). Ammonia excretion is now thought to be via diffusion of either NH3 or (Wilkie, 2002), or via the newly described, Rh glycoproteins (Weihrauch et al., 2009; Wright and Wood, 2009; Wu et al., 2010). Also, it is now generally agreed that the uptake of Na+ vs. Cl− is mediated by channels and carriers on different, mitochondrion-rich cells (e.g., Hwang and Lee, 2007) (Figure 4).

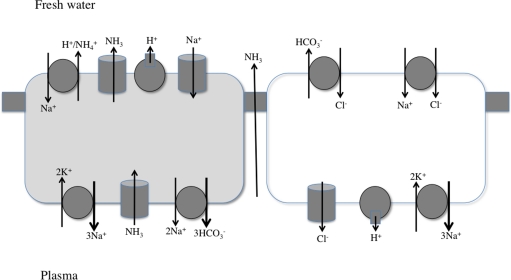

Figure 4.

Working model for NaCl uptake and acid/base or ammonia secretion by the teleost gill epithelium. Two epithelial cells, with connecting tight junctions are shown. The distribution of the transport proteins in specific cells may vary with fish species. See text and Evans (2010) for details.

Regardless of the actual mechanisms involved, it is apparent that the uptake of needed NaCl by freshwater fishes is coupled to the equally-important extrusion of acid–base equivalents14 and nitrogen wastes, a proposition that was first described 35 years ago (Evans, 1975). If this is the case, one might propose that they would be present in marine fish species, driven by needs for acid–base regulation and/or nitrogen waste excretion, rather than ion uptake. Our initial studies at the University of Miami demonstrated that Na+ uptake by a seawater acclimated, sailfin molly was saturable (and. therefore, presumably not via simple diffusion) and inhibited by external amiloride (which was thought to inhibit Na+/H+ exchange, Kirschner et al., 1973). In addition, Na+ uptake by four species of marine teleosts could be inhibited by the addition of to the medium (Evans, 1977). In order to extend these data to elasmobranchs, we came to the MDIBL in the summer of 1978. Using the little skate, we found that H+ efflux (but not ammonia efflux) was dependent upon external Na+ and inhibited by amiloride, suggesting that H+ excretion by the gill epithelium of this marine elasmobranch was via a Na+/H+ exchanger (Evans et al., 1979). The importance of such exchanges in acid–base regulation in at least teleosts was shown clearly by J. B. Claiborne and colleagues, working at the MDIBL, who demonstrated that recovery from induced acidosis in the longhorn sculpin was inhibited by low external Na+ concentrations (20–30 mM) or by external amiloride [or the more Na/H-specific 5-N,N-hexamethylene-amiloride (HMA)] (Claiborne and Evans, 1988). These physiological data were corroborated by subsequent molecular data showing immunolocalization of Na+/H+ exchanger isoforms (NHEs), and V-H+-ATPase, in the gill epithelium of the sculpin in seawater (Claiborne et al., 1999; Catches et al., 2006), and this gill localization of NHEs has now been extended to the little skate (Choe et al., 2002), spiny dogfish (Tresguerres et al., 2005; Choe et al., 2007), and killifish (Claiborne et al., 1999; Choe et al., 2002; Edwards et al., 2010) at the MDIBL. V-H+-ATPase and a Cl−/ exchanger (pendrin) have also been immunolocalized in the gill epithelium of the Atlantic stingray in seawater (Piermarini and Evans, 2001; Piermarini et al., 2002).

If, as these data suggest, the gill epithelium of marine teleosts and elasmobranchs expresses ionic transporters and channels (e.g., NHEs, V-H+-ATPase, and a Cl−/ exchanger) that function in acid–base regulation, but also can function in NaCl uptake, when did these exchangers evolve in the vertebrates (marine ancestors vs. freshwater ancestors?). Working at the MDIBL in the summer of 1983, we found that acid excretion from the Atlantic hagfish (a member of the most primitive vertebrate group, the agnatha) is inhibited by removal of external Na+, and the excretion of base was inhibited by removal of external Cl−, suggesting that Na+/H+ and Cl−/ exchangers were present in the most primitive vertebrates, before the evolution of either the elasmobranchs or teleosts. This is supported by the more recent work at the MDIBL that has immunolocalized an NHE to gill tissue from the Atlantic hagfish (Choe et al., 2002) and, from the Bamfied Marine lab (Canada), NHE and V-H+-ATPase from the Pacific hagfish (Tresguerres et al., 2006). Moreover, acidosis in the Pacific species is correlated with an increase in the NHE levels in the gill epithelium (Parks et al., 2007). An NHE also has been localized (by rtPCR) to the gill epithelium of the sea lamprey at the MDIBL, another member of the agnatha (Fortier et al., 2008). Thus, it seems clear that the gill transport mechanisms that provide necessary NaCl uptake in freshwater fishes actually evolved in marine ancestors for acid–base regulation. If this is the case, one might ask why all fishes (including the primitive hagfishes) are not euryhaline? There is no clear answer to this question, but one might propose that the kinetics of ionic uptake (mediated by a carrier with a finite affinity and number) vs. ionic loss (via diffusion and renal excretion) are not in balance in the more stenohaline species (Evans, 1984). The kinetic analyses of uptake vs. loss in different salinities necessary to test this hypothesis have not been published. Another limiting factor may be the ability to turn off the gill NaCl excretory mechanisms necessary for osmoregulation in seawater. This seems to be the case with the partially euryhaline longhorn sculpin. Working at the MDIBL Kelly Hyndman has shown that this species is unable to downregulate gill levels of mRNA or protein for Na+, K+-ATPase, NKCC, or CFTR when it is in 20% seawater (Hyndman and Evans, 2009).

Conclusions

The foregoing outlines over 80 years of research at the MDIBL that has formed the basis for current models for many of the strategies of fish osmoregulation, as well as mechanisms of ion transport across epithelial membranes in general. It is clear that the synergy that characterizes research at the MDIBL (and, indeed, other similar facilities at Friday Harbor, WA, USA; Bamfield, BC, USA; Pacific Grove, CA, USA and Woods Hole, MA, USA) has facilitated discussions, techniques, and experiments that have played a major role in our current knowledge of osmoregulation and epithelial transport. It is hoped the next 80 years will continue this tradition.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The support of the National Science Foundation (most recently, IOB-0519579) is gratefully acknowledged. The author acknowledges Leon Goldstein who first suggested that he come to the MDIBL to continue his research in fish osmoregulation.

Footnotes

1For an excellent review of MDIBL history and research to 1998, see Epstein (1998).

2More complete reviews of fish osmoregulation include Karnaky (1998), Marshall and Grosell (2006), and Evans and Claiborne (2009).

3Homer Smith had worked, periodically, with E. K. Marshall between 1918 and 1928 on the biological action of nerve gases and chemotherapeutic drugs, so it is likely that Smith was recruited to the MDIBL by Marshall.

4Surprisingly, the toadfish is euryhaline (Lahlou et al., 1969).

5Reviews of NaCl cotransporters include Frizzell et al. (1979a), Hebert and Gullans (1995), Kaplan et al. (1996), and Hebert et al. (2004).

6Diamond switched from physiology to ecology and evolutionary biology decades ago and is known currently as a best-selling author of socio-economic books, such as “Collapse” (Viking Press, 2004).

7Bodil Schmidt-Nielsen began spending summers at MDIBL in 1952, invited by Homer Smith. She had a long, distinguished career, moved to MDIBL on a year-round basis in 1970, and retired in 1986.

8NaCl secretion in the mammalian intestine is via NKCC1 and CFTR (Venkatasubramanian et al., 2010).

9For reviews of rectal gland physiology, see Greger et al. (1986), Silva et al. (1990b, 1996, 1997), Riordan et al. (1994), and Forrest (1996).

10For a more complete discussion of gill salt transport, see Evans et al. (2005).

11These cells are now commonly termed mitochondrion-rich cells.

12It is important to note that it was during the mid-70s that the mechanisms for fish intestinal NaCl absorption, gill salt secretion, and rectal gland salt secretion were being investigated in adjoining labs at the MDIBL. Karnaky has presented an interesting, first-person account of the interactions between the Kinter, Field, and Epstein labs during this time period (Karnaky, 2008).

13For a more complete discussion of the mechanisms of salt uptake by the freshwater fish gill, see Evans and Claiborne (2009), Hwang (2009), and Evans (2010).

14For a more complete discussion of acid–base regulation in fishes, see Claiborne et al. (2002).

References

- Aller S. G., Lombardo I. D., Bhanot S., Forrest J. N., Jr. (1999). Cloning, characterization, and functional expression of a CNP receptor regulating CFTR in the shark rectal gland. Am. J. Physiol. 276, C442–C449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewley M. S., Pena J. T., Plesch F. N., Decker S. E., Weber G. J., Forrest J. N., Jr. (2006). Shark rectal gland vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor: cloning, functional expression, and regulation of CFTR chloride channels. Am. J. Physiol. 291, R1157–R1164 10.1152/ajpregu.00078.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyenbach K. W. (2004). Kidneys sans glomeruli. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 286, F811–F827 10.1152/ajprenal.00351.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyenbach K. W., Fromter E. (1985). Electrophysiological evidence for Cl secretion in shark renal proximal tubules. Am. J. Physiol. 248, F282–F295 10.1016/S1546-5098(08)60243-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyenbach K. W., Petzel D. H., Cliff W. H. (1986). Renal proximal tubule of flounder. I. Physiological properties. Am. J. Physiol. 250, R608–R615 10.1159/000173056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonting S. L. (1966). Studies on sodium–potassium-activated adenosinetriphosphatase. XV. The rectal gland of the elasmobranchs. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 17, 953–966 10.1016/0010-406X(66)90134-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg M., Grrantham J., Abramov M., Orloff J. (1966). Preparation and study of fragments of single rabbit nephrons. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. 210, 1293–1298 10.1038/266096a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg M. B., Weller P. F. (1969). Iodopyracet transport by isolated perfused flounder proximal renal tubules. Am. J. Physiol. 217, 1053–1056 10.1038/ki.1976.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger J. W., Hess W. N. (1960). Function of the rectal gland of the spiny dogfish. Science 131, 670–671 10.1126/science.131.3401.670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess D. W., Miarczynski M. D., O'Donnell M. J., Wood C. M. (2000). Na+ and Cl− transport by the urinary bladder of the freshwater rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). J. Exp. Zool. 287, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catches J. S., Burns J. M., Edwards S. L., Claiborne J. B. (2006). Na+/H+ antiporter, V-H+/-ATPase and Na+/K+-ATPase immunolocalization in a marine teleost (Myoxocephalus octodecemspinosus). J. Exp. Biol. 209, 3440–3447 10.1007/BF00688738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R., Kempton R. T. (1933). Indications of function of the chick mesonephros in tussue culture with phenol red. J. Cell. Comp. Physiol. 3, 131–137 10.1002/jcp.1030030203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choe K. P., Edwards S. L., Claiborne J. B., Evans D. H. (2007). The putative mechanism of Na(+) absorption in euryhaline elasmobranchs exists in the gills of a stenohaline marine elasmobranch, Squalus acanthias. Comp. Biochem. Physiol., Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 146, 155–162 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe K. P., Morrison-Shetlar A. I., Wall B. P., Claiborne J. B. (2002). Immunological detection of Na+/H+ exchangers in the gills of a hagfish, Myxine glutinosa, an elasmobranch, Raja erinacea, and a teleost, Fundulus heteroclitus. Comp. Biochem. Physiol., Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 131, 375–385 10.1016/S1095-6433(01)00491-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claiborne J. B., Blackston C. R., Choe K. P., Dawson D. C., Harris S. P., Mackenzie L. A., Morrison-Shetlar A. I. (1999). A mechanism for branchial acid excretion in marine fish: identification of multiple Na+/H+ antiporter (NHE) isoforms in gills of two seawater teleosts. J. Exp. Biol. 202, 315–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claiborne J. B., Edwards S. L., Morrison-Shetlar A. I. (2002). Acid–base regulation in fishes: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Exp. Zool. 293, 302–319 10.1002/jez.10125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claiborne J. B., Evans D. H. (1988). Ammonia and acid–base balance during high ammonia exposure in a marine teleost (Myoxocephalus octodecimspinosus). J. Exp. Biol. 140, 89–105 10.1007/BF00688738 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cliff W. H., Sawyer D. B., Beyenbach K. W. (1986). Renal proximal tubule of flounder II. Transepithelial Mg secretion. Am. J. Physiol. 250, R616–R624 10.1159/000173056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler C. P., Cramb G. (2008). Differential expression of absorptive cation-chloride-cotransporters in the intestinal and renal tissues of the European eel (Anguilla anguilla). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B, Biochem. Mol. Biol. 149, 63–73 10.1016/j.cbpb.2007.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. C., Andrew D. (1979). Differential inhibition of NaCl absorption and short-circuit cuirrent in the urinary bladder of the winter flounder, Pseudopleuronectes americanus. Bull. Mt. Desert Isl. Biol. Lab. Salisb. Cove Maine 19, 46–49 [Google Scholar]

- Degnan K. J., Karnaky K. J., Jr, Zadunaisky J. (1977). Active chloride transport in the in vitro opercular skin of a teleost (Fundulus heteroclitus), a gill-like epithelium rich in chloride cells. J. Physiol. (Lond). 271, 155–191 10.1126/science.831273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarest J. R. (1984). Ion and water transport by the flounder urinary bladder: salinity dependence. Am. J. Physiol. 246, F395–F401 10.1111/j.1745-7939.2002.tb01645.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond J. M. (1962). The mechanism of solute transport by the gall-bladder. J. Physiol. (Lond). 161, 474–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond J.M. (2004). Collapse. Viking Press; 592 [Google Scholar]

- Djurisic M., Isenring P., Forbush B. (2003). Cloning, tissue distribution and changes during salt adaptation of three Na–K–Cl cotransporter isoforms from killifish, Fundulus heteroclitus. Bull. Mt. Desert Isl. Biol. Lab. Salisb. Cove Maine 42, 89–90 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S., Weakley J., Diamanduros A., Claiborne J. (2010). Molecular identification of Na+/H+ exchanger isoforms (NHE2) in the gills of the euryhaline teleost Fundulus heteroclitus. J. Fish Biol. 76, 415–426 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2009.02534.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein F. H. (1998). A Laboratory by the Sea. The Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory: 1898–1998. Rhinebeck, NY: River Press [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. H. (1975). Ionic exchange mechanisms in fish gills. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 51A, 491–495 10.1016/0300-9629(75)90331-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. H. (1977). Further evidence for Na/NH4 exchange in marine teleost fish. J. Exp. Biol. 70, 213–220 [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. H. (1984). “The roles of gill permeability and transport mechanisms in euryhalinity,” in Fish Physiology, vol. XB, eds. Hoar W. S., Randall D. J. (Orlando: Academic Press; ), 239–283 10.1016/S1546-5098(08)60187-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. H. (2001). Vasoactive receptors in abdominal blood vessels of the dogfish shark, Squalus acanthias. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 74, 120–126 10.1086/319308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. H. (2002). Cell signaling and ion transport across the fish gill epithelium. J. Exp. Zool. 293, 336–347 10.1002/jez.10128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. H. (2008). Teleost fish osmoregulation: what have we learned since August Krogh, Homer Smith, and Ancel Keys? Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 295, R704–R713 10.1152/ajpregu.90337.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. H. (2010). Fish gill ion uptake: August Krogh to morpholinos. Acta Physiol. (in press). 10.1097/00004714-198506000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. H., Claiborne J. B. (2009). “Osmotic and ionic regulation in fishes,” in Osmotic and Ionic Regulation: Cells and Animals, ed.Evans D. H. (Boca Raton: CRC Press; ), 295–366 [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. H., Cooper K. (1976). The presence of Na–Na and Na–K exchange in sodium extrusion by three species of fish. Nature 259, 241–242 10.1038/259241a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. H., Kormanik G. A., Krasny E., Jr. (1979). Mechanisms of ammonia and acid extrusion by the little skate Raja erinacea. J. Exp. Zool. 208, 431–437 10.1002/jez.1402080319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. H., Piermarini P. M. (2001). Contractile properties of the elasmobranch rectal gland. J. Exp. Biol. 204, 59–67 10.1021/jp004237t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. H., Piermarini P. M., Choe K. P. (2005). The multifunctional fish gill: dominant site of gas exchange, osmoregulation, acid–base regulation, and excretion of nitrogenous waste. Physiol. Rev. 85, 97–177 10.1152/physrev.00050.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. H., Rose R. E., Roeser J. M., Stidham J. D. (2004). NaCl transport across the opercular epithelium of Fundulus heteroclitus is inhibited by an endothelin to NO, superoxide, and prostanoid signaling axis. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 286, R560–R568 10.1152/ajpregu.00281.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M., Karnaky K. J., Jr., Smith P. L., Bolton J. E., Kinter W. B. (1978). Ion transport across the isolated intestinal mucosa of the winter flounder, Pseudopleuronectes americana. I. Functional and structural properties of cellular and paracellular pathways for Na and Cl. J. Membr. Biol. 41, 265–293 10.1007/BF01870433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest J. N., Jr. (1996). Cellular and molecular biology of chloride secretion in the shark rectal gland: regulation by adenosine receptors. Kidney Int. 49, 1557–1562 10.1038/ki.1996.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster R., Taggart J. (1950). Use of isolated renal tubules for the examination of metabolic processes associated with active cellular transport. J. Cell Comp. Physiol. 36, 251–270 10.1002/jcp.1030360210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster R. P. (1977). My forty years at the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory. J. Exp. Zool. 199, 299–307 10.1002/jez.1401990303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortier J., Diamanduros A. W., Claiborne J. B., Hyndman K. A., Evans D. H., Edwards S. L. (2008). Molecular characterization of NHE8 in the sea lamprey, Petromyzon marinus. Bull. Mt. Desert Isl. Biol. Lab. Salisb. Cove Maine 47, 26–27 10.1002/pits.20335 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frizzell R. A., Field M., Schultz S. G. (1979a). Sodium-coupled chloride transport by epithelial tissues. Am. J. Physiol. 236, F1–F8 10.1085/jgp.65.6.769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frizzell R. A., Smith P. L., Field M. (1981). “Sodium chloride absorption by flounder intestine: a model for the renal thick ascending limb,” in Membrane Biophysics: Structure and Function in Epithelia, eds. Dinno M., Callahan A. (New York: Alan R. Liss; ), 67–81 10.1007/BF01959973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frizzell R. A., Smith P. L., Vosburgh E., Field M. (1979b). Coupled sodium–chloride influx across brush border of flounder intestine. J. Membr. Biol. 46, 27–39 10.1007/BF01959973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamba G., Saltzberg S. N., Lombardi M., Miyanoshita A., Lytton J., Hediger M. A., Brenner B. M., Hebert S. C. (1993). Primary structure and functional expression of a cDNA encoding the thiazide-sensitive, electroneutral sodium–chloride cotransporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 2749–2753 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham J. J., Wallace D. P. (2002). Return of the secretory kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 282, F1–F9 10.1038/ncpneph0082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greger R., Schlatter E. (1981). Presence of luminal K+, a prerequisite for active NaCl transport in the cortical thick ascending limb of Henle's loop of rabbit kidney. Pflugers Arch. 392, 92–94 10.1007/BF00584588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greger R., Schlatter E., Gogelein H. (1986). Sodium chloride secretion in rectal gland of dogfish, Squalus acanthias. News Physiol. Sci. 1, 134–136 10.1007/BF00584833 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grosell M. (2006). Intestinal anion exchange in marine fish osmoregulation. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 2813–2827 10.1242/jeb.02345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosell M., Genz J., Taylor J., Perry S., Gilmour K. (2009). The involvement of H+-ATPase and carbonic anhydrase in intestinal HCO3− secretion in seawater-acclimated rainbow trout. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 1940–1948 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.04.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosell M., Taylor J. R. (2007). Intestinal anion exchange in teleost water balance. Comp. Biochem. Physiol., Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 148, 14–22 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzelczak Z., Alon N., Fahim S., Dubel S., Collins F. S., Tsui L.-C., Riordan J. (1990). The molecular cloning of a CFTR homologue from shark rectal gland. Pediatr. Pulmonol. Suppl. 5, 95. 10.1126/science.2475911 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haas M., Schmidt W. F., McManus T. J. (1982). Catecholamine-stimulated ion transport in duck red cells. Gradient effects in electrically neutral [Na + K + 2Cl] Co-transport. J. Gen. Physiol. 80, 125–147 10.1085/jgp.80.1.125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halm D. R., Krasny E. J., Jr., Frizzell R. A. (1985). Electrophysiology of flounder intesstinal mucosa I. Conductance properties of the cellular and paracellular pathways. J. Gen. Physiol. 85, 843–864 10.1085/jgp.85.6.843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan J. W., Mathews C. J., Grygorczyk R., Tabcharani J. A., Grzelczak Z., Chang X. B., Riordan J. R. (1996). Regulation of the CFTR chloride channel from humans and sharks. J. Exp. Zool. 275, 283–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayslett J. P., Schon D. A., Epstein M., Hogben C. A. (1974). In vitro perfusion of the dogfish rectal gland. Am. J. Physiol. 226, 1188–1192 10.1016/0300-9629(72)90486-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert S. C., Gullans S. R. (1995). The electroneutral sodium–(potassium)–chloride co-transporter family: a journey from fish to the renal co-transporters. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 4, 389–391 10.1097/00041552-199509000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert S. C., Mount D. B., Gamba G. (2004). Molecular physiology of cation-coupled Cl− cotransport: the SLC12 family. Pflugers Arch. 447, 580–593 10.1007/s00424-003-1066-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilden S., Hokin L. E. (1975). Active potassium transport coupled to active sodium transport in vesicles reconstituted from purified sodium and potassium ion-activated adenosine triphosphatase from the rectal gland of Squalus acanthias. J. Biol. Chem. 250, 6296–6303 10.1002/jss.400010409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang P. P. (2009). Ion uptake and acid secretion in zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Exp. Biol. 212, 1745–1752 10.1242/jeb.026054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang P. P., Lee T. H. (2007). New insights into fish ion regulation and mitochondrion-rich cells. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 48, 479–497 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.06.416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman K. A., Evans D. H. (2009). Short-term low-salinity tolerance by the longhorn sculpin, Myoxocephalus octodecimspinosus. J. Exp. Zool. 311A, 45–56 10.1002/jez.494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jampol L. M., Epstein F. H. (1970). Sodium–potassium–activated adenosine triphosphatase and osmotic regulation by fishes. Am. J. Physiol. 218, 607–611 10.1016/0014-4835(72)90113-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya M. (1972). Sodium–potassium-activated adenosinetriphosphatase in isolated chloride cells from eel gills. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 43B, 611–617 10.1016/0305-0491(72)90145-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan M. R., Mount D. B., Delpire E., Gamba G., Hebert S. C. (1996). Molecular mechanisms of NaCl cotransport. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 58, 649–668 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.003245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnaky K. G., Jr., Kinter W. B. (1977). Killifish opercular skin: a flat epithelium with a high density of chloride cells. J. Exp. Zool. 199, 355–364 10.1002/jez.1401990309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnaky K. J., Jr. (1998). “Osmotic and ionic regulation,” in The Physiology of Fishes, Evans D. H. ed. (Boca Raton: CRC Press; ), 157–176 [Google Scholar]

- Karnaky K. J., Jr. (2008). From form to function/Homer Smith to CFTR: salt secretion across epithelia from the perspective of the teleost chloride cell. Bull. Mt. Desert Isl. Biol. Lab. Salisb. Cove Maine 47, 1–10 [Google Scholar]

- Karnaky K. J., Jr., Kinter L. B., Kinter W. B., Stirling C. E. (1976). Teleost chloride cell. II. Autoradiographic localization of gill Na, K-ATPase in killifish Fundulus heteroclitus adapted to low and high salinity environments. J. Cell. Biol. 70, 157–177 10.1083/jcb.70.1.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnaky K. J., Jr., Valentich J. D., Currie M. G., Oehlenschlager W. F., Kennedy M. P. (1991). Atriopeptin stimulates chloride secretion in cultured shark rectal gland cells. Am. J. Physiol. 260, C1125–C1130. 10.1016/S1546-5098(08)60246-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley G. G., Poeschla E. M., Barron H. V., Forrest J. N., Jr. (1990). A1 adenosine receptors inhibit chloride transport in the shark rectal gland. Dissociation of inhibition and cyclic AMP. J. Clin. Invest. 85, 1629–1636 10.1172/JCI114614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys A. (1931). Chloride and water secretion and absorption by the gills of the eel. Z. Vgl. Physiol. 15, 364–389 10.1007/BF00339115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keys A. B., Willmer E. N. (1932). “Chloride-secreting cells” in the gills of fishes with special reference to the common eel. J. Physiol. (Lond). 76, 368–378 10.1007/BF00339115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner L. B., Greenwald L., Kerstetter T. H. (1973). Effect of amiloride on sodium transort across body surfaces of fresh water animals. Am. J. Physiol. 224, 832–837 10.1016/0926-860X(93)80189-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A. (1937). Osmotic regulation in freshwater fishes by active absorption of chloride ions. Z. Vgl. Physiol. 24, 656–666 10.1007/BF00592303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A. (1938). The active absorption of ions in some freshwater animals. Z. Vgl. Physiol. 25, 335–350 10.1007/BF00592303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A. (1939). Osmotic Regulation in Aquatic Animals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Lahlou B., Henderson I. W., Sawyer W. H. (1969). Renal adaptations by Opsanus tau, a euryhaline aglomerular teleost, to dilute media. Am. J. Physiol. 216, 1266–1272 10.1016/0010-406X(69)90580-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loretz C. A., Fourtner C. R. (1988). Functional characterization of a voltage-gated anion channel from teleost fish intestinal epithelium. J. Exp. Biol. 136, 383–403 10.1016/S1546-5098(08)60241-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorin-Nebel C., Boulo V., Bodinier C., Charmantier G. (2006). The Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransporter in the sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax during ontogeny: involvement in osmoregulation. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 4908–4922 10.1242/jeb.02591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle C., Xu J. C., Biemesderfer D., Haas M., Forbush B., 3rd. (1992). The Na–K–Cl cotransport protein of shark rectal gland. I. Development of monoclonal antibodies, immunoaffinity purification, and partial biochemical characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 25428–25437 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maetz J. (1969). Sea water teleosts: evidence for a sodium–potassium exchange in the branchial sodium-excreting pump. Science 166, 613–615 10.1126/science.166.3905.613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall E. K. (1930). A comparison of the function of the glomerular and aglomerular kidney. Am. J. Physiol. 94, 1–10 10.1097/00002480-198907000-00105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall E. K., Smith H. W. (1930). The glomerular development of the vertebrate kidney in relation to habitat. Biol. Bull. 59, 135–153 10.2307/1536983 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J., Martin K. A., Picciotto M., Hockfield S., Nairn A. C., Kaczmarek L. K. (1991). Identification and localization of a dogfish homolog of human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 22749–22754 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W. (1986). Independent Na and Cl− active transport by urinary bladder epithelium of brook trout. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 250, 227–234 10.1139/z88-134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W. S., Grosell M. (2006). “Ion transport, osmoregulation and acid–base balance,” in The Physiology of Fishes, eds. Evans D. H., Claiborne J. B. (Boca Raton: CRC Press; ), 177–230 10.1152/ajpregu.00818.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W. S., Howard J. A., Cozzi R. R., Lynch E. M. (2002). NaCl and fluid secretion by the intestine of the teleost Fundulus heteroclitus: involvement of CFTR. J. Exp. Biol. 205, 745–758 10.1139/Z08-108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick S. D. (2001). Endocrine control of osmoregulation in teleost fish. Am. Zool. 41, 781–794 10.1093/icb/41.4.781 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McRoberts J., Erlinger S., Rindler M., Saier M. J. (1982). Furosemide-sensitive salt transport in the Madin-Darby Canine Kidney cell line: Evidence for the cotransport of Na+, K+, and Cl−. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 2260–2266 10.1083/jcb.100.1.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn S. A., Cherksey B. D., Degnan K. J. (1981). Adrenergic regulation of chloride secretion across the opercular epithelium: the role of cyclic AMP. J. Comp. Physiol. 145, 29–35 10.1007/BF00782590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D. S. (2002). Xenobiotic export pumps, endothelin signaling, and tubular nephrotoxicants – a case of molecular hijacking. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 16, 121–127 10.1002/jbt.10030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musch M. W., Orellana S. A., Kimberg L. S., Field M., Halm D. R., Krasny E. J., Jr., Frizzell R. A. (1982). Na+-K+-Cl− co-transport in the intestine of a marine teleost. Nature 300, 351–353 10.1016/0076-6879(90)92106-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks S. K., Tresguerres M., Goss G. G. (2007). Blood and gill responses to HCl infusions in the Pacific hagfish (Eptatretus stoutii). Can. J. Zool. 85, 855–862 10.1139/Z07-068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perry S. F., Vulesevic B., Grosell M., Bayaa M. (2009). Evidence that SLC26 anion transporters mediate branchial chloride uptake in adult zebrafish (Danio rerio). Am. J. Physiol. 297, R988–R997 10.1152/ajpregu.00327.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott C. W. (1965). Halide localization in the teleost chloride cell and its identification by selected area electron diffraction. Protoplasma 60, 7–23 10.1007/BF01248125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piermarini P. M., Evans D. H. (2001). Immunochemical analysis of the vacuolar proton-ATPase B-subunit in the gills of a euryhaline stingray (Dasyatis sabina): effects of salinity and relation to Na+/K+-ATPase. J. Exp. Biol. 204, 3251–3259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piermarini P. M., Verlander J. W., Royaux I. E., Evans D. H. (2002). Pendrin immunoreactivity in the gill epithelium of a euryhaline elasmobranch. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 283, R983–R992 10.1073/pnas.071516798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfro J. L. (1975). Water and ion transport by the urinary bladder of the teleost Pseudopleuronectes americanus. Am. J. Physiol. 228, 52–61 10.1002/jez.1401990311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfro J. L. (1977). Interdependence of active Na+ and Cl− transport by the isolated urinary bladder of the teleost, Pseudopleuronectes americanus. J. Exp. Zool. 199, 383–390 10.1002/jez.1401990311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuss L., Segal Y., Altenberg G. (1991). Regulation of ion transport across gallbladder epithelium. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 53, 361–373 10.1146/annurev.ph.53.030191.002045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan J. R., Forbush B., 3rd., Hanrahan J. W. (1994). The molecular basis of chloride transport in shark rectal gland. J. Exp. Biol. 196, 405–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent J. R., Thomson A. J., Bornancin M. (1975). Activities and localization of succinic dehydrogenase and Na+/K+-activated adenosine triphosphatase in the gills of fresh water and sea water eels. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 51 B, 75–79 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90091-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer D. B., Beyenbach K. W. (1985). Mechanism of fluid secretion in isolated shark renal proximal tubules. Am. J. Physiol. 249, F884–F890. 10.1038/299054a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield J. P., Jones D. S., Forrest J. N., Jr. (1991). Identification of C-type natriuretic peptide in heart of spiny dogfish shark (Squalus acanthias). Am. J. Physiol. 261, F734–F739. 10.2307/1442144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel N. J., Schon D. A., Hayslett J. P. (1976). Evidence for active chloride transport in dogfish rectal gland. Am. J. Physiol. 230, 1250–1254 10.1016/0300-9629(75)90346-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva P., Epstein F. H., Karnaky K. J., Jr., Reichlin S., Forrest J. N., Jr. (1993). Neuropeptide Y inhibits chloride secretion in the shark rectal gland. Am. J. Physiol. 265, R439–R446. 10.1038/ki.1996.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva P., Lear S., Reichlin S., Epstein F. H. (1990a). Somatostatin mediates bombesin inhibition of chloride secretion by rectal gland. Am. J. Physiol. 258, R1459–R1463 10.1016/0024-3205(86)90033-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva P., Solomon R., Spokes K., Epstein F. (1977a). Ouabain inhibition of gill Na–K-ATPase: relationship to active chloride transport. J. Exp. Zool. 199, 419–426 10.1002/jez.1401990316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva P., Solomon R. J., Epstein F. H. (1990b). Shark rectal gland. Meth. Enzymol. 192, 754–766 10.1016/0076-6879(90)92107-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva P., Solomon R. J., Epstein F. H. (1996). The rectal gland of Squalus acanthias: a model for the transport of chloride. Kidney Int. 49, 1552–1556 10.1038/ki.1996.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva P., Solomon R. J., Epstein F. H. (1997). Transport mechanisms that mediate the secretion of chloride by the rectal gland of Squalus acanthias. J. Exp. Zool. 279, 504–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva P., Stoff J., Field M., Fine L., Forrest J. N., Epstein F. H. (1977b). Mechanism of active chloride secretion by shark rectal gland: role of Na–K-ATPase in chloride transport. Am. J. Physiol. 233, F298–F306 10.1002/jez.1401990319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva P., Stoff J. S., Leone D. R., Epstein F. H. (1985). Mode of action of somatostatin to inhibit secretion by shark rectal gland. Am. J. Physiol. 249, R329–R334 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1981.tb15509.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva P., Stoff J. S., Solomon R. J., Lear S., Kniaz D., Greger R., Epstein F. H. (1987). Atrial natriuretic peptide stimulates salt secretion by shark rectal gland by releasing VIP. Am. J. Physiol. 252, F99–F103 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1981.tb15509.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. W. (1930). The absorption and excretion of water and salts by marine teleosts. Am. J. Physiol. 93, 480–505 10.1300/j085V01N02_05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. W. (1931). The absorption and secretion of water and salts by the elasmobranch fishes. II. Marine elasmobranchs. Am. J. Physiol. 98, 296–310 10.1016/S0957-5839(99)80017-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon R., Taylor M., Sheth S., Silva P., Epstein F. H. (1985). Primary role of volume expansion in stimulation of rectal gland function. Am. J. Physiol. 248, R638–R640 10.1016/0076-6879(90)92107-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoff J. S., Rosa R., Hallac R., Silva P., Epstein F. H. (1979). Hormonal regulation of active chloride transport in the dogfish rectal gland. Am. J. Physiol. 237, 138–144 10.1002/jez.1401990319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes J. B. (1984). Sodium chloride absorption by the urinary bladder of the winter flounder: a thiazide-sensitive, electrically neutral transport system. J. Clin. Invest. 74, 7–16 10.1172/JCI111420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan S. K., Swamy K., Field M. (1991). cAMP-activated C1 conductance is expressed in Xenopus oocytes by injection of shark rectal gland mRNA. Am. J. Physiol. 260, C664–C669 10.1080/00206819109465745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvitayavat W., Dunham P. B., Haas M., Rao M. C. (1994). Characterization of the proteins of the intestinal Na(+)-K(+)-2Cl− cotransporter. Am. J. Physiol. 267, C375–C384 10.1016/j.jep.2003.09.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y., Itakura M., Kashiwagi M., Nakamura N., Matsuki T., Sakuta H., Naito N., Takano K., Fujita T., Hirose S. (1999). Identification by differential display of a hypertonicity-inducible inward rectifier potassium channel highly expressed in chloride cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 11376–11382 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C.-H., Hwang L.-Y., Lee T.-H. (2010). Chloride channel ClC-3 in gills of the euryhaline teleost, Tetraodon nigroviridis: expression, localization, and the possible role of chloride absorption. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 683–693 10.1242/jeb.040212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J. R., Mager E. M., Grosell M. (2010). Basolateral NBCe1 plays a rate-limiting role in transepithelial intestinal HCO3− secretion, contributing to marine fish osmoregulation. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 459–468 10.1242/jeb.029363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresguerres M., Katoh F., Fenton H., Jasinska E., Goss G. G. (2005). Regulation of branchial V-H(+)-ATPase, Na(+)/K(+)-ATPase and NHE2 in response to acid and base infusions in the Pacific spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias). J. Exp. Biol. 208, 345–354 10.1086/507658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tresguerres M., Parks S. K., Goss G. G. (2006). V-H(+)-ATPase, Na(+)/K(+)-ATPase and NHE2 immunoreactivity in the gill epithelium of the Pacific hagfish (Epatretus stoutii). Comp. Biochem. Physiol., Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 145, 312–321 10.1139/Z07-068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui T. K. N., Hung C. Y. C., Nawata C. M., Wilson J. M., Wright P. A., Wood C. M. (2009). Ammonia transport in cultured gill epithelium of freshwater rainbow trout: the importance of Rhesus glycoproteins and the presence of an apical Na+/NH4+ exchange complex. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 878–892 10.1242/jeb.021899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatasubramanian J., Ao M., Rao M. C. (2010). Ion transport in the small intestine. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 26, 123–128 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283358a45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldegger S., Fakler B., Bleich M., Barth P., Hopf A., Schulte U., Busch A. E., Aller S. G., Forrest J. N., Jr., Greger R., Lang F. (1999). Molecular and functional characterization of s-KCNQ1 potassium channel from rectal gland of Squalus acanthias. Pflugers Arch. 437, 298–304 10.1007/s004240050783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weihrauch D., Wilkie M. P., Walsh P. J. (2009). Ammonia and urea transporters in gills of fish and aquatic crustaceans. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 1716–1730 10.1242/jeb.024851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie M. P. (2002). Ammonia excretion and urea handling by fish gills: present understanding and future research challenges. J. Exp. Zool. 293, 284–301 10.1002/jez.10123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright P. A., Wood C. M. (2009). A new paradigm for ammonia excretion in aquatic animals: role of Rhesus (Rh) glycoproteins. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 2303–2312 10.1242/jeb.023085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.-C., Horng J.-L., Liu S.-T., Hwang P.-P., Wen Z.-H., Lin C.-S., Lin L.-Y. (2010). Ammonium-dependent sodium uptake in mitochondrion-rich cells of medaka (Oryzias latipes) larvae. Am. J. Physiol., Cell. Physiol. 298, C237–C250 10.1152/ajpcell.00373.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J. C., Lytle C., Zhu T. T., Payne J. A., Benz E., Jr, Forbush B., 3rd. (1994). Molecular cloning and functional expression of the bumetanide-sensitive Na–K–Cl cotransporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 2201–2205 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]