Abstract

Alternative splicing is an important mechanism for the generation of protein diversity at a post-transcriptional level. Modifications in the splicing patterns of several genes have been shown to contribute to the malignant transformation of different tissue types. In this study, we used the Affymetrix Exon arrays to investigate patterns of differential splicing between paediatric medulloblastomas and normal cerebellum on a genome-wide scale. Of the 1262 genes identified as potentially generating tumour-associated splice forms, we selected 14 examples of differential splicing of known cassette exons and successfully validated 11 of them by RT-PCR. The pattern of differential splicing of three validated events was characteristic for the molecular subset of Sonic Hedgehog (Shh)-driven medulloblastomas, suggesting that their unique gene signature includes the expression of distinctive transcript variants. Generally, we observed that tumour and normal fetal cerebellar samples shared significantly lower exon inclusion rates compared to normal adult cerebellum. We investigated whether tumour-associated splice forms were expressed in primary cultures of Shh-dependent mouse cerebellar granule cell precursors (GCPs) and found that Shh caused a decrease in the cassette exon inclusion rate of five out of the seven tested genes. Furthermore, we observed a significant increase in exon inclusion between post-natal days 7 and 14 of mouse cerebellar development, at the time when GCPs mature into post-mitotic neurons. We conclude that inappropriate splicing frequently occurs in human medulloblastomas and may be linked to the activation of developmental signalling pathways and a failure of cerebellar precursor cells to differentiate.

Keywords: Medulloblastoma, alternative splicing, exon arrays, Sonic Hedgehog, Granule Cell Precursor

Introduction

Medulloblastoma is a malignant embryonal tumour of the cerebellum, which most commonly affects children (1). Despite recent advances in the clinical management of this disease, approximately one third of the cases remain incurable and the majority of survivors suffer from long-term side effects caused by the therapeutic treatment (2). During the last few years, whole-genome gene expression studies have provided strong molecular evidence supporting the notion that medulloblastomas represent a heterogeneous disease and discrete medulloblastoma molecular subgroups have been identified based on the expression profile of specific sets of genes (3, 4).

Alternative splicing (AS) is key post-transcriptional mechanism for the generation of protein diversity. It has been estimated that more than 50% of human protein-coding genes undergo AS (5) and that splicing events greatly contribute to tissue- and development-specific protein expression (6). Inappropriate mRNA splicing has been described in many types of human cancer (7-10) and has been shown to affect the global pattern of protein expression within tumour tissues, through the generation of novel protein variants or the unbalanced expression of normal protein isoforms (11). In both cases, AS has the potential to initiate and/or sustain tumour growth. A few studies of human medulloblastomas have described alternative splice forms of individual genes which are associated with specific molecular subsets of medulloblastoma (12), normal cerebellar development (13) or tumour recurrence (14). To comprehensively study the potential contribution of alternative transcript forms to medulloblastoma pathogenesis, we used the Affymetrix Human Exon array, and measured gene expression at the level of individual exons on a genome-wide scale for 14 medulloblastoma and five normal cerebellar samples. We identified and validated differential splicing events occurring between the normal cerebellum and medulloblastoma and between different medulloblastoma molecular subgroups. We also showed that medulloblastomas share splicing patterns with mouse cerebellar granule cell precursors (GCPs), the proposed cells of origin for a molecular subset of medulloblastomas (15). This suggests that higher levels of specific transcript variants are maintained from the early stages of cerebellar development through the malignant transformation of precursor cells and could represent important pathways for medulloblastoma tumourigenesis.

Materials and Methods

Clinical samples

The exon array study included 14 snap-frozen paediatric medulloblastoma samples obtained from the Histopathology Department of Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), with the approval of the local research ethics committee (LREC ref. no. 06/Q0508/57). A histopathological review of the medulloblastoma cases was undertaken by a clinical paediatric neuropathologist (T.S.J.). Tumour features of anaplasia, nodularity and desmoplasia were graded for each tumour sample and histological classification was carried out according to published criteria (16-17). A sample of normal cerebellar tissue was obtained from a patient who had undergone brain surgery at GOSH for the removal of a pilocytic astrocytoma. Additional normal cerebellar total RNA samples were purchased from commercial sources.

A further set of 20 primary medulloblastoma and 10 normal cerebellar samples was used to independently validate tumour-associated splicing events by RT-PCR. All tumour samples had been previously profiled using Affymetrix 3′ arrays and classified into medulloblastoma molecular subgroups as reported in Kool et al. (3). Control samples included 6 normal adult cerebellar samples obtained from the UCL Institute of Neurology Queen Square Brain Bank, London, UK; and 4 additional RNA samples purchased from commercial sources. Details regarding sample classification and source can be found in Table S1.

RNA extraction and array hybridisation

Total RNA was isolated from frozen tissues using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality was assessed on an Agilent Bioanalyser. 1 μg of total RNA was processed and labelled using the Affymetrix GeneChip Whole Transcript Sense Target Labelling Assay as outlined in the manufacturer’s instructions. Hybridisation to Affymetrix Human Exon 1.0 ST arrays was performed for 16 hours at 45°C.

Analysis of array data

Analysis of alternative splicing was performed as described in Shah et al. (18). Briefly, exon- and gene-level signal estimates were generated using the Robust Multichip Average (RMA) algorithm (19) implemented in the Expression Console software (Affymetrix) and including only core, non cross-hybridising probe sets. Signal values were then analysed using R and Bioconductor. To reduce the generation of false positives which can be caused by uniformly non-expressed genes/exons, probe sets and transcript clusters falling into the lowest quartile of the expression signal distribution across all samples were excluded from the dataset. The Splicing Index algorithm was applied to identify exons with significantly different inclusion rates between groups of samples. Exon/gene signal ratios were compared using the moderated t-statistic of the LIMMA package (20) and observations were selected for FDR adjusted p-values < 0.01.

The necessity to filter Splice Index results to remove those probe sets with the highest likelihood of introducing false positives has been reported in several publications (6, 18, 21-22). We therefore applied a series of post-analysis filters: 1) we discarded hits corresponding to the last probe set or the final two probe sets at each end of a transcript cluster. Probe sets mapping to the 5′ and 3′ regions of a gene often fail to respond to expression changes as efficiently as those that map to the remainder of the gene, and are therefore more likely to generate false positive results (21). 2) We removed all genes with a greater than fourfold change in their level of expression between sample subgroups, as these have a tendency to produce false positives (6, 18, 23). 3) We removed genes represented by fewer than 5 probe sets, since their exon expression patterns are often more difficult to interpret (22). 4) We focused on known genes by filtering out transcript clusters with no HUGO gene symbol. 5) We selected only probe set hits with a fold change in gene-normalised expression values between sample subgroups that was higher than 1.5. All filtered results were then subjected to a detailed visual inspection to assess the likelihood that individual events represented true positives. This was achieved by examining probe set expression plots and analysing candidate exons within their genomic context using the X:Map Genome Browser (24). As previously described by Whistler et al. (22), each selected probe set was classified as yes (Y)-strong evidence of differential splicing: the candidate probe set maps to a known alternatively spliced exon or more than one adjacent probe sets behave similarly; probable (P)-single probe set mapping to an unknown alternatively spliced exon; unlikely (U)-unclear evidence of differential splicing: minor changes in probe set signal intensity or high signal variance, probe set with ambiguous transcript cluster assignment, probe set mapping to regions of overlapping transcript clusters; no (N)-expression pattern indicative of non-responsive, uniformly non-expressed or saturated probe set and no other indications of differential splicing. In some cases, inspection of candidate gene expression plots allowed the identification of probe sets whose profile was strongly indicative of differential splicing even though they did not meet the requirement for statistical significance. These probe sets were considered false negatives and were considered for further analysis. Candidate splicing events which were selected for further validation by RT-PCR all belonged to the list of probe sets designated as Y.

Exon array data are available from the ArrayExpress database (www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) under accession number E-MTAB-292.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR

0.5 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed into first strand cDNA using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and oligo(dT). Approximately 5 ng of cDNA template was amplified using Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen). Primer sequences are provided in Table S2. PCR reactions were performed for 28 to 34 cycles and PCR products were resolved on 2% agarose gels. PCR-amplified DNA bands were quantified using the ImageQuant TL v2005 software (GE Healthcare, Bucks, UK). Student’s t-test was used to compare log2 ratios between splice variants across sample groups. To verify the sequence of the different PCR products, individual PCR bands were purified from agarose gels using a QIAquick Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen) and sequenced using an Applied Biosystems 3730xl Genetic Analyser. PCR products that gave ambiguous sequencing results were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Southampton, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Following bacterial transformation, several clones were sequenced as described above.

Calculation of the Splicing Indicator value

To better visualise alternative transcript expression, we calculated the ratio between the difference and the average of the signal intensities corresponding to the two alternative splice forms. This formula generates a value between −2 and 2, which we called the Splicing Indicator. Values of −2 and 2 correspond to exclusive amplification of the skipped exon isoform or the retained exon splice form respectively.

Mouse GCP culture and mouse total cerebellum RNA samples

GCPs were isolated from 7-day-old C57BL6/J mice as described by Wechsler-Reya et al. (25) and as outlined in the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Medulloblastoma cell lines

The Daoy cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. The UW228-2 and D425 Med cell lines were the kind gift of Professor Silvia Marino (Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, London, UK). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (all from Invitrogen). Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol. The medulloblastoma cell lines were regularly checked for mycoplasma contamination using a MycoProbe mycoplasma detection kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The MycoProbe assay detects mycoplasma contaminants using a colorimetric signal amplification system which targets mycoplasma 16S ribosomal RNA. The cells were last tested in May 2010, one month before submission of the manuscript. The cell lines were authenticated as follows. The Daoy cell line was authenticated by the ATCC according to their standard protocols and the cells were used within 6 months of receipt for the experiments in this paper. The DW228-2 and D425 cell lines are not stocked in cell banks and therefore could not be compared with a reference cell line. Both cell lines are human cells and we performed RT-PCR experiments with RNA extracted from the two cell lines and PCR primer pairs specific for 20 different human genes. In all cases the PCR products were sequenced and all corresponded to known human DNA sequences. No PCR products corresponding to other mammalian species were detected.

Results

Molecular classification of tumour samples

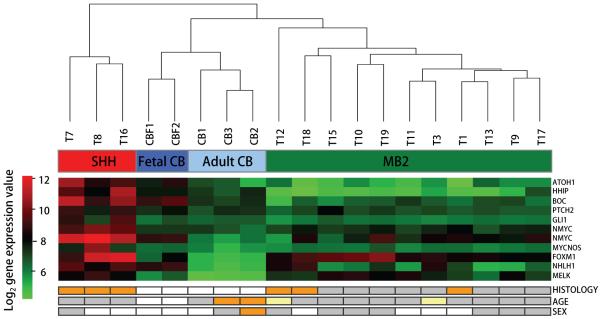

We used Affymetrix Human Exon arrays to analyse gene expression and splicing in 14 paediatric medulloblastomas and five samples of normal cerebellum. Patients’ clinical features are presented in Table S1 and summarised in Figure 1. We initially investigated gene-level expression profiles to identify samples expressing gene signatures characteristic of previously described medulloblastoma molecular subgroups. Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis of Shh signature genes (ref. 4 and Table S3) identified a well-defined group of three medulloblastomas which significantly overexpressed genes typically belonging to the Shh signalling pathway or associated with a GCP status (Figure 1). These three samples were therefore classified as Shh-driven medulloblastomas (i.e. SHH subgroup). The remaining tumour samples did not demonstrate a similarly distinct gene signature and were grouped together as medulloblastoma subgroup 2 (MB2).

Figure 1. Molecular sub-grouping of samples according to gene expression.

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering was computed on the expression levels of 523 Shh-signature genes, which correspond to the Shh-group genes in Thompson’s data series (4), according to the Affymetrix Best Match array comparison spread sheet (Table S3). The Euclidean distance metric was used. Three medulloblastoma samples segregated in a discrete cluster and were classified as Shh-driven medulloblastomas (SHH). Abnormal activation of the Shh signalling pathway in these samples was confirmed by the significant overexpression of Shh-related genes (FDR adjusted p-value < 0.01), as shown in the heat-map. Two different transcript clusters for the NMYC gene are shown. All remaining medulloblastoma samples were grouped together for further analysis (MB2). A summary of the major clinical parameters for the samples is presented underneath the heat-map. Histology: white = normal cerebellum, grey = classic medulloblastoma, orange = anaplastic medulloblastoma; Age: white = fetal, yellow = < 3 years, grey = > 3 years, orange = > 16 years; Sex: white = female, grey = male, orange = mixed pool of male/female.

Identification of tumour-associated splicing events

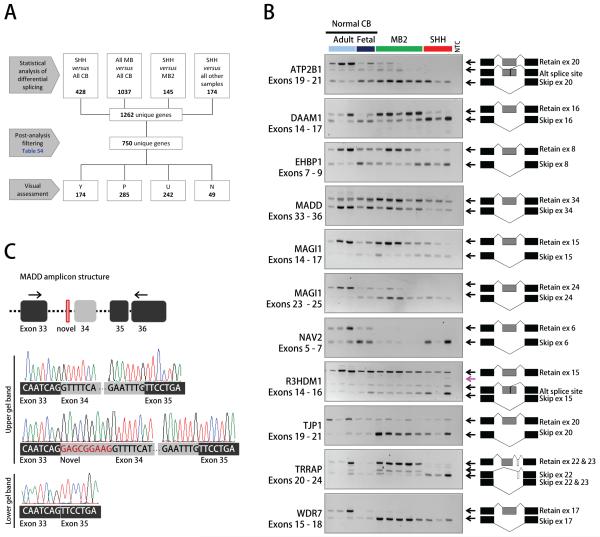

To identify splicing patterns associated with medulloblastomas, we compared exon/gene expression ratios between different sample subgroups. Several different comparisons were performed to identify splicing events associated either with medulloblastoma in general or with SHH tumours specifically (Figure 2A). A total of 1262 genes with potential alternatively spliced exons were identified, of which 750 passed the post-analysis filters. A detailed breakdown of the post-analysis filtering steps is reported in Table S4. On visual inspection, 174 candidate events were classified as Y:Yes (23.2%), 285 as P:Probable (38%), 242 as U:Unlikely (32.3%) and 49 as N:No (6.5%). Examples for each individual category are shown in Figure S1. Based on the characterisation of transcript structures using the X:Map database, 14 splicing events corresponding to known alternatively spliced cassette exons and belonging to the Y designation were selected for validation by RT-PCR on a subset of the profiled samples. At this initial point, the selected candidate events were not evaluated for their biological relevance or potential implication in cancer pathogenesis, and included two events classified as false negatives (Figure S2). Differential splicing occurring between different sample subgroups was confirmed for 11 of the 14 examples studied (Figure 2B and Table 1). In the three non-confirmed cases, only one PCR product was detected, suggesting that only one transcript form was expressed (data not shown). These events were not analysed further.

Figure 2. Identification of medulloblastoma-associated splicing events.

A, Diagram of differential splicing analysis. Numbers in each box refer to genes with at least one exon predicted to be differentially spliced. A detailed breakdown of post-analysis filtering is presented in Table S4. B, RT-PCR validation of candidate splicing events was performed on 13 of the 19 original samples profiled using exon arrays. PCR amplicons are listed below gene names. Exon structures corresponding to each amplified band are shown to the right of each gel. A pink arrow points to heteroduplexes of alternatively spliced forms. NTC, No-template control. C, Sequence analysis of MADD PCR products. Sequencing of several PCR subclones of the MADD upper gel band revealed the presence, in most cases, of an additional 9 nucleotide-long exon located upstream of the candidate cassette exon.

Table 1.

Genes alternatively spliced in medulloblastoma identified by exon array analysis and validated by RT-PCR

| Probe set ID |

Gene Symbol |

Probe set Location† |

Transcript ID | Comparison‡ | Exon Array |

RT-PCR validation** |

Alternative exon | Refs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adj p-value |

Probe set FC§ |

Gene FC∥ | Training set |

Test set | |||||||

| 3464995 | ATP2B1 | Ex 20 | ENST00000359142 | MB vs CB | 0.003 | −3.73 | 1.44 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | Frame shift (154 aa), calmodulin binding domain, early stop codon, CNS-specific |

(40) |

| 3329783 | MADD | Ex 34 | ENST00000311027 | MB vs CB | > 0.01* | 1.57 | −1.74 | 0.01 | < 0.001 | Frame shift (23 aa), late stop codon, CNS-enriched |

(49) |

| 2680306 | MAGI1 | Ex 24 | ENST00000330909 | MB vs CB | < 0.001 | −3.61 | −1.09 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | Frame shift (29 aa), early stop codon, cytoplasmic localisation, CNS-enriched |

(36-38) |

| 3323129 | NAV2 | Ex 6 | ENST00000360655 | MB vs CB | 0.009 | −5.5 | −3.42 | 0.02 | 0.008 | In frame (23 aa) | |

| 2507435 | R3HDM1 | Ex 15 | ENST00000264160 | MB vs CB | 0.004 | −1.86 | −1.12 | 0.04 | < 0.001 | In frame (85 aa), CNS-enriched | Fast DB (50) |

| 3615612 | TJP1 | Ex 20 | ENST00000346128 | MB vs CB | 0.002 | −5.13 | 1.15 | 0.007 | < 0.001 | In frame (80 aa) | |

| 3789479 | WDR7 | Ex 17 | ENST00000254442 | MB vs CB | < 0.001 | −5.46 | −1.14 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | In frame (33 aa), CNS-enriched | Fast DB (50) |

| 2680331 | MAGI1 | EX 15 | ENST00000330909 | SHH vs CB | > 0.01* | −1.7 | −1.56 | 0.03 | 0.004 | In frame (27 aa), CNS-specific | (36) |

| 3538263 | DAAM1 | Ex 16 | ENST00000351081 | SHH vs CB & MB2 | 0.009 | −5.17 | 1.96 | 0.01 | < 0.001 | In frame (10 aa), formin-homology domain, CNS-enriched |

(32, 34-35) |

| 2485003 | EHBP1 | Ex 8 | ENST00000263991 | SHH vs CB & MB2 | 0.005 | −8.88 | 1.11 | 0.003 | 0.006 | In frame (35 aa), CNS-enriched | Fast DB (50) |

| 3014461 | TRRAP | Ex 22/23 | ENST00000456197 | SHH vs CB & MB2 | 0.003 | −2.62 | −1.1 | 0.004 | < 0.001 | In frame (24 aa), CNS-enriched | Fast DB (50) |

Exons are numbered according to the Ensembl transcripts listed to the right (EnsEMBL release 56).

In several cases probe sets were identified as differentially spliced for more than one comparison. Here we report the comparison that generated the most significant difference.

Fold change in gene-normalised probe set signal values.

Fold change in gene signal values.

P-values were calculated on the log2 ratio between skipped and retained transcript forms as quantified from the agarose gels. MB, medulloblastoma (including both SHH and MB2); SHH, Shh-driven medulloblastoma; MB2, Group 2 medulloblastoma; CB, normal cerebellum; CNS, central nervous system; aa, amino acids. FAST DB is an alternative splicing database (50).

Events with an adjusted p-value > 0.01 but a profile suggestive of AS (Figure S2).

For three of the 11 experimentally validated genes (DAAM1, EHBP1 and TRRAP) the splicing pattern distinguished between SHH tumours and all of the other samples. In all of the remaining cases, all of the medulloblastomas shared a similar exon pattern which differed from that of normal adult cerebellar samples. Interestingly, normal fetal cerebellar samples typically produced splicing patterns which were more similar to the tumours than to the normal adult samples (Figure 2B).

Identification of novel splice forms

For some genes, we observed additional PCR products to those predicted by the exon array analysis. In two cases (ATP2B1 and R3HDM1) we found that an extra transcript variant was generated via an alternative 5′ splice site located within the candidate cassette exon (Figure 2B). Both novel transcript forms have been eventually annotated in EnsEMBL release 56. In the case of the TRRAP gene, the unexpected PCR product corresponded to a previously unreported splice form in which exon 22 is excluded and exon 23 is retained (Figure 2B). We also identified a novel 9 nucleotide-long exon inserted upstream of cassette exon 34 in the MADD gene (Figure 2C). Direct sequencing showed that this novel mini-exon was heterogeneously expressed across the sample-set (data not shown). All of the other extra bands detected corresponded to heteroduplexes forming between alternative PCR products (26, 27), as confirmed by PCR subcloning and sequencing.

Validation of differential splicing events in an independent set of primary medulloblastomas and in medulloblastoma cell lines

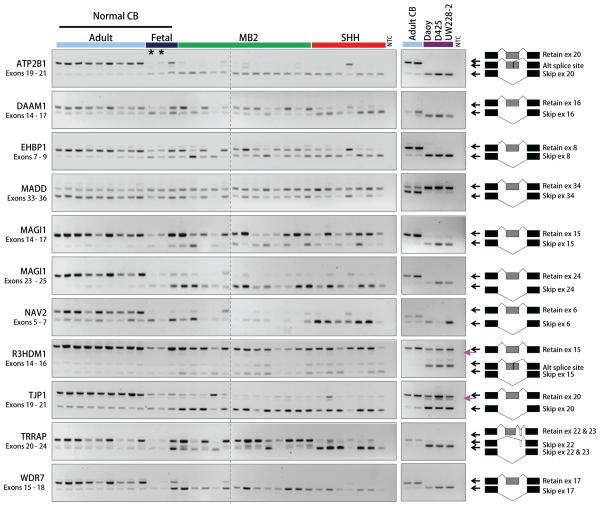

To confirm that the splicing patterns of the selected genes were characteristic of medulloblastoma in general, we analysed an independent set of 10 normal cerebellum and 20 medulloblastoma samples by RT-PCR (Figure 3). The tumours were classified into either the SHH or MB2 subgroup according to whether or not they showed a gene expression signature indicative of Shh signalling pathway activation (data not shown). Typically, the novel independent set of samples (test set) replicated the same patterns of splicing we identified in the initial set of samples (training set). We found statistically significant differences in log2 ratios of transcript forms between sample subgroups (Table 1). We also analysed splicing patterns in three human medulloblastoma cell lines (Daoy, D425 Med and UW228-2) and found that they were similar to those of primary medulloblastomas, with the cell lines preferentially expressing tumour-associated transcript forms (Figure 3).

Figure 3. RT-PCR analysis of differential splicing in an independent set of samples and in medulloblastoma cell lines.

Left panel shows RT-PCR results for a new independent set of 10 normal cerebellum and 20 medulloblastoma samples, including 7 samples belonging to the SHH subgroup (red bar). Asterisks indicate two normal fetal cerebellum samples (CBF1 and CBF2) that were included in the initial validation (Figure 2B). Right panel shows RT-PCR results for two adult normal cerebellum samples (light blue bar) and three human medulloblastoma cell lines (purple bar). Pink arrows point to heteroduplexes of alternatively spliced forms. NTC, No-template control.

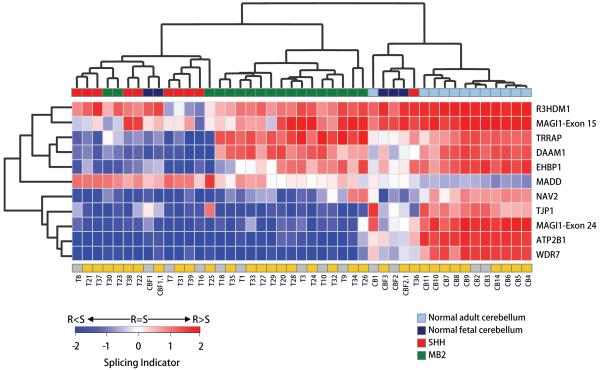

To effectively visualise alternative transcript expression, we calculated Splicing Indicator values based on the quantified signal intensities of the alternative PCR products resolved on agarose gels (as described in Materials and Methods). In cases where more than two transcript forms were amplified, the two most prominent were taken into account. Unsupervised cluster analysis was performed using the Splicing Indicator values generated for each individual sample analysed by RT-PCR (Figure 4). Most of the adult normal cerebellar samples formed a homogeneous cluster and predominantly expressed transcript forms in which the candidate exons were retained. An exception to this being the MADD gene, whose exon 34 appeared to be mostly excluded. Interestingly, the majority of SHH tumours shared similar splicing patterns, including a unique profile for those genes which were initially identified as undergoing SHH-associated splicing (DAAM1, EHBP1 and TRRAP). We also confirmed that normal fetal cerebellar samples generally expressed patterns of splicing more similar to those of tumour samples, as compared to those found in normal adult cerebella.

Figure 4. Unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis of normal cerebellum and medulloblastoma samples based on splicing patterns.

Cluster analysis was performed on the Splicing Indicator values generated for each of the 45 individual samples analysed by RT-PCR (including CBF1 and CBF2 replicates, indicated above as CBF1.1 and CBF2.1) and using the Euclidean distance metric as a measure of distance between genes/samples. Sample sub-groupings are colour-coded at the top: light blue = adult normal cerebellum; dark blue = fetal normal cerebellum, green = MB2, red = SHH. Grey and yellow boxes at the bottom indicate samples analysed in the first and second RT-PCR validation experiments respectively. S, Skipped exon splice form; R, Retained exon splice form.

Tumour-associated splicing patterns are observed during the normal development of mouse cerebellum

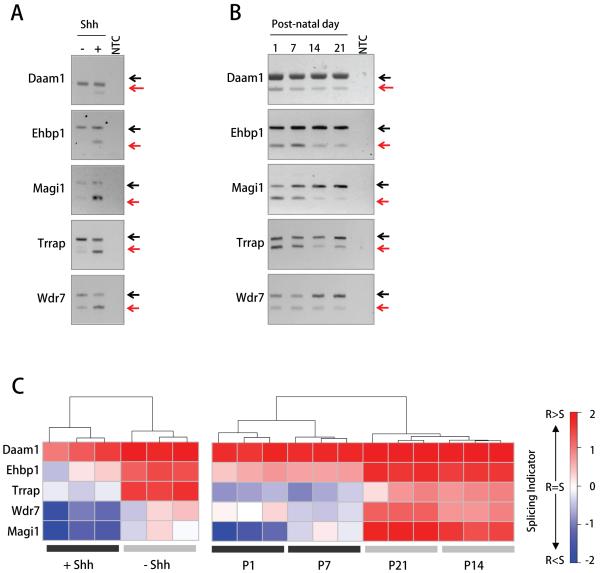

Cerebellar GCPs are the proposed cells of origin of Shh-driven medulloblastomas (15). We therefore investigated whether transcripts which showed characteristic splicing patterns in medulloblastomas were also differentially spliced in cultured GCPs. GCP primary cultures were incubated either in the presence or absence of Shh for 48 hours. In the absence of Shh, GCPs differentiate into post-mitotic cerebellar granule neurons. In the presence of Shh, GCPs continue to proliferate and maintain a neuronal precursor state (25). We analysed splicing variations in GCP cultures for seven of the candidate genes whose genomic organization was conserved between human and mouse (according to the X:Map database version 2.4). In the presence of Shh, the splicing patterns for five out of the seven genes analyzed by RT-PCR (Damm1, Ehbp1, Magi1 exon 24, Trrap, Wdr7) recapitulated the patterns observed in the human tumour samples (Figure 5A-B). That is, Shh increased the amount of cassette exon skipping that occurred. In the two remaining cases (Madd and Nav2), both transcript forms were expressed independently of Shh treatment (Figure S3).

Figure 5. Splicing variants characteristic of human medulloblastomas are expressed during normal mouse cerebellar development.

A, RT-PCR analysis of differential splicing in mouse GCP cultures maintained in the presence or in the absence of Shh for 48 hours (left panel) and in total mouse cerebellum during early post-natal development (right panel). Exon structures for each amplified band are shown to the right of each gel. Red arrows point to PCR bands corresponding to the predominant transcript forms observed in human medulloblastomas. Gels are representative of three independent experiments. NTC, No-template control. B, Quantitation of transcript isoform ratios based on the Splicing Indicator formula. *, ShhN-treated GCPs versus control, p-value < 0.05; ***, Post-natal days 1-7 versus 14-21, p-value < 0.0001. S, Skipped exon splice form; R, Retained exon splice form.

The analysis of different stages of early post-natal mouse cerebellar development showed that the switch between the two alternative transcript forms of the five validated mouse genes occurred between post-natal days 7 and 14, at the time when GCPs mature into post-mitotic neurons (Figure 5A-B). Thus, during the post-natal development of the mouse cerebellum, as the number of proliferating GCPs decreases the amount of cassette exon retention that occurs increases.

Discussion

Alternative pre-mRNA splicing makes a major contribution to the generation of protein variety in a tissue- and development-specific manner. Alterations in the normal pathways of AS have been associated with the growth and maintenance of several tumour types, and have been indicated as candidate bio-markers of tumour progression, metastasis and patient survival (7, 28, 29). In this study we applied genome-wide exon array technology to identify splicing variations that distinguish between medulloblastoma and normal cerebellum. We identified 1262 unique genes containing at least one candidate exon whose inclusion rate differed between sample subgroups. The use of post-analysis filters and visual inspection of candidate event expression plots and exon structures provided us with a list of 174 events with the highest likelihood of representing real positive hits (Table S4). This number is comparable to the number of real positive hits described in other reports in which tumour-enriched splice variants have been investigated using Affymetrix Exon arrays (8, 9). Eleven out of a total of 14 examined cassette exons belonging to this list were confirmed to undergo differential splicing by RT-PCR. All of the validated cassette exons encoded a polypeptide which would be included in the final protein product and did not contain nonsense codons (Table 1).

Although in most cases the functional significance of the AS has not yet been clarified, many of the validated genes have been previously implicated in key biological processes, such as neuronal differentiation and cancer progression. Several of the splicing events that we experimentally validated occurred in genes involved in cytoskeleton remodelling, cell morphology regulation and cell-cell interaction. DAAM1, EHBP1 and NAV2 all contain actin binding domains and have been suggested to mediate extensive reorganisation of actin structures likely affecting basic cellular functions, such as neurite growth and endocytic trafficking (30-32). DAAM1 plays an important role in the regulation of actin assembly during axon formation and outgrowth (33). Skipping of exon 16, which we confirmed to frequently occur in Shh-driven medulloblastomas, would remove 10 amino acids (DFFVNSNSKQ) from a functionally important linker sequence located between the lasso and knob structures in a formin-homology-2 domain which is required for the actin assembly activity of the DAAM1 protein (32, 34). Interestingly, the alternative splicing of DAAM1 exon 16 has been shown to be regulated during neuronal development as part of a general network of brain-enriched alternatively spliced exons whose expression contributes to promoting cell differentiation (35).

MAGI1 and TJP1 (also known as ZO-1) have been described as tight junction proteins co-localising in the apical region of polarised epithelial cells (36). However, they are both expressed in non-epithelial cells, particularly in neuronal cell types, where they may be involved in different cell processes, such as transduction of signals from the cell surface to the nucleus (36, 37). Indeed, both MAGI1 and TJP1 can localise to the nucleus of cells and are predicted to interact with a variety of protein partners (38, 39). Specifically, the exclusion of exon 24 from the mature MAGI1 mRNA results in a frame shift which generates a unique COOH-terminal sequence containing two bipartite nuclear localisation signals. This form is predominantly found in the nucleus of MDCK cells, as opposed to the two alternative transcript forms which retain exon 24 and encode proteins that mostly localise to the cytoplasm (38). Both cassette exons 15 and 24 of the MAGI1 gene are almost exclusively expressed in the brain, and it has been suggested that they might be important for neuronal specification (36).

The ATP2B1 (or PMCA1) gene encodes a plasma membrane calcium pump which is responsible for the expulsion of Ca2+ from the cytosol of eukaryotic cells and is implicated in the modulation of neurotransmitter release (40). Alternative splicing of ATP2B1 exon 20 affects the COOH-terminal tail of the protein, whereby inclusion of the cassette exon results in a frame shift which introduces an earlier translational stop codon and affects the establishment of a variety of protein-protein interactions (40). Of note, ATP2B1 exon 20 is a known target of the neuronal splicing factor Nova, which is implicated in the regulation of splicing events associated with several neuronal activities (41).

TRRAP is a highly conserved, large nuclear adaptor protein commonly found in histone acetyltransferase multi-protein complexes. It is thought to be necessary for the regulation of key chromatin processes, including DNA replication and repair, and MYC and E2F-mediated transcription (42). TRRAP has recently been reported to be necessary for the maintenance of a stem cell phenotype in embryonic and hematopoietic stem cells (43, 44) as well as for the tumourigenic potential of brain cancer initiating cells (45). We observed a very specific pattern of splicing for the TRRAP gene, with Shh-driven medulloblastomas preferentially excluding the candidate cassette exons 22 and 23 (Figures 2-4). Also, more skipping of the equivalent mouse exons was seen in Shh-treated GCPs compared to controls (Figure 5). Exons 22 and 23 encode a 24 amino acid sequence of unknown function which is inserted between the HEAT repeats and the 5th LXXLL motif in the TRRAP protein (42). It will be interesting to further investigate how insertion/exclusion of these exons alters the functioning of the TRRAP protein.

MADD (also known as IG20) encodes a death domain-containing adaptor protein which contributes to the propagation of apoptotic signals by modulating death receptor signalling. Five different exons in the MADD gene are alternatively spliced to generate seven transcript forms (Figure S4A). Interestingly, different MADD splice forms have been shown to elicit opposite cell responses, with two major splice forms promoting cancer cell survival and proliferation and at least another two associated with apoptosis (46, 47). In our study we observed that MADD exon 34 was mainly retained in medulloblastomas (Figure 4). Since the analysis of exon 34 inclusion rate alone cannot discriminate between different MADD splice variants, we further investigated the alternative splicing profile of MADD exons 13L and 16 in normal and malignant cerebellum. Compared to normal adult cerebellum, medulloblastoma samples generally expressed higher levels of the two MADD splice forms associated with increased cell survival, namely the MADD and DENN-SV forms (Figure S4B). All three of the medulloblastoma cell lines tested showed exclusive expression of the same two isoforms (Figure S4C), following a pattern previously reported for other human cancer cell lines (47).

For each validated event both alternative splice forms were detectable in the normal cerebellar samples, clearly suggesting that rather than novel splice forms, medulloblastomas expressed a significantly unbalanced ratio between transcript variants normally generated through AS in the cerebellum. Remarkably, we observed that the expression of transcript variants characteristic of human primary medulloblastomas, and in particular of the SHH tumour subgroup, depended upon Shh in in vitro cultures of mouse GCPs and during mouse normal cerebellar development (Figure 5). Several studies have reported the role of AS in inducing and regulating neuronal differentiation (30, 35, 38). This occurs through the transcriptional regulation of a variety of neuronal splicing factors and results in a switch in the splice forms that are expressed in the adult brain as compared to the developing brain, with many neuron-specific exons being incorporated into the mature mRNAs, and eventually leading to the neuronal differentiation of progenitor cells. It is plausible that the splicing pattern of at least some of the candidate genes identified through the exon array analysis results from the failure of cerebellar precursor cells to undergo neuronal differentiation, caused by the aberrant activation of oncogenic pathways, such as the Shh signalling pathway. It will therefore be interesting to investigate whether the characteristic patterns of cassette exon exclusion that we identified in human medulloblastomas may be related to a possible role of Shh in controlling the overall activity of the splicing machinery in the developing cerebellum. It will also be of interest to investigate whether subgroup-specific patterns of differential splicing also characterise the medulloblastoma subgroup with hyper-activation of the WNT signalling pathway, and the other discrete medulloblastoma molecular subgroups.

In summary, by profiling exon expression in normal and malignant cerebellum, we identified splice variants that are generally enriched in medulloblastomas or specifically associated with the Shh-driven medulloblastoma molecular subgroup. We showed that in some cases medulloblastoma-associated splicing patterns were Shh-dependent and indicative of a normal cerebellar undifferentiated phenotype. This suggests that activation of oncogenic pathways during the development of the cerebellum may lead to a failure of neuronal differentiation in part through the disruption of AS programs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sian Gibson for performing H&E staining on frozen tumour tissues, and Dr. Mark Kristiansen and Dr. Rosie Hughes for critical reading of the manuscript.

Grant support: This research was supported by the Olivia Hodson Cancer Fund and the Annabel McEnery Children’s Cancer Fund (F. Menghi). T.S. Jacques was funded by the Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity. E.C. Schwalbe was sponsored by the Katie Trust. S.C. Clifford was funded by the Samantha Dickson Brain Tumour Trust, SPARKS and the Medical Research Council. M. Barenco and M. Hubank were funded by the BBSRC (grant number BB/E008488/1). J. Ham was supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research fellowship (grant number 057700).

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Crawford JR, MacDonald TJ, Packer RJ. Medulloblastoma in childhood: new biological advances. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:1073–85. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Packer RJ, Gurney JG, Punyko JA, et al. Long-term neurologic and neurosensory sequelae in adult survivors of a childhood brain tumor: childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3255–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kool M, Koster J, Bunt J, et al. Integrated genomics identifies five medulloblastoma subtypes with distinct genetic profiles, pathway signatures and clinicopathological features. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson MC, Fuller C, Hogg TL, et al. Genomics identifies medulloblastoma subgroups that are enriched for specific genetic alterations. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1924–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson JM, Castle J, Garrett-Engele P, et al. Genome-wide survey of human alternative pre-mRNA splicing with exon junction microarrays. Science. 2003;302:2141–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1090100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark TA, Schweitzer AC, Chen TX, et al. Discovery of tissue-specific exons using comprehensive human exon microarrays. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R64. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutertre M, Lacroix-Triki M, Driouch K, et al. Exon-based clustering of murine breast tumor transcriptomes reveals alternative exons whose expression is associated with metastasis. Cancer Res. 70:896–905. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.French PJ, Peeters J, Horsman S, et al. Identification of differentially regulated splice variants and novel exons in glial brain tumors using exon expression arrays. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5635–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardina PJ, Clark TA, Shimada B, et al. Alternative splicing and differential gene expression in colon cancer detected by a whole genome exon array. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:325. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.David CJ, Manley JL. Alternative pre-mRNA splicing regulation in cancer: pathways and programs unhinged. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2343–64. doi: 10.1101/gad.1973010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pajares MJ, Ezponda T, Catena R, Calvo A, Pio R, Montuenga LM. Alternative splicing: an emerging topic in molecular and clinical oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:349–57. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferretti E, Di Marcotullio L, Gessi M, et al. Alternative splicing of the ErbB-4 cytoplasmic domain and its regulation by hedgehog signaling identify distinct medulloblastoma subsets. Oncogene. 2006;25:7267–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glassmann A, Molly S, Surchev L, et al. Developmental expression and differentiation-related neuron-specific splicing of metastasis suppressor 1 (Mtss1) in normal and transformed cerebellar cells. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li XN, Shu Q, Su JM, et al. Differential expression of survivin splice isoforms in medulloblastomas. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2007;33:67–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2006.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Read TA, Hegedus B, Wechsler-Reya R, Gutmann DH. The neurobiology of neurooncology. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:3–11. doi: 10.1002/ana.20912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eberhart CG, Kepner JL, Goldthwaite PT, et al. Histopathologic grading of medulloblastomas: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2002;94:552–60. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah SH, Pallas JA. Identifying differential exon splicing using linear models and correlation coefficients. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. Article3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bemmo A, Benovoy D, Kwan T, Gaffney DJ, Jensen RV, Majewski J. Gene expression and isoform variation analysis using Affymetrix Exon Arrays. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:529. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whistler T, Chiang CF, Lin JM, Lonergan W, Reeves WC. The comparison of different pre- and post-analysis filters for determination of exon-level alternative splicing events using Affymetrix arrays. J Biomol Tech. 2010;21:44–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Affymetrix technical note. Identifying and validating alternative splicing events: an introduction to managing data provided by GeneChip Exon Arrays. http://media.affymetrix.com/support/technical/technotes/id_altsplicingevents_tec hnote.pdf.

- 24.Yates T, Okoniewski MJ, Miller CJ. X:Map: annotation and visualization of genome structure for Affymetrix exon array analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D780–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wechsler-Reya RJ, Scott MP. Control of neuronal precursor proliferation in the cerebellum by Sonic Hedgehog. Neuron. 1999;22:103–14. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venables JP, Burn J. EASI--enrichment of alternatively spliced isoforms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e103. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zacharias DA, Garamszegi N, Strehler EE. Characterization of persistent artifacts resulting from RT-PCR of alternatively spliced mRNAs. BioTechniques. 1994;17:652–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brinkman BM. Splice variants as cancer biomarkers. Clinical Biochem. 2004;37:584–94. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skotheim RI, Nees M. Alternative splicing in cancer: noise, functional, or systematic? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1432–49. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clagett-Dame M, McNeill EM, Muley PD. Role of all-trans retinoic acid in neurite outgrowth and axonal elongation. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:739–56. doi: 10.1002/neu.20241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guilherme A, Soriano NA, Bose S, et al. EHD2 and the novel EH domain binding protein EHBP1 couple endocytosis to the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10593–605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu J, Meng W, Poy F, Maiti S, Goode BL, Eck MJ. Structure of the FH2 domain of Daam1: implications for formin regulation of actin assembly. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:1258–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matusek T, Gombos R, Szecsenyi A, et al. Formin proteins of the DAAM subfamily play a role during axon growth. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13310–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2727-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamashita M, Higashi T, Suetsugu S, et al. Crystal structure of human DAAM1 formin homology 2 domain. Genes Cells. 2007;12:1255–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calarco JA, Superina S, O’Hanlon D, et al. Regulation of vertebrate nervous system alternative splicing and development by an SR-related protein. Cell. 2009;138:898–910. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laura RP, Ross S, Koeppen H, Lasky LA. MAGI-1: a widely expressed, alternatively spliced tight junction protein. Exp Cell Res. 2002;275:155–70. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howarth AG, Hughes MR, Stevenson BR. Detection of the tight junction-associated protein ZO-1 in astrocytes and other nonepithelial cell types. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C461–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.2.C461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dobrosotskaya I, Guy RK, James GL. MAGI-1, a membrane-associated guanylate kinase with a unique arrangement of protein-protein interaction domains. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31589–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gottardi CJ, Arpin M, Fanning AS, Louvard D. The junction-associated protein, zonula occludens-1, localizes to the nucleus before the maturation and during the remodeling of cell-cell contacts. PNAS. 1996;93:10779–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strehler EE, Filoteo AG, Penniston JT, Caride AJ. Plasma-membrane Ca(2+) pumps: structural diversity as the basis for functional versatility. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:919–22. doi: 10.1042/BST0350919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jensen KB, Dredge BK, Stefani G, et al. Nova-1 regulates neuron-specific alternative splicing and is essential for neuronal viability. Neuron. 2000;25:359–71. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murr R, Vaissiere T, Sawan C, Shukla V, Herceg Z. Orchestration of chromatin-based processes: mind the TRRAP. Oncogene. 2007;26:5358–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fazzio TG, Huff JT, Panning B. An RNAi screen of chromatin proteins identifies Tip60-p400 as a regulator of embryonic stem cell identity. Cell. 2008;134:162–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loizou JI, Oser G, Shukla V, et al. Histone acetyltransferase cofactor Trrap is essential for maintaining the hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell pool. J Immunol. 2009;183:6422–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wurdak H, Zhu S, Romero A, et al. An RNAi screen identifies TRRAP as a regulator of brain tumor-initiating cell differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 6:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Efimova EV, Al-Zoubi AM, Martinez O, et al. IG20, in contrast to DENN-SV, (MADD splice variants) suppresses tumor cell survival, and enhances their susceptibility to apoptosis and cancer drugs. Oncogene. 2004;23:1076–87. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mulherkar N, Ramaswamy M, Mordi DC, Prabhakar BS. MADD/DENN splice variant of the IG20 gene is necessary and sufficient for cancer cell survival. Oncogene. 2006;25:6252–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boutz PL, Stoilov P, Li Q, et al. A post-transcriptional regulatory switch in polypyrimidine tract-binding proteins reprograms alternative splicing in developing neurons. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1636–52. doi: 10.1101/gad.1558107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li LC, Sheng JR, Mulherkar N, Prabhakar BS, Meriggioli MN. Regulation of apoptosis and caspase-8 expression in neuroblastoma cells by isoforms of the IG20 gene. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7352–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de la Grange P, Dutertre M, Correa M, Auboeuf D. A new advance in alternative splicing databases: from catalogue to detailed analysis of regulation of expression and function of human alternative splicing variants. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:180. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.