Abstract

Harmful algal blooms (HABs) cause significant economic and ecological damage worldwide. Despite considerable efforts, a comprehensive understanding of the factors that promote these blooms has been lacking, because the biochemical pathways that facilitate their dominance relative to other phytoplankton within specific environments have not been identified. Here, biogeochemical measurements showed that the harmful alga Aureococcus anophagefferens outcompeted co-occurring phytoplankton in estuaries with elevated levels of dissolved organic matter and turbidity and low levels of dissolved inorganic nitrogen. We subsequently sequenced the genome of A. anophagefferens and compared its gene complement with those of six competing phytoplankton species identified through metaproteomics. Using an ecogenomic approach, we specifically focused on gene sets that may facilitate dominance within the environmental conditions present during blooms. A. anophagefferens possesses a larger genome (56 Mbp) and has more genes involved in light harvesting, organic carbon and nitrogen use, and encoding selenium- and metal-requiring enzymes than competing phytoplankton. Genes for the synthesis of microbial deterrents likely permit the proliferation of this species, with reduced mortality losses during blooms. Collectively, these findings suggest that anthropogenic activities resulting in elevated levels of turbidity, organic matter, and metals have opened a niche within coastal ecosystems that ideally suits the unique genetic capacity of A. anophagefferens and thus, has facilitated the proliferation of this and potentially other HABs.

Keywords: genomics, proteome, comparative genomics, eutrophication

Harmful algal blooms (HABs) are caused by phytoplankton that have a negative impact on ecosystems and coastal fisheries worldwide (1–4) and cost the US economy alone hundreds of millions of dollars annually (5). The frequency and impacts of HABs have intensified in recent decades, and anthropogenic processes, including eutrophication, have been implicated in this expansion (1–3). Although there is great interest in mitigating the occurrence of HABs, traditional approaches that have characterized biogeochemical conditions present during blooms do not identify the aspects of the environment that are favorable to an individual algal species. Predicting where, when, and under what environmental conditions HABs will occur has further been inhibited by a limited understanding of the cellular attributes that facilitate the proliferation of one phytoplankton species to the exclusion of others.

Aureococcus anophagefferens is a pelagophyte that causes harmful brown tide blooms with densities exceeding 106 cells mL−1 for extended periods in estuaries in the eastern United States and South Africa (6). Brown tides do not produce toxins that poison humans but have decimated multiple fisheries and seagrass beds because of toxicity to bivalves and extreme light attenuation, respectively (6). Brown tides are a prime example of the global expansion of HABs, because these blooms had never been documented before 1985 but have recurred in the United States and South Africa annually since that time (6). Like many other HABs, A. anophagefferens blooms in shallow, anthropogenically modified estuaries when levels of light and inorganic nutrients are low and organic carbon and nitrogen concentrations are elevated (1–3).

For this study, we used an ecogenomic approach to assess the extent to which the gene set of A. anophagefferens may permit its dominance under the environmental conditions present in estuaries during brown tides. We characterized the biogeochemical conditions present in estuaries before, during, and after A. anophagefferens blooms. Sequencing this HAB genome (A. anophagefferens), we compared its gene content to those of six phytoplankton species identified through metaproteomics to co-occur with this alga during blooms events. Using this ecogenomic approach, we investigated how the gene sets of A. anophagefferens differ from the six comparative phytoplankton species and how these differences may affect the ability of A. anophagefferens to compete in the physical (e.g., light harvesting), chemical (e.g., nutrients, organic matter, and trace metals), and ecological (e.g., defense against predators and allelopathy) environment present during brown tides.

Results and Discussion

During an investigation of a US estuary, Quantuck Bay, NY, from 2007 to 2009, brown tides occurred annually from May to July, achieving abundances exceeding 106 cells mL−1 or 5 × 106 μm3 mL−1 (Fig. 1). A. anophagefferens was observed to bloom after spring diatom blooms and outcompeted small (<2 μm) eukaryotic and prokaryotic phytoplankton (e.g., Ostreococcus and Synechococcus) during summer months (Fig. 1D), a pattern consistent with prior observations (7, 8). Concurrently, dissolved inorganic nitrogen levels were reduced to <1 μM during blooms, whereas dissolved organic nitrogen levels and light extinction were elevated, resulting in a system with decreased light availability and concentrations of dissolved organic nitrogen far exceeding those of dissolved inorganic nitrogen (Fig. 1C). Metaproteomic analyses of planktonic communities were performed to identify phytoplankton that A. anophagefferens may compete with during blooms by quantifying organism-specific peptides among the microbial community. Performing such analyses on the plankton present in this estuary highlights the dominance of A. anophagefferens and coexistence of the six phytoplankton species for which complete genome sequences have been generated (Fig. 1E): two coastal diatom species, Phaeodactylum tricornutum (clone CCMP632) (9) and Thalassiosira pseudonana [clone CCMP 1335 (10) isolated from an embayment that now hosts brown tides (6)], and coastal zone isolates of Ostreococcus (O. lucimarinus and O. tauri) (11) and Synechococcus [clones CC9311 (12) and CC9902] small eukaryotic and prokaryotic phytoplankton, respectively, (Fig. 1 and Table 1). To assess the extent to which the gene set of A. anophagefferens may permit its dominance within the geochemical environment found in this estuary (Fig. 1C), the gene complement of A. anophagefferens was determined by genome sequencing and was compared with those of the six competing phytoplankton species (Fig. 1E and Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Field observations from Quantuck Bay, NY. (A) Macro- and microscopic images (Inset) of an estuary (Quantuck Bay, NY) under normal conditions on June 9, 2009 before a brown tide (note the diatom in Inset micrograph image). (B) Similar macro- and microscopic images (Inset) taken July 6, 2009 during a harmful brown tide bloom caused by A. anophagefferens (note the dominance of A. anophagefferens in Inset micrograph). (C) The dynamics of dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) and dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) and the extinction coefficient of light within seawater during the spring and summer of 2009 in Quantuck Bay. (D) The dynamics of phytoplankton during the spring and summer of 2009, a year when A. anophagefferens bloomed almost to the exclusion of other phytoplankton, including picoeukaryotes, which are often dominated by Ostreococcus sp. in estuaries that host brown tides (6–8), and Thalassiosira and Phaeodactylum, genera that are found in this system (6). The shaded regions in C and D indicate the period when A. anophagefferens blooms, highlighting that A. anophagefferens blooms when levels of DIN and light levels are low and DON levels are high and also highlighting that A. anophagefferens blooms can persist for more than 1 mo during the summer when this species dominates phytoplankton biomass inventories. (E) The dynamics of A. anophagefferens cell densities during 2007, 2008, and 2009, with the dates of samples collected for metaproteome analyses (June 26, 2007 and July 9, 2007) indicated within the dashed circled. Inset metaproteome pie chart specifically depicts the mean relative abundance of unique spectral counts of peptides matching proteins from A. anophagefferens, P. tricornutum (9), T. pseudonana (10), O. tauri (11), O. lucimarinus (11), Synechococcus (CC9311) (12), Synechococcus (CC9902), and heterotrophic bacteria.

Table 1.

Major features of the genomes of A. anophagefferens and six competing algal species: P. tricornutum (9), T. pseudonana (10), O. tauri (11), O. lucimarinus (11), Synechococcus (CC9311) (12), and Synechococcus (CC9902)

| A. anophagefferens | P. tricornutum | T. pseudonana | O. tauri | O. lucimarinus | Synechococcus (CC9311) | Synechococcus (CC9902) | |

| Cell diameter (μm) | 2.0 | 11.0 | 5.0 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Cell volume (μm3) | 6 | 61 | 88 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Genome size (Mbp) | 57 | 27 | 32 | 13 | 13 | 2.6 | 2.2 |

| Predicted gene number | 11,501 | 10,402 | 11,242 | 7,892 | 7,651 | 2,892 | 2,301 |

| Genes with known functions | 8,560 | 6,239 | 6,797 | 5,090 | 5,322 | 1,607 | 1,469 |

| Genes with Pfam domains | 6,908 | 5,398 | 5,791 | 4,763 | 4,214 | 1,636 | 1,488 |

| Genes with unique Pfam domains | 209 | 79 | 75 | 23 | 51 | 55 | 12 |

Genes with known functions were identified using Swiss-Prot, a curated protein sequence database, with an e-value cutoff of <10−5 (13). Pfam domains are sequences identified from a database of protein families represented by multiple sequence alignments and hidden Markov models (14). The compressed nature of P. tricornutum cells (11 × 2.5 μm) makes its biovolume smaller than T. pseudonana.

Although phytoplankton genome size generally scales with cell size (15, 16), A. anophagefferens (2 μm) has a larger genome (56 Mbp) and more genes (~11,500) than the six competing phytoplankton species (2.2–32 Mbp and 2,301–11,242 genes) (Table 1 and SI Appendix, Tables S1, S2, S3, and S4). Its small cell size and thus larger surface area to volume ratio allows it to kinetically outcompete larger phytoplankton for low levels of light and nutrients (17), whereas its large gene content and more complex genetic repertoire may provide a competitive advantage over other small phytoplankton with fewer genes. The A. anophagefferens genome contains the largest number of unique genes relative to the six competing phytoplankton examined here (209 vs. 12–79 unique genes) (Table 1). Many of these unique or enriched genes in A. anophagefferens are associated with light harvesting, organic matter use, and metalloenzymes as well as the synthesis of microbial predation and competition deterrents (SI Appendix, Tables S5, S6, S7, S8, S9, S10, S11, S12, S13, S14, S15, S16, and S17). These enriched and unique gene sets are involved in biochemical pathways related to the environmental conditions prevailing during brown tides (Fig. 1) and thus, are likely to facilitate the dominance of this alga during chronic blooms that plague estuarine waters.

Light Harvesting.

Phytoplankton rely on light to photosynthetically fix carbon dioxide into organic carbon, but the turbid, low-light environment characteristic of estuaries and intense shading during dense algal blooms (Fig. 1 B and C) can strongly limit photosynthesis. A. anophagefferens is better adapted to low light than the comparative phytoplankton species, which requires at least threefold higher light levels to achieve maximal growth rates (Fig. 2A). Its genome contains the full suite of genes involved in photosynthesis, including 62 genes encoding light-harvesting complex (LHC) proteins (Fig. 2A). This is 1.5–3 times more than other eukaryotic phytoplankton sequenced thus far (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Table S7) and a feature that likely enhances adaptation to low and/or dynamic light conditions found in turbid estuaries. LHC proteins bind antenna chlorophyll and carotenoid pigments that augment the light-capturing capacity of the photosynthetic reaction centers (18, 19). Twenty-six A. anophagefferens LHC genes belong to a group that has only six representatives in T. pseudonana and one representative in P. tricornutum (branch PHYMKG in Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1) but are similar to the multicellular brown macroalgae, Ectocarpus siliculosus (20). Similar LHC genes in the microalgae Emiliania huxleyi have recently been shown to be up-regulated under low light (21). We hypothesize that these LHC genes encode the major light-harvesting proteins for A. anophagefferens and that the enrichment of these proteins imparts a competitive advantage in acquiring light under the low-irradiance conditions that prevail during blooms (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 2.

Comparisons of gene compliment between A. anophagefferens and other co-occurring phytoplankton species. Aa, A. anophagefferens; Pt, P. tricornutum; Tp, T. pseudonana; Ot, O. tauri; Ol, O. lucimarinus; S1, Synechococcus clone CC9311; S2, Synechococcus clone CC9902. (A) The number of light-harvesting complex (LHC) genes present in each phytoplankton genome (red bars; left axis) and Imax, the irradiance level required to achieve maximal growth rates in each phytoplankton (black squares; right axis) are shown. Among these species, A. anophagefferens possesses the greatest number of LHC genes, achieves a maximal growth rate at the lowest level of light, and blooms when light levels are low. (B) The number of genes associated with the degradation of nitriles, asparagine, and urea in each phytoplankton genome. A. anophagefferens grows efficiently on organic nitrogen and possesses more nitrilase, asparaginase, and urease genes than other phytoplankton. (C) Interspecies comparison of the genes encoding proteins that contain the metals Se, Cu, Mo, Ni, and Co (left axis) and Semax, the selenium level (added as selenite shown as log concentrations) required to achieve maximal growth rates in A. anophagefferens, P. tricornutum, T. pseudonana, and Synechococcus (white circles; right axis). The range of dissolved selenium concentrations found in estuaries is depicted as a yellow bar on the right y axis. A. anophagefferens has the largest number of proteins containing Se, Cu, Mo, and Ni and blooms exclusively in shallow estuaries where inventories of these metals are high. SI Appendix contains details of irradiance- and Se-dependent growth data and Se concentrations in estuaries.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree constructed from amino acid sequences of predicted LHC proteins from two diatoms (P. tricornutum and T. pseudonana; black branches), two Ostreococcus species (O. tauri and O. lucimarinus; green branches), and A. anophagefferens (red branches). The tree constructed in MEGA4 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) is displayed here after manipulation of the original branch lengths in Hypertree (http://kinase.com/tools/HyperTree.html) to aid visualization of major features of the tree. None of the Aureococcus LHCs were closely related to green plastid lineage LHCs, although four belonged to a group found in both the green and red plastid lineages (group I). None of the Aureococcus LHCs clustered with the major fucoxanthin-chlorophyll binding proteins (FCP) of diatoms and other heterokonts (major FCP group). However, many Aureococcus LHCs did group with similar sequences from P. tricornutum and T. pseudonana (as well as LHCs from other red-lineage algae not included in this tree; groups A–K). There were also five groups of A. anophagefferens LHCs that were not closely related to any other LHCs (Aur1 to Aur5). Group G includes 16 LHCs from A. anophagefferens and 2 LHCs from T. pseudonana, and it shares a unique PHYMKG motif near the end of helix two, with 10 additional A. anophagefferens LHCs plus 5 more from the diatoms. Cyanobacteria such as Synechococcus do not possess LHC proteins.

Organic Matter Use.

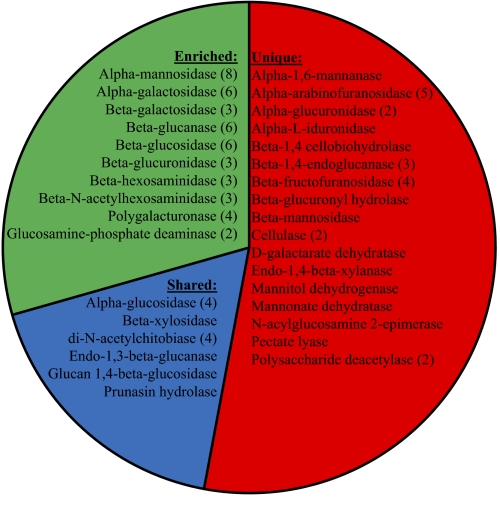

In addition to being well-adapted to low light, A. anophagefferens also outcompetes other phytoplankton in estuaries with elevated organic matter concentrations (6) (Fig. 1C), and can survive extended periods with no light (22). Consistent with these observations, the genome of A. anophagefferens contains a large number of genes that may permit the degradation of organic compounds to support heterotrophic metabolism. For example, its genome encodes proteins involved in the transport of oligosaccharides and sugars that are not found in competing phytoplankton, including genes for glycerol, glucose, and d-xylose uptake (SI Appendix, Table S8). The A. anophagefferens genome also encodes more nucleoside sugar transporters and major facilitator family sugar transporters than other comparative phytoplankton species (SI Appendix, Table S8). It is highly enriched in genes associated with the degradation of mono-, di-, oligo-, and polysaccharides as well as sulfonated polysaccharides. A. anophagefferens possesses 47 sufatase genes, including those targeting sulfonated polysaccharides such as glucosamine-(N-acetyl)-6-sulfatases, whereas the diatoms contain a total of three to four sulfatases and the comparative picoplankton contain none (SI Appendix, Table S9). A. anophagefferens also possesses many more genes involved in carbohydrate degradation than competing phytoplankton (85 vs. 4–29 genes in comparative phytoplankton), including 29 such genes present only in A. anophagefferens (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Tables S10 and S11). Collectively, these genes (SI Appendix, Tables S9, S10, S11, and S12) provide this alga with unique metabolic capabilities regarding the degradation of an array of organic carbon compounds, many of which may not be accessible to other phytoplankton. In an ecosystem setting, such a supplement of organic carbon would be critical for population proliferation within the low-light environments present in estuaries, particularly during dense algal blooms (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 4.

Genes encoding for enzymes involved in degrading organic carbon compounds in A. anophagefferens. The graph displays the portion and names of the genes encoding for functions that are unique to A. anophagefferens (red; 53%), enriched in A. anophagefferens relative to the six comparative phytoplankton (34%; green), and present at equal or lower numbers in A. anophagefferens relative to the six comparative phytoplankton (13%; blue). The number of genes present in multiple copies in A. anophagefferens is shown in parentheses. Further details regarding these genes are presented in SI Appendix, Tables S10 and S11.

A. anophagefferens, like many HABs, blooms when inorganic nitrogen levels are low but organic nitrogen levels are elevated (Fig. 1C) (1–3), and A. anophagefferens is known to efficiently metabolize organic compounds for nitrogenous nutrition (6, 23). Notably, this niche strategy is reflected within the A. anophagefferens genome, which encodes transporters specific for a diverse set of organic nitrogen compounds including urea, amino acids, purines, nucleotide sugars, nucleosides, peptides, and oligopeptides (SI Appendix, Table S8) (24). Relative to competing phytoplankton, A. anophagefferens is enriched in genes encoding enzymes that degrade organic nitrogen compounds, such as nitriles, asparagine, and urea (Fig. 2B). A. anophagefferens is also the only species among the phytoplankton genomes examined that possesses a membrane-bound dipeptidase, several histidine ammonia lyases, tripeptidyl peptidase, and several other enzymes (SI Appendix, Table S13) that could collectively play a role in metabolizing organic nitrogen compounds that are not bioavailable to other phytoplankton. Furthermore, the A. anophagefferens genome also contains enzymes that degrade amino acids, peptides, proteins, amides, amides, and nucleotides, often possessing more copies of these genes than competing phytoplankton (SI Appendix, Table S13). This characteristic, along with its unique gene set, may provide A. anophagefferens with a greater capacity to use organic compounds for nitrogenous nutrition compared with its competitors, a hypothesis supported by its dominance in systems with elevated ratios of dissolved organic nitrogen to dissolved inorganic nitrogen and the reduction in dissolved organic nitrogen concentrations often observed during the initiation of brown tides (6, 25).

Metalloenzymes.

A. anophagefferens blooms in shallow, enclosed estuaries (6) where the concentrations of metals and elements like selenium are elevated (26–28), but it never dominates deep estuaries or continental shelf regions (6) that are characterized by lower metal and trace element inventories (26–28). A. anophagefferens has a large and absolute requirement for some trace elements, such as selenium (Fig. 2C). In comparison, phytoplankton, such as Synechococcus, do not require this element, whereas others, such as T. pseudonana and P. tricornutum, have lower selenium requirements for maximal growth (Fig. 2C). The A. anophagefferens genome is consistent with these observations, being enriched in numerous classes of proteins that require metals and elements like selenium as cofactors (Fig. 2C). It possesses at least 56 genes encoding selenocysteine-containing proteins, two times the number present in the O. lucimarinus genome, which previously had the largest known eukaryotic selenoproteome (11, 29), and fourfold more than the diatom genomes (Fig. 2C). The A. anophagefferens selenoproteome includes nearly all known eukaryotic selenoproteins as well as selenoproteins that were previously described only in bacteria (29) and several selenoproteins that have never been described in any other organism (SI Appendix, Table S14). In addition, several selenoprotein families are represented by multiple isozymes (SI Appendix, Table S14). One-half of the selenoproteins are methionine sulfoxide reductases, thioredoxin reductases, glutathione peroxidases, glutaredoxins, and peroxiredoxins (SI Appendix, Table S14). Together, these enzymes help protect cells against oxidative stress in the dynamic and ephemeral conditions present in estuaries through the removal of hydroperoxides and the repair of oxidatively damaged proteins. Moreover, selenocysteine residues are often superior catalytic groups compared with cysteine (30–32), and thus, they allow A. anophagefferens to more efficiently execute multiple metabolic processes and increase its competitiveness relative to other phytoplankton in the anthropogenically modified estuaries where it blooms.

The A. anophagefferens genome is also enriched in genes encoding for molybdenum-, copper-, and nickel-containing enzymes (Fig. 2C). For example, the A. anophagefferens genome includes two times the number of genes encoding molybdenum-containing oxidases found in competing species (6 vs. 1–3 genes) (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Tables S15 and S16) and has the largest number of molybdenum-specific transporters (SI Appendix, Table S8). Similarly, A. anophagefferens possesses four times more genes that encode copper-containing proteins than its competitors (27 vs. 1–6 genes) (Fig. 2C), including 5 multicopper oxidases and 20 tyrosinase-like proteins (SI Appendix, Tables S15 and S16). Several of the A. anophagefferens tyrosinase and multicopper oxidase family proteins are heavily glycosylated (more than four glycosylation sites) (SI Appendix, Table S16) and thus, are likely secretory proteins, whereas the few present in the other comparative algal species are not. These copper-containing enzymes degrade lignin, catalyze the oxidation of phenolics, and can have antimicrobial properties (33, 34) and thus, may provide nutrition or confer protection to A. anophagefferens cells. A. anophagefferens is also the only phytoplankton species with a homolog of the CutC copper homeostasis protein, which permits efficient cellular trafficking of this metal (SI Appendix, Table S8). With three nickel-requiring ureases, A. anophagefferens has more nickel-containing enzymes than other comparative phytoplankton (Fig. 2 B and C). Consistent with its ecogenomic profile, these ureases allow A. anophagefferens to meet its daily N demand from urea, whereas other phytoplankton do not (35). Perhaps to support the synthesis and use of ureases, A. anophagefferens is the only comparative phytoplankton species with a high-affinity nickel transporter (HoxN) (36). A. anophagefferens is not universally enriched in metalloenzymes, because other phytoplankton contain equal numbers of cobalt-containing enzymes (Fig. 2C). However, the formation of blooms exclusively in shallow estuaries ensures that A. anophagefferens has access to a rich supply of the selenium, copper, and nickel required to synthesize these ecologically important and catalytically superior enzymes (30, 31, 37).

Microbial Defense.

Although genes associated with the adaptation to low light, the use of organic matter, and metals permit A. anophagefferens to dominate a specific geochemical niche found within estuaries, genes involved in the production of compounds that inhibit predators and competitors may further promote blooms (2). Although specific toxins have yet to be identified in A. anophagefferens, it is grazed at a low rate during blooms (2, 6), and its genome contains two to seven times more genes involved in the synthesis of secondary metabolites than the comparative phytoplankton genomes (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). A. anophagefferens also possesses a series of genes involved in the synthesis of putative antimicrobial compounds that are largely absent from the competing phytoplankton species (SI Appendix, Table S17). For example, A. anophagefferens has five berberine bridge enzymes involved in the synthesis of toxic isoquinoline alkaloids (38, 39) (SI Appendix, Table S17). A. anophagefferens uniquely possesses a membrane attack complex gene and multiple phenazine biosynthetase genes (SI Appendix, Table S17) that encode enzymes that may provide defense against microbes and/or protistan grazers (40, 41). There are two- to fourfold more ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in A. anophagefferens compared with competing species (112 vs. 30–54 ABC transporters) (SI Appendix, Table S8), and it is specifically enriched in ABC multidrug efflux pumps that protect cells from toxic xenobiotics and endogenous metabolites (42, 43). Finally, the A. anophagefferens genome encodes 16-fold more Sel-1 genes (130 vs. 0–8 genes) (Table S6), 4-fold more ion channels (82 vs. 1–19 ion channels) (SI Appendix, Table S8), 4-fold more protein kinases, and 2-fold more WD40 domain genes than other phytoplankton (SI Appendix, Table S6). These genes may collectively mediate elaborate cell signaling and sensing by dense bloom populations (44–46), processes that would be important for detecting competitors, predators, other A. anophagefferens cells, and the environment. Together, genes involved in the synthesis of microbial deterrents, export of toxic compounds, and cell signaling may contribute to the proliferation of this species with reduced population losses and thus, assist in promoting these HABs (2).

Conclusions.

The global expansion of human populations along coastlines has led to a progressive enrichment in turbidity (47), organic matter, including organic nitrogen (1, 47, 48), and metals (26, 28) in estuaries. Matching the expansion of HAB events around the world in recent decades, A. anophagefferens blooms were an unknown phenomenon before 1985 but have since become chronic, annual events in US and South African estuaries (6), with the potential for further expansion. The unique gene complement of A. anophagefferens encodes a disproportionately greater number of proteins involved in light harvesting and organic matter use as well as metal and selenium-requiring enzymes relative to competing phytoplankton. Collectively, these genes reveal a niche characterized by conditions (low light, high organic matter, and elevated metal levels) that have become increasingly prevalent in anthropogenically modified estuaries, suggesting that human activities have enabled the proliferation of these HABs. In estuaries that host A. anophagefferens blooms, anthropogenic nutrient loading promotes algal growth and as a result, elevated levels of organic matter and turbidity (6), whereas high concentrations of metals have been attributed to maritime paints and some fertilizers (27, 49). Collectively, these findings establish a context within which to prevent and control HABs, specifically by ameliorating anthropogenically altered aspects of marine environments that harmful phytoplankton are genomically predisposed to exploit. Like A. anophagefferens, many HAB-forming dinoflagellates are known to exploit organic forms of carbon and nitrogen for growth (1–4), grow well under low light (50), and have elevated requirements of copper, molybdenum, and selenium (51, 52). Continued ecogenomic analyses of HABs will reveal the extent to which these events can be attributed to human activities that have transformed coastal ecosystems to suit the genetic capacity of these algae.

Materials and Methods

The environmental conditions and plankton community composition within a brown tide-prone estuary (Quantuck Bay, NY) were monitored biweekly from spring to fall of 2007, 2008, and 2009. Nutrient levels were assessed by wet chemical and combustion techniques, whereas the composition of the plankton community was assessed by immunofluorescent assays, flow cytometry, and standard microscopy. Metaproteomes were generated using 2D nano-liquid chromatography tandem MS (LC-MS/MS), and spectra were analyzed using SEQUEST and DTASelect algorithms. The genome of A. anophagefferens was sequenced using the whole-genome shotgun approach using the Sanger platform assembled, with the JAZZ assembler, and annotated using JGI Annotation tools. Complete information regarding all methods used for all analyses reported here is available in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Assembly and annotations of A. anophagefferens are available from JGI Genome Portal at http://www.jgi.doe.gov/Aureococcus. Genome sequencing, annotation, and analysis were conducted by the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute supported by the Office of Science of the US Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. Efforts were also supported by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Sea Grant Awards NA07OAR4170010 and NA10OAR4170064 to Stony Brook University via New York Sea Grant, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Center for Sponsored Coastal Ocean Research Award NA09NOS4780206 to Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, National Institutes of Health Grant GM061603 to Harvard University, and National Science Foundation Award IOS-0841918 to University of Tennessee.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. ACJI00000000).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1016106108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Heisler J, et al. Eutrophication and harmful algal blooms: A scientific consensus. Harmful Algae. 2008;8:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sunda WG, Graneli E, Gobler CJ. Positive feedback and the development and persistence of ecosystem disruptive algal blooms. J Phycol. 2006;42:963–974. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson DM, et al. Harmful algal blooms and eutrophication: Examining linkages from selected coastal regions of the United States. Harmful Algae. 2008;8:39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smayda TJ. Harmful algal blooms: Their ecophysiology and general relevance to phytoplankton blooms in the sea. Limnol Oceanogr. 1997;42:1137–1153. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoagland P, Scatasta S. In: Ecology of Harmful Algae. Graneli E, Turner J, editors. Berlin: Springer; 2006. pp. 391–402. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gobler CJ, Lonsdale DJ, Boyer GL. A synthesis and review of causes and impact of harmful brown tide blooms caused by the alga, Aureococcus anophagefferens. Estuaries. 2005;28:726–749. [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Kelly CJ, Sieracki ME, Their EC, Hobson IC. A transient bloom of Ostreococcus (Chlorophyta, Prasinophyceae) in West Neck Bay, Long Island, New York. J Phycol. 2003;39:850–854. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sieracki ME, Gobler CJ, Cucci T, Thier E, Hobson I. Pico- and nanoplankton dynamics during bloom initiation of Aureococcus in a Long Island, NY bay. Harmful Algae. 2004;3:459–470. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowler C, et al. The Phaeodactylum genome reveals the evolutionary history of diatom genomes. Nature. 2008;456:239–244. doi: 10.1038/nature07410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armbrust EV, et al. The genome of the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana: Ecology, evolution, and metabolism. Science. 2004;306:79–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1101156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palenik B, et al. The tiny eukaryote Ostreococcus provides genomic insights into the paradox of plankton speciation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7705–7710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611046104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palenik B, et al. Genome sequence of Synechococcus CC9311: Insights into adaptation to a coastal environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13555–13559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602963103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boeckmann B, et al. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:365–370. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finn RD, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D211–D222. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connolly JA, et al. Correlated evolution of genome size and cell volume in diatoms (Bacillariophyceae) J Phycol. 2008;44:124–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hessen DO, Jeyasingh PD, Neiman M, Weider LJ. Genome streamlining and the elemental costs of growth. Trends Ecol Evol. 2010;25:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raven JA, Kubler JE. New light on the scaling of metabolic rate with the size of algae. J Phycol. 2002;38:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green BR, Durnford DG. The chlorophyll-carotenoid proteins of oxygenic photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:685–714. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durnford DG, et al. A phylogenetic assessment of the eukaryotic light-harvesting antenna proteins, with implications for plastid evolution. J Mol Evol. 1999;48:59–68. doi: 10.1007/pl00006445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cock JM, et al. The Ectocarpus genome and the independent evolution of multicellularity in brown algae. Nature. 2010;465:617–621. doi: 10.1038/nature09016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lefebvre SC, et al. Characterization and expression analysis of the LHCf gene family in Emiliania huxleyi (Haptophyta) reveals differential responses to light and CO2. J Phycol. 2010;46:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popels LC, MacIntyre HL, Warner ME, Yaohong Z, Hutchins DA. Physiological responses during dark survival and recovery in Aureococcus anophagefferens (Pelagophyceae) J Phycol. 2007;43:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulholland MR, Gobler CJ, Lee C. Peptide hydrolysis, amino acid oxidation, and nitrogen uptake in communities seasonally dominated by Aureococcus anophagefferens. Limnol Oceanogr. 2002;47:1094–1108. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wurch LL, Haley ST, Orchard ED, Gobler CJ, Dyhrman ST. Nutrient-regulated transcriptional responses in the brown tide-forming alga Aureococcus anophagefferens. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:468–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaRoche J, et al. Brown tide blooms in Long Island's coastal waters linked to variability in groundwater flow. Glob Change Biol Bioenergy. 1997;3:397–410. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sañudo-Wilhelmy SA, Flegal AR. Comparable levels of trace-metal contamination in two semi-enclosed embayments: San Diego Bay and South San Fransiscio Bay. Environ Sci Technol. 1993;27:1934–1936. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breuer E, Sañudo-Wilhelmy SA, Aller RC. Distributions of trace metals and dissolved organic carbon in an estuary with restricted river flow and a brown tide. Estuaries. 1999;22:603–615. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cutter GA, Cutter LS. Selenium biogeochemistry in the San Francisco Bay estuary: Changes in water column behavior. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2004;61:463–476. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lobanov AV, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of eukaryotic selenoproteomes: Large selenoproteomes may associate with aquatic life and small with terrestrial life. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R198. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stadtman TC. Selenocysteine. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:83–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hatfield DL, Gladyshev VN. How selenium has altered our understanding of the genetic code. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3565–3576. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3565-3576.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim HY, Gladyshev VN. Different catalytic mechanisms in mammalian selenocysteine- and cysteine-containing methionine-R-sulfoxide reductases. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Score AJ, Palfreyman JW, White NA. Extracellular phenoloxidase and peroxidase enzyme production during interspecific fungal interactions. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. 1997;39:225–233. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayer AM. Polyphenol oxidases in plants and fungi: Going places? A review. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:2318–2331. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan C, Glibert PM, Alexander J, Lomas MW. Characterization of urease activity in three marine phytoplankton species, Aureococcus anophagefferens, Prorocentrum minimum, and Thalassiosira weissflogii. Mar Biol. 2003;142:949–958. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolfram L, Friedrich B, Eitinger T. The Alcaligenes eutrophus protein HoxN mediates nickel transport in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1840–1843. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1840-1843.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Messerschmidt A, Huber R, Wieghart K, Poulos T. Handbook of Metalloproteins. 1–3. New York: Wiley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Facchini PJ. Alkaloid biosynthesis in plants: Biochemistry, cell biology, molecular regulation, and metabolic engineering applications. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2001;52:29–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmeller T, Latz-Brüning B, Wink M. Biochemical activities of berberine, palmatine and sanguinarine mediating chemical defence against microorganisms and herbivores. Phytochemistry. 1997;44:257–266. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(96)00545-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosado CJ, et al. A common fold mediates vertebrate defense and bacterial attack. Science. 2007;317:1548–1551. doi: 10.1126/science.1144706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pierson LS, 3rd, Gaffney T, Lam S, Gong F. Molecular analysis of genes encoding phenazine biosynthesis in the biological control bacterium. Pseudomonas aureofaciens 30–84. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;134:299–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharom FJ. ABC multidrug transporters: Structure, function and role in chemoresistance. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:105–127. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Veen HW, Konings WN. The ABC family of multidrug transporters in microorganisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1365:31–36. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mittl PRE, Schneider-Brachert W. Sel1-like repeat proteins in signal transduction. Cell Signal. 2007;19:20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quarmby LM. Signal transduction in the sexual life of Chlamydomonas. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;26:1271–1287. doi: 10.1007/BF00016474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neer EJ, Schmidt CJ, Nambudripad R, Smith TF. The ancient regulatory-protein family of WD-repeat proteins. Nature. 1994;371:297–300. doi: 10.1038/371297a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lotze HK, et al. Depletion, degradation, and recovery potential of estuaries and coastal seas. Science. 2006;312:1806–1809. doi: 10.1126/science.1128035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paerl HW, Pinckney JL, Fear JM, Peierls BL. Ecosystem responses to internal and watershed organic matter loading: Consequences for hypoxia in the eutrophying Neuse river estuary, North Carolina, USA. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1998;166:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 49.McBride MB, Spiers G. Trace element content of selected fertilizers and dairy manures as determined by ICP-MS. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 2001;32:139–156. [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacIntyre HL, et al. Mediation of benthic-pelagic coupling by microphytobenthos: An energy- and material-based model for initiation of blooms of Aureococcus anophagefferens. Harmful Algae. 2004;3:403–437. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quigg A, et al. The evolutionary inheritance of elemental stoichiometry in marine phytoplankton. Nature. 2003;425:291–294. doi: 10.1038/nature01953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doblin MA, Blackburn SI, Hallegraeff GM. Comparative study of selenium requirements of three phytoplankton species: Gymnodinium catenatum, Alexandrium minutum (Dinophyta) and Chaetoceros cf. tenuissimus (Bacillariophyta) J Plankton Res. 1999;21:1153–1169. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.