Abstract

It currently is believed that vitamin A, retinol, functions through active metabolites: the visual chromophore 11-cis-retinal, and retinoic acids, which regulate gene transcription. Retinol circulates in blood bound to retinol-binding protein (RBP) and is transported into cells by a membrane protein termed “stimulated by retinoic acid 6” (STRA6). We show here that STRA6 not only is a vitamin A transporter but also is a cell-surface signaling receptor activated by the RBP–retinol complex. Association of RBP-retinol with STRA6 triggers tyrosine phosphorylation, resulting in recruitment and activation of JAK2 and the transcription factor STAT5. The RBP–retinol/STRA6/JAK2/STAT5 signaling cascade induces the expression of STAT target genes, including suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), which inhibits insulin signaling, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), which enhances lipid accumulation. These observations establish that the parental vitamin A molecule is a transcriptional regulator in its own right, reveal that the scope of biological functions of the vitamin is broader than previously suspected, and provide a rationale for understanding how RBP and retinol regulate energy homeostasis and insulin responses.

Keywords: retinoids, adipokine, obesity, insulin-resistance

Vitamin A was recognized as an essential factor in foods about a century ago (1, 2), and a substantial body of knowledge about its biological functions has accumulated since then. It usually is believed that the parental vitamin A molecule, retinol (ROH), functions through active metabolites: 11-cis-retinal, which mediates phototransduction, and retinoic acids, which regulate gene transcription by activating specific nuclear receptors (3, 4). The main storage pool for ROH in the body is the liver, and the vitamin is secreted from this tissue bound to a 21-KDa polypeptide termed “serum retinol-binding protein” (RBP) (5). Association with RBP allows the poorly soluble vitamin to circulate in plasma, but retinol dissociates from the protein before entering cells. Interestingly, it has been reported that serum levels of RBP are markedly elevated in obese mice and humans, and that high serum RBP levels induce insulin resistance (6). How RBP suppresses insulin signaling and whether this activity is related to the function of the protein as a retinol carrier is unknown.

It was reported recently that an integral plasma membrane protein termed “stimulated by retinoic acid 6” (STRA6) mediates uptake of ROH from RBP into cells (7). Mutations in STRA6 in humans lead to defects in embryonic development, resulting in multiple malformations collectively termed “Matthew–Wood syndrome” (8, 9). Interestingly, one of the identified disease-causing mutations in STRA6, T644M, is located at the cytosolic C terminus of the protein within a sequence recognizable as an SH2 domain-binding motif (8). Such motifs, which contain a phosphotyrosine, often are used by cytokine receptors as a docking site for the transcription factors STATs. Binding of cognate extracellular ligands to cytokine receptors triggers tyrosine phosphorylation, leading to recruitment of STATs and their activating Janus kinases (JAKs). These receptors thus propagate a signaling cascade that culminates in mobilization of STATs to the nucleus where they induce transcription of specific target genes (10). The significance of the presence of a putative SH2 domain-binding motif in STRA6 and the basis for the critical need for this protein during development are unknown.

We show here that binding of retinol-bound RBP (holo-RBP) to STRA6 induces STRA6 phosphorylation, leading to recruitment and activation of JAK2 and STAT5. We show further that this signaling cascade, initiated by RBP-ROH, results in up-regulation of expression of STAT target genes including suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), which inhibits cytokine signaling mediated by the JAK/STAT pathway (11, 12), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), which controls adipocyte lipid homeostasis. The observations reveal that STRA6 functions as a cytokine receptor to transduce signalling by holo-RBP, and point at a novel mode by which retinol regulates insulin responses.

Results

RBP-ROH Triggers STRA6 Phosphorylation, Leading to Recruitment and Phosphorylation of JAK2 and STAT5.

HepG2 hepatocarcinoma cells, which endogenously express STRA6, were used to investigate whether this protein is a signaling receptor activated by RBP-ROH. Human RBP lacking its N-terminal secretion signal (hRBPΔN), which corresponds to circulating RBP (13), was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified in the presence of ROH to obtain holo-RBP (14) (Fig. S1A). Non-liganded RBP (apo-RBP) was obtained by extracting ROH from the holo-protein, and its viability was verified by fluorescence titrations (15) (Fig. S1B). As with native RBP (16), the equilibrium dissociation constant characterizing the interactions of recombinant RBP with ROH is ~100 nM. HepG2 cells were transfected with an expression vector for STRA6. Twenty-four hours later, cells were treated with precomplexed RBP-ROH (1 μM, corresponding to serum levels) and were lysed at different time points. STRA6 was immunoprecipitated, and its tyrosine phosphorylation level assessed by immunoblots. The data (Fig. 1A) show that RBP-ROH triggered a transient STRA6 phosphorylation that peaked at ~30 min. HepG2 cells then were transfected with expression vectors for STRA6 or STRA6 carrying mutations in the putative SH2 domain-binding motif, Y643F, which lacks the tyrosine residue of the motif, and T644M, lacking the threonine residue of the YTLL SH2 domain-binding motif of STRA6 and corresponding to a Matthew–Wood mutation. Cells were treated with precomplexed RBP-ROH, STRA6 was immunoprecipitated, and its tyrosine phosphorylation level was assessed (Fig. 1B). RBP-ROH increased the level of tyrosine phosphorylation of STRA6 but not of the mutant counterparts. RBP-ROH also induced an association between STRA6 and STAT5 (Fig. 1 C–E). As with growth hormone and insulin, which are known to activate STAT5, RBP-ROH increased STAT5 phosphorylation (Fig. 1F). Neither ROH nor RBP alone was effective (Fig. 1G), establishing that the activity was exerted specifically by holo-RBP and verifying that it did not emanate from the presence of bacterial contaminants in the recombinant protein preparations. RBP-ROH treatment did not alter the phosphorylation level of either STAT3 or STAT1 (Fig. S1 C and D). Similar to the pattern of STRA6 phosphorylation, and as expected from a bona fide signaling event, phosphorylation of STAT5 induced by RBP-ROH was transient (Fig. 1H). Ectopic overexpression of STRA6 enhanced both basal and RBP-ROH–induced STAT5 phosphorylation, whereas expression of the STRA6-T644M mutant abolished the effect (Fig. 1I). RBP-ROH also induced association of STRA6 with JAK2 (Fig. 1J) and triggered JAK2 phosphorylation (Fig. 1K). The phosphorylation of JAK2 in response to RBP-ROH was enhanced upon overexpression of STRA6 (Fig. 1K), and decreasing the expression level of JAK2 inhibited RBP-ROH–induced STAT5 phosphorylation (Fig. S1F). These observations indicate that RBP-ROH activates a signaling cascade mediated by STRA6, JAK2, and STAT5.

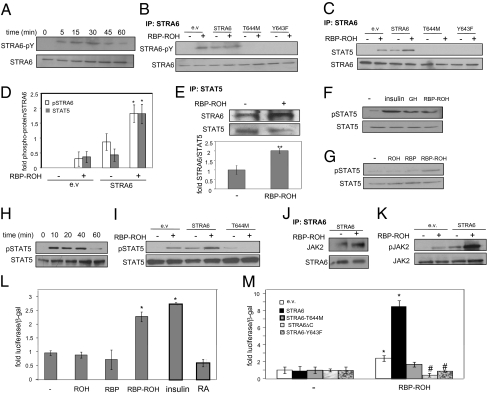

Fig. 1.

RBP-ROH induces STRA6 phosphorylation, triggering recruitment and activation of JAK2 and STAT5. (A) HepG2 cells were transfected with a vector harboring STRA6. Cells were treated with RBP-ROH (1 μM) 24 h after transfection and lysed at denoted times. STRA6 was immunoprecipitated, and precipitates were blotted for phosphor-tyrosine. (B) HepG2 cells were transfected as denoted. Similar overexpression of proteins was verified for (Fig. S2A). Cells were treated with RBP-ROH (1 μM; 15 min), STRA6-immunoprecipitated, and blotted for phospho-tyrosine. (C) HepG2 cells were transfected as denoted. STRA6 precipitated, and precipitates were blotted as indicated. (D) Quantification of bands in B and C in three independent experiments. (*P = 0.05 vs. STRA6-transfected nontreated cells.) (E) (Upper) HepG2 cells were treated as denoted, STAT5 immunoprecipitated, and precipitates blotted for STRA6 and total STAT5. (Lower) Quantification of bands in three independent experiments. (**P = 0.01.) (F) HepG2 cells were treated with insulin (15 min, 25 nM), growth hormone (GH, 500 ng), or RBP-ROH. Lysates were immunoblotted for phosphorylated STAT5 (pSTAT5, Y694) and total STAT5. (G) HepG2 cells were treated with denoted ligands (1 μM; 15 min), and lysates blotted for denoted proteins. (H) Cells were treated with RBP-ROH and lysates blotted for pSTAT5 (pY694) and total STAT5. (I) Cells were transfected as denoted and treated with RBP-ROH (1 μM; 15 min) and lysates were immunoblotted as denoted. (J) HepG2 cells were transfected with a STRA6-encoding vector, treated with RBP-ROH (1 μM; 15 min), lysed, and STRA6 was immunoprecipitated. Precipitates were immunoblotted for JAK2. (K) HepG2 cells were transfected as denoted, treated with RBP-ROH (1 μM; 15 min), lysed, and immunoblotted for pJAK2 (Y1007/1008) and total JAK2. (L and M) HepG2 cells were cotransfected with a luciferase reporter driven by STAT response elements and an expression vector for β-galactosidase. (L) Cells were treated with denoted ligands (1 μM), or insulin (5 nM). Cells were lysed 25 h later, and luciferase activity was measured and normalized to β-galactosidase. (mean ± SEM; *P < 0.02 vs. nontreated controls; n = 3.) (M) Transactivation assays using cells transfected with denoted vectors. Cells were treated with RBP-ROH for 24 h, and luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase. (mean ± SEM; *P < 0.02 vs. nontreated controls; #P < 0.05 vs. RBP-ROH–treated cells transfected with an empty vector; n = 3.)

RBP-ROH Enhances the Transcriptional Activity of STAT5.

Transactivation assays using a luciferase reporter driven by STAT5 response elements were carried out to examine the effect of RBP-ROH on the transcriptional activity of STAT. HepG2 cells were treated with ROH, RBP, RBP-ROH, or RA, an ROH metabolite that regulates transcription by activating nuclear receptors (4, 17, 18). Insulin, an established STAT activator (19), was used as a positive control. Insulin and RBP-ROH induced reporter activity, but RBP, ROH, and RA did not (Fig. 1L). The activation was enhanced upon overexpression of STRA6 (Fig. 1M) and was inhibited upon decreasing the expression level of the receptor (Fig. S1H). STRA6 variants lacking the SH2 domain-binding motif (Y643F, T644M, ΔC) inhibited the ability of RBP-ROH to activate STAT (Fig. 1M).

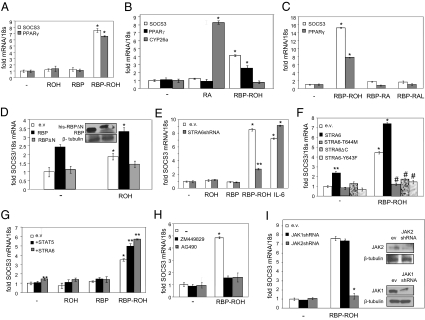

The ability of RBP-ROH to activate STAT was examined further by monitoring the expression of two endogenous STAT target genes: SOCS3 (20) and PPARγ (21). RBP-ROH, but not ROH or RBP, up-regulated the expression of both genes (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2B). RA efficiently induced Cyp26a, a target gene for the RA receptor RAR, but did not affect the expression of the STAT targets (Fig. 2B), demonstrating that RA is transcriptionally active in these cells but is not involved in the RBP-ROH response. In addition to ROH, RBP also can bind the vitamin A metabolites retinal (RAL) and RA (16). However, complexes of RBP with either RAL or RA did not activate STAT (Fig. 2C), nor was STAT activated by RAL alone (Fig. S2C). To examine the location from which RBP-ROH exerts its activity, cells were transfected with expression vectors for RBP, which is secreted into the medium in the form of holo-RBP and can function extracellularly, or with RBP lacking its secretion signal (RBPΔN), which is trapped in the cells. Ectopic expression of RBP induced SOCS3, and treatment with ROH further enhanced the response. In contrast, no effect was observed in cells that expressed RBPΔN (Fig. 2D), indicating that RBP-ROH activated STAT through extracellular activities. In agreement with these results, treatment of HepG2 cells with conditioned medium collected from cells that ectopically overexpressed RBP induced SOCS3, whereas medium from RBPΔN-expressing cells did not (Fig. S2D). Attesting to the specific involvement of STRA6 in transcriptional activation by RBP-ROH, decreasing the expression level of the receptor inhibited activation of STAT by RBP-ROH but not by another JAK/STAT activator, IL-6 (Fig. 2E). In addition, overexpression of STRA6 increased the basal expression and enhanced the RBP-ROH response of both SOCS3 (Fig. 2F) and PPARγ (Fig. S3A). Interestingly, the expression levels of these genes in cells overexpressing STRA6 mutants lacking the SH2 domain-binding motif were lower than in control cells, indicating the mutants exert dominant negative activities (Fig. 2F and Fig. S3A). The molecular mechanism by which these mutants interfere with STRA6 signaling remains to be clarified. Overexpression of STAT5 up-regulated SOCS3 and PPARγ (Fig. 2G and Fig. S3B). Two synthetic JAK inhibitors, AG490 and ZM449289, which efficiently inhibited up-regulation of SOCS3 by IL-6 (Fig. S3C), also abolished the ability of RBP-ROH to activate STAT (Fig. 2H and Fig. S3D). Decreasing the expression level of JAK2, but not of JAK1, inhibited RBP-ROH–induced up-regulation of SOCS3 (Fig. 2I) and PPARγ (Fig. S3E). Taken together, these observations establish that RBP-ROH activates STAT5 through a pathway mediated by STRA6 and JAK2.

Fig. 2.

RBP-ROH activates STAT in a STRA6- and JAK2-mediated fashion. (A) HepG2 cells were treated with denoted ligands (1 μM; 4 h). SOCS3 and PPARγ mRNA were measured by qPCR. (mean ± SEM; *P < 0.01 vs. nontreated controls; n = 3.) (B) HepG2 cells were treated with RBP-ROH or RA (1 μM; 4 h). mRNA for SOCS3, PPARγ, and CYP26a were measured by qPCR. (mean ± SEM; *P < 0.02 vs. nontreated controls; n = 3.) (C) Cells were treated with denoted ligands (1 μM; 4 h). mRNA for SOCS3 and PPARγ were measured by qPCR. (mean ± SEM; *P < 0.01 vs. nontreated controls; n = 3.) (D) Cells were transfected with expression vectors for RBP or histidine-tagged RBP lacking its secretion signal (his-RBPΔN). Cells were treated with vehicle or ROH (1 μM; 4 h), and SOCS3 mRNA was measured by qPCR. (mean ± SEM; *P < 0.01 vs. corresponding nontreated controls; n = 3.) (Inset) Immunoblots demonstrating overexpression of denoted proteins. (E) Cells were transduced as denoted. Down-regulation of STRA6 was verified by qPCR (Fig. S1G). Forty-eight hours later, cells were treated with ROH, RBP, RBP-ROH (1 μM), or IL-6 (5 ng) for 4 h. SOCS3 mRNA was measured by qPCR. (mean ± SEM; *P < 0.01 vs. nontreated controls; **P < 0.02 vs. RBP-ROH–treated cells transfected with empty vector; n = 3.) (F) HepG2 cells were transfected as denoted. Similar overexpression of proteins was verified by immunoblots (Fig. S2A). Cells were treated with RBP-ROH (1 μM; 4 h). (mean ± SEM; *P < 0.01 vs. nontreated controls; **P < 0.05 vs. nontreated cells transfected with empty vector; #P < 0.05 vs. RBP-ROH–treated cells transfected with empty vector; n = 3.) (G) Cells were transfected as denoted. Overexpression was verified by qPCR (Fig. S1F). Cells were treated with denoted ligands (1 μM; 4 h) 48 h after transfection. SOCS3 mRNA was measured. (Mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05 vs. nontreated cells transfected with empty vector; **P < 0.05 vs. RBP-ROH–treated cells transfected with empty vector; n = 3.) (H) Cells were pretreated with the JAK inhibitors AG490 or ZM449829 (50 μM) for 24 h and then were treated with RBP-ROH (1 μM; 4 h). SOCS3 mRNA was measured. (Mean ± SEM; *P < 0.01 vs. nontreated cells; n = 3.) (I) Cells were transfected with an empty lentiviral vector or a lentiviral vector harboring denoted shRNAs. Cells were treated with RBP-ROH (1 μM; 4 h) 48 h later. SOCS3 mRNA was measured (mean ± SEM; *P < 0.01 vs. RBP-ROH–treated cells transfected with empty vector; n = 3.) (Insets) Immunoblots demonstrating down-regulation of JAKs.

RBP-ROH/STRA6/STAT5 Pathway Enhances Triglyceride Accumulation and Impairs Insulin Responses.

The ability of RBP-ROH to activate a JAK/STAT pathway also was examined in adipocytes. To this end, the well-established cultured adipocyte cell model NIH 3T3-L1 was used. Cells were induced to differentiate by a standard protocol (22), and differentiation was verified by monitoring lipid accumulation (Fig. S4A) and examining the expression of the adipocyte marker FABP4 (22). Preadipocytes displayed very low levels of STRA6 and RBP, but both genes were markedly induced during differentiation (Fig. S5A). In accordance with the expression of STRA6, RBP-ROH had little effect in preadipocytes (Fig. S5B) but effectively triggered phosphorylation of STAT5 and JAK2 (Fig. S5C) and up-regulated the expression of SOCS3 and PPARγ (Fig. S5 D–F) in mature adipocytes. The protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) did not inhibit the induction of the STAT target genes by RBP-ROH (Fig. S5 D and E), demonstrating that the activity represented a direct response. Similar to the behavior in HepG2 cells, decreasing the expression of either STRA6 or STAT5 abolished the ability of RBP-ROH to up-regulate SOCS3 and PPARγ in adipocytes (Fig. S5 G and H). RA did not affect SOCS3 expression, further demonstrating that this metabolite is not involved in the pathway (Fig. S5G).

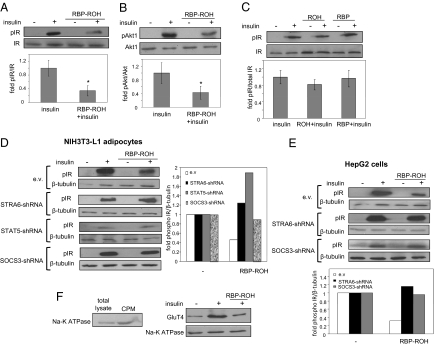

The STAT target gene PPARγ is a key regulator of adipose lipid storage (23). In accordance with up-regulation of this protein, treatment of adipocytes with RBP-ROH increased triglyceride accumulation by the cells and did so in a STRA6-dependent manner (Fig. S5I). Down-regulation of RBP in these cells reduced their lipid content (Fig. S6A). Similar effects were observed in HepG2 cells (Fig. S6 B and C). SOCS3 is a potent inhibitor of insulin receptor-mediated signaling (24, 25). Indeed, treatment of adipocytes with RBP-ROH inhibited insulin-induced activation of insulin receptor, monitored by insulin receptor autophosphorylation and by phosphorylation of the insulin receptor downstream effector Akt1 (26) (Fig. 3 A–C). Decreasing the expression levels of STRA6 or STAT5 (Fig. S4 B–D), which abolished the ability or RBP-ROH to induce SOCS3 (Fig. 2F and Fig. S4F), or decreasing the expression level of SOCS3 (Fig. S4E) abrogated the inhibition (Fig. 3D). Similar effects were observed in HepG2 cells (Fig. 3E). Another hallmark of insulin activity is the mobilization of the glucose transporter GluT4 to plasma membranes. Adipocytes were pretreated with vehicle or with RBP-ROH for 8 h and then were treated with insulin (20 nM, 25 min), and a fraction enriched in plasma membranes was isolated (27). Immunoblotting the fraction for GluT4 demonstrated that RBP-ROH inhibited insulin-induced mobilization of GluT4 to plasma membranes (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

The RBP-ROH/STRA6/STAT5 pathway impairs insulin responses. (A and B) Differentiated adipocytes were treated with insulin (20 nM; 25 min) or RBP-ROH (1 μM; 8 h) or were pretreated with RBP-ROH for 8 h before treatment with insulin. (Upper) Lysates were immunoblotted for phosphorylated insulin receptor (pIR-Y1146) and total insulin receptor (IR) (A) or phosphorylated Akt (pAkt1-S473) and total Akt1 (B). (Lower) Quantification of phosphorylated/total proteins. (Data shown are mean ± SEM; #P < 0.02 vs. controls not pretreated with RBP-ROH; n = 3. (C) Differentiated adipocytes were treated with ROH or RBP (1 μM; 8 h) and then were treated with insulin (20 nM; 25 min.). (Upper) Lysates were immunoblotted as denoted. (Lower) Quantification of immunoblots. (Data shown are mean ± SEM; n = 3.) (D and E) Differentiated adipocytes (D) or HepG2 cells (E) were transduced for 5 d with lentiviruses harboring the denoted shRNAs. Decreased expression of target proteins was verified by qPCR and/or immunoblots (Figs. S3E, S4B, and S5 C and D). Cells were treated with insulin (20 nM; 25 min) or RBP-ROH (1 μM; 8 h) or were pretreated with RBP-ROH for 8 h before treatment with insulin. Lysates were immunoblotted as denoted in left panel in D and upper panel in E. Experiments were performed twice with similar results. Right panel in D and lower panel in E show quantification of data, mean of two independent experiments. (F) Differentiated adipocytes were treated with vehicle or insulin (20 nM; 25 min) or were pretreated with RBP-ROH (1 μM; 8 h) before treatment with insulin. Crude plasma membrane fractions (cpm) were obtained (27). (Left) Immunoblots showing enrichment of Na-K ATPase in cpm. (Right) Immunoblots of GluT4 in cpm. The plasma membrane marker Na-K ATPase served as a loading control.

RBP Induces the Expression of STAT Target Genes and Inhibits Insulin Signaling in STRA6-Expressing Tissues in Vivo.

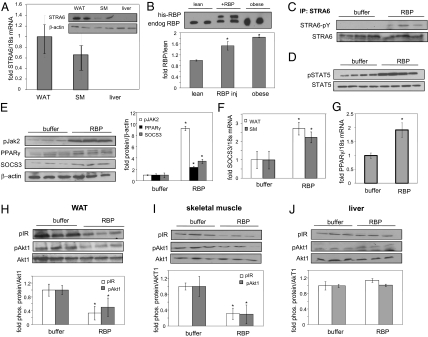

In mice, STRA6 is expressed in white adipose tissue and skeletal muscle but not in liver (Fig. 4A) (28). We injected 10-wk-old C57BL/6 mice with RBP (12.5 mg/mL, 80 μL) intraperitoneally three times at 2-h intervals. Mice were killed 1 h after the last injection. Blood levels of RBP were assessed in lean mice, lean mice injected with RBP, and mice that were fed a high fat/high carbohydrate diet for 18 wk and were obese and insulin resistant (22). As previously reported (6), serum RBP levels were about twofold higher in obese mice than in lean animals (Fig. 4B). Serum of RBP-injected mice displayed two bands, corresponding to endogenous and recombinant RBP, with total RBP approximating the level observed in obese animals. Hence, the injection elevated serum RBP within a physiologically meaningful range. Treatment of mice with RBP enhanced the phosphorylation of STRA6, STAT5, and JAK2 in adipose tissue (Fig. 4 C–E), up-regulated the expression of SOCS3 in adipose tissue and muscle (Fig. 4 E and F), and induced the expression of adipose PPARγ (Fig. 4G). RBP treatment also decreased the levels of phosphorylation of insulin receptor and Akt1 in both adipose tissue and muscle (Fig. 4 H and I). Strikingly, although RBP activated the JAK2/STAT5 pathway and inhibited insulin signaling in these STRA6-expressing tissues, it had no effect on the phosphorylation status of STAT5 (Fig. S7A), the expression of SOCS3 and PPARγ (Fig. S7B), or the level of phosphorylation of insulin receptor or Akt1 (Fig. 4J) in the liver, which does not express the receptor (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

RBP triggers phosphorylation of STRA6, STAT5, and JAK2, up-regulates the expression of STAT target genes, and represses insulin signaling in vivo. (A) STRA6 mRNA in white adipose tissue (WAT), skeletal muscle (SM), and liver, measured by qPCR. (Data shown are mean ± SEM in three mice.) (Inset) Immunoblots of STRA6 in white adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and liver in two mice. (B) (Upper) Immunoblots of serum RBP in lean and obese mice and in lean mice injected with RBP. Results from two animals per group are shown. (Lower) Quantification of RBP in plasma. (Data shown are mean ± SEM; *P < 0.03 vs. lean mice; n = 3 mice per group.) (C) STRA6 was immunoprecipitated (IP) from white adipose tissue of three control (buffer) and three RBP-injected mice and immunoblotted for phospho-tyrosine. (D) Immunoblots of pSTAT5 and total STAT5 in white adipose tissue from four control (buffer) and four RBP-injected mice. (E) (Left) Immunoblots of pJAK2, PPARγ, and SOCS3 in WAT from three control (buffer) and three RBP-injected mice. (Right) Quantification of denoted protein normalized to β-actin. (*P < 0.05 vs. buffer-injected controls.) (F) SOCS3 mRNA in white adipose tissue and skeletal muscle of control (buffer) and RBP-injected mice. (Data shown are mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05 vs. buffer-injected mice; n = 3 per group.) (G) PPARγ mRNA in white adipose tissue of mice injected with buffer or RBP. (Data shown are mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05 vs. buffer-injected mice; n = 4 per group.) (H–J) (Upper) Phosphorylation levels of insulin receptor and Akt1 in white adipose tissue (H), skeletal muscle (I), and liver (J) in mice injected with buffer or RBP. (Lower) Quantification of band intensities normalized to total Akt1. (Data shown are mean ± SEM; *P < 0.05; n = 3 per group.)

Discussion

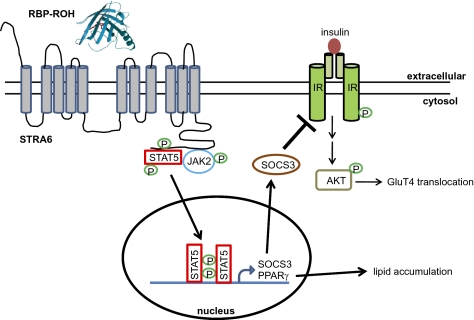

The findings described here establish that, in addition to being a ROH transporter, STRA6 also functions as a surface signaling receptor. As depicted in Fig. 5, the data demonstrate that RBP-ROH serves as an extracellular ligand to trigger tyrosine phosphorylation in the cytosolic domain of STRA6. In turn, activated STRA6 propagates a JAK2/STAT5 cascade that culminates in induction of STAT target genes. RBP-ROH thus joins the more than 30 cytokines, hormones, and growth factors that signal through surface receptors associated with JAKs and STATs (10). The identification of RBP-ROH as an activator for a STRA6/JAK2/STAT5 cascade which induces the expression of the well-known inhibitor of insulin signaling SOCS3, provides a molecular basis for the observations that RBP inhibits insulin responses (6) as well as for the recent report that SNPs in STRA6 are associated with type 2 diabetes (29). The pathway also may be involved in other biological functions. For example, the observations that a T644M STRA6 mutation, which impairs RBP-ROH signaling, results in defects in embryonic development (8) suggest that the pathway may be involved in embryogenesis. In addition, given that STATs are key regulators of cell growth, migration, and survival (30, 31) and that the expression of STRA6 is up-regulated in multiple types of cancers (32), RBP-ROH may be involved in cancer development. These observations indicate that the spectrum of the biological activities of vitamin A is much broader than previously suspected. The complete scope of these activities, as well as the relationship between the function of STRA6 as a vitamin A transporter and its role as a signaling receptor, remain to be explored.

Fig. 5.

Model of the RBP-ROH/STRA6/JAK/STAT pathway. Binding of RBP-ROH to the extracellular moiety of STRA6 triggers tyrosine phosphorylation within an SH2 domain-binding motif in the receptor's cytosolic domain. Phosphorylated STRA6 recruits and activates JAK2, which, in turn, phosphorylates STAT5. Activated STAT5 translocates to the nucleus to regulate the expression of target genes, including SOCS3, which inhibits insulin signaling, and PPARγ, which enhances lipid accumulation. The model of STRA6 (GeneID 64220RBP) was generated using software http://bp.nuap.nagoya-u.ac.jp/sosui. The 3D structure of holo-RBP (GenBank accession no. DAA14765.1) was solved as described in ref. 33.

Materials and Methods

Details concerning reagents and plasmids and cells, and protocols used in quantitative PCR analyses, mutagenesis, and transactivation assays are described in SI Materials and Methods. hRBPDN was expressed in E. coli and purified as described (14), and protein viability was ascertained by fluorescence titrations (15). Crude plasma membranes were isolated as in ref. 27. For additional details, see SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yin Huang for assistance in cloning. We are grateful to W. Blaner, J. Schwartz, S. Vogel, and L. Yu-Lee for constructs and antibodies. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK060684 and CA107013 (to N.N.) and KO1-DK077915 (to H.J.). D.C.B. was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant DK073195T32. The Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center of the Case Western Reserve University is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK59630.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1011115108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.McCollum EV, Davis M. The necessity of certain lipins in the diet during growth. J Biol Chem. 1913;15:167–175. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osborne TB, Mendel LB. The vitamins in green foods. J Biol Chem. 1919;37:187–200. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noy N. In: Vitamin A Biochemical, Physiological, and Molecular Aspects of Human Nutrition. 2nd Ed. Stipanuk MH, editor. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schug TT, Berry DC, Shaw NS, Travis SN, Noy N. Opposing effects of retinoic acid on cell growth result from alternate activation of two different nuclear receptors. Cell. 2007;129:723–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noy N. Retinoid-binding proteins: Mediators of retinoid action. Biochem J. 2000;348:481–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Q, et al. Serum retinol binding protein 4 contributes to insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2005;436:356–362. doi: 10.1038/nature03711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawaguchi R, et al. A membrane receptor for retinol binding protein mediates cellular uptake of vitamin A. Science. 2007;315:820–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1136244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasutto F, et al. Mutations in STRA6 cause a broad spectrum of malformations including anophthalmia, congenital heart defects, diaphragmatic hernia, alveolar capillary dysplasia, lung hypoplasia, and mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:550–560. doi: 10.1086/512203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golzio C, et al. Matthew-Wood syndrome is caused by truncating mutations in the retinol-binding protein receptor gene STRA6. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:1179–1187. doi: 10.1086/518177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darnell JE, Jr, Kerr IM, Stark GR. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science. 1994;264:1415–1421. doi: 10.1126/science.8197455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Starr R, et al. A family of cytokine-inducible inhibitors of signalling. Nature. 1997;387:917–921. doi: 10.1038/43206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croker BA, Kiu H, Nicholson SE. SOCS regulation of the JAK/STAT signalling pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:414–422. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soprano DR, Pickett CB, Smith JE, Goodman DS. Biosynthesis of plasma retinol-binding protein in liver as a larger molecular weight precursor. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:8256–8258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie Y, Lashuel HA, Miroy GJ, Dikler S, Kelly JW. Recombinant human retinol-binding protein refolding, native disulfide formation, and characterization. Protein Expr Purif. 1998;14:31–37. doi: 10.1006/prep.1998.0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cogan U, Kopelman M, Mokady S, Shinitzky M. Binding affinities of retinol and related compounds to retinol binding proteins. Eur J Biochem. 1976;65:71–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noy N, Slosberg E, Scarlata S. Interactions of retinol with binding proteins: Studies with retinol-binding protein and with transthyretin. Biochemistry. 1992;31:11118–11124. doi: 10.1021/bi00160a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chambon P. A decade of molecular biology of retinoic acid receptors. FASEB J. 1996;10:940–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw N, Elholm M, Noy N. Retinoic acid is a high affinity selective ligand for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta/delta. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41589–41592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300368200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen J, Sadowski HB, Kohanski RA, Wang LH. Stat5 is a physiological substrate of the insulin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2295–2300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krebs DL, Hilton DJ. SOCS proteins: Negative regulators of cytokine signaling. Stem Cells. 2001;19:378–387. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-5-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dentelli P, et al. Formation of STAT5/PPARgamma transcriptional complex modulates angiogenic cell bioavailability in diabetes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:114–120. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.172247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berry DC, Noy N. All-trans-retinoic acid represses obesity and insulin resistance by activating both peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor beta/delta and retinoic acid receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3286–3296. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01742-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kersten S, Desvergne B, Wahli W. Roles of PPARs in health and disease. Nature. 2000;405:421–424. doi: 10.1038/35013000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emanuelli B, et al. SOCS-3 is an insulin-induced negative regulator of insulin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15985–15991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.15985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emanuelli B, et al. SOCS-3 inhibits insulin signaling and is up-regulated in response to tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the adipose tissue of obese mice. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47944–47949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104602200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wing SS. The UPS in diabetes and obesity. BMC Biochem. 2008;9(Suppl 1):S6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-9-S1-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Souza EP, et al. Maternal protein restriction during early lactation induces GLUT4 translocation and mTOR/Akt activation in adipocytes of adult rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E626–E636. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00439.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouillet P, et al. Developmental expression pattern of Stra6, a retinoic acid-responsive gene encoding a new type of membrane protein. Mech Dev. 1997;63:173–186. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nair AK, Sugunan D, Kumar H, Anilkumar G. Case-control analysis of SNPs in GLUT4, RBP4 and STRA6: Association of SNPs in STRA6 with type 2 diabetes in a South Indian population. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leeman RJ, Lui VW, Grandis JR. STAT3 as a therapeutic target in head and neck cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2006;6:231–241. doi: 10.1517/14712598.6.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quesnelle KM, Boehm AL, Grandis JR. STAT-mediated EGFR signaling in cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:311–319. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szeto W, et al. Overexpression of the retinoic acid-responsive gene Stra6 in human cancers and its synergistic induction by Wnt-1 and retinoic acid. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4197–4205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newcomer ME, et al. The three-dimensional structure of retinol-binding protein. EMBO J. 1984;3:1451–1454. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.