Abstract

Purpose

The goal of this study was to comprehensively define the incidence of mutations in all exons of PIK3CA in both endometrioid endometrial cancer (EEC) and non-endometrioid endometrial cancer (NEEC).

Experimental design

We resequenced all coding exons of PIK3CA and PTEN, and exons 1 and 2 of KRAS, from 108 primary endometrial tumors. Somatic mutations were confirmed by sequencing matched normal DNAs. The biochemical properties of a subset of novel PIK3CA mutations were determined by exogenously expressing wildtype and mutant constructs in U2OS cells and measuring levels of AKTSer473 phosphorylation.

Results

Somatic PIK3CA mutations were detected in 52.4% of 42 EECs and 33.3% of 66 NEECs. Half (29 of 58) of all nonsynonymous PIK3CA mutations were in exons 1–7 and half were in exons 9 and 20. The exons 1–7 mutations localized to the ABD, ABD-RBD linker and C2 domains of p110α. Within these regions, Arg88, Arg93, Gly106, Lys111, Glu365, and Glu453, were recurrently mutated; Arg88, Arg93 and Lys111 formed mutation hotspots. The p110α-R93W, -G106R, -G106V, -K111E, -delP449-L455, and -E453K mutants led to increased levels of phospho-AKTSer473 compared to wild-type p110α. Overall, 62% of exons 1–7 PIK3CA mutants and 64% of exon 9–20 PIK3CA mutants were activating; 72% of exon 1–7 mutations have not previously been reported in endometrial cancer.

Conclusions

Our study identified a new subgroup of endometrial cancer patients with activating mutations in the amino-terminal domains of p110α; these patients might be appropriate for consideration in clinical trials of targeted therapies directed against the PI3K pathway.

Keywords: Endometrial, cancer, PIK3CA, mutation, spectrum

INTRODUCTION

Endometrial cancer is the eighth leading cause of cancer-related death among American women (1). At presentation, the vast majority of tumors are endometrioid endometrial cancers (EECs), which are estrogen-dependent tumors that may be preceded by endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia, a premalignant outgrowth from hormonally-induced, benign endometrial hyperplasia (2). Most EECs are detected at an early stage when surgery is an effective form of treatment (3). The clinical management of recurrent and advanced disease includes surgery, followed by chemotherapy or radiotherapy alone or in combination (4). However, the prognosis for women with recurrent or advanced stage EECs is relatively poor (5, 6) and alternative therapeutic options are needed.

In contrast to EECs, non-endometrioid endometrial cancers (NEECs) are high-grade, estrogen-independent tumors that arise from the atrophic endometrium in postmenopausal women (7). NEECs are clinically aggressive and have a significantly worse prognosis than EECs even when corrected for tumor stage (5, 6). Current therapeutic strategies to manage NEECs are variable but generally include surgery and adjuvant therapy, even in cases of early-stage disease (4, 8). Although NEECs represent a minority (5–10%) of cases at presentation, they account for a disproportionate number of all endometrial cancer-related deaths (5). Thus, there is a critical need for improved therapeutic options for patients with this tumor subtype.

The PI3Kα-mediated signal transduction pathway is an important therapeutic target for molecularly-defined subsets of cancer (9). PI3Kα is a heterodimeric protein complex comprised of the catalytic p110α subunit and the regulatory p85α subunit, which are encoded by the PIK3CA and PIK3R1 genes respectively (9). Inappropriate activation of PI3Kα-mediated signaling is frequent in human cancers, resulting in increased AKT-dependent or AKT-independent signaling and leading to increased cell proliferation, growth, survival and migration (10, 11). The pathway is antagonized by the activity of the PTEN phosphatase (12–14).

A number of pharmacological agents targeting components of the PI3K signal transduction pathway have been developed (9, 15). These include PI3K inhibitors, AKT inhibitors, and inhibitors of downstream effectors such as mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), a serine-threonine kinase that mediates PI3K-AKT signaling (9). A number of PI3K-pathway inhibitors have already entered clinical trials, including trials to assess efficacy in endometrial cancer patients (16–19).

Common mechanisms of PI3Kα activation in tumorigenesis are the acquisition of somatic gain-of-function mutations within PIK3CA (20), or loss of PTEN activity resulting from mutations or gene deletion (12, 14). Early studies of colorectal, breast, ovarian, and bladder cancers, in which all coding exons of PIK3CA were sequenced, revealed that ~80% of all PIK3CA mutations occurred within exons 9 and 20, which encode the C-terminal helical and kinase domains of p110α (20–22). A much smaller fraction (~ 20%) of PIK3CA mutations in these tumors were within exons 1–7, which encode the N-terminal domains of p110α including the p85/adaptor-binding domain (ABD) and the protein kinase-C homology 2 (C2) domain (23).

PIK3CA exons 9 and 20 mutations are present in 10%–36% of sporadic EECs (24–30) and 15%–21% of NEECs (31, 32). However, most resequencing studies of PIK3CA in sporadic endometrial cancer have been confined to exons 9 and 20 because these two exons encompass >80% of mutations in other tumor types (20). Consequently, the incidence of mutations in other exons of PIK3CA in endometrial tumors has not been rigorously defined. Interestingly however, one study noted a disproportionate number of exon 1 mutations (4 of 6 mutations) in a small series of endometrial cancer cell-lines (33). Another study of primary sporadic EECs observed that 4 of 9 PIK3CA mutations in EECs were in exon 1 (34). Because the frequency of amino terminal p110α mutants relative to carboxy-terminal domain mutants was relatively high in these two studies, we hypothesized that endometrial carcinomas might have a different spectrum of PIK3CA mutations compared with other tumor types. Given the therapeutic importance of altered PI3Kα-mediated signaling, we therefore sought to rigorously define the overall frequency and distribution of somatic PIK3CA mutations in a large series of 108 primary endometrial cancers comprised of EECs and NEECs.

Here we show that in both EECs and NEECs, PIK3CA mutations are as frequent within exons 1–7 as within exons 9–20. Almost all exon 1–7 mutations clustered within three specific regions of p110α, the ABD, the ABD-RBD linker and the C2 domain. Our study revealed three major mutational hotspots at amino acids 88, 93 and 111 within the ABD and its adjacent linker. We extended our study to investigate the biochemical properties of ten previously uncharacterized PIK3CA mutants within exons 1–7. Six of the ten mutations tested encoded gain-of-function p110α mutants that increased levels of phospho-AKT(Ser473), compared to wildtype p110α. Overall, 62% of all mutations in exons 1–7 encoded gain-of-function mutants of p110α. We further show that, like PIK3CA exon 9–20 mutations, mutation in exon 1–7 can co-exist with PTEN and KRAS mutations; 93% of EECs and 38% of NEECs in our study have a mutation in at least one of these three genes. Taken together, our genetic and biochemical data show that endometrial cancers, unlike other tumors, have a high frequency of somatic activating mutations within the ABD, ABD-RBD linker, and C2 domains of p110α. Our findings have potential clinical implications because the mutational status of PIK3CA can guide patient stratification for genotype-directed clinical trials of rationally designed therapies targeting the PI3K pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical material

Snap-frozen primary tumor tissues, corresponding hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained tumor sections, and matched normal tissues, were obtained from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network, which is funded by the National Cancer Institute, or from the Biosample Repository at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia PA. Matched tumor and normal DNAs for six cases were purchased from Oncomatrix. Tumor specimens were collected at surgical resection, prior to treatment. Tumors were selected for endometrioid (n=42), serous (n=46) and clear cell (n=20) histologies. A histological classification was rendered based upon the entire specimen at time of diagnosis. Matched normal tissues were uninvolved reproductive tissue or whole blood. All tissues, and accompanying clinicopathological information, were anonymized and collected with appropriate IRB approval. A pathologist compared the H&E section to the original classification to verify that it was representative histologically, and to delineate regions of tissue comprised of >70% tumor cells for macrodissection.

DNA extraction and identity testing

Genomic DNA was isolated from macrodissected tumor tissues and normal tissues using the PUREGENE kit (Qiagen). To confirm that tumor-normal pairs were derived from the same individual, each DNA sample was typed using the Coriell Identity Mapping kit (Coriell). Genotyping fragments were resolved on an ABI-3730xl DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems) and scored using GeneMapper software.

Mutational analysis by nucleotide sequencing

Primers were designed to PCR amplify all coding exons of PIK3CA and PTEN, and exons 1 and 2 of KRAS (Supplementary Table 1) from tumor DNAs. PIK3CA exons 9–13 primers were designed to avoid amplification of a pseudogene. PCR conditions are available on request. PCR amplicons were resolved by gel electrophoresis, purified by exonuclease I (Epicentre Biotechnologies) and shrimp alkaline phosphatase (USB Corporation) treatment, and bidirectionally sequenced using Big Dye Terminator v.3.1 (Applied Biosystems). Sequencing products were ethanol precipitated and resolved on an ABI-3730xl DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Tumor sequences were aligned to a reference sequence using Sequencher software (Gene Codes Corporation) and visually inspected to identify variant positions. Nucleotide variants absent from dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/) were confirmed by sequencing an independently generated PCR product. Resequencing of matched normal DNA distinguished somatic mutations from novel germline polymorphisms.

Statistical analyses

All comparisons between groups were performed using a 2-tailed Fisher’s Exact test of significance.

Mammalian cell culture

The U2OS human osteosarcoma cell line was maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen), at 37°C, in a humidified atmosphere.

Generation of expression constructs

A baculovirus expression construct containing the full-length, wild-type, PIK3CA cDNA cloned into the pFastBac vector (Invitrogen), was a kind gift from Dr. Yardena Samuels (NHGRI/NIH). This construct was used as a template to generate a series of PIK3CA mutant constructs by site directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mutations created corresponded to the R93Q, R93W, G106R, G106V, K111E, E453A, E453K, E365K, G364R, H1047R, and delP449-455 mutants of p110α. Wild-type and mutant PIK3CA inserts were excised using BamHI and HindIII and subcloned into the FLAG-tagged pCMV-3Tag-1A expression vector (Agilent Technologies). Sanger sequencing was used to confirm the integrity of the cloning sites and the PIK3CA inserts.

Transfections, and western blotting

U2OS cells were transfected with vector, wild-type, or mutant expression constructs using FuGENE-6 transfection reagent (Roche), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Stably transfected cells were selected in the presence of 1000μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen). For western blots, pools of stably selected cells were serum starved in DMEM containing 0.5%FBS for 15hr and lysed in lysis buffer (1% TritonX-100, 150mM NaCL, 50mM Tris-HCL pH 7.4, 1mM EDTA, 1mM Na-orthovanadate, 10mM NaF, 1X protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)). Lysates were centrifuged at 4°C for 10min at 12,000xg to remove insoluble cellular debris and denatured at 95°C in 2X SDS sample buffer (Sigma) for 5min prior to electrophoresis. Denatured proteins (20–40μg) were resolved with SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked in 5% milk/TBST for 30min at room temperature and subsequently blotted with appropriate primary and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies: (FLAG-M2 (Stratagene), β-Actin (Sigma), phospho-AKTSer473, phospho-AKT T308, total AKT (Cell Signaling), Goat anti-mouse HRP (Santa Cruz), and Goat anti-Rabbit HRP (Cell Signaling)). Immunoreactive proteins were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce) and quantitated with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda MD). Normalized band intensities for FLAG-, phospho-AKTSer473, and total AKT were determined by comparison to respective β-Actin band intensities. The average ratio of normalized phospho-AKT to FLAG was calculated for each construct and used to plot the fold change in phospho-AKTSer473 levels for mutants compared to wild-type. For quantitation, western blots were repeated in triplicate.

RESULTS

Somatic mutations in exons 1–7 of PIK3CA are frequent in endometrial cancer

Resequencing exons 1–20 of PIK3CA from a series of 108 primary endometrial tumors revealed somatic PIK3CA mutations in 52.4% (22 of 42) of EECs and 33.3% (22 of 66) of NEECs (Tables 1 and 2), a difference that approached statistical significance (P=0.07). Among NEECs, the frequency of PIK3CA mutations in serous (34.7%, 16 of 46) and clear cell tumors (30%, 6 of 20) was comparable. We observed no significant correlations between PIK3CA mutations and histologic grade or FIGO stage of tumors (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). In both EECs and NEECs PIK3CA mutations were detected at all stages, including stage 1A tumors. Within the EECs, there was no evident association between tumor grade and PIK3CA mutation status.

Table 1.

Somatic PIK3CA mutations in EECs

| Case | Tumor Histology | Tumor Stage | Tumor Grade | PIK3CA Mutation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Nucleotide Change | Predicted Protein Change | Effect on Function† | Previously reported | |||||

| In other cancers | In EEC or NEEC | ||||||||

| T87 | Endometrioid | IB | II/III | Exon 1 | c. G353A | G118D | - | Yes | No |

| T88 | Endometrioid | IB | I | Exon 1 Exon 12 Intron 6 |

c. G263A c. C2001A c. 1252-9 C>A |

R88Q F667L Not determined |

Activating28 - - |

Yes No - |

Yes No - |

| T89 | Endometrioid | IIIA | I | Exon 1 | c. A331G | K111E | Activating¶ | Yes | No |

| T92 | Endometrioid | IB | I | Exon 1 Exon 20 |

c. G278A c. C3074A |

R93Q T1025N |

- - |

Yes Yes |

No No |

| T94 | Endometrioid | IA | I | Exon 1 Exon 5 |

c. G317T c.G1090A |

G106V G364R |

Activating¶ - |

Yes No |

No No |

| T96 | Endometrioid | IA | I | Exon 20 | c. A3140G | H1047R | Activating10,31,32 | Yes | Yes |

| T97 | Endometrioid | IIB | II | Exon 1 Exon 20 |

c. G263A c. A3062G |

R88Q Y1021C |

Activating28 - |

Yes Yes |

Yes Yes |

| T99 | Endometrioid | IA | I | Exon 1 | c. del 325_327 GAA | del E109 | - | Yes | No |

| T101 | Endometrioid | IB | I | Exon 7 Exon 20 |

c. T1258C c. A3140G |

C420R H1047R |

Activating32 Activating10,31,32 |

Yes Yes |

No Yes |

| T102 | Endometrioid | IB | II | Exon 7 | c. del 1343_1363 | del P449-L455 | Activating¶ | No | No |

| T103 | Endometrioid | IB | II | Exon 9 | c. G1624A | E542K | Activating32 | Yes | Yes |

| T115 | Endometrioid | IB | I | Exon 20 Exon 20 |

c.A3118T c.A3140G |

M1040L H1047R |

- Activating10,31,32 |

No Yes |

No Yes |

| T116 | Endometrioid | IA | II | Exon 1 | c. C277G | R93W | Activating¶ | Yes | No |

| T117 | Endometrioid | IB | I | Exon 9 | c. A1633G | E545K | Activating32 | Yes | Yes |

| T118 | Endometrioid | IIA | I | Exon 20 | c. A3140G | H1047R | Activating10,31,32 | Yes | Yes |

| T121 | Endometrioid | IA | I | Exon 9 | c. A1634G | E545G | Activating32 | Yes | Yes |

| T122 | Endometrioid | IC | II | Exon 20 | c. A3140G | H1047R | Activating10,31,32 | Yes | Yes |

| T123 | Endometrioid | IB | I | Exon 9 | c. C1636A | Q546K | Activating32 | Yes | Yes |

| T131 | Endometrioid | IIB | III | Exon 1 | c. C277T | R93W | Activating¶ | Yes | No |

| T132 | Endometrioid | IB | I | Exon 20 | c. G3012T | M1004I | - | Yes | No |

| T133 | Endometrioid | IB | I | Exon 20 | c. G3145C | G1049R | Activating28 | Yes | Yes |

| T134 | Endometrioid | IC | I | Exon 9 Exon 20 |

c. G1633A c. A3127G |

E545K M1043V |

Activating32 Activating32 |

Yes Yes |

Yes Yes |

Indicates the appropriate reference

Mutation shown to be activating in this study (Rudd et al)

Table 2.

Somatic PIK3CA mutations in NEECs

| Case | Tumor Histology | Tumor Stage | PIK3CA Mutation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Nucleotide Change | Predicted Protein Change | Effect on Function† | Previously Reported | ||||

| In other cancers | In EEC or NEEC | |||||||

| OM1323 | Serous | I | Exon 1 Intron 3 Intron 8 |

c.G241A c.562+23 C>A c.1404+10 T>G |

E81K Not determined Not determined |

- - - |

Yes - - |

No - - |

| OM2009 | Serous | I | Exon 9 | c.A1634C | E545A | Activating32 | Yes | Yes |

| T29 | Serous | IB | Exon 9 | c.G1624A | E542K | Activating32 | Yes | Yes |

| T41 | Serous | IIIA | Exon 1 | del c.45-c.67 ins TCCAA | delL15_V22insHPI | - | No | No |

| T49 | Serous | IIB | Exon 9 | c.G1624C | E542Q | - | Yes | Yes |

| T53 | Serous | IB | Exon 9 | c.A1637C | Q546P | Activating32 | Yes | No |

| T68 | Serous | IIA | Exon 1 Exon 1 |

c.G263A c.G323A |

R88Q R108H |

Activating28 Activating28 |

Yes Yes |

Yes Yes |

| T69 | Serous | IIIA | Exon 20 | c.T3132A | N1044K | - | Yes | Yes |

| T71 | Serous | IB | Exon 5 | c.G1093A | E365K | Activating28 | Yes | Yes |

| T74 | Serous | IB | Exon 20 Exon 1 Exon 1 |

c.C3139T c.G278A c.G333T |

H1047Y R93Q K111N |

Activating32 - Activating32 |

Yes Yes Yes |

Yes No No |

| T75 | Serous | IIIA | Exon 20 Exon 20 |

c.A3172T c.A3207G |

I1058F X1069_X1069insW KDN |

- - |

Yes Yes |

Yes Yes Yes |

| T76 | Serous | IA | Exon 7 Intron 7 |

c.G1357A c.1404+3insT |

E453K Not determined |

Activating¶ - |

Yes - |

No - |

| T78 | Serous | IB | Exon 1 | c.A331G | K111E | Activating¶ | Yes | No |

| T79 | Serous | IB | Exon 20 | c.C3075A | T1025A | - | Yes | Yes |

| T80 | Serous | IIIA | Exon 1 | c.G263A | R88Q | Activating28 | Yes | Yes |

| T81 | Serous | IB | Exon 20 | c.A3140G | H1047R | Activating10,31,32 | Yes | Yes |

| T59 | Clear cell | IIIA | Exon 4 Exon 1 |

c.T1031C c.G263A |

V344A R88Q |

- Activating28 |

Yes Yes |

No Yes |

| T61 | Clear cell | IC | Exon 7 | c.A1358C | E453A | - | No | No |

| T63 | Clear cell | IIB | Exon 20 Exon 1 |

c.C3197T c.G278A |

A1066V R93Q |

- - |

Yes Yes |

Yes No |

| T77 | Clear cell | IC | Exon 20 | c.A3140G | H1047R | Activating10,31,32 | Yes | Yes |

| T82 | Clear cell | IVB | Exon 1 | c.G316C | G106R | Activating¶ | No | No |

| T113 | Clear cell | IB | Exon 3 Exon 5 |

c.C665T c.G1093A |

A222V E365K |

- Activating28 |

No Yes |

No Yes |

Indicates the appropriate reference

Mutation shown to be activating in this study (Rudd et al)

Of 62 somatic PIK3CA mutations detected, 58 were exonic and four were intronic (Tables 1 and 2). All exonic mutations were nonsynonymous. The majority (86.2%, 50 of 58) of nonsynonymous mutations were either known gain-of-function mutations (48.3%, 28 of 58), or were of unknown functional significance but previously observed in other cancers (37.9%, 22 of 58) suggesting they are likely to be functionally significant (10, 33, 35–37). A minority (15.5%, 9 of 58) of nonsynonymous mutations was novel. A review of the COSMIC mutation database and published literature revealed that 26 of the 58 (44%) exonic mutations identified in this study have not previously been reported in endometrial cancer (Tables 1 and 2) (33, 35).

Fifty-percent (29 of 58) of all exonic PIK3CA mutations localized within exons 1-7. The remaining 50% of exonic mutations localized within exons 9–20. The high frequency of PIK3CA exon 1–7 mutations was observed for all three histotypes; exon 1–7 mutations constituted 41% (12 of 29) of PIK3CA mutations in endometrioid tumors, 50% (10 of 20) of PIK3CA mutations in serous tumors, and 78% (7 of 9) of PIK3CA mutations in clear cell tumors. The frequency of mutations in exons 1–7 was not significantly different between NEECs (58.6%, 17 of 29) and EECs (41%, 12 of 29), (P=0.29). However, the overall incidence of mutations in exons 1–7 of PIK3CA in this series of 108 endometrial tumors (50%, 29 of 58) was statistically significantly more frequent than others have observed for colorectal cancer (18.5%, 15 of 81; P=0.0001), breast cancer (10.7%, 3 of 28; P=0.0003) or bladder cancer (2.8%, 1 of 36; P=<0.0001) (20–22).

A subset of mutated tumors (29.5%, 13 of 44) had multiple nonsynonymous PIK3CA mutations. Four tumors had co-existing mutations in exons 1–7; six tumors had coexisting mutations in exons 1–7 and exons 9–20; and three tumors had co-existing mutations in exons 9–20. Ten of the 13 tumors had mutations in at least two different domains of p110α.

Mutations in exons 1–7 of PIK3CA

Among the 108 endometrial tumors in this study, 24 (22%) had at least one somatic mutation in exons 1–7 of PIK3CA. Of the 29 individual exon 1–7 mutations, 21 (72%) have not previously been observed in sporadic endometrial cancer (Tables 1 and 2); only the activating R88Q, R108H, and E365K mutations have previously been reported (33–35).

The vast majority (28 of 29, 96.5%) of PIK3CA exon 1–7 mutations in our study localized to the ABD, ADB-RBD linker, and C2 domains of p110α (Figure 1A). Within these domains, six amino acid residues, Arg88 (R88), Arg93 (R93), Gly106 (G106), Lys111 (K111), Glu365 (E365), and Glu453 (E453), were recurrently mutated. Three of these recurrently mutated residues, R88, R93, and K111, formed hotspots that together accounted for 22% (13 of 58) of all exonic mutations in this study.

Figure 1. Distribution of somatic PIK3CA mutations in endometrial cancers and coexistence with PTEN and KRAS mutations.

(A) Localization of PIK3CA mutations in EECs (orange triangles) and NEECs (blue triangles), relative to functional domains of p110α. Amino acid positions are indicated. (B) Patterns of PIK3CA, PTEN, and KRAS utations among 42 EECs (top) and 66 NEECs (bottom). Each column represents an individual tumor. The percentage of mutated tumors is indicated. Cases with a mutation in exons 1–7 of PIK3CA are indicted by a central dot.

Among the 29 individual mutations in exons 1–7, 20 mutations were unique. Five of 20 (25%) unique mutations, namely R88Q, K111N, R108H, E365K, and C420R, are known to encode gain-of-function mutants of p110α (33, 37). The remaining 15 unique mutations have not been functionally characterized. Of these uncharacterized mutations, nine (E81K, R93W, R93Q, G106V, delE109, K111E, G118D, V344A, and E453K), were either recurrent within this study, or were recurrent between this study and other studies (35), suggesting that they might confer a selective advantage in tumorigenesis. The six remaining uncharacterized mutations were novel. Two of the novel mutations (delL15_V22insHPI and G106R) localized to the ABD of p110α, one (A222V) localized to the RBD, and three (G364R, delP449-L445, E453A) localized to the C2 domain. Three novel mutations (delL15_V22insHPI, G106R, delP449-L445, E453A) involved amino acids that undergo a different mutation here or in other studies (31).

Mutations in exons 9–20 of PIK3CA

Fifty-percent (29 of 58) of all nonsynonymous PIK3CA mutations localized within exons 9–20. Of the 29 individual mutations in exons 9–20, 18 (62%) are known to encode activating mutants of p110α. Activating mutations at codons 542, 545, and 1047, known mutational hotspots in p110α, accounted for 25.8% (15 of 58) of all exonic mutations. The frequency of kinase domain mutations (32.7%, 19 of 58) was somewhat greater than the frequency of helical domain mutations (17.2%, 10 of 58), but this did not reach statistical significance (P=0.085). Only five (17%) mutations within exons 9–20 (F667L, T1025N, M1040L, M1004F, and Q546P), have not previously been observed in endometrial tumors (35). Of these four mutations, one (Q546P) is a known gain-of function mutation that is present in seven tumors from other anatomical sites (35, 37).

Patterns of PIK3CA, PTEN, and KRAS mutations in EECs and NEECs

Previous studies of sporadic EECs have shown that mutations in exons 9 and 20 of PIK3CA can coexist with mutations in PTEN and KRAS, two additional genes within the PI3K-mediated signal transduction pathway (25, 26, 29, 38). Because our findings revealed a new subset of endometrial cancer patients with mutations in exons 1–7 of PIK3CA, we extended our study to PTEN and KRAS in order to comprehensively determine the incidence and pattern of PIK3CA-PTEN-KRAS mutations in both EECs and NEECs.

Overall, 93% (39 of 42) of EECs and 38% (25 of 66) of NEECs in this study had a somatic mutation in at least one of these three genes (Figure 1B). Somatic PTEN mutations were present in 78.6% (33 of 42) of EECs and 10.6% (7 of 66) of NEECs (P <0.0001) (Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 4). Somatic KRAS mutations were detected in 42.8% (18 of 42) of EECs and 4.5% (3 of 66) of NEECs (P <0.0001) (Supplementary Table 5). The frequencies of PTEN and KRAS mutations observed in EECs are higher than published data (24, 25), whereas the frequency of such mutations in NEECs is within the range of published data (35).

All permutations of co-existing PIK3CA, PTEN, and KRAS mutations were observed but their relative frequencies differed between EECs and NEECs (Figure 1B). The vast majority (64.2%, 27 of 42) of EECs had mutations within at least two of the three genes. In contrast, the most frequently observed mutation pattern in NEECs was single mutants of PIK3CA, which accounted for 24.2% (16 of 66) of all cases.

In a previous study of endometrial cancers there was a tendency for PIK3CA exons 9 and 20 mutations to be more frequent in PTEN-mutant tumors than in PTEN wildtype tumors (26). Here, we evaluated the pattern of PIK3CA exons 1–20 mutations and PTEN mutations within EECs wherein the incidence of PTEN mutations was 7.4-fold higher than in NEECs. We observed no significant difference in the frequency of PIK3CA mutations among PTEN mutant EECs (51.5%, 17 of 33) and PTEN wild-type EECs (55.5%, 5 of 9) (P=1.0).

PIK3CA and KRAS mutations coexisted in 19% (8 of 42) of EECs and in 1.5% (1 of 66) of NEECs in our study. Given the higher frequency of KRAS mutations in EECs than in NEECs in this study, we evaluated PIK3CA and KRAS mutation patterns in EECs. We observed no significant difference in the frequency of KRAS mutations between PIK3CA wild-type EECs and PIK3CA mutant EECs (50% (10 of 20) versus 36.4% (8 of 22) respectively) (P=0.53). Although there was a tendency for KRAS mutations to be present more often in PTEN mutant EECs (48.5%, 16 of 33) than in PTEN wild-type EECs (22%, 2 of 9 cases), the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.26).

Functional characterization of ABD, ABD-RBD, and C2 domain mutants

Because we observed that PIK3CA exon 1–7 mutations were significantly higher in our series of endometrial tumors than in other tumor types, we sought to determine the functional consequences of a subset of exon 1–7 mutations identified here. Eight of the 15 uncharacterized mutations in these exons were distributed among four recurrently mutated residues (R93, G106, K111, E453) of p110α in our tumor series. We hypothesized that these particular mutations might be functionally significant. We therefore sought to determine the functional significance of the R93W, R93Q, G106R, G106V, K111E, E453A, E453K, delP449-L455 mutants, that together encompass the four recurrently mutated amino acids, as well as the V344A and G364R mutants within the C2 domain.

We examined the ability of each of the p110α mutants to phosphorylate AKT on Serine-473 (Ser473) in stably transfected U2OS (osteosarcoma) cells. We chose U2OS cells because they have low endogenous levels of phospho-AKT, and because they have previously been used to evaluate the activity of other p110α mutants (33). Two known gain- of-function mutants, p110α-E365K (a C2 domain mutant) and p110α H1047R (a kinase domain mutant), were included as positive controls for AKT activation (10, 33).

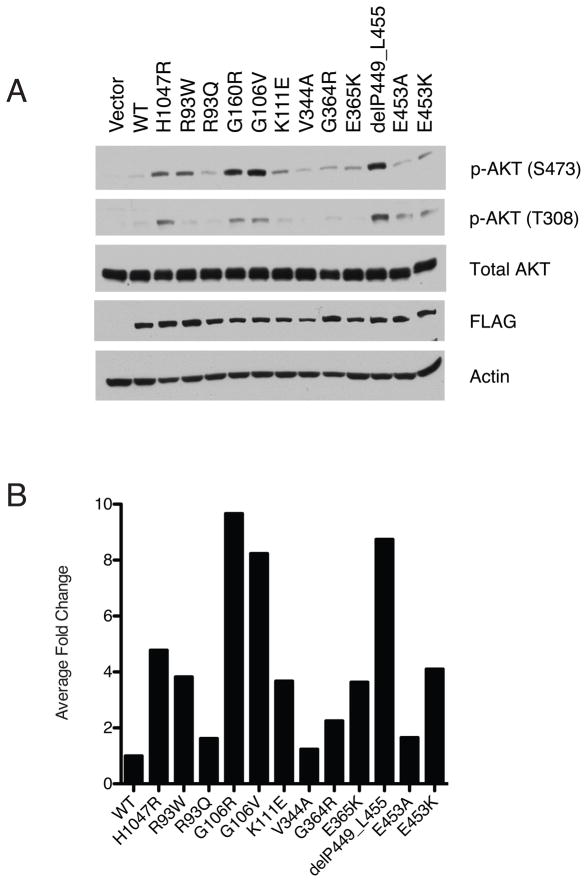

Under low serum conditions, we observed that the exogenous expression of six mutants, p110α-R93W, -G106R, -G106V, -K111E, -delP449-L455, and -E453K, led to increased levels of phospho-AKTSer473 compared to the wild-type p110α (Figure 2A and 2B). These six mutations account for 27% (8 of 29) of PIK3CA exon 1–7 mutations observed in our study. Interestingly, we observed differences in the level of AKT phosphorylation associated with these mutations. Expression of the p110α-G106R, -G106V and -delP449-455 mutants led to higher levels of phospho-AKTSer473 than the p110α-H1047R kinase domain mutant. In contrast, the p110α-R93W, -K111E, and -E453K mutants showed a similar level of phospho-AKTSer473 as the p110α-E365K C2-domain mutant, but lower level phospho-AKTSer473 levels than the p110α-H1047R kinase domain mutant. Phosphorylation on AKTThr308 showed the same pattern as AKTSer473 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A subset of amino terminal mutants of p110a is associated with increased AKT phosphorylation on Ser473.

(A). Total protein from stably transfected, serum starved U2OS cells expressing vector, wild-type FLAG-p110α, or mutant Flag-p110α were analyzed by western blotting. Constructs expressing the known activating mutants, p110α-H1047R and p110α-E365K, served as positive controls for AKT phosphorylation (B) FLAG- p110α and p-AKTSer473 bands were normalized to Actin. The ratio of normalized p-AKTSer473 to normalized FLAG- p110α relative to wild-type p110α is shown.

DISCUSSION

Here we show that endometrial cancers have unique, and tissue-specific, spectrum of somatic PIK3CA mutations. Unlike other tumor types, in which the majority of PIK3CA mutations are within exons 9–20, endometrial cancers display a high frequency of mutations in exons 1–7 of PIK3CA as well as in exons 9–20. Over 60% of the somatic mutations in exons 1–7 were activating. The pattern of PIK3CA mutations that we observed in endometrial cancers is highly statistically significantly different from that of colorectal cancer, breast cancer and bladder cancer, three tumor types for which PIK3CA has been comprehensively resequenced (20–22).

Importantly, our genetic and functional data reveal a new subgroup of endometrial cancer patients who have activating somatic mutations within PIK3CA. Had only exons 9 and 20 been sequenced in this study, we would have missed the 16% of NEECs (11 cases) and 16% of all EECs (7 cases) that have PIK3CA mutations exclusively in exons 1–7; of these cases at least 8 NEECs and 5 EECs have an activating mutation in exons 1–7. An additional 3% of NEECs (2 cases) and 9% of EECs (4 cases) would have incompletely genotyped since they have mutations in both exons 1–7 and exon 9–20.

Exons 1–7 of PIK3CA encode the ABD, RBD, and C2 domains of p110α whereas exons 9–20 encode the helical and kinase domains. Recent structural studies of p110α in complex with p85α have provided critical insights into the distinct properties of the p110α domains (23, 39, 40). The ABD of p110α forms an interface with both the iSH2 domain of p85α and it also has complex interactions with the first alpha helix of the p110α ABD-RBD linker region as well as the first alpha helix of the kinase domain of p110α (40). The C2 domain of p110α mediates binding to the cell membrane, the kinase domain of p110α and the iSH2 domain of p85α. The helical domain acts as a scaffold for the assembly of all other p110α domains. The catalytic activity of p110α resides within the kinase domain.

Here we found that almost all mutations in exons 1–7 localized within the ABD, the ABD-RBD linker region, and the C2 domain of p110α whereas very few mutations localized within the RBD, which binds RAS. This pattern is reminiscent of the distribution of rare exon 1–7 mutations that have been reported in colorectal, breast, and bladder cancers (20). As was previously shown for PIK3CA exons 9–20 mutations (26), we found that PIK3CA exons 1–7 mutations could co-exist with PTEN and KRAS mutants in both EECs and NEECs.

The high frequency, and non-random distribution of amino terminal p110α mutants in EECs and NEECs infers that there is a selective advantage to mutationally disrupting the ABD, the ABD-RBD linker, and the C2 domain of p110α in endometrial carcinomas. Consistent with this idea, 62% of the 29 individual mutations we found in exons 1–7 of PIK3CA, encode gain-of-function mutants of p110α; eight mutations were shown in this study to be gain-of-function mutants that lead to increased levels of phospho-AKTSer473, and ten additional mutations were previously shown by others to be gain-of-function mutations (33, 37).

Approximately one-third of all nonsynonymous mutations present among the 108 endometrial tumors in this study localized within the ABD and proximal ABD-RBD linker region. Strikingly, within these two regions Arg88, Arg 93, and Lys111 residues formed mutational hotspots that accounted for 21% (6 of 29) of all mutations in EECs and 24% (7 of 29) of all mutations in NEECs in our tumor series.

Each of the mutations at Arg88 resulted in an amino acid substitution of arginine for glutamine (R88Q), a known gain-of-function mutant associated with increased AKT activation in vitro (33). Our finding that R88Q is a hotspot in endometrial cancer confirms previous observations by Oda et al., and Dutt et al., in which R88Q constituted 40% (6 of 15) of PIK3CA mutations present among 53 endometrial tumors and cell-lines (33, 34). Arg88 lies on a highly conserved surface of the ABD (40) and it forms a hydrogen bond with Asp746 in the kinase domain of p110α (23). It has therefore been proposed that mutations at Arg88 might disrupt this interaction resulting in an altered kinase domain conformation and increased enzymatic activation of PI3K (23).

Arg93 (R93) formed a second hotspot within the ABD in our tumor series. Two different mutations were found at this reside, R93W and R93Q. Here, we characterized these two mutants functionally and showed that R93W mutation is a gain-of function mutant that leads to increased phosphorylation of AKT on serine 473. In contrast, we observed no evidence for an increase in AKT phosphorylation associated with the R93Q mutant. This was somewhat unexpected because R93Q was mutated in three different endometrial tumors in our study, strongly suggesting that it would have a selective advantage. Interestingly however, each of the three tumors that harbored the R93Q mutant also had at least one other PIK3CA mutation in a different domain of p110α (either T1025N, H1047Y/K111N, or A1066V), whereas tumors with the activating the R93W mutant had no other p110α mutation. Our observation that R93Q always occurs as a “double” or “triple” mutant could be functionally relevant because Zhao and Vogt (41) have shown that two mutations occurring in different domains of p110α can functionally synergize and activate PI3K more potently than either mutation alone. We therefore speculate that the p110α-R93Q mutant might be only weakly activating by itself, below the level of detection in the assays performed here, but that it cooperates with kinase domain mutations to synergistically activate PI3K. Future studies examining the combinatorial effects of the R93Q and its co-occurring mutations will be required to test this hypothesis. However, consistent with the idea that mutations in different domains of p110α can functionally co-operate, the vast majority of endometrial tumors that had two or more PIK3CA mutations in this study had mutations in different domains of p110α.

In addition to R88 and R93 hotspots, another residue in the ABD, at position 106 (G106), was recurrently mutated in endometrial cancer. We found that both mutations at this site (G106R and G106V) were gain-of-function mutants that increased AKT phosphorylation. It is currently unclear how mutations at this residue affect p110α activity since structural studies have not revealed a specific interaction mediated by residue 106 (23).

The third mutation hotspot in the amino terminus of p110α occurred at lysine 111 (K111). One endometrial tumor had a K111N mutation and two additional endometrial tumors had a K111E mutation. Here we showed that the K111E mutant is activating, leading to an increase in AKT phosphorylation compared to wildtype p110α. We observed that the level of phospho-AKT associated with the K111E was lower than for the H1047R mutant. This observation is consistent with the findings of Gymnopoulous et al., that the K111N mutant of p110α is more weakly activating than the H1047R kinase domain mutant (37).

The C2 domain of p110α harbored 13% of all nonsynonymous PIK3CA mutations among the endometrial tumors analyzed in this study. Of the eight individual mutations in the C2 domain, three mutations (E365K in 2 cases, and C420R in one case) were previously shown to be activating (33, 37). Here we tested the functional consequences of the other five C2 domain mutants that had not been previously characterized. We showed that the delP449-L455 and E453K mutants were activating. Both of these mutants increased AKT phosphorylation at levels similar to, or greater than, the strongly activating H1047R kinase domain mutant. Both p110α-Glu453 and the adjacent residue Glu454, form hydrogen bonds with p85α-Glu348 (39). It is therefore likely that the delP449-L455 and E453K mutants disrupt this interaction thus leading to increased catalytic activity. Interestingly we observed that the p110α-delP449-L455 deletion mutant led to much higher levels of phosphorylated AKT than the p110α-E453K point mutant. We speculate that higher level of AKT activation seen with the p110α-delP449-L455 deletion mutant might reflect an additive effect of mutating the p110α-Glu453 and Glu454, both of which form hydrogen bonds with p85α, whereas the E453K point mutant affects only one of these residues. Although we found no convincing biochemical evidence that the p110α-V344R, -G364R, and -E453A C2-domain mutants were activating as single mutants, it remains possible that they might contribute to endometrial tumorigenesis via AKT-independent mechanisms (11), or, in the case of p110α-V344R and p110α-G364R, which co-occur with other PIK3CA mutations, by co-operating with other p110α mutants. Alternatively, these mutants might be bystander mutations that have no selective advantage to tumorigenesis.

In conclusion, our findings revealed a distinct subgroup of endometrial cancer patients with somatic activating mutations in the amino terminus of p110α in their tumors. Molecular alterations in the PI3K pathway can point to subgroups of cancer patients who might benefit clinically from rationally designed therapies that target the PI3K signal transduction pathway. Therefore, our findings have potential clinical implications suggesting the need to comprehensively evaluate all coding exons of PIK3CA to capture the most appropriate endometrial cancer patients for inclusion in genotype-directed trials of therapeutic agents targeting the PI3K pathway.

STATEMENT OF TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

PI3Kα and its downstream signaling molecules are important therapeutic targets for molecularly defined subsets of cancer patients. In endometrial carcinomas, the occurrence of somatic mutations in the helical and kinase domains of p110α, the catalytic subunit of PI3Kα, has been well documented. Here we show that somatic, activating mutations in the ABD, ABD-linker region and C2 domains of p110α are also very frequent in primary endometrial cancers. This finding identifies a novel subgroup of endometrial cancer patients, who might benefit clinically from targeted therapies directed against the PI3K-mediated pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: The Intramural Program of theNational Human Genome Research Institute/NIH (DWB); NIH R01 CA140323 (AKG), U01 CA113916 (AKG), NIH R01-1CA112021-01 (DCS), NCI SPORE in breast cancer at Massachusetts General Hospital (DCS), the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund (AKG), and the Avon Foundation (DCS).

We sincerely thank Drs. Elaine Ostrander and Lawrence Brody, and members of the Bell lab, for careful reading of the manuscript and thoughtful comments; and Ms. JoEllen Weaver for technical assistance.

References

- 1.American SC. Cancer Facts and Figures. American Cancer Society. 2008;1:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hecht JL, Mutter GL. Molecular and pathologic aspects of endometrial carcinogenesis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4783–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu KH. Management of early-stage endometrial cancer. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:137–44. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleming GF. Systemic chemotherapy for uterine carcinoma: metastatic and adjuvant. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2983–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton CA, Cheung MK, Osann K, et al. Uterine papillary serous and clear cell carcinomas predict for poorer survival compared to grade 3 endometrioid corpus cancers. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:642–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creasman WT, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, et al. Carcinoma of the corpus uteri. FIGO 6th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95 (Suppl 1):S105–43. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherman ME. Theories of endometrial carcinogenesis: a multidisciplinary approach. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:295–308. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz PE. The management of serous papillary uterine cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2006;18:494–9. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000239890.36408.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelman JA. Targeting PI3K signalling in cancer: opportunities, challenges and limitations. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:550–62. doi: 10.1038/nrc2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samuels Y, Diaz LA, Jr, Schmidt-Kittler O, et al. Mutant PIK3CA promotes cell growth and invasion of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:561–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasudevan KM, Barbie DA, Davies MA, et al. AKT-independent signaling downstream of oncogenic PIK3CA mutations in human cancer. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–7. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myers MP, Stolarov JP, Eng C, et al. P-TEN, the tumor suppressor from human chromosome 10q23, is a dual-specificity phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9052–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steck PA, Pershouse MA, Jasser SA, et al. Identification of a candidate tumour suppressor gene, MMAC1, at chromosome 10q23.3 that is mutated in multiple advanced cancers. Nat Genet. 1997;15:356–62. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Echeverria C, Sellers WR. Drug discovery approaches targeting the PI3K/Akt pathway in cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:5511–26. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colombo N, McMeekin S, Schwartz P, et al. A phase II trial of the mTOR inhibitor AP23573 as a single agent in advanced endometrial cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2007; 2007 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I; p. 5516. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oza AM, Elit L, Biagi J, et al. Molecular correlates associated with a phase II study of temsirolimus (CCI-779) in patients with metastatic or recurrent endometrial cancer--NCIC IND 160. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(18S):3003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oza AM, Elit L, Provencher D, et al. A phase II study of temsirolimus (CCI-779) in patients with metastatic and/or locally advanced recurrent endometrial cancer previously treated with chemotherapy: NCIC CTG IND 160b. Journal of Clnicial Oncology. 2008:26. abstr 5516. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slomovitz BM, Lu KH, Johnston T, et al. A phase II study of oral mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, RAD001 (everolimus), in patients with recurrent endometrial carcinoma (EC) Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26 abstr 5502. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell IG, Russell SE, Choong DY, et al. Mutation of the PIK3CA gene in ovarian and breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7678–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Platt FM, Hurst CD, Taylor CF, Gregory WM, Harnden P, Knowles MA. Spectrum of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway gene alterations in bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6008–17. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang CH, Mandelker D, Schmidt-Kittler O, et al. The structure of a human p110alpha/p85alpha complex elucidates the effects of oncogenic PI3Kalpha mutations. Science. 2007;318:1744–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1150799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mori N, Kyo S, Sakaguchi J, et al. Concomitant activation of AKT with extracellular-regulated kinase 1/2 occurs independently of PTEN or PIK3CA mutations in endometrial cancer and may be associated with favorable prognosis. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1881–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00630.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catasus L, Gallardo A, Cuatrecasas M, Prat J. PIK3CA mutations in the kinase domain (exon 20) of uterine endometrial adenocarcinomas are associated with adverse prognostic parameters. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:131–9. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oda K, Stokoe D, Taketani Y, McCormick F. High frequency of coexistent mutations of PIK3CA and PTEN genes in endometrial carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10669–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Velasco A, Bussaglia E, Pallares J, et al. PIK3CA gene mutations in endometrial carcinoma: correlation with PTEN and K-RAS alterations. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1465–72. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyake T, Yoshino K, Enomoto T, et al. PIK3CA gene mutations and amplifications in uterine cancers, identified by methods that avoid confounding by PIK3CA pseudogene sequences. Cancer Lett. 2008;261:120–6. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Konstantinova D, Kaneva R, Dimitrov R, et al. Rare Mutations in the PIK3CA Gene Contribute to Aggressive Endometrial Cancer. DNA Cell Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1089/dna.2009.0939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murayama-Hosokawa S, Oda K, Nakagawa S, et al. Genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphism arrays in endometrial carcinomas associate extensive chromosomal instability with poor prognosis and unveil frequent chromosomal imbalances involved in the PI3-kinase pathway. Oncogene. 29:1897–908. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes MP, Douglas W, Ellenson LH. Molecular alterations of EGFR and PIK3CA in uterine serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:370–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Catasus L, Gallardo A, Cuatrecasas M, Prat J. Concomitant PI3K-AKT and p53 alterations in endometrial carcinomas are associated with poor prognosis. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:522–9. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oda K, Okada J, Timmerman L, et al. PIK3CA cooperates with other phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase pathway mutations to effect oncogenic transformation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8127–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dutt A, Salvesen HB, Chen TH, et al. Drug-sensitive FGFR2 mutations in endometrial carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8713–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803379105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bamford S, Dawson E, Forbes S, et al. The COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer) database and website. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:355–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kang S, Bader AG, Vogt PK. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mutations identified in human cancer are oncogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:802–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408864102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gymnopoulos M, Elsliger MA, Vogt PK. Rare cancer-specific mutations in PIK3CA show gain of function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5569–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701005104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shoji K, Oda K, Nakagawa S, et al. The oncogenic mutation in the pleckstrin homology domain of AKT1 in endometrial carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:145–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mandelker D, Gabelli SB, Schmidt-Kittler O, et al. A frequent kinase domain mutation that changes the interaction between PI3Kalpha and the membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16996–7001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908444106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miled N, Yan Y, Hon WC, et al. Mechanism of two classes of cancer mutations in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalytic subunit. Science. 2007;317:239–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1135394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao L, Vogt PK. Helical domain and kinase domain mutations in p110alpha of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase induce gain of function by different mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2652–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712169105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.