1. DISEASE CHARACTERISTICS

1.1 Name of the disease (synonyms)

WAGR syndrome; Wilms tumor, aniridia, genitourinary anomalies and mental retardation syndrome; chromosome 11p13 deletion syndrome.

1.2 OMIM# of the disease

194072.

1.3 Name of the analyzed genes or DNA/chromosome segments

WT1, PAX6.

1.4 OMIM# of the gene(s)

607102 (WT1), 607108 (PAX6).

1.5 Mutational spectrum

Breakpoints differ in individual cases, but the minimum deletion involves both PAX6 and WT1, which are ∼700 kb apart in the distal half of band 11p13.

1.6 Analytical methods

FISH, array CGH, MLPA, high-resolution cytogenetics may identify larger deletions and chromosomal rearrangements. Expert advice should be sought if an etiology is not identified.1, 2

1.7 Analytical validation

Analyze known non-deleted and deleted cases in parallel as controls to show that reagents used for FISH, array CGH and MLPA are working well.

1.8 Estimated frequency of the disease

(Incidence at birth (‘birth prevalence') or population prevalence):

Rare, with only a few hundred cases reported.

1.9 If applicable, prevalence in the ethnic group of the investigated person

Not applicable.

1.10 Diagnostic setting

2. TEST CHARACTERISTICS

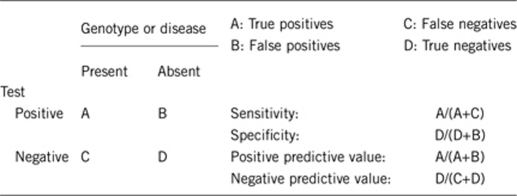

2.1 Analytical sensitivity

(proportion of positive tests if the genotype is present)

Essentially 100% with appropriate FISH probes, MLPA or array CGH. Cytogenetic analysis is less sensitive and, if normal, one of the above methods must be used. Very rarely mosaic sub-microscopic deletions will reduce the analytical sensitivity of MLPA and array CGH but not the use of appropriate FISH probes.

2.2 Analytical specificity

(proportion of negative tests if the genotype is not present)

Essentially 100% with appropriate FISH probes, MLPA or array CGH.

2.3 Clinical sensitivity

(proportion of positive tests if the disease is present)

The clinical sensitivity can be dependent on variable factors such as age or family history. In such cases a general statement should be given, even if a quantification can only be made case by case.

Nearly 100% if sporadic aniridia and Wilms tumor, male genitourinary abnormalities or significant nephropathy is present. If sporadic aniridia alone is present (eg, a newborn female), then 10–30% have WAGR syndrome (data limited by small numbers).3

2.4 Clinical specificity

(proportion of negative tests if the disease is not present)

The clinical specificity can be dependent on variable factors such as age or family history. In such cases a general statement should be given, even if a quantification can only be made case by case. It is worthwhile pointing out that other 11p13 deletions that include WT1 but do not involve PAX6 can occur. Therefore, for patients without aniridia but for whom WT1 deletion is suspected (eg, a patient with Wilms tumor, genitourinary abnormalities and cognitive impairment), genetic testing for 11p13 deletion is recommended.

Essentially 100% if aniridia is not present.

2.5 Positive clinical predictive value

(lifetime risk to develop the disease if the test is positive)

Essentially 100% for aniridia (which is congenital), other features due to WT1 gene deletion are variable. In all, 42.5–77% have been shown to develop Wilms tumor depending on the deletion size. End-stage renal disease develops in 47% of WAGR patients with Wilms tumor by 20 years after diagnosis and also occurs in those without WT. Individuals with XY genotype and intra-abdominal gonads have a high risk of gonadoblastoma and should undergo gonadectomy. XY individuals with descended testes must undergo regular examination for testicular tumors. Individuals with XX genotype have also developed gonadoblastoma and should be screened by imaging.4, 5

2.6 Negative clinical predictive value

(probability not to develop the disease if the test is negative).

Assume an increased risk based on family history for a non-affected person. Allelic and locus heterogeneity may need to be considered.

Index case in that family had been tested:

Essentially 100% if no aniridia.

Index case in that family had not been tested:

Essentially 100% if no aniridia.

3. CLINICAL UTILITY

3.1 (Differential) diagnosis: the tested person is clinically affected

(To be answered if in 1.10 ‘A' was marked)

3.1.1 Can a diagnosis be made other than through a genetic test?

3.1.2 Describe the burden of alternative diagnostic methods to the patient

Not applicable.

3.1.3 How is the cost effectiveness of alternative diagnostic methods to be judged?

Not applicable.

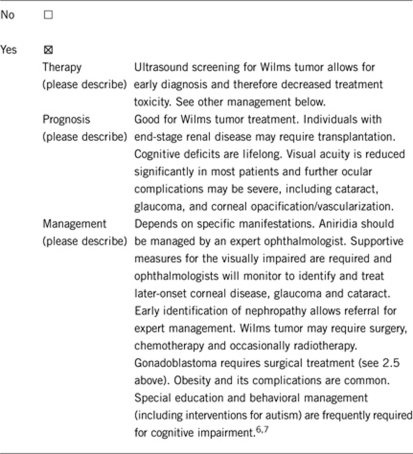

3.1.4 Will disease management be influenced by the result of a genetic test?

3.2 Predictive setting: the tested person is clinically unaffected but carries an increased risk based on family history

(To be answered if in 1.10 ‘B' was marked)

3.2.1 Will the result of a genetic test influence lifestyle and prevention?

If the test result is positive (please describe)

See 3.1.4 for management if test result is positive.

If the test result is negative (please describe)

If test result is negative, eg, a sporadic aniridia patient does not have a WT1 deletion, then monitoring for genitourinary complications, including Wilms tumor, is not warranted.

3.2.2 Which options in view of lifestyle and prevention does a person at risk have if no genetic test has been done (please describe)?

An individual with sporadic aniridia should undergo screening for Wilms tumor by renal ultrasound and urinalysis every 3 months until 6 years and daily caretaker abdominal examination. Renal disease should be screened for by annual blood pressure and urinalysis for proteinuria beginning in early adolescence and through adulthood. There is also risk for gonadoblastoma (see 2.5 above).8

3.3 Genetic risk assessment in the family members of a diseased person

(To be answered if in 1.10 ‘C' was marked)

There are rare instances of familial recurrence of WAGR syndrome due to inherited chromosomal rearrangements or submicroscopic WAGR deletions. Parents and all at-risk relatives (determined by pedigree analysis) should be evaluated for a WAGR-associated chromosomal rearrangement or sub-microscopic deletion.9, 10

3.3.1 Does the result of a genetic test resolve the genetic situation in that family?

Yes.

3.3.2 Can a genetic test in the index patient save genetic or other tests in family members?

Yes.

3.3.3 Does a positive genetic test result in the index patient enable a predictive test in a family member?

Yes, for prenatal diagnosis in the event of a familial chromosomal rearrangement or inherited sub-microscopic deletion.

3.4 Prenatal diagnosis

(To be answered if in 1.10 ‘D' was marked)

An individual with WAGR syndrome has ∼50% chance of passing on the deleted chromosome to the offspring. Prenatal testing for the parental deletion or chromosome rearrangement should be offered.

3.4.1 Does a positive genetic test result in the index patient enable a prenatal diagnosis?

Yes.

4. IF APPLICABLE, FURTHER CONSEQUENCES OF TESTING

Please assume that the result of a genetic test has no immediate medical consequences. Is there any evidence that a genetic test is nevertheless useful for the patient or his/her relatives? (Please describe).

Yes. In addition to the value of understanding the cause and recurrence risk of the disorder, many families have benefited greatly from joining the International WAGR Syndrome Association support group (http://www.wagr.org) and meeting other families. This support group has been instrumental in gathering data about the natural history of WAGR syndrome and stimulating research.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by EuroGentest, an EU-FP6-supported NoE, contract number 512148 (EuroGentest Unit 3: ‘Clinical genetics, community genetics and public health', Workpackage 3.2).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Robinson DO, Howarth RJ, Williamson KA, van Heyningen V, Beal SJ, Crolla JA. Genetic analysis of chromosome 11p13 and the PAX6 gene in a series of 125 cases referred with aniridia. Am J Med Genet. 2008;146A:558–569. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redeker EJ, de Visser AS, Bergen AA, Mannens MM. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) enhances the molecular diagnosis of aniridia and related disorders. Mol Vis. 2008;14:836–840. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grønskov K, Olsen JH, Sand A, et al. Population-based risk estimates of Wilms tumor in sporadic aniridia. A comprehensive mutation screening procedure of PAX6 identifies 80% of mutations in aniridia. Hum Genet. 2001;109:11–18. doi: 10.1007/s004390100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heyningen V, Hoovers JMN, de Kraker J, Crolla JA. Raised risk of Wilms tumour in patients with aniridia and submicroscopic WT1 deletion. Med Genet. 2007;44:787–790. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.051318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow NE, Collins AJ, Ritchey ML, Grigoriev YA, Peterson SM, Green DM. End stage renal disease in patients with Wilms tumor: results from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group and the United States Renal Data System. J Urol. 2005;174:1972–1975. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000176800.00994.3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach BV, Trout KL, Lewis J, Luis CA, Sika M. WAGR syndrome: a clinical review of 54 cases. Pediatrics. 2005;116:984–988. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JC, Liu QR, Jones M, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and obesity in the WAGR syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:918–927. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clericuzio CL, D'Angio GL, Duncan M, Green DM, Knudson AG., Jr Summary and recommendations: first international congress on clinical and molecular genetics of childhood renal tumors. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1993;21:223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Fantes JA, Bickmore WA, Fletcher JM, Ballesta F, Hanson IM, van Heyningen V. Submicroscopic deletions at the WAGR locus, revealed by nonradioactive in situ hybridization. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;51:1286–1294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry I, Hoovers J, Barichard F, et al. Pericentric intrachromosomal insertion responsible for recurrence of del(11)(p13p14) in a family. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1993;7:57–62. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870070110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]