Abstract

It is widely accepted that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is involved in angiogenic functions that are necessary for successful embryonic implantation. We have shown that retinoic acid (RA), which is known to play a necessary role in early events in pregnancy, can combine with transcriptional activators of VEGF (e.g. TPA, TGF-β, IL-1β) to rapidly induce VEGF secretion from human endometrial stromal cells through a translational mechanism of action. We have now determined that this stimulation of VEGF by RA is mediated through an increased production of cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). Results indicated that RA, but not TPA or TGF-β, directly increases ROS production in endometrial stromal cells and that the co-stimulating activity of RA on VEGF secretion can be mimicked by direct addition of H2O2. Importantly, co-treatment of RA with TPA or TGF-β further stimulated ROS production in a fashion that positively correlated with levels of VEGF secretion. The antioxidants N-acetylcysteine and glutathione monoethyl ester inhibited both RA + TPA and RA + TGF-β-stimulated secretion of VEGF, as well as RA-induced ROS production. Treatment of cells with RA resulted in a shift in the glutathione (GSH) redox potential to a more oxidative state, suggesting that the transduction pathway leading to increased VEGF secretion is at least partially mediated through the antioxidant capacity of GSH couples. The specificity of this action on GSH-sensitive signalling pathways is suggested by the determination that RA had no effect on the redox potential of thioredoxin. Together, these findings predict a redox-mediated mechanism for retinoid regulation of localized VEGF secretion in the human endometrium that may be necessary for the successful establishment of pregnancy.

Non-technical summary

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is an angiogenic factor that plays a primary role in blood vessel development in uterine endometrial tissue during embryo implantation and early growth. Previously, we determined that retinoic acid (RA) can act as a co-factor to rapidly induce VEGF secretion from human endometrial stromal cells. We show here that stimulation of VEGF by RA is directly mediated by increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in these cells. These findings predict a ROS-mediated mechanism for RA regulation of localized VEGF secretion in the human endometrium that may be necessary for the successful establishment of pregnancy. The results obtained may provide new targets for therapeutic intervention.

Introduction

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a major angiogenic factor that is critical for maintaining the growth and integrity of the non-pregnant endometrium during the menstrual cycle, as well as playing an essential role in embryo implantation and survival (Ferrara et al.1996; Jauniaux et al. 2006; Maruyama & Yoshimura, 2008). Regulation of VEGF expression at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and translational levels has been extensively studied (Akiri et al. 1998; Huez et al. 1998; Lebovic et al. 1999). Relating to the latter level of control, translational regulation of VEGF has been demonstrated under conditions that involve modulation of the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway and associated alterations in mTOR activity. Examples of this regulatory pathway of VEGF translation have been demonstrated by the actions of integrin α6β4 and c-myc in human breast cancer and B cells, respectively (Chung et al. 2002; Mezquita et al. 2005), and in early responses to ischaemic stress in murine muscle (Bornes et al. 2007). In general, these perturbations lead to phosphorylation of key elements of the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E complex (Hu et al. 2007), or changes in the utilization of internal ribosome entry sites (IRES) located in the 5′ untranslated region of the VEGF mRNA (Bornes et al. 2007). In some cases, activity of PI3K that regulates these processes has been shown to be dependent on the redox state of the cell (Mezquita et al. 2005).

Recent evidence has indicated that moderate levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can act as second messengers in cellular signalling processes. One general example is the interaction of ROS with certain transcription factors to control gene expression and cellular functions (Sauer et al. 2001). Support for this concept comes from the demonstration that a wide range of inflammatory cytokines, hormones and growth factors increase ROS production in selective cell types and that inhibition of free radicals by antioxidants blocks the effects of the agonists. Examples of such agents include tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (Lo et al. 1996), insulin (Goldstein et al. 2005), epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Bae et al. 1997a), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) (Bae et al. 1997b) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) (Garcia-Trevijano et al. 1999). In contrast to the second messenger functions of physiological ROS in normal processes, the generation of supraphysiological levels of ROS can result in toxic cellular responses, reduced viability and mutational changes in DNA (Parola & Robino, 2001; Wittgen & van Kempen, 2007; Liu et al. 2009).

We recently showed that in human endometrial stromal cells, retinoic acid (RA) in the presence of transcriptional activators of VEGF, augments VEGF secretion through a translational mechanism of action (Sidell et al. 2010). Our results suggested that this effect might have a redox-sensitive component as the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) inhibited this stimulation (Sidell et al. 2010). Combined with the knowledge that the production of RA is tightly regulated in the endometrium and is necessary for proper decidualization and implantation to occur (Zheng & Ong, 1998; Zheng et al. 2000), our findings suggested a link between retinoid synthesis and rapid upregulation of VEGF secretion needed during the critical events of early pregnancy establishment. In the present study, we show that the ability of RA to act as a cofactor for translational regulation of VEGF in human endometrial stromal cells is directly mediated by upregulation of ROS production in the cells. The findings indicate that ROS act as second messengers in regulating endometrial angiogenesis and may provide new targets for therapeutic intervention.

Methods

Ethical approval

This project was approved by the Emory Institutional Health and Biosafety Committee. This Committee is charged with reviewing and approving research conducted with, but not limited to, biological toxins, recombinant DNA, human cells, tissues, microorganisms pathogenic to humans, plants, or animals. All participants in this study were trained and certified by this Committee in the appropriate biosafety procedures required.

Cell cultures and chemicals

The HESC (human endometrial stromal cells) cell line was developed and kindly provided to us by Drs Krikun and Lockwood (Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science, Yale University School of Medicine). HESC cells were immortalized from primary endometrial stromal cells by stable transfection of the gene coding an essential catalytic protein subunit of human telomerase reverse transcriptase as previously described (Krikun et al. 2004). All cultures were grown in complete medium: DMEM/F12 (Cellgro) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U ml−1 of penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 of streptomycin, 2 mm l-glutamine and 1 mm Hepes. For treatment, all-trans-RA (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) was diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide to a stock concentration of 50 mm and then diluted to the indicated concentration in complete medium for the experiments. 12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA, Sigma), TGF-β, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), H2O2, monomethoxypolyethylene glycol-catalase (PEG-catalase), unconjugated PEG (as a control for PEG-catalase), and glutathione monoethyl ester (GSH-MEE) were used at the concentrations indicated. Vehicle controls contained the same final solvent concentration.

VEGF ELISA

The secretion of VEGF in the cell culture medium was assessed by ELISA using standardized ELISA kits (Antigenix America Inc.) as described previously (Sidell et al. 2010).

VEGF real-time RT-PCR

For VEGF mRNA quantification, reverse transcription was used to synthesize cDNA from RNA templates using SuperScript II RT (Invitrogen) (Sidell et al. 2010). For real-time PCR, a total of 20 μl reaction mix was prepared using SYBR Green SuperMix (Bio-Rad) and specific primers sets. Primer sequences used were as follows: VEGF, sense (5′-GCA CCC ATG GCA GA-3′), antisense (5′-GCT GCG CTG ATA GA-3′); glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), sense (5′-CCA TGG AGA AGG CT-3′), antisense (5′-CAA AGT TGT CAT GG-3′); glutathione S-transferase P1-1 (GSTP1-1) sense (5′-CAG GGA GGC AAG ACC TTC AT-3′), antisense (5′-GCA GGT TGT AGT CAG CGA A-3′); actin, sense (5′-GGA GCA ATG ATC TT-3′), antisense (5′-CCT TCC TGG GCA TG-3′). The PCR reaction was set for 40 cycles in an Opticon real-time thermocycler (Bio-Rad). The data were analysed after normalization with internal control actin RNA levels.

Kinetic measurements of ROS

ROS generation was measured with the cell-permeable fluorescent probe 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) (Wang & Joseph, 1999). The principle of the test is based upon diffusion of the probe through the cell membrane, whereupon the DCF-DA is hydrolysed to non-fluorescent DCF which is not cell permeable. ROS cause oxidation of DCF to yield a measurable fluorescent product whose intensity is proportional to the amount of ROS formed intracellularly. HESC cells grown to confluence on 96-well plates were incubated in serum-free DMEM containing 100 μm DCF-DA dye. After incubation for 30 min in 5% CO2 at 37°C, the cells were washed and treated with RA, TPA, TGF-β and H2O2 at the indicated concentrations or in combination (RA + TPA, RA + TGF-β) in Krebs–Ringer–Hepes buffer. An increase in fluorescence units was measured by using a microplate reader (SpectraMax M2; Molecular Devices) with excitation at 475 nm and emission at 525 nm. The fluorescence was read immediately after treatment every minute up to 2 h.

Intracellular ROS detected by flow cytometry

In an alternative application, production of ROS in HESC was also quantified using DCF-DA by flow cytometry. In these experiments, HESC were incubated with RA (1 μm), TGF-β (5 ng ml−1), RA + TGF-β, or vehicle control for 6 h. To measure ROS production, cells were again stained with DCF-DA (10 μm for 30 min at 37°C), detached with trypsin/EDTA, washed, re-suspended in PBS, and then immediately analysed using a FACScan flow cytometer to measure the fluorescence intensity (FL1-H) of 10,000 DCF-loaded cells (excitation wavelength, 488 nm; emission wavelength, 515–545 nm). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was obtained using FlowJo 7.6 software.

Analysis of GSH and GSSG

GSH and glutathione disulfide (GSSG) were quantified by HPLC with fluorescence detection. The redox states (Eh) of GSH/GSSG were calculated using the Nernst equation with Eo adjusted for the measured cytosolic pH (Jones, 2002). Cells were washed once with PBS and immediately treated with 325 μl of ice-cold 5% (w/v) perchloric acid solution containing 0.2 m boric acid and 10 μmγ-l-glutamyl-l-glutamate acid and placed on ice. After 5 min, cells were scraped and transferred into microcentrifuge tubes, followed by centrifuging for 5 min at 16,000 g. The supernatants were collected and stored at −80°C until analysis by HPLC. Cellular protein concentrations were measured by bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Sigma) and used to normalize the levels of GSH and GSSG.

Analysis of thioredoxin-1 (Trx1)

Trx1 Eh was performed as previously described (Halvey et al. 2005). In brief, treated cells were collected in a 6 m guanidinium lysis buffer containing 20 mm iodoacetic acid (IAA) and protease inhibitors (Roche). Lysates were incubated for 20 min at 37°C and then were run through a G25 spin column (GE Healthcare) to remove the excess IAA. Oxidized and reduced Trx1 were separated by non-reducing, non-denaturing PAGE on a 15% acrylamide gel. After transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane, a goat anti-human Trx1 polyclonal antibody (American Diagnostica) and an AlexaFluor 680 donkey anti-goat antibody (Invitrogen) were used as primary and secondary antibodies, respectively. Probed membranes were visualized on the infrared Odyssey scanner system (Li-Cor). IAA-labelled Trx1 (reduced) migrates more rapidly through the gel and is represented as the lower band. The oxidized Trx1 is unlabelled and migrates more slowly and is represented as the upper band.

Statistics

All experiments shown were performed a minimum of three times. SPSS software was used for analysis with the data expressed as mean ±s.e.m. Differences between treatment groups were analysed by t test (2-tailed) where P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data shown in some figures (e.g. Western blots, flow cytometry histograms) are from a representative experiment, which was qualitatively replicated in at least three independent experiments.

Results

RA stimulation of VEGF translation involves a redox-sensitive mechanism

Previously, we showed that RA can combine with transcriptional activators of VEGF (TPA, TGF-β, interleukin-1β (IL-1β)) to rapidly induce VEGF secretion from human endometrial stromal cells through a translational mechanism of action (Sidell et al. 2010). These findings were obtained using both primary stromal cultures and HESC cells, confirming that the latter is a physiologically relevant model for studying regulation of VEGF by RA in this cell type. The cofactor stimulatory effect of RA on VEGF protein production is reflected by the fact that VEGF mRNA synthesis in the absence of RA is not necessarily associated with significant VEGF protein secretion (Fig. 1A). Thus, although treatment of HESC with TGF-β or TPA alone significantly increased VEGF mRNA levels, only those cultures co-treated with RA showed a marked increase in VEGF protein secretion. This stimulation of VEGF by RA was greatest in the presence of RA + TPA. Therefore, this treatment combination was initially used to evaluate the inhibitory effects on VEGF secretion by certain antioxidants, followed by confirmatory evidence using TGF-β as a more physiologically relevant transcriptional activator. In this regard, TGF-β is produced in both endometrial and trophoblastic cells (Staun-Ram & Shalev, 2005) and has been shown to play an important role in endometrial-related angiogenesis during the peri-implantation phase of the embryo (Godkin & Doré, 1998). The suggestion that VEGF stimulation by RA may involve a redox-sensitive component was prompted by the observation that NAC inhibited VEGF secretion in RA + TPA-treated cultures (Sidell et al. 2010). Figure 1B shows that H2O2 can mimic the effects of RA on VEGF expression at both the mRNA and protein levels; by itself, H2O2 had only modest effects on mRNA and protein concentrations while co-treatment with TPA dramatically increased VEGF transcription and secretion into the culture supernatant. As such, H2O2+ TPA stimulated VEGF secretion >30-fold over control levels. In contrast, TPA alone nearly maximally induced VEGF transcription, but had no effect on VEGF secretion.

Figure 1. H2O2 mimics the effects of RA on VEGF mRNA and protein secretion when combined with transcriptional activators of VEGF.

In A, HESC were cultured in 12-well culture plates in the absence (Con) or presence of TGF-β (5 ng ml−1) or TPA (50 nm) and cotreated with 1 μm RA or vehicle control as indicated. In B, cells were treated with TPA (50 nm) alone or in combination with 200 μm H2O2 as indicated. VEGF mRNA was assessed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR after treatment for 6 h (circles). VEGF protein in the supernatant (bars) was evaluated by ELISA after 6 h (in experiments with TPA) or overnight treatment (in experiments with TGF-β). VEGF protein levels were only significantly increased in the supernatant of cultures co-treated with either RA or H2O2. By contrast, results showed significant increases in mRNA expression in the presence of TPA or TGF-β alone.

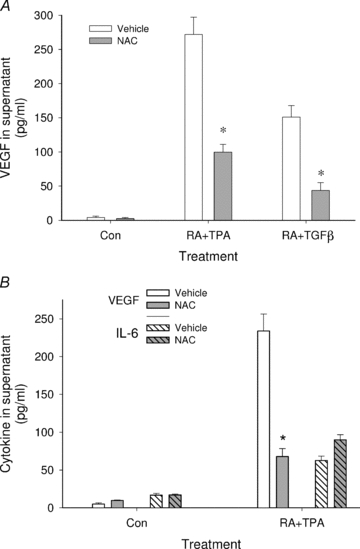

To test whether the inhibitory effect of NAC on VEGF protein secretion was a general phenomenon of RA co-treatment, co-treatment with TGF-β was also evaluated. Figure 2A shows that as with RA + TPA, the addition of NAC to RA + TGF-β suppressed VEGF protein levels by more than 60%. RA co-stimulation of VEGF protein in HESC is specific in that IL-6 and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), cytokines actively secreted by these cells, are unaffected by RA, either alone or in combination with TPA (Sidell et al. 2010). Figure 2B shows that the suppressive effect of NAC on VEGF protein secretion is also specific. Thus, while NAC inhibited VEGF protein levels in culture supernatant of RA + TPA-treated HESC by approximately 70%, no changes in IL-6 protein concentration were seen.

Figure 2. NAC specifically inhibits VEGF secretion induced by RA with VEGF transcriptional activators.

In A, HESC were treated overnight with the compounds as indicated in the absence or presence of the antioxidant NAC (2.5 mm). Concentrations of RA, TPA and TGF-β were as shown in the legend to Fig. 1. Results show that NAC blocked secretion of VEGF by more than 60% when combination treatment involved either TPA or TGF-β. B shows that NAC inhibited RA + TPA stimulation of VEGF but not secretion of IL-6. *Significant decrease from similarly treated cultures without NAC. Con, control.

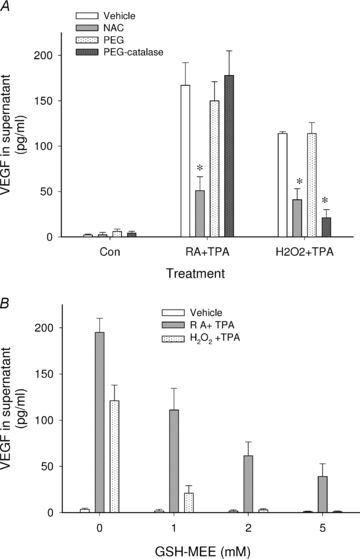

To further examine the potential requirement of ROS production in RA stimulation of VEGF protein, the ability of other antioxidants to modify VEGF secretion from RA + TPA-treated HESC cells was assessed. Figure 3A shows that addition of catalase (in the form of PEG-catalase), the specific scavenger of H2O2, did not inhibit VEGF secretion induced by RA + TPA (middle panel). In contrast, catalase potently suppressed H2O2+ TPA-stimulated VEGF secretion as expected (right panel). Another method for counteracting the effects of ROS production in the cells was achieved by raising intracellular glutathione levels with the addition of GSH-MEE before RA + TPA treatment. In contrast to GSH itself, which is not cell permeable, GSH-MEE diffuses across membranes and GSH accumulates within cells after the ester bond is cleaved (Anderson et al. 1985). As seen in Fig. 3B, GSH-MEE dose-dependently inhibited the stimulation of VEGF protein production. Similar inhibition by GSH-MEE on RA + TGF-β stimulation of VEGF was also observed (data not shown). Neither NAC, PEG-catalase, nor GSH-MEE had appreciable effects on the low basal levels of VEGF secreted from HESC.

Figure 3. Inhibitory effects of different antioxidants on induced VEGF secretion.

In A, HESC were treated overnight with RA + TPA, H2O2+ TPA, or vehicle control (Con) in the absence or presence of NAC (2.5 mm), PEG-catalase (100 U ml−1), or unconjugated PEG (18 μm, as a control for PEG-catalase) as indicated. Results show that NAC inhibited secretion of VEGF induced by both combination treatments while PEG-catalase inhibited secretion induced by H2O2+ TPA but not that induced by RA + TPA. *Significant decrease from similarly treated cultures in the absence of antioxidant. B shows dose-dependent inhibition by GSH-MEE on VEGF secretion induced by both RA + TPA and H2O2+ TPA. Significant inhibition was seen at all GSH-MEE concentrations tested. Concentrations of RA, H2O2 and TPA in all experiments were as shown in the legend to Fig. 1.

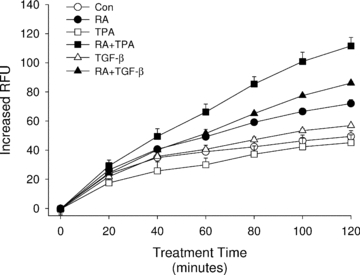

RA directly increases ROS production

Having shown that ROS are required for VEGF secretion induced by RA when co-treated with TPA or TGF-β, we sought to test the hypothesis that this effect is directly mediated through increased production of cellular ROS. This hypothesis is supported by our finding that H2O2 can mimic the effects of RA as a substitute cofactor for VEGF production in HESC. To monitor ROS generation under different treatment conditions, we used DCF as a fluorescent indicator of intracellular ROS concentrations (Feliers et al. 2006). DCF-loaded HESC were cultured in the absence or presence of RA plus/minus TPA or TGF-β, with fluorescence monitored every minute for a total of 120 min. Figure 4 shows that RA caused a gradual increase in cellular fluorescence as compared with vehicle controls. The ROS production rate in RA-treated cells (Vmax= 0.009) was significantly higher (P < 0.001) than controls (Vmax= 0.005). Notably, we did not detect a change of DCF fluorescence in cells treated solely with either TPA (up to 500 nm) or TGF-β (up to 5 ng ml−1). Importantly, the highest ROS production rates were observed in RA + TPA- (Vmax= 0.016) and RA + TGF-β- (Vmax= 0.012) treated cells, suggesting that TPA or TGF-β enhanced the ability of RA to increase ROS production in the cells (Fig. 4). It should be noted that RA concentrations greater than 1 μm were necessary in order to detect consistent changes in DCF fluorescence in contrast with the ability of lower RA concentrations to enhance VEGF secretion (Sidell et al. 2010 and Figs 1–3). Indeed, we have determined that concentrations of RA in the nanomolar range can effectively function as a cofactor to induce VEGF protein production (Sidell et al. 2010). In this regard, it should be noted that endogenous concentrations of RA in secretory endometrium reach levels greater than 2 × 10−8m; high enough to effectively stimulate VEGF secretion as demonstrated by our in vitro studies (Sidell et al. 2010). This lack of concordance between effective RA concentrations in the ROS assay versus its functional effects on VEGF may be due to differences in inherent sensitivities of HESC to chronic, physiological responses (i.e. VEGF secretion) over 6–24 h of treatment versus the acute (<2 h) oxidation of DCF as a measure of ROS production.

Figure 4. Kinetics of RA-induced ROS generation in HESC.

HESC cells preloaded with DCF-DA as described in Methods were treated with RA (10 μm), TPA (500 nm), TGF-β (5 ng ml−1), or combination treatments as indicated in the figure key. Fluorescence was read immediately after adding the treatments and every minute thereafter up to 2 h. Results showed a significant increase in DCF fluorescence starting approximately 1 h after addition of RA or RA + TGF-β and after 45 min in RA + TPA-treated cultures. No other treatments were significantly different from control cultures. Although readings were taken every minute, results are shown in 20 min intervals for clarity of graphical presentation. Symbols without visible error bars indicate that the s.e.m. was less than the value represented by the width of the symbol. RFU, relative fluorescence units.

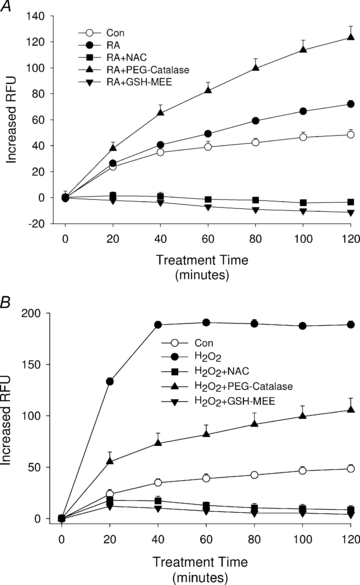

As expected, addition of H2O2 resulted in a potent increase in ROS levels (Fig. 5B). This action by H2O2 was rapid; an increase in ROS was observed within 5 min of treatment with 200 μm H2O2 and reached plateau levels after approximately 40 min. The presence of either NAC or GSH-MEE completely suppressed ROS generation following the addition of RA or H2O2 (Fig. 5A and B, respectively). PEG-catalase was a weaker antioxidant than NAC or GSH-MEE when H2O2-mediated ROS levels were quantified. Surprisingly, in cells co-treated with RA + PEG-catalase, ROS levels were not inhibited but rose above that of RA alone. Taken together, the suppressive effects by the antioxidants on ROS produced by RA or H2O2 positively correlated with the ability of the antioxidants to inhibit RA or H2O2 co-stimulation of VEGF secretion from the cells. In contrast, the enhancement of RA-mediated ROS production by PEG-catalase did not correlate with its effect on VEGF secretion in that no further increase of VEGF was observed (see Discussion following).

Figure 5. Effects of antioxidants on RA-induced ROS production.

In A, HESC cells were preloaded with DCF-DA as in Fig. 4 and then treated with NAC (2.5 mm), PEG-catalase (100 U ml−1), or GSH-MEE (2 mm) for 30 min before treatment with 10 μm RA. While NAC and GSH-MEE were potent inhibitors of ROS production, PEG-catalase unexpectedly showed an increase of DCF fluorescence in comparison to RA alone, indicative of increased ROS levels. B shows control experiments using H2O2 to rapidly increase ROS levels and the potent suppression of ROS by all three antioxidants. As in Fig. 4, results are shown in 20 min intervals for presentation purposes. Symbols without visible error bars indicate that the s.e.m. was less than the value represented by the width of the symbol.

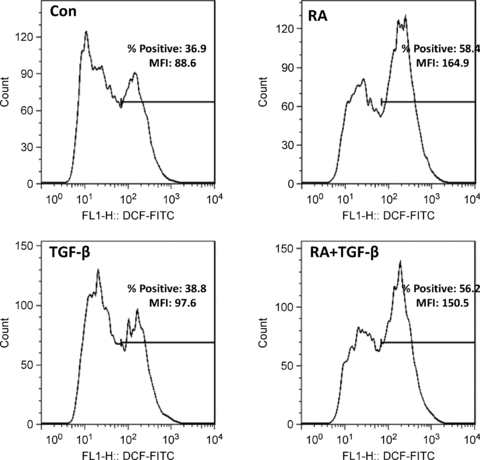

To demonstrate that RA can increase ROS levels at 1 μm concentration and longer treatment times shown to induce VEGF secretion, flow cytometry was utilized to measure the DCF fluorescence of HESC in 6 h cultures. This methodology is more sensitive than the kinetic ROS assay for assessing subtle changes in DCF fluorescence (Hafer et al. 2008) but has the disadvantage of being limited to end-point determinations. Figure 6 shows that when HESC cells were treated with 1 μm RA for 6 h, a period of time that consistently demonstrated co-treatment-induced VEGF protein secretion (Sidell et al. 2010), the mean DCF fluorescence intensity nearly doubled compared with control. As in the kinetic ROS assay, TGF-β by itself showed no effect on DCF signals. In this assay, the DCF fluorescence of RA + TGF-β treatment was not higher than RA by itself, suggesting ROS production may have reached plateau levels by 6 h of stimulation.

Figure 6. Induction of ROS assessed by flow cytometry using a lower RA concentration for a longer treatment time.

HESC were incubated for 6 h in RA (1 μm), TGF-β (5 ng ml−1), RA + TGF-β, or vehicle control (Con) as indicated and analysed for fluorescence in DCF-loaded cells by flow cytometry as described in Methods. Results are expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) and percentage positive cells relative to an isotype control antibody.

Effects of RA on intracellular redox systems

The glutathione (GSH) system regulates many different types of pathways by changing its redox status and protein S-glutathionylating-sensitive targets (Schafer & Buettner, 2001). Within this system, glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) play important roles in maintaining cellular redox balance by catalysing the conjugation of GSH to electrophiles in a wide variety of substances, including peroxides (Coles & Ketterer, 1990). Previous work by Xia et al. (1993) showed that in a variety of human cells, expression of GSTP1-1 is suppressed by RA as a result of decreased transcription. Prompted by these findings, we utilized quantitative real-time RT-PCR to test whether RA could affect the glutathione redox potential by suppressing GSTP1-1 expression. Our results showed no differences in GSTP1-1 mRNA levels in HESC treated with vehicle control, TPA, RA, or RA + TPA under culture conditions (as described in legend to Fig. 1) that showed marked induction of VEGF secretion in our functional studies (data not shown).

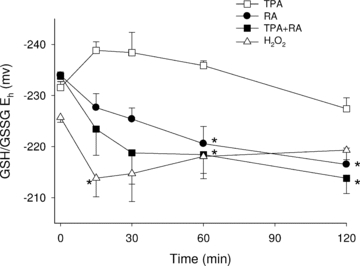

To further evaluate the effects of our treatments on the GSH system, intracellular GSH and its oxidized form, glutathione disulfide (GSSG), were measured. In HESC, concentrations of GSH and GSSG at time 0 min were 3.5 ± 0.4 mm and 165 ± 14 μm, respectively. Calculation of the GSH/GSSG redox potential (Eh) using these calculations yielded a mean Eh of −230 ± 4 mV. Treatment with TPA over 120 min did not significantly increase GSH/GSSG Eh (Fig. 7). RA exposure induced a significant oxidation of GSH; after 120 min it measured −216.5 ± 2.1 mV and constituted an increase of +17 mV (P < 0.01). Combined treatments of RA and TPA also demonstrated a significant oxidation of GSH/GSSG Eh, increasing to −213.8 ± 3.0 mV (an increase of +20 mV from untreated, P < 0.003). H2O2, treatment stimulated a rapid oxidation of GSH Eh (+14 mV), and then a gradual return to basal redox states over time, demonstrating different kinetics of GSH oxidation compared to RA treatments. Regardless, these levels of oxidation are believed to be physiologically relevant as changes of this degree are capable of the activation or deactivation of many different redox-sensitive systems (e.g. phosphatases, transcription factors) (Kretz-Remy & Arrigo, 2010).

Figure 7. RA-induced changes of the GSH/GSSG redox state.

HESC were treated with RA (10 μm), TPA (500 nm), RA + TPA or H2O2 (200 μm, as a positive control) for up to 2 h. GSH and GSSG concentrations were measured via HPLC and these values were used to calculate the cellular GSH/GSSG redox potential (Eh) through the Nernst equation (Jones, 2002). Results show that RA and RA + TPA, but not TPA alone, cause a significant oxidation (becoming more positive) of the GSH/GSSG Eh. Data shown are the result of at least 3 independently performed experiments for each treatment condition and are expressed as means (±s.e.m.). *Significant increase from initial (time zero) Eh values.

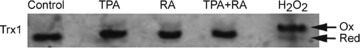

Cytoplasmic thioredoxin (Trx1) is another redox couple protein that plays an important role in intracellular signalling, acts as a growth factor, an antioxidant, a cofactor that provides reducing equivalents, and a transcriptional regulator (Watson et al. 2004). The Trx1 redox state is independently regulated from the GSH/GSSG Eh, suggesting that there are elements and pathways that are primarily regulated by Trx1 and others by GSH (Go et al. 2006). To further understand the nature of RA-mediated ROS signalling, we evaluated the effects of RA on the Trx1 Eh as well (Fig. 8). Although H2O2 dramatically oxidized Trx1, its Eh remained unchanged after 120 min of exposure with TPA, RA or TPA + RA, suggesting that mediation of the RA signal does not occur via the Trx1 system.

Figure 8. Thioredoxin-1 (Trx1) redox state in HESC after RA, TPA and RA + TPA treatments.

HESC were treated for 2 h with RA (10 μm), TPA (500 nm) or RA + TPA or for 10 min with H2O2 (200 μm, as a positive control). Separation was based upon carboxymethylation of reduced Trx1 and subsequent separation on a non-reducing, non-denaturing gel (separation based on differences in charge) (see Methods). The upper band represents oxidized (non-carboxymethylated) Trx1 and the lower band represents reduced Trx1. With all treatments (except in the positive control), Trx1 redox state did not change, suggesting that the effects of RA may be specific to the GSH system and not involve the Trx1 system.

Discussion

Rapid biosynthesis of VEGF at the site of embryonic implantation is postulated to be a critical event in the early establishment of pregnancy (Sidell et al. 2010). Regulation of VEGF synthesis via production of ROS has been described at both the transcriptional and translational levels of control (Akiri et al. 1998; Huez et al. 1998; Lebovic et al. 1999). Our results demonstrate that in human endometrial stromal cells, translational upregulation of VEGF by RA, acting as a cofactor with VEGF transcriptional activators, is directly mediated by increased ROS production. This conclusion is prompted by the following evidence: (1) H2O2 mimicked the effects of RA on VEGF expression at both the mRNA and protein levels; (2) the RA-induced effects on VEGF secretion are inhibited by NAC and GSH-MEE, compounds that readily metabolize intracellular ROS; (3) RA was shown to directly increase ROS production in HESC and this production was blocked by NAC and GSH-MEE. PEG-catalase inhibited H2O2-induced VEGF but did not show inhibition of VEGF stimulated by RA as was seen with NAC and GSH-MEE. We interpret this finding to reflect the distinct localization of PEG-catalase in the HESC cell membrane (Nemoto et al. 2007), whereas we postulate that RA generates ROS within intracellular compartments.

Previous work has suggested that the localization of specific antioxidants plays a role in the mechanism by which redox signalling is regulated (Halvey et al. 2005; Mesquita et al. 2010). For example, epidermal growth factor (EGF) binding to its cell surface receptor induces intracellular H2O2 production, a signal that is necessary to induce proliferation (Mesquita et al. 2010). However, analysis of redox couples in EGF-treated keratinocytes showed that only cytosolic couples were affected, while mitochondrial and nuclear pools remained unchanged (Halvey et al. 2005). Thus, it appears that regional localization of ROS signals is critical for regulating the specificity of a certain signal (Watson et al. 2004). Interestingly, our data indicated that RA + PEG-catalase showed even higher levels of ROS production than RA alone. The reasons for this are unknown. However, PEG alone as well as PEG-conjugated enzymes such as PEG-catalase can increase plasma membrane fluidity (Beckman et al. 1988), and in endometrial cells a positive correlation has been observed between membrane fluidity and superoxide anion radical generation (Laloraya, 1990). Further support for this suggestion is that both PEG and PEG-catalase by themselves increased ROS levels in HESC (data not shown). In contrast, these compounds did not induce VEGF secretion, either alone, or in combination with other agents supporting the hypothesis that specifically compartmentalized ROS production may be critical for signals involved in VEGF translation.

The biochemical mechanism by which RA increases ROS is presently unknown. Our use of the H2O2-sensitive fluorescent probe DCF for assessing ROS levels indicates the generation of this peroxide as a result of retinoid treatment. This observation is important since of all ROS-producing cellular reactions, H2O2 is believed to be the primary ROS that acts as a second messenger in most redox-sensitive signalling processes (Sauer et al. 2001). Previous studies have indicated a variety of mechanisms by which RA can induce oxidative stress in cells including enhanced formation of hydroxyl anions (da Fronta et al. 2006), increased superoxide production (Kikuchi et al. 2010), and activation of the NADPH oxidase system (Konopka et al. 2008). Enhancement of these systems could result in increased lipid peroxidation as well as the direct or indirect generation of H2O2 (Kubow et al. 2000; da Fronta et al. 2006).

Our results indicate that the mechanism by which RA increases ROS is acting specifically through GSH-sensitive signalling pathways. Thus, RA treatment of HESC resulted in an increase of the GSH/GSSG Eh and reflected a shift to a more oxidative intracellular environment. These data support previous studies showing the ability of RA to decrease levels of GSH in chick chondrocytes (Teixeira et al. 1996). Effects on the GSH redox system by RA through transcriptional suppression of GSTP1-1 in human bladder and breast carcinoma cells, and in a human keratinocyte cell line have also been reported (Xia et al. 1996). However, we did not see this effect in HESC, nor did RA oxidize Trx1. These findings demonstrate that VEGF secretion as mediated by RA-induced oxidation may in part rely on redox-sensitive elements that are regulated by GSH redox states but are comparatively independent of GSTP1-1 or Trx1 oxidation.

The inability of the VEGF transcriptional activators as single agent treatments to upregulate VEGF protein production in endometrial stromal cells appears to be relatively unique; TPA, TGF-β, or IL-1β as single agents have each been reported to stimulate VEGF protein secretion in a variety of cell types including breast cancer, keratinocytes, oviductal cells and macrophages (Frank et al. 1995; Nasu et al. 2006; Ono, 2008; Kim et al. 2009). The seemingly unique quality of VEGF regulation in endometrial stromal cells is also emphasized by reports showing that increased ROS levels per se (e.g. treatment with H2O2) can stimulate VEGF protein secretion in some cells and tissues (Fay et al. 2006; Feliers et al. 2006; Carrière et al. 2009). This characteristic is clearly not evident in HESC since RA and H2O2 were not by themselves effective stimulators of VEGF production.

Downstream of ROS production, various redox-sensitive mechanisms that involve translational regulation of VEGF have been described. These include increased translation of VEGF mRNA transcripts via two internal ribosomal entry sites (IRES) located in the prominent VEGF 5′-untranslated region (Akiri et al. 1998; Huez et al. 1998). A precedent demonstrating the ability of RA to induce IRES-mediated translation has been shown in the case of mouse TrkB mRNA, which, like VEGF, contains a complex secondary structure in its untranslated region with two independent IRES (Timmerman et al. 2007). Using a dicistronic reporter system (Bert et al. 2006), we were unable to validate RA stimulation of IRES-mediated translation of VEGF in HESC (data not shown). Another ROS-sensitive mechanism that has been described for regulating VEGF translation involves redox-sensitive kinase activity (Clerkin et al. 2008; Zheng et al. 2010). For example, c-myc stimulation of VEGF mRNA translation is mediated by PI3K activation, which is dependent on ROS production (Mezquita et al. 2005; Clerkin et al. 2008). Finally, the VEGF chaperone protein oxygen-regulated protein 150, which is up-regulated by inducers of ROS and endoplasmic reticulum stress (e.g. tunicamycin) (Dukes et al. 2008), increases the translation and extracellular release of VEGF (Ozawa et al. 2001; Taylor et al. 2009).

We have speculated that one role played by retinoids in the endometrium is to spatiotemporally regulate VEGF secretion during the peri-implantation phase of the menstrual cycle and in early pregnancy to sustain embryonic development (Sidell et al. 2010). In addition to the ability of RA to quickly stimulate VEGF secretion from endometrial stromal cells, this hypothesis is supported by a number of other observations: (i) endometrial stromal cells and placental cytotrophoblasts can synthesize RA from retinol during early decidualization and cytotrophoblast invasion (Zheng et al. 2000; Ulven et al. 2000; Deng et al. 2003); (ii) RA production by endometrial stromal cells is increased during in vitro decidualization (Sidell et al. 2010); (iii) RA accumulates in human secretory endometrium to functionally relevant levels (Sidell et al. 2010); and (iv) retinoid receptors are preferentially expressed at the implantation site in humans (Tarrade et al. 2000). We now show that the effects of RA on VEGF production are, at least partly, mediated through a tightly regulated increase in ROS production in endometrial stromal cells. Other evidence for this mechanism of RA regulation of VEGF in early angiogenic events of pregnancy comes from in vivo studies demonstrating reduced fecundity of rats treated with NAC (Harada et al. 2003). Findings of this work included a significant increase in post-implantation pregnancy loss in NAC-treated rats whose blood levels can be calculated to approximate the NAC concentrations used in our in vitro assays to block RA stimulation of VEGF secretion (250 mm).

Since ROS are important regulators of various signal transduction cascades, including NF-κB (Gloire et al. 2006), PI3K/AKT (Barthel & Klotz, 2005) and MAP kinase pathways (McCubrey et al. 2006), RA is likely to modulate a variety of genes during critical stages of embryonic implantation and early growth, including ROS-sensitive gene networks in human endometrial stromal cells (Leitao et al. 2010). In conclusion, although the molecular mechanisms that regulate ROS levels during the reproductive cycle have yet to be fully determined, our findings predict that localized production of RA in the pregnant uterus may be a principal factor in this process. This activity suggests a novel mechanism through which retinoid metabolism plays a fundamental role in reproductive biology.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Kelly Shen for her outstanding technical support. This work was supported by The Eunice Kennedy Schriver NICHD/NIH through Grants HD55379 and HD55787, as part of the Specialized Cooperative Center Program.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DCF-DA

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- EGF

endothelial growth factor

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

glutathione disulfide

- GSH-MEE

glutathione monoethyl ester

- GSTP1-1

glutathione S-transferase P1-1

- HESC

immortalized human endometrial stromal cell

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- PEG-catalase

monomethoxypolyethylene glycol-catalase

- RA

retinoic acid

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- TPA

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate

- Trx1

cytoplasmic thioredoxin-1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Author contributions

Experiments were performed in the laboratories of N.S. All the experiments were performed by J.W. and L.H. except GSH HPLC and Trx1 Western blots, which were conducted by J.M.H. The experiments were designed by J.W., N.S., J.M.H. and R.N.T. who also wrote and revised the paper. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

References

- Akiri G, Nahari D, Finkelstein Y, Le S-Y, Elroy-Stein O, Levi B-Z. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression is mediated by internal initiation of translation and alternative initiation of transcription. Oncogene. 1998;17:227–236. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ME, Powrie F, Puri RN, Meister A. Glutathione monoethyl ester: preparation, uptake by tissues, and conversion to glutathione. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;239:538–548. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90723-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae YS, Kang SW, Seo MS, Baines IC, Tekle E, Chock PB, Rhee SG. Epidermal growth factor (EGF)-induced generation of hydrogen peroxide. Role in EGF receptor-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1997a;272:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae YS, Sung JY, Kim OS, Kim YJ, Hur KC, Kazlauskas A, Rhee SG. Platelet-derived growth factor-induced H2O2 production requires the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997b;275:10527–10531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthel A, Klotz LO. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling in the cellular response to oxidative stress. Biol Chem. 2005;386:207–216. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman JS, Minor RL, Jr, White CW, Repine JE, Rosen GM, Freeman BA. Superoxide dismutase and catalase conjugated to polyethylene glycol increases endothelial enzyme activity and oxidant resistance. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:6884–6892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bert AG, Grépin R, Vadas MA, Goodall GJ. Assessing IRES activity in the HIF-1α and other cellular 5′ UTRs. RNA. 2006;12:1074–1083. doi: 10.1261/rna.2320506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornes S, Prado-Lourenco L, Bastide A, Zanibellato C, Iacovoni JS, Lacazette E, Prats AC, Touriol C, Prats H. Translational induction of VEGF internal ribosome entry site elements during the early response to ischemic stress. Circ Res. 2007;100:305–308. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258873.08041.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrière A, Ebrahimian TG, Dehez S, Augé N, Joffre C, André M, Arnal S, Duriez M, Barreau C, Arnaud E, Fernandez Y, Planat-Benard V, Lévy B, Pénicaud L, Silvestre JS, Casteilla L. Preconditioning by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species improves the proangiogenic potential of adipose-derived cells-based therapy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1093–1099. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.188318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung J, Bachelder RE, Lipscomb EA, Shaw LM, Mercurio AM. Integrin (α6β4) regulation of eIF-4E activity and VEGF translation: a survival mechanism for carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:165–174. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerkin JS, Naughton R, Quiney C, Cotter TG. Mechanisms of ROS modulated cell survival during carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2008;266:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles B, Ketterer B. The role of glutathione and glutathione transferases in chemical carcinogenesis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1990;25:47–70. doi: 10.3109/10409239009090605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Fronta MC, Jr, da Silva EG, Behr GA, de Oliveira MR, Dal-Pizzol F, Klamt F, Moreira JC. All-trans retinoic acid induces free radical generation and modulates antioxidant enzyme activities in rat Sertoli cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;285:173–179. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-9077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L, Shipley GL, Loose-Mitchell DS, Stancel GM, Broaddus R, Pickar JH, Davies PJ. Coordinate regulation of the production and signaling of retinoic acid by estrogen in the human endometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2157–2163. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukes AA, Van Laar VS, Cascio M, Hastings TG. Changes in endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins and aldolase A in cells exposed to dopamine. J Neurochem. 2008;106:333–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05392.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay J, Varoga D, Wruck CJ, Kurz B, Goldring MB, Pufe T. Reactive oxygen species induce expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in chondrocytes and human articular cartilage explants. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R189. doi: 10.1186/ar2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliers D, Gorin Y, Ghosh-Choudhury G, Abboud HE, Kasinath BS. Angiotensin II stimulation of VEGF mRNA translation requires production of reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F927–F936. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00331.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N, Carver-Moore K, Chen H, Dowd M, Lu L, O'Shea KS, Powell-Braxton L, Hillan KJ, Moore MW. Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature. 1996;380:439–442. doi: 10.1038/380439a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S, Hübner G, Breier G, Longaker MT, Greenhalgh DG, Werner S. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in cultured keratinocytes. Implications for normal and impaired wound healing. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12607–12613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Trevijano ER, Iraburu MJ, Fontana L, Dominguez-Rosales JA, Auster A, Covarrubias-Pinedo A, Rojkind M. Transforming growth factor β1 induces the expression of α1(i) procollagen mRNA by a hydrogen peroxide-C/EBPβ-dependent mechanism in rat hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 1999;29:960–970. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloire G, Legrand-Poels S, Piette J. NF-κB activation by reactive oxygen species: Fifteen years later. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:1493–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go YM, Ziegler TR, Johnson JM, Gu L, Hansen JM, Jones DP. Selective protection of nuclear thioredoxin-1 and glutathione redox systems against oxidation during glucose and glutamine deficiency in human colonic epithelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;42:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godkin JD, Doré JJ. Transforming growth factor β and the endometrium. Rev Reprod. 1998;3:1–6. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0030001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BJ, Mahadev K, Wu X, Zhu L, Motoshima H. Role of insulin-induced reactive oxygen species in the insulin signaling pathway. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1021–1031. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafer K, Iwamoto KS, Schiestl RH. Refinement of the dichlorofluorescein assay for flow cytometric measurement of reactive oxygen species in irradiated and bystander cell populations. Radiat Res. 2008;169:460–468. doi: 10.1667/RR1212.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvey PJ, Watson WH, Hansen JM, Go YM, Samali A, Jones DP. Compartmental oxidation of thiol-disulphide redox couples during epidermal growth factor signalling. Biochem J. 2005;386:215–219. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada M, Kishimoto K, Furuhashi T, Naito K, Nakashima Y, Kawaguchi Y, Hiraoka I. Infertility observed in reproductive toxicity study of N-acetyl-l-cysteine in rats. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:242–247. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.013862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Straub J, Xiao D, Singh SV, Yang HS, Sonenberg N, Vatsyayan J. Phenethyl isothiocyanate, a cancer chemopreventive constituent of cruciferous vegetables, inhibits cap-dependent translation by regulating the level and phosphorylation of 4E-BP1. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3569–3573. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huez I, Creancier L, Audigier S, Gensac MC, Prats AC, Prats H. Two independent internal ribosome entry sites are involved in translation initiation of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6178–6190. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauniaux E, Poston L, Burton GJ. Placental-related diseases of pregnancy: Involvement of oxidative stress and implications in human evolution. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12:747–755. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DP. Redox potential of GSH/GSSG couple: assay and biological significance. Methods Enzymol. 2002;348:93–112. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)48630-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi H, Kuribayashi F, Kiwaki N, Nakayama T. Curcumin dramatically enhances retinoic acid-induced superoxide generating activity via accumulation of p47-phox and p67-phox proteins in U937 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2010;395:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Choi JH, Lim HI, Lee SK, Kim WW, Kim JS, Kim JH, Choe JH, Yang JH, Nam SJ, Lee JE. Silibinin prevents TPA-induced MMP-9 expression and VEGF secretion by inactivation of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopka R, Kubala L, Lojek A, Pachernik J. Alternation of retinoic acid induced neural differentiation of P19 embryonal carcinoma cells by reduction of reactive oxygen species intracellular production. Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2008;29:770–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretz-Remy C, Arrigo AP. Gene expression and thiol redox state. Methods Enzymol. 2010;348:200–215. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)48639-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krikun G, Mor G, Alvero A, Guller S, Schatz F, Sapi E, Rahman M, Caze R, Qumsiyeh M, Lockwood CJ. A novel immortalized human endometrial stromal cell line with normal progestational response. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2291–2296. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubow S, Woodward TL, Turner JD, Nicodemo A, Long E, Zhao X. Lipid peroxidation is associated with the inhibitory action of all-trans-retinoic acid on mammary cell transformation. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:843–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laloraya M. Fluidity of the phospholipid bilayer of the endometrium at the time of implantation of the blastocyst – a spin label study. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;167:561–567. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)92061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebovic DI, Mueller MD, Taylor RN. Vascular endothelial growth factor in reproductive biology. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1999;11:255–260. doi: 10.1097/00001703-199906000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitao B, Jones MC, Fusi L, Higham J, Lee Y, Takano M, Goto T, Christian M, Lam EW, Brosens JJ. Silencing of the JNK pathway maintains progesterone receptor activity in decidualizing human endometrial stromal cells exposed to oxidative stress signals. FASEB J. 2010;24:1541–1551. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-149153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Qu W, Kadiiska MB. Role of oxidative stress in cadmium toxicity and carcinogenesis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;238:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo YY, Wong JM, Cruz TF. Reactive oxygen species mediate cytokine activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15703–15707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubrey JA, Lahair MM, Franklin RA. Reactive oxygen species-induced activation of the MAP kinase signaling pathways. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1775–1789. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T, Yoshimura Y. Molecular and Cellular mechanisms for differentiation and regeneration of the uterine endometrium. Endocr J. 2008;55:795–810. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k08e-067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita FS, Dyer SN, Heinrich DA, Bulun SE, Marsh EE, Nowak RA. Reactive oxygen species mediate mitogenic growth factor signaling pathways in human leiomyoma smooth muscle cells. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:341–351. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.075887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezquita P, Parghi SS, Brandvold KA, Ruddell A. Myc regulates VEGF production in B cells by stimulating initiation of VEGF mRNA translation. Oncogene. 2005;24:889–901. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasu K, Itoh H, Yuge A, Kawano Y, Yoshimatsu J, Narahara H. Interleukin-1β regulates vascular endothelial growth factor and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 secretion by human oviductal epithelial cells and stromal fibroblasts. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22:495–500. doi: 10.1080/08916930600929487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto T, Kawakami S, Yamashita F, Hashida M. Efficient protection by cationized catalase against H2O2 injury in primary cultured alveolar epithelial cells. J Control Release. 2007;121:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M. Molecular links between tumor angiogenesis and inflammation: inflammatory stimuli of macrophages and cancer cells as targets for therapeutic strategy. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1501–1506. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa K, Tsukamoto Y, Hori O, Kitao Y, Yanagi H, Stern DM, Ogawa S. Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by oxygen-regulated protein 150, an inducible endoplasmic reticulum chaperone. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4206–4213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parola M, Robino G. Oxidative stress-related molecules and liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2001;35:297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer H, Wartenberg M, Hescheler J. Reactive oxygen species as intracellular messengers during cell growth and differentiation. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2001;11:173–186. doi: 10.1159/000047804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer FQ, Buettner GR. Redox environment of the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:1191–1212. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidell N, Feng Y, Hao L, Wu J, Yu J, Kane MA, Napoli JL, Taylor RN. Retinoic acid is a cofactor for translational regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in human endometrial stromal cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:148–160. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staun-Ram E, Shalev E. Human trophoblast function during the implantation process. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2005;3:56–68. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-3-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrade A, Rochette-Egly C, Guibourdenche J, Evain-Brion D. The expression of nuclear retinoid receptors in human implantation. Placenta. 2000;21:703–710. doi: 10.1053/plac.2000.0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RN, Yu J, Torres PB, Schickedanz AC, Park JK, Mueller MD, Sidell N. Mechanistic and therapeutic implications of angiogenesis in endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:140–146. doi: 10.1177/1933719108324893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira CC, Shapiro IM, Hatori M, Rajpurohit R, Koch C. Retinoic acid modulation of glutathione and cysteine metabolism in chondrocytes. Biochem J. 1996;314:21–26. doi: 10.1042/bj3140021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman SL, Pfingsten JS, Kieft JS, Krushel LA. The 5′ leader of the mRNA encoding the mouse neurotrophin receptor TrkB contains two internal ribosomal entry sites that are differentially regulated. PLoS One. 2007;3:e3242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulven SM, Gundersen TE, Weedon MS, Landaas VO, Sakhi AK, Fromm SH, Geronimo BA, Moskaug JO, Blomhoff R. Identification of endogenous retinoids, enzymes, binding proteins, and receptors during early postimplantation development in mouse: important role of retinal dehydrogenase type 2 in synthesis of all-trans-retinoic acid. Dev Biol. 2000;220:379–391. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Joseph JA. Quantifying cellular oxidative stress by dichlorofluorescein assay using microplate reader. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:612–616. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson WH, Yang X, Choi YE, Jones DP, Kehrer JP. Thioredoxin and its role in toxicology. Toxicol Sci. 2004;78:3–14. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittgen HG, van Kempen LC. Reactive oxygen species in melanoma and its therapeutic implications. Melanoma Res. 2007;17:400–409. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3282f1d312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia C, Hu J, Ketterer B, Taylor JB. The organization of the human GSTP1-1 gene promoter and its response to retinoic acid and cellular redox status. Biochem J. 1996;313:155–162. doi: 10.1042/bj3130155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia C, Taylor JB, Spencer SR, Ketterer B. The human glutathione S-transferase P1–1 gene: modulation of expression by retinoic acid and insulin. Biochem J. 1993;292:845–850. doi: 10.1042/bj2920845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng WL, Ong DE. Spatial and temporal patterns of expression of cellular retinol-binding protein and cellular retinoic acid-binding proteins in rat uterus during early pregnancy. Biol Reprod. 1998;58:963–970. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.4.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng WL, Sierra-Rivera E, Luan J, Osteen KG, Ong DE. Retinoic acid synthesis and expression of cellular retinol-binding protein and cellular retinoic acid-binding protein type II are concurrent with decidualization of rat uterine stromal cells. Endocrinology. 2000;141:802–808. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.2.7323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Chen H, Zhao H, Liu K, Luo D, Chen Y, Chen Y, Yang X, Gu Q, Xu X. Inhibition of JAK2/STAT3-mediated VEGF upregulation under high glucose conditions by PEDF through a mitochondrial ROS pathway in vitro. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:64–71. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]