Abstract

SCCRO/DCUN1D1/DCN1 (squamous cell carcinoma-related oncogene/defective in cullin neddylation 1 domain containing 1/defective in cullin neddylation) serves as an accessory E3 in neddylation by binding to cullin and Ubc12 to allow efficient transfer of Nedd8. In this work we show that SCCRO has broader, pleiotropic effects that are essential for cullin neddylation in vivo. Reduced primary nuclear localization of Cul1 accompanying decreased neddylation and proliferation in SCCRO−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts led us to investigate whether compartmentalization plays a regulatory role. Decreased nuclear localization, neddylation, and defective proliferation in SCCRO−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts were rescued by transgenic expression of SCCRO. Expression of reciprocal SCCRO and Cul1-binding mutants confirmed the requirement for SCCRO in nuclear translocation and neddylation of cullins in vivo. Nuclear translocation of Cul1 by tagging with a nuclear localization sequence allowed neddylation independent of SCCRO, but at a lower level. We found that in the nucleus, SCCRO enhances recruitment of Ubc12 to Cul1 to promote neddylation. These findings suggest that SCCRO has an essential role in neddylation in vivo involving nuclear localization of neddylation components and recruitment and proper positioning of Ubc12.

Keywords: Nuclear Translocation, Protein Degradation, Ubiquitin, Ubiquitin Ligase, Ubiquitination, Cullin, Neddylation, Ubc12

Introduction

The cullin family of proteins anchor Cullin RING finger-type E3 ubiquitination complexes (CRL)4 that regulate the degradation and activity of proteins involved in a wide range of cellular processes (1, 2). Several reports have shown that the activity of CRL complexes is primarily regulated by neddylation, a process mechanistically analogous to ubiquitination, where the cullin family of proteins are covalently modified by ubiquitin (Ub)-like protein Nedd8 (3–11). All cullin proteins in humans (Cul1, Cul2, Cul3, Cul4a, Cul4b, Cul5, and PARC) are subject to neddylation, with the exception of Cul7 (12, 13). Lethality resulting from knocking out core components in all organisms studied (except budding yeast) emphasizes the indispensable role of neddylation in normal cellular function (14–20).

Like ubiquitination, neddylation involves a sequential, tripartite enzymatic cascade (21, 22). The vertebrate enzymes for neddylation are the heterodimeric complex APP-BP1/Uba3 (E1) and Ubc12 or Ube2f (E2) (21, 23–25). The presence of enzymatic activity in the RING domain of Roc1 combined with its requirement and sufficiency to promote Nedd8 conjugation in vitro supports a role for Roc1 as the E3 for neddylation (26). Recent work identified a novel protein SCCRO/DCUN1D1/DCN1 (squamous cell carcinoma-related oncogene/defective in cullin neddylation 1, domain containing 1/defective in cullin neddylation) that binds to components of the E3 complex for neddylation (Ubc12 and Cullin-Roc1) and increases neddylation efficiency in vitro (27–30). Biochemical studies and structural modeling suggest that DCN1 functions as an E3 promoting neddylation by reducing nonspecific Rub1 (Nedd8 in mammals) discharge and directing the active site of Ubc12 toward the acceptor lysine in Cdc53 (Cul1 in mammals) (31). These observations suggest that SCCRO is a nonessential component of the neddylation E3 complex that increases efficiency of the reaction. In contrast to in vitro observations, in vivo studies suggest that SCCRO has an essential role in neddylation, as knocking out SCCRO orthologs DCN1/Dcn1p in Caenorhabditis elegans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae results in reduced Cul3 neddylation and lethality (30). Our work shows that although SCCRO−/− mice are viable, neddylation is reduced, and these mice have several developmental defects including male specific infertility, runting, and high rates of perinatal mortality.5 In this work we show that in addition to assembling the neddylation E3 complex, SCCRO facilitates the subcellular localization of neddylation components, which is required for cullin neddylation in vivo. These findings help to explain the differential requirement for SCCRO in in vitro and in vivo models.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

Human SCCRO and its mutants were cloned into pCMV-HA vector (Clontech) by standard PCR methodology (27). Double HA-tagged human Roc1 cDNA as well as Cul1 and its mutants were either obtained from a commercial source (Addgene) or developed using GeneTailor Site-directed Mutagenesis System (Invitrogen) and sequence verified. Nuclear export sequence (NES) (32) and nuclear localization signal (NLS) (33) tags were coded by 5′-GACCTCCAAAAGAAGCTGGAGGAGCTGGAGCTGGACGAG-3′ and 5′-GATCCAAAAAAGAAGAGAAAGGTAGATCCAAAGAGAAAGAAGAAGGTA-3′, respectively, and were cloned into the N-terminal region of SCCRO or Cul1.

Cell Culture, Growth Assay, Transfection, Retrovirus Infection, and Fractionation

Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were harvested from littermate wild-type, heterozygous, or SCCRO−/− embryos at age 12 days after coitus. MEF and human U2OS were cultured with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (and containing 55 μm 2-mercaptoethanol for MEF) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. For proliferation assays, 0.2 million MEFs were seeded, cells were harvested daily, and cell numbers were counted, in triplicate. To introduce the SCCRO or SCCRO mutant into MEFs, we used the pBABE retroviral system. Transfections were carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were prepared using established protocol with modifications. In brief, cells were harvested and resuspended in buffer A, pH 7.9 (10 mm HEPES, 10 mm KCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 0.1 mm EGTA, and 1 mm DTT) for 15 min on ice. Nonidet P-40 was then added to 0.6%. After a quick vortex, nuclei were separated from cytoplasm by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 s. Nuclei were further lysed with an equal volume of radioimmune precipitation assay buffer.

UV Irradiation

MEFs were irradiated at 300 milliJoules using GS Gene Linker (Bio-Rad). Cells were then incubated for another hour before harvest for immunoblotting or fixation for immunofluorescence.

Antibodies and Immunoprecipitation

The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-Cul1 (Zymed Laboratories), anti-Cul3 (BD Biosciences), anti-Roc1 (Abcam), anti-Ub (P4D1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-HA (Covance), anti-Myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-FLAG (Sigma), anti-tubulin (Calbiochem), and anti-P300/CBP-associated factor (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Anti-SCCRO monoclonal antibody was produced and utilized as described previously (27). Immunoprecipitations were performed essentially as described earlier (34). In brief, cells were lysed using mammalian cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling). Lysate was incubated with 20 μl of anti-HA-conjugated agarose beads (Abcam) by gentle rocking at 4 °C overnight. The beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and once with PBS. Bound proteins were eluted by the addition of 2× Laemmli buffer, resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and analyzed by immunoblotting.

In Vivo and in Vitro Neddylation Assay

For in vivo neddylation, cell lysates were directly subjected to immunoblotting for cullin(s). In vitro neddylation was performed essentially as described earlier (27). The source of Cul-Roc1 substrate was either endogenous or transfected cullins. The reaction mixture contained 2 μm recombinant Nedd8, 10 nm E1, and 4 mm ATP.

Immunofluorescence

Cy3-conjugated anti-HA, anti-Myc, and anti-FLAG and FITC-conjugated anti-HA antibodies were obtained from a commercial source (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Cells transfected with plasmid(s) were seeded in 6-well plates with cover glass. Twenty four hours after transfection, cells were washed (PBS) and fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 10 min. The fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 min, incubated in blocking buffer (PBS containing 10% FBS) for 30 min and stained overnight at 4°C with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies. The cells were washed three times with PBS, counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), covered by ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent (Invitrogen), and examined with a Leica inverted confocal microscope fitted with appropriate fluorescence filters. For Cul1 staining, FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody was used. To calculate the percentage of cells with nuclear or nonnuclear localization, a minimum of 200 cells were counted for each experiment. All experiments have been repeated at least three times. Fisher's exact test was used to compare results from localization studies, and a p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Analysis of Mutant Mice

Spleen, lymph nodes, and other organs were dissected free from littermates. Tissues were minced into dissociated cells in equal volume of media. The cell numbers were then counted, and cell sizes were determined by forward scatter analysis using flow cytometry.

RESULTS

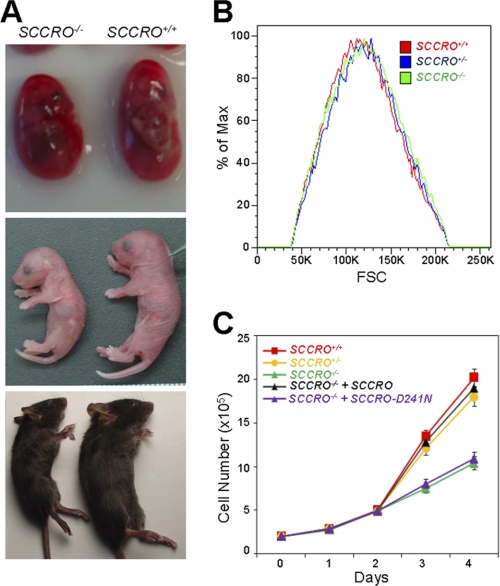

SCCRO Has Essential Function in Vivo

Given the discrepancy in the function of SCCRO in vivo and in vitro, we first aimed to develop a model to define the requirement of SCCRO in vivo and assess mechanisms involved. Because body size changes can be attributed to either a decrease in cell size, cell number or both, runting in SCCRO−/− mice provides an attractive model to investigate the in vivo requirement and functions of SCCRO (Fig. 1A) (35). We first confirmed that the smaller size of SCCRO−/− mice is independent of gender or genetic background.5 In addition, no obvious organ or hormonal defects that could explain the reduced body size were identifiable.5 We assessed cell size and number in several organs from littermate SCCRO−/− and SCCRO+/+ mice, showing no alterations in cell size in any organs tested (data not shown). As fewer cells were present in spleen and lymphatic tissues of SCCRO−/− mice, we focused on defects in proliferation. We isolated primary MEFs from day 12 SCCRO+/+, SCCRO+/−, and SCCRO−/− littermate embryos. No detectable morphological differences were observed in MEFs of different genotypes. Forward scatter analysis using flow cytometry also revealed no significant differences in the size of these MEFs (Fig. 1B). However, a decrease in proliferation was seen in SCCRO−/− MEFs, confirming that the loss of SCCRO has physiological consequences (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

SCCRO enhances cell proliferation by promoting cullin neddylation. A, representative SCCRO+/+ and SCCRO−/− mice at embryo (top), birth (middle), and weaning (bottom) stages. B, cell size of SCCRO+/+, SCCRO+/−, and SCCRO−/− MEFs determined by forward scatter analysis (FSC), showing no differences. C, cell proliferation assay showing reduced proliferation in SCCRO−/− relative to SCCRO+/+ and SCCRO+/− MEFs. Retroviral delivery of SCCRO but not SCCRO-D241N rescued the proliferation defect in SCCRO−/− MEFs.

In Vivo Functions of SCCRO Involve Its Neddylation Activity

To determine whether reduced proliferation of SCCRO−/− MEF is related to defective neddylation, we assessed levels of neddylated cullins. Despite similar levels of neddylation components (APP-BP1, Cul1, Ubc12, and Nedd8) in SCCRO−/− and SCCRO+/+ MEFs, there was a decrease in the basal level of neddylated Cul1 in SCCRO−/− MEF lysates as detected by immunoblotting (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 2, and supplemental Fig. 1). This difference was even more pronounced when neddylation was activated by supplementing the lysates with E1 (APP-BP1/Uba3), Nedd8, and ATP prior to immunoblotting (Fig. 2B). Moreover, global ubiquitination was also reduced in SCCRO−/− MEFs, suggesting that reduced cullin neddylation has functional consequences (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Neddylation, nuclear localization of Cul1, and levels of ubiquitinated proteins are reduced in SCCRO−/− MEFs. A, immunoblotting with antibodies as indicated on lysates from MEFs before and after UV irradiation showing activation of cullin neddylation in SCCRO+/+ but not SCCRO−/− MEFs. B, immunoblots with antibodies against Cul1 and Ub on lysates from 2A after activation of neddylation by addition of E1, E2, Nedd8, and ATP. Levels of neddylated Cul1 and ubiquitinated proteins was higher is SCCRO+/+ MEFs. C, immunoblot of cell lysates from MEFs subjected to activated neddylation assay. Levels of neddylated Cul1 were higher in SCCRO+/+ MEFs. Defective neddylation in SCCRO−/− MEFs was rescued by retroviral delivery of SCCRO but not SCCRO-D241A. D, immunofluorescence using anti-Cul1 antibodies on MEFs showing higher proportion of SCCRO+/+ with primary nuclear localization (compare lanes 1 and 2). Retroviral delivery of SCCRO (lane 3) but not SCCRO-D241A (lane 4) promoted nuclear translocation of Cul1 in SCCRO−/− MEFs. Exposure of MEFs to UV irradiation resulted in increased nuclear translocation of Cul1 in SCCRO+/+ MEFs (lane 5) but had no effect on SCCRO−/− MEFs (lane 6).

To determine whether the defect in cell proliferation is due to a loss of SCCRO-augmented neddylation, we expressed SCCRO in SCCRO−/− MEFs by retroviral infection and assessed effects on neddylation and proliferation. We expressed SCCRO-D241N, a mutant previously shown to lose neddylation promoting activity, as a control (27). Immunoblotting analysis showed that the levels of SCCRO in SCCRO−/− MEFs after retroviral infection were equal to that in SCCRO+/+ MEF (Fig. 2C). Expression of SCCRO but not SCCRO-D241N rescued both defective proliferation and Cul1 neddylation in SCCRO−/− MEF to wild-type levels (Figs. 1C and 2C). These findings suggest an association between the neddylation activity of SCCRO and its function in vivo.

SCCRO Promotes Nuclear Translocation and Neddylation of Cul1

The difference in requirement for SCCRO in vitro and in vivo may be explained by several factors, including post-translational modifications, compartmentalization, and/or requirement for other proteins/factors in the reaction. Work from Furukawa et al. (36) suggests that nuclear translocation may be required for cullin neddylation. Accordingly, we compared the subcellular distribution of Cul1 in SCCRO−/− and SCCRO+/+ MEFs. Interestingly, Cul1 was primarily nuclear in a significantly higher proportion of SCCRO+/+ (174/200; 87%) compared with SCCRO−/− (50/200; 25%) MEFs (Fig. 2D). Transgenic expression of SCCRO, but not SCCRO-D241N, in SCCRO−/− MEFs rescued the nuclear localization of Cul1 (Fig. 2D). To confirm that these observations are of physiological significance, we assessed cullin localization in response to neddylation-promoting stimuli. Among the various conditions tested, we found that UV irradiation resulted in the greatest increase in Cul1 neddylation and nuclear localization in SCCRO+/+ MEFs (Fig. 2, A and D). In contrast, no change in Cul1 neddylation or nuclear localization was observed in SCCRO−/− MEFs upon UV exposure (Fig. 2, A and D). Combined, these observations suggest that SCCRO plays an important role in nuclear translocation of Cul1, which may explain differences in its requirement for neddylation in vivo and in vitro.

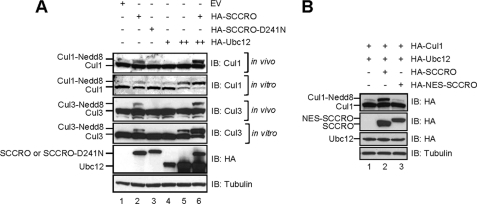

SCCRO-mediated Nuclear Transport Is Required for Cul1 Neddylation in Vivo

To define the cause for the differential requirement for SCCRO in vivo and in vitro, we elected to use U2OS, an established cell line that is more amenable to experimental manipulations than MEFs. For in vivo neddylation, U2OS cells were transfected with HA-Ubc12 and HA-SCCRO or HA-SCCRO-D241N and lysates subjected to immunoblotting for Cul1 or Cul3. For in vitro neddylation, reactions were activated by the addition of Nedd8, E1, and ATP to the lysates prior to immunoblotting. Consistent with prior findings, expression of Ubc12 alone was sufficient to promote cullin neddylation in vitro with co-expression of SCCRO enhancing the reaction (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 4 and 5 with 6). In contrast, whereas SCCRO promoted Cul1 and Cul3 neddylation in vivo, expression of Ubc12 alone had no effect (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 5). Co-expression of SCCRO with Ubc12 synergistically enhanced Cul1 neddylation (Fig. 3A, lane 6). Given that Ubc12 is primarily nuclear, these findings suggest that SCCRO-promoted nuclear translocation may be required for neddylation of cullins in vivo.

FIGURE 3.

SCCRO-mediated nuclear translocation of Cul1 is required for its neddylation in vivo. A, immunoblots on lysates from U2OS cells transfected with the indicated constructs and probed with antibodies against Cul1, Cul3, HA, and tubulin. SCCRO is required for cullin neddylation in vivo (top and third panels, lane 2) and augments the in vitro reaction when co-expressed with Ubc12 (second and fourth panels, lane 6). B, immunoblot on lysates from U2OS cells transfected with the indicated constructs showing no increase in Cul1 neddylation in HA-NES-SCCRO-transfected cells.

To assess the requirement of SCCRO-promoted nuclear translocation of Cul1 for neddylation, we developed a SCCRO construct with a canonical NES to block its nuclear translocation. Co-transfection of HA-Cul1 with HA-SCCRO or HA-NES-SCCRO in U2OS cells followed by immunoblotting for HA showed that SCCRO but not NES-SCCRO promotes Cul1 neddylation (Fig. 3B; compare lanes 2 and 3). Taken together, these findings suggest that SCCRO enhances cullin neddylation by promoting its nuclear translocation.

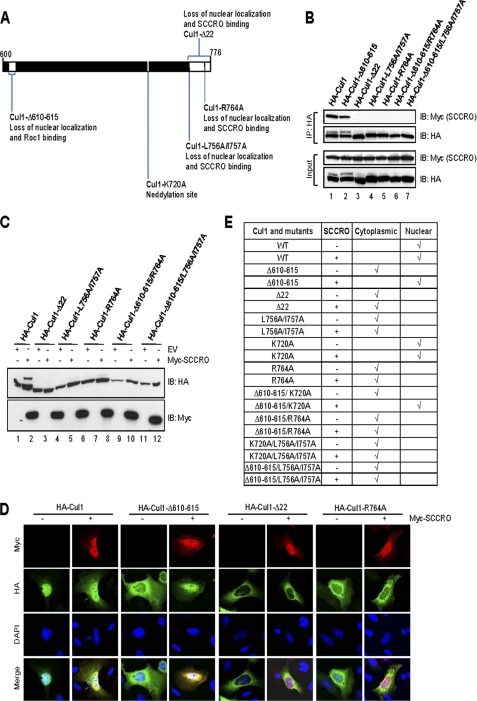

Binding Is Required for SCCRO-promoted Nuclear Translocation and Neddylation of Cul1

Structural modeling shows that that the C terminus of SCCRO binds to the Cul1 C terminus in the terminal helix and the loop between the C-terminal two β strands (37). Consistent with this, we found that deletion or mutations in selected conserved residues within the C terminus of Cul1 resulted in loss of binding based on immunoprecipitation assays (Fig. 4, A and B). To determine the requirement for binding to SCCRO for nuclear localization and neddylation, we expressed loss of binding mutants in U2OS cells and assessed subcellular localization and neddylation of Cul1. We found that co-expression of SCCRO, but not SCCRO-D241N, increased the fraction of cells in which HA-Cul1 was primarily nuclear from ∼72% to ∼94% (Fig. 4D). Correspondingly, Cul1 mutants that lose SCCRO binding could not be neddylated or translocated to the nucleus even when co-expressed with SCCRO (Fig. 4, C–E).

FIGURE 4.

Binding to SCCRO is required for neddylation and nuclear localization of Cul1. A, schematic representation of the C terminus of Cul1 showing cullin mutants used in these experiments. B, immunoblot on lysates from U2OS cells transfected with Myc-SCCRO and HA-Cul1 or selected mutants probed with the indicated antibodies following HA immunoprecipitation. SCCRO binds to HA-Cul1 and HA-Cul1-Δ610–615 (lanes 1 and 2) but not C-terminal Cul1 mutants (lane 3–7). C, immunoblots for Cul1 on lysates from U2OS cells co-transfected with Cul1 or its mutants with or without SCCRO showing mutants that lose SCCRO binding cannot be neddylated. D, immunofluorescence using Cy3-conjugated anti-Myc antibody and FITC-conjugated anti-HA antibody on U2OS cells transfected with HA-Cul1 or indicated HA-tagged Cul1 mutants with or without Myc-SCCRO. HA-Cul1 (first lane) was primarily nuclear (∼74%) whereas Cul1 mutants (third, fifth, and seventh lanes) were primarily cytoplasmic in the absence of SCCRO expression. Co-expression of SCCRO increased the proportion of HA-Cul1 and rescued the localization defect of Cul1-Δ610–615 with primary nuclear localization. E, U2OS cells were transfected with Cul1 or its mutants with or without SCCRO. The results of Cul1 localization monitored by immunofluorescence by counting 200 cells for each transfection is tabulated. Nuclear localization by SCCRO requires the Cul1 C-terminal sequence.

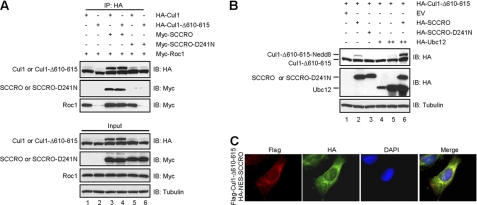

Prior studies show that the Cul1-Δ610–615, which has reduced Roc1 binding, localizes to the cytoplasm, suggesting that binding to Roc1 may be involved in nuclear translocation. We confirmed that HA-Cul1-Δ610–615 does not bind to Roc1 and is primarily cytoplasmic when expressed in U2OS cells by immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence analyses, respectively (Figs. 4D and 5A, lane 2). Co-expression of SCCRO resulted in nuclear translocation of HA-Cul1-Δ610–615 (Fig. 4D). Validating a primary role for SCCRO in compartmentalization of cullins, the Cul1-Δ610–615/R764A double mutant, that loses both Roc1 and SCCRO binding, could not be translocated to the nucleus under any conditions tested (Fig. 4E).

FIGURE 5.

SCCRO rescues nuclear localization and neddylation of Cul1-Δ610–615. A, immunoblot on lysates from U2OS cells transfected with the indicated constructs and probed with anti-Myc or anti-HA antibodies following HA immunoprecipitation showing increased interaction between Roc1 and HA-Cul1-Δ610–615 with SCCRO co-expression (compare lanes 4 with 2 and 6). B, immunoblot on lysates from U2OS cells transfected with the indicated constructs probed with anti-HA antibodies showing rescue of HA-Cul1-Δ610–615 neddylation defect by SCCRO (top panel, lanes 2 and 6). C, immunofluorescence on U2OS cells co-transfected with FLAG-Cul1-Δ610–615 and HA-NES-SCCRO using Cy3-conjugated anti-FLAG antibody and FITC-conjugated HA antibody showing nuclear exclusion of SCCRO and loss of nuclear translocation of Cul1-Δ610–615.

Interestingly, defective neddylation of Cul1-Δ610–615 was also salvaged by co-expression of SCCRO but not SCCRO-D241N (Fig. 5B, lanes 2 and 3). In contrast, expression of NES-SCCRO was unable to promote nuclear translocation of Cul1-Δ610–615 (Fig. 5C). Because Roc1 is required for cullin neddylation, these findings suggest that SCCRO may help to recruit Roc1 to Cul1-Δ610–615 in the cytoplasm prior to nuclear translocation (36). To investigate this possibility, we performed immunoblots after HA immunoprecipitation of lysates from U2OS cells co-transfected with Myc-Roc1 and HA-Cul1-Δ610–615 with Myc-SCCRO or Myc-SCCRO-D241N. Binding between Cul1-Δ610–615 and Roc1 was enriched with Myc-SCCRO co-expression but not Myc-SCCRO-D241N (Fig. 5A, lane 4). To validate these findings, we tagged Cul1-Δ610–615 with nuclear localization sequence (NLS-Cul1-Δ610–615) thereby targeting it to the nucleus independent of SCCRO. Co-expression of SCCRO could not rescue neddylation of NLS-Cul1-Δ610–615, suggesting that SCCRO recruits Roc1 to Cul1-Δ610–615 prior to nuclear transport (Fig. 6A). Fractionation of the transfected cells followed by immunoblot analysis showed that the nuclear fraction of Roc1 increased with co-expression of Cul1-Δ610–615 with SCCRO (Fig. 6B, lane 4), but not in cells coexpressing NLS-Cul1-Δ610–615 (Fig. 6C, lane 4). Combined, these findings suggest that binding between SCCRO and Cul1 is required for both nuclear transport and neddylation in vivo.

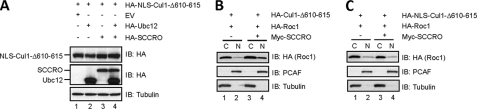

FIGURE 6.

NLS-Cul1-Δ610–615 cannot be neddylated in vivo. A, immunoblot on lysates from U2OS cells transfected with the indicated constructs showing that neither HA-Ubc12 nor HA-SCCRO expression promotes neddylation of NLS-Cul1-Δ610–615. B and C, immunoblot on cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) fractions of lysates from U2OS cells transfected with the indicated constructs probed with anti-HA antibody showing enrichment of Roc1 in the nuclear fraction of cells co-expressing SCCRO with HA-Cul1-Δ610–615 (B, top panel, lane 4) but not with HA-NLS-Cul1-Δ610–615 (C, top panel, lane 4). P300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF) and tubulin are nuclear and cytoplasmic loading controls, respectively.

SCCRO Promotes Recruitment of Ubc12 to the Neddylation E3 Complex in the Nucleus

The role of SCCRO in nuclear localization of Cul1 does not explain its effect on neddylation in in vitro reactions. To determine whether nuclear transport is the only contribution of SCCRO in augmenting neddylation, we developed a system to monitor neddylation independent of Cul1 nuclear localization. Transfection of U2OS cells with Cul1 tagged with nuclear localization sequence (NLS-Cul1) followed by immunofluorescence confirmed its nuclear localization (supplemental Fig. 2). Co-transfection of Ubc12 was sufficient to promote neddylation of NLS-Cul1 but not wild-type Cul1. Expression of SCCRO also enhanced neddylation of NLS-Cul1. Co-expression of SCCRO with Ubc12 synergistically enhanced neddylation of NLS-Cul1 in vivo (Fig. 7A, lane 4). These findings suggest that in addition to subcellular localization, SCCRO promotes neddylation by other mechanisms in vivo. Scott et al. showed that SCCRO restricts the otherwise flexible Roc1-Ubc12∼Nedd8 and orients the Ubc12 active site toward the Cul1 acceptor Lys (31). This increases the efficiency of Nedd8 transfer to Cul1. However, its effect on neddylation of NLS-Cul1 in vivo appears more pronounced than that observed in in vitro reactions where molar excess of SCCRO is required to see any activity. Accordingly, in addition to proper positioning to facilitate Nedd8 transfer, we questioned whether SCCRO also promotes assembly of the neddylation E3 complex by enhancing recruitment of E2 in vivo. Immunoprecipitation of lysates for HA-Ubc12 showed an increase in Cul1 binding when SCCRO was co-expressed (Fig. 7B). We have shown previously that SCCRO preferentially binds to Ubc12∼Nedd8 thioester, suggesting that recruitment of Ubc12 by SCCRO constitutes a functional complex. Combined, these observations suggest that in addition to Cul1 nuclear localization, SCCRO enhances neddylation E3 activity in vivo by promoting recruitment of E2 to the neddylation complex.

FIGURE 7.

SCCRO promotes recruitment of Ubc12 onto Cul1-Roc1 complex after nuclear translocation. A, immunoblot on lysates from U2OS cells transfected with the indicated constructs showing an increase in neddylation of HA-NLS-Cul1 with co-expression of HA-Ubc12 or HA-SCCRO (lanes 2 and 3). A synergistic effect was seen with co-expression of both HA-Ubc12 and HA-SCCRO (lane 4). B, immunoblot on lysates from U2OS cells transfected with the indicated constructs following anti-HA immunoprecipitation showing an increase in interaction between Ubc12 and Cul1 with SCCRO co-expression (lane 2).

DISCUSSION

Inasmuch as mechanisms are highly conserved, conjugation of Ub and Ub-like protein also share factors regulating reaction dynamics (38, 39). The rate-limiting step in Ub and Ub-like protein conjugation is E3 activity. Regulation of E3 activity is most closely regulated for ubiquitination by CRL-type ligases and neddylation of cullins. In both reactions, the RING domain in Roc1 provides the enzymatic activity, and assembly of the complex serves as the rate-limiting step. Although the presence of Roc1 along with charged E2 is sufficient in vitro, other factors are involved in in vivo ligation activity (4, 26, 36, 40, 41). For CRL complexes, activation of E3 requires neddylation of the cullin in vivo, but can proceed without cullin neddylation in vitro (5, 41). Prior studies show that neddylation affects CRL activity by promoting assembly of the complex through recruitment and positioning of the E2 to allow Ub transfer and chain extension on the substrate protein (8, 42, 43). Combined, our findings that SCCRO recruits E2 and the work of Scott et al. showing that it promotes a favorable orientation for efficient Nedd8 transfer suggest that SCCRO affects the activity of neddylation E3 complexes as neddylation does for cullins in CRL complexes.

Although this defines the biochemical role of neddylation and SCCRO in the respective E3 activity, it fails to explain why neddylation and SCCRO are required in vivo but not in vitro for Ub and Nedd8 conjugation, respectively. Our laboratory, as well as others, have shown that neddylation of cullins can occur efficiently in vitro in the absence of SCCRO (27, 28). This would suggest that the role of SCCRO may not be essential. However, decreased neddylation combined with the detrimental effects of knocking out SCCRO in in vivo model organisms suggest that its function is required (30). Our findings help to explain this difference by showing that SCCRO promotes nuclear translocation of Cul1-Roc1 complexes in vivo. We found that Ubc12 exists almost exclusively in the nucleus (supplemental Fig. 3). Accordingly, for neddylation to occur, Ubc12 either has to be translocated to cytoplasm or Cullin-Roc1 complexes to the nucleus. The importance of nuclear transport is supported by the finding that NLS-Cul1, but not wild-type Cul1, can be neddylated by the expression of Ubc12 alone. However, even after nuclear localization of Cul1 by tagging with NLS, co-expression of SCCRO with Ubc12 synergistically enhances neddylation, at levels much higher that that seen in vitro. These observations may be explained by enhanced recruitment of Ubc12 to Cul1-Roc1 by SCCRO in vivo.

Our findings raise several possibilities and questions. As the SCCRO-Cul1-Roc1 complex is relatively large, it requires active transport through a nuclear pore. However, none of the proteins in the complex contains a canonical nuclear targeting sequence. Although it is possible that a cryptic nuclear targeting sequence may be present, it is also possible that other unidentified proteins/factors may be involved in nuclear translocation. Second, given the conservation in reaction dynamics, these findings raise the possibility that CRL activity may also be regulated by compartmentalization. Interestingly, in our preliminary studies we found that neddylated cullins primarily exist in the nucleus, raising the possibility of ubiquitination occurring in the nucleus (supplemental Fig. 4). These findings need to be reconciled with reports suggesting SCCRO3 acts at the membrane to promote neddylation (44). Similar to work from Ma et al. (45), we found that SCCRO3 functions as a tumor suppressor in human cancers rather than an oncogene like other SCCRO family members.6 Our results suggest that SCCRO3 binds to Cul1 in vivo but has no independent neddylation activity, suggesting that its function may be context-dependent in vivo. Finally, as SCCRO4/DCUN1D4 and SCCRO5/DCUN1D5 both have a functional NLS in their N terminus, their role in neddylation remains to be explained.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christopher Lima and Andrew Koff for many helpful discussions and for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a George H. A. Clowes Memorial Research Career Development Award from the American College of Surgeons (to B. S.), a Clinical Innovator Award from Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (to B. S. and Y. R.), the Falcone Fund (to B. S.), and a Matheson fellowship (to Y. R.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–4.

A. J. Kaufman, G. Huang, R. Ryan, L. Huryn, G. Hunnicut, Y. Romin, P. Morris, K. Manora, Y. Ramanathan, and B. Singh, unpublished data.

C. Stock, G. Huang, V. Weeda, C. Bommelije, K. Shah, S. Bains, E. Buss, Y. Ramanathan, and B. Singh, unpublished data.

- CRL

- Cullin RING ligases

- DCUN1D1

- defective in cullin neddylation 1, domain containing 1

- DCN1

- defective in cullin neddylation

- E1

- ubiquitin (or Nedd8)-activating enzyme

- E2

- ubiquitin (or Nedd8) carrier protein

- E3

- ubiquitin (or Nedd8)-protein isopeptide ligase

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- NES

- nuclear export sequence

- NLS

- nuclear localization signal

- SCCRO

- squamous cell carcinoma-related oncogene

- Ub

- ubiquitin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hershko A., Ciechanover A. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 425–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mukhopadhyay D., Riezman H. (2007) Science 315, 201–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kamitani T., Kito K., Nguyen H. P., Yeh E. T. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 28557–28562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu K., Chen A., Tan P., Pan Z. Q. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 516–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Read M. A., Brownell J. E., Gladysheva T. B., Hottelet M., Parent L. A., Coggins M. B., Pierce J. W., Podust V. N., Luo R. S., Chau V., Palombella V. J. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 2326–2333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Podust V. N., Brownell J. E., Gladysheva T. B., Luo R. S., Wang C., Coggins M. B., Pierce J. W., Lightcap E. S., Chau V. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 4579–4584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morimoto M., Nishida T., Honda R., Yasuda H. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 270, 1093–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kawakami T., Chiba T., Suzuki T., Iwai K., Yamanaka K., Minato N., Suzuki H., Shimbara N., Hidaka Y., Osaka F., Omata M., Tanaka K. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 4003–4012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hotton S. K., Callis J. (2008) Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 467–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Parry G., Estelle M. (2004) Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 15, 221–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Petroski M. D., Deshaies R. J. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 9–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim S. S., Shago M., Kaustov L., Boutros P. C., Clendening J. W., Sheng Y., Trentin G. A., Barsyte-Lovejoy D., Mao D. Y., Kay R., Jurisica I., Arrowsmith C. H., Penn L. Z. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 9616–9622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Skaar J. R., Florens L., Tsutsumi T., Arai T., Tron A., Swanson S. K., Washburn M. P., DeCaprio J. A. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 2006–2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wada H., Yeh E. T., Kamitani T. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 17008–17015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones D., Candido E. P. (2000) Dev. Biol. 226, 152–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Osaka F., Saeki M., Katayama S., Aida N., Toh-E. A., Kominami K., Toda T., Suzuki T., Chiba T., Tanaka K., Kato S. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 3475–3484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tateishi K., Omata M., Tanaka K., Chiba T. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 155, 571–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Noureddine M. A., Donaldson T. D., Thacker S. A., Duronio R. J. (2002) Dev. Cell 2, 757–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dharmasiri S., Dharmasiri N., Hellmann H., Estelle M. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 1762–1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tan M., Davis S. W., Saunders T. L., Zhu Y., Sun Y. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 6203–6208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liakopoulos D., Doenges G., Matuschewski K., Jentsch S. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 2208–2214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scheffner M., Nuber U., Huibregtse J. M. (1995) Nature 373, 81–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huang D. T., Ayrault O., Hunt H. W., Taherbhoy A. M., Duda D. M., Scott D. C., Borg L. A., Neale G., Murray P. J., Roussel M. F., Schulman B. A. (2009) Mol. Cell 33, 483–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bohnsack R. N., Haas A. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 26823–26830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Osaka F., Kawasaki H., Aida N., Saeki M., Chiba T., Kawashima S., Tanaka K., Kato S. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 2263–2268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morimoto M., Nishida T., Nagayama Y., Yasuda H. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 301, 392–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kim A. Y., Bommeljé C. C., Lee B. E., Yonekawa Y., Choi L., Morris L. G., Huang G., Kaufman A., Ryan R. J., Hao B., Ramanathan Y., Singh B. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33211–33220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kurz T., Chou Y. C., Willems A. R., Meyer-Schaller N., Hecht M. L., Tyers M., Peter M., Sicheri F. (2008) Mol. Cell 29, 23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang X., Zhou J., Sun L., Wei Z., Gao J., Gong W., Xu R. M., Rao Z., Liu Y. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24490–24494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kurz T., Ozlü N., Rudolf F., O'Rourke S. M., Luke B., Hofmann K., Hyman A. A., Bowerman B., Peter M. (2005) Nature 435, 1257–1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Scott D. C., Monda J. K., Grace C. R., Duda D. M., Kriwacki R. W., Kurz T., Schulman B. A. (2010) Mol. Cell 39, 784–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Henderson B. R., Eleftheriou A. (2000) Exp. Cell Res. 256, 213–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kalderon D., Roberts B. L., Richardson W. D., Smith A. E. (1984) Cell 39, 499–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sarkaria I., O.-charoenrat P., Talbot S. G., Reddy P. G., Ngai I., Maghami E., Patel K. N., Lee B., Yonekawa Y., Dudas M., Kaufman A., Ryan R., Ghossein R., Rao P. H., Stoffel A., Ramanathan Y., Singh B. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 9437–9444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Trumpp A., Refaeli Y., Oskarsson T., Gasser S., Murphy M., Martin G. R., Bishop J. M. (2001) Nature 414, 768–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Furukawa M., Zhang Y., McCarville J., Ohta T., Xiong Y. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 8185–8197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zheng N., Schulman B. A., Song L., Miller J. J., Jeffrey P. D., Wang P., Chu C., Koepp D. M., Elledge S. J., Pagano M., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W., Harper J. W., Pavletich N. P. (2002) Nature 416, 703–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Capili A. D., Lima C. D. (2007) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 17, 726–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dye B. T., Schulman B. A. (2007) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 36, 131–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ptak C., Prendergast J. A., Hodgins R., Kay C. M., Chau V., Ellison M. J. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 26539–26545 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wu K., Chen A., Pan Z. Q. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 32317–32324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Duda D. M., Borg L. A., Scott D. C., Hunt H. W., Hammel M., Schulman B. A. (2008) Cell 134, 995–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Saha A., Deshaies R. J. (2008) Mol. Cell 32, 21–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Meyer-Schaller N., Chou Y. C., Sumara I., Martin D. D., Kurz T., Katheder N., Hofmann K., Berthiaume L. G., Sicheri F., Peter M. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12365–12370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ma T., Shi T., Huang J., Wu L., Hu F., He P., Deng W., Gao P., Zhang Y., Song Q., Ma D., Qiu X. (2008) Cancer Sci. 99, 2128–2135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]