Abstract

We have established functions of the stimulus dependent MAPKs, ERK1/2 and ERK5 in DRG, motor neuron, and Schwann cell development. Surprisingly, many aspects of early DRG and motor neuron development were found to be ERK1/2 independent and Erk5 deletion had no obvious effect on embryonic PNS. In contrast, Erk1/2 deletion in developing neural crest resulted in peripheral nerves that were devoid of Schwann cell progenitors, and deletion of Erk1/2 in Schwann cell precursors caused disrupted differentiation and marked hypomyelination of axons. The Schwann cell phenotypes are similar to those reported in neuregulin-1 and ErbB mutant mice and neuregulin effects could not be elicited in glial precursors lacking Erk1/2. ERK/MAPK regulation of myelination was specific to Schwann cells, as deletion in oligodendrocyte precursors did not impair myelin formation, but reduced precursor proliferation. Our data suggest a tight linkage between developmental functions of ERK/MAPK signaling and biological actions of specific RTK-activating factors.

Introduction

Nervous system development and function is dependent upon a variety of soluble and membrane bound trophic stimuli, many of which act through receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). Even though more than 50 RTKs are present in the human genome, a handful of signaling pathways are repeatedly implicated in downstream cellular responses, particularly the MAPK, PI-3 kinase, JAK-STAT, and PLC pathways. Surprisingly, there has been little progress in assigning specific developmental functions to individual pathways (Lemmon and Schlessinger, 2010). Indeed, the many in vitro studies carried out with pharmacological inhibitors clearly predict that these signaling cascades integrate the effects of multiple extracellular signals and that elimination of even a single pathway in vivo would result in complex, difficult to interpret phenotypes.

MAPK signaling generally refers to four cascades, each defined by the final tier of the pathway: Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinases 1 & 2 (ERK1 & 2), ERK5, c-Jun N-terminal Kinases (JNK), and p38 (Raman et al., 2007). ERK1 and ERK2 (ERK1/2) exhibit a high degree of similarity and are considered functionally equivalent, although isoform specific effects have been described. In the nervous system, ERK1/2 and ERK5 are the primary MAPK cascades activated by trophic stimuli and have been shown to mediate proliferation, growth, and/or survival in specific contexts (Nishimoto and Nishida, 2006). Aberrant ERK1/2 signaling plays a primary role in a range of human syndromes that affect the nervous system, particularly the family of “neuro-cardio-facial-cutaneous” (NCFC) syndromes (Bentires-Alj et al., 2006). The precise role of ERK1/2 in the neurodevelopmental abnormalities that characterize these disorders is only now being investigated (Newbern et al., 2008; Samuels et al., 2008; Samuels et al., 2009). Indeed, most of our understanding of ERK function is derived from in vitro models in the context of isolated trophic stimuli. Such studies provide support for involvement of ERK/MAPK signaling in almost every aspect of neural development and function. However, the physiological relevance of many in vitro findings has not been adequately tested, and much less is known about ERK functions in the context of multiple extracellular signals, as occurs in vivo.

The PNS has been the standard model system for defining biological actions of many neurotrophic molecules. The PNS principally derives from the neural crest, which generates sensory and sympathetic neurons, satellite glia within the DRG, and Schwann cells within the peripheral nerve. Peripheral neuron development requires trophic signaling via Neurotrophins and GDNF family members, which act via RTKs that activate ERK1/2 (Marmigere and Ernfors, 2007). Analyses of PNS neuronal development in vitro have shown that ERK1/2 signaling is important for differentiation and neurite outgrowth in response to neurotrophins, other trophic factors, and ECM molecules (Atwal et al., 2000; Klesse et al., 1999; Kolkova et al., 2000; Markus et al., 2002). ERK1/2 activation by some of these same molecules has been implicated in regulating neurite outgrowth from motor neurons, which also extend axons in peripheral nerves (Soundararajan et al., 2010). Many trophic stimuli also activate ERK5, which appears to be involved in neuronal survival in the PNS, particularly in the context of NGF mediated retrograde signaling (Finegan et al., 2009; Watson et al., 2001). These findings plainly predict that disruption of either the ERK1/2 or ERK5 pathway in vivo would result in profound defects in neuronal differentiation, survival, and/or developmental axon growth.

Schwann cell development is also critically dependent on extracellular factors that act through RTKs, including neuregulins, PDGF, IGFs, FGFs, and ECM components (Jessen and Mirsky, 2005). These factors are capable of activating PI3K, PLC, ERK1/2, and ERK5 signaling (Lemmon and Schlessinger, 2010). However, the role of ERK5 in glia has not been assessed and the data regarding ERK1/2 function in Schwann cell development are controversial. ERK1/2 has been shown to regulate the survival of early Schwann cell progenitors (SCPs) and mature Schwann cells in vitro, however, other research has not supported these findings (Dong et al., 1999; Li et al., 2001; Parkinson et al., 2002). Some evidence suggests ERK1/2 signaling regulates Schwann cell myelination, yet other careful studies found little effect and argue that PI3K/Akt signaling plays a more central role (Harrisingh et al., 2004; Hu et al., 2006; Maurel and Salzer, 2000; Ogata et al., 2004). The reasons for these discrepancies are unclear and the precise role of ERK1/2 signaling in Schwann cell development remains unresolved.

Here, we have defined the roles of ERK1/2 and ERK5 in neuronal and glial development in vivo. In vivo analyses have previously been hampered by the strong redundancy between ERK1 and ERK2 and the early embryonic lethality of Erk2 and Erk5 knockouts (Nishimoto and Nishida, 2006). To circumvent these issues we have utilized a combination of Erk2 conditional and Erk1 null alleles to eliminate ERK1/2 signaling in vivo, and have generated an Erk5 conditional allele. We demonstrate that Erk1/2 and Erk5 are surprisingly dispensable for many aspects of prenatal DRG and motor neuron development in vivo, although Erk1/2 deletion in DRG neurons compromises sensory axon innervation in NGF-expressing target fields. In contrast, Erk1/2 signaling is essential at multiple stages of Schwann cell development and is required for PNS myelination. Our data constrain interpretation of the many prior in vitro studies and suggest tight linkage between ERK/MAPK functions in vivo and biological actions of specific RTK activating factors.

Results

ERK1/2, but not ERK5, deletion in the embryonic PNS results in DRG degeneration

To establish the role of ERK1/2 in embryonic PNS development, we generated Erk1-/- Erk2fl/fl Wnt1:Cre (hereafter referred to as Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1)) and Mek1fl/fl Mek2-/- Wnt1:Cre (Mek1/2CKO(Wnt1)) mice. The Wnt1:Cre driver induces recombination at ~E8.5 in pluripotent neural crest cells, which generate both neuronal and glial components of the PNS (Danielian et al., 1998). We have previously characterized major defects in craniofacial and cardiac neural crest derived structures by E10.5 and embryonic lethality between E18-19 in Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) and Mek1/2CKO(Wnt1) mice (Newbern et al., 2008). However, DRGs in E10.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos appear to be morphologically intact (Figure S1A-B). ERK1/2 expression is significantly reduced in the DRG by E10.5 and Western blotting of E12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) or Mek1/2CKO(Wnt1) DRG lysates shows a near complete loss of ERK1/2 or MEK1/2 protein, respectively (Figure S1C-E). RSK3, a downstream substrate of ERK1/2, showed significantly reduced phosphorylation further indicating functional inactivation of ERK1/2 signaling (Figure S1E).

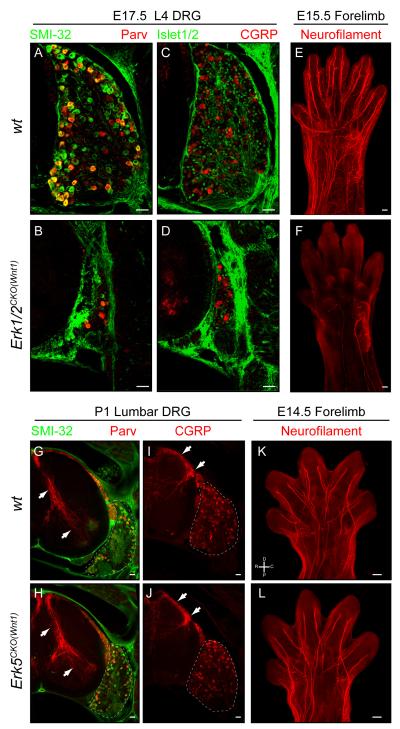

We therefore utilized Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) mice to ask whether the loss of Erk1/2 disrupts PNS development in vivo. Compared to controls (Figure 1A,C), massive cell loss was observed at both brachial and lumber levels in E17.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) DRG’s (Figure 1B,D;Figure S1F-J). We found that homozygous deletion of both genes was necessary for the decreased neuronal number in the DRG (data not shown). E17.5 Mek1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos show a qualitatively similar, though more severe phenotype, than in stage matched Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos (Figure S1F-H). Endogenous levels of MEK1/2 protein are reported to be lower than ERK1/2, likely resulting in more rapid protein clearance following recombination and a relatively accelerated phenotypic onset (Ferrell, 1996). Whole mount neurofilament immunolabeling of E15.5 control and Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) forelimbs revealed that nearly all peripheral projections are absent in mutant forelimbs (Figure 1E-F). It is notable that motor neurons do not undergo recombination in the Wnt1:Cre line, yet their projections totally degenerate. Overall, these data demonstrate that inactivation of Erk1/2 in the PNS results in the loss of all peripheral projections and massive DRG neuron death.

Figure 1. Deletion of Erk1/2, but not Erk5, in the PNS results in DRG neuron loss and the absence of all peripheral projections.

A-D. Compared to wild-type (A,C), E17.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) (B,D) L4 DRG cross sections revealed a massive decrease in DRG size as indicated by the gross morphology and decreased number of cells expressing neuronal markers. (Scale bar=50μM)

E-F. Whole mount neurofilament labeling of E15.5 control (E) and mutant (F) embryos revealed only sparse labeling in Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) forelimbs, demonstrating that both motor and sensory projections are absent. (Scale bar=100μM)

G-J. Analysis of the expression of Parvalbumin and CGRP in P1 control (G,I) and Erk5CKO(Wnt1) (H,J) lumbar DRG cross sections did not show any gross change in DRG sensory neurons or in central projections within the spinal cord (arrows). (Scale bar=50μM)

K-L. Whole mount neurofilament immunolabeling of E14.5 control (K) and Erk5CKO(Wnt1) (L) forelimbs showed no differences in peripheral axon growth. (Scale bar = 100 μm) (See also Figure S1)

ERK5 is another well-known stimulus dependent MAPK under trophic control during PNS development (Watson et al., 2001). We tested the role of this pathway in Erk5fl/fl Wnt1:Cre (Erk5CKO(Wnt1)) mice (Figure S1K-N). In contrast to Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) mice, Erk5CKO(Wnt1) mice are viable, and able to breed. However, Erk5CKO(Wnt1) adult mice are smaller than controls and exhibit external ear truncation and mandibular shortening, likely due to an alteration in the development of the craniofacial neural crest (Figure S1M). Perhaps surprisingly, markers for proprioceptive (Parvalbumin) and nociceptive (CGRP and TrkA) sensory neurons, exhibited relatively normal expression in P1 Erk5CKO(Wnt1) DRG’s (Figure 1G-J and data not shown). Whole mount neurofilament immunolabeling did not reveal any deficit in the peripheral projections of E14.5 Erk5CKO(Wnt1) forelimbs compared to controls (Figure 1K-L). Both CGRP and Parvalbumin positive central afferents within the spinal cord appeared intact as well (Figure 1G-J). Overall, these data suggest that ERK5 does not play a primary role in early aspects of PNS morphogenesis in vivo.

Erk1/2 is required for Schwann cell progenitor development

In order to determine the precise developmental defect underlying the massive decrease in DRG size observed in E17.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos, we assessed the expression of neuronal and glial markers at earlier stages of development. Within the DRG of E10.5-12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos, appropriate neuronal (neurofilament, NeuN, TrkA, Brn3a, Tau, and Islet1/2) markers are expressed (Figure 2A-D, 3;Figure S3), suggesting that early stages of neuronal specification are intact in these embryos. The pattern of two markers of glial differentiation, Sox2 and BFABP, within the DRG of E10.5-E12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos also appeared normal suggesting satellite glia are appropriately specified (Figure 2A-D, Figure S2C-D).

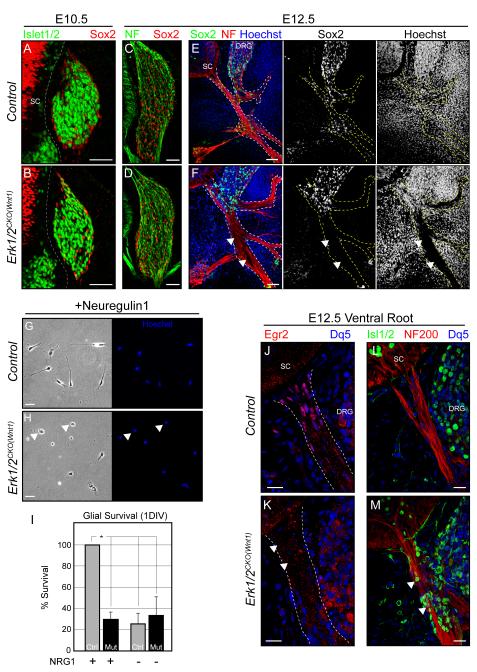

Figure 2. ERK1/2 is required for the development of SCPs in vivo and mediates neuregulin-1 signaling in vitro.

A-D. The expression of neuronal and glial markers is grossly normal within control (A,C) and Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) (B,D) brachial DRGs at E10.5 and E12.5.

E-F. Sox2 positive glial progenitors entering the neurofilament stained peripheral nerve are readily detectable in cross sections of the brachial region of E12.5 wildtype embryos (E). However, E12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos exhibit a near complete absence of glial progenitors in the peripheral nerve (F, arrowheads). (Scale bar=50μM)

G-I. Glial progenitors cultured from E11.5 control DRGs (G,I) can be sustained by Type III neuregulin-1 in vitro. The effect of neuregulin-1 on glial progenitor survival is essentially absent in Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) (H, I) cultures after 1 DIV (mean ± SEM, *=p<0.001). DNA staining revealed a large number of pyknotic, presumably dying glial progenitors in mutant cultures at this time point (arrowheads).

J-M. Egr2/Krox-20 immunolabeling labels the BC in the proximal segments of control (J) E12.5 peripheral nerves. Egr2/Krox-20 expressing cells are nearly absent in Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) (K) ventral roots (arrowheads). A number of Islet1/2 positive neurons are present within the ventral root and proximal peripheral nerve of E12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) (M) embryos (arrowheads). (See also Figure S2)

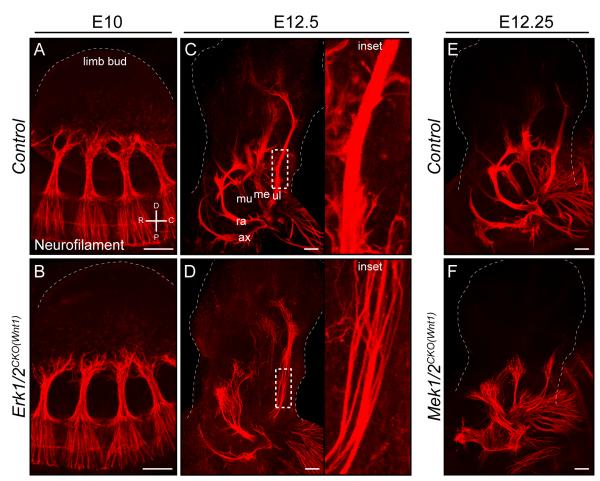

Figure 3. Axons extend normally following Erk1/2 or Mek1/2 inactivation in the PNS but are defasciculated.

A-D. Whole mount neurofilament immunolabeling was utilized to examine peripheral nerve outgrowth in the forelimb. Compared to littermate controls (A,C), Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) (B,D) embryos demonstrated a normal extent of axon outgrowth up to E12.5, however, the mutant nerves were defasciculated (inset in D).

E-F. Similar results were obtained in E12.25 Mek1/2CKO(Wnt1) (F) embryos. (Scale bar= 100μM, ax=axillary n., ra=radial n., mu=musculocutaneous n., me=median n., ul=ulnar n.) (See also Figure S3)

In striking contrast, we noted a marked loss of Sox2 and BFABP labeled Schwann cell progenitors (SCPs) within the peripheral nerve of E11.5-12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos (Figure 2E-F, Figure S2A-D). Generic labeling of all cells with Hoechst (Figure 2E-F) or Rosa26LacZ (Figure S2E-F) shows a similar pattern demonstrating loss of cells rather than changes in the expression levels of these specific glial markers. These data indicate that ERK1/2 is required for SCP colonization of the peripheral nerve in vivo.

SCPs are heavily reliant upon neuregulin/ErbB signaling; a potent activator of the ERK1/2 pathway (Birchmeier and Nave, 2008). Mice lacking Nrg1, ErbB2, or ErbB3 exhibit an absence of SCPs in the developing nerve (Birchmeier and Nave, 2008). Nrg-1 or ErbB2 gene expression was not decreased in E12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) DRGs (Figure S2G). We tested whether the disruption of SCP development was due to a glial cell autonomous requirement for ERK1/2 in neuregulin/ErbB signaling. Glial progenitors from E11.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) DRGs were cultured in the presence of neuregulin-1. The loss of Erk1/2 clearly abolished the survival promoting effect of neuregulin-1 in vitro (Figure 2G-I). These data indicate that ERK1/2 is required for glial responses to neuregulin-1, which likely contributes to the failure of SCP development in vivo.

It has been previously shown that the neural crest derived, boundary cap (BC) generates SCPs and establishes ECM boundaries that prevent the migration of neuronal cell bodies into the peripheral nerve (Bron et al., 2007; Maro et al., 2004). We examined this gliogenic niche in Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos by immunostaining for Egr2/Krox-20, which is expressed by the BC. Interestingly, the proximal ventral root of E12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos exhibited a near complete absence of Egr2/Krox-20 expressing BC cells (Figure 2J-K). We also noted Islet1/2 positive neuronal bodies in the ventral root of E11.5-12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos, further indicating a failure in function (Figure 2L-M). Overall, these data suggest that the defect in SCP development is due in part to a disruption in a gliogenic niche.

Initial stages of sensory axon outgrowth do not require Erk1/2

A key consequence of the loss of SCPs in Nrg-1/ErbB mutant mice is nerve defasciculation, loss of all peripheral projections, and neuron death (Meyer and Birchmeier, 1995; Morris et al., 1999; Riethmacher et al., 1997). Indeed, the absence of SCPs likely contributes to the complete loss of motor projections in E15.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos, since recombination in motor neurons is not induced by Wnt1:Cre (Figure 1E-F). However, the ERK1/2 signaling pathway plays a central role in the response to numerous axon growth promoting stimuli. We predicted that DRG neuron outgrowth in Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos would be disrupted, prior to the point when the loss of SCPs would effect neuronal development. Thus, we examined the temporal dynamics of axon outgrowth and DRG neuron number in Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos.

We first examined changes in neuron number in these embryos. At E11.5, when SCP number in the peripheral nerve is reduced, no pyknotic nuclei were detected in the DRG. By E12.5, occasional pyknotic nuclei and increased caspase-3 activity were detected in Erk1/2CKO(Wnt) rostral DRGs (Figure S3A-B,F). However, relative counts of Islet1/2 positive neurons in brachial DRGs at E12.5 did not reveal a statistically significant difference (Figure S3E). We examined neuronal number with a Tauloxp-STOP-loxp-mGFP-IRES-nlsLacZ (TauSTOP) reporter line in E15.5 mutants and found only 19.6±4.1% of nls-LacZ expressing neurons remained (Hippenmeyer et al., 2005)(Figure S3C-E). The time course of neuronal death closely mirrors that reported in ErbB-2 or -3 null mice (Morris et al., 1999; Riethmacher et al., 1997). Thus, neurogenesis is relatively unaffected by the loss Erk1/2, however, neuronal death is initiated after E12.5, likely an indirect effect resulting from disruption of the SCP pool.

The pattern of early peripheral nerve growth in Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos was evaluated with whole mount neurofilament immunolabeling, which labels all peripheral projections of sensory, motor, or sympathetic origin. In contrast to our predictions, the extent of initial axonal outgrowth in Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos appeared normal at E10.5 and E12.5 (Figure 3A-D). At E12.5, nerves were disorganized and defasciculated in the forelimb, similar to what has been observed in Nrg-1/ErbB mutant mice (Figure 3C-D). Comparable results were obtained with Mek1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos (Figure 3E-F), though again deficits appeared slightly earlier when compared to Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos. A specific defect in sensory neuron outgrowth could be masked by neurofilament expression in motor axons. This possibility was excluded by analyzing two sensory neuron specific reporter lines, the TauSTOP reporter line, which does not label motor neurons in Wnt1:Cre mice, and the Brn3aTauLacZ mouse (Eng et al., 2001; Hippenmeyer et al., 2005). Both reporter lines revealed that sensory neuron outgrowth in E12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos is of relatively normal extent, but defasciculated (Figure S3G-J). In summary, these data indicate that in the absence of ERK1/2, neuronal number and the extent of axon outgrowth are intact up to E12.5. Following this stage a number of neuronal defects are evident, which are consistent with the loss of SCPs in this model, namely, defasciculation, the overt loss of all peripheral projections, and sensory neuron death.

Erk1/2 is required for NGF-dependent cutaneous innervation

The requirement of SCPs for ERK1/2 and the potential for complex neuron-glial interactions in the context of neural crest Erk1/2 deletion, limited our analysis of neuronal roles for ERK1/2 signaling. To better understand neuronal ERK1/2, we employed two additional Cre lines. Nestin:Cre induces recombination in progenitors throughout the CNS and leads to gene deletion in both neuronal and glial populations. However, recombination in the DRG occurs beginning at ~E10.5 resulting in gene deletion in most DRG neurons, but not in Schwann cells (Kao et al., 2009; Tronche et al., 1999; Zhong et al., 2007). The Advillin:Cre line induces recombination in virtually all DRG and trigeminal ganglion neurons beginning at ~E12.5 and is almost exclusive for these populations (Hasegawa et al., 2007).

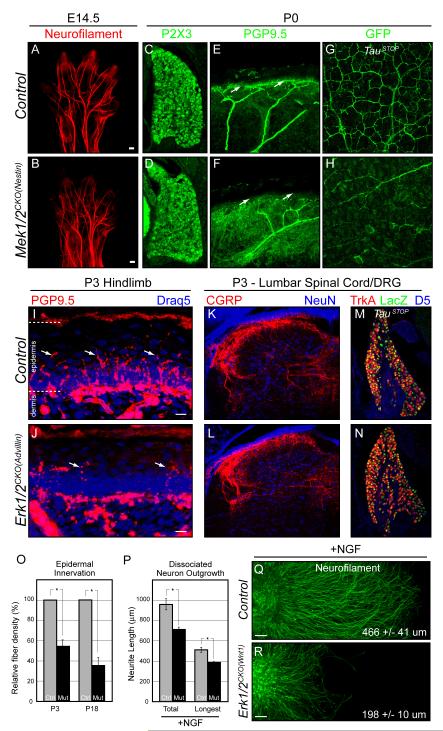

Mek1/2CKO(Nes) mice die shortly after birth and major reductions in MEK1/2 expression and ERK1/2 activation were noted in the Mek1/2CKO(Nes) DRG by E14 (Figure S4A). Whole mount neurofilament labeling at mid-embryonic stages revealed a normal pattern of early peripheral nerve development in the absence of Mek1/2 (Figure 4A-B). DRG morphology is grossly normal at birth and the expression of nociceptive markers, P2×3 and TrkA, and the proprioceptive marker, Parvalbumin, are relatively unchanged (Figure 4C-D and data not shown). In the target field, the main nerve trunks of P0 Mek1/2CKO(Nes) peripheral nerves were relatively normal in size, however, we noted a reduction in the innervation of the subepidermal plexus and the number of cutaneous fibers entering the epidermal field (Figure 4E-H). These data show that the early loss of ERK1/2 signaling in DRG neurons does not modify initial stages of axon outgrowth, but inhibits axon innervation of the cutaneous fields by birth.

Figure 4. Neuron specific deletion of Erk1/2 or Mek1/2 does not alter initial axon extension, but disrupts NGF dependent cutaneous innervation.

A-B. Compared to littermate controls (A), E14.5 Mek1/2CKO(Nestin) (B) forelimbs exhibit normal growth of major peripheral nerve trunks as detected by whole mount neurofilament immunolabeling.

C-D. P0 DRGs in Mek1/2CKO(Nestin) (D) mice appear morphologically similar to controls (C) and exhibit relatively normal expression of the nociceptive marker P2×3.

E-H. Compared to controls (E,G), cutaneous innervation is reduced in P0 Mek1/2CKO(Nestin) (F,H) mice. PGP9.5 labeling of cross sections from P0 forepaws show a reduction in cutaneous afferents in the epidermis of mutant (F) mice. Whole mount GFP immunolabeling of skin derived from the trunk of P0 TauSTOP controls (G) in flat mount readily labels the subepidermal plexus. Mek1/2CKO(Nestin) (H) mice exhibit significant reductions in innervation.

I-O. Relative to controls (I), a significant and persistent reduction in the number of PGP9.5 labeled epidermal afferents was detected in the hindlimb of P3 Erk1/2CKO(Advillin) (J) mice, which is quantitated in O (mean ± SEM, *=p<0.001). However, CGRP labeled central afferents in the dorsal spinal cord (K-L) and the number of sensory neurons in the DRG were not significantly altered in the P3 Erk1/2CKO(Advillin) dorsal spinal cord (M-N).

P-R. DRG neurons from E11.5 control and Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos were either dissociated (P) or explanted (Q-R), cultured in the presence of NGF, and stained with neurofilament after 2DIV. In dissociated cultures, the length of the total and longest neurites demonstrated a significant decrease in both parameters in Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) neurons (P) (mean ± SEM, n = >100 neurons in each condition from three independent cultures, *=p<0.001). Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) explants exhibited a significant reduction (p < 0.001) in the extent of NGF induced neuronal outgrowth. The average hemidiameter length ± SEM of >20 explants from three independent cultures is reported. (See also Figure S4)

Erk1/2CKO(Advillin) mice are indistinguishable from controls in the days following birth. However, by the end of the first postnatal week, mutant mice are noticeably smaller and the mice do not survive past three weeks of age. Importantly, the number of fibers innervating the epidermis in P3 Erk1/2CKO(Advillin) hindlimbs was significantly decreased relative to controls (Figure 4I-J,O). At this time point, a relatively normal number of DRG neurons were present, which exhibit a typical pattern of TrkA and CGRP expression and complete loss of ERK2 expression (Figure 4M-N, data not shown). CGRP labeled central afferents also appeared intact in the dorsal spinal cord of mutant mice (Figure 4K-L). In P18 mutants, DRG neuron number was 41.5±3.0% (n=2) of littermate controls. This is likely an indirect phenotype related to the decrease in cutaneous innervation, which diminishes trophic support. Taken together, these data demonstrate that DRG neuron specific inactivation of ERK1/2 signaling is not necessary for initial stages of axon outgrowth in vivo but is required for superficial cutaneous innervation.

Arborization within superficial cutaneous target fields is known to be dependent upon NGF/TrkA signaling (Patel et al., 2000). The link between ERK1/2 and NGF was further assessed in vitro. Indeed, both dissociated and explanted DRG neurons from Erk1/2CKO(Wnt) and Mek1/2CKO(Nes) embryos exhibit decreased axon outgrowth in response to NGF (Figure 4P-R and data not shown). Thus, the deficit in cutaneous innervation observed in vivo is likely mediated by a disruption of NGF/TrkA signaling.

Though cutaneous innervation was clearly deficient, various aspects of proprioceptive morphological development appeared qualitatively normal in P3 Erk1/2CKO(Advillin) mice, including central projections into the spinal cord, and the innervation of muscle spindles within the soleus (Figure S4E-L). However, these finding should be interpreted with caution as the proprioceptive system develops relatively early related to the recombination induced by Advillin:Cre. Indeed, the mice develop an abnormality of spindle innervation and exhibit a hindlimb clasping phenotype when raised by the tail beginning in the second postnatal week (Figure S4B-D). These findings suggest that ERK/MAPK signaling is required for some aspects of proprioceptive development, possibly downstream of NT-3.

The ERK1/2 and ERK5 signaling pathways have been shown to modify similar substrates (Nishimoto and Nishida, 2006). Thus, compensatory interactions between ERK1/2 and ERK5 might mask a requirement for the other pathway in Erk1/2 or Erk5 mutants. In order to test whether Erk1/2 and Erk5 exhibit compensatory interactions in DRG neurons, we generated Erk1-/- Erk2fl/fl Erk5fl/fl Advillin:Cre mice. The added deletion of Erk5 does not appear to strongly modify the Erk1/2 deletion phenotypes. Thus, Erk1/2/5 triple mutants exhibit a hindlimb clasping phenotype and die at the same postnatal ages as Erk1/2 double mutants. These data suggest that the ERK1/2 and ERK5 pathways do not significantly compensate for one another during DRG neuron development.

Peripheral myelination requires Erk1/2 signaling

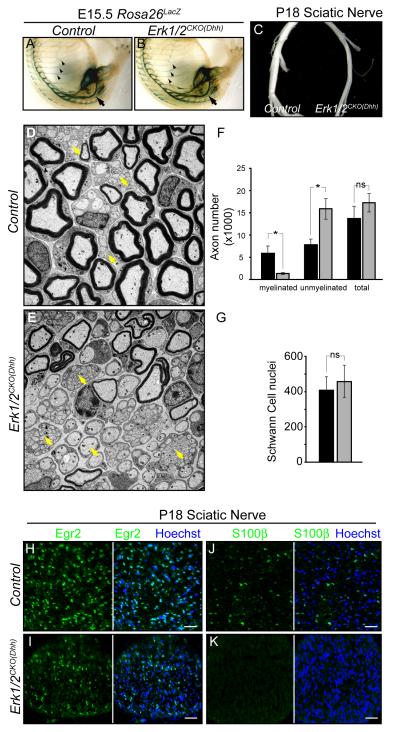

The effects of ERK1/2 on the establishment of the SCP pool precluded analyses of later stages of Schwann cell development, particularly myelination. To this end, we utilized the Desert hedgehog:Cre knockin mouse, which induces recombination at ~E13, almost exclusively in the Schwann cell lineage (Jaegle et al., 2003). Loss of ERK1/2 occurs after the specification of the SCP pool and during the transition into immature Schwann cells (Jessen and Mirsky, 2005). Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) mice were born at normal Mendelian ratios, but exhibited tremor and hindlimb paresis within two weeks of birth and do not survive past the fourth postnatal week. Western blotting of mutant P1 sciatic nerve lysates revealed a significant decrease in the expression of ERK1/2 (Figure S5A). Whole mount LacZ staining of control embryos crossed with Rosa26LacZ demonstrates recombination within the proximal peripheral nerve by E13.5 and most of the sciatic nerve by E14.5 (data not shown). E15.5 Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) Rosa26LacZ embryos showed a morphologically similar pattern of recombination and peripheral nerve patterning as littermate controls (Figure 5A-B). The distribution of Schwann cells in the mature, P20 Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) Z/EG phrenic nerve projections appeared similar to controls, with Schwann cells present up to the NMJ (Figure S5B-C). These finding suggest Schwann cells take up relatively normal positions in Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) embryos.

Figure 5. Schwann cell specific Erk1/2 inactivation results in hypomyelination.

A-B. Whole mount LacZ staining of the trunk and hindlimb of E15.5 control (A) and Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) (B) mice crossed with Rosa26LacZ show a similar pattern of staining in the peripheral nerve, including the intercostal (arrowheads) and sciatic (arrows) nerve.

C. Upon gross dissection, the sciatic nerves of P18 Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) mice were noticeably smaller in diameter and more transparent than control nerves.

D-G. EM analysis of P18 sciatic nerve cross sections from control (D) and Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) (E) mice show a dramatic reduction in the number of myelinated axons and an increase in unmyelinated axons (yellow arrows) in mutant mice. The total number of axons and Schwann cell nuclei in the nerve was not changed (F,G). (mean ± SEM, *=p<0.01)

H-K. Immunolabeling for markers of myelinating Schwann cell differentiation, Egr2/Krox-20 (H-I) and S100β (J-K), was performed in P18 control and Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) sciatic nerve cross-sections. A decrease in the number of Egr2/Krox-20 positive cells and a massive reduction in S100β labeling were found in mutant nerves. Note the decreased nerve caliber in mutants. Since Schwann cell number is not altered, the density of nuclei is increased. (See also Figure S5)

Although Schwann cells appeared to be present within the nerve, gross dissection of P18, Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) sciatic nerves revealed markedly decreased nerve caliber and increased translucency (Figure 5C). Electron microscopy revealed a clear, striking reduction in the number of myelinated axons and an increase in the number of un-myelinated axons in Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) mice (Figure 5D-F). There was no change in the number of Schwann cell nuclei within the sciatic nerve and dying, pyknotic nuclei were not detected at this stage (Figure 5G). These data show that loss of ERK1/2 in Schwann cell progenitors clearly inhibits myelination.

The development of myelinating Schwann cells involves the upregulation of numerous factors, including Egr2/Krox-20, S100β, and various myelin components (Jessen and Mirsky, 2005). Immunohistochemical analysis of P18 Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) sciatic nerves revealed a 77.8±8.1% decrease in the number of Egr2/Krox-20 positive cells and the expression of S100β was nearly absent (Figure 5H-K). GFAP immunolabeling of non-myelinating Schwann cells appeared normal at this stage (data not shown). These findings suggest that ERK1/2 is required for the progression of the myelinating Schwann cell lineage after initial specification.

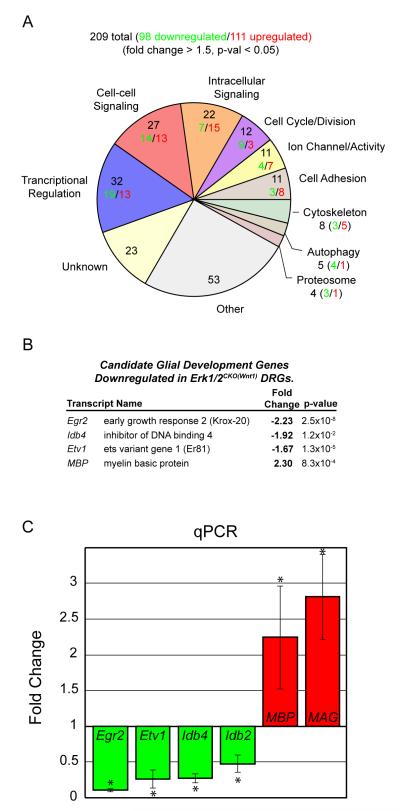

ERK1/2 regulates a transcriptional network critical to Schwann cell development

In order to better understand the potentially diverse developmental mechanisms underlying ERK1/2 regulation of PNS development, we performed microarray analysis on RNA extracts derived from E12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) and wildtype DRG’s. We did not detect overt changes in DRG neuron number at this developmental stage, suggesting the profile is a reflection of ERK1/2 regulated genes and not the loss of any particular cell type. 209 distinct genes met our inclusion criteria, which included 98 down-regulated and 111 up-regulated genes in Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) samples (Figure 6A, Figure S6). Functional annotation of regulated genes revealed significant changes in mediators of transcriptional regulation, cell-cell signaling, intracellular signaling, and cell-cycle/division (Figure 6A, Figure S6).

Figure 6. ERK1/2 regulates the expression of genes important for Schwann cell progenitor development and myelination.

A. 209 genes met the criteria for differential expression in RNA samples derived from E12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) DRGs. The pie chart summarizes the major functional categories represented by the differentially expressed genes and the number downregulated (green) and upregulated (red) within each category.

B. Candidate genes with known roles in glial development are differentially expressed in the DRG of Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1)embryos.

C. qPCR analysis of E12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) DRG samples validated the decrease in the expression of transcription factors thought to regulate glial development. Interestingly, the myelin components, MBP and MAG, show increased expression in mutant DRGs. (n = 4, * = p-value <0.05) (See also Figure S6)

A number of genes involved in transcriptional regulation were modified that have been shown to regulate glial development (Figure 6B). Microarray changes were validated by qPCR of DRG samples from E12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos (Figure 6C and data not shown). Significantly decreased expression was observed for Egr2/Krox-20, Id4, Id2, and Etv1/Er81, all of which have been shown to be required for or modify myelinating glia differentiation (Marin-Husstege et al., 2006; Topilko et al., 1994). Surprisingly, mutant DRGs exhibited increased mRNA levels of the myelin components, MBP and MAG. The increase in MBP and MAG suggest that the loss of ERK1/2 signaling may have triggered, in part, a molecular program of premature differentiation.

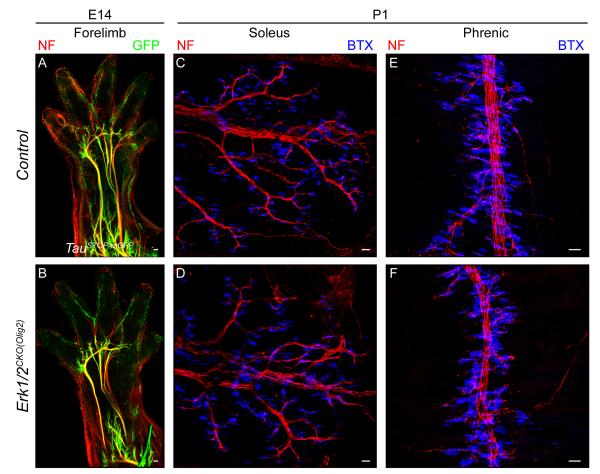

Requirement for Erk1/2 in motor neuron and oligodendrocyte development

In order to explore ERK1/2 regulation of another class of peripherally projecting neuron and to assess regulation of another type of myelinating cell, we utilized an Olig2:Cre mouse to induce recombination by E9.5 in the spinal cord progenitor domain that produces motor neurons and oligodendrocytes (Dessaud et al., 2007; Novitch et al., 2001). We first examined the development of spinal motor neurons. Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) mice do not survive past the first day of birth. Cre dependent reporter line expression and a decrease in ERK1/2 expression were noted in E14.5 motor neurons and the progenitor domain from which they arise (Figure 7A-B, Figure S7A-B). Whole mount immunolabeling of the E14.5 mutant forelimbs revealed a normal pattern of motor neuron outgrowth (Figure 7A-B). Motor innervation of neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) in the soleus and diaphragm also appeared intact in P1 Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) mice (Figure 7C-F). Thus, motor neuron axon development does not appear to be at all dependent on ERK1/2 signaling during embryonic development.

Figure 7. Spinal motor neuron peripheral innervation is not regulated by ERK1/2 signaling.

A-B. Whole mount immunostaining of E14.5 TauSTOP forelimbs from control (A) and Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) (B) embryos did not reveal any difference in the initial growth of motor neuron peripheral projections.

C-F. The pattern of motor innervation of NMJs in the P1 soleus (C-D) and diaphragm (E-F) was not altered in Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) (D,F) embryos relative to controls (C,E). (See also Figure S7)

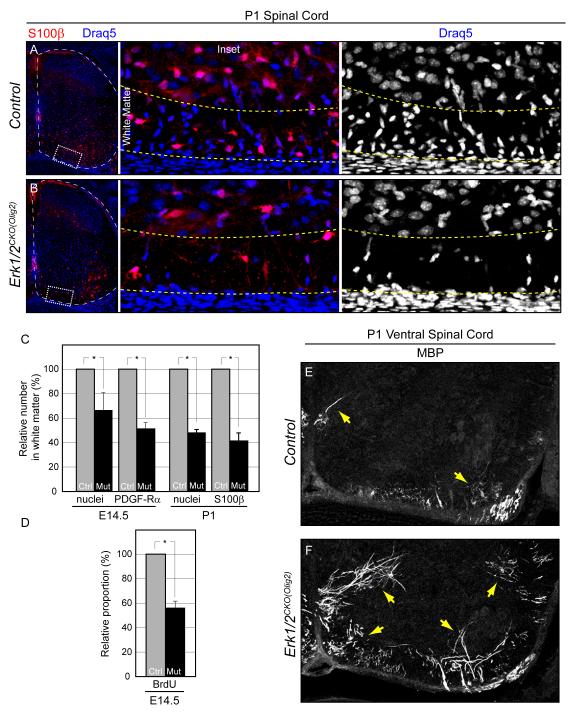

Given the profound effects on peripheral glial following the loss Erk1/2 we analyzed the development of oligodendrocytes within the spinal cord of Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) mice. A significant decrease in the number of oligodendrocyte progenitors in the spinal cord white matter was evident by E14.5. Quantification in the white matter at E14.5 revealed that 51.1±4.9% of PDGF-Rα positive cells remained in the mutants while the number of S100β positive cells at P1 was 41.2±6.5% of controls (Figure 8A-C and Figure S8A-B). The total number of nuclei in the white matter was similarly decreased in Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) embryos indicating that the defect is not due to altered expression of glial markers (Figure 8A-C). The number of oligodendrocytes thus appears to be regulated by ERK1/2 signaling in vivo.

Figure 8. ERK1/2 signaling is necessary for oligodendrocyte precursor proliferation, but is not required for myelination.

A-B. Relative to controls (A) the number of oligodendrocytes in the spinal cord ventral white matter of P1 Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) (B) embryos is strongly reduced.

C-D. Quantification of the relative decrease in the number of nuclei and labeled oligodendrocytes in E14.5 and P1 Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) white matter (C). The proportion of BrdU labeled oligodendrocytes is significantly decreased in Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) E14.5 embryos (D). (mean ± SEM, *=p<0.01)

E-F. At P1, MBP immunolabeling indicates that myelination has just initiated in a small proportion of oligodendrocytes in the ventral spinal cord of control mice (E) (arrows). In Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) (F) littermates, there is a significant increase in the number of oligodendrocytes that express MBP (E) (arrows). (See also Figure S8)

Oligodendrocyte proliferation in vivo is strongly regulated by PDGF acting through the receptor tyrosine kinase, PDGF-Rα, a known ERK1/2 activator (Calver et al., 1998). In exploring the mechanism underlying the reduction in white matter glia, we noted a significant decrease in the proportion of PDGF-Rα cells co-labeled with BrdU in E14.5 Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) white matter (Figure 8D). In contrast, we did not detect changes in activated caspase-3 expression in the embryonic spinal cord (data not shown). Together these results suggest that ERK1/2 is critical for the proliferation, but not the survival of oligodendrocyte progenitors.

In striking contrast to ERK1/2 regulation of the Schwann cell lineage, Erk1/2 deleted oligodendrocytes were capable of myelination. The early lethality of Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) mice limited our analysis to only the initial stages of myelination, however, a clear increase in MBP labeling is apparent in P1 Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) ventral spinal cords (Figure 8E-F). S100β labeled oligodendrocytes in the white matter of mutant embryos exhibited a more ramified, complex morphology than controls, further suggesting that loss of Erk1/2 triggered premature differentiation (Figure 8A-B, data not shown). Co-immunostaining of MBP positive cells with an ERK2 antibody confirmed that myelinating oligodendrocytes were truly ERK1/2 deficient in mutants (Figure S8C-D). These data show that, in contrast to Schwann cells, myelination by oligodendrocytes can proceed in the absence of Erk1/2.

Discussion

We have assessed the functions of ERK1/2 and ERK5 in distinct cell types during PNS development in vivo. Our data lead to several clear conclusions. First, many aspects of embryonic sensory and motor neuron development occur normally in the setting of Erk1/2 deletion, although sensory axons do not invade NGF-expressing target fields. Second, ERK5 does not appear to strongly regulate embryonic PNS development. Third, ERK1/2 is critical for fundamental aspects of Schwann cell development. Erk1/2 deletion phenotypes resemble those of Nrg-1 and ErbB mutants, and Erk1/2 deleted Schwann cell progenitors do not respond to neuregulin-1. Finally, the requirement of ERK1/2 for myelination is specific to Schwann cells, as myelination by oligodendrocytes can proceed in the absence of Erk1/2. Overall, our findings tightly link in vivo functions of ERK/MAPK signaling to biological actions of specific RTK activating factors.

ERK/MAPK signaling is dispensable for many aspects of PNS neuron development

Gene targeting studies have defined roles for numerous trophic factors, ECM molecules, and axon guidance cues in directing PNS neuron development (Marmigere and Ernfors, 2007). However, the signaling pathways mediating these effects in vivo have not been defined. Many growth promoting cues appear to converge upon ERK1/2, and combinations of trophic stimuli, such as integrins and growth factors, trigger synergistic ERK1/2 activation (Perron and Bixby, 1999). Overall, these data predict that ERK1/2 is a central regulator of neuronal morphology and development in vivo.

In spite of a wealth of in vitro data, our in vivo findings provide surprisingly little support for a broad and essential role for ERK1/2 for the acquisition of neuronal phenotypes, survival, or initial axon outgrowth. Our results instead show that ERK1/2 signaling is required for NGF-mediated cutaneous sensory neuron innervation at late embryonic and early postnatal stages. These results are generally consistent with previous findings in B-Raf/C-Raf and SRF conditional knockout mice (Wickramasinghe et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 2007) and in line with the established role for NGF/TrkA signaling in promoting the formation and maintenance of these afferents (Patel et al., 2000). The peripheral nerve defect is not as severe as that reported in TrkA/Bax mutant mice, suggesting a contribution to morphological development by other pathways, such as PI3K and PLC (Patel et al., 2000). Overall, our results establish that ERK1/2 signaling in vivo is required to transduce the morphological effects of skin derived NGF. However, neuronal ERK/MAPK signaling is surprisingly dispensable for early phases of neuronal differentiation, neuronal survival, long range axon growth, and formation of the neuromuscular junction.

Another surprise relates to the apparently limited role of ERK5. ERK5 has been convincingly established as a retrograde survival signal for NGF-stimulated DRG and sympathetic ganglion neurons in vitro (Finegan et al., 2009; Watson et al., 2001). The reason for the discrepancy between in vitro and in vivo findings related to ERK5 mediated survival functions remains elusive. ERK5 and ERK1/2 exhibit some overlap in downstream targets, opening the possibility of a compensatory interaction. However, the drastically different phenotypes and mechanisms leading to lethality in Erk2-/- vs. Erk5-/- embryos demonstrate that ERK1/2 and ERK5 possess many unique, independent functions (Nishimoto and Nishida, 2006). Our results with Erk1-/- Erk2fl/fl Erk5fl/fl Advillin:Cre mutants suggests that compensatory interactions between these two cascades are minimal in sensory neurons.

ERK1/2 mediates effects of neuregulin-1 on Schwann cell development

Although numerous extracellular factors that activate ERK1/2 are known to regulate Schwann cell development, the requirement for ERK1/2 signaling in mediating Schwann cell responses has been controversial. Instead the PI3K/Akt pathway appears to play a particularly prominent role (Harrisingh et al., 2004; Hu et al., 2006; Li et al., 2001; Maurel and Salzer, 2000; Ogata et al., 2004). An important caveat is that much of this prior work regarding ERK1/2 signaling has relied upon varying in vitro models, likely contributing to disparate conclusions. Our data help resolve a long-standing debate in establishing that ERK1/2 is absolutely necessary for multiple stages of Schwann cell development in vivo.

The neuregulin/ErbB axis is critical for Schwann cell development (Birchmeier and Nave, 2008). The signaling pathways required to mediate neuregulin functions have been of intense interest, particularly in relation to the control of myelination (Grossmann et al., 2009;; Kao et al., 2009;). Our data, taken together with other lines of evidence, strongly suggest that ERK1/2 is a key signaling pathway necessary to transduce effects of neuregulin-1 on Schwann cells in vivo. The phenotypes in Erk1/2 and Nrg-1/ErbB mutant mice are remarkably similar. The Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) mice that we report here, and ErbB2-/-, ErbB3-/-, and NRG-1-/- mice previously reported, all exhibit a near complete absence of SCPs in the peripheral nerve by E12.5, yet satellite glia appear to be relatively unaffected (Meyer and Birchmeier, 1995; Morris et al., 1999; Riethmacher et al., 1997; Woldeyesus et al., 1999). The loss of SCPs in developing peripheral nerve results in axon defasciculation, the subsequent loss of all peripheral axon projections, and neuronal death, a phenotype observed in other mouse models lacking SCPs, such as Sox10-/- (Britsch et al., 2001). Inhibition of Schwann cell myelination is also present in both Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) and conditional ErbB mutant mice, where gene inactivation occurs after SCP’s have been specified in immature Schwann cells (Garratt et al., 2000). Inactivation of Shp2, an ERK1/2 pathway activator recruited by ErbB, results in similar disruptions in Schwann cell development (Grossmann et al., 2009). Indeed, the defects in Shp2 mutant Schwann cells in vitro correlated with decreased sustained ERK1/2, but not PI3K/Akt, activity (Grossmann et al., 2009). Finally, we demonstrate here that loss of ERK1/2 in glial progenitors blocks the effects of neuregulin-1 in vitro. These data establish that ERK1/2 is necessary to transduce neuregulin-1/ErbB signals during the development of the Schwann cell lineage in vivo.

Mechanisms and specificity of the ERK1/2 requirement for myelination

The precise mechanisms underlying the failed development of Schwann cells in Erk1/2 mutant mice are likely complex given the extensive repertoire of ERK1/2 substrates and downstream targets (Yoon and Seger, 2006). The loss of the gliogenic boundary cap in Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) mice presumably leads to a reduction in SCPs in the peripheral nerve. This phenotype may result from a direct defect in survival as demonstrated in vitro, but may also involve aberrant differentiation. Expression profiling of early glial progenitors in the Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) DRG demonstrates that ERK1/2 promotes the expression of Id2 and Id4, genes that maintain pluripotency and regulate glial differentiation (Marin-Husstege et al., 2006). Additionally, ERK1/2 signaling suppresses the expression of markers of mature glia, MBP and MAG. One interpretation of these data is that loss of Erk1/2 leads to premature differentiation. Thus, SCPs or the BC may have lost the ability to maintain the progenitor state, which contributes to their loss in Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos. Interestingly, Erk1/2 deletion at a later stage of Schwann cell development with Dhh:Cre did not result in a significant change in Schwann cell number in the sciatic nerves. This stage dependent difference in the regulation of Schwann cell development mirrors the increasingly limited effects of ErbB2 deletion as development proceeds (Atanasoski et al., 2006; Garratt et al., 2000), and presumably results from an uncoupling of ERK1/2 from specific cellular functions.

How is it that ERK1/2 regulates myelination? Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) peripheral nerves fail to express markers of mature Schwann cells, such as S100β, and myelination is severely inhibited. ERK1/2 regulation of Egr2/Krox-20 might underlie this Schwann cell specific phenotype. Egr2/Krox-20 is a critical gene for promoting Schwann cell myelination and is mutated in a subset of patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease (Topilko et al., 1994; Warner et al., 1998). Mice expressing CMT-related, Egr2/Krox-20 mutations exhibit hypomyelination and a temporal progression of behavioral dysfunction and death that closely phenocopies the Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) mice we report here (Baloh et al., 2009). In vitro evidence demonstrates that Egr2/Krox-20 induction is downstream of ERK1/2 and neuregulin signaling (Murphy et al., 1996; Parkinson et al., 2002). Our findings suggest this interaction is relevant in vivo as Egr2/Krox-20 expression is strongly reduced in Erk1/2 mutant mice.

An important and surprising finding is that the cellular mechanisms regulated by ERK1/2 vary depending on the type of myelinating glia. We demonstrate that Erk1/2 deletion strongly reduces oligodendrocyte progenitor proliferation. It is well established that oligodendrocyte progenitor proliferation is regulated by PDGF in vivo (Calver et al., 1998). PDGF acts through the RTK, PDGF-Rα and we hypothesize that in oligodendrocytes, PDGF effects on proliferation require ERK1/2 signaling. Interestingly, some oligodendrocytes were generated and indeed initiated the expression of MBP earlier than controls and expressed markers of mature oligodendrocytes. The premature differentiation observed in Erk1/2 deleted oligodendrocytes is consistent with data showing that oligodendrocyte differentiation requires a down-regulation of PDGF-Rα, and a down-regulation of ERK1/2 activity (Chew et al., 2010; Dugas et al., 2010). Thus, in contrast to Schwann cells, Erk1/2 deleted oligodendrocytes are able to myelinate axons. The conditional ablation of the ERK1/2 upstream regulator, B-Raf, has been reported to result in a strong reduction in the number of myelinated fibers in the postnatal brain (Galabova-Kovacs et al., 2008). However, ERK1/2 activation was not completely abolished in these mice due to compensation by other Raf family members and the connection between oligodendrocyte precursor proliferation and the number of myelinated fibers was not clearly drawn.

ERK/MAPK functions are linked to specific RTK systems

Evidence from numerous in vitro systems has suggested that ERK1/2 is activated or functionally required in response to a very wide range of extracellular cues, including netrins, semaphorins, GPCR’s, trophic factors, hormones, and ECM molecules (Raman et al., 2007). Thus, we might have predicted that early Erk1/2 deletion in the developing nervous system would lead to drastic phenotypes that reflect the inhibition of nearly all receptor systems. Instead, our findings suggest ERK1/2 mediates effects of specific RTKs in vivo, including invasion of cutaneous target fields (NGF/TrkA), Schwann cell development (Neuregulin/ErbB), and oligodendrocyte proliferation (PDGF/PDGF-Rα). Although this initial analysis is of necessity superficial and many subtle roles for ERK1/2 signaling in vivo will certainly be uncovered, our results do suggest caution in interpreting in vitro results. At the very least, our work suggests that the ability to induce transient ERK1/2 activation or block cellular functions pharmacologically in a strongly reduced in vitro system is not a strong predictor of the biological requirement for ERK/MAPK signaling in vivo.

Implications for human neurodevelopmental syndromes

Aberrant ERK1/2 signaling plays a primary role in a range of human syndromes that affect the nervous system, particularly the family of “neuro-cardio-facial-cutaneous” (NCFC) syndromes (Bentires-Alj et al., 2006; Samuels et al., 2009). We have previously demonstrated that ERK1/2 signaling is a critical regulator of neural crest contributions to craniofacial and great vessel development helping to explain the pathogenesis of these disorders (Newbern et al., 2008). The NCFC spectrum includes neurofibromatosis (NF), which exhibits an increased propensity to peripheral nerve tumors of Schwann cell precursor origin. Importantly, NF type 1 is caused by mutations in the Ras-GAP, neurofibromin, which leads to increased signaling through the ERK1/2 pathway. Our data demonstrating a requirement for ERK/MAPK signaling at multiple stages of Schwann cell development are consistent with abnormalities in the intricate balance between differentiation and proliferation that leads to tumors in these patients.

Experimental Procedures

Mutant mice

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by IACUC at UNCCH. Erk1-/- mice possess a neo insertion in exons 1 through 6 (Nekrasova et al., 2005). Erk2fl/fl mice contain loxp sites around exon 3 (Samuels et al., 2008). Mek1fl/fl mice possess a loxp flanked exon 3 while Mek2-/- mice contain a neo insertion in exons 4-6 and were kindly provided by Dr. J. Charron (Belanger et al., 2003; Bissonauth et al., 2006). The Wnt1:Cre and Nestin:Cre mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. The Dhh:Cre mouse was generously provided by Dr. D. Meijer and the Olig2:Cre mouse by Dr. T. Jessell. For the Erk5 floxed allele, a targeting vector was generated based on an Erk5 fragment derived from a 129sv genomic BAC library and incorporated loxp sites around Exon 3 (Figure S1K-L). All mice were of mixed genetic background. For BrdU injections, timed pregnant dams were injected at E14.5 with 75 mg/kg BrdU and sacrificed 4 hours later. For timed breedings, the appearance of a vaginal plug was considered to be E0.5 on the day of detection. All experiments were replicated at least three times with mice derived from independent litters. Cre expressing littermates were utilized as control embryos for most experiments. Further detail regarding the Erk5 floxed mouse and genotyping is listed in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed according to a standard protocol outlined in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. The primary antibodies used were anti-phospho or pan ERK1/2, anti-ERK5, anti-phospho-RSK3, anti-cleaved Caspase-3, anti-MEK1/2, and anti-GAPDH (all from Cell Signaling Technologies).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraformaldehyde fixed, cryopreserved specimens were immunostained according to standard procedures and imaged with a Zeiss LSM 510 NLO confocal microscope. Further detail regarding immunohistochemistry, primary antibodies, whole mount staining, and counting methods are described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Electron Microscopy

Mice were anesthetized and perfused with 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer. A 2-3 mm section of the sciatic nerve, proximal to the division into the cutaneous and tibial nerve, was dissected, rinsed, and postfixed overnight at 4°C and prepared for EM as described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Tissue Culture

Embryonic DRG’s were cultured as previously described with minor modifications (Markus et al., 2002) as described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

RNA Extraction and Analysis

E12.5 DRGs from control and Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos derived from three independent litters were dissected in PBS supplemented with 10% RNAlater (Qiagen) and frozen on dry ice. Total RNA was extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen) and a Qiagen RNeasy Mini kit per manufacturer’s instructions. RNA samples for were assayed for quality and quantity with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. Total RNA was amplified, labeled, and hybridized on Illumina arrays (MouseRef-8 V2 Expression BeadChip, Illumina). Slides were processed and scanned in an Illumina BeadStation platform according to the manufacturer protocol. Data was further processed using quantile normalization. Log2ratios and p values are calculated in R from a Bayesian moderated t-test using the LIMMA package. Regulated transcripts were defined by a greater than 1.5 fold change and a p-value less than 0.05. Functional annotation of differentially expressed genes was obtained through the use of The Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base (Ingenuity Systems, http://www.ingenuity.com), The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov), the Gene Ontology Project (http://www.geneontology.org), and extensive literature review. Further detail regarding qPCR is listed in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Highlights.

Erk1/2 is dispensable for much of embryonic sensory and motor neuron development.

Erk5 is largely dispensable for PNS neuronal and glial development.

Erk1/2 mediates neuregulin-1 effects on Schwann cell development.

Erk1/2 is required for myelination by Schwann cells, but not oligodendrocytes

Supplementary Material

Figure S1, related to Figure 1. Conditional deletion of Erk1/2 and Mek1/2, but not Erk5, in the PNS results in DRG degeneration.

A-B. Compared to E10.5 Wnt1:Cre Rosa26lacZ controls (A), whole mount LacZ staining of Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) Rosa26lacZ (B) embryos exhibit significant defects in craniofacial neural crest derived tissues, particularly the branchial arches and frontonasal mass (arrows), while the DRG (arrowheads) appears to be intact.

C-D. ERK2 immunofluorescent labeling of E10.5 control (C) and mutant (D) spinal cords reveal a significant loss of ERK2 expression in the Wnt1:Cre expression domain including the DRG (arrow) and dorsal spinal cord (arrowhead).

E. Western blots of DRG whole protein lysates derived from E12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) embryos show absence of ERK1 and significantly reduced expression of ERK2 as well as a reduction in phospho-RSK3, a downstream ERK1/2 substrate, when compared to wld-type or Erk1-/- control samples. Quantification of densitometry results from four independent trials resulted in an 89.23±3.2% (p<.001) reduction in ERK2 expression. Similar results were obtained when E12.5 Mek1/2CKO(Wnt1) and Mek2-/- DRG samples were compared.

F-J. H&E stained brachial spinal cord cross sections derived from E17 wild-type (F), Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) (G), and Mek1/2CKO(Wnt1) (H) embryos revealed an almost complete absence of the DRG in mutant embryos. Cresyl violet stained L4 spinal cord sections derived from the E17.5 wild-type (I) and Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) (J) show significant degeneration as well, albeit, to a lesser degree than in brachial DRGs at the same stage.

K. A restriction map of the Erk5 gene including extragenic regions and the targeting vector design. Exons are indicated as solid black rectangles. The vector expresses a neomycin phosphotransferase (neo) and a diphtheria toxin A gene (DT). The two FRT sites anchored the two selection genes that were deleted by Flpe recombination in ES cell. Two loxP sites were inserted around Exon 3 of Erk5.

L. Restriction enzymes used to prepare fragments for Southern analysis of genomic DNA from four ES colonies are shown. The genomic probe target is indicated. Southern blotting identified targeted ES cell colonies (first three lanes) expressing both a 10kb wildtype and 7.3 kb modified Erk5 allele.

M. Erk5CKO(Wnt1) mice are noticeably smaller than control littermates and exhibit craniofacial malformations, including mandibular shortening and external ear defects.

N. ERK5 expression in E12.5 DRG lysates is significantly reduced in Erk5CKO(Wnt1) samples.

Figure S2, related to Figure 2. Glial progenitors require ERK1/2 signaling to colonize the peripheral nerve.

A-B. Analysis of the peripheral nerve of E11.5 control (A) and Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) (B) embryos demonstrated a decrease in the number of SCPs.

C-D. Compared to E12.5 controls (C), Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) (D) embryos exhibit BFABP labeled glial progenitors within the DRG, but not in the developing peripheral nerve. In the distal peripheral nerve of control embryos, BFABP positive cells are clearly associated with neurofilament labeled axons (arrows, inset in C). In mutants, defasciculated axons are apparent, but no BFABP staining is seen (arrows, inset in D).

E-F. Generic labeling of all neural crest derivatives was achieved by whole mount staining E12.5 Wnt1:Cre Rosa26LacZ control (E) and mutant (F) forelimbs. LacZ staining was essentially absent in the distal peripheral nerve of mutant embryos (arrows), further demonstrating that neural crest derived progenitors fail to populate the developing peripheral nerve. (Scale bar=50μM)

G. Analysis of E12.5 Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) DRG samples did not reveal a significant relative decrease in Nrg1 and ErbB2 gene expression as assessed by RT-PCR.

Figure S3, related to Figure 3. Prior to the effects of SCP loss, ERK1/2 signaling does not alter sensory neuron number or the extent of outgrowth.

A-F. The number of sensory neurons in wild-type (A,C) and Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) (B,D) DRGs was assessed by counting the number of Islet1/2 labeled cells at E12.5 and LacZ labeled cells in embryos crossed with the TauSTOP reporter line at E15.5. E12.5 is the earliest stage that pyknotic nuclei could be detected in Hoechst stained mutant DRGs (inset in B, arrowheads). Quantification of neuronal counts at E12.5 show a non-significant reduction in mutant embryos (p=.081), while counts at E15.5 show significant neuron loss (* = p-value < 0.001, n=3) (E). Western blots of E12.5 DRG lysates show an increase in activated caspase-3 expression when compared to controls (F).

G-H. The TauSTOP reporter line will express mGFP in sensory and sympathetic projections when crossed with the Wnt1:Cre driver. Forelimbs from E13 control (Erk1-/-Erk2fl/wtWnt1:Cre TauSTOP) (G) and Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) TauSTOP (H) embryos were immunolabeled with GFP and Neurofilament antibodies in whole mount. GFP labeled projections can be detected at the tips of developing nerves as depicted in magnified images of the ulnar nerve.

I-J. The Brn3aTau-LacZ mouse drives the expression of a Tau-LacZ fusion protein specifically in sensory neurons. While whole mount lacZ staining in these mice does not label peripheral nerves to the same extent as immunolabeling methods, sensory neuron outgrowth between E12.5 control (I) and Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) (J) embryos appears similar, however, defasciculation can still be detected (arrows).

Figure S4, related to Figure 4. Neuronal specific deletion of MEK/ERK signaling inhibits NGF dependent cutaneous innervation, but not proprioceptive innervation of muscle spindles in vivo.

A. Mek1/2CKO(Nestin) mice exhibit significant reductions in MEK1/2 expression and near complete inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in both spinal cord and DRG lysates derived from E14.5 mutant embryos.

B-D. Erk1/2CKO(Advillin) mice are smaller relative to controls at P16 (B). Further, mutant mice (D) exhibit a clasping phenotype when raised by the tail.

E-L. Both P3 control (E) and Erk1/2CKO(Advillin) (F) L3 DRGs exhibit a normal pattern of expression of the proprioceptive sensory neuron marker Parvalbumin. Central proprioceptive afferents into the spinal cord also appeared intact (G-H). Proprioceptive peripheral innervation of soleus muscle spindles labeled with the pan-axonal marker, PGP9.5, did not appear significantly different from controls in P3 mutant mice (I-J), but by P18, spindle innervation in mutant mice appeared significantly disrupted (K-L).

Figure S5, related to Figure 5. Schwann cell specific Erk1/2 inactivation results in hypomyelination.

A. P1 Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) sciatic nerve lysates exhibit decreased expression of ERK2.

B-C. Schwann cells labeled with a Cre dependent reporter line (Z/EG) were detected adjacent to NMJ’s at the very tip of phrenic nerve projections into the diaphragm in P20 control (B) and Erk1/2CKO(Dhh) (C) mice.

Figure S6, related to Figure 6. Differentially expressed genes in the DRG of control vs. Erk1/2CKO(Wnt1) mice.

The expression level of each gene is given in log2ratio and its percentile within each condition. Differential expression is provided as the difference in log2ratio (control-mutant) and also transformed into fold-increase. Genes are listed in ascending order based on fold difference. The second table lists the functional annotation of differentially expressed genes in mutant DRGs.

Figure S7, related to Figure 7. ERK1/2 signaling is not required for spinal motor neuron development.

A. E14.5 control (A) and Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) (B) spinal cords were labeled with the motor neuron marker, Islet1/2, and ERK2. Note the lack of ERK2 expression in the progenitor domain from which motor neurons and oligodendrocytes arise (arrows) as well as in the motor neurons within the lateral motor column (outlined).

Figure S8, related to Figure 8. Oligodendrocyte proliferation and the timing of myelination require Erk1/2.

A-B. Analysis of oligodendrocyte number in the white matter labeled with PDGF-Rα or nuclear markers revealed a decrease in E14.5 Erk1/2CKO(Olig2) (B) spinal cords compared to controls.

C-D. P1 MBP positive oligodendrocytes in the ventral spinal cord of control (C) and mutant (D) mice were co-labeled ERK2. ERK2 expression is indeed significantly reduced in mutant oligodendrocytes expressing MBP.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to D. Meijer, T. Jessell, and J. Charron for providing transgenic mice; Ben Novitch, Barbara Han, and Monica Mendelsohn for the generation of the Olig2:Cre line in the laboratory of T. Jessell; T. Müller and C. Birchmeier for the generous gift of the BFABP antibody and helpful advice; E. Anton and J. Weimer for kindly providing antibodies and guidance; Dr. Louis Reichardt for kindly providing the TrkA antibody; and A. McKell and L. Goins for assistance with mouse breeding and genotyping. This work is supported by NIH grant NS031768 to WDS; NSF grant IBN97–23147 to GEL; and a NRSA award F32NS061591 to JMN. Generation of mice and imaging were supported by Cores 3 and 5 respectively of NINDS Center Grant P30 NS04892.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Atanasoski S, Scherer SS, Sirkowski E, Leone D, Garratt AN, Birchmeier C, Suter U. ErbB2 signaling in Schwann cells is mostly dispensable for maintenance of myelinated peripheral nerves and proliferation of adult Schwann cells after injury. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2124–2131. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4594-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwal JK, Massie B, Miller FD, Kaplan DR. The TrkB-Shc site signals neuronal survival and local axon growth via MEK and P13-kinase. Neuron. 2000;27:265–277. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloh RH, Strickland A, Ryu E, Le N, Fahrner T, Yang M, Nagarajan R, Milbrandt J. Congenital hypomyelinating neuropathy with lethal conduction failure in mice carrying the Egr2 I268N mutation. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2312–2321. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2168-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belanger L-F, Roy S, Tremblay M, Brott B, Steff A-M, Mourad W, Hugo P, Erikson R, Charron J. Mek2 Is Dispensable for Mouse Growth and Development. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4778–4787. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.4778-4787.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentires-Alj M, Kontaridis MI, Neel BG. Stops along the RAS pathway in human genetic disease. Nat Med. 2006;12:283–285. doi: 10.1038/nm0306-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchmeier C, Nave KA. Neuregulin-1, a key axonal signal that drives Schwann cell growth and differentiation. Glia. 2008;56:1491–1497. doi: 10.1002/glia.20753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissonauth V, Roy S, Gravel M, Guillemette S, Charron J. Requirement for Map2k1 (Mek1) in extra-embryonic ectoderm during placentogenesis. Development. 2006;133:3429–3440. doi: 10.1242/dev.02526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britsch S, Goerich DE, Riethmacher D, Peirano RI, Rossner M, Nave KA, Birchmeier C, Wegner M. The transcription factor Sox10 is a key regulator of peripheral glial development. Genes Dev. 2001;15:66–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.186601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bron R, Vermeren M, Kokot N, Andrews W, Little GE, Mitchell KJ, Cohen J. Boundary cap cells constrain spinal motor neuron somal migration at motor exit points by a semaphorin-plexin mechanism. Neural Dev. 2007;2:21. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-2-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calver AR, Hall AC, Yu WP, Walsh FS, Heath JK, Betsholtz C, Richardson WD. Oligodendrocyte population dynamics and the role of PDGF in vivo. Neuron. 1998;20:869–882. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80469-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew L-J, Coley W, Cheng Y, Gallo V. Mechanisms of Regulation of Oligodendrocyte Development by p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11011–11027. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2546-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielian PS, Muccino D, Rowitch DH, Michael SK, McMahon AP. Modification of gene activity in mouse embryos in utero by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre recombinase. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1323–1326. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00562-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessaud E, Yang LL, Hill K, Cox B, Ulloa F, Ribeiro A, Mynett A, Novitch BG, Briscoe J. Interpretation of the sonic hedgehog morphogen gradient by a temporal adaptation mechanism. Nature. 2007;450:717–720. doi: 10.1038/nature06347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Sinanan A, Parkinson D, Parmantier E, Mirsky R, Jessen KR. Schwann cell development in embryonic mouse nerves. J Neurosci Res. 1999;56:334–348. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990515)56:4<334::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas JC, Cuellar TL, Scholze A, Ason B, Ibrahim A, Emery B, Zamanian JL, Foo LC, McManus MT, Barres BA. Dicer1 and miR-219 Are required for normal oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. Neuron. 2010;65:597–611. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng SR, Gratwick K, Rhee JM, Fedtsova N, Gan L, Turner EE. Defects in sensory axon growth precede neuronal death in Brn3a-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2001;21:541–549. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00541.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell JE., Jr. Tripping the switch fantastic: how a protein kinase cascade can convert graded inputs into switch-like outputs. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:460–466. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)20026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finegan KG, Wang X, Lee EJ, Robinson AC, Tournier C. Regulation of neuronal survival by the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 5. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:674–683. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galabova-Kovacs G, Catalanotti F, Matzen D, Reyes GX, Zezula J, Herbst R, Silva A, Walter I, Baccarini M. Essential role of B-Raf in oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination during postnatal central nervous system development. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:947–955. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garratt AN, Voiculescu O, Topilko P, Charnay P, Birchmeier C. A dual role of erbB2 in myelination and in expansion of the schwann cell precursor pool. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:1035–1046. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.5.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann KS, Wende H, Paul FE, Cheret C, Garratt AN, Zurborg S, Feinberg K, Besser D, Schulz H, Peles E, et al. The tyrosine phosphatase Shp2 (PTPN11) directs Neuregulin-1/ErbB signaling throughout Schwann cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16704–16709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904336106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrisingh MC, Perez-Nadales E, Parkinson DB, Malcolm DS, Mudge AW, Lloyd AC. The Ras/Raf/ERK signalling pathway drives Schwann cell dedifferentiation. Embo J. 2004;23:3061–3071. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa H, Abbott S, Han BX, Qi Y, Wang F. Analyzing somatosensory axon projections with the sensory neuron-specific Advillin gene. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14404–14414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4908-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hippenmeyer S, Vrieseling E, Sigrist M, Portmann T, Laengle C, Ladle DR, Arber S. A developmental switch in the response of DRG neurons to ETS transcription factor signaling. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Hicks CW, He W, Wong P, Macklin WB, Trapp BD, Yan R. Bace1 modulates myelination in the central and peripheral nervous system. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1520–1525. doi: 10.1038/nn1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaegle M, Ghazvini M, Mandemakers W, Piirsoo M, Driegen S, Levavasseur F, Raghoenath S, Grosveld F, Meijer D. The POU proteins Brn-2 and Oct-6 share important functions in Schwann cell development. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1380–1391. doi: 10.1101/gad.258203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen KR, Mirsky R. The origin and development of glial cells in peripheral nerves. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:671–682. doi: 10.1038/nrn1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao SC, Wu H, Xie J, Chang CP, Ranish JA, Graef IA, Crabtree GR. Calcineurin/NFAT signaling is required for neuregulin-regulated Schwann cell differentiation. Science. 2009;323:651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.1166562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klesse LJ, Meyers KA, Marshall CJ, Parada LF. Nerve growth factor induces survival and differentiation through two distinct signaling cascades in PC12 cells. Oncogene. 1999;18:2055–2068. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolkova K, Novitskaya V, Pedersen N, Berezin V, Bock E. Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule-Stimulated Neurite Outgrowth Depends on Activation of Protein Kinase C and the Ras-Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathway. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2238–2246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-06-02238.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2010;141:1117–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Tennekoon GI, Birnbaum M, Marchionni MA, Rutkowski JL. Neuregulin signaling through a PI3K/Akt/Bad pathway in Schwann cell survival. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;17:761–767. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Husstege M, He Y, Li J, Kondo T, Sablitzky F, Casaccia-Bonnefil P. Multiple roles of Id4 in developmental myelination: predicted outcomes and unexpected findings. Glia. 2006;54:285–296. doi: 10.1002/glia.20385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus A, Zhong J, Snider WD. Raf and akt mediate distinct aspects of sensory axon growth. Neuron. 2002;35:65–76. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00752-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmigere F, Ernfors P. Specification and connectivity of neuronal subtypes in the sensory lineage. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:114–127. doi: 10.1038/nrn2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maro GS, Vermeren M, Voiculescu O, Melton L, Cohen J, Charnay P, Topilko P. Neural crest boundary cap cells constitute a source of neuronal and glial cells of the PNS. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:930–938. doi: 10.1038/nn1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel P, Salzer JL. Axonal regulation of Schwann cell proliferation and survival and the initial events of myelination requires PI 3-kinase activity. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4635–4645. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04635.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D, Birchmeier C. Multiple essential functions of neuregulin in development. Nature. 1995;378:386–390. doi: 10.1038/378386a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JK, Lin W, Hauser C, Marchuk Y, Getman D, Lee KF. Rescue of the cardiac defect in ErbB2 mutant mice reveals essential roles of ErbB2 in peripheral nervous system development. Neuron. 1999;23:273–283. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80779-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy P, Topilko P, Schneider-Maunoury S, Seitanidou T, Baron-Van Evercooren A, Charnay P. The regulation of Krox-20 expression reveals important steps in the control of peripheral glial cell development. Development. 1996;122:2847–2857. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekrasova T, Shive C, Gao Y, Kawamura K, Guardia R, Landreth G, Forsthuber TG. ERK1-Deficient Mice Show Normal T Cell Effector Function and Are Highly Susceptible to Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2005;175:2374–2380. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbern J, Zhong J, Wickramasinghe RS, Li X, Wu Y, Samuels I, Cherosky N, Karlo JC, O’Loughlin B, Wikenheiser J, et al. Mouse and human phenotypes indicate a critical conserved role for ERK2 signaling in neural crest development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17115–17120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805239105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto S, Nishida E. MAPK signalling: ERK5 versus ERK1/2. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:782–786. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novitch BG, Chen AI, Jessell TM. Coordinate regulation of motor neuron subtype identity and pan-neuronal properties by the bHLH repressor Olig2. Neuron. 2001;31:773–789. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00407-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata T, Iijima S, Hoshikawa S, Miura T, Yamamoto S, Oda H, Nakamura K, Tanaka S. Opposing extracellular signal-regulated kinase and Akt pathways control Schwann cell myelination. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6724–6732. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5520-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson DB, Langner K, Namini SS, Jessen KR, Mirsky R. beta-Neuregulin and autocrine mediated survival of Schwann cells requires activity of Ets family transcription factors. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20:154–167. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel TD, Jackman A, Rice FL, Kucera J, Snider WD. Development of sensory neurons in the absence of NGF/TrkA signaling in vivo. Neuron. 2000;25:345–357. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80899-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron JC, Bixby JL. Distinct neurite outgrowth signaling pathways converge on ERK activation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;13:362–378. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman M, Chen W, Cobb MH. Differential regulation and properties of MAPKs. Oncogene. 2007;26:3100–3112. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riethmacher D, Sonnenberg-Riethmacher E, Brinkmann V, Yamaai T, Lewin GR, Birchmeier C. Severe neuropathies in mice with targeted mutations in the ErbB3 receptor. Nature. 1997;389:725–730. doi: 10.1038/39593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels IS, Karlo JC, Faruzzi AN, Pickering K, Herrup K, Sweatt JD, Saitta SC, Landreth GE. Deletion of ERK2 mitogen-activated protein kinase identifies its key roles in cortical neurogenesis and cognitive function. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6983–6995. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0679-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels IS, Saitta SC, Landreth GE. MAP’ing CNS development and cognition: an ERKsome process. Neuron. 2009;61:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soundararajan P, Fawcett JP, Rafuse VF. Guidance of postural motoneurons requires MAPK/ERK signaling downstream of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6595–6606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4932-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topilko P, Schneider-Maunoury S, Levi G, Baron-Van Evercooren A, Chennoufi AB, Seitanidou T, Babinet C, Charnay P. Krox-20 controls myelination in the peripheral nervous system. Nature. 1994;371:796–799. doi: 10.1038/371796a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronche F, Kellendonk C, Kretz O, Gass P, Anlag K, Orban PC, Bock R, Klein R, Schutz G. Disruption of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in the nervous system results in reduced anxiety. Nat Genet. 1999;23:99–103. doi: 10.1038/12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]