Abstract

DNA marker-assisted selection appears to be a promising strategy for improving rates of leaf photosynthesis in rice. The rate of leaf photosynthesis was significantly higher in a high-yielding indica variety, Habataki, than in the most popular Japanese variety, Koshihikari, at the full heading stage as a result of the higher level of leaf nitrogen at the same rate of application of nitrogen and the higher stomatal conductance even when the respective levels of leaf nitrogen were the same. The higher leaf nitrogen content of Habataki was caused by the greater accumulation of nitrogen by plants. The higher stomatal conductance of Habataki was caused by the higher hydraulic conductance. Using progeny populations and selected lines derived from a cross between Koshihikari and Habataki, it was possible to identify the genomic regions responsible for the rate of photosynthesis within a 2.1 Mb region between RM17459 and RM17552 and within a 1.2 Mb region between RM6999 and RM22529 on the long arm of chromosome 4 and on the short arm of chromosome 8, respectively. The designated region on chromosome 4 of Habataki was responsible for both the increase in the nitrogen content of leaves and hydraulic conductance in the plant by increasing the root surface area. The designated region on chromosome 8 of Habataki was responsible for the increase in hydraulic conductance by increasing the root hydraulic conductivity. The results suggest that it may be possible to improve photosynthesis in rice leaves by marker-assisted selection that focuses on these regions of chromosomes 4 and 8.

Keywords: Hydraulic conductance, hydraulic conductivity, leaf water potential, nitrogen content, photosynthetic rate, quantitative trait locus, rice, root surface area, stomatal conductance, water stress

Introduction

Increases in rates of leaf photosynthesis are important if the yield potential of rice (Oryza sativa L.) is to be increased since the rates of photosynthesis of the individual leaves affect dry matter production via photosynthesis within the canopy (Long et al., 2006; Murchie et al., 2009). The rate of single-leaf photosynthesis can be categorized in terms of three parameters. One is the rate of photosynthesis, which is measured at full leaf expansion under saturating light, the ambient atmospheric concentration of CO2, an optimum temperature, and a low vapour pressure deficit, and it will be referred to here as the rate of maximum photosynthesis (Murata, 1961; Makino et al., 1988). A second parameter is the extent of the midday and afternoon depression of the rate of photosynthesis that results from abiotic stresses, such as water stress (Hirasawa and Ishihara, 1992; Ishihara, 1995; Hirasawa and Hsiao, 1999). The third parameter is the reduction in the rate of photosynthesis that accompanies senescence (Makino et al., 1984; Jiang et al., 1999).

The present study focused on the rate of maximum photosynthesis. The activity of Rubisco limits photosynthesis at lower intercellular concentrations of CO2 (Ci; Farquhar et al., 1980; Makino et al., 1985). As Ci increases, the electron transport capacity of the photosynthetic machinery limits photosynthesis (Farquhar et al., 1980). In addition, at higher values of Ci, the availability of inorganic phosphate also contributes to the limitation of photosynthesis (Sharkey, 1985). In rice leaves, the photosynthesis is limited by Rubisco content at ambient atmospheric concentration of CO2 (Makino et al., 1985). In turn, the Rubisco content of each leaf is closely correlated with the leaf nitrogen content (Makino et al., 1984; Evans, 1989).

There are several reports of comparisons of rates of photosynthesis in individual leaves (Ishii, 1995), among varieties of japonica rice (Murata, 1961; Sasaki and Ishii, 1992; Ishii, 1995; Osada, 1995), and among varieties including indica and japonica rice and other species of Oryza (Takano and Tsunoda, 1971; Cook and Evans, 1983; Yeo et al., 1994; Osada, 1995; Xu et al., 1997; Masumoto et al., 2004). Some significant differences among varieties, within species of Oryza, and among progeny plants derived from crosses between species were described. Plant breeding that was directed against lodging has enhanced rates of leaf photosynthesis by increasing the nitrogen content of leaves under conditions of heavy nitrogen application (Osada, 1995). On the other hand, Makino et al. (1987) reported that differences in the Michaelis constant (CO2) and maximum initial velocity per milligram of protein in the carboxylase reaction of Rubisco and in the ratio of Rubisco protein to total soluble protein were very small among cultivars of japonica, indica, indica×japonica, and javanica types. It was also reported that there was barely any difference in terms of the relationship between the nitrogen and the Rubisco content of leaves among several japonica and indica varieties (Hirasawa et al., 2010).

Varietal differences in stomatal conductance, which regulates the supply of CO2 from the air to the interior of the leaf, have often been observed (Maruyama and Tajima, 1990; Ohsumi et al., 2007) and, thus, stomatal conductance might be an important factor in the varietal differences among rates of photosynthesis (Ohsumi et al., 2007). However, since stomatal conductance is influenced not only by hydraulic conductance (Hirasawa et al., 1992b; Holbrook, 2006; Hopkins and Huner, 2008) but also by leaf nitrogen content (Ishihara, 1995; Makino et al., 1988), it is important to analyse the effects of nitrogen on these varietal differences in rates of photosynthesis; however, little attention has been paid to these effects to date. It was demonstrated previously that the rate of photosynthesis was higher in the indica variety Takanari at the same rate of nitrogen application than in japonica varieties, but the rate in Takanari was also higher even when levels of leaf nitrogen were the same, as a result of the higher stomatal conductance of Takanari (Hirasawa et al., 2010).

Since the measurements of photosynthesis have been time consuming and labour intensive, leaf photosynthesis has not been considered as a selection objective in plant breeding. Various DNA markers have been developed in rice, whose entire genome has been sequenced (Sasaki, 2003; International Rice Genome Sequencing Project, 2005), and new mapping populations, such as chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSLs) or backcrossed inbred lines (BILs), have been developed for genetic analysis (Yano, 2001; Ebitani et al., 2005; Yamamoto et al., 2009). In addition, as a consequence of improvements in the quantitation of photosynthesis, it is now possible to reduce measurement times while maintaining accuracy in the field. Therefore, it is now possible to conduct research programmes that are aimed at improving leaf photosynthesis genetically. Quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for leaf photosynthetic rate have been identified in sunflower (Herve et al., 2001) and in rice (Teng et al., 2004). However, information about QTLs for leaf photosynthesis is very limited and, therefore, no near-isogenic lines (NILs) to analyse genetic effects in detail are available. The limited information might be a consequence of the minimal variations in rates of photosynthesis among the parental varieties used for genetic analysis and inadequate understanding of the factors that contribute to differences in photosynthetic rate. If it was possible to evaluate differences in rates of photosynthesis and identify the traits that contribute to an elevated rate of photosynthesis among parental varieties, the newly developed methods and plant materials for genetic analysis could be exploited and available varieties of rice could be improved.

A high-yielding indica variety, Habataki, has 1.3- to 1.4-fold higher rates of maximum photosynthesis than a commercial japonica variety, Sasanishiki, from booting to the early ripening stage (Asanuma et al., 2008). In a previous study, the approximate chromosomal regions that determine leaf photosynthetic rate were localized on chromosomes 4, 5, 8, and 11 using CSSLs derived from Sasanishiki and Habataki (Nito et al., 2007a, b). It was also found that the same regions on chromosomes 4 and 8 showed a larger hydraulic conductance (Asanuma et al., 2007). The eventual goal of the present research is the improvement of the rate of leaf photosynthesis in the high-quality Japanese rice variety Koshihikari, which is currently the most widely farmed rice variety in Japan, by introgression of the chromosome segments of Habataki. However, the differences in the rate of photosynthesis and its related traits between Koshihikari and Habataki have not been determined. In addition to this, it is unclear whether the chromosomal regions of Habataki detected by Nito et al. (2007a, b) will increase the rate of leaf photosynthesis of Koshihikari or not. Populations were developed for genetic analysis with a focus on the regions of chromosome 4 and 8, where both the rates of leaf photosynthesis and hydraulic conductance were large among CSSLs from Sasanishiki and Habataki (Nito et al., 2007a, b; Asanuma et al., 2007). It was confirmed that these regions could increase the rate of photosynthesis in Koshihikari, the precise locations of the regions were determined, and then these regions were characterized based on analysis of the traits responsible for the differences in photosynthetic rate between Koshihikari and Habataki.

Materials and methods

Cultivation of rice plants

Rice plants of the japonica cultivar Koshihikari, the indica cultivar Habataki, and the mapping populations mentioned below were grown in the paddy field of the University Farm (35°41'N, 139°29'E). Seedlings at the fourth-leaf stage were transplanted to the paddy field in alluvial soil (clay loam) at a rate of 22.2 hills m−2 (spacing, 30 cm×15 cm) with one plant per hill. As a basal dressing, manure was applied at a rate of ∼15 t ha−1 and chemical fertilizer was applied at a rate of 30, 60, and 60 kg ha−1 for N, P2O5, and K2O, respectively. One-third of the total nitrogen was applied as nitrogen sulphate; one-third as LP-50 elution-controlled urea (Chisso Asahi Fertilizer, Tokyo); and one third as LPS-100 elution-controlled urea (Chisso Asahi Fertilizer). No topdressing was applied. Nitrogen was also applied at several different rates to Koshihikari and Habataki to change the levels of leaf nitrogen at the booting stage. The experiments were designed with five randomly arranged replicates.

Rice plants were also grown in 3.0 l pots that were filled with a mixture of paddy soil and Kanto diluvial soil (1:1, v/v) in a growth chamber (Koitotron, Koito Manufacturing Co. Ltd, Tokyo) or outdoors. Environmental conditions in the growth chamber were maintained at a day/night temperature of 28 °C/23 °C, a relative humidity of 60%/80%, a 12 h photoperiod, and a photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) at the top of the canopy of ∼1000 μmol m−2 s−1. Basal fertilizer was applied to the plants grown in a growth chamber at a rate of 0.5, 0.5, and 0.5 g per pot for N, P2O5, and K2O, respectively, and 0.1 g per pot for N was applied to Koshihikari 10 d before measurements, depending on the reading of a chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502, Konica-Minolta, Tokyo), to bring the leaf nitrogen content of Koshihikari to the same as that of Habataki. Basal fertilizer was applied to the plants grown outdoors at a rate of 0.1, 0.5, and 0.5 g per pot for N, P2O5, and K2O, respectively, and additional fertilizer was applied at a rate of 0.3 g of nitrogen per pot at the booting stage.

Rates of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance of individual leaves

The rate of photosynthesis (Pn) and the stomatal conductance (gs) of the flag leaf were measured with portable gas-exchange systems (LI-6400 and LI-6200; LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) at the full heading stage. The ambient CO2 concentration in the leaf chamber of LI-6400 was kept at 370 μl l−1, the PPFD was 2000 μmol m−2 s−1, the leaf to air vapour pressure difference was 1.5–1.8 kPa on average, and the leaf temperature was 28 °C (for plants in the growth chamber) and 30 °C (for plants in the field) during measurements. Pn was also measured at different values of Ci by changing the ambient CO2 concentration. The Ci was calculated as described by von Caemmerer and Farquhar (1981). Measurements with the LI-6200 system were started at an air CO2 concentration of ∼370 μl l−1 in the assimilation chamber. Measurements, for 8 s, were repeated three times and mean values were taken as the measured values. Leaves were exposed to natural light at a PPFD of >1200 μmol m−2 s−1 or to light from an artificial lamp (LA-180Me, Hayashi Watch Works, Tokyo) when the PPFD of sunlight was <1200 μmol m−2 s−1. In the paddy field, plants were examined from 08:30 to 11:00 when Pn was close to the daily maximum (Hirasawa and Ishihara, 1992; Ishihara, 1995). The Pn and gs of individual leaves were measured for 2 d or 3 d in succession and an average value was calculated.

Quantitation of the Rubisco content and the nitrogen content of individual leaves

Flag leaves were collected immediately after completion of measurement of Pn and gs, and they were stored at –80 °C prior to analysis. The area and fresh weight of each leaf were determined and each leaf was separated into two equal parts for separate quantification of Rubisco and nitrogen. The halves of leaves were homogenized separately with a mortar and pestle in a solution that contained 50 mM TRIS-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 5% (w/w) insoluble polyvinylpyrrolidone (Polyclar VT, Wako Chemicals, Tokyo). Each homogenate was centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was used for quantitation of Rubisco by the single radial immunodiffusion method (Sugiyama and Hirayama, 1983) with rabbit polyclonal antibodies raised against purified Rubisco from rice. Nitrogen was quantified with a carbon and nitrogen analyser (MT700 Mark II, Yanako, Kyoto). Both Rubisco and nitrogen content of leaves were expressed on a per leaf area basis. In experiments in which Rubisco was not quantified, an 8 cm wide segment was cut from the central part of the leaf for quantitation of nitrogen.

Quantitation of the accumulation and distribution of nitrogen

Two plants with an average number of panicles per replicate were harvested in the paddy field at the full heading stage. Each plant was separated into leaves, stems plus leaf sheaths, and panicles, and dried in an oven at 80 °C for >72 h. After weighing, samples were powdered with a mill (WB-1, Osaka Chemical Ltd, Osaka) and the concentration of nitrogen in each sample was determined with the CN analyser (MT700 MarkII). The nitrogen content of each organ was determined by the product of the dry weight and the concentration of nitrogen.

Determination of the hydraulic conductance and hydraulic conductivity of plants

For plants grown in the paddy field, the hydraulic conductance from the soil through the roots to the flag leaf (Cp) was calculated from the following equation (Hirasawa and Ishihara, 1991):

| (1) |

where Ψs is the water potential of the soil immediately outside the root, Ψl is the water potential of a flag leaf, and T is the transpiration rate per leaf area at steady state. Since rice plants were grown under submerged conditions and the water potential of soil solution was high enough when compared with Ψl and kept constant, Ψs could be regarded here as 0. The transpiration rate of a single intact leaf was measured in an air-sealed acrylic assimilation chamber (Hirasawa and Ishihara, 1991) under natural sunlight. Air, with the dewpoint controlled to 10 (±0.1) °C, was pumped into the chamber at a rate of 6.67×10−5 m3 s−1. The humidity of the air that was pumped into and out of the chamber was measured with a dewpoint hygrometer (model 660, EG&G Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). When the transpiration rate reached a constant value, the water potential of the leaf was measured with a pressure chamber (model 3005, Soil Moisture Equipment Inc., Santa Barbara, CA, USA), as described by Hirasawa and Ishihara (1991). The transpiration rate was calculated per leaf area.

For plants grown in 3.0 l pots, Cp from roots to leaves was calculated as follows:

| (2) |

where Uw is the water uptake rate of the whole plant and Ψl is the water potential of the uppermost three leaves. Measurements were made in an environment-controlled chamber (air temperature 28 °C, air vapour pressure deficit ∼1.5 kPa, and PPFD at the top leaves ∼1000 mol m−2 s−1). The water uptake rate was determined from the rate of weight loss of the pot after a steady state had been reached. To prevent evaporation from the surface of the pot, the top of the pot was covered with polystyrene foam and oily clay was used to seal the gap between the foam and the stem. After measurement of the water uptake rate, the leaf water potential of the uppermost three leaves was measured with the pressure chamber. Following that, roots were washed gently with water and the root surface area (A) was measured with an image analyser (Win-Rhizo REG V 2004 b, Regent Inc., Quebec, Canada). Hydraulic conductance per root surface area, taken here as the hydraulic conductivity of a plant (Lp), was calculated as follows:

| (3) |

Treatments with a polyethylene bag and leaf excision

To increase the stomatal conductance of the leaves of Koshihikari, polyethylene bag and leaf excision treatments were conducted. For polyethylene bag treatment, individual leaves were covered with a transparent polyethylene bag and illuminated with artificial light (LA-180Me) for 20 min. The PPFD at the surface of the bag was ∼1000 μmol m−2 s−1. Immediately after removal of the bag and blotting of water drops with gauze, Pn of the leaf was measured with an LI-6400 system at a CO2 concentration of 370 μl l−1. For leaf excision, after the leaf gas exchange had reached a steady state, the leaf was excised at its base with a razor blade. Pn was recorded continuously after both treatments at 5 s intervals and the maximum value was determined as the value ‘after treatment’.

Plant materials for genetic analysis

Backcross progeny populations and lines derived from a cross between Koshihikari and Habataki were developed for genetic dissection of the regions for the rates of photosynthesis on chromosomes 4 and 8. BC1F1 that was crossed between F1 and Koshihikari was developed. A total of 137 uniformly (average 10 cM) distributed simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers were used to determine the genotypes. In the following generations, the regions except the homozygous regions for the Koshihikari allele were determined by the SSR markers.

First, two BC5F1 plants were developed, 611-8 F1 and 611-10 F1, with a heterozygous genomic region on the long arm of chromosome 4 and on the short arm of chromosome 8, respectively. These regions included the QTLs for the photosynthetic rate defined in a previous report (Nito et al., 2007a, b). 611-8 F1 also carried heterozygous genomic regions on chromosomes 1, 2, and 5, as did 611-10 F1 on chromosomes 2 and 5. One hundred plants from self-pollinated F2 populations derived from each F1 plant were transplanted to the paddy field.

Secondly, homozygous recombinant lines were developed to determine the precise locations of each QTL. Nine lines of BC4F3 or BC5F3 for identification of the region for chromosome 4 and nine lines of BC5F3 or BC5F4 for that on chromosome 8 were selected. Each line had only a single chromosomal segment from Habataki on the genetic background of Koshihikari.

QTL analysis

Total DNA from each plant of the 611-8 F2 and 611-10 F2 populations was extracted from leaves by the cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Murray and Thomson, 1980). The genotypes of chromosomes 4 and 8 were determined with seven and five SSR markers, respectively. Linkage maps were constructed using MAPMAKER/EXP 3.0 (Lander et al., 1987). The positions on chromosomes and the effects of putative QTLs were determined by composite interval mapping with QTL Cartographer 2.0 (Basten et al., 2002). The threshold for detection of a QTL was based on 1000 permutation tests at the 5% level of significance (Churchill and Doerge, 1994). The additive and dominant effects and phenotypic variance explained by each QTL were estimated at the peak of the log of the odds score (LOD).

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences between two groups and between Koshihikari and other lines was determined by Student's t-test and by Dunnett's test, respectively, using KyPlot software (version 4.0, Kyence Tokyo).

Results

Characterization of the traits that influence the rate of leaf photosynthesis in Koshihikari and Habataki

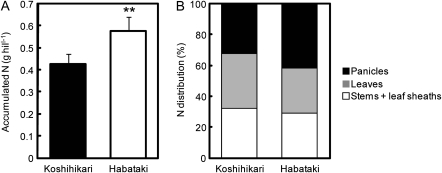

At the full heading stage, the leaf photosynthetic rate (Pn) at an ambient CO2 concentration of 370 μl l−1 in Habataki was very much higher than in Koshihikari in a submerged paddy field, when both cultivars were treated with the same fertilizer regime (Fig. 1A). Stomatal conductance (gs) in Habataki was significantly higher than in Koshihikari (Fig. 1B). In addition, the Rubisco content of individual leaves was higher in Habataki than in Koshihikari, indicating that the photosynthetic activity of Habataki was higher than that of Koshihikari (Fig. 1C). Habataki also had a higher level of leaf nitrogen, which might be expected to contribute to the higher level of Rubisco (Fig. 1D). From these results, the higher stomatal conductance and the higher nitrogen content of individual leaves in Habataki were potential factors that contributed to the higher rate of photosynthesis. The total amount of accumulated nitrogen was significantly larger in Habataki than in Koshihikari, while the percentage of nitrogen distributed to leaves was somewhat smaller in Habataki than in Koshihikari (Fig. 2). These findings indicated that the greater accumulation of nitrogen in Habataki than in Koshihikari was responsible for the higher level of leaf nitrogen.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the rates of photosynthesis (Pn; A), stomatal conductance (gs; B), Rubisco contents (C), and nitrogen (N) contents (D) of flag leaves of Koshihikari and Habataki after growth in the paddy field under submerged conditions to the full heading stage. Pn and gs were measured with an LI-6400 system between 08:30 and 11:00. Vertical bars represent the SD (n=5). Asterisks ** and *** indicate significance at the 0.01 and 0.001 level, respectively, as compared with Koshihikari (t-test).

Fig. 2.

Accumulated nitrogen in aboveground parts (A) and the nitrogen (N) distribution rates to panicles, leaves, and stems plus leaf sheaths (B) in Koshihikari and Habataki after growth in the paddy field to the full heading stage. Asterisks ** indicate significance at the 0.01 level as compared with Koshihikari (t-test).

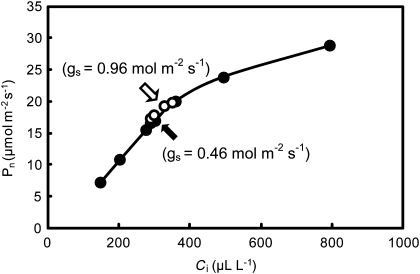

In order to eliminate the effects of the difference in leaf nitrogen content on the difference in Pn, a small amount of nitrogen fertilizer was applied to Koshihikari and the leaf nitrogen content of Koshihikari was brought to that of Habataki (Table 1). Although there was no difference between Koshihikari and Habataki in terms of the relationship between the intercellular CO2 concentration and Pn, Pn in Habataki at an ambient CO2 concentration of 370 μl l−1 was still higher than that in Koshihikari due to the larger gs of Habataki (Fig. 3). After leaves had been covered with transparent polyethylene bags for 20 min under an irradiance of ∼1000 μmol photons m−2 s−1, Pn in Koshihikari increased to the level in Habataki as a result of significant increases in gs because of high humidity and low CO2 concentration inside the bag, while the increases of Pn in Habataki were small (Table 1). The water potential of the flag leaf in Koshihikari decreased significantly compared with that in Habataki despite the fact that plants of both cultivars were growing under submerged soil conditions and the air vapour pressure deficit was as low as 1.5 kPa (Table 1). After excision of a leaf at its base and release of the hydrostatic pressure in the xylem, after leaf gas exchange had reached a steady state, Pn in Koshihikari increased to that in Habataki within a few minutes, a phenomenon known as the ‘Ivanov effect’ (Slavik, 1974), while there was little increase in Habataki (Table 1). The hydraulic conductance from roots to leaves (Cp) was far higher in Habataki than in Koshihikari (Table 1). Maintenance of the high water potential in Habataki, when stomata were fully open and the transpiration rate was high, was due to the higher hydraulic conductance of Habataki plants.

Table 1.

Changes in the rate of photosynthesis (Pn; μmol m−2 s−1) after treatment with a polyethylene bag (A) and after excision (B), the hydraulic conductance from roots to leaves (Cp), and the leaf nitrogen (N) content in Koshihikari and Habataki that had been grown in 3.0 l pots under submerged conditions to the full heading stage

| A |

B |

Cp (10−6 m MPa−1 s−1) | N content (g m−2) | |||

| Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | |||

| Koshihikari | 16.5±0.7 | 18.0±0.7 | 17.1±1.3 | 20.1±1.5 | 0.17±0.01 | 1.31±0.03 |

| Habataki | 19.0±1.2 | 18.9±1.1 | 20.7±0.7 | 21.1±1.1 | 0.29±0.02 | 1.24±0.11 |

| ** | NS | * | NS | * | NS | |

Leaf nitrogen contents in the two cultivars were equalized by application of ammonium sulphate to Koshihikari 10 d before measurements. Leaves in (A) were covered with a transparent polyethylene bag and illuminated for 20 min at a PPFD of 1000 μmol m−2 s−1 at the surface of the bag. Leaves in (B) were excised after Pn had reached a steady state. Pn increased for a few minutes, known as the ‘Ivanov effect’, and then decreased. The maximum Pn after both treatments was represented as Pn after treatment. Cp was expressed on a per leaf area basis. The water potential of an entire flag leaf blade, as measured with a pressure chamber, was –0.42±0.04 MPa and –0.32±0.03 MPa for Koshihikari and Habataki, respectively, at an air vapour pressure deficit of ∼1.5 kPa, an air temperature of 28 °C, and a PPFD of 1000 μmol m−2 s−1. Data are means ±SD (n=3–5). *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 level, respectively, as compared with Koshihikari (t-test). NS, no significant difference.

Fig. 3.

Rates of photosynthesis (Pn) plotted against the intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) of the flag leaf with similar nitrogen content in Koshihikari (filled circles) and Habataki (open circles) after growth in 3.0 l pots under submerged conditions to the full heading stage. The filled (Koshihikari) and open (Habataki) arrows indicate rates at an ambient CO2 concentration of 370 μl l−1. The measurements were made with an LI-6400 system.

QTLs responsible for the rate of photosynthesis in leaves

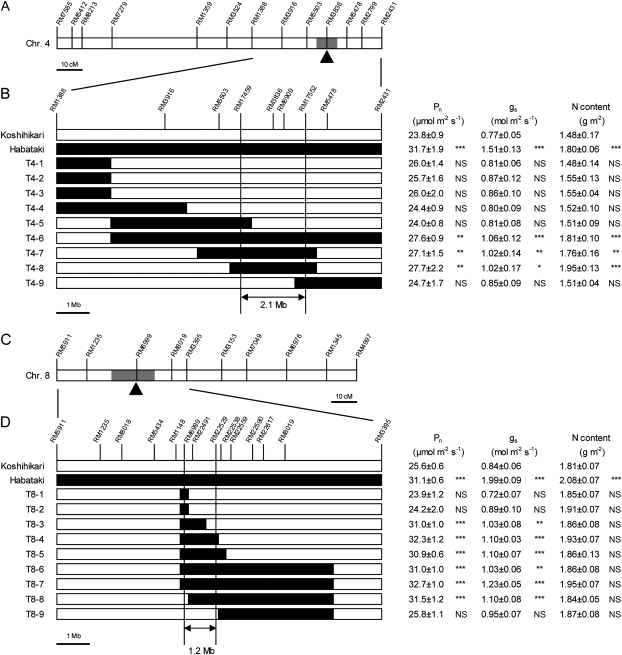

To define the map positions of the QTLs that were identified on chromosomes 4 and 8 by use of CSSLs derived from Sasanishiki and Habataki in a previous study (Nito et al., 2007a, b), QTL analysis was conducted for Pn using two BC5F2 populations derived from a cross between Koshihikari and Habataki at the full heading stage (Table 2). The primary generations, 611-8 F1 and 611-10 F1, had heterozygous regions on the long arm of chromosome 4 and on the short arm of chromosome 8, respectively. From the analysis in 611-8 F2, one QTL for increased Pn was identified at marker RM3836 on chromosome 4 (Table 2 and Fig. 4A). The phenotypic variance explained by the QTL was 9.1%. The additive effect of the Habataki allele was 1.3 μmol m−2 s−1, indicating that the Habataki allele increased Pn. From the analysis of 611-10 F2, a QTL for increased Pn was identified at marker RM6999 on chromosome 8 (Table 2 and Fig. 4C). The phenotypic variance explained by the QTL was 6.2%. The additive effect of the Habataki allele was 1.7 μmol m−2 s−1, indicating that the Habataki allele increased Pn. From these results, it was confirmed that the chromosome segment of Habataki, which previously had an effect on the increase in the rate of photosynthesis of Sasanishiki, could also increase the rate of photosynthesis of Koshihikari.

Table 2.

Putative QTLs controlling the leaf photosynthetic rate detected in the BC5F2 populations grown in the paddy field at the full heading stage

| Trait | Chromosome | Flanking marker | LODa | Ab | Dc | R2d |

| Photosynthetic rate | 4 | RM3836 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 9.1 |

| 8 | RM6999 | 5.1 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 6.2 |

The QTLs on chromosome 4 and 8 were detected in the 611-8 F2 and 611-10 F2 populations, respectively. The photosynthetic rate was measured with an LI-6200 system at an ambient CO2 concentration of 370 μl l−1 between 08:30 and 11:00.

A putative QTL with significant LOD scores in 1000 permutation tests at the 5% level.

Additive effect of the allele from Habataki compared with that from Koshihikari.

Dominant effect of the allele from Habataki compared with that from Koshihikari.

Percentage phenotypic variance explained by each QTL.

Fig. 4.

QTL analysis and substitution mapping of genes for the leaf photosynthetic rate on chromosomes 4 and 8. (A and C) Chromosomal locations of QTLs that control the rate of photosynthesis. The open bars indicate the entire chromosomes. SSR markers used in the QTL analysis are indicated above the bars. The shaded bars indicate the confidence intervals of the QTLs detected by analysis of the BC5F2 populations. The arrowheads indicate the most likely position of the QTLs, as determined by composite interval mapping. (B and D) Substitution mapping of the QTLs that control leaf photosynthesis. The genotypes of Koshihikari, Habataki, and homozygous recombinant lines are shown schematically on the left. SSR markers used are indicated at the top of each panel. White bars, homozygous for Koshihikari alleles; black bars, homozygous for Habataki alleles. All other chromosome regions of the lines, which were not shown in the figure, were homozygous for Koshihikari alleles. On the right, the rate of photosynthesis (Pn), stomatal conductance (gs), and the nitrogen (N) content of flag leaves of plants after growth in the paddy field to the full heading stage. Data are means ±SD (n=5). The measurements of Pn and gs were made with an LI-6200 system (C) and an LI-6400 system (D) at an ambient CO2 concentration of 370 μl l−1 between 08:30 and 11:00. The candidate genomic regions for the control of the rate of photosynthesis are indicated by double-headed arrows below the genotypes. Asterisks *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 level, respectively, as compared with Koshihikari (Dunnett's test). NS, no significant difference.

Given the results of the QTL analysis, two sets of homozygous recombinant lines were developed, in which each line carried a single chromosomal segment from Habataki around the regions of the putative QTLs. All other regions of the genome were homozygous for the Koshihikari allele. In the case of the regions from chromosome 4, values of Pn at the full heading stage in T4-6, T4-7, and T4-8 were 14–16% higher than in Koshihikari, and the differences are significant (Fig. 4B). Substitution mapping, using nine lines, allowed the region to be narrowed down to an interval of ∼2.1 Mb between RM17459 and RM17552. Similarly, in the case of the regions from chromosome 8, values of Pn in T8-3, T8-4, T8-5, T8-6, T8-7, and T8-8 were 21–28% higher than in Koshihikari and it was possible to narrow down the region to the interval of ∼1.2 Mb between RM6999 and RM22529 (Fig. 4D). The reason why the Pn of these six lines increased comparably with that of Habataki is unclear.

Functions of the candidate genomic regions

In the case of QTLs from chromosome 4, the lines with high values of Pn, namely T4-6, T4-7, and T4-8, had higher values of gs and higher leaf nitrogen contents than Koshihikari (Fig. 4B). In contrast, with respect to chromosome 8, the leaf nitrogen contents in T8-3–T8-8, in which Pn were higher than in Koshihikari, were similar to those in Koshihikari, while values of gs in these lines were higher than in Koshihikari (Fig. 4D).

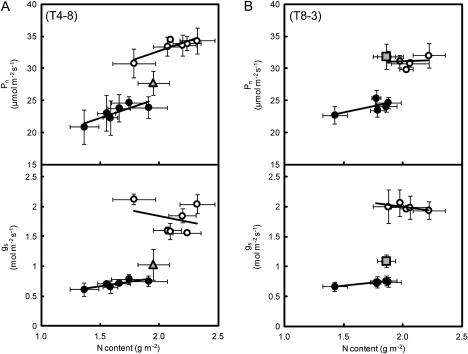

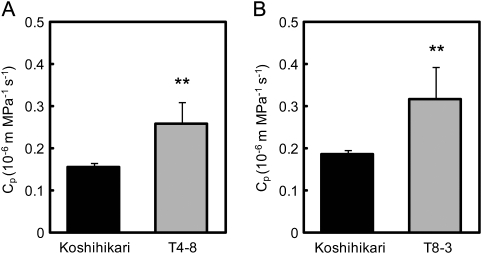

T4-8 and T8-3 of these lines were considered as NILs and they wer used for more detailed analysis of the functions of these QTLs. It was found that both the Pn and gs in T4-8 and T8-3 were higher than in Koshihikari when compared at the same leaf nitrogen content (Fig. 5). Cp in T4-8 and T8-3 was higher than that in Koshihikari (Fig. 6). The causes of the higher Cp in these lines were analysed by comparing root surface area and Lp (Table 3). Root surface area was higher in Habataki than in Koshihikari, while there is no difference in Lp between Koshihikari and Habataki. The larger root surface area might be responsible for the higher Cp of Habataki. The root surface area in T4-8 was ∼30% larger than in Kohishikari and the Lp in T4-8 was similar to that in Koshihikari. In contrast, root surface area in T8-3 was as large as that in Koshihikari, but Lp in T8-3 was significantly higher than in Koshihikari.

Fig. 5.

Relationships between nitrogen content (N) and the rate of photosynthesis (Pn; upper panels) and stomatal conductance (gs; lower panels) of flag leaves of homozygous recombinant lines and parental cultivars after growth in the paddy field to the full heading stage. Filled circles, open circles, shaded triangles (in A) and shaded squares (in B) represent Koshihikari, Habataki, T4-8, and T8-3, respectively. The measurements in (A) were made with an LI-6200 system and those in (B) were made with an LI-6400 system at an ambient CO2 concentration of 370 μl l−1 between 08:30 and 11:00. Vertical and horizontal bars represent the SD (n=5).

Fig. 6.

Hydraulic conductance from roots to the flag leaf (Cp) in T4-8 (A) and T8-3 (B) compared with that in Koshihikari after growth in the paddy field to the ripening stage. Cp was expressed on a per leaf area basis. Vertical bars represent the SD (n=5). Asterisks ** indicate significance at the 0.01 level, as compared with Koshihikari (t-test).

Table 3.

Hydraulic conductance of plants (Cp), root length, root surface area, and hydraulic conductivity of plants (Lp) grown in 3.0 l pots under submerged conditions to the ripening stage

| Cp (10−6 m3 MPa−1 s−1) | Root length (m) | Root surface area (m2) | Lp (10−8 m MPa−1 s−1) | |

| Koshihikari | 9.8±0.9 | 88.3±1.4 | 0.060±0.003 | 1.55±0.14 |

| Habaraki | 22.4±1.0*** | 211.8±8.8*** | 0.156±0.003*** | 1.40±0.11NS |

| T4-8 | 11.5±1.0* | 120.2±11.7* | 0.077±0.006* | 1.51±0.09NS |

| T8-3 | 11.7±0.6* | 81.0±7.9NS | 0.056±0.006NS | 2.17±0.10** |

Data are means ±SD (n=2– 5). Cp, root length and root surface area were expressed on a per stem basis. Asterisks *, ** and *** indicate significance at the 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 levels, respectively, as compared with Koshihikari (Dunnett's test). NS, no significant difference.

Discussion

Traits contributing to the higher rate of photosynthesis in Habataki than in Koshihikari

In general, the rate of leaf photosynthesis in rice plants is affected to a significant extent by the carboxylation rate and the rate of diffusion of CO2 from the atmosphere into the leaf at the ambient atmospheric concentration of CO2 (Makino et al., 1984; Kramer and Boyer, 1995). In the present study, a high-yielding indica variety, Habataki, had a higher rate of leaf photosynthesis than the japonica variety, Koshihikari (Fig. 1). The higher rate was caused by a higher leaf nitrogen content and, therefore, a higher Rubisco content at a given rate of nitrogen application, as well as the greater stomatal conductance of each leaf at a given level of leaf nitrogen (Figs 3, 5).

Leaf nitrogen content

The leaf nitrogen content is determined by the net accumulation of aboveground nitrogen and the rate of distribution of nitrogen to leaves (Mae and Ohira, 1981). Varietal differences in both of these parameters have been reported (Ookawa et al., 2003; Taylaran et al., 2009). The rate of distribution of nitrogen to leaves was somewhat lower in Habataki than in Koshihikari, implying that the greater accumulation of nitrogen was responsible for the higher amount of nitrogen in Habataki leaves (Fig. 2). Root surface area and root length in Habataki were much higher than those in Koshihikari (Table 3), and it has been demonstrated that total root length and the accumulation of nitrogen are closely correlated in several old and new rice varieties (Taylaran et al., 2009). In addition, differences in the activities of ammonium transporters in roots (Sonoda et al., 2003; Suenaga et al., 2003) and/or in the activities of enzymes such as glutamine synthetase and glutamate synthetase (Obara et al., 2001) might contribute to differences in rates of nitrogen uptake per root surface area. The accumulation of nitrogen in plants is affected not only by the capacity of roots for nitrogen assimilation but also by the transportation of nitrogen to shoots via the transpirational stream (Cernusak et al., 2009). The transpirational uptake of water is likely to be greater in plants with larger root systems (Hirasawa et al., 1992b), and such uptake provides a plausible explanation for the greater accumulation of nitrogen by Habataki. However, the nitrogen assimilation capacity of the roots in Habataki remains to be investigated.

Stomatal conductance

The vapour pressure deficit with respect to the atmosphere has a marked effect on the stomatal conductance of rice via the rate of transpiration. In general, the deficit reaches ∼1.5–1.8 kPa between 09:00 and 10:00 on a clear day. It is well known that, even if soil moisture conditions are adequate, the rate of photosynthesis in leaves of rice plants decreases at midday and in the afternoon, as a result of water stress, after the rate has reached a maximum during the morning (Hirasawa and Ishihara, 1992; Ishihara, 1995), as is also true in maize (Hirasawa and Hsiao, 1999). However, the present results (Table 1) indicate that, even with such a relatively low vapour pressure deficit in the morning, the leaves of Koshihikari experience water stress, and Pn, measured in the morning, does not approach the maximum value.

The water balance within a plant is strongly affected by hydraulic conductance (Holbrook, 2006; Hopkins and Huner, 2008). With increases in transpiration, the leaf water potential decreases more in plants with low hydraulic conductance than it does in plants with high hydraulic conductance (Slatyer, 1967). The critical water potential for stomatal closure is very much higher in rice than in other crop plants, such as wheat, soybean, and cotton (Hirasawa, 1999). These observations might explain why the hydraulic conductance affects stomatal conductance. Brodribb et al. (2007) found that, in an analysis of 43 plant species, the maximum rate of photosynthesis was correlated both with the distance between veins and the leaf surface and with the hydraulic conductance of the leaf. Woodruff et al. (2008) found, in the foliage of Pseudotsuga menziesii trees of different height classes, that the maximum rate of photosynthesis was correlated both with mesophyll thickness and with the hydraulic conductance of individual leaves. The present results confirmed the importance of hydraulic conductance in defining photosynthetic capacity.

The hydraulic conductance in entire rice plants is determined mainly by the conductance of the roots (Hirasawa et al., 1992a). Since the axial conductance of roots is very large compared with the radial conductance, root hydraulic conductance can be considered to be derived from two components: root hydraulic conductivity (Lpr; conductance per root surface area) and root surface area (Steudle and Peterson, 1998). Root surface area in Habataki was much larger than that in Koshihikari, but there was no difference in Lp between Koshihikari and Habataki. It was concluded that the larger root surface area contributed to the higher Cp in Habataki (Table 3).

Chromosomal regions responsible for the rate of photosynthesis

Genetic regions that control the rate of photosynthesis were identified between RM17459 and RM17552 on chromosome 4 and between RM6999 and RM22529 on chromosome 8 (Fig. 5). Teng et al. (2004) identified QTLs for the rate of leaf photosynthesis on chromosomes 4 and 6 using a double haploid population derived from anther culture of ZYQ8/JX17. However, these regions are not identical to the regions that were located here. To our knowledge, no NILs with a high rate of photosynthesis were available and the genomic effects have not been analysed in detail. Two NILs carrying a QTL (i.e. QTL-NILs) were developed and the traits contributing to an increase in the rate of photosynthesis were analysed. According to the results, the QTL region on chromosome 4 increases leaf nitrogen content and gs via increases in Cp through a larger root surface area, while the QTL region on chromosome 8 increases Cp through a larger Lp and, as a consequence, gs (Figs 4–6; Table 3).

Genetic regions responsible for leaf nitrogen content

Ishimaru et al. (2001) identified QTLs responsible for leaf nitrogen content on chromosome 2 and for Rubisco content on chromosomes 8, 9, and 12 using backcross inbred lines derived from a cross between Nipponbare and Kasalath. Kanbe et al. (2009) detected several QTLs for Rubisco content on chromosome 10 using CSSLs and backcross progeny populations derived from a cross between Koshihikari and Kasalath. Talukder et al. (2005) identified QTLs for the nitrogen concentration in individual plants on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, 7, 10, 11, and 12 using recombinant inbred lines derived from a cross between Bala and Azucena. However, these QTLs did not overlap with those identified on chromosome 4 in the present study.

Genetic regions responsible for stomatal conductance and hydraulic conductance

Although there are several reports of QTLs that control gs (Price et al., 1997; Frei et al., 2008; Khowaja and Price, 2008), these QTLs do not overlap the region identified in the present study. Many QTLs associated with root characteristics have been found close to the QTL on chromosome 4. QTLs for root thickness (Zhang et al., 2001; Kamoshita, 2002; Price et al., 2002), rooting ability of seedlings (Ikeda et al., 2007), and the dry weight and volume of roots (Qu et al., 2008) have been identified close to the region that was identified on chromosome 4. Thus, it is necessary to analyse this chromosomal region with the focus on the relationships between various root-morphological traits and functions of roots for the uptake and transport of water.

Interestingly, Lp in T8-3 was found to exceed that of Habataki, while the root surface area did not increase (Table 3). Varietal differences in the root hydraulic conductivity (Lpr) in rice are not known (Table 4; Miyamoto et al., 2001) and there are no reports of QTLs for Lpr in rice so far. The present finding suggests the possibility of improvement in Cp by increases of not only root surface area but also Lpr with marker-assisted selection. It will be necessary to examine in more detail the causes of the difference in Lpr.

The region of chromosome 4 was associated with increased nitrogen accumulation and water uptake, suggesting that separate traits controlled these two characteristics. However, given the correlation between root mass and the accumulation of nitrogen by the entire plant reported by Taylaran et al. (2009) and the relationship between root mass and hydraulic conductance of roots (Hirasawa et al., 1992b), it can be postulated that the increase in both the ability to accumulate nitrogen and water uptake might be caused by development of the root system. Isolation and characterization of the responsible genes on both chromosomes 4 and 8 are necessary for detailed analysis of the mechanisms of increased photosynthesis.

To increase the rate of leaf photosynthesis of Koshihikari further, it is necessary to accumulate multiple QTLs associated with Pn. Experiments are now in progress to try to combine the QTLs of chromosomes 4 and 8 and to evaluate the combined effect on Pn. Two other QTLs were localized using CSSLs derived from a cross between Sasanishiki and Habataki in a previous study (Nito et al., 2007a, b). The functions of the two QTLs in Pn and the effects of accumulation of all QTLs remain to be investigated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (no. 19380009) and from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, Japan (Green Technology Project, DM-U1119; and Genomics for Agricultural Innovation, QTL-1002).

References

- Asanuma S, Nito N, Ookawa T, Hirasawa T. Yield, dry matter production and ecophysiological characteristics of rice cultivar, Habataki compared with cv. Sasanishiki. Japanese Journal of Crop Science. 2008;77:474–480. [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma S, Ookawa T, Kondo M, Yano M, Ando T, Hirasawa T. QTL analysis of water transport capacity in rice: resistance to water transport in the lines of Habataki chromosome segment substitution in Sasanishiki. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Rice for the Future. 2007:237. [Google Scholar]

- Basten CJ, Weir BS, Zeng ZB. A reference manual and tutorial for QTL mapping. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina State University; 2002. QTL cartographer. Version 1.16. [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb TJ, Field TS, Jordan GJ. Leaf maximum photosynthetic rate and venation are linked by hydraulics. Plant Physiology. 2007;144:1890–1898. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.101352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak LA, Winter K, Turner BL. Plant δ15N correlates with the transpiration efficiency of nitrogen acquisition in tropical trees. Plant Physiology. 2009;151:1667–1676. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.145870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill GA, Doerge RW. Empirical threshold values for quantitative trait mapping. Genetics. 1994;138:963–971. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.3.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook MG, Evans LT. Some physiological aspects of the domestication and improvement of rice. Field Crops Research. 1983;6:219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ebitani T, Takeuchi Y, Nonoue Y, Yamamoto T, Takeuchi K, Yano M. Construction and evaluation of chromosome segment substitution lines carrying overlapping chromosome segments of indica rice cultivar Kasalath in a genetic background of japonica elite cultivar Koshihikari. Breeding Science. 2005;55:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR. Photosynthesis and nitrogen relationships in leaves of C3 plants. Oecologia. 1989;78:9–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00377192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta. 1980;149:78–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00386231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei M, Tanaka JP, Wissuwa M. Genotypic variation in tolerance to elevated ozone in rice: dissection of distinct genetic factors linked to tolerance mechanisms. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2008;59:3741–3752. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herve D, Fabre F, Berrios EF, Leroux N, Chaarani GA, Planchon C, Sarrafi A, Gentzbittel L. QTL analysis of photosynthesis and water status traits in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) under greenhouse conditions. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2001;52:1857–1864. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.362.1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa T. Physiological characterization of the rice plant for tolerance of water deficit. In: Ito O, O'Tool J, Hardy B, editors. Genetic improvement of rice for water-limited environments. Los Baños, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute; 1999. pp. 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa T, Gotou T, Ishihara K. On resistance to water transport from roots to the leaves at the different positions on a stem in rice plants. Japanese Journal of Crop Science. 1992a;61:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa T, Hsiao TC. Some characteristics of reduced leaf photosynthesis at midday in maize growing in the field. Field Crops Research. 1999;62:53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa T, Ishihara K. On resistance to water transport in crop plants for estimating water uptake ability under intense transpiration. Japanese Journal of Crop Science. 1991;60:174–183. [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa T, Ishihara K. The relationship between resistance to water transport and the midday depression of photosynthetic rate in rice plants. In: Murata N, editor. Research in photosynthesis. Vol. IV. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1992. pp. 283–286. [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa T, Ozawa S, Taylaran RD, Ookawa T. Varietal differences in photosynthetic rates in rice plants, with special reference to the nitrogen content of leaves. Plant Production Science. 2010;13:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa T, Tsuchida M, Ishihara K. Relationship between resistance to water transport and exudation rate and the effect of the resistance on the midday depression of stomatal aperture in rice plants. Japanese Journal of Crop Science. 1992b;61:145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook NM. Water balance of plants. In: Taiz L, Zeiger E, editors. Plant physiology. 4th edn. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2006. pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WG, Huner NPA. Introduction to plant physiology. 4th edn. Danvers, MA: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. Whole plant water relations; pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H, Kamoshita A, Manabe T. Genetic analysis of rooting ability of transplanted rice (Oryza sativa L.) under different water conditions. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2007;58:309–318. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Rice Genome Sequence Project. The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature. 2005;436:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nature03895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara K. Leaf structure and photosynthesis. In: Matsuo T, Kumazawa K, Ishii R, Ishihara K, Hirata H, editors. Science of the rice plant 2. Physiology. Tokyo: Food and Agriculture Policy Research Center; 1995. pp. 491–511. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii R. Cultivar differences. In: Matuso T, Kumazawa K, Ishii R, Ishihara K, Hirata H, editors. Science of the rice plant 2. Physiology. Tokyo: Food and Agriculture Policy Research Center; 1995. pp. 566–572. [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru K, Kobayashi N, Ono K, Yano M, Ohsugi R. Are contents of Rubisco, soluble protein and nitrogen in flag leaves of rice controlled by the same genetics? Journal of Experimental Botany. 2001;52:1827–1833. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.362.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang CZ, Ishihara K, Satoh K, Katoh S. Loss of the photosynthetic capacity and proteins in senescing leaves at top positions of two cultivars of rice in relation to the source capacities of the leaves for carbon and nitrogen. Plant and Cell Physiology. 1999;40:496–503. [Google Scholar]

- Kamoshita A, Wade LJ, Ali ML, Pathan MS, Zhang J, Sarkarung S, Nguyen HT. Mapping QTLs for root morphology of a rice population adapted to rainfed lowland conditions. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2002;104:880–893. doi: 10.1007/s00122-001-0837-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanbe T, Sasaki H, Aoki N, Yamagishi T, Ohsugi R. The QTL analysis of RuBisCO in flag leaves and non-structural carbohydrates in leaf sheaths of rice using chromosome segment substitution lines and backcross progeny F2 populations. Plant Production Science. 2009;12:224–232. [Google Scholar]

- Khowaja FS, Price AH. QTL mapping rolling, stomatal conductance and dimension traits of excised leaves in the Bala×Azucena recombinant inbred population of rice. Field Crops Research. 2008;106:248–257. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer PJ, Boyer JS. Water relations of plants and soils. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1995. Photosynthesis and respiration; pp. 313–343. [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES, Green P, Abrahamson J, Barlow A, Daley MJ, Lincoln SE, Newburg L. MAPMAKER: an interactive computer package for constructing primary genetic linkage maps of experimental and natural populations. Genomics. 1987;1:174–181. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(87)90010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SP, Zhu X-G, Naidu SL, Ort DR. Can improvement in photosynthesis increase crop yield? Plant, Cell and Environment. 2006;29:315–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mae T, Ohira K. The remobilization of nitrogen related to leaf growth and senescence in rice plants (Oryza sativa L.) Plant and Cell Physiology. 1981;22:1067–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Mae T, Ohira K. Changes in photosynthetic capacity in rice leaves from emergence through senescence. Analysis from ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase and leaf conductance. Plant and Cell Physiology. 1984;25:511–521. [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Mae T, Ohira K. Photosynthesis and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in rice leaves from emergence through senescence. Quantative analysis by carboxylation/oxygenation and regeneration of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate. Planta. 1985;166:414–420. doi: 10.1007/BF00401181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Mae T, Ohira K. Variation in the contents and kinetic properties of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylases among rice species. Plant and Cell Physiology. 1987;28:799–804. [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Mae T, Ohira K. Differences between wheat and rice in the enzymic properties of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and the relationship to photosynthetic gas exchange. Planta. 1988;174:30–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00394870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama S, Tajima K. Leaf conductance in japonica and indica rice varieties: I. Size, frequency, and aperture of stomata. Japanese Journal of Crop Science. 1990;59:801–808. [Google Scholar]

- Masumoto C, Ishii T, Kataoka S, Hatanaka T, Uchida N. Enhancement of rice leaf photosynthesis by crossing between cultivated rice, Oryza sativa and wild rice species, Oryza ryfipogon. Plant Production Science. 2004;7:252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto N, Steudle E, Hirasawa T, Lafitte R. Hydraulic conductivity of rice roots. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2001;52:1835–1846. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.362.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y. Studies on the photosynthesis of rice plants and its culture significance. Bulletin of the National Institute of Agricultural Sciences. 1961;D9:1–169. [Google Scholar]

- Murchie EH, Pinto M, Horton P. Agriculture and the new challenges for photosynthesis research. New Phytologist. 2009;181:532–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MG, Tompson WF. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Research. 1980;8:4321–4326. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nito N, Ookawa T, Kondo M, Yano M, Ando T, Hirasawa T. Analysis of QTLs for the rate of photosynthesis and their roles in photosynthesis using the series of Habataki chromosome segment substitution in rice variety, Sasanishiki. Japanese Journal of Crop Science. 2007a;76(Suppl 1):244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Nito N, Ookawa T, Kondo M, Yano M, Ando T, Hirasawa T. Varietal differences in leaf photosynthetic rate of rice and QTL analysis of photosynthesis using the lines of Habataki chromosome segment substitution in Sasanishiki. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Rice for the Future. 2007b:275. [Google Scholar]

- Obara M, Kajiura M, Fukuta Y, Yano M, Hayashi M, Yamaya T, Sato T. Mapping of QTLs associated with cytosolic glutamine synthetase and NADH-glutamate synthase in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Journal of Experimental Botany. 2001;52:1209–1217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsumi A, Hamasaki A, Nakagawa H, Yoshida H, Shiraiwa T, Horie T. A model explaining genotypic and ontogenetic variation of leaf photosynthetic rate in rice (Oryza sativa) based on leaf nitrogen content and stomatal conductance. Annals of Botany. 2007;99:265–273. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcl253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ookawa T, Naruoka Y, Yamazaki T, Suga J, Hirasawa T. A comparison of the accumulation and partitioning of nitrogen in plants between two rice cultivars, Akenohoshi and Nipponbare, at the ripening stage. Plant Production Science. 2003;6:172–178. [Google Scholar]

- Osada A. Photosynthesis and respiration in relation to nitrogen responsiveness. In: Matuso T, Kumazawa K, Ishii R, Ishihara K, Hirata H, editors. Science of the rice plant 2. Physiology. Tokyo: Food and Agriculture Policy Research Center; 1995. pp. 696–703. [Google Scholar]

- Price AH, Young EM, Tomos AD. Quantitative trait loci associated with stomatal conductance, leaf rolling and heading date mapped in upland rice (Oryza sativa) New Phytologist. 1997;137:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Mu P, Zhang H, Chen CY, Gao Y, Tian Y, Wen F, Li Z. Mapping QTLs of root morphological traits at different growth stages in rice. Genetica. 2008;133:187–200. doi: 10.1007/s10709-007-9199-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Ishii R. Cultivar differences in leaf photosynthesis of rice bred in Japan. Photosynthesis Research. 1992;32:139–146. doi: 10.1007/BF00035948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T. Rice genome analysis: understanding the genetic secrets of the rice plant. Breeding Science. 2003;53:281–289. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD. Photosynthesis in intact leaves of C3 plants: physics, physiology and rate limitations. Botanical Review. 1985;51:53–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda Y, Ikeda A, Saiki S, von Wiren N, Yamaya T, Yamaguchi J. Distinct expression and function of three ammonium transporter genes (OsAMT1;1–1;3) in rice. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2003;44:726–734. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatyer R. Plant–water relationships. London: Academic Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Slavik B. Methods of studying plant water relations. Prague: Czechoslovak Academy of Science; 1974. Transpiration; pp. 252–292. [Google Scholar]

- Steudle E, Peterson CA. How does water get through roots? Journal of Experimental Botany. 1998;49:775–788. [Google Scholar]

- Suenaga A, Moriya K, Sonoda Y, Ikeda A, Von Wiren N, Hayakawa T, Yamaguchi J, Yamaya T. Constitutive expression of a novel-type ammonium transporter OsAMT2 in rice plants. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2003;44:206–211. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Hirayama Y. Correlation of the activities of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase and pyruvate, orthophosphate dikinase with biomass in maize seedling. Plant and Cell Physiology. 1983;24:783–787. [Google Scholar]

- Takano Y, Tsunoda S. Curvilinear regression of the leaf photosynthetic rate on leaf nitrogen content among strains of oryza species. Japanese Journal of Breeding. 1971;21:69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Talukder ZI, McDonald AJ, Price AH. Loci controlling partial resistance to rice blast do not show marked QTL×environment interaction when plant nitrogen status alters disease severity. New Phytologist. 2005;168:455–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylaran RD, Ozawa S, Miyamoto N, Ookawa T, Motobayashi T, Hirasawa T. Performance of a high-yielding modern rice cultivar Takanari and several old and new cultivars grown with and without chemical fertilizer in a submerged paddy field. Plant Production Science. 2009;12:365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Teng S, Qian Q, Zeng D, Kunihiro Y, Fujimoto K, Huang D, Zhu L. QTL analysis of leaf photosynthetic rate and related physiological traits in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Euphytica. 2004;135:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD. Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas exchange of leaves. Planta. 1981;153:376–387. doi: 10.1007/BF00384257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff DR, Meinzer FC, Lachenbruch B. Height-related trends in leaf xylem anatomy and shoot hydraulic characteristics in a tall conifer: safety versus efficiency in water transport. New Phytologist. 2008;180:90–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y-F, Ookawa T, Ishihara K. Analysis of the photosynthetic characteristics of the high-yielding rice cultivar Takanari. Japanese Journal of Crop Science. 1997;66:616–623. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Yonemaru J, Yano M. Towards the understanding of complex traits in rice: substantially or superficially? DNA Research. 2009;16:141–154. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano M. Genetic and molecular dissection of naturally occurring variation. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2001;4:130–135. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo ME, Yeo AR, Flowers TJ. Photosynthesis and photorespiration in the genus. Oryza Journal of Experimental Botany. 1994;45:553–560. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zheng HG, Aarti A, et al. Locating genomic regions associated with components of drought resistance in rice: comparative mapping within and across species. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2001;103:19–29. [Google Scholar]