Abstract

Nineteen Arabidopsis accessions grown at low (LOW N) and high (HIGH N) nitrate supplies were labelled using 15N to trace nitrogen remobilization to the seeds. Effects of genotype and nutrition were examined. Nitrate availability affected biomass and yield, and highly modified the nitrogen concentration in the dry remains. Surprisingly, variations of one-seed dry weight (DW1S) and harvest index (HI) were poorly affected by nutrition. Nitrogen harvest index (NHI) was highly correlated with HI and showed that nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) was increased at LOW N. Nitrogen remobilization efficiency (NRE), as 15N partitioning in seeds (15NHI), was also higher at LOW N. The relative specific abundance (RSA) in seeds and whole plants indicated that the 14NO3 absorbed post-labelling was mainly allocated to the seeds (SEEDS) at LOW N, but to the dry remains (DR) at HIGH N. Nitrogen concentration (N%) in the DR was then 4-fold higher at HIGH N compared with LOW N, whilst N% in seeds was poorly modified. Although NHI and 15NHI were highly correlated to HI, significant variations in NUE and NRE were identified using normalization to HI. New insights provided in this report are helpful for the comprehension of NUE and NRE concepts in Arabidopsis as well as in crops and especially in Brassica napus.

Keywords: 15N, harvest index, nitrogen use efficiency, remobilization, yield

Introduction

A major challenge of modern agriculture is to reduce the excessive input of fertilizer and at the same time to improve grain quality without affecting yield. Yield and seed quality are important for human and animal food consumption. The percentage of protein contained in cereal grains determines their nutritive and commercial values and both nitrogen harvest index (NHI) as [grain N/whole plant N] and seeds nitrogen concentration (N%SEEDS) are major indicators of nitrogen use efficiency and seed nutritional quality (see Masclaux-Daubresse et al., 2010, for a review).

Until now, most plant cultivars have been selected under non-limiting nitrogen conditions (Bänziger et al., 1997; Presterl et al., 2003) for productivity and grain yield. Under such condition, it was shown that the improvement of seed dry weight and plant yield was associated with the increase in leaf longevity and with the prolongation of photosynthesis that contributes to carbon filling into seeds (Duvick, 1992; Rajcan and Tollenaar, 1999; Borrel et al., 2001; Gregersen et al., 2008). Because delaying leaf senescence was also shown to delay nitrogen remobilization (Diaz et al., 2008), negative correlations between grain protein concentrations and yield were also observed (Beninati and Busch, 1992). Therefore, it is suspected that breeding plants with delayed leaf senescence has to cope with the dilemma of getting higher yield but lower grain protein content. One way to solve the yield versus seed protein content dilemma and to decrease fertilizer use is to improve plant nitrogen management through manipulating nitrogen recycling and especially nitrogen remobilization from vegetative plant organs to the seeds. Improving nitrogen remobilization efficiency (NRE) from vegetative tissues has the advantage of improving grain filling while limiting exogenous nitrogen demand after flowering and to decrease the amount of unused nitrogen in the dry remains after harvest.

The main control for nitrogen filling in seeds is located in the source leaves and for some plants in the stems (Good et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2007). In contrast to carbon, the nitrogen imported into the developing seeds is largely derived from the recycling of nitrogen sources assimilated before the onset of the reproductive phase (Cliquet et al., 1990; Patrick and Offler, 2001). Depending on the species, it appears that nitrogen uptake is down-regulated and, for some, totally inhibited during seed filling. Studies using 15N tracing on cereals, oilseed rape, and legumes showed that the onset of grain filling was a critical phase for seed production, because N uptake and N2 fixation declined after flowering and during seeds maturation (Christensen et al., 1981; Salon et al., 2001; Rossato et al., 2002). In Arabidopsis, it is shown that, when plants are grown under non-limiting N supply conditions, nitrate uptake is lower during seed maturation than in the vegetative stage, although it still operates (Masclaux-Daubresse et al., 2010).

To study nitrogen remobilization, special tools and skills have been developed and adapted to different plant species. In crops, the total nitrogen amount at anthesis and at harvest time was determined to give an estimation of the amount of nitrogen remobilized or absorbed after anthesis (Masclaux-Daubresse et al., 2008, and references therein). This method, called the ‘apparent remobilization’ method, was, however, subject to large experimental errors. Despite such inconvenience, the mapping of QTL of nitrogen remobilization was possible using this method in barley and durum wheat (Joppa et al., 1997; Mickelson et al., 2003).

The use of 15N tracing, also named 15N long-term labelling, is a good alternative that allows the determination of fluxes. Long-term labelling was usually achieved by applying 15N nitrate to plants grown either under controlled conditions in hydroponics, sand or compost (Diaz et al., 2008) or in the field (Gallais et al., 2006). Recently using such 15N long-term labelling in maize, several QTL of N uptake and N remobilization were mapped. In this report, traits for NUE were monitored and the coincidence of QTL for agronomical, physiological, and biochemical traits was observed. QTL clustering showed antagonism between N remobilization and N uptake at several loci. Positive coincidences between N uptake, root system architecture and leaf greenness were also found. Most of the N remobilization QTL mapped were co-localizing with leaf senescence QTL. The mapping of QTL for NRE in wheat and maize then confirmed that the contribution of leaf N remobilization to grain N content varyed depending on genotype and on environment (Joppa et al., 1997; Coque et al., 2008).

While the approaches commonly used with Arabidopsis to explore the network of leaf senescence and nitrogen remobilization processes are mutant analysis and transcriptomic approaches, the recent reports of Diaz et al. (2008) and Lemaître et al. (2008) showed that both genetic and environmental variations exist for these traits in Arabidopsis. Exploring natural variation of N remobilization and seed filling under different environmental conditions might then be highly informative.

In the present study, a similar plant material to that used by Chardon et al. (2010) was used to evaluate the proportion of nitrogen remobilized from rosette leaves to the seeds using the 15N-labelling procedure already experimented in our laboratory (Diaz et al., 2008). From the agronomic traits related to biomass, yield, carbon, and nitrogen concentrations in seeds and dry remains, the nitrogen use efficiency of accessions for seed production was estimated. From 15N partitioning in seeds nitrogen remobilization efficiency (NRE) was estimated for all the accessions. All the data collected allow us to understand the physiology of N remobilization for seed production in Arabidopsis in response to nitrate availability and to detect extreme or uncommon accessions with regard to the global behaviour of the Arabidopsis thaliana core collection. In addition, while these data do not provide any mechanistic information about N-remobilization, they demonstrate the physiological links existing between traits and provide new indicators that will be useful for further studies in Arabidopsis and crops, such as rapeseed.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Seeds of the Arabidopsis thaliana Akita, Bl-1, Bur-0, Col-0, Ct-1, Edi-0, Ge-0, Kn-0, Mh-1, Mr-0, Mt-0, N13, Oy-0, Sakata, Shahdara, St-0, Stw-0, Tsu-0, and WS have been provided by the Versailles Resource Centre (INRA Versailles France, http://dbsgap.versailles.inra.fr/vnat/) and the same batches of seeds (except WS) were used by Chardon et al. (2010) to study natural variation of nitrate uptake. Sixteen of these accessions are part of the core collection of 24 accessions selected by McKhann et al. (2004) on the basis of genetic variability only. Then the 16 accessions retained from the core collection of 24 lines were selected on the basis of their genetic variability and on their close flowering time in short days (see Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online). Accessions that presented very early flowering or very late flowering times have been eliminated. Col-0 and WS, which are parental lines for most of the recombinant inbred lines and mutant populations available at Versailles Resource Center were added. Mr-0 was also added.

Seeds were sown in small pots filled with medium particle size sand topped with a thin layer of small particle size sand at the same time and in the same conditions as performed by Chardon et al. (2010). One week after sowing, a single seedling was retained in each pot, and black sand poured to avoid algal proliferation. Two independent biological repeats were carried out in two consecutive culture cycles in the same growth chamber. Each biological repeat included four accession repetitions (four plants per genotype). Plants were grown in short days (8 h light) with 21 °C day and 17 °C night temperatures. Photon flux density was 160 μmol m−2 s−1 until they reached 56 DAS (days after sowing). At 56 DAS, plants were transferred to long day conditions (16 h light), maintaining similar day/night temperatures and light intensity in order to induce flowering and to reduce flowering variation between accessions. Plants were cultivated on sand under low nitrogen nutrition (LOW N, 2 mM nitrate) or under high nitrogen nutrition (HIGH N, 10 mM nitrate) as described in Chardon et al. (2010).

15N labelling, flowering induction, and harvest

At the two 15N-uptake time points 40 DAS and 42 DAS, the unlabelled watering solution was replaced by a solution that had the same nutrient composition except that 14NO3- was replaced by 15NO3 10% enrichment (see Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online). After labelling, plant roots and sand were rinsed with deionized water. Unlabelled nutrient solution was then used for the rest of the culture cycle. Plants were grown in short days until 56 DAS. Afterwards, plants were transferred to long day conditions (light/dark cycle 16 h/8 h) to induce flowering. Plants were harvested at the end of their cycle when all seeds were matured and the rosette dry. Samples were separated as (i) dry remains (DR=rosette+stem+cauline-leaves+empty-dry-siliques) and (ii) total seeds (SEEDS). It has to be noted that roots were included in the DR and were not used for measurements because a large part of the root system was lost in the sand at harvest. The dry weight (DW) of the DR and SEEDS were determined. Four replicates (plants) were harvested and the experiment was carried out twice.

Determination of total nitrogen content and 15N abundance

For all the experiments, unlabelled samples were harvested in order to determine the 15N natural abundance. After drying and weighing each plant, material was ground to obtain a homogenous fine powder. A subsample of 1000–2000 μg was carefully weighed in tin capsules (Sartorius MP2P) to determine the total N content and 15N abundance using an elemental analyser (roboprep CN, SERCON Europa Scientific Ltd, Crewe, UK) coupled to an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Tracermass, PDZ Europa Scientific Ltd, Crewe, UK) calibrated using natural abundance. The 15N abundance was calculated as atom per cent and defined as A%=100×(15N)/(15N+14N) for labelled plant samples and for unlabelled plant controls (A%control was c. 0.3660). The 15N enrichment (E%) of the plant material was then defined as (A%sample–A%control). The absolute quantity of 15N contained in the sample was defined as Q=DW×E%×N% with N% the concentration of nitrogen in the sample (as mg of nitrogen per 100 mg dry weight). The partition of 15N (in μg) in the seeds compared with the whole plant was calculated as (QSEEDS)/(QSEEDS+QDR). The relative specific abundance (RSA) of 15N of the sample was calculated as (A%sample–A%control)/(A%nutritive_solution–A%control), with A%nutritive_solution=0.1. The RSASEEDS/RSA[SEEDS+DR] ratio previously described by Gallais et al. (2006) was calculated as (E%SEEDS)/[(E%SEEDS×N%SEEDS×DWSEEDS+E%DR×N%DR×DWDR)/(N%SEEDS×DWSEEDS+N%DR×DWDR)].

Flowering time

Flowering time was recorded as the number of days between seed germination and bolting (i.e. the time when the principal bud starts to emerge). Values obtained on the four plant repeats were averaged.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of phenotypic data was carried out by analysis of variance, using the GLM procedure of SAS using Supplementary Table S0 (which can be found at JXB online) as the data source. The adjusted means for each accession was estimated with the LSMEANS option. Genetic variances at HIGH N and LOW N were then estimated with the VARCOMP option of SAS. Heritability was estimated: h2=σ2g/(σ2g+[σ2e/r]), with σ2g being the genetic variance, σ2e the residual variance, and r the number of replicates. Correlations between traits within nitrogen conditions were computed using the Proc CORR procedure of SAS. Normal distribution of measured and calculated traits was verified using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test using XLSTAT.

Results and discussion

Nitrogen limitation affects plant biomass, yield, and harvest index but does not change one-seed dry weight

Several traits related to yield and nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) have been measured or calculated on the 19 accessions of Arabidopsis cultivated under low (LOW N; 2 mM nitrate) and high (HIGH N, 10 mM nitrate) nitrogen nutrition (see Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online). The dry weights (DW, as g plant−1), nitrogen concentration (N%, mg 100 mg−1 DW), carbon concentration (C%, mg 100 mg−1 DW), and 15N enrichment (E%, 15N as % of total N) were measured on the dry remains (DR) and seeds (SEEDS) after harvest. The dry weight of one-seed (DW1S) was also determined.

From the measured trait data, key indicators for yield and NUE were calculated as follows. From the dry weights (DW) harvest index (HI) was estimated as the (DWSEEDS)/(DWDR+DWSEEDS) ratio which is a key indicator for individual plant yield. Then DW and nitrogen concentrations (N%) were combined to determine the nitrogen harvest index (NHI) as (N%SEEDS×DWSEEDS)/(N%DR×DWDR+N%SEEDS×DWSEEDS) which is a key indicator of seed filling with nitrogen. Since plant morphology and harvest index varied depending on accessions, the ratio NHI/HI (named ΔNHI when the ratio is normalized to the mean) was monitored in order to compare nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) performances between accessions. In a similar manner, DW, N%, and 15N enrichments (E%) were combined to determine the partition of 15N in seeds, named here as 15N-Harvest-Index (15NHI), which is the proportion of 15N absorbed at the vegetative stage and remobilized to the seeds at the reproductive stage. 15NHI calculated as E%SEEDS×N%SEEDS×DWSEEDS/(E%DR×N%DR×DWDR+E%SEEDS×N%SEEDS×DWSEEDS) is an indicator for nitrogen remobilization efficiency to the seeds. Again, due to the plant morphology and harvest index genetic variations, the ratio 15NHI/HI (named ΔRem when the ratio is normalized to the mean) was estimated to compare nitrogen remobilization efficiency (NRE) performances between accessions. C/NSEEDS is a key indicator for seed nutritive value. The relative specific abundance (RSA, see the Materials and methods) is an indicator of the 15N enrichment of SEEDS and DR that can be combined to estimate the RSASEEDS/RSA[SEEDS+DR] ratio and nitrogen dilutions.

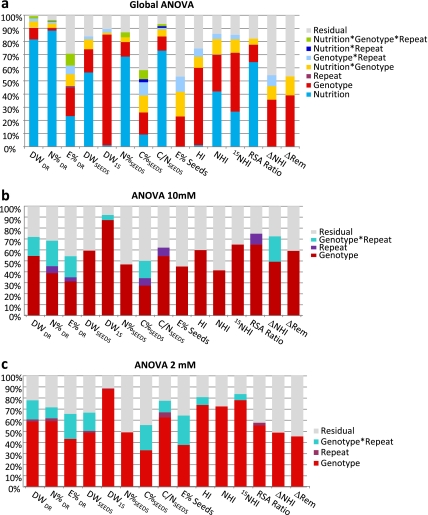

Two independent experiments (biological repeats R1 and R2) were carried out, at two different dates and in identical growth conditions. Each biological repeat contained four plant replicates per genotype. ANOVA was performed on the whole set of data from R1 and R2 at HIGH N and LOW N, in order to determine the effect of nutrition, genotype, and repeat treatments on the variations of traits. For most of the traits, the effect of nutrition on their variations was higher than the effect of genotype, repeat or interactions (Fig. 1a; see Supplementary Table S2 at JXB online). Surprisingly, the variation of DW1S, E%SEEDS and HI were poorly affected by plant nutrition or repeats showing that seed size and sink-to-source ratio are robust traits in Arabidopsis. For all the traits, the effects of genotype and of nutrition×genotype interaction were significant, revealing heritable differences between genotypes whatever the plant nutrition conditions, as well as a differential response to nutrition depending on genotype. It can be noticed that repeat effects were minor for DR traits and not significant for SEEDS traits (Fig. 1a; see Supplementary Table S2 at JXB online), allowing us to use R1 and R2 as biological repeats.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of ANOVA of dry weight (DW, g), N concentration (N%, mg 100 mg−1 DW), C concentration (C%, mg 100 mg−1 DW), C/N ratio, 15N enrichment (E%; 15N/N as %), HI (harvest index), NHI (nitrogen harvest index), 15NHI (partition of 15N in seeds), RSA ratio, and extra remobilization (ΔRem) in the 19 Arabidopsis accessions grown under HIGH N and LOW N nutrition.DR, Dry remains; SEEDS, all seeds; 1S: one seed. Results of ANOVA are fully presented in Supplementary Table S2,S3,S4 at JXB online. (a) Global ANOVA using data obtained at HIGH N and LOW N. (b) ANOVA 10 mM using data obtained at HIGH N. (c) ANOVA 2 mM using data obtained at LOW N. Histograms show the effects due to nutrition, genotype, repeat and interactions as a percentage of the variation explained.

Performed independently on data obtained at LOW N and at HIGH N (Fig. 1b, c; see Supplementary Table S3,S4 at JXB online), ANOVA analyses confirmed that behind nutrition, the main effect on trait variations was due to genotype. One important result of ANOVA on HIGH N and LOW N traits was that genetic effects were still high for the calculated traits, such as HI, NHI, 15NHI, RSA, and ΔRem. The genetic part of trait variation led us to estimate heritabilities (Table 1). Except for C%SEEDS, E%DR at HIGH N, and C%DR at LOW N heritabilities higher than 0.50 were estimated for all the traits.

Table 1.

Heritability of dry weight (DW, g), N concentration (N%, mg 100 mg−1 DW), C concentration in seeds (C%, mg 100 mg−1 DW), C/N ratio in seeds, 15N enrichment (E%; 15N/N as %), HI (harvest index), NHI (nitrogen harvest index), 15NHI (partition of 15N in seeds), RSA ratio, ΔNHI, and ΔRem at HIGH N (10 mM) or at LOW N (2 mM)

| DWDR | N%DR | E%DR | DWSEEDS | DW1S | N%SEEDS | C%SEEDS | C/NSEEDS | E%SEEDS | HI | NHI | 15NHI | RSA ratio | ΔNHI | ΔRem | |

| HIGH N | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.57 | 0.33 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.69 | 0.51 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.68 |

| LOW N | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.92 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.80 | 0.57 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.57 |

Two independent biological repeat containing four individual plants have been done.

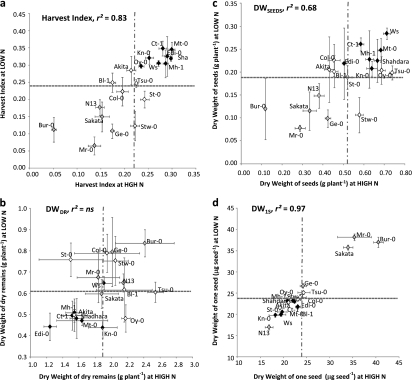

Characterization of plant behaviour with regards to yield

Harvest index [HI=DWSEED/(DWSEEDS+DWDR)] was very variable depending on genotypes, but globally unchanged between HIGH N and LOW N for most of the accessions (Fig. 2a). The comparison of the mean (±SD) of each accession with the mean value of the core collection facilitated the classification of accessions into three groups: (L) low HI (significantly lower than the mean at LOW N and HIGH N), (M) medium HI (not significantly different from the mean at LOW N or HIGH N), and (H) high HI (significantly higher than the mean at LOW N and HIGH N). It is noticeable that the HI of Bur-0 and Mr-0 were the lowest at HIGH N and LOW N, respectively, while HI of Mt-0 was the highest at both HIGH N and LOW N. The accessions belonging to the L group were mostly characterized by a lower DWSEEDS (Fig. 2c) whereas the accessions belonging to the H group were mostly characterized by a lower DWDR (Fig. 2b). At HIGH N or LOW N, HI was indeed correlated with the dry weight of seeds (DWSEEDS) and with the dry weight of dry remains (DWDR) (Table 2). The DWDR and DWSEEDS were increased by approximately 3-fold under ample nitrate supply (HIGH N) compared to nitrate limitation (LOW N), (Fig. 2b, c, respectively). This fold-range was, however, different depending on the accessions, with some like Tsu-0 showing higher increases in DWSEEDS and DWDR at HIGH N compared with LOW N, contrasting with some like Bur-0 with lower DWSEEDS at HIGH N compared with LOW N, for example (Fig. 2b, c).

Fig. 2.

Natural variation in harvest index (HI, a), dry weight of dry remains (DWDR, g plant−1, b), dry weight of seeds (DWSEEDS, g plant−1, c), and dry weight of one seed (DW1S, mg seed−1, d) at high (HIGH N) and low (LOW N) nitrate supplies. Values are adjusted means from two biological repeats with four individual plants each, ±SD. Accessions belonging to HI clusters L (Low HI), M (Medium HI), and H (High HI) are represented by diamonds with light grey, white, and black colours, respectively. The horizontal hashed grey line represents the mean of the core collection at HIGH N and the vertical hashed grey line represents the mean at LOW N. Correlations between trait at LOW N and HIGH N are presented in the upper left square. r2, Determination coefficient; ns, not significant.

Table 2.

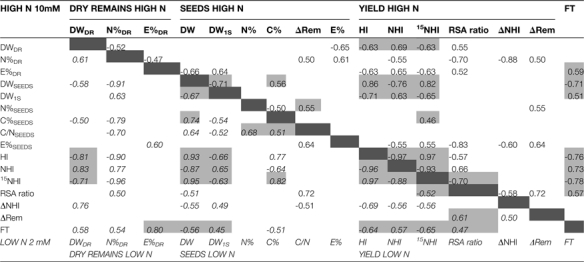

Correlations between measured and calculated traits at HIGH N (upper right, normal) or at LOW N (lower left, italic) in the 19 different Arabidopsis accessions

Correlations were computed using all the means calculated for each accession. Only significat correlations (P < 0.05) are presented. Light grey boxes underpin similarities in correlations found at HIGH N and at LOW N. (FT: flowering time). Dark grey boxes separate values of correlations at HIGH N from correlations at LOW N.

|

Yield, as DWSEEDS or HI, might depend on the number of seeds produced by each plant as well as on the dry weight of each seed (DW1S). Most of the accessions presented a DW1S close to 23 μg (Fig. 2d) and the range of variation for DW1S was too narrow to explain the range of HI and DWSEEDS variations, showing that the main source of variation for yield was the number of seeds. However, a few heavy-seed accessions (Bur-0, Mr-0, and Sakata) and light-seed accessions (N13 and Kn-0) (Fig. 2d) were noted. Despite the weak genotype variation for DW1S, the negative correlation observed between DWSEEDS and DW1S at HIGH N and LOW N might reveal that plants producing heavier seeds also produced fewer seeds (Table 2). HI, DWDR, DWSEEDS, and DW1S were correlated to flowering time (Table 2; see Supplementary Fig. S2 at JXB online) showing that plants flowering late had a lower yield and a higher vegetative biomass compared with early flowering accessions.

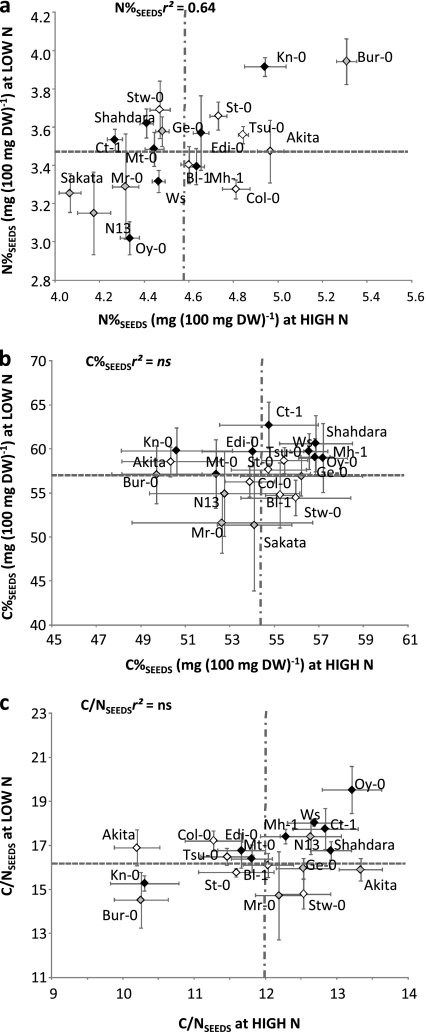

N and C concentrations in seeds are differentially sensitive to nutrition depending on accessions

Seed quality in crops depends on lipid or protein contents as for rapeseed or wheat, for example. The nitrogen concentration in seeds (N%SEEDS) was significantly higher at HIGH N than at LOW N (Fig. 3a). At HIGH N, N%SEEDS ranged between 4% and 5.5% while at LOW N, N%SEEDS ranged between 3% and 4%. Globally, N% in seeds at HIGH N was 1.3-fold that measured at LOW N. N%SEEDS at HIGH N and LOW N were significantly correlated (r2=0.64, P <0.05) showing that plants with high (Bur-0 and Kn-0) or with low (N13, Oy-0, and Sakata) nitrogen concentrations in seeds were the same at HIGH N and LOW N. Some accessions were better for N%SEEDS at HIGH N than at LOW N, like Col-0, others were relatively better at LOW N, like Shahdara and Stw-0.

Fig. 3.

Natural variation in nitrogen concentration in seeds (N%SEEDS, mg 100 mg−1 DW, a), carbon concentration in seeds (C%SEEDS, mg 100 mg−1 DW, b), and carbon to nitrogen ratio in seeds (C/NSEEDS, c) at high (HIGH N) and low (LOW N) nitrate supplies. Values are adjusted means from two biological repeats with four individual plants each, ±SD. Accessions belonging to HI clusters L (Low HI), M (Medium HI), and H (High HI) are represented by diamonds with light grey, white, and black colours respectively. The horizontal hashed grey line represents the mean of the core collection at HIGH N and the vertical hashed grey line represents the mean at LOW N. Correlations between trait at LOW N and HIGH N are presented in the upper left square. r2, Determination coefficient; ns, not significant.

As another component of seed quality, C% is a potential indicator of oil or starch amount in seeds. At the opposite of N%SEEDS, C%SEEDS was globally higher at LOW N than at HIGH N (Fig. 3b) and there was also a large variation depending on genotype. It is noticeable that the C%SEEDS was highly affected by HIGH N environment in Bur-0, Kn-0, and Akita. Independently of some individual behaviour, there was globally a positive correlation between C%SEEDS and DWSEEDS (Table 2) at LOW N and HIGH N showing that, in Arabidopsis, as in many plants, yield is correlated with carbon filling in seeds. C%SEEDS was correlated with N%SEEDS only at HIGH N, suggesting that nitrogen in seeds was diluted by carbon when plants were growing under ample nitrogen nutrition.

The C/NSEEDS ratio of seeds can be used as a global indicator of lipid/starch to protein relative contents. C/NSEEDS was correlated with CSEEDS and NSEEDS at HIGH N and LOW N, and with HI and 15NHI at LOW N, showing the effect of nitrogen remobilization on C and N relative contents in seeds (Table 2). C/NSEEDS was the highest in Oy-0 at HIGH N and LOW N and the lowest in Bur-0 at HIGH N and LOW N and in Akita and Kn-0 at HIGH N (Fig. 3c).

Variation of the residual nitrogen in the dry remains is much larger than variation of nitrogen contents in seeds

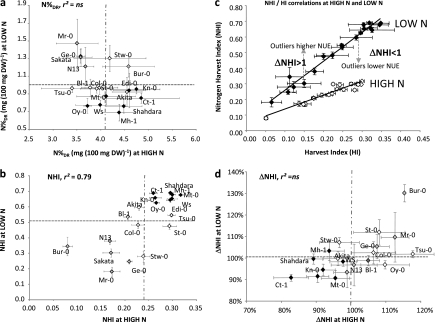

In agriculture, an essential component of nitrogen use efficiency is the residual nitrogen remaining in the dry parts of the plant that is left in the field after harvest. Indeed it can be considered that the nitrogen of the dry remains was not utilized for plant production. Therefore, two indicators were examined: the nitrogen concentration in the dry remains (N%DR) and the nitrogen harvest index (NHI) that is the proportion of nitrogen contained in the seeds compared with the whole plant nitrogen content (mg N in seeds/mg N in whole plant).

The large increase of N%DR at HIGH N compared to LOW N showed that the amount of nitrogen in dry remains after harvest increased when plants were not nitrate limited while the nitrogen concentration in their seeds was poorly modified (Fig. 4a). N%DR was also variable depending on the accessions. The careless accessions, with high N%DR, and the careful accessions, with low N%DR, were not the same at HIGH N and LOW N (Fig. 4a), showing that genotype performances were dependent on environmental conditions. Negative and positive correlations between N%DR and DWDR were found at HIGH N and LOW N, respectively (Table 2). At HIGH N, negative correlation again reveals the dilution effects of nitrogen due to plant growth and biomass increase. At LOW N, it shows the limiting effect of nitrogen availability on biomass production.

Fig. 4.

Natural variation in nitrogen concentration in dry remains (N%DR, mg 100 mg−1 DW, a) and total nitrogen index harvest (NHI, b) and ΔNHI (d) at high (HIGH N) and low (LOW N) nitrate supplies. Values are adjusted means from two biological repeats with four individual plants each, ±SD. Accessions belonging to HI clusters L (Low HI), M (Medium HI), and H (High HI) are represented by diamonds with light grey, white, and black colours, respectively. The horizontal hashed grey line represents the mean of the core collection at HIGH N and the vertical hashed grey line represents the mean at LOW N. Correlations between traits at LOW N and HIGH N are presented in (c). Correlations between HI and NHI are presented at HIGH N (white) and LOW N (black) and outliers with higher NUE (ΔNHI >1) or lower NUE (ΔNHI <1) are shown. r2, Determination coefficient; ns, not significant.

NHI of accessions growing at LOW N and at HIGH N are presented in Fig. 4b. Due to the low genetic variation of N%SEEDS and N%DR at both HIGH N and at LOW N, NHI was highly correlated to HI (Table 2). Therefore, HI seems to be a good estimate of NHI in Arabidopsis. However, in contrast to HI, the NHI values were significantly higher at LOW N than at HIGH N (Fig. 4b). This is mainly the result of the significantly higher values of N%DR at HIGH N compared with LOW N (4-fold; Fig. 4a). The higher NHI values found at LOW N compared with HIGH N show that nitrogen use efficiency was better under nitrate-limiting conditions than under plentiful conditions.

Nitrogen use efficiency is higher at LOW N than at HIGH N and presents genetic variation

The accessions clustered in the H, M, and L groups on the basis of their HI values (Fig. 2a) were grouped in a similar way for NHI (Fig. 4b) thus revealing strong correlations between HI and NHI at both LOW N and HIGH N (Fig. 4c; Table 2). While NHI was mainly dependent on HI and on the sink-to-source ratio, outliers from the regression line were also identified (Fig. 4c). To characterize them, for each individual plant (p) the ΔNHI indicator was computed as: ΔNHI=(NHIp/HIp)/(NHI/HI mean). ΔNHI was representative of the relative nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) performance of each accession and was independent of HI. Accessions with ΔNHI >100% were high-performing whereas accessions with ΔNHI <100% were low-performing, compared with the middle range of the core collection. It can be noted that, at both LOW N and HIGH N, Bur-0 had the highest ΔNHI while Shahdara and Ct-1 had the lowest (Fig. 4d). Few accessions, like Oy-0, were more efficient at HIGH N than at LOW N and, by contrast, opposite accessions like Stw-0 or Mh-1 were more efficient at LOW N than at HIGH N.

Nitrogen remobilization to the seeds is higher at LOW N compared to HIGH N and more variable at HIGH N than at LOW N

Nitrogen remobilization was investigated using 15N tracing experiments as done on crops in fields (Coque and Gallais, 2007; Coque et al., 2008). Labelled 15NO3 was provided twice at the vegetative stage, a long time before flowering (15–45 d depending on accessions; see Supplementary Table S2 at JXB online), when rosette growth rate and leaf emergence were optimum. This allowed it to be assumed that the entire 15N nitrate absorbed was used for assimilation and protein synthesis and not for storage into the vacuole. After labelling, sand on which the plants were grown was carefully rinsed, thus avoiding further 15N isotope residual uptake. As a prerequisite of data meaning, the total 15N contained in the whole plant [DR+SEEDS] at harvest was considered to be equal to the total quantity of 15N absorbed by the plant at labelling time. Therefore the partition of 15N in the seeds, computed as the ratio [mg 15N in the SEEDS/mg 15N in the (DR+SEEDS)], and named 15NHI by reference to the HI and NHI abbreviations used below, is assumed to be representative of the efficiency of 15N remobilization to the seeds.

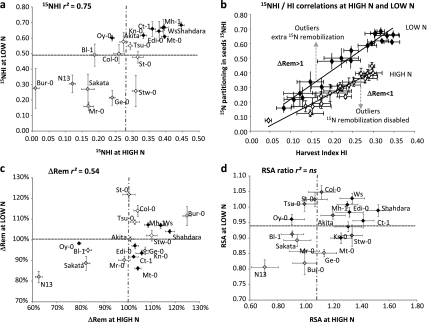

Globally, the 15NHI values at LOW N were significantly higher than at HIGH N (Fig. 5a). This trend was similar to that found for NHI and showed that N remobilization to the seeds was 2-fold higher at LOW N compared with HIGH N. As observed for NHI, the relative 15NHI variations between accessions were similar to those observed for HI, and the accessions from the clusters H, M, and L previously defined (Fig. 2a) were grouped in a similar way. Therefore, at HIGH N and LOW N, HI and 15NHI values were significantly and strongly correlated to each other (Table 2) indicating that N remobilization to the seeds was significantly linked to yield and sink-to-source ratio. When the regression lines of the HI to 15NHI correlations were observed, although most of the accession means were plotted on the regression line (Fig. 5b), outliers were significantly identified. Accessions significantly above the regression line were more efficient at 15N remobilization. Those significantly located below the line were less efficient (Fig. 5c). To facilitate the identification of outliers, for each individual plant (p) the distance from their point to the regression line was computed, calculating the relative slope ΔRem as: ΔRem=(15NHIp/HIp)/(mean of 15NHI/HI). ΔRem was then expressed as a % of the mean value of the whole population and was representative of the relative nitrogen remobilization efficiency (NRE). Then, a 100% ΔRem value represents points located on the regression line (Fig. 5b) and ΔRem can be understood as an ‘extra-remobilization’ indicator when higher than 100% and as a ‘N remobilization disabled’ indicator when lower than 100%. ΔRem showed that N13, Sakata, Bl-1, and Oy-0 were significantly less efficient at 15N extra-remobilization, whereas Bur-0, Col-0, WS, Mh-1, and Shahdara were performing significant extra-remobilization (Fig. 5c). It can be noted that, for most of the lines, their extra or disabled remobilization tendencies were independent of nutrition (Fig. 1). A few accessions, such as Mt-0, Ge-0, and Stw-0, presented extra-remobilizing performances at HIGH N but were remobilization disabled at LOW N. There was no accession with extra-remobilization potential at LOW N but remobilization deficiency at HIGH N. A striking result was that accessions with higher or lower ΔRem were not always the same as those with higher or lower ΔNHI. For example, ΔNHI value of Shahdara and Ct-1 ranked among the lowest at HIGH N while their ΔRem values were the best at HIGH N. This indicated that better nitrogen filling into the seeds was not obligatory due to higher nitrogen remobilization performance. Nitrogen uptake after labelling and during seed filling might also be an important process for NHI.

Fig. 5.

Natural variation in 15N partitioning in seeds (15NHI, a), extra remobilization (ΔRem, c), and relative specific abundance ratio (RSA ration, d) at high (HIGH N) and low (LOW N) nitrate supplies. Values are adjusted means from two biological repeats with four individual plants each, ±SD. Accessions belonging to HI clusters L (Low HI), M (Medium HI), and H (High HI) are represented by diamonds with light grey, white, and black colours, respectively. The horizontal hashed grey line represents the mean of the core collection at HIGH N and the vertical hashed grey line represents the mean at LOW N. Correlations between traits at LOW N and HIGH N are presented in (b). Correlations between HI and 15NHI are presented at HIGH N (white) and LOW N (black) and outliers with extra remobilization (ΔRem >1) or remobilization disabled performances (ΔRem <1) are shown. r2, Determination coefficient; ns, not significant.

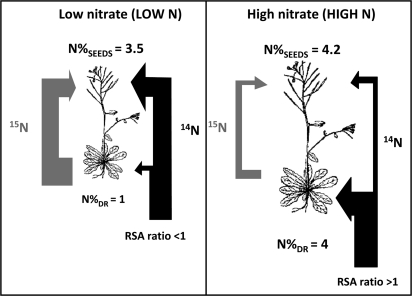

Relative specific abundance (RSA) ratio as indicator of the allocation of the nitrogen absorbed during seed filling

RSA is related to 15N enrichment and is an indicator of 15N dilution by the natural 14N absorbed by roots after labelling and until harvest. RSASEEDS/RSA[DR+SEEDS] ratio, previously used by Gallais et al. (2006) in maize, can be (i) equal to 1 when 15N dilution is similar in SEEDS and in DR, (ii) lower than 1 when the 14N absorbed after labelling is routed to the seeds, while 15N is retained in DR, and (iii) higher than 1 when seeds are preferentially loaded with 15N remobilized while the 14N absorbed post-labelling is allocated to the vegetative parts of the plant. It was found that, except in a few accessions, the RSASEEDS/RSA[DR+SEEDS] ratio was higher than 1 at HIGH N and lower than 1 at LOW N (Fig. 5d).

At LOW N, most of the nitrogen assimilated before and post-flowering was then allocated to the seeds, thus increasing the nitrogen use efficiency for seed filling and decreasing the amount of nitrogen lost in the dry remains (Fig. 6). By contrast, at HIGH N, most of the accessions were routing the nitrogen taken up from the substrate ‘post-labelling’ to their rosettes where it was stored and subsequently lost in the dry remains (Fig. 6). Some exceptions to this HIGH N feature were, however, detected in N13, Sakata, Bl-1, and Oy-0 (Fig. 5c). These four accessions used their post-flowering nitrogen absorption to the benefit of seed filling. This was consistent with the fact that they exhibited a lower N%DR than other lines and also a ΔRem below 100% confirming that their strategy was not N remobilization but post-flowering N uptake to ensure seed filling. 15N labelling was performed at 40 DAS and 42 DAS for all the accessions; it was then possible that flowering time and plant lifespan have differentially modified the 15N dilution with the 14N absorbed afterwards. The RSASEEDS/RSA[DR+SEEDS] ratio was indeed positively correlated with flowering time (Table 2).

Fig. 6.

Schematic interpretation of results of N remobilization (15NHI), RSA ratio, N% of dry remains (N%DR, mg 100 mg−1 DW) and of seeds (N%SEEDS, mg 100 mg−1 DW) in plants grown at low (LOW N) and high (HIGH N) nitrate supplies. The allocation of unlabelled 14N absorbed at reproductive stage is indicated by dark grey arrows. The RSA ratio <1 observed at LOW N indicates that plants have preferentially allocated unlabelled 14N absorbed at the reproductive stage to the seeds. The RSA ratio >1 observed at HIGH N indicates that plants have preferentially allocated unlabelled 14N absorbed at the reproductive stage to the vegetative tissues (rosette or stems). The remobilization of 15N from rosette to seeds represented by a light grey arrow is higher at LOW N than at HIGH N. The high 15N remobilization and the low 14N post-labelling uptake in rosettes of plants grown at LOW N compared to plants at HIGH N explain the low N%DR at LOW N compared to HIGH N. The high 15N remobilization and the high post-labelling translocation of 14N into seeds of plants grown at LOW N explain that the difference of N%SEEDS at HIGH N and LOW N is lower than the difference found between N%DR at HIGH N and LOW N.

Conclusion

Nitrogen is one among a long list of environmental factors affecting plant development. Adaptation to variable nitrogen availability differs between Arabidopsis accessions and several previous studies have demonstrated that there are significant effects of the genotype×nitrogen environment interaction for biomass, nitrogen contents, and nitrogen uptake in Arabidopsis (Rauh et al., 2002; Loudet et al., 2003; Chardon et al., 2010).

In the present study, it is shown that the dry weight of one seed (DW1S), the proportion of the seeds biomass compared with whole plant biomass (HI), and the proportion of nitrogen remobilized to the seeds (15NHI) are robust traits, highly heritable, while other traits are more influenced by environment. This suggests that the different accessions are able to make use of the extra N supplied at HIGH N to increase biomass and/or N storage, but that subsequently they allocated a relatively defined proportion of their nitrogen to the seeds. Consistent with this, it was observed that nitrate availability governs nitrogen concentration in dry remains but not in seeds, and influences vegetative biomass and yield but poorly modifies HI or DW1S. Because most of the accessions have the same DW1S at LOW N and HIGH N, nitrate availability mainly results in modifying seed number. The increase at LOW N of both nitrogen remobilization (15NHI) and post-labelling nitrogen allocation (RSASEEDS/RSA[DR+SEEDS] <1) to the seeds has resulted in a lower range of variation in seed nitrogen concentrations (N%SEEDS) compared with nitrogen concentration in the dry remains (N%SEEDS). The higher C/NSEEDS at LOW N compared to HIGH N was then mainly due to the higher C%SEEDS recorded at LOW N.

The most striking results are provided by the 15N tracing experiments and by the measurement of nitrogen content in seeds and dry remains. Data show that nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) and nitrogen remobilization efficiency (NRE) are higher at LOW N than at HIGH N. Both are highly correlated to harvest index, suggesting a strong link between nitrogen allocation and yield. However, the computing of ΔNHI and ΔRem allow the detection of genetic variations of NUE and NRE independently of HI variations, and to identify accessions with a relatively higher or lower score for NUE or NRE.

By contrast with Gallais et al. (2006) on maize, a large variation of the RSASEEDS/RSA[DR+SEEDS] ratio was found that was highly informative concerning the sink–source nitrogen management in Arabidopsis. This ratio shows that LOW N condition increases both nitrogen remobilization and translocation of the nitrogen absorbed post-flowering to the seeds, whereas under ample nitrate supply, the RSA ratio shows that the nitrogen absorbed post-flowering is mainly driven to the vegetative tissues (Fig. 6). Despite this feature, the significant negative correlation at HIGH N between RSA ratio and ΔNHI suggests that post-labelling nitrogen uptake was a limiting factor for seed filling at HIGH N also.

The new insights provided here into the links between nitrogen management at the whole plant level and the control of biomass and yield by nitrate availability, are facilitating the comprehension of the various components of nitrogen use efficiency in Arabidopsis. The NUE and NRE indicators proposed in this study will be helpful for comparison with other plant species and also as a basis for further analysis in Arabidopsis using mutants or mapping populations.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Supplementary Fig. S1. Design of the 15N labelling procedure for pulse/chase assays.

Supplementary Fig. S2. Correlations between harvest index and flowering time at HIGH N (a) and at LOW N (b) show continuous natural variation between accessions.

Supplementary Table S0. Whole data set provided as an Excel file.

Supplementary Table S1. Arabidopsis thaliana accession provided by the Versailles Genetics and Plant Breeding Laboratory Arabidopsis thaliana Resource Centre (INRA Versailles France, http://dbsgap.versailles.inra.fr/vnat/).

Supplementary Table S2. Global ANOVA for all traits at LOW N and HIGH N.

Supplementary Table S3. ANOVA for all traits at HIGH N.

Supplementary Table S4. ANOVA for all traits at LOW N.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Julien Barthélémy for technical assistance (CDD Technician ANR-05-GPLA-032-05), Pascal Tillard (INRA, Montpellier, France) for 15N determination and Dr Astrid Wingler (University College of London), Dr Patrick Armengaud (INRA, Versailles), and Dr Eugene Diatloff (INRA, Versailles) for discussion and proofreading. The authors thank the Versailles Resource Center (http://dbsgap.versailles.inra.fr/vnat/) for providing seeds of the accessions.

The Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (ANR) Génoplante ARCOLE programme (ANR-05-GPLA-032-05) provided financial support for the experiments and a technician's salary.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- LOW N

low nitrogen

- HIGH N

high nitrogen

- DR

dry remains after seed harvest

- SEEDS

total seeds of one plant

- DW

dry weight

- DWDR

dry weight of dry remains

- DWSEEDS

dry weight of total seeds

- DW1S

dry weight of one seed

- E%

15N enrichment

- N%

nitrogen concentration as g.(100g DW)-1

- C%

carbon concentration as g 100 g-1 DW

- DAS

days after sowing

- HI

harvest index

- NHI

nitrogen harvest index

- 15NHI

15N partitioning in seeds

- RSA

relative specific abundance

- ΔRem

indicator for extra nitrogen remobilization

- NUE

nitrogen use efficiency

- NRE

nitrogen remobilization efficiency

References

- Bänziger M, Betran FJ, Lafitte HR. Efficiency of high nitrogen environment for improving maize for low nitrogen environment. Crop Science. 1997;37:1103–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Beninati NF, Busch RH. Grain protein inheritance and nitrogen uptake and redistribution in a spring wheat cross. Crop Science. 1992;32:1471–1475. [Google Scholar]

- Borrel A, Hammer G, Van Oosterom E. Stay-green: a consequence of the balance between supply and demand for nitrogen during grain filling. Annals of Applied Biology. 2001;138:91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Chardon F, Barthélémy J, Daniel-Vedele F, Masclaux-Daubresse C. Natural variation of nitrate uptake and nitrogen use efficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana cultivated with limiting and ample nitrogen supply. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2010;61:2293–2302. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen LE, Below FE, Hageman RH. The effect of ear removal on senescence and metabolism of maize. Plant Physiology. 1981;68:1180–1185. doi: 10.1104/pp.68.5.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliquet J-B, Deléens E, Mariotti A. C and N mobilization from stalk to leaves during kernel filling by 13C and 15N tracing in Zea mays L. Plant Physiology. 1990;94:1547–1553. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.4.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coque M, Gallais A. Genetic variation for nitrogen remobilization and postsilking nitrogen uptake in maize recombinant inbred lines: heritabilities and correlations among traits. Crop Science. 2007;47:1787–1796. [Google Scholar]

- Coque M, Martin A, Veyrierias JB, Hirel B, Gallais A. Genetic variation of N-remobilization and postsilking N-uptake in a set of maize recombinant inbred lines. IIi. QTL detection and coincidences. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2008;117:729–747. doi: 10.1007/s00122-008-0815-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz C, Lemaître T, Christ C, Azzopardi M, Kato Y, Sato F, Morot-Gaudry J, Le Dily F, Masclaux-Daubresse C. Nitrogen recycling and remobilization are differentially controlled by leaf senescence and development stage in Arabidopsis under low nitrogen nutrition. Plant Physiology. 2008;147:1437–1449. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.119040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvick DN. Genetic contributions to advances in yield of U.S. maize. Maydica. 1992;37:69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Gallais A, Coque M, Quillere I, Prioul JL, Hirel B. Modelling postsilking nitrogen fluxes in maize (Zea mays) using 15N labelling field experiments. New Phytologist. 2006;172:696–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good AG, Shrawat AK, Muench DG. Can less yield more? Is reducing nutrient imput into the environment compatible with maintaining crop production? Trends in Plant Science. 2004;9:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen PL, Holm P, Krupinska K. Leaf senescence and nutrient remobilisation in barley and wheat. Plant Biology. 2008;10(Supplement 1):37–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joppa LR, Du C, Hart GE, Hareland GA. Mapping gene(s) for grain protein in tetraploid wheat (Triticum turgidum L.) using a population of recombinant inbred chromosome lines. Crop Science. 1997;37:1586–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaître T, Gaufichon L, Boutet-Mercey S, Christ A, Masclaux-Daubresse C. Enzymatic and metabolic diagnostic of nitrogen deficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana Wassileskija accession. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2008;49:1056–1065. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loudet O, Chaillou S, Merigout P, Talbotec J, Daniel-Vedele F. Quantitative trait loci analysis of nitrogen use efficiency in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2003;131:345–358. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.010785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masclaux-Daubresse C, Daniel-Vedele F, Dechorgnat J, Chardon F, Gaufichon L, Suzuki A. Nitrogen uptake, assimilation and remobilisation in plants: challenges for sustainable and productive agriculture. Annals of Botany. 2010;105:1141–1157. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcq028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masclaux-Daubresse C, Reisdorf-Cren M, Orsel M. Leaf nitrogen remobilisation for plant development and grain filling. Plant Biology. 2008;10(Supplement 1):23–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann H, Camilleri C, Bérard A, Bataillon T, David J, Reboud X, Le Corre V, Caloustian C, Gut I, Brunel D. Nested core collections maximizing genetic diversity in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal. 2004;38:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson S, See D, Meyer FD, Garner JP, Foster CR, Blake TK, Fischer AM. Mapping of QTL associated with nitrogen storage and remobilization in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) leaves. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2003;54:801–812. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick JW, Offler CE. Compartmentation of transport and transfer events in developping seeds. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2001;52:551–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presterl T, Seitz G, Landbeck M, Thiemt W, Schmidt W, Geiger HH. Improving nitrogen use efficiency in European maize: estimation of quantitative parameters. Crop Science. 2003;43:1259–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Rajcan I, Tollenaar M. Source:sink ratio and leaf senescence in maize. II. Nitrogen metabolism during grain filling. Field Crop Research. 1999;60:255–265. [Google Scholar]

- Rauh B, Basten C, Buckler E. Quantitative trait loci analysis of growth response to varying nitrogen sources in Arabidopsis thaliana. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2002;104:743–750. doi: 10.1007/s00122-001-0815-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossato L, MacDuff JH, Laine P, Le Deunff E, Ourry A. Nitrogen storage and remobilization in Brassica napus L. during the growth cycle: effects of methyl jasmonate on nitrate uptake, senescence, growth, and VSP accumulation. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2002;53:1131–1141. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.371.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salon C, Munier-Jolain N, Duc G, Voisin A-S, Grandgirard D, Larmure A, Emery RJN, Ney B. Grain legume seed filling in relation to nitrogen acquisition: a review and prospects with particular reference to pea. Agronomie. 2001;21:539–552. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W-H, Zhou Y, Dibley KE, Tyerman SD, Furbank RT, Patrick JW. Nutrient loading of developing seeds. Functional Plant Biology. 2007;34:314–331. doi: 10.1071/FP06271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.